User login

Arthroscopic Treatment of Femoroacetabular Impingement

Stigma is a family affair

Each year, 60 million Americans experience mental illness. Across the United States, each year, regardless of race, age, religion, or economic status, mental illness affects the lives of one in four adults and one in 10 children. This means that someone in every family has mental illness.

Most of our patients probably don’t tell anyone that they or one of their family members has mental illness They probably are doing what most of us do: Pretend it’s not there. Why? Because the stigma of mental illness is pervasive and destructive. What can we do to decrease the stigma?

The word stigma is derived from Greek and means "to mark the body." The bearer of the mark, or the stigma, is avoided and shunned. This practice has continued through the ages. In medieval times, if a person had a mental illness, he or she was thought to be possessed by demons and viewed as weak. Today, people with mental illness are viewed as menacing, deviant, unpredictable, incompetent, or even dangerous. It is entirely reasonable then, that we would want to avoid the stigma of mental illness. However, this prejudice against mental illness must be challenged.

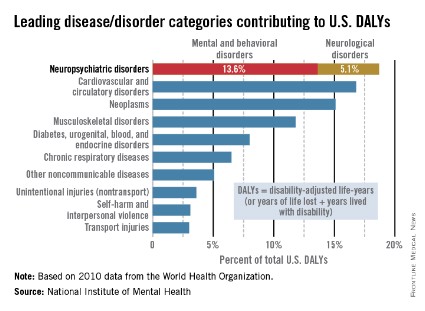

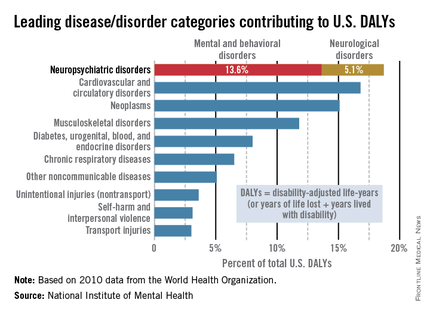

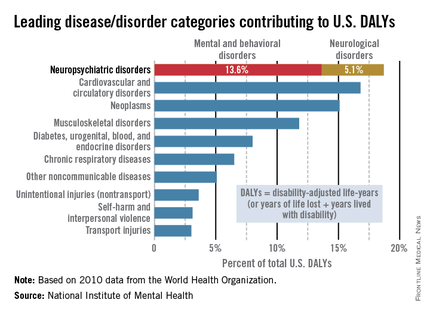

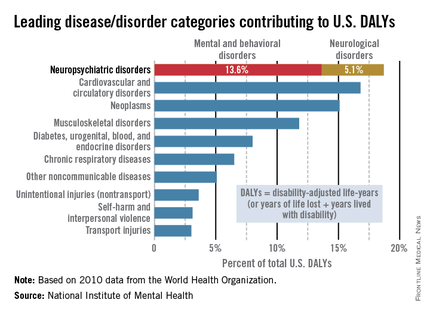

Mental illness accounts for increased morbidity and mortality as well as lifetime disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States, followed by cardiovascular and circulatory diseases, and neoplasms. The neuropsychiatric disorders category, which includes mental and behavioral disorders, accounts for 13.6% of total U.S. disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Neurological disorders account for 5.1% of total U.S. DALYs.

Impact on the family

Not only does stigma affect individuals, it affects family members as well. Family members suffer from SBA, or stigma by association (Brit. J. Psych. 2002;181:494-8), also known as courtesy stigma (Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593-602). Families share stigma because families share a genetic heritage. Families share stigma by assuming responsibility for their family members’ behaviors. Families share stigma because they are seen as having common motivations (J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:224-41).

SBA causes psychological distress in family members (Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58:73-80; J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1987;175:4-11; Br. J. Psychiatry 2002;181:494-8; and Schizophr. Bull. 1998;24:115-126).

Psychological complaints, such as brooding, inner unrest, and irritability, and physical complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, and neck and shoulder pain, have been attributed to the psychological distress of SBA. Family members may avoid social interactions and conceal their relationship to the family member who is mentally ill (Acad. Psychiatry 2008;32:87-91). They might psychologically distance themselves from a relative with mental illness.

SBA varies by disease type, family role, and age. The greatest SBA is associated with drug dependence. These family members are blamed for the illness, held responsible for relapse, and viewed as incompetent. In the study of Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., (J. Fam. Psychol. 2006;20:239-46), family members report feelings of "contamination" and shame. Severe depression or panic and phobias engender less stigma. More educated people are less likely to report feelings of stigma.

According to Dr. Corrigan, SBA varies by family role: Parents are blamed for causing the child’s mental illness, siblings are blamed for not ensuring that relatives with mental illness adhere to treatment plans, and children are fearful of being "contaminated" with the mental illness of their parent. The closer the relationship, the less the stigma is perceived as defining the person. Family closeness can reduce stigma (The Gerontologist 2012;52:89-97). Regarding age, a British study showed that the highest stigma is reported in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (Br. J. Psychiatry 2000;177:4-7).

Psychiatry as a profession has not helped diminish stigma. It is not uncommon to hear psychiatrists assign blame to parents or spouses. Psychiatrists often believe that the family has a role in the patient’s illness. How many spouses have been told they are "codependent" with the implication that they have somehow "caused the illness"? What can we do diminish stigma?

Fighting stigma

Fighting stigma means confronting stigma (Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000;6:65-72). Most efforts worldwide have begun with the idea of educating people about mental illness. These efforts, focused on promoting mental illness as a biological illness, have had limited success and in some situations actually increased stigma (Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012; 125:440-52). The answer may lie in targeted education: specific facts for specific groups.

For example, young couples with children become less fearful after education targeted specifically for them (Br. J. Psychiatry 1996;168:191-8). Antistigma campaigns are common throughout the world. The websites of most professional psychiatric organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, provide information about antistigma campaigns. Organizations often partner with mental health charities. Antistigma efforts also focus on publishing articles about stigma as the Lancet did in a series a few years ago (1998;352:1048). It is unclear whether these efforts reduce stigma. Dr. Corrigan suggests that meeting people who have mental illness weakens the tendency to link mental illness and violence (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002;6: 312-34).

The current consensus is that antistigma campaigns should focus on the competence of people with mental illness. In this vein, the Scottish Mental Health Arts & Film Festival highlights the contributions that people with mental illness make to society. The festival, which began in 2007, also sponsors a contest for films that depict people with mental illness in realistic, holistic ways. In 2013, the festival drew 12,000 attendees and sparked 120 newspaper articles that emphasized the fact that people with mental illness are generally active, useful members of society.

Meanwhile, a Canadian antistigma campaign tells the stories of people with mental illness and provides evidence of the competence of these people. The APA’s public service video series, "A Healthy Minds Minute," features celebrities and prominent figures calling for equal access to quality care, and insurance coverage for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

What do we do to reduce stigma? Psychiatrists such as William Beardslee have written about their personal experience of a family member with mental illness. A member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists, Julie Totten, lost her brother to suicide and in response, she developed an organization called Families for Depression Awareness, which is devoted to reducing the stigma of mental illness. For me, it is my personal campaign to say: "One in four means that someone in everyone’s family has mental illness."

What more can we do?

• Speak up when you hear or see stigma.

• Stress the normalcy of people who have mental illness.

• Come out of the closet on behalf of yourself or a family member.

• Include people who acknowledge they suffer from mental illness in antistigma campaigns.

