User login

But you told me...

“The other doctor I went to told me that the spot he biopsied on my nose was a skin cancer,” Larry said. “But he told me just to keep an eye on it.”

I always try not to roll my eyes when a patient quotes another doctor, especially if the quote doesn’t make much sense. In the first place, it’s bad form to act like you’re smarter than somebody else. In the second place, you probably aren’t.

In the third place, what the patient says the doctor said may not be what the doctor actually said. I have many chances to learn this firsthand, such as when patients quote me incorrectly to myself.

No, I didn’t.

I point out to students that, to patients, calling a mole benign is always provisional. They’re happy that it’s benign today. Tomorrow, who knows?

That’s why when I reassure people about moles I’m not worried about, I say, “It’s benign... and it will always be benign.” When they look startled – as they often do – I elaborate: “Because if I thought it could turn into skin cancer, I would have to remove it right now.” Then they nod, somewhat tentatively. What I just said clearly made sense, only it contradicts what they always assumed was true, which is that you should always keep an eye on things.

Since I thought Steve’s mole was benign, I did not tell him that we need to keep an eye on it, any more than Larry’s previous doctor had told him just to keep an eye on a biopsy-proved skin cancer. Steve just thought that’s what I must have said, because that’s what makes sense to him.

Then there was Amanda, who had stopped her acne gel weeks before. “It was making me worse,” she explained, “and you told me to stop the medicine if anything happened.”

Nope, not even close.

What I did say – what I always say – was this: “These are the reactions you might experience. If you think you’re getting them or any others, call me right away, so I can consider changing to something different.” I never tell patients to just stop treatment and not tell anyone. Who would?

The opposite happens too. Just as some people stop medication without telling their doctors, others find it just as hard to stop treatment even when they’re instructed to.

“When your seborrhea quiets down,” I say, “you can stop the cream. Resume it when you need to, but stop again as soon as you clear up.”

Easy for me to say. But in walks Phillip. He’s been using applying desonide daily for 6 years. “You said I should keep using it,” he explains.

No, I didn’t. “What I was trying to say,” I politely explain, “is that when your skin feels fine, it’s OK to stop. They you can use it again when the rash comes back. Keeping up applying the cream doesn’t stop the rash from coming back if it’s going to.”

Philip nods. I think he understands. But I thought so last time too, didn’t I?

I should also give a shout-out to the patients who say, “I’ve been using the clotrimazole-betamethasone cream you prescribed...”

No, I did not prescribe clotrimazole-betamethasone! I would lose my membership in the dermatologists’ union.

Researchers who study cross-cultural practice look into issues of miscommunication between providers and consumers who come from distant cultures, where basic notions get in the way of each party’s understanding the other. No one seems that interested in studying all the miscommunication that goes on between educated native-English speakers, in medical offices no less than in the halls of the legislature.

I got hold of Larry’s biopsy report, by the way. It was read out as “actinic keratosis,” which is why Larry’s former doctor had told him that they would just watch it.

I called Larry. “It was not an actual cancer,” I told him. “Just precancerous. Come back in 6 months. We’ll keep an eye on it.”

That was clear. I think.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient” is now available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

“The other doctor I went to told me that the spot he biopsied on my nose was a skin cancer,” Larry said. “But he told me just to keep an eye on it.”

I always try not to roll my eyes when a patient quotes another doctor, especially if the quote doesn’t make much sense. In the first place, it’s bad form to act like you’re smarter than somebody else. In the second place, you probably aren’t.

In the third place, what the patient says the doctor said may not be what the doctor actually said. I have many chances to learn this firsthand, such as when patients quote me incorrectly to myself.

No, I didn’t.

I point out to students that, to patients, calling a mole benign is always provisional. They’re happy that it’s benign today. Tomorrow, who knows?

That’s why when I reassure people about moles I’m not worried about, I say, “It’s benign... and it will always be benign.” When they look startled – as they often do – I elaborate: “Because if I thought it could turn into skin cancer, I would have to remove it right now.” Then they nod, somewhat tentatively. What I just said clearly made sense, only it contradicts what they always assumed was true, which is that you should always keep an eye on things.

Since I thought Steve’s mole was benign, I did not tell him that we need to keep an eye on it, any more than Larry’s previous doctor had told him just to keep an eye on a biopsy-proved skin cancer. Steve just thought that’s what I must have said, because that’s what makes sense to him.

Then there was Amanda, who had stopped her acne gel weeks before. “It was making me worse,” she explained, “and you told me to stop the medicine if anything happened.”

Nope, not even close.

What I did say – what I always say – was this: “These are the reactions you might experience. If you think you’re getting them or any others, call me right away, so I can consider changing to something different.” I never tell patients to just stop treatment and not tell anyone. Who would?

The opposite happens too. Just as some people stop medication without telling their doctors, others find it just as hard to stop treatment even when they’re instructed to.

“When your seborrhea quiets down,” I say, “you can stop the cream. Resume it when you need to, but stop again as soon as you clear up.”

Easy for me to say. But in walks Phillip. He’s been using applying desonide daily for 6 years. “You said I should keep using it,” he explains.

No, I didn’t. “What I was trying to say,” I politely explain, “is that when your skin feels fine, it’s OK to stop. They you can use it again when the rash comes back. Keeping up applying the cream doesn’t stop the rash from coming back if it’s going to.”

Philip nods. I think he understands. But I thought so last time too, didn’t I?

I should also give a shout-out to the patients who say, “I’ve been using the clotrimazole-betamethasone cream you prescribed...”

No, I did not prescribe clotrimazole-betamethasone! I would lose my membership in the dermatologists’ union.

Researchers who study cross-cultural practice look into issues of miscommunication between providers and consumers who come from distant cultures, where basic notions get in the way of each party’s understanding the other. No one seems that interested in studying all the miscommunication that goes on between educated native-English speakers, in medical offices no less than in the halls of the legislature.

I got hold of Larry’s biopsy report, by the way. It was read out as “actinic keratosis,” which is why Larry’s former doctor had told him that they would just watch it.

I called Larry. “It was not an actual cancer,” I told him. “Just precancerous. Come back in 6 months. We’ll keep an eye on it.”

That was clear. I think.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient” is now available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

“The other doctor I went to told me that the spot he biopsied on my nose was a skin cancer,” Larry said. “But he told me just to keep an eye on it.”

I always try not to roll my eyes when a patient quotes another doctor, especially if the quote doesn’t make much sense. In the first place, it’s bad form to act like you’re smarter than somebody else. In the second place, you probably aren’t.

In the third place, what the patient says the doctor said may not be what the doctor actually said. I have many chances to learn this firsthand, such as when patients quote me incorrectly to myself.

No, I didn’t.

I point out to students that, to patients, calling a mole benign is always provisional. They’re happy that it’s benign today. Tomorrow, who knows?

That’s why when I reassure people about moles I’m not worried about, I say, “It’s benign... and it will always be benign.” When they look startled – as they often do – I elaborate: “Because if I thought it could turn into skin cancer, I would have to remove it right now.” Then they nod, somewhat tentatively. What I just said clearly made sense, only it contradicts what they always assumed was true, which is that you should always keep an eye on things.

Since I thought Steve’s mole was benign, I did not tell him that we need to keep an eye on it, any more than Larry’s previous doctor had told him just to keep an eye on a biopsy-proved skin cancer. Steve just thought that’s what I must have said, because that’s what makes sense to him.

Then there was Amanda, who had stopped her acne gel weeks before. “It was making me worse,” she explained, “and you told me to stop the medicine if anything happened.”

Nope, not even close.

