User login

Draft recommendations back aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Doc groups say Medicare payment data need context

Credit: NIH

In an effort to make the US healthcare system more transparent, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released data on Medicare payments made to healthcare providers in 2012.

The CMS said the data provide the public with new insight into healthcare spending and physician practice patterns.

But physician groups argued that releasing the data without context—such as specific drivers of cost—could lead to misinterpretation.

The data set includes information for more than 880,000 distinct healthcare providers who collectively received $77 billion in Medicare payments in 2012, under the Medicare Part B Fee-For-Service program.

The CMS said these data make it possible to conduct a wide range of analyses that compare 6000 different types of services and procedures provided, as well as payments received by individual healthcare providers.

The information allows comparisons by physician, specialty, location, the types of medical service and procedures delivered, Medicare payment, and submitted charges.

“Currently, consumers have limited information about how physicians and other healthcare professionals practice medicine,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. “This data will help fill that gap by offering insight into the Medicare portion of a physician’s practice.”

The presidents of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and the American Medical Association (AMA) expressed less positive views about the data.

“While ASH supports greater transparency about Medicare physician payment and its potential to enhance the quality of the US healthcare system, the society strongly believes that this incredibly complex data must be released with appropriate disclosures and explanatory statements that will encourage and facilitate value-based consumer decision making,” said ASH President Linda J. Burns, MD.

“Specifically, the numbers alone will not explain quality of care or account for specific drivers of cost such as specialty, location, supply costs, and support staff. The release of data without placing these aspects of care and others into context may result in inaccurate and misleading information for consumers.”

For example, the data show that the highest-paid cardiologist (a physician in Ocala, Florida) received more than $18 million in Medicare payments, or nearly $23 million when totaling the amount Medicare pays, the deductible and co-insurance amounts the beneficiary pays, and any amounts a third party pays. And that $23 million figure is nearly 80 times higher than the average payment for a cardiologist in 2012.

While this high figure could be a result of improper billing, it might also be explained by a number of other factors. For instance, the physician might specialize in geriatric care and therefore receive nearly all his payments from Medicare, or the figure might include payments for staff, medical devices, tests, medications, and supplies.

“We believe that [CMS’s data set] has significant shortcomings regarding the accuracy and value of the medical services rendered by physicians,” said AMA President Ardis Dee Hoven, MD.

“Releasing the data without context will likely lead to inaccuracies, misinterpretations, false conclusions, and other unintended consequences. The AMA is disappointed that CMS did not include reasonable safeguards that would help the public understand the limitations of this data.”

The CMS did compile a document that lists the limitations of the data (eg, they might not be representative of a physician’s entire practice). This document and the complete data set are available for download from the CMS website. ![]()

Credit: NIH

In an effort to make the US healthcare system more transparent, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released data on Medicare payments made to healthcare providers in 2012.

The CMS said the data provide the public with new insight into healthcare spending and physician practice patterns.

But physician groups argued that releasing the data without context—such as specific drivers of cost—could lead to misinterpretation.

The data set includes information for more than 880,000 distinct healthcare providers who collectively received $77 billion in Medicare payments in 2012, under the Medicare Part B Fee-For-Service program.

The CMS said these data make it possible to conduct a wide range of analyses that compare 6000 different types of services and procedures provided, as well as payments received by individual healthcare providers.

The information allows comparisons by physician, specialty, location, the types of medical service and procedures delivered, Medicare payment, and submitted charges.

“Currently, consumers have limited information about how physicians and other healthcare professionals practice medicine,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. “This data will help fill that gap by offering insight into the Medicare portion of a physician’s practice.”

The presidents of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and the American Medical Association (AMA) expressed less positive views about the data.

“While ASH supports greater transparency about Medicare physician payment and its potential to enhance the quality of the US healthcare system, the society strongly believes that this incredibly complex data must be released with appropriate disclosures and explanatory statements that will encourage and facilitate value-based consumer decision making,” said ASH President Linda J. Burns, MD.

“Specifically, the numbers alone will not explain quality of care or account for specific drivers of cost such as specialty, location, supply costs, and support staff. The release of data without placing these aspects of care and others into context may result in inaccurate and misleading information for consumers.”

For example, the data show that the highest-paid cardiologist (a physician in Ocala, Florida) received more than $18 million in Medicare payments, or nearly $23 million when totaling the amount Medicare pays, the deductible and co-insurance amounts the beneficiary pays, and any amounts a third party pays. And that $23 million figure is nearly 80 times higher than the average payment for a cardiologist in 2012.

While this high figure could be a result of improper billing, it might also be explained by a number of other factors. For instance, the physician might specialize in geriatric care and therefore receive nearly all his payments from Medicare, or the figure might include payments for staff, medical devices, tests, medications, and supplies.

“We believe that [CMS’s data set] has significant shortcomings regarding the accuracy and value of the medical services rendered by physicians,” said AMA President Ardis Dee Hoven, MD.

“Releasing the data without context will likely lead to inaccuracies, misinterpretations, false conclusions, and other unintended consequences. The AMA is disappointed that CMS did not include reasonable safeguards that would help the public understand the limitations of this data.”

The CMS did compile a document that lists the limitations of the data (eg, they might not be representative of a physician’s entire practice). This document and the complete data set are available for download from the CMS website. ![]()

Credit: NIH

In an effort to make the US healthcare system more transparent, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released data on Medicare payments made to healthcare providers in 2012.

The CMS said the data provide the public with new insight into healthcare spending and physician practice patterns.

But physician groups argued that releasing the data without context—such as specific drivers of cost—could lead to misinterpretation.

The data set includes information for more than 880,000 distinct healthcare providers who collectively received $77 billion in Medicare payments in 2012, under the Medicare Part B Fee-For-Service program.

The CMS said these data make it possible to conduct a wide range of analyses that compare 6000 different types of services and procedures provided, as well as payments received by individual healthcare providers.

The information allows comparisons by physician, specialty, location, the types of medical service and procedures delivered, Medicare payment, and submitted charges.

“Currently, consumers have limited information about how physicians and other healthcare professionals practice medicine,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. “This data will help fill that gap by offering insight into the Medicare portion of a physician’s practice.”

The presidents of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and the American Medical Association (AMA) expressed less positive views about the data.

“While ASH supports greater transparency about Medicare physician payment and its potential to enhance the quality of the US healthcare system, the society strongly believes that this incredibly complex data must be released with appropriate disclosures and explanatory statements that will encourage and facilitate value-based consumer decision making,” said ASH President Linda J. Burns, MD.

“Specifically, the numbers alone will not explain quality of care or account for specific drivers of cost such as specialty, location, supply costs, and support staff. The release of data without placing these aspects of care and others into context may result in inaccurate and misleading information for consumers.”

For example, the data show that the highest-paid cardiologist (a physician in Ocala, Florida) received more than $18 million in Medicare payments, or nearly $23 million when totaling the amount Medicare pays, the deductible and co-insurance amounts the beneficiary pays, and any amounts a third party pays. And that $23 million figure is nearly 80 times higher than the average payment for a cardiologist in 2012.

While this high figure could be a result of improper billing, it might also be explained by a number of other factors. For instance, the physician might specialize in geriatric care and therefore receive nearly all his payments from Medicare, or the figure might include payments for staff, medical devices, tests, medications, and supplies.

“We believe that [CMS’s data set] has significant shortcomings regarding the accuracy and value of the medical services rendered by physicians,” said AMA President Ardis Dee Hoven, MD.

“Releasing the data without context will likely lead to inaccuracies, misinterpretations, false conclusions, and other unintended consequences. The AMA is disappointed that CMS did not include reasonable safeguards that would help the public understand the limitations of this data.”

The CMS did compile a document that lists the limitations of the data (eg, they might not be representative of a physician’s entire practice). This document and the complete data set are available for download from the CMS website. ![]()

Compound is potent FLT3 inhibitor, team says

Credit: Rhoda Baer

An experimental compound called TTT-3002 could be “one of the most potent FLT3 inhibitors to date,” according to researchers.

In preclinical experiments, TTT-3002 proved more active than the most potent FLT3 inhibitor currently in clinical trials.

TTT-3002 blocked FLT3 activity in human FLT3/ITD mutant leukemia cell lines, prolonged survival in a mouse model of FLT3-associated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and proved toxic to leukemic cells from patients with AML.