• Discuss the role of stigma with patients and their families. Ask "How has stigma affected you as a family? In what ways has your family helped reduce the stigma of your mental illness?"

• Encourage attendance at support groups, such as NAMI (the National Alliance on Mental Illness).

• Embrace your family member or yourself: Look for personal qualities that wipe out stigma.

• Don’t allow people to stigmatize patients: It might be your family member they are talking about.

• Talk positively about respecting our patients.

• Start a conversation to reduce stigma.

• Remember that fighting stigma means confronting stigma.

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. She is the author of a new book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Each year, 60 million Americans experience mental illness. Across the United States, each year, regardless of race, age, religion, or economic status, mental illness affects the lives of one in four adults and one in 10 children. This means that someone in every family has mental illness.

Most of our patients probably don’t tell anyone that they or one of their family members has mental illness They probably are doing what most of us do: Pretend it’s not there. Why? Because the stigma of mental illness is pervasive and destructive. What can we do to decrease the stigma?

The word stigma is derived from Greek and means "to mark the body." The bearer of the mark, or the stigma, is avoided and shunned. This practice has continued through the ages. In medieval times, if a person had a mental illness, he or she was thought to be possessed by demons and viewed as weak. Today, people with mental illness are viewed as menacing, deviant, unpredictable, incompetent, or even dangerous. It is entirely reasonable then, that we would want to avoid the stigma of mental illness. However, this prejudice against mental illness must be challenged.

Mental illness accounts for increased morbidity and mortality as well as lifetime disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States, followed by cardiovascular and circulatory diseases, and neoplasms. The neuropsychiatric disorders category, which includes mental and behavioral disorders, accounts for 13.6% of total U.S. disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Neurological disorders account for 5.1% of total U.S. DALYs.

Impact on the family

Not only does stigma affect individuals, it affects family members as well. Family members suffer from SBA, or stigma by association (Brit. J. Psych. 2002;181:494-8), also known as courtesy stigma (Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593-602). Families share stigma because families share a genetic heritage. Families share stigma by assuming responsibility for their family members’ behaviors. Families share stigma because they are seen as having common motivations (J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:224-41).

SBA causes psychological distress in family members (Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58:73-80; J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1987;175:4-11; Br. J. Psychiatry 2002;181:494-8; and Schizophr. Bull. 1998;24:115-126).

Psychological complaints, such as brooding, inner unrest, and irritability, and physical complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, and neck and shoulder pain, have been attributed to the psychological distress of SBA. Family members may avoid social interactions and conceal their relationship to the family member who is mentally ill (Acad. Psychiatry 2008;32:87-91). They might psychologically distance themselves from a relative with mental illness.

SBA varies by disease type, family role, and age. The greatest SBA is associated with drug dependence. These family members are blamed for the illness, held responsible for relapse, and viewed as incompetent. In the study of Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., (J. Fam. Psychol. 2006;20:239-46), family members report feelings of "contamination" and shame. Severe depression or panic and phobias engender less stigma. More educated people are less likely to report feelings of stigma.

According to Dr. Corrigan, SBA varies by family role: Parents are blamed for causing the child’s mental illness, siblings are blamed for not ensuring that relatives with mental illness adhere to treatment plans, and children are fearful of being "contaminated" with the mental illness of their parent. The closer the relationship, the less the stigma is perceived as defining the person. Family closeness can reduce stigma (The Gerontologist 2012;52:89-97). Regarding age, a British study showed that the highest stigma is reported in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (Br. J. Psychiatry 2000;177:4-7).

Psychiatry as a profession has not helped diminish stigma. It is not uncommon to hear psychiatrists assign blame to parents or spouses. Psychiatrists often believe that the family has a role in the patient’s illness. How many spouses have been told they are "codependent" with the implication that they have somehow "caused the illness"? What can we do diminish stigma?

Fighting stigma

Fighting stigma means confronting stigma (Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000;6:65-72). Most efforts worldwide have begun with the idea of educating people about mental illness. These efforts, focused on promoting mental illness as a biological illness, have had limited success and in some situations actually increased stigma (Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012; 125:440-52). The answer may lie in targeted education: specific facts for specific groups.

For example, young couples with children become less fearful after education targeted specifically for them (Br. J. Psychiatry 1996;168:191-8). Antistigma campaigns are common throughout the world. The websites of most professional psychiatric organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, provide information about antistigma campaigns. Organizations often partner with mental health charities. Antistigma efforts also focus on publishing articles about stigma as the Lancet did in a series a few years ago (1998;352:1048). It is unclear whether these efforts reduce stigma. Dr. Corrigan suggests that meeting people who have mental illness weakens the tendency to link mental illness and violence (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002;6: 312-34).

The current consensus is that antistigma campaigns should focus on the competence of people with mental illness. In this vein, the Scottish Mental Health Arts & Film Festival highlights the contributions that people with mental illness make to society. The festival, which began in 2007, also sponsors a contest for films that depict people with mental illness in realistic, holistic ways. In 2013, the festival drew 12,000 attendees and sparked 120 newspaper articles that emphasized the fact that people with mental illness are generally active, useful members of society.

Meanwhile, a Canadian antistigma campaign tells the stories of people with mental illness and provides evidence of the competence of these people. The APA’s public service video series, "A Healthy Minds Minute," features celebrities and prominent figures calling for equal access to quality care, and insurance coverage for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

What do we do to reduce stigma? Psychiatrists such as William Beardslee have written about their personal experience of a family member with mental illness. A member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists, Julie Totten, lost her brother to suicide and in response, she developed an organization called Families for Depression Awareness, which is devoted to reducing the stigma of mental illness. For me, it is my personal campaign to say: "One in four means that someone in everyone’s family has mental illness."

What more can we do?

• Speak up when you hear or see stigma.

• Stress the normalcy of people who have mental illness.

• Come out of the closet on behalf of yourself or a family member.

• Include people who acknowledge they suffer from mental illness in antistigma campaigns.

• Discuss the role of stigma with patients and their families. Ask "How has stigma affected you as a family? In what ways has your family helped reduce the stigma of your mental illness?"

• Encourage attendance at support groups, such as NAMI (the National Alliance on Mental Illness).

• Embrace your family member or yourself: Look for personal qualities that wipe out stigma.

• Don’t allow people to stigmatize patients: It might be your family member they are talking about.

• Talk positively about respecting our patients.

• Start a conversation to reduce stigma.

• Remember that fighting stigma means confronting stigma.

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. She is the author of a new book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Each year, 60 million Americans experience mental illness. Across the United States, each year, regardless of race, age, religion, or economic status, mental illness affects the lives of one in four adults and one in 10 children. This means that someone in every family has mental illness.

Most of our patients probably don’t tell anyone that they or one of their family members has mental illness They probably are doing what most of us do: Pretend it’s not there. Why? Because the stigma of mental illness is pervasive and destructive. What can we do to decrease the stigma?

The word stigma is derived from Greek and means "to mark the body." The bearer of the mark, or the stigma, is avoided and shunned. This practice has continued through the ages. In medieval times, if a person had a mental illness, he or she was thought to be possessed by demons and viewed as weak. Today, people with mental illness are viewed as menacing, deviant, unpredictable, incompetent, or even dangerous. It is entirely reasonable then, that we would want to avoid the stigma of mental illness. However, this prejudice against mental illness must be challenged.

Mental illness accounts for increased morbidity and mortality as well as lifetime disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States, followed by cardiovascular and circulatory diseases, and neoplasms. The neuropsychiatric disorders category, which includes mental and behavioral disorders, accounts for 13.6% of total U.S. disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Neurological disorders account for 5.1% of total U.S. DALYs.

