User login

From the Vascular Community

SAAVS meeting a success

The Sixth Annual meeting of the South Asian American Vascular Society (SAVVS), an affiliate of the Society for Vascular Surgery, was held on May 31 during the Vascular Annual Meeting.

The Society was formed to provide a forum for scientific, clinical, cultural, charitable and social interaction among American physicians and healthcare providers of South Asian origin involved in the management of vascular disease. SAAVS also works as a forum to collaborate with Vascular Societies across South Asia .

Member benefits include being able to support vascular surgery in our countries of origin; sharing business knowledge and experience with members related to vendors, office practices, and opening centers for access/veins; mentoring of younger surgeons and medical students; assisting with new techniques and endovascular training; guiding job placement, contracts, and privileging issues; networking with friends and colleagues all over the world; taking a greater role in national societies; and taking advantage of the network for assistance in locating/obtaining training positions for family members.

The first annual meeting of the SAAVS was held in 2010. Past Presidents have included Drs. Krishna Jain, Bhagwan Satiani, Brajesh Lal, Anil Hingorani, Dipankar Mukherjee, and Ravi Veeraswamy. During VAM 2017, the current president, Faisal Aziz, MD, of Penn State gave his annual report and the society then inducted its future president Raghu Motaganahalli, MD, from Indiana University into office. Dr. Motaganahalli was also recently appointed as Director of the Division of Vascular Surgery at Indiana University. Peter Lawrence, MD, provided a keynote address highlighting opportunities for conducting research to improve patient care.

Other officers for 2017-2018 include President Elect Sachinder Hans, MD; Secretary Raj Sarkar, MD; Treasurer Krish Soundararajan, MD; Membership Committee: Kapil Gopal, MD, and Syed Alam, MD; Bylaws: Bhagwan Satiani, MD; Industry Relations: Krishna Jain, MD.

A regular feature of the meeting is an abstract/presentation contest for medical students and fellows interested in Vascular Surgery. First place winners from each category are offered cash prizes. In the future, SAAVS plans to have traveling fellowship programs for physicians from South Asia, as well as the United States, for collaborative clinical and educational exchange. Two members have already visited India and Pakistan for collaboration and assistance with endovascular procedures.

The website is www.saavsociety.org

Bhagwan Satiani, MD, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus.

Study established for “precision” surveillance for PAD

During the Vascular Annual Meeting (VAM) in San Diego, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced its decision to reimburse supervised exercise therapy (SET) for beneficiaries with PAD. This decision was based on evidence which concluded that SET improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with intermittent claudication due to PAD. Up to this point physician-prescribed supervised exercise therapy was only covered exclusively for Cardiac Rehabilitation.

SET for PAD covers up to 36 sessions over a 12 week period if sessions 1) last 30-60 minutes; 2) are conducted in a hospital outpatient setting or physician’s office; and 3) are delivered by qualified auxiliary personnel to ensure benefits exceed harm and if 4) beneficiaries are under the direct supervision of a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner/clinical nurse specialist who must be trained in both basic and advanced life support techniques. Face-to-face visits with the physician responsible for PAD treatment is required for a SET referral. At this visit, the beneficiary must receive information regarding CV and PAD risk factor reduction, which could include education, counseling, behavior interventions and outcome assessments.

The widespread implementation of SET programs will require the adoption of a functional outcome assessment for PAD.

Here at the Division of Vascular Surgery at Stanford University, we are evaluating the use of a patient’s own smartphone to track and monitor walking activity. The research study called, VascTrac, was developed to provide a more “personalized” approach to surveillance for patients with intermittent claudication in line with precision medicine. We hypothesize that there is a direct correlation between a patient’s walking ability (functional status) and their disease burden.

Vascular surgeons today are finding themselves faced with an increasingly common problem: the “returning patient.” All too often, patients with peripheral artery disease are returning to clinic just months after treatment, frustrated by resurfacing symptoms. What was seemingly a straightforward femoral artery occlusion with an easy stent fix has somehow degraded into disabling claudication (Rutherford Class II/III) in a very short period of time. A staggering number of these patients have perfect-appearing completion angiograms, yet they return to clinic with complete re-occlusions. The tale of mild symptom return, typically beginning several months prior to the current visit, is becoming unsettlingly familiar. Inevitably, the story raises the question: “Why didn’t you come in sooner?”

This frustrating scenario calls for a new paradigm for surveillance of PAD – a more personalized approach in line with precision medicine.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of smartphones and other personal mobile devices has increased at a blistering pace. Today, over 700 million iPhones alone exist worldwide. These devices have an enormous potential to revolutionize the way we deliver care.

In 2014, Apple launched a secure personal mobile health repository called HealthKit, which now comes pre-loaded on every iPhone that is sold. This repository stores data ranging from step counts to blood glucose levels in a secure and structured way. As a bonus, every phone contains accelerometers which passively track a user’s daily activity. On the heels of HealthKit came the Apple ResearchKit framework, launched in 2015 as a means to standardize study enrollment, data collection, storage and transmission on the iPhone. The advent of this new study tool opened the door for remote patient monitoring and “siteless” clinical trials at scale.

These two new platforms have significant implications for health monitoring and diagnosis. While activity is the functional outcome that physicians aim to improve for disabling claudicants, the field currently lacks a means of objectively measuring patient activity and functional outcomes.

Traditional PAD monitoring focuses primarily on vessel patency and ankle brachial indices (ABIs) at 1-, 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals. The problem is that stents don’t fail at 1-, 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals, but ultrasounds and ABI’s require technicians and it’s challenging to perform those more often. There are too many gaps in knowledge, too many black holes, and a more granular approach is required. [NB: Seems to me just adding a 1 month reading would have solved the problem. The rest of the data points are perfect representations of the trend for which VascTrac provides no added benefit. The graph is not needed and would add even more “advertising flair.”

Using activity data as a surrogate for traditional measures of ABIs and vessel patency, we have designed algorithms to passively monitor patients’ daily activity using their personal smartphones. We have implemented these algorithms into an app and have now launched the VascTrac PAD Research Study.

VascTrac is an app available for download from the Apple App Store. Participants need an iPhone 5s (released in 2013) or a newer model. Enrollment, including consent, is all done on the phone. There are three short surveys focused on medical history, surgical history and PAD-specific history (including ABIs). Every two weeks, the app asks patients to perform a 6-minute walk test, and every quarter they are asked to complete the medical, surgical and PAD surveys. However, the majority of activity data is collected passively. Specifically, the app collects total steps per day, distance walked per day, and flights climbed per day and uses an algorithm developed by the team to gather data on a new unique metric, “Max Steps Without Stopping” (MSWS).

A motivated patient can walk 5 miles a day, but he or she may have to stop multiple times along the way. We believe MSWS will help catch the stopping due to the claudication. Patients are provided with a dashboard of their average activity for the week, month and year. They are also provided with links to PAD educational resources.

The VascTrac study is open to all, even non-PAD participants. The inclusion criteria are that a participant must be at least 18 years of age, live in the United States, speak English and have an iPhone 5s or newer model. The ideal patient, however, would be someone who is scheduled for an intervention. This way, the team can obtain a few weeks of baseline activity before evaluating the intervention’s effect on the patient’s functional activity.

Some of the questions our team hopes to answer are, What are the actual effects of our interventions (open vs. bypass) on a patient’s functional capacity? How stable are our interventions relative to a patient’s functional activity? What are the failure modes – is there a gradual decline in activity before failure or an abrupt decline? Can we predict failure of an intervention by doing a regression analysis of a patient’s functional activity trends?

We welcome the participation of any interested providers. More information can be found at www.vasctrac.stanford.edu, where providers can also request recruitment materials. Alternatively, the team can be contacted directly at contact@vasctrac.com.

This is an IRB-approved study and neither the researchers nor the university have any financial disclosures.

Oliver Aalami, MD, Stanford University School of Medicine/Palo Alto.

