User login

Three pillars of a successful coronavirus vaccine program in minorities

As COVID-19 cases soared to new daily highs across the United States, November 2020 brought some exciting and promising vaccine efficacy results. Currently, the United States has four COVID-19 vaccines in phase 3 trials: the Moderna vaccine (mRNA-1273), the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine (AZD1222), Pfizer/BioNTech’s (BNT162), and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine (JNJ-78436735).

While Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna received fast-track designation by the Food and Drug Administration, AZD1222 and JNJ-78436735 trials were resumed after a temporary hold. Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have also submitted an emergency-use authorization application to the FDA after favorable results from a completed phase 3 clinical trial. The results so far seem promising, with Oxford/AstraZeneca’s combined analysis from different dosing regimens resulting in an average efficacy of 70%. Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna have each reported vaccines that are 90% and 95% effective respectively in trials.

However, even with a safe and effective vaccine, there must be an equal emphasis on a successful coronavirus vaccine program’s three pillars in the communities that are the hardest hit: participation in the vaccine trials by minority populations, equitable allocation and distribution of vaccine for minority populations, and immunization uptake by minority populations.

1. Participation in the vaccine trials by minority populations

With a great emphasis on the inclusion of diverse populations, the Moderna vaccine clinical trials gained participation by racial and ethnic minorities. As of Oct. 21, 2020, the Moderna vaccine trial participants were 10% African American, 20% Hispanic, 4% Asian, 63% White, and 3% other.1 Pharmaceutical giant Pfizer also had approximately 42% of overall – and 45% of U.S. – participants from diverse backgrounds. The proportional registration of racially and ethnically diverse participants in other vaccine trials is also anticipated to be challenging.

Though there has been an improvement in minority participation in COVID-19 vaccine trials, it is still below the ideal representation when compared with U.S. census data.2 Ideally, participants in a clinical trial should represent the U.S. population to get a full picture of a medical product’s risks and benefits. However, recruitment rates in clinical trials have remained low among minorities for various reasons. Historically, African Americans make up only 5% of participants in U.S. clinical trials, while they represent 13% of the country’s general population; likewise, Hispanics are also underrepresented.3

The legacy of distrust in the medical system is deep-rooted and is one of the most substantial barriers to clinical trial participation. A plethora of unethical trials and experiments on the African American population have left a lasting impact. The most infamous and widely known was the “Tuskegee Study,” conducted by the United States Public Health Service to “observe the natural history of untreated syphilis” in Black populations. In the study, performed without informed consent, Black men with latent or late syphilis received no treatment, even after penicillin was discovered as a safe and reliable cure for syphilis. This human experimentation lasted for 40 years, resulting in 128 male patients who died from syphilis or its complications, 40 of their spouses infected, and 19 of their children with acquired congenital syphilis.

In another case, the father of modern gynecology, J. Marion Sims, allegedly performed experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women without consent. For more than 4 decades, North Carolina’s statewide eugenics program forcibly sterilized almost 7,600 people, many of whom were Black. Another story of exploitation involves Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, responsible for some of the most important medical advances of all time. Though her cells were commercialized and generated millions for medical researchers, neither Ms. Lacks nor her family knew the cell cultures existed until more than 20 years after her death from cervical cancer. Many years later, victims and families of the Tuskegee experiment, individuals sterilized by the Eugenics Board of North Carolina, and the family of Henrietta Lacks received compensation, and Sims’s statue was taken down in 2018. Not too long ago, many criticized the FDA’s “Exception from Informed Consent policy” for compromising patients’ exercise of autonomy, and concern for overrepresenting African Americans in the U.S. EFIC trials.

Racial disparities in medical treatment and unconscious biases among providers are among the reasons for mistrust and lack of trial participation by minority populations today. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said that recent social upheaval sparked by the death of George Floyd has likely added to feelings of mistrust between minority groups and government or pharmaceutical companies. “Yet we need their participation if this is going to have a meaningful outcome,” he said.

While “Operation Warp Speed” is committed to developing and delivering a COVID-19 vaccine rapidly while adhering to safety and efficacy standards, the challenges to enrolling people from racial and ethnic minorities in trials have been a concern. The political partisanship and ever-shifting stances on widespread COVID-19 testing, use of facemasks, endorsement of unproven drugs for the disease, and accusations against the FDA for delaying human trials for the vaccine have contributed to the skepticism as well. Tremendous pressure for a rushed vaccine with unrealistic timelines, recent holds on AZD1222 and JNJ-78436735 as well as the AZD1222 dosage error during trials have also raised skepticism of the safety and efficacy of vaccine trials.

2. Equitable allocation and distribution of vaccine for minority populations

Enrollment in clinical trials is just a beginning; a more significant challenge would be the vaccine’s uptake when available to the general public. We still lack a consensus on whether it is lawful for race to be an explicit criterion for priority distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. Recently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested that the vaccine amount allotted to jurisdictions might be based on critical populations recommended for vaccination by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices with input from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The NASEM framework lays out four-phased vaccine distribution approaches, emphasizing social equity by prioritizing vaccines for geographic areas identified through CDC’s social vulnerability index (SVI) or another more specific index. SVI has been a robust composite marker of minority status and language, household composition and transportation, and housing and disability, and predicted COVID-19 case counts in the United States in several studies. The National Academy of Medicine has also recommended racial minorities receive priority vaccination because they have been hard hit and are “worse off” socioeconomically.

3. Immunization uptake by minority populations

Though minority participation is crucial in developing the vaccine, more transparency, open discussions on ethical distribution, and awareness of side effects are required before vaccine approval or emergency-use authorization. Companies behind the four major COVID-19 vaccines in development have released their trials’ protocols, details on vaccine efficacy, and each product’s makeup to increase acceptance of the vaccine.

According to a recent Pew research study, about half of U.S. adults (51%) now say they would definitely or probably get a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 if it were available today. Nearly as many (49%) say they definitely or probably would not get vaccinated at this time. Intent to get a COVID-19 vaccine has fallen from 72% in May 2020, a 21–percentage point drop, and Black adults were much less likely to say they would get a vaccine than other Americans.3 This is concerning as previous studies have shown that race and ethnicity can influence immune responses to vaccination. There is evidence of racial and ethnic differences in immune response following rubella vaccination, Hib–tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine, antibody responses to the influenza A virus components of IIV3 or 4, and immune responses after measles vaccination.4-9

On the other hand, significant differences in reporting rates of adverse events after human papillomavirus vaccinations were found in different race and ethnicity groups in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.10 Thus, there is ample evidence that race and ethnicity affect responsiveness to a vaccine. Inequity in participation in a clinical trial may lead to an ineffective or one with a suboptimal response or even an unsafe vaccine.

When we look at other immunization programs, according to various surveys in recent years, non-Hispanic Blacks have lower annual vaccination rates for flu, pneumonia, and human papillomavirus vaccinations nationally, compared with non-Hispanic White adults.11 It is a cause of concern as a proportion of the population must be vaccinated to reach “community immunity” or “herd immunity” from vaccination. Depending on varying biological, environmental, and sociobehavioral factors, the threshold for COVID-19 herd immunity may be between 55% and 82% of the population.12 Hence, neither a vaccine trial nor an immunization program can succeed without participation from all communities and age groups.

Role of hospitalists

Hospitalists, who give immunizations as part of the hospital inpatient quality reporting program, are uniquely placed in this pandemic. Working on the front lines, we may encounter questions, concerns, rejections, and discussions about the pros and cons of the COVID-19 vaccine from patients.

Investigators at Children’s National Hospital and George Washington University, both in Washington, recently recommended three steps physicians and others can take now to ensure more people get the COVID-19 vaccine when it is available. Engaging frontline health professionals was one of the suggested steps to encourage more people to get the vaccine.13 However, it is imperative to understand that vaccine hesitancy might be an issue for health care providers as well, if concerns for scientific standards and involvement of diverse populations are not addressed.

