User login

Asymptomatic maternal Zika infection doesn’t dampen birth defect risk

DENVER – One of many daunting challenges posed by the ongoing global Zika virus epidemic stems from the recent realization that the presence or absence of symptoms in women infected in pregnancy has no bearing on whether their babies will have Zika-associated birth defects, Margaret Honein, PhD, observed at the annual meeting of the Teratology Society.

This has profound clinical consequences because roughly 80% of all maternal Zika infections are asymptomatic or feature such mild symptoms that women don’t report them.

“There was, I think, some hope early on that symptoms in the mother would correlate with outcomes, but that has not been the case at all. In the U.S. population, we’ve seen about a 6% Zika-associated birth defects rate in both symptomatic and asymptomatic mothers,” said Dr. Honein, chief of the birth defects branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “We have a huge challenge in identifying the women who have asymptomatic infections, yet they’re at the same risk of having an adverse outcome in their baby.”[[{"fid":"199780","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","fields":

She provided conference attendees with the latest information on Zika, including preliminary results from ongoing CDC investigations. Along the way, she tackled many of the questions Zika experts hear most often from clinicians, while emphasizing that much about congenital Zika syndrome remains unknown.

Just how serious is the global threat of Zika virus infection?

On Feb. 8, 2016, the CDC activated a Level 1 emergency response to Zika. To put that into perspective, this is only the fourth time in history the agency has gone to Level 1. The other occasions were for Hurricane Katrina, the H1N1 pandemic flu, and Ebola.

“This is worse than thalidomide,” said Jan M. Friedman, MD, after listening to Dr. Honein and other speakers at the Zika update held during the conference. Dr. Friedman, a medical geneticist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, delivered the Robert L. Brent Lecture.

What is the level of risk for fetal/infant birth defects associated with maternal Zika virus infection?

The birth defect risk is somewhere between 5% and 10%, with the true figure probably being on the high end. Reports quoting risks on the lower end are based upon laboratory testing for maternal IgM antibodies, which couldn’t rule out cross reaction with other flaviviruses, including dengue virus, which is common in most of the same locales as Zika. Women who have been infected with dengue but not Zika are not at increased risk for birth defects. Zika is the first mosquito-borne virus to be recognized as teratogenic in humans.

The birth defects seen in conjunction with Zika infection are not unique. They can have many different causes. CDC investigators examined birth defects data from three states during the year before the Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere and determined that the background rate of microcephaly, neural tube defects, eye abnormalities, hearing loss, and other Zika-like birth defects was 3 per 1,000 live births. Among women with Zika virus infection in pregnancy, however, the rate is more than 20-fold higher at 50-100 per 1,000, according to Dr. Honein.

When during pregnancy does maternal Zika infection pose the highest risk to the fetus?

Studies published from Colombia and Brazil show the peak risk is when infection occurs during the first trimester or early in the second trimester. That’s consistent with the U.S. registry experience as well. Of note, the median time between development of maternal symptoms and the first notation of fetal microcephaly on ultrasound has been 18 weeks.

“This has important implications for women who’ve been infected. Just because they may have had two consecutive apparently normal monthly fetal ultrasounds doesn’t rule out by any means congenital Zika syndrome because there does appear to be a relatively long time period before these findings appear,” Dr. Honein noted.

What is the full range of potential health problems Zika infection can cause?

“What we’ve seen so far is definitely just the tip of the iceberg,” Dr. Honein cautioned. “It’s very severe, but I think we don’t yet know the full range of disabilities. There’s much more to come here.”

Most of the infants in the U.S. registry are just now reaching 1 year of age. Greater understanding of their neurodevelopment will require follow-up to age 2 or beyond.

Also, the information available to date on Zika-associated birth defects is based largely on scrutiny of infants with microcephaly along with any additional findings, such as chorioretinal scarring.

“We know relatively little about infants with only the other conditions – only hearing loss, for example, or only eye abnormalities,” Dr. Honein said. “While we know there are children who have microcephaly and they have needs, there may be a much larger number of children with lesser impairment, but who still have disabilities that are going to necessitate provision of services. Being prepared for that is very important.”

Reports from multiple countries make it clear that babies exposed to Zika in utero can have a normal-appearing head at birth but then become microcephalic later in their first year. The incidence of this phenomenon hasn’t yet been pinned down.

“We’ve learned in the last year and a-half that microcephaly is a key marker of some of the relevant underlying brain abnormalities, but microcephaly is not where our focus should be,” she said.

How long does Zika virus persist in the body?

The viremia typically lasts for anywhere from a few days up to 2 weeks. However, viral persistence for as long as 107 days has been documented in some pregnant women.

“I hesitate to put a number on it because every new publication has a longer figure,” Dr. Honein said.

It’s not yet known whether viral persistence in a woman infected prior to her pregnancy is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. The central nervous system is clearly a reservoir for persistent virus. Whole blood is now under study as possibly another. Semen poses a major challenge.

“There are case reports of Zika virus RNA being detected in semen for more than 6 months after the timing of infection, but we don’t yet know for how long it can be sexually transmitted. Is there really infectious virus present or just particles of RNA?” she said.

Resources

In partnership with the March of Dimes, the CDC has launched Zika Care Connect, a referral network of roughly 600 specialists in six high-risk states. Their ranks include specialists in maternal-fetal medicine, audiology, radiology, mental health, pediatric neurology, infectious diseases, developmental pediatrics, endocrinology, and pediatric ophthalmology. Another 10 states and at least 600 additional providers will soon be added to the referral network (www.zikacareconnect.org; 1-844-677-0447 toll-free).

Comprehensive, up-to-date Zika information is available to health care providers and the public through the CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/zika, at the Zika Pregnancy Hotline (770-488-7100), and by email at ZikaMCH@cdc.gov.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @ObGynNews

DENVER – One of many daunting challenges posed by the ongoing global Zika virus epidemic stems from the recent realization that the presence or absence of symptoms in women infected in pregnancy has no bearing on whether their babies will have Zika-associated birth defects, Margaret Honein, PhD, observed at the annual meeting of the Teratology Society.

This has profound clinical consequences because roughly 80% of all maternal Zika infections are asymptomatic or feature such mild symptoms that women don’t report them.

“There was, I think, some hope early on that symptoms in the mother would correlate with outcomes, but that has not been the case at all. In the U.S. population, we’ve seen about a 6% Zika-associated birth defects rate in both symptomatic and asymptomatic mothers,” said Dr. Honein, chief of the birth defects branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “We have a huge challenge in identifying the women who have asymptomatic infections, yet they’re at the same risk of having an adverse outcome in their baby.”[[{"fid":"199780","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","fields":

She provided conference attendees with the latest information on Zika, including preliminary results from ongoing CDC investigations. Along the way, she tackled many of the questions Zika experts hear most often from clinicians, while emphasizing that much about congenital Zika syndrome remains unknown.

Just how serious is the global threat of Zika virus infection?

On Feb. 8, 2016, the CDC activated a Level 1 emergency response to Zika. To put that into perspective, this is only the fourth time in history the agency has gone to Level 1. The other occasions were for Hurricane Katrina, the H1N1 pandemic flu, and Ebola.

“This is worse than thalidomide,” said Jan M. Friedman, MD, after listening to Dr. Honein and other speakers at the Zika update held during the conference. Dr. Friedman, a medical geneticist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, delivered the Robert L. Brent Lecture.

What is the level of risk for fetal/infant birth defects associated with maternal Zika virus infection?

The birth defect risk is somewhere between 5% and 10%, with the true figure probably being on the high end. Reports quoting risks on the lower end are based upon laboratory testing for maternal IgM antibodies, which couldn’t rule out cross reaction with other flaviviruses, including dengue virus, which is common in most of the same locales as Zika. Women who have been infected with dengue but not Zika are not at increased risk for birth defects. Zika is the first mosquito-borne virus to be recognized as teratogenic in humans.

The birth defects seen in conjunction with Zika infection are not unique. They can have many different causes. CDC investigators examined birth defects data from three states during the year before the Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere and determined that the background rate of microcephaly, neural tube defects, eye abnormalities, hearing loss, and other Zika-like birth defects was 3 per 1,000 live births. Among women with Zika virus infection in pregnancy, however, the rate is more than 20-fold higher at 50-100 per 1,000, according to Dr. Honein.

When during pregnancy does maternal Zika infection pose the highest risk to the fetus?

Studies published from Colombia and Brazil show the peak risk is when infection occurs during the first trimester or early in the second trimester. That’s consistent with the U.S. registry experience as well. Of note, the median time between development of maternal symptoms and the first notation of fetal microcephaly on ultrasound has been 18 weeks.

“This has important implications for women who’ve been infected. Just because they may have had two consecutive apparently normal monthly fetal ultrasounds doesn’t rule out by any means congenital Zika syndrome because there does appear to be a relatively long time period before these findings appear,” Dr. Honein noted.

What is the full range of potential health problems Zika infection can cause?

“What we’ve seen so far is definitely just the tip of the iceberg,” Dr. Honein cautioned. “It’s very severe, but I think we don’t yet know the full range of disabilities. There’s much more to come here.”