Impact on the family

Not only does stigma affect individuals, it affects family members as well. Family members suffer from SBA, or stigma by association (Brit. J. Psych. 2002;181:494-8), also known as courtesy stigma (Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593-602). Families share stigma because families share a genetic heritage. Families share stigma by assuming responsibility for their family members’ behaviors. Families share stigma because they are seen as having common motivations (J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:224-41).

SBA causes psychological distress in family members (Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58:73-80; J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1987;175:4-11; Br. J. Psychiatry 2002;181:494-8; and Schizophr. Bull. 1998;24:115-126).

Psychological complaints, such as brooding, inner unrest, and irritability, and physical complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, and neck and shoulder pain, have been attributed to the psychological distress of SBA. Family members may avoid social interactions and conceal their relationship to the family member who is mentally ill (Acad. Psychiatry 2008;32:87-91). They might psychologically distance themselves from a relative with mental illness.

SBA varies by disease type, family role, and age. The greatest SBA is associated with drug dependence. These family members are blamed for the illness, held responsible for relapse, and viewed as incompetent. In the study of Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., (J. Fam. Psychol. 2006;20:239-46), family members report feelings of "contamination" and shame. Severe depression or panic and phobias engender less stigma. More educated people are less likely to report feelings of stigma.

According to Dr. Corrigan, SBA varies by family role: Parents are blamed for causing the child’s mental illness, siblings are blamed for not ensuring that relatives with mental illness adhere to treatment plans, and children are fearful of being "contaminated" with the mental illness of their parent. The closer the relationship, the less the stigma is perceived as defining the person. Family closeness can reduce stigma (The Gerontologist 2012;52:89-97). Regarding age, a British study showed that the highest stigma is reported in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (Br. J. Psychiatry 2000;177:4-7).

Psychiatry as a profession has not helped diminish stigma. It is not uncommon to hear psychiatrists assign blame to parents or spouses. Psychiatrists often believe that the family has a role in the patient’s illness. How many spouses have been told they are "codependent" with the implication that they have somehow "caused the illness"? What can we do diminish stigma?

Fighting stigma

Fighting stigma means confronting stigma (Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000;6:65-72). Most efforts worldwide have begun with the idea of educating people about mental illness. These efforts, focused on promoting mental illness as a biological illness, have had limited success and in some situations actually increased stigma (Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012; 125:440-52). The answer may lie in targeted education: specific facts for specific groups.

For example, young couples with children become less fearful after education targeted specifically for them (Br. J. Psychiatry 1996;168:191-8). Antistigma campaigns are common throughout the world. The websites of most professional psychiatric organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, provide information about antistigma campaigns. Organizations often partner with mental health charities. Antistigma efforts also focus on publishing articles about stigma as the Lancet did in a series a few years ago (1998;352:1048). It is unclear whether these efforts reduce stigma. Dr. Corrigan suggests that meeting people who have mental illness weakens the tendency to link mental illness and violence (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002;6: 312-34).

The current consensus is that antistigma campaigns should focus on the competence of people with mental illness. In this vein, the Scottish Mental Health Arts & Film Festival highlights the contributions that people with mental illness make to society. The festival, which began in 2007, also sponsors a contest for films that depict people with mental illness in realistic, holistic ways. In 2013, the festival drew 12,000 attendees and sparked 120 newspaper articles that emphasized the fact that people with mental illness are generally active, useful members of society.

Meanwhile, a Canadian antistigma campaign tells the stories of people with mental illness and provides evidence of the competence of these people. The APA’s public service video series, "A Healthy Minds Minute," features celebrities and prominent figures calling for equal access to quality care, and insurance coverage for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

What do we do to reduce stigma? Psychiatrists such as William Beardslee have written about their personal experience of a family member with mental illness. A member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists, Julie Totten, lost her brother to suicide and in response, she developed an organization called Families for Depression Awareness, which is devoted to reducing the stigma of mental illness. For me, it is my personal campaign to say: "One in four means that someone in everyone’s family has mental illness."

What more can we do?

• Speak up when you hear or see stigma.

• Stress the normalcy of people who have mental illness.

• Come out of the closet on behalf of yourself or a family member.

• Include people who acknowledge they suffer from mental illness in antistigma campaigns.

• Discuss the role of stigma with patients and their families. Ask "How has stigma affected you as a family? In what ways has your family helped reduce the stigma of your mental illness?"

• Encourage attendance at support groups, such as NAMI (the National Alliance on Mental Illness).

• Embrace your family member or yourself: Look for personal qualities that wipe out stigma.

• Don’t allow people to stigmatize patients: It might be your family member they are talking about.

• Talk positively about respecting our patients.

• Start a conversation to reduce stigma.

• Remember that fighting stigma means confronting stigma.

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. She is the author of a new book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Monosomal karyotype, high prognostic risk score predicted transplantation failure

Monosomal karyotype and high prognostic risk according to the revised International Prognostic Scoring System are independent predictors of relapse and mortality in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, according to findings from the GITMO (Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo) registry.

Treatment failure after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be from transplant complications or relapse. To understand the predictors of failure, investigators studied outcomes in 519 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation between 2000 and 2011.

Those with monosomal karyotype had a 49% relapse rate and a 10% 5-year overall survival rate; both rates were significantly worse, compared with patients without monosomal karyotype (P less than .001 for each). Those considered high or very-high risk based on the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R), had 39% and 23% 5-year overall survival, respectively, and 23% and 39% relapse rates, respectively (P less than .001 in all cases vs. patients not at high or very-high risk), Dr. Matteo G. Della Porta of Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy and colleagues reported on behalf of the GITMO.

Age of 50 years or older and high hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index scores were independent predictors of nonrelapse mortality (P = .02; P = .017, respectively), they found (Blood 2014 [doi:10.1182/blood-2013-12-542720]).

Accounting for various combinations of patients’ ages, IPSS-R category, monosomal karyotype, and high hematopoietic cell transplantation–comorbidity index, the 5-year probability of survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation ranged from 0 to 94%. The analyses performed reinforce the concept that allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation – the only potentially curative treatment for MDS – "offers optimal eradication of myelodysplastic hematopoiesis when the procedure is performed before MDS patients progress to advanced disease stages," the investigators concluded.

The investigators reported having no disclosures.

Monosomal karyotype and high prognostic risk according to the revised International Prognostic Scoring System are independent predictors of relapse and mortality in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, according to findings from the GITMO (Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo) registry.

Treatment failure after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be from transplant complications or relapse. To understand the predictors of failure, investigators studied outcomes in 519 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation between 2000 and 2011.

Those with monosomal karyotype had a 49% relapse rate and a 10% 5-year overall survival rate; both rates were significantly worse, compared with patients without monosomal karyotype (P less than .001 for each). Those considered high or very-high risk based on the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R), had 39% and 23% 5-year overall survival, respectively, and 23% and 39% relapse rates, respectively (P less than .001 in all cases vs. patients not at high or very-high risk), Dr. Matteo G. Della Porta of Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy and colleagues reported on behalf of the GITMO.

Age of 50 years or older and high hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index scores were independent predictors of nonrelapse mortality (P = .02; P = .017, respectively), they found (Blood 2014 [doi:10.1182/blood-2013-12-542720]).

