User login

An 85-year-old woman with respiratory failure and positional hypoxemia

An 85-year-old woman was brought to our intensive care unit because of worsening hypoxemia over the past day. About 3 weeks earlier she had been diagnosed with acute bilateral pulmonary emboli in the distal branches of the left and right lower lobes and right middle lobe, for which she was receiving anticoagulation therapy.

At presentation she had generalized fatigue and dyspnea at rest that was worse with exertion, but she denied having fever, chest pain, or cough. Her medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, stage 1 breast cancer in remission, thromboembolic stroke, and myasthenia gravis. Before her hospital admission, she had been taking rosuvastatin, metoprolol tartrate, pyridostigmine, prednisone, furosemide, levothyroxine, and rivaroxaban. She did not smoke, she was retired, and she had not traveled recently.

Her blood pressure was 135/66 mm Hg, pulse 73 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16, temperature 35.4ºC (95.7ºF), and oxygen saturation 88% while receiving oxygen at 6 L/min via nasal cannula. Physical examination revealed mild edema in the lower extremities and basilar decreased breath sounds. She had no finger clubbing or cyanosis and was not using accessory muscles to breathe. Of note, her oxygen saturation remained more than 93% when she was recumbent but sharply dropped to less than 85% when she was upright.

Laboratory values

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 138 mmol/L (reference range 132–148)

- Potassium 4.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Chloride 99 mmol/L (98–111)

- Bicarbonate 29 mmol/L (23–32)

- Creatinine 0.52 mg/dL (0.7–1.4).

- White blood cell count 11.06 × 109/L (3.7–11.0)

- Hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL (12–16)

- Platelet count 211 × 109/L (150–400).

- International normalized ratio 1.4.

Electrocardiography and imaging studies

Standard 12-lead electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm with left axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Chest radiography showed bilateral interstitial opacities and small pleural effusions.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast, compared with a CT scan done 20 days earlier, showed that the pulmonary emboli had resolved.

Arterial blood gases

In view of her positional hypoxemia, blood for arterial blood gas measurements was drawn in the supine and upright positions.

Supine, with a fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) via high-flow nasal cannula of 45%, her values were:

- pH 7.45 (reference range 7.35–7.45)

- Pco2 34 mm Hg (36–46)

- Po2 81 mm Hg (85–95)

- Bicarbonate 23 mmol/L (22–26).

Upright, her hypoxemia was significantly worse:

- pH 7.46

- Pco2 33 mm Hg

- Po2 57 mm Hg

- Bicarbonate 23 mmol/L.

The methemoglobin level was normal on both measurements.

During her stay in the intensive care unit, she required up to 100% Fio2 because of persistent hypoxemia.

CAUSES OF HYPOXEMIA

1. So far, the patient’s laboratory tests and imaging studies point to which of the following as the most likely cause of her severe hypoxemia?

- Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch

- Diffusion abnormality

- Hypoventilation

- Shunting

- None of the above

The arterial blood gas measurements suggested the possibility of shunting as the cause, although further imaging would be needed to confirm that.

V/Q mismatch can occur in respiratory failure due to pulmonary embolism, pulmonary edema, or shunting. If ventilation is preserved but perfusion is impaired, the V/Q ratio approaches infinity (dead-space ventilation), a situation that can be seen in pulmonary embolism. If perfusion is preserved and ventilation is impaired, the V/Q ratio approaches zero, which is consistent with a physiologic shunt.

Hypoxemia may improve in less severe forms of V/Q mismatch. In our patient, the repeat CT with contrast showed that her pulmonary embolism had resolved, so this is probably not the cause of her severe hypoxemia.

Diffusion abnormalities are due to defects in the lung parenchyma, such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, and lung fibrosis.

Hypoxemia from diffusion defects is usually aggravated by a precipitating factor that increases oxygen demand, and it usually improves with oxygen supplementation. This is unlikely in our patient, as she did not have a history of chronic interstitial lung disease and CT showed no evidence of severe lung parenchymal disease.

Hypoventilation is usually due to drugs that cause respiratory depression, to stroke, or to neuromuscular diseases such as myasthenia gravis that can cause respiratory muscle weakness. It results in elevation of Pco2 and, if not corrected, respiratory acidosis.

Our patient had a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis, though hypoventilation is unlikely in her case because she had a normal respiratory rate and low Pco2 values.

Shunting can be physiologic or anatomic and can occur in the heart or the lungs. In physiologic shunting, severe V/Q mismatch can occur when ventilation is affected, as in severe pulmonary edema and pneumonia. In anatomic shunting, a defect such as an atrial septal defect or a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation allows blood to bypass areas of ventilation from the venous to the arterial circulation, preventing it from being oxygenated. In true anatomic shunting, supplemental oxygen with 100% Fio2 has little effect, whereas in V/Q mismatch it can raise the arterial oxygen saturation.

Our patient’s radiograph did not suggest severe pneumonia or pulmonary edema, which makes these unlikely causes of her hypoxemia. At this point, because of her positional hypoxemia, further evaluation with contrast-enhanced echocardiography was needed to evaluate for anatomic shunting in the heart or lungs.

FURTHER TESTING

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with agitated saline with a Valsalva maneuver was performed. Normally, no bubbles are seen in the left-sided chambers after intravenous injection of agitated saline contrast, whereas bubbles on the left side suggest an intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt. In our patient, this test was negative, and her right ventricular systolic pressure was normal.

2. What further testing should be considered to evaluate our patient’s hypoxemia?

- High-resolution chest CT

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

- Pulmonary function testing

- Repeated arterial blood gas measurement

- Edrophonium testing

Repeat imaging with high-resolution CT would likely not provide additional information and would expose the patient to additional radiation without adding much clinical benefit.

TEE could help further evaluate the intracardiac anatomy and look for shunting, which may be missed on TTE because of suboptimal positioning or image quality.

Pulmonary function testing is useful in establishing the baseline function and impairment in respiratory volumes. If an acute myasthenic crisis is suspected, measuring the negative inspiratory force and the forced vital capacity can be useful in monitoring worsening respiratory muscle weakness and assessing the need for mechanical ventilation.

In our patient, it is unlikely that pulmonary function testing would help, since her acute respiratory failure was probably not caused by neuromuscular weakness.

Repeated arterial blood gas measurement would likely only confirm that the patient still has positional hypoxemia but would not help sort through the differential diagnosis.

Edrophonium testing is useful in diagnosing myasthenia gravis and differentiating it from other neuromuscular diseases, such as Lambert-Eaton syndrome. Edrophonium, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, prevents degradation of acetylcholine and prolongs its effect at the synaptic cleft, thus improving muscle weakness.

Our patient has already been diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, so this test is not likely to uncover the cause of her hypoxemia.

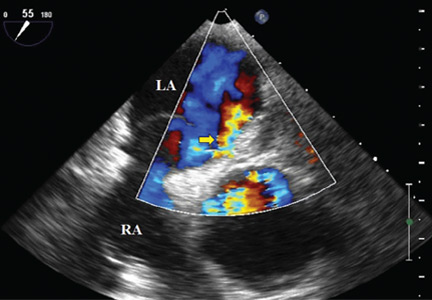

Because we still strongly suspected a shunt, TEE was performed with intravenous injection of agitated saline. TEE with the patient upright revealed intracardiac right-to-left shunting through a patent foramen ovale. The midesophageal view after saline injection showed a large interatrial septal aneurysm with total excursion of 2 cm, and right-to-left shunting within the first beat, consistent with an intracardiac shunt (Figure 1). Color Doppler imaging (Figure 2) demonstrated turbulent flow through the patent foramen ovale, consistent with right-to-left shunting, and also showed the patent foramen ovale in a closed position (Figure 3).

3. Which is now most likely the cause of our patient’s hypoxemia?

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- Myasthenic crisis

- Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome due to the patent foramen ovale

- Methemoglobinemia

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is usually a long-term result of untreated or inadequately treated thromboembolic disease (eg, pulmonary emboli), which causes vascular remodeling and pulmonary arteriopathy, which in turn leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension.

