User login

What’s under my toenail?

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

A 13-year-old female was seen by her pediatrician for a lesion that had been on her right toe for about 6 months. She is unaware of any trauma to the area. The lesion has been growing slowly and recently it started lifting up the nail, became tender, and was bleeding, which is the reason why she sought care.

At the pediatrician's office, he noted a pink crusted papule under the nail. The nail was lifting up and was tender to the touch. She is a healthy girl who is not taking any medications and has no allergies. There is no family history of similar lesions.

The pediatrician took a picture of the lesion and he send it to our pediatric teledermatology service for consultation.

Shedding the super-doctor myth requires an honest look at systemic racism

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Outstanding medical bills: Dealing with deadbeats

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have received a growing number of inquiries about collection issues. For a variety of reasons, many patients seem increasingly reluctant to pay their medical bills. I’ve written many columns on keeping credit card numbers on file, and other techniques for keeping your accounts receivable in check; but despite your best efforts, there will always be a few deadbeats that you will need to pursue.

For the record, I am not speaking about patients who lost income due to the pandemic and are now struggling with debts, or otherwise have fallen on hard times and are unable to pay.

The worst kinds of deadbeats are the ones who rob you twice; they accept payments from insurance companies and keep them. Such crooks must be pursued aggressively, with all the means at your disposal; but to reiterate the point I’ve tried to drive home repeatedly, the best cure is prevention.

You already know that you should collect as many fees as possible at the time of service. For cosmetic procedures you should require a substantial deposit in advance, with the balance due at the time of service. When that is impossible, maximize the chances you will be paid by making sure all available payment mechanisms are in place.

With my credit-card-on-file system that I’ve described many times, patients who fail to pay their credit card bill are the credit card company’s problem, not yours. In cases where you suspect fees might exceed credit card limits, you can arrange a realistic payment schedule in advance and have the patient fill out a credit application. You can find forms for this online at formswift.com, templates.office.com, and many other websites.

In some cases, it may be worth the trouble to run a background check. There are easy and affordable ways to do this. Dunn & Bradstreet, for example, will furnish a report containing payment records and details of any lawsuits, liens, and other legal actions for a nominal fee. The more financial information you have on file, the more leverage you have if a patient later balks at paying his or her balance.

For cosmetic work, always take before and after photos, and have all patients sign a written consent giving permission for the procedure, assuming full financial responsibility, and acknowledging that no guarantees have been given or implied. This defuses the common deadbeat tactics of claiming ignorance of personal financial obligations and professing dissatisfaction with the results.

Despite all your precautions, a deadbeat will inevitably slip through on occasion; but even then, you have options for extracting payment. Collection agencies are the traditional first line of attack for most medical practices. Ideally, your agency should specialize in handling medical accounts, so it will know exactly how much pressure to exert to avoid charges of harassment. Delinquent accounts should be submitted earlier rather than later to maximize the chances of success; my manager never allows an account to age more than 90 days, and if circumstances dictate, she refers them sooner than that.

When collection agencies fail, think about small claims court. You will need to learn the rules in your state, but in most states there is a small filing fee and a limit of $5,000 or so on claims. No attorneys are involved. If your paperwork is in order, the court will nearly always rule in your favor, but it will not provide the means for actual collection. In other words, you will still have to persuade the deadbeat to pay up. However, in many states a court order will give you the authority to attach a lien to property, or garnish wages, which often provides enough leverage to force payment.

What about those double-deadbeats who keep the insurance checks for themselves? First, check your third-party contract; sometimes the insurance company or HMO will be compelled to pay you directly and then go after the patient to get back its money. (They won’t volunteer this service, however – you’ll have to ask for it.)

If that’s not an option, consider reporting the misdirected payment to the Internal Revenue Service as income to the patient, by submitting a 1099 Miscellaneous Income form. Be sure to notify the deadbeat that you will be doing this. Sometimes the threat of such action will convince the individual to pay up; if not, at least you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing he or she will have to pay taxes on the money.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have received a growing number of inquiries about collection issues. For a variety of reasons, many patients seem increasingly reluctant to pay their medical bills. I’ve written many columns on keeping credit card numbers on file, and other techniques for keeping your accounts receivable in check; but despite your best efforts, there will always be a few deadbeats that you will need to pursue.

