User login

Higher 10-day mortality of lower-acuity patients during times of increased ED crowding

Background: Studies have assessed mortality effect from ED crowding on high-acuity patients, but limited evidence exists for how this affects lower-acuity patients who are discharged home.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Emergency department, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Sweden.

Synopsis: During 2009-2016, 705,813 encounters seen in the ED, triaged to lower-acuity levels 3-5 and discharged without further hospitalization needs were identified. A total of 623 patients died within 10 days of the initial ED visit (0.09%). The study evaluated the association of 10-day mortality with mean ED length of stay and ED-occupancy ratio.

The study demonstrated an increased 10-day mortality for mean ED length of stay of 8 hours or more vs. less than 2 hours (adjusted odds ratio, 5.86; 95% CI, 2.15-15.94). It also found an increased mortality rate for occupancy ratio quartiles with an aOR for quartiles 2, 3, and 4 vs. quartile 1 of 1.48 (95% CI, 1.14-1.92), 1.63 (95% CI, 1.24-2.14), and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.15-2.03), respectively.

While this suggests increased 10-day mortality in this patient population, additional studies should be conducted to determine if this risk is caused by ED crowding and length of stay or by current limitations in triage scoring.

Bottom line: There is an increased 10-day mortality rate for lower-acuity triaged patients who were discharged from the ED without hospitalization experiencing increased ED length of stay and during times of ED crowding.

Citation: Berg L et al. Associations between crowding and 10-day mortality among patients allocated lower triage acuity levels without need of acute hospital care on departure from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Sep;74(3):345-56.

Dr. Merando is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Background: Studies have assessed mortality effect from ED crowding on high-acuity patients, but limited evidence exists for how this affects lower-acuity patients who are discharged home.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Emergency department, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Sweden.

Synopsis: During 2009-2016, 705,813 encounters seen in the ED, triaged to lower-acuity levels 3-5 and discharged without further hospitalization needs were identified. A total of 623 patients died within 10 days of the initial ED visit (0.09%). The study evaluated the association of 10-day mortality with mean ED length of stay and ED-occupancy ratio.

The study demonstrated an increased 10-day mortality for mean ED length of stay of 8 hours or more vs. less than 2 hours (adjusted odds ratio, 5.86; 95% CI, 2.15-15.94). It also found an increased mortality rate for occupancy ratio quartiles with an aOR for quartiles 2, 3, and 4 vs. quartile 1 of 1.48 (95% CI, 1.14-1.92), 1.63 (95% CI, 1.24-2.14), and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.15-2.03), respectively.

While this suggests increased 10-day mortality in this patient population, additional studies should be conducted to determine if this risk is caused by ED crowding and length of stay or by current limitations in triage scoring.

Bottom line: There is an increased 10-day mortality rate for lower-acuity triaged patients who were discharged from the ED without hospitalization experiencing increased ED length of stay and during times of ED crowding.

Citation: Berg L et al. Associations between crowding and 10-day mortality among patients allocated lower triage acuity levels without need of acute hospital care on departure from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Sep;74(3):345-56.

Dr. Merando is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Background: Studies have assessed mortality effect from ED crowding on high-acuity patients, but limited evidence exists for how this affects lower-acuity patients who are discharged home.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Emergency department, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Sweden.

Synopsis: During 2009-2016, 705,813 encounters seen in the ED, triaged to lower-acuity levels 3-5 and discharged without further hospitalization needs were identified. A total of 623 patients died within 10 days of the initial ED visit (0.09%). The study evaluated the association of 10-day mortality with mean ED length of stay and ED-occupancy ratio.

The study demonstrated an increased 10-day mortality for mean ED length of stay of 8 hours or more vs. less than 2 hours (adjusted odds ratio, 5.86; 95% CI, 2.15-15.94). It also found an increased mortality rate for occupancy ratio quartiles with an aOR for quartiles 2, 3, and 4 vs. quartile 1 of 1.48 (95% CI, 1.14-1.92), 1.63 (95% CI, 1.24-2.14), and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.15-2.03), respectively.

While this suggests increased 10-day mortality in this patient population, additional studies should be conducted to determine if this risk is caused by ED crowding and length of stay or by current limitations in triage scoring.

Bottom line: There is an increased 10-day mortality rate for lower-acuity triaged patients who were discharged from the ED without hospitalization experiencing increased ED length of stay and during times of ED crowding.

Citation: Berg L et al. Associations between crowding and 10-day mortality among patients allocated lower triage acuity levels without need of acute hospital care on departure from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Sep;74(3):345-56.

Dr. Merando is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Infant’s COVID-19–related myocardial injury reversed

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

FROM JACC CASE REPORTS

Key clinical point: Children presenting with COVID-19 should be tested for heart failure.

Major finding: A 2-month-old infant with COVID-19 had acute but reversible myocardial injury.

Study details: Single case report.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharma, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Mortality higher in older adults hospitalized for IBD

Adults older than 65 years with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) had significantly higher rates of inpatient mortality, compared with those younger than 65 years, independent of factors including disease severity, based on data from more than 200,000 hospital admissions.

Older adults use a disproportionate share of health care resources, but data on outcomes among hospitalized older adults with gastrointestinal illness are limited, Jeffrey Schwartz, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

“In particular, there remains a significant concern that elderly patients are more susceptible to the development of opportunistic infections and malignancy in the setting of biological therapy, which has evolved into the standard of care for IBD over the past 10 years,” they wrote.

In their study, the researchers identified 162,800 hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease and 96,450 admissions for ulcerative colitis. Of these, 20% and 30%, respectively, were older than 65 years, which the researchers designated as the geriatric group.

In a multivariate analysis, age older than 65 years was significantly associated with increased mortality in both Crohn’s disease (odds ratio, 3.47; 95% confidence interval, 2.72-4.44; P < .001) and ulcerative colitis (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 2.16-3.49; P < .001). The association was independent of factors included comorbidities, admission type, hospital type, inpatient surgery, and IBD subtype.

The most frequent cause of death in both groups across all ages and disease subtypes was infections (approximately 80% for all groups). The total hospital length of stay was significantly longer for geriatric patients, compared with younger patients with Crohn’s disease, in multivariate analysis (average increase, 0.19 days; P = .009). The total charges also were significantly higher among geriatric Crohn’s disease patients, compared with younger patients (average increase, $2,467; P = .012). No significant differences in hospital stay or total charges appeared between geriatric and younger patients with ulcerative colitis.