We are only starting to develop a safe and effective immunization program. We must bring more to unrepresented communities than just vaccine trials. Information, education, availability, and access to the vaccines will make for a successful COVID-19 immunization program.

Dr. Saigal is a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

References

1. Moderna. COVE study. 2020 Oct 21. https://www.modernatx.com/sites/default/files/content_documents/2020-COVE-Study-Enrollment-Completion-10.22.20.pdf

2. U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: Population estimates, July 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

3. Pew Research Center. U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether To Get COVID-19 Vaccine. 2020 Sep 17. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/17/u-s-public-now-divided-over-whether-to-get-covid-19-vaccine/

4. Haralambieva IH et al. Associations between race sex and immune response variations to rubella vaccination in two independent cohorts. Vaccine. 2014;32:1946-53.

5. McQuillan GM et al. Seroprevalence of measles antibody in the U.S. population 1999-2004. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1459–64. doi: 10.1086/522866.

6. Christy C et al. Effect of gender race and parental education on immunogenicity and reported reactogenicity of acellular and whole-cell pertussis vaccines. Pediatrics. 1995;96:584-7.

7. Poland GA et al. Measles antibody seroprevalence rates among immunized Inuit Innu and Caucasian subjects. Vaccine. 1999;17:1525-31.

8. Greenberg DP et al. Immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine in young infants. The Kaiser-UCLA Vaccine Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:76-81.

9. Kurupati R et al. Race-related differences in antibody responses to the inactivated influenza vaccine are linked to distinct prevaccination gene expression profiles in blood. Oncotarget. 2016;7(39):62898-911.

10. Huang J et al. Characterization of the differential adverse event rates by race/ethnicity groups for HPV vaccine by integrating data from different sources. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:539.

11. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=22

12. Sanche S et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7).

13. American Medical Association. How to ready patients now so they’ll get a COVID-19 vaccine later. 2020 May 27. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/how-ready-patients-now-so-they-ll-get-covid-19-vaccine-later

As COVID-19 cases soared to new daily highs across the United States, November 2020 brought some exciting and promising vaccine efficacy results. Currently, the United States has four COVID-19 vaccines in phase 3 trials: the Moderna vaccine (mRNA-1273), the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine (AZD1222), Pfizer/BioNTech’s (BNT162), and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine (JNJ-78436735).

While Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna received fast-track designation by the Food and Drug Administration, AZD1222 and JNJ-78436735 trials were resumed after a temporary hold. Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have also submitted an emergency-use authorization application to the FDA after favorable results from a completed phase 3 clinical trial. The results so far seem promising, with Oxford/AstraZeneca’s combined analysis from different dosing regimens resulting in an average efficacy of 70%. Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna have each reported vaccines that are 90% and 95% effective respectively in trials.

However, even with a safe and effective vaccine, there must be an equal emphasis on a successful coronavirus vaccine program’s three pillars in the communities that are the hardest hit: participation in the vaccine trials by minority populations, equitable allocation and distribution of vaccine for minority populations, and immunization uptake by minority populations.

1. Participation in the vaccine trials by minority populations

With a great emphasis on the inclusion of diverse populations, the Moderna vaccine clinical trials gained participation by racial and ethnic minorities. As of Oct. 21, 2020, the Moderna vaccine trial participants were 10% African American, 20% Hispanic, 4% Asian, 63% White, and 3% other.1 Pharmaceutical giant Pfizer also had approximately 42% of overall – and 45% of U.S. – participants from diverse backgrounds. The proportional registration of racially and ethnically diverse participants in other vaccine trials is also anticipated to be challenging.

Though there has been an improvement in minority participation in COVID-19 vaccine trials, it is still below the ideal representation when compared with U.S. census data.2 Ideally, participants in a clinical trial should represent the U.S. population to get a full picture of a medical product’s risks and benefits. However, recruitment rates in clinical trials have remained low among minorities for various reasons. Historically, African Americans make up only 5% of participants in U.S. clinical trials, while they represent 13% of the country’s general population; likewise, Hispanics are also underrepresented.3

The legacy of distrust in the medical system is deep-rooted and is one of the most substantial barriers to clinical trial participation. A plethora of unethical trials and experiments on the African American population have left a lasting impact. The most infamous and widely known was the “Tuskegee Study,” conducted by the United States Public Health Service to “observe the natural history of untreated syphilis” in Black populations. In the study, performed without informed consent, Black men with latent or late syphilis received no treatment, even after penicillin was discovered as a safe and reliable cure for syphilis. This human experimentation lasted for 40 years, resulting in 128 male patients who died from syphilis or its complications, 40 of their spouses infected, and 19 of their children with acquired congenital syphilis.

In another case, the father of modern gynecology, J. Marion Sims, allegedly performed experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women without consent. For more than 4 decades, North Carolina’s statewide eugenics program forcibly sterilized almost 7,600 people, many of whom were Black. Another story of exploitation involves Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, responsible for some of the most important medical advances of all time. Though her cells were commercialized and generated millions for medical researchers, neither Ms. Lacks nor her family knew the cell cultures existed until more than 20 years after her death from cervical cancer. Many years later, victims and families of the Tuskegee experiment, individuals sterilized by the Eugenics Board of North Carolina, and the family of Henrietta Lacks received compensation, and Sims’s statue was taken down in 2018. Not too long ago, many criticized the FDA’s “Exception from Informed Consent policy” for compromising patients’ exercise of autonomy, and concern for overrepresenting African Americans in the U.S. EFIC trials.

Racial disparities in medical treatment and unconscious biases among providers are among the reasons for mistrust and lack of trial participation by minority populations today. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said that recent social upheaval sparked by the death of George Floyd has likely added to feelings of mistrust between minority groups and government or pharmaceutical companies. “Yet we need their participation if this is going to have a meaningful outcome,” he said.

While “Operation Warp Speed” is committed to developing and delivering a COVID-19 vaccine rapidly while adhering to safety and efficacy standards, the challenges to enrolling people from racial and ethnic minorities in trials have been a concern. The political partisanship and ever-shifting stances on widespread COVID-19 testing, use of facemasks, endorsement of unproven drugs for the disease, and accusations against the FDA for delaying human trials for the vaccine have contributed to the skepticism as well. Tremendous pressure for a rushed vaccine with unrealistic timelines, recent holds on AZD1222 and JNJ-78436735 as well as the AZD1222 dosage error during trials have also raised skepticism of the safety and efficacy of vaccine trials.

2. Equitable allocation and distribution of vaccine for minority populations

Enrollment in clinical trials is just a beginning; a more significant challenge would be the vaccine’s uptake when available to the general public. We still lack a consensus on whether it is lawful for race to be an explicit criterion for priority distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. Recently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested that the vaccine amount allotted to jurisdictions might be based on critical populations recommended for vaccination by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices with input from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The NASEM framework lays out four-phased vaccine distribution approaches, emphasizing social equity by prioritizing vaccines for geographic areas identified through CDC’s social vulnerability index (SVI) or another more specific index. SVI has been a robust composite marker of minority status and language, household composition and transportation, and housing and disability, and predicted COVID-19 case counts in the United States in several studies. The National Academy of Medicine has also recommended racial minorities receive priority vaccination because they have been hard hit and are “worse off” socioeconomically.

3. Immunization uptake by minority populations

Though minority participation is crucial in developing the vaccine, more transparency, open discussions on ethical distribution, and awareness of side effects are required before vaccine approval or emergency-use authorization. Companies behind the four major COVID-19 vaccines in development have released their trials’ protocols, details on vaccine efficacy, and each product’s makeup to increase acceptance of the vaccine.