What I did say – what I always say – was this: “These are the reactions you might experience. If you think you’re getting them or any others, call me right away, so I can consider changing to something different.” I never tell patients to just stop treatment and not tell anyone. Who would?

The opposite happens too. Just as some people stop medication without telling their doctors, others find it just as hard to stop treatment even when they’re instructed to.

“When your seborrhea quiets down,” I say, “you can stop the cream. Resume it when you need to, but stop again as soon as you clear up.”

Easy for me to say. But in walks Phillip. He’s been using applying desonide daily for 6 years. “You said I should keep using it,” he explains.

No, I didn’t. “What I was trying to say,” I politely explain, “is that when your skin feels fine, it’s OK to stop. They you can use it again when the rash comes back. Keeping up applying the cream doesn’t stop the rash from coming back if it’s going to.”

Philip nods. I think he understands. But I thought so last time too, didn’t I?

I should also give a shout-out to the patients who say, “I’ve been using the clotrimazole-betamethasone cream you prescribed...”

No, I did not prescribe clotrimazole-betamethasone! I would lose my membership in the dermatologists’ union.

Researchers who study cross-cultural practice look into issues of miscommunication between providers and consumers who come from distant cultures, where basic notions get in the way of each party’s understanding the other. No one seems that interested in studying all the miscommunication that goes on between educated native-English speakers, in medical offices no less than in the halls of the legislature.

I got hold of Larry’s biopsy report, by the way. It was read out as “actinic keratosis,” which is why Larry’s former doctor had told him that they would just watch it.

I called Larry. “It was not an actual cancer,” I told him. “Just precancerous. Come back in 6 months. We’ll keep an eye on it.”

That was clear. I think.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient” is now available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Ramucirumab benefits gastric cancer patients across age groups

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma benefit from treatment with ramucirumab regardless of their age, according to findings from an exploratory subgroup analysis of the phase III RAINBOW and REGARD studies.

The findings, which show at least a trend toward improvements in most age categories, are important given that nearly two-thirds of patients with these cancers are diagnosed at over age 65 years, and more than half of those are over age 75 years, Kei Muro, MD, reported at the symposium sponsored by ASCO, ASTRO, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

“At the other end of the age spectrum, there is evidence that young age can also be an unfavorable prognostic characteristic for gastric cancer,” said Dr. Muro of Aichi Cancer Center Hospital in Nagoya, Japan.

Both RAINBOW and REGARD demonstrated statistically significant and clinically meaningful overall and progression-free survival benefits and acceptable and manageable toxicity with ramucirumab among patients with advanced gastric cancer who were randomized, in the second-line treatment setting, to receive active treatment with the fully humanized monoclonal antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor–2 or placebo.

RAINBOW subjects were randomized 1:1 to receive 8 mg/kg of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel, or placebo plus paclitaxel. Among those aged 45 years or less (37 patients in each group), the median overall survival was 9.0 months for treatment vs. 4.2 months for placebo (hazard ratio, 0.555), and the median progression-free survival was 3.9 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.299).

The corresponding median overall survival rates for those aged 45-70 (225 and 230 patients in the groups, respectively), 70 or older (68 patients in each group), and 75 or older (20 and 16 patients in the groups, respectively) were 9.6 vs. 7.6 months (HR, 0.860), 10.8 vs. 8.6 months (HR, 0.881), and 11.0 vs. 11.0 months (HR, 0.971). The corresponding progression-free survival rates for those aged 45-70, 70 or older, and 75 or older were 4.6 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.649), 4.7 vs. 2.9 months (HR, 0.676), and 4.2 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.330).

REGARD subjects were randomized 2:1 to receive 8 mg/kg of ramucirumab plus best supportive care, or placebo plus best supportive care. Among those aged 45 years or less (37 patients in each group), the median overall survival was 9.0 vs. 4.2 months for treatment vs. placebo (HR, 0.555), and the median progression-free survival was 3.9 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.299).

Among REGARD subjects aged 45 years or less (28 and 12 patients in the groups, respectively), the median overall survival was 5.8 vs. 2.9 months for treatment vs. placebo (HR, 0.586), and the median progression-free survival was 1.9 vs. 1.4 months (HR, 0.270).

The corresponding median overall survival rates for those aged 45-70 (166 and 70 patients in the groups, respectively), 70 or older (44 and 35 patients in the groups, respectively), and 75 or older (21 and 13 patients in the groups, respectively) were 4.9 vs. 4.1 months (HR, 0.780), 5.9 vs. 3.8 months (HR, 0.730), and 9.3 vs. 5.1 months (HR, 0.588).

The corresponding progression-free survival rates for those aged 45-70, 70 or older, and 75 or older were 2.2 vs. 1.3 months (HR, 0.451), 2.1 vs. 1.4 months (HR, 0.559), 2.8 vs. 1.4 (HR, 0.420).

Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between arms in each of the age subgroups, Dr. Muro said, noting that no obvious patterns for differential risks in terms of efficacy and adverse events of any grade or of grade 3 or greater were seen according to age. Discontinuation rates for adverse events were similar across different age groups, and quality of life, as determined by global health status, was satisfactory in all age groups.

“Despite some limitations regarding patient numbers in some age subgroups, this exploratory subgroup analysis supports the use of ramucirumab for the treatment of our patients with gastric cancer irrespective of age,” he concluded.

RAINBOW was funded by Eli Lilly. REGARD was funded by ImClone Systems. Dr. Muro reported receiving honoraria from Chugai Pharma, Merck Serono, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Eli Lilly, and Yakult Honsha, as well as serving in a consulting or an advisory role for Ono, Merck Serono, and Eli Lilly, and receiving research funding from MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, Eisai, Pfizer, Chugai, Dainippon Sumitomo, Merck Serono, Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin.

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma benefit from treatment with ramucirumab regardless of their age, according to findings from an exploratory subgroup analysis of the phase III RAINBOW and REGARD studies.

The findings, which show at least a trend toward improvements in most age categories, are important given that nearly two-thirds of patients with these cancers are diagnosed at over age 65 years, and more than half of those are over age 75 years, Kei Muro, MD, reported at the symposium sponsored by ASCO, ASTRO, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

“At the other end of the age spectrum, there is evidence that young age can also be an unfavorable prognostic characteristic for gastric cancer,” said Dr. Muro of Aichi Cancer Center Hospital in Nagoya, Japan.

Both RAINBOW and REGARD demonstrated statistically significant and clinically meaningful overall and progression-free survival benefits and acceptable and manageable toxicity with ramucirumab among patients with advanced gastric cancer who were randomized, in the second-line treatment setting, to receive active treatment with the fully humanized monoclonal antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor–2 or placebo.

RAINBOW subjects were randomized 1:1 to receive 8 mg/kg of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel, or placebo plus paclitaxel. Among those aged 45 years or less (37 patients in each group), the median overall survival was 9.0 months for treatment vs. 4.2 months for placebo (hazard ratio, 0.555), and the median progression-free survival was 3.9 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.299).

The corresponding median overall survival rates for those aged 45-70 (225 and 230 patients in the groups, respectively), 70 or older (68 patients in each group), and 75 or older (20 and 16 patients in the groups, respectively) were 9.6 vs. 7.6 months (HR, 0.860), 10.8 vs. 8.6 months (HR, 0.881), and 11.0 vs. 11.0 months (HR, 0.971). The corresponding progression-free survival rates for those aged 45-70, 70 or older, and 75 or older were 4.6 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.649), 4.7 vs. 2.9 months (HR, 0.676), and 4.2 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.330).