SAAVS meeting a success

The Sixth Annual meeting of the South Asian American Vascular Society (SAVVS), an affiliate of the Society for Vascular Surgery, was held on May 31 during the Vascular Annual Meeting.

The Society was formed to provide a forum for scientific, clinical, cultural, charitable and social interaction among American physicians and healthcare providers of South Asian origin involved in the management of vascular disease. SAAVS also works as a forum to collaborate with Vascular Societies across South Asia .

Member benefits include being able to support vascular surgery in our countries of origin; sharing business knowledge and experience with members related to vendors, office practices, and opening centers for access/veins; mentoring of younger surgeons and medical students; assisting with new techniques and endovascular training; guiding job placement, contracts, and privileging issues; networking with friends and colleagues all over the world; taking a greater role in national societies; and taking advantage of the network for assistance in locating/obtaining training positions for family members.

The first annual meeting of the SAAVS was held in 2010. Past Presidents have included Drs. Krishna Jain, Bhagwan Satiani, Brajesh Lal, Anil Hingorani, Dipankar Mukherjee, and Ravi Veeraswamy. During VAM 2017, the current president, Faisal Aziz, MD, of Penn State gave his annual report and the society then inducted its future president Raghu Motaganahalli, MD, from Indiana University into office. Dr. Motaganahalli was also recently appointed as Director of the Division of Vascular Surgery at Indiana University. Peter Lawrence, MD, provided a keynote address highlighting opportunities for conducting research to improve patient care.

Other officers for 2017-2018 include President Elect Sachinder Hans, MD; Secretary Raj Sarkar, MD; Treasurer Krish Soundararajan, MD; Membership Committee: Kapil Gopal, MD, and Syed Alam, MD; Bylaws: Bhagwan Satiani, MD; Industry Relations: Krishna Jain, MD.

A regular feature of the meeting is an abstract/presentation contest for medical students and fellows interested in Vascular Surgery. First place winners from each category are offered cash prizes. In the future, SAAVS plans to have traveling fellowship programs for physicians from South Asia, as well as the United States, for collaborative clinical and educational exchange. Two members have already visited India and Pakistan for collaboration and assistance with endovascular procedures.

The website is www.saavsociety.org

Bhagwan Satiani, MD, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus.

Study established for “precision” surveillance for PAD

During the Vascular Annual Meeting (VAM) in San Diego, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced its decision to reimburse supervised exercise therapy (SET) for beneficiaries with PAD. This decision was based on evidence which concluded that SET improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with intermittent claudication due to PAD. Up to this point physician-prescribed supervised exercise therapy was only covered exclusively for Cardiac Rehabilitation.

SET for PAD covers up to 36 sessions over a 12 week period if sessions 1) last 30-60 minutes; 2) are conducted in a hospital outpatient setting or physician’s office; and 3) are delivered by qualified auxiliary personnel to ensure benefits exceed harm and if 4) beneficiaries are under the direct supervision of a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner/clinical nurse specialist who must be trained in both basic and advanced life support techniques. Face-to-face visits with the physician responsible for PAD treatment is required for a SET referral. At this visit, the beneficiary must receive information regarding CV and PAD risk factor reduction, which could include education, counseling, behavior interventions and outcome assessments.

The widespread implementation of SET programs will require the adoption of a functional outcome assessment for PAD.

Here at the Division of Vascular Surgery at Stanford University, we are evaluating the use of a patient’s own smartphone to track and monitor walking activity. The research study called, VascTrac, was developed to provide a more “personalized” approach to surveillance for patients with intermittent claudication in line with precision medicine. We hypothesize that there is a direct correlation between a patient’s walking ability (functional status) and their disease burden.

Vascular surgeons today are finding themselves faced with an increasingly common problem: the “returning patient.” All too often, patients with peripheral artery disease are returning to clinic just months after treatment, frustrated by resurfacing symptoms. What was seemingly a straightforward femoral artery occlusion with an easy stent fix has somehow degraded into disabling claudication (Rutherford Class II/III) in a very short period of time. A staggering number of these patients have perfect-appearing completion angiograms, yet they return to clinic with complete re-occlusions. The tale of mild symptom return, typically beginning several months prior to the current visit, is becoming unsettlingly familiar. Inevitably, the story raises the question: “Why didn’t you come in sooner?”

This frustrating scenario calls for a new paradigm for surveillance of PAD – a more personalized approach in line with precision medicine.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of smartphones and other personal mobile devices has increased at a blistering pace. Today, over 700 million iPhones alone exist worldwide. These devices have an enormous potential to revolutionize the way we deliver care.

In 2014, Apple launched a secure personal mobile health repository called HealthKit, which now comes pre-loaded on every iPhone that is sold. This repository stores data ranging from step counts to blood glucose levels in a secure and structured way. As a bonus, every phone contains accelerometers which passively track a user’s daily activity. On the heels of HealthKit came the Apple ResearchKit framework, launched in 2015 as a means to standardize study enrollment, data collection, storage and transmission on the iPhone. The advent of this new study tool opened the door for remote patient monitoring and “siteless” clinical trials at scale.

These two new platforms have significant implications for health monitoring and diagnosis. While activity is the functional outcome that physicians aim to improve for disabling claudicants, the field currently lacks a means of objectively measuring patient activity and functional outcomes.

Traditional PAD monitoring focuses primarily on vessel patency and ankle brachial indices (ABIs) at 1-, 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals. The problem is that stents don’t fail at 1-, 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals, but ultrasounds and ABI’s require technicians and it’s challenging to perform those more often. There are too many gaps in knowledge, too many black holes, and a more granular approach is required. [NB: Seems to me just adding a 1 month reading would have solved the problem. The rest of the data points are perfect representations of the trend for which VascTrac provides no added benefit. The graph is not needed and would add even more “advertising flair.”

Using activity data as a surrogate for traditional measures of ABIs and vessel patency, we have designed algorithms to passively monitor patients’ daily activity using their personal smartphones. We have implemented these algorithms into an app and have now launched the VascTrac PAD Research Study.

VascTrac is an app available for download from the Apple App Store. Participants need an iPhone 5s (released in 2013) or a newer model. Enrollment, including consent, is all done on the phone. There are three short surveys focused on medical history, surgical history and PAD-specific history (including ABIs). Every two weeks, the app asks patients to perform a 6-minute walk test, and every quarter they are asked to complete the medical, surgical and PAD surveys. However, the majority of activity data is collected passively. Specifically, the app collects total steps per day, distance walked per day, and flights climbed per day and uses an algorithm developed by the team to gather data on a new unique metric, “Max Steps Without Stopping” (MSWS).

A motivated patient can walk 5 miles a day, but he or she may have to stop multiple times along the way. We believe MSWS will help catch the stopping due to the claudication. Patients are provided with a dashboard of their average activity for the week, month and year. They are also provided with links to PAD educational resources.

The VascTrac study is open to all, even non-PAD participants. The inclusion criteria are that a participant must be at least 18 years of age, live in the United States, speak English and have an iPhone 5s or newer model. The ideal patient, however, would be someone who is scheduled for an intervention. This way, the team can obtain a few weeks of baseline activity before evaluating the intervention’s effect on the patient’s functional activity.

Some of the questions our team hopes to answer are, What are the actual effects of our interventions (open vs. bypass) on a patient’s functional capacity? How stable are our interventions relative to a patient’s functional activity? What are the failure modes – is there a gradual decline in activity before failure or an abrupt decline? Can we predict failure of an intervention by doing a regression analysis of a patient’s functional activity trends?

We welcome the participation of any interested providers. More information can be found at www.vasctrac.stanford.edu, where providers can also request recruitment materials. Alternatively, the team can be contacted directly at contact@vasctrac.com.

This is an IRB-approved study and neither the researchers nor the university have any financial disclosures.

Oliver Aalami, MD, Stanford University School of Medicine/Palo Alto.