According to a recent Pew research study, about half of U.S. adults (51%) now say they would definitely or probably get a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 if it were available today. Nearly as many (49%) say they definitely or probably would not get vaccinated at this time. Intent to get a COVID-19 vaccine has fallen from 72% in May 2020, a 21–percentage point drop, and Black adults were much less likely to say they would get a vaccine than other Americans.3 This is concerning as previous studies have shown that race and ethnicity can influence immune responses to vaccination. There is evidence of racial and ethnic differences in immune response following rubella vaccination, Hib–tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine, antibody responses to the influenza A virus components of IIV3 or 4, and immune responses after measles vaccination.4-9

On the other hand, significant differences in reporting rates of adverse events after human papillomavirus vaccinations were found in different race and ethnicity groups in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.10 Thus, there is ample evidence that race and ethnicity affect responsiveness to a vaccine. Inequity in participation in a clinical trial may lead to an ineffective or one with a suboptimal response or even an unsafe vaccine.

When we look at other immunization programs, according to various surveys in recent years, non-Hispanic Blacks have lower annual vaccination rates for flu, pneumonia, and human papillomavirus vaccinations nationally, compared with non-Hispanic White adults.11 It is a cause of concern as a proportion of the population must be vaccinated to reach “community immunity” or “herd immunity” from vaccination. Depending on varying biological, environmental, and sociobehavioral factors, the threshold for COVID-19 herd immunity may be between 55% and 82% of the population.12 Hence, neither a vaccine trial nor an immunization program can succeed without participation from all communities and age groups.

Role of hospitalists

Hospitalists, who give immunizations as part of the hospital inpatient quality reporting program, are uniquely placed in this pandemic. Working on the front lines, we may encounter questions, concerns, rejections, and discussions about the pros and cons of the COVID-19 vaccine from patients.

Investigators at Children’s National Hospital and George Washington University, both in Washington, recently recommended three steps physicians and others can take now to ensure more people get the COVID-19 vaccine when it is available. Engaging frontline health professionals was one of the suggested steps to encourage more people to get the vaccine.13 However, it is imperative to understand that vaccine hesitancy might be an issue for health care providers as well, if concerns for scientific standards and involvement of diverse populations are not addressed.

We are only starting to develop a safe and effective immunization program. We must bring more to unrepresented communities than just vaccine trials. Information, education, availability, and access to the vaccines will make for a successful COVID-19 immunization program.

Dr. Saigal is a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

References

1. Moderna. COVE study. 2020 Oct 21. https://www.modernatx.com/sites/default/files/content_documents/2020-COVE-Study-Enrollment-Completion-10.22.20.pdf

2. U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: Population estimates, July 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

3. Pew Research Center. U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether To Get COVID-19 Vaccine. 2020 Sep 17. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/17/u-s-public-now-divided-over-whether-to-get-covid-19-vaccine/

4. Haralambieva IH et al. Associations between race sex and immune response variations to rubella vaccination in two independent cohorts. Vaccine. 2014;32:1946-53.

5. McQuillan GM et al. Seroprevalence of measles antibody in the U.S. population 1999-2004. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1459–64. doi: 10.1086/522866.

6. Christy C et al. Effect of gender race and parental education on immunogenicity and reported reactogenicity of acellular and whole-cell pertussis vaccines. Pediatrics. 1995;96:584-7.

7. Poland GA et al. Measles antibody seroprevalence rates among immunized Inuit Innu and Caucasian subjects. Vaccine. 1999;17:1525-31.

8. Greenberg DP et al. Immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine in young infants. The Kaiser-UCLA Vaccine Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:76-81.

9. Kurupati R et al. Race-related differences in antibody responses to the inactivated influenza vaccine are linked to distinct prevaccination gene expression profiles in blood. Oncotarget. 2016;7(39):62898-911.

10. Huang J et al. Characterization of the differential adverse event rates by race/ethnicity groups for HPV vaccine by integrating data from different sources. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:539.

11. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=22

12. Sanche S et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7).

13. American Medical Association. How to ready patients now so they’ll get a COVID-19 vaccine later. 2020 May 27. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/how-ready-patients-now-so-they-ll-get-covid-19-vaccine-later

As COVID-19 cases soared to new daily highs across the United States, November 2020 brought some exciting and promising vaccine efficacy results. Currently, the United States has four COVID-19 vaccines in phase 3 trials: the Moderna vaccine (mRNA-1273), the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine (AZD1222), Pfizer/BioNTech’s (BNT162), and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine (JNJ-78436735).

While Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna received fast-track designation by the Food and Drug Administration, AZD1222 and JNJ-78436735 trials were resumed after a temporary hold. Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have also submitted an emergency-use authorization application to the FDA after favorable results from a completed phase 3 clinical trial. The results so far seem promising, with Oxford/AstraZeneca’s combined analysis from different dosing regimens resulting in an average efficacy of 70%. Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna have each reported vaccines that are 90% and 95% effective respectively in trials.

However, even with a safe and effective vaccine, there must be an equal emphasis on a successful coronavirus vaccine program’s three pillars in the communities that are the hardest hit: participation in the vaccine trials by minority populations, equitable allocation and distribution of vaccine for minority populations, and immunization uptake by minority populations.

1. Participation in the vaccine trials by minority populations

With a great emphasis on the inclusion of diverse populations, the Moderna vaccine clinical trials gained participation by racial and ethnic minorities. As of Oct. 21, 2020, the Moderna vaccine trial participants were 10% African American, 20% Hispanic, 4% Asian, 63% White, and 3% other.1 Pharmaceutical giant Pfizer also had approximately 42% of overall – and 45% of U.S. – participants from diverse backgrounds. The proportional registration of racially and ethnically diverse participants in other vaccine trials is also anticipated to be challenging.

Though there has been an improvement in minority participation in COVID-19 vaccine trials, it is still below the ideal representation when compared with U.S. census data.2 Ideally, participants in a clinical trial should represent the U.S. population to get a full picture of a medical product’s risks and benefits. However, recruitment rates in clinical trials have remained low among minorities for various reasons. Historically, African Americans make up only 5% of participants in U.S. clinical trials, while they represent 13% of the country’s general population; likewise, Hispanics are also underrepresented.3

The legacy of distrust in the medical system is deep-rooted and is one of the most substantial barriers to clinical trial participation. A plethora of unethical trials and experiments on the African American population have left a lasting impact. The most infamous and widely known was the “Tuskegee Study,” conducted by the United States Public Health Service to “observe the natural history of untreated syphilis” in Black populations. In the study, performed without informed consent, Black men with latent or late syphilis received no treatment, even after penicillin was discovered as a safe and reliable cure for syphilis. This human experimentation lasted for 40 years, resulting in 128 male patients who died from syphilis or its complications, 40 of their spouses infected, and 19 of their children with acquired congenital syphilis.

In another case, the father of modern gynecology, J. Marion Sims, allegedly performed experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women without consent. For more than 4 decades, North Carolina’s statewide eugenics program forcibly sterilized almost 7,600 people, many of whom were Black. Another story of exploitation involves Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, responsible for some of the most important medical advances of all time. Though her cells were commercialized and generated millions for medical researchers, neither Ms. Lacks nor her family knew the cell cultures existed until more than 20 years after her death from cervical cancer. Many years later, victims and families of the Tuskegee experiment, individuals sterilized by the Eugenics Board of North Carolina, and the family of Henrietta Lacks received compensation, and Sims’s statue was taken down in 2018. Not too long ago, many criticized the FDA’s “Exception from Informed Consent policy” for compromising patients’ exercise of autonomy, and concern for overrepresenting African Americans in the U.S. EFIC trials.