Donald Small, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

“We’re very excited about TTT-3002, because it appears in our tests so far to be the most potent FLT3 inhibitor to date,” Dr Small said. “It showed activity against FLT3-mutated cells taken from patients and with minimal toxicity to normal bone marrow cells, making it a promising new candidate for the treatment of AML.”

In a series of experiments, the researchers found that the amount of TTT-3002 needed to block FLT3 activity in human leukemia cell lines was 6- to 7-fold lower than for ACC220, the most potent FLT3 inhibitor currently in clinical trials.

TTT-3002 also inhibited proteins made by genes further down the FLT3 signaling pathway, including STAT5, AKT, and MAPK. And it showed activity against the most frequently occurring FLT3 mutations, FLT3/ITD and FLT3/D835Y. (Many other inhibitors are ineffective against FLT3/D835Y mutations.)

When the researchers tested TTT-3002 in a mouse model of leukemia, they found the drug eliminated the presence of leukemic cells within 10 days of treatment.

Mice lived an average of more than 100 days after TTT-3002 treatment and resumed normal bone marrow activity. In comparison, mice treated with a placebo died an average of 18 days after treatment.

The researchers also found that TTT-3002 was toxic to leukemia samples taken from newly diagnosed and relapsed patients with AML, but it did not affect normal bone marrow cells taken from healthy donors.

A single dose of TTT-3002 caused more than 90% inhibition against FLT3 signaling that lasted for 12 hours. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

An experimental compound called TTT-3002 could be “one of the most potent FLT3 inhibitors to date,” according to researchers.

In preclinical experiments, TTT-3002 proved more active than the most potent FLT3 inhibitor currently in clinical trials.

TTT-3002 blocked FLT3 activity in human FLT3/ITD mutant leukemia cell lines, prolonged survival in a mouse model of FLT3-associated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and proved toxic to leukemic cells from patients with AML.

Donald Small, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

“We’re very excited about TTT-3002, because it appears in our tests so far to be the most potent FLT3 inhibitor to date,” Dr Small said. “It showed activity against FLT3-mutated cells taken from patients and with minimal toxicity to normal bone marrow cells, making it a promising new candidate for the treatment of AML.”

In a series of experiments, the researchers found that the amount of TTT-3002 needed to block FLT3 activity in human leukemia cell lines was 6- to 7-fold lower than for ACC220, the most potent FLT3 inhibitor currently in clinical trials.

TTT-3002 also inhibited proteins made by genes further down the FLT3 signaling pathway, including STAT5, AKT, and MAPK. And it showed activity against the most frequently occurring FLT3 mutations, FLT3/ITD and FLT3/D835Y. (Many other inhibitors are ineffective against FLT3/D835Y mutations.)

When the researchers tested TTT-3002 in a mouse model of leukemia, they found the drug eliminated the presence of leukemic cells within 10 days of treatment.

Mice lived an average of more than 100 days after TTT-3002 treatment and resumed normal bone marrow activity. In comparison, mice treated with a placebo died an average of 18 days after treatment.

The researchers also found that TTT-3002 was toxic to leukemia samples taken from newly diagnosed and relapsed patients with AML, but it did not affect normal bone marrow cells taken from healthy donors.

A single dose of TTT-3002 caused more than 90% inhibition against FLT3 signaling that lasted for 12 hours. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

An experimental compound called TTT-3002 could be “one of the most potent FLT3 inhibitors to date,” according to researchers.

In preclinical experiments, TTT-3002 proved more active than the most potent FLT3 inhibitor currently in clinical trials.

TTT-3002 blocked FLT3 activity in human FLT3/ITD mutant leukemia cell lines, prolonged survival in a mouse model of FLT3-associated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and proved toxic to leukemic cells from patients with AML.

Donald Small, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

“We’re very excited about TTT-3002, because it appears in our tests so far to be the most potent FLT3 inhibitor to date,” Dr Small said. “It showed activity against FLT3-mutated cells taken from patients and with minimal toxicity to normal bone marrow cells, making it a promising new candidate for the treatment of AML.”

In a series of experiments, the researchers found that the amount of TTT-3002 needed to block FLT3 activity in human leukemia cell lines was 6- to 7-fold lower than for ACC220, the most potent FLT3 inhibitor currently in clinical trials.

TTT-3002 also inhibited proteins made by genes further down the FLT3 signaling pathway, including STAT5, AKT, and MAPK. And it showed activity against the most frequently occurring FLT3 mutations, FLT3/ITD and FLT3/D835Y. (Many other inhibitors are ineffective against FLT3/D835Y mutations.)

When the researchers tested TTT-3002 in a mouse model of leukemia, they found the drug eliminated the presence of leukemic cells within 10 days of treatment.

Mice lived an average of more than 100 days after TTT-3002 treatment and resumed normal bone marrow activity. In comparison, mice treated with a placebo died an average of 18 days after treatment.

The researchers also found that TTT-3002 was toxic to leukemia samples taken from newly diagnosed and relapsed patients with AML, but it did not affect normal bone marrow cells taken from healthy donors.

A single dose of TTT-3002 caused more than 90% inhibition against FLT3 signaling that lasted for 12 hours. ![]()

How NK cells kill abnormal blood cells

Credit: Bjorn Onfelt/Dan Davis

New research provides additional insight into how natural killer (NK) cells eliminate abnormal hematopoietic cells.

The investigators evaluated 2 molecules that are known to play important roles in this process.

Ewing’s sarcoma-associated transcript 2 (EAT-2) and signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM)–associated protein (SAP) are expressed in NK cells, and their combined expression is essential for NK cells to kill abnormal hematopoietic cells.

“We knew that EAT-2 cooperates with SAP, and, with this research project, we wanted to better understand why they are both required for the proper functioning of NK cells,” said study author André Veillette, PhD, of the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) in Canada.

Dr Veillette and his colleagues described this research in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We identified the molecular chain of events that occur and showed that EAT-2 and SAP perform different functions using distinct mechanisms,” Dr Veillette said. “These findings explain the cooperative and essential function of these 2 molecules in activating NK cells, thereby allowing them to kill abnormal blood cells.”

The investigators noted that SAP couples SLAM family receptors to the protein tyrosine kinase Fyn and the exchange factor Vav, thereby promoting conjugate formation between NK cells and target hematopoietic cells.

EAT-2, on the other hand, works by accelerating the polarization and exocytosis of cytotoxic granules toward hematopoietic cells.

EAT-2 mediates its effects in NK cells by linking SLAM family receptors to phospholipase Cγ, calcium fluxes, and Erk kinase. These signals are triggered by 1 or 2 tyrosines that are located in the carboxyl-terminal tail of EAT-2.

Dr Veillete pointed out that, although EAT-2 and SAP behave differently, both are linked to receptors of the SLAM family on the cell surface.

“Because they can make better drug targets, our future work will focus on these receptors,” he said, “which could eventually lead to identifying new potential treatment avenues for blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma.” ![]()

Credit: Bjorn Onfelt/Dan Davis

New research provides additional insight into how natural killer (NK) cells eliminate abnormal hematopoietic cells.

The investigators evaluated 2 molecules that are known to play important roles in this process.

Ewing’s sarcoma-associated transcript 2 (EAT-2) and signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM)–associated protein (SAP) are expressed in NK cells, and their combined expression is essential for NK cells to kill abnormal hematopoietic cells.

“We knew that EAT-2 cooperates with SAP, and, with this research project, we wanted to better understand why they are both required for the proper functioning of NK cells,” said study author André Veillette, PhD, of the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) in Canada.

Dr Veillette and his colleagues described this research in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We identified the molecular chain of events that occur and showed that EAT-2 and SAP perform different functions using distinct mechanisms,” Dr Veillette said. “These findings explain the cooperative and essential function of these 2 molecules in activating NK cells, thereby allowing them to kill abnormal blood cells.”

The investigators noted that SAP couples SLAM family receptors to the protein tyrosine kinase Fyn and the exchange factor Vav, thereby promoting conjugate formation between NK cells and target hematopoietic cells.

EAT-2, on the other hand, works by accelerating the polarization and exocytosis of cytotoxic granules toward hematopoietic cells.

EAT-2 mediates its effects in NK cells by linking SLAM family receptors to phospholipase Cγ, calcium fluxes, and Erk kinase. These signals are triggered by 1 or 2 tyrosines that are located in the carboxyl-terminal tail of EAT-2.

Dr Veillete pointed out that, although EAT-2 and SAP behave differently, both are linked to receptors of the SLAM family on the cell surface.