SAAVS meeting a success

The Sixth Annual meeting of the South Asian American Vascular Society (SAVVS), an affiliate of the Society for Vascular Surgery, was held on May 31 during the Vascular Annual Meeting.

The Society was formed to provide a forum for scientific, clinical, cultural, charitable and social interaction among American physicians and healthcare providers of South Asian origin involved in the management of vascular disease. SAAVS also works as a forum to collaborate with Vascular Societies across South Asia .

Member benefits include being able to support vascular surgery in our countries of origin; sharing business knowledge and experience with members related to vendors, office practices, and opening centers for access/veins; mentoring of younger surgeons and medical students; assisting with new techniques and endovascular training; guiding job placement, contracts, and privileging issues; networking with friends and colleagues all over the world; taking a greater role in national societies; and taking advantage of the network for assistance in locating/obtaining training positions for family members.

The first annual meeting of the SAAVS was held in 2010. Past Presidents have included Drs. Krishna Jain, Bhagwan Satiani, Brajesh Lal, Anil Hingorani, Dipankar Mukherjee, and Ravi Veeraswamy. During VAM 2017, the current president, Faisal Aziz, MD, of Penn State gave his annual report and the society then inducted its future president Raghu Motaganahalli, MD, from Indiana University into office. Dr. Motaganahalli was also recently appointed as Director of the Division of Vascular Surgery at Indiana University. Peter Lawrence, MD, provided a keynote address highlighting opportunities for conducting research to improve patient care.

Other officers for 2017-2018 include President Elect Sachinder Hans, MD; Secretary Raj Sarkar, MD; Treasurer Krish Soundararajan, MD; Membership Committee: Kapil Gopal, MD, and Syed Alam, MD; Bylaws: Bhagwan Satiani, MD; Industry Relations: Krishna Jain, MD.

A regular feature of the meeting is an abstract/presentation contest for medical students and fellows interested in Vascular Surgery. First place winners from each category are offered cash prizes. In the future, SAAVS plans to have traveling fellowship programs for physicians from South Asia, as well as the United States, for collaborative clinical and educational exchange. Two members have already visited India and Pakistan for collaboration and assistance with endovascular procedures.

The website is www.saavsociety.org

Bhagwan Satiani, MD, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus.

Study established for “precision” surveillance for PAD

During the Vascular Annual Meeting (VAM) in San Diego, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced its decision to reimburse supervised exercise therapy (SET) for beneficiaries with PAD. This decision was based on evidence which concluded that SET improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with intermittent claudication due to PAD. Up to this point physician-prescribed supervised exercise therapy was only covered exclusively for Cardiac Rehabilitation.

SET for PAD covers up to 36 sessions over a 12 week period if sessions 1) last 30-60 minutes; 2) are conducted in a hospital outpatient setting or physician’s office; and 3) are delivered by qualified auxiliary personnel to ensure benefits exceed harm and if 4) beneficiaries are under the direct supervision of a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner/clinical nurse specialist who must be trained in both basic and advanced life support techniques. Face-to-face visits with the physician responsible for PAD treatment is required for a SET referral. At this visit, the beneficiary must receive information regarding CV and PAD risk factor reduction, which could include education, counseling, behavior interventions and outcome assessments.

The widespread implementation of SET programs will require the adoption of a functional outcome assessment for PAD.

Here at the Division of Vascular Surgery at Stanford University, we are evaluating the use of a patient’s own smartphone to track and monitor walking activity. The research study called, VascTrac, was developed to provide a more “personalized” approach to surveillance for patients with intermittent claudication in line with precision medicine. We hypothesize that there is a direct correlation between a patient’s walking ability (functional status) and their disease burden.

Vascular surgeons today are finding themselves faced with an increasingly common problem: the “returning patient.” All too often, patients with peripheral artery disease are returning to clinic just months after treatment, frustrated by resurfacing symptoms. What was seemingly a straightforward femoral artery occlusion with an easy stent fix has somehow degraded into disabling claudication (Rutherford Class II/III) in a very short period of time. A staggering number of these patients have perfect-appearing completion angiograms, yet they return to clinic with complete re-occlusions. The tale of mild symptom return, typically beginning several months prior to the current visit, is becoming unsettlingly familiar. Inevitably, the story raises the question: “Why didn’t you come in sooner?”

This frustrating scenario calls for a new paradigm for surveillance of PAD – a more personalized approach in line with precision medicine.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of smartphones and other personal mobile devices has increased at a blistering pace. Today, over 700 million iPhones alone exist worldwide. These devices have an enormous potential to revolutionize the way we deliver care.

In 2014, Apple launched a secure personal mobile health repository called HealthKit, which now comes pre-loaded on every iPhone that is sold. This repository stores data ranging from step counts to blood glucose levels in a secure and structured way. As a bonus, every phone contains accelerometers which passively track a user’s daily activity. On the heels of HealthKit came the Apple ResearchKit framework, launched in 2015 as a means to standardize study enrollment, data collection, storage and transmission on the iPhone. The advent of this new study tool opened the door for remote patient monitoring and “siteless” clinical trials at scale.

These two new platforms have significant implications for health monitoring and diagnosis. While activity is the functional outcome that physicians aim to improve for disabling claudicants, the field currently lacks a means of objectively measuring patient activity and functional outcomes.

Traditional PAD monitoring focuses primarily on vessel patency and ankle brachial indices (ABIs) at 1-, 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals. The problem is that stents don’t fail at 1-, 3-, 6- and 12-month intervals, but ultrasounds and ABI’s require technicians and it’s challenging to perform those more often. There are too many gaps in knowledge, too many black holes, and a more granular approach is required. [NB: Seems to me just adding a 1 month reading would have solved the problem. The rest of the data points are perfect representations of the trend for which VascTrac provides no added benefit. The graph is not needed and would add even more “advertising flair.”

Using activity data as a surrogate for traditional measures of ABIs and vessel patency, we have designed algorithms to passively monitor patients’ daily activity using their personal smartphones. We have implemented these algorithms into an app and have now launched the VascTrac PAD Research Study.

VascTrac is an app available for download from the Apple App Store. Participants need an iPhone 5s (released in 2013) or a newer model. Enrollment, including consent, is all done on the phone. There are three short surveys focused on medical history, surgical history and PAD-specific history (including ABIs). Every two weeks, the app asks patients to perform a 6-minute walk test, and every quarter they are asked to complete the medical, surgical and PAD surveys. However, the majority of activity data is collected passively. Specifically, the app collects total steps per day, distance walked per day, and flights climbed per day and uses an algorithm developed by the team to gather data on a new unique metric, “Max Steps Without Stopping” (MSWS).

A motivated patient can walk 5 miles a day, but he or she may have to stop multiple times along the way. We believe MSWS will help catch the stopping due to the claudication. Patients are provided with a dashboard of their average activity for the week, month and year. They are also provided with links to PAD educational resources.

The VascTrac study is open to all, even non-PAD participants. The inclusion criteria are that a participant must be at least 18 years of age, live in the United States, speak English and have an iPhone 5s or newer model. The ideal patient, however, would be someone who is scheduled for an intervention. This way, the team can obtain a few weeks of baseline activity before evaluating the intervention’s effect on the patient’s functional activity.

Some of the questions our team hopes to answer are, What are the actual effects of our interventions (open vs. bypass) on a patient’s functional capacity? How stable are our interventions relative to a patient’s functional activity? What are the failure modes – is there a gradual decline in activity before failure or an abrupt decline? Can we predict failure of an intervention by doing a regression analysis of a patient’s functional activity trends?

We welcome the participation of any interested providers. More information can be found at www.vasctrac.stanford.edu, where providers can also request recruitment materials. Alternatively, the team can be contacted directly at contact@vasctrac.com.

This is an IRB-approved study and neither the researchers nor the university have any financial disclosures.

Oliver Aalami, MD, Stanford University School of Medicine/Palo Alto.