Most of the infants in the U.S. registry are just now reaching 1 year of age. Greater understanding of their neurodevelopment will require follow-up to age 2 or beyond.

Also, the information available to date on Zika-associated birth defects is based largely on scrutiny of infants with microcephaly along with any additional findings, such as chorioretinal scarring.

“We know relatively little about infants with only the other conditions – only hearing loss, for example, or only eye abnormalities,” Dr. Honein said. “While we know there are children who have microcephaly and they have needs, there may be a much larger number of children with lesser impairment, but who still have disabilities that are going to necessitate provision of services. Being prepared for that is very important.”

Reports from multiple countries make it clear that babies exposed to Zika in utero can have a normal-appearing head at birth but then become microcephalic later in their first year. The incidence of this phenomenon hasn’t yet been pinned down.

“We’ve learned in the last year and a-half that microcephaly is a key marker of some of the relevant underlying brain abnormalities, but microcephaly is not where our focus should be,” she said.

How long does Zika virus persist in the body?

The viremia typically lasts for anywhere from a few days up to 2 weeks. However, viral persistence for as long as 107 days has been documented in some pregnant women.

“I hesitate to put a number on it because every new publication has a longer figure,” Dr. Honein said.

It’s not yet known whether viral persistence in a woman infected prior to her pregnancy is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. The central nervous system is clearly a reservoir for persistent virus. Whole blood is now under study as possibly another. Semen poses a major challenge.

“There are case reports of Zika virus RNA being detected in semen for more than 6 months after the timing of infection, but we don’t yet know for how long it can be sexually transmitted. Is there really infectious virus present or just particles of RNA?” she said.

Resources

In partnership with the March of Dimes, the CDC has launched Zika Care Connect, a referral network of roughly 600 specialists in six high-risk states. Their ranks include specialists in maternal-fetal medicine, audiology, radiology, mental health, pediatric neurology, infectious diseases, developmental pediatrics, endocrinology, and pediatric ophthalmology. Another 10 states and at least 600 additional providers will soon be added to the referral network (www.zikacareconnect.org; 1-844-677-0447 toll-free).

Comprehensive, up-to-date Zika information is available to health care providers and the public through the CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/zika, at the Zika Pregnancy Hotline (770-488-7100), and by email at ZikaMCH@cdc.gov.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @ObGynNews

DENVER – One of many daunting challenges posed by the ongoing global Zika virus epidemic stems from the recent realization that the presence or absence of symptoms in women infected in pregnancy has no bearing on whether their babies will have Zika-associated birth defects, Margaret Honein, PhD, observed at the annual meeting of the Teratology Society.

This has profound clinical consequences because roughly 80% of all maternal Zika infections are asymptomatic or feature such mild symptoms that women don’t report them.

“There was, I think, some hope early on that symptoms in the mother would correlate with outcomes, but that has not been the case at all. In the U.S. population, we’ve seen about a 6% Zika-associated birth defects rate in both symptomatic and asymptomatic mothers,” said Dr. Honein, chief of the birth defects branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “We have a huge challenge in identifying the women who have asymptomatic infections, yet they’re at the same risk of having an adverse outcome in their baby.”[[{"fid":"199780","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","fields":

She provided conference attendees with the latest information on Zika, including preliminary results from ongoing CDC investigations. Along the way, she tackled many of the questions Zika experts hear most often from clinicians, while emphasizing that much about congenital Zika syndrome remains unknown.

Just how serious is the global threat of Zika virus infection?

On Feb. 8, 2016, the CDC activated a Level 1 emergency response to Zika. To put that into perspective, this is only the fourth time in history the agency has gone to Level 1. The other occasions were for Hurricane Katrina, the H1N1 pandemic flu, and Ebola.

“This is worse than thalidomide,” said Jan M. Friedman, MD, after listening to Dr. Honein and other speakers at the Zika update held during the conference. Dr. Friedman, a medical geneticist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, delivered the Robert L. Brent Lecture.

What is the level of risk for fetal/infant birth defects associated with maternal Zika virus infection?

The birth defect risk is somewhere between 5% and 10%, with the true figure probably being on the high end. Reports quoting risks on the lower end are based upon laboratory testing for maternal IgM antibodies, which couldn’t rule out cross reaction with other flaviviruses, including dengue virus, which is common in most of the same locales as Zika. Women who have been infected with dengue but not Zika are not at increased risk for birth defects. Zika is the first mosquito-borne virus to be recognized as teratogenic in humans.

The birth defects seen in conjunction with Zika infection are not unique. They can have many different causes. CDC investigators examined birth defects data from three states during the year before the Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere and determined that the background rate of microcephaly, neural tube defects, eye abnormalities, hearing loss, and other Zika-like birth defects was 3 per 1,000 live births. Among women with Zika virus infection in pregnancy, however, the rate is more than 20-fold higher at 50-100 per 1,000, according to Dr. Honein.

When during pregnancy does maternal Zika infection pose the highest risk to the fetus?

Studies published from Colombia and Brazil show the peak risk is when infection occurs during the first trimester or early in the second trimester. That’s consistent with the U.S. registry experience as well. Of note, the median time between development of maternal symptoms and the first notation of fetal microcephaly on ultrasound has been 18 weeks.

“This has important implications for women who’ve been infected. Just because they may have had two consecutive apparently normal monthly fetal ultrasounds doesn’t rule out by any means congenital Zika syndrome because there does appear to be a relatively long time period before these findings appear,” Dr. Honein noted.

What is the full range of potential health problems Zika infection can cause?

“What we’ve seen so far is definitely just the tip of the iceberg,” Dr. Honein cautioned. “It’s very severe, but I think we don’t yet know the full range of disabilities. There’s much more to come here.”

Most of the infants in the U.S. registry are just now reaching 1 year of age. Greater understanding of their neurodevelopment will require follow-up to age 2 or beyond.

Also, the information available to date on Zika-associated birth defects is based largely on scrutiny of infants with microcephaly along with any additional findings, such as chorioretinal scarring.

“We know relatively little about infants with only the other conditions – only hearing loss, for example, or only eye abnormalities,” Dr. Honein said. “While we know there are children who have microcephaly and they have needs, there may be a much larger number of children with lesser impairment, but who still have disabilities that are going to necessitate provision of services. Being prepared for that is very important.”

Reports from multiple countries make it clear that babies exposed to Zika in utero can have a normal-appearing head at birth but then become microcephalic later in their first year. The incidence of this phenomenon hasn’t yet been pinned down.

“We’ve learned in the last year and a-half that microcephaly is a key marker of some of the relevant underlying brain abnormalities, but microcephaly is not where our focus should be,” she said.

How long does Zika virus persist in the body?

The viremia typically lasts for anywhere from a few days up to 2 weeks. However, viral persistence for as long as 107 days has been documented in some pregnant women.

“I hesitate to put a number on it because every new publication has a longer figure,” Dr. Honein said.

It’s not yet known whether viral persistence in a woman infected prior to her pregnancy is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. The central nervous system is clearly a reservoir for persistent virus. Whole blood is now under study as possibly another. Semen poses a major challenge.

“There are case reports of Zika virus RNA being detected in semen for more than 6 months after the timing of infection, but we don’t yet know for how long it can be sexually transmitted. Is there really infectious virus present or just particles of RNA?” she said.

Resources

In partnership with the March of Dimes, the CDC has launched Zika Care Connect, a referral network of roughly 600 specialists in six high-risk states. Their ranks include specialists in maternal-fetal medicine, audiology, radiology, mental health, pediatric neurology, infectious diseases, developmental pediatrics, endocrinology, and pediatric ophthalmology. Another 10 states and at least 600 additional providers will soon be added to the referral network (www.zikacareconnect.org; 1-844-677-0447 toll-free).

Comprehensive, up-to-date Zika information is available to health care providers and the public through the CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/zika, at the Zika Pregnancy Hotline (770-488-7100), and by email at ZikaMCH@cdc.gov.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @ObGynNews

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM TERATOLOGY SOCIETY 2017

What is the best approach for managing CIED infections?

The case

A 72-year-old man with ischemic cardiomyopathy and left-ventricular ejection fraction of 15% had an cardioverter-defibrillator implanted five years ago for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. He was brought to the emergency department by his daughter who noticed erythema and swelling over the generator pocket site. His temperature is 100.1° F. Vital signs are otherwise normal and stable.

What are the best initial and definitive management strategies for this patient?

When should a cardiac implanted electronic device (CIED) infection be suspected?