REGARD subjects were randomized 2:1 to receive 8 mg/kg of ramucirumab plus best supportive care, or placebo plus best supportive care. Among those aged 45 years or less (37 patients in each group), the median overall survival was 9.0 vs. 4.2 months for treatment vs. placebo (HR, 0.555), and the median progression-free survival was 3.9 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.299).

Among REGARD subjects aged 45 years or less (28 and 12 patients in the groups, respectively), the median overall survival was 5.8 vs. 2.9 months for treatment vs. placebo (HR, 0.586), and the median progression-free survival was 1.9 vs. 1.4 months (HR, 0.270).

The corresponding median overall survival rates for those aged 45-70 (166 and 70 patients in the groups, respectively), 70 or older (44 and 35 patients in the groups, respectively), and 75 or older (21 and 13 patients in the groups, respectively) were 4.9 vs. 4.1 months (HR, 0.780), 5.9 vs. 3.8 months (HR, 0.730), and 9.3 vs. 5.1 months (HR, 0.588).

The corresponding progression-free survival rates for those aged 45-70, 70 or older, and 75 or older were 2.2 vs. 1.3 months (HR, 0.451), 2.1 vs. 1.4 months (HR, 0.559), 2.8 vs. 1.4 (HR, 0.420).

Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between arms in each of the age subgroups, Dr. Muro said, noting that no obvious patterns for differential risks in terms of efficacy and adverse events of any grade or of grade 3 or greater were seen according to age. Discontinuation rates for adverse events were similar across different age groups, and quality of life, as determined by global health status, was satisfactory in all age groups.

“Despite some limitations regarding patient numbers in some age subgroups, this exploratory subgroup analysis supports the use of ramucirumab for the treatment of our patients with gastric cancer irrespective of age,” he concluded.

RAINBOW was funded by Eli Lilly. REGARD was funded by ImClone Systems. Dr. Muro reported receiving honoraria from Chugai Pharma, Merck Serono, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Eli Lilly, and Yakult Honsha, as well as serving in a consulting or an advisory role for Ono, Merck Serono, and Eli Lilly, and receiving research funding from MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, Eisai, Pfizer, Chugai, Dainippon Sumitomo, Merck Serono, Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin.

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma benefit from treatment with ramucirumab regardless of their age, according to findings from an exploratory subgroup analysis of the phase III RAINBOW and REGARD studies.

The findings, which show at least a trend toward improvements in most age categories, are important given that nearly two-thirds of patients with these cancers are diagnosed at over age 65 years, and more than half of those are over age 75 years, Kei Muro, MD, reported at the symposium sponsored by ASCO, ASTRO, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

“At the other end of the age spectrum, there is evidence that young age can also be an unfavorable prognostic characteristic for gastric cancer,” said Dr. Muro of Aichi Cancer Center Hospital in Nagoya, Japan.

Both RAINBOW and REGARD demonstrated statistically significant and clinically meaningful overall and progression-free survival benefits and acceptable and manageable toxicity with ramucirumab among patients with advanced gastric cancer who were randomized, in the second-line treatment setting, to receive active treatment with the fully humanized monoclonal antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor–2 or placebo.

RAINBOW subjects were randomized 1:1 to receive 8 mg/kg of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel, or placebo plus paclitaxel. Among those aged 45 years or less (37 patients in each group), the median overall survival was 9.0 months for treatment vs. 4.2 months for placebo (hazard ratio, 0.555), and the median progression-free survival was 3.9 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.299).

The corresponding median overall survival rates for those aged 45-70 (225 and 230 patients in the groups, respectively), 70 or older (68 patients in each group), and 75 or older (20 and 16 patients in the groups, respectively) were 9.6 vs. 7.6 months (HR, 0.860), 10.8 vs. 8.6 months (HR, 0.881), and 11.0 vs. 11.0 months (HR, 0.971). The corresponding progression-free survival rates for those aged 45-70, 70 or older, and 75 or older were 4.6 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.649), 4.7 vs. 2.9 months (HR, 0.676), and 4.2 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.330).

REGARD subjects were randomized 2:1 to receive 8 mg/kg of ramucirumab plus best supportive care, or placebo plus best supportive care. Among those aged 45 years or less (37 patients in each group), the median overall survival was 9.0 vs. 4.2 months for treatment vs. placebo (HR, 0.555), and the median progression-free survival was 3.9 vs. 2.8 months (HR, 0.299).

Among REGARD subjects aged 45 years or less (28 and 12 patients in the groups, respectively), the median overall survival was 5.8 vs. 2.9 months for treatment vs. placebo (HR, 0.586), and the median progression-free survival was 1.9 vs. 1.4 months (HR, 0.270).

The corresponding median overall survival rates for those aged 45-70 (166 and 70 patients in the groups, respectively), 70 or older (44 and 35 patients in the groups, respectively), and 75 or older (21 and 13 patients in the groups, respectively) were 4.9 vs. 4.1 months (HR, 0.780), 5.9 vs. 3.8 months (HR, 0.730), and 9.3 vs. 5.1 months (HR, 0.588).

The corresponding progression-free survival rates for those aged 45-70, 70 or older, and 75 or older were 2.2 vs. 1.3 months (HR, 0.451), 2.1 vs. 1.4 months (HR, 0.559), 2.8 vs. 1.4 (HR, 0.420).

Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between arms in each of the age subgroups, Dr. Muro said, noting that no obvious patterns for differential risks in terms of efficacy and adverse events of any grade or of grade 3 or greater were seen according to age. Discontinuation rates for adverse events were similar across different age groups, and quality of life, as determined by global health status, was satisfactory in all age groups.

“Despite some limitations regarding patient numbers in some age subgroups, this exploratory subgroup analysis supports the use of ramucirumab for the treatment of our patients with gastric cancer irrespective of age,” he concluded.

RAINBOW was funded by Eli Lilly. REGARD was funded by ImClone Systems. Dr. Muro reported receiving honoraria from Chugai Pharma, Merck Serono, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Eli Lilly, and Yakult Honsha, as well as serving in a consulting or an advisory role for Ono, Merck Serono, and Eli Lilly, and receiving research funding from MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, Eisai, Pfizer, Chugai, Dainippon Sumitomo, Merck Serono, Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin.

AT THE 2017 GASTROINTESTINAL CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients 45-70 years and 70 and older, the hazard ratios for overall survival were 0.860 and 0.881 with ramucirumab vs. placebo in RAINBOW, and 0.780 and 0.730 in REGARD

Data source: The phase III RAINBOW and REGARD trials, including a total of more than 1,000 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Muro reported receiving honoraria from Chugai Pharma, Merck Serono, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Eli Lilly, and Yakult Honsha, as well as serving in a consulting or an advisory role for Ono, Merck Serono, and Eli Lilly, and receiving research funding from MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, Eisai, Pfizer, Chugai, Dainippon Sumitomo, Merck Serono, Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin.

Complex congenital heart conditions call for complex care in pregnancy

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) brings together recommendations for management of pregnancy for women with serious congenital heart disease. The 38-page document addresses a wide range of complex congenital heart conditions, presenting a newly unified set of recommendations for care that ranges from preconception counseling, through pregnancy, labor, and delivery, to the postpartum period.

Caring for women with complex congenital heart lesions is becoming more commonplace, as more infants undergo successful repairs of previously-unsurvivable cardiac anomalies. “More moms with congenital heart disease are showing up pregnant, having survived the tumultuous peripartum and neonatal period, and are now facing a new set of risks in pregnancy,” Michael Foley, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview.