Concomitant MIMV-TVS no worse than MIMV alone

NEW YORK – Concurrent mitral-tricuspid valve surgery has similar outcomes to isolated minimally invasive mitral valve surgery, according to results of a 12-year review reported at the 2017 Mitral Valve Conclave, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Indications for minimally invasive tricuspid valve surgery done at the same time of mitral valve surgery have not been well established, in part because the outcomes of such combined procedures have been underreported.

Dr. Kilic noted that patients who had concomitant TVS were typically higher risk at baseline. “The concomitant group was older, had a higher percentage of female patients, and higher rates of chronic lung disease and cerebrovascular disease as well,” Dr. Kilic said. In comparing the isolated MIMV surgery and MIMV-TVS groups in the unmatched analysis, 9% vs. 14% had chronic lung disease (P = .05), 12% vs. 16% had coronary artery disease (P = .15), 7% vs. 12% had cerebrovascular disease (P = .04), and 93% vs. 90% had elective surgery (P = .18). The majority of tricuspid repairs were for severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) or moderate TR with a dilated annulus of 40 mm or greater.

The operative characteristics differed significantly between the two groups. “As one might expect, the cardiopulmonary bypass time and aortic occlusion times were longer in the concomitant group; and balloon aortic occlusion was used in more than 70% in each cohort,” Dr. Kilic said. Those differences were similar in the propensity-matched cohort: bypass times were 147.5 minutes for isolated MIMV surgery and 174.6 minutes for MIMV-TVS (P less than .001); and aortic occlusion time 104.8 vs. 128 minutes (P less than .001), respectively.

Operative mortality was 3% for isolated MIMV surgery and 4% for concurrent MIMV-TVS (P = .73), but the isolated MIMV surgery group required fewer permanent pacemakers, 1% vs. 6% (P = .03).

“Aside from permanent pacemaker implantation, the rates of every other complication were similar, including stoke, limb ischemia, atrial fibrillation, gastrointestinal complications, respiratory complications, blood product transfusions as well as discharge to home rates,” Dr. Kilic said. Median hospital length of stays were also similar: 7 days for isolated MIMV surgery vs. 8 days for MIMV-TVS (P = .13).

One limitation of the study Dr. Kilic pointed out was that the decision to perform concomitant MIMV-TVS was surgeon dependent.

Dr. Kilic reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Concurrent mitral-tricuspid valve surgery has similar outcomes to isolated minimally invasive mitral valve surgery, according to results of a 12-year review reported at the 2017 Mitral Valve Conclave, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Indications for minimally invasive tricuspid valve surgery done at the same time of mitral valve surgery have not been well established, in part because the outcomes of such combined procedures have been underreported.

Dr. Kilic noted that patients who had concomitant TVS were typically higher risk at baseline. “The concomitant group was older, had a higher percentage of female patients, and higher rates of chronic lung disease and cerebrovascular disease as well,” Dr. Kilic said. In comparing the isolated MIMV surgery and MIMV-TVS groups in the unmatched analysis, 9% vs. 14% had chronic lung disease (P = .05), 12% vs. 16% had coronary artery disease (P = .15), 7% vs. 12% had cerebrovascular disease (P = .04), and 93% vs. 90% had elective surgery (P = .18). The majority of tricuspid repairs were for severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) or moderate TR with a dilated annulus of 40 mm or greater.

The operative characteristics differed significantly between the two groups. “As one might expect, the cardiopulmonary bypass time and aortic occlusion times were longer in the concomitant group; and balloon aortic occlusion was used in more than 70% in each cohort,” Dr. Kilic said. Those differences were similar in the propensity-matched cohort: bypass times were 147.5 minutes for isolated MIMV surgery and 174.6 minutes for MIMV-TVS (P less than .001); and aortic occlusion time 104.8 vs. 128 minutes (P less than .001), respectively.

Operative mortality was 3% for isolated MIMV surgery and 4% for concurrent MIMV-TVS (P = .73), but the isolated MIMV surgery group required fewer permanent pacemakers, 1% vs. 6% (P = .03).

“Aside from permanent pacemaker implantation, the rates of every other complication were similar, including stoke, limb ischemia, atrial fibrillation, gastrointestinal complications, respiratory complications, blood product transfusions as well as discharge to home rates,” Dr. Kilic said. Median hospital length of stays were also similar: 7 days for isolated MIMV surgery vs. 8 days for MIMV-TVS (P = .13).

One limitation of the study Dr. Kilic pointed out was that the decision to perform concomitant MIMV-TVS was surgeon dependent.

Dr. Kilic reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Concurrent mitral-tricuspid valve surgery has similar outcomes to isolated minimally invasive mitral valve surgery, according to results of a 12-year review reported at the 2017 Mitral Valve Conclave, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Indications for minimally invasive tricuspid valve surgery done at the same time of mitral valve surgery have not been well established, in part because the outcomes of such combined procedures have been underreported.

Dr. Kilic noted that patients who had concomitant TVS were typically higher risk at baseline. “The concomitant group was older, had a higher percentage of female patients, and higher rates of chronic lung disease and cerebrovascular disease as well,” Dr. Kilic said. In comparing the isolated MIMV surgery and MIMV-TVS groups in the unmatched analysis, 9% vs. 14% had chronic lung disease (P = .05), 12% vs. 16% had coronary artery disease (P = .15), 7% vs. 12% had cerebrovascular disease (P = .04), and 93% vs. 90% had elective surgery (P = .18). The majority of tricuspid repairs were for severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) or moderate TR with a dilated annulus of 40 mm or greater.

The operative characteristics differed significantly between the two groups. “As one might expect, the cardiopulmonary bypass time and aortic occlusion times were longer in the concomitant group; and balloon aortic occlusion was used in more than 70% in each cohort,” Dr. Kilic said. Those differences were similar in the propensity-matched cohort: bypass times were 147.5 minutes for isolated MIMV surgery and 174.6 minutes for MIMV-TVS (P less than .001); and aortic occlusion time 104.8 vs. 128 minutes (P less than .001), respectively.

Operative mortality was 3% for isolated MIMV surgery and 4% for concurrent MIMV-TVS (P = .73), but the isolated MIMV surgery group required fewer permanent pacemakers, 1% vs. 6% (P = .03).

“Aside from permanent pacemaker implantation, the rates of every other complication were similar, including stoke, limb ischemia, atrial fibrillation, gastrointestinal complications, respiratory complications, blood product transfusions as well as discharge to home rates,” Dr. Kilic said. Median hospital length of stays were also similar: 7 days for isolated MIMV surgery vs. 8 days for MIMV-TVS (P = .13).

One limitation of the study Dr. Kilic pointed out was that the decision to perform concomitant MIMV-TVS was surgeon dependent.

Dr. Kilic reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE 2017 MITRAL VALVE CONCLAVE

Key clinical point: Outcomes of isolated minimally invasive mitral valve surgery (MIMV) and MIMV with concomitant tricuspid valve surgery (TVS) are similar.

Major finding: Operative mortality was 3% for isolated MIMV and 4% for concurrent MIMV-TVS.

Data source: Single-center review of 1,158 patients who underwent either isolated MIMV or MIMV-TVS from 2002 to 2014, including a propensity-matched cohort.

Disclosures: Dr. Kilic reported having no financial disclosures.

Small study: Patients prefer microneedle flu vaccine

Influenza vaccinations given through a microneedle patch (MNP) received higher patient approval compared with traditional inoculation methods, according to a small study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

In a phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 100 patients between the ages of 18 and 49 years were split into four groups: one given the patch by a health care worker, one instructed to apply the patch at home, one given a vaccine through a traditional intramuscular injection, and one given a placebo.

Of those who took the patch, 70% (33 of 47) preferred the patch to intramuscular injection (The Lancet. 2017 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30575-5).

All nonplacebo groups were given Fluvirin, the 2014-2015 licensed trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, according to the researchers.

