User login

HM14 Report: Review of New Guidelines for Pediatric UTI

Presenter: Maria Finnell, MD

Summation: Dr. Finnell reviewed in detail the recommendations and controversies surrounding the revised 2011 guidelines. The thrust was on more refined diagnostic criteria and rigorous review of diagnostic options (ultrasound, VCUG) and therapeutic options (length of treatment, IV vs oral antibiotics, and prophylactic therapy).

Key Takeaways

- The diagnosis of a UTI is based on an abnormal urinalysis and a positive urine culture, now defined as >50,000 CFU/ml. A bag-colleted urine is not very effective in truly diagnosing a UTI (due to excessive false positives).

- Oral treatment is as effective as IV therapy.

- Duration of 7-14 days is recommended. There is not definitive evidence to support a more specific length at this time.

- A VCUG is not recommended after a 1st febrile UTI for children 2 months- 2 years of age.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis does increase antibiotic resistance and is not clearly helpful for reflux grades 1-2. For reflux grades 3-5, it may still be effective.

- Educating parents of children who have had a 1st febrile UTI to arrange for early evaluation of a possible secondary febrile UTIs is key in catching UTIs early.

Dr. Harlan is a pediatric hospitalist, medical director with IPC The Hospitalist Company, and member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Maria Finnell, MD

Summation: Dr. Finnell reviewed in detail the recommendations and controversies surrounding the revised 2011 guidelines. The thrust was on more refined diagnostic criteria and rigorous review of diagnostic options (ultrasound, VCUG) and therapeutic options (length of treatment, IV vs oral antibiotics, and prophylactic therapy).

Key Takeaways

- The diagnosis of a UTI is based on an abnormal urinalysis and a positive urine culture, now defined as >50,000 CFU/ml. A bag-colleted urine is not very effective in truly diagnosing a UTI (due to excessive false positives).

- Oral treatment is as effective as IV therapy.

- Duration of 7-14 days is recommended. There is not definitive evidence to support a more specific length at this time.

- A VCUG is not recommended after a 1st febrile UTI for children 2 months- 2 years of age.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis does increase antibiotic resistance and is not clearly helpful for reflux grades 1-2. For reflux grades 3-5, it may still be effective.

- Educating parents of children who have had a 1st febrile UTI to arrange for early evaluation of a possible secondary febrile UTIs is key in catching UTIs early.

Dr. Harlan is a pediatric hospitalist, medical director with IPC The Hospitalist Company, and member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Maria Finnell, MD

Summation: Dr. Finnell reviewed in detail the recommendations and controversies surrounding the revised 2011 guidelines. The thrust was on more refined diagnostic criteria and rigorous review of diagnostic options (ultrasound, VCUG) and therapeutic options (length of treatment, IV vs oral antibiotics, and prophylactic therapy).

Key Takeaways

- The diagnosis of a UTI is based on an abnormal urinalysis and a positive urine culture, now defined as >50,000 CFU/ml. A bag-colleted urine is not very effective in truly diagnosing a UTI (due to excessive false positives).

- Oral treatment is as effective as IV therapy.

- Duration of 7-14 days is recommended. There is not definitive evidence to support a more specific length at this time.

- A VCUG is not recommended after a 1st febrile UTI for children 2 months- 2 years of age.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis does increase antibiotic resistance and is not clearly helpful for reflux grades 1-2. For reflux grades 3-5, it may still be effective.

- Educating parents of children who have had a 1st febrile UTI to arrange for early evaluation of a possible secondary febrile UTIs is key in catching UTIs early.

Dr. Harlan is a pediatric hospitalist, medical director with IPC The Hospitalist Company, and member of Team Hospitalist.

HM14 Special Report: Rationale and Review of the New Guidelines for First Febrile UTI

Presenter: Maria Finnell, M.D., a leading member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection

Summary: Dr. Finnell summarized the recent changes in diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections (UTIs). The 2011 publication of “Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Children 2 to 24 Months” was an update of the 1999 technical report of UTI management. Dr. Finnell reviewed the difference between evidence based and eminence based recommendations. She stated the term “recommendations” was changed to “key action statements” in a new explicit reporting format. Aggregate quality of the evidence is presented in the report in an effort to keep statements transparent.

