User login

Internists’ use of ultrasound can reduce radiology referrals

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

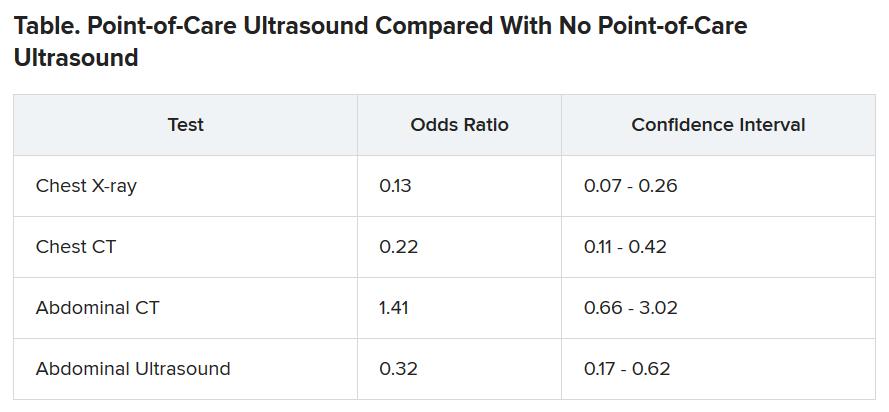

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Acute EVALI remains a diagnosis of exclusion

according to a synthesis of current information presented at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Respiratory symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath are common but so are constitutive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, said Yamini Kuchipudi, MD, a staff physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, during the session at the virtual meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

If EVALI is not considered across this broad array of symptoms, of which respiratory complaints might not be the most prominent at the time of presentation, the diagnosis might be delayed, Dr. Kuchipudi warned during the virtual meeting.

Teenagers and young adults are the most common users of e-cigarettes and vaping devices. In these patients or in any individual suspected of having EVALI, Dr. Kuchipudi recommended posing questions about vaping relatively early in the work-up “in a confidential and nonjudgmental way.”

Eliciting a truthful history will be particularly important, because the risk of EVALI appears to be largely related to vaping with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products rather than with nicotine alone. Although the exact cause of EVALI is not yet completely clear, this condition is now strongly associated with additives to the THC, according to Issa Hanna, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

“E-liquid contains products like hydrocarbons, vitamin E acetate, and heavy metals that appear to damage the alveolar epithelium by direct cellular inflammation,” Dr. Hanna explained.

These products are not only found in THC processed for vaping but also for dabbing, a related but different form of inhalation that involves vaporization of highly concentrated THC waxes or resins. Dr. Hanna suggested that the decline in reported cases of EVALI, which has followed the peak incidence in September 2019, is likely to be related to a decline in THC additives as well as greater caution among users.

E-cigarettes were introduced in 2007, according to Dr. Hanna, but EVALI was not widely recognized until cases began accruing early in 2019. By June 2019, the growing number of case reports had attracted the attention of the media as well as public health officials, intensifying the effort to isolate the risks and causes.

Consistent with greater use of e-cigarettes and vaping among younger individuals, nearly 80% of the 2,807 patients hospitalized for EVALI in the United States by February of this year occurred in individuals aged less than 35 years, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The median age was less than 25 years. Of these hospitalizations, 68 deaths (2.5%) in 29 states and Washington, D.C., were attributed to EVALI.

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of a definitive diagnostic test, EVALI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, according to Abigail Musial, MD, who is completing a fellowship in hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s. She presented a case in which a patient suspected of EVALI went home after symptoms abated on steroids.

“Less than 24 hours later, she returned to the ED with tachypnea and hypoxemia,” Dr. Musial recounted. Although a chest x-ray at the initial evaluation showed lung opacities, a repeat chest x-ray when she returned to the ED showed bilateral worsening of these opacities and persistent elevation of inflammatory markers.

“She was started on steroids and also on antibiotics,” Dr. Musial said. “She was weaned quickly from oxygen once the steroids were started and was discharged on hospital day 3.”

For patients suspected of EVALI, COVID-19 testing should be part of the work-up, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. She also recommended an x-ray or CT scan of the lung as well as an evaluation of inflammatory markers.

Dr. Kuchipudi said that more invasive studies than lung function tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy, might be considered when severe symptoms make aggressive diagnostic studies attractive.

Steroids and antibiotics typically lead to control of acute symptoms, but patients should be clinically stable for 24-48 hours prior to hospital discharge, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. Follow-up after discharge should include lung function tests and imaging 2-4 weeks later to confirm resolution of abnormalities.

Dr. Kuchipudi stressed the opportunity that an episode of EVALI provides to induce patients to give up nicotine and vaping entirely. Such strategies, such as a nicotine patch, deserve consideration, but she also cautioned that e-cigarettes for smoking cessation should not be recommended to EVALI patients.

The speakers reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

according to a synthesis of current information presented at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Respiratory symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath are common but so are constitutive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, said Yamini Kuchipudi, MD, a staff physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, during the session at the virtual meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

If EVALI is not considered across this broad array of symptoms, of which respiratory complaints might not be the most prominent at the time of presentation, the diagnosis might be delayed, Dr. Kuchipudi warned during the virtual meeting.

Teenagers and young adults are the most common users of e-cigarettes and vaping devices. In these patients or in any individual suspected of having EVALI, Dr. Kuchipudi recommended posing questions about vaping relatively early in the work-up “in a confidential and nonjudgmental way.”

Eliciting a truthful history will be particularly important, because the risk of EVALI appears to be largely related to vaping with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products rather than with nicotine alone. Although the exact cause of EVALI is not yet completely clear, this condition is now strongly associated with additives to the THC, according to Issa Hanna, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

“E-liquid contains products like hydrocarbons, vitamin E acetate, and heavy metals that appear to damage the alveolar epithelium by direct cellular inflammation,” Dr. Hanna explained.

These products are not only found in THC processed for vaping but also for dabbing, a related but different form of inhalation that involves vaporization of highly concentrated THC waxes or resins. Dr. Hanna suggested that the decline in reported cases of EVALI, which has followed the peak incidence in September 2019, is likely to be related to a decline in THC additives as well as greater caution among users.

