User login

Financial mental health: A framework for improving patients’ lives

The following opinions are my own and not those of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Job insecurity can have a powerful impact on health, particularly mental health.

A recent study of almost 17,500 U.S. working adults found that 33% of the workers thought that their jobs were insecure, and those who reported job insecurity were more likely to be obese, sleep less than 6 hours a day, report pain conditions, and smoke every day. When it came to mental health, those who were job insecure had a likelihood of serious mental illness within the last 30 days almost five times higher than those who were not job insecure (J Community Health. 2016 Sep 10. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0249-8). This study is one of many that highlights the importance of what I call “financial mental health.”

The notion of financial mental health merges two distinct, yet interrelated aspects of patients’ lives into a single construct that can be used to inform resiliency-building behaviors and identify gaps in institutional approaches to supportive services. Patients with strong financial mental health are able to build, maintain, sustain, and revitalize their resiliency across several domains, which include mind, body, spirit, and social indicators.

Financial mental health and mortality

According to the World Bank, “Mental health issues impose an enormous disease burden on societies across the world. Depression alone affects 350 million people globally and is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Despite its enormous social burden, mental disorders continue to be driven into the shadows by stigma, prejudice, and fear. The issue is becoming ever more urgent in light of the forced migration and sustained conflict we are seeing in many countries around the world.”1 In the United States alone, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) reports that almost one-third of Americans are touched by poverty and advocates for financial literacy and empowerment for our most vulnerable citizens.

Unfortunately, mental health clinicians rarely discuss a depressed patient’s financial planning aside from occasional referrals for housing, disability benefits, or subsistence allowances. Based on observations from the World Health Organization, mental health is tied to satisfaction with quality of life. Furthermore, it relates to the ability to cope with life’s stressors, to engage in meaningful and productive activities, and to have a sense of community belonging.

When Abraham Maslow, PhD, described psychological health through the lens of human motivation, he constructed a “hierarchy of needs”2 that at the base lies the physiological requirements for food, shelter, and clothing. Those items represent our most physical necessities, protect us from harm, and determine our survival. They also are related to our need for safety (i.e., job security), which is the second rung on Dr. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In many ways, our ability to feel safe is predicated on our ability to secure our environment with proper housing, healthy nutrition, and appropriate wardrobe (and the accouterments thereof), which, in turn, align us and our families to our culture, community, and socioeconomic status. But it costs money to stay healthy and protected. The CFPB recognized the intersection of these issues and developed a toolkit3 for social service and related agencies aimed at enhancing financial literacy and education within the populations they serve so that those individuals can become more skilled and empowered.

The consequences of poor financial mental health are found in data related to mortality. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documents that lower socioeconomic status is related to higher rates of mortality.4 For Americans living in poverty, their social network, lifestyle, and access to medical care contribute to their inability to live longer lives. Without access to quality and timely medical care, and appropriately funded services, the impacts from trauma, depression, substance abuse, and suicide are more widely experienced. For example, the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report since 2008 has linked suicide and suicide attempts among Service members to failed relationships along with financial and legal problems.

Several of the economic issues relate to conflicts in the workplace that can determine promotions in rank/increases in pay, retention, or transition to civilian employment/unemployment, retirement pay and benefits, or disability compensation. Service members and their families also are subject to divorce and alimony, child support payments, student loan repayments, mortgage defaults, and other liens or judgments. As veterans, this younger cohort must secure new housing, enroll in college or gain employment. This means (often for the first time) financing a mortgage, hunting for a job, filing for GI Bill or other Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits, updating insurance, and family budgeting, while also dealing with the stress of military separation and loss of service identity, and postdeployment health issues. The VA has studied increases in suicide rates, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder within this population – which is not surprising given the level of social instability that they are experiencing.

Furthermore, for veterans who seek treatment, which can mean long inpatient hospitalization or rehabilitation stays, numerous outpatient appointments, and/or medication management, there will be an impact on their finances, because they will be limited in their ability to maintain gainful employment or enroll in classes. This, in turn, complicates family dynamics. Sometimes, spouses have to assume caregiver roles or become the primary breadwinner, which can have an effect on veterans’ self-esteem, sense of belongingness, and burdensomeness – factors associated with suicide.

Mental health also is affected by financial abuse. According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence, financial abuse is a means by which perpetrators can control their victims who are elderly, disabled, subjects of human trafficking, or their partners. Although financial abuse occurs across all socioeconomic classes, usually victims who are experiencing physical and emotional abuse also are being controlled by having their finances or assets taken or withheld from them. Survivors able to extricate themselves from an abuser often are dealing with depression, anxiety, substance abuse, or suicidality. Under that state of mind, they also must find ways to repair their employability and insurability, recover from debt or identity theft, restore their credit and rebuild assets, file for divorce or protective orders, or claim unpaid alimony or child support from the perpetrator and secure safe housing – all while managing their symptoms.

Concrete steps

Individuals can take steps to ensure their financial mental health. Looking at Dr. Maslow’s hierarchy, the pinnacle of the pyramid centers on activities that relate to self-efficacy and esteem. Financial planning is an activity that can foster those feelings but requires the right blend of knowledge and information. Investing in the market has been described as an emotional experience. When the market is up and risk is high, emotions are positive; but when it is low, despondency over a portfolio can set in, and emotions may run scared. Investing comes with its risks and rewards. The receptiveness that individuals have for financial planning and investing will depend upon their views about tolerating risk, as well as their lifestyle goals and objectives, retirement plans, and health concerns.

Trauma survivors who tend to experience anxiety, depression, guilt, or emotional numbing – and have a foreshortened sense of future – may find it difficult to focus on a long-term financial plan. In the early stages of therapy and recovery, finance efforts may need to be concentrated primarily on obtaining a job with benefits and proper housing. Reducing debt and restoring credit become secondary challenges, and investing and retirement planning may take an even further backseat. However, for those experiencing psychological challenges, financial planning can be empowering and reassuring, because it provides a sense of structure, identifies goals, and restores hope for a better future.

Communities and organizations that support individuals with psychiatric conditions may need to further consider embedding financial planning into a case management approach that is more holistic and concentrates on all domains of social resilience as recommended by the CFPB. Training clinicians about financial planning can be useful because of the tools it can offer patients who are working on their recovery and rebuilding their futures.

People contemplating suicide are known to first get their affairs in order and often will update their beneficiary status, sometime making multiple changes depending on their emotional state within a month of their death, so agents should be aware of these habits. When working with veterans, abuse survivors, or those with more serious mental illness, ensuring that they are knowledgeable about available government benefits and pairing them with private sector products can help people who might seem like they are in denial or procrastinating about investing but are actually feeling overwhelmed, confused, and lack confidence in their own decision making. Partitioning these goals into short- and long-term steps and providing more attentive case management that builds trust and addresses concerns can help people stay engaged in reaching their goals.

Financial mental health is a concept rooted in individual resilience and the approaches needed to maximize it. As mental health professionals, we can leverage our own knowledge with that of personal finance experts to help our patients build resilience skills and tools. As result, patients in the most disadvantaged and disenfranchised communities will not only survive but thrive.

References

1 “Out of the Shadows: Making Mental Health a Global Priority,” April 13-14, 2016.

2 Psychological Rev. 1943;50:370-96. “A Theory of Human Motivation” is represented as a pyramid with the most fundamental needs at the base. Those needs are physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization in descending order.

3 “Your Money, Your Goals: A financial empowerment toolkit for Social Services programs,” April 2015.