The study findings were limited by several factors such as the inclusion of older patients with IBD who were hospitalized for other reasons and by the potential for increased mortality because of comorbidities among elderly patients, the researchers noted. However, the findings support the limited data from similar previous studies and showed greater inpatient mortality for older adults with IBD, compared with hospital inpatients overall.

“Given the high prevalence of IBD patients that require inpatient admission, as well as the rapidly aging nature of the U.S. population, further studies are needed targeting geriatric patients with UC [ulcerative colitis] and CD [Crohn’s disease] to improve their overall management and quality of care to determine if this mortality risk can be reduced,” they concluded.

Tune in to risks in older adults

The study is important because the percentage of the population older than 65 years has been increasing; “at the same time, we are seeing more elderly patients being newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis,” said Russell D. Cohen, MD, of the University of Chicago, in an interview. “These patients are more vulnerable to complications of the diseases, such as infections, as well as complications from the medications used to treat these diseases.” However, older adults are often excluded from clinical trials and even from many observational studies in IBD, he noted.

“We have known from past studies that infections such as sepsis are a leading cause of death in our IBD patients,” said Dr. Cohen. “It is also understandable that those patients who have had complicated courses and those with other comorbidities have a higher mortality rate. However, what was surprising in the current study is that, even when the authors controlled for these factors, the geriatric patients still had two and three-quarters to three and a half times the mortality than those who were younger.”

The take-home message for clinicians is that “the geriatric patient with IBD is at a much higher rate for inpatient mortality, most commonly from infectious complications, than younger patients,” Dr. Cohen emphasized. “Quicker attention to what may seem minor but could become a potentially life-threatening infection is imperative. Caution with the use of multiple immune suppressing medications in older patients is paramount, as is timely surgical intervention in IBD patients in whom medications simply are not working.”

Focus research on infection prevention, cost burden

“More research should be directed at finding out whether these deadly infections could be prevented, perhaps by preventative ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics in the elderly patients, especially those on multiple immunosuppressive agents,” said Dr. Cohen. “In addition, research into the undue cost burden that these patients place on our health care system and counter that with better access to the newer, safer biological therapies [most of which Medicare does not cover] rather than corticosteroids.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cohen disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Schwartz J et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov 23. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001458.

Adults older than 65 years with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) had significantly higher rates of inpatient mortality, compared with those younger than 65 years, independent of factors including disease severity, based on data from more than 200,000 hospital admissions.

Older adults use a disproportionate share of health care resources, but data on outcomes among hospitalized older adults with gastrointestinal illness are limited, Jeffrey Schwartz, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

“In particular, there remains a significant concern that elderly patients are more susceptible to the development of opportunistic infections and malignancy in the setting of biological therapy, which has evolved into the standard of care for IBD over the past 10 years,” they wrote.

In their study, the researchers identified 162,800 hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease and 96,450 admissions for ulcerative colitis. Of these, 20% and 30%, respectively, were older than 65 years, which the researchers designated as the geriatric group.

In a multivariate analysis, age older than 65 years was significantly associated with increased mortality in both Crohn’s disease (odds ratio, 3.47; 95% confidence interval, 2.72-4.44; P < .001) and ulcerative colitis (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 2.16-3.49; P < .001). The association was independent of factors included comorbidities, admission type, hospital type, inpatient surgery, and IBD subtype.

The most frequent cause of death in both groups across all ages and disease subtypes was infections (approximately 80% for all groups). The total hospital length of stay was significantly longer for geriatric patients, compared with younger patients with Crohn’s disease, in multivariate analysis (average increase, 0.19 days; P = .009). The total charges also were significantly higher among geriatric Crohn’s disease patients, compared with younger patients (average increase, $2,467; P = .012). No significant differences in hospital stay or total charges appeared between geriatric and younger patients with ulcerative colitis.

The study findings were limited by several factors such as the inclusion of older patients with IBD who were hospitalized for other reasons and by the potential for increased mortality because of comorbidities among elderly patients, the researchers noted. However, the findings support the limited data from similar previous studies and showed greater inpatient mortality for older adults with IBD, compared with hospital inpatients overall.

“Given the high prevalence of IBD patients that require inpatient admission, as well as the rapidly aging nature of the U.S. population, further studies are needed targeting geriatric patients with UC [ulcerative colitis] and CD [Crohn’s disease] to improve their overall management and quality of care to determine if this mortality risk can be reduced,” they concluded.

Tune in to risks in older adults

The study is important because the percentage of the population older than 65 years has been increasing; “at the same time, we are seeing more elderly patients being newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis,” said Russell D. Cohen, MD, of the University of Chicago, in an interview. “These patients are more vulnerable to complications of the diseases, such as infections, as well as complications from the medications used to treat these diseases.” However, older adults are often excluded from clinical trials and even from many observational studies in IBD, he noted.

“We have known from past studies that infections such as sepsis are a leading cause of death in our IBD patients,” said Dr. Cohen. “It is also understandable that those patients who have had complicated courses and those with other comorbidities have a higher mortality rate. However, what was surprising in the current study is that, even when the authors controlled for these factors, the geriatric patients still had two and three-quarters to three and a half times the mortality than those who were younger.”

The take-home message for clinicians is that “the geriatric patient with IBD is at a much higher rate for inpatient mortality, most commonly from infectious complications, than younger patients,” Dr. Cohen emphasized. “Quicker attention to what may seem minor but could become a potentially life-threatening infection is imperative. Caution with the use of multiple immune suppressing medications in older patients is paramount, as is timely surgical intervention in IBD patients in whom medications simply are not working.”

Focus research on infection prevention, cost burden

“More research should be directed at finding out whether these deadly infections could be prevented, perhaps by preventative ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics in the elderly patients, especially those on multiple immunosuppressive agents,” said Dr. Cohen. “In addition, research into the undue cost burden that these patients place on our health care system and counter that with better access to the newer, safer biological therapies [most of which Medicare does not cover] rather than corticosteroids.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cohen disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Schwartz J et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov 23. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001458.

Adults older than 65 years with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) had significantly higher rates of inpatient mortality, compared with those younger than 65 years, independent of factors including disease severity, based on data from more than 200,000 hospital admissions.

Older adults use a disproportionate share of health care resources, but data on outcomes among hospitalized older adults with gastrointestinal illness are limited, Jeffrey Schwartz, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

“In particular, there remains a significant concern that elderly patients are more susceptible to the development of opportunistic infections and malignancy in the setting of biological therapy, which has evolved into the standard of care for IBD over the past 10 years,” they wrote.