E-cigarettes were introduced in 2007, according to Dr. Hanna, but EVALI was not widely recognized until cases began accruing early in 2019. By June 2019, the growing number of case reports had attracted the attention of the media as well as public health officials, intensifying the effort to isolate the risks and causes.

Consistent with greater use of e-cigarettes and vaping among younger individuals, nearly 80% of the 2,807 patients hospitalized for EVALI in the United States by February of this year occurred in individuals aged less than 35 years, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The median age was less than 25 years. Of these hospitalizations, 68 deaths (2.5%) in 29 states and Washington, D.C., were attributed to EVALI.

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of a definitive diagnostic test, EVALI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, according to Abigail Musial, MD, who is completing a fellowship in hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s. She presented a case in which a patient suspected of EVALI went home after symptoms abated on steroids.

“Less than 24 hours later, she returned to the ED with tachypnea and hypoxemia,” Dr. Musial recounted. Although a chest x-ray at the initial evaluation showed lung opacities, a repeat chest x-ray when she returned to the ED showed bilateral worsening of these opacities and persistent elevation of inflammatory markers.

“She was started on steroids and also on antibiotics,” Dr. Musial said. “She was weaned quickly from oxygen once the steroids were started and was discharged on hospital day 3.”

For patients suspected of EVALI, COVID-19 testing should be part of the work-up, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. She also recommended an x-ray or CT scan of the lung as well as an evaluation of inflammatory markers.

Dr. Kuchipudi said that more invasive studies than lung function tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy, might be considered when severe symptoms make aggressive diagnostic studies attractive.

Steroids and antibiotics typically lead to control of acute symptoms, but patients should be clinically stable for 24-48 hours prior to hospital discharge, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. Follow-up after discharge should include lung function tests and imaging 2-4 weeks later to confirm resolution of abnormalities.

Dr. Kuchipudi stressed the opportunity that an episode of EVALI provides to induce patients to give up nicotine and vaping entirely. Such strategies, such as a nicotine patch, deserve consideration, but she also cautioned that e-cigarettes for smoking cessation should not be recommended to EVALI patients.

The speakers reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

according to a synthesis of current information presented at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Respiratory symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath are common but so are constitutive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, said Yamini Kuchipudi, MD, a staff physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, during the session at the virtual meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

If EVALI is not considered across this broad array of symptoms, of which respiratory complaints might not be the most prominent at the time of presentation, the diagnosis might be delayed, Dr. Kuchipudi warned during the virtual meeting.

Teenagers and young adults are the most common users of e-cigarettes and vaping devices. In these patients or in any individual suspected of having EVALI, Dr. Kuchipudi recommended posing questions about vaping relatively early in the work-up “in a confidential and nonjudgmental way.”

Eliciting a truthful history will be particularly important, because the risk of EVALI appears to be largely related to vaping with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products rather than with nicotine alone. Although the exact cause of EVALI is not yet completely clear, this condition is now strongly associated with additives to the THC, according to Issa Hanna, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

“E-liquid contains products like hydrocarbons, vitamin E acetate, and heavy metals that appear to damage the alveolar epithelium by direct cellular inflammation,” Dr. Hanna explained.

These products are not only found in THC processed for vaping but also for dabbing, a related but different form of inhalation that involves vaporization of highly concentrated THC waxes or resins. Dr. Hanna suggested that the decline in reported cases of EVALI, which has followed the peak incidence in September 2019, is likely to be related to a decline in THC additives as well as greater caution among users.

E-cigarettes were introduced in 2007, according to Dr. Hanna, but EVALI was not widely recognized until cases began accruing early in 2019. By June 2019, the growing number of case reports had attracted the attention of the media as well as public health officials, intensifying the effort to isolate the risks and causes.

Consistent with greater use of e-cigarettes and vaping among younger individuals, nearly 80% of the 2,807 patients hospitalized for EVALI in the United States by February of this year occurred in individuals aged less than 35 years, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The median age was less than 25 years. Of these hospitalizations, 68 deaths (2.5%) in 29 states and Washington, D.C., were attributed to EVALI.

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of a definitive diagnostic test, EVALI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, according to Abigail Musial, MD, who is completing a fellowship in hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s. She presented a case in which a patient suspected of EVALI went home after symptoms abated on steroids.

“Less than 24 hours later, she returned to the ED with tachypnea and hypoxemia,” Dr. Musial recounted. Although a chest x-ray at the initial evaluation showed lung opacities, a repeat chest x-ray when she returned to the ED showed bilateral worsening of these opacities and persistent elevation of inflammatory markers.

“She was started on steroids and also on antibiotics,” Dr. Musial said. “She was weaned quickly from oxygen once the steroids were started and was discharged on hospital day 3.”

For patients suspected of EVALI, COVID-19 testing should be part of the work-up, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. She also recommended an x-ray or CT scan of the lung as well as an evaluation of inflammatory markers.

Dr. Kuchipudi said that more invasive studies than lung function tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy, might be considered when severe symptoms make aggressive diagnostic studies attractive.

Steroids and antibiotics typically lead to control of acute symptoms, but patients should be clinically stable for 24-48 hours prior to hospital discharge, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. Follow-up after discharge should include lung function tests and imaging 2-4 weeks later to confirm resolution of abnormalities.

Dr. Kuchipudi stressed the opportunity that an episode of EVALI provides to induce patients to give up nicotine and vaping entirely. Such strategies, such as a nicotine patch, deserve consideration, but she also cautioned that e-cigarettes for smoking cessation should not be recommended to EVALI patients.

The speakers reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

FROM PHM20

New oral anticoagulants drive ACC consensus on bleeding

Patients on oral anticoagulants who experience a bleeding event may be able to discontinue therapy if certain circumstances apply, according to updated guidance from the American College of Cardiology.

The emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to prevent venous thromboembolism and the introduction of new reversal strategies for factor Xa inhibitors prompted the creation of an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway to update the version from 2017, according to the ACC. Expert consensus decision pathways (ECDPs) are a component of the solution sets issued by the ACC to “address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care.”

