User login

New HER2-testing guidelines result in more women eligible for HER2-directed treatment

New guidelines for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) pathology testing categorize more breast cancers as “equivocal” regarding HER2 positivity and ultimately lead to identifying more of them as HER2 positive, investigators reported online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists released updated IHC and FISH guidelines in 2013, after the Food and Drug Administration approved the initial set of such guidelines in 1998 and ASCO/CAP issued their first such guidelines in 2007. “The intent of the 2013 guidelines was to decrease the number of equivocal [cancers],” said Mithun Vinod Shah, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minn., and his associates.

To assess the impact of implementing the new guidelines, the investigators analyzed 2,851 breast cancer samples sent to their cytogenetics laboratory by 139 medical centers for HER2 testing during a 1-year period. They compared the three sets of testing criteria – the FDA, the 2007, and the 2013 guidelines.

According to the 2013 guidelines, 69.7% of the tumors were classified as HER2 negative, 16.1% as HER2 positive, and 14.2% as equivocal. In contrast, the 2007 guidelines classified 85.1% as negative, 11.0% as positive, and 3.9% as equivocal, while the FDA guidelines classified 13.1% as positive and 86.9% as negative (there is no “equivocal” category in the FDA guidelines). Thus, “the final FISH interpretations indicate that by using 2013 guidelines, 358 additional patients were interpreted as positive, compared with the 2007 guidelines and that 298 additional patients were considered positive, compared with the FDA criteria,” Dr. Shah and his associates said.

The 2013 guidelines recommend additional chromosome 17 probe testing (among other strategies) to resolve equivocal results, so the investigators did so with the 405 samples classified as equivocal by the 2013 criteria. This resulted in 52.3% of the 405 equivocal tumors being reclassified as HER2 positive, 8.9% being reclassified as HER2 negative, and 38.8% remaining equivocal. Thus, HER2 positivity in the overall cohort rose significantly to 23.6% using the newest guidelines.

These findings demonstrate that using the 2013 guidelines for IHC and FISH pathology testing identifies more women who are eligible for HER2-directed therapy, the investigators said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.8983).

New guidelines for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) pathology testing categorize more breast cancers as “equivocal” regarding HER2 positivity and ultimately lead to identifying more of them as HER2 positive, investigators reported online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists released updated IHC and FISH guidelines in 2013, after the Food and Drug Administration approved the initial set of such guidelines in 1998 and ASCO/CAP issued their first such guidelines in 2007. “The intent of the 2013 guidelines was to decrease the number of equivocal [cancers],” said Mithun Vinod Shah, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minn., and his associates.

To assess the impact of implementing the new guidelines, the investigators analyzed 2,851 breast cancer samples sent to their cytogenetics laboratory by 139 medical centers for HER2 testing during a 1-year period. They compared the three sets of testing criteria – the FDA, the 2007, and the 2013 guidelines.

According to the 2013 guidelines, 69.7% of the tumors were classified as HER2 negative, 16.1% as HER2 positive, and 14.2% as equivocal. In contrast, the 2007 guidelines classified 85.1% as negative, 11.0% as positive, and 3.9% as equivocal, while the FDA guidelines classified 13.1% as positive and 86.9% as negative (there is no “equivocal” category in the FDA guidelines). Thus, “the final FISH interpretations indicate that by using 2013 guidelines, 358 additional patients were interpreted as positive, compared with the 2007 guidelines and that 298 additional patients were considered positive, compared with the FDA criteria,” Dr. Shah and his associates said.

The 2013 guidelines recommend additional chromosome 17 probe testing (among other strategies) to resolve equivocal results, so the investigators did so with the 405 samples classified as equivocal by the 2013 criteria. This resulted in 52.3% of the 405 equivocal tumors being reclassified as HER2 positive, 8.9% being reclassified as HER2 negative, and 38.8% remaining equivocal. Thus, HER2 positivity in the overall cohort rose significantly to 23.6% using the newest guidelines.

These findings demonstrate that using the 2013 guidelines for IHC and FISH pathology testing identifies more women who are eligible for HER2-directed therapy, the investigators said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.8983).

New guidelines for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) pathology testing categorize more breast cancers as “equivocal” regarding HER2 positivity and ultimately lead to identifying more of them as HER2 positive, investigators reported online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists released updated IHC and FISH guidelines in 2013, after the Food and Drug Administration approved the initial set of such guidelines in 1998 and ASCO/CAP issued their first such guidelines in 2007. “The intent of the 2013 guidelines was to decrease the number of equivocal [cancers],” said Mithun Vinod Shah, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minn., and his associates.

To assess the impact of implementing the new guidelines, the investigators analyzed 2,851 breast cancer samples sent to their cytogenetics laboratory by 139 medical centers for HER2 testing during a 1-year period. They compared the three sets of testing criteria – the FDA, the 2007, and the 2013 guidelines.

According to the 2013 guidelines, 69.7% of the tumors were classified as HER2 negative, 16.1% as HER2 positive, and 14.2% as equivocal. In contrast, the 2007 guidelines classified 85.1% as negative, 11.0% as positive, and 3.9% as equivocal, while the FDA guidelines classified 13.1% as positive and 86.9% as negative (there is no “equivocal” category in the FDA guidelines). Thus, “the final FISH interpretations indicate that by using 2013 guidelines, 358 additional patients were interpreted as positive, compared with the 2007 guidelines and that 298 additional patients were considered positive, compared with the FDA criteria,” Dr. Shah and his associates said.

The 2013 guidelines recommend additional chromosome 17 probe testing (among other strategies) to resolve equivocal results, so the investigators did so with the 405 samples classified as equivocal by the 2013 criteria. This resulted in 52.3% of the 405 equivocal tumors being reclassified as HER2 positive, 8.9% being reclassified as HER2 negative, and 38.8% remaining equivocal. Thus, HER2 positivity in the overall cohort rose significantly to 23.6% using the newest guidelines.

These findings demonstrate that using the 2013 guidelines for IHC and FISH pathology testing identifies more women who are eligible for HER2-directed therapy, the investigators said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.8983).

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: New IHC and FISH pathology guidelines categorize more breast cancers as “equivocal” regarding HER2 positivity and ultimately lead to identifying more of them as HER2 positive.

Major finding: By using 2013 guidelines, 358 additional tumors were interpreted as positive, compared with the 2007 guidelines and 298 additional tumors were considered positive, compared with the FDA criteria.

Data source: A cohort study involving 2,851 breast cancer samples analyzed according to three different pathology guidelines during a 1-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Shah reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his associates reported ties to Merck, Hospira, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Abbott Molecular, and Genome Diagnostics.

Study shows faster increase in obesity prevalence among cancer survivors

From 1997 to 2014, cancer survivors had a significantly faster increase in obesity prevalence compared with adults without a history of cancer, investigators found.

Furthermore, the elevated annual increase in rates of obesity was more pronounced in women, in breast and colorectal cancer survivors, and in non-Hispanic blacks.