For the record, I am not speaking about patients who lost income due to the pandemic and are now struggling with debts, or otherwise have fallen on hard times and are unable to pay.

The worst kinds of deadbeats are the ones who rob you twice; they accept payments from insurance companies and keep them. Such crooks must be pursued aggressively, with all the means at your disposal; but to reiterate the point I’ve tried to drive home repeatedly, the best cure is prevention.

You already know that you should collect as many fees as possible at the time of service. For cosmetic procedures you should require a substantial deposit in advance, with the balance due at the time of service. When that is impossible, maximize the chances you will be paid by making sure all available payment mechanisms are in place.

With my credit-card-on-file system that I’ve described many times, patients who fail to pay their credit card bill are the credit card company’s problem, not yours. In cases where you suspect fees might exceed credit card limits, you can arrange a realistic payment schedule in advance and have the patient fill out a credit application. You can find forms for this online at formswift.com, templates.office.com, and many other websites.

In some cases, it may be worth the trouble to run a background check. There are easy and affordable ways to do this. Dunn & Bradstreet, for example, will furnish a report containing payment records and details of any lawsuits, liens, and other legal actions for a nominal fee. The more financial information you have on file, the more leverage you have if a patient later balks at paying his or her balance.

For cosmetic work, always take before and after photos, and have all patients sign a written consent giving permission for the procedure, assuming full financial responsibility, and acknowledging that no guarantees have been given or implied. This defuses the common deadbeat tactics of claiming ignorance of personal financial obligations and professing dissatisfaction with the results.

Despite all your precautions, a deadbeat will inevitably slip through on occasion; but even then, you have options for extracting payment. Collection agencies are the traditional first line of attack for most medical practices. Ideally, your agency should specialize in handling medical accounts, so it will know exactly how much pressure to exert to avoid charges of harassment. Delinquent accounts should be submitted earlier rather than later to maximize the chances of success; my manager never allows an account to age more than 90 days, and if circumstances dictate, she refers them sooner than that.

When collection agencies fail, think about small claims court. You will need to learn the rules in your state, but in most states there is a small filing fee and a limit of $5,000 or so on claims. No attorneys are involved. If your paperwork is in order, the court will nearly always rule in your favor, but it will not provide the means for actual collection. In other words, you will still have to persuade the deadbeat to pay up. However, in many states a court order will give you the authority to attach a lien to property, or garnish wages, which often provides enough leverage to force payment.

What about those double-deadbeats who keep the insurance checks for themselves? First, check your third-party contract; sometimes the insurance company or HMO will be compelled to pay you directly and then go after the patient to get back its money. (They won’t volunteer this service, however – you’ll have to ask for it.)

If that’s not an option, consider reporting the misdirected payment to the Internal Revenue Service as income to the patient, by submitting a 1099 Miscellaneous Income form. Be sure to notify the deadbeat that you will be doing this. Sometimes the threat of such action will convince the individual to pay up; if not, at least you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing he or she will have to pay taxes on the money.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have received a growing number of inquiries about collection issues. For a variety of reasons, many patients seem increasingly reluctant to pay their medical bills. I’ve written many columns on keeping credit card numbers on file, and other techniques for keeping your accounts receivable in check; but despite your best efforts, there will always be a few deadbeats that you will need to pursue.

For the record, I am not speaking about patients who lost income due to the pandemic and are now struggling with debts, or otherwise have fallen on hard times and are unable to pay.

The worst kinds of deadbeats are the ones who rob you twice; they accept payments from insurance companies and keep them. Such crooks must be pursued aggressively, with all the means at your disposal; but to reiterate the point I’ve tried to drive home repeatedly, the best cure is prevention.

You already know that you should collect as many fees as possible at the time of service. For cosmetic procedures you should require a substantial deposit in advance, with the balance due at the time of service. When that is impossible, maximize the chances you will be paid by making sure all available payment mechanisms are in place.

With my credit-card-on-file system that I’ve described many times, patients who fail to pay their credit card bill are the credit card company’s problem, not yours. In cases where you suspect fees might exceed credit card limits, you can arrange a realistic payment schedule in advance and have the patient fill out a credit application. You can find forms for this online at formswift.com, templates.office.com, and many other websites.

