User login

Now is time to embrace emerging PAD interventions

CHICAGO – Bioresorbable scaffolds, new drugs, adjuvant interventions, and stem and progenitor cell therapy will change how vascular surgeons treat peripheral artery disease in the next 5 years, so they must embrace these emerging treatments or run the risk of being displaced by other specialists, according to a presentation at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Vascular surgeons must position their practices to be the nexus for the evaluation and treatment of the patient and proactively engage in the critical trials of these new technologies,” said Patrick J. Geraghty, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis. “If our specialty fails to adapt to new treatment options, we risk getting sidelined as critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment moves into a multimodality model.”

Dr. Geraghty focused on several future directions for PAD treatment: improved drug-eluting stents (DES) for superficial femoral artery disease; drug-coated balloons and modified DES for infrapopliteal disease; biologic modifiers for claudication and CLI; and bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

“You’re not simply a plumber anymore; you’re a biological response modifier,” Dr. Geraghty said, explaining that biologic response modification technologies are the logical successor where standard surgical and endovascular techniques have either fallen short (as in early patency loss due to restenosis) or failed to offer effective alternatives (as in no-option advanced CLI patients). “And that takes many of us out of our comfort zone,” he said.

Dr. Geraghty noted the VIBRANT trial (J Vasc Surg. 2013;58[2]:386-95) and similar studies of non–drug eluting constructs identified early restenosis as the primary culprit in endovascular patency loss. “If you could reduce those early patency losses, you’d have an admirable primary patency rate for these complex lesions,” he said. “We’re able to reconstruct a vessel lumen. The question is, how to best maintain it?”

To answer that, Dr. Geraghty noted that the SIROCCO II trial (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16[3]:331-8) failed to show an advantage for a sirolimus-eluting stent over bare nitinol stent for superficial femoral artery (SFA) disease, but the subsequent Zilver PTX trial showed the benefits of paclitaxel-eluting stents over 5 years (Circulation. 2016;133[15]:1472-83).

He noted that drug-coated balloons (DCBs) trials have yielded mixed results in infrapopliteal intervention. Most notably, the multicenter In.Pact DEEP trial (Circulation. 2015;131[5]:495-502) failed to show treatment efficacy, Dr. Geraghty said. “The In.Pact DEEP results sharply contrasted with the positive data from trials of similar DCBs in the SFA” (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[2]:145-53).

With regard to DES for infrapopliteal disease, Dr. Geraghty noted the promise of positive results of the ACHILLES (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60[22]:2290-5) and DESTINY (J Vasc Surg. 2012;55[2]:390-9) trials, along with the modest structural changes needed to convert from coronary to proximal tibial applications.

Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) for CLI have also made recent advances. “It has been a slow road, but I’m happy that industry has pursued this aggressively,” Dr. Geraghty said. He pointed out that the ESPRIT I trial of bioresorbable everolimus-eluting vascular scaffolds in PAD involving the external iliac artery and SFA reported restenosis rates of 12.1% and 16.1% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[11]:1178-87). A trial of the Absorb BVS (Abbott) for short infrapopliteal lesions showed primary patency rates of 96% and 85% at 1 and 2 years, he said (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[7]:715-24).

“Vascular surgeons should be tracking BVS technology closely,” Dr. Geraghty said. “It achieves multiple desirable goals: immediate scaffolding for luminal restoration; mitigation of the restenotic stimulus via stent resorption; drug delivery for inhibition of restenosis; and the prospect of simpler re-interventions.”

Stem/progenitor cell therapies may also provide new solutions for no-option vasculature. One trial that showed “promising trends,” Dr. Geraghty said, is the RESTORE-CLI study of bone marrow aspiration (Mol Ther. 2012;20[6]:1280-6). “This trial reported a trend toward improved time to failure and reduced amputation-free survival, but did not meet its primary endpoint,” he said. “Likewise, the recently presented Biomet MOBILE data failed to meet its primary endpoint, but showed favorable trends in some treatment subgroups” (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54[6]:1650-8).

Dr. Geraghty noted that trial design in this field may need to change directions. “Look at the Delphi consensus matrices for the WIfI (Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection) Threatened limb Classification System (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59[1]:220-34). These show that complex wounds bear a significant risk of amputation, perhaps unmitigated by successful revascularization.” In addition, he called amputation-free survival “a rather blunt instrument” for evaluating how therapies impact limb outcomes and said it can confound the analysis of their effectiveness.

“Instead of confining the progenitor-cell therapies to no-option CLI trials, I’m eager to also see them investigated for treatment of claudication,” Dr. Geraghty said. “Can cell-based therapies possibly displace endovascular interventions as the first-line, least-harmful option for claudication?”

Dr. Geraghty also touched on intra/extravascular adjuvant therapies: antithrombin nanoparticles; inhibitory nanoparticles and polymeric wraps; and adventitial drug delivery techniques, among others.

“It’s critically important for vascular surgeons to position themselves for continued success in CLI treatment,” he said. “That involves aggressive practice branding, active trial participation, critical analysis of new technologies, and adoption of new, even disruptive, treatment modalities that show patient benefit.”

Dr. Geraghty disclosed stock ownership in Pulse Therapeutics; consultant fees from Bard Peripheral Vascular, Boston Scientific, Intact Vascular, Bard/Lutonix and Spectranetics; and serving as principal investigator for trials by Cook Medical, Bard/Lutonix, and Intact Vascular, with fees going to Washington University Medical School.

CHICAGO – Bioresorbable scaffolds, new drugs, adjuvant interventions, and stem and progenitor cell therapy will change how vascular surgeons treat peripheral artery disease in the next 5 years, so they must embrace these emerging treatments or run the risk of being displaced by other specialists, according to a presentation at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Vascular surgeons must position their practices to be the nexus for the evaluation and treatment of the patient and proactively engage in the critical trials of these new technologies,” said Patrick J. Geraghty, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis. “If our specialty fails to adapt to new treatment options, we risk getting sidelined as critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment moves into a multimodality model.”

Dr. Geraghty focused on several future directions for PAD treatment: improved drug-eluting stents (DES) for superficial femoral artery disease; drug-coated balloons and modified DES for infrapopliteal disease; biologic modifiers for claudication and CLI; and bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

“You’re not simply a plumber anymore; you’re a biological response modifier,” Dr. Geraghty said, explaining that biologic response modification technologies are the logical successor where standard surgical and endovascular techniques have either fallen short (as in early patency loss due to restenosis) or failed to offer effective alternatives (as in no-option advanced CLI patients). “And that takes many of us out of our comfort zone,” he said.

Dr. Geraghty noted the VIBRANT trial (J Vasc Surg. 2013;58[2]:386-95) and similar studies of non–drug eluting constructs identified early restenosis as the primary culprit in endovascular patency loss. “If you could reduce those early patency losses, you’d have an admirable primary patency rate for these complex lesions,” he said. “We’re able to reconstruct a vessel lumen. The question is, how to best maintain it?”

To answer that, Dr. Geraghty noted that the SIROCCO II trial (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16[3]:331-8) failed to show an advantage for a sirolimus-eluting stent over bare nitinol stent for superficial femoral artery (SFA) disease, but the subsequent Zilver PTX trial showed the benefits of paclitaxel-eluting stents over 5 years (Circulation. 2016;133[15]:1472-83).

He noted that drug-coated balloons (DCBs) trials have yielded mixed results in infrapopliteal intervention. Most notably, the multicenter In.Pact DEEP trial (Circulation. 2015;131[5]:495-502) failed to show treatment efficacy, Dr. Geraghty said. “The In.Pact DEEP results sharply contrasted with the positive data from trials of similar DCBs in the SFA” (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[2]:145-53).

With regard to DES for infrapopliteal disease, Dr. Geraghty noted the promise of positive results of the ACHILLES (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60[22]:2290-5) and DESTINY (J Vasc Surg. 2012;55[2]:390-9) trials, along with the modest structural changes needed to convert from coronary to proximal tibial applications.

Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) for CLI have also made recent advances. “It has been a slow road, but I’m happy that industry has pursued this aggressively,” Dr. Geraghty said. He pointed out that the ESPRIT I trial of bioresorbable everolimus-eluting vascular scaffolds in PAD involving the external iliac artery and SFA reported restenosis rates of 12.1% and 16.1% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[11]:1178-87). A trial of the Absorb BVS (Abbott) for short infrapopliteal lesions showed primary patency rates of 96% and 85% at 1 and 2 years, he said (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[7]:715-24).

“Vascular surgeons should be tracking BVS technology closely,” Dr. Geraghty said. “It achieves multiple desirable goals: immediate scaffolding for luminal restoration; mitigation of the restenotic stimulus via stent resorption; drug delivery for inhibition of restenosis; and the prospect of simpler re-interventions.”