In their study, the researchers identified 162,800 hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease and 96,450 admissions for ulcerative colitis. Of these, 20% and 30%, respectively, were older than 65 years, which the researchers designated as the geriatric group.

In a multivariate analysis, age older than 65 years was significantly associated with increased mortality in both Crohn’s disease (odds ratio, 3.47; 95% confidence interval, 2.72-4.44; P < .001) and ulcerative colitis (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 2.16-3.49; P < .001). The association was independent of factors included comorbidities, admission type, hospital type, inpatient surgery, and IBD subtype.

The most frequent cause of death in both groups across all ages and disease subtypes was infections (approximately 80% for all groups). The total hospital length of stay was significantly longer for geriatric patients, compared with younger patients with Crohn’s disease, in multivariate analysis (average increase, 0.19 days; P = .009). The total charges also were significantly higher among geriatric Crohn’s disease patients, compared with younger patients (average increase, $2,467; P = .012). No significant differences in hospital stay or total charges appeared between geriatric and younger patients with ulcerative colitis.

The study findings were limited by several factors such as the inclusion of older patients with IBD who were hospitalized for other reasons and by the potential for increased mortality because of comorbidities among elderly patients, the researchers noted. However, the findings support the limited data from similar previous studies and showed greater inpatient mortality for older adults with IBD, compared with hospital inpatients overall.

“Given the high prevalence of IBD patients that require inpatient admission, as well as the rapidly aging nature of the U.S. population, further studies are needed targeting geriatric patients with UC [ulcerative colitis] and CD [Crohn’s disease] to improve their overall management and quality of care to determine if this mortality risk can be reduced,” they concluded.

Tune in to risks in older adults

The study is important because the percentage of the population older than 65 years has been increasing; “at the same time, we are seeing more elderly patients being newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis,” said Russell D. Cohen, MD, of the University of Chicago, in an interview. “These patients are more vulnerable to complications of the diseases, such as infections, as well as complications from the medications used to treat these diseases.” However, older adults are often excluded from clinical trials and even from many observational studies in IBD, he noted.

“We have known from past studies that infections such as sepsis are a leading cause of death in our IBD patients,” said Dr. Cohen. “It is also understandable that those patients who have had complicated courses and those with other comorbidities have a higher mortality rate. However, what was surprising in the current study is that, even when the authors controlled for these factors, the geriatric patients still had two and three-quarters to three and a half times the mortality than those who were younger.”

The take-home message for clinicians is that “the geriatric patient with IBD is at a much higher rate for inpatient mortality, most commonly from infectious complications, than younger patients,” Dr. Cohen emphasized. “Quicker attention to what may seem minor but could become a potentially life-threatening infection is imperative. Caution with the use of multiple immune suppressing medications in older patients is paramount, as is timely surgical intervention in IBD patients in whom medications simply are not working.”

Focus research on infection prevention, cost burden

“More research should be directed at finding out whether these deadly infections could be prevented, perhaps by preventative ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics in the elderly patients, especially those on multiple immunosuppressive agents,” said Dr. Cohen. “In addition, research into the undue cost burden that these patients place on our health care system and counter that with better access to the newer, safer biological therapies [most of which Medicare does not cover] rather than corticosteroids.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cohen disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Schwartz J et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov 23. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001458.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Risk associated with perioperative atrial fibrillation

Background: New-onset POAF occurs with 10% of noncardiac surgery and 15%-42% of cardiac surgery. POAF is believed to be self-limiting and most patients revert to sinus rhythm before hospital discharge. Previous studies on this topic are both limited and conflicting, but several suggest there is an association of stroke and mortality with POAF.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were used for early outcomes and hazard ratios were used for long-term outcomes.

Setting: Prospective and retrospective cohort studies.

Synopsis: A total of 35 carefully selected studies were analyzed for a total of 2,458,010 patients. Outcomes of interest were early stroke or mortality within 30 days of surgery and long-term stroke or mortality after 30 days. The reference group was patients without POAF at baseline. Subgroup analysis included separating patients into cardiac surgery and noncardiac surgery.

New-onset POAF was associated with increased risk of early stroke (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.47-1.80) and early mortality (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11-1.88). POAF also was associated with risk for long-term stroke (hazard ratio, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.07-1.77) and long-term mortality (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.49). The risk of long-term stroke from new-onset POAF was highest among patients who received noncardiac surgery.

Despite identifying high-quality studies with thoughtful analysis, some data had the potential for publication bias. The representative sample did not report paroxysmal vs. persistent atrial fibrillation separately. Furthermore, the study had the potential to be confounded by detection bias of preexisting atrial fibrillation.

Bottom line: New-onset POAF is associated with early and long-term risk of stroke and mortality. Subsequent strategies to reduce this risk have yet to be determined.

Citation: Lin MH et al. Perioperative/postoperative atrial fibrillation and risk of subsequent stroke and/or mortality. Stroke. 2019 May;50:1364-71.

Dr. Mayer is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Background: New-onset POAF occurs with 10% of noncardiac surgery and 15%-42% of cardiac surgery. POAF is believed to be self-limiting and most patients revert to sinus rhythm before hospital discharge. Previous studies on this topic are both limited and conflicting, but several suggest there is an association of stroke and mortality with POAF.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were used for early outcomes and hazard ratios were used for long-term outcomes.

Setting: Prospective and retrospective cohort studies.

Synopsis: A total of 35 carefully selected studies were analyzed for a total of 2,458,010 patients. Outcomes of interest were early stroke or mortality within 30 days of surgery and long-term stroke or mortality after 30 days. The reference group was patients without POAF at baseline. Subgroup analysis included separating patients into cardiac surgery and noncardiac surgery.

New-onset POAF was associated with increased risk of early stroke (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.47-1.80) and early mortality (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11-1.88). POAF also was associated with risk for long-term stroke (hazard ratio, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.07-1.77) and long-term mortality (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.49). The risk of long-term stroke from new-onset POAF was highest among patients who received noncardiac surgery.

Despite identifying high-quality studies with thoughtful analysis, some data had the potential for publication bias. The representative sample did not report paroxysmal vs. persistent atrial fibrillation separately. Furthermore, the study had the potential to be confounded by detection bias of preexisting atrial fibrillation.

Bottom line: New-onset POAF is associated with early and long-term risk of stroke and mortality. Subsequent strategies to reduce this risk have yet to be determined.

Citation: Lin MH et al. Perioperative/postoperative atrial fibrillation and risk of subsequent stroke and/or mortality. Stroke. 2019 May;50:1364-71.