This is unlikely the cause of our patient’s acute hypoxemia, as her symptoms did not suggest it. Moreover, an elevated right ventricular systolic pressure on TTE would suggest pulmonary hypertension, but TTE did not show this, and repeat chest CT indicated that her pulmonary embolism had been adequately treated and had resolved. A V/Q scan and right heart catheterization would help rule out chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, although these were not done in our patient.

Myasthenic crisis is the progressive fatiguing and paralysis of respiratory muscles ultimately requiring mechanical ventilation to sustain life. It is often brought on by infection or drug therapy.

Our patient did not require intubation and she had no signs or symptoms of myasthenic crisis such as ptosis, dysphagia, or dysarthria. She had a negative inspiratory force of −21 cm H2O, and pulmonary function testing 4 days before her hospital admission had shown a forced vital capacity of 1.84 L, making myasthenic crisis an unlikely cause of her respiratory failure.

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is a syndrome of dyspnea (platypnea) and hypoxemia (orthodeoxia) that is induced by sitting upright or standing and resolves when lying down. It is a result of right-to-left intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunting in the presence of an anatomic defect and a functional element causing redirection of shunt flow through the anatomic defect in an upright position.1 It is associated with specific cardiac, pulmonary, and hepatic diseases, such as atrial septal defect, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, and hepatopulmonary syndrome.2 It can occur even if right-sided chamber pressures are normal, and several mechanisms of the underlying pathophysiology have been described.3

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome can be triggered by an event that causes a spontaneous transient elevation of right atrial pressure and pulmonary hypertension, such as our patient’s acute pulmonary embolism. Increased right-to-left shunting occurs in an upright position, causing preferential redirection of flow from the inferior vena cava through the interatrial septum and the patent foramen ovale.4

Our patient was elderly and, like one in every four people in the world, she had had a patent foramen ovale since the day she was born. Never causing a problem, it had remained undiagnosed until complicated by platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome after her recent pulmonary embolism.

Methemoglobinemia. Methemoglobin has a lower affinity for oxygen than normal hemoglobin. Elevations usually occur with medications such as anesthetics and nitrates and can be diagnosed through an elevated level on arterial blood gas testing.

Our patient did not have elevated methemoglobin on her blood gas measurements on admission; therefore, this is unlikely to be the diagnosis.

CASE CONCLUDED

Percutaneous closure of the patent foramen ovale with a 30-mm Amplatzer Cribriform Occluder brought significant improvement in our patient’s functional status and arterial oxygenation saturation, and 2 weeks later at follow-up she no longer needed supplemental oxygen. TEE 6 months later showed an intact closure device and no interatrial shunting.

WHEN HYPOXEMIA DOES NOT RESPOND TO OXYGEN

In the intensive care unit, time is critical, and when hypoxia is refractory to high Fio2, shunting should be considered.

In the acute-care setting, platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome can be identified quickly by pulse oximetry and serial blood gas measurements in the upright and supine positions. A drop in arterial oxygenation in the upright position vs the supine position helps confirm the diagnosis.

Other conditions in the differential diagnosis of this syndrome include recurrent pulmonary embolism, acute respiratory distress syndrome, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, intrapulmonary shunting due to arteriovenous malformation, and diaphragm paralysis due to neuromuscular disease.

In our patient, positional blood gas measurements demonstrated a significant drop in arterial oxygen saturation from the supine to the upright position, raising our suspicion of shunting. It helped narrow the differential diagnosis and guided our selection of additional diagnostic tests.

The initial chest radiograph in our patient was normal. TTE did not reveal shunting and showed a normal right ventricular systolic pressure. TTE with agitated saline also failed to reveal shunting. Because of suboptimal positioning and image quality, TTE may miss the shunting physiology, and that is why we proceeded to positional TEE, which can better evaluate the hemodynamic effects of positional changes on patent foramen ovale and shunting.

MORE ABOUT PATENT FORAMEN OVALE

The prevalence of patent foramen ovale is estimated at 27% in the general population, but it is usually not symptomatic. It can be associated with atrial septal aneurysm and Chiari network malformations. When associated with atrial septal aneurysm, it carries a higher risk of stroke.5

Our patient had a large atrial septal aneurysm with a septal excursion of 2 cm as well as a history of thromboembolic stroke, which was likely associated with the patent foramen ovale and the atrial septal aneurysm.

Atrial septal aneurysm is rare, with a prevalence of 1% at autopsy and 1.9% by TTE. It is defined by a septal excursion of at least 10 mm and a base diameter of at least 15 mm and is more frequently detected on TEE than on TTE.6

Studies have shown that contrast and color Doppler TEE are superior to TTE for detecting patent foramen ovale.7 Tilt-table TEE with contrast enhancement has also been used to better demonstrate the morphology of the interatrial septum and the degree of shunting due to the separation between the septum primum and septum secundum causing the patent foramen ovale.8 Contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler has also been shown comparable to contrast TEE to detect interatrial shunting. However, TEE provides additional anatomic information.9

In our patient, atrial septal aneurysm and patent foramen ovale were exaggerated by upright positioning, which opened the aneurysm and increased the shunting through the patent foramen ovale.

The treatment of choice in symptomatic patients with platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is directed at the underlying cause, in this case closure of the foramen ovale. This treatment has been shown to be safe and effective in these patients,10 but caution should be used when considering foramen ovale closure in patients with pulmonary hypertension.11

In patients with irreversible or severe pulmonary hypertension, closure of the patent foramen ovale can exacerbate right heart dysfunction and lead to right heart failure. There are situations when closure of a patent foramen ovale can be considered in pulmonary hypertension; however, each decision is individualized, and caution must be used. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this paper.

A thorough history and physical examination are important in differentiating the various causes of hypoxemia. Appropriate diagnostic testing is needed along with prompt treatment of the underlying cause of platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome.

- Cheng TO. Mechanisms of platypnea-orthodeoxia: what causes water to flow uphill? Circulation 2002; 105:e47.

- Natalie AA, Nichols L, Bump GM. Platypnea-orthodeoxia, an uncommon presentation of patent foramen ovale. Am J Med Sci 2010; 339:78–80.

- Acharya SS, Kartan R. A case of orthodeoxia caused by an atrial septal aneurysm. Chest 2000; 118:871–874.

- Irwin B, Ray S. Patent foramen ovale—assessment and treatment. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30:e128–e135.

- Mas JL, Zuber M. Recurrent cerebrovascular events in patients with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both and cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. French Study Group on Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Aneurysm. Am Heart J 1995; 130:1083–1088.

- Kerut EK, Norfleet WT, Plotnick GD, Giles TD. Patent foramen ovale: a review of associated conditions and the impact of physiological size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38:613–623.

- Hausmann D, Mügge A, Becht I, Daniel WG. Diagnosis of patent foramen ovale by transesophageal echocardiography and association with cerebral and peripheral embolic events. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70:668–672.

- Roxas-Timonera M, Larracas C, Gersony D, Di Tullio M, Keller A, Homma S. Patent foramen ovale presenting as platypnea-orthodeoxia: diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2001; 14:1039–1041.

- Sloan MA, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH, et al; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2004; 62:1468–1481.

- Blanche C, Noble S, Roffi M, et al. Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome in the elderly treated by percutaneous patent foramen ovale closure: a case series and literature review. Eur J Intern Med 2013; 24:813–817.

- Tobis J, Shenoda M. Percutaneous treatment of patent foramen ovale and atrial septal defects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1722–1732.

An 85-year-old woman was brought to our intensive care unit because of worsening hypoxemia over the past day. About 3 weeks earlier she had been diagnosed with acute bilateral pulmonary emboli in the distal branches of the left and right lower lobes and right middle lobe, for which she was receiving anticoagulation therapy.