Accounting for various combinations of patients’ ages, IPSS-R category, monosomal karyotype, and high hematopoietic cell transplantation–comorbidity index, the 5-year probability of survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation ranged from 0 to 94%. The analyses performed reinforce the concept that allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation – the only potentially curative treatment for MDS – "offers optimal eradication of myelodysplastic hematopoiesis when the procedure is performed before MDS patients progress to advanced disease stages," the investigators concluded.

The investigators reported having no disclosures.

Monosomal karyotype and high prognostic risk according to the revised International Prognostic Scoring System are independent predictors of relapse and mortality in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, according to findings from the GITMO (Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo) registry.

Treatment failure after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be from transplant complications or relapse. To understand the predictors of failure, investigators studied outcomes in 519 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation between 2000 and 2011.

Those with monosomal karyotype had a 49% relapse rate and a 10% 5-year overall survival rate; both rates were significantly worse, compared with patients without monosomal karyotype (P less than .001 for each). Those considered high or very-high risk based on the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R), had 39% and 23% 5-year overall survival, respectively, and 23% and 39% relapse rates, respectively (P less than .001 in all cases vs. patients not at high or very-high risk), Dr. Matteo G. Della Porta of Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy and colleagues reported on behalf of the GITMO.

Age of 50 years or older and high hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index scores were independent predictors of nonrelapse mortality (P = .02; P = .017, respectively), they found (Blood 2014 [doi:10.1182/blood-2013-12-542720]).

Accounting for various combinations of patients’ ages, IPSS-R category, monosomal karyotype, and high hematopoietic cell transplantation–comorbidity index, the 5-year probability of survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation ranged from 0 to 94%. The analyses performed reinforce the concept that allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation – the only potentially curative treatment for MDS – "offers optimal eradication of myelodysplastic hematopoiesis when the procedure is performed before MDS patients progress to advanced disease stages," the investigators concluded.

The investigators reported having no disclosures.

FROM BLOOD

Major finding: Patients with a monosomal karyotype had a 49% relapse rate and a 10% 5-year overall survival rate, and those considered high or very-high risk based on the IPSS-R, had 39% and 23% 5-year overall survival, respectively, and 23% and 39% relapse rates, respectively.

Data source: An analysis of GITMO registry data.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no disclosures.

Cell-cycle inhibitor entinostat appeared to block azacitidine action

Coadministration with entinostat – a cell-cycle inhibitor – appears to decrease hematologic responsiveness to azacitidine treatment for high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome, according to data from an open-label, phase II randomized trial.

An earlier, phase I pilot study had suggested that the combination was effective and tolerable, however this phase II study in 149 patients (97 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and 52 patients with acute myeloid leukemia) showed a lower overall hematologic response and lower median overall survival in the combination arm, compared with the azacitidine-only arm, said Dr. Thomas Prebet, who was at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, when the work was done, but is now at Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille, France, and his colleagues.

They also performed genome-wide methylation studies on 99 specimens, finding that while demethylation in the combination arm was trending toward overall demethylation, it was significantly reduced, compared with the single agent arm, suggesting the entinostat was actually blocking the action of the azacitidine (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 March 24 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3102]).

The authors did note that the lower-dose, 10-day schedule of azacitidine, which was developed specifically for this phase II trial, appeared to double the rate of hematologic normalization, compared with that observed in a previous study using the standard 7-day schedule, suggesting that the longer schedule was more effective.

Some authors reported being consultants for and/or receiving research funding from various pharmaceutical companies. The study was partly supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America and Fulbright Franco-American Commission/Foundation.

Coadministration with entinostat – a cell-cycle inhibitor – appears to decrease hematologic responsiveness to azacitidine treatment for high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome, according to data from an open-label, phase II randomized trial.

An earlier, phase I pilot study had suggested that the combination was effective and tolerable, however this phase II study in 149 patients (97 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and 52 patients with acute myeloid leukemia) showed a lower overall hematologic response and lower median overall survival in the combination arm, compared with the azacitidine-only arm, said Dr. Thomas Prebet, who was at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, when the work was done, but is now at Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille, France, and his colleagues.

They also performed genome-wide methylation studies on 99 specimens, finding that while demethylation in the combination arm was trending toward overall demethylation, it was significantly reduced, compared with the single agent arm, suggesting the entinostat was actually blocking the action of the azacitidine (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 March 24 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3102]).

The authors did note that the lower-dose, 10-day schedule of azacitidine, which was developed specifically for this phase II trial, appeared to double the rate of hematologic normalization, compared with that observed in a previous study using the standard 7-day schedule, suggesting that the longer schedule was more effective.

Some authors reported being consultants for and/or receiving research funding from various pharmaceutical companies. The study was partly supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America and Fulbright Franco-American Commission/Foundation.

Coadministration with entinostat – a cell-cycle inhibitor – appears to decrease hematologic responsiveness to azacitidine treatment for high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome, according to data from an open-label, phase II randomized trial.

An earlier, phase I pilot study had suggested that the combination was effective and tolerable, however this phase II study in 149 patients (97 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and 52 patients with acute myeloid leukemia) showed a lower overall hematologic response and lower median overall survival in the combination arm, compared with the azacitidine-only arm, said Dr. Thomas Prebet, who was at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, when the work was done, but is now at Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille, France, and his colleagues.

They also performed genome-wide methylation studies on 99 specimens, finding that while demethylation in the combination arm was trending toward overall demethylation, it was significantly reduced, compared with the single agent arm, suggesting the entinostat was actually blocking the action of the azacitidine (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 March 24 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3102]).

The authors did note that the lower-dose, 10-day schedule of azacitidine, which was developed specifically for this phase II trial, appeared to double the rate of hematologic normalization, compared with that observed in a previous study using the standard 7-day schedule, suggesting that the longer schedule was more effective.

Some authors reported being consultants for and/or receiving research funding from various pharmaceutical companies. The study was partly supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America and Fulbright Franco-American Commission/Foundation.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Major finding: The addition of cell-cycle inhibitor entinostat to a 10-day schedule of treatment with azacitidine led to a lower overall hematologic response and lower median overall survival in the patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, compared with treatment with azacitidine alone.

Data source: An open-label, phase II randomized trial in 149 patients (97 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and 52 patients with acute myeloid leukemia).

Disclosures: Some authors reported being consultants for and/or receiving research funding from various pharmaceutical companies. The study was partly supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America and Fulbright Franco-American Commission/Foundation.

EC approves SC formulation of rituximab

The European Commission (EC) has approved a subcutaneous (SC) formulation of rituximab (MabThera) to treat patients with follicular lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

This formulation allows for 5-minute administration, a significant decrease over the 2.5-hour infusion time required to administer intravenous (IV) rituximab.

The drug’s maker, Roche, plans to begin launching SC rituximab in a number of European markets this year.

The EC’s approval of this formulation was primarily based on data from the SABRINA trial, which was recently published in The Lancet Oncology and funded by Roche.

In this phase 3 trial, researchers compared 3-week cycles of fixed-dose, SC rituximab to IV rituximab. They enrolled 127 patients with previously untreated, grade 1-3a, CD20-positive follicular lymphoma.

Patients were randomized to receive IV rituximab (375 mg/m2) or SC rituximab (1400 mg). After randomization, they received 1 induction dose of IV rituximab in cycle 1 and then their allocated treatment for cycles 2 through 8. Patients with a complete or partial response continued their treatment as maintenance every 8 weeks.

The study’s primary endpoint was the ratio of observed rituximab serum trough concentrations (Ctrough) between the 2 groups at cycle 7.

Pharmacokinetic data were available for 75% of patients (48/64) in the IV arm and 86% of the patients (54/63) in the SC arm.