Stem/progenitor cell therapies may also provide new solutions for no-option vasculature. One trial that showed “promising trends,” Dr. Geraghty said, is the RESTORE-CLI study of bone marrow aspiration (Mol Ther. 2012;20[6]:1280-6). “This trial reported a trend toward improved time to failure and reduced amputation-free survival, but did not meet its primary endpoint,” he said. “Likewise, the recently presented Biomet MOBILE data failed to meet its primary endpoint, but showed favorable trends in some treatment subgroups” (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54[6]:1650-8).

Dr. Geraghty noted that trial design in this field may need to change directions. “Look at the Delphi consensus matrices for the WIfI (Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection) Threatened limb Classification System (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59[1]:220-34). These show that complex wounds bear a significant risk of amputation, perhaps unmitigated by successful revascularization.” In addition, he called amputation-free survival “a rather blunt instrument” for evaluating how therapies impact limb outcomes and said it can confound the analysis of their effectiveness.

“Instead of confining the progenitor-cell therapies to no-option CLI trials, I’m eager to also see them investigated for treatment of claudication,” Dr. Geraghty said. “Can cell-based therapies possibly displace endovascular interventions as the first-line, least-harmful option for claudication?”

Dr. Geraghty also touched on intra/extravascular adjuvant therapies: antithrombin nanoparticles; inhibitory nanoparticles and polymeric wraps; and adventitial drug delivery techniques, among others.

“It’s critically important for vascular surgeons to position themselves for continued success in CLI treatment,” he said. “That involves aggressive practice branding, active trial participation, critical analysis of new technologies, and adoption of new, even disruptive, treatment modalities that show patient benefit.”

Dr. Geraghty disclosed stock ownership in Pulse Therapeutics; consultant fees from Bard Peripheral Vascular, Boston Scientific, Intact Vascular, Bard/Lutonix and Spectranetics; and serving as principal investigator for trials by Cook Medical, Bard/Lutonix, and Intact Vascular, with fees going to Washington University Medical School.

CHICAGO – Bioresorbable scaffolds, new drugs, adjuvant interventions, and stem and progenitor cell therapy will change how vascular surgeons treat peripheral artery disease in the next 5 years, so they must embrace these emerging treatments or run the risk of being displaced by other specialists, according to a presentation at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Vascular surgeons must position their practices to be the nexus for the evaluation and treatment of the patient and proactively engage in the critical trials of these new technologies,” said Patrick J. Geraghty, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis. “If our specialty fails to adapt to new treatment options, we risk getting sidelined as critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment moves into a multimodality model.”

Dr. Geraghty focused on several future directions for PAD treatment: improved drug-eluting stents (DES) for superficial femoral artery disease; drug-coated balloons and modified DES for infrapopliteal disease; biologic modifiers for claudication and CLI; and bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

“You’re not simply a plumber anymore; you’re a biological response modifier,” Dr. Geraghty said, explaining that biologic response modification technologies are the logical successor where standard surgical and endovascular techniques have either fallen short (as in early patency loss due to restenosis) or failed to offer effective alternatives (as in no-option advanced CLI patients). “And that takes many of us out of our comfort zone,” he said.

Dr. Geraghty noted the VIBRANT trial (J Vasc Surg. 2013;58[2]:386-95) and similar studies of non–drug eluting constructs identified early restenosis as the primary culprit in endovascular patency loss. “If you could reduce those early patency losses, you’d have an admirable primary patency rate for these complex lesions,” he said. “We’re able to reconstruct a vessel lumen. The question is, how to best maintain it?”

To answer that, Dr. Geraghty noted that the SIROCCO II trial (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16[3]:331-8) failed to show an advantage for a sirolimus-eluting stent over bare nitinol stent for superficial femoral artery (SFA) disease, but the subsequent Zilver PTX trial showed the benefits of paclitaxel-eluting stents over 5 years (Circulation. 2016;133[15]:1472-83).

He noted that drug-coated balloons (DCBs) trials have yielded mixed results in infrapopliteal intervention. Most notably, the multicenter In.Pact DEEP trial (Circulation. 2015;131[5]:495-502) failed to show treatment efficacy, Dr. Geraghty said. “The In.Pact DEEP results sharply contrasted with the positive data from trials of similar DCBs in the SFA” (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[2]:145-53).

With regard to DES for infrapopliteal disease, Dr. Geraghty noted the promise of positive results of the ACHILLES (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60[22]:2290-5) and DESTINY (J Vasc Surg. 2012;55[2]:390-9) trials, along with the modest structural changes needed to convert from coronary to proximal tibial applications.

Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) for CLI have also made recent advances. “It has been a slow road, but I’m happy that industry has pursued this aggressively,” Dr. Geraghty said. He pointed out that the ESPRIT I trial of bioresorbable everolimus-eluting vascular scaffolds in PAD involving the external iliac artery and SFA reported restenosis rates of 12.1% and 16.1% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[11]:1178-87). A trial of the Absorb BVS (Abbott) for short infrapopliteal lesions showed primary patency rates of 96% and 85% at 1 and 2 years, he said (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[7]:715-24).

“Vascular surgeons should be tracking BVS technology closely,” Dr. Geraghty said. “It achieves multiple desirable goals: immediate scaffolding for luminal restoration; mitigation of the restenotic stimulus via stent resorption; drug delivery for inhibition of restenosis; and the prospect of simpler re-interventions.”

Stem/progenitor cell therapies may also provide new solutions for no-option vasculature. One trial that showed “promising trends,” Dr. Geraghty said, is the RESTORE-CLI study of bone marrow aspiration (Mol Ther. 2012;20[6]:1280-6). “This trial reported a trend toward improved time to failure and reduced amputation-free survival, but did not meet its primary endpoint,” he said. “Likewise, the recently presented Biomet MOBILE data failed to meet its primary endpoint, but showed favorable trends in some treatment subgroups” (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54[6]:1650-8).

Dr. Geraghty noted that trial design in this field may need to change directions. “Look at the Delphi consensus matrices for the WIfI (Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection) Threatened limb Classification System (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59[1]:220-34). These show that complex wounds bear a significant risk of amputation, perhaps unmitigated by successful revascularization.” In addition, he called amputation-free survival “a rather blunt instrument” for evaluating how therapies impact limb outcomes and said it can confound the analysis of their effectiveness.

“Instead of confining the progenitor-cell therapies to no-option CLI trials, I’m eager to also see them investigated for treatment of claudication,” Dr. Geraghty said. “Can cell-based therapies possibly displace endovascular interventions as the first-line, least-harmful option for claudication?”

Dr. Geraghty also touched on intra/extravascular adjuvant therapies: antithrombin nanoparticles; inhibitory nanoparticles and polymeric wraps; and adventitial drug delivery techniques, among others.

“It’s critically important for vascular surgeons to position themselves for continued success in CLI treatment,” he said. “That involves aggressive practice branding, active trial participation, critical analysis of new technologies, and adoption of new, even disruptive, treatment modalities that show patient benefit.”

Dr. Geraghty disclosed stock ownership in Pulse Therapeutics; consultant fees from Bard Peripheral Vascular, Boston Scientific, Intact Vascular, Bard/Lutonix and Spectranetics; and serving as principal investigator for trials by Cook Medical, Bard/Lutonix, and Intact Vascular, with fees going to Washington University Medical School.

AT THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Emerging treatments for lower-extremity interventions range from improved drug-eluting stents for the superficial femoral artery and infrapopliteal disease to bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

Major finding: The future of minimally invasive revascularization hinges on reliably reopening stenosed or occluded arteries, maintaining vessel patency and using therapies to stimulate arteriogenesis or angiogenesis without reintervention.

Data source: Review of literature.

Disclosures: Dr. Geraghty disclosed stock ownership in Pulse Therapeutics; consultant fees from Bard Peripheral Vascular, Boston Scientific, Intact Vascular, Bard/Lutonix and Spectranetics; and serving as principal investigator for trials by Cook Medical, Bard/Lutonix, and Intact Vascular, with fees going to Washington University Medical School.

