User login

Canagliflozin protects diabetic kidneys

Background: Type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure worldwide. Few treatment options exist to help improve on this outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Study design: CREDENCE (industry-sponsored) double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 695 sites in 34 countries, 4,401 patients.

Synopsis: The trial was stopped early after a planned interim analysis on the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee. Canagliflozin reduced serious adverse renal events or death from renal or cardiovascular causes at 2.62 years (11.1% vs. 15.5% with placebo; number needed to treat, 23).Bottom line: Canagliflozin lowered serious adverse renal events people with type 2 diabetics who also had chronic kidney disease.

Citation: Perkovic V et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 14. doi: 10-1056/NEJMoa1811744.

Dr. Hoegh is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure worldwide. Few treatment options exist to help improve on this outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Study design: CREDENCE (industry-sponsored) double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 695 sites in 34 countries, 4,401 patients.

Synopsis: The trial was stopped early after a planned interim analysis on the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee. Canagliflozin reduced serious adverse renal events or death from renal or cardiovascular causes at 2.62 years (11.1% vs. 15.5% with placebo; number needed to treat, 23).Bottom line: Canagliflozin lowered serious adverse renal events people with type 2 diabetics who also had chronic kidney disease.

Citation: Perkovic V et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 14. doi: 10-1056/NEJMoa1811744.

Dr. Hoegh is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure worldwide. Few treatment options exist to help improve on this outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Study design: CREDENCE (industry-sponsored) double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 695 sites in 34 countries, 4,401 patients.

Synopsis: The trial was stopped early after a planned interim analysis on the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee. Canagliflozin reduced serious adverse renal events or death from renal or cardiovascular causes at 2.62 years (11.1% vs. 15.5% with placebo; number needed to treat, 23).Bottom line: Canagliflozin lowered serious adverse renal events people with type 2 diabetics who also had chronic kidney disease.

Citation: Perkovic V et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 14. doi: 10-1056/NEJMoa1811744.

Dr. Hoegh is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Republican or Democrat, Americans vote for face masks

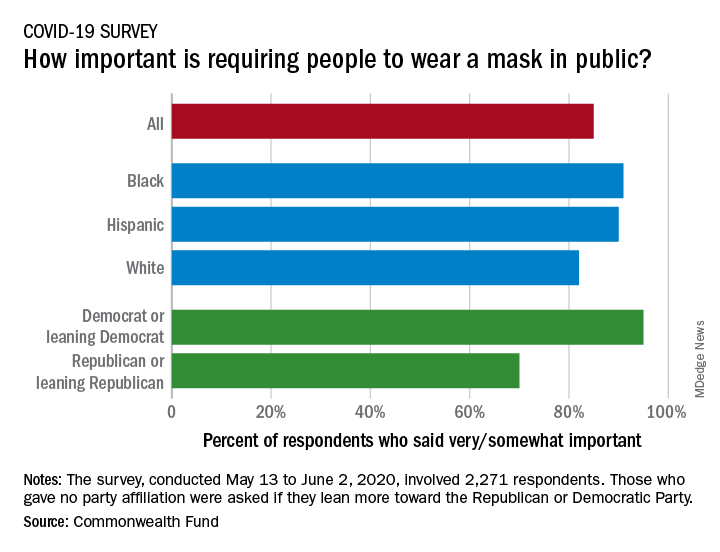

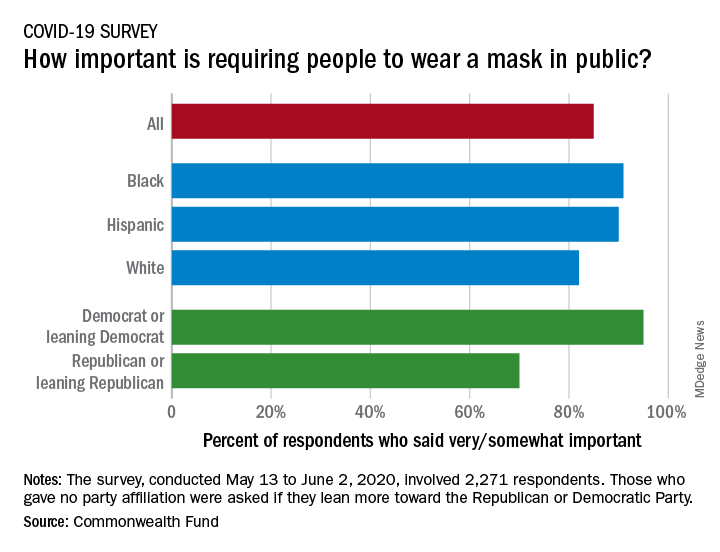

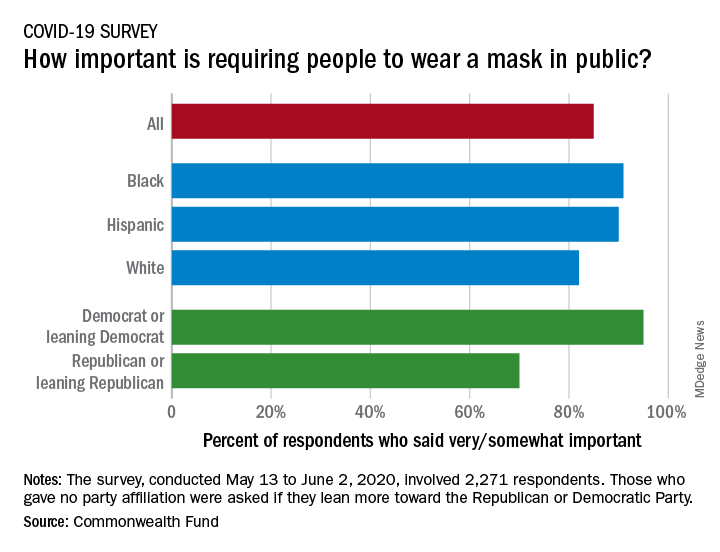

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

In that survey, conducted from May 13 to June 2, 2020, and involving 2,271 respondents, regular COVID-19 testing for everyone was supported by 81% of the sample as way to ensure a safe work environment until a vaccine is available, the researchers said in the report.