Cancer patients may be at an increased risk for weight gain caused by specific cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, steroid modifications, and various hormone therapies, especially in “hormonally and metabolically driven cancers such as breast and colorectal cancer,” wrote Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4391). “To better inform future research on obesity and cancer survival and to inform the planning and implementation of weight loss interventions in cancer survivors, we compared trends from 1997 to 2014 in obesity prevalence in U.S. adults with and without a history of cancer,” the researchers explained.

Obesity prevalence and trends were evaluated through the National Health Interview Survey, an ongoing cross-sectional survey of the health status, health care access, and behaviors of the U.S. civilian population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

For the current study, surveys from a total of 538,969 adults aged 18-85 years with (n = 32,447) or without (n = 506,522) a history of cancer were analyzed. Participants provided self-reported height and weight measures from which body mass index was calculated. Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher for non-Asians and 27.5 kg/m2 or higher for Asians. Participants also self-reported sex, race, and cancer history.

Overall, the prevalence of obesity consistently increased from 1997 to 2014. Among cancer survivors, the prevalence of obesity increased from 22.4% to 31.7% while in adults without a history of cancer, prevalence increased from 20.9% to 29.5%.

The annual increase in the rate of obesity was significantly greater in both women and men with a history of cancer (2.9% and 2.8% respectively) compared with those without a history of cancer (2.3% and 2.4%, P less than .001 for all).

The elevated annual increase in rates of obesity was even higher in colorectal (3.1% in women and 3.7% in men) and breast (3.0%) cancer survivors compared with adults without a history of cancer, but was lower in prostate cancer survivors (2.1%; P = .001 for all).

“These findings call for public health planning of effective and scalable weight management and control programs for cancer survivors, especially for breast and colorectal cancer survivors and for non-Hispanic blacks,” the investigators concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Greenlee and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles for EHE International.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

From 1997 to 2014, cancer survivors had a significantly faster increase in obesity prevalence compared with adults without a history of cancer, investigators found.

Furthermore, the elevated annual increase in rates of obesity was more pronounced in women, in breast and colorectal cancer survivors, and in non-Hispanic blacks.

Cancer patients may be at an increased risk for weight gain caused by specific cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, steroid modifications, and various hormone therapies, especially in “hormonally and metabolically driven cancers such as breast and colorectal cancer,” wrote Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4391). “To better inform future research on obesity and cancer survival and to inform the planning and implementation of weight loss interventions in cancer survivors, we compared trends from 1997 to 2014 in obesity prevalence in U.S. adults with and without a history of cancer,” the researchers explained.

Obesity prevalence and trends were evaluated through the National Health Interview Survey, an ongoing cross-sectional survey of the health status, health care access, and behaviors of the U.S. civilian population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

For the current study, surveys from a total of 538,969 adults aged 18-85 years with (n = 32,447) or without (n = 506,522) a history of cancer were analyzed. Participants provided self-reported height and weight measures from which body mass index was calculated. Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher for non-Asians and 27.5 kg/m2 or higher for Asians. Participants also self-reported sex, race, and cancer history.

Overall, the prevalence of obesity consistently increased from 1997 to 2014. Among cancer survivors, the prevalence of obesity increased from 22.4% to 31.7% while in adults without a history of cancer, prevalence increased from 20.9% to 29.5%.

The annual increase in the rate of obesity was significantly greater in both women and men with a history of cancer (2.9% and 2.8% respectively) compared with those without a history of cancer (2.3% and 2.4%, P less than .001 for all).

The elevated annual increase in rates of obesity was even higher in colorectal (3.1% in women and 3.7% in men) and breast (3.0%) cancer survivors compared with adults without a history of cancer, but was lower in prostate cancer survivors (2.1%; P = .001 for all).

“These findings call for public health planning of effective and scalable weight management and control programs for cancer survivors, especially for breast and colorectal cancer survivors and for non-Hispanic blacks,” the investigators concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Greenlee and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles for EHE International.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

From 1997 to 2014, cancer survivors had a significantly faster increase in obesity prevalence compared with adults without a history of cancer, investigators found.

Furthermore, the elevated annual increase in rates of obesity was more pronounced in women, in breast and colorectal cancer survivors, and in non-Hispanic blacks.

Cancer patients may be at an increased risk for weight gain caused by specific cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, steroid modifications, and various hormone therapies, especially in “hormonally and metabolically driven cancers such as breast and colorectal cancer,” wrote Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4391). “To better inform future research on obesity and cancer survival and to inform the planning and implementation of weight loss interventions in cancer survivors, we compared trends from 1997 to 2014 in obesity prevalence in U.S. adults with and without a history of cancer,” the researchers explained.

Obesity prevalence and trends were evaluated through the National Health Interview Survey, an ongoing cross-sectional survey of the health status, health care access, and behaviors of the U.S. civilian population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

For the current study, surveys from a total of 538,969 adults aged 18-85 years with (n = 32,447) or without (n = 506,522) a history of cancer were analyzed. Participants provided self-reported height and weight measures from which body mass index was calculated. Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher for non-Asians and 27.5 kg/m2 or higher for Asians. Participants also self-reported sex, race, and cancer history.

Overall, the prevalence of obesity consistently increased from 1997 to 2014. Among cancer survivors, the prevalence of obesity increased from 22.4% to 31.7% while in adults without a history of cancer, prevalence increased from 20.9% to 29.5%.

The annual increase in the rate of obesity was significantly greater in both women and men with a history of cancer (2.9% and 2.8% respectively) compared with those without a history of cancer (2.3% and 2.4%, P less than .001 for all).

The elevated annual increase in rates of obesity was even higher in colorectal (3.1% in women and 3.7% in men) and breast (3.0%) cancer survivors compared with adults without a history of cancer, but was lower in prostate cancer survivors (2.1%; P = .001 for all).

“These findings call for public health planning of effective and scalable weight management and control programs for cancer survivors, especially for breast and colorectal cancer survivors and for non-Hispanic blacks,” the investigators concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Greenlee and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles for EHE International.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cancer survivors had a significantly faster increase in obesity prevalence compared with adults without a history of cancer.

Major finding: The annual increase in the rate of obesity was significantly higher in both women and men with a history of cancer (2.9% and 2.8% respectively) compared with those without a history of cancer (2.3% and 2.4%, P less than .001 for all).

Data source: National Health Interview Survey responses from 538,969 adults aged 18-85 years with (n = 32,447) or without (n = 506,522) a history of cancer.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Greenlee and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles for EHE International.

Overweight, obesity increase risk of cardiotoxicity from anthracyclines

Being overweight or obese was significantly associated with a greater risk of developing cardiotoxicity among breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab, investigators found.