Questioning the Specificity and Sensitivity of ELISA for Bullous Pemphigoid Diagnosis

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease. The classic presentation of BP is a generalized, pruritic, bullous eruption in elderly patients, which is occasionally preceded by an urticarial prodrome. Immunopathologically, BP is characterized by IgG and sometimes IgE autoantibodies that target basement membrane zone proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermis.1

The diagnosis of BP should be suspected when an elderly patient presents with tense blisters and can be confirmed via diagnostic testing, including tissue histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as the gold standard, as well as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and most recently biochip technology as supportive tests.2 Since its advent, ELISA has gained popularity as a trustworthy diagnostic test for BP. The specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis is reported to be 98% to 100%, which leads clinicians to believe that a positive ELISA equals certain diagnosis of BP; however, misdiagnosis of BP based on a positive ELISA result can occur.3-13 The treatment of BP often involves lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Complications of immunosuppressive therapy contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients, thus an accurate diagnosis is paramount before introducing therapy.14

We present the case of a 74-year-old man with a history of a pruritic nonbullous eruption who was diagnosed with BP and treated for 3 years based on positive ELISA results in the absence of confirmatory histology or DIF.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and obstructive sleep apnea presented for further evaluation and confirmation of a prior diagnosis of BP by an outside dermatologist. He reported a pruritic rash on the trunk, back, and extremities of 3 years’ duration. He denied occurrence of blisters at any time.

On presentation to an outside dermatologist 3 years ago, a biopsy was performed along with serologic studies due to the patient’s age and the possibility of an urticarial prodrome in BP. The biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, subepidermal separation, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the papillary dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was nondiagnostic with a weak discontinuous pattern of IgG and IgA linearly along the basement membrane zone as well as few scattered and clumped cytoid bodies of IgM and IgA. Indirect immunofluoresence revealed a positive IgG titer of 1:40 on monkey esophagus substrate and a positive epidermal pattern on human split-skin substrate with a titer of 1:80. An ELISA for IgG autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 yielded 15 U and 6 U, respectively (cut off value, 9 U). Based on the positive ELISA for IgG against BP180, a diagnosis of BP was made.

Over the following 3 years, the treatment included prednisone, tetracycline, nicotinamide, doxycycline, and dapsone. Therapy was suboptimal due to the patient’s comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus precluded consistent use of prednisone as recommended for BP. Tetracycline and nicotinamide were transiently effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms but were discontinued due to changes in his health insurance. Doxycycline and dapsone were ineffective. Throughout this 3-year period, the patient remained blister free, but the pruritic eruption was persistent.