“Because they can make better drug targets, our future work will focus on these receptors,” he said, “which could eventually lead to identifying new potential treatment avenues for blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma.” ![]()

Credit: Bjorn Onfelt/Dan Davis

New research provides additional insight into how natural killer (NK) cells eliminate abnormal hematopoietic cells.

The investigators evaluated 2 molecules that are known to play important roles in this process.

Ewing’s sarcoma-associated transcript 2 (EAT-2) and signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM)–associated protein (SAP) are expressed in NK cells, and their combined expression is essential for NK cells to kill abnormal hematopoietic cells.

“We knew that EAT-2 cooperates with SAP, and, with this research project, we wanted to better understand why they are both required for the proper functioning of NK cells,” said study author André Veillette, PhD, of the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) in Canada.

Dr Veillette and his colleagues described this research in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We identified the molecular chain of events that occur and showed that EAT-2 and SAP perform different functions using distinct mechanisms,” Dr Veillette said. “These findings explain the cooperative and essential function of these 2 molecules in activating NK cells, thereby allowing them to kill abnormal blood cells.”

The investigators noted that SAP couples SLAM family receptors to the protein tyrosine kinase Fyn and the exchange factor Vav, thereby promoting conjugate formation between NK cells and target hematopoietic cells.

EAT-2, on the other hand, works by accelerating the polarization and exocytosis of cytotoxic granules toward hematopoietic cells.

EAT-2 mediates its effects in NK cells by linking SLAM family receptors to phospholipase Cγ, calcium fluxes, and Erk kinase. These signals are triggered by 1 or 2 tyrosines that are located in the carboxyl-terminal tail of EAT-2.

Dr Veillete pointed out that, although EAT-2 and SAP behave differently, both are linked to receptors of the SLAM family on the cell surface.

“Because they can make better drug targets, our future work will focus on these receptors,” he said, “which could eventually lead to identifying new potential treatment avenues for blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma.” ![]()

More ways to make the most of lasers in clinical practice

PHOENIX – What’s the latest in lasers? The most stubborn tattoos – those with blue or green ink – are now the easiest to remove with new laser technology and techniques. Microwave treatment for armpit hair is a real option, even on difficult-to-remove blond hair. Cutaneous laser expert Dr. Roy Geronemus, director of the Laser and Skin Surgery Center of New York, describes what dermatologists need to know about these and other innovative cosmetic treatments in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

But that’s not all. More data support the use of lasers for common medical conditions, says Dr. Geronemus. Hear his description of how the same new laser used for tattoo removal can be a noninvasive treatment to reduce either hypertrophic or atrophic scarring in any skin type, with practically no downtime. He also explains several new approaches that show promise as acne therapy.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

PHOENIX – What’s the latest in lasers? The most stubborn tattoos – those with blue or green ink – are now the easiest to remove with new laser technology and techniques. Microwave treatment for armpit hair is a real option, even on difficult-to-remove blond hair. Cutaneous laser expert Dr. Roy Geronemus, director of the Laser and Skin Surgery Center of New York, describes what dermatologists need to know about these and other innovative cosmetic treatments in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

But that’s not all. More data support the use of lasers for common medical conditions, says Dr. Geronemus. Hear his description of how the same new laser used for tattoo removal can be a noninvasive treatment to reduce either hypertrophic or atrophic scarring in any skin type, with practically no downtime. He also explains several new approaches that show promise as acne therapy.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

PHOENIX – What’s the latest in lasers? The most stubborn tattoos – those with blue or green ink – are now the easiest to remove with new laser technology and techniques. Microwave treatment for armpit hair is a real option, even on difficult-to-remove blond hair. Cutaneous laser expert Dr. Roy Geronemus, director of the Laser and Skin Surgery Center of New York, describes what dermatologists need to know about these and other innovative cosmetic treatments in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

But that’s not all. More data support the use of lasers for common medical conditions, says Dr. Geronemus. Hear his description of how the same new laser used for tattoo removal can be a noninvasive treatment to reduce either hypertrophic or atrophic scarring in any skin type, with practically no downtime. He also explains several new approaches that show promise as acne therapy.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT LASER 2014

HM 14 Special Report: Care of the Hospitalized Patient with Diabetes

Presenter:

Eric Felner, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatric Endocrinology and Director of the Pediatric Endocrine Fellowship Program at Emory University

Espousing a “3-Bag Theory of DKA management,” Dr. Eric Fellner presented an update of the inpatient management of diabetes mellitus at SHM 2014. This approach to dKA involves maintenance IV fluids based on BSA after fluid resuscitation, with variable proportions of ½ NS and D10 ½ NS with potassium chloride/potassium phosphate, and insulin given intravenously. This approach can reduce costs by avoiding multiple changes in IV fluid solution bags, and avoids multiple mistake-prone calculations. He recommends all patients with DKA under the age of 5 years be admitted to the PICU. Constant monitoring of lab values, glucose, vital signs, and clinical condition is also required. In general, insulin boluses do not provide a benefit over insulin drip alone, and use of bicarbonate remains controversial.

Although it is somewhat controversial as to whether all new type 1 diabetics need to be admitted, Dr. Felner favored admission due to improved teaching of patients/families, evaluation of the proposed insulin and carbohydrate regimen, and identification of potential insurance and social problems. Type 2 diabetics rarely get admitted for diabetic complications, but there are increasing numbers admitted for hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist with the University of San Diego Medical Center and Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, and the pediatric editor for The Hospitalist.

Presenter:

Eric Felner, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatric Endocrinology and Director of the Pediatric Endocrine Fellowship Program at Emory University

Espousing a “3-Bag Theory of DKA management,” Dr. Eric Fellner presented an update of the inpatient management of diabetes mellitus at SHM 2014. This approach to dKA involves maintenance IV fluids based on BSA after fluid resuscitation, with variable proportions of ½ NS and D10 ½ NS with potassium chloride/potassium phosphate, and insulin given intravenously. This approach can reduce costs by avoiding multiple changes in IV fluid solution bags, and avoids multiple mistake-prone calculations. He recommends all patients with DKA under the age of 5 years be admitted to the PICU. Constant monitoring of lab values, glucose, vital signs, and clinical condition is also required. In general, insulin boluses do not provide a benefit over insulin drip alone, and use of bicarbonate remains controversial.

Although it is somewhat controversial as to whether all new type 1 diabetics need to be admitted, Dr. Felner favored admission due to improved teaching of patients/families, evaluation of the proposed insulin and carbohydrate regimen, and identification of potential insurance and social problems. Type 2 diabetics rarely get admitted for diabetic complications, but there are increasing numbers admitted for hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist with the University of San Diego Medical Center and Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, and the pediatric editor for The Hospitalist.

Presenter:

Eric Felner, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatric Endocrinology and Director of the Pediatric Endocrine Fellowship Program at Emory University

Espousing a “3-Bag Theory of DKA management,” Dr. Eric Fellner presented an update of the inpatient management of diabetes mellitus at SHM 2014. This approach to dKA involves maintenance IV fluids based on BSA after fluid resuscitation, with variable proportions of ½ NS and D10 ½ NS with potassium chloride/potassium phosphate, and insulin given intravenously. This approach can reduce costs by avoiding multiple changes in IV fluid solution bags, and avoids multiple mistake-prone calculations. He recommends all patients with DKA under the age of 5 years be admitted to the PICU. Constant monitoring of lab values, glucose, vital signs, and clinical condition is also required. In general, insulin boluses do not provide a benefit over insulin drip alone, and use of bicarbonate remains controversial.

Although it is somewhat controversial as to whether all new type 1 diabetics need to be admitted, Dr. Felner favored admission due to improved teaching of patients/families, evaluation of the proposed insulin and carbohydrate regimen, and identification of potential insurance and social problems. Type 2 diabetics rarely get admitted for diabetic complications, but there are increasing numbers admitted for hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist with the University of San Diego Medical Center and Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, and the pediatric editor for The Hospitalist.

Hormone therapy may decrease risk of NHL

SAN DIEGO—The use of hormone therapy may lower the risk of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in menopausal women, according to a presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

Researchers found that menopausal women who used hormone therapy were about 30% less likely than their untreated peers to develop NHL.

And the risk of NHL decreased further if a woman began receiving hormone therapy at a younger age and used it for a longer period of time.

Sophia Wang, PhD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, presented these findings at the meeting as abstract 2918.

“The connection between lymphomas and menopausal hormone therapy use hinges on understanding the disease’s biology and the window of susceptibility,” Dr Wang said. “Hormone therapy is of interest because the loss of estrogen coupled with aging in women result in decreased immune function, which can elevate the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.”