Anthracyclines, a class of anticancer agents widely used to treat many cancer types, have a known association with cardiotoxicity. Furthermore, people who are overweight or obese have an increased risk for developing cardiovascular diseases. The purpose of this study was to “explore in greater depth the influence of overweight and obesity as aggravating factors in the development of cardiotoxicity” specifically among patients who received anthracycline and/or trastuzumab as part of their cancer treatment and were therefore at increased risk of experiencing cardiac-related adverse events, wrote Charles Guenancia, MD, PhD, of University Hospital, Dijon Cedex, France, and his associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4846).

These results are from a meta-analysis of 15 published prospective or retrospective cohort studies that investigated or otherwise reported data on the association between overweight and/or obesity and cardiotoxicity resulting from anthracycline and/or trastuzumab use for treating localized or metastatic breast cancer. Together, the 15 studies represented a total of 8,745 breast cancer patients.

Overall, the mean rate of cardiotoxicity was 17% (95% confidence interval, 11%-25%). Patients treated with anthracyclines only (n = 3,898) had a mean rate of cardiotoxicity of 20% (95% CI, 5%-43%) while patients treated with trastuzumab with or without anthracyclines (n = 4,847) had a lower mean rate of cardiotoxicity at 16% (95% CI, 10%-24%).Paired meta-analysis revealed that overweight, defined as a body mass index score of 25 to 29.9, was associated with increased risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.83-1.58). Obesity, defined as a body mass index score of 30 or greater, was associated with a greater risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.47 (95% CI, 0.95-2.28).

The association between body mass index and the risk of cardiotoxicity did not differ significantly by drug regimen (anthracyclines alone or sequential anthracyclines and trastuzumab).

This study’s funding source was not listed. Dr. Guenancia and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles and/or receiving financial compensation from various companies.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Being overweight or obese was significantly associated with a greater risk of developing cardiotoxicity among breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab, investigators found.

Anthracyclines, a class of anticancer agents widely used to treat many cancer types, have a known association with cardiotoxicity. Furthermore, people who are overweight or obese have an increased risk for developing cardiovascular diseases. The purpose of this study was to “explore in greater depth the influence of overweight and obesity as aggravating factors in the development of cardiotoxicity” specifically among patients who received anthracycline and/or trastuzumab as part of their cancer treatment and were therefore at increased risk of experiencing cardiac-related adverse events, wrote Charles Guenancia, MD, PhD, of University Hospital, Dijon Cedex, France, and his associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4846).

These results are from a meta-analysis of 15 published prospective or retrospective cohort studies that investigated or otherwise reported data on the association between overweight and/or obesity and cardiotoxicity resulting from anthracycline and/or trastuzumab use for treating localized or metastatic breast cancer. Together, the 15 studies represented a total of 8,745 breast cancer patients.

Overall, the mean rate of cardiotoxicity was 17% (95% confidence interval, 11%-25%). Patients treated with anthracyclines only (n = 3,898) had a mean rate of cardiotoxicity of 20% (95% CI, 5%-43%) while patients treated with trastuzumab with or without anthracyclines (n = 4,847) had a lower mean rate of cardiotoxicity at 16% (95% CI, 10%-24%).Paired meta-analysis revealed that overweight, defined as a body mass index score of 25 to 29.9, was associated with increased risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.83-1.58). Obesity, defined as a body mass index score of 30 or greater, was associated with a greater risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.47 (95% CI, 0.95-2.28).

The association between body mass index and the risk of cardiotoxicity did not differ significantly by drug regimen (anthracyclines alone or sequential anthracyclines and trastuzumab).

This study’s funding source was not listed. Dr. Guenancia and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles and/or receiving financial compensation from various companies.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Being overweight or obese was significantly associated with a greater risk of developing cardiotoxicity among breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab, investigators found.

Anthracyclines, a class of anticancer agents widely used to treat many cancer types, have a known association with cardiotoxicity. Furthermore, people who are overweight or obese have an increased risk for developing cardiovascular diseases. The purpose of this study was to “explore in greater depth the influence of overweight and obesity as aggravating factors in the development of cardiotoxicity” specifically among patients who received anthracycline and/or trastuzumab as part of their cancer treatment and were therefore at increased risk of experiencing cardiac-related adverse events, wrote Charles Guenancia, MD, PhD, of University Hospital, Dijon Cedex, France, and his associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4846).

These results are from a meta-analysis of 15 published prospective or retrospective cohort studies that investigated or otherwise reported data on the association between overweight and/or obesity and cardiotoxicity resulting from anthracycline and/or trastuzumab use for treating localized or metastatic breast cancer. Together, the 15 studies represented a total of 8,745 breast cancer patients.

Overall, the mean rate of cardiotoxicity was 17% (95% confidence interval, 11%-25%). Patients treated with anthracyclines only (n = 3,898) had a mean rate of cardiotoxicity of 20% (95% CI, 5%-43%) while patients treated with trastuzumab with or without anthracyclines (n = 4,847) had a lower mean rate of cardiotoxicity at 16% (95% CI, 10%-24%).Paired meta-analysis revealed that overweight, defined as a body mass index score of 25 to 29.9, was associated with increased risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.83-1.58). Obesity, defined as a body mass index score of 30 or greater, was associated with a greater risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.47 (95% CI, 0.95-2.28).

The association between body mass index and the risk of cardiotoxicity did not differ significantly by drug regimen (anthracyclines alone or sequential anthracyclines and trastuzumab).

This study’s funding source was not listed. Dr. Guenancia and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles and/or receiving financial compensation from various companies.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Being overweight or obese was significantly associated with a greater risk of developing cardiotoxicity among breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline and/or trastuzumab.

Major finding: Being overweight was associated with increased risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.83-1.58). Obesity was associated with a greater risk of cardiotoxicity with an odds ratio of 1.47 (95% CI, 0.95-2.28).

Data source: A meta-analysis of 15 studies that investigated or otherwise reported data on the association between overweight and/or obesity and cardiotoxicity resulting from anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab use for treating breast cancer.

Disclosures: This study’s funding source was not identified. Dr. Guenancia and one other investigator reported serving in advisory roles and/or receiving financial compensation from various companies.

ASCO: Always screen cancer survivors for chronic pain

All adult cancer survivors should be screened for chronic pain at every visit, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s first clinical practice guideline for managing this patient population, published July 25 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

An estimated 14 million adults with a history of cancer are living in the United States alone, and the prevalence of chronic pain related to their malignancy is reported to be as high as 40%. Yet most health care providers “haven’t been trained to recognize or treat long-term pain associated with cancer,” Judith A. Paice, PhD, RN, said in a press statement accompanying the release of the new guideline.

Existing guidelines focus on the acute pain of cancer and its treatment, or on acute pain related to advanced cancer, said Dr. Paice, cochair of the expert panel that developed the guideline and research professor of hematology/oncology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The chronic pain addressed in the new guideline document can be related to the malignancy itself or to its treatment. Surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiation treatment, and stem-cell transplantation can induce dozens of pain-producing complications, including osteonecrosis, bone fractures, peripheral or central nerve damage, fistulas, lymphedema, arthralgias, and myelopathy. The pain can develop months or years after diagnosis, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life well after treatment is completed.