4 National Vital Statistics Report, “Deaths: Final Data for 2014,” Vol. 65 No. 4, June 30, 2016.

Ms. Garrick is a special assistant, manpower and reserve affairs for the U.S. Department of Defense. Previously, she served as the director of the Defense Suicide Prevention Office. She has been a leader in veterans’ disability policy and, suicide prevention and peer support programs; worked with Gulf War veterans as an Army social work officer; and provided individual, group, and family therapy to Vietnam veterans their families dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The following opinions are my own and not those of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Job insecurity can have a powerful impact on health, particularly mental health.

A recent study of almost 17,500 U.S. working adults found that 33% of the workers thought that their jobs were insecure, and those who reported job insecurity were more likely to be obese, sleep less than 6 hours a day, report pain conditions, and smoke every day. When it came to mental health, those who were job insecure had a likelihood of serious mental illness within the last 30 days almost five times higher than those who were not job insecure (J Community Health. 2016 Sep 10. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0249-8). This study is one of many that highlights the importance of what I call “financial mental health.”

The notion of financial mental health merges two distinct, yet interrelated aspects of patients’ lives into a single construct that can be used to inform resiliency-building behaviors and identify gaps in institutional approaches to supportive services. Patients with strong financial mental health are able to build, maintain, sustain, and revitalize their resiliency across several domains, which include mind, body, spirit, and social indicators.

Financial mental health and mortality

According to the World Bank, “Mental health issues impose an enormous disease burden on societies across the world. Depression alone affects 350 million people globally and is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Despite its enormous social burden, mental disorders continue to be driven into the shadows by stigma, prejudice, and fear. The issue is becoming ever more urgent in light of the forced migration and sustained conflict we are seeing in many countries around the world.”1 In the United States alone, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) reports that almost one-third of Americans are touched by poverty and advocates for financial literacy and empowerment for our most vulnerable citizens.

Unfortunately, mental health clinicians rarely discuss a depressed patient’s financial planning aside from occasional referrals for housing, disability benefits, or subsistence allowances. Based on observations from the World Health Organization, mental health is tied to satisfaction with quality of life. Furthermore, it relates to the ability to cope with life’s stressors, to engage in meaningful and productive activities, and to have a sense of community belonging.

When Abraham Maslow, PhD, described psychological health through the lens of human motivation, he constructed a “hierarchy of needs”2 that at the base lies the physiological requirements for food, shelter, and clothing. Those items represent our most physical necessities, protect us from harm, and determine our survival. They also are related to our need for safety (i.e., job security), which is the second rung on Dr. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In many ways, our ability to feel safe is predicated on our ability to secure our environment with proper housing, healthy nutrition, and appropriate wardrobe (and the accouterments thereof), which, in turn, align us and our families to our culture, community, and socioeconomic status. But it costs money to stay healthy and protected. The CFPB recognized the intersection of these issues and developed a toolkit3 for social service and related agencies aimed at enhancing financial literacy and education within the populations they serve so that those individuals can become more skilled and empowered.

The consequences of poor financial mental health are found in data related to mortality. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documents that lower socioeconomic status is related to higher rates of mortality.4 For Americans living in poverty, their social network, lifestyle, and access to medical care contribute to their inability to live longer lives. Without access to quality and timely medical care, and appropriately funded services, the impacts from trauma, depression, substance abuse, and suicide are more widely experienced. For example, the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report since 2008 has linked suicide and suicide attempts among Service members to failed relationships along with financial and legal problems.

Several of the economic issues relate to conflicts in the workplace that can determine promotions in rank/increases in pay, retention, or transition to civilian employment/unemployment, retirement pay and benefits, or disability compensation. Service members and their families also are subject to divorce and alimony, child support payments, student loan repayments, mortgage defaults, and other liens or judgments. As veterans, this younger cohort must secure new housing, enroll in college or gain employment. This means (often for the first time) financing a mortgage, hunting for a job, filing for GI Bill or other Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits, updating insurance, and family budgeting, while also dealing with the stress of military separation and loss of service identity, and postdeployment health issues. The VA has studied increases in suicide rates, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder within this population – which is not surprising given the level of social instability that they are experiencing.

Furthermore, for veterans who seek treatment, which can mean long inpatient hospitalization or rehabilitation stays, numerous outpatient appointments, and/or medication management, there will be an impact on their finances, because they will be limited in their ability to maintain gainful employment or enroll in classes. This, in turn, complicates family dynamics. Sometimes, spouses have to assume caregiver roles or become the primary breadwinner, which can have an effect on veterans’ self-esteem, sense of belongingness, and burdensomeness – factors associated with suicide.

Mental health also is affected by financial abuse. According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence, financial abuse is a means by which perpetrators can control their victims who are elderly, disabled, subjects of human trafficking, or their partners. Although financial abuse occurs across all socioeconomic classes, usually victims who are experiencing physical and emotional abuse also are being controlled by having their finances or assets taken or withheld from them. Survivors able to extricate themselves from an abuser often are dealing with depression, anxiety, substance abuse, or suicidality. Under that state of mind, they also must find ways to repair their employability and insurability, recover from debt or identity theft, restore their credit and rebuild assets, file for divorce or protective orders, or claim unpaid alimony or child support from the perpetrator and secure safe housing – all while managing their symptoms.

Concrete steps

Individuals can take steps to ensure their financial mental health. Looking at Dr. Maslow’s hierarchy, the pinnacle of the pyramid centers on activities that relate to self-efficacy and esteem. Financial planning is an activity that can foster those feelings but requires the right blend of knowledge and information. Investing in the market has been described as an emotional experience. When the market is up and risk is high, emotions are positive; but when it is low, despondency over a portfolio can set in, and emotions may run scared. Investing comes with its risks and rewards. The receptiveness that individuals have for financial planning and investing will depend upon their views about tolerating risk, as well as their lifestyle goals and objectives, retirement plans, and health concerns.

Trauma survivors who tend to experience anxiety, depression, guilt, or emotional numbing – and have a foreshortened sense of future – may find it difficult to focus on a long-term financial plan. In the early stages of therapy and recovery, finance efforts may need to be concentrated primarily on obtaining a job with benefits and proper housing. Reducing debt and restoring credit become secondary challenges, and investing and retirement planning may take an even further backseat. However, for those experiencing psychological challenges, financial planning can be empowering and reassuring, because it provides a sense of structure, identifies goals, and restores hope for a better future.

Communities and organizations that support individuals with psychiatric conditions may need to further consider embedding financial planning into a case management approach that is more holistic and concentrates on all domains of social resilience as recommended by the CFPB. Training clinicians about financial planning can be useful because of the tools it can offer patients who are working on their recovery and rebuilding their futures.

People contemplating suicide are known to first get their affairs in order and often will update their beneficiary status, sometime making multiple changes depending on their emotional state within a month of their death, so agents should be aware of these habits. When working with veterans, abuse survivors, or those with more serious mental illness, ensuring that they are knowledgeable about available government benefits and pairing them with private sector products can help people who might seem like they are in denial or procrastinating about investing but are actually feeling overwhelmed, confused, and lack confidence in their own decision making. Partitioning these goals into short- and long-term steps and providing more attentive case management that builds trust and addresses concerns can help people stay engaged in reaching their goals.

Financial mental health is a concept rooted in individual resilience and the approaches needed to maximize it. As mental health professionals, we can leverage our own knowledge with that of personal finance experts to help our patients build resilience skills and tools. As result, patients in the most disadvantaged and disenfranchised communities will not only survive but thrive.

References

1 “Out of the Shadows: Making Mental Health a Global Priority,” April 13-14, 2016.

2 Psychological Rev. 1943;50:370-96. “A Theory of Human Motivation” is represented as a pyramid with the most fundamental needs at the base. Those needs are physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization in descending order.

3 “Your Money, Your Goals: A financial empowerment toolkit for Social Services programs,” April 2015.