An analysis of these data suggested SC rituximab was non-inferior to the IV formulation. The geometric mean Ctrough was 83.13 μg/mL in the IV arm and 134.58 μg/mL in the SC arm (ratio, 1.62).

The rate of adverse events was similar between the 2 arms, occurring in 88% (57/65) of patients in the IV arm and 92% (57/62) of patients in the SC arm. Grade 3 or higher adverse events occurred in 46% (n=30) and 47% (n=29) of patients, respectively.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse event in both arms was neutropenia. It occurred in 22% (n=14) of patients in the IV arm and 26% (n=16) in the SC arm.

Adverse events related to administration were mostly grade 1-2. And they occurred more often in the SC arm than in the IV arm, in 50% (n=31) and 32% (n=21) of patients, respectively.

The researchers said these results suggest the SC formulation of rituximab is non-inferior to the IV formulation and poses no new safety concerns. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved a subcutaneous (SC) formulation of rituximab (MabThera) to treat patients with follicular lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

This formulation allows for 5-minute administration, a significant decrease over the 2.5-hour infusion time required to administer intravenous (IV) rituximab.

The drug’s maker, Roche, plans to begin launching SC rituximab in a number of European markets this year.

The EC’s approval of this formulation was primarily based on data from the SABRINA trial, which was recently published in The Lancet Oncology and funded by Roche.

In this phase 3 trial, researchers compared 3-week cycles of fixed-dose, SC rituximab to IV rituximab. They enrolled 127 patients with previously untreated, grade 1-3a, CD20-positive follicular lymphoma.

Patients were randomized to receive IV rituximab (375 mg/m2) or SC rituximab (1400 mg). After randomization, they received 1 induction dose of IV rituximab in cycle 1 and then their allocated treatment for cycles 2 through 8. Patients with a complete or partial response continued their treatment as maintenance every 8 weeks.

The study’s primary endpoint was the ratio of observed rituximab serum trough concentrations (Ctrough) between the 2 groups at cycle 7.

Pharmacokinetic data were available for 75% of patients (48/64) in the IV arm and 86% of the patients (54/63) in the SC arm.

An analysis of these data suggested SC rituximab was non-inferior to the IV formulation. The geometric mean Ctrough was 83.13 μg/mL in the IV arm and 134.58 μg/mL in the SC arm (ratio, 1.62).

The rate of adverse events was similar between the 2 arms, occurring in 88% (57/65) of patients in the IV arm and 92% (57/62) of patients in the SC arm. Grade 3 or higher adverse events occurred in 46% (n=30) and 47% (n=29) of patients, respectively.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse event in both arms was neutropenia. It occurred in 22% (n=14) of patients in the IV arm and 26% (n=16) in the SC arm.

Adverse events related to administration were mostly grade 1-2. And they occurred more often in the SC arm than in the IV arm, in 50% (n=31) and 32% (n=21) of patients, respectively.

The researchers said these results suggest the SC formulation of rituximab is non-inferior to the IV formulation and poses no new safety concerns. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved a subcutaneous (SC) formulation of rituximab (MabThera) to treat patients with follicular lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

This formulation allows for 5-minute administration, a significant decrease over the 2.5-hour infusion time required to administer intravenous (IV) rituximab.

The drug’s maker, Roche, plans to begin launching SC rituximab in a number of European markets this year.

The EC’s approval of this formulation was primarily based on data from the SABRINA trial, which was recently published in The Lancet Oncology and funded by Roche.

In this phase 3 trial, researchers compared 3-week cycles of fixed-dose, SC rituximab to IV rituximab. They enrolled 127 patients with previously untreated, grade 1-3a, CD20-positive follicular lymphoma.

Patients were randomized to receive IV rituximab (375 mg/m2) or SC rituximab (1400 mg). After randomization, they received 1 induction dose of IV rituximab in cycle 1 and then their allocated treatment for cycles 2 through 8. Patients with a complete or partial response continued their treatment as maintenance every 8 weeks.

The study’s primary endpoint was the ratio of observed rituximab serum trough concentrations (Ctrough) between the 2 groups at cycle 7.

Pharmacokinetic data were available for 75% of patients (48/64) in the IV arm and 86% of the patients (54/63) in the SC arm.

An analysis of these data suggested SC rituximab was non-inferior to the IV formulation. The geometric mean Ctrough was 83.13 μg/mL in the IV arm and 134.58 μg/mL in the SC arm (ratio, 1.62).

The rate of adverse events was similar between the 2 arms, occurring in 88% (57/65) of patients in the IV arm and 92% (57/62) of patients in the SC arm. Grade 3 or higher adverse events occurred in 46% (n=30) and 47% (n=29) of patients, respectively.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse event in both arms was neutropenia. It occurred in 22% (n=14) of patients in the IV arm and 26% (n=16) in the SC arm.

Adverse events related to administration were mostly grade 1-2. And they occurred more often in the SC arm than in the IV arm, in 50% (n=31) and 32% (n=21) of patients, respectively.

The researchers said these results suggest the SC formulation of rituximab is non-inferior to the IV formulation and poses no new safety concerns. ![]()

ALL cells don’t survive SSC culture method

Results of a pilot study suggest safe transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) may be possible, potentially bringing us one step closer to ensuring fertility preservation in young boys with cancer.

Investigators found they could culture a large amount of SSCs using testicular tissue from boys with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

And the ALL cells did not survive the culture process.

The researchers reported these results in Fertility and Sterility.

“Our study addressed an important safety issue—whether cancer cells that might be present in testicular tissue samples can survive the process to replicate the sperm-producing stem cells,” said study author Hooman Sadri-Ardekani, MD, PhD, of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

“This is an important consideration because of the potential to re-introduce cancer into the patient. The research, which involved one of the most common childhood cancers, shows that the cancer cells were eliminated. Based on these findings, we recommend that all boys with cancer be offered the option of storing testicular tissue for possible future clinical use.”

Previous research had shown that up to 30% of boys with ALL had cancer cells in their testicular tissue. In several studies, researchers attempted to eliminate cancer cells from biopsy tissue, but the results varied.

So Dr Sadri-Ardekani and his colleagues decided to investigate whether cancer cells would survive the protocol they had developed to reproduce SSCs from a small tissue biopsy.

This process multiplies the original SSCs by 18,000-fold so there are enough cells to transplant back into the patient when he reaches adulthood.

The investigators tested the method using samples from 3 ALL patients. The team cultured the ALL cells alone and at various concentrations in combination with testicular cells.

The ALL cells cultured alone did not survive beyond 14 days. But the testicular cells cultured in parallel survived and continue to proliferate well after 8 weeks.

At 10 to 16 days, the ALL cells cultured in combination had begun to die off. The cells were undetectable in cultures from 2 of the patients that had an initial ALL concentration of 0.04%, 0.4%, or 4%.

At 20 to 26 days, ALL cells were undetectable in all cultures, even those with an initial concentration of 40% ALL cells.

“This pilot study showed that the culture system not only allowed for efficient propagation of sperm stem cells but also eliminated ALL cells,” Dr Sadri-Ardekani said.

SSC transplants have not yet been attempted in humans, but they have been performed successfully in several species of animals, including monkeys.

Dr Sadri-Ardekani noted that before we can perform SSC transplants in patients, additional research is needed, particularly, research investigating whether other types of leukemia cells will also be eliminated in the cell-propagation process. ![]()

Results of a pilot study suggest safe transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) may be possible, potentially bringing us one step closer to ensuring fertility preservation in young boys with cancer.