“This guideline will help clinicians identify pain early and develop comprehensive treatment plans using a broad range of approaches,” Dr. Paice said in the statement.

The panel that developed the guideline comprised experts in medical oncology, hematology, pain medicine, palliative care, hospice, radiation oncology, social work, rehabilitation, psychology, and anesthesiology. They performed a systematic review of the literature and based their recommendations on 35 meta-analyses, 9 randomized controlled trials, 19 comparative studies, and expert consensus.

Some key recommendations include the following:

• Screen all survivors of adult cancers for chronic pain using both a physical exam and an in-depth interview that covers physical, functional, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of pain, as well as the patient’s treatment history and comorbid conditions. The guideline includes a list of 36 common pain syndromes resulting from cancer treatments.

• Monitor patients at every visit for late-onset treatment effects that can produce pain, just as they are monitored for recurrent disease and secondary malignancy. Some cancer survivors may not recognize that their current pain is related to past disease or its treatments, or may consider it an untreatable complication that they have to endure.

• Consider the entire range of pain medicines – not just opioid analgesics – including NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and selected antidepressants and anticonvulsants with analgesic efficacy. The panel noted that some cancer survivors with chronic pain may benefit from other drugs, including muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockers, alpha-2 agonists, and neutraceuticals and botanicals. But they urged caution since the efficacy of these agents has not been fully established.

Consider nonmedical treatments such as physical, occupational, and recreation therapy; exercise; orthotics; ultrasound; massage; acupuncture; cognitive behavioral therapy; relaxation therapy; and TENS or other types of nerve stimulation.

Consider medical cannabis or cannabinoids as an adjuvant but not a first-line pain treatment, being sure to follow specific state regulations.

Consider a trial of opioids only for carefully selected patients who don’t respond to more conservative management. Weigh potential risks against benefits and employ universal precautions to minimize abuse and addiction, and be cautious in coprescribing other centrally-acting agents (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206).

The full clinical practice guideline and other clinical tools and resources are available at www.asco.org/chronic-pai-guideline.

The guideline development process was supported by ASCO. Dr. Paice reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates reported financial ties to industry sources.

All adult cancer survivors should be screened for chronic pain at every visit, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s first clinical practice guideline for managing this patient population, published July 25 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

An estimated 14 million adults with a history of cancer are living in the United States alone, and the prevalence of chronic pain related to their malignancy is reported to be as high as 40%. Yet most health care providers “haven’t been trained to recognize or treat long-term pain associated with cancer,” Judith A. Paice, PhD, RN, said in a press statement accompanying the release of the new guideline.

Existing guidelines focus on the acute pain of cancer and its treatment, or on acute pain related to advanced cancer, said Dr. Paice, cochair of the expert panel that developed the guideline and research professor of hematology/oncology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The chronic pain addressed in the new guideline document can be related to the malignancy itself or to its treatment. Surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiation treatment, and stem-cell transplantation can induce dozens of pain-producing complications, including osteonecrosis, bone fractures, peripheral or central nerve damage, fistulas, lymphedema, arthralgias, and myelopathy. The pain can develop months or years after diagnosis, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life well after treatment is completed.

“This guideline will help clinicians identify pain early and develop comprehensive treatment plans using a broad range of approaches,” Dr. Paice said in the statement.

The panel that developed the guideline comprised experts in medical oncology, hematology, pain medicine, palliative care, hospice, radiation oncology, social work, rehabilitation, psychology, and anesthesiology. They performed a systematic review of the literature and based their recommendations on 35 meta-analyses, 9 randomized controlled trials, 19 comparative studies, and expert consensus.

Some key recommendations include the following:

• Screen all survivors of adult cancers for chronic pain using both a physical exam and an in-depth interview that covers physical, functional, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of pain, as well as the patient’s treatment history and comorbid conditions. The guideline includes a list of 36 common pain syndromes resulting from cancer treatments.

• Monitor patients at every visit for late-onset treatment effects that can produce pain, just as they are monitored for recurrent disease and secondary malignancy. Some cancer survivors may not recognize that their current pain is related to past disease or its treatments, or may consider it an untreatable complication that they have to endure.

• Consider the entire range of pain medicines – not just opioid analgesics – including NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and selected antidepressants and anticonvulsants with analgesic efficacy. The panel noted that some cancer survivors with chronic pain may benefit from other drugs, including muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockers, alpha-2 agonists, and neutraceuticals and botanicals. But they urged caution since the efficacy of these agents has not been fully established.

Consider nonmedical treatments such as physical, occupational, and recreation therapy; exercise; orthotics; ultrasound; massage; acupuncture; cognitive behavioral therapy; relaxation therapy; and TENS or other types of nerve stimulation.

Consider medical cannabis or cannabinoids as an adjuvant but not a first-line pain treatment, being sure to follow specific state regulations.

Consider a trial of opioids only for carefully selected patients who don’t respond to more conservative management. Weigh potential risks against benefits and employ universal precautions to minimize abuse and addiction, and be cautious in coprescribing other centrally-acting agents (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206).

The full clinical practice guideline and other clinical tools and resources are available at www.asco.org/chronic-pai-guideline.

The guideline development process was supported by ASCO. Dr. Paice reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates reported financial ties to industry sources.

All adult cancer survivors should be screened for chronic pain at every visit, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s first clinical practice guideline for managing this patient population, published July 25 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

An estimated 14 million adults with a history of cancer are living in the United States alone, and the prevalence of chronic pain related to their malignancy is reported to be as high as 40%. Yet most health care providers “haven’t been trained to recognize or treat long-term pain associated with cancer,” Judith A. Paice, PhD, RN, said in a press statement accompanying the release of the new guideline.

Existing guidelines focus on the acute pain of cancer and its treatment, or on acute pain related to advanced cancer, said Dr. Paice, cochair of the expert panel that developed the guideline and research professor of hematology/oncology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The chronic pain addressed in the new guideline document can be related to the malignancy itself or to its treatment. Surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiation treatment, and stem-cell transplantation can induce dozens of pain-producing complications, including osteonecrosis, bone fractures, peripheral or central nerve damage, fistulas, lymphedema, arthralgias, and myelopathy. The pain can develop months or years after diagnosis, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life well after treatment is completed.

“This guideline will help clinicians identify pain early and develop comprehensive treatment plans using a broad range of approaches,” Dr. Paice said in the statement.

The panel that developed the guideline comprised experts in medical oncology, hematology, pain medicine, palliative care, hospice, radiation oncology, social work, rehabilitation, psychology, and anesthesiology. They performed a systematic review of the literature and based their recommendations on 35 meta-analyses, 9 randomized controlled trials, 19 comparative studies, and expert consensus.