In an ECDP published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the writing committee members developed treatment algorithms for managing bleeding in patients on DOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

Bleeding was classified as major or nonmajor, with major defined as “bleeding that is associated with hemodynamic compromise, occurs in an anatomically critical site, requires transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells [RBCs]), or results in a hemoglobin drop greater than 2 g/dL. All other types of bleeding were classified as nonmajor.

The document includes a graphic algorithm for assessing bleed severity and managing major versus nonmajor bleeding, and a separate graphic describes considerations for reversal and use of hemostatic agents according to whether the patient is taking a VKA (warfarin and other coumarins), a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran), the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban, or the factor Xa inhibitors betrixaban and edoxaban.

Another algorithm outlines whether to discontinue, delay, or restart anticoagulation. Considerations for restarting anticoagulation include whether the patient is pregnant, awaiting an invasive procedure, not able to receive medication by mouth, has a high risk of rebleeding, or is being bridged back to a vitamin K antagonist with high thrombotic risk.

In most cases of GI bleeding, for example, current data support restarting oral anticoagulants once hemostasis is achieved, but patients who experience intracranial hemorrhage should delay restarting any anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks if they are without high thrombotic risk, according to the document.

The report also recommends clinician-patient discussion before resuming anticoagulation, ideally with time allowed for patients to develop questions. Discussions should include the signs of bleeding, assessment of risk for a thromboembolic event, and the benefits of anticoagulation.

“The proliferation of oral anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) and growing indications for their use prompted the need for guidance on the management of these drugs,” said Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, chair of the writing committee, in an interview. “This document provides guidance on management at the time of a bleeding complication. This includes acute management, starting and stopping drugs, and use of reversal agents,” he said. “This of course will be a dynamic document as the list of these drugs and their antidotes expand,” he noted.

“The biggest change from the previous guidelines are twofold: an update on laboratory assessment to monitor drug levels and use of reversal agents,” while the acute management strategies have otherwise remained similar to previous documents, said Dr. Tomaselli.

Dr. Tomaselli said that he was not surprised by the biological aspects of recent research while developing the statement. However, “the extent of the use of multiple anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents was a bit surprising and complicates therapy with each of the agents,” he noted.

The way the pathways are presented may make them challenging to follow in clinical practice, said Dr. Tomaselli. “The pathways are described linearly and in practice often many things have to happen at once,” he said. “The other main issue may be limitations in the availability of some of the newer reversal agents,” he added.

“The complication of bleeding is difficult to avoid,” said Dr. Tomaselli, and for future research, “the focus needs to continue to refine the indications for anticoagulation and appropriate use with other drugs that predispose to bleeding. We also need better methods and testing to monitor drugs levels and the effect on coagulation,” he said.

In accordance with the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, the writing committee members, including Dr. Tomaselli, had no relevant relationships with industry to disclose.

SOURCE: Tomaselli GF et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.053.

Patients on oral anticoagulants who experience a bleeding event may be able to discontinue therapy if certain circumstances apply, according to updated guidance from the American College of Cardiology.

The emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to prevent venous thromboembolism and the introduction of new reversal strategies for factor Xa inhibitors prompted the creation of an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway to update the version from 2017, according to the ACC. Expert consensus decision pathways (ECDPs) are a component of the solution sets issued by the ACC to “address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care.”

In an ECDP published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the writing committee members developed treatment algorithms for managing bleeding in patients on DOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

Bleeding was classified as major or nonmajor, with major defined as “bleeding that is associated with hemodynamic compromise, occurs in an anatomically critical site, requires transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells [RBCs]), or results in a hemoglobin drop greater than 2 g/dL. All other types of bleeding were classified as nonmajor.

The document includes a graphic algorithm for assessing bleed severity and managing major versus nonmajor bleeding, and a separate graphic describes considerations for reversal and use of hemostatic agents according to whether the patient is taking a VKA (warfarin and other coumarins), a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran), the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban, or the factor Xa inhibitors betrixaban and edoxaban.

Another algorithm outlines whether to discontinue, delay, or restart anticoagulation. Considerations for restarting anticoagulation include whether the patient is pregnant, awaiting an invasive procedure, not able to receive medication by mouth, has a high risk of rebleeding, or is being bridged back to a vitamin K antagonist with high thrombotic risk.

In most cases of GI bleeding, for example, current data support restarting oral anticoagulants once hemostasis is achieved, but patients who experience intracranial hemorrhage should delay restarting any anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks if they are without high thrombotic risk, according to the document.

The report also recommends clinician-patient discussion before resuming anticoagulation, ideally with time allowed for patients to develop questions. Discussions should include the signs of bleeding, assessment of risk for a thromboembolic event, and the benefits of anticoagulation.

“The proliferation of oral anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) and growing indications for their use prompted the need for guidance on the management of these drugs,” said Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, chair of the writing committee, in an interview. “This document provides guidance on management at the time of a bleeding complication. This includes acute management, starting and stopping drugs, and use of reversal agents,” he said. “This of course will be a dynamic document as the list of these drugs and their antidotes expand,” he noted.

“The biggest change from the previous guidelines are twofold: an update on laboratory assessment to monitor drug levels and use of reversal agents,” while the acute management strategies have otherwise remained similar to previous documents, said Dr. Tomaselli.

Dr. Tomaselli said that he was not surprised by the biological aspects of recent research while developing the statement. However, “the extent of the use of multiple anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents was a bit surprising and complicates therapy with each of the agents,” he noted.

The way the pathways are presented may make them challenging to follow in clinical practice, said Dr. Tomaselli. “The pathways are described linearly and in practice often many things have to happen at once,” he said. “The other main issue may be limitations in the availability of some of the newer reversal agents,” he added.

“The complication of bleeding is difficult to avoid,” said Dr. Tomaselli, and for future research, “the focus needs to continue to refine the indications for anticoagulation and appropriate use with other drugs that predispose to bleeding. We also need better methods and testing to monitor drugs levels and the effect on coagulation,” he said.

In accordance with the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, the writing committee members, including Dr. Tomaselli, had no relevant relationships with industry to disclose.

SOURCE: Tomaselli GF et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.053.