4 National Vital Statistics Report, “Deaths: Final Data for 2014,” Vol. 65 No. 4, June 30, 2016.

Ms. Garrick is a special assistant, manpower and reserve affairs for the U.S. Department of Defense. Previously, she served as the director of the Defense Suicide Prevention Office. She has been a leader in veterans’ disability policy and, suicide prevention and peer support programs; worked with Gulf War veterans as an Army social work officer; and provided individual, group, and family therapy to Vietnam veterans their families dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The following opinions are my own and not those of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Job insecurity can have a powerful impact on health, particularly mental health.

A recent study of almost 17,500 U.S. working adults found that 33% of the workers thought that their jobs were insecure, and those who reported job insecurity were more likely to be obese, sleep less than 6 hours a day, report pain conditions, and smoke every day. When it came to mental health, those who were job insecure had a likelihood of serious mental illness within the last 30 days almost five times higher than those who were not job insecure (J Community Health. 2016 Sep 10. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0249-8). This study is one of many that highlights the importance of what I call “financial mental health.”

The notion of financial mental health merges two distinct, yet interrelated aspects of patients’ lives into a single construct that can be used to inform resiliency-building behaviors and identify gaps in institutional approaches to supportive services. Patients with strong financial mental health are able to build, maintain, sustain, and revitalize their resiliency across several domains, which include mind, body, spirit, and social indicators.

Financial mental health and mortality

According to the World Bank, “Mental health issues impose an enormous disease burden on societies across the world. Depression alone affects 350 million people globally and is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Despite its enormous social burden, mental disorders continue to be driven into the shadows by stigma, prejudice, and fear. The issue is becoming ever more urgent in light of the forced migration and sustained conflict we are seeing in many countries around the world.”1 In the United States alone, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) reports that almost one-third of Americans are touched by poverty and advocates for financial literacy and empowerment for our most vulnerable citizens.

Unfortunately, mental health clinicians rarely discuss a depressed patient’s financial planning aside from occasional referrals for housing, disability benefits, or subsistence allowances. Based on observations from the World Health Organization, mental health is tied to satisfaction with quality of life. Furthermore, it relates to the ability to cope with life’s stressors, to engage in meaningful and productive activities, and to have a sense of community belonging.

When Abraham Maslow, PhD, described psychological health through the lens of human motivation, he constructed a “hierarchy of needs”2 that at the base lies the physiological requirements for food, shelter, and clothing. Those items represent our most physical necessities, protect us from harm, and determine our survival. They also are related to our need for safety (i.e., job security), which is the second rung on Dr. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In many ways, our ability to feel safe is predicated on our ability to secure our environment with proper housing, healthy nutrition, and appropriate wardrobe (and the accouterments thereof), which, in turn, align us and our families to our culture, community, and socioeconomic status. But it costs money to stay healthy and protected. The CFPB recognized the intersection of these issues and developed a toolkit3 for social service and related agencies aimed at enhancing financial literacy and education within the populations they serve so that those individuals can become more skilled and empowered.

The consequences of poor financial mental health are found in data related to mortality. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documents that lower socioeconomic status is related to higher rates of mortality.4 For Americans living in poverty, their social network, lifestyle, and access to medical care contribute to their inability to live longer lives. Without access to quality and timely medical care, and appropriately funded services, the impacts from trauma, depression, substance abuse, and suicide are more widely experienced. For example, the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report since 2008 has linked suicide and suicide attempts among Service members to failed relationships along with financial and legal problems.

Several of the economic issues relate to conflicts in the workplace that can determine promotions in rank/increases in pay, retention, or transition to civilian employment/unemployment, retirement pay and benefits, or disability compensation. Service members and their families also are subject to divorce and alimony, child support payments, student loan repayments, mortgage defaults, and other liens or judgments. As veterans, this younger cohort must secure new housing, enroll in college or gain employment. This means (often for the first time) financing a mortgage, hunting for a job, filing for GI Bill or other Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits, updating insurance, and family budgeting, while also dealing with the stress of military separation and loss of service identity, and postdeployment health issues. The VA has studied increases in suicide rates, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder within this population – which is not surprising given the level of social instability that they are experiencing.

Furthermore, for veterans who seek treatment, which can mean long inpatient hospitalization or rehabilitation stays, numerous outpatient appointments, and/or medication management, there will be an impact on their finances, because they will be limited in their ability to maintain gainful employment or enroll in classes. This, in turn, complicates family dynamics. Sometimes, spouses have to assume caregiver roles or become the primary breadwinner, which can have an effect on veterans’ self-esteem, sense of belongingness, and burdensomeness – factors associated with suicide.

Mental health also is affected by financial abuse. According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence, financial abuse is a means by which perpetrators can control their victims who are elderly, disabled, subjects of human trafficking, or their partners. Although financial abuse occurs across all socioeconomic classes, usually victims who are experiencing physical and emotional abuse also are being controlled by having their finances or assets taken or withheld from them. Survivors able to extricate themselves from an abuser often are dealing with depression, anxiety, substance abuse, or suicidality. Under that state of mind, they also must find ways to repair their employability and insurability, recover from debt or identity theft, restore their credit and rebuild assets, file for divorce or protective orders, or claim unpaid alimony or child support from the perpetrator and secure safe housing – all while managing their symptoms.

Concrete steps

Individuals can take steps to ensure their financial mental health. Looking at Dr. Maslow’s hierarchy, the pinnacle of the pyramid centers on activities that relate to self-efficacy and esteem. Financial planning is an activity that can foster those feelings but requires the right blend of knowledge and information. Investing in the market has been described as an emotional experience. When the market is up and risk is high, emotions are positive; but when it is low, despondency over a portfolio can set in, and emotions may run scared. Investing comes with its risks and rewards. The receptiveness that individuals have for financial planning and investing will depend upon their views about tolerating risk, as well as their lifestyle goals and objectives, retirement plans, and health concerns.

Trauma survivors who tend to experience anxiety, depression, guilt, or emotional numbing – and have a foreshortened sense of future – may find it difficult to focus on a long-term financial plan. In the early stages of therapy and recovery, finance efforts may need to be concentrated primarily on obtaining a job with benefits and proper housing. Reducing debt and restoring credit become secondary challenges, and investing and retirement planning may take an even further backseat. However, for those experiencing psychological challenges, financial planning can be empowering and reassuring, because it provides a sense of structure, identifies goals, and restores hope for a better future.

Communities and organizations that support individuals with psychiatric conditions may need to further consider embedding financial planning into a case management approach that is more holistic and concentrates on all domains of social resilience as recommended by the CFPB. Training clinicians about financial planning can be useful because of the tools it can offer patients who are working on their recovery and rebuilding their futures.

People contemplating suicide are known to first get their affairs in order and often will update their beneficiary status, sometime making multiple changes depending on their emotional state within a month of their death, so agents should be aware of these habits. When working with veterans, abuse survivors, or those with more serious mental illness, ensuring that they are knowledgeable about available government benefits and pairing them with private sector products can help people who might seem like they are in denial or procrastinating about investing but are actually feeling overwhelmed, confused, and lack confidence in their own decision making. Partitioning these goals into short- and long-term steps and providing more attentive case management that builds trust and addresses concerns can help people stay engaged in reaching their goals.

Financial mental health is a concept rooted in individual resilience and the approaches needed to maximize it. As mental health professionals, we can leverage our own knowledge with that of personal finance experts to help our patients build resilience skills and tools. As result, patients in the most disadvantaged and disenfranchised communities will not only survive but thrive.

References

1 “Out of the Shadows: Making Mental Health a Global Priority,” April 13-14, 2016.

2 Psychological Rev. 1943;50:370-96. “A Theory of Human Motivation” is represented as a pyramid with the most fundamental needs at the base. Those needs are physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization in descending order.