Investigators found they could culture a large amount of SSCs using testicular tissue from boys with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

And the ALL cells did not survive the culture process.

The researchers reported these results in Fertility and Sterility.

“Our study addressed an important safety issue—whether cancer cells that might be present in testicular tissue samples can survive the process to replicate the sperm-producing stem cells,” said study author Hooman Sadri-Ardekani, MD, PhD, of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

“This is an important consideration because of the potential to re-introduce cancer into the patient. The research, which involved one of the most common childhood cancers, shows that the cancer cells were eliminated. Based on these findings, we recommend that all boys with cancer be offered the option of storing testicular tissue for possible future clinical use.”

Previous research had shown that up to 30% of boys with ALL had cancer cells in their testicular tissue. In several studies, researchers attempted to eliminate cancer cells from biopsy tissue, but the results varied.

So Dr Sadri-Ardekani and his colleagues decided to investigate whether cancer cells would survive the protocol they had developed to reproduce SSCs from a small tissue biopsy.

This process multiplies the original SSCs by 18,000-fold so there are enough cells to transplant back into the patient when he reaches adulthood.

The investigators tested the method using samples from 3 ALL patients. The team cultured the ALL cells alone and at various concentrations in combination with testicular cells.

The ALL cells cultured alone did not survive beyond 14 days. But the testicular cells cultured in parallel survived and continue to proliferate well after 8 weeks.

At 10 to 16 days, the ALL cells cultured in combination had begun to die off. The cells were undetectable in cultures from 2 of the patients that had an initial ALL concentration of 0.04%, 0.4%, or 4%.

At 20 to 26 days, ALL cells were undetectable in all cultures, even those with an initial concentration of 40% ALL cells.

“This pilot study showed that the culture system not only allowed for efficient propagation of sperm stem cells but also eliminated ALL cells,” Dr Sadri-Ardekani said.

SSC transplants have not yet been attempted in humans, but they have been performed successfully in several species of animals, including monkeys.

Dr Sadri-Ardekani noted that before we can perform SSC transplants in patients, additional research is needed, particularly, research investigating whether other types of leukemia cells will also be eliminated in the cell-propagation process. ![]()

Results of a pilot study suggest safe transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) may be possible, potentially bringing us one step closer to ensuring fertility preservation in young boys with cancer.

Investigators found they could culture a large amount of SSCs using testicular tissue from boys with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

And the ALL cells did not survive the culture process.

The researchers reported these results in Fertility and Sterility.

“Our study addressed an important safety issue—whether cancer cells that might be present in testicular tissue samples can survive the process to replicate the sperm-producing stem cells,” said study author Hooman Sadri-Ardekani, MD, PhD, of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

“This is an important consideration because of the potential to re-introduce cancer into the patient. The research, which involved one of the most common childhood cancers, shows that the cancer cells were eliminated. Based on these findings, we recommend that all boys with cancer be offered the option of storing testicular tissue for possible future clinical use.”

Previous research had shown that up to 30% of boys with ALL had cancer cells in their testicular tissue. In several studies, researchers attempted to eliminate cancer cells from biopsy tissue, but the results varied.

So Dr Sadri-Ardekani and his colleagues decided to investigate whether cancer cells would survive the protocol they had developed to reproduce SSCs from a small tissue biopsy.

This process multiplies the original SSCs by 18,000-fold so there are enough cells to transplant back into the patient when he reaches adulthood.

The investigators tested the method using samples from 3 ALL patients. The team cultured the ALL cells alone and at various concentrations in combination with testicular cells.

The ALL cells cultured alone did not survive beyond 14 days. But the testicular cells cultured in parallel survived and continue to proliferate well after 8 weeks.

At 10 to 16 days, the ALL cells cultured in combination had begun to die off. The cells were undetectable in cultures from 2 of the patients that had an initial ALL concentration of 0.04%, 0.4%, or 4%.

At 20 to 26 days, ALL cells were undetectable in all cultures, even those with an initial concentration of 40% ALL cells.

“This pilot study showed that the culture system not only allowed for efficient propagation of sperm stem cells but also eliminated ALL cells,” Dr Sadri-Ardekani said.

SSC transplants have not yet been attempted in humans, but they have been performed successfully in several species of animals, including monkeys.

Dr Sadri-Ardekani noted that before we can perform SSC transplants in patients, additional research is needed, particularly, research investigating whether other types of leukemia cells will also be eliminated in the cell-propagation process. ![]()

CDC reports more cases of Heartland virus disease

Credit: CDC

Health officials have reported 6 new cases of Heartland virus disease—5 in Missouri and 1 in Tennessee.

These cases, discovered in 2012 and 2013, add to the 2 cases discovered in 2009 and are described in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The Heartland virus was first reported in 2 farmers in northwestern Missouri who were hospitalized in 2009 with what was thought to be ehrlichiosis, a tick-borne disease.

However, the patients failed to improve with treatment, and testing failed to confirm ehlrlichiosis.

Working with state and local partners, the CDC eventually identified the cause of the men’s illness: a previously unknown phlebovirus, now dubbed the Heartland virus.

Although we do not know for certain how patients are infected with the virus, research has suggested that ticks, namely lone star ticks, transmit it.

Ongoing investigations have uncovered 6 more cases of Heartland virus disease. All of the patients were white men older than 50 years of age. Five of them reported tick bites in the days or weeks before they fell ill.

Their symptoms started in May to September and included fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, headache, nausea, and muscle pain. The patients also had leukopenia and thrombocytopenia.

Four of the 6 patients were hospitalized. And 1 man, who suffered from other health conditions, died. It is not known if the Heartland virus was the cause of death or how much it contributed to his death.

The CDC has been working with the Missouri and Tennessee state health departments and other federal agencies to advance our understanding of Heartland virus disease by learning more about the patients who were infected, their illness, and their exposure to ticks.

The CDC aims to determine the symptoms and severity of the disease, where it is found, how people are being infected, and how to prevent infections.

CDC studies to date have shown that the Heartland virus is carried by lone star ticks, which are primarily found in the southeastern and eastern US.

Researchers hope additional studies can confirm whether ticks can spread the virus and reveal which other insects or animals may be involved in the transmission cycle. The CDC is also looking for the Heartland virus in other parts of the country to understand how widely it may be distributed.

“During the past 2 years, CDC has worked closely with state health departments, hospitals, and many experts from universities and other federal agencies to learn more about Heartland virus,” said Roger Nasci, PhD, chief of the CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch.

“By gathering information about the disease Heartland virus causes, and about how it’s spread to people, we hope to better understand the potential impact on the public’s health and how we can help protect people from this virus.”

The CDC developed the blood tests used to confirm the new cases of Heartland virus disease. CDC teams are working to further validate these tests and develop additional tests. The researchers hope to develop a diagnostic test that public health laboratories could use to test for the virus.

There is no specific treatment or vaccine for Heartland virus disease. However, supportive therapies such as intravenous fluids and fever reducers can relieve some symptoms of Heartland disease.

To reduce the risk of Heartland and other vector-borne diseases, the CDC recommends:

- Avoiding wooded and bushy areas with high grass and leaf litter

- Using insect repellent when outdoors

- Using products that contain permethrin on clothing

- Conducting a full-body tick check after spending time outdoors

- Bathing as soon as possible after coming indoors to wash off and more easily find any ticks

- Examining gear and pets, as ticks can “ride” into the home and attach to a person later.