For this study, Dr Wang and her colleagues examined data from the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program. They compared 685 postmenopausal women diagnosed with B-cell NHL to 685 postmenopausal women without lymphoma.

The researchers assessed the women’s use of menopausal hormone therapy, which included estrogen alone or estrogen with progestin in pill, patch, topical cream, or injected forms.

After controlling for factors such as age, race, and socioeconomic status, Dr Wang and her colleagues found that women who reported using any form of menopausal hormone therapy were approximately 30% less likely to be diagnosed with B-cell NHL, compared to women who reported never using hormone therapy.

An additional analysis showed that the risk reduction was even greater for women who initiated menopausal hormone therapy at 45 years of age or younger and used it for at least 5 years.

This group was approximately 40% less likely to be diagnosed with B-cell NHL compared to those who had never used hormone therapy.

Dr Wang said further research is needed to determine the exact biological mechanisms that might be linked to a lower NHL risk. These mechanisms could include supporting a healthy immune system or reducing inflammation.

She also cautioned that these findings are preliminary and should not change current recommendations and guidelines for menopausal hormone therapy use.

Due to well-established evidence tying menopausal hormone therapy to elevated risks of breast and endometrial cancers, the American Cancer Society recommends that women considering or using this therapy do so at the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time needed and that they discuss with their physicians other treatments to alleviate menopausal symptoms. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—The use of hormone therapy may lower the risk of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in menopausal women, according to a presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

Researchers found that menopausal women who used hormone therapy were about 30% less likely than their untreated peers to develop NHL.

And the risk of NHL decreased further if a woman began receiving hormone therapy at a younger age and used it for a longer period of time.

Sophia Wang, PhD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, presented these findings at the meeting as abstract 2918.

“The connection between lymphomas and menopausal hormone therapy use hinges on understanding the disease’s biology and the window of susceptibility,” Dr Wang said. “Hormone therapy is of interest because the loss of estrogen coupled with aging in women result in decreased immune function, which can elevate the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.”

For this study, Dr Wang and her colleagues examined data from the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program. They compared 685 postmenopausal women diagnosed with B-cell NHL to 685 postmenopausal women without lymphoma.

The researchers assessed the women’s use of menopausal hormone therapy, which included estrogen alone or estrogen with progestin in pill, patch, topical cream, or injected forms.

After controlling for factors such as age, race, and socioeconomic status, Dr Wang and her colleagues found that women who reported using any form of menopausal hormone therapy were approximately 30% less likely to be diagnosed with B-cell NHL, compared to women who reported never using hormone therapy.

An additional analysis showed that the risk reduction was even greater for women who initiated menopausal hormone therapy at 45 years of age or younger and used it for at least 5 years.

This group was approximately 40% less likely to be diagnosed with B-cell NHL compared to those who had never used hormone therapy.

Dr Wang said further research is needed to determine the exact biological mechanisms that might be linked to a lower NHL risk. These mechanisms could include supporting a healthy immune system or reducing inflammation.

She also cautioned that these findings are preliminary and should not change current recommendations and guidelines for menopausal hormone therapy use.

Due to well-established evidence tying menopausal hormone therapy to elevated risks of breast and endometrial cancers, the American Cancer Society recommends that women considering or using this therapy do so at the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time needed and that they discuss with their physicians other treatments to alleviate menopausal symptoms. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—The use of hormone therapy may lower the risk of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in menopausal women, according to a presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

Researchers found that menopausal women who used hormone therapy were about 30% less likely than their untreated peers to develop NHL.

And the risk of NHL decreased further if a woman began receiving hormone therapy at a younger age and used it for a longer period of time.

Sophia Wang, PhD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, presented these findings at the meeting as abstract 2918.

“The connection between lymphomas and menopausal hormone therapy use hinges on understanding the disease’s biology and the window of susceptibility,” Dr Wang said. “Hormone therapy is of interest because the loss of estrogen coupled with aging in women result in decreased immune function, which can elevate the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.”

For this study, Dr Wang and her colleagues examined data from the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program. They compared 685 postmenopausal women diagnosed with B-cell NHL to 685 postmenopausal women without lymphoma.

The researchers assessed the women’s use of menopausal hormone therapy, which included estrogen alone or estrogen with progestin in pill, patch, topical cream, or injected forms.

After controlling for factors such as age, race, and socioeconomic status, Dr Wang and her colleagues found that women who reported using any form of menopausal hormone therapy were approximately 30% less likely to be diagnosed with B-cell NHL, compared to women who reported never using hormone therapy.

An additional analysis showed that the risk reduction was even greater for women who initiated menopausal hormone therapy at 45 years of age or younger and used it for at least 5 years.

This group was approximately 40% less likely to be diagnosed with B-cell NHL compared to those who had never used hormone therapy.

Dr Wang said further research is needed to determine the exact biological mechanisms that might be linked to a lower NHL risk. These mechanisms could include supporting a healthy immune system or reducing inflammation.

She also cautioned that these findings are preliminary and should not change current recommendations and guidelines for menopausal hormone therapy use.

Due to well-established evidence tying menopausal hormone therapy to elevated risks of breast and endometrial cancers, the American Cancer Society recommends that women considering or using this therapy do so at the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time needed and that they discuss with their physicians other treatments to alleviate menopausal symptoms. ![]()

FDA approves new indications for dabigatran

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for the treatment and prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients who have already received anticoagulation therapy.

The drug is now approved to treat DVT and PE in patients who have received parenteral anticoagulant therapy for 5 to 10 days.

And it is approved as prophylaxis to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE in previously treated patients.

The FDA’s approval of dabigatran is based on the results of four phase 3 trials.

The first of these, the RE-COVER trial, was published in NEJM in 2009. The results suggested that a fixed dose of dabigatran was as effective as warfarin for treating acute venous thromboembolism (VTE). And the safety profiles of the 2 drugs were deemed similar.

Data from a second trial, RE-SONATE, indicated that dabigatran was significantly more effective than placebo as long-term VTE prophylaxis. But the anticoagulant posed a higher risk of clinically relevant bleeding.

Results from the third trial, RE-MEDY, suggested dabigatran was non-inferior to warfarin as VTE prophylaxis. And warfarin conferred a higher risk of clinically relevant bleeding.

Both RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE were published in NEJM last year.

Data from the fourth trial, RE-COVER II, indicated that dabigatran had a similar effect on VTE recurrence and a lower risk of bleeding than warfarin when used to treat acute VTE. These results were published in Circulation last year.

Dabigatran is already approved by the FDA as prophylaxis for stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. The drug is marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for the treatment and prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients who have already received anticoagulation therapy.

The drug is now approved to treat DVT and PE in patients who have received parenteral anticoagulant therapy for 5 to 10 days.

And it is approved as prophylaxis to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE in previously treated patients.

The FDA’s approval of dabigatran is based on the results of four phase 3 trials.

The first of these, the RE-COVER trial, was published in NEJM in 2009. The results suggested that a fixed dose of dabigatran was as effective as warfarin for treating acute venous thromboembolism (VTE). And the safety profiles of the 2 drugs were deemed similar.

Data from a second trial, RE-SONATE, indicated that dabigatran was significantly more effective than placebo as long-term VTE prophylaxis. But the anticoagulant posed a higher risk of clinically relevant bleeding.

Results from the third trial, RE-MEDY, suggested dabigatran was non-inferior to warfarin as VTE prophylaxis. And warfarin conferred a higher risk of clinically relevant bleeding.

Both RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE were published in NEJM last year.

Data from the fourth trial, RE-COVER II, indicated that dabigatran had a similar effect on VTE recurrence and a lower risk of bleeding than warfarin when used to treat acute VTE. These results were published in Circulation last year.

Dabigatran is already approved by the FDA as prophylaxis for stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. The drug is marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for the treatment and prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients who have already received anticoagulation therapy.

The drug is now approved to treat DVT and PE in patients who have received parenteral anticoagulant therapy for 5 to 10 days.

And it is approved as prophylaxis to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE in previously treated patients.

The FDA’s approval of dabigatran is based on the results of four phase 3 trials.

The first of these, the RE-COVER trial, was published in NEJM in 2009. The results suggested that a fixed dose of dabigatran was as effective as warfarin for treating acute venous thromboembolism (VTE). And the safety profiles of the 2 drugs were deemed similar.