Joseph Kay, MD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, said that one big benefit of the new scientific statement is having a single reference point for care of these patients. “The scientific statement brings all of the information about caring for these patients together into one document. This will be a very valuable resource for trainees to get a sense of what’s important; it also represents a platform for new programs to understand the scope of services needed,” said Dr. Kay in an interview.

The document provides a thorough review of the physiologic changes of pregnancy and the intrapartum and postpartum periods, noting that the heterogeneity of congenital heart disease means that women who have different lesions carry different risks in pregnancy.

Examples of lesions presenting intermediate risk include most arrhythmias (category II), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and a repaired coarctation (both category II-III). The most severe lesions carry a contraindication for pregnancy; the WHO guidelines suggest discussing termination should women with a category IV lesion become pregnant. Severe mitral stenosis, severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, and severe systemic ventricular dysfunction all place women into category IV.

Beginning with pregnancy risk category III, the WHO guidelines recommend intensive cardiac and obstetric monitoring throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium. Several maternal-fetal medicine specialists interviewed all agreed that an interdisciplinary team is a must for good obstetric care in this population.

How interdisciplinary care plays out can depend on geography and facility-dependent resources. Dr. Kay said that his facility is the referral site for pregnant women with complex congenital lesions in an area that spans the Canadian and the Mexican borders from north to south, and ranges from parts of Kansas to eastern Montana from east to west. Still, Dr. Kay said that even for patients with lower-risk lesions, “We will see patients at least once, at approximately the midpoint of pregnancy, and again during the third trimester if possible.” The specifics of care depend on “the nature of the lesion and the complexity of the disease,” said Dr. Kay.

In his facility, said Dr. Kay, telemetry is available for all of the labor and delivery unit beds. This means that the mother and infant can usually stay together and receive postpartum nursing and lactation care from a skilled staff.

In no circumstances should ob.gyns. go it alone, said Dr. Foley. “The conversation with the ob.gyn. needs to be about comanaging these patients, at the very least. Even the most learned maternal-fetal medicine specialist needs to be working with a cardiologist and an anesthesiologist to create a delivery plan that includes pain management, fluid management, and consideration for intrapartum hemodynamic monitoring,” he said.

And the team needs to be in place long before delivery, Dr. Foley pointed out. “In many hospitals, the care delivery gap may be the inability to have this consistent proactive approach. You can’t expect the best outcomes when you have to hurriedly assemble an unfamiliar ad hoc team when a woman with congenital heart disease presents in labor. Despite their best intentions, inconsistent team members may not have the knowledge and experience to provide the safest care for these patients,” he said.

Though an individualized labor and delivery plan is a must, and a multispecialty team should be assembled, maternal congenital heart disease doesn’t necessarily consign a woman to cesarean delivery. “Most women can and should have a vaginal delivery. It’s safer for them. If a natural delivery may increase risk of issues, we may consider a facilitated second stage of labor with epidural anesthesia and forceps- or vacuum-assisted delivery,” said Dr. Kay.

It’s important to understand the nuances of an individual patient’s health and risk status, said Dr. Norton. “A simplified view is often bad. It’s not the case that ‘it’s always better to deliver’ or ‘it’s always better to have a cesarean delivery.’”

Especially for women who need anticoagulation or who may have lesions that put them at great risk should pregnancy occur, preconception counseling is a vital part of their care, and guidance in the scientific statement can help specialists avoid the complications that can occur in the absence of evidence-based treatment. Said Dr. Kay, “I have seen an unfortunate case or two of patients whose anticoagulation was stopped or changed, contrary to guidelines, and who suffered strokes. I hope more people will see this document.”

Ms. Canobbio echoed the sentiment: “You don’t want to have to backpedal once a young woman presents with a pregnancy. Appropriate contraceptive counseling needs to be part of the conversation.”

One key concept underscored in the scientific statement is that elevated risk persists into the postpartum period. “Following delivery, the mother is still at risk for an extended period of time. The greatest risk for mortality in these patients is post delivery, when a large volume of blood is expelled from the uterus back into the maternal circulation,” said Ms. Canobbio. “These women need close follow-up; we can’t say they are home free until several weeks to 2 months after delivery. The need for vigilance and surveillance continues.”

Since the scientific statement is not a new set of guidelines, but rather a compilation of currently existing reference documents, the authors noted that management differences may exist in some cases, but did not assign greater value to one practice than another. “We addressed that there are differences between the European and the American guidelines. For example, with regard to anticoagulation, both would agree to use Lovenox [enoxaparin], but the difference is whether it should be used for the entire pregnancy or for parts of the pregnancy,” said Ms. Canobbio.

Looking forward, more women with complex congenital heart disease will bear children, but their future is not certain. Said Ms. Canobbio: “The data are growing that if the patient is clinically stable at the time of pregnancy, it’s likely we can get them through safely. What’s not yet known is whether the burden of pregnancy in a woman who is otherwise healthy will shorten her lifespan. However, early data are promising, and it’s looking like these women can fare well.”

Topics covered in the scientific statement include:

- Defining which patients are at increased risk in pregnancy.

- Physiological adaptations of pregnancy, the puerperium, and the postpartum period, with an emphasis on hemodynamic changes.

- Assessment and evaluation in the preconception and early prenatal periods.

- Pregnancy management, including appropriate testing.

- Medications in pregnancy, including a table of common cardiac drugs and their pregnancy categories and lactation risks.

- Breakdown of suggested prenatal care by trimester.

- Intrapartum care, including indications for fluid management, ECG and hemodynamic monitoring, and management of the second stage of delivery.

- Postpartum care, with attention to the very rapid increase in blood volume and concomitant leap in stroke volume and cardiac output.

- Considerations when choosing contraceptive method.

- Cardiac complications seen in pregnancy, including arrhythmias, managing mechanical valves and anticoagulation, heart failure, and cyanosis.

- Indications for and risks associated with interventional therapies during pregnancy.

- Detailed discussion of management of pregnancy for women with specific lesions.

None of the members of the writing committee for the scientific statement had relevant disclosures. Dr. Foley and Dr. Kay reported no disclosures. Dr. Norton reported that she has received research funding from Natera and Ultragenyx.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) brings together recommendations for management of pregnancy for women with serious congenital heart disease. The 38-page document addresses a wide range of complex congenital heart conditions, presenting a newly unified set of recommendations for care that ranges from preconception counseling, through pregnancy, labor, and delivery, to the postpartum period.

Caring for women with complex congenital heart lesions is becoming more commonplace, as more infants undergo successful repairs of previously-unsurvivable cardiac anomalies. “More moms with congenital heart disease are showing up pregnant, having survived the tumultuous peripartum and neonatal period, and are now facing a new set of risks in pregnancy,” Michael Foley, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview.

Joseph Kay, MD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, said that one big benefit of the new scientific statement is having a single reference point for care of these patients. “The scientific statement brings all of the information about caring for these patients together into one document. This will be a very valuable resource for trainees to get a sense of what’s important; it also represents a platform for new programs to understand the scope of services needed,” said Dr. Kay in an interview.

The document provides a thorough review of the physiologic changes of pregnancy and the intrapartum and postpartum periods, noting that the heterogeneity of congenital heart disease means that women who have different lesions carry different risks in pregnancy.

Examples of lesions presenting intermediate risk include most arrhythmias (category II), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and a repaired coarctation (both category II-III). The most severe lesions carry a contraindication for pregnancy; the WHO guidelines suggest discussing termination should women with a category IV lesion become pregnant. Severe mitral stenosis, severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, and severe systemic ventricular dysfunction all place women into category IV.

Beginning with pregnancy risk category III, the WHO guidelines recommend intensive cardiac and obstetric monitoring throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium. Several maternal-fetal medicine specialists interviewed all agreed that an interdisciplinary team is a must for good obstetric care in this population.