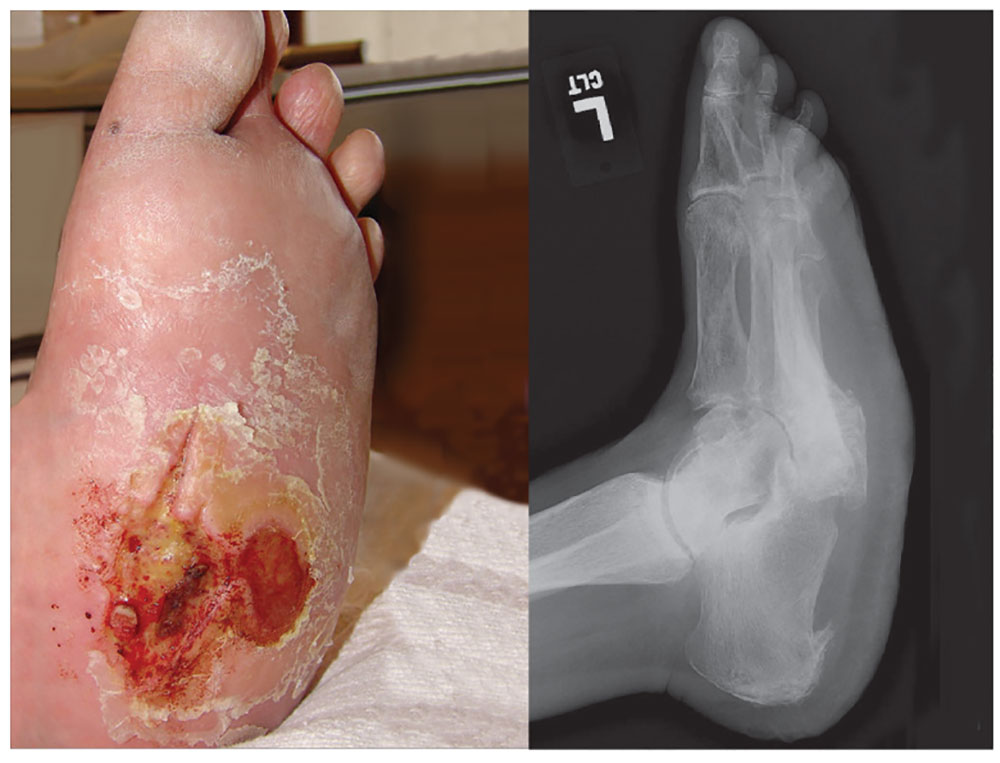

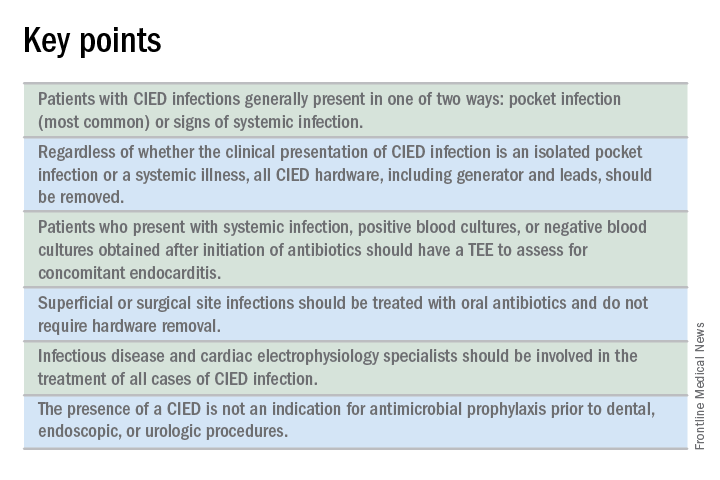

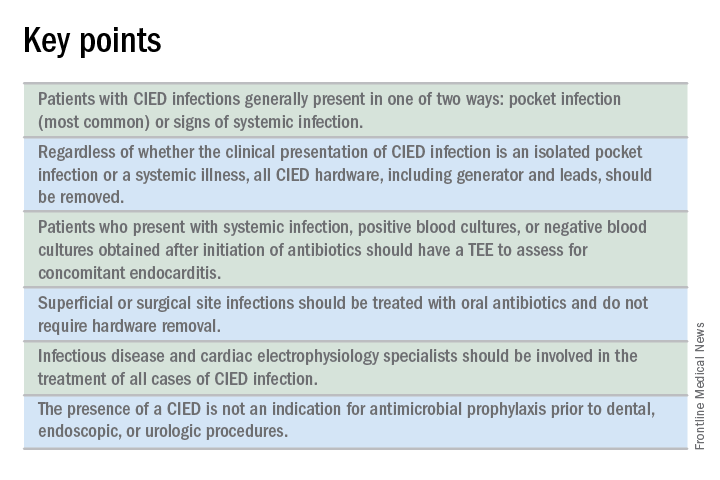

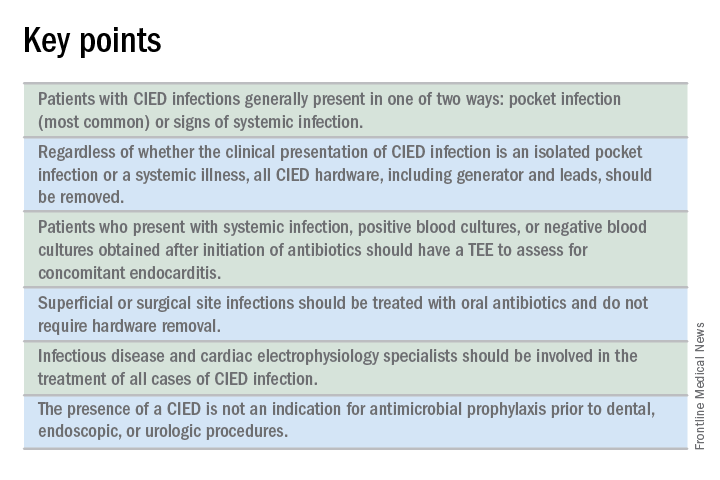

CIED infections generally present in one of two ways: as a local generator pocket infection or as a systemic illness.1 Around 70% of CIED infections present with findings related to the generator pocket site. Findings in such cases include pain, swelling, erythema, induration, and ulceration. Systemic findings range from vague constitutional symptoms to overt sepsis. It is important to note that systemic signs of infection are only present in the minority of cases. Their absence does not rule out a CIED infection.1,2 As such, hospitalists must maintain a high index of suspicion in order to avoid missing the diagnosis.

Unfortunately, it can be difficult to distinguish between a CIED infection and less severe postimplantation complications such as surgical site infections, superficial pocket site infections, and noninfected hematoma.2

What are the risk factors for CIED infections?

The risk factors for CIED infection fit into three broad categories: procedure, patient, and pathogen.

Procedural factors that increase risk of infection include lack of periprocedural antimicrobial prophylaxis, inexperienced physician operator, multiple revision procedures, hematoma formation at the pocket site, and increased amount of hardware.1

Patient factors center on medical comorbidities, including congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, and ongoing oral anticoagulation.1

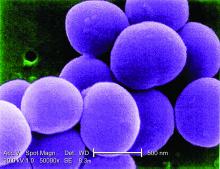

The specific pathogen also plays a role in infection risk. In one cohort study of 1,524 patients with CIEDs, patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia ended up having confirmed or suspected CIED infections in 54.6% of cases, compared with just 12.0% of patients who had bacteremia with gram-negative bacilli.3

Which bacteria cause most CIED infections?

The vast majority of CIED infections are caused by gram-positive bacteria.1,4 An Italian study of 1,204 patients with CIED infection reported that pathogens isolated from extracted leads were gram-positive bacteria in 92.5% of infections.4 Staph species are the most common pathogens. Coagulase-negative staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus accounted for 69% and 13.8% of all isolates, respectively. Of note, 33% of CoNS isolates and 13% of S. aureus isolates were resistant to oxacillin in that study.4

Which initial diagnostic tests should be performed?

Patients should have two sets of blood cultures drawn from two separate sites, prior to administration of antibiotics.1 Current guidelines recommend against aspiration of a suspected infected pocket site because the sensitivity for identifying the causal pathogen is low while the risk of introducing infection to the generator pocket is substantial.1 In the event of CIED removal, pocket tissue and lead tips should be sent for gram stain and culture.1

Do all patients require a transesophageal echocardiogram?

Guidelines recommend a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) if suspicion for CIED infection is high based on positive blood cultures, antibiotic initiation prior to culture collection, ongoing systemic illness, or other suggestive signs.1,2 Positive transthoracic echocardiogram findings (for example, a valve vegetation) do not obviate the need for TEE because of the possibility of other relevant complications (including endocarditis and perivalvular extension) for which TEE has a greater sensitivity.1

What is the approach to antimicrobial therapy?

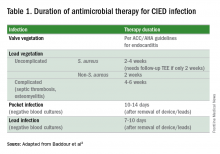

Since most infections involve staphylococcus species, initial empiric antimicrobial therapy should cover both oxacillin-sensitive and oxacillin-resistant strains. Thus, intravenous vancomycin is an appropriate initial choice.1 Culture and sensitivity results should then guide specific therapy decisions.1 Table 1 provides a summary of strategies for antimicrobial selection and duration.

Should all patients undergo complete device removal?

All patients with CIED infection require complete device removal, even if the infection is suspected to be confined to the generator pocket and blood cultures remain negative.2 Patients with superficial or surgical site infections without CIED infection do not require complete device removal. Rather, those cases can be managed with a 7- to 10-day course of oral antimicrobials.1

After device removal, what is the appropriate timing for installing a new device?