Racial disparities in medical treatment and unconscious biases among providers are among the reasons for mistrust and lack of trial participation by minority populations today. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said that recent social upheaval sparked by the death of George Floyd has likely added to feelings of mistrust between minority groups and government or pharmaceutical companies. “Yet we need their participation if this is going to have a meaningful outcome,” he said.

While “Operation Warp Speed” is committed to developing and delivering a COVID-19 vaccine rapidly while adhering to safety and efficacy standards, the challenges to enrolling people from racial and ethnic minorities in trials have been a concern. The political partisanship and ever-shifting stances on widespread COVID-19 testing, use of facemasks, endorsement of unproven drugs for the disease, and accusations against the FDA for delaying human trials for the vaccine have contributed to the skepticism as well. Tremendous pressure for a rushed vaccine with unrealistic timelines, recent holds on AZD1222 and JNJ-78436735 as well as the AZD1222 dosage error during trials have also raised skepticism of the safety and efficacy of vaccine trials.

2. Equitable allocation and distribution of vaccine for minority populations

Enrollment in clinical trials is just a beginning; a more significant challenge would be the vaccine’s uptake when available to the general public. We still lack a consensus on whether it is lawful for race to be an explicit criterion for priority distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. Recently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested that the vaccine amount allotted to jurisdictions might be based on critical populations recommended for vaccination by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices with input from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The NASEM framework lays out four-phased vaccine distribution approaches, emphasizing social equity by prioritizing vaccines for geographic areas identified through CDC’s social vulnerability index (SVI) or another more specific index. SVI has been a robust composite marker of minority status and language, household composition and transportation, and housing and disability, and predicted COVID-19 case counts in the United States in several studies. The National Academy of Medicine has also recommended racial minorities receive priority vaccination because they have been hard hit and are “worse off” socioeconomically.

3. Immunization uptake by minority populations

Though minority participation is crucial in developing the vaccine, more transparency, open discussions on ethical distribution, and awareness of side effects are required before vaccine approval or emergency-use authorization. Companies behind the four major COVID-19 vaccines in development have released their trials’ protocols, details on vaccine efficacy, and each product’s makeup to increase acceptance of the vaccine.

According to a recent Pew research study, about half of U.S. adults (51%) now say they would definitely or probably get a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 if it were available today. Nearly as many (49%) say they definitely or probably would not get vaccinated at this time. Intent to get a COVID-19 vaccine has fallen from 72% in May 2020, a 21–percentage point drop, and Black adults were much less likely to say they would get a vaccine than other Americans.3 This is concerning as previous studies have shown that race and ethnicity can influence immune responses to vaccination. There is evidence of racial and ethnic differences in immune response following rubella vaccination, Hib–tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine, antibody responses to the influenza A virus components of IIV3 or 4, and immune responses after measles vaccination.4-9

On the other hand, significant differences in reporting rates of adverse events after human papillomavirus vaccinations were found in different race and ethnicity groups in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.10 Thus, there is ample evidence that race and ethnicity affect responsiveness to a vaccine. Inequity in participation in a clinical trial may lead to an ineffective or one with a suboptimal response or even an unsafe vaccine.

When we look at other immunization programs, according to various surveys in recent years, non-Hispanic Blacks have lower annual vaccination rates for flu, pneumonia, and human papillomavirus vaccinations nationally, compared with non-Hispanic White adults.11 It is a cause of concern as a proportion of the population must be vaccinated to reach “community immunity” or “herd immunity” from vaccination. Depending on varying biological, environmental, and sociobehavioral factors, the threshold for COVID-19 herd immunity may be between 55% and 82% of the population.12 Hence, neither a vaccine trial nor an immunization program can succeed without participation from all communities and age groups.

Role of hospitalists

Hospitalists, who give immunizations as part of the hospital inpatient quality reporting program, are uniquely placed in this pandemic. Working on the front lines, we may encounter questions, concerns, rejections, and discussions about the pros and cons of the COVID-19 vaccine from patients.

Investigators at Children’s National Hospital and George Washington University, both in Washington, recently recommended three steps physicians and others can take now to ensure more people get the COVID-19 vaccine when it is available. Engaging frontline health professionals was one of the suggested steps to encourage more people to get the vaccine.13 However, it is imperative to understand that vaccine hesitancy might be an issue for health care providers as well, if concerns for scientific standards and involvement of diverse populations are not addressed.

We are only starting to develop a safe and effective immunization program. We must bring more to unrepresented communities than just vaccine trials. Information, education, availability, and access to the vaccines will make for a successful COVID-19 immunization program.

Dr. Saigal is a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

References

1. Moderna. COVE study. 2020 Oct 21. https://www.modernatx.com/sites/default/files/content_documents/2020-COVE-Study-Enrollment-Completion-10.22.20.pdf

2. U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: Population estimates, July 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

3. Pew Research Center. U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether To Get COVID-19 Vaccine. 2020 Sep 17. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/17/u-s-public-now-divided-over-whether-to-get-covid-19-vaccine/

4. Haralambieva IH et al. Associations between race sex and immune response variations to rubella vaccination in two independent cohorts. Vaccine. 2014;32:1946-53.

5. McQuillan GM et al. Seroprevalence of measles antibody in the U.S. population 1999-2004. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1459–64. doi: 10.1086/522866.

6. Christy C et al. Effect of gender race and parental education on immunogenicity and reported reactogenicity of acellular and whole-cell pertussis vaccines. Pediatrics. 1995;96:584-7.

7. Poland GA et al. Measles antibody seroprevalence rates among immunized Inuit Innu and Caucasian subjects. Vaccine. 1999;17:1525-31.

8. Greenberg DP et al. Immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine in young infants. The Kaiser-UCLA Vaccine Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:76-81.

9. Kurupati R et al. Race-related differences in antibody responses to the inactivated influenza vaccine are linked to distinct prevaccination gene expression profiles in blood. Oncotarget. 2016;7(39):62898-911.

10. Huang J et al. Characterization of the differential adverse event rates by race/ethnicity groups for HPV vaccine by integrating data from different sources. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:539.

11. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=22

12. Sanche S et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7).

13. American Medical Association. How to ready patients now so they’ll get a COVID-19 vaccine later. 2020 May 27. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/how-ready-patients-now-so-they-ll-get-covid-19-vaccine-later

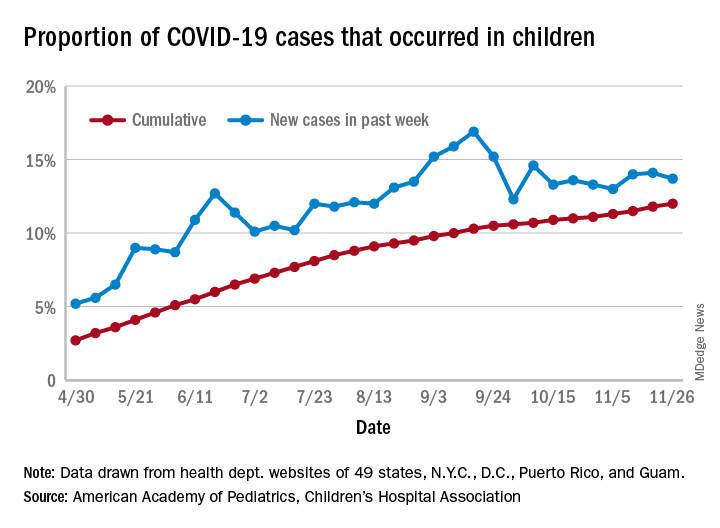

U.S. passes 1.3 million COVID-19 cases in children

The news on children and COVID-19 for Thanksgiving week does not provide a lot of room for thankfulness.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their latest weekly report.