In some cases, it may be worth the trouble to run a background check. There are easy and affordable ways to do this. Dunn & Bradstreet, for example, will furnish a report containing payment records and details of any lawsuits, liens, and other legal actions for a nominal fee. The more financial information you have on file, the more leverage you have if a patient later balks at paying his or her balance.

For cosmetic work, always take before and after photos, and have all patients sign a written consent giving permission for the procedure, assuming full financial responsibility, and acknowledging that no guarantees have been given or implied. This defuses the common deadbeat tactics of claiming ignorance of personal financial obligations and professing dissatisfaction with the results.

Despite all your precautions, a deadbeat will inevitably slip through on occasion; but even then, you have options for extracting payment. Collection agencies are the traditional first line of attack for most medical practices. Ideally, your agency should specialize in handling medical accounts, so it will know exactly how much pressure to exert to avoid charges of harassment. Delinquent accounts should be submitted earlier rather than later to maximize the chances of success; my manager never allows an account to age more than 90 days, and if circumstances dictate, she refers them sooner than that.

When collection agencies fail, think about small claims court. You will need to learn the rules in your state, but in most states there is a small filing fee and a limit of $5,000 or so on claims. No attorneys are involved. If your paperwork is in order, the court will nearly always rule in your favor, but it will not provide the means for actual collection. In other words, you will still have to persuade the deadbeat to pay up. However, in many states a court order will give you the authority to attach a lien to property, or garnish wages, which often provides enough leverage to force payment.

What about those double-deadbeats who keep the insurance checks for themselves? First, check your third-party contract; sometimes the insurance company or HMO will be compelled to pay you directly and then go after the patient to get back its money. (They won’t volunteer this service, however – you’ll have to ask for it.)

If that’s not an option, consider reporting the misdirected payment to the Internal Revenue Service as income to the patient, by submitting a 1099 Miscellaneous Income form. Be sure to notify the deadbeat that you will be doing this. Sometimes the threat of such action will convince the individual to pay up; if not, at least you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing he or she will have to pay taxes on the money.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Universal masking is the key to safe school attendance

“I want my child to go back to school,” the mother said to me. “I just want you to tell me it will be safe.”

As the summer break winds down for children across the United States, pediatric COVID-19 cases are rising. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, nearly 94,000 cases were reported for the week ending Aug. 5, more than double the case count from 2 weeks earlier.1

Anecdotally, some children’s hospitals are reporting an increase in pediatric COVID-19 admissions. In the hospital in which I practice, we are seeing numbers similar to those we saw in December and January: a typical daily census of 10 kids admitted with COVID-19, with 4 of them in the intensive care unit. It is a stark contrast to June when, most days, we had no patients with COVID-19 in the hospital. About half of our hospitalized patients are too young to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while the rest are unvaccinated children 12 years and older.

Vaccination of eligible children and teachers is an essential strategy for preventing the spread of COVID-19 in schools, but as children head back to school, immunization rates of educators are largely unknown and are suboptimal among students in most states. As of Aug. 11, 10.7 million U.S. children had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, representing 43% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 53% of 16- to 17-year-olds.2 Rates vary substantially by state, with more than 70% of kids in Vermont receiving at least one dose of vaccine, compared with less than 25% in Wyoming and Alabama.

Still, in the absence of robust immunization rates, we have data that schools can still reopen successfully. We need to follow the science and implement universal masking, a safe, effective, and practical mitigation strategy.

It worked in Wisconsin. Seventeen K-12 schools in rural Wisconsin opened last fall for in-person instruction.3 Reported compliance with masking was high, ranging from 92.1% to 97.4%, and in-school transmission of COVID-19 was low, with seven cases among 4,876 students.

It worked in Salt Lake City.4 In 20 elementary schools open for in-person instruction Dec. 3, 2020, to Jan. 31, 2021, compliance with mask-wearing was high and in-school transmission was very low, despite a high community incidence of COVID-19. Notably, students’ classroom seats were less than 6 feet apart, suggesting that consistent mask-wearing works even when physical distancing is challenging.