Patients on oral anticoagulants who experience a bleeding event may be able to discontinue therapy if certain circumstances apply, according to updated guidance from the American College of Cardiology.

The emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to prevent venous thromboembolism and the introduction of new reversal strategies for factor Xa inhibitors prompted the creation of an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway to update the version from 2017, according to the ACC. Expert consensus decision pathways (ECDPs) are a component of the solution sets issued by the ACC to “address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care.”

In an ECDP published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the writing committee members developed treatment algorithms for managing bleeding in patients on DOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

Bleeding was classified as major or nonmajor, with major defined as “bleeding that is associated with hemodynamic compromise, occurs in an anatomically critical site, requires transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells [RBCs]), or results in a hemoglobin drop greater than 2 g/dL. All other types of bleeding were classified as nonmajor.

The document includes a graphic algorithm for assessing bleed severity and managing major versus nonmajor bleeding, and a separate graphic describes considerations for reversal and use of hemostatic agents according to whether the patient is taking a VKA (warfarin and other coumarins), a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran), the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban, or the factor Xa inhibitors betrixaban and edoxaban.

Another algorithm outlines whether to discontinue, delay, or restart anticoagulation. Considerations for restarting anticoagulation include whether the patient is pregnant, awaiting an invasive procedure, not able to receive medication by mouth, has a high risk of rebleeding, or is being bridged back to a vitamin K antagonist with high thrombotic risk.

In most cases of GI bleeding, for example, current data support restarting oral anticoagulants once hemostasis is achieved, but patients who experience intracranial hemorrhage should delay restarting any anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks if they are without high thrombotic risk, according to the document.

The report also recommends clinician-patient discussion before resuming anticoagulation, ideally with time allowed for patients to develop questions. Discussions should include the signs of bleeding, assessment of risk for a thromboembolic event, and the benefits of anticoagulation.

“The proliferation of oral anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) and growing indications for their use prompted the need for guidance on the management of these drugs,” said Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, chair of the writing committee, in an interview. “This document provides guidance on management at the time of a bleeding complication. This includes acute management, starting and stopping drugs, and use of reversal agents,” he said. “This of course will be a dynamic document as the list of these drugs and their antidotes expand,” he noted.

“The biggest change from the previous guidelines are twofold: an update on laboratory assessment to monitor drug levels and use of reversal agents,” while the acute management strategies have otherwise remained similar to previous documents, said Dr. Tomaselli.

Dr. Tomaselli said that he was not surprised by the biological aspects of recent research while developing the statement. However, “the extent of the use of multiple anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents was a bit surprising and complicates therapy with each of the agents,” he noted.

The way the pathways are presented may make them challenging to follow in clinical practice, said Dr. Tomaselli. “The pathways are described linearly and in practice often many things have to happen at once,” he said. “The other main issue may be limitations in the availability of some of the newer reversal agents,” he added.

“The complication of bleeding is difficult to avoid,” said Dr. Tomaselli, and for future research, “the focus needs to continue to refine the indications for anticoagulation and appropriate use with other drugs that predispose to bleeding. We also need better methods and testing to monitor drugs levels and the effect on coagulation,” he said.

In accordance with the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, the writing committee members, including Dr. Tomaselli, had no relevant relationships with industry to disclose.

SOURCE: Tomaselli GF et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.053.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Medics with ‘long COVID’ call for clinical recognition

Thousands of coronavirus patients risk going without treatment and support for debilitating symptoms lasting months because of a lack of awareness of ‘long COVID’, according to a group formed by clinicians with extended serious after-effects of the virus.

Many members of the 100-strong Facebook group UK doctors: COVID “Long tail” have been unable to work for weeks after failing to recover from an episode of COVID-19. They warn of the need for clinical recognition of “long COVID,” along with systems to log symptoms and manage patients in the community. Without this, there could be major consequences for return to work across all professions, as well as implications for disease prevention.

‘Weird symptoms’

Three of the group: Dr Amali Lokugamage, consultant obstetrician at the Whittington Hospital; Dr Sharon Taylor, child psychiatrist at St Mary’s Hospital London, and Dr Clare Rayner, a retired occupational health physician and lecturer at the University of Manchester, have highlighted their concerns in The BMJ and on social media groups. They say colleagues are observing a range of symptoms of long COVID in their practices.

These include cardiac, gut and respiratory symptoms, skin manifestations, neurological and psychiatric symptoms, severe fatigue, and relapsing fevers, sometimes continuing for more than 16 weeks, and which they say go well beyond definitions of chronic fatigue. The authors are also aware of a pattern of symptom clusters recurring every third or fourth day, which in some cases are so severe that people are having to take extended periods of sick leave.

Writing in The BMJ the authors say: “Concerns have been raised about the lack of awareness among NHS doctors, nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals with regard to the prolonged, varied, and weird symptoms [of COVID-19].”

Speaking to Medscape News UK, Dr. Clare Rayner said: “We see a huge need that is not being met, because these cases are just not being seen in hospital. All the attention has been on the acute illness.”

She pointed to the urgent need for government planning for a surge in people requiring support to return to work following long-term COVID-19 symptoms. According to occupational health research, only 10-40% of people who take 6 weeks off work return to work, dropping to 5%-10% after an absence of 6 months.

In her own case, she is recovering after 4 months of illness, including a hospital admission with gut symptoms and dehydration, and 2 weeks of social service home support. She has experienced a range of relapsing and remitting symptoms, which she describes as ‘bizarre and coming in phases’.

Stimulating recovery

The recently-announced NHS portal for COVID-19 patients has been welcomed by the authors as an opportunity for long-standing symptoms to reach the medical and Government radar. But Dr Taylor believes it should have been set up from the start with input from patients with symptoms, to make sure that any support provided reflects the nature of the problems experienced.

In her case, as a previously regular gym attender with a resting heart rate in the 50s, she has now been diagnosed as having multi-organ disease affecting her heart, spleen, lung, and autonomic system. She has fluid on the lungs and heart, and suffers from continuous chest pain and oxygen desaturation when lying down. She has not been able to work since she contracted COVID-19 in March.