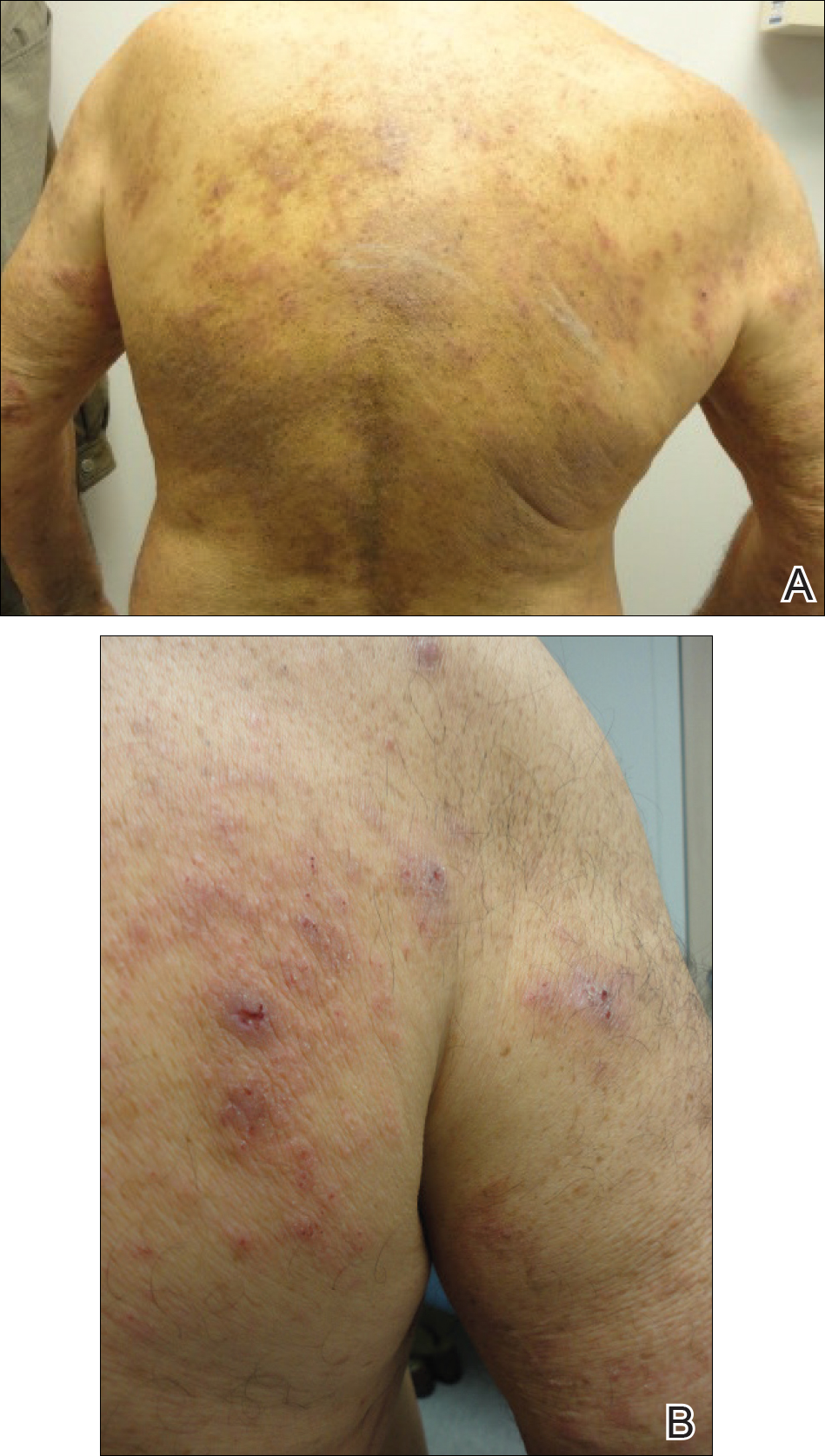

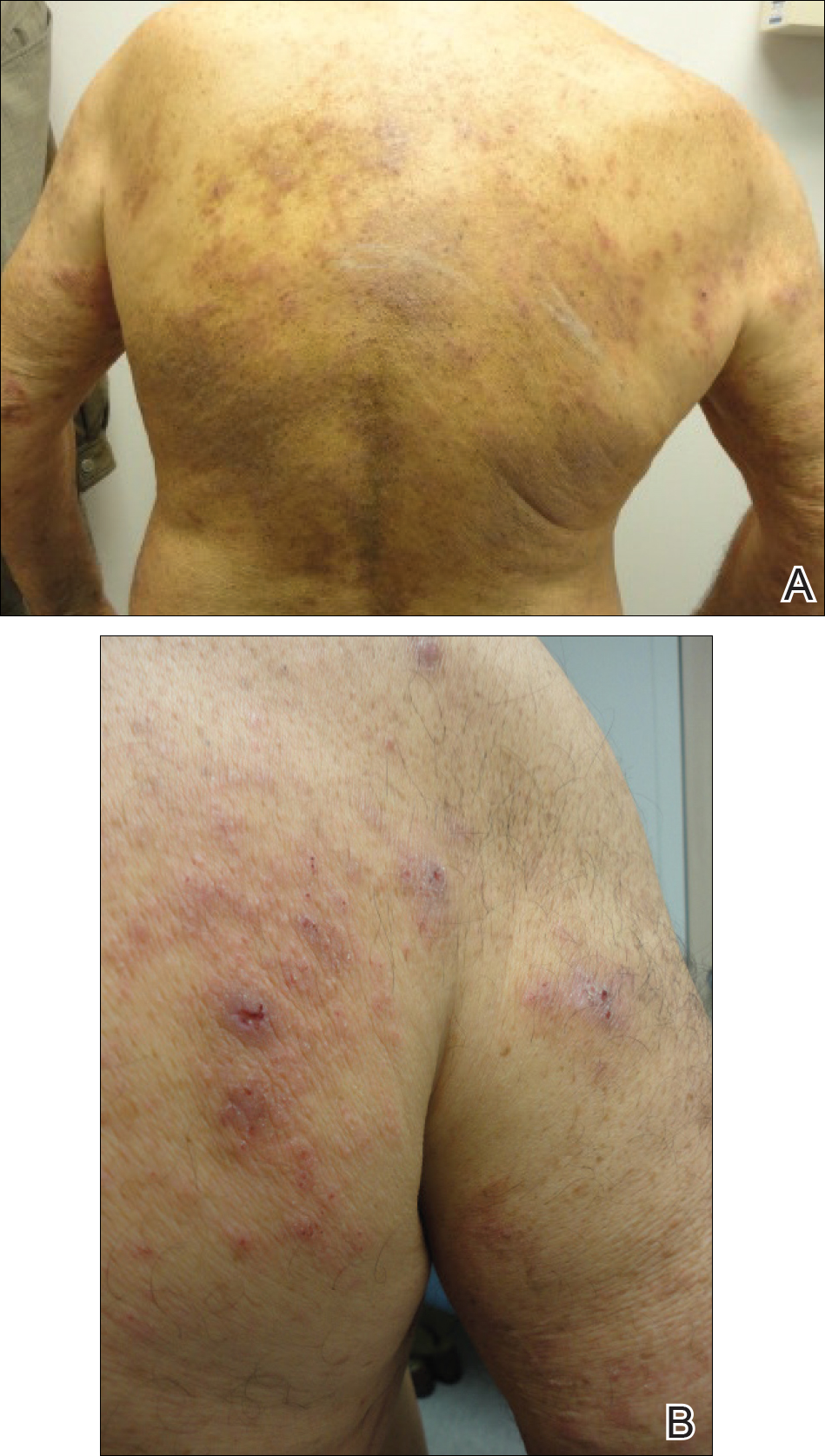

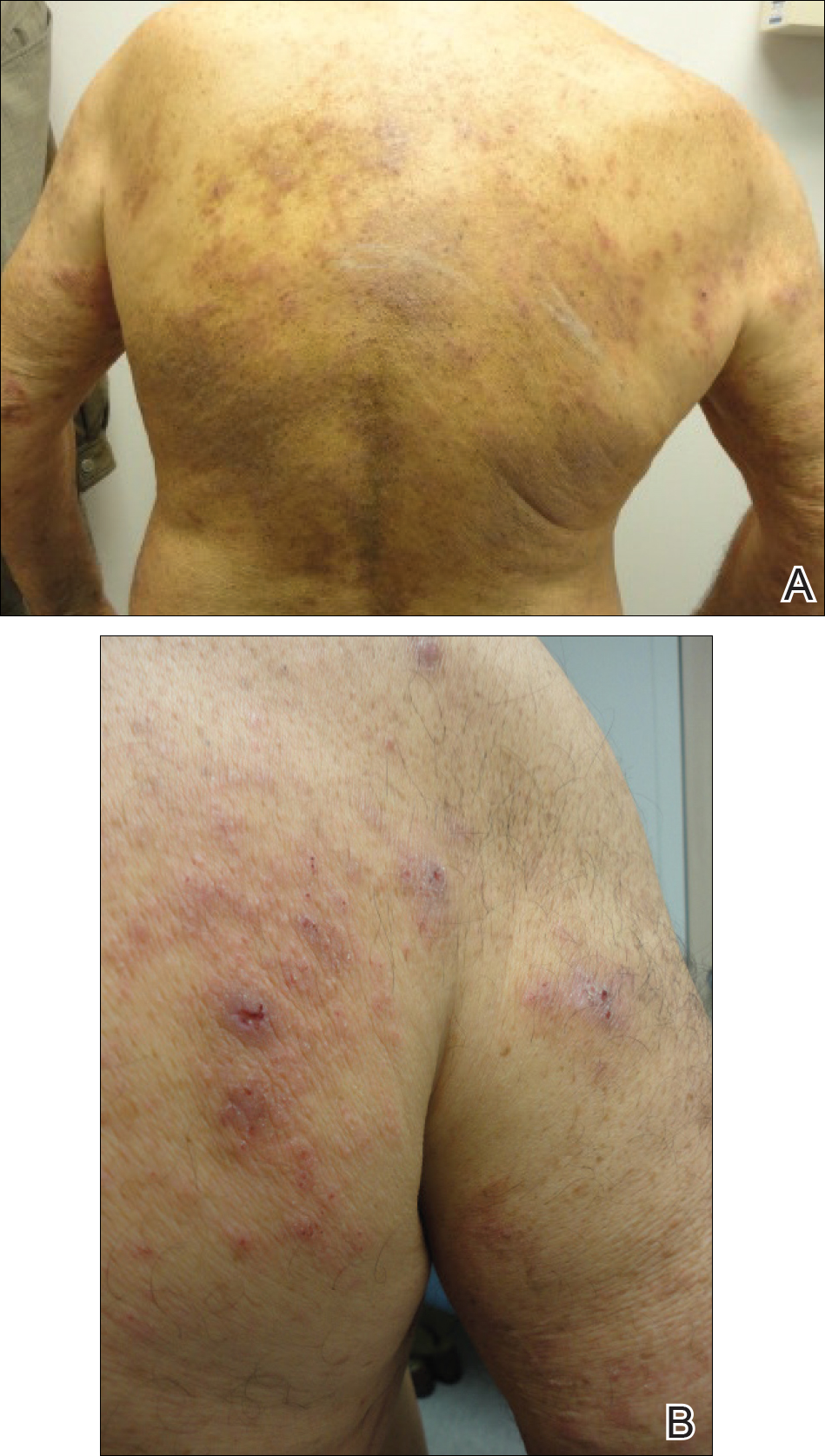

The patient presented to our clinic due to his frustration with the lack of improvement and doubts about the BP diagnosis given the persistent absence of bullous lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous eroded, scaly, crusted papules on erythematous edematous plaques on all extremities, trunk, and back (Figure 1). The head, neck, face, and oral mucosa were spared. His history and clinical findings were atypical for BP and skin biopsies were performed. Histology revealed epidermal erosion with parakeratosis, spongiosis, and superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with rare eosinophils without subepidermal split (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Additionally, further review of the initial histology by another dermatopathologist revealed that the subepidermal separation reported was more likely artifactual clefts. These findings were not consistent with BP.

Given the patient’s clinical history, lack of bullae, and twice-negative DIF, the diagnosis was determined to be more consistent with eczematous spongiotic dermatitis. He refused a referral for phototherapy due to scheduling inconvenience. The patient was started on cyclosporine 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. After 10 days of treatment, he returned for follow-up and reported notable improvement in the pruritus. On physical examination, his dermatitis was improved with decreased erythema and inflammation.

The patient is being continued on extensive dry skin care with thick moisturizers and additional topical corticosteroid application on an as-needed basis.

Comment

Chronic immunosuppression contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with BP; therefore, accurate diagnosis of BP is of utmost importance.14 A meta-analysis described ELISA as a test with high sensitivity and specificity (87% and 98%–100%, respectively) for diagnosis of BP.3 Nevertheless, there are opportunities for misdiagnosis using ELISA, as demonstrated in our case. To determine if the reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA is accurate and reliable for clinical use, individual studies from the meta-analysis were reviewed.4,5,7-10,13,15 Issues identified in our review included dissimilar diagnostic procedures and patient populations among individual studies, several reports of positive ELISA in patients without BP, and a lack of explanation for these false-positive results.

There are notable differences in diagnostic procedures and patient populations among reports that establish the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis.3-13 Studies have detected IgG that targets the NC16A domain of the BP180 kD antigen, the C-terminal of the BP180 kD antigen, or the entire ectodomain of the BP180 kD antigen. Study patient populations varied in disease activity, stage, and treatment. Control patients included healthy patients as well as those with many dermatoses, including pemphigus vulgaris, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematosus.3-13 Due to these differences between individual studies, we believe the results that determine the overall sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis must be interpreted with caution. For ELISA statistics to be clinically applicable to a specific patient, he/she should be similar to the patients studied. Therefore, we believe each study must be evaluated individually for applicability, given the differences that exist between them.

Furthermore, there have been several reports of false-positive ELISA results in patients with other dermatologic disorders, specifically in elderly patients with pruritus who do not fulfill clinical criteria for diagnosis with BP.16-18 In a population of elderly patients with pruritus for which no specific dermatological or systemic cause was identified, Hofmann et al18 found that 12% (3/25) of patients showed IgG reactivity to BP180 despite having negative DIF results. In another study of elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses, Feliciani et al17 found that 33% (5/15) of patients had IgG reactivity against BP230 or BP180, though they did not fulfill BP criteria based on clinical presentation and showed negative DIF and IIF results. These findings suggest that IgG reactivity against BP autoantibodies as determined by ELISA is not uncommon in pruritic diseases of the elderly.