One of the best examples of successful school reopening happened in North Carolina, where pediatricians, pediatric infectious disease specialists, and other experts affiliated with Duke University formed the ABC Science Collaborative to support school districts that requested scientific input to help guide return-to-school policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. From Oct. 26, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021, the ABC Science Collaborative worked with 13 school districts that were open for in-person instruction using basic mitigation strategies, including universal masking.5 During this time period, there were 4,969 community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infections in the more than 100,000 students and staff present in schools. Transmission to school contacts was identified in only 209 individuals for a secondary attack rate of less than 1%.

Duke investigator Kanecia Zimmerman, MD, told Duke Today, “We know that, if our goal is to reduce transmission of COVID-19 in schools, there are two effective ways to do that: 1. vaccination, 2. masking. In the setting of schools ... the science suggests masking can be extremely effective, particularly for those who can’t get vaccinated while COVID-19 is still circulating.”

Both the AAP6 and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society7 have emphasized the importance of in-person instruction and endorsed universal masking in school. Mask-optional policies or “mask-if-you-are-unvaccinated” policies don’t work, as we have seen in society at large. They are likely to be especially challenging in school settings. Given an option, many, if not most kids, will take off their masks. Kids who leave them on run the risk of stigmatization or bullying.

On Aug. 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance to recommend universal indoor masking for all students, staff, teachers, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Now we’ll have to wait and see if school districts, elected officials, and parents will get on board with masks. ... and we’ll be left to count the number of rising COVID-19 cases that occur until they do.

Case in point: Kids in Greater Clark County, Ind., headed back to school on July 28. Masks were not required on school property, although unvaccinated students and teachers were “strongly encouraged” to wear them.8

Over the first 8 days of in-person instruction, schools in Greater Clark County identified 70 cases of COVID-19 in students and quarantined more than 1,100 of the district’s 10,300 students. Only the unvaccinated were required to quarantine. The district began requiring masks in all school buildings on Aug. 9.9

The worried mother had one last question for me. “What’s the best mask for a child to wear?” For most kids, a simple, well-fitting cloth mask is fine. The best mask is ultimately the mask a child will wear. A toolkit with practical tips for helping children successfully wear a mask is available on the ABC Science Collaborative website.

Dr. Bryant, president of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, is a pediatrician at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. “Children and COVID-19: State-level data report.”

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. “Children and COVID-19 vaccination trends.”

3. Falk A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:136-40.

4. Hershow RB et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:442-8.

5. Zimmerman KO et al. Pediatrics. 2021 Jul;e2021052686. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052686.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics. “American Academy of Pediatrics updates recommendations for opening schools in fall 2021.”

7. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. “PIDS supports universal masking for students, school staff.”

8. Courtney Hayden. WHAS11. “Greater Clark County Schools return to class July 28.”

9. Dustin Vogt. WAVE3 News. “Greater Clark Country Schools to require masks amid 70 positive cases.”

“I want my child to go back to school,” the mother said to me. “I just want you to tell me it will be safe.”

As the summer break winds down for children across the United States, pediatric COVID-19 cases are rising. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, nearly 94,000 cases were reported for the week ending Aug. 5, more than double the case count from 2 weeks earlier.1

Anecdotally, some children’s hospitals are reporting an increase in pediatric COVID-19 admissions. In the hospital in which I practice, we are seeing numbers similar to those we saw in December and January: a typical daily census of 10 kids admitted with COVID-19, with 4 of them in the intensive care unit. It is a stark contrast to June when, most days, we had no patients with COVID-19 in the hospital. About half of our hospitalized patients are too young to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while the rest are unvaccinated children 12 years and older.

Vaccination of eligible children and teachers is an essential strategy for preventing the spread of COVID-19 in schools, but as children head back to school, immunization rates of educators are largely unknown and are suboptimal among students in most states. As of Aug. 11, 10.7 million U.S. children had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, representing 43% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 53% of 16- to 17-year-olds.2 Rates vary substantially by state, with more than 70% of kids in Vermont receiving at least one dose of vaccine, compared with less than 25% in Wyoming and Alabama.

Still, in the absence of robust immunization rates, we have data that schools can still reopen successfully. We need to follow the science and implement universal masking, a safe, effective, and practical mitigation strategy.