Dr. Mayer is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Background: New-onset POAF occurs with 10% of noncardiac surgery and 15%-42% of cardiac surgery. POAF is believed to be self-limiting and most patients revert to sinus rhythm before hospital discharge. Previous studies on this topic are both limited and conflicting, but several suggest there is an association of stroke and mortality with POAF.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were used for early outcomes and hazard ratios were used for long-term outcomes.

Setting: Prospective and retrospective cohort studies.

Synopsis: A total of 35 carefully selected studies were analyzed for a total of 2,458,010 patients. Outcomes of interest were early stroke or mortality within 30 days of surgery and long-term stroke or mortality after 30 days. The reference group was patients without POAF at baseline. Subgroup analysis included separating patients into cardiac surgery and noncardiac surgery.

New-onset POAF was associated with increased risk of early stroke (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.47-1.80) and early mortality (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11-1.88). POAF also was associated with risk for long-term stroke (hazard ratio, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.07-1.77) and long-term mortality (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.49). The risk of long-term stroke from new-onset POAF was highest among patients who received noncardiac surgery.

Despite identifying high-quality studies with thoughtful analysis, some data had the potential for publication bias. The representative sample did not report paroxysmal vs. persistent atrial fibrillation separately. Furthermore, the study had the potential to be confounded by detection bias of preexisting atrial fibrillation.

Bottom line: New-onset POAF is associated with early and long-term risk of stroke and mortality. Subsequent strategies to reduce this risk have yet to be determined.

Citation: Lin MH et al. Perioperative/postoperative atrial fibrillation and risk of subsequent stroke and/or mortality. Stroke. 2019 May;50:1364-71.

Dr. Mayer is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

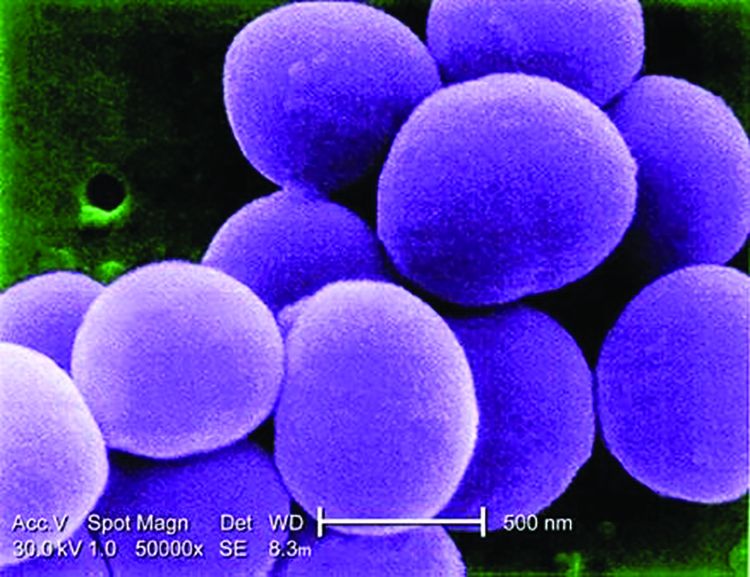

Two consecutive negative FUBC results clear S. aureus bacteremia

reported Caitlin Cardenas-Comfort, MD, of the section of pediatric infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues.

In a retrospective cohort study of 122 pediatric patients with documented Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) that were hospitalized at one of three hospitals in the Texas Children’s Hospital network in Houston, Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues sought to determine whether specific recommendations can be made on the number of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) needed to document clearance of SAB. Patients included in the study were under 18 years of age and had confirmed diagnosis of SAB between Jan. 1, and Dec. 31, 2018.

Most cases of bacteremia resolve in under 48 hours

In the majority of cases, patients had bacteremia for less than 48 hours and few to no complications. Only 16% of patients experienced bacteremia lasting 3 or more days, and they had either central line-associated bloodstream infection, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis. In such cases, “patients with endovascular and closed-space infections are at an increased risk of persistent bacteremia,” warranting more conservative monitoring and follow-up, cautioned the researchers.

Although Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues did note an association between the duration of bacteremia and a diagnosis of infectious disease, increased risk for persistent SAB did not appear to be tied to an underlying medical condition, including immunosuppression.

Fewer than 5% of patients with SAB had intermittent positive cultures and fewer than 1% had repeat positive cultures following two negative FUBC results. For those patients with intermittent positive cultures, the risk of being diagnosed with endocarditis or osteomyelitis is more than double. The authors suggested that “source control could be a critical variable” increasing the risk for intermittent positive cultures, noting that surgical debridement occurred more than 24 hours following initial blood draw for every patient in the osteomyelitis group. In contrast, of those who had consistently negative FUBC results, only 2 of 33 (6%) had debridement in the same period, and only 6 of 33 (18%) required more than one debridement.

Children are less likely to have intermittent positive cultures

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues also observed that intermittent positive cultures may appear less frequently in children than adults, consistent with a recent study of adults in which intermittent cultures were found in 13% of 1.071 SAB cases. In just 4% of the cases in that study, more than 2 days of negative blood cultures preceded a repeat positive culture.

The researchers noted several study limitations in their own research. Because more than half (61%) of patients had two or less FUBCs collected, and 21% one or less, they acknowledged that their conclusions are based on the presumption that the 61% of patients would not have any further positive cultures if they had been drawn. Relying on provider documentation also suggested that cases of bacteremia without an identified source also likely were overrepresented. The retrospective nature of the study only allowed for limited collection of standardized follow-up metrics with the limited patient sample available. Patient characteristics also may have affected the quality of study results because a large number of patients had underlying medical conditions or were premature infants.

Look for ongoing hemodynamic instability before third FUBC

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues only recommend a third FUBC in cases where patients demonstrate ongoing hemodynamic instability. Applying this to their study population, in retrospect, the authors noted that unnecessary FUBCs could have been prevented in 26% of patients included in the study. They further recommend a thorough clinical evaluation for any patients with SAB lasting 3 or more days with an unidentified infection source. Further research could be beneficial in evaluating cost savings that come from eliminating unnecessary cultures. Additionally, performing a powered analysis would help to determine the probability of an increase in complications based on implementation of these recommendations.