At presentation she had generalized fatigue and dyspnea at rest that was worse with exertion, but she denied having fever, chest pain, or cough. Her medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, stage 1 breast cancer in remission, thromboembolic stroke, and myasthenia gravis. Before her hospital admission, she had been taking rosuvastatin, metoprolol tartrate, pyridostigmine, prednisone, furosemide, levothyroxine, and rivaroxaban. She did not smoke, she was retired, and she had not traveled recently.

Her blood pressure was 135/66 mm Hg, pulse 73 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16, temperature 35.4ºC (95.7ºF), and oxygen saturation 88% while receiving oxygen at 6 L/min via nasal cannula. Physical examination revealed mild edema in the lower extremities and basilar decreased breath sounds. She had no finger clubbing or cyanosis and was not using accessory muscles to breathe. Of note, her oxygen saturation remained more than 93% when she was recumbent but sharply dropped to less than 85% when she was upright.

Laboratory values

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 138 mmol/L (reference range 132–148)

- Potassium 4.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Chloride 99 mmol/L (98–111)

- Bicarbonate 29 mmol/L (23–32)

- Creatinine 0.52 mg/dL (0.7–1.4).

- White blood cell count 11.06 × 109/L (3.7–11.0)

- Hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL (12–16)

- Platelet count 211 × 109/L (150–400).

- International normalized ratio 1.4.

Electrocardiography and imaging studies

Standard 12-lead electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm with left axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Chest radiography showed bilateral interstitial opacities and small pleural effusions.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast, compared with a CT scan done 20 days earlier, showed that the pulmonary emboli had resolved.

Arterial blood gases

In view of her positional hypoxemia, blood for arterial blood gas measurements was drawn in the supine and upright positions.

Supine, with a fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) via high-flow nasal cannula of 45%, her values were:

- pH 7.45 (reference range 7.35–7.45)

- Pco2 34 mm Hg (36–46)

- Po2 81 mm Hg (85–95)

- Bicarbonate 23 mmol/L (22–26).

Upright, her hypoxemia was significantly worse:

- pH 7.46

- Pco2 33 mm Hg

- Po2 57 mm Hg

- Bicarbonate 23 mmol/L.

The methemoglobin level was normal on both measurements.

During her stay in the intensive care unit, she required up to 100% Fio2 because of persistent hypoxemia.

CAUSES OF HYPOXEMIA

1. So far, the patient’s laboratory tests and imaging studies point to which of the following as the most likely cause of her severe hypoxemia?

- Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch

- Diffusion abnormality

- Hypoventilation

- Shunting

- None of the above

The arterial blood gas measurements suggested the possibility of shunting as the cause, although further imaging would be needed to confirm that.

V/Q mismatch can occur in respiratory failure due to pulmonary embolism, pulmonary edema, or shunting. If ventilation is preserved but perfusion is impaired, the V/Q ratio approaches infinity (dead-space ventilation), a situation that can be seen in pulmonary embolism. If perfusion is preserved and ventilation is impaired, the V/Q ratio approaches zero, which is consistent with a physiologic shunt.

Hypoxemia may improve in less severe forms of V/Q mismatch. In our patient, the repeat CT with contrast showed that her pulmonary embolism had resolved, so this is probably not the cause of her severe hypoxemia.

Diffusion abnormalities are due to defects in the lung parenchyma, such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, and lung fibrosis.

Hypoxemia from diffusion defects is usually aggravated by a precipitating factor that increases oxygen demand, and it usually improves with oxygen supplementation. This is unlikely in our patient, as she did not have a history of chronic interstitial lung disease and CT showed no evidence of severe lung parenchymal disease.

Hypoventilation is usually due to drugs that cause respiratory depression, to stroke, or to neuromuscular diseases such as myasthenia gravis that can cause respiratory muscle weakness. It results in elevation of Pco2 and, if not corrected, respiratory acidosis.

Our patient had a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis, though hypoventilation is unlikely in her case because she had a normal respiratory rate and low Pco2 values.

Shunting can be physiologic or anatomic and can occur in the heart or the lungs. In physiologic shunting, severe V/Q mismatch can occur when ventilation is affected, as in severe pulmonary edema and pneumonia. In anatomic shunting, a defect such as an atrial septal defect or a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation allows blood to bypass areas of ventilation from the venous to the arterial circulation, preventing it from being oxygenated. In true anatomic shunting, supplemental oxygen with 100% Fio2 has little effect, whereas in V/Q mismatch it can raise the arterial oxygen saturation.

Our patient’s radiograph did not suggest severe pneumonia or pulmonary edema, which makes these unlikely causes of her hypoxemia. At this point, because of her positional hypoxemia, further evaluation with contrast-enhanced echocardiography was needed to evaluate for anatomic shunting in the heart or lungs.

FURTHER TESTING

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with agitated saline with a Valsalva maneuver was performed. Normally, no bubbles are seen in the left-sided chambers after intravenous injection of agitated saline contrast, whereas bubbles on the left side suggest an intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt. In our patient, this test was negative, and her right ventricular systolic pressure was normal.

2. What further testing should be considered to evaluate our patient’s hypoxemia?

- High-resolution chest CT

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

- Pulmonary function testing

- Repeated arterial blood gas measurement

- Edrophonium testing

Repeat imaging with high-resolution CT would likely not provide additional information and would expose the patient to additional radiation without adding much clinical benefit.

TEE could help further evaluate the intracardiac anatomy and look for shunting, which may be missed on TTE because of suboptimal positioning or image quality.

Pulmonary function testing is useful in establishing the baseline function and impairment in respiratory volumes. If an acute myasthenic crisis is suspected, measuring the negative inspiratory force and the forced vital capacity can be useful in monitoring worsening respiratory muscle weakness and assessing the need for mechanical ventilation.

In our patient, it is unlikely that pulmonary function testing would help, since her acute respiratory failure was probably not caused by neuromuscular weakness.

Repeated arterial blood gas measurement would likely only confirm that the patient still has positional hypoxemia but would not help sort through the differential diagnosis.

Edrophonium testing is useful in diagnosing myasthenia gravis and differentiating it from other neuromuscular diseases, such as Lambert-Eaton syndrome. Edrophonium, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, prevents degradation of acetylcholine and prolongs its effect at the synaptic cleft, thus improving muscle weakness.

Our patient has already been diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, so this test is not likely to uncover the cause of her hypoxemia.

Because we still strongly suspected a shunt, TEE was performed with intravenous injection of agitated saline. TEE with the patient upright revealed intracardiac right-to-left shunting through a patent foramen ovale. The midesophageal view after saline injection showed a large interatrial septal aneurysm with total excursion of 2 cm, and right-to-left shunting within the first beat, consistent with an intracardiac shunt (Figure 1). Color Doppler imaging (Figure 2) demonstrated turbulent flow through the patent foramen ovale, consistent with right-to-left shunting, and also showed the patent foramen ovale in a closed position (Figure 3).

3. Which is now most likely the cause of our patient’s hypoxemia?

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- Myasthenic crisis

- Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome due to the patent foramen ovale

- Methemoglobinemia

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is usually a long-term result of untreated or inadequately treated thromboembolic disease (eg, pulmonary emboli), which causes vascular remodeling and pulmonary arteriopathy, which in turn leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension.

This is unlikely the cause of our patient’s acute hypoxemia, as her symptoms did not suggest it. Moreover, an elevated right ventricular systolic pressure on TTE would suggest pulmonary hypertension, but TTE did not show this, and repeat chest CT indicated that her pulmonary embolism had been adequately treated and had resolved. A V/Q scan and right heart catheterization would help rule out chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, although these were not done in our patient.

Myasthenic crisis is the progressive fatiguing and paralysis of respiratory muscles ultimately requiring mechanical ventilation to sustain life. It is often brought on by infection or drug therapy.

Our patient did not require intubation and she had no signs or symptoms of myasthenic crisis such as ptosis, dysphagia, or dysarthria. She had a negative inspiratory force of −21 cm H2O, and pulmonary function testing 4 days before her hospital admission had shown a forced vital capacity of 1.84 L, making myasthenic crisis an unlikely cause of her respiratory failure.