It worked in Wisconsin. Seventeen K-12 schools in rural Wisconsin opened last fall for in-person instruction.3 Reported compliance with masking was high, ranging from 92.1% to 97.4%, and in-school transmission of COVID-19 was low, with seven cases among 4,876 students.

It worked in Salt Lake City.4 In 20 elementary schools open for in-person instruction Dec. 3, 2020, to Jan. 31, 2021, compliance with mask-wearing was high and in-school transmission was very low, despite a high community incidence of COVID-19. Notably, students’ classroom seats were less than 6 feet apart, suggesting that consistent mask-wearing works even when physical distancing is challenging.

One of the best examples of successful school reopening happened in North Carolina, where pediatricians, pediatric infectious disease specialists, and other experts affiliated with Duke University formed the ABC Science Collaborative to support school districts that requested scientific input to help guide return-to-school policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. From Oct. 26, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021, the ABC Science Collaborative worked with 13 school districts that were open for in-person instruction using basic mitigation strategies, including universal masking.5 During this time period, there were 4,969 community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infections in the more than 100,000 students and staff present in schools. Transmission to school contacts was identified in only 209 individuals for a secondary attack rate of less than 1%.

Duke investigator Kanecia Zimmerman, MD, told Duke Today, “We know that, if our goal is to reduce transmission of COVID-19 in schools, there are two effective ways to do that: 1. vaccination, 2. masking. In the setting of schools ... the science suggests masking can be extremely effective, particularly for those who can’t get vaccinated while COVID-19 is still circulating.”

Both the AAP6 and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society7 have emphasized the importance of in-person instruction and endorsed universal masking in school. Mask-optional policies or “mask-if-you-are-unvaccinated” policies don’t work, as we have seen in society at large. They are likely to be especially challenging in school settings. Given an option, many, if not most kids, will take off their masks. Kids who leave them on run the risk of stigmatization or bullying.

On Aug. 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance to recommend universal indoor masking for all students, staff, teachers, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Now we’ll have to wait and see if school districts, elected officials, and parents will get on board with masks. ... and we’ll be left to count the number of rising COVID-19 cases that occur until they do.

Case in point: Kids in Greater Clark County, Ind., headed back to school on July 28. Masks were not required on school property, although unvaccinated students and teachers were “strongly encouraged” to wear them.8

Over the first 8 days of in-person instruction, schools in Greater Clark County identified 70 cases of COVID-19 in students and quarantined more than 1,100 of the district’s 10,300 students. Only the unvaccinated were required to quarantine. The district began requiring masks in all school buildings on Aug. 9.9

The worried mother had one last question for me. “What’s the best mask for a child to wear?” For most kids, a simple, well-fitting cloth mask is fine. The best mask is ultimately the mask a child will wear. A toolkit with practical tips for helping children successfully wear a mask is available on the ABC Science Collaborative website.

Dr. Bryant, president of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, is a pediatrician at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. “Children and COVID-19: State-level data report.”

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. “Children and COVID-19 vaccination trends.”

3. Falk A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:136-40.

4. Hershow RB et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:442-8.

5. Zimmerman KO et al. Pediatrics. 2021 Jul;e2021052686. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052686.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics. “American Academy of Pediatrics updates recommendations for opening schools in fall 2021.”

7. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. “PIDS supports universal masking for students, school staff.”

8. Courtney Hayden. WHAS11. “Greater Clark County Schools return to class July 28.”

9. Dustin Vogt. WAVE3 News. “Greater Clark Country Schools to require masks amid 70 positive cases.”

“I want my child to go back to school,” the mother said to me. “I just want you to tell me it will be safe.”

As the summer break winds down for children across the United States, pediatric COVID-19 cases are rising. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, nearly 94,000 cases were reported for the week ending Aug. 5, more than double the case count from 2 weeks earlier.1

Anecdotally, some children’s hospitals are reporting an increase in pediatric COVID-19 admissions. In the hospital in which I practice, we are seeing numbers similar to those we saw in December and January: a typical daily census of 10 kids admitted with COVID-19, with 4 of them in the intensive care unit. It is a stark contrast to June when, most days, we had no patients with COVID-19 in the hospital. About half of our hospitalized patients are too young to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while the rest are unvaccinated children 12 years and older.