The process of updating the new guideline was based on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force approach using a stepwise process. For the revised UTI recommendations the steps were narrowed to:

- Risk of having infection

- Making a diagnosis

- Treatment of UTI

- Identification and Evaluation for high risk conditions

Patient population for this guideline includes initial UTI in child age 2 months to 2 years of age. Patients with neurological conditions or recurrent UTI or renal damage are excluded. Dr. Finnell reviewed action statements for the revised guidelines. A summary of some of these statements:

- If antibiotics are going to be administered, a urine specimen should be collected by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration (SPA).

- Assessment of UTI risk should be performed in a febrile child with no source of infection. The guideline cites specific data for risk. If the likelihood is low then it is reasonable to follow the child clinically without a urine specimen. If the likelihood of a UTI is high then a urine specimen should be obtained.

- To establish the diagnosis of UTI, clinicians should require both urinalysis results that suggest infection and the presence of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) per mL of a uropathogen cultured from a urine specimen obtained through catheterization or SPA.

- Oral and parenteral routes are equally efficacious.

- The clinician should choose 7-14 days as duration of treatment.

- Febrile infants with UTIs should undergo renal and bladder ultrasonography.

- VCUG should not be routinely performed after first UTI if ultrasound is normal.

Dr. Finnell also discussed controversy of not performing a VCUG after a first febrile UTI, as was recommended in the 1999 technical report. She summarized that about 100 children would need to undergo one UTI in the first year. She also reviewed limitations of any guidelines. New studies will assist in monitoring population changes with the revised guideline.

Key Takeaways:

- Understand the evidence and limitations used for all clinical guidelines that you use in practice.

- The updated 2011 guideline for evaluation and management of first febrile UTIs uses risk stratification as an initial approach.

- A major change in the updated 2011 guideline for evaluation and management of first febrile UTIs is that a VCUG is not required for initial evaluation.

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

Reference:

Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Children 2 to 24 Months. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3).

Presenter: Maria Finnell, M.D., a leading member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection

Summary: Dr. Finnell summarized the recent changes in diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections (UTIs). The 2011 publication of “Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Children 2 to 24 Months” was an update of the 1999 technical report of UTI management. Dr. Finnell reviewed the difference between evidence based and eminence based recommendations. She stated the term “recommendations” was changed to “key action statements” in a new explicit reporting format. Aggregate quality of the evidence is presented in the report in an effort to keep statements transparent.

The process of updating the new guideline was based on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force approach using a stepwise process. For the revised UTI recommendations the steps were narrowed to:

- Risk of having infection

- Making a diagnosis

- Treatment of UTI

- Identification and Evaluation for high risk conditions

Patient population for this guideline includes initial UTI in child age 2 months to 2 years of age. Patients with neurological conditions or recurrent UTI or renal damage are excluded. Dr. Finnell reviewed action statements for the revised guidelines. A summary of some of these statements:

- If antibiotics are going to be administered, a urine specimen should be collected by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration (SPA).

- Assessment of UTI risk should be performed in a febrile child with no source of infection. The guideline cites specific data for risk. If the likelihood is low then it is reasonable to follow the child clinically without a urine specimen. If the likelihood of a UTI is high then a urine specimen should be obtained.

- To establish the diagnosis of UTI, clinicians should require both urinalysis results that suggest infection and the presence of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) per mL of a uropathogen cultured from a urine specimen obtained through catheterization or SPA.

- Oral and parenteral routes are equally efficacious.

- The clinician should choose 7-14 days as duration of treatment.

- Febrile infants with UTIs should undergo renal and bladder ultrasonography.

- VCUG should not be routinely performed after first UTI if ultrasound is normal.

Dr. Finnell also discussed controversy of not performing a VCUG after a first febrile UTI, as was recommended in the 1999 technical report. She summarized that about 100 children would need to undergo one UTI in the first year. She also reviewed limitations of any guidelines. New studies will assist in monitoring population changes with the revised guideline.

Key Takeaways:

- Understand the evidence and limitations used for all clinical guidelines that you use in practice.

- The updated 2011 guideline for evaluation and management of first febrile UTIs uses risk stratification as an initial approach.