In a separate interview, Tina Q. Tan, MD, infectious disease specialist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago noted: “This study provides some importance evidence-based guidance on deciding how many blood cultures are needed to demonstrate clearance of S. aureus bacteremia, even in children who have intermittent positive cultures after having negative FUBCs. The recommendation that additional blood cultures to document sterility are not needed after 2 FUBC results are negative in well-appearing children is one that has the potential to decrease cost and unnecessary discomfort in patients. The recommendation currently is for well-appearing children; children who are ill appearing may require further blood cultures to document sterility. Even though this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients (n = 122), the information provided is a very useful guide to all clinicians who deal with this issue. Further studies are needed to determine the impact on cost reduction by the elimination of unnecessary blood cultures and whether the rate of complications would increase as a result of not obtaining further cultures in well-appearing children who have two negative follow up blood cultures.”

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues as well as Dr. Tan had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding for the study.

SOURCE: Cardenas-Comfort C et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1821.

reported Caitlin Cardenas-Comfort, MD, of the section of pediatric infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues.

In a retrospective cohort study of 122 pediatric patients with documented Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) that were hospitalized at one of three hospitals in the Texas Children’s Hospital network in Houston, Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues sought to determine whether specific recommendations can be made on the number of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) needed to document clearance of SAB. Patients included in the study were under 18 years of age and had confirmed diagnosis of SAB between Jan. 1, and Dec. 31, 2018.

Most cases of bacteremia resolve in under 48 hours

In the majority of cases, patients had bacteremia for less than 48 hours and few to no complications. Only 16% of patients experienced bacteremia lasting 3 or more days, and they had either central line-associated bloodstream infection, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis. In such cases, “patients with endovascular and closed-space infections are at an increased risk of persistent bacteremia,” warranting more conservative monitoring and follow-up, cautioned the researchers.

Although Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues did note an association between the duration of bacteremia and a diagnosis of infectious disease, increased risk for persistent SAB did not appear to be tied to an underlying medical condition, including immunosuppression.

Fewer than 5% of patients with SAB had intermittent positive cultures and fewer than 1% had repeat positive cultures following two negative FUBC results. For those patients with intermittent positive cultures, the risk of being diagnosed with endocarditis or osteomyelitis is more than double. The authors suggested that “source control could be a critical variable” increasing the risk for intermittent positive cultures, noting that surgical debridement occurred more than 24 hours following initial blood draw for every patient in the osteomyelitis group. In contrast, of those who had consistently negative FUBC results, only 2 of 33 (6%) had debridement in the same period, and only 6 of 33 (18%) required more than one debridement.

Children are less likely to have intermittent positive cultures

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues also observed that intermittent positive cultures may appear less frequently in children than adults, consistent with a recent study of adults in which intermittent cultures were found in 13% of 1.071 SAB cases. In just 4% of the cases in that study, more than 2 days of negative blood cultures preceded a repeat positive culture.

The researchers noted several study limitations in their own research. Because more than half (61%) of patients had two or less FUBCs collected, and 21% one or less, they acknowledged that their conclusions are based on the presumption that the 61% of patients would not have any further positive cultures if they had been drawn. Relying on provider documentation also suggested that cases of bacteremia without an identified source also likely were overrepresented. The retrospective nature of the study only allowed for limited collection of standardized follow-up metrics with the limited patient sample available. Patient characteristics also may have affected the quality of study results because a large number of patients had underlying medical conditions or were premature infants.

Look for ongoing hemodynamic instability before third FUBC

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues only recommend a third FUBC in cases where patients demonstrate ongoing hemodynamic instability. Applying this to their study population, in retrospect, the authors noted that unnecessary FUBCs could have been prevented in 26% of patients included in the study. They further recommend a thorough clinical evaluation for any patients with SAB lasting 3 or more days with an unidentified infection source. Further research could be beneficial in evaluating cost savings that come from eliminating unnecessary cultures. Additionally, performing a powered analysis would help to determine the probability of an increase in complications based on implementation of these recommendations.

In a separate interview, Tina Q. Tan, MD, infectious disease specialist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago noted: “This study provides some importance evidence-based guidance on deciding how many blood cultures are needed to demonstrate clearance of S. aureus bacteremia, even in children who have intermittent positive cultures after having negative FUBCs. The recommendation that additional blood cultures to document sterility are not needed after 2 FUBC results are negative in well-appearing children is one that has the potential to decrease cost and unnecessary discomfort in patients. The recommendation currently is for well-appearing children; children who are ill appearing may require further blood cultures to document sterility. Even though this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients (n = 122), the information provided is a very useful guide to all clinicians who deal with this issue. Further studies are needed to determine the impact on cost reduction by the elimination of unnecessary blood cultures and whether the rate of complications would increase as a result of not obtaining further cultures in well-appearing children who have two negative follow up blood cultures.”

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues as well as Dr. Tan had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding for the study.

SOURCE: Cardenas-Comfort C et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1821.

reported Caitlin Cardenas-Comfort, MD, of the section of pediatric infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues.

In a retrospective cohort study of 122 pediatric patients with documented Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) that were hospitalized at one of three hospitals in the Texas Children’s Hospital network in Houston, Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues sought to determine whether specific recommendations can be made on the number of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) needed to document clearance of SAB. Patients included in the study were under 18 years of age and had confirmed diagnosis of SAB between Jan. 1, and Dec. 31, 2018.

Most cases of bacteremia resolve in under 48 hours

In the majority of cases, patients had bacteremia for less than 48 hours and few to no complications. Only 16% of patients experienced bacteremia lasting 3 or more days, and they had either central line-associated bloodstream infection, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis. In such cases, “patients with endovascular and closed-space infections are at an increased risk of persistent bacteremia,” warranting more conservative monitoring and follow-up, cautioned the researchers.

Although Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues did note an association between the duration of bacteremia and a diagnosis of infectious disease, increased risk for persistent SAB did not appear to be tied to an underlying medical condition, including immunosuppression.

Fewer than 5% of patients with SAB had intermittent positive cultures and fewer than 1% had repeat positive cultures following two negative FUBC results. For those patients with intermittent positive cultures, the risk of being diagnosed with endocarditis or osteomyelitis is more than double. The authors suggested that “source control could be a critical variable” increasing the risk for intermittent positive cultures, noting that surgical debridement occurred more than 24 hours following initial blood draw for every patient in the osteomyelitis group. In contrast, of those who had consistently negative FUBC results, only 2 of 33 (6%) had debridement in the same period, and only 6 of 33 (18%) required more than one debridement.