Some key recommendations include the following:

• Screen all survivors of adult cancers for chronic pain using both a physical exam and an in-depth interview that covers physical, functional, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of pain, as well as the patient’s treatment history and comorbid conditions. The guideline includes a list of 36 common pain syndromes resulting from cancer treatments.

• Monitor patients at every visit for late-onset treatment effects that can produce pain, just as they are monitored for recurrent disease and secondary malignancy. Some cancer survivors may not recognize that their current pain is related to past disease or its treatments, or may consider it an untreatable complication that they have to endure.

• Consider the entire range of pain medicines – not just opioid analgesics – including NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and selected antidepressants and anticonvulsants with analgesic efficacy. The panel noted that some cancer survivors with chronic pain may benefit from other drugs, including muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockers, alpha-2 agonists, and neutraceuticals and botanicals. But they urged caution since the efficacy of these agents has not been fully established.

Consider nonmedical treatments such as physical, occupational, and recreation therapy; exercise; orthotics; ultrasound; massage; acupuncture; cognitive behavioral therapy; relaxation therapy; and TENS or other types of nerve stimulation.

Consider medical cannabis or cannabinoids as an adjuvant but not a first-line pain treatment, being sure to follow specific state regulations.

Consider a trial of opioids only for carefully selected patients who don’t respond to more conservative management. Weigh potential risks against benefits and employ universal precautions to minimize abuse and addiction, and be cautious in coprescribing other centrally-acting agents (J Clin Oncol. 2016 July 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206).

The full clinical practice guideline and other clinical tools and resources are available at www.asco.org/chronic-pai-guideline.

The guideline development process was supported by ASCO. Dr. Paice reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates reported financial ties to industry sources.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Screen all survivors of adult cancers for chronic pain at every visit.

Major finding: An estimated 14 million adults with a history of cancer are living in the United States alone, and the prevalence of chronic pain related to their malignancy is reported to be as high as 40%.

Data source: The first ASCO clinical practice guideline for managing chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers.

Disclosures: This work was supported by ASCO. Dr. Paice reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates reported financial ties to industry.

Cervical cancer screening: How our approach may change

› Screen for cervical cancer in women ages 21 to 29 using cytology alone every 3 years. For women ages 30 to 65, screening with a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing every 5 years is the preferred option. A

› Be aware of the alternative guideline proposed by several specialty organizations: All women ages 25 to 64 should receive primary HPV screening every 3 years with the FDA-approved HPV test. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

If the cervical cytology report you receive for a woman in her mid-20s is negative, how soon would you plan to repeat testing? Recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and other leading organizations advise a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing at specified intervals depending on a patient’s age. However, a study published in 2015 analyzed data from a statewide registry on provider behavior and found a wide array of screening intervals in practice and infrequent use of HPV testing.1 Clearly, adherence to published guidelines has been inconsistent.

Now, recommendations by several specialty groups are evolving based on newer evidence regarding HPV testing. These alternative guidelines recommend primary high-risk HPV testing for all women. This change is the topic of much national debate and is being researched for the USPSTF’s 2018 update on cervical cancer screening.

In this article, I review the USPSTF’s present recommendations and look ahead to how “best practices” for cervical cancer screening may be changing.

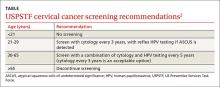

Current cervical cancer screening guidelines

Many subspecialty organizations and government agencies publish cervical cancer screening guidelines. The USPSTF guidelines, reviewed here, are evidence based, frequently updated, and widely used by primary care providers (TABLE).2,3 These guidelines recommend initiating cytology testing at age 21 and, if results are normal, repeating every 3 years. Reflex HPV testing is recommended if cytology results reveal atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). For women ages 30 to 65, the preferred option is to undergo a combination of cytology and HPV testing every 5 years.2 Women older than 65 may discontinue screening.2 HPV immunization status does not affect USPSTF recommendations. Nationwide rates of HPV vaccination among females ages 13 to 17 vary among states, from ≤49% to ≥70%.4

What the guidelines do, and do not, cover. The USPSTF screening intervals apply as long as testing results are normal.2 These guidelines apply to all women regardless of the age at which they began sexual activity. These guidelines do not apply to women who have had abnormal cytology or HPV results and have not undergone adequate follow-up to ensure their lesion has cleared.5 These guidelines also do not apply to women who are immunosuppressed, who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero, who have had a hysterectomy for non-oncologic reasons, or who have had cervical cancer.5 A woman may stop routine screening after age 65 if she has had adequate follow-up including either 3 negative cytology samples or 2 negative co-tests (cytology and HPV test) in the last 10 years.6 A woman may also discontinue screening if she has had a total hysterectomy and has no history of cervical dysplasia.7

Evidence behind the guidelines. The USPSTF guidelines were updated to their current state in 2012 reflecting a growing body of evidence that, for women 30 years and older, detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ lesions improves with HPV co-testing. The supporting studies also found that the risk of a high-grade lesion appearing 5 years following co-testing was equivalent to the risk seen with cytology samples alone taken at 3-year intervals.8 The sensitivity of a single cytology test is only about 50%.9 A patient’s risk of cervical cancer 18 months after 3 negative cytology tests is about 1.5/100,000.10 The risk at 36 months following 3 negative cytology results is about 4.5/100,000. Annual screening would require almost 100,000 women to be screened to detect 3 additional cases of cervical cancer.10

Additional benefits of the updated USPSTF guidelines. The updated strategy decreases the number of visits for patients and the number of colposcopies, minimizing harm and patient anxiety. The current management algorithms also recommend more conservative management of women in their early 20s who have reported abnormal cytology, as the likelihood of their lesion clearing within 12 to 24 months is high.5 The recommendation does not call for high-risk HPV testing of women ages 21 to 29 because the infection is highly prevalent in this age group and is also likely to clear before any significant pathology arises. This avoids unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment of younger women.11

What about the alternative screening guideline?