- A major change in the updated 2011 guideline for evaluation and management of first febrile UTIs is that a VCUG is not required for initial evaluation.

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

Reference:

Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Children 2 to 24 Months. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3).

Presenter: Maria Finnell, M.D., a leading member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection

Summary: Dr. Finnell summarized the recent changes in diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections (UTIs). The 2011 publication of “Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Children 2 to 24 Months” was an update of the 1999 technical report of UTI management. Dr. Finnell reviewed the difference between evidence based and eminence based recommendations. She stated the term “recommendations” was changed to “key action statements” in a new explicit reporting format. Aggregate quality of the evidence is presented in the report in an effort to keep statements transparent.

The process of updating the new guideline was based on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force approach using a stepwise process. For the revised UTI recommendations the steps were narrowed to:

- Risk of having infection

- Making a diagnosis

- Treatment of UTI

- Identification and Evaluation for high risk conditions

Patient population for this guideline includes initial UTI in child age 2 months to 2 years of age. Patients with neurological conditions or recurrent UTI or renal damage are excluded. Dr. Finnell reviewed action statements for the revised guidelines. A summary of some of these statements:

- If antibiotics are going to be administered, a urine specimen should be collected by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration (SPA).

- Assessment of UTI risk should be performed in a febrile child with no source of infection. The guideline cites specific data for risk. If the likelihood is low then it is reasonable to follow the child clinically without a urine specimen. If the likelihood of a UTI is high then a urine specimen should be obtained.

- To establish the diagnosis of UTI, clinicians should require both urinalysis results that suggest infection and the presence of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) per mL of a uropathogen cultured from a urine specimen obtained through catheterization or SPA.

- Oral and parenteral routes are equally efficacious.

- The clinician should choose 7-14 days as duration of treatment.

- Febrile infants with UTIs should undergo renal and bladder ultrasonography.

- VCUG should not be routinely performed after first UTI if ultrasound is normal.

Dr. Finnell also discussed controversy of not performing a VCUG after a first febrile UTI, as was recommended in the 1999 technical report. She summarized that about 100 children would need to undergo one UTI in the first year. She also reviewed limitations of any guidelines. New studies will assist in monitoring population changes with the revised guideline.

Key Takeaways:

- Understand the evidence and limitations used for all clinical guidelines that you use in practice.

- The updated 2011 guideline for evaluation and management of first febrile UTIs uses risk stratification as an initial approach.

- A major change in the updated 2011 guideline for evaluation and management of first febrile UTIs is that a VCUG is not required for initial evaluation.

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

Reference:

Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of the Initial UTI in Febrile Infants and Children 2 to 24 Months. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3).

HM14 Special Report: HFNC in Bronchiolitis

Session: HFNC in Bronchiolitis: Best Thing Since Sliced Bread?

Presenter: Shawn Ralston, MD

Summation: Shawn Ralston, known as “Dr. Bronchiolitis” for her work on the AAP Bronchiolitis Practice Guideline, described the limited data on the use of High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) in bronchiolitis. For HFNC to be effective it must have a flow above the patient’s minute ventilation, or at least 2 LPM for the infant. Physiologic studies show that HFNC improve work of breathing by washing out dead space and providing “mini-CPAP.” Increasing flow increases the CPAP effect up to about 6 LPM with less effect at higher rates. HFNC can achieve equivalent CPAP levels of about 3-4, with higher flows increasing pneumothorax risk. Studies of HFNC in bronchiolitis have been observational and retrospective showing trends towards decrease risk of intubation and that HFNC can be safely used outside an ICU setting. There are no clear data or guidelines to indicate which patients with bronchiolitis will benefit from HFNC.

Key Points:

- Need cannula at least 50% diameter of nares;

- Mouth should be closed—can use pacifier;

- Need flow rate above estimated minute ventilation;

- Higher flow, increase pneumothorax risk;

- Need high quality studies to better understand the role of HFNC in bronchiolitis.

David Pressel is a Pediatric Hospitalist and Inpatient Medical Director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, DE and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Session: HFNC in Bronchiolitis: Best Thing Since Sliced Bread?