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is a syndrome of dyspnea (platypnea) and hypoxemia (orthodeoxia) that is induced by sitting upright or standing and resolves when lying down. It is a result of right-to-left intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunting in the presence of an anatomic defect and a functional element causing redirection of shunt flow through the anatomic defect in an upright position.1 It is associated with specific cardiac, pulmonary, and hepatic diseases, such as atrial septal defect, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, and hepatopulmonary syndrome.2 It can occur even if right-sided chamber pressures are normal, and several mechanisms of the underlying pathophysiology have been described.3

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome can be triggered by an event that causes a spontaneous transient elevation of right atrial pressure and pulmonary hypertension, such as our patient’s acute pulmonary embolism. Increased right-to-left shunting occurs in an upright position, causing preferential redirection of flow from the inferior vena cava through the interatrial septum and the patent foramen ovale.4

Our patient was elderly and, like one in every four people in the world, she had had a patent foramen ovale since the day she was born. Never causing a problem, it had remained undiagnosed until complicated by platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome after her recent pulmonary embolism.

Methemoglobinemia. Methemoglobin has a lower affinity for oxygen than normal hemoglobin. Elevations usually occur with medications such as anesthetics and nitrates and can be diagnosed through an elevated level on arterial blood gas testing.

Our patient did not have elevated methemoglobin on her blood gas measurements on admission; therefore, this is unlikely to be the diagnosis.

CASE CONCLUDED

Percutaneous closure of the patent foramen ovale with a 30-mm Amplatzer Cribriform Occluder brought significant improvement in our patient’s functional status and arterial oxygenation saturation, and 2 weeks later at follow-up she no longer needed supplemental oxygen. TEE 6 months later showed an intact closure device and no interatrial shunting.

WHEN HYPOXEMIA DOES NOT RESPOND TO OXYGEN

In the intensive care unit, time is critical, and when hypoxia is refractory to high Fio2, shunting should be considered.

In the acute-care setting, platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome can be identified quickly by pulse oximetry and serial blood gas measurements in the upright and supine positions. A drop in arterial oxygenation in the upright position vs the supine position helps confirm the diagnosis.

Other conditions in the differential diagnosis of this syndrome include recurrent pulmonary embolism, acute respiratory distress syndrome, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, intrapulmonary shunting due to arteriovenous malformation, and diaphragm paralysis due to neuromuscular disease.

In our patient, positional blood gas measurements demonstrated a significant drop in arterial oxygen saturation from the supine to the upright position, raising our suspicion of shunting. It helped narrow the differential diagnosis and guided our selection of additional diagnostic tests.

The initial chest radiograph in our patient was normal. TTE did not reveal shunting and showed a normal right ventricular systolic pressure. TTE with agitated saline also failed to reveal shunting. Because of suboptimal positioning and image quality, TTE may miss the shunting physiology, and that is why we proceeded to positional TEE, which can better evaluate the hemodynamic effects of positional changes on patent foramen ovale and shunting.

MORE ABOUT PATENT FORAMEN OVALE

The prevalence of patent foramen ovale is estimated at 27% in the general population, but it is usually not symptomatic. It can be associated with atrial septal aneurysm and Chiari network malformations. When associated with atrial septal aneurysm, it carries a higher risk of stroke.5

Our patient had a large atrial septal aneurysm with a septal excursion of 2 cm as well as a history of thromboembolic stroke, which was likely associated with the patent foramen ovale and the atrial septal aneurysm.

Atrial septal aneurysm is rare, with a prevalence of 1% at autopsy and 1.9% by TTE. It is defined by a septal excursion of at least 10 mm and a base diameter of at least 15 mm and is more frequently detected on TEE than on TTE.6

Studies have shown that contrast and color Doppler TEE are superior to TTE for detecting patent foramen ovale.7 Tilt-table TEE with contrast enhancement has also been used to better demonstrate the morphology of the interatrial septum and the degree of shunting due to the separation between the septum primum and septum secundum causing the patent foramen ovale.8 Contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler has also been shown comparable to contrast TEE to detect interatrial shunting. However, TEE provides additional anatomic information.9

In our patient, atrial septal aneurysm and patent foramen ovale were exaggerated by upright positioning, which opened the aneurysm and increased the shunting through the patent foramen ovale.

The treatment of choice in symptomatic patients with platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is directed at the underlying cause, in this case closure of the foramen ovale. This treatment has been shown to be safe and effective in these patients,10 but caution should be used when considering foramen ovale closure in patients with pulmonary hypertension.11

In patients with irreversible or severe pulmonary hypertension, closure of the patent foramen ovale can exacerbate right heart dysfunction and lead to right heart failure. There are situations when closure of a patent foramen ovale can be considered in pulmonary hypertension; however, each decision is individualized, and caution must be used. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this paper.

A thorough history and physical examination are important in differentiating the various causes of hypoxemia. Appropriate diagnostic testing is needed along with prompt treatment of the underlying cause of platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome.

An 85-year-old woman was brought to our intensive care unit because of worsening hypoxemia over the past day. About 3 weeks earlier she had been diagnosed with acute bilateral pulmonary emboli in the distal branches of the left and right lower lobes and right middle lobe, for which she was receiving anticoagulation therapy.

At presentation she had generalized fatigue and dyspnea at rest that was worse with exertion, but she denied having fever, chest pain, or cough. Her medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, stage 1 breast cancer in remission, thromboembolic stroke, and myasthenia gravis. Before her hospital admission, she had been taking rosuvastatin, metoprolol tartrate, pyridostigmine, prednisone, furosemide, levothyroxine, and rivaroxaban. She did not smoke, she was retired, and she had not traveled recently.

Her blood pressure was 135/66 mm Hg, pulse 73 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16, temperature 35.4ºC (95.7ºF), and oxygen saturation 88% while receiving oxygen at 6 L/min via nasal cannula. Physical examination revealed mild edema in the lower extremities and basilar decreased breath sounds. She had no finger clubbing or cyanosis and was not using accessory muscles to breathe. Of note, her oxygen saturation remained more than 93% when she was recumbent but sharply dropped to less than 85% when she was upright.

Laboratory values

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 138 mmol/L (reference range 132–148)

- Potassium 4.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Chloride 99 mmol/L (98–111)

- Bicarbonate 29 mmol/L (23–32)

- Creatinine 0.52 mg/dL (0.7–1.4).

- White blood cell count 11.06 × 109/L (3.7–11.0)

- Hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL (12–16)

- Platelet count 211 × 109/L (150–400).

- International normalized ratio 1.4.

Electrocardiography and imaging studies

Standard 12-lead electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm with left axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Chest radiography showed bilateral interstitial opacities and small pleural effusions.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast, compared with a CT scan done 20 days earlier, showed that the pulmonary emboli had resolved.

Arterial blood gases

In view of her positional hypoxemia, blood for arterial blood gas measurements was drawn in the supine and upright positions.

Supine, with a fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) via high-flow nasal cannula of 45%, her values were:

- pH 7.45 (reference range 7.35–7.45)

- Pco2 34 mm Hg (36–46)

- Po2 81 mm Hg (85–95)

- Bicarbonate 23 mmol/L (22–26).

Upright, her hypoxemia was significantly worse:

- pH 7.46

- Pco2 33 mm Hg

- Po2 57 mm Hg

- Bicarbonate 23 mmol/L.

The methemoglobin level was normal on both measurements.

During her stay in the intensive care unit, she required up to 100% Fio2 because of persistent hypoxemia.

CAUSES OF HYPOXEMIA

1. So far, the patient’s laboratory tests and imaging studies point to which of the following as the most likely cause of her severe hypoxemia?

- Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch

- Diffusion abnormality

- Hypoventilation

- Shunting

- None of the above

The arterial blood gas measurements suggested the possibility of shunting as the cause, although further imaging would be needed to confirm that.