In early 2015, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) co-sponsored an expert panel representing several specialty societies. The panel released interim guidelines for cervical cancer screening reflecting a growing body of evidence that favors HPV testing as the primary modality.12 Additionally, in January 2016, these guidelines received an evidence-level B rating from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.13 Primary HPV screening is also the topic of research and discussion for USPSTF’s pending 2018 update of cervical cancer screening strategies.14

The alternative algorithm from the ASCCP and SGO recommends cervical cancer screening with HPV testing alone starting at the age of 25 and, if results are negative, repeating at 3-year intervals.12 If a patient tests positive for any of the 14 identified high-risk HPV types, reflex cytology is indicated with a referral for colposcopy if an abnormality is identified.12 If the cytology result is normal, follow-up with another HPV test in 12 months is recommended.12

Over the last 12 years, multiple international studies have demonstrated the efficacy of high-risk HPV testing in primary screening for cervical cancer.15 The most recent study conducted in the United States from 2008 to 2011—Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA)—enrolled 42,000 women older than 25 years to compare the screening modalities of cytology alone, cytology and HPV testing combined, and HPV testing alone.16 The purpose of the study was to determine the safety of the cobas HPV test as a co-test and as a primary screening modality in women older than 25 years. (Many HPV tests are commercially available, but only the cobas HPV test is FDA-approved for primary screening.12)

ATHENA researchers concluded that HPV testing was more sensitive than cytology, but less specific.16 The researchers also concluded that adding cytology to the HPV test increased the sensitivity by less than 5% and that HPV was better at detecting CIN 2+ lesions than cytology alone.12,16 Another recently published study conducted at a tertiary care hospital with a smaller sample (1000 patients) corroborated the ATHENA results.17

For patients in their late 20s, this alternative strategy may increase the number of subsequent colposcopies. However, during the clinical trials just described, the absolute number of colposcopies needed to detect high-grade disease was the same as seen with the current guidelines. This finding indicates that, with the current algorithm, clinically significant pathology due to high-risk HPV may be missed in the 25-to-29 age group.8

Looking ahead. The alternative screening strategy is already being adopted in Australia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.15 For providers in the United States considering this alternative strategy, the recommendation is to initiate cervical cancer screening with cytology alone at age 21, manage results appropriately, and then transition the patient to primary HPV testing with the FDA-approved test at age 25.12 This recommendation may be modified in the future. However the guidelines might change, patients will benefit only if the guidelines are implemented consistently in practice.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sabrina Hofmeister, DO, 1121 E. North Ave, Milwaukee, WI 53212; shofmeister@mcw.edu.

1. Kim JJ, Campos NG, Sy S, et al. Inefficiencies and high-value improvements in U.S. cervical cancer screening practice: a cost-effective analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:589-597.

2. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:880-891.

3. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Understanding How the USPSTF Works: USPSTF 101. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/understanding-how-the-uspstf-works. Accessed June 8, 2016.

4. Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, regional, state, and selected local vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:784-792.

5. Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:175-204.

6. Vesco KK, Whitlock EP, Eder M, et al. Risk factors and other epidemiologic considerations for cervical cancer screening: a narrative review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:687-697.

7. Khan MJ, Massad LS, Kinney W, et al. A common clinical dilemma: management of abnormal vaginal cytology and human papilloma virus test results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:119-125.

8. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197.

9. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589-1597.

10. Sawaya GF, Sung HY, Kinney W, et al. Cervical cancer after multiple negative tests in long-term members of a prepaid health plan. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:391-397.

11. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813-819.

12. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk HPV testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2015;19:91-96.

13. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 157: Cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e1-e20.

14. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Research Plan: Cervical Cancer: Screening. October 2015. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/final-research-plan/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed June 22, 2016.

15. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al; International HPV Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

16. Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, et al. High-risk human papilloma virus testing in women with ASC-US cytology: results from the ATHENA HPV study. Am J Clin Path. 2011;135:468-475.

17. Choi JW, Kim Y, Lee JH, et al. The clinical performance of primary HPV screening, primary HPV screening plus cytology cotesting, and cytology alone at a tertiary care hospital. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:144-152.

› Screen for cervical cancer in women ages 21 to 29 using cytology alone every 3 years. For women ages 30 to 65, screening with a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing every 5 years is the preferred option. A

› Be aware of the alternative guideline proposed by several specialty organizations: All women ages 25 to 64 should receive primary HPV screening every 3 years with the FDA-approved HPV test. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

If the cervical cytology report you receive for a woman in her mid-20s is negative, how soon would you plan to repeat testing? Recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and other leading organizations advise a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing at specified intervals depending on a patient’s age. However, a study published in 2015 analyzed data from a statewide registry on provider behavior and found a wide array of screening intervals in practice and infrequent use of HPV testing.1 Clearly, adherence to published guidelines has been inconsistent.

Now, recommendations by several specialty groups are evolving based on newer evidence regarding HPV testing. These alternative guidelines recommend primary high-risk HPV testing for all women. This change is the topic of much national debate and is being researched for the USPSTF’s 2018 update on cervical cancer screening.

In this article, I review the USPSTF’s present recommendations and look ahead to how “best practices” for cervical cancer screening may be changing.

Current cervical cancer screening guidelines

Many subspecialty organizations and government agencies publish cervical cancer screening guidelines. The USPSTF guidelines, reviewed here, are evidence based, frequently updated, and widely used by primary care providers (TABLE).2,3 These guidelines recommend initiating cytology testing at age 21 and, if results are normal, repeating every 3 years. Reflex HPV testing is recommended if cytology results reveal atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). For women ages 30 to 65, the preferred option is to undergo a combination of cytology and HPV testing every 5 years.2 Women older than 65 may discontinue screening.2 HPV immunization status does not affect USPSTF recommendations. Nationwide rates of HPV vaccination among females ages 13 to 17 vary among states, from ≤49% to ≥70%.4

What the guidelines do, and do not, cover. The USPSTF screening intervals apply as long as testing results are normal.2 These guidelines apply to all women regardless of the age at which they began sexual activity. These guidelines do not apply to women who have had abnormal cytology or HPV results and have not undergone adequate follow-up to ensure their lesion has cleared.5 These guidelines also do not apply to women who are immunosuppressed, who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero, who have had a hysterectomy for non-oncologic reasons, or who have had cervical cancer.5 A woman may stop routine screening after age 65 if she has had adequate follow-up including either 3 negative cytology samples or 2 negative co-tests (cytology and HPV test) in the last 10 years.6 A woman may also discontinue screening if she has had a total hysterectomy and has no history of cervical dysplasia.7

Evidence behind the guidelines. The USPSTF guidelines were updated to their current state in 2012 reflecting a growing body of evidence that, for women 30 years and older, detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ lesions improves with HPV co-testing. The supporting studies also found that the risk of a high-grade lesion appearing 5 years following co-testing was equivalent to the risk seen with cytology samples alone taken at 3-year intervals.8 The sensitivity of a single cytology test is only about 50%.9 A patient’s risk of cervical cancer 18 months after 3 negative cytology tests is about 1.5/100,000.10 The risk at 36 months following 3 negative cytology results is about 4.5/100,000. Annual screening would require almost 100,000 women to be screened to detect 3 additional cases of cervical cancer.10

Additional benefits of the updated USPSTF guidelines. The updated strategy decreases the number of visits for patients and the number of colposcopies, minimizing harm and patient anxiety. The current management algorithms also recommend more conservative management of women in their early 20s who have reported abnormal cytology, as the likelihood of their lesion clearing within 12 to 24 months is high.5 The recommendation does not call for high-risk HPV testing of women ages 21 to 29 because the infection is highly prevalent in this age group and is also likely to clear before any significant pathology arises. This avoids unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment of younger women.11

What about the alternative screening guideline?