3 “Your Money, Your Goals: A financial empowerment toolkit for Social Services programs,” April 2015.

4 National Vital Statistics Report, “Deaths: Final Data for 2014,” Vol. 65 No. 4, June 30, 2016.

Ms. Garrick is a special assistant, manpower and reserve affairs for the U.S. Department of Defense. Previously, she served as the director of the Defense Suicide Prevention Office. She has been a leader in veterans’ disability policy and, suicide prevention and peer support programs; worked with Gulf War veterans as an Army social work officer; and provided individual, group, and family therapy to Vietnam veterans their families dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder.

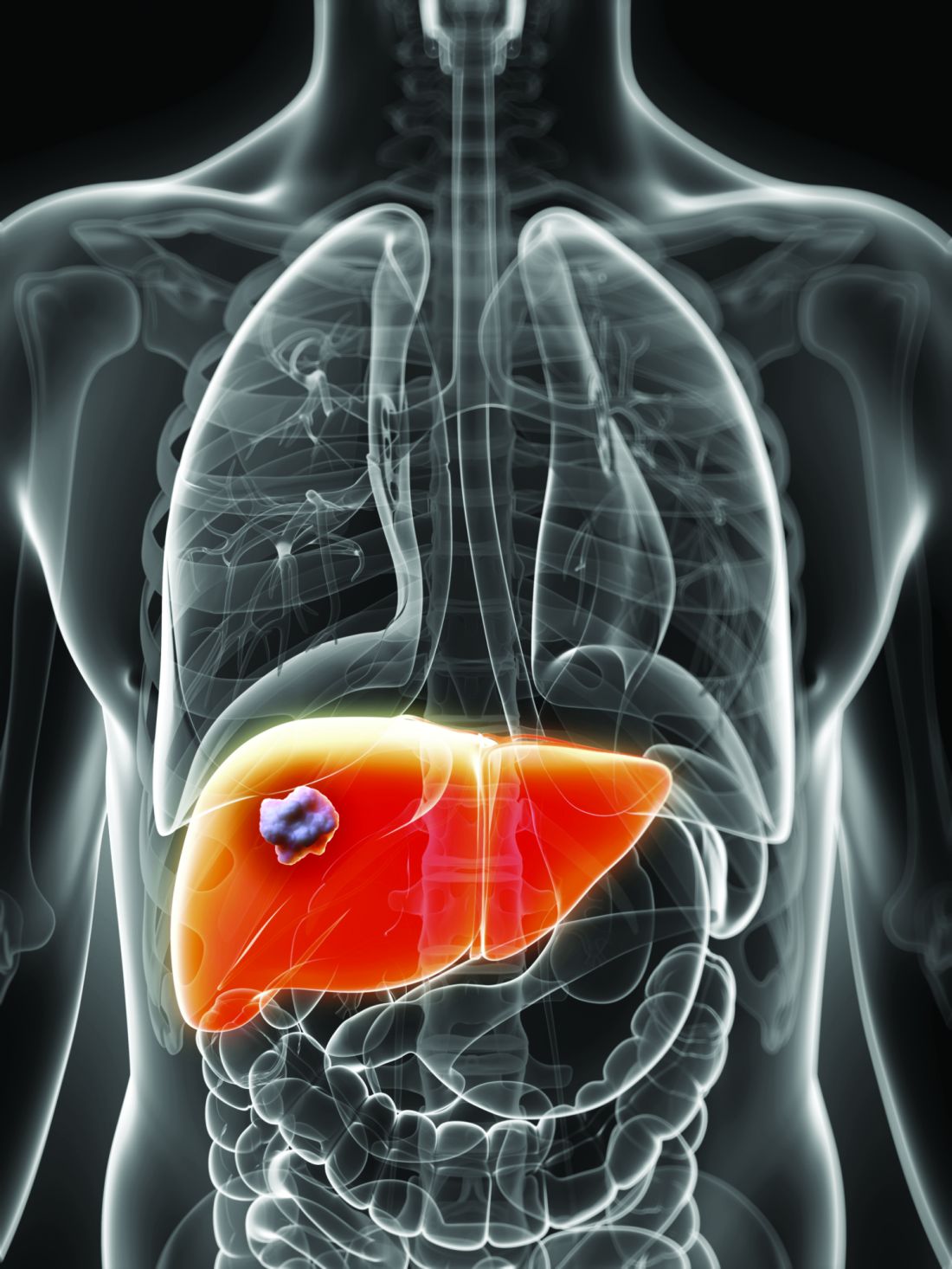

SNP predicts liver cancer in hepatitis C patients regardless of SVR

BOSTON – rs4836493, a single nucleotide polymorphism of the gene encoding chondroitin sulfate synthase-3, significantly predicted hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with HCV even when they achieved sustained virologic response on pegylated interferon, according to a genome-wide association study.

The next step is to determine whether rs4836493 predicts liver cancer after SVR on the new direct-acting antiviral regimens, Basile Njei, MD, MPH, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Cirrhotic patients face about a 2%-7% annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, noted Dr. Njei of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “Recent studies show that people with HCV may still develop hepatocellular carcinoma even after achieving SVR,” he said.

To look for genetic predictors of this outcome, he and his associates genotyped 958 patients with HCV and advanced hepatic fibrosis from the Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment against Cirrhosis (HALT-C) study. This trial had evaluated long-term, low-dose pegylated interferon therapy (90 mcg per week for 3.5 years) as a means of keeping fibrosis from progressing among HCV patients who had failed peginterferon and ribavirin therapy.

A total of 63% of patients had cirrhosis, and 55 (5.7%) developed biopsy or imaging-confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma over a median of 80 months of follow-up, Dr. Njei said. After the researchers controlled for age, sex, Ishak fibrosis score, and SVR status, rs4836493 predicted hepatocellular carcinoma with a highly significant P value of .000004.

This SNP is located on the CHSY3 gene, which plays a role in the chondroitin polymerization, tissue development, and morphogenesis, according to Dr. Njei. Notably, the gene has been implicated in the biology of colorectal tumors, he added.

Dr. Njei and his associates genotyped patients by using the 610-Quad platform, which contains more than 600,000 SNPs. They double-checked results and conducted more genetic analyses using PLINK 1.9, a free, open-source software program for genome-wide association data. Three-quarters of patients in the study were white, 72% were male, and median age at enrollment was 50 years, he noted.

Linking a single SNP to liver cancer despite SVR is a striking finding, but it is also preliminary, Dr. Njei cautioned. “The SNP identified in our discovery genome-wide association study needs future replication and validation in patients who achieve SVR after receiving the new direct-acting antiviral therapies,” he said.

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding. Dr. Njei and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – rs4836493, a single nucleotide polymorphism of the gene encoding chondroitin sulfate synthase-3, significantly predicted hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with HCV even when they achieved sustained virologic response on pegylated interferon, according to a genome-wide association study.

The next step is to determine whether rs4836493 predicts liver cancer after SVR on the new direct-acting antiviral regimens, Basile Njei, MD, MPH, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Cirrhotic patients face about a 2%-7% annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, noted Dr. Njei of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “Recent studies show that people with HCV may still develop hepatocellular carcinoma even after achieving SVR,” he said.

To look for genetic predictors of this outcome, he and his associates genotyped 958 patients with HCV and advanced hepatic fibrosis from the Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment against Cirrhosis (HALT-C) study. This trial had evaluated long-term, low-dose pegylated interferon therapy (90 mcg per week for 3.5 years) as a means of keeping fibrosis from progressing among HCV patients who had failed peginterferon and ribavirin therapy.

A total of 63% of patients had cirrhosis, and 55 (5.7%) developed biopsy or imaging-confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma over a median of 80 months of follow-up, Dr. Njei said. After the researchers controlled for age, sex, Ishak fibrosis score, and SVR status, rs4836493 predicted hepatocellular carcinoma with a highly significant P value of .000004.