“COVID patients with the chronic form of the disease need to be involved in research right from the start to ensure the right questions are asked - not just those who have had acute disease,” she insists to Medscape News UK. “We need to gather evidence, to inform the development of a multi-disciplinary approach and a range of rehabilitation options depending on the organs involved.

“The focus needs to be on stimulating recovery and preventing development of chronic problems. We still don’t know if those with chronic COVID disease are infectious, how long their prolonged cardio-respiratory and neurological complications will last, and crucially whether treatment will reduce the duration of their problems. The worry is that left unattended, these patients may develop irreversible damage leading to chronic illness.”

General practice

GPs have been at the forefront of management of the long-standing consequences of COVID-19. In its recent report General practice in the post-COVID world, the Royal College of General Practitioners highlights the need for urgent government planning and funding to prepare general practice services for facilitating the recovery of local communities.

The report calls on the four governments of the UK each to produce a comprehensive plan to support GPs in managing the longer-term effects of COVID-19 in the community, including costed proposals for additional funding for general practice; workforce solutions; reductions in regulatory burdens and ‘red tape’; a systematic approach for identifying patients most likely to need primary care support, and proposals for how health inequalities will be minimized to ensure all patients have access to the necessary post-COVID-19 care.

RCGP Chair Professor Martin Marshall said: “COVID-19 will leave a lingering and difficult legacy and it is GPs working with patients in their communities who will be picking up the pieces.”

One issue is the lack of a reliable estimate of the prevalence of post viral symptoms for other viruses, let alone for COVID-19. Even a 1% chance of long-term problems amongst survivors would suggest 2500 with a need for extra support, but experience with post-viral syndrome generally suggests the prevalence may be more like 3%.

The BMA has been carrying out tracker surveys of its own members at 2-week intervals since March. The most recent, involving more than 5000 doctors, indicated that around 30% of doctors who believed they’d had COVID-19 were still experiencing physical symptoms they thought were caused by the virus, 21% had taken sick leave, and a further 9% had taken annual leave to deal with ongoing symptoms.

Dr David Strain, chair of the BMA medical academic staff committee and clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, has a particular interest in the after-effects of COVID-19. He said it was becoming evident that the virus was leaving a lasting legacy with a significant number of people, even younger ones.

He told Medscape News UK: “Once COVID-19 enters the nervous system, the lasting symptoms on people can range from a mild loss of sense of smell or taste, to more severe symptoms such as difficulties in concentration. A small number have also been left with chronic fatigue syndrome, which is poorly understood, and can be difficult to treat. This does not appear to be dependent on the initial severity of COVID-19 symptoms.

“Currently, it is impossible to predict the prevalence of longer-lasting effects. A full assessment of COVID-19’s impact will only be possible once people return to work on a regular basis and the effect on their physical health becomes evident. Of the doctors in the BMA survey who had experienced COVID-19, 15% took sick leave beyond their acute illness, and another 6% used annual leave allowance to extend their recovery time.

“Clearly, more research will be needed into the long-term consequences of COVID-19 and the future treatments needed to deal with them.”

Further research

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has called for applications for research to enhance understanding and management of the health and social care consequences of the global COVID-19 pandemic beyond the acute phase, with a particular focus on ‘health outcomes, public health, social care and health service delivery and to mitigate the impact of subsequent phases and aftermath’.

The authors of The BMJ article stress the wide-ranging nature of ‘long COVID’ symptoms and warn of the dangers of treating them for research purposes under the banner of chronic fatigue. They say: “These wide-ranging, unusual, and potentially very serious symptoms can be anxiety-provoking, particularly secondary to a virus that has only been known to the world for 8 months and which we have barely begun to understand. However, it is dismissive solely to attribute such symptoms to anxiety in the thousands of patients like ourselves who have attended hospital or general practice with chronic COVID-19.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thousands of coronavirus patients risk going without treatment and support for debilitating symptoms lasting months because of a lack of awareness of ‘long COVID’, according to a group formed by clinicians with extended serious after-effects of the virus.

Many members of the 100-strong Facebook group UK doctors: COVID “Long tail” have been unable to work for weeks after failing to recover from an episode of COVID-19. They warn of the need for clinical recognition of “long COVID,” along with systems to log symptoms and manage patients in the community. Without this, there could be major consequences for return to work across all professions, as well as implications for disease prevention.

‘Weird symptoms’

Three of the group: Dr Amali Lokugamage, consultant obstetrician at the Whittington Hospital; Dr Sharon Taylor, child psychiatrist at St Mary’s Hospital London, and Dr Clare Rayner, a retired occupational health physician and lecturer at the University of Manchester, have highlighted their concerns in The BMJ and on social media groups. They say colleagues are observing a range of symptoms of long COVID in their practices.

These include cardiac, gut and respiratory symptoms, skin manifestations, neurological and psychiatric symptoms, severe fatigue, and relapsing fevers, sometimes continuing for more than 16 weeks, and which they say go well beyond definitions of chronic fatigue. The authors are also aware of a pattern of symptom clusters recurring every third or fourth day, which in some cases are so severe that people are having to take extended periods of sick leave.

Writing in The BMJ the authors say: “Concerns have been raised about the lack of awareness among NHS doctors, nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals with regard to the prolonged, varied, and weird symptoms [of COVID-19].”

Speaking to Medscape News UK, Dr. Clare Rayner said: “We see a huge need that is not being met, because these cases are just not being seen in hospital. All the attention has been on the acute illness.”

She pointed to the urgent need for government planning for a surge in people requiring support to return to work following long-term COVID-19 symptoms. According to occupational health research, only 10-40% of people who take 6 weeks off work return to work, dropping to 5%-10% after an absence of 6 months.

In her own case, she is recovering after 4 months of illness, including a hospital admission with gut symptoms and dehydration, and 2 weeks of social service home support. She has experienced a range of relapsing and remitting symptoms, which she describes as ‘bizarre and coming in phases’.

Stimulating recovery

The recently-announced NHS portal for COVID-19 patients has been welcomed by the authors as an opportunity for long-standing symptoms to reach the medical and Government radar. But Dr Taylor believes it should have been set up from the start with input from patients with symptoms, to make sure that any support provided reflects the nature of the problems experienced.