Support on both issues was consistently high across both racial/ethnic and political lines. Mandatory mask use gained 91% support among black respondents, 90% in Hispanics, and 82% in whites. There was greater distance between the political parties, but 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support mask use, compared with 95% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, they said.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that it was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Hispanics offered the most support by race/ethnicity, with 90% saying that testing was very/somewhat important, compared with 86% of black respondents and 78% of white respondents, Dr. Collins and associates said.

Two-thirds of Republicans said that it was very/somewhat important for the government to trace the contacts of any person who tested positive for COVID-19, a sentiment shared by 91% of Democrats. That type of tracing was supported by 88% of blacks, 85% of Hispanics, and 79% of whites, based on the polling results.

The survey, conducted for the Commonwealth Fund by the survey and market research firm SSRS, had a margin of error of ± 2.4 percentage points.

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

In that survey, conducted from May 13 to June 2, 2020, and involving 2,271 respondents, regular COVID-19 testing for everyone was supported by 81% of the sample as way to ensure a safe work environment until a vaccine is available, the researchers said in the report.

Support on both issues was consistently high across both racial/ethnic and political lines. Mandatory mask use gained 91% support among black respondents, 90% in Hispanics, and 82% in whites. There was greater distance between the political parties, but 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support mask use, compared with 95% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, they said.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that it was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Hispanics offered the most support by race/ethnicity, with 90% saying that testing was very/somewhat important, compared with 86% of black respondents and 78% of white respondents, Dr. Collins and associates said.

Two-thirds of Republicans said that it was very/somewhat important for the government to trace the contacts of any person who tested positive for COVID-19, a sentiment shared by 91% of Democrats. That type of tracing was supported by 88% of blacks, 85% of Hispanics, and 79% of whites, based on the polling results.

The survey, conducted for the Commonwealth Fund by the survey and market research firm SSRS, had a margin of error of ± 2.4 percentage points.

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

In that survey, conducted from May 13 to June 2, 2020, and involving 2,271 respondents, regular COVID-19 testing for everyone was supported by 81% of the sample as way to ensure a safe work environment until a vaccine is available, the researchers said in the report.

Support on both issues was consistently high across both racial/ethnic and political lines. Mandatory mask use gained 91% support among black respondents, 90% in Hispanics, and 82% in whites. There was greater distance between the political parties, but 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support mask use, compared with 95% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, they said.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that it was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Hispanics offered the most support by race/ethnicity, with 90% saying that testing was very/somewhat important, compared with 86% of black respondents and 78% of white respondents, Dr. Collins and associates said.

Two-thirds of Republicans said that it was very/somewhat important for the government to trace the contacts of any person who tested positive for COVID-19, a sentiment shared by 91% of Democrats. That type of tracing was supported by 88% of blacks, 85% of Hispanics, and 79% of whites, based on the polling results.

The survey, conducted for the Commonwealth Fund by the survey and market research firm SSRS, had a margin of error of ± 2.4 percentage points.

Three stages to COVID-19 brain damage, new review suggests

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center in McLean, Va., said.

“Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should have a neurological evaluation and ideally a brain MRI before leaving the hospital; and, if there are abnormalities, they should follow up with a neurologist in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Fotuhi, who is also affiliate staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

The review was published online June 8 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Wreaks CNS havoc

It has become “increasingly evident” that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurologic manifestations, including anosmia, seizures, stroke, confusion, encephalopathy, and total paralysis, the authors wrote.

They noted that SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, which facilitates the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin. After ACE2 has bound to respiratory epithelial cells and then to epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-CoV-2 triggers the formation of a “cytokine storm.”

These cytokines, in turn, increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation, as well as triggering “hypercoagulation cascades,” which cause small and large blood clots that affect multiple organs.

If SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier, directly entering the brain, it can contribute to demyelination or neurodegeneration.

“We very thoroughly reviewed the literature published between Jan. 1 and May 1, 2020, about neurological issues [in COVID-19] and what I found interesting is that so many neurological things can happen due to a virus which is so small,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“This virus’ DNA has such limited information, and yet it can wreak havoc on our nervous system because it kicks off such a potent defense system in our body that damages our nervous system,” he said.

Three-stage classification

- Stage 1: The extent of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptors is limited to the nasal and gustatory epithelial cells, with the cytokine storm remaining “low and controlled.” During this stage, patients may experience smell or taste impairments, but often recover without any interventions.

- Stage 2: A “robust immune response” is activated by the virus, leading to inflammation in the blood vessels, increased hypercoagulability factors, and the formation of blood clots in cerebral arteries and veins. The patient may therefore experience either large or small strokes. Additional stage 2 symptoms include fatigue, hemiplegia, sensory loss, , tetraplegia, , or ataxia.

- Stage 3: The cytokine storm in the blood vessels is so severe that it causes an “explosive inflammatory response” and penetrates the blood-brain barrier, leading to the entry of cytokines, blood components, and viral particles into the brain parenchyma and causing neuronal cell death and encephalitis. This stage can be characterized by seizures, confusion, , coma, loss of consciousness, or death.

“Patients in stage 3 are more likely to have long-term consequences, because there is evidence that the virus particles have actually penetrated the brain, and we know that SARS-CoV-2 can remain dormant in neurons for many years,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“Studies of coronaviruses have shown a link between the viruses and the risk of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease even decades later,” he added.

“Based on several reports in recent months, between 36% to 55% of patients with COVID-19 that are hospitalized have some neurological symptoms, but if you don’t look for them, you won’t see them,” Dr. Fotuhi noted.

As a result, patients should be monitored over time after discharge, as they may develop cognitive dysfunction down the road.

Additionally, “it is imperative for patients [hospitalized with COVID-19] to get a baseline MRI before leaving the hospital so that we have a starting point for future evaluation and treatment,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“The good news is that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are treatable,” and “can improve with intensive training,” including lifestyle changes – such as a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, stress reduction, improved sleep, biofeedback, and brain rehabilitation, Dr. Fotuhi added.

Routine MRI not necessary

Kenneth Tyler, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, disagreed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should routinely receive an MRI.

“Whenever you are using a piece of equipment on patients who are COVID-19 infected, you risk introducing the infection to uninfected patients,” he said. Instead, “the indication is in patients who develop unexplained neurological manifestations – altered mental status or focal seizures, for example – because in those cases, you do need to understand whether there are underlying structural abnormalities,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the review.