For those not counting, the week ending Nov. 26 was the fifth in a row to show “the highest weekly increase since the pandemic began,” based on data the AAP and CHA have been collecting from 49 state health departments (New York does not report ages), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The 153,608 new cases bring the total number of COVID-19 cases in children to almost 1.34 million in those jurisdictions, which is 12% of the total number of cases (11.2 million) among all ages. For just the week ending Nov. 26, children represented 13.7% of all new cases in the United States, down from 14.1% the previous week, according to the AAP/CHA data.

Among the states reporting child cases, Florida has the lowest cumulative proportion of child cases, 6.4%, but the state is using an age range of 0-14 years (no other state goes lower than 17 years). New Jersey and Texas are next at 6.9%, although Texas “reported age for only 6% of total confirmed cases,” the AAP and CHA noted.

There are 35 states above the national number of 12.0%, the highest being Wyoming at 23.3%, followed by Tennessee at 18.3% and South Carolina at 18.2%. The two southern states are the only ones to use an age range of 0-20 years for child cases, the two groups said in this week’s report, which did not include the usual data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality because of the holiday.

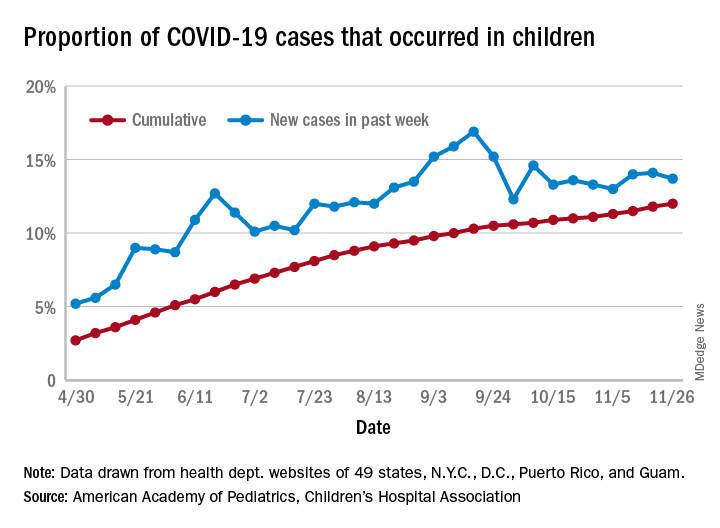

The news on children and COVID-19 for Thanksgiving week does not provide a lot of room for thankfulness.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their latest weekly report.

For those not counting, the week ending Nov. 26 was the fifth in a row to show “the highest weekly increase since the pandemic began,” based on data the AAP and CHA have been collecting from 49 state health departments (New York does not report ages), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The 153,608 new cases bring the total number of COVID-19 cases in children to almost 1.34 million in those jurisdictions, which is 12% of the total number of cases (11.2 million) among all ages. For just the week ending Nov. 26, children represented 13.7% of all new cases in the United States, down from 14.1% the previous week, according to the AAP/CHA data.

Among the states reporting child cases, Florida has the lowest cumulative proportion of child cases, 6.4%, but the state is using an age range of 0-14 years (no other state goes lower than 17 years). New Jersey and Texas are next at 6.9%, although Texas “reported age for only 6% of total confirmed cases,” the AAP and CHA noted.

There are 35 states above the national number of 12.0%, the highest being Wyoming at 23.3%, followed by Tennessee at 18.3% and South Carolina at 18.2%. The two southern states are the only ones to use an age range of 0-20 years for child cases, the two groups said in this week’s report, which did not include the usual data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality because of the holiday.

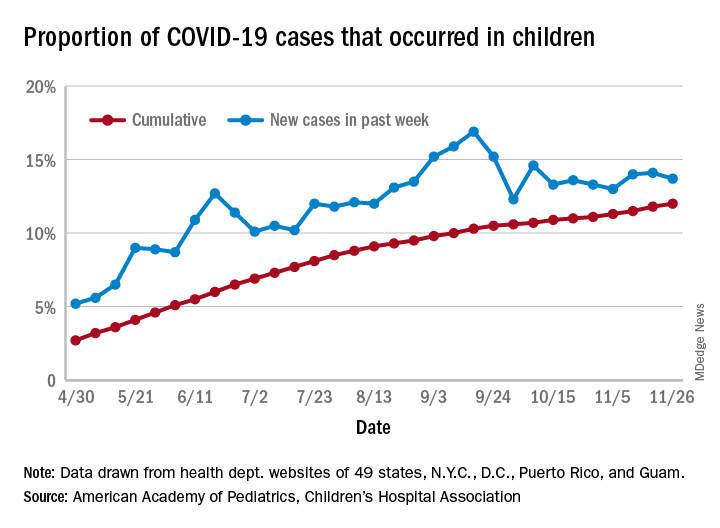

The news on children and COVID-19 for Thanksgiving week does not provide a lot of room for thankfulness.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their latest weekly report.

For those not counting, the week ending Nov. 26 was the fifth in a row to show “the highest weekly increase since the pandemic began,” based on data the AAP and CHA have been collecting from 49 state health departments (New York does not report ages), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The 153,608 new cases bring the total number of COVID-19 cases in children to almost 1.34 million in those jurisdictions, which is 12% of the total number of cases (11.2 million) among all ages. For just the week ending Nov. 26, children represented 13.7% of all new cases in the United States, down from 14.1% the previous week, according to the AAP/CHA data.

Among the states reporting child cases, Florida has the lowest cumulative proportion of child cases, 6.4%, but the state is using an age range of 0-14 years (no other state goes lower than 17 years). New Jersey and Texas are next at 6.9%, although Texas “reported age for only 6% of total confirmed cases,” the AAP and CHA noted.

There are 35 states above the national number of 12.0%, the highest being Wyoming at 23.3%, followed by Tennessee at 18.3% and South Carolina at 18.2%. The two southern states are the only ones to use an age range of 0-20 years for child cases, the two groups said in this week’s report, which did not include the usual data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality because of the holiday.

ACIP: Health workers, long-term care residents first tier for COVID-19 vaccine

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 13-1 that both groups be in the highest-priority group for vaccination. As such, ACIP recommends that both be included in phase 1a of the committee’s allocation plan.

The recommendation now goes to CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, for approval. State health departments are expected to rely on the recommendation, but ultimately can make their own decisions on how to allocate vaccine in their states.

“We hope that this vote gets us all one step closer to the day when we can all feel safe again and when this pandemic is over,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, at today’s meeting.

Health care workers are defined as paid and unpaid individuals serving in health care settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials. Long-term care residents are defined as adults who reside in facilities that provide a variety of services, including medical and personal care. Phase 1a would not include children who live in such facilities.

“Our goal in phase 1a with regard to health care personnel is to preserve the workforce and health care capacity regardless of where exposure occurs,” said ACIP panelist Grace Lee, MD, MPH, professor of paediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University. Thus vaccination would cover clinical support staff, such as nursing assistants, environmental services staff, and food support staff.

“It is crucial to maintain our health care capacity,” said ACIP member Sharon Frey, MD, clinical director at the Center for Vaccine Development at Saint Louis University. “But it’s also important to prevent severe disease and death in the group that is at highest risk of those complications and that includes those in long-term care facilities.”

CDC staff said that staff and residents in those facilities account for 6% of COVID-19 cases and 40% of deaths.

But Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., voted against putting long-term care residents into the 1a phase. “We have traditionally tried a vaccine in a young healthy population and then hope it works in our frail older adults. So we enter this realm of ‘we hope it works and that it’s safe,’ and that concerns me on many levels particularly for this vaccine,” she said, noting that the vaccines closest to FDA authorization have not been studied in elderly adults who live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities.

She added: “I have no reservations for health care workers taking this vaccine.”

Prioritization could change

The phase 1a allocation fits within the “four ethical principles” outlined by ACIP and CDC staff Nov. 23: to maximize benefits and minimize harms, promote justice, mitigate health inequities, and promote transparency.