Children are less likely to have intermittent positive cultures

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues also observed that intermittent positive cultures may appear less frequently in children than adults, consistent with a recent study of adults in which intermittent cultures were found in 13% of 1.071 SAB cases. In just 4% of the cases in that study, more than 2 days of negative blood cultures preceded a repeat positive culture.

The researchers noted several study limitations in their own research. Because more than half (61%) of patients had two or less FUBCs collected, and 21% one or less, they acknowledged that their conclusions are based on the presumption that the 61% of patients would not have any further positive cultures if they had been drawn. Relying on provider documentation also suggested that cases of bacteremia without an identified source also likely were overrepresented. The retrospective nature of the study only allowed for limited collection of standardized follow-up metrics with the limited patient sample available. Patient characteristics also may have affected the quality of study results because a large number of patients had underlying medical conditions or were premature infants.

Look for ongoing hemodynamic instability before third FUBC

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues only recommend a third FUBC in cases where patients demonstrate ongoing hemodynamic instability. Applying this to their study population, in retrospect, the authors noted that unnecessary FUBCs could have been prevented in 26% of patients included in the study. They further recommend a thorough clinical evaluation for any patients with SAB lasting 3 or more days with an unidentified infection source. Further research could be beneficial in evaluating cost savings that come from eliminating unnecessary cultures. Additionally, performing a powered analysis would help to determine the probability of an increase in complications based on implementation of these recommendations.

In a separate interview, Tina Q. Tan, MD, infectious disease specialist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago noted: “This study provides some importance evidence-based guidance on deciding how many blood cultures are needed to demonstrate clearance of S. aureus bacteremia, even in children who have intermittent positive cultures after having negative FUBCs. The recommendation that additional blood cultures to document sterility are not needed after 2 FUBC results are negative in well-appearing children is one that has the potential to decrease cost and unnecessary discomfort in patients. The recommendation currently is for well-appearing children; children who are ill appearing may require further blood cultures to document sterility. Even though this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients (n = 122), the information provided is a very useful guide to all clinicians who deal with this issue. Further studies are needed to determine the impact on cost reduction by the elimination of unnecessary blood cultures and whether the rate of complications would increase as a result of not obtaining further cultures in well-appearing children who have two negative follow up blood cultures.”

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues as well as Dr. Tan had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding for the study.

SOURCE: Cardenas-Comfort C et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1821.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Diabetic retinopathy may predict greater risk of COVID-19 severity

Risk of intubation for COVID-19 in very sick hospitalized patients was increased over fivefold in those with diabetic retinopathy, compared with those without, in a small single-center study from the United Kingdom.

Importantly, the risk of intubation was independent of conventional risk factors for poor COVID-19 outcomes.

“People with preexisting diabetes-related vascular damage, such as retinopathy, might be predisposed to a more severe form of COVID-19 requiring ventilation in the intensive therapy unit,” said lead investigator Janaka Karalliedde, MBBS, PhD.

Dr. Karalliedde and colleagues note that this is “the first description of diabetic retinopathy as a potential risk factor for poor COVID-19 outcomes.”

“For this reason, looking for the presence or history of retinopathy or other vascular complications of diabetes may help health care professionals identify patients at high risk of severe COVID-19,” added Dr. Karalliedde, of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London.

The study was published online in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.

Preexisting diabetic retinopathy and COVID-19 outcomes

The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is thought to be around 55% in people with type 1 diabetes and 30% in people with type 2 diabetes, on average.

Dr. Karalliedde is part of a research group at King’s College London that has been focused on how vascular disease may predispose to more severe COVID-19.

“COVID-19 affects the blood vessels all over the body,” he said, so they wondered whether having preexisting retinopathy “would predispose to a severe manifestation of COVID-19.”

The observational study included 187 patients with diabetes (179 patients with type 2 diabetes and 8 patients with type 1 diabetes) hospitalized with COVID-19 at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust between March 12 and April 7 (the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom).

“It was an ethnically diverse population who were very sick and provides a clinical observation of real life,” Dr. Karalliedde said.

Nearly half of patients were African Caribbean (44%), 39% were White, and 17% were of other ethnicities, including 8% who were Asian. The mean age of the cohort was 68 years (range, 22-97 years), and 60% were men.

Diabetic retinopathy was reported in 67 (36%) patients, of whom 80% had background retinopathy and 20% had more advanced retinopathy.

They then looked at whether the presence of retinopathy was associated with a more severe manifestation of COVID-19 as defined by the need for tracheal intubation.

Of the 187 patients, 26% were intubated and 45% of these patients had diabetic retinopathy.

The analysis showed those with diabetic retinopathy had an over-fivefold increased risk for intubation (odds ratio, 5.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-24.66).

Of the entire cohort, 32% of patients died, although no association was observed between retinopathy and mortality.

“A greater number of diabetes patients with COVID-19 ended up on the intensive therapy unit. Upon multivariate analysis, we found retinopathy was independently associated with ending up on the intensive therapy unit,” stressed Dr. Karalliedde.

However, they noted that, “due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot prove causality [between retinopathy and intubation]. Further studies are required to understand the mechanisms that explain the associations between retinopathy and other indices of microangiopathy with severe COVID-19.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk of intubation for COVID-19 in very sick hospitalized patients was increased over fivefold in those with diabetic retinopathy, compared with those without, in a small single-center study from the United Kingdom.

Importantly, the risk of intubation was independent of conventional risk factors for poor COVID-19 outcomes.

“People with preexisting diabetes-related vascular damage, such as retinopathy, might be predisposed to a more severe form of COVID-19 requiring ventilation in the intensive therapy unit,” said lead investigator Janaka Karalliedde, MBBS, PhD.

Dr. Karalliedde and colleagues note that this is “the first description of diabetic retinopathy as a potential risk factor for poor COVID-19 outcomes.”

“For this reason, looking for the presence or history of retinopathy or other vascular complications of diabetes may help health care professionals identify patients at high risk of severe COVID-19,” added Dr. Karalliedde, of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London.

The study was published online in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.

Preexisting diabetic retinopathy and COVID-19 outcomes

The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is thought to be around 55% in people with type 1 diabetes and 30% in people with type 2 diabetes, on average.

Dr. Karalliedde is part of a research group at King’s College London that has been focused on how vascular disease may predispose to more severe COVID-19.

“COVID-19 affects the blood vessels all over the body,” he said, so they wondered whether having preexisting retinopathy “would predispose to a severe manifestation of COVID-19.”

The observational study included 187 patients with diabetes (179 patients with type 2 diabetes and 8 patients with type 1 diabetes) hospitalized with COVID-19 at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust between March 12 and April 7 (the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom).