How interdisciplinary care plays out can depend on geography and facility-dependent resources. Dr. Kay said that his facility is the referral site for pregnant women with complex congenital lesions in an area that spans the Canadian and the Mexican borders from north to south, and ranges from parts of Kansas to eastern Montana from east to west. Still, Dr. Kay said that even for patients with lower-risk lesions, “We will see patients at least once, at approximately the midpoint of pregnancy, and again during the third trimester if possible.” The specifics of care depend on “the nature of the lesion and the complexity of the disease,” said Dr. Kay.

In his facility, said Dr. Kay, telemetry is available for all of the labor and delivery unit beds. This means that the mother and infant can usually stay together and receive postpartum nursing and lactation care from a skilled staff.

In no circumstances should ob.gyns. go it alone, said Dr. Foley. “The conversation with the ob.gyn. needs to be about comanaging these patients, at the very least. Even the most learned maternal-fetal medicine specialist needs to be working with a cardiologist and an anesthesiologist to create a delivery plan that includes pain management, fluid management, and consideration for intrapartum hemodynamic monitoring,” he said.

And the team needs to be in place long before delivery, Dr. Foley pointed out. “In many hospitals, the care delivery gap may be the inability to have this consistent proactive approach. You can’t expect the best outcomes when you have to hurriedly assemble an unfamiliar ad hoc team when a woman with congenital heart disease presents in labor. Despite their best intentions, inconsistent team members may not have the knowledge and experience to provide the safest care for these patients,” he said.

Though an individualized labor and delivery plan is a must, and a multispecialty team should be assembled, maternal congenital heart disease doesn’t necessarily consign a woman to cesarean delivery. “Most women can and should have a vaginal delivery. It’s safer for them. If a natural delivery may increase risk of issues, we may consider a facilitated second stage of labor with epidural anesthesia and forceps- or vacuum-assisted delivery,” said Dr. Kay.

It’s important to understand the nuances of an individual patient’s health and risk status, said Dr. Norton. “A simplified view is often bad. It’s not the case that ‘it’s always better to deliver’ or ‘it’s always better to have a cesarean delivery.’”

Especially for women who need anticoagulation or who may have lesions that put them at great risk should pregnancy occur, preconception counseling is a vital part of their care, and guidance in the scientific statement can help specialists avoid the complications that can occur in the absence of evidence-based treatment. Said Dr. Kay, “I have seen an unfortunate case or two of patients whose anticoagulation was stopped or changed, contrary to guidelines, and who suffered strokes. I hope more people will see this document.”

Ms. Canobbio echoed the sentiment: “You don’t want to have to backpedal once a young woman presents with a pregnancy. Appropriate contraceptive counseling needs to be part of the conversation.”

One key concept underscored in the scientific statement is that elevated risk persists into the postpartum period. “Following delivery, the mother is still at risk for an extended period of time. The greatest risk for mortality in these patients is post delivery, when a large volume of blood is expelled from the uterus back into the maternal circulation,” said Ms. Canobbio. “These women need close follow-up; we can’t say they are home free until several weeks to 2 months after delivery. The need for vigilance and surveillance continues.”

Since the scientific statement is not a new set of guidelines, but rather a compilation of currently existing reference documents, the authors noted that management differences may exist in some cases, but did not assign greater value to one practice than another. “We addressed that there are differences between the European and the American guidelines. For example, with regard to anticoagulation, both would agree to use Lovenox [enoxaparin], but the difference is whether it should be used for the entire pregnancy or for parts of the pregnancy,” said Ms. Canobbio.

Looking forward, more women with complex congenital heart disease will bear children, but their future is not certain. Said Ms. Canobbio: “The data are growing that if the patient is clinically stable at the time of pregnancy, it’s likely we can get them through safely. What’s not yet known is whether the burden of pregnancy in a woman who is otherwise healthy will shorten her lifespan. However, early data are promising, and it’s looking like these women can fare well.”

Topics covered in the scientific statement include:

- Defining which patients are at increased risk in pregnancy.

- Physiological adaptations of pregnancy, the puerperium, and the postpartum period, with an emphasis on hemodynamic changes.

- Assessment and evaluation in the preconception and early prenatal periods.

- Pregnancy management, including appropriate testing.

- Medications in pregnancy, including a table of common cardiac drugs and their pregnancy categories and lactation risks.

- Breakdown of suggested prenatal care by trimester.

- Intrapartum care, including indications for fluid management, ECG and hemodynamic monitoring, and management of the second stage of delivery.

- Postpartum care, with attention to the very rapid increase in blood volume and concomitant leap in stroke volume and cardiac output.

- Considerations when choosing contraceptive method.

- Cardiac complications seen in pregnancy, including arrhythmias, managing mechanical valves and anticoagulation, heart failure, and cyanosis.

- Indications for and risks associated with interventional therapies during pregnancy.

- Detailed discussion of management of pregnancy for women with specific lesions.

None of the members of the writing committee for the scientific statement had relevant disclosures. Dr. Foley and Dr. Kay reported no disclosures. Dr. Norton reported that she has received research funding from Natera and Ultragenyx.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) brings together recommendations for management of pregnancy for women with serious congenital heart disease. The 38-page document addresses a wide range of complex congenital heart conditions, presenting a newly unified set of recommendations for care that ranges from preconception counseling, through pregnancy, labor, and delivery, to the postpartum period.

Caring for women with complex congenital heart lesions is becoming more commonplace, as more infants undergo successful repairs of previously-unsurvivable cardiac anomalies. “More moms with congenital heart disease are showing up pregnant, having survived the tumultuous peripartum and neonatal period, and are now facing a new set of risks in pregnancy,” Michael Foley, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview.

Joseph Kay, MD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, said that one big benefit of the new scientific statement is having a single reference point for care of these patients. “The scientific statement brings all of the information about caring for these patients together into one document. This will be a very valuable resource for trainees to get a sense of what’s important; it also represents a platform for new programs to understand the scope of services needed,” said Dr. Kay in an interview.

The document provides a thorough review of the physiologic changes of pregnancy and the intrapartum and postpartum periods, noting that the heterogeneity of congenital heart disease means that women who have different lesions carry different risks in pregnancy.

Examples of lesions presenting intermediate risk include most arrhythmias (category II), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and a repaired coarctation (both category II-III). The most severe lesions carry a contraindication for pregnancy; the WHO guidelines suggest discussing termination should women with a category IV lesion become pregnant. Severe mitral stenosis, severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, and severe systemic ventricular dysfunction all place women into category IV.

Beginning with pregnancy risk category III, the WHO guidelines recommend intensive cardiac and obstetric monitoring throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium. Several maternal-fetal medicine specialists interviewed all agreed that an interdisciplinary team is a must for good obstetric care in this population.

How interdisciplinary care plays out can depend on geography and facility-dependent resources. Dr. Kay said that his facility is the referral site for pregnant women with complex congenital lesions in an area that spans the Canadian and the Mexican borders from north to south, and ranges from parts of Kansas to eastern Montana from east to west. Still, Dr. Kay said that even for patients with lower-risk lesions, “We will see patients at least once, at approximately the midpoint of pregnancy, and again during the third trimester if possible.” The specifics of care depend on “the nature of the lesion and the complexity of the disease,” said Dr. Kay.

In his facility, said Dr. Kay, telemetry is available for all of the labor and delivery unit beds. This means that the mother and infant can usually stay together and receive postpartum nursing and lactation care from a skilled staff.