Explanations for false-positive ELISA results were rare. A few authors suggested that false-positives could be attributed to an excessively low cutoff value,7-9 which was consistent with reports that the titer of autoantibodies to BP180 correlates with disease severity, suggesting that the higher titer of antibodies correlates with more severe disease and likely more accurate diagnosis.10,19,20 It is important to consider that patients who have low titers of BP180 autoantibodies with inconsistent clinical characteristics and DIF results may not truly have BP. Furthermore, to determine the clinical value of ELISA in identifying patients in the initial phase of BP, sera of BP patients should be compared with sera of elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders because they comprise the patient population that often requires diagnosis.18

Given the issues identified in our review of the literature, the published sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis are likely overstated. In conclusion, ELISA should not be relied on as a single criterion adequate for diagnosis of BP.12,21 Rather, the diagnosis of BP can be obtained with a positive predictive value of 95% when a patient meets 3 of 4 clinical criteria (ie, absence of atrophic scars, absence of head and neck involvement, absence of mucosal involvement, and older than 70 years) and demonstrates linear deposits of predominantly IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone of a perilesional biopsy on DIF.15 The gold standard for diagnosis of BP remains clinical presentation along with DIF, which can be supported by histology, IIF, and ELISA.22

- Delaporte E, Dubost-Brama A, Ghohestani R, et al. IgE autoantibodies directed against the major bullous pemphigoid antigen in patients with a severe form of pemphigoid. J Immunol. 1996;157:3642-3647.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Diagnosis and clinical severity markers of bullous pemphigoid. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:15.

- Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:121-126.

- Zillikens D, Mascaro JM, Rose PA, et al. A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of circulating anti-BP180 autoantibodies in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:679-683.

- Sitaru C, Dahnrich C, Probst C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using multimers of the 16th non-collagenous domain of the BP180 antigen for sensitive and specific detection of pemphigoid autoantibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:770-777.

- Yang B, Wang C, Chen S, et al. Evaluation of the combination of BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:722-727.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Oyama N, et al. Evaluation of a BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:126-131.

- Tampoia M, Lattanzi V, Zucano A, et al. Evaluation of a new ELISA assay for detection of BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:15-20.

- Feng S, Lin L, Jin P, et al. Role of BP180NC16a-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in China. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:24-28.

- Kobayashi M, Amagai M, Kuroda-Kinoshita K, et al. BP180 ELISA using bacterial recombinant NC16a protein as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:224-232.

- Roussel A, Benichou J, Arivelo Randriamanantany Z, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the combination of bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:293-298.

- Chan, Lawrence S. ELISA instead of indirect IF in patients with BP. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:291-292.

- Barnadas MA, Rubiales V, González J, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence testing in a bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1245-1249.

- Borradori L, Bernard P. Pemphigoid group. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:469.

- Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1075-1080.

- Fania L, Caldarola G, Muller R, et al. IgE recognition of bullous pemphigoid (BP)180 and BP230 in BP patients and elderly individuals with pruritic dermatoses. Clin Immunol. 2012;143:236-245.

- Feliciani C, Caldarola G, Kneisel A, et al. IgG autoantibody reactivity against bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and BP230 in elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;61:306-312.

- Hofmann SC, Tamm K, Hertl M, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using BP180 recombinant proteins in elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:910-911.

- Schmidt E, Obe K, Brocker EB, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:174-178.

- Feng S, Wu Q, Jin P, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:225-228.

- Di Zenzo G, Joly P, Zambruno G, et al. Sensitivity of immunofluorescence studies vs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1454-1456.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:84-89.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease. The classic presentation of BP is a generalized, pruritic, bullous eruption in elderly patients, which is occasionally preceded by an urticarial prodrome. Immunopathologically, BP is characterized by IgG and sometimes IgE autoantibodies that target basement membrane zone proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermis.1

The diagnosis of BP should be suspected when an elderly patient presents with tense blisters and can be confirmed via diagnostic testing, including tissue histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as the gold standard, as well as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and most recently biochip technology as supportive tests.2 Since its advent, ELISA has gained popularity as a trustworthy diagnostic test for BP. The specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis is reported to be 98% to 100%, which leads clinicians to believe that a positive ELISA equals certain diagnosis of BP; however, misdiagnosis of BP based on a positive ELISA result can occur.3-13 The treatment of BP often involves lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Complications of immunosuppressive therapy contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients, thus an accurate diagnosis is paramount before introducing therapy.14

We present the case of a 74-year-old man with a history of a pruritic nonbullous eruption who was diagnosed with BP and treated for 3 years based on positive ELISA results in the absence of confirmatory histology or DIF.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and obstructive sleep apnea presented for further evaluation and confirmation of a prior diagnosis of BP by an outside dermatologist. He reported a pruritic rash on the trunk, back, and extremities of 3 years’ duration. He denied occurrence of blisters at any time.

On presentation to an outside dermatologist 3 years ago, a biopsy was performed along with serologic studies due to the patient’s age and the possibility of an urticarial prodrome in BP. The biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, subepidermal separation, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the papillary dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was nondiagnostic with a weak discontinuous pattern of IgG and IgA linearly along the basement membrane zone as well as few scattered and clumped cytoid bodies of IgM and IgA. Indirect immunofluoresence revealed a positive IgG titer of 1:40 on monkey esophagus substrate and a positive epidermal pattern on human split-skin substrate with a titer of 1:80. An ELISA for IgG autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 yielded 15 U and 6 U, respectively (cut off value, 9 U). Based on the positive ELISA for IgG against BP180, a diagnosis of BP was made.

Over the following 3 years, the treatment included prednisone, tetracycline, nicotinamide, doxycycline, and dapsone. Therapy was suboptimal due to the patient’s comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus precluded consistent use of prednisone as recommended for BP. Tetracycline and nicotinamide were transiently effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms but were discontinued due to changes in his health insurance. Doxycycline and dapsone were ineffective. Throughout this 3-year period, the patient remained blister free, but the pruritic eruption was persistent.

The patient presented to our clinic due to his frustration with the lack of improvement and doubts about the BP diagnosis given the persistent absence of bullous lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous eroded, scaly, crusted papules on erythematous edematous plaques on all extremities, trunk, and back (Figure 1). The head, neck, face, and oral mucosa were spared. His history and clinical findings were atypical for BP and skin biopsies were performed. Histology revealed epidermal erosion with parakeratosis, spongiosis, and superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with rare eosinophils without subepidermal split (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Additionally, further review of the initial histology by another dermatopathologist revealed that the subepidermal separation reported was more likely artifactual clefts. These findings were not consistent with BP.

Given the patient’s clinical history, lack of bullae, and twice-negative DIF, the diagnosis was determined to be more consistent with eczematous spongiotic dermatitis. He refused a referral for phototherapy due to scheduling inconvenience. The patient was started on cyclosporine 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. After 10 days of treatment, he returned for follow-up and reported notable improvement in the pruritus. On physical examination, his dermatitis was improved with decreased erythema and inflammation.

The patient is being continued on extensive dry skin care with thick moisturizers and additional topical corticosteroid application on an as-needed basis.

Comment

Chronic immunosuppression contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with BP; therefore, accurate diagnosis of BP is of utmost importance.14 A meta-analysis described ELISA as a test with high sensitivity and specificity (87% and 98%–100%, respectively) for diagnosis of BP.3 Nevertheless, there are opportunities for misdiagnosis using ELISA, as demonstrated in our case. To determine if the reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA is accurate and reliable for clinical use, individual studies from the meta-analysis were reviewed.4,5,7-10,13,15 Issues identified in our review included dissimilar diagnostic procedures and patient populations among individual studies, several reports of positive ELISA in patients without BP, and a lack of explanation for these false-positive results.

There are notable differences in diagnostic procedures and patient populations among reports that establish the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis.3-13 Studies have detected IgG that targets the NC16A domain of the BP180 kD antigen, the C-terminal of the BP180 kD antigen, or the entire ectodomain of the BP180 kD antigen. Study patient populations varied in disease activity, stage, and treatment. Control patients included healthy patients as well as those with many dermatoses, including pemphigus vulgaris, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematosus.3-13 Due to these differences between individual studies, we believe the results that determine the overall sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis must be interpreted with caution. For ELISA statistics to be clinically applicable to a specific patient, he/she should be similar to the patients studied. Therefore, we believe each study must be evaluated individually for applicability, given the differences that exist between them.

Furthermore, there have been several reports of false-positive ELISA results in patients with other dermatologic disorders, specifically in elderly patients with pruritus who do not fulfill clinical criteria for diagnosis with BP.16-18 In a population of elderly patients with pruritus for which no specific dermatological or systemic cause was identified, Hofmann et al18 found that 12% (3/25) of patients showed IgG reactivity to BP180 despite having negative DIF results. In another study of elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses, Feliciani et al17 found that 33% (5/15) of patients had IgG reactivity against BP230 or BP180, though they did not fulfill BP criteria based on clinical presentation and showed negative DIF and IIF results. These findings suggest that IgG reactivity against BP autoantibodies as determined by ELISA is not uncommon in pruritic diseases of the elderly.