V/Q mismatch can occur in respiratory failure due to pulmonary embolism, pulmonary edema, or shunting. If ventilation is preserved but perfusion is impaired, the V/Q ratio approaches infinity (dead-space ventilation), a situation that can be seen in pulmonary embolism. If perfusion is preserved and ventilation is impaired, the V/Q ratio approaches zero, which is consistent with a physiologic shunt.

Hypoxemia may improve in less severe forms of V/Q mismatch. In our patient, the repeat CT with contrast showed that her pulmonary embolism had resolved, so this is probably not the cause of her severe hypoxemia.

Diffusion abnormalities are due to defects in the lung parenchyma, such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, and lung fibrosis.

Hypoxemia from diffusion defects is usually aggravated by a precipitating factor that increases oxygen demand, and it usually improves with oxygen supplementation. This is unlikely in our patient, as she did not have a history of chronic interstitial lung disease and CT showed no evidence of severe lung parenchymal disease.

Hypoventilation is usually due to drugs that cause respiratory depression, to stroke, or to neuromuscular diseases such as myasthenia gravis that can cause respiratory muscle weakness. It results in elevation of Pco2 and, if not corrected, respiratory acidosis.

Our patient had a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis, though hypoventilation is unlikely in her case because she had a normal respiratory rate and low Pco2 values.

Shunting can be physiologic or anatomic and can occur in the heart or the lungs. In physiologic shunting, severe V/Q mismatch can occur when ventilation is affected, as in severe pulmonary edema and pneumonia. In anatomic shunting, a defect such as an atrial septal defect or a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation allows blood to bypass areas of ventilation from the venous to the arterial circulation, preventing it from being oxygenated. In true anatomic shunting, supplemental oxygen with 100% Fio2 has little effect, whereas in V/Q mismatch it can raise the arterial oxygen saturation.

Our patient’s radiograph did not suggest severe pneumonia or pulmonary edema, which makes these unlikely causes of her hypoxemia. At this point, because of her positional hypoxemia, further evaluation with contrast-enhanced echocardiography was needed to evaluate for anatomic shunting in the heart or lungs.

FURTHER TESTING

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with agitated saline with a Valsalva maneuver was performed. Normally, no bubbles are seen in the left-sided chambers after intravenous injection of agitated saline contrast, whereas bubbles on the left side suggest an intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt. In our patient, this test was negative, and her right ventricular systolic pressure was normal.

2. What further testing should be considered to evaluate our patient’s hypoxemia?

- High-resolution chest CT

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

- Pulmonary function testing

- Repeated arterial blood gas measurement

- Edrophonium testing

Repeat imaging with high-resolution CT would likely not provide additional information and would expose the patient to additional radiation without adding much clinical benefit.

TEE could help further evaluate the intracardiac anatomy and look for shunting, which may be missed on TTE because of suboptimal positioning or image quality.

Pulmonary function testing is useful in establishing the baseline function and impairment in respiratory volumes. If an acute myasthenic crisis is suspected, measuring the negative inspiratory force and the forced vital capacity can be useful in monitoring worsening respiratory muscle weakness and assessing the need for mechanical ventilation.

In our patient, it is unlikely that pulmonary function testing would help, since her acute respiratory failure was probably not caused by neuromuscular weakness.

Repeated arterial blood gas measurement would likely only confirm that the patient still has positional hypoxemia but would not help sort through the differential diagnosis.

Edrophonium testing is useful in diagnosing myasthenia gravis and differentiating it from other neuromuscular diseases, such as Lambert-Eaton syndrome. Edrophonium, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, prevents degradation of acetylcholine and prolongs its effect at the synaptic cleft, thus improving muscle weakness.

Our patient has already been diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, so this test is not likely to uncover the cause of her hypoxemia.

Because we still strongly suspected a shunt, TEE was performed with intravenous injection of agitated saline. TEE with the patient upright revealed intracardiac right-to-left shunting through a patent foramen ovale. The midesophageal view after saline injection showed a large interatrial septal aneurysm with total excursion of 2 cm, and right-to-left shunting within the first beat, consistent with an intracardiac shunt (Figure 1). Color Doppler imaging (Figure 2) demonstrated turbulent flow through the patent foramen ovale, consistent with right-to-left shunting, and also showed the patent foramen ovale in a closed position (Figure 3).

3. Which is now most likely the cause of our patient’s hypoxemia?

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- Myasthenic crisis

- Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome due to the patent foramen ovale

- Methemoglobinemia

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is usually a long-term result of untreated or inadequately treated thromboembolic disease (eg, pulmonary emboli), which causes vascular remodeling and pulmonary arteriopathy, which in turn leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension.

This is unlikely the cause of our patient’s acute hypoxemia, as her symptoms did not suggest it. Moreover, an elevated right ventricular systolic pressure on TTE would suggest pulmonary hypertension, but TTE did not show this, and repeat chest CT indicated that her pulmonary embolism had been adequately treated and had resolved. A V/Q scan and right heart catheterization would help rule out chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, although these were not done in our patient.

Myasthenic crisis is the progressive fatiguing and paralysis of respiratory muscles ultimately requiring mechanical ventilation to sustain life. It is often brought on by infection or drug therapy.

Our patient did not require intubation and she had no signs or symptoms of myasthenic crisis such as ptosis, dysphagia, or dysarthria. She had a negative inspiratory force of −21 cm H2O, and pulmonary function testing 4 days before her hospital admission had shown a forced vital capacity of 1.84 L, making myasthenic crisis an unlikely cause of her respiratory failure.

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is a syndrome of dyspnea (platypnea) and hypoxemia (orthodeoxia) that is induced by sitting upright or standing and resolves when lying down. It is a result of right-to-left intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunting in the presence of an anatomic defect and a functional element causing redirection of shunt flow through the anatomic defect in an upright position.1 It is associated with specific cardiac, pulmonary, and hepatic diseases, such as atrial septal defect, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, and hepatopulmonary syndrome.2 It can occur even if right-sided chamber pressures are normal, and several mechanisms of the underlying pathophysiology have been described.3

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome can be triggered by an event that causes a spontaneous transient elevation of right atrial pressure and pulmonary hypertension, such as our patient’s acute pulmonary embolism. Increased right-to-left shunting occurs in an upright position, causing preferential redirection of flow from the inferior vena cava through the interatrial septum and the patent foramen ovale.4

Our patient was elderly and, like one in every four people in the world, she had had a patent foramen ovale since the day she was born. Never causing a problem, it had remained undiagnosed until complicated by platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome after her recent pulmonary embolism.

Methemoglobinemia. Methemoglobin has a lower affinity for oxygen than normal hemoglobin. Elevations usually occur with medications such as anesthetics and nitrates and can be diagnosed through an elevated level on arterial blood gas testing.

Our patient did not have elevated methemoglobin on her blood gas measurements on admission; therefore, this is unlikely to be the diagnosis.

CASE CONCLUDED

Percutaneous closure of the patent foramen ovale with a 30-mm Amplatzer Cribriform Occluder brought significant improvement in our patient’s functional status and arterial oxygenation saturation, and 2 weeks later at follow-up she no longer needed supplemental oxygen. TEE 6 months later showed an intact closure device and no interatrial shunting.

WHEN HYPOXEMIA DOES NOT RESPOND TO OXYGEN

In the intensive care unit, time is critical, and when hypoxia is refractory to high Fio2, shunting should be considered.

In the acute-care setting, platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome can be identified quickly by pulse oximetry and serial blood gas measurements in the upright and supine positions. A drop in arterial oxygenation in the upright position vs the supine position helps confirm the diagnosis.

Other conditions in the differential diagnosis of this syndrome include recurrent pulmonary embolism, acute respiratory distress syndrome, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, intrapulmonary shunting due to arteriovenous malformation, and diaphragm paralysis due to neuromuscular disease.

In our patient, positional blood gas measurements demonstrated a significant drop in arterial oxygen saturation from the supine to the upright position, raising our suspicion of shunting. It helped narrow the differential diagnosis and guided our selection of additional diagnostic tests.