In no circumstances should ob.gyns. go it alone, said Dr. Foley. “The conversation with the ob.gyn. needs to be about comanaging these patients, at the very least. Even the most learned maternal-fetal medicine specialist needs to be working with a cardiologist and an anesthesiologist to create a delivery plan that includes pain management, fluid management, and consideration for intrapartum hemodynamic monitoring,” he said.

And the team needs to be in place long before delivery, Dr. Foley pointed out. “In many hospitals, the care delivery gap may be the inability to have this consistent proactive approach. You can’t expect the best outcomes when you have to hurriedly assemble an unfamiliar ad hoc team when a woman with congenital heart disease presents in labor. Despite their best intentions, inconsistent team members may not have the knowledge and experience to provide the safest care for these patients,” he said.

Though an individualized labor and delivery plan is a must, and a multispecialty team should be assembled, maternal congenital heart disease doesn’t necessarily consign a woman to cesarean delivery. “Most women can and should have a vaginal delivery. It’s safer for them. If a natural delivery may increase risk of issues, we may consider a facilitated second stage of labor with epidural anesthesia and forceps- or vacuum-assisted delivery,” said Dr. Kay.

It’s important to understand the nuances of an individual patient’s health and risk status, said Dr. Norton. “A simplified view is often bad. It’s not the case that ‘it’s always better to deliver’ or ‘it’s always better to have a cesarean delivery.’”

Especially for women who need anticoagulation or who may have lesions that put them at great risk should pregnancy occur, preconception counseling is a vital part of their care, and guidance in the scientific statement can help specialists avoid the complications that can occur in the absence of evidence-based treatment. Said Dr. Kay, “I have seen an unfortunate case or two of patients whose anticoagulation was stopped or changed, contrary to guidelines, and who suffered strokes. I hope more people will see this document.”

Ms. Canobbio echoed the sentiment: “You don’t want to have to backpedal once a young woman presents with a pregnancy. Appropriate contraceptive counseling needs to be part of the conversation.”

One key concept underscored in the scientific statement is that elevated risk persists into the postpartum period. “Following delivery, the mother is still at risk for an extended period of time. The greatest risk for mortality in these patients is post delivery, when a large volume of blood is expelled from the uterus back into the maternal circulation,” said Ms. Canobbio. “These women need close follow-up; we can’t say they are home free until several weeks to 2 months after delivery. The need for vigilance and surveillance continues.”

Since the scientific statement is not a new set of guidelines, but rather a compilation of currently existing reference documents, the authors noted that management differences may exist in some cases, but did not assign greater value to one practice than another. “We addressed that there are differences between the European and the American guidelines. For example, with regard to anticoagulation, both would agree to use Lovenox [enoxaparin], but the difference is whether it should be used for the entire pregnancy or for parts of the pregnancy,” said Ms. Canobbio.

Looking forward, more women with complex congenital heart disease will bear children, but their future is not certain. Said Ms. Canobbio: “The data are growing that if the patient is clinically stable at the time of pregnancy, it’s likely we can get them through safely. What’s not yet known is whether the burden of pregnancy in a woman who is otherwise healthy will shorten her lifespan. However, early data are promising, and it’s looking like these women can fare well.”

Topics covered in the scientific statement include:

- Defining which patients are at increased risk in pregnancy.

- Physiological adaptations of pregnancy, the puerperium, and the postpartum period, with an emphasis on hemodynamic changes.

- Assessment and evaluation in the preconception and early prenatal periods.

- Pregnancy management, including appropriate testing.

- Medications in pregnancy, including a table of common cardiac drugs and their pregnancy categories and lactation risks.

- Breakdown of suggested prenatal care by trimester.

- Intrapartum care, including indications for fluid management, ECG and hemodynamic monitoring, and management of the second stage of delivery.

- Postpartum care, with attention to the very rapid increase in blood volume and concomitant leap in stroke volume and cardiac output.

- Considerations when choosing contraceptive method.

- Cardiac complications seen in pregnancy, including arrhythmias, managing mechanical valves and anticoagulation, heart failure, and cyanosis.

- Indications for and risks associated with interventional therapies during pregnancy.

- Detailed discussion of management of pregnancy for women with specific lesions.

None of the members of the writing committee for the scientific statement had relevant disclosures. Dr. Foley and Dr. Kay reported no disclosures. Dr. Norton reported that she has received research funding from Natera and Ultragenyx.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

Childhood obesity tied to maternal obesity, cesarean birth

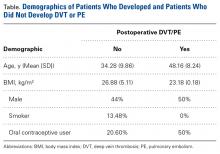

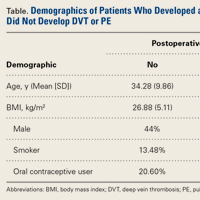

NEW ORLEANS – Maternal obesity and cesarean delivery were each independently associated with increased rates of overweight or obesity during childhood in a prospective study of 1,441 mothers and their children.

In addition, these risks for childhood obesity appeared to interact in an additive way, so that women who were both obese and delivered by C-section had a nearly threefold increased rate of having a child who was overweight or obese at about 5 years of age, compared with children born to normal-weight women who delivered vaginally, Noel T. Mueller, PhD, said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

This finding of a link between maternal overweight and obesity and childhood obesity in the next generation supports results from previously reported studies. The new results “also add to the growing evidence for an association between C-section and obesity [in offspring], as well as C-section and immune-related disorders such as asthma and allergies” in offspring, Dr. Mueller said in an interview.

He hypothesized that delivery mode may contribute to a child’s obesity risk by producing an abnormal gastrointestinal microbiome. For example, vaginal delivery seems to associate with a higher prevalence of Bacteroides species in a child’s gut, bacteria that aid in the digestion of breast milk, Dr. Mueller said.

His study used data collected in the Boston Birth Cohort from 1,441 mothers and their children from full-term, singleton pregnancies born to women with a body mass index of at least 18.5 kg/m2 during 1998-2014. The child’s weight was measured at a median age of 4.8 years, with an interquartile range of 3-6 years. Children were deemed overweight if they were at or above the 85th percentile for weight, according to standards from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Just under half the women were normal weight, slightly more than a quarter were overweight, and a quarter were obese. The incidence of 5-year-old children who were overweight or obese was 70% higher in children of overweight mothers and 80% higher in those with obese mothers, compared with children with normal-weight mothers in an analysis that adjusted for maternal age at delivery, race or ethnicity, and education. Both were statistically significant differences, Dr. Mueller reported.

Two-thirds of the women had vaginal deliveries and a third had C-sections. Overweight or obesity occurred in 40% more of the children delivered by C-section, compared with children born vaginally, a statistically significant difference in an analysis that controlled for the same three covariates as well as prepregnancy body mass index, pregnancy weight gain, and other variables.

When Dr. Mueller and his associates ran a combined analysis they found that the highest risk for childhood overweight or obesity was in children born to obese mothers by C-section, and it was a 2.8-fold higher rate than that in the children born to normal-weight mothers by vaginal delivery, a statistically significant difference.

Dr. Mueller had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW ORLEANS – Maternal obesity and cesarean delivery were each independently associated with increased rates of overweight or obesity during childhood in a prospective study of 1,441 mothers and their children.

In addition, these risks for childhood obesity appeared to interact in an additive way, so that women who were both obese and delivered by C-section had a nearly threefold increased rate of having a child who was overweight or obese at about 5 years of age, compared with children born to normal-weight women who delivered vaginally, Noel T. Mueller, PhD, said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

This finding of a link between maternal overweight and obesity and childhood obesity in the next generation supports results from previously reported studies. The new results “also add to the growing evidence for an association between C-section and obesity [in offspring], as well as C-section and immune-related disorders such as asthma and allergies” in offspring, Dr. Mueller said in an interview.