In early 2015, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) co-sponsored an expert panel representing several specialty societies. The panel released interim guidelines for cervical cancer screening reflecting a growing body of evidence that favors HPV testing as the primary modality.12 Additionally, in January 2016, these guidelines received an evidence-level B rating from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.13 Primary HPV screening is also the topic of research and discussion for USPSTF’s pending 2018 update of cervical cancer screening strategies.14

The alternative algorithm from the ASCCP and SGO recommends cervical cancer screening with HPV testing alone starting at the age of 25 and, if results are negative, repeating at 3-year intervals.12 If a patient tests positive for any of the 14 identified high-risk HPV types, reflex cytology is indicated with a referral for colposcopy if an abnormality is identified.12 If the cytology result is normal, follow-up with another HPV test in 12 months is recommended.12

Over the last 12 years, multiple international studies have demonstrated the efficacy of high-risk HPV testing in primary screening for cervical cancer.15 The most recent study conducted in the United States from 2008 to 2011—Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA)—enrolled 42,000 women older than 25 years to compare the screening modalities of cytology alone, cytology and HPV testing combined, and HPV testing alone.16 The purpose of the study was to determine the safety of the cobas HPV test as a co-test and as a primary screening modality in women older than 25 years. (Many HPV tests are commercially available, but only the cobas HPV test is FDA-approved for primary screening.12)

ATHENA researchers concluded that HPV testing was more sensitive than cytology, but less specific.16 The researchers also concluded that adding cytology to the HPV test increased the sensitivity by less than 5% and that HPV was better at detecting CIN 2+ lesions than cytology alone.12,16 Another recently published study conducted at a tertiary care hospital with a smaller sample (1000 patients) corroborated the ATHENA results.17

For patients in their late 20s, this alternative strategy may increase the number of subsequent colposcopies. However, during the clinical trials just described, the absolute number of colposcopies needed to detect high-grade disease was the same as seen with the current guidelines. This finding indicates that, with the current algorithm, clinically significant pathology due to high-risk HPV may be missed in the 25-to-29 age group.8

Looking ahead. The alternative screening strategy is already being adopted in Australia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.15 For providers in the United States considering this alternative strategy, the recommendation is to initiate cervical cancer screening with cytology alone at age 21, manage results appropriately, and then transition the patient to primary HPV testing with the FDA-approved test at age 25.12 This recommendation may be modified in the future. However the guidelines might change, patients will benefit only if the guidelines are implemented consistently in practice.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sabrina Hofmeister, DO, 1121 E. North Ave, Milwaukee, WI 53212; shofmeister@mcw.edu.

› Screen for cervical cancer in women ages 21 to 29 using cytology alone every 3 years. For women ages 30 to 65, screening with a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing every 5 years is the preferred option. A

› Be aware of the alternative guideline proposed by several specialty organizations: All women ages 25 to 64 should receive primary HPV screening every 3 years with the FDA-approved HPV test. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

If the cervical cytology report you receive for a woman in her mid-20s is negative, how soon would you plan to repeat testing? Recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and other leading organizations advise a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing at specified intervals depending on a patient’s age. However, a study published in 2015 analyzed data from a statewide registry on provider behavior and found a wide array of screening intervals in practice and infrequent use of HPV testing.1 Clearly, adherence to published guidelines has been inconsistent.

Now, recommendations by several specialty groups are evolving based on newer evidence regarding HPV testing. These alternative guidelines recommend primary high-risk HPV testing for all women. This change is the topic of much national debate and is being researched for the USPSTF’s 2018 update on cervical cancer screening.

In this article, I review the USPSTF’s present recommendations and look ahead to how “best practices” for cervical cancer screening may be changing.

Current cervical cancer screening guidelines

Many subspecialty organizations and government agencies publish cervical cancer screening guidelines. The USPSTF guidelines, reviewed here, are evidence based, frequently updated, and widely used by primary care providers (TABLE).2,3 These guidelines recommend initiating cytology testing at age 21 and, if results are normal, repeating every 3 years. Reflex HPV testing is recommended if cytology results reveal atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). For women ages 30 to 65, the preferred option is to undergo a combination of cytology and HPV testing every 5 years.2 Women older than 65 may discontinue screening.2 HPV immunization status does not affect USPSTF recommendations. Nationwide rates of HPV vaccination among females ages 13 to 17 vary among states, from ≤49% to ≥70%.4

What the guidelines do, and do not, cover. The USPSTF screening intervals apply as long as testing results are normal.2 These guidelines apply to all women regardless of the age at which they began sexual activity. These guidelines do not apply to women who have had abnormal cytology or HPV results and have not undergone adequate follow-up to ensure their lesion has cleared.5 These guidelines also do not apply to women who are immunosuppressed, who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero, who have had a hysterectomy for non-oncologic reasons, or who have had cervical cancer.5 A woman may stop routine screening after age 65 if she has had adequate follow-up including either 3 negative cytology samples or 2 negative co-tests (cytology and HPV test) in the last 10 years.6 A woman may also discontinue screening if she has had a total hysterectomy and has no history of cervical dysplasia.7

Evidence behind the guidelines. The USPSTF guidelines were updated to their current state in 2012 reflecting a growing body of evidence that, for women 30 years and older, detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ lesions improves with HPV co-testing. The supporting studies also found that the risk of a high-grade lesion appearing 5 years following co-testing was equivalent to the risk seen with cytology samples alone taken at 3-year intervals.8 The sensitivity of a single cytology test is only about 50%.9 A patient’s risk of cervical cancer 18 months after 3 negative cytology tests is about 1.5/100,000.10 The risk at 36 months following 3 negative cytology results is about 4.5/100,000. Annual screening would require almost 100,000 women to be screened to detect 3 additional cases of cervical cancer.10

Additional benefits of the updated USPSTF guidelines. The updated strategy decreases the number of visits for patients and the number of colposcopies, minimizing harm and patient anxiety. The current management algorithms also recommend more conservative management of women in their early 20s who have reported abnormal cytology, as the likelihood of their lesion clearing within 12 to 24 months is high.5 The recommendation does not call for high-risk HPV testing of women ages 21 to 29 because the infection is highly prevalent in this age group and is also likely to clear before any significant pathology arises. This avoids unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment of younger women.11

What about the alternative screening guideline?