The initial chest radiograph in our patient was normal. TTE did not reveal shunting and showed a normal right ventricular systolic pressure. TTE with agitated saline also failed to reveal shunting. Because of suboptimal positioning and image quality, TTE may miss the shunting physiology, and that is why we proceeded to positional TEE, which can better evaluate the hemodynamic effects of positional changes on patent foramen ovale and shunting.

MORE ABOUT PATENT FORAMEN OVALE

The prevalence of patent foramen ovale is estimated at 27% in the general population, but it is usually not symptomatic. It can be associated with atrial septal aneurysm and Chiari network malformations. When associated with atrial septal aneurysm, it carries a higher risk of stroke.5

Our patient had a large atrial septal aneurysm with a septal excursion of 2 cm as well as a history of thromboembolic stroke, which was likely associated with the patent foramen ovale and the atrial septal aneurysm.

Atrial septal aneurysm is rare, with a prevalence of 1% at autopsy and 1.9% by TTE. It is defined by a septal excursion of at least 10 mm and a base diameter of at least 15 mm and is more frequently detected on TEE than on TTE.6

Studies have shown that contrast and color Doppler TEE are superior to TTE for detecting patent foramen ovale.7 Tilt-table TEE with contrast enhancement has also been used to better demonstrate the morphology of the interatrial septum and the degree of shunting due to the separation between the septum primum and septum secundum causing the patent foramen ovale.8 Contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler has also been shown comparable to contrast TEE to detect interatrial shunting. However, TEE provides additional anatomic information.9

In our patient, atrial septal aneurysm and patent foramen ovale were exaggerated by upright positioning, which opened the aneurysm and increased the shunting through the patent foramen ovale.

The treatment of choice in symptomatic patients with platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is directed at the underlying cause, in this case closure of the foramen ovale. This treatment has been shown to be safe and effective in these patients,10 but caution should be used when considering foramen ovale closure in patients with pulmonary hypertension.11

In patients with irreversible or severe pulmonary hypertension, closure of the patent foramen ovale can exacerbate right heart dysfunction and lead to right heart failure. There are situations when closure of a patent foramen ovale can be considered in pulmonary hypertension; however, each decision is individualized, and caution must be used. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this paper.

A thorough history and physical examination are important in differentiating the various causes of hypoxemia. Appropriate diagnostic testing is needed along with prompt treatment of the underlying cause of platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome.

- Cheng TO. Mechanisms of platypnea-orthodeoxia: what causes water to flow uphill? Circulation 2002; 105:e47.

- Natalie AA, Nichols L, Bump GM. Platypnea-orthodeoxia, an uncommon presentation of patent foramen ovale. Am J Med Sci 2010; 339:78–80.

- Acharya SS, Kartan R. A case of orthodeoxia caused by an atrial septal aneurysm. Chest 2000; 118:871–874.

- Irwin B, Ray S. Patent foramen ovale—assessment and treatment. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30:e128–e135.

- Mas JL, Zuber M. Recurrent cerebrovascular events in patients with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both and cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. French Study Group on Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Aneurysm. Am Heart J 1995; 130:1083–1088.

- Kerut EK, Norfleet WT, Plotnick GD, Giles TD. Patent foramen ovale: a review of associated conditions and the impact of physiological size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38:613–623.

- Hausmann D, Mügge A, Becht I, Daniel WG. Diagnosis of patent foramen ovale by transesophageal echocardiography and association with cerebral and peripheral embolic events. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70:668–672.

- Roxas-Timonera M, Larracas C, Gersony D, Di Tullio M, Keller A, Homma S. Patent foramen ovale presenting as platypnea-orthodeoxia: diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2001; 14:1039–1041.

- Sloan MA, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH, et al; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2004; 62:1468–1481.

- Blanche C, Noble S, Roffi M, et al. Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome in the elderly treated by percutaneous patent foramen ovale closure: a case series and literature review. Eur J Intern Med 2013; 24:813–817.

- Tobis J, Shenoda M. Percutaneous treatment of patent foramen ovale and atrial septal defects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1722–1732.

- Cheng TO. Mechanisms of platypnea-orthodeoxia: what causes water to flow uphill? Circulation 2002; 105:e47.

- Natalie AA, Nichols L, Bump GM. Platypnea-orthodeoxia, an uncommon presentation of patent foramen ovale. Am J Med Sci 2010; 339:78–80.

- Acharya SS, Kartan R. A case of orthodeoxia caused by an atrial septal aneurysm. Chest 2000; 118:871–874.

- Irwin B, Ray S. Patent foramen ovale—assessment and treatment. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30:e128–e135.

- Mas JL, Zuber M. Recurrent cerebrovascular events in patients with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both and cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. French Study Group on Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Aneurysm. Am Heart J 1995; 130:1083–1088.

- Kerut EK, Norfleet WT, Plotnick GD, Giles TD. Patent foramen ovale: a review of associated conditions and the impact of physiological size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38:613–623.

- Hausmann D, Mügge A, Becht I, Daniel WG. Diagnosis of patent foramen ovale by transesophageal echocardiography and association with cerebral and peripheral embolic events. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70:668–672.

- Roxas-Timonera M, Larracas C, Gersony D, Di Tullio M, Keller A, Homma S. Patent foramen ovale presenting as platypnea-orthodeoxia: diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2001; 14:1039–1041.

- Sloan MA, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH, et al; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2004; 62:1468–1481.

- Blanche C, Noble S, Roffi M, et al. Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome in the elderly treated by percutaneous patent foramen ovale closure: a case series and literature review. Eur J Intern Med 2013; 24:813–817.

- Tobis J, Shenoda M. Percutaneous treatment of patent foramen ovale and atrial septal defects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1722–1732.

Hordeolum: Acute abscess within an eyelid sebaceous gland

An 89-year-old man presented complaining of a tender, painful lump in the right lower eyelid that spontaneously appeared 3 days previously. There was no discharge, bleeding, or reduced vision. He had a history of hypertension and macular degeneration. There was no history of a pre-existing eyelid lesion, ocular malignancy, rosacea, or seborrheic dermatitis. Examination of the right lower lid revealed a roundish raised abscess with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). The raised area was tender on palpation; there was no discharge. The palpebral conjunctiva was normal. A diagnosis of a hordeolum was made, and conservative treatment was prescribed, ie, warm compresses and massage for 10 minutes four times a day. The lesion improved gradually and resolved over 3 weeks.

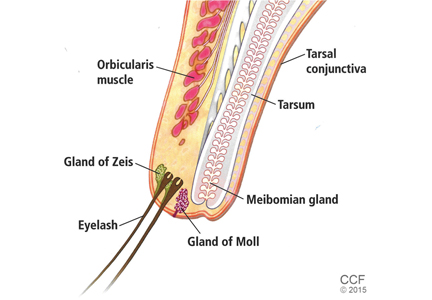

A hordeolum is an acute abscess within an eyelid gland, usually staphylococcal in origin. When it involves a meibomian gland it is termed an internal hordeolum, and when it involves the gland of Zeis or Moll it is termed an external hordeolum (Figure 2).1 Hordeola may be associated with diabetes, blepharitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and high levels of serum lipids. Treatment is with warm compresses and massage. A hordeolum with preseptal cellulitis, signs of bacteremia, or tender preauricular lymph nodes requires systemic antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 250–500 mg four times a day for 1 week).

Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum. The orbital septum is a sheet of fibrous tissue that originates in the orbital periosteum and inserts in the palpebral tissues along the tarsal plates of the eyelid. The orbital septum provides a barrier against the spread of periorbital infection into the orbit (orbital cellulitis). The causes of preseptal cellulitis include skin trauma (eg, lacerations, insect bites), spread from local infections (eg, hordeolum, dacryocystitis), or systemic infections (eg, upper respiratory tract, middle ear). Clinical features include malaise, fever, and painful eyelid with periorbital edema. Any sign of proptosis, chemosis, painful restricted eye movements, diplopia, lagophthalmos, or optic nerve dysfunction warrants further investigation. Chronic or large hordeola may require incision and curettage.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence of the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions (including hot or warm compresses, lid scrubs, antibiotics, and steroids) for hordeolum, and controlled clinical trials would be useful.2

Chalazion and hordeolum are similar in appearance and often confused (Table 1). A chalazion is a chronic lipogranuloma due to leakage of sebum from an obstructed meibomian gland. It may develop from an internal hordeolum. Small chalazia usually resolve with time without any intervention, and hot compresses can be effective at encouraging drainage. Persistent lesions may be surgically removed by incision and curettage. Recurrence warrants biopsy and histologic study to rule out sebaceous gland carcinoma.3

- Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008; 26:57–72.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD007742.

- Denniston AKO, Murray PI: Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2009.

An 89-year-old man presented complaining of a tender, painful lump in the right lower eyelid that spontaneously appeared 3 days previously. There was no discharge, bleeding, or reduced vision. He had a history of hypertension and macular degeneration. There was no history of a pre-existing eyelid lesion, ocular malignancy, rosacea, or seborrheic dermatitis. Examination of the right lower lid revealed a roundish raised abscess with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). The raised area was tender on palpation; there was no discharge. The palpebral conjunctiva was normal. A diagnosis of a hordeolum was made, and conservative treatment was prescribed, ie, warm compresses and massage for 10 minutes four times a day. The lesion improved gradually and resolved over 3 weeks.

A hordeolum is an acute abscess within an eyelid gland, usually staphylococcal in origin. When it involves a meibomian gland it is termed an internal hordeolum, and when it involves the gland of Zeis or Moll it is termed an external hordeolum (Figure 2).1 Hordeola may be associated with diabetes, blepharitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and high levels of serum lipids. Treatment is with warm compresses and massage. A hordeolum with preseptal cellulitis, signs of bacteremia, or tender preauricular lymph nodes requires systemic antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 250–500 mg four times a day for 1 week).

Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum. The orbital septum is a sheet of fibrous tissue that originates in the orbital periosteum and inserts in the palpebral tissues along the tarsal plates of the eyelid. The orbital septum provides a barrier against the spread of periorbital infection into the orbit (orbital cellulitis). The causes of preseptal cellulitis include skin trauma (eg, lacerations, insect bites), spread from local infections (eg, hordeolum, dacryocystitis), or systemic infections (eg, upper respiratory tract, middle ear). Clinical features include malaise, fever, and painful eyelid with periorbital edema. Any sign of proptosis, chemosis, painful restricted eye movements, diplopia, lagophthalmos, or optic nerve dysfunction warrants further investigation. Chronic or large hordeola may require incision and curettage.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence of the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions (including hot or warm compresses, lid scrubs, antibiotics, and steroids) for hordeolum, and controlled clinical trials would be useful.2

Chalazion and hordeolum are similar in appearance and often confused (Table 1). A chalazion is a chronic lipogranuloma due to leakage of sebum from an obstructed meibomian gland. It may develop from an internal hordeolum. Small chalazia usually resolve with time without any intervention, and hot compresses can be effective at encouraging drainage. Persistent lesions may be surgically removed by incision and curettage. Recurrence warrants biopsy and histologic study to rule out sebaceous gland carcinoma.3

An 89-year-old man presented complaining of a tender, painful lump in the right lower eyelid that spontaneously appeared 3 days previously. There was no discharge, bleeding, or reduced vision. He had a history of hypertension and macular degeneration. There was no history of a pre-existing eyelid lesion, ocular malignancy, rosacea, or seborrheic dermatitis. Examination of the right lower lid revealed a roundish raised abscess with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). The raised area was tender on palpation; there was no discharge. The palpebral conjunctiva was normal. A diagnosis of a hordeolum was made, and conservative treatment was prescribed, ie, warm compresses and massage for 10 minutes four times a day. The lesion improved gradually and resolved over 3 weeks.

A hordeolum is an acute abscess within an eyelid gland, usually staphylococcal in origin. When it involves a meibomian gland it is termed an internal hordeolum, and when it involves the gland of Zeis or Moll it is termed an external hordeolum (Figure 2).1 Hordeola may be associated with diabetes, blepharitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and high levels of serum lipids. Treatment is with warm compresses and massage. A hordeolum with preseptal cellulitis, signs of bacteremia, or tender preauricular lymph nodes requires systemic antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 250–500 mg four times a day for 1 week).

Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum. The orbital septum is a sheet of fibrous tissue that originates in the orbital periosteum and inserts in the palpebral tissues along the tarsal plates of the eyelid. The orbital septum provides a barrier against the spread of periorbital infection into the orbit (orbital cellulitis). The causes of preseptal cellulitis include skin trauma (eg, lacerations, insect bites), spread from local infections (eg, hordeolum, dacryocystitis), or systemic infections (eg, upper respiratory tract, middle ear). Clinical features include malaise, fever, and painful eyelid with periorbital edema. Any sign of proptosis, chemosis, painful restricted eye movements, diplopia, lagophthalmos, or optic nerve dysfunction warrants further investigation. Chronic or large hordeola may require incision and curettage.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence of the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions (including hot or warm compresses, lid scrubs, antibiotics, and steroids) for hordeolum, and controlled clinical trials would be useful.2

Chalazion and hordeolum are similar in appearance and often confused (Table 1). A chalazion is a chronic lipogranuloma due to leakage of sebum from an obstructed meibomian gland. It may develop from an internal hordeolum. Small chalazia usually resolve with time without any intervention, and hot compresses can be effective at encouraging drainage. Persistent lesions may be surgically removed by incision and curettage. Recurrence warrants biopsy and histologic study to rule out sebaceous gland carcinoma.3

- Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008; 26:57–72.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD007742.

- Denniston AKO, Murray PI: Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008; 26:57–72.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD007742.

- Denniston AKO, Murray PI: Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2009.

How can I predict bleeding in my elderly patient taking anticoagulants?

We have tools to predict bleeding risk, but their predictive value is modest, and the estimated risk of bleeding is often outweighed by the benefits of anticoagulant therapy.

Anticoagulant therapy is commonly prescribed for conditions that disproportionately affect the elderly, including atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, and valvular heart disease. Though anticoagulants are highly effective in preventing clots, they also significantly increase the risk of bleeding. Since older age is a risk factor for bleeding as well as thrombosis, it is essential to weigh the risks and benefits of anticoagulants for each patient.

WHAT KINDS OF BLEEDING DEVELOP IN PATIENTS ON ANTICOAGULANTS?

Patients taking anticoagulants have roughly double the risk of bleeding compared with patients not on anticoagulants.1 Bleeding rates tend to be slightly higher in patients taking anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism than in those taking them for atrial fibrillation. The average yearly risk of a “major” anticoagulant-associated bleeding event (eg, requiring transfusion or intervention or occurring in a critical anatomic site) is about 2% to 3%, with most of the bleeding being gastrointestinal.2

Intracranial hemorrhage is by far the most deadly complication of anticoagulant therapy: it causes 90% of deaths and disability from warfarin-associated hemorrhage and is associated with a death rate over 50%; however, it is much less common than gastrointestinal bleeding.3 Anticoagulant therapy increases the risk of intracranial hemorrhage by only 0.2% per year.1

RISK-PREDICTION TOOLS HAVE LIMITATIONS

Not all patients have the same risk of bleeding when taking anticoagulants. Many factors in addition to advanced age have been associated with increased bleeding risk, including coexisting medical conditions (such as malignancy, prior stroke or bleeding event, and renal insufficiency), medications (particularly aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other antiplatelet drugs), and the timing and intensity of anticoagulation therapy.4

Scoring tools have been developed to identify patients at higher risk of bleeding (Table 1).4–9 The various schemes incorporate many of the same variables, such as older age, renal impairment, and history of bleeding, but some include additional risk factors while others are more parsimonious. They also differ in how individual risk factors are weighted to generate a final risk score.