“My vote reflects maximum benefit, minimum harm, promoting justice and mitigating the health inequalities that exist with regard to distribution of this vaccine,” said ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. Romero, chief medical officer of the Arkansas Department of Health, voted in favor of the phase 1a plan.

He and other panelists noted, however, that allocation priorities could change after the FDA reviews and authorizes a vaccine.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) will meet December 10 to review the Pfizer/BioNTech’s messenger RNA-based vaccine (BNT162b2). The companies filed for emergency use on November 20.

A second vaccine, made by Moderna, is not far behind. The company reported on Nov. 30 that its messenger RNA vaccine was 94.1% effective and filed for emergency use the same day. The FDA’s VRBPAC will review the safety and efficacy data for the Moderna vaccine on Dec. 17.

“If individual vaccines receive emergency use authorization, we will have more data to consider, and that could lead to revision of our prioritization,” said ACIP member Robert Atmar, MD, John S. Dunn Research Foundation Clinical Professor in Infectious Diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

ACIP will meet again after the Dec. 10 FDA advisory panel. But it won’t recommend a product until after the FDA has authorized it, said Amanda Cohn, MD, senior advisor for vaccines at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Staggered immunization subprioritization urged

The CDC staff said that given the potential that not enough vaccine will be available immediately, it was recommending that health care organizations plan on creating a hierarchy of prioritization within institutions. And, they also urged staggering vaccination for personnel in similar units or positions, citing potential systemic or other reactions among health care workers.

“Consider planning for personnel to have time away from clinical care if health care personnel experience systemic symptoms post vaccination,” said Sarah Oliver, MD, MSPH, from the CDC.

The CDC will soon be issuing guidance on how to handle systemic symptoms with health care workers, Dr. Oliver noted.

Some 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are expected to be available by the end of December, with 5 million to 10 million a week coming online after that, Dr. Cohn said. That means not all health care workers will be vaccinated immediately. That may require “subprioritization, but for a limited period of time,” she said.

Dr. Messonnier said that, even with limited supplies, most of the states have told the CDC that they think they can vaccinate all of their health care workers within 3 weeks – some in less time.

The ACIP allocation plan is similar to but not exactly the same as that issued by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which issued recommendations in October. That organization said that health care workers, first responders, older Americans living in congregate settings, and people with underlying health conditions should be the first to receive a vaccine.

ACIP has said that phase 1b would include essential workers, including police officers and firefighters, and those in education, transportation, and food and agriculture sectors. Phase 1c would include adults with high-risk medical conditions and those aged 65 years or older.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 13-1 that both groups be in the highest-priority group for vaccination. As such, ACIP recommends that both be included in phase 1a of the committee’s allocation plan.

The recommendation now goes to CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, for approval. State health departments are expected to rely on the recommendation, but ultimately can make their own decisions on how to allocate vaccine in their states.

“We hope that this vote gets us all one step closer to the day when we can all feel safe again and when this pandemic is over,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, at today’s meeting.

Health care workers are defined as paid and unpaid individuals serving in health care settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials. Long-term care residents are defined as adults who reside in facilities that provide a variety of services, including medical and personal care. Phase 1a would not include children who live in such facilities.

“Our goal in phase 1a with regard to health care personnel is to preserve the workforce and health care capacity regardless of where exposure occurs,” said ACIP panelist Grace Lee, MD, MPH, professor of paediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University. Thus vaccination would cover clinical support staff, such as nursing assistants, environmental services staff, and food support staff.

“It is crucial to maintain our health care capacity,” said ACIP member Sharon Frey, MD, clinical director at the Center for Vaccine Development at Saint Louis University. “But it’s also important to prevent severe disease and death in the group that is at highest risk of those complications and that includes those in long-term care facilities.”

CDC staff said that staff and residents in those facilities account for 6% of COVID-19 cases and 40% of deaths.

But Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., voted against putting long-term care residents into the 1a phase. “We have traditionally tried a vaccine in a young healthy population and then hope it works in our frail older adults. So we enter this realm of ‘we hope it works and that it’s safe,’ and that concerns me on many levels particularly for this vaccine,” she said, noting that the vaccines closest to FDA authorization have not been studied in elderly adults who live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities.

She added: “I have no reservations for health care workers taking this vaccine.”

Prioritization could change

The phase 1a allocation fits within the “four ethical principles” outlined by ACIP and CDC staff Nov. 23: to maximize benefits and minimize harms, promote justice, mitigate health inequities, and promote transparency.

“My vote reflects maximum benefit, minimum harm, promoting justice and mitigating the health inequalities that exist with regard to distribution of this vaccine,” said ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. Romero, chief medical officer of the Arkansas Department of Health, voted in favor of the phase 1a plan.

He and other panelists noted, however, that allocation priorities could change after the FDA reviews and authorizes a vaccine.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) will meet December 10 to review the Pfizer/BioNTech’s messenger RNA-based vaccine (BNT162b2). The companies filed for emergency use on November 20.

A second vaccine, made by Moderna, is not far behind. The company reported on Nov. 30 that its messenger RNA vaccine was 94.1% effective and filed for emergency use the same day. The FDA’s VRBPAC will review the safety and efficacy data for the Moderna vaccine on Dec. 17.

“If individual vaccines receive emergency use authorization, we will have more data to consider, and that could lead to revision of our prioritization,” said ACIP member Robert Atmar, MD, John S. Dunn Research Foundation Clinical Professor in Infectious Diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

ACIP will meet again after the Dec. 10 FDA advisory panel. But it won’t recommend a product until after the FDA has authorized it, said Amanda Cohn, MD, senior advisor for vaccines at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Staggered immunization subprioritization urged

The CDC staff said that given the potential that not enough vaccine will be available immediately, it was recommending that health care organizations plan on creating a hierarchy of prioritization within institutions. And, they also urged staggering vaccination for personnel in similar units or positions, citing potential systemic or other reactions among health care workers.

“Consider planning for personnel to have time away from clinical care if health care personnel experience systemic symptoms post vaccination,” said Sarah Oliver, MD, MSPH, from the CDC.

The CDC will soon be issuing guidance on how to handle systemic symptoms with health care workers, Dr. Oliver noted.

Some 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are expected to be available by the end of December, with 5 million to 10 million a week coming online after that, Dr. Cohn said. That means not all health care workers will be vaccinated immediately. That may require “subprioritization, but for a limited period of time,” she said.

Dr. Messonnier said that, even with limited supplies, most of the states have told the CDC that they think they can vaccinate all of their health care workers within 3 weeks – some in less time.

The ACIP allocation plan is similar to but not exactly the same as that issued by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which issued recommendations in October. That organization said that health care workers, first responders, older Americans living in congregate settings, and people with underlying health conditions should be the first to receive a vaccine.

ACIP has said that phase 1b would include essential workers, including police officers and firefighters, and those in education, transportation, and food and agriculture sectors. Phase 1c would include adults with high-risk medical conditions and those aged 65 years or older.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 13-1 that both groups be in the highest-priority group for vaccination. As such, ACIP recommends that both be included in phase 1a of the committee’s allocation plan.

The recommendation now goes to CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, for approval. State health departments are expected to rely on the recommendation, but ultimately can make their own decisions on how to allocate vaccine in their states.

“We hope that this vote gets us all one step closer to the day when we can all feel safe again and when this pandemic is over,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, at today’s meeting.

Health care workers are defined as paid and unpaid individuals serving in health care settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials. Long-term care residents are defined as adults who reside in facilities that provide a variety of services, including medical and personal care. Phase 1a would not include children who live in such facilities.