The decision to implant a replacement device is often made with input from infectious disease and cardiac electrophysiology experts. The decision must consider both infection and device-related concerns. Importantly, repeat blood cultures must be negative, and any infection in the pocket site should be controlled prior to installing a new device.2

Should all patients with a CIED receive antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to invasive dental, urologic, or endoscopic procedures?

No. Merely having a CIED is not considered an indication for antimicrobial prophylaxis.2

Back to the case

Two sets of blood cultures are drawn, and vancomycin is started as empiric therapy. The culture results show CoNS species, and antimicrobial resistance testing shows oxacillin-resistance.

TEE shows a vegetation on one of the leads but no vegetation on any of the heart valves. Cardiac electrophysiology is consulted and performs a percutaneous extraction of the entire device (generator and leads). Starting on the day of extraction, the patient undergoes two weeks of intravenous antimicrobial therapy with vancomycin. The patient, his family, and the electrophysiology team discuss the patient’s wishes, indications, and potential burdens related to device replacement.

He ultimately decides to have a replacement device installed. An infectious disease specialist is consulted to help define appropriate timing of the new device installation procedure.

Bottom line

The patient clearly had a CIED infection which required TEE, extraction of his CIED, and prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Dr. Davisson is a primary care physician at Community Health Network in Indianapolis, Ind. Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist at the Lexington VA Medical Center. Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and the Lexington VA Medical Center.

References

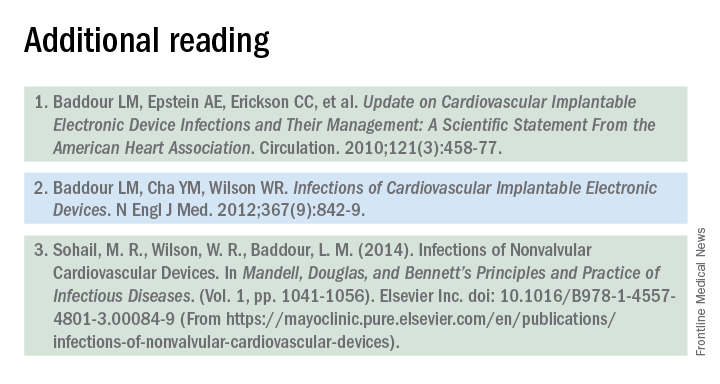

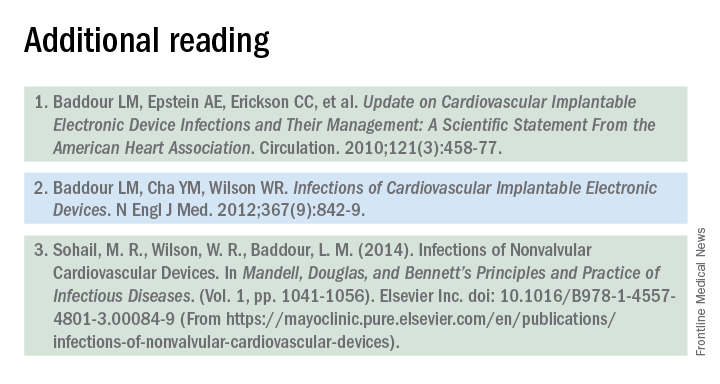

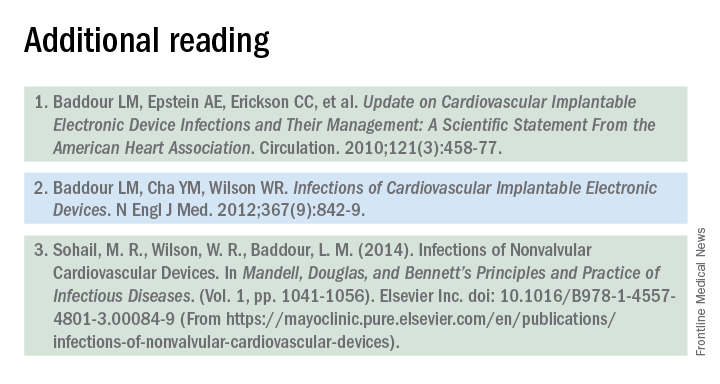

1. Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, et al. Update on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infections and Their Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(3):458-77.

2. Baddour LM, Cha YM, Wilson WR. Infections of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):842-9.

3. Uslan DZ, Sohail MR, St. Sauver JL, et al. Permanent Pacemaker and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Infection: A Population-Based Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):669-75.

4. Bongiorni MG, Tascini C, Tagliaferri E, et al. Microbiology of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infections. Europace. 2012;14(9):1334-9.

The case

A 72-year-old man with ischemic cardiomyopathy and left-ventricular ejection fraction of 15% had an cardioverter-defibrillator implanted five years ago for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. He was brought to the emergency department by his daughter who noticed erythema and swelling over the generator pocket site. His temperature is 100.1° F. Vital signs are otherwise normal and stable.

What are the best initial and definitive management strategies for this patient?

When should a cardiac implanted electronic device (CIED) infection be suspected?

CIED infections generally present in one of two ways: as a local generator pocket infection or as a systemic illness.1 Around 70% of CIED infections present with findings related to the generator pocket site. Findings in such cases include pain, swelling, erythema, induration, and ulceration. Systemic findings range from vague constitutional symptoms to overt sepsis. It is important to note that systemic signs of infection are only present in the minority of cases. Their absence does not rule out a CIED infection.1,2 As such, hospitalists must maintain a high index of suspicion in order to avoid missing the diagnosis.

Unfortunately, it can be difficult to distinguish between a CIED infection and less severe postimplantation complications such as surgical site infections, superficial pocket site infections, and noninfected hematoma.2

What are the risk factors for CIED infections?

The risk factors for CIED infection fit into three broad categories: procedure, patient, and pathogen.

Procedural factors that increase risk of infection include lack of periprocedural antimicrobial prophylaxis, inexperienced physician operator, multiple revision procedures, hematoma formation at the pocket site, and increased amount of hardware.1

Patient factors center on medical comorbidities, including congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, and ongoing oral anticoagulation.1

The specific pathogen also plays a role in infection risk. In one cohort study of 1,524 patients with CIEDs, patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia ended up having confirmed or suspected CIED infections in 54.6% of cases, compared with just 12.0% of patients who had bacteremia with gram-negative bacilli.3

Which bacteria cause most CIED infections?

The vast majority of CIED infections are caused by gram-positive bacteria.1,4 An Italian study of 1,204 patients with CIED infection reported that pathogens isolated from extracted leads were gram-positive bacteria in 92.5% of infections.4 Staph species are the most common pathogens. Coagulase-negative staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus accounted for 69% and 13.8% of all isolates, respectively. Of note, 33% of CoNS isolates and 13% of S. aureus isolates were resistant to oxacillin in that study.4

Which initial diagnostic tests should be performed?

Patients should have two sets of blood cultures drawn from two separate sites, prior to administration of antibiotics.1 Current guidelines recommend against aspiration of a suspected infected pocket site because the sensitivity for identifying the causal pathogen is low while the risk of introducing infection to the generator pocket is substantial.1 In the event of CIED removal, pocket tissue and lead tips should be sent for gram stain and culture.1

Do all patients require a transesophageal echocardiogram?

Guidelines recommend a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) if suspicion for CIED infection is high based on positive blood cultures, antibiotic initiation prior to culture collection, ongoing systemic illness, or other suggestive signs.1,2 Positive transthoracic echocardiogram findings (for example, a valve vegetation) do not obviate the need for TEE because of the possibility of other relevant complications (including endocarditis and perivalvular extension) for which TEE has a greater sensitivity.1

What is the approach to antimicrobial therapy?

Since most infections involve staphylococcus species, initial empiric antimicrobial therapy should cover both oxacillin-sensitive and oxacillin-resistant strains. Thus, intravenous vancomycin is an appropriate initial choice.1 Culture and sensitivity results should then guide specific therapy decisions.1 Table 1 provides a summary of strategies for antimicrobial selection and duration.

Should all patients undergo complete device removal?

All patients with CIED infection require complete device removal, even if the infection is suspected to be confined to the generator pocket and blood cultures remain negative.2 Patients with superficial or surgical site infections without CIED infection do not require complete device removal. Rather, those cases can be managed with a 7- to 10-day course of oral antimicrobials.1

After device removal, what is the appropriate timing for installing a new device?

The decision to implant a replacement device is often made with input from infectious disease and cardiac electrophysiology experts. The decision must consider both infection and device-related concerns. Importantly, repeat blood cultures must be negative, and any infection in the pocket site should be controlled prior to installing a new device.2

Should all patients with a CIED receive antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to invasive dental, urologic, or endoscopic procedures?

No. Merely having a CIED is not considered an indication for antimicrobial prophylaxis.2

Back to the case

Two sets of blood cultures are drawn, and vancomycin is started as empiric therapy. The culture results show CoNS species, and antimicrobial resistance testing shows oxacillin-resistance.