Protection against the virus 6 months after vaccination was similar across all groups other than the placebo group: 20-24 (83%-100%) of 24 participants given the patch by a health care worker, 18-24 (75%-100%) of 24 in the group of patients who gave themselves the patch, and 20-25 (80%-100%) of 25 in the injection group having achieved seroprotection against the three influenza strains 6 months after vaccination.

When measuring reactogenicity, the investigators did find more patients (41 of 50) reported cases of pruritis in the microneedle group than in the injection group (4 of 25).

However, these cases were mostly mild, while the injection group reported more grade 2 and grade 3 reactions, with grade 4 being the most severe.

Given the storage temperature of 40° C and ease of use without a health care provider, the investigators discussed the financial and clinical prospects of the patch.

“Increased acceptability could enable increased rates of influenza vaccination, which are currently less than 50% in adult populations,” they noted. “Moreover, because participants were able to self-vaccinate and 70% or more preferred it, significant cost savings could be enabled by microneedle patches due to a reduction in health-care worker time devoted to vaccination.”

Along with storage life and simple application process, the fact that the microneedles dissolve safely into the skin creates the potential for use in patients’ homes and offices, the researchers noted.

There may also be potential for use among pediatric patients, who may be resistant to vaccinations because of the injection method, they added.

“Microneedle patches have the potential to become ideal candidates for vaccination programmes, not only in poorly resourced settings, but also for individuals who currently prefer not to get vaccinated, potentially even being an attractive vaccine for the paediatric population,” Katja Höschler, PhD, and Maria C. Zambon, PhD, of Public Health England, London, said in a comment published with the study (The Lancet. 2017 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]31364-8). “The delivery advantages could also be exploited for non-influenza vaccines.”

Further studies must be conducted to test the efficacy of this vaccination system, because this study was limited by its size, the researchers noted.

The population was less inclined to receive an influenza injection because of the method itself, which may have affected the levels of preference for the patch, they added.

Some of the researchers are employees of Micron Biomedical, a company that manufactures microneedle products, and are listed as inventors on the licensed patents of these products. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter@eaztweets

Influenza vaccinations given through a microneedle patch (MNP) received higher patient approval compared with traditional inoculation methods, according to a small study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

In a phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 100 patients between the ages of 18 and 49 years were split into four groups: one given the patch by a health care worker, one instructed to apply the patch at home, one given a vaccine through a traditional intramuscular injection, and one given a placebo.

Of those who took the patch, 70% (33 of 47) preferred the patch to intramuscular injection (The Lancet. 2017 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30575-5).

All nonplacebo groups were given Fluvirin, the 2014-2015 licensed trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, according to the researchers.

Protection against the virus 6 months after vaccination was similar across all groups other than the placebo group: 20-24 (83%-100%) of 24 participants given the patch by a health care worker, 18-24 (75%-100%) of 24 in the group of patients who gave themselves the patch, and 20-25 (80%-100%) of 25 in the injection group having achieved seroprotection against the three influenza strains 6 months after vaccination.

When measuring reactogenicity, the investigators did find more patients (41 of 50) reported cases of pruritis in the microneedle group than in the injection group (4 of 25).

However, these cases were mostly mild, while the injection group reported more grade 2 and grade 3 reactions, with grade 4 being the most severe.

Given the storage temperature of 40° C and ease of use without a health care provider, the investigators discussed the financial and clinical prospects of the patch.

“Increased acceptability could enable increased rates of influenza vaccination, which are currently less than 50% in adult populations,” they noted. “Moreover, because participants were able to self-vaccinate and 70% or more preferred it, significant cost savings could be enabled by microneedle patches due to a reduction in health-care worker time devoted to vaccination.”

Along with storage life and simple application process, the fact that the microneedles dissolve safely into the skin creates the potential for use in patients’ homes and offices, the researchers noted.

There may also be potential for use among pediatric patients, who may be resistant to vaccinations because of the injection method, they added.

“Microneedle patches have the potential to become ideal candidates for vaccination programmes, not only in poorly resourced settings, but also for individuals who currently prefer not to get vaccinated, potentially even being an attractive vaccine for the paediatric population,” Katja Höschler, PhD, and Maria C. Zambon, PhD, of Public Health England, London, said in a comment published with the study (The Lancet. 2017 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]31364-8). “The delivery advantages could also be exploited for non-influenza vaccines.”

Further studies must be conducted to test the efficacy of this vaccination system, because this study was limited by its size, the researchers noted.

The population was less inclined to receive an influenza injection because of the method itself, which may have affected the levels of preference for the patch, they added.

Some of the researchers are employees of Micron Biomedical, a company that manufactures microneedle products, and are listed as inventors on the licensed patents of these products. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter@eaztweets

Influenza vaccinations given through a microneedle patch (MNP) received higher patient approval compared with traditional inoculation methods, according to a small study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

In a phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 100 patients between the ages of 18 and 49 years were split into four groups: one given the patch by a health care worker, one instructed to apply the patch at home, one given a vaccine through a traditional intramuscular injection, and one given a placebo.

Of those who took the patch, 70% (33 of 47) preferred the patch to intramuscular injection (The Lancet. 2017 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]30575-5).

All nonplacebo groups were given Fluvirin, the 2014-2015 licensed trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, according to the researchers.

Protection against the virus 6 months after vaccination was similar across all groups other than the placebo group: 20-24 (83%-100%) of 24 participants given the patch by a health care worker, 18-24 (75%-100%) of 24 in the group of patients who gave themselves the patch, and 20-25 (80%-100%) of 25 in the injection group having achieved seroprotection against the three influenza strains 6 months after vaccination.

When measuring reactogenicity, the investigators did find more patients (41 of 50) reported cases of pruritis in the microneedle group than in the injection group (4 of 25).

However, these cases were mostly mild, while the injection group reported more grade 2 and grade 3 reactions, with grade 4 being the most severe.

Given the storage temperature of 40° C and ease of use without a health care provider, the investigators discussed the financial and clinical prospects of the patch.

“Increased acceptability could enable increased rates of influenza vaccination, which are currently less than 50% in adult populations,” they noted. “Moreover, because participants were able to self-vaccinate and 70% or more preferred it, significant cost savings could be enabled by microneedle patches due to a reduction in health-care worker time devoted to vaccination.”

Along with storage life and simple application process, the fact that the microneedles dissolve safely into the skin creates the potential for use in patients’ homes and offices, the researchers noted.

There may also be potential for use among pediatric patients, who may be resistant to vaccinations because of the injection method, they added.

“Microneedle patches have the potential to become ideal candidates for vaccination programmes, not only in poorly resourced settings, but also for individuals who currently prefer not to get vaccinated, potentially even being an attractive vaccine for the paediatric population,” Katja Höschler, PhD, and Maria C. Zambon, PhD, of Public Health England, London, said in a comment published with the study (The Lancet. 2017 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]31364-8). “The delivery advantages could also be exploited for non-influenza vaccines.”

Further studies must be conducted to test the efficacy of this vaccination system, because this study was limited by its size, the researchers noted.

The population was less inclined to receive an influenza injection because of the method itself, which may have affected the levels of preference for the patch, they added.

Some of the researchers are employees of Micron Biomedical, a company that manufactures microneedle products, and are listed as inventors on the licensed patents of these products. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter@eaztweets

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Twenty-eight days after vaccination, 33 of 47 of patients (70%) who received the microneedle patch vaccine preferred that method to traditional inoculation.

Data source: A phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled study of 100 patients between the ages of 18 and 49 years.

Disclosures: Three of the researchers are employees of Micron Biomedical, a company that manufactures microneedle products, and are listed as inventors on the licensed patents of these products. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

What stops physicians from getting mental health care?

Physician burnout is rampant, and every seat was taken at a workshop on physician burnout and depression at this year’s APA annual meeting in San Diego.

In his book, “Why Physicians Die By Suicide” (Amazon, 2017), Michael F. Myers, MD, describes “burnout.”

Myers notes that there is no stigma to having burnout, as there is to having major depression – a condition that may have remarkably similar symptoms.