“Our goal in phase 1a with regard to health care personnel is to preserve the workforce and health care capacity regardless of where exposure occurs,” said ACIP panelist Grace Lee, MD, MPH, professor of paediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University. Thus vaccination would cover clinical support staff, such as nursing assistants, environmental services staff, and food support staff.

“It is crucial to maintain our health care capacity,” said ACIP member Sharon Frey, MD, clinical director at the Center for Vaccine Development at Saint Louis University. “But it’s also important to prevent severe disease and death in the group that is at highest risk of those complications and that includes those in long-term care facilities.”

CDC staff said that staff and residents in those facilities account for 6% of COVID-19 cases and 40% of deaths.

But Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., voted against putting long-term care residents into the 1a phase. “We have traditionally tried a vaccine in a young healthy population and then hope it works in our frail older adults. So we enter this realm of ‘we hope it works and that it’s safe,’ and that concerns me on many levels particularly for this vaccine,” she said, noting that the vaccines closest to FDA authorization have not been studied in elderly adults who live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities.

She added: “I have no reservations for health care workers taking this vaccine.”

Prioritization could change

The phase 1a allocation fits within the “four ethical principles” outlined by ACIP and CDC staff Nov. 23: to maximize benefits and minimize harms, promote justice, mitigate health inequities, and promote transparency.

“My vote reflects maximum benefit, minimum harm, promoting justice and mitigating the health inequalities that exist with regard to distribution of this vaccine,” said ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. Romero, chief medical officer of the Arkansas Department of Health, voted in favor of the phase 1a plan.

He and other panelists noted, however, that allocation priorities could change after the FDA reviews and authorizes a vaccine.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) will meet December 10 to review the Pfizer/BioNTech’s messenger RNA-based vaccine (BNT162b2). The companies filed for emergency use on November 20.

A second vaccine, made by Moderna, is not far behind. The company reported on Nov. 30 that its messenger RNA vaccine was 94.1% effective and filed for emergency use the same day. The FDA’s VRBPAC will review the safety and efficacy data for the Moderna vaccine on Dec. 17.

“If individual vaccines receive emergency use authorization, we will have more data to consider, and that could lead to revision of our prioritization,” said ACIP member Robert Atmar, MD, John S. Dunn Research Foundation Clinical Professor in Infectious Diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

ACIP will meet again after the Dec. 10 FDA advisory panel. But it won’t recommend a product until after the FDA has authorized it, said Amanda Cohn, MD, senior advisor for vaccines at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Staggered immunization subprioritization urged

The CDC staff said that given the potential that not enough vaccine will be available immediately, it was recommending that health care organizations plan on creating a hierarchy of prioritization within institutions. And, they also urged staggering vaccination for personnel in similar units or positions, citing potential systemic or other reactions among health care workers.

“Consider planning for personnel to have time away from clinical care if health care personnel experience systemic symptoms post vaccination,” said Sarah Oliver, MD, MSPH, from the CDC.

The CDC will soon be issuing guidance on how to handle systemic symptoms with health care workers, Dr. Oliver noted.

Some 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are expected to be available by the end of December, with 5 million to 10 million a week coming online after that, Dr. Cohn said. That means not all health care workers will be vaccinated immediately. That may require “subprioritization, but for a limited period of time,” she said.

Dr. Messonnier said that, even with limited supplies, most of the states have told the CDC that they think they can vaccinate all of their health care workers within 3 weeks – some in less time.

The ACIP allocation plan is similar to but not exactly the same as that issued by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which issued recommendations in October. That organization said that health care workers, first responders, older Americans living in congregate settings, and people with underlying health conditions should be the first to receive a vaccine.

ACIP has said that phase 1b would include essential workers, including police officers and firefighters, and those in education, transportation, and food and agriculture sectors. Phase 1c would include adults with high-risk medical conditions and those aged 65 years or older.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What to do when anticoagulation fails cancer patients

When a patient with cancer develops venous thromboembolism despite anticoagulation, how to help them comes down to clinical judgment, according to hematologist Neil Zakai, MD, associate professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

“Unfortunately,” when it comes to “anticoagulation failure, we are entering an evidence free-zone,” with no large trials to guide management and only a few guiding principles, he said during his presentation at the 2020 Update in Nonneoplastic Hematology virtual conference.

The first thing is to check if there was an inciting incident, such as medical noncompliance, an infection, or an interruption of anticoagulation. Dr. Zakai said he’s even had cancer patients develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia when switched to enoxaparin from a direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) for a procedure.

Once the underlying problem is addressed, patients may be able to continue with their original anticoagulant.

However, cancer progression is the main reason anticoagulation fails. “In general, it is very difficult to control cancer thrombosis if you can’t control cancer progression,” Dr. Zakai said.

In those cases, he steps up anticoagulation. Prophylactic dosing is increased to full treatment dosing, and patients on a DOAC are generally switched to a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).

If patients are already on LMWH once daily, they will be bumped up to twice daily dosing; for instance, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg b.i.d. instead of 1.5 mg/kg q.d. Dr. Zakai said he’s gone as high at 2 or even 2.5 mg/kg to control thrombosis, without excessive bleeding.

In general, anticoagulation for thrombosis prophylaxis continues as long as the cancer is active, and certainly while patients are on hormonal treatments such as tamoxifen, which increases the risk.

Dr. Zakai stressed that both thrombosis and bleeding risk change for cancer patients over time, and treatment needs to keep up.

“I continuously assess the risk and benefit of anticoagulation. At certain times” such as during and for a few months after hospitalization, thrombosis risk increases; at other times, bleeding risk is higher. “You need to actively change your anticoagulation during those periods,” and tailor therapy based on transient risk factors. “People with cancer have peaks and troughs for their risk that we don’t take advantage of,” he said.

Dr. Zakai generally favors apixaban or enoxaparin for prophylaxis, carefully monitoring patients for bleeding and, for the DOAC, drug interactions with antiemetics, dexamethasone, and certain chemotherapy drugs.

He noted a recent trial that found a 59% reduction in venous thromboembolism risk in ambulatory cancer patients with apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily over 6 months, versus placebo, and a 6% absolute reduction, but at the cost of a twofold increase in bleeding risk, with an absolute 1.7% increase.

Dr. Zakai cautioned that patients in trials are selected for higher VTE and lower bleeding risks, so outcomes might “poorly reflect real world populations.” Dr. Zakai did not have any industry disclosures. The conference was sponsored by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

When a patient with cancer develops venous thromboembolism despite anticoagulation, how to help them comes down to clinical judgment, according to hematologist Neil Zakai, MD, associate professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

“Unfortunately,” when it comes to “anticoagulation failure, we are entering an evidence free-zone,” with no large trials to guide management and only a few guiding principles, he said during his presentation at the 2020 Update in Nonneoplastic Hematology virtual conference.

The first thing is to check if there was an inciting incident, such as medical noncompliance, an infection, or an interruption of anticoagulation. Dr. Zakai said he’s even had cancer patients develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia when switched to enoxaparin from a direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) for a procedure.

Once the underlying problem is addressed, patients may be able to continue with their original anticoagulant.

However, cancer progression is the main reason anticoagulation fails. “In general, it is very difficult to control cancer thrombosis if you can’t control cancer progression,” Dr. Zakai said.

In those cases, he steps up anticoagulation. Prophylactic dosing is increased to full treatment dosing, and patients on a DOAC are generally switched to a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).

If patients are already on LMWH once daily, they will be bumped up to twice daily dosing; for instance, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg b.i.d. instead of 1.5 mg/kg q.d. Dr. Zakai said he’s gone as high at 2 or even 2.5 mg/kg to control thrombosis, without excessive bleeding.

In general, anticoagulation for thrombosis prophylaxis continues as long as the cancer is active, and certainly while patients are on hormonal treatments such as tamoxifen, which increases the risk.