Also commenting on the review, Vanja Douglas, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology, University of California, San Francisco, described the review as “thorough” and suggested it may “help us understand how to design observational studies to test whether the associations are due to severe respiratory illness or are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Dr. Douglas, who was not involved in the review, added that it is “helpful in giving us a sense of which neurologic syndromes have been observed in COVID-19 patients, and therefore which patients neurologists may want to screen more carefully during the pandemic.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Fotuhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One coauthor reported receiving consulting fees as a member of the scientific advisory board for Brainreader and reports royalties for expert witness consultation in conjunction with Neurevolution. Dr. Tyler and Dr. Douglas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center in McLean, Va., said.

“Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should have a neurological evaluation and ideally a brain MRI before leaving the hospital; and, if there are abnormalities, they should follow up with a neurologist in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Fotuhi, who is also affiliate staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

The review was published online June 8 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Wreaks CNS havoc

It has become “increasingly evident” that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurologic manifestations, including anosmia, seizures, stroke, confusion, encephalopathy, and total paralysis, the authors wrote.

They noted that SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, which facilitates the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin. After ACE2 has bound to respiratory epithelial cells and then to epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-CoV-2 triggers the formation of a “cytokine storm.”

These cytokines, in turn, increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation, as well as triggering “hypercoagulation cascades,” which cause small and large blood clots that affect multiple organs.

If SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier, directly entering the brain, it can contribute to demyelination or neurodegeneration.

“We very thoroughly reviewed the literature published between Jan. 1 and May 1, 2020, about neurological issues [in COVID-19] and what I found interesting is that so many neurological things can happen due to a virus which is so small,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“This virus’ DNA has such limited information, and yet it can wreak havoc on our nervous system because it kicks off such a potent defense system in our body that damages our nervous system,” he said.

Three-stage classification

- Stage 1: The extent of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptors is limited to the nasal and gustatory epithelial cells, with the cytokine storm remaining “low and controlled.” During this stage, patients may experience smell or taste impairments, but often recover without any interventions.

- Stage 2: A “robust immune response” is activated by the virus, leading to inflammation in the blood vessels, increased hypercoagulability factors, and the formation of blood clots in cerebral arteries and veins. The patient may therefore experience either large or small strokes. Additional stage 2 symptoms include fatigue, hemiplegia, sensory loss, , tetraplegia, , or ataxia.

- Stage 3: The cytokine storm in the blood vessels is so severe that it causes an “explosive inflammatory response” and penetrates the blood-brain barrier, leading to the entry of cytokines, blood components, and viral particles into the brain parenchyma and causing neuronal cell death and encephalitis. This stage can be characterized by seizures, confusion, , coma, loss of consciousness, or death.

“Patients in stage 3 are more likely to have long-term consequences, because there is evidence that the virus particles have actually penetrated the brain, and we know that SARS-CoV-2 can remain dormant in neurons for many years,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“Studies of coronaviruses have shown a link between the viruses and the risk of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease even decades later,” he added.

“Based on several reports in recent months, between 36% to 55% of patients with COVID-19 that are hospitalized have some neurological symptoms, but if you don’t look for them, you won’t see them,” Dr. Fotuhi noted.

As a result, patients should be monitored over time after discharge, as they may develop cognitive dysfunction down the road.

Additionally, “it is imperative for patients [hospitalized with COVID-19] to get a baseline MRI before leaving the hospital so that we have a starting point for future evaluation and treatment,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“The good news is that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are treatable,” and “can improve with intensive training,” including lifestyle changes – such as a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, stress reduction, improved sleep, biofeedback, and brain rehabilitation, Dr. Fotuhi added.

Routine MRI not necessary

Kenneth Tyler, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, disagreed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should routinely receive an MRI.

“Whenever you are using a piece of equipment on patients who are COVID-19 infected, you risk introducing the infection to uninfected patients,” he said. Instead, “the indication is in patients who develop unexplained neurological manifestations – altered mental status or focal seizures, for example – because in those cases, you do need to understand whether there are underlying structural abnormalities,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the review.

Also commenting on the review, Vanja Douglas, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology, University of California, San Francisco, described the review as “thorough” and suggested it may “help us understand how to design observational studies to test whether the associations are due to severe respiratory illness or are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Dr. Douglas, who was not involved in the review, added that it is “helpful in giving us a sense of which neurologic syndromes have been observed in COVID-19 patients, and therefore which patients neurologists may want to screen more carefully during the pandemic.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Fotuhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One coauthor reported receiving consulting fees as a member of the scientific advisory board for Brainreader and reports royalties for expert witness consultation in conjunction with Neurevolution. Dr. Tyler and Dr. Douglas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center in McLean, Va., said.

“Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should have a neurological evaluation and ideally a brain MRI before leaving the hospital; and, if there are abnormalities, they should follow up with a neurologist in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Fotuhi, who is also affiliate staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

The review was published online June 8 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Wreaks CNS havoc

It has become “increasingly evident” that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurologic manifestations, including anosmia, seizures, stroke, confusion, encephalopathy, and total paralysis, the authors wrote.

They noted that SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, which facilitates the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin. After ACE2 has bound to respiratory epithelial cells and then to epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-CoV-2 triggers the formation of a “cytokine storm.”

These cytokines, in turn, increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation, as well as triggering “hypercoagulation cascades,” which cause small and large blood clots that affect multiple organs.

If SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier, directly entering the brain, it can contribute to demyelination or neurodegeneration.

“We very thoroughly reviewed the literature published between Jan. 1 and May 1, 2020, about neurological issues [in COVID-19] and what I found interesting is that so many neurological things can happen due to a virus which is so small,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“This virus’ DNA has such limited information, and yet it can wreak havoc on our nervous system because it kicks off such a potent defense system in our body that damages our nervous system,” he said.

Three-stage classification

- Stage 1: The extent of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptors is limited to the nasal and gustatory epithelial cells, with the cytokine storm remaining “low and controlled.” During this stage, patients may experience smell or taste impairments, but often recover without any interventions.

- Stage 2: A “robust immune response” is activated by the virus, leading to inflammation in the blood vessels, increased hypercoagulability factors, and the formation of blood clots in cerebral arteries and veins. The patient may therefore experience either large or small strokes. Additional stage 2 symptoms include fatigue, hemiplegia, sensory loss, , tetraplegia, , or ataxia.