What stops physicians from getting help? It’s a complex question – especially in a group that has the means to access medical services – but one factor is that most state licensing boards specifically ask about mental illnesses and substance abuse in intrusive and stigmatizing ways. States vary both with their questions and with their responses to a box checked “yes.”

Katherine Gold, MD, MSW, MS, a family physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has studied the topic extensively. Her review of licensing questions from all 50 states revealed that most states ask for information about mental health, and there is tremendous variation as to what is asked (Fam Med. 2017 Jun;49[6]:464-7).

“Some states are very specific and very intrusive,” Gold noted. “They may ask if a physician has a specific diagnosis, a history of treatment or hospitalization. The questions may ask about current impairment, or they may ask about mental health conditions back to age 18 years. There may be very specific questions about diagnosis that are not asked about medical conditions, such as whether the applicant has kleptomania, pyromania, or seasonal affective disorder.”

Gold conducted an online survey of physician-mothers. Nearly half believed they had met criteria for an episode of mental illness at some point during their lives. Of those who did have a diagnosis, only 6% of physicians reported this on licensing forms, though she was quick to say that not all states ask for this information, and some may just ask about current impairment. “The people who are self-disclosing are probably not the physicians we need to be worrying about,” she said.

There is no research that supports the idea that asking physicians about mental illness improves patient safety. Not every state licensing board asks about psychiatric history, but many do ask these questions in a way that violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (Acad Med. 2009;84[6]:776-81). This is not a new issue: In 1993, The State Medical Society of New Jersey filed an injunction against the New Jersey medical board (Medical Society vs. Jacobs et al.) and questions asked on the licensing forms were changed.

Dr. Gold noted that if a physician checks yes to a question about a mental health history, the board response also varies. The doctor can be asked to provide a letter from his physician stating he is fit to work, or can be required to release all of his psychiatric record, or even to appear before the board to justify his fitness to practice.

Chae Kwak, LCSW-C, is the director of the Maryland Physician Health Program for Maryland MedChi. In the fall 2016 Board of Physicians newsletter, Kwak wrote, “An applicant has to affirmatively answer this question only if a current condition affects their ability to practice medicine. Diagnosis and/or treatment of mental health issues such as depression or anxiety is not the same as ‘impairment’ in the practice of medicine.”

Kwak was pleased that the board published his letter. “We want physicians to get the help they need. But this is not just about licensing boards, it’s an issue with hospital credentialing and applications for malpractice insurance as well.”

“We need to advocate on the level of the Federation of State Medical Boards on this subject, and there is a sense of increasing awareness that this is a problem, said Richard Summers, MD, who cochaired the American Psychiatric Association workshop on physician burnout and depression. “The increased salience and awareness of physician burnout, and its relationship to stigma might help this organization and the various state boards become more sympathetic and open to questioning the stigmatizing element of their questions. So, we’ve got to work on this situation both nationally and at the level of the state boards. Hopefully, some successes will stimulate others and will begin to help to change the culture of secrecy and shame.”

Nathaniel Morris, MD, is doing his psychiatry residency at Stanford (Calif.) University. He wrote about this issue in a Washington Post article, “Why doctors are leery about seeking mental health care for themselves” (Jan. 7, 2017). Morris wrote, “When I was a medical student, I suffered an episode of depression and refused to seek treatment for weeks. My fears about licensing applications were a major reason I kept quiet. I didn’t want a mark on my record. I didn’t want to check “yes” on those forms.”

Questions about mental health on licensing board applications were recently addressed by the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates meeting as part of Resolution 301. The AMA concluded with a suggestion that state medical boards inquire about mental health and physical health in a similar way and went on to suggest that boards not request psychotherapy records if the psychotherapy were a requirement of training. This is a profoundly disappointing and inadequate response from the AMA, and my hope is that the APA will move ahead with both words and actions that condemn stigmatizing inquiries.

Questions that differentiate other medical disabilities from psychiatric disabilities need to be stricken from licensing and credentialing forms. Our treatments work, and the cost of not getting care can be catastrophic for both physicians and for their patients. Why ask intrusive and detailed questions about mental illness or substance abuse, and not about diabetes control, seizures, hypotension, atrial fibrillation, or any illness that may cause impairment? It would seem enough to simply ask if the applicant suffers from any condition that impairs ability to function as a physician. Furthermore, it is unreasonable to ask for a full release of psychiatric records following an affirmative statement if detailed records of other illnesses are not required to confirm competency to practice and may prevent psychiatrists from being honest with their therapists. Self-report has limited value on applications, and questions about past sanctions, employment history, and criminal records are more likely to identify physicians who are impaired for any reason.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Physician burnout is rampant, and every seat was taken at a workshop on physician burnout and depression at this year’s APA annual meeting in San Diego.

In his book, “Why Physicians Die By Suicide” (Amazon, 2017), Michael F. Myers, MD, describes “burnout.”

Myers notes that there is no stigma to having burnout, as there is to having major depression – a condition that may have remarkably similar symptoms.

What stops physicians from getting help? It’s a complex question – especially in a group that has the means to access medical services – but one factor is that most state licensing boards specifically ask about mental illnesses and substance abuse in intrusive and stigmatizing ways. States vary both with their questions and with their responses to a box checked “yes.”

Katherine Gold, MD, MSW, MS, a family physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has studied the topic extensively. Her review of licensing questions from all 50 states revealed that most states ask for information about mental health, and there is tremendous variation as to what is asked (Fam Med. 2017 Jun;49[6]:464-7).

“Some states are very specific and very intrusive,” Gold noted. “They may ask if a physician has a specific diagnosis, a history of treatment or hospitalization. The questions may ask about current impairment, or they may ask about mental health conditions back to age 18 years. There may be very specific questions about diagnosis that are not asked about medical conditions, such as whether the applicant has kleptomania, pyromania, or seasonal affective disorder.”

Gold conducted an online survey of physician-mothers. Nearly half believed they had met criteria for an episode of mental illness at some point during their lives. Of those who did have a diagnosis, only 6% of physicians reported this on licensing forms, though she was quick to say that not all states ask for this information, and some may just ask about current impairment. “The people who are self-disclosing are probably not the physicians we need to be worrying about,” she said.

There is no research that supports the idea that asking physicians about mental illness improves patient safety. Not every state licensing board asks about psychiatric history, but many do ask these questions in a way that violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (Acad Med. 2009;84[6]:776-81). This is not a new issue: In 1993, The State Medical Society of New Jersey filed an injunction against the New Jersey medical board (Medical Society vs. Jacobs et al.) and questions asked on the licensing forms were changed.

Dr. Gold noted that if a physician checks yes to a question about a mental health history, the board response also varies. The doctor can be asked to provide a letter from his physician stating he is fit to work, or can be required to release all of his psychiatric record, or even to appear before the board to justify his fitness to practice.

Chae Kwak, LCSW-C, is the director of the Maryland Physician Health Program for Maryland MedChi. In the fall 2016 Board of Physicians newsletter, Kwak wrote, “An applicant has to affirmatively answer this question only if a current condition affects their ability to practice medicine. Diagnosis and/or treatment of mental health issues such as depression or anxiety is not the same as ‘impairment’ in the practice of medicine.”

Kwak was pleased that the board published his letter. “We want physicians to get the help they need. But this is not just about licensing boards, it’s an issue with hospital credentialing and applications for malpractice insurance as well.”

“We need to advocate on the level of the Federation of State Medical Boards on this subject, and there is a sense of increasing awareness that this is a problem, said Richard Summers, MD, who cochaired the American Psychiatric Association workshop on physician burnout and depression. “The increased salience and awareness of physician burnout, and its relationship to stigma might help this organization and the various state boards become more sympathetic and open to questioning the stigmatizing element of their questions. So, we’ve got to work on this situation both nationally and at the level of the state boards. Hopefully, some successes will stimulate others and will begin to help to change the culture of secrecy and shame.”