Dr. Zakai stressed that both thrombosis and bleeding risk change for cancer patients over time, and treatment needs to keep up.

“I continuously assess the risk and benefit of anticoagulation. At certain times” such as during and for a few months after hospitalization, thrombosis risk increases; at other times, bleeding risk is higher. “You need to actively change your anticoagulation during those periods,” and tailor therapy based on transient risk factors. “People with cancer have peaks and troughs for their risk that we don’t take advantage of,” he said.

Dr. Zakai generally favors apixaban or enoxaparin for prophylaxis, carefully monitoring patients for bleeding and, for the DOAC, drug interactions with antiemetics, dexamethasone, and certain chemotherapy drugs.

He noted a recent trial that found a 59% reduction in venous thromboembolism risk in ambulatory cancer patients with apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily over 6 months, versus placebo, and a 6% absolute reduction, but at the cost of a twofold increase in bleeding risk, with an absolute 1.7% increase.

Dr. Zakai cautioned that patients in trials are selected for higher VTE and lower bleeding risks, so outcomes might “poorly reflect real world populations.” Dr. Zakai did not have any industry disclosures. The conference was sponsored by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

When a patient with cancer develops venous thromboembolism despite anticoagulation, how to help them comes down to clinical judgment, according to hematologist Neil Zakai, MD, associate professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

“Unfortunately,” when it comes to “anticoagulation failure, we are entering an evidence free-zone,” with no large trials to guide management and only a few guiding principles, he said during his presentation at the 2020 Update in Nonneoplastic Hematology virtual conference.

The first thing is to check if there was an inciting incident, such as medical noncompliance, an infection, or an interruption of anticoagulation. Dr. Zakai said he’s even had cancer patients develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia when switched to enoxaparin from a direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) for a procedure.

Once the underlying problem is addressed, patients may be able to continue with their original anticoagulant.

However, cancer progression is the main reason anticoagulation fails. “In general, it is very difficult to control cancer thrombosis if you can’t control cancer progression,” Dr. Zakai said.

In those cases, he steps up anticoagulation. Prophylactic dosing is increased to full treatment dosing, and patients on a DOAC are generally switched to a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).

If patients are already on LMWH once daily, they will be bumped up to twice daily dosing; for instance, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg b.i.d. instead of 1.5 mg/kg q.d. Dr. Zakai said he’s gone as high at 2 or even 2.5 mg/kg to control thrombosis, without excessive bleeding.

In general, anticoagulation for thrombosis prophylaxis continues as long as the cancer is active, and certainly while patients are on hormonal treatments such as tamoxifen, which increases the risk.

Dr. Zakai stressed that both thrombosis and bleeding risk change for cancer patients over time, and treatment needs to keep up.

“I continuously assess the risk and benefit of anticoagulation. At certain times” such as during and for a few months after hospitalization, thrombosis risk increases; at other times, bleeding risk is higher. “You need to actively change your anticoagulation during those periods,” and tailor therapy based on transient risk factors. “People with cancer have peaks and troughs for their risk that we don’t take advantage of,” he said.

Dr. Zakai generally favors apixaban or enoxaparin for prophylaxis, carefully monitoring patients for bleeding and, for the DOAC, drug interactions with antiemetics, dexamethasone, and certain chemotherapy drugs.

He noted a recent trial that found a 59% reduction in venous thromboembolism risk in ambulatory cancer patients with apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily over 6 months, versus placebo, and a 6% absolute reduction, but at the cost of a twofold increase in bleeding risk, with an absolute 1.7% increase.

Dr. Zakai cautioned that patients in trials are selected for higher VTE and lower bleeding risks, so outcomes might “poorly reflect real world populations.” Dr. Zakai did not have any industry disclosures. The conference was sponsored by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM 2020 UNNH

CMS launches hospital-at-home program to free up hospital capacity

As an increasing number of health systems implement “hospital-at-home” (HaH) programs to increase their traditional hospital capacity, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has given the movement a boost by changing its regulations to allow acute care to be provided in a patient’s home under certain conditions.

The CMS announced Nov. 25 that it was launching its Acute Hospital Care at Home program “to increase the capacity of the American health care system” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the same time, the agency announced it was giving more flexibility to ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) to provide hospital-level care.

The CMS said its new HaH program is an expansion of the Hospitals Without Walls initiative that was unveiled last March. Hospitals Without Walls is a set of “temporary new rules” that provide flexibility for hospitals to provide acute care outside of inpatient settings. Under those rules, hospitals are able to transfer patients to outside facilities, such as ASCs, inpatient rehabilitation hospitals, hotels, and dormitories, while still receiving Medicare hospital payments.

Under CMS’ new Acute Hospital Care at Home, which is not described as temporary, patients can be transferred from emergency departments or inpatient wards to hospital-level care at home. The CMS said the HaH program is designed for people with conditions such as the acute phases of asthma, heart failure, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Altogether, the agency said, more than 60 acute conditions can be treated safely at home.

However, the agency didn’t say that facilities can’t admit COVID-19 patients to the hospital at home. Rami Karjian, MBA, cofounder and CEO of Medically Home, a firm that supplies health systems with technical services and software for HaH programs, said in an interview that several Medically Home clients plan to treat both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients at home when they begin to participate in the CMS program in the near future.

The CMS said it consulted extensively with academic and private industry leaders in building its HaH program. Before rolling out the initiative, the agency noted, it conducted successful pilot programs in leading hospitals and health systems. The results of some of these pilots have been reported in academic journals.

Participating hospitals will be required to have specified screening protocols in place before beginning acute care at home, the CMS announced. An in-person physician evaluation will be required before starting care at home. A nurse will evaluate each patient once daily in person or remotely, and either nurses or paramedics will visit the patient in person twice a day.

In contrast, Medicare regulations require nursing staff to be available around the clock in traditional hospitals. So the CMS has to grant waivers to hospitals for HaH programs.

While not going into detail on the telemonitoring capabilities that will be required in the acute hospital care at home, the release said, “Today’s announcement builds upon the critical work by CMS to expand telehealth coverage to keep beneficiaries safe and prevent the spread of COVID-19.”

More flexibility for ASCs

The agency is also giving ASCs the flexibility to provide 24-hour nursing services only when one or more patients are receiving care on site. This flexibility will be available to any of the 5,700 ASCs that wish to participate, and will be immediately effective for the 85 ASCs currently participating in the Hospital Without Walls initiative, the CMS said.

The new ASC regulations, the CMS said, are aimed at allowing communities “to maintain surgical capacity and other life-saving non-COVID-19 [care], like cancer surgeries.” Patients who need such procedures will be able to receive them in ASCs without being exposed to known COVID-19 cases.

Similarly, the CMS said patients and families not diagnosed with COVID-19 may prefer to receive acute care at home if local hospitals are full of COVID-19 patients. In addition, the CMS said it anticipates patients may value the ability to be treated at home without the visitation restrictions of hospitals.

Early HaH participants

Six health systems with extensive experience in providing acute hospital care at home have been approved for the new HaH waivers from Medicare rules. They include Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Massachusetts); Huntsman Cancer Institute (Utah); Massachusetts General Hospital (Massachusetts); Mount Sinai Health System (New York City); Presbyterian Healthcare Services (New Mexico); and UnityPoint Health (Iowa).

The CMS said that it’s in discussions with other health care systems and expects new applications to be submitted soon.

To support these efforts, the CMS has launched an online portal to streamline the waiver request process. The agency said it will closely monitor the program to safeguard beneficiaries and will require participating hospitals to report quality and safety data on a regular basis.

Support from hospitals

The first health systems participating in the CMS HaH appear to be supportive of the program, with some hospital leaders submitting comments to the CMS about their view of the initiative.