- Stage 3: The cytokine storm in the blood vessels is so severe that it causes an “explosive inflammatory response” and penetrates the blood-brain barrier, leading to the entry of cytokines, blood components, and viral particles into the brain parenchyma and causing neuronal cell death and encephalitis. This stage can be characterized by seizures, confusion, , coma, loss of consciousness, or death.

“Patients in stage 3 are more likely to have long-term consequences, because there is evidence that the virus particles have actually penetrated the brain, and we know that SARS-CoV-2 can remain dormant in neurons for many years,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“Studies of coronaviruses have shown a link between the viruses and the risk of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease even decades later,” he added.

“Based on several reports in recent months, between 36% to 55% of patients with COVID-19 that are hospitalized have some neurological symptoms, but if you don’t look for them, you won’t see them,” Dr. Fotuhi noted.

As a result, patients should be monitored over time after discharge, as they may develop cognitive dysfunction down the road.

Additionally, “it is imperative for patients [hospitalized with COVID-19] to get a baseline MRI before leaving the hospital so that we have a starting point for future evaluation and treatment,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“The good news is that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are treatable,” and “can improve with intensive training,” including lifestyle changes – such as a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, stress reduction, improved sleep, biofeedback, and brain rehabilitation, Dr. Fotuhi added.

Routine MRI not necessary

Kenneth Tyler, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, disagreed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should routinely receive an MRI.

“Whenever you are using a piece of equipment on patients who are COVID-19 infected, you risk introducing the infection to uninfected patients,” he said. Instead, “the indication is in patients who develop unexplained neurological manifestations – altered mental status or focal seizures, for example – because in those cases, you do need to understand whether there are underlying structural abnormalities,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the review.

Also commenting on the review, Vanja Douglas, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology, University of California, San Francisco, described the review as “thorough” and suggested it may “help us understand how to design observational studies to test whether the associations are due to severe respiratory illness or are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Dr. Douglas, who was not involved in the review, added that it is “helpful in giving us a sense of which neurologic syndromes have been observed in COVID-19 patients, and therefore which patients neurologists may want to screen more carefully during the pandemic.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Fotuhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One coauthor reported receiving consulting fees as a member of the scientific advisory board for Brainreader and reports royalties for expert witness consultation in conjunction with Neurevolution. Dr. Tyler and Dr. Douglas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing pain expectations is key to enhanced recovery

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.

In addition, it is important to continue to collect data and study methods to treat pain and reduce opioid use perioperatively, Dr. Miller said. Some ongoing concerns include data surrounding the use of gabapentin and possible association with respiratory depression, he noted. Several meta-analyses have suggested that “gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin) when given as a single dose preoperatively are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain and opioid consumption at 24 hours,” said Dr. Miller. “When gabapentinoids are included in multimodal analgesic regimens, intraoperative opioids must be reduced, and increased vigilance for respiratory depression may be warranted, especially in elderly patients,” he said.

Overall, opioid-free anesthesia is both feasible and appropriate in certain patient populations, Dr. Miller concluded. “Implement your pathway and measure your outcomes with timely feedback so you can revise your protocol based on data,” he emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Miller disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, and serving as a board member for the Perioperative Quality Initiative and as a founding member of the Morpheus Consortium.

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.

In addition, it is important to continue to collect data and study methods to treat pain and reduce opioid use perioperatively, Dr. Miller said. Some ongoing concerns include data surrounding the use of gabapentin and possible association with respiratory depression, he noted. Several meta-analyses have suggested that “gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin) when given as a single dose preoperatively are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain and opioid consumption at 24 hours,” said Dr. Miller. “When gabapentinoids are included in multimodal analgesic regimens, intraoperative opioids must be reduced, and increased vigilance for respiratory depression may be warranted, especially in elderly patients,” he said.

Overall, opioid-free anesthesia is both feasible and appropriate in certain patient populations, Dr. Miller concluded. “Implement your pathway and measure your outcomes with timely feedback so you can revise your protocol based on data,” he emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Miller disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, and serving as a board member for the Perioperative Quality Initiative and as a founding member of the Morpheus Consortium.

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.

In addition, it is important to continue to collect data and study methods to treat pain and reduce opioid use perioperatively, Dr. Miller said. Some ongoing concerns include data surrounding the use of gabapentin and possible association with respiratory depression, he noted. Several meta-analyses have suggested that “gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin) when given as a single dose preoperatively are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain and opioid consumption at 24 hours,” said Dr. Miller. “When gabapentinoids are included in multimodal analgesic regimens, intraoperative opioids must be reduced, and increased vigilance for respiratory depression may be warranted, especially in elderly patients,” he said.

Overall, opioid-free anesthesia is both feasible and appropriate in certain patient populations, Dr. Miller concluded. “Implement your pathway and measure your outcomes with timely feedback so you can revise your protocol based on data,” he emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Miller disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, and serving as a board member for the Perioperative Quality Initiative and as a founding member of the Morpheus Consortium.

FROM MISS

Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine trials launching in July, expert says

The race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is unlike any other global research and development effort in modern medicine.

According to Paul A. Offit, MD, there are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for these vaccines, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has awarded $2.5 billion to five different pharmaceutical companies to make a vaccine.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.”

Some research groups are interested in developing a whole, killed virus like those used in the inactivated polio vaccine, and vaccines for hepatitis A virus and rabies, said Dr. Offit, who is a member of Accelerating COVID-19 Technical Innovations And Vaccines, a public-private partnership formed by the National Institutes of Health. Other groups are interested in making a live-attenuated vaccine like those for measles, mumps, and rubella. “Some are interested in using a vectored vaccine, where you take a virus that is relatively weak and doesn’t cause disease in people, like vesicular stomatitis virus, and then clone into that the gene that codes for this coronavirus spike protein, which is the way that we made the Ebola virus vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “Those approaches have all been used before, with success.”

Novel approaches are also being employed to make this vaccine, including using a replication-defective adenovirus. “That means that the virus can’t reproduce itself, but it can make proteins,” he explained. “There are some proteins that are made, but most aren’t. Therefore, the virus can’t reproduce itself. We’ll see whether or not that [approach] works, but it’s never been used before.”

Another approach is to inject messenger RNA that codes for the coronavirus spike protein, where that genetic material is translated into the spike protein. The other platform being evaluated is a DNA vaccine, in which “you give DNA which is coded for that spike protein, which is transcribed to messenger RNA and then is translated to other proteins.”