Data from a second trial, RE-SONATE, indicated that dabigatran was significantly more effective than placebo as long-term VTE prophylaxis. But the anticoagulant posed a higher risk of clinically relevant bleeding.

Results from the third trial, RE-MEDY, suggested dabigatran was non-inferior to warfarin as VTE prophylaxis. And warfarin conferred a higher risk of clinically relevant bleeding.

Both RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE were published in NEJM last year.

Data from the fourth trial, RE-COVER II, indicated that dabigatran had a similar effect on VTE recurrence and a lower risk of bleeding than warfarin when used to treat acute VTE. These results were published in Circulation last year.

Dabigatran is already approved by the FDA as prophylaxis for stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. The drug is marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim. ![]()

Targeting sperm protection to combat malaria

Credit: CDC

New research has revealed a strategy for impairing fertility in malaria-carrying mosquitoes, potentially providing a tactic for combatting the disease.

Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes are the main transmitters of malaria, and the females mate only once during their lives.

They store the sperm from this single mating in an organ called the spermatheca, from which they repeatedly take sperm over the course of their lifetime to fertilize the eggs they lay.

The new research, published in PNAS, reveals that the sperm are partly protected by the actions of an enzyme called HPX15.

When researchers interfered with HPX15 in female A gambiae mosquitoes in the lab, the mosquitoes fertilized fewer eggs and, therefore, produced fewer offspring.

The team injected the female mosquitoes with an inhibitor to reduce the levels of HPX15. Normally, around 3% of the eggs a female lays do not develop into offspring. When the researchers reduced the levels of HPX15 in female mosquitoes, 20% of the mosquitoes’ eggs were infertile.

“[W]e reduced the number of offspring by a fifth, and that’s not a huge reduction,” said study author Flaminia Catteruccia, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston and the University of Perugia in Italy.

“But mosquitoes in the laboratory are subjected to much less stress than those in the wild, so we suspect that this kind of intervention would have a bigger impact on the fertility of wild mosquitoes. That’s something we would ultimately hope to investigate.”

The researchers also discovered how HPX15 is activated, suggesting another possible target for immobilizing the enzyme. The male mosquito transfers the hormone 20E to the female during mating, and it is this hormone that induces the expression of HPX15 in the female.

“The next step for this research is to think about how we could prevent activation of either the enzyme that protects the sperm, HPX15, or of the male trigger, 20E, that kicks that enzyme into action,” Dr Catteruccia said. “There may also be other pathways that we could target, and this is something that we’re keen to investigate.” ![]()

Credit: CDC

New research has revealed a strategy for impairing fertility in malaria-carrying mosquitoes, potentially providing a tactic for combatting the disease.

Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes are the main transmitters of malaria, and the females mate only once during their lives.

They store the sperm from this single mating in an organ called the spermatheca, from which they repeatedly take sperm over the course of their lifetime to fertilize the eggs they lay.

The new research, published in PNAS, reveals that the sperm are partly protected by the actions of an enzyme called HPX15.

When researchers interfered with HPX15 in female A gambiae mosquitoes in the lab, the mosquitoes fertilized fewer eggs and, therefore, produced fewer offspring.

The team injected the female mosquitoes with an inhibitor to reduce the levels of HPX15. Normally, around 3% of the eggs a female lays do not develop into offspring. When the researchers reduced the levels of HPX15 in female mosquitoes, 20% of the mosquitoes’ eggs were infertile.

“[W]e reduced the number of offspring by a fifth, and that’s not a huge reduction,” said study author Flaminia Catteruccia, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston and the University of Perugia in Italy.

“But mosquitoes in the laboratory are subjected to much less stress than those in the wild, so we suspect that this kind of intervention would have a bigger impact on the fertility of wild mosquitoes. That’s something we would ultimately hope to investigate.”

The researchers also discovered how HPX15 is activated, suggesting another possible target for immobilizing the enzyme. The male mosquito transfers the hormone 20E to the female during mating, and it is this hormone that induces the expression of HPX15 in the female.

“The next step for this research is to think about how we could prevent activation of either the enzyme that protects the sperm, HPX15, or of the male trigger, 20E, that kicks that enzyme into action,” Dr Catteruccia said. “There may also be other pathways that we could target, and this is something that we’re keen to investigate.” ![]()

Credit: CDC

New research has revealed a strategy for impairing fertility in malaria-carrying mosquitoes, potentially providing a tactic for combatting the disease.

Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes are the main transmitters of malaria, and the females mate only once during their lives.

They store the sperm from this single mating in an organ called the spermatheca, from which they repeatedly take sperm over the course of their lifetime to fertilize the eggs they lay.

The new research, published in PNAS, reveals that the sperm are partly protected by the actions of an enzyme called HPX15.

When researchers interfered with HPX15 in female A gambiae mosquitoes in the lab, the mosquitoes fertilized fewer eggs and, therefore, produced fewer offspring.

The team injected the female mosquitoes with an inhibitor to reduce the levels of HPX15. Normally, around 3% of the eggs a female lays do not develop into offspring. When the researchers reduced the levels of HPX15 in female mosquitoes, 20% of the mosquitoes’ eggs were infertile.

“[W]e reduced the number of offspring by a fifth, and that’s not a huge reduction,” said study author Flaminia Catteruccia, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston and the University of Perugia in Italy.

“But mosquitoes in the laboratory are subjected to much less stress than those in the wild, so we suspect that this kind of intervention would have a bigger impact on the fertility of wild mosquitoes. That’s something we would ultimately hope to investigate.”

The researchers also discovered how HPX15 is activated, suggesting another possible target for immobilizing the enzyme. The male mosquito transfers the hormone 20E to the female during mating, and it is this hormone that induces the expression of HPX15 in the female.

“The next step for this research is to think about how we could prevent activation of either the enzyme that protects the sperm, HPX15, or of the male trigger, 20E, that kicks that enzyme into action,” Dr Catteruccia said. “There may also be other pathways that we could target, and this is something that we’re keen to investigate.” ![]()