In her case, as a previously regular gym attender with a resting heart rate in the 50s, she has now been diagnosed as having multi-organ disease affecting her heart, spleen, lung, and autonomic system. She has fluid on the lungs and heart, and suffers from continuous chest pain and oxygen desaturation when lying down. She has not been able to work since she contracted COVID-19 in March.

“COVID patients with the chronic form of the disease need to be involved in research right from the start to ensure the right questions are asked - not just those who have had acute disease,” she insists to Medscape News UK. “We need to gather evidence, to inform the development of a multi-disciplinary approach and a range of rehabilitation options depending on the organs involved.

“The focus needs to be on stimulating recovery and preventing development of chronic problems. We still don’t know if those with chronic COVID disease are infectious, how long their prolonged cardio-respiratory and neurological complications will last, and crucially whether treatment will reduce the duration of their problems. The worry is that left unattended, these patients may develop irreversible damage leading to chronic illness.”

General practice

GPs have been at the forefront of management of the long-standing consequences of COVID-19. In its recent report General practice in the post-COVID world, the Royal College of General Practitioners highlights the need for urgent government planning and funding to prepare general practice services for facilitating the recovery of local communities.

The report calls on the four governments of the UK each to produce a comprehensive plan to support GPs in managing the longer-term effects of COVID-19 in the community, including costed proposals for additional funding for general practice; workforce solutions; reductions in regulatory burdens and ‘red tape’; a systematic approach for identifying patients most likely to need primary care support, and proposals for how health inequalities will be minimized to ensure all patients have access to the necessary post-COVID-19 care.

RCGP Chair Professor Martin Marshall said: “COVID-19 will leave a lingering and difficult legacy and it is GPs working with patients in their communities who will be picking up the pieces.”

One issue is the lack of a reliable estimate of the prevalence of post viral symptoms for other viruses, let alone for COVID-19. Even a 1% chance of long-term problems amongst survivors would suggest 2500 with a need for extra support, but experience with post-viral syndrome generally suggests the prevalence may be more like 3%.

The BMA has been carrying out tracker surveys of its own members at 2-week intervals since March. The most recent, involving more than 5000 doctors, indicated that around 30% of doctors who believed they’d had COVID-19 were still experiencing physical symptoms they thought were caused by the virus, 21% had taken sick leave, and a further 9% had taken annual leave to deal with ongoing symptoms.

Dr David Strain, chair of the BMA medical academic staff committee and clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, has a particular interest in the after-effects of COVID-19. He said it was becoming evident that the virus was leaving a lasting legacy with a significant number of people, even younger ones.

He told Medscape News UK: “Once COVID-19 enters the nervous system, the lasting symptoms on people can range from a mild loss of sense of smell or taste, to more severe symptoms such as difficulties in concentration. A small number have also been left with chronic fatigue syndrome, which is poorly understood, and can be difficult to treat. This does not appear to be dependent on the initial severity of COVID-19 symptoms.

“Currently, it is impossible to predict the prevalence of longer-lasting effects. A full assessment of COVID-19’s impact will only be possible once people return to work on a regular basis and the effect on their physical health becomes evident. Of the doctors in the BMA survey who had experienced COVID-19, 15% took sick leave beyond their acute illness, and another 6% used annual leave allowance to extend their recovery time.

“Clearly, more research will be needed into the long-term consequences of COVID-19 and the future treatments needed to deal with them.”

Further research

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has called for applications for research to enhance understanding and management of the health and social care consequences of the global COVID-19 pandemic beyond the acute phase, with a particular focus on ‘health outcomes, public health, social care and health service delivery and to mitigate the impact of subsequent phases and aftermath’.

The authors of The BMJ article stress the wide-ranging nature of ‘long COVID’ symptoms and warn of the dangers of treating them for research purposes under the banner of chronic fatigue. They say: “These wide-ranging, unusual, and potentially very serious symptoms can be anxiety-provoking, particularly secondary to a virus that has only been known to the world for 8 months and which we have barely begun to understand. However, it is dismissive solely to attribute such symptoms to anxiety in the thousands of patients like ourselves who have attended hospital or general practice with chronic COVID-19.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thousands of coronavirus patients risk going without treatment and support for debilitating symptoms lasting months because of a lack of awareness of ‘long COVID’, according to a group formed by clinicians with extended serious after-effects of the virus.

Many members of the 100-strong Facebook group UK doctors: COVID “Long tail” have been unable to work for weeks after failing to recover from an episode of COVID-19. They warn of the need for clinical recognition of “long COVID,” along with systems to log symptoms and manage patients in the community. Without this, there could be major consequences for return to work across all professions, as well as implications for disease prevention.

‘Weird symptoms’

Three of the group: Dr Amali Lokugamage, consultant obstetrician at the Whittington Hospital; Dr Sharon Taylor, child psychiatrist at St Mary’s Hospital London, and Dr Clare Rayner, a retired occupational health physician and lecturer at the University of Manchester, have highlighted their concerns in The BMJ and on social media groups. They say colleagues are observing a range of symptoms of long COVID in their practices.

These include cardiac, gut and respiratory symptoms, skin manifestations, neurological and psychiatric symptoms, severe fatigue, and relapsing fevers, sometimes continuing for more than 16 weeks, and which they say go well beyond definitions of chronic fatigue. The authors are also aware of a pattern of symptom clusters recurring every third or fourth day, which in some cases are so severe that people are having to take extended periods of sick leave.

Writing in The BMJ the authors say: “Concerns have been raised about the lack of awareness among NHS doctors, nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals with regard to the prolonged, varied, and weird symptoms [of COVID-19].”

Speaking to Medscape News UK, Dr. Clare Rayner said: “We see a huge need that is not being met, because these cases are just not being seen in hospital. All the attention has been on the acute illness.”

She pointed to the urgent need for government planning for a surge in people requiring support to return to work following long-term COVID-19 symptoms. According to occupational health research, only 10-40% of people who take 6 weeks off work return to work, dropping to 5%-10% after an absence of 6 months.