TEE shows a vegetation on one of the leads but no vegetation on any of the heart valves. Cardiac electrophysiology is consulted and performs a percutaneous extraction of the entire device (generator and leads). Starting on the day of extraction, the patient undergoes two weeks of intravenous antimicrobial therapy with vancomycin. The patient, his family, and the electrophysiology team discuss the patient’s wishes, indications, and potential burdens related to device replacement.

He ultimately decides to have a replacement device installed. An infectious disease specialist is consulted to help define appropriate timing of the new device installation procedure.

Bottom line

The patient clearly had a CIED infection which required TEE, extraction of his CIED, and prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Dr. Davisson is a primary care physician at Community Health Network in Indianapolis, Ind. Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist at the Lexington VA Medical Center. Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and the Lexington VA Medical Center.

References

1. Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, et al. Update on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infections and Their Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(3):458-77.

2. Baddour LM, Cha YM, Wilson WR. Infections of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):842-9.

3. Uslan DZ, Sohail MR, St. Sauver JL, et al. Permanent Pacemaker and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Infection: A Population-Based Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):669-75.

4. Bongiorni MG, Tascini C, Tagliaferri E, et al. Microbiology of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infections. Europace. 2012;14(9):1334-9.

The case

A 72-year-old man with ischemic cardiomyopathy and left-ventricular ejection fraction of 15% had an cardioverter-defibrillator implanted five years ago for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. He was brought to the emergency department by his daughter who noticed erythema and swelling over the generator pocket site. His temperature is 100.1° F. Vital signs are otherwise normal and stable.

What are the best initial and definitive management strategies for this patient?

When should a cardiac implanted electronic device (CIED) infection be suspected?

CIED infections generally present in one of two ways: as a local generator pocket infection or as a systemic illness.1 Around 70% of CIED infections present with findings related to the generator pocket site. Findings in such cases include pain, swelling, erythema, induration, and ulceration. Systemic findings range from vague constitutional symptoms to overt sepsis. It is important to note that systemic signs of infection are only present in the minority of cases. Their absence does not rule out a CIED infection.1,2 As such, hospitalists must maintain a high index of suspicion in order to avoid missing the diagnosis.

Unfortunately, it can be difficult to distinguish between a CIED infection and less severe postimplantation complications such as surgical site infections, superficial pocket site infections, and noninfected hematoma.2

What are the risk factors for CIED infections?

The risk factors for CIED infection fit into three broad categories: procedure, patient, and pathogen.

Procedural factors that increase risk of infection include lack of periprocedural antimicrobial prophylaxis, inexperienced physician operator, multiple revision procedures, hematoma formation at the pocket site, and increased amount of hardware.1

Patient factors center on medical comorbidities, including congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, and ongoing oral anticoagulation.1

The specific pathogen also plays a role in infection risk. In one cohort study of 1,524 patients with CIEDs, patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia ended up having confirmed or suspected CIED infections in 54.6% of cases, compared with just 12.0% of patients who had bacteremia with gram-negative bacilli.3

Which bacteria cause most CIED infections?

The vast majority of CIED infections are caused by gram-positive bacteria.1,4 An Italian study of 1,204 patients with CIED infection reported that pathogens isolated from extracted leads were gram-positive bacteria in 92.5% of infections.4 Staph species are the most common pathogens. Coagulase-negative staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus accounted for 69% and 13.8% of all isolates, respectively. Of note, 33% of CoNS isolates and 13% of S. aureus isolates were resistant to oxacillin in that study.4

Which initial diagnostic tests should be performed?

Patients should have two sets of blood cultures drawn from two separate sites, prior to administration of antibiotics.1 Current guidelines recommend against aspiration of a suspected infected pocket site because the sensitivity for identifying the causal pathogen is low while the risk of introducing infection to the generator pocket is substantial.1 In the event of CIED removal, pocket tissue and lead tips should be sent for gram stain and culture.1

Do all patients require a transesophageal echocardiogram?

Guidelines recommend a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) if suspicion for CIED infection is high based on positive blood cultures, antibiotic initiation prior to culture collection, ongoing systemic illness, or other suggestive signs.1,2 Positive transthoracic echocardiogram findings (for example, a valve vegetation) do not obviate the need for TEE because of the possibility of other relevant complications (including endocarditis and perivalvular extension) for which TEE has a greater sensitivity.1

What is the approach to antimicrobial therapy?

Since most infections involve staphylococcus species, initial empiric antimicrobial therapy should cover both oxacillin-sensitive and oxacillin-resistant strains. Thus, intravenous vancomycin is an appropriate initial choice.1 Culture and sensitivity results should then guide specific therapy decisions.1 Table 1 provides a summary of strategies for antimicrobial selection and duration.

Should all patients undergo complete device removal?

All patients with CIED infection require complete device removal, even if the infection is suspected to be confined to the generator pocket and blood cultures remain negative.2 Patients with superficial or surgical site infections without CIED infection do not require complete device removal. Rather, those cases can be managed with a 7- to 10-day course of oral antimicrobials.1

After device removal, what is the appropriate timing for installing a new device?

The decision to implant a replacement device is often made with input from infectious disease and cardiac electrophysiology experts. The decision must consider both infection and device-related concerns. Importantly, repeat blood cultures must be negative, and any infection in the pocket site should be controlled prior to installing a new device.2

Should all patients with a CIED receive antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to invasive dental, urologic, or endoscopic procedures?

No. Merely having a CIED is not considered an indication for antimicrobial prophylaxis.2

Back to the case

Two sets of blood cultures are drawn, and vancomycin is started as empiric therapy. The culture results show CoNS species, and antimicrobial resistance testing shows oxacillin-resistance.

TEE shows a vegetation on one of the leads but no vegetation on any of the heart valves. Cardiac electrophysiology is consulted and performs a percutaneous extraction of the entire device (generator and leads). Starting on the day of extraction, the patient undergoes two weeks of intravenous antimicrobial therapy with vancomycin. The patient, his family, and the electrophysiology team discuss the patient’s wishes, indications, and potential burdens related to device replacement.

He ultimately decides to have a replacement device installed. An infectious disease specialist is consulted to help define appropriate timing of the new device installation procedure.

Bottom line

The patient clearly had a CIED infection which required TEE, extraction of his CIED, and prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Dr. Davisson is a primary care physician at Community Health Network in Indianapolis, Ind. Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist at the Lexington VA Medical Center. Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and the Lexington VA Medical Center.

References

1. Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, et al. Update on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infections and Their Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(3):458-77.

2. Baddour LM, Cha YM, Wilson WR. Infections of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):842-9.

3. Uslan DZ, Sohail MR, St. Sauver JL, et al. Permanent Pacemaker and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Infection: A Population-Based Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):669-75.

4. Bongiorni MG, Tascini C, Tagliaferri E, et al. Microbiology of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infections. Europace. 2012;14(9):1334-9.

Stressful life events take greater cognitive toll on African Americans than whites

LONDON – African Americans not only report experiencing more stressful experiences across their lifespans than do whites, but they have more cognitive consequences from them as well, new research suggests.

In fact, the weight of these experiences affected cognition even more than traditional risk factors like genetic status and even age, Megan Zuelsdorff, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Racial disparities have long been evident in the development and progression of dementia, Dr. Zuelsdorff said. Socioeconomic factors are also important players in this scenario. Stress, likewise, has long been linked to poorer cognitive health. “But, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge of stress and cognition. The contribution of stress to well-established socioeconomic impacts on health is unclear, and the research focus here has always been on events happening in midlife and onward. But, it’s crucial to expand this window of time backward to include earlier years. If we look at a graph of cognitive function across the lifespan, the rate of decline doesn’t vary much. What we do see is that blacks, starting at midlife, are closer to the clinical threshold of cognitive impairment and may reach the threshold at an earlier age. What this said to me is that we needed to look at these earlier life factors that could bring someone to this state of lower cognitive function in midlife.”

Dr. Zuelsdorff and her colleagues analyzed data from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention to examine this question. The observational study comprises 1,500 adults being followed for 15-20 years and is enriched for those with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease. The main goal of WRAP is to understand the biological, medical, environmental, and lifestyle factors that increase a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Subjects have a study visit every 2-4 years that includes a full physical and cognitive workup. At one visit, Dr. Zuelsdorff said, they were asked to complete a questionnaire concerning 27 different stressful life events. These experiences were deeply disturbing and potentially life altering. They included childhood experiences, such as parental abuse, alcoholism, and flunking out of school, and adult experiences, such as combat experience, bankruptcy, or the death of a child. She then analyzed how the total number of stressful events in a person’s life changed that person’s risk of developing dementia.

Of the entire WRAP cohort, 1,314 completed the stress questionnaire and had sufficient cognitive data. These subjects were largely white (1,232). Only 82 were African American, a weakness of the study, Dr. Zuelsdorff noted, but a reflection of Wisconsin’s racial makeup.