Presenter: Shawn Ralston, MD

Summation: Shawn Ralston, known as “Dr. Bronchiolitis” for her work on the AAP Bronchiolitis Practice Guideline, described the limited data on the use of High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) in bronchiolitis. For HFNC to be effective it must have a flow above the patient’s minute ventilation, or at least 2 LPM for the infant. Physiologic studies show that HFNC improve work of breathing by washing out dead space and providing “mini-CPAP.” Increasing flow increases the CPAP effect up to about 6 LPM with less effect at higher rates. HFNC can achieve equivalent CPAP levels of about 3-4, with higher flows increasing pneumothorax risk. Studies of HFNC in bronchiolitis have been observational and retrospective showing trends towards decrease risk of intubation and that HFNC can be safely used outside an ICU setting. There are no clear data or guidelines to indicate which patients with bronchiolitis will benefit from HFNC.

Key Points:

- Need cannula at least 50% diameter of nares;

- Mouth should be closed—can use pacifier;

- Need flow rate above estimated minute ventilation;

- Higher flow, increase pneumothorax risk;

- Need high quality studies to better understand the role of HFNC in bronchiolitis.

David Pressel is a Pediatric Hospitalist and Inpatient Medical Director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, DE and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Session: HFNC in Bronchiolitis: Best Thing Since Sliced Bread?

Presenter: Shawn Ralston, MD

Summation: Shawn Ralston, known as “Dr. Bronchiolitis” for her work on the AAP Bronchiolitis Practice Guideline, described the limited data on the use of High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) in bronchiolitis. For HFNC to be effective it must have a flow above the patient’s minute ventilation, or at least 2 LPM for the infant. Physiologic studies show that HFNC improve work of breathing by washing out dead space and providing “mini-CPAP.” Increasing flow increases the CPAP effect up to about 6 LPM with less effect at higher rates. HFNC can achieve equivalent CPAP levels of about 3-4, with higher flows increasing pneumothorax risk. Studies of HFNC in bronchiolitis have been observational and retrospective showing trends towards decrease risk of intubation and that HFNC can be safely used outside an ICU setting. There are no clear data or guidelines to indicate which patients with bronchiolitis will benefit from HFNC.

Key Points:

- Need cannula at least 50% diameter of nares;

- Mouth should be closed—can use pacifier;

- Need flow rate above estimated minute ventilation;

- Higher flow, increase pneumothorax risk;

- Need high quality studies to better understand the role of HFNC in bronchiolitis.

David Pressel is a Pediatric Hospitalist and Inpatient Medical Director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, DE and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Deaf and self-signing

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

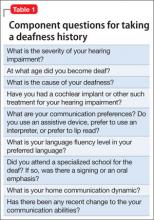

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

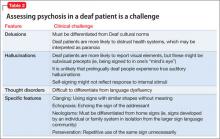

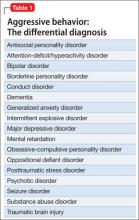

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

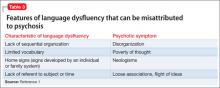

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.

Sinus surgery: new rigor in research

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Research-minded otolaryngologists have gotten serious about conducting high-quality, patient-centered outcomes studies of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis, which more than 250,000 Americans undergo each year. And the results are eye opening.

Mounting evidence documents that endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) in properly selected patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) results in markedly improved quality of life, functional status, and reduced use of medications, compared with medical management, Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

These studies utilize validated measures of patient-centered quality of life and symptoms. They are nothing like the lightweight, less-than-persuasive ESS research published in the 1990s, which reported glowing ‘success’ rates of 80%-97% in single-institution retrospective studies using variable inclusion criteria and often-sketchy definitions of success.

"Those data are not acceptable, but that’s what we had. This was before evidence-based medicine with an emphasis on rigorously designed studies took hold," explained Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology – head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

Current research emphasizes the use of modern, validated patient-centered quality of life tools and symptom scores because CRS is a symptom-based diagnosis and it is symptom severity that drives patients to seek treatment. Also, objective measures, such as the Lund-Mackay CT staging system, fail to capture the full experience of disease burden. Nor do objective measures necessarily correlate with patient symptoms, according to the otolaryngologist.