Typical vaccine development involves animal models to prove the concept, dose-ranging studies in humans, and progressively larger safety and immunogenicity studies in hundreds of thousands of people. Next come phase 3 studies, “where the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “These are large, prospective placebo-controlled trials to prove that the vaccine is safe. This is the only way whether you can prove or not a vaccine is effective.”

“Some companies may branch out on their own and do smaller studies than that,” he said. “We’ll see how this plays out. Keep your eyes open for that, because you really want to make sure you have a fairly large phase 3 trial. That’s the best way to show whether something works and whether it’s safe.”

The tried and true vaccines that emerge from the effort will not be FDA-licensed products. Rather, they will be approved products under the Emergency Use Authorization program. “Ever since the 1950s, every vaccine that has been used in the U.S. has been under the auspices of FDA licensure,” said Dr. Offit, who is also professor of pediatrics and the Maurice R. Hilleman professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s not going to be true here. The FDA is involved every step of the way but here they have a somewhat lighter touch.”

A few candidate vaccines are being mass-produced at risk, “meaning they’re being produced not knowing whether these vaccines are safe and effective yet or not,” he said. “But when they’re shown in a phase 3 trial to be safe and effective, you will have already produced it, and then it’s much easier to roll it out to the general public the minute you’ve shown that it works. This is what we did for the polio vaccine back in the 1950s. We mass-produced that vaccine at risk.”

Dr. Offit emphasized the importance of managing expectations once a COVID-19 vaccine gets approved for use. “Regarding safety, these vaccines will be tested in tens of thousands of people, not tens of millions of people, so although you can disprove a relatively uncommon side effect preapproval, you’re not going to disprove a rare side effect preapproval. You’re only going to know that post approval. I think we need to make people aware of that and to let them know that through groups like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we’re going to be monitoring these vaccines once they’re approved.”

Regarding efficacy, he continued, “we’re not going know about the rates of immunity initially; we’re only going to know about that after the vaccine [has been administered]. My guess is the protection is going to be short lived and incomplete. By short lived, I mean that protection would last for years but not decades. By incomplete, I mean that protection will be against moderate to severe disease, which is fine. You don’t need protection against all of the disease; it’s hard to do that with respiratory viruses. That means you can keep people out of the hospital, and you can keep them from dying. That’s the main goal.”

Dr. Offit closed his remarks by noting that much is at stake in this effort to develop a vaccine so quickly and that it “could go one of two ways. We could find that the vaccine is a lifesaver, and [that] we can finally end this awful pandemic. Or, if we cut corners and don’t prove that the vaccines are safe and effective as we should before they’re released, we could shake what is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country. Hopefully, it doesn’t play out that way.”

The race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is unlike any other global research and development effort in modern medicine.

According to Paul A. Offit, MD, there are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for these vaccines, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has awarded $2.5 billion to five different pharmaceutical companies to make a vaccine.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.”

Some research groups are interested in developing a whole, killed virus like those used in the inactivated polio vaccine, and vaccines for hepatitis A virus and rabies, said Dr. Offit, who is a member of Accelerating COVID-19 Technical Innovations And Vaccines, a public-private partnership formed by the National Institutes of Health. Other groups are interested in making a live-attenuated vaccine like those for measles, mumps, and rubella. “Some are interested in using a vectored vaccine, where you take a virus that is relatively weak and doesn’t cause disease in people, like vesicular stomatitis virus, and then clone into that the gene that codes for this coronavirus spike protein, which is the way that we made the Ebola virus vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “Those approaches have all been used before, with success.”

Novel approaches are also being employed to make this vaccine, including using a replication-defective adenovirus. “That means that the virus can’t reproduce itself, but it can make proteins,” he explained. “There are some proteins that are made, but most aren’t. Therefore, the virus can’t reproduce itself. We’ll see whether or not that [approach] works, but it’s never been used before.”

Another approach is to inject messenger RNA that codes for the coronavirus spike protein, where that genetic material is translated into the spike protein. The other platform being evaluated is a DNA vaccine, in which “you give DNA which is coded for that spike protein, which is transcribed to messenger RNA and then is translated to other proteins.”

Typical vaccine development involves animal models to prove the concept, dose-ranging studies in humans, and progressively larger safety and immunogenicity studies in hundreds of thousands of people. Next come phase 3 studies, “where the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “These are large, prospective placebo-controlled trials to prove that the vaccine is safe. This is the only way whether you can prove or not a vaccine is effective.”

“Some companies may branch out on their own and do smaller studies than that,” he said. “We’ll see how this plays out. Keep your eyes open for that, because you really want to make sure you have a fairly large phase 3 trial. That’s the best way to show whether something works and whether it’s safe.”

The tried and true vaccines that emerge from the effort will not be FDA-licensed products. Rather, they will be approved products under the Emergency Use Authorization program. “Ever since the 1950s, every vaccine that has been used in the U.S. has been under the auspices of FDA licensure,” said Dr. Offit, who is also professor of pediatrics and the Maurice R. Hilleman professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s not going to be true here. The FDA is involved every step of the way but here they have a somewhat lighter touch.”

A few candidate vaccines are being mass-produced at risk, “meaning they’re being produced not knowing whether these vaccines are safe and effective yet or not,” he said. “But when they’re shown in a phase 3 trial to be safe and effective, you will have already produced it, and then it’s much easier to roll it out to the general public the minute you’ve shown that it works. This is what we did for the polio vaccine back in the 1950s. We mass-produced that vaccine at risk.”

Dr. Offit emphasized the importance of managing expectations once a COVID-19 vaccine gets approved for use. “Regarding safety, these vaccines will be tested in tens of thousands of people, not tens of millions of people, so although you can disprove a relatively uncommon side effect preapproval, you’re not going to disprove a rare side effect preapproval. You’re only going to know that post approval. I think we need to make people aware of that and to let them know that through groups like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we’re going to be monitoring these vaccines once they’re approved.”

Regarding efficacy, he continued, “we’re not going know about the rates of immunity initially; we’re only going to know about that after the vaccine [has been administered]. My guess is the protection is going to be short lived and incomplete. By short lived, I mean that protection would last for years but not decades. By incomplete, I mean that protection will be against moderate to severe disease, which is fine. You don’t need protection against all of the disease; it’s hard to do that with respiratory viruses. That means you can keep people out of the hospital, and you can keep them from dying. That’s the main goal.”