They were similar in a number of important ways, including age (mean, 58 years), proportion of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) allele carriers (38%), and years of education (mean, 16). African Americans had higher body mass index (33.3 vs. 28.8 kg/m2), reported less physical activity, were more often current smokers (22% vs. 6%), and had a lower-quality education despite similar time in the classroom.

On average, African Americans reported a mean of 4.5 stressful life events – a significant, 60% increase over the 2.8 reported by whites. The experience of stressful events directly influenced a subject’s performance in the speed and flexibility domain of executive function and in working memory, Dr. Zuelsdorff said.

“We saw a substantial 13.5% attenuation of performance on speed and flexibility, but we also saw attenuation in working memory. That told us something else was going on – that it wasn’t just the accumulation of stressful events but that there was a differential vulnerability. The negative association between lifetime stressful events and the cognitive domains was much stronger in blacks than in whites.”

She then conducted a risk analysis to determine the impact of stress. “Stress was right at the top for blacks. It tended to be one of the most important predictors of cognitive function. The only other one that came out as significant was quality of education. The social environment in this sample was more important than the traditional risk factors of genetics and chronological age.”

The study barely scratches the surface of the stress/cognition conundrum, Dr. Zuelsdorff said. “We would like to look at the timing next and see if there is some critical window that is especially influencing to cognitive health. We then need to target both interventions and effect modifiers, such as social, community, and financial resources that might buffer the effects of this negative stress.”

She had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

LONDON – African Americans not only report experiencing more stressful experiences across their lifespans than do whites, but they have more cognitive consequences from them as well, new research suggests.

In fact, the weight of these experiences affected cognition even more than traditional risk factors like genetic status and even age, Megan Zuelsdorff, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Racial disparities have long been evident in the development and progression of dementia, Dr. Zuelsdorff said. Socioeconomic factors are also important players in this scenario. Stress, likewise, has long been linked to poorer cognitive health. “But, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge of stress and cognition. The contribution of stress to well-established socioeconomic impacts on health is unclear, and the research focus here has always been on events happening in midlife and onward. But, it’s crucial to expand this window of time backward to include earlier years. If we look at a graph of cognitive function across the lifespan, the rate of decline doesn’t vary much. What we do see is that blacks, starting at midlife, are closer to the clinical threshold of cognitive impairment and may reach the threshold at an earlier age. What this said to me is that we needed to look at these earlier life factors that could bring someone to this state of lower cognitive function in midlife.”

Dr. Zuelsdorff and her colleagues analyzed data from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention to examine this question. The observational study comprises 1,500 adults being followed for 15-20 years and is enriched for those with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease. The main goal of WRAP is to understand the biological, medical, environmental, and lifestyle factors that increase a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Subjects have a study visit every 2-4 years that includes a full physical and cognitive workup. At one visit, Dr. Zuelsdorff said, they were asked to complete a questionnaire concerning 27 different stressful life events. These experiences were deeply disturbing and potentially life altering. They included childhood experiences, such as parental abuse, alcoholism, and flunking out of school, and adult experiences, such as combat experience, bankruptcy, or the death of a child. She then analyzed how the total number of stressful events in a person’s life changed that person’s risk of developing dementia.

Of the entire WRAP cohort, 1,314 completed the stress questionnaire and had sufficient cognitive data. These subjects were largely white (1,232). Only 82 were African American, a weakness of the study, Dr. Zuelsdorff noted, but a reflection of Wisconsin’s racial makeup.

They were similar in a number of important ways, including age (mean, 58 years), proportion of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) allele carriers (38%), and years of education (mean, 16). African Americans had higher body mass index (33.3 vs. 28.8 kg/m2), reported less physical activity, were more often current smokers (22% vs. 6%), and had a lower-quality education despite similar time in the classroom.

On average, African Americans reported a mean of 4.5 stressful life events – a significant, 60% increase over the 2.8 reported by whites. The experience of stressful events directly influenced a subject’s performance in the speed and flexibility domain of executive function and in working memory, Dr. Zuelsdorff said.

“We saw a substantial 13.5% attenuation of performance on speed and flexibility, but we also saw attenuation in working memory. That told us something else was going on – that it wasn’t just the accumulation of stressful events but that there was a differential vulnerability. The negative association between lifetime stressful events and the cognitive domains was much stronger in blacks than in whites.”

She then conducted a risk analysis to determine the impact of stress. “Stress was right at the top for blacks. It tended to be one of the most important predictors of cognitive function. The only other one that came out as significant was quality of education. The social environment in this sample was more important than the traditional risk factors of genetics and chronological age.”

The study barely scratches the surface of the stress/cognition conundrum, Dr. Zuelsdorff said. “We would like to look at the timing next and see if there is some critical window that is especially influencing to cognitive health. We then need to target both interventions and effect modifiers, such as social, community, and financial resources that might buffer the effects of this negative stress.”

She had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

LONDON – African Americans not only report experiencing more stressful experiences across their lifespans than do whites, but they have more cognitive consequences from them as well, new research suggests.

In fact, the weight of these experiences affected cognition even more than traditional risk factors like genetic status and even age, Megan Zuelsdorff, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Racial disparities have long been evident in the development and progression of dementia, Dr. Zuelsdorff said. Socioeconomic factors are also important players in this scenario. Stress, likewise, has long been linked to poorer cognitive health. “But, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge of stress and cognition. The contribution of stress to well-established socioeconomic impacts on health is unclear, and the research focus here has always been on events happening in midlife and onward. But, it’s crucial to expand this window of time backward to include earlier years. If we look at a graph of cognitive function across the lifespan, the rate of decline doesn’t vary much. What we do see is that blacks, starting at midlife, are closer to the clinical threshold of cognitive impairment and may reach the threshold at an earlier age. What this said to me is that we needed to look at these earlier life factors that could bring someone to this state of lower cognitive function in midlife.”

Dr. Zuelsdorff and her colleagues analyzed data from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention to examine this question. The observational study comprises 1,500 adults being followed for 15-20 years and is enriched for those with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease. The main goal of WRAP is to understand the biological, medical, environmental, and lifestyle factors that increase a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Subjects have a study visit every 2-4 years that includes a full physical and cognitive workup. At one visit, Dr. Zuelsdorff said, they were asked to complete a questionnaire concerning 27 different stressful life events. These experiences were deeply disturbing and potentially life altering. They included childhood experiences, such as parental abuse, alcoholism, and flunking out of school, and adult experiences, such as combat experience, bankruptcy, or the death of a child. She then analyzed how the total number of stressful events in a person’s life changed that person’s risk of developing dementia.

Of the entire WRAP cohort, 1,314 completed the stress questionnaire and had sufficient cognitive data. These subjects were largely white (1,232). Only 82 were African American, a weakness of the study, Dr. Zuelsdorff noted, but a reflection of Wisconsin’s racial makeup.

They were similar in a number of important ways, including age (mean, 58 years), proportion of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) allele carriers (38%), and years of education (mean, 16). African Americans had higher body mass index (33.3 vs. 28.8 kg/m2), reported less physical activity, were more often current smokers (22% vs. 6%), and had a lower-quality education despite similar time in the classroom.

On average, African Americans reported a mean of 4.5 stressful life events – a significant, 60% increase over the 2.8 reported by whites. The experience of stressful events directly influenced a subject’s performance in the speed and flexibility domain of executive function and in working memory, Dr. Zuelsdorff said.

“We saw a substantial 13.5% attenuation of performance on speed and flexibility, but we also saw attenuation in working memory. That told us something else was going on – that it wasn’t just the accumulation of stressful events but that there was a differential vulnerability. The negative association between lifetime stressful events and the cognitive domains was much stronger in blacks than in whites.”

She then conducted a risk analysis to determine the impact of stress. “Stress was right at the top for blacks. It tended to be one of the most important predictors of cognitive function. The only other one that came out as significant was quality of education. The social environment in this sample was more important than the traditional risk factors of genetics and chronological age.”

The study barely scratches the surface of the stress/cognition conundrum, Dr. Zuelsdorff said. “We would like to look at the timing next and see if there is some critical window that is especially influencing to cognitive health. We then need to target both interventions and effect modifiers, such as social, community, and financial resources that might buffer the effects of this negative stress.”

She had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT AAIC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: African Americans reported 60% more stressful life events than whites, which were tied to a 13% decrease in the speed and flexibility domain of executive function.

Data source: The observational cohort study comprised 1,314 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Zuelsdorff had no financial disclosures.