This SNP is located on the CHSY3 gene, which plays a role in the chondroitin polymerization, tissue development, and morphogenesis, according to Dr. Njei. Notably, the gene has been implicated in the biology of colorectal tumors, he added.

Dr. Njei and his associates genotyped patients by using the 610-Quad platform, which contains more than 600,000 SNPs. They double-checked results and conducted more genetic analyses using PLINK 1.9, a free, open-source software program for genome-wide association data. Three-quarters of patients in the study were white, 72% were male, and median age at enrollment was 50 years, he noted.

Linking a single SNP to liver cancer despite SVR is a striking finding, but it is also preliminary, Dr. Njei cautioned. “The SNP identified in our discovery genome-wide association study needs future replication and validation in patients who achieve SVR after receiving the new direct-acting antiviral therapies,” he said.

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding. Dr. Njei and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – rs4836493, a single nucleotide polymorphism of the gene encoding chondroitin sulfate synthase-3, significantly predicted hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with HCV even when they achieved sustained virologic response on pegylated interferon, according to a genome-wide association study.

The next step is to determine whether rs4836493 predicts liver cancer after SVR on the new direct-acting antiviral regimens, Basile Njei, MD, MPH, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Cirrhotic patients face about a 2%-7% annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, noted Dr. Njei of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “Recent studies show that people with HCV may still develop hepatocellular carcinoma even after achieving SVR,” he said.

To look for genetic predictors of this outcome, he and his associates genotyped 958 patients with HCV and advanced hepatic fibrosis from the Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment against Cirrhosis (HALT-C) study. This trial had evaluated long-term, low-dose pegylated interferon therapy (90 mcg per week for 3.5 years) as a means of keeping fibrosis from progressing among HCV patients who had failed peginterferon and ribavirin therapy.

A total of 63% of patients had cirrhosis, and 55 (5.7%) developed biopsy or imaging-confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma over a median of 80 months of follow-up, Dr. Njei said. After the researchers controlled for age, sex, Ishak fibrosis score, and SVR status, rs4836493 predicted hepatocellular carcinoma with a highly significant P value of .000004.

This SNP is located on the CHSY3 gene, which plays a role in the chondroitin polymerization, tissue development, and morphogenesis, according to Dr. Njei. Notably, the gene has been implicated in the biology of colorectal tumors, he added.

Dr. Njei and his associates genotyped patients by using the 610-Quad platform, which contains more than 600,000 SNPs. They double-checked results and conducted more genetic analyses using PLINK 1.9, a free, open-source software program for genome-wide association data. Three-quarters of patients in the study were white, 72% were male, and median age at enrollment was 50 years, he noted.

Linking a single SNP to liver cancer despite SVR is a striking finding, but it is also preliminary, Dr. Njei cautioned. “The SNP identified in our discovery genome-wide association study needs future replication and validation in patients who achieve SVR after receiving the new direct-acting antiviral therapies,” he said.

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding. Dr. Njei and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Key clinical point: A single nucleotide polymorphism of the CHSY3 gene predicted liver cancer in patients who successfully completed treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus infection.

Major finding: After researchers controlled for sustained virologic response and other confounders, the rs4836493 variant predicted hepatocellular carcinoma with a P value of .000004.

Data source: A genome-wide association study of 958 HCV patients with advanced hepatic fibrosis from the HALT-C trial.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding. Dr. Njei and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: TNF inhibitors don’t boost cancer risk in JIA

WASHINGTON – Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors don’t appear to confer any additional cancer risk upon children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis above the increased incidence of cancer that comes hand in hand with the disease itself.

In 2009, the drugs came under suspicion of boosting the already-known increased cancer risk in these patients, Timothy G. Beukelman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. But the large database review that he conducted with his colleagues doesn’t validate those fears.

“I feel fairly confident now that I can stand in front of parents and say that we can treat their child effectively without putting that child at an even higher risk of a malignancy,” he said in a video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Thomas J.A. Lehman, MD, chief of pediatric rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and professor of clinical pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, agreed.

“This study again indicates that anti-TNF therapy does not increase the risk of cancer for children with arthritis,” he said in an interview. “Although children with rheumatic diseases have a small increased background risk of malignancies, this is independent of the use of anti-TNF therapies. For physicians who have cared for children in the era when we did not have anti-TNF therapies available, it is clear that any minor risks associated with these medications are far outweighed by their dramatic benefits.”

In the last few years, five large studies have found that children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) have a two- to sixfold increased malignancy risk, compared with the general pediatric population. However, only two of those studies included children taking TNF inhibitors, who comprised just 2% and 9% of those study populations.

In 2009, based on voluntary adverse event reporting, the Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning on TNF inhibitors, citing a possibly increased risk of cancer in children and adolescents who received the drugs for JIA, inflammatory bowel diseases, and other inflammatory diseases.

Shortly thereafter, a report identified a fivefold increase in the risk of childhood lymphoma associated with the medications (Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Aug;62[8]:2517-24). Other studies have not borne this out, but the boxed warning stands.

To further explore the association, Dr. Beukelman of the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and his associates examined billing data from two large national billing databases: the National U.S. Truven MarketScan claims database and Medicaid billing records. Together, the databases contained information on 27,000 children with JIA who received a prescription for a TNF inhibitor any time during 2000-2014. Cancer rates in this population were compared with those seen in a cohort of 2.64 million children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who were included in the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The investigators chose individuals with ADHD as a control group because of ADHD’s chronicity and lack of any association with cancer risk.

Dr. Beukelman also performed a within-group analysis on the JIA patients, comparing cancer rates among those treated with a TNF inhibitor and with methotrexate. The mean follow-up for patients who took TNF inhibitors was 4 years (median of 1.4 years), but there were a full 14 years of data for some patients.

Among the controls, with more than 4 million person-years of follow-up, there were 727 cases of any malignancy – a standardized incident rate (SIR) of 1.03. Among all children with JIA, with more than 52,000 person-years of follow-up, there were 20 malignancies. The SEER database predicted eight among a sex- and age-matched cohort of healthy children. This translated to an SIR of 2.4. This represents the baseline increased risk of cancer conferred by JIA alone.

Nine malignancies occurred in the subgroup of children with JIA who took no medications. The SEER expectation among this group was 3.8 cancers, also translating to an SIR of 2.4

One malignancy occurred in the group treated with methotrexate only. Among these children, the SEER expected number was 1.9; the SIR in this group was 0.53.

Seven malignancies occurred among children who took TNF inhibitors, translating to an SIR of 2.9. Six occurred in children who took a TNF inhibitor in combination with or without methotrexate – an SIR of 3.0.

A final group consisted of children who took a wide range of other medications used in JIA (abatacept, anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, ustekinumab, tofacitinib, azathioprine, cyclosporine, gold, leflunomide, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, thalidomide, lenalidomide). This group also included patients who may or may not have taken methotrexate or a TNF inhibitor. Among these, there were four cancers when the SEER expected number was 0.7. This translated to an SIR of almost 6 – a surprising finding, Dr. Beukelman said. But since there were only four cancers and the group was exposed to so many different medications, it’s tough to know what that means, if anything, Dr. Beukelman said.

“There’s a lot to unpack here. The treatment paradigm for JIA is methotrexate followed by a TNF inhibitor if that’s ineffective. So these kids were on all of these more uncommon drugs,” suggesting that neither TNF inhibition nor methotrexate worked. “Some of these patients might actually have had systemic arthritis, Still’s disease, which is a completely separate thing, and we don’t know anything about the risk of malignancy in that. They might have an even higher rate of malignancies at baseline due to having worse disease, or uncontrolled inflammation. It is concerning, but I think it probably speaks to the fact that these patients are difficult to treat and probably at higher risk.”