“It was an ethnically diverse population who were very sick and provides a clinical observation of real life,” Dr. Karalliedde said.

Nearly half of patients were African Caribbean (44%), 39% were White, and 17% were of other ethnicities, including 8% who were Asian. The mean age of the cohort was 68 years (range, 22-97 years), and 60% were men.

Diabetic retinopathy was reported in 67 (36%) patients, of whom 80% had background retinopathy and 20% had more advanced retinopathy.

They then looked at whether the presence of retinopathy was associated with a more severe manifestation of COVID-19 as defined by the need for tracheal intubation.

Of the 187 patients, 26% were intubated and 45% of these patients had diabetic retinopathy.

The analysis showed those with diabetic retinopathy had an over-fivefold increased risk for intubation (odds ratio, 5.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-24.66).

Of the entire cohort, 32% of patients died, although no association was observed between retinopathy and mortality.

“A greater number of diabetes patients with COVID-19 ended up on the intensive therapy unit. Upon multivariate analysis, we found retinopathy was independently associated with ending up on the intensive therapy unit,” stressed Dr. Karalliedde.

However, they noted that, “due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot prove causality [between retinopathy and intubation]. Further studies are required to understand the mechanisms that explain the associations between retinopathy and other indices of microangiopathy with severe COVID-19.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk of intubation for COVID-19 in very sick hospitalized patients was increased over fivefold in those with diabetic retinopathy, compared with those without, in a small single-center study from the United Kingdom.

Importantly, the risk of intubation was independent of conventional risk factors for poor COVID-19 outcomes.

“People with preexisting diabetes-related vascular damage, such as retinopathy, might be predisposed to a more severe form of COVID-19 requiring ventilation in the intensive therapy unit,” said lead investigator Janaka Karalliedde, MBBS, PhD.

Dr. Karalliedde and colleagues note that this is “the first description of diabetic retinopathy as a potential risk factor for poor COVID-19 outcomes.”

“For this reason, looking for the presence or history of retinopathy or other vascular complications of diabetes may help health care professionals identify patients at high risk of severe COVID-19,” added Dr. Karalliedde, of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London.

The study was published online in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.

Preexisting diabetic retinopathy and COVID-19 outcomes

The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is thought to be around 55% in people with type 1 diabetes and 30% in people with type 2 diabetes, on average.

Dr. Karalliedde is part of a research group at King’s College London that has been focused on how vascular disease may predispose to more severe COVID-19.

“COVID-19 affects the blood vessels all over the body,” he said, so they wondered whether having preexisting retinopathy “would predispose to a severe manifestation of COVID-19.”

The observational study included 187 patients with diabetes (179 patients with type 2 diabetes and 8 patients with type 1 diabetes) hospitalized with COVID-19 at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust between March 12 and April 7 (the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom).

“It was an ethnically diverse population who were very sick and provides a clinical observation of real life,” Dr. Karalliedde said.

Nearly half of patients were African Caribbean (44%), 39% were White, and 17% were of other ethnicities, including 8% who were Asian. The mean age of the cohort was 68 years (range, 22-97 years), and 60% were men.

Diabetic retinopathy was reported in 67 (36%) patients, of whom 80% had background retinopathy and 20% had more advanced retinopathy.

They then looked at whether the presence of retinopathy was associated with a more severe manifestation of COVID-19 as defined by the need for tracheal intubation.

Of the 187 patients, 26% were intubated and 45% of these patients had diabetic retinopathy.

The analysis showed those with diabetic retinopathy had an over-fivefold increased risk for intubation (odds ratio, 5.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-24.66).

Of the entire cohort, 32% of patients died, although no association was observed between retinopathy and mortality.

“A greater number of diabetes patients with COVID-19 ended up on the intensive therapy unit. Upon multivariate analysis, we found retinopathy was independently associated with ending up on the intensive therapy unit,” stressed Dr. Karalliedde.

However, they noted that, “due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot prove causality [between retinopathy and intubation]. Further studies are required to understand the mechanisms that explain the associations between retinopathy and other indices of microangiopathy with severe COVID-19.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID redefines curriculum for hospitalists-in-training

Pandemic brings ‘clarity and urgency’

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted all facets of the education and training of this country’s future hospitalists, including their medical school coursework, elective rotations, clerkships, and residency training – although with variations between settings and localities.

The COVID-19 crisis demanded immediate changes in traditional approaches to medical education. Training programs responded quickly to institute those changes. As hospitals geared up for potential surges in COVID cases starting in mid-March, many onsite training activities for medical students were shut down in order to reserve personal protective equipment for essential personnel and not put learners at risk of catching the virus. A variety of events related to their education were canceled. Didactic presentations and meetings were converted to virtual gatherings on internet platforms such as Zoom. Many of these changes were adopted even in settings with few actual COVID cases.

Medical students on clinical rotations were provided with virtual didactics when in-person clinical experiences were put on hold. In some cases, academic years ended early and fourth-year students graduated early so they might potentially join the hospital work force. Residents’ assignments were also changed, perhaps seeing patients on non–COVID-19 units only or taking different shifts, assignments, or rotations. Public health or research projects replaced elective placements. New electives were created, along with journal clubs, online care conferences, and technology-facilitated, self-directed learning.

But every advancing medical student needs to rotate through an experience of taking care of real patients, said Amy Guiot, MD, MEd, a hospitalist and associate director of medical student education in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “The Liaison Committee of Medical Education, jointly sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association, will not let you graduate a medical student without actual hands-on encounters with patients,” she explained.

For future doctors, especially those pursuing internal medicine – many of whom will practice as hospitalists – their training can’t duplicate “in the hospital” experiences except in the hospital, said Dr. Guiot, who is involved in pediatric training for medical students from the University of Cincinnati and residents.

For third- and fourth-year medical students, getting that personal contact with patients has been the hardest part, she added. But from March to May 2020, that experience was completely shut down at CCHMC, as at many medical schools, because of precautions aimed at preventing exposure to the novel coronavirus for both students and patients. That meant hospitals had to get creative, reshuffling schedules and the order of learning experiences; converting everything possible to virtual encounters on platforms such as Zoom; and reducing the length of rotations, the total number of in-person encounters, and the number of learners participating in an activity.

“We needed to use shift work for medical students, which hadn’t been done before,” Dr. Guiot said. Having students on different shifts, including nights, created more opportunities to fit clinical experiences into the schedule. The use of standardized patients – actors following a script who are examined by a student as part of learning how to do a physical exam – was also put on hold.