Symptoms Mimicking Those of Hypokalemic Periodic Paralysis Induced by Soluble Barium Poisoning

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) is a relatively common and potentially life-threating condition that can be either sporadic or recurring and has both inherited and acquired causes.1 Familial HPP, on the other hand, is a rare condition (1:100,000) caused by loss of function mutations leading to the disruption of membrane potential consequently making them inexcitable.2 Appearance of symptoms is typically in the first or second decade of life (60% of cases have onset aged < 16 years) with susceptible individuals experiencing sudden onset of perioral numbness; weakness; centrifugal paralysis, often with nausea; vomiting and diarrhea; and prostration, usually triggered by highcarbohydrate meals and rest following sustained muscle-group use.3

These symptoms are common to all forms of HPP, making the differential diagnosis wide and confusing. Rhabdomyolysis is occasionally associated with many severe hypokalemic episodes.4 Myopathy and permanent muscle weakness have been reported in HPP.5,6 Other reported inciting factors include a drop in serum potassium caused by β-adrenergic bronchodilator treatment.7 Clinical attacks also have been associated with diabetic ketoacidosis and combined hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia.8 Thyrotoxicosis also causes similar muscle action potential changes but only when hyperthyroidism is uncorrected. 9-12 Less commonly, hypothyroidism has been reported to be associated with hypokalemic paralysis.3

Pa Ping, a condition involving hypokalemic paralysis of uncertain etiology, is geographically centered in the Szechuan region of China.13 Cases of Bartter, Liddle, and Gitelman syndromes also have been associated with hypokalemic paralysis.3,14 There is an association with malignant hyperthermia following or during systemic anesthesia. Patients presenting as Guillain-Barré syndrome have been found to have periodic paralysis triggered by hypokalemia from any cause.15 Sjögren syndrome and renal tubular acidosis also are reported to have triggered symptoms of hypokalemic paralysis.16,17

True type 1 HPP is caused by channelopathies resulting from mutations in the calcium channel gene CACN1AS (HypoPP1), which accounts for 70% of the cases, whereas type 2 HPP is cause by sodium channel gene SCN4A (HypoPP2) mutations, which accounts for 10% to 20% of cases.18,19 An association with a voltage-gated potassium channel KCNE3 mutation has been made but is disputed.20,21 Females typically have less severe and less frequent attacks, and attacks lessen or disappear during pregnancy.22

In a small controlled trial, acetazolamide has been reported to have prophylactic benefit, although a more powerful carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, dichlorophenamide, was reported to be effective in a study after acetazolamide had become ineffective.23,24 These treatments would not be expected to be of clinical use in hypokalemia due to barium poisoning.

Barium poisoning has been reported as a result of accidental contamination of foodstuffs with soluble barium.25 Onset of symptoms is rapid, with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and malaise followed rapidly by weakness, which can include the muscles of respiration. This littleconsidered but rapidly lethal poisoning event can be accidental as a result of environmental exposure due to unintentional ingestion of the toxin or deliberate criminal poisoning as in this case. Because deliberate poisoning rarely crosses the mind of the clinician, awareness of the potential similarity of barium poisoning to other forms of HPP and even familial HPP is important.

Case Presentation

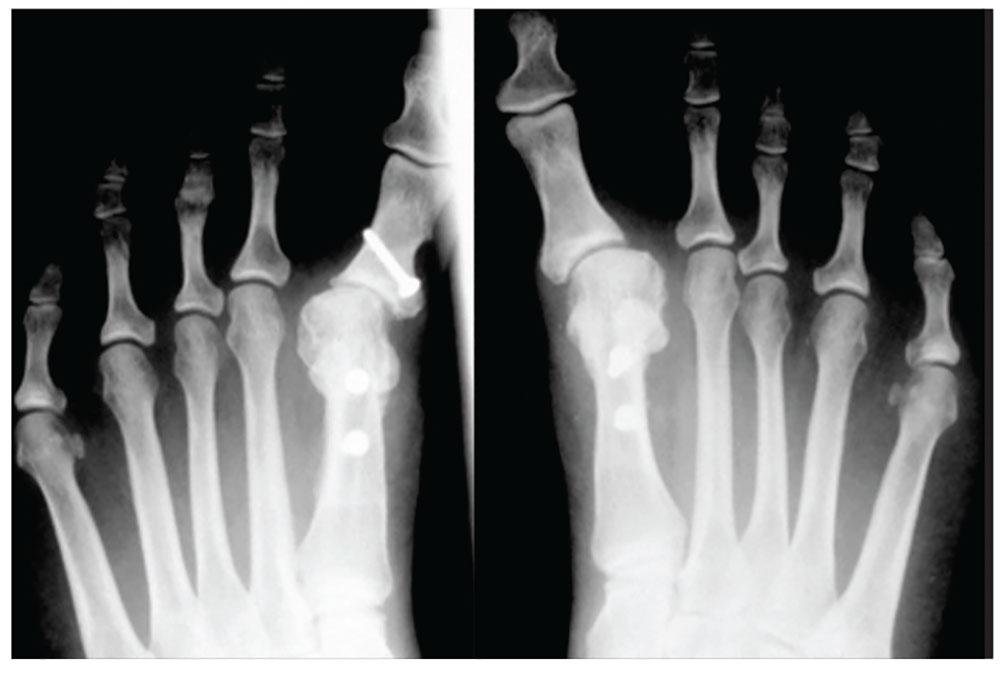

A male veteran aged 45 years when treated by the authors was well until moving into a new rural home when he began to experience acute episodes of variable perioral numbness, diarrhea, paresthesias, abdominal cramping, and weakness, which ranged from mild, self-terminating extremity weakness to 3 episodes of respiratory failure that required intubation and mechanical ventilation.

All episodes were accompanied by hypokalemia in the range of 2 to 3 mEq/L, but levels varied erratically during admissions from severe hypokalemia to normo- and hyperkalemia. Over 3 years, the patient was admitted to the hospital 19 times, underwent extensive workup, and was referred to endocrinology services at Duke University, Vanderbilt University, and the Cleveland Clinic. Diagnostic efforts centered on establishing whether he had a latepresenting variant of familial HPP.

Genetic evaluations could not identify known single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with that condition. The consensus was that he had a potassium leak somewhere between his kidneys and bladder. Recommended management was a high baseline oral potassium supplementation and spironolactone. He had a brief period of improvement after moving to a different house, but the episodes returned once he moved back to his old house despite adherence to recommended treatment. In December 2012, he experienced his worst episode, with potassium 1.8 mEq/L on admission, resulting in admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Following a precipitous clinical decline, the patient was intubated and mechanically ventilated. Nephrology was consulted and given the recurrent life-threatening pattern, an intensive chart review was undertaken. It was noted that a urine arsenic level that had been normal several admissions previously at 18 μg/L was elevated during a subsequent admission at 59 μg/L, and several weeks later during a later admission the level had fallen to 15 μg/L. Urine lead was undetectable on 3 occasions, and urine mercury was within normal limits.

Arsenic toxicity did not match the patient’s clinical syndrome, but the pattern seemed to be consistent with the possibility of unexplained toxic exposure and subsequent clearance. Therefore, an intensive literature search for syndromes of environmental exposure or poisoning resembling HPP was undertaken. The search revealed several references in the literature to paralysis similar to HPP that involved ingestion of hair-removing soap and rat poison containing barium sulfide and carbonate. References also pointed to the similarity of the symptoms to Guillain-Barre syndrome.

As a result of that literature search, a blood barium level was collected in the ICU that revealed 14,550 ng/mL. A scalp hair sample showed 6.1 μg barium per gram of hair (reference, 0.53 μg/g to 2 μg/g). Neither the patient nor his wife reported being involved in painting, ceramic work, decorating glassware or fabric with dyes, working with stained glass, smelting, metal welding, or use of vermicides.

A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency team was sent to the house, and a detailed toxic survey of the house and the surrounding grounds was conducted with no excess barium found. Barium levels were checked by a private physician on the wife and 2 minor children. The wife’s barium levels came back undetectable in a blood sample and elevated in a hair sample. One child had a very low detected level in her blood and slightly elevated in her hair, and the other child had a low level in her blood and her hair. Because the circumstances of the wife’s and children’s exposure could not be explained environmentally nor could the veteran’s exposure source be identified, the VA Police Service contacted the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, and they questioned the veteran and his wife.

Shortly after that the veteran received a paralyzing gunshot wound to the back, and the ensuing investigation resulted in incarceration of his wife for both attempted murder by firearm and serial poisoning after soluble barium-containing materials were found hidden in the house.

Discussion

Human barium poisoning is a rarely reported toxic exposure that results in rapid onset of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, progressive weakness that may end in respiratory paralysis and death if intubation and mechanical ventilation are not promptly initiated. Although the barium found in radiographic contrast media is highly insoluble, ingested barium carbonate and sulfide are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream, reaching high levels quickly and altering the conductance of potassium channels. The result is erratic variation in blood potassium and prolonged paralysis unless it is immediately suspected and hemodialysis is initiated. In this case, the suspicion level at the time of intubation was insufficient to justify initiating acute hemodialysis.

Soluble barium is available from a number of open sources. Depilatory powders and several rat poisons list barium sulfide or carbonate, both soluble forms of barium rapidly absorbed through the gastrointestinal mucosa, as a major ingredient. One celebrated 2012 case in a city near Chattanooga, Tennessee, involved allegations of barium carbonate poisoning involving rat poison mixed into coffee creamer, but no charges could be filed because the sample handling precluded definitive linkage. Another deliberate toxic poisoning in Texas was traced to soluble barium introduced into a father’s food by his daughter.