In her own case, she is recovering after 4 months of illness, including a hospital admission with gut symptoms and dehydration, and 2 weeks of social service home support. She has experienced a range of relapsing and remitting symptoms, which she describes as ‘bizarre and coming in phases’.

Stimulating recovery

The recently-announced NHS portal for COVID-19 patients has been welcomed by the authors as an opportunity for long-standing symptoms to reach the medical and Government radar. But Dr Taylor believes it should have been set up from the start with input from patients with symptoms, to make sure that any support provided reflects the nature of the problems experienced.

In her case, as a previously regular gym attender with a resting heart rate in the 50s, she has now been diagnosed as having multi-organ disease affecting her heart, spleen, lung, and autonomic system. She has fluid on the lungs and heart, and suffers from continuous chest pain and oxygen desaturation when lying down. She has not been able to work since she contracted COVID-19 in March.

“COVID patients with the chronic form of the disease need to be involved in research right from the start to ensure the right questions are asked - not just those who have had acute disease,” she insists to Medscape News UK. “We need to gather evidence, to inform the development of a multi-disciplinary approach and a range of rehabilitation options depending on the organs involved.

“The focus needs to be on stimulating recovery and preventing development of chronic problems. We still don’t know if those with chronic COVID disease are infectious, how long their prolonged cardio-respiratory and neurological complications will last, and crucially whether treatment will reduce the duration of their problems. The worry is that left unattended, these patients may develop irreversible damage leading to chronic illness.”

General practice

GPs have been at the forefront of management of the long-standing consequences of COVID-19. In its recent report General practice in the post-COVID world, the Royal College of General Practitioners highlights the need for urgent government planning and funding to prepare general practice services for facilitating the recovery of local communities.

The report calls on the four governments of the UK each to produce a comprehensive plan to support GPs in managing the longer-term effects of COVID-19 in the community, including costed proposals for additional funding for general practice; workforce solutions; reductions in regulatory burdens and ‘red tape’; a systematic approach for identifying patients most likely to need primary care support, and proposals for how health inequalities will be minimized to ensure all patients have access to the necessary post-COVID-19 care.

RCGP Chair Professor Martin Marshall said: “COVID-19 will leave a lingering and difficult legacy and it is GPs working with patients in their communities who will be picking up the pieces.”

One issue is the lack of a reliable estimate of the prevalence of post viral symptoms for other viruses, let alone for COVID-19. Even a 1% chance of long-term problems amongst survivors would suggest 2500 with a need for extra support, but experience with post-viral syndrome generally suggests the prevalence may be more like 3%.

The BMA has been carrying out tracker surveys of its own members at 2-week intervals since March. The most recent, involving more than 5000 doctors, indicated that around 30% of doctors who believed they’d had COVID-19 were still experiencing physical symptoms they thought were caused by the virus, 21% had taken sick leave, and a further 9% had taken annual leave to deal with ongoing symptoms.

Dr David Strain, chair of the BMA medical academic staff committee and clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, has a particular interest in the after-effects of COVID-19. He said it was becoming evident that the virus was leaving a lasting legacy with a significant number of people, even younger ones.

He told Medscape News UK: “Once COVID-19 enters the nervous system, the lasting symptoms on people can range from a mild loss of sense of smell or taste, to more severe symptoms such as difficulties in concentration. A small number have also been left with chronic fatigue syndrome, which is poorly understood, and can be difficult to treat. This does not appear to be dependent on the initial severity of COVID-19 symptoms.

“Currently, it is impossible to predict the prevalence of longer-lasting effects. A full assessment of COVID-19’s impact will only be possible once people return to work on a regular basis and the effect on their physical health becomes evident. Of the doctors in the BMA survey who had experienced COVID-19, 15% took sick leave beyond their acute illness, and another 6% used annual leave allowance to extend their recovery time.

“Clearly, more research will be needed into the long-term consequences of COVID-19 and the future treatments needed to deal with them.”

Further research

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has called for applications for research to enhance understanding and management of the health and social care consequences of the global COVID-19 pandemic beyond the acute phase, with a particular focus on ‘health outcomes, public health, social care and health service delivery and to mitigate the impact of subsequent phases and aftermath’.

The authors of The BMJ article stress the wide-ranging nature of ‘long COVID’ symptoms and warn of the dangers of treating them for research purposes under the banner of chronic fatigue. They say: “These wide-ranging, unusual, and potentially very serious symptoms can be anxiety-provoking, particularly secondary to a virus that has only been known to the world for 8 months and which we have barely begun to understand. However, it is dismissive solely to attribute such symptoms to anxiety in the thousands of patients like ourselves who have attended hospital or general practice with chronic COVID-19.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ticagrelor/aspirin combo: Fewer repeat strokes and deaths, but more bleeds

, new data show. However, severe bleeding was more common in the ticagrelor/aspirin group than in the aspirin-only group.

“We found that ticagrelor plus aspirin reduced the risk of stroke or death, compared to aspirin alone in patients presenting acutely with stroke or TIA,” reported lead author S. Claiborne Johnston, MD, PhD, dean and vice president for medical affairs, Dell Medical School, the University of Texas, Austin.

Although the combination also increased the risk for major hemorrhage, that increase was small and would not overwhelm the benefit, he said.

The study was published online July 16 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Attractive properties

“Lots of patients have stroke in the days to weeks after first presenting with a stroke or TIA,” said Dr. Johnston, who is also the Frank and Charmaine Denius Distinguished Dean’s Chair at Dell Medical School. “Aspirin has been the standard of care but is only partially effective. Clopidogrel plus aspirin is another option that has recently been proven, [but] ticagrelor has attractive properties as an antiplatelet agent and works synergistically with aspirin,” he added.

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting antiplatelet agent that does not depend on metabolic activation and that “reversibly binds” and inhibits the P2Y12 receptor on platelets. Previous research has evaluated clopidogrel and aspirin for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke or TIA. In an earlier trial, ticagrelor was no better than aspirin in preventing these subsequent events. However, the investigators noted that the combination of the two drugs has not been well studied.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involved 11,016 patients at 414 sites in 28 countries. Patients who had experienced mild to moderate acute noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (mean age, 65 years; 39% women; roughly 54% White) were randomly assigned to receive either ticagrelor plus aspirin (n = 5,523) or aspirin alone (n = 5,493) for 30 days. Of these patients, 91% had sustained a stroke, and 9% had sustained a TIA.