Dr. Offit closed his remarks by noting that much is at stake in this effort to develop a vaccine so quickly and that it “could go one of two ways. We could find that the vaccine is a lifesaver, and [that] we can finally end this awful pandemic. Or, if we cut corners and don’t prove that the vaccines are safe and effective as we should before they’re released, we could shake what is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country. Hopefully, it doesn’t play out that way.”

The race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is unlike any other global research and development effort in modern medicine.

According to Paul A. Offit, MD, there are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for these vaccines, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has awarded $2.5 billion to five different pharmaceutical companies to make a vaccine.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.”

Some research groups are interested in developing a whole, killed virus like those used in the inactivated polio vaccine, and vaccines for hepatitis A virus and rabies, said Dr. Offit, who is a member of Accelerating COVID-19 Technical Innovations And Vaccines, a public-private partnership formed by the National Institutes of Health. Other groups are interested in making a live-attenuated vaccine like those for measles, mumps, and rubella. “Some are interested in using a vectored vaccine, where you take a virus that is relatively weak and doesn’t cause disease in people, like vesicular stomatitis virus, and then clone into that the gene that codes for this coronavirus spike protein, which is the way that we made the Ebola virus vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “Those approaches have all been used before, with success.”

Novel approaches are also being employed to make this vaccine, including using a replication-defective adenovirus. “That means that the virus can’t reproduce itself, but it can make proteins,” he explained. “There are some proteins that are made, but most aren’t. Therefore, the virus can’t reproduce itself. We’ll see whether or not that [approach] works, but it’s never been used before.”

Another approach is to inject messenger RNA that codes for the coronavirus spike protein, where that genetic material is translated into the spike protein. The other platform being evaluated is a DNA vaccine, in which “you give DNA which is coded for that spike protein, which is transcribed to messenger RNA and then is translated to other proteins.”

Typical vaccine development involves animal models to prove the concept, dose-ranging studies in humans, and progressively larger safety and immunogenicity studies in hundreds of thousands of people. Next come phase 3 studies, “where the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “These are large, prospective placebo-controlled trials to prove that the vaccine is safe. This is the only way whether you can prove or not a vaccine is effective.”

“Some companies may branch out on their own and do smaller studies than that,” he said. “We’ll see how this plays out. Keep your eyes open for that, because you really want to make sure you have a fairly large phase 3 trial. That’s the best way to show whether something works and whether it’s safe.”

The tried and true vaccines that emerge from the effort will not be FDA-licensed products. Rather, they will be approved products under the Emergency Use Authorization program. “Ever since the 1950s, every vaccine that has been used in the U.S. has been under the auspices of FDA licensure,” said Dr. Offit, who is also professor of pediatrics and the Maurice R. Hilleman professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s not going to be true here. The FDA is involved every step of the way but here they have a somewhat lighter touch.”

A few candidate vaccines are being mass-produced at risk, “meaning they’re being produced not knowing whether these vaccines are safe and effective yet or not,” he said. “But when they’re shown in a phase 3 trial to be safe and effective, you will have already produced it, and then it’s much easier to roll it out to the general public the minute you’ve shown that it works. This is what we did for the polio vaccine back in the 1950s. We mass-produced that vaccine at risk.”

Dr. Offit emphasized the importance of managing expectations once a COVID-19 vaccine gets approved for use. “Regarding safety, these vaccines will be tested in tens of thousands of people, not tens of millions of people, so although you can disprove a relatively uncommon side effect preapproval, you’re not going to disprove a rare side effect preapproval. You’re only going to know that post approval. I think we need to make people aware of that and to let them know that through groups like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we’re going to be monitoring these vaccines once they’re approved.”

Regarding efficacy, he continued, “we’re not going know about the rates of immunity initially; we’re only going to know about that after the vaccine [has been administered]. My guess is the protection is going to be short lived and incomplete. By short lived, I mean that protection would last for years but not decades. By incomplete, I mean that protection will be against moderate to severe disease, which is fine. You don’t need protection against all of the disease; it’s hard to do that with respiratory viruses. That means you can keep people out of the hospital, and you can keep them from dying. That’s the main goal.”

Dr. Offit closed his remarks by noting that much is at stake in this effort to develop a vaccine so quickly and that it “could go one of two ways. We could find that the vaccine is a lifesaver, and [that] we can finally end this awful pandemic. Or, if we cut corners and don’t prove that the vaccines are safe and effective as we should before they’re released, we could shake what is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country. Hopefully, it doesn’t play out that way.”

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY 2020

Pursue multimodal pain management in patients taking opioids

For surgical patients on chronic opioid therapy, , according to Stephanie B. Jones, MD, professor and chair of anesthesiology at Albany Medical College, New York.

“[With] any patient coming in for any sort of surgery, you should be considering multimodal pain management. That applies to the opioid use disorder patient as well,” Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The challenge of opioid-tolerant patients or opioid abuse patients is twofold – tolerance and hyperalgesia,” Dr. Jones said. Patient tolerance changes how patients perceive pain and respond to medication. Clinicians need to consider the “opioid debt,” defined as the daily amount of opioid medication required by opioid-dependent patients to maintain their usual prehospitalization opioid levels, she explained. Also consider hyperalgesia, a change in pain perception “resulting in an increase in pain sensitivity to painful stimuli, thereby decreasing the analgesic effects of opioids,” Dr. Jones added.

A multimodal approach to pain management in patients on chronic opioids can include some opioids as appropriate, Dr. Jones said. Modulation of pain may draw on epidurals and nerve blocks, as well as managing CNS perception of pain through opioids or acetaminophen, and also using systemic options such as alpha-2 agonists and tramadol, she said.

Studies have shown that opioid abuse or dependence were associated with increased readmission rates, length of stay, and health care costs in surgery patients, said Dr. Jones. However, switching opioids and managing equivalents is complex, and “equianalgesic conversions serve only as a general guide to estimate opioid dose equivalents,” according to UpToDate’s, “Management of acute pain in the patient chronically using opioids,” she said.

Dr. Jones also addressed the issue of using hospitalization as an opportunity to help patients with untreated opioid use disorder. Medication-assisted options include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“One problem with methadone is that there are a lot of medications interactions,” she said. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being long-lasting, and is formulated with naloxone which deters injection. “Because it is a partial agonist, there is a lower risk of overdose and sedation,” and it has fewer medication interactions. However, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe it and there is some risk of medication diversion, she said.