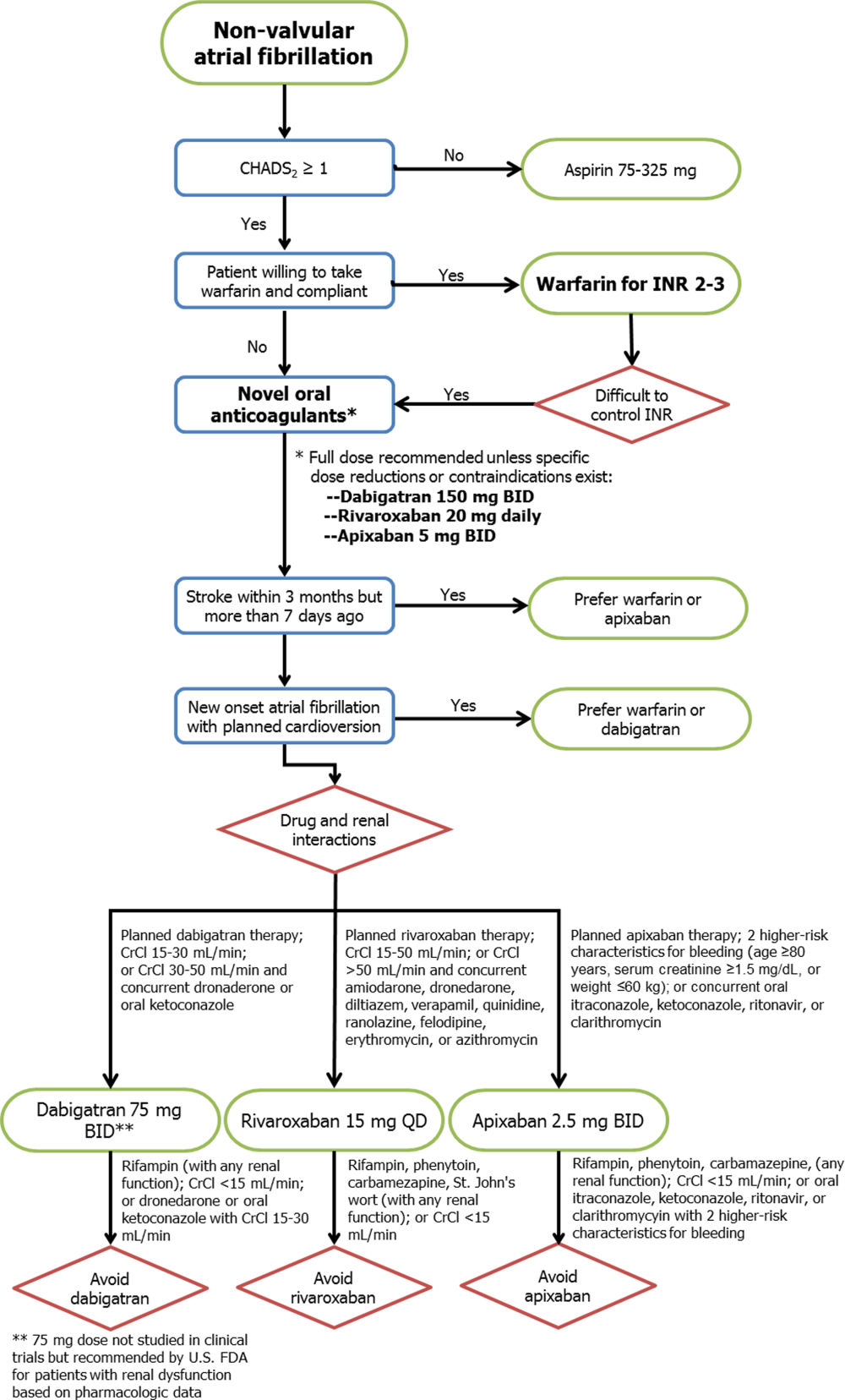

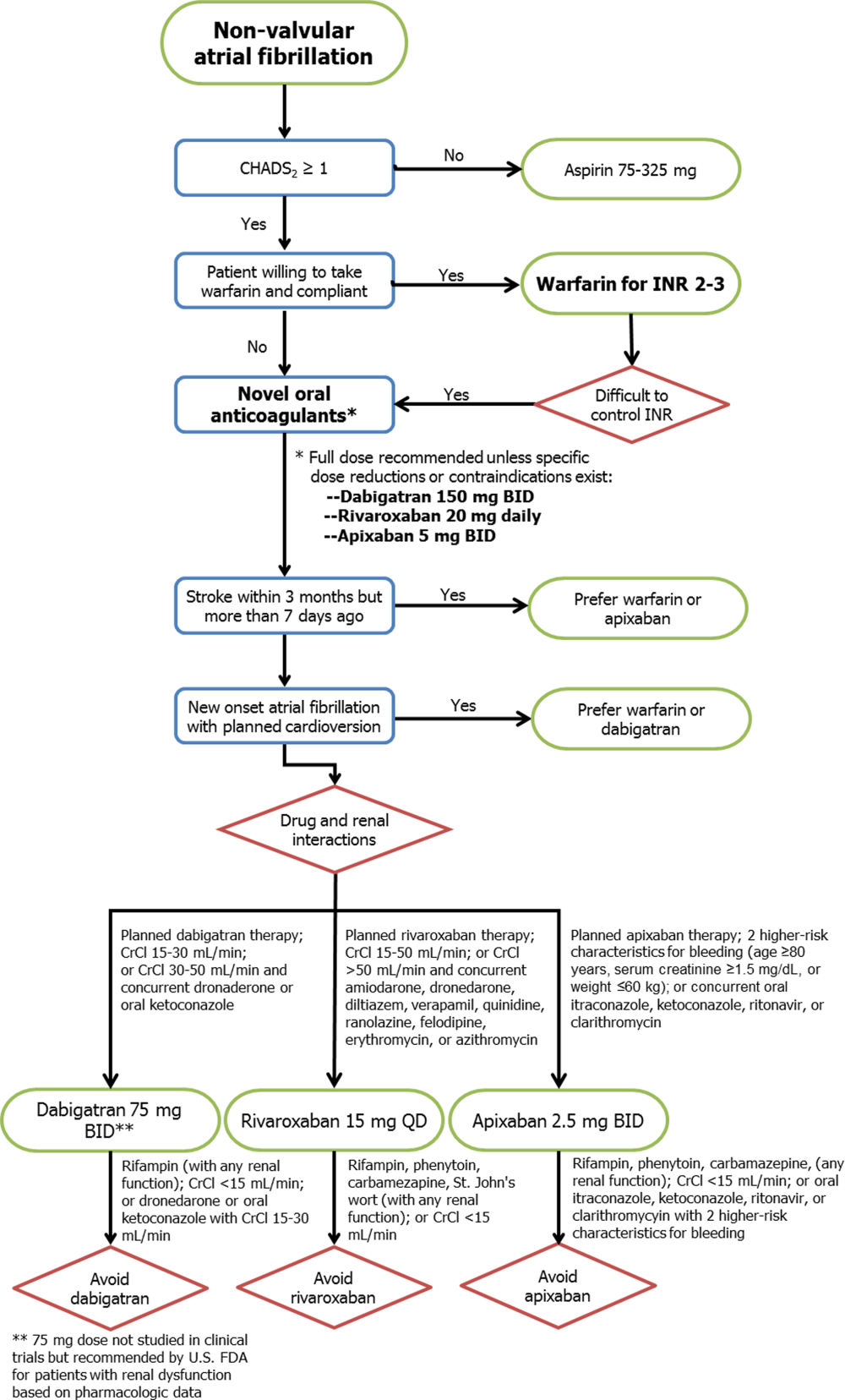

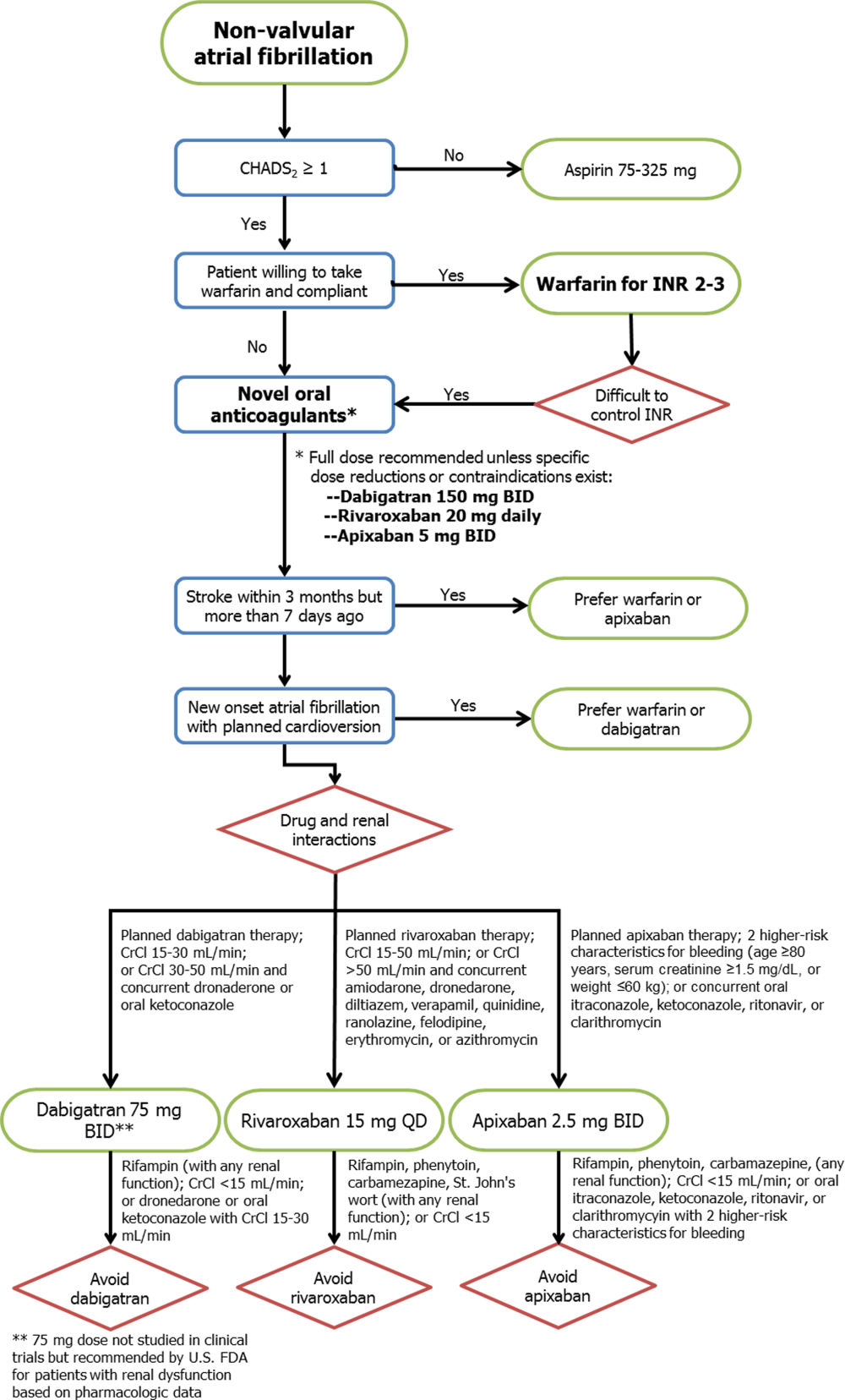

Novel Anticoagulants in Atrial Fibrillation

Approximately 2.3 million people in the United States and 4.5 million people in Europe have atrial fibrillation (AF), with an increase in prevalence with age to 8% among patients aged 80 years and older.[1] The most feared and potentially preventable complications of AF are stroke or systemic thromboembolism, and stroke in particular is increased approximately 5‐fold in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF).[2] For over 50 years, warfarin and similar vitamin K antagonists have been the principal anticoagulants used for preventing stroke in NVAF, with consistent reductions in systemic thromboembolic events when compared with placebo or aspirin.[2, 3] However, because of its narrow therapeutic window and related management difficulties (ie, frequent monitoring of international normalized ratio [INR] levels, dietary and medication restrictions, interindividual variability in dosing), many patients with NVAF do not receive warfarin or are inadequately treated.[4]

In response to the need for antithrombotic agents with better efficacy, patient tolerance, and convenience, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved 3 novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) as alternatives to warfarin for NVAF: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban. In this review, we evaluated the pharmacologic properties and clinical studies of these NOACs, including the continued role of warfarin in many patients requiring systemic anticoagulation, to guide practicing clinicians in providing individualized, patient‐centered care to each of their patients with NVAF.

PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanisms of Action

Whereas warfarin inhibits the formation of multiple vitamin K‐dependent coagulation factors (II, VII, IX, and X),[5] the NOACs are competitive and reversible inhibitors of more distal targets in the coagulation pathway. Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor, whereas rivaroxaban and apixaban directly inhibit factor Xa, ultimately resulting in the inhibition of fibrin formation and thrombosis.

Clinical Pathways and Drug Interactions

Key aspects of the pharmacokinetic profiles of the 3 NOACs are summarized in Table 1. In addition to these baseline properties of each medication, drug interactions play an important role in the effectiveness and potential toxicities of the NOACs. For example, dabigatran is almost exclusively excreted via glomerular filtration, resulting in a terminal half‐life of 12 to 17 hours in normal volunteers and a significantly higher half‐life in moderate and severe renal dysfunction (18 and 27 hours, respectively). In phase II and III trials, there was a 30% decrease in bioavailability when dabigatran was administered with pantoprazole, but no comparable effect was noted when coadministered with histamine receptor blockers like ranitidine.[6] In addition, although dabigatran has no significant interaction with hepatic P450 enzymes, its prodrug is excreted by the intestinal efflux transporter p‐glycoprotein. As a result, dabigatran's bioavailability is increased by coadministration with potent p‐glycoprotein inhibitors such as dronedarone, amiodarone, verapamil, diltiazem, or ketoconazole.[6, 7] According to FDA labeling, the only drug contraindicated with concomitant dabigatran administration is rifampin, which reduces serum concentration of dabigatran by 66%.

| Characteristic | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Apixaban |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Target | Factor IIa | Factor Xa | Factor Xa |

| Reversible binding | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Half‐life, h | 1217 | 59 | 815 |

| Time to peak serum concentration, h | 13 | 24 | 34 |

| Protein binding, % | 35 | 9295 | 87 |

| Renal excretion, % | 80 | 66 | 2527 |

| Primary hepatic clearance pathway | Does not interact with CYP enzymes | CYP‐3A4 | CYP‐3A4 |

Unlike dabigatran, the absorption of rivaroxaban has significant variability between individuals, but the bioavailability of the 20‐mg dose increases by 39% and is significantly less variable when taken with food.[8] Phase I studies of rivaroxaban demonstrated that elderly patients had 50% higher serum concentrations when compared with younger patients.[7, 9] Also of note, rivaroxaban has 50% higher bioavailability in Japanese patients as compared with other ethnicities, including Chinese ethnicity, resulting in higher exposure to the drug and potentially explaining higher bleeding rates in Japan when using this drug.[9] The primary mechanisms for metabolism of rivaroxaban are the CYP‐3A4 and CYP‐2C8 pathways in the liver,[10] so other drugs metabolized through these pathways (eg, azole antifungals, protease inhibitors, clarithromycin) may have significant drug‐drug interactions.