“Now we’re starting to get it back, but maybe not as often,” she said. “The actor wears a mask. The student wears a mask and shield. But it’s been harder for us to find actors – who tend to be older adults who may fear coming to the medical center – to perform their role, teaching medical students the art of examining a patient.”

Back to basics

The COVID-19 pandemic forced medical schools to get back to basics, figuring out the key competencies students needed to learn, said Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC’s chief medical education officer. Both medical schools and residency programs needed to respond quickly and in new ways, including with course content that would teach students about the virus and its management and treatment.

Schools have faced crises before, responding in real time to SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), Ebola, HIV, and natural disasters, Dr. Whelan said. “But there was a nimbleness and rapidity of adapting to COVID – with a lot of sharing of curriculums among medical colleges.” Back in late March, AAMC put out guidelines that recommended removing students from direct patient contact – not just for the student’s protection but for the community’s. A subsequent guidance, released Aug. 14, emphasized the need for medical schools to continue medical education – with appropriate attention to safety and local conditions while working closely with clinical partners.

Dr. Guiot, with her colleague Leslie Farrell, MD, and four very creative medical students, developed an online fourth-year elective course for University of Cincinnati medical students, offered asynchronously. It aimed to transmit a comprehensive understanding of COVID-19, its virology, transmission, clinical prevention, diagnosis and treatment, as well as examining national and international responses to the pandemic and their consequences and related issues of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and health disparities. “We used several articles from the Journal of Hospital Medicine for students to read and discuss,” Dr. Guiot said.

Christopher Sankey, MD, SFHM, associate program director of the traditional internal medicine residency program and associate professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., oversees the inpatient educational experience for internal medicine residents at Yale. “As with most programs, there was a lot of trepidation as we made the transition from in-person to virtual education,” he said.

The two principal, non–ward-based educational opportunities for the Yale residents are morning report, which involves a case-based discussion of various medical issues, usually led by a chief resident, and noon conference, which is more didactic and content based. Both made the transition to virtual meetings for residents.

“We wondered, could these still be well-attended, well-liked, and successful learning experiences if offered virtually? What I found when I surveyed our residents was that the virtual conferences were not only well received, but actually preferred,” Dr. Sankey said. “We have a large campus with lots of internal medicine services, so it’s hard to assemble everyone for meetings. There were also situations in which there were so many residents that they couldn’t all fit into the same room.” Zoom, the virtual platform of choice, has actually increased attendance.

Marc Miller, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic, helped his team develop a virtual curriculum in pediatrics presented to third-year medical students during the month of May, when medical students were being taken off the wards. “Some third-year students still needed to get their pediatric clerkships done. We had to balance clinical exposure with a lot of other things,” he explained.

The curriculum included a focus on interprofessional aspects of interdisciplinary, family-centered bedside rounds; a COVID literature review; and a lot of case-based scenarios. “Most challenging was how to remake family rounds. We tried to incorporate students into table rounds, but that didn’t feel as valuable,” Dr. Miller said. “Because pediatrics is so family centered, talking to patients and families at the bedside is highly valued. So we had virtual sessions talking about how to do that, with videos to illustrate it put out by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.”

The most interactive sessions got the best feedback, but all the sessions went over very well, Dr. Miller said. “Larger lessons from COVID include things we already knew, but now with extra importance, such as the need to encourage interactivity to get students to buy in and take part in these conversations – whatever the structure.”

Vineet Arora, MD, MHM, an academic hospitalist and chief medical officer for the clinical learning environment at the University of Chicago, said that the changes wrought by COVID have also produced unexpected gains for medical education. “We’ve also had to think differently and more creatively about how to get the same information across in this new environment,” she explained. “In some cases, we saw that it was easier for learners to attend conferences and meetings online, with increased attendance for our events.” That includes participation on quality improvement committees, and attending online medical conferences presented locally and regionally.

“Another question: How do we teach interdisciplinary rounds and how to work with other members of the team without having face-to-face interactions?” Dr. Arora said. “Our old interdisciplinary rounding model had to change. It forced us to rethink how to create that kind of learning. We can’t have as many people in the patient’s room at one time. Can there be a physically distanced ‘touch-base’ with the nurse outside the patient’s room after a doctor has gone in to meet the patient?”

Transformational change

In a recent JAMA Viewpoint column, Catherine R. Lucey, MD, and S. Claiborne Johnston, MD, PhD,1 called the impact of COVID-19 “transformational,” in line with changes in medical curriculums recommended by the 2010 Global Independent Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century,2 which asserted that the purpose of professional education is to improve the health of communities.

The authors stated that COVID-19 brought clarity and urgency to this purpose, and will someday be viewed as a catalyst for the needed transformation of medical education as medical schools embarked on curriculum redesign to embrace new competencies for current health challenges.

They suggested that medical students not only continued to learn during the COVID crisis “but in many circumstances, accelerated their attainment of the types of competencies that 21st century physicians must master.” Emerging competencies identified by Dr. Lucey and Dr. Johnston include:

- Being able to address population and public health issues

- Designing and continuously improving of the health care system

- Incorporating data and technology in service to patient care, research, and education

- Eliminating health care disparities and discrimination in medicine

- Adapting the curriculum to current issues in real-time

- Engaging in crisis communication and active change leadership

How is the curriculum changing? It’s still a work in progress. “After the disruptions of the spring and summer, schools are now trying to figure which of the changes should stay,” said Dr. Whelan. “The virus has also highlighted other crises, with social determinants of health and racial disparities becoming more front and center. In terms of content, medical educators are rethinking a lot of things – in a good way.”

Another important trend cast in sharper relief by the pandemic is a gradual evolution toward competency-based education and how to assess when someone is ready to be a doctor, Dr. Whelan said. “There’s been an accelerated consideration of how to be sure each student is competent to practice medicine.”3

Many practicing physicians and students were redeployed in the crisis, she said. Pediatric physicians were asked to take care of adult patients, and internists were drafted to work in the ICU. Hospitals quickly developed refresher courses and competency-based assessments to facilitate these redeployments. What can be learned from such on-the-fly assessments? What was needed to make a pediatrician, under the supervision of an internist, able to take good care of adult patients?

And does competency-based assessment point toward some kind of time-variable graduate medical education of the future – with graduation when the competencies are achieved, rather than just tethered to time- and case volume–based requirements? It seems Canada is moving in this direction, and COVID might catalyze a similar transformation in the United States.3

Changing the curriculum