Explanations for false-positive ELISA results were rare. A few authors suggested that false-positives could be attributed to an excessively low cutoff value,7-9 which was consistent with reports that the titer of autoantibodies to BP180 correlates with disease severity, suggesting that the higher titer of antibodies correlates with more severe disease and likely more accurate diagnosis.10,19,20 It is important to consider that patients who have low titers of BP180 autoantibodies with inconsistent clinical characteristics and DIF results may not truly have BP. Furthermore, to determine the clinical value of ELISA in identifying patients in the initial phase of BP, sera of BP patients should be compared with sera of elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders because they comprise the patient population that often requires diagnosis.18

Given the issues identified in our review of the literature, the published sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis are likely overstated. In conclusion, ELISA should not be relied on as a single criterion adequate for diagnosis of BP.12,21 Rather, the diagnosis of BP can be obtained with a positive predictive value of 95% when a patient meets 3 of 4 clinical criteria (ie, absence of atrophic scars, absence of head and neck involvement, absence of mucosal involvement, and older than 70 years) and demonstrates linear deposits of predominantly IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone of a perilesional biopsy on DIF.15 The gold standard for diagnosis of BP remains clinical presentation along with DIF, which can be supported by histology, IIF, and ELISA.22

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease. The classic presentation of BP is a generalized, pruritic, bullous eruption in elderly patients, which is occasionally preceded by an urticarial prodrome. Immunopathologically, BP is characterized by IgG and sometimes IgE autoantibodies that target basement membrane zone proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermis.1

The diagnosis of BP should be suspected when an elderly patient presents with tense blisters and can be confirmed via diagnostic testing, including tissue histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as the gold standard, as well as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and most recently biochip technology as supportive tests.2 Since its advent, ELISA has gained popularity as a trustworthy diagnostic test for BP. The specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis is reported to be 98% to 100%, which leads clinicians to believe that a positive ELISA equals certain diagnosis of BP; however, misdiagnosis of BP based on a positive ELISA result can occur.3-13 The treatment of BP often involves lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Complications of immunosuppressive therapy contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients, thus an accurate diagnosis is paramount before introducing therapy.14

We present the case of a 74-year-old man with a history of a pruritic nonbullous eruption who was diagnosed with BP and treated for 3 years based on positive ELISA results in the absence of confirmatory histology or DIF.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and obstructive sleep apnea presented for further evaluation and confirmation of a prior diagnosis of BP by an outside dermatologist. He reported a pruritic rash on the trunk, back, and extremities of 3 years’ duration. He denied occurrence of blisters at any time.

On presentation to an outside dermatologist 3 years ago, a biopsy was performed along with serologic studies due to the patient’s age and the possibility of an urticarial prodrome in BP. The biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, subepidermal separation, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the papillary dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was nondiagnostic with a weak discontinuous pattern of IgG and IgA linearly along the basement membrane zone as well as few scattered and clumped cytoid bodies of IgM and IgA. Indirect immunofluoresence revealed a positive IgG titer of 1:40 on monkey esophagus substrate and a positive epidermal pattern on human split-skin substrate with a titer of 1:80. An ELISA for IgG autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 yielded 15 U and 6 U, respectively (cut off value, 9 U). Based on the positive ELISA for IgG against BP180, a diagnosis of BP was made.

Over the following 3 years, the treatment included prednisone, tetracycline, nicotinamide, doxycycline, and dapsone. Therapy was suboptimal due to the patient’s comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus precluded consistent use of prednisone as recommended for BP. Tetracycline and nicotinamide were transiently effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms but were discontinued due to changes in his health insurance. Doxycycline and dapsone were ineffective. Throughout this 3-year period, the patient remained blister free, but the pruritic eruption was persistent.

The patient presented to our clinic due to his frustration with the lack of improvement and doubts about the BP diagnosis given the persistent absence of bullous lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous eroded, scaly, crusted papules on erythematous edematous plaques on all extremities, trunk, and back (Figure 1). The head, neck, face, and oral mucosa were spared. His history and clinical findings were atypical for BP and skin biopsies were performed. Histology revealed epidermal erosion with parakeratosis, spongiosis, and superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with rare eosinophils without subepidermal split (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Additionally, further review of the initial histology by another dermatopathologist revealed that the subepidermal separation reported was more likely artifactual clefts. These findings were not consistent with BP.

Given the patient’s clinical history, lack of bullae, and twice-negative DIF, the diagnosis was determined to be more consistent with eczematous spongiotic dermatitis. He refused a referral for phototherapy due to scheduling inconvenience. The patient was started on cyclosporine 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. After 10 days of treatment, he returned for follow-up and reported notable improvement in the pruritus. On physical examination, his dermatitis was improved with decreased erythema and inflammation.

The patient is being continued on extensive dry skin care with thick moisturizers and additional topical corticosteroid application on an as-needed basis.

Comment

Chronic immunosuppression contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with BP; therefore, accurate diagnosis of BP is of utmost importance.14 A meta-analysis described ELISA as a test with high sensitivity and specificity (87% and 98%–100%, respectively) for diagnosis of BP.3 Nevertheless, there are opportunities for misdiagnosis using ELISA, as demonstrated in our case. To determine if the reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA is accurate and reliable for clinical use, individual studies from the meta-analysis were reviewed.4,5,7-10,13,15 Issues identified in our review included dissimilar diagnostic procedures and patient populations among individual studies, several reports of positive ELISA in patients without BP, and a lack of explanation for these false-positive results.

There are notable differences in diagnostic procedures and patient populations among reports that establish the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis.3-13 Studies have detected IgG that targets the NC16A domain of the BP180 kD antigen, the C-terminal of the BP180 kD antigen, or the entire ectodomain of the BP180 kD antigen. Study patient populations varied in disease activity, stage, and treatment. Control patients included healthy patients as well as those with many dermatoses, including pemphigus vulgaris, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematosus.3-13 Due to these differences between individual studies, we believe the results that determine the overall sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis must be interpreted with caution. For ELISA statistics to be clinically applicable to a specific patient, he/she should be similar to the patients studied. Therefore, we believe each study must be evaluated individually for applicability, given the differences that exist between them.

Furthermore, there have been several reports of false-positive ELISA results in patients with other dermatologic disorders, specifically in elderly patients with pruritus who do not fulfill clinical criteria for diagnosis with BP.16-18 In a population of elderly patients with pruritus for which no specific dermatological or systemic cause was identified, Hofmann et al18 found that 12% (3/25) of patients showed IgG reactivity to BP180 despite having negative DIF results. In another study of elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses, Feliciani et al17 found that 33% (5/15) of patients had IgG reactivity against BP230 or BP180, though they did not fulfill BP criteria based on clinical presentation and showed negative DIF and IIF results. These findings suggest that IgG reactivity against BP autoantibodies as determined by ELISA is not uncommon in pruritic diseases of the elderly.

Explanations for false-positive ELISA results were rare. A few authors suggested that false-positives could be attributed to an excessively low cutoff value,7-9 which was consistent with reports that the titer of autoantibodies to BP180 correlates with disease severity, suggesting that the higher titer of antibodies correlates with more severe disease and likely more accurate diagnosis.10,19,20 It is important to consider that patients who have low titers of BP180 autoantibodies with inconsistent clinical characteristics and DIF results may not truly have BP. Furthermore, to determine the clinical value of ELISA in identifying patients in the initial phase of BP, sera of BP patients should be compared with sera of elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders because they comprise the patient population that often requires diagnosis.18

Given the issues identified in our review of the literature, the published sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis are likely overstated. In conclusion, ELISA should not be relied on as a single criterion adequate for diagnosis of BP.12,21 Rather, the diagnosis of BP can be obtained with a positive predictive value of 95% when a patient meets 3 of 4 clinical criteria (ie, absence of atrophic scars, absence of head and neck involvement, absence of mucosal involvement, and older than 70 years) and demonstrates linear deposits of predominantly IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone of a perilesional biopsy on DIF.15 The gold standard for diagnosis of BP remains clinical presentation along with DIF, which can be supported by histology, IIF, and ELISA.22

- Delaporte E, Dubost-Brama A, Ghohestani R, et al. IgE autoantibodies directed against the major bullous pemphigoid antigen in patients with a severe form of pemphigoid. J Immunol. 1996;157:3642-3647.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Diagnosis and clinical severity markers of bullous pemphigoid. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:15.

- Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:121-126.

- Zillikens D, Mascaro JM, Rose PA, et al. A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of circulating anti-BP180 autoantibodies in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:679-683.

- Sitaru C, Dahnrich C, Probst C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using multimers of the 16th non-collagenous domain of the BP180 antigen for sensitive and specific detection of pemphigoid autoantibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:770-777.

- Yang B, Wang C, Chen S, et al. Evaluation of the combination of BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:722-727.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Oyama N, et al. Evaluation of a BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:126-131.