In terms of predictive ability, none of the available risk schemes appears to be vastly superior, and their ability to predict hemorrhage is modest at best. There is also no universal or well-established threshold at which the risk of bleeding is so high that one would not consider anticoagulants. In fact, a “high-risk” patient may have an aggregate bleeding rate of only 4% to 6% per year. Using risk schemes such as ATRIA,5 HEMORR2HAGES,6 and HAS-BLED7 may be more useful because they provide an estimate of bleeding risk for each point on the scale.

Moreover, the current tools to predict bleeding risk have several other limitations. They were developed in patients already taking anticoagulants and so probably underestimate the actual risk of hemorrhage, as people who could not take anticoagulants were excluded, most likely because they were at high risk of bleeding. Therefore, bleeding risk tools probably apply best to a patient for whom anticoagulation can be considered.

Some clinical variables are necessarily broad. For example, “prior bleeding” is a risk factor included in several risk scores, but does not distinguish between massive variceal bleeding and minor hemorrhoidal bleeding.

Risk scores do not effectively predict intracranial hemorrhage.

Finally, these risk tools were developed in patients taking vitamin K antagonists, and it is not yet established that they can effectively predict hemorrhage related to other, newer anticoagulants.

WHEN DOES BLEEDING RISK OUTWEIGH ANTICOAGULATION BENEFIT?

For patients with atrial fibrillation, the net clinical benefit of anticoagulation (strokes prevented minus bleeding events induced) increases as the risk of stroke rises. Updated guidelines for managing atrial fibrillation now recommend anticoagulation for most patients.10

For most older patients with atrial fibrillation, the decision to anticoagulate may not change even if a bleeding risk tool indicates a high bleeding risk.11 For example, a patient with a history of ischemic stroke will generally derive more benefit than harm from anticoagulants. The primary exception is in patients with prior lobar intracranial hemorrhage, because of the high risk of rebleeding and the worse outcomes associated with intracranial hemorrhage.12 As a general rule, most patients with atrial fibrillation and an additional risk factor for stroke should be considered for anticoagulant therapy unless they have a history of lobar intracranial hemorrhage.

Anticoagulation may be deferred if the patient is at the lower end of the stroke risk spectrum and if the bleeding risk is calculated to be high. However, as noted before, current bleeding risk tools probably do not capture the experiences of patients at the extremes of high bleeding risk, so clinical judgment continues to be important. In addition, forgoing anticoagulation could be reasonable even in patients at high risk for recurrent stroke if their life expectancy is limited, if anticoagulation is unacceptably burdensome, or if it is not within their goals and preferences.

WHAT ABOUT FALL RISK?

Fall risk commonly deters clinicians from prescribing anticoagulants because of the fear of causing intracranial hemorrhage. In particular, falls increase the risk for subdural hematoma, which has a death rate comparable to that of ischemic stroke.13

Studies have had difficulty quantifying the exact risk associated with falls because these patients are less likely to be prescribed anticoagulants. One decision analysis estimated that a person would have to fall about 300 times per year before the risk of intracranial hemorrhage outweighed the benefits from stroke reduction.14 Studies have found that patients at high risk of falls have a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage, but that this risk is counterbalanced by an even greater risk of ischemic stroke.15

Therefore, if the baseline risk of ischemic stroke is high, anticoagulation is still favored.

WHEN SHOULD I USE A BLEEDING RISK TOOL?

Despite their limitations, bleeding risk tools are useful in clinical practice when estimates of bleeding risk affect clinical behavior. They are most helpful for patients at the lower end of the stroke or thromboembolism risk spectrum, where the decision to anticoagulate is strongly influenced by bleeding risk. Risk tools may also be helpful when counseling patients about their bleeding risk off and on anticoagulants.

Finally, recognizing that a patient is at high bleeding risk may lead the clinician to consider closer monitoring of anticoagulants or to implement strategies to reduce the risk.

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146:857–867.

- Lopes LC, Spencer FA, Neumann I, et al. Bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation patients taking vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013; 94:367–375.

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. Death and disability from warfarin-associated intracranial and extracranial hemorrhages. Am J Med 2007; 120:700–705.

- Lopes RD, Crowley MJ, Shah BR, et al. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 Aug. Report No.: 13-EHC113-EF.

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: the ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:395–401.

- Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF) Am Heart J 2006; 151:713–719.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010; 138:1093–1100.

- Beyth RJ, Quinn LM, Landefeld CS. Prospective evaluation of an index for predicting the risk of major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin. Am J Med 1998; 105:91–99.

- Nieto JA, Solano R, Iglesias NT, et al, for the RIETE Investigators. Validation of a score for predicting fatal bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism. Thrombosis Res 2013; 132:175–179.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014; 130:2071–2104.

- Singer DE, Chang Y, Fang MC, et al. The net clinical benefit of warfarin anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:297–305.

- Eckman MH, Rosand J, Knudsen KA, Singer DE, Greenberg SM. Can patients be anticoagulated after intracerebral hemorrhage? A decision analysis. Stroke 2003; 34:1710–1716.

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. Thirty-day mortality after ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation on and off anticoagulants. Stroke 2012; 43:1795–1799.

- Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A. Anticoagulant-related bleeding in older persons with atrial fibrillation: physicians' fears often unfounded. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:1580–1586.

- Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Kerzner R, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Rich MW. Incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation who are prone to fall. Am J Med 2005; 118:612–617.

We have tools to predict bleeding risk, but their predictive value is modest, and the estimated risk of bleeding is often outweighed by the benefits of anticoagulant therapy.

Anticoagulant therapy is commonly prescribed for conditions that disproportionately affect the elderly, including atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, and valvular heart disease. Though anticoagulants are highly effective in preventing clots, they also significantly increase the risk of bleeding. Since older age is a risk factor for bleeding as well as thrombosis, it is essential to weigh the risks and benefits of anticoagulants for each patient.

WHAT KINDS OF BLEEDING DEVELOP IN PATIENTS ON ANTICOAGULANTS?

Patients taking anticoagulants have roughly double the risk of bleeding compared with patients not on anticoagulants.1 Bleeding rates tend to be slightly higher in patients taking anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism than in those taking them for atrial fibrillation. The average yearly risk of a “major” anticoagulant-associated bleeding event (eg, requiring transfusion or intervention or occurring in a critical anatomic site) is about 2% to 3%, with most of the bleeding being gastrointestinal.2

Intracranial hemorrhage is by far the most deadly complication of anticoagulant therapy: it causes 90% of deaths and disability from warfarin-associated hemorrhage and is associated with a death rate over 50%; however, it is much less common than gastrointestinal bleeding.3 Anticoagulant therapy increases the risk of intracranial hemorrhage by only 0.2% per year.1

RISK-PREDICTION TOOLS HAVE LIMITATIONS

Not all patients have the same risk of bleeding when taking anticoagulants. Many factors in addition to advanced age have been associated with increased bleeding risk, including coexisting medical conditions (such as malignancy, prior stroke or bleeding event, and renal insufficiency), medications (particularly aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other antiplatelet drugs), and the timing and intensity of anticoagulation therapy.4

Scoring tools have been developed to identify patients at higher risk of bleeding (Table 1).4–9 The various schemes incorporate many of the same variables, such as older age, renal impairment, and history of bleeding, but some include additional risk factors while others are more parsimonious. They also differ in how individual risk factors are weighted to generate a final risk score.

In terms of predictive ability, none of the available risk schemes appears to be vastly superior, and their ability to predict hemorrhage is modest at best. There is also no universal or well-established threshold at which the risk of bleeding is so high that one would not consider anticoagulants. In fact, a “high-risk” patient may have an aggregate bleeding rate of only 4% to 6% per year. Using risk schemes such as ATRIA,5 HEMORR2HAGES,6 and HAS-BLED7 may be more useful because they provide an estimate of bleeding risk for each point on the scale.