He hypothesized that delivery mode may contribute to a child’s obesity risk by producing an abnormal gastrointestinal microbiome. For example, vaginal delivery seems to associate with a higher prevalence of Bacteroides species in a child’s gut, bacteria that aid in the digestion of breast milk, Dr. Mueller said.

His study used data collected in the Boston Birth Cohort from 1,441 mothers and their children from full-term, singleton pregnancies born to women with a body mass index of at least 18.5 kg/m2 during 1998-2014. The child’s weight was measured at a median age of 4.8 years, with an interquartile range of 3-6 years. Children were deemed overweight if they were at or above the 85th percentile for weight, according to standards from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Just under half the women were normal weight, slightly more than a quarter were overweight, and a quarter were obese. The incidence of 5-year-old children who were overweight or obese was 70% higher in children of overweight mothers and 80% higher in those with obese mothers, compared with children with normal-weight mothers in an analysis that adjusted for maternal age at delivery, race or ethnicity, and education. Both were statistically significant differences, Dr. Mueller reported.

Two-thirds of the women had vaginal deliveries and a third had C-sections. Overweight or obesity occurred in 40% more of the children delivered by C-section, compared with children born vaginally, a statistically significant difference in an analysis that controlled for the same three covariates as well as prepregnancy body mass index, pregnancy weight gain, and other variables.

When Dr. Mueller and his associates ran a combined analysis they found that the highest risk for childhood overweight or obesity was in children born to obese mothers by C-section, and it was a 2.8-fold higher rate than that in the children born to normal-weight mothers by vaginal delivery, a statistically significant difference.

Dr. Mueller had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW ORLEANS – Maternal obesity and cesarean delivery were each independently associated with increased rates of overweight or obesity during childhood in a prospective study of 1,441 mothers and their children.

In addition, these risks for childhood obesity appeared to interact in an additive way, so that women who were both obese and delivered by C-section had a nearly threefold increased rate of having a child who was overweight or obese at about 5 years of age, compared with children born to normal-weight women who delivered vaginally, Noel T. Mueller, PhD, said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

This finding of a link between maternal overweight and obesity and childhood obesity in the next generation supports results from previously reported studies. The new results “also add to the growing evidence for an association between C-section and obesity [in offspring], as well as C-section and immune-related disorders such as asthma and allergies” in offspring, Dr. Mueller said in an interview.

He hypothesized that delivery mode may contribute to a child’s obesity risk by producing an abnormal gastrointestinal microbiome. For example, vaginal delivery seems to associate with a higher prevalence of Bacteroides species in a child’s gut, bacteria that aid in the digestion of breast milk, Dr. Mueller said.

His study used data collected in the Boston Birth Cohort from 1,441 mothers and their children from full-term, singleton pregnancies born to women with a body mass index of at least 18.5 kg/m2 during 1998-2014. The child’s weight was measured at a median age of 4.8 years, with an interquartile range of 3-6 years. Children were deemed overweight if they were at or above the 85th percentile for weight, according to standards from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Just under half the women were normal weight, slightly more than a quarter were overweight, and a quarter were obese. The incidence of 5-year-old children who were overweight or obese was 70% higher in children of overweight mothers and 80% higher in those with obese mothers, compared with children with normal-weight mothers in an analysis that adjusted for maternal age at delivery, race or ethnicity, and education. Both were statistically significant differences, Dr. Mueller reported.

Two-thirds of the women had vaginal deliveries and a third had C-sections. Overweight or obesity occurred in 40% more of the children delivered by C-section, compared with children born vaginally, a statistically significant difference in an analysis that controlled for the same three covariates as well as prepregnancy body mass index, pregnancy weight gain, and other variables.

When Dr. Mueller and his associates ran a combined analysis they found that the highest risk for childhood overweight or obesity was in children born to obese mothers by C-section, and it was a 2.8-fold higher rate than that in the children born to normal-weight mothers by vaginal delivery, a statistically significant difference.

Dr. Mueller had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Children from obese mothers who had cesarean sections had a 2.8-fold higher obesity rate, compared with children from normal-weight mothers who had vaginal deliveries.

Data source: The Boston Birth Cohort, with prospective data from 1,441 pregnant women and their children.

Disclosures: Dr. Mueller had no disclosures.

Observe, assess, intervene

On most days when I walk into the exam room for a well-child visit, I find an anxious mom or a fretful father sitting next to a fearless child. I quickly shove aside my unrealistic expectation of finding both parents together holding the child. During the progression of my day, I see a diversity of parents playing their parts in caring for their children. It is sometimes a single mom, strong and robust, surrounded by a firm aura of principles and rules; she is concealing all signs of weakness, to make sure her child doesn’t cross any line that she has so cautiously made. Sometimes it is a single mom who is nervous and scared with a galaxy of fear in her eyes, desperately seeking for reassurance of her parenting. Fathers also come playing many roles, from someone struggling with tears as his child gets immunizations, to someone who has parenting in his bag, and skillfully plays eeny meeny miny moe with the little ones in the waiting room.

They all have one thing in common: the immense love for their children and the pressure of being a single or separated parent. It is indeed a reality that I see in most of the clinic rooms – that 60%-70% of children are not living with both mom and dad in the same house. Please note that these are raw data based entirely on my observation. While I watch each parent struggling as mentioned above, my mind often wanders to how each young child copes with such a situation.

What is our role as pediatricians as we walk into the exam room, as we encounter these different family dynamics? To simplify it for myself, I divide it into three categories: Observe, assess, and intervene. Most of the time as physicians, our gut feelings and instincts guide us to where help is needed. It is important to anticipate the changes a family might go through as we meet a first-time single mom or a family who has recently been separated. As we anticipate and observe, it also is important to ask specific questions of parents who may not feel comfortable volunteering this information:

• “Are you and your child undergoing any sort of stress?”

• “How do you think your child is coping with the separation?”

• “Do you identify any flaws in how things are going now?”

Of course, we need to ask questions about stress and family dynamics of all parents. We also should maintain a high level of sensitivity as we approach such questions. It is important to identify any changes in a child’s emotional and social development as we see them on every visit. And when we deem the need, to intervene and identify resources for the family. We also can help parents with ideas for communication with the child; anger management; helping parents and children understand changes; and encouraging open discussion when possible, instead of bottling up unsaid feelings and emotions. This is especially true for single-parent families, but two-parent families undergo stresses as well, for which pediatricians should keep an eye out.

While it is extremely important for us on every well-child visit to ensure that a child’s physical health is up to par, it is equally important not to ignore their emotional and social well-being as we walk in the room so we can help them flourish into the best version of themselves.

Dr. Fatima is a first-year pediatric resident at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

On most days when I walk into the exam room for a well-child visit, I find an anxious mom or a fretful father sitting next to a fearless child. I quickly shove aside my unrealistic expectation of finding both parents together holding the child. During the progression of my day, I see a diversity of parents playing their parts in caring for their children. It is sometimes a single mom, strong and robust, surrounded by a firm aura of principles and rules; she is concealing all signs of weakness, to make sure her child doesn’t cross any line that she has so cautiously made. Sometimes it is a single mom who is nervous and scared with a galaxy of fear in her eyes, desperately seeking for reassurance of her parenting. Fathers also come playing many roles, from someone struggling with tears as his child gets immunizations, to someone who has parenting in his bag, and skillfully plays eeny meeny miny moe with the little ones in the waiting room.