Dr. Beukelman didn’t specifically break out the types and numbers of cancer, except to say that 3 of the 20 were lymphomas. The rest were leukemias and brain cancers – a finding that reflects the general pattern of childhood malignancies.

“Unfortunately, the most common childhood cancers are lymphomas, leukemias, and brain cancers, and that is what we saw in this study as well,” he said.

The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Beukelman noted that he has received consulting fees from Novartis, Genetech/Roche, and UCB.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors don’t appear to confer any additional cancer risk upon children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis above the increased incidence of cancer that comes hand in hand with the disease itself.

In 2009, the drugs came under suspicion of boosting the already-known increased cancer risk in these patients, Timothy G. Beukelman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. But the large database review that he conducted with his colleagues doesn’t validate those fears.

“I feel fairly confident now that I can stand in front of parents and say that we can treat their child effectively without putting that child at an even higher risk of a malignancy,” he said in a video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Thomas J.A. Lehman, MD, chief of pediatric rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and professor of clinical pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, agreed.

“This study again indicates that anti-TNF therapy does not increase the risk of cancer for children with arthritis,” he said in an interview. “Although children with rheumatic diseases have a small increased background risk of malignancies, this is independent of the use of anti-TNF therapies. For physicians who have cared for children in the era when we did not have anti-TNF therapies available, it is clear that any minor risks associated with these medications are far outweighed by their dramatic benefits.”

In the last few years, five large studies have found that children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) have a two- to sixfold increased malignancy risk, compared with the general pediatric population. However, only two of those studies included children taking TNF inhibitors, who comprised just 2% and 9% of those study populations.

In 2009, based on voluntary adverse event reporting, the Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning on TNF inhibitors, citing a possibly increased risk of cancer in children and adolescents who received the drugs for JIA, inflammatory bowel diseases, and other inflammatory diseases.

Shortly thereafter, a report identified a fivefold increase in the risk of childhood lymphoma associated with the medications (Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Aug;62[8]:2517-24). Other studies have not borne this out, but the boxed warning stands.

To further explore the association, Dr. Beukelman of the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and his associates examined billing data from two large national billing databases: the National U.S. Truven MarketScan claims database and Medicaid billing records. Together, the databases contained information on 27,000 children with JIA who received a prescription for a TNF inhibitor any time during 2000-2014. Cancer rates in this population were compared with those seen in a cohort of 2.64 million children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who were included in the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The investigators chose individuals with ADHD as a control group because of ADHD’s chronicity and lack of any association with cancer risk.

Dr. Beukelman also performed a within-group analysis on the JIA patients, comparing cancer rates among those treated with a TNF inhibitor and with methotrexate. The mean follow-up for patients who took TNF inhibitors was 4 years (median of 1.4 years), but there were a full 14 years of data for some patients.

Among the controls, with more than 4 million person-years of follow-up, there were 727 cases of any malignancy – a standardized incident rate (SIR) of 1.03. Among all children with JIA, with more than 52,000 person-years of follow-up, there were 20 malignancies. The SEER database predicted eight among a sex- and age-matched cohort of healthy children. This translated to an SIR of 2.4. This represents the baseline increased risk of cancer conferred by JIA alone.

Nine malignancies occurred in the subgroup of children with JIA who took no medications. The SEER expectation among this group was 3.8 cancers, also translating to an SIR of 2.4

One malignancy occurred in the group treated with methotrexate only. Among these children, the SEER expected number was 1.9; the SIR in this group was 0.53.

Seven malignancies occurred among children who took TNF inhibitors, translating to an SIR of 2.9. Six occurred in children who took a TNF inhibitor in combination with or without methotrexate – an SIR of 3.0.

A final group consisted of children who took a wide range of other medications used in JIA (abatacept, anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, ustekinumab, tofacitinib, azathioprine, cyclosporine, gold, leflunomide, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, thalidomide, lenalidomide). This group also included patients who may or may not have taken methotrexate or a TNF inhibitor. Among these, there were four cancers when the SEER expected number was 0.7. This translated to an SIR of almost 6 – a surprising finding, Dr. Beukelman said. But since there were only four cancers and the group was exposed to so many different medications, it’s tough to know what that means, if anything, Dr. Beukelman said.

“There’s a lot to unpack here. The treatment paradigm for JIA is methotrexate followed by a TNF inhibitor if that’s ineffective. So these kids were on all of these more uncommon drugs,” suggesting that neither TNF inhibition nor methotrexate worked. “Some of these patients might actually have had systemic arthritis, Still’s disease, which is a completely separate thing, and we don’t know anything about the risk of malignancy in that. They might have an even higher rate of malignancies at baseline due to having worse disease, or uncontrolled inflammation. It is concerning, but I think it probably speaks to the fact that these patients are difficult to treat and probably at higher risk.”

Dr. Beukelman didn’t specifically break out the types and numbers of cancer, except to say that 3 of the 20 were lymphomas. The rest were leukemias and brain cancers – a finding that reflects the general pattern of childhood malignancies.

“Unfortunately, the most common childhood cancers are lymphomas, leukemias, and brain cancers, and that is what we saw in this study as well,” he said.

The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Beukelman noted that he has received consulting fees from Novartis, Genetech/Roche, and UCB.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors don’t appear to confer any additional cancer risk upon children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis above the increased incidence of cancer that comes hand in hand with the disease itself.

In 2009, the drugs came under suspicion of boosting the already-known increased cancer risk in these patients, Timothy G. Beukelman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. But the large database review that he conducted with his colleagues doesn’t validate those fears.

“I feel fairly confident now that I can stand in front of parents and say that we can treat their child effectively without putting that child at an even higher risk of a malignancy,” he said in a video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Thomas J.A. Lehman, MD, chief of pediatric rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and professor of clinical pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, agreed.

“This study again indicates that anti-TNF therapy does not increase the risk of cancer for children with arthritis,” he said in an interview. “Although children with rheumatic diseases have a small increased background risk of malignancies, this is independent of the use of anti-TNF therapies. For physicians who have cared for children in the era when we did not have anti-TNF therapies available, it is clear that any minor risks associated with these medications are far outweighed by their dramatic benefits.”

In the last few years, five large studies have found that children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) have a two- to sixfold increased malignancy risk, compared with the general pediatric population. However, only two of those studies included children taking TNF inhibitors, who comprised just 2% and 9% of those study populations.

In 2009, based on voluntary adverse event reporting, the Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning on TNF inhibitors, citing a possibly increased risk of cancer in children and adolescents who received the drugs for JIA, inflammatory bowel diseases, and other inflammatory diseases.

Shortly thereafter, a report identified a fivefold increase in the risk of childhood lymphoma associated with the medications (Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Aug;62[8]:2517-24). Other studies have not borne this out, but the boxed warning stands.

To further explore the association, Dr. Beukelman of the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and his associates examined billing data from two large national billing databases: the National U.S. Truven MarketScan claims database and Medicaid billing records. Together, the databases contained information on 27,000 children with JIA who received a prescription for a TNF inhibitor any time during 2000-2014. Cancer rates in this population were compared with those seen in a cohort of 2.64 million children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who were included in the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The investigators chose individuals with ADHD as a control group because of ADHD’s chronicity and lack of any association with cancer risk.

Dr. Beukelman also performed a within-group analysis on the JIA patients, comparing cancer rates among those treated with a TNF inhibitor and with methotrexate. The mean follow-up for patients who took TNF inhibitors was 4 years (median of 1.4 years), but there were a full 14 years of data for some patients.