For more information on the Heartland virus, visit the CDC website. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Health officials have reported 6 new cases of Heartland virus disease—5 in Missouri and 1 in Tennessee.

These cases, discovered in 2012 and 2013, add to the 2 cases discovered in 2009 and are described in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The Heartland virus was first reported in 2 farmers in northwestern Missouri who were hospitalized in 2009 with what was thought to be ehrlichiosis, a tick-borne disease.

However, the patients failed to improve with treatment, and testing failed to confirm ehlrlichiosis.

Working with state and local partners, the CDC eventually identified the cause of the men’s illness: a previously unknown phlebovirus, now dubbed the Heartland virus.

Although we do not know for certain how patients are infected with the virus, research has suggested that ticks, namely lone star ticks, transmit it.

Ongoing investigations have uncovered 6 more cases of Heartland virus disease. All of the patients were white men older than 50 years of age. Five of them reported tick bites in the days or weeks before they fell ill.

Their symptoms started in May to September and included fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, headache, nausea, and muscle pain. The patients also had leukopenia and thrombocytopenia.

Four of the 6 patients were hospitalized. And 1 man, who suffered from other health conditions, died. It is not known if the Heartland virus was the cause of death or how much it contributed to his death.

The CDC has been working with the Missouri and Tennessee state health departments and other federal agencies to advance our understanding of Heartland virus disease by learning more about the patients who were infected, their illness, and their exposure to ticks.

The CDC aims to determine the symptoms and severity of the disease, where it is found, how people are being infected, and how to prevent infections.

CDC studies to date have shown that the Heartland virus is carried by lone star ticks, which are primarily found in the southeastern and eastern US.

Researchers hope additional studies can confirm whether ticks can spread the virus and reveal which other insects or animals may be involved in the transmission cycle. The CDC is also looking for the Heartland virus in other parts of the country to understand how widely it may be distributed.

“During the past 2 years, CDC has worked closely with state health departments, hospitals, and many experts from universities and other federal agencies to learn more about Heartland virus,” said Roger Nasci, PhD, chief of the CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch.

“By gathering information about the disease Heartland virus causes, and about how it’s spread to people, we hope to better understand the potential impact on the public’s health and how we can help protect people from this virus.”

The CDC developed the blood tests used to confirm the new cases of Heartland virus disease. CDC teams are working to further validate these tests and develop additional tests. The researchers hope to develop a diagnostic test that public health laboratories could use to test for the virus.

There is no specific treatment or vaccine for Heartland virus disease. However, supportive therapies such as intravenous fluids and fever reducers can relieve some symptoms of Heartland disease.

To reduce the risk of Heartland and other vector-borne diseases, the CDC recommends:

- Avoiding wooded and bushy areas with high grass and leaf litter

- Using insect repellent when outdoors

- Using products that contain permethrin on clothing

- Conducting a full-body tick check after spending time outdoors

- Bathing as soon as possible after coming indoors to wash off and more easily find any ticks

- Examining gear and pets, as ticks can “ride” into the home and attach to a person later.

For more information on the Heartland virus, visit the CDC website. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Health officials have reported 6 new cases of Heartland virus disease—5 in Missouri and 1 in Tennessee.

These cases, discovered in 2012 and 2013, add to the 2 cases discovered in 2009 and are described in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The Heartland virus was first reported in 2 farmers in northwestern Missouri who were hospitalized in 2009 with what was thought to be ehrlichiosis, a tick-borne disease.

However, the patients failed to improve with treatment, and testing failed to confirm ehlrlichiosis.

Working with state and local partners, the CDC eventually identified the cause of the men’s illness: a previously unknown phlebovirus, now dubbed the Heartland virus.

Although we do not know for certain how patients are infected with the virus, research has suggested that ticks, namely lone star ticks, transmit it.

Ongoing investigations have uncovered 6 more cases of Heartland virus disease. All of the patients were white men older than 50 years of age. Five of them reported tick bites in the days or weeks before they fell ill.

Their symptoms started in May to September and included fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, headache, nausea, and muscle pain. The patients also had leukopenia and thrombocytopenia.

Four of the 6 patients were hospitalized. And 1 man, who suffered from other health conditions, died. It is not known if the Heartland virus was the cause of death or how much it contributed to his death.

The CDC has been working with the Missouri and Tennessee state health departments and other federal agencies to advance our understanding of Heartland virus disease by learning more about the patients who were infected, their illness, and their exposure to ticks.

The CDC aims to determine the symptoms and severity of the disease, where it is found, how people are being infected, and how to prevent infections.

CDC studies to date have shown that the Heartland virus is carried by lone star ticks, which are primarily found in the southeastern and eastern US.

Researchers hope additional studies can confirm whether ticks can spread the virus and reveal which other insects or animals may be involved in the transmission cycle. The CDC is also looking for the Heartland virus in other parts of the country to understand how widely it may be distributed.

“During the past 2 years, CDC has worked closely with state health departments, hospitals, and many experts from universities and other federal agencies to learn more about Heartland virus,” said Roger Nasci, PhD, chief of the CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch.

“By gathering information about the disease Heartland virus causes, and about how it’s spread to people, we hope to better understand the potential impact on the public’s health and how we can help protect people from this virus.”

The CDC developed the blood tests used to confirm the new cases of Heartland virus disease. CDC teams are working to further validate these tests and develop additional tests. The researchers hope to develop a diagnostic test that public health laboratories could use to test for the virus.

There is no specific treatment or vaccine for Heartland virus disease. However, supportive therapies such as intravenous fluids and fever reducers can relieve some symptoms of Heartland disease.

To reduce the risk of Heartland and other vector-borne diseases, the CDC recommends:

- Avoiding wooded and bushy areas with high grass and leaf litter

- Using insect repellent when outdoors

- Using products that contain permethrin on clothing

- Conducting a full-body tick check after spending time outdoors

- Bathing as soon as possible after coming indoors to wash off and more easily find any ticks

- Examining gear and pets, as ticks can “ride” into the home and attach to a person later.

For more information on the Heartland virus, visit the CDC website. ![]()

FDA approves factor for hemophilia B

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc, Alprolix) for use in adults and children with hemophilia B.

The product is intended to help control, prevent, or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes that can occur day-to-day in patients with hemophilia B, as well as manage bleeding in patients undergoing surgery.

rFIXFc is made by fusing factor IX to the Fc portion of the IgG1 protein. Scientists believe this enables the product to use a naturally occurring pathway to prolong the time the therapy remains in the body.

The FDA’s approval is the second worldwide approval of rFIXFc. The product was recently authorized for use in Canada.

Researchers evaluated the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of rFIXFc in the phase 3 B-LONG study, which was funded by the product’s developers, Biogen Idec and Sobi.

Investigators tested rFIXFc in 123 males with hemophilia B who were at least 12 years of age. The patients were assigned to 1 of 4 treatment arms: weekly prophylaxis, individualized-interval prophylaxis, on-demand treatment to control bleeding, and perioperative management.

The overall median annualized bleeding rates were 2.95 for the weekly prophylaxis arm, 1.38 for the individualized-interval prophylaxis arm, and 17.69 in the on-demand treatment arm.

The overall median dosing interval with individualized-interval prophylaxis was 12.5 days. During the last 6 months of the study, the median dosing interval was 13.8 days.

Of the patients who received rFIXFc for perioperative management, 85.7% required a single injection of the product to maintain hemostasis during their operation. The median dose was 90.9 IU/kg per injection.