Naltrexone is newer to the role of treating opioid use disorder, Dr. Jones said. “It can cause acute withdrawal because it is a full opioid antagonist,” she noted. However, naltrexone itself causes no withdrawal if stopped, and no respiratory depression or sedation, said Dr. Jones.

“Utilize addiction services in your hospital if you suspect a patient may be at risk for opioid use disorder,” and engage these services early, she emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones had no financial conflicts to disclose.

For surgical patients on chronic opioid therapy, , according to Stephanie B. Jones, MD, professor and chair of anesthesiology at Albany Medical College, New York.

“[With] any patient coming in for any sort of surgery, you should be considering multimodal pain management. That applies to the opioid use disorder patient as well,” Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The challenge of opioid-tolerant patients or opioid abuse patients is twofold – tolerance and hyperalgesia,” Dr. Jones said. Patient tolerance changes how patients perceive pain and respond to medication. Clinicians need to consider the “opioid debt,” defined as the daily amount of opioid medication required by opioid-dependent patients to maintain their usual prehospitalization opioid levels, she explained. Also consider hyperalgesia, a change in pain perception “resulting in an increase in pain sensitivity to painful stimuli, thereby decreasing the analgesic effects of opioids,” Dr. Jones added.

A multimodal approach to pain management in patients on chronic opioids can include some opioids as appropriate, Dr. Jones said. Modulation of pain may draw on epidurals and nerve blocks, as well as managing CNS perception of pain through opioids or acetaminophen, and also using systemic options such as alpha-2 agonists and tramadol, she said.

Studies have shown that opioid abuse or dependence were associated with increased readmission rates, length of stay, and health care costs in surgery patients, said Dr. Jones. However, switching opioids and managing equivalents is complex, and “equianalgesic conversions serve only as a general guide to estimate opioid dose equivalents,” according to UpToDate’s, “Management of acute pain in the patient chronically using opioids,” she said.

Dr. Jones also addressed the issue of using hospitalization as an opportunity to help patients with untreated opioid use disorder. Medication-assisted options include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“One problem with methadone is that there are a lot of medications interactions,” she said. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being long-lasting, and is formulated with naloxone which deters injection. “Because it is a partial agonist, there is a lower risk of overdose and sedation,” and it has fewer medication interactions. However, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe it and there is some risk of medication diversion, she said.

Naltrexone is newer to the role of treating opioid use disorder, Dr. Jones said. “It can cause acute withdrawal because it is a full opioid antagonist,” she noted. However, naltrexone itself causes no withdrawal if stopped, and no respiratory depression or sedation, said Dr. Jones.

“Utilize addiction services in your hospital if you suspect a patient may be at risk for opioid use disorder,” and engage these services early, she emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones had no financial conflicts to disclose.

For surgical patients on chronic opioid therapy, , according to Stephanie B. Jones, MD, professor and chair of anesthesiology at Albany Medical College, New York.

“[With] any patient coming in for any sort of surgery, you should be considering multimodal pain management. That applies to the opioid use disorder patient as well,” Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The challenge of opioid-tolerant patients or opioid abuse patients is twofold – tolerance and hyperalgesia,” Dr. Jones said. Patient tolerance changes how patients perceive pain and respond to medication. Clinicians need to consider the “opioid debt,” defined as the daily amount of opioid medication required by opioid-dependent patients to maintain their usual prehospitalization opioid levels, she explained. Also consider hyperalgesia, a change in pain perception “resulting in an increase in pain sensitivity to painful stimuli, thereby decreasing the analgesic effects of opioids,” Dr. Jones added.

A multimodal approach to pain management in patients on chronic opioids can include some opioids as appropriate, Dr. Jones said. Modulation of pain may draw on epidurals and nerve blocks, as well as managing CNS perception of pain through opioids or acetaminophen, and also using systemic options such as alpha-2 agonists and tramadol, she said.

Studies have shown that opioid abuse or dependence were associated with increased readmission rates, length of stay, and health care costs in surgery patients, said Dr. Jones. However, switching opioids and managing equivalents is complex, and “equianalgesic conversions serve only as a general guide to estimate opioid dose equivalents,” according to UpToDate’s, “Management of acute pain in the patient chronically using opioids,” she said.

Dr. Jones also addressed the issue of using hospitalization as an opportunity to help patients with untreated opioid use disorder. Medication-assisted options include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“One problem with methadone is that there are a lot of medications interactions,” she said. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being long-lasting, and is formulated with naloxone which deters injection. “Because it is a partial agonist, there is a lower risk of overdose and sedation,” and it has fewer medication interactions. However, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe it and there is some risk of medication diversion, she said.

Naltrexone is newer to the role of treating opioid use disorder, Dr. Jones said. “It can cause acute withdrawal because it is a full opioid antagonist,” she noted. However, naltrexone itself causes no withdrawal if stopped, and no respiratory depression or sedation, said Dr. Jones.

“Utilize addiction services in your hospital if you suspect a patient may be at risk for opioid use disorder,” and engage these services early, she emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM MISS

Treatment developments in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (oHCM)

Background: oHCM is characterized by mutations in sarcomeric proteins. Mavacamten is a small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin, commonly affected in oHCM.

Study design: Open-label, nonrandomized phase 2 trial.

Setting: Five academic medical centers.

Synopsis: A total of 21 patients with oHCM were randomized to cohort A, high-dose mavacamten without additional therapy (beta-blockers, CCBs), or cohort B, low-dose mavacamten plus additional medical therapy. The LVOT gradient at 12 weeks improved in both cohorts: Cohort A had a mean change of –89.5 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –138.3 to –40.7; P = .008) and cohort B –25.0 mm Hg (95% CI, –47.1 to –3.0, P = .020).

Bottom line: This phase 2 trial provides proof of concept and identified a plasma concentration of mavacamten needed to decrease the LVOT significantly. Phase 3 trials hold significant promise.

Citation: Heitner SB et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 30. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016.

Dr. Blount is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: oHCM is characterized by mutations in sarcomeric proteins. Mavacamten is a small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin, commonly affected in oHCM.

Study design: Open-label, nonrandomized phase 2 trial.

Setting: Five academic medical centers.