Among the controls, with more than 4 million person-years of follow-up, there were 727 cases of any malignancy – a standardized incident rate (SIR) of 1.03. Among all children with JIA, with more than 52,000 person-years of follow-up, there were 20 malignancies. The SEER database predicted eight among a sex- and age-matched cohort of healthy children. This translated to an SIR of 2.4. This represents the baseline increased risk of cancer conferred by JIA alone.

Nine malignancies occurred in the subgroup of children with JIA who took no medications. The SEER expectation among this group was 3.8 cancers, also translating to an SIR of 2.4

One malignancy occurred in the group treated with methotrexate only. Among these children, the SEER expected number was 1.9; the SIR in this group was 0.53.

Seven malignancies occurred among children who took TNF inhibitors, translating to an SIR of 2.9. Six occurred in children who took a TNF inhibitor in combination with or without methotrexate – an SIR of 3.0.

A final group consisted of children who took a wide range of other medications used in JIA (abatacept, anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, ustekinumab, tofacitinib, azathioprine, cyclosporine, gold, leflunomide, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, thalidomide, lenalidomide). This group also included patients who may or may not have taken methotrexate or a TNF inhibitor. Among these, there were four cancers when the SEER expected number was 0.7. This translated to an SIR of almost 6 – a surprising finding, Dr. Beukelman said. But since there were only four cancers and the group was exposed to so many different medications, it’s tough to know what that means, if anything, Dr. Beukelman said.

“There’s a lot to unpack here. The treatment paradigm for JIA is methotrexate followed by a TNF inhibitor if that’s ineffective. So these kids were on all of these more uncommon drugs,” suggesting that neither TNF inhibition nor methotrexate worked. “Some of these patients might actually have had systemic arthritis, Still’s disease, which is a completely separate thing, and we don’t know anything about the risk of malignancy in that. They might have an even higher rate of malignancies at baseline due to having worse disease, or uncontrolled inflammation. It is concerning, but I think it probably speaks to the fact that these patients are difficult to treat and probably at higher risk.”

Dr. Beukelman didn’t specifically break out the types and numbers of cancer, except to say that 3 of the 20 were lymphomas. The rest were leukemias and brain cancers – a finding that reflects the general pattern of childhood malignancies.

“Unfortunately, the most common childhood cancers are lymphomas, leukemias, and brain cancers, and that is what we saw in this study as well,” he said.

The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Beukelman noted that he has received consulting fees from Novartis, Genetech/Roche, and UCB.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Children with JIA were about twice as likely to get cancer as the general population, regardless of whether they took a TNF inhibitor.

Data source: A database review comprising 27,000 patients and 2.5 million controls.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Beukelman noted that he has received consulting fees from Novartis, Genetech/Roche, and UCB.

Surgical Simulation in Orthopedic Surgery Residency

The training model for orthopedic resident education has been transformed. Surgeon factors, patient expectations, financial and legal concerns, associated costs, and work hour restrictions have put pressure on resident autonomy in the operating room.1,2 At the end of resident training, the expectation is that board-eligible surgeons will have the surgical skills necessary to perform a wide range of surgical procedures.3,4 Helping residents become proficient for independent practice requires a multidisciplinary approach.5 This approach, regardless of its details, requires investment in time, resources, expertise, and funding.

Many residency programs are trying to bridge the gap between observation and autonomy with surgical simulation. According to one study, 76% of residency programs have a surgical skills laboratory, and 46% have a structured surgical skills curriculum.6Surgical skills preparation is available in different modalities. Synthetic bones, virtual reality, and arthroscopic simulators represent potential opportunities for practice. Through these modalities, residents become more comfortable with the tools used in orthopedic procedures. Cadaveric dissection allows them to practice surgical approaches in the setting of real anatomy.1 Independent dissection helps them appreciate the planes, layers, and proximity of crucial body structures and understand important surgical anatomy.4Surgical simulation can be expensive, and funding comes in many forms. Cadaver laboratories require investment in specimens, facilities, and time away from clinical obligations.4 Cadaver availability varies with regional resources, and the cost of a cadaver ranges from $1000 to $2000.7,8 Arthroscopic simulators and virtual reality programs are expensive as well. These modalities range from a less expensive video box (with standard arthroscopic equipment) to a virtual reality haptic simulation costing a residency program as much as $80,000.9 Synthetic bone simulations are less expensive but require investment in faculty time and outside implants and instrumentation.10 The cost of simulation raises the question of funding sources.

Funding surgical simulation is a challenge. In a national survey of program directors, conducted by Karam and colleagues,6 87.3% of residencies cited lack of funding as the most significant barrier to a formal surgical skills program. Simulation can be residency-sponsored, industry-sponsored, or specialty-sponsored. Karam and colleagues6 found that department, hospital, and industry funding were the 3 main sponsors of surgical simulation. Each funding mechanism brings its own set of challenges and opportunities. Industry-sponsored simulation provides a cost-effective outlet for residency programs. However, this type of funding is under scrutiny, as industry funding for education becomes more transparent. In addition, industry funding typically limits the technology that can be used during the simulation to the sponsor’s technology. Courses offered by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and a number of subspecialty societies provide less conflicted simulation at reasonable cost.

If residents, residency programs, hospitals, industry, subspecialty societies, and the AAOS are going to invest in resident education through simulation, then the effect of simulation on resident education must be understood. Intuitively, simulation as a modality for improving resident skills makes sense. For residency programs to invest in simulation and surgical skills, different modalities must be objectively evaluated and their utility validated. If simulation is to become valuable, first it must be done correctly.

Kneebone11 proposed a framework for evaluating simulation. In this framework, simulation should allow for sustained, deliberate practice in a safe environment. It should provide access to expert tutors when appropriate. It should map onto real-life clinical experience. Last, it should provide a supportive, motivational, learner-centered milieu. Residents and program directors should consider this framework when deciding which simulation exercises to engage in and which resources to supply for exercises. Having supportive supervision during simulation can lead to a positive outcome. Likewise, learning incorrect techniques or bad habits or having inexperienced teachers can have the opposite effect.

Several authors have reviewed the evidence and found simulation to be an important part of orthopedic resident education.1,2,4,9,12,13 They have evaluated cadaveric simulation, synthetic bone simulation, arthroscopic simulation, and virtual reality simulation. Their studies demonstrated that simulation is an effective tool and provided objective criteria for evaluating residents on a larger scale. In a blinded, randomized study by Howells and colleagues,14 junior residents were either trained on a knee simulator or received no training before evaluation. Those who received the training scored significantly better than their peers on validated assessment measures.

The literature on different modalities shows simulation is an effective teaching tool for general orthopedic surgical skills5; knee, shoulder, and ankle arthroscopy14-21; spine surgery22; and orthopedic trauma surgery.23-26 Investigators in several other surgical specialties have studied the utility of simulation, and many are incorporating simulation into their resident curricula.

More effective simulation seems correlated with a yearlong structured curriculum rather than with intermittent, isolated experiences.3 Dunn and colleagues27 evaluated arthroscopic shoulder simulation 1 year after a training exercise. The group that received formal training did better than the control group on an initial arthroscopic surgery skill evaluation tool. At 1 year, however, the gains made through training were lost.

Simulation is a new paradigm for resident education. It offers multiple opportunities and challenges for residents, residency programs, industry partners, specialty and subspecialty societies, and medical examiners. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Orthopaedic Surgery requires of residency programs a didactic curriculum dedicated to basic motor skills in addition to a dedicated space for facilitating basic surgical skills training.28 Residency programs must demonstrate to ACGME their commitment to surgical skills training and simulation. Implementation of simulation for resident education has many variables, including funding, type of simulation, demonstrated efficacy, provision of supervision, resident time, and establishment of a formal curriculum. Residents and residency programs should embrace this changing paradigm to bridge the gap between observation and autonomy in orthopedic surgical and arthroscopic technique.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E426-E428. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Atesok K, Mabrey JD, Jazrawi LM, Egol KA. Surgical simulation in orthopaedic skills training. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(7):410-422.