Most patients required 1 to 2 injections of the product the day before and the day of surgery. And most required 2 to 3 injections from days 1 to 3 after surgery.

The most common adverse events associated with rFIXFc (an incidence of ≥ 5% in a pooled analysis of treatment arms 1, 2, and 3) were nasopharyngitis, influenza, arthralgia, upper respiratory tract infection, hypertension, and headache.

The results of this study were released by Biogen Idec and Sobi in September 2012, presented at ISTH 2013, and published in NEJM in December 2013. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc, Alprolix) for use in adults and children with hemophilia B.

The product is intended to help control, prevent, or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes that can occur day-to-day in patients with hemophilia B, as well as manage bleeding in patients undergoing surgery.

rFIXFc is made by fusing factor IX to the Fc portion of the IgG1 protein. Scientists believe this enables the product to use a naturally occurring pathway to prolong the time the therapy remains in the body.

The FDA’s approval is the second worldwide approval of rFIXFc. The product was recently authorized for use in Canada.

Researchers evaluated the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of rFIXFc in the phase 3 B-LONG study, which was funded by the product’s developers, Biogen Idec and Sobi.

Investigators tested rFIXFc in 123 males with hemophilia B who were at least 12 years of age. The patients were assigned to 1 of 4 treatment arms: weekly prophylaxis, individualized-interval prophylaxis, on-demand treatment to control bleeding, and perioperative management.

The overall median annualized bleeding rates were 2.95 for the weekly prophylaxis arm, 1.38 for the individualized-interval prophylaxis arm, and 17.69 in the on-demand treatment arm.

The overall median dosing interval with individualized-interval prophylaxis was 12.5 days. During the last 6 months of the study, the median dosing interval was 13.8 days.

Of the patients who received rFIXFc for perioperative management, 85.7% required a single injection of the product to maintain hemostasis during their operation. The median dose was 90.9 IU/kg per injection.

Most patients required 1 to 2 injections of the product the day before and the day of surgery. And most required 2 to 3 injections from days 1 to 3 after surgery.

The most common adverse events associated with rFIXFc (an incidence of ≥ 5% in a pooled analysis of treatment arms 1, 2, and 3) were nasopharyngitis, influenza, arthralgia, upper respiratory tract infection, hypertension, and headache.

The results of this study were released by Biogen Idec and Sobi in September 2012, presented at ISTH 2013, and published in NEJM in December 2013. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc, Alprolix) for use in adults and children with hemophilia B.

The product is intended to help control, prevent, or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes that can occur day-to-day in patients with hemophilia B, as well as manage bleeding in patients undergoing surgery.

rFIXFc is made by fusing factor IX to the Fc portion of the IgG1 protein. Scientists believe this enables the product to use a naturally occurring pathway to prolong the time the therapy remains in the body.

The FDA’s approval is the second worldwide approval of rFIXFc. The product was recently authorized for use in Canada.

Researchers evaluated the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of rFIXFc in the phase 3 B-LONG study, which was funded by the product’s developers, Biogen Idec and Sobi.

Investigators tested rFIXFc in 123 males with hemophilia B who were at least 12 years of age. The patients were assigned to 1 of 4 treatment arms: weekly prophylaxis, individualized-interval prophylaxis, on-demand treatment to control bleeding, and perioperative management.

The overall median annualized bleeding rates were 2.95 for the weekly prophylaxis arm, 1.38 for the individualized-interval prophylaxis arm, and 17.69 in the on-demand treatment arm.

The overall median dosing interval with individualized-interval prophylaxis was 12.5 days. During the last 6 months of the study, the median dosing interval was 13.8 days.

Of the patients who received rFIXFc for perioperative management, 85.7% required a single injection of the product to maintain hemostasis during their operation. The median dose was 90.9 IU/kg per injection.

Most patients required 1 to 2 injections of the product the day before and the day of surgery. And most required 2 to 3 injections from days 1 to 3 after surgery.

The most common adverse events associated with rFIXFc (an incidence of ≥ 5% in a pooled analysis of treatment arms 1, 2, and 3) were nasopharyngitis, influenza, arthralgia, upper respiratory tract infection, hypertension, and headache.

The results of this study were released by Biogen Idec and Sobi in September 2012, presented at ISTH 2013, and published in NEJM in December 2013. ![]()

Novel anticoagulants get nod in new AF guidelines

New guidelines for managing patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation recommend dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, as well as warfarin, and call on physicians to use a more comprehensive stroke risk calculator.

"I think physicians are still learning how to use the newer anticoagulants, and this is something that will require time," said Dr. Craig T. January, chair of the AF guidelines committee, assembled by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society.

The guidelines, published in Circulation and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, focus on nonvalvular AF and feature a detailed dosing chart organized by anticoagulant type and renal function, which is impaired in up to 20% of those with AF.

"The goal was to create a straightforward chart on how to use these drugs," said Dr. January, a clinician/scientist with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) are not recommended for AF patients with nonvalvular disease and end-stage kidney disease, either on or off dialysis, because of a lack of evidence from clinical trials regarding the balance of risks and benefits.

No recommendation was made for apixaban (Eliquis) in patients with severe or end-stage renal impairment, because of a lack of published data, although a recent secondary analysis of the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial suggests the direct factor Xa inhibitor provides the greatest reduction in major bleeding in patients with impaired renal function compared with warfarin (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2821-30).

The guidelines advise clinicians to evaluate renal function prior to initiating any of the direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors, and to reevaluate at least annually and when clinically indicated.

Previously, warfarin (Coumadin) was the only recommended anticoagulant in the 2006 guidelines. It’s admittedly cheaper, but the guidelines note that the novel anticoagulants eliminate dietary limitations and the need for repeated international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring, and have more predictable pharmacological profiles and fewer drug-drug interactions.

The oral agents have revolutionized the treatment of AF since entering the market in the past few years, but by no means replace warfarin.

For patients with nonvalvular AF who are well controlled and satisfied with warfarin therapy, the guidelines say, "It is not necessary to change to one of the newer agents," Dr. January observed.

Warfarin should also be used for valvular AF to manage patients with a mechanical heart valve or hemodynamically significant mitral stenosis because these populations were excluded from all three major trials – RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy With Dabigatran Etexilate), ROCKET-AF (An Efficacy and Safety Study of Rivaroxaban With Warfarin for the Prevention of Stroke and Non-Central Nervous System Systemic Embolism in Patients With Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation), and ARISTOTLE – that led to the approval of the newer anticoagulants.

Dabigatran is specifically not recommended for patients with a mechanical valve because of the potential for harm, which was recently recognized by the Food and Drug Administration.

The document includes a section on dose interruption and bridging therapy, which in part reflects the fact that the new oral agents carry a black box warning from the FDA because discontinuation can increase the risk of thromboembolism. In addition, reversal agents are in development, but they are not currently available should immediate reversal be needed.

The new recommendations will elicit discussion, but are not expected to be controversial like the updated cholesterol management guidelines recently released by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, Dr. January said.

Another noteworthy change is the diminished use of aspirin in preventing stroke. "Most of the published data have shown that aspirin is not as effective as full anticoagulation and that aspirin itself in many trials has little benefit. This was a point of a lot of discussion in the committee," he said.

To calculate stroke risk, the guidelines recommend that clinicians use the CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 75 or older (doubled), Diabetes mellitus, Prior Stroke or TIA or thromboembolism (doubled), Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category female) calculator because it has a broader score range (0 to 9) and includes a larger number of risk factors than the older CHADS2 score.