Nathaniel Morris, MD, is doing his psychiatry residency at Stanford (Calif.) University. He wrote about this issue in a Washington Post article, “Why doctors are leery about seeking mental health care for themselves” (Jan. 7, 2017). Morris wrote, “When I was a medical student, I suffered an episode of depression and refused to seek treatment for weeks. My fears about licensing applications were a major reason I kept quiet. I didn’t want a mark on my record. I didn’t want to check “yes” on those forms.”

Questions about mental health on licensing board applications were recently addressed by the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates meeting as part of Resolution 301. The AMA concluded with a suggestion that state medical boards inquire about mental health and physical health in a similar way and went on to suggest that boards not request psychotherapy records if the psychotherapy were a requirement of training. This is a profoundly disappointing and inadequate response from the AMA, and my hope is that the APA will move ahead with both words and actions that condemn stigmatizing inquiries.

Questions that differentiate other medical disabilities from psychiatric disabilities need to be stricken from licensing and credentialing forms. Our treatments work, and the cost of not getting care can be catastrophic for both physicians and for their patients. Why ask intrusive and detailed questions about mental illness or substance abuse, and not about diabetes control, seizures, hypotension, atrial fibrillation, or any illness that may cause impairment? It would seem enough to simply ask if the applicant suffers from any condition that impairs ability to function as a physician. Furthermore, it is unreasonable to ask for a full release of psychiatric records following an affirmative statement if detailed records of other illnesses are not required to confirm competency to practice and may prevent psychiatrists from being honest with their therapists. Self-report has limited value on applications, and questions about past sanctions, employment history, and criminal records are more likely to identify physicians who are impaired for any reason.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Physician burnout is rampant, and every seat was taken at a workshop on physician burnout and depression at this year’s APA annual meeting in San Diego.

In his book, “Why Physicians Die By Suicide” (Amazon, 2017), Michael F. Myers, MD, describes “burnout.”

Myers notes that there is no stigma to having burnout, as there is to having major depression – a condition that may have remarkably similar symptoms.

What stops physicians from getting help? It’s a complex question – especially in a group that has the means to access medical services – but one factor is that most state licensing boards specifically ask about mental illnesses and substance abuse in intrusive and stigmatizing ways. States vary both with their questions and with their responses to a box checked “yes.”

Katherine Gold, MD, MSW, MS, a family physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has studied the topic extensively. Her review of licensing questions from all 50 states revealed that most states ask for information about mental health, and there is tremendous variation as to what is asked (Fam Med. 2017 Jun;49[6]:464-7).

“Some states are very specific and very intrusive,” Gold noted. “They may ask if a physician has a specific diagnosis, a history of treatment or hospitalization. The questions may ask about current impairment, or they may ask about mental health conditions back to age 18 years. There may be very specific questions about diagnosis that are not asked about medical conditions, such as whether the applicant has kleptomania, pyromania, or seasonal affective disorder.”

Gold conducted an online survey of physician-mothers. Nearly half believed they had met criteria for an episode of mental illness at some point during their lives. Of those who did have a diagnosis, only 6% of physicians reported this on licensing forms, though she was quick to say that not all states ask for this information, and some may just ask about current impairment. “The people who are self-disclosing are probably not the physicians we need to be worrying about,” she said.

There is no research that supports the idea that asking physicians about mental illness improves patient safety. Not every state licensing board asks about psychiatric history, but many do ask these questions in a way that violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (Acad Med. 2009;84[6]:776-81). This is not a new issue: In 1993, The State Medical Society of New Jersey filed an injunction against the New Jersey medical board (Medical Society vs. Jacobs et al.) and questions asked on the licensing forms were changed.

Dr. Gold noted that if a physician checks yes to a question about a mental health history, the board response also varies. The doctor can be asked to provide a letter from his physician stating he is fit to work, or can be required to release all of his psychiatric record, or even to appear before the board to justify his fitness to practice.

Chae Kwak, LCSW-C, is the director of the Maryland Physician Health Program for Maryland MedChi. In the fall 2016 Board of Physicians newsletter, Kwak wrote, “An applicant has to affirmatively answer this question only if a current condition affects their ability to practice medicine. Diagnosis and/or treatment of mental health issues such as depression or anxiety is not the same as ‘impairment’ in the practice of medicine.”

Kwak was pleased that the board published his letter. “We want physicians to get the help they need. But this is not just about licensing boards, it’s an issue with hospital credentialing and applications for malpractice insurance as well.”

“We need to advocate on the level of the Federation of State Medical Boards on this subject, and there is a sense of increasing awareness that this is a problem, said Richard Summers, MD, who cochaired the American Psychiatric Association workshop on physician burnout and depression. “The increased salience and awareness of physician burnout, and its relationship to stigma might help this organization and the various state boards become more sympathetic and open to questioning the stigmatizing element of their questions. So, we’ve got to work on this situation both nationally and at the level of the state boards. Hopefully, some successes will stimulate others and will begin to help to change the culture of secrecy and shame.”

Nathaniel Morris, MD, is doing his psychiatry residency at Stanford (Calif.) University. He wrote about this issue in a Washington Post article, “Why doctors are leery about seeking mental health care for themselves” (Jan. 7, 2017). Morris wrote, “When I was a medical student, I suffered an episode of depression and refused to seek treatment for weeks. My fears about licensing applications were a major reason I kept quiet. I didn’t want a mark on my record. I didn’t want to check “yes” on those forms.”

Questions about mental health on licensing board applications were recently addressed by the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates meeting as part of Resolution 301. The AMA concluded with a suggestion that state medical boards inquire about mental health and physical health in a similar way and went on to suggest that boards not request psychotherapy records if the psychotherapy were a requirement of training. This is a profoundly disappointing and inadequate response from the AMA, and my hope is that the APA will move ahead with both words and actions that condemn stigmatizing inquiries.

Questions that differentiate other medical disabilities from psychiatric disabilities need to be stricken from licensing and credentialing forms. Our treatments work, and the cost of not getting care can be catastrophic for both physicians and for their patients. Why ask intrusive and detailed questions about mental illness or substance abuse, and not about diabetes control, seizures, hypotension, atrial fibrillation, or any illness that may cause impairment? It would seem enough to simply ask if the applicant suffers from any condition that impairs ability to function as a physician. Furthermore, it is unreasonable to ask for a full release of psychiatric records following an affirmative statement if detailed records of other illnesses are not required to confirm competency to practice and may prevent psychiatrists from being honest with their therapists. Self-report has limited value on applications, and questions about past sanctions, employment history, and criminal records are more likely to identify physicians who are impaired for any reason.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

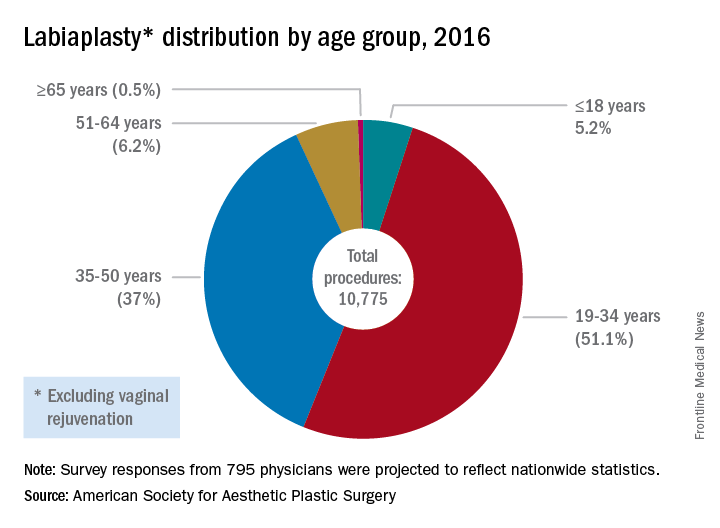

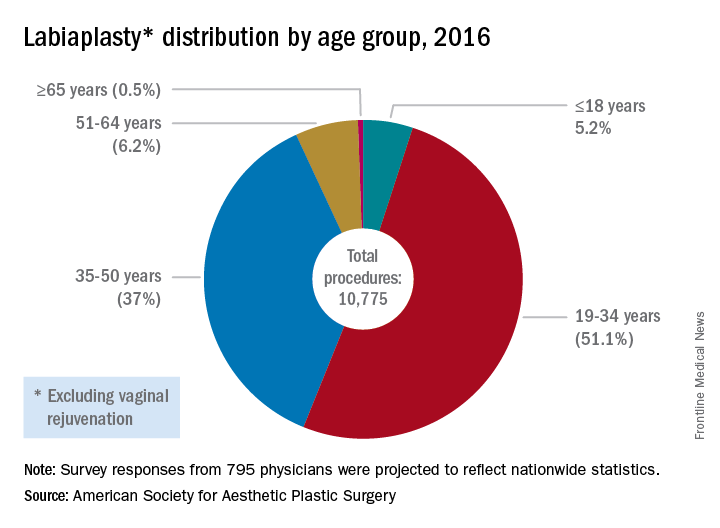

Is female genital cosmetic surgery going mainstream?