- Tampoia M, Lattanzi V, Zucano A, et al. Evaluation of a new ELISA assay for detection of BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:15-20.

- Feng S, Lin L, Jin P, et al. Role of BP180NC16a-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in China. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:24-28.

- Kobayashi M, Amagai M, Kuroda-Kinoshita K, et al. BP180 ELISA using bacterial recombinant NC16a protein as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:224-232.

- Roussel A, Benichou J, Arivelo Randriamanantany Z, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the combination of bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:293-298.

- Chan, Lawrence S. ELISA instead of indirect IF in patients with BP. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:291-292.

- Barnadas MA, Rubiales V, González J, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence testing in a bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1245-1249.

- Borradori L, Bernard P. Pemphigoid group. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:469.

- Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1075-1080.

- Fania L, Caldarola G, Muller R, et al. IgE recognition of bullous pemphigoid (BP)180 and BP230 in BP patients and elderly individuals with pruritic dermatoses. Clin Immunol. 2012;143:236-245.

- Feliciani C, Caldarola G, Kneisel A, et al. IgG autoantibody reactivity against bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and BP230 in elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;61:306-312.

- Hofmann SC, Tamm K, Hertl M, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using BP180 recombinant proteins in elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:910-911.

- Schmidt E, Obe K, Brocker EB, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:174-178.

- Feng S, Wu Q, Jin P, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:225-228.

- Di Zenzo G, Joly P, Zambruno G, et al. Sensitivity of immunofluorescence studies vs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1454-1456.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:84-89.

- Delaporte E, Dubost-Brama A, Ghohestani R, et al. IgE autoantibodies directed against the major bullous pemphigoid antigen in patients with a severe form of pemphigoid. J Immunol. 1996;157:3642-3647.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Diagnosis and clinical severity markers of bullous pemphigoid. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:15.

- Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:121-126.

- Zillikens D, Mascaro JM, Rose PA, et al. A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of circulating anti-BP180 autoantibodies in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:679-683.

- Sitaru C, Dahnrich C, Probst C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using multimers of the 16th non-collagenous domain of the BP180 antigen for sensitive and specific detection of pemphigoid autoantibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:770-777.

- Yang B, Wang C, Chen S, et al. Evaluation of the combination of BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:722-727.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Oyama N, et al. Evaluation of a BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:126-131.

- Tampoia M, Lattanzi V, Zucano A, et al. Evaluation of a new ELISA assay for detection of BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:15-20.

- Feng S, Lin L, Jin P, et al. Role of BP180NC16a-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in China. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:24-28.

- Kobayashi M, Amagai M, Kuroda-Kinoshita K, et al. BP180 ELISA using bacterial recombinant NC16a protein as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:224-232.

- Roussel A, Benichou J, Arivelo Randriamanantany Z, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the combination of bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:293-298.

- Chan, Lawrence S. ELISA instead of indirect IF in patients with BP. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:291-292.

- Barnadas MA, Rubiales V, González J, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence testing in a bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1245-1249.

- Borradori L, Bernard P. Pemphigoid group. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:469.

- Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1075-1080.

- Fania L, Caldarola G, Muller R, et al. IgE recognition of bullous pemphigoid (BP)180 and BP230 in BP patients and elderly individuals with pruritic dermatoses. Clin Immunol. 2012;143:236-245.

- Feliciani C, Caldarola G, Kneisel A, et al. IgG autoantibody reactivity against bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and BP230 in elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;61:306-312.

- Hofmann SC, Tamm K, Hertl M, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using BP180 recombinant proteins in elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:910-911.

- Schmidt E, Obe K, Brocker EB, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:174-178.

- Feng S, Wu Q, Jin P, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:225-228.

- Di Zenzo G, Joly P, Zambruno G, et al. Sensitivity of immunofluorescence studies vs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1454-1456.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:84-89.

Practice Points

- A low serum level of autoantibodies to BP180 should be interpreted with caution because it is more likely to represent a false-positive than a high serum level.

- Rely on the gold standard for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid: clinical presentation along with direct immunofluorescence, which can be supported by histology, indirect immunofluorescence, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) rather than ELISA alone.

Incompatible Type A plasma found safe for initial resuscitation of trauma patients

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Incompatible Type A plasma appears to be a safe and effective part of an initial resuscitation protocol for trauma patients who need a massive transfusion.

There were no increases in morbidity, mortality, or transfusion-related acute lung injury among 120 patients who received Type A plasma, compared with those who got compatible plasma, Bryan C. Morse, MD, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Type AB blood products are preferred for initial transfusions for trauma patients with unknown blood type. While type AB blood products are universally acceptable to patients, they are also in short supply. In an attempt to mitigate this shortage, some trauma centers are relying on anecdotal data, much drawn from real-life combat experience dating from World War II to present times, suggesting that Type A plasma is safe for initial resuscitation protocols. But the body of data from well-constructed trials is small, said Dr. Morse of Emory University, Atlanta. Thus, EAST sponsored this retrospective registry study, which examined outcomes in 1,536 trauma patients who received plasma transfusions as part of a massive transfusion protocol from 2012 to 2016.

The primary endpoints were overall morbidity, and mortality at four time points: 6 and 24 hours, and 7 and 28 days. Eight trauma centers contributed data to the study.

The group was largely male (75%) with a mean age of 37 years. Patients were seriously injured, with a mean Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 25. About 60% suffered from blunt-force trauma. Among the entire group, 120 (8%) received incompatible type A plasma.

About 28% of patients (434) experienced an adverse event. These were numerically but not significantly more common among the incompatible A plasma group (35% vs. 28%; P = .14). Events included acute respiratory distress syndrome (6% vs. 7.6%), thromboembolism (9% vs. 7%), pneumonia (19% vs. 15%), and acute kidney injury (8% each).

There were two cases of transfusion-related acute lung injury, both of which occurred in the compatible type A group.

Mortality was similar at every time point: 6 hours (16% vs. 15%), 24 hours (25% vs. 22%), 7 days (35% vs. 32%), and 28 days (38% vs. 35%).

A multivariate regression model controlled for treatment center, ISS, units of packed red cells given by 4 hours, mechanism of injury, Type A plasma incompatibility, and age.

In the morbidity analysis, only ISS and units of red blood cells at 4 hours were associated with a significant increase in risk (odd ratio 1.02). Incompatible Type A plasma did not significantly increase the risk of morbidity.

In the mortality analysis, units of red cells, ISS, and age were significantly associated with increased risk. Again, incompatible Type A plasma did not significantly increase the risk of death.

Dr. Morse had no financial declaration.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Incompatible Type A plasma appears to be a safe and effective part of an initial resuscitation protocol for trauma patients who need a massive transfusion.

There were no increases in morbidity, mortality, or transfusion-related acute lung injury among 120 patients who received Type A plasma, compared with those who got compatible plasma, Bryan C. Morse, MD, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Type AB blood products are preferred for initial transfusions for trauma patients with unknown blood type. While type AB blood products are universally acceptable to patients, they are also in short supply. In an attempt to mitigate this shortage, some trauma centers are relying on anecdotal data, much drawn from real-life combat experience dating from World War II to present times, suggesting that Type A plasma is safe for initial resuscitation protocols. But the body of data from well-constructed trials is small, said Dr. Morse of Emory University, Atlanta. Thus, EAST sponsored this retrospective registry study, which examined outcomes in 1,536 trauma patients who received plasma transfusions as part of a massive transfusion protocol from 2012 to 2016.

The primary endpoints were overall morbidity, and mortality at four time points: 6 and 24 hours, and 7 and 28 days. Eight trauma centers contributed data to the study.

The group was largely male (75%) with a mean age of 37 years. Patients were seriously injured, with a mean Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 25. About 60% suffered from blunt-force trauma. Among the entire group, 120 (8%) received incompatible type A plasma.

About 28% of patients (434) experienced an adverse event. These were numerically but not significantly more common among the incompatible A plasma group (35% vs. 28%; P = .14). Events included acute respiratory distress syndrome (6% vs. 7.6%), thromboembolism (9% vs. 7%), pneumonia (19% vs. 15%), and acute kidney injury (8% each).

There were two cases of transfusion-related acute lung injury, both of which occurred in the compatible type A group.

Mortality was similar at every time point: 6 hours (16% vs. 15%), 24 hours (25% vs. 22%), 7 days (35% vs. 32%), and 28 days (38% vs. 35%).

A multivariate regression model controlled for treatment center, ISS, units of packed red cells given by 4 hours, mechanism of injury, Type A plasma incompatibility, and age.

In the morbidity analysis, only ISS and units of red blood cells at 4 hours were associated with a significant increase in risk (odd ratio 1.02). Incompatible Type A plasma did not significantly increase the risk of morbidity.