Like the other NOACs, apixaban achieves its maximal concentration within 3 to 4 hours,[11] and like rivaroxaban, apixaban is metabolized by the CYP‐3A4 hepatic pathway. However, apixaban does not induce or inhibit hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, so the potential for drug‐drug interactions is considered minimal.[12] Important exceptions include coadministration with ketoconazole or clarithromycin, each of which increases the bioavailability of apixaban up to 1.5‐fold, so a dose reduction to 2.5 mg twice‐daily (BID) is recommended.[11]

CLINICAL STUDIES

Randomized trials evaluating warfarin against placebo or aspirin for NVAF have spanned more than 3 decades, encompassing a variety of study designs, patient populations, and analytic techniques.[2, 3] Despite differences between trials, these studies have provided the framework for contemporary AF management, with consistent reductions in thromboembolic events with systemic anticoagulation, most notably among patients with multiple risk factors for stroke. Current professional guidelines recommend risk assessment of patients with NVAF, using the CHADS2 (1 point each for Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 75 years, Diabetes, and 2 points for prior Stroke) or similar risk scores, to identify patients most likely to benefit from systemic anticoagulation.[1, 13] As a result of this extensive background literature, the 3 NOACs have primarily been evaluated against warfarin (instead of aspirin or placebo) as potential alternatives for reducing thromboembolic events in patients with NVAF. The 1 exception is a prematurely terminated trial of apixaban in warfarin‐ineligible patients with NVAF, in which apixaban reduced stroke or systemic embolism by 55% compared with aspirin after only 1.1 years of follow‐up, with no significant difference in major bleeding.[14]

Pivotal Clinical Trials

The 3 principal trials evaluating the NOACs against warfarin for NVAF are summarized in Table 2. In the Randomized Evaluation of Long‐term anticoagulation Therapy (RE‐LY) trial, dabigatran was compared with warfarin in 18,113 patients recruited from 951 clinical centers in 44 countries using a noninferiority study design.[15] Two different doses of dabigatran were studied, but only the 150‐mg BID dose was approved by the FDA. As a result, only the findings from the clinically approved 150‐mg dose are summarized in this review. Although RE‐LY was considered a semiblinded randomized trial, patients enrolled in the warfarin control arm underwent regular INR surveillance by their treating physicians, leaving the trial open to potential reporting biases. The authors tried to minimize bias by providing a standardized protocol for INR management, and by assigning 2 independent investigators blinded to the treatment assignments to adjudicate each event.

| Characteristic | RE‐LY | ROCKET‐AF | ARISTOTLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Drug | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Apixaban |

| Dosing | 150 mg BID (110 mg BID also tested) | 20 mg daily (15 mg for creatinine clearance 3049 mL/min) | 5 mg BID (2.5 mg for patients at higher risk of bleeding)a |

| Total population | 18,113 | 14,264 | 18,201 |

| Randomization | Semiblinded | Double blinded | Double blinded |

| Primary analytic approach | Noninferiority, intention‐to‐treat | Noninferiority, both intention‐to‐treat and on‐treatment | Noninferiority, intention‐to‐treat |

| Primary efficacy end point | Stroke or systemic embolism | Stroke or systemic embolism | Stroke or systemic embolism |

| Primary safety end point | Major bleeding | Major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding | Major bleeding |

| Key inclusion criteria | |||

| Documented atrial fibrillation | At screening or within 6 months | Within 30 days prior to randomization and within past year | At least 2 episodes recorded 2 weeks apart in past year |

| Eligible CHADS[2] scores | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Selected exclusion criteria | |||

| Valvular heart disease | Any hemodynamically relevant or prosthetic valve | Severe mitral stenosis or any mechanical prosthetic valve | Moderate or severe mitral stenosis, or any mechanical prosthetic valve |

| Stroke | Severe 6 months or mild/moderate 14 days | Severe 3 months, any stroke 14 days, TIA 3 days | Stroke 7 days |

| Bleeding | Surgery 30 days, gastrointestinal bleed 12 months, any prior intracranial bleed, severe hypertension | Surgery 30 days, gastrointestinal bleed 6 months, active internal bleeding, any prior intracranial bleed, chronic dual antiplatelet therapy, severe hypertension, platelets 90,000/L | Any prior intracranial bleed, chronic dual antiplatelet therapy, severe hypertension |

| Renal | Creatinine clearance <30 mL/min | Creatinine clearance <30 mL/min | Creatinine clearance <25 mL/min |

The Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET‐AF) study involved 14,264 patients from 1178 participating sites in 45 countries.[16] Again, a noninferiority design was used to evaluate 20‐mg daily rivaroxaban against warfarin, but the 2 arms were compared in double‐blinded, double‐dummy fashion (thus eliminating the reporting bias related to the warfarin control arm in RE‐LY). In addition, whereas RE‐LY randomized patients to fixed doses of dabigatran within their respective treatment arms, ROCKET‐AF required a lower dose of rivaroxaban (15 mg daily) for patients with moderately reduced creatinine clearance (3049 mL/min). Also of note, ROCKET‐AF reported both intention‐to‐treat and on‐treatment analyses, with outcomes listed as number of events per 100 patient‐years (instead of percent per year). To facilitate comparisons between trials, only the intention‐to‐treat data are reported in this review.

Like ROCKET‐AF, the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) study randomized patients using a double‐blind, double‐dummy, noninferiority design to therapy with apixaban 5 mg BID versus warfarin, ultimately enrolling 18,201 patients at 1034 clinical sites in 39 countries.[17] ARISTOTLE also provided a lower dose of apixaban (2.5 mg BID) for patients at higher risk of bleeding, defined by the authors as patients with 2 of the following characteristics: age 80 years and older, weight 60 kg, or serum creatinine 1.5 mg/dL. However, <5% of all patients in ARISTOTLE met these criteria and received the lower dose of apixaban.

Patient Populations and Study End Points

All 3 trials used relatively similar criteria for enrolling and following patients, with individual thromboembolic risk calculated using the CHADS2 definition, where higher scores are associated with incrementally higher risk of stroke.[18] However, ROCKET‐AF required a minimum CHADS2 score of 2 and permitted patients with lower left ventricular ejection fractions (35%), thus enrolling a higher‐risk patient population than RE‐LY and ARISTOTLE (where ejection fraction 40% was considered a risk factor for thromboembolism). As a result, more patients in ROCKET‐AF had prior stroke or systemic embolism than the other 2 trials (55% vs 20% in RE‐LY and 19% in ARISTOTLE) and more patients had significant heart failure (63%,vs 32% in RE‐LY and 36% in ARISTOTLE). These differences in enrollment ultimately translated into a higher overall risk profile in ROCKET‐AF (Table 3), which may have impacted some of the study results. In addition, patients requiring dual antiplatelet therapy (ie, clopidogrel and aspirin) were permitted in RE‐LY (5% of the final randomized population) but were excluded from the other 2 trials. The primary outcome for all 3 trials was the composite of stroke or systemic embolism, and the primary safety end point was major bleeding (RE‐LY and ARISTOTLE), or combined major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events (ROCKET‐AF).

| Characteristic | RE‐LY | ROCKET‐AF | ARISTOTLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y | 72 | 73 | 70 |

| Male sex, % | 63 | 60 | 65 |

| Type of atrial fibrillation, % | |||

| Paroxysmal | 33 | 18 | 15 |

| Persistent/permanent | 67 | 82 | 85 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||

| Hypertension | 79 | 90 | 87 |

| Previous stroke or systemic embolism | 20 | 55 | 19 |

| Diabetes | 23 | 40 | 25 |

| Congestive heart failure | 32 | 63 | 36 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 17 | 17 | 15 |

| CHADS2 score, % | |||

| 01 | 32 | 0 | 34 |

| 2 | 35 | 13 | 36 |

| 3 | 33 | 87 | 30 |

| Medications, % | |||

| ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker | 67 | 55 | 71 |

| ‐Blockers | 64 | 65 | 64 |

| Digoxin | 29 | 39 | 32 |

| Amiodarone | 11 | Not reported | 11 |

| Aspirin | 39 | 36 | 31 |

| Aspirin and clopidogrel | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Prior long‐term warfarin or other vitamin K antagonist | 50 | 62 | 57 |

| Creatinine clearance, % | |||

| >80 mL/min | 32 | 32 | 41 |

| >5080 mL/min | 48 | 47 | 42 |

| >3050 mL/min | 20 | 21 | 15 |

| <30 mL/min | <1 | None reported | 2 |

| Mean time in therapeutic range among warfarin‐treated patients, % | 64 | 55 | 66 |

Clinical Outcomes

As illustrated in Table 4, the dabigatran 150‐mg BID dose was both noninferior and superior to warfarin for reducing the composite primary end point. Patients randomized to this arm of the RE‐LY study experienced fewer ischemic strokes, fewer hemorrhagic strokes, and a strong trend toward lower all‐cause mortality despite higher rates of myocardial infarction. There was no difference in overall major bleeding, although a significant reduction in intracranial hemorrhage was offset by a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Clinical Outcome | RE‐LY | ROCKET‐AF | ARISTOTLE | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran, 150 mg BID, %/y | Warfarin, %/y | Hazard Ratio | P Valuea | Rivaroxaban, 20 mg QD, No./100 Patient‐Years | Warfarin, No./100 Patient‐Years | Hazard Ratio | P Valuea | Apixaban 5 mg BID, %/y | Warfarin, %/yr | Hazard Ratio | P Valuea | |

| ||||||||||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | 1.11 | 1.69 | 0.66 | <0.001 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.88 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 1.60 | 0.79 | 0.01 |

| Any stroke | 1.01 | 1.57 | 0.64 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 1.96 | 0.85 | 0.092 | 1.19 | 1.51 | 0.79 | 0.01 |

| Ischemic | 0.92 | 1.20 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 1.34 | 1.42 | 0.94 | 0.581 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.92 | 0.42 |

| Hemorrhagic | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.59 | 0.024 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.38 | 0.048 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 0.81 | 0.121 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.37 |

| All‐cause mortality | 3.64 | 4.13 | 0.88 | 0.051 | 1.87 | 2.21 | 0.85 | 0.073 | 3.52 | 3.94 | 0.89 | 0.047 |

| Major bleeds | 3.11 | 3.36 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 1.04 | 0.58 | 2.13 | 3.09 | 0.69 | <0.001 |

| Intracranial | 0.30 | 0.74 | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.51 | 1.02 | 1.50 | <0.001 | 3.15b | 2.16b | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.37 | |

In the intention‐to‐treat analyses from ROCKET‐AF, rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin for reducing the primary end point, and there was a significant reduction in hemorrhagic stroke by rivaroxaban. Again, a strong trend toward lower mortality was seen, and like RE‐LY, an equivocal bleeding end point was largely driven by the combination of lower intracranial hemorrhage but higher gastrointestinal bleeding rates. Of note, the on‐treatment analysis from ROCKET‐AF demonstrated both noninferiority and superiority to warfarin, and there was no signal for higher rates of myocardial infarction as seen in RE‐LY.

In ARISTOTLE, apixaban was both noninferior and superior to warfarin, with stroke reduction largely driven by lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage. Unlike the prior studies of dabigatran and rivaroxaban, ARISTOTLE demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in all‐cause mortality and a significant reduction in major bleeding with apixaban therapy, with no increase in gastrointestinal bleeding.

INR Control

In prior randomized trials and observational registries of patients with AF, INR control has been highly variable, and better clinical outcomes were observed among patients consistently achieving INR levels between 2 and 3.[3, 19] For all 3 randomized trials of the NOACs summarized in this review, the warfarin control arms were analyzed using the Rosendaal method of evaluating total time in therapeutic range (TTR), reflecting the percent of time the patient had an INR between 2 and 3.[20] Overall, the mean TTR was 64% to 66% in the RE‐LY and ARISTOTLE trials, but only 55% in ROCKET‐AF. This has led to considerable criticism of the ROCKET‐AF trial, given concerns for a less robust comparator arm for rivaroxaban (and thus the potential for inflated efficacy of rivaroxaban over warfarin).[21, 22] However, these TTR levels are similar to those reported in prior studies of warfarin and may better represent real‐world INR management across multiple countries.[23]