They all have one thing in common: the immense love for their children and the pressure of being a single or separated parent. It is indeed a reality that I see in most of the clinic rooms – that 60%-70% of children are not living with both mom and dad in the same house. Please note that these are raw data based entirely on my observation. While I watch each parent struggling as mentioned above, my mind often wanders to how each young child copes with such a situation.

What is our role as pediatricians as we walk into the exam room, as we encounter these different family dynamics? To simplify it for myself, I divide it into three categories: Observe, assess, and intervene. Most of the time as physicians, our gut feelings and instincts guide us to where help is needed. It is important to anticipate the changes a family might go through as we meet a first-time single mom or a family who has recently been separated. As we anticipate and observe, it also is important to ask specific questions of parents who may not feel comfortable volunteering this information:

• “Are you and your child undergoing any sort of stress?”

• “How do you think your child is coping with the separation?”

• “Do you identify any flaws in how things are going now?”

Of course, we need to ask questions about stress and family dynamics of all parents. We also should maintain a high level of sensitivity as we approach such questions. It is important to identify any changes in a child’s emotional and social development as we see them on every visit. And when we deem the need, to intervene and identify resources for the family. We also can help parents with ideas for communication with the child; anger management; helping parents and children understand changes; and encouraging open discussion when possible, instead of bottling up unsaid feelings and emotions. This is especially true for single-parent families, but two-parent families undergo stresses as well, for which pediatricians should keep an eye out.

While it is extremely important for us on every well-child visit to ensure that a child’s physical health is up to par, it is equally important not to ignore their emotional and social well-being as we walk in the room so we can help them flourish into the best version of themselves.

Dr. Fatima is a first-year pediatric resident at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

On most days when I walk into the exam room for a well-child visit, I find an anxious mom or a fretful father sitting next to a fearless child. I quickly shove aside my unrealistic expectation of finding both parents together holding the child. During the progression of my day, I see a diversity of parents playing their parts in caring for their children. It is sometimes a single mom, strong and robust, surrounded by a firm aura of principles and rules; she is concealing all signs of weakness, to make sure her child doesn’t cross any line that she has so cautiously made. Sometimes it is a single mom who is nervous and scared with a galaxy of fear in her eyes, desperately seeking for reassurance of her parenting. Fathers also come playing many roles, from someone struggling with tears as his child gets immunizations, to someone who has parenting in his bag, and skillfully plays eeny meeny miny moe with the little ones in the waiting room.

They all have one thing in common: the immense love for their children and the pressure of being a single or separated parent. It is indeed a reality that I see in most of the clinic rooms – that 60%-70% of children are not living with both mom and dad in the same house. Please note that these are raw data based entirely on my observation. While I watch each parent struggling as mentioned above, my mind often wanders to how each young child copes with such a situation.

What is our role as pediatricians as we walk into the exam room, as we encounter these different family dynamics? To simplify it for myself, I divide it into three categories: Observe, assess, and intervene. Most of the time as physicians, our gut feelings and instincts guide us to where help is needed. It is important to anticipate the changes a family might go through as we meet a first-time single mom or a family who has recently been separated. As we anticipate and observe, it also is important to ask specific questions of parents who may not feel comfortable volunteering this information:

• “Are you and your child undergoing any sort of stress?”

• “How do you think your child is coping with the separation?”

• “Do you identify any flaws in how things are going now?”

Of course, we need to ask questions about stress and family dynamics of all parents. We also should maintain a high level of sensitivity as we approach such questions. It is important to identify any changes in a child’s emotional and social development as we see them on every visit. And when we deem the need, to intervene and identify resources for the family. We also can help parents with ideas for communication with the child; anger management; helping parents and children understand changes; and encouraging open discussion when possible, instead of bottling up unsaid feelings and emotions. This is especially true for single-parent families, but two-parent families undergo stresses as well, for which pediatricians should keep an eye out.

While it is extremely important for us on every well-child visit to ensure that a child’s physical health is up to par, it is equally important not to ignore their emotional and social well-being as we walk in the room so we can help them flourish into the best version of themselves.

Dr. Fatima is a first-year pediatric resident at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Don’t delay pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for preterm infants

There should be no hesitation in administering the routine vaccination schedule for 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) on account of gestational age or birth weight in preterm infants, researchers concluded.

In a phase IV study, researchers compared 100 term with 100 preterm infants; both groups were vaccinated on the routine schedule at ages 2, 3, 4, and 12 months. After the 12-month (toddler) dose of the PCV13, the infants were evaluated for serum antibody persistence at 12 and 24 months. “To date, no studies have examined the long-term persistence of immune responses to PCV13 in formerly preterm infants,” noted Federico Martinón-Torres, MD, PhD, of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Spain, and his coauthors.

In the study, at six sites in Spain and five sites in Poland between October 2010 and January 2014, both groups were checked for geometric mean concentrations of serotype-specific anticapsular immunoglobulin G binding antibodies and for opsonophagocytic activity. All 200 subjects were white and were generally healthy; the preterm infants were grouped by gestational age at birth of less than 29 weeks (n = 25), 29 weeks to less than 32 weeks (n = 50), or 32 weeks to less than 37 weeks (n = 25). Twelve subjects dropped out of the study by the first year’s evaluation, and another eight of the term subjects and seven of preterm subjects dropped out by the second year’s evaluation (Ped Infect Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001428).

At both follow-up time points, no discernible patterns were observed in IgG GMCs for any serotype or in opsonophagocytic activity geometric mean titers across preterm subgroups based on gestational age.

“The vaccination phase of the study demonstrated that preterm infants are able to generate an immune response to PCV13 that is likely to protect against invasive pneumococcal disease. However, IgG GMCs were lower in preterm than term infants for nearly half of the serotypes at all time points. Antipneumococcal IgG levels in preterm infants were generally lower than in term infants, but fewer differences in opsonophagocytic activity were seen between the groups,” Dr. Martinón-Torres and his associates reported.

Pfizer funded the study. Dr. Martinón-Torres reported receiving research grants and/or honoraria as a consultant/adviser and/or speaker and for conducting vaccine trials for GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer/Wyeth, Sanofi Pasteur, and the Carlos III Health Institute. Several coauthors disclosed ties with pharmaceutical companies; four are stock-holding employees of Pfizer and another is an employee of a company contracted by Pfizer.

There should be no hesitation in administering the routine vaccination schedule for 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) on account of gestational age or birth weight in preterm infants, researchers concluded.

In a phase IV study, researchers compared 100 term with 100 preterm infants; both groups were vaccinated on the routine schedule at ages 2, 3, 4, and 12 months. After the 12-month (toddler) dose of the PCV13, the infants were evaluated for serum antibody persistence at 12 and 24 months. “To date, no studies have examined the long-term persistence of immune responses to PCV13 in formerly preterm infants,” noted Federico Martinón-Torres, MD, PhD, of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Spain, and his coauthors.

In the study, at six sites in Spain and five sites in Poland between October 2010 and January 2014, both groups were checked for geometric mean concentrations of serotype-specific anticapsular immunoglobulin G binding antibodies and for opsonophagocytic activity. All 200 subjects were white and were generally healthy; the preterm infants were grouped by gestational age at birth of less than 29 weeks (n = 25), 29 weeks to less than 32 weeks (n = 50), or 32 weeks to less than 37 weeks (n = 25). Twelve subjects dropped out of the study by the first year’s evaluation, and another eight of the term subjects and seven of preterm subjects dropped out by the second year’s evaluation (Ped Infect Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001428).

At both follow-up time points, no discernible patterns were observed in IgG GMCs for any serotype or in opsonophagocytic activity geometric mean titers across preterm subgroups based on gestational age.