Experts describe the field of female genital cosmetic surgery as the “Wild West,” but the lack of regulation and consensus has not kept it from exploding in recent years.

More than 10,000 labiaplasties were performed in 2016, a 23% jump over the previous year, and the procedures are offered by more than 35% of all plastic surgeons, according to data from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. As another indicator of increasing attention to the appearance of female genitalia, a 2013 survey of U.S. women revealed that more than 80% performed some sort of pubic hair grooming (JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152[10]:1106-13).

Dr. Iglesia recounted being contacted by a National Gallery of Art staff member, who, when confronted with Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde, an 1866 below-the-waist portrait of a nude woman, asked, “Is this normal? Do women have this much hair?” Dr. Iglesia said she reassured the staff member that the woman in the portrait did indeed have a normal female Tanner stage IV or V escutcheon. However, she said, social media and other images in the popular press have essentially erased female pubic hair from the public eye, even in explicit imagery that involves female nudity.

“This is an ideal that men and women are seeing in social media, in pornography, and even in the lay press.” And now, she said, “We’re in a new era of sex surgeries, with these ‘nips and tucks’ below the belt.”

Labiaplasty

The combination of a newly-hairless genital region, together with portrayals of adult women with a “Barbie doll” appearance, may contribute to women feeling self-conscious about labia minora protruding beyond the labia majora. Dr. Iglesia, who is section director for female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., said this is true even though the normal length of labia minora can range from 7 mm to 5 cm.

That’s where labiaplasty comes in. The procedure, which can be performed with conventional surgical techniques or with a laser, is sometimes done for functional reasons.

The waters are murkier when labiaplasty is performed for cosmetic reasons, to get that “Barbie doll” look, with some offices advertising the procedure as “designer lips,” Dr. Iglesia said.

In 2007, ACOG issued a committee opinion expressing concern about the lack of data and sometimes deceptive marketing practices surrounding a number of cosmetic vaginal surgeries (Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:737–8). The policy was reaffirmed in 2017.

[polldaddy:{"method":"iframe","type":"survey","src":"//newspolls2017.polldaddy.com/s/is-it-appropriate-to-perform-gynecologic-procedures-such-as-labiaplasty-for-cosmetic-reasons?iframe=1"}]Similarly, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada issued a 2013 statement about labiaplasty and other female genital cosmetic surgeries saying that “there is little evidence to support any of the female genital cosmetic surgeries in terms of improvement to sexual satisfaction or self-images. Physicians choosing to proceed with these cosmetic procedures should not promote these surgeries for the enhancement of sexual function and advertising of female genital cosmetic surgical procedures should be avoided.”

However, Mickey Karram, MD, who is director of the urogynecology program at Christ Hospital, Cincinnatti, said that informed consent is the key to dealing appropriately with these procedures.

“If a patient is physically bothered from a cosmetic standpoint that her labia are larger than she thinks they should be, and they are bothering her, is it appropriate or inappropriate to potentially discuss with her a labiaplasty?” Dr. Karram said at the ACOG meeting. For the patient who understands the risk and is also clear that the procedure is not medically necessary, he said he “feels strongly” that labiaplasty should be an option.

Fractional laser

The introduction of the fractional laser to gynecology is also adding to the debate about the appropriate integration of gynecologic procedures that may have nonmedical uses, such as vaginal “tightening.” Used primarily intravaginally, these devices have shallow penetration and are meant to stimulate collagen, proteoglycan, and hyaluronic acid synthesis with minimal tissue damage and downtime. One such device, the MonaLisa Touch, is marketed in the United States by Cynosure.

These energy sources hold great promise for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) and other conditions, Dr. Karram said. “Many of these energy sources are being promoted for actual disease states, like vulvovaginal atrophy and lichen sclerosus,” he said.

Dr. Iglesia is not so sure: “This is not the fountain of youth.” She pointed out that the vasculature and innervation of the vagina and vulva are complex, with the outer one-eighth of the vagina being much more highly innervated. Laser treatment with a shallow penetration depth may not get at all of the issues that contribute to GSM.

“Is marketing ahead of the science? I would say yes,” she said. “There’s too much hype about this curing vaginal dryness and making your sex life better.”

Dr. Zahn also urged caution with the use of this technology. “The data are very limited, but, despite this, it’s become a very popular and highly-advertised approach. We need larger studies and more longitudinal data. This is especially true since one of the proposed ways this device works is by stimulating fibrosis. In every other body system, fibrosis stimulation may result in scarring. We have no idea if this is the case with this device. If it is, its application could result in worsening of bodily function, especially in regard to dyspareunia,” he said. “We clearly need more data.”

In 2016, ACOG issued a position statement about the fractional carbon dioxide and yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser systems that had received clearance from the Food and Drug Administration. The statement advised both ob.gyns. and patients that “this technology is, in fact, neither approved nor cleared by the FDA for the specific indication of treating vulvovaginal atrophy.”

Both Dr. Karram and Dr. Iglesia are investigators in an ongoing randomized, placebo- and sham-controlled trial comparing vaginal estrogen and laser therapy used both in conjunction and singly.

‘No-go’ procedures

Though Dr. Karram and Dr. Iglesia disagree on whether cosmetic labiaplasty is appropriate, they were in agreement that certain procedures are so untested, or have such potential risk with no proven benefit, that they should not be performed at all. The procedures on both physicians’ “no-go” lists included clitoral unhooding, G-spot amplification, “revirginification” in any form, vulval recontouring with autologous fat, and the so-called “O-shot,” injections of platelet-rich plasma that are touted as augmenting the sexual experience.

What’s to be done?

There is also agreement that a lack of common terminology is a significant problem. Step one, Dr. Karram said, is doing away with the term vaginal rejuvenation. “This is a terrible term. … There’s no real definition for this term.” He called for a multidisciplinary working group that would bring together gynecologists, plastic surgeons, and dermatologists to begin the work of terminology standardization.

From there, he proposed that the group develop a classification system that clarifies whether procedures are being done for cosmetic reasons, to enhance the sexual experience, or to address a specific disease state. Finally, he said, the group should recommend standardized outcome metrics that can be used to study the various interventions.

Dr. Zahn applauded this notion. “It’s a great point. I agree that multiple disciplines should be involved in examining outcomes, statistics, and criteria for evaluating procedures.”

And gynecologists should be leading this effort, Dr. Karram suggested. “Who knows this anatomy the best? We do.” He added, “If it’s going to be addressed, it should be addressed by us.”

But, Dr. Iglesia said she worries about vulnerable populations, such as adolescents and cancer survivors, who may undergo surgeries, for which the benefits may not outweigh the potential risks. For labiaplasty and laser resurfacing techniques, there have been a small number of studies on outcomes and patient satisfaction that have generally been conducted at single centers with no comparison arms and limited follow-up, she said.