Thirty days was chosen as the treatment period because the risk for subsequent stroke tends to occur mainly in the first month after an acute ischemic stroke or TIA. The primary outcome was “a composite of stroke or death in a time-to-first-event analysis from randomization to 30 days of follow-up.” For the study, “stroke” encompassed ischemic, hemorrhagic, or stroke of undetermined type, and “death” included deaths of all causes. Secondary outcomes included first subsequent ischemic stroke and disability (defined as a score of >1 on the Rankin Scale).

Almost all patients (99.5%) were taking aspirin during the treatment period, and most were also taking an antihypertensive and a statin (74% and 83%, respectively).

Patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group had fewer primary-outcome events in comparison with those in the aspirin-only group (303 patients [5.5%] vs. 362 patients [6.6%]; hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.96; P = 0.02). Incidence of subsequent ischemic stroke were similarly lower in the ticagrelor/aspirin group in comparison with the aspirin-only group (276 patients [5.0%] vs. 345 patients [6.3%]; HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.93; P = .004).

On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the groups in the incidence of overall disability (23.8% of the patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group and in 24.1% of the patients in the aspirin group; odds ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89-1.07; P = .61).

There were differences between the groups in severe bleeding, which occurred in 28 patients (0.5%) in the ticagrelor/aspirin group and in seven patients (0.15) in the ticagrelor group (HR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.74-9.14; P = .001). Moreover, more patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group experienced a composite of intracranial hemorrhage or fatal bleeding compared with the aspirin-only group (0.4% vs 0.1%). Fatal bleeding occurred in 0.2% of patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group versus 0.1% of patients in the aspirin group. More patients in the ticagrelor-aspirin group permanently discontinued the treatment because of bleeding than in the aspirin-only group (2.8% vs. 0.6%).

“The benefit from treatment with ticagrelor/aspirin, as compared with aspirin alone, would be expected to result in a number needed to treat of 92 to prevent one primary outcome event, and a number needed to harm of 263 for severe bleeding,” the authors noted.

Risks versus benefits

Commenting on the study, Konark Malhotra, MD, a vascular neurologist at Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, noted that ticagrelor is an antiplatelet medication “that adds to the armamentarium of stroke neurologists for the treatment of mild acute ischemic or high-risk TIA patients.” Dr. Malhotra, who was not involved with the study, added that the “combined use of ticagrelor and aspirin is effective in the reduction of ischemic events, however, at the expense of increased risk of bleeding events.”

In an accompanying editorial, Peter Rothwell, MD, PhD, of the Wolfson Center for Prevention of Stroke and Dementia, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford (England) who was not involved with the study, suggested that the “bleeding risk associated with ticagrelor and aspirin might exceed the benefit among lower-risk patients who make up the majority in practice, and so the results should not be overgeneralized.” Moreover, “regardless of which combination of antiplatelet therapy is favored for the high-risk minority, all patients should receive aspirin immediately after TIA, unless aspirin is contraindicated.”

He noted that “too many patients are sent home from emergency departments without this simple treatment that substantially reduces the risk and severity of early recurrent stroke.”

The study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Johnston has received a grant from AstraZeneca and nonfinancial support from SANOFI. Dr. Rothwell has received personal fees from Bayer and BMS. Dr. Malhotra has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new data show. However, severe bleeding was more common in the ticagrelor/aspirin group than in the aspirin-only group.

“We found that ticagrelor plus aspirin reduced the risk of stroke or death, compared to aspirin alone in patients presenting acutely with stroke or TIA,” reported lead author S. Claiborne Johnston, MD, PhD, dean and vice president for medical affairs, Dell Medical School, the University of Texas, Austin.

Although the combination also increased the risk for major hemorrhage, that increase was small and would not overwhelm the benefit, he said.

The study was published online July 16 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Attractive properties

“Lots of patients have stroke in the days to weeks after first presenting with a stroke or TIA,” said Dr. Johnston, who is also the Frank and Charmaine Denius Distinguished Dean’s Chair at Dell Medical School. “Aspirin has been the standard of care but is only partially effective. Clopidogrel plus aspirin is another option that has recently been proven, [but] ticagrelor has attractive properties as an antiplatelet agent and works synergistically with aspirin,” he added.

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting antiplatelet agent that does not depend on metabolic activation and that “reversibly binds” and inhibits the P2Y12 receptor on platelets. Previous research has evaluated clopidogrel and aspirin for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke or TIA. In an earlier trial, ticagrelor was no better than aspirin in preventing these subsequent events. However, the investigators noted that the combination of the two drugs has not been well studied.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involved 11,016 patients at 414 sites in 28 countries. Patients who had experienced mild to moderate acute noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (mean age, 65 years; 39% women; roughly 54% White) were randomly assigned to receive either ticagrelor plus aspirin (n = 5,523) or aspirin alone (n = 5,493) for 30 days. Of these patients, 91% had sustained a stroke, and 9% had sustained a TIA.

Thirty days was chosen as the treatment period because the risk for subsequent stroke tends to occur mainly in the first month after an acute ischemic stroke or TIA. The primary outcome was “a composite of stroke or death in a time-to-first-event analysis from randomization to 30 days of follow-up.” For the study, “stroke” encompassed ischemic, hemorrhagic, or stroke of undetermined type, and “death” included deaths of all causes. Secondary outcomes included first subsequent ischemic stroke and disability (defined as a score of >1 on the Rankin Scale).

Almost all patients (99.5%) were taking aspirin during the treatment period, and most were also taking an antihypertensive and a statin (74% and 83%, respectively).

Patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group had fewer primary-outcome events in comparison with those in the aspirin-only group (303 patients [5.5%] vs. 362 patients [6.6%]; hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.96; P = 0.02). Incidence of subsequent ischemic stroke were similarly lower in the ticagrelor/aspirin group in comparison with the aspirin-only group (276 patients [5.0%] vs. 345 patients [6.3%]; HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.93; P = .004).