Synopsis: A total of 21 patients with oHCM were randomized to cohort A, high-dose mavacamten without additional therapy (beta-blockers, CCBs), or cohort B, low-dose mavacamten plus additional medical therapy. The LVOT gradient at 12 weeks improved in both cohorts: Cohort A had a mean change of –89.5 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –138.3 to –40.7; P = .008) and cohort B –25.0 mm Hg (95% CI, –47.1 to –3.0, P = .020).

Bottom line: This phase 2 trial provides proof of concept and identified a plasma concentration of mavacamten needed to decrease the LVOT significantly. Phase 3 trials hold significant promise.

Citation: Heitner SB et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 30. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016.

Dr. Blount is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: oHCM is characterized by mutations in sarcomeric proteins. Mavacamten is a small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin, commonly affected in oHCM.

Study design: Open-label, nonrandomized phase 2 trial.

Setting: Five academic medical centers.

Synopsis: A total of 21 patients with oHCM were randomized to cohort A, high-dose mavacamten without additional therapy (beta-blockers, CCBs), or cohort B, low-dose mavacamten plus additional medical therapy. The LVOT gradient at 12 weeks improved in both cohorts: Cohort A had a mean change of –89.5 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –138.3 to –40.7; P = .008) and cohort B –25.0 mm Hg (95% CI, –47.1 to –3.0, P = .020).

Bottom line: This phase 2 trial provides proof of concept and identified a plasma concentration of mavacamten needed to decrease the LVOT significantly. Phase 3 trials hold significant promise.

Citation: Heitner SB et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 30. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016.

Dr. Blount is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Manage the pandemic with a multidisciplinary coalition

Implement a 6-P framework

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

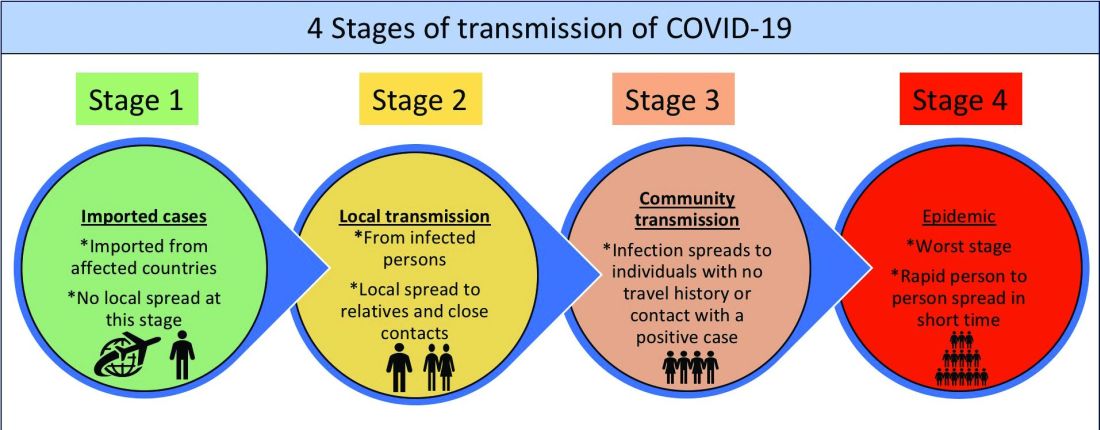

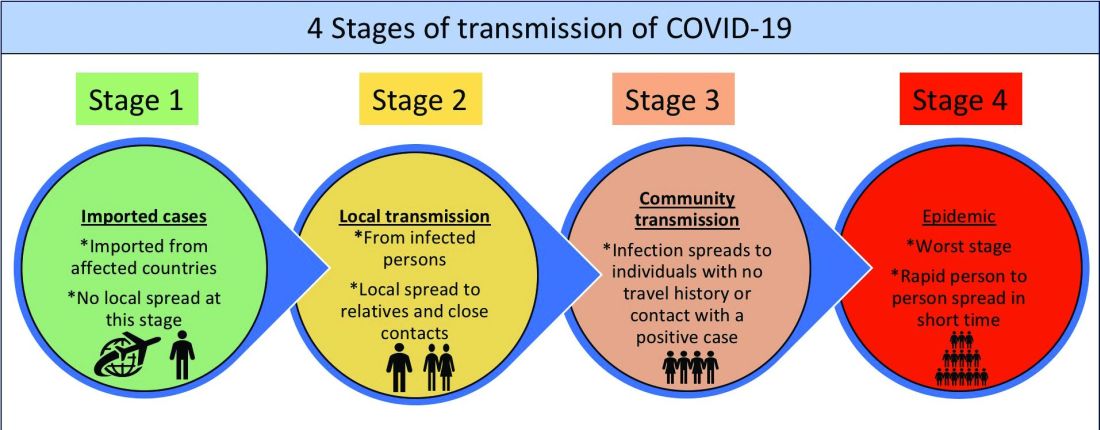

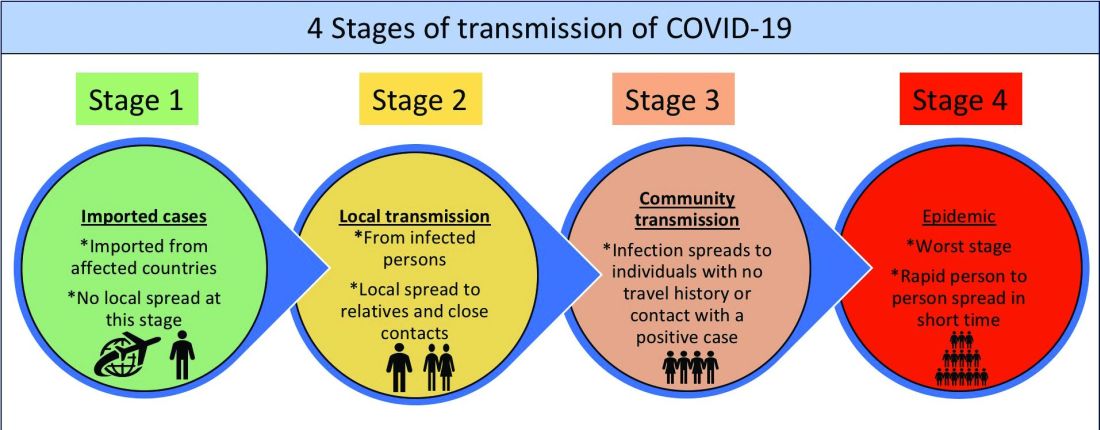

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.