A low point in the field of sinus surgery, in Dr. Kingdom’s view, was the 2006 Cochrane systematic review which concluded ESS "has not been demonstrated to confer additional benefit to that obtained by medical therapy" (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD004458).

"This review was a disservice," he asserted.

The review was based entirely on three older randomized trials, which not only did not use current treatment paradigms but also did not study the key research question, which Dr. Kingdom believes is this: What’s the comparative effectiveness of ESS vs. continued medical therapy in patients who’ve failed initial medical therapy?

He offered as an example of the contemporary approach to comparative outcomes research in the field of ESS a recent multicenter prospective study led by otolaryngologists at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. It involved 1 year of prospective follow-up of patients with CRS who had failed initial medical therapy, at which point they elected to undergo ESS or further medical management.

The 65 patients who opted for ESS and the 50 whose chose more medical management were comparable in terms of baseline CRS severity and comorbidities. Both groups showed durable improvement at 12 months, compared with baseline. But ESS was the clear winner, with a mean 71% improvement in the validated Chronic Sinusitis Survey total score, compared with a 46% improvement in the medically managed group. Moreover, during the year of follow-up 17 patients switched over from medical management to ESS and they, too, showed significantly greater improvement than those who remained on medical management (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:236-41).

An earlier interim report featuring 6 months of followup showed the surgical group experienced roughly twofold greater improvement, compared with the medical cohort in endpoints including number of days on oral antibiotics or oral corticosteroids and missed days of work or school (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1:235-41).

Cost-effectiveness studies by various research groups are in the pipeline. The early indication is that the data will show an economic advantage for ESS over medical therapy in patients with recalcitrant disease, according to Dr. Kingdom.

The next research frontier in surgical outcomes in CRS is identification of cellular and molecular markers of disease activity and their genetic underpinnings, which it’s hoped can be used to select the best candidates for ESS, he added.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Research-minded otolaryngologists have gotten serious about conducting high-quality, patient-centered outcomes studies of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis, which more than 250,000 Americans undergo each year. And the results are eye opening.

Mounting evidence documents that endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) in properly selected patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) results in markedly improved quality of life, functional status, and reduced use of medications, compared with medical management, Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

These studies utilize validated measures of patient-centered quality of life and symptoms. They are nothing like the lightweight, less-than-persuasive ESS research published in the 1990s, which reported glowing ‘success’ rates of 80%-97% in single-institution retrospective studies using variable inclusion criteria and often-sketchy definitions of success.

"Those data are not acceptable, but that’s what we had. This was before evidence-based medicine with an emphasis on rigorously designed studies took hold," explained Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology – head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

Current research emphasizes the use of modern, validated patient-centered quality of life tools and symptom scores because CRS is a symptom-based diagnosis and it is symptom severity that drives patients to seek treatment. Also, objective measures, such as the Lund-Mackay CT staging system, fail to capture the full experience of disease burden. Nor do objective measures necessarily correlate with patient symptoms, according to the otolaryngologist.

A low point in the field of sinus surgery, in Dr. Kingdom’s view, was the 2006 Cochrane systematic review which concluded ESS "has not been demonstrated to confer additional benefit to that obtained by medical therapy" (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD004458).

"This review was a disservice," he asserted.

The review was based entirely on three older randomized trials, which not only did not use current treatment paradigms but also did not study the key research question, which Dr. Kingdom believes is this: What’s the comparative effectiveness of ESS vs. continued medical therapy in patients who’ve failed initial medical therapy?

He offered as an example of the contemporary approach to comparative outcomes research in the field of ESS a recent multicenter prospective study led by otolaryngologists at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. It involved 1 year of prospective follow-up of patients with CRS who had failed initial medical therapy, at which point they elected to undergo ESS or further medical management.

The 65 patients who opted for ESS and the 50 whose chose more medical management were comparable in terms of baseline CRS severity and comorbidities. Both groups showed durable improvement at 12 months, compared with baseline. But ESS was the clear winner, with a mean 71% improvement in the validated Chronic Sinusitis Survey total score, compared with a 46% improvement in the medically managed group. Moreover, during the year of follow-up 17 patients switched over from medical management to ESS and they, too, showed significantly greater improvement than those who remained on medical management (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:236-41).