In early 2015, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) co-sponsored an expert panel representing several specialty societies. The panel released interim guidelines for cervical cancer screening reflecting a growing body of evidence that favors HPV testing as the primary modality.12 Additionally, in January 2016, these guidelines received an evidence-level B rating from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.13 Primary HPV screening is also the topic of research and discussion for USPSTF’s pending 2018 update of cervical cancer screening strategies.14

The alternative algorithm from the ASCCP and SGO recommends cervical cancer screening with HPV testing alone starting at the age of 25 and, if results are negative, repeating at 3-year intervals.12 If a patient tests positive for any of the 14 identified high-risk HPV types, reflex cytology is indicated with a referral for colposcopy if an abnormality is identified.12 If the cytology result is normal, follow-up with another HPV test in 12 months is recommended.12

Over the last 12 years, multiple international studies have demonstrated the efficacy of high-risk HPV testing in primary screening for cervical cancer.15 The most recent study conducted in the United States from 2008 to 2011—Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA)—enrolled 42,000 women older than 25 years to compare the screening modalities of cytology alone, cytology and HPV testing combined, and HPV testing alone.16 The purpose of the study was to determine the safety of the cobas HPV test as a co-test and as a primary screening modality in women older than 25 years. (Many HPV tests are commercially available, but only the cobas HPV test is FDA-approved for primary screening.12)

ATHENA researchers concluded that HPV testing was more sensitive than cytology, but less specific.16 The researchers also concluded that adding cytology to the HPV test increased the sensitivity by less than 5% and that HPV was better at detecting CIN 2+ lesions than cytology alone.12,16 Another recently published study conducted at a tertiary care hospital with a smaller sample (1000 patients) corroborated the ATHENA results.17

For patients in their late 20s, this alternative strategy may increase the number of subsequent colposcopies. However, during the clinical trials just described, the absolute number of colposcopies needed to detect high-grade disease was the same as seen with the current guidelines. This finding indicates that, with the current algorithm, clinically significant pathology due to high-risk HPV may be missed in the 25-to-29 age group.8

Looking ahead. The alternative screening strategy is already being adopted in Australia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.15 For providers in the United States considering this alternative strategy, the recommendation is to initiate cervical cancer screening with cytology alone at age 21, manage results appropriately, and then transition the patient to primary HPV testing with the FDA-approved test at age 25.12 This recommendation may be modified in the future. However the guidelines might change, patients will benefit only if the guidelines are implemented consistently in practice.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sabrina Hofmeister, DO, 1121 E. North Ave, Milwaukee, WI 53212; shofmeister@mcw.edu.

1. Kim JJ, Campos NG, Sy S, et al. Inefficiencies and high-value improvements in U.S. cervical cancer screening practice: a cost-effective analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:589-597.

2. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:880-891.

3. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Understanding How the USPSTF Works: USPSTF 101. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/understanding-how-the-uspstf-works. Accessed June 8, 2016.

4. Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, regional, state, and selected local vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:784-792.

5. Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:175-204.

6. Vesco KK, Whitlock EP, Eder M, et al. Risk factors and other epidemiologic considerations for cervical cancer screening: a narrative review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:687-697.

7. Khan MJ, Massad LS, Kinney W, et al. A common clinical dilemma: management of abnormal vaginal cytology and human papilloma virus test results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:119-125.

8. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197.

9. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589-1597.

10. Sawaya GF, Sung HY, Kinney W, et al. Cervical cancer after multiple negative tests in long-term members of a prepaid health plan. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:391-397.

11. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813-819.

12. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk HPV testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2015;19:91-96.

13. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 157: Cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e1-e20.

14. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Research Plan: Cervical Cancer: Screening. October 2015. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/final-research-plan/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed June 22, 2016.

15. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al; International HPV Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

16. Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, et al. High-risk human papilloma virus testing in women with ASC-US cytology: results from the ATHENA HPV study. Am J Clin Path. 2011;135:468-475.

17. Choi JW, Kim Y, Lee JH, et al. The clinical performance of primary HPV screening, primary HPV screening plus cytology cotesting, and cytology alone at a tertiary care hospital. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:144-152.

1. Kim JJ, Campos NG, Sy S, et al. Inefficiencies and high-value improvements in U.S. cervical cancer screening practice: a cost-effective analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:589-597.

2. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:880-891.

3. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Understanding How the USPSTF Works: USPSTF 101. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/understanding-how-the-uspstf-works. Accessed June 8, 2016.

4. Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, regional, state, and selected local vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:784-792.

5. Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:175-204.

6. Vesco KK, Whitlock EP, Eder M, et al. Risk factors and other epidemiologic considerations for cervical cancer screening: a narrative review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:687-697.

7. Khan MJ, Massad LS, Kinney W, et al. A common clinical dilemma: management of abnormal vaginal cytology and human papilloma virus test results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:119-125.

8. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197.

9. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589-1597.

10. Sawaya GF, Sung HY, Kinney W, et al. Cervical cancer after multiple negative tests in long-term members of a prepaid health plan. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:391-397.

11. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813-819.

12. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk HPV testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2015;19:91-96.

13. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 157: Cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e1-e20.

14. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Research Plan: Cervical Cancer: Screening. October 2015. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/final-research-plan/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed June 22, 2016.

15. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al; International HPV Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

16. Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, et al. High-risk human papilloma virus testing in women with ASC-US cytology: results from the ATHENA HPV study. Am J Clin Path. 2011;135:468-475.

17. Choi JW, Kim Y, Lee JH, et al. The clinical performance of primary HPV screening, primary HPV screening plus cytology cotesting, and cytology alone at a tertiary care hospital. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:144-152.

The drive to cut readmissions after bariatric surgery continues with DROP project

SAN DIEGO – John Morton, MD, started his bariatric surgery career about the same time that demand for gastric bypass and other bariatric procedures began to skyrocket. But a troubling trend emerged.

“About 10-15 years ago, bariatric surgery had a problem when it came to mortality,” Dr. Morton said at the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference. “You can’t move forward without looking back.”

A 2005 study of early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric procedures found a 30-day mortality of 9% and a 1-year mortality of 21% (JAMA 2005 Oct. 19;294[15]:1903-8). Such data prompted Dr. Morton and other leaders in the field to push for accreditation in the field. In 2012, the ACS Bariatric Surgery Center Network program and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) Bariatric Centers of Excellence program were extended accreditation in the joint Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP). As a result, the mortality rate among patients undergoing bariatric procedures has dropped nearly 10-fold and now stands at 1 out of 1,000, said Dr. Morton, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. “That’s been a real success story for us,” he said. “Part of it has been the accreditation program, having the resources in place to accomplish those goals.”

Of the 802 participating centers in MBSAQIP, 647 are accredited. “One of the reasons we see such good results at accredited centers is the fact that they work as a multidisciplinary team, where you have the nutritionist, the psychologist, the internist, and the anesthesiologist working together,” said Dr. Morton, immediate past president of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “When you have that team, it allows you to marshal your resources, do appropriate risk assessment, and get those processes in place to have the very best outcomes.”

In an effort to reduce hospital readmissions among bariatric surgery patients, MBSAQIP launched a national project called Decreasing Readmissions through Opportunities Provided (DROP), which currently has 129 participating hospitals. “If you drill down on the reasons for bariatric surgery readmissions, many are preventable: dehydration, nausea, medication side effects, and patient expectations,” Dr. Morton said. “I have a formula called the Morton Formula: happiness equals reality divided by expectations. If you set expectations accordingly, you’ll get a happier patient. If my patients know they’re going to be discharged in 1 day, they can plan accordingly.”