2. Thomas GW, Johns BD, Marsh JL, Anderson DD. A review of the role of simulation in developing and assessing orthopaedic surgical skills. Iowa Orthop J. 2014;34:181-189.

3. Reznick RK, MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills—changes in the wind. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(25):2664-2669.

4. Holland JP, Waugh L, Horgan A, Paleri V, Deehan DJ. Cadaveric hands-on training for surgical specialties: is this back to the future for surgical skills development? J Surg Educ. 2011;68(2):110-116.

5. Sonnadara RR, Van Vliet A, Safir O, et al. Orthopedic boot camp: examining the effectiveness of an intensive surgical skills course. Surgery. 2011;149(6):745-749.

6. Karam MD, Pedowitz RA, Natividad H, Murray J, Marsh JL. Current and future use of surgical skills training laboratories in orthopaedic resident education: a national survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(1):e4.

7. Bushey C. Cadaver supply: the last industry to face big changes. Crain’s Chicago Business. February 23, 2013.

8. Human K. Cadaver shortage hits medical schools. Denver Post. April 29, 2008.

9. Michelson JD. Simulation in orthopaedic education: an overview of theory and practice. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1405-1411.

10. Elfar J, Menorca RM, Reed JD, Stanbury S. Composite bone models in orthopaedic surgery research and education. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(2):111-120.

11. Kneebone R. Evaluating clinical simulations for learning procedural skills: a theory-based approach. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):549-553.

12. Stirling ER, Lewis TL, Ferran NA. Surgical skills simulation in trauma and orthopaedic training. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:126.

13. Mabrey JD, Reinig KD, Cannon WD. Virtual reality in orthopaedics: is it a reality? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(10):2586-2591.

14. Howells NR, Gill HS, Carr AJ, Price AJ, Rees JL. Transferring simulated arthroscopic skills to the operating theatre: a randomised blinded study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):494-499.

15. Gomoll AH, O’Toole RV, Czarnecki J, Warner JJ. Surgical experience correlates with performance on a virtual reality simulator for shoulder arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(6):883-888.

16. Gomoll AH, Pappas G, Forsythe B, Warner JJ. Individual skill progression on a virtual reality simulator for shoulder arthroscopy: a 3-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1139-1142.

17. Pedowitz RA, Esch J, Snyder S. Evaluation of a virtual reality simulator for arthroscopy skills development. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(6):E29.

18. Martin KD, Belmont PJ, Schoenfeld AJ, Todd M, Cameron KL, Owens BD. Arthroscopic basic task performance in shoulder simulator model correlates with similar task performance in cadavers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):e1271-e1275.

19. Martin KD, Cameron K, Belmont PJ, Schoenfeld A, Owens BD. Shoulder arthroscopy simulator performance correlates with resident and shoulder arthroscopy experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(21):e160.

20. Martin KD, Patterson D, Phisitkul P, Cameron KL, Femino J, Amendola A. Ankle arthroscopy simulation improves basic skills, anatomic recognition, and proficiency during diagnostic examination of residents in training. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(7):827-835.

21. Frank RM, Erickson B, Frank JM, et al. Utility of modern arthroscopic simulator training models. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):121-133.

22. Rambani R, Ward J, Viant W. Desktop-based computer-assisted orthopedic training system for spinal surgery. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):805-809.

23. Leong JJ, Leff DR, Das A, et al. Validation of orthopaedic bench models for trauma surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(7):958-965.

24. Rambani R, Viant W, Ward J, Mohsen A. Computer-assisted orthopedic training system for fracture fixation. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(3):304-308.

25. Blyth P, Stott NS, Anderson IA. A simulation-based training system for hip fracture fixation for use within the hospital environment. Injury. 2007;38(10):1197-1203.

26. Egol KA, Phillips D, Vongbandith T, Szyld D, Strauss EJ. Do orthopaedic fracture skills courses improve resident performance? Injury. 2015;46(4):547-551.

27. Dunn JC, Belmont PJ, Lanzi J, et al. Arthroscopic shoulder surgical simulation training curriculum: transfer reliability and maintenance of skill over time. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1118-1123.

28. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Orthopaedic Surgery. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/260_orthopaedic_surgery_2016.pdf. Published July 1, 2012. Accessed September 30, 2016.

The training model for orthopedic resident education has been transformed. Surgeon factors, patient expectations, financial and legal concerns, associated costs, and work hour restrictions have put pressure on resident autonomy in the operating room.1,2 At the end of resident training, the expectation is that board-eligible surgeons will have the surgical skills necessary to perform a wide range of surgical procedures.3,4 Helping residents become proficient for independent practice requires a multidisciplinary approach.5 This approach, regardless of its details, requires investment in time, resources, expertise, and funding.

Many residency programs are trying to bridge the gap between observation and autonomy with surgical simulation. According to one study, 76% of residency programs have a surgical skills laboratory, and 46% have a structured surgical skills curriculum.6Surgical skills preparation is available in different modalities. Synthetic bones, virtual reality, and arthroscopic simulators represent potential opportunities for practice. Through these modalities, residents become more comfortable with the tools used in orthopedic procedures. Cadaveric dissection allows them to practice surgical approaches in the setting of real anatomy.1 Independent dissection helps them appreciate the planes, layers, and proximity of crucial body structures and understand important surgical anatomy.4Surgical simulation can be expensive, and funding comes in many forms. Cadaver laboratories require investment in specimens, facilities, and time away from clinical obligations.4 Cadaver availability varies with regional resources, and the cost of a cadaver ranges from $1000 to $2000.7,8 Arthroscopic simulators and virtual reality programs are expensive as well. These modalities range from a less expensive video box (with standard arthroscopic equipment) to a virtual reality haptic simulation costing a residency program as much as $80,000.9 Synthetic bone simulations are less expensive but require investment in faculty time and outside implants and instrumentation.10 The cost of simulation raises the question of funding sources.

Funding surgical simulation is a challenge. In a national survey of program directors, conducted by Karam and colleagues,6 87.3% of residencies cited lack of funding as the most significant barrier to a formal surgical skills program. Simulation can be residency-sponsored, industry-sponsored, or specialty-sponsored. Karam and colleagues6 found that department, hospital, and industry funding were the 3 main sponsors of surgical simulation. Each funding mechanism brings its own set of challenges and opportunities. Industry-sponsored simulation provides a cost-effective outlet for residency programs. However, this type of funding is under scrutiny, as industry funding for education becomes more transparent. In addition, industry funding typically limits the technology that can be used during the simulation to the sponsor’s technology. Courses offered by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and a number of subspecialty societies provide less conflicted simulation at reasonable cost.

If residents, residency programs, hospitals, industry, subspecialty societies, and the AAOS are going to invest in resident education through simulation, then the effect of simulation on resident education must be understood. Intuitively, simulation as a modality for improving resident skills makes sense. For residency programs to invest in simulation and surgical skills, different modalities must be objectively evaluated and their utility validated. If simulation is to become valuable, first it must be done correctly.

Kneebone11 proposed a framework for evaluating simulation. In this framework, simulation should allow for sustained, deliberate practice in a safe environment. It should provide access to expert tutors when appropriate. It should map onto real-life clinical experience. Last, it should provide a supportive, motivational, learner-centered milieu. Residents and program directors should consider this framework when deciding which simulation exercises to engage in and which resources to supply for exercises. Having supportive supervision during simulation can lead to a positive outcome. Likewise, learning incorrect techniques or bad habits or having inexperienced teachers can have the opposite effect.