The patient reported here experienced 3 years and 19 admissions with 3 episodes of mechanical intubation before his suspected variant HPP was recognized as actually being due to soluble barium poisoning.

Barium does not appear in usual heavy metal urine and blood screens and as a result may not be asked for if not thought of in the differential diagnosis. Physicians dealing with instances of recurrent suspected HPP that do not fit usual age and clinical characteristics for HPP, lack the single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with the disease, and are not associated with other conditions causing severe hypokalemia, such as renal tubular acidosis, Bartter, Liddle or Gitelman syndrome or severe diuretic or licorice-induced hypokalemia should have soluble barium poisoning included in the differential diagnosis. Appropriately drawn blood specimens in special metal-free sampling tubes and hair barium levels should be included in the diagnostic workup. If poisoning is suspected, a chain of evidence should be obtained to protect possible future criminal investigation against compromise.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Tennessee 2nd District Attorney General Barry P. Staubus, 2nd District Assistant Attorney General Teresa A. Nelson, the VA Police Service, and the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation for their help.

1. Ahlawat SK, Sachdev A. Hypokalaemic paralysis. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75(882):193-197.

2. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet.2008;63:3-23.

3. Kayal AK, Goswami M, Das M, Jain R. Clinical and biochemical spectrum of hypokalemic paralysis in North: East India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol.2013;16(2):211-217.

4. Johnson CH, VanTassell VJ. Acute barium poisoning with respiratory failure and rhabdomyolysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(10):1138-1142.

5. Gold R, Reichmann H. Muscle pathology correlates with permanent weakness in hypokalemic periodic paralysis: a case report. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;84(2):202-206.

6. Links TP, Zwarts MJ, Wilmink JT, Molenaar WM, Oosterhuis HJ. Permanent muscle weakness in familial hypokalaemic periodic paralysis. Clinical, radiological and pathological aspects. Brain. 1990;113(pt 6):1873-1889.

7. Tucker C, Villanueva L. Acute hypokalemic periodic paralysis possibly precipitated by albuterol. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(18):1588-1591.

8. Liu PY, Jeng CY. Severe hypophosphatemia in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis and acute respiratory failure. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67(7):355-359.

9. Sigue G, Gamble L, Pelitere M, et al. From profound hypokalemia to life-threatening hyperkalemia: a case of barium sulfide poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):548-541.

10. Kuntzer T, Flocard F, Vial C, et al. Exercise test in muscle channelopathies and other muscle disorders. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(7):1089-1094.

11. Tengan CH, Antunes AC, Gabbai AA, Manzano GM. The exercise test as a monitor of disease status in hypokalaemic periodic paralysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):497-499.

12. McManis PG, Lambert EH, Daube JR. The exercise test in periodic paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9(8):704-710.

13. Huang K-W. Pa ping (transient paralysis simulating family periodic paralysis). Chin Med J. 1943;61(4):305-312.

14. Ng HY, Lin SH, Hsu CY, Tsai YZ, Chen HC, Lee CT. Hypokalemic paralysis due to Gitelman syndrome:a family study. Neurology. 2006;67(6):1080-1082.

15. Mohta M, Kalra B, Shukla R, Sethi AK. An unusual presentation of hypokalemia. J Anesth Clin Res. 2014;5(3):389.

16. Fujimoto T, Shiiki H, Takahi Y, Dohi K. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome presenting as hypokalaemic periodic paralysis and respiratory arrest. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20(5):365-368.

17. Chang YC, Huang CC, Chiou YY, Yu CY. Renal tubular acidosis complicated with hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13(1):52-54.

18. Lehmann-Horn F, Jurkat-Rott K, Rüdel R. Periodic paralysis: understanding channelopathies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2002;2(1):61-69.

19. Venance SL, Cannon SC, Fialho D, et al; CINCH investigators. The primary periodic paralyses: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Brain. 2006;129(pt 1):8-17.

20. Sharma C, Nath K, Parekh J. Reversible electrophysiological abnormalities in hypokalemic paralysis: case report of two cases. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17(1):100-102.

21. Sternberg D, Tabti N, Fournier E, Hainque B, Fontaine B. Lack of association of the potassium channel-associated peptide MiRP2-R83H variant with periodic paralysis. Neurology. 2003;61(6):857-859.

22. Ke Q, Luo B, Qi M, Du Y, Wu W. Gender differences in penetrance and phenotype in hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 2013;47(1):41-45.

23. Griggs RC, Engel WK, Resnick JS. Acetazolamide treatment of hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Prevention of attacks and improvement of persistent weakness. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73(1):39-48.

24. Dalakas MC, Engel WK. Treatment of “permanent” muscle weakness in familial hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 1983;6(3):182-186.

25. Ghose A, Sayeed AA, Hossain A, Rahman R, Faiz A, Haque G. Mass barium carbonate poisoning with fatal outcome, lessons learned: a case series. Cases J. 2009;2:9327.

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) is a relatively common and potentially life-threating condition that can be either sporadic or recurring and has both inherited and acquired causes.1 Familial HPP, on the other hand, is a rare condition (1:100,000) caused by loss of function mutations leading to the disruption of membrane potential consequently making them inexcitable.2 Appearance of symptoms is typically in the first or second decade of life (60% of cases have onset aged < 16 years) with susceptible individuals experiencing sudden onset of perioral numbness; weakness; centrifugal paralysis, often with nausea; vomiting and diarrhea; and prostration, usually triggered by highcarbohydrate meals and rest following sustained muscle-group use.3

These symptoms are common to all forms of HPP, making the differential diagnosis wide and confusing. Rhabdomyolysis is occasionally associated with many severe hypokalemic episodes.4 Myopathy and permanent muscle weakness have been reported in HPP.5,6 Other reported inciting factors include a drop in serum potassium caused by β-adrenergic bronchodilator treatment.7 Clinical attacks also have been associated with diabetic ketoacidosis and combined hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia.8 Thyrotoxicosis also causes similar muscle action potential changes but only when hyperthyroidism is uncorrected. 9-12 Less commonly, hypothyroidism has been reported to be associated with hypokalemic paralysis.3

Pa Ping, a condition involving hypokalemic paralysis of uncertain etiology, is geographically centered in the Szechuan region of China.13 Cases of Bartter, Liddle, and Gitelman syndromes also have been associated with hypokalemic paralysis.3,14 There is an association with malignant hyperthermia following or during systemic anesthesia. Patients presenting as Guillain-Barré syndrome have been found to have periodic paralysis triggered by hypokalemia from any cause.15 Sjögren syndrome and renal tubular acidosis also are reported to have triggered symptoms of hypokalemic paralysis.16,17

True type 1 HPP is caused by channelopathies resulting from mutations in the calcium channel gene CACN1AS (HypoPP1), which accounts for 70% of the cases, whereas type 2 HPP is cause by sodium channel gene SCN4A (HypoPP2) mutations, which accounts for 10% to 20% of cases.18,19 An association with a voltage-gated potassium channel KCNE3 mutation has been made but is disputed.20,21 Females typically have less severe and less frequent attacks, and attacks lessen or disappear during pregnancy.22

In a small controlled trial, acetazolamide has been reported to have prophylactic benefit, although a more powerful carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, dichlorophenamide, was reported to be effective in a study after acetazolamide had become ineffective.23,24 These treatments would not be expected to be of clinical use in hypokalemia due to barium poisoning.

Barium poisoning has been reported as a result of accidental contamination of foodstuffs with soluble barium.25 Onset of symptoms is rapid, with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and malaise followed rapidly by weakness, which can include the muscles of respiration. This littleconsidered but rapidly lethal poisoning event can be accidental as a result of environmental exposure due to unintentional ingestion of the toxin or deliberate criminal poisoning as in this case. Because deliberate poisoning rarely crosses the mind of the clinician, awareness of the potential similarity of barium poisoning to other forms of HPP and even familial HPP is important.

Case Presentation

A male veteran aged 45 years when treated by the authors was well until moving into a new rural home when he began to experience acute episodes of variable perioral numbness, diarrhea, paresthesias, abdominal cramping, and weakness, which ranged from mild, self-terminating extremity weakness to 3 episodes of respiratory failure that required intubation and mechanical ventilation.

All episodes were accompanied by hypokalemia in the range of 2 to 3 mEq/L, but levels varied erratically during admissions from severe hypokalemia to normo- and hyperkalemia. Over 3 years, the patient was admitted to the hospital 19 times, underwent extensive workup, and was referred to endocrinology services at Duke University, Vanderbilt University, and the Cleveland Clinic. Diagnostic efforts centered on establishing whether he had a latepresenting variant of familial HPP.

Genetic evaluations could not identify known single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with that condition. The consensus was that he had a potassium leak somewhere between his kidneys and bladder. Recommended management was a high baseline oral potassium supplementation and spironolactone. He had a brief period of improvement after moving to a different house, but the episodes returned once he moved back to his old house despite adherence to recommended treatment. In December 2012, he experienced his worst episode, with potassium 1.8 mEq/L on admission, resulting in admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).