In the mortality analysis, units of red cells, ISS, and age were significantly associated with increased risk. Again, incompatible Type A plasma did not significantly increase the risk of death.

Dr. Morse had no financial declaration.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Incompatible Type A plasma appears to be a safe and effective part of an initial resuscitation protocol for trauma patients who need a massive transfusion.

There were no increases in morbidity, mortality, or transfusion-related acute lung injury among 120 patients who received Type A plasma, compared with those who got compatible plasma, Bryan C. Morse, MD, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Type AB blood products are preferred for initial transfusions for trauma patients with unknown blood type. While type AB blood products are universally acceptable to patients, they are also in short supply. In an attempt to mitigate this shortage, some trauma centers are relying on anecdotal data, much drawn from real-life combat experience dating from World War II to present times, suggesting that Type A plasma is safe for initial resuscitation protocols. But the body of data from well-constructed trials is small, said Dr. Morse of Emory University, Atlanta. Thus, EAST sponsored this retrospective registry study, which examined outcomes in 1,536 trauma patients who received plasma transfusions as part of a massive transfusion protocol from 2012 to 2016.

The primary endpoints were overall morbidity, and mortality at four time points: 6 and 24 hours, and 7 and 28 days. Eight trauma centers contributed data to the study.

The group was largely male (75%) with a mean age of 37 years. Patients were seriously injured, with a mean Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 25. About 60% suffered from blunt-force trauma. Among the entire group, 120 (8%) received incompatible type A plasma.

About 28% of patients (434) experienced an adverse event. These were numerically but not significantly more common among the incompatible A plasma group (35% vs. 28%; P = .14). Events included acute respiratory distress syndrome (6% vs. 7.6%), thromboembolism (9% vs. 7%), pneumonia (19% vs. 15%), and acute kidney injury (8% each).

There were two cases of transfusion-related acute lung injury, both of which occurred in the compatible type A group.

Mortality was similar at every time point: 6 hours (16% vs. 15%), 24 hours (25% vs. 22%), 7 days (35% vs. 32%), and 28 days (38% vs. 35%).

A multivariate regression model controlled for treatment center, ISS, units of packed red cells given by 4 hours, mechanism of injury, Type A plasma incompatibility, and age.

In the morbidity analysis, only ISS and units of red blood cells at 4 hours were associated with a significant increase in risk (odd ratio 1.02). Incompatible Type A plasma did not significantly increase the risk of morbidity.

In the mortality analysis, units of red cells, ISS, and age were significantly associated with increased risk. Again, incompatible Type A plasma did not significantly increase the risk of death.

Dr. Morse had no financial declaration.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Adverse events were not significantly more common among the incompatible A plasma group (35% vs. 28%; P = .14).

Data source: The retrospective study comprised 1,536 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Morse had no financial disclosures.

How to prepare to care for transgender adolescents

As pediatric and adolescent gynecologists, we are seeing an increasing number of adolescents with gender identity issues and have come to believe that all obstetrician-gynecologists need to have an understanding of varying gender identities, as well as their role in managing these patients’ care.

We had the honor to assist the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Committee on Adolescent Health Care in the development of a new Committee Opinion to guide ob.gyns. in caring for transgender adolescents (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e11-6). As our culture grows more aware of the nuances and spectrum of gender identity, our health care practices must grow as well. Ob.gyns. are often uniquely positioned as being among the first people transgender adolescents present to – whether it’s signaling disassociation with their gender when answering routine medical questions or directly addressing gender with them as a trusted and private resource. Even when seeing a patient too young to consider hormone therapy, an ob.gyn. can offer vital early behavioral health support, educational and community resources, and specialist referrals.

Transgender adolescent patients have likely faced negative stereotypes and stigmas in social settings or through media that make them cautious and protective of their identity. They are also more likely to face social ostracism such as bullying and/or dissent and rejection from their parents, deepening the vulnerability of their situation. As a result, transgender adolescents can have increased instances of anxiety, depression, sexual harassment, homelessness, and risk-taking behavior. Medical practices can signal to transgender patients that they are safe and welcoming from the start by offering gender neutral forms, brochures, and information for LGBT patients in the waiting room, and having sensitive employees at every step – from the front desk onward.

As we’ve just outlined, transgender adolescent patients face unique challenges, including increased rates of social and mental health risks. In response, ob.gyns. must be prepared to have a comprehensive conversation about health and well-being beyond sexual and reproductive health. They must also be equipped to address the psychosocial issues associated with transgender adolescents. This includes knowledge of what to look for and offering patients resources, education, and referrals to guarantee their health and safety.

It is important that ob.gyns. are aware that transgender men have female reproductive organs and can present with common gynecological problems such as abnormal bleeding, ovarian cysts, and torsion, as well as pregnancy and pregnancy complications. Finally, ob.gyns. can serve a unique role in counseling about fertility and fertility preservation. Thus, not only do we provide essential health care, including ongoing primary care, but we can position ourselves as part of the support network for these adolescents and their families.

Most importantly, when addressing an adolescent transgender patient, we must understand there is no uniform transgender experience. Expressing gender, sexual identity, and behavior patterns will vary from patient to patient. There are a wide range of treatment options available for transgender patients, from hormone to surgical therapies. An ob.gyn.’s responsibility is to help each individual make an informed decision, and help that patient think ahead to the future.

While this all may seem like a lot, it’s important to remember the essential components of our role as health care providers do not change because an adolescent patient is transgender. Care should always include education about their bodies, safe sex, deliberate and thoughtful assessment of symptoms or concerns, and preventive care services such as STI screenings and contraception. We are simply adding more nuanced cultural and medical understanding to those practices.

Dr. Gomez-Lobo is director of pediatric and adolescent obstetrics and gynecology, Medstar Washington Hospital Center/Children’s National Health System, Washington, D.C. Dr. Sokkary is associate professor of ob.gyn. at Navicent Health Center/Mercer School of Medicine in Macon, Ga. They are members of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

As pediatric and adolescent gynecologists, we are seeing an increasing number of adolescents with gender identity issues and have come to believe that all obstetrician-gynecologists need to have an understanding of varying gender identities, as well as their role in managing these patients’ care.

We had the honor to assist the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Committee on Adolescent Health Care in the development of a new Committee Opinion to guide ob.gyns. in caring for transgender adolescents (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e11-6). As our culture grows more aware of the nuances and spectrum of gender identity, our health care practices must grow as well. Ob.gyns. are often uniquely positioned as being among the first people transgender adolescents present to – whether it’s signaling disassociation with their gender when answering routine medical questions or directly addressing gender with them as a trusted and private resource. Even when seeing a patient too young to consider hormone therapy, an ob.gyn. can offer vital early behavioral health support, educational and community resources, and specialist referrals.

Transgender adolescent patients have likely faced negative stereotypes and stigmas in social settings or through media that make them cautious and protective of their identity. They are also more likely to face social ostracism such as bullying and/or dissent and rejection from their parents, deepening the vulnerability of their situation. As a result, transgender adolescents can have increased instances of anxiety, depression, sexual harassment, homelessness, and risk-taking behavior. Medical practices can signal to transgender patients that they are safe and welcoming from the start by offering gender neutral forms, brochures, and information for LGBT patients in the waiting room, and having sensitive employees at every step – from the front desk onward.

As we’ve just outlined, transgender adolescent patients face unique challenges, including increased rates of social and mental health risks. In response, ob.gyns. must be prepared to have a comprehensive conversation about health and well-being beyond sexual and reproductive health. They must also be equipped to address the psychosocial issues associated with transgender adolescents. This includes knowledge of what to look for and offering patients resources, education, and referrals to guarantee their health and safety.

It is important that ob.gyns. are aware that transgender men have female reproductive organs and can present with common gynecological problems such as abnormal bleeding, ovarian cysts, and torsion, as well as pregnancy and pregnancy complications. Finally, ob.gyns. can serve a unique role in counseling about fertility and fertility preservation. Thus, not only do we provide essential health care, including ongoing primary care, but we can position ourselves as part of the support network for these adolescents and their families.

Most importantly, when addressing an adolescent transgender patient, we must understand there is no uniform transgender experience. Expressing gender, sexual identity, and behavior patterns will vary from patient to patient. There are a wide range of treatment options available for transgender patients, from hormone to surgical therapies. An ob.gyn.’s responsibility is to help each individual make an informed decision, and help that patient think ahead to the future.

While this all may seem like a lot, it’s important to remember the essential components of our role as health care providers do not change because an adolescent patient is transgender. Care should always include education about their bodies, safe sex, deliberate and thoughtful assessment of symptoms or concerns, and preventive care services such as STI screenings and contraception. We are simply adding more nuanced cultural and medical understanding to those practices.