Vaccination of eligible children and teachers is an essential strategy for preventing the spread of COVID-19 in schools, but as children head back to school, immunization rates of educators are largely unknown and are suboptimal among students in most states. As of Aug. 11, 10.7 million U.S. children had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, representing 43% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 53% of 16- to 17-year-olds.2 Rates vary substantially by state, with more than 70% of kids in Vermont receiving at least one dose of vaccine, compared with less than 25% in Wyoming and Alabama.

Still, in the absence of robust immunization rates, we have data that schools can still reopen successfully. We need to follow the science and implement universal masking, a safe, effective, and practical mitigation strategy.

It worked in Wisconsin. Seventeen K-12 schools in rural Wisconsin opened last fall for in-person instruction.3 Reported compliance with masking was high, ranging from 92.1% to 97.4%, and in-school transmission of COVID-19 was low, with seven cases among 4,876 students.

It worked in Salt Lake City.4 In 20 elementary schools open for in-person instruction Dec. 3, 2020, to Jan. 31, 2021, compliance with mask-wearing was high and in-school transmission was very low, despite a high community incidence of COVID-19. Notably, students’ classroom seats were less than 6 feet apart, suggesting that consistent mask-wearing works even when physical distancing is challenging.

One of the best examples of successful school reopening happened in North Carolina, where pediatricians, pediatric infectious disease specialists, and other experts affiliated with Duke University formed the ABC Science Collaborative to support school districts that requested scientific input to help guide return-to-school policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. From Oct. 26, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021, the ABC Science Collaborative worked with 13 school districts that were open for in-person instruction using basic mitigation strategies, including universal masking.5 During this time period, there were 4,969 community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infections in the more than 100,000 students and staff present in schools. Transmission to school contacts was identified in only 209 individuals for a secondary attack rate of less than 1%.

Duke investigator Kanecia Zimmerman, MD, told Duke Today, “We know that, if our goal is to reduce transmission of COVID-19 in schools, there are two effective ways to do that: 1. vaccination, 2. masking. In the setting of schools ... the science suggests masking can be extremely effective, particularly for those who can’t get vaccinated while COVID-19 is still circulating.”

Both the AAP6 and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society7 have emphasized the importance of in-person instruction and endorsed universal masking in school. Mask-optional policies or “mask-if-you-are-unvaccinated” policies don’t work, as we have seen in society at large. They are likely to be especially challenging in school settings. Given an option, many, if not most kids, will take off their masks. Kids who leave them on run the risk of stigmatization or bullying.

On Aug. 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance to recommend universal indoor masking for all students, staff, teachers, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Now we’ll have to wait and see if school districts, elected officials, and parents will get on board with masks. ... and we’ll be left to count the number of rising COVID-19 cases that occur until they do.

Case in point: Kids in Greater Clark County, Ind., headed back to school on July 28. Masks were not required on school property, although unvaccinated students and teachers were “strongly encouraged” to wear them.8

Over the first 8 days of in-person instruction, schools in Greater Clark County identified 70 cases of COVID-19 in students and quarantined more than 1,100 of the district’s 10,300 students. Only the unvaccinated were required to quarantine. The district began requiring masks in all school buildings on Aug. 9.9

The worried mother had one last question for me. “What’s the best mask for a child to wear?” For most kids, a simple, well-fitting cloth mask is fine. The best mask is ultimately the mask a child will wear. A toolkit with practical tips for helping children successfully wear a mask is available on the ABC Science Collaborative website.

Dr. Bryant, president of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, is a pediatrician at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. “Children and COVID-19: State-level data report.”

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. “Children and COVID-19 vaccination trends.”

3. Falk A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:136-40.

4. Hershow RB et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:442-8.

5. Zimmerman KO et al. Pediatrics. 2021 Jul;e2021052686. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052686.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics. “American Academy of Pediatrics updates recommendations for opening schools in fall 2021.”

7. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. “PIDS supports universal masking for students, school staff.”

8. Courtney Hayden. WHAS11. “Greater Clark County Schools return to class July 28.”

9. Dustin Vogt. WAVE3 News. “Greater Clark Country Schools to require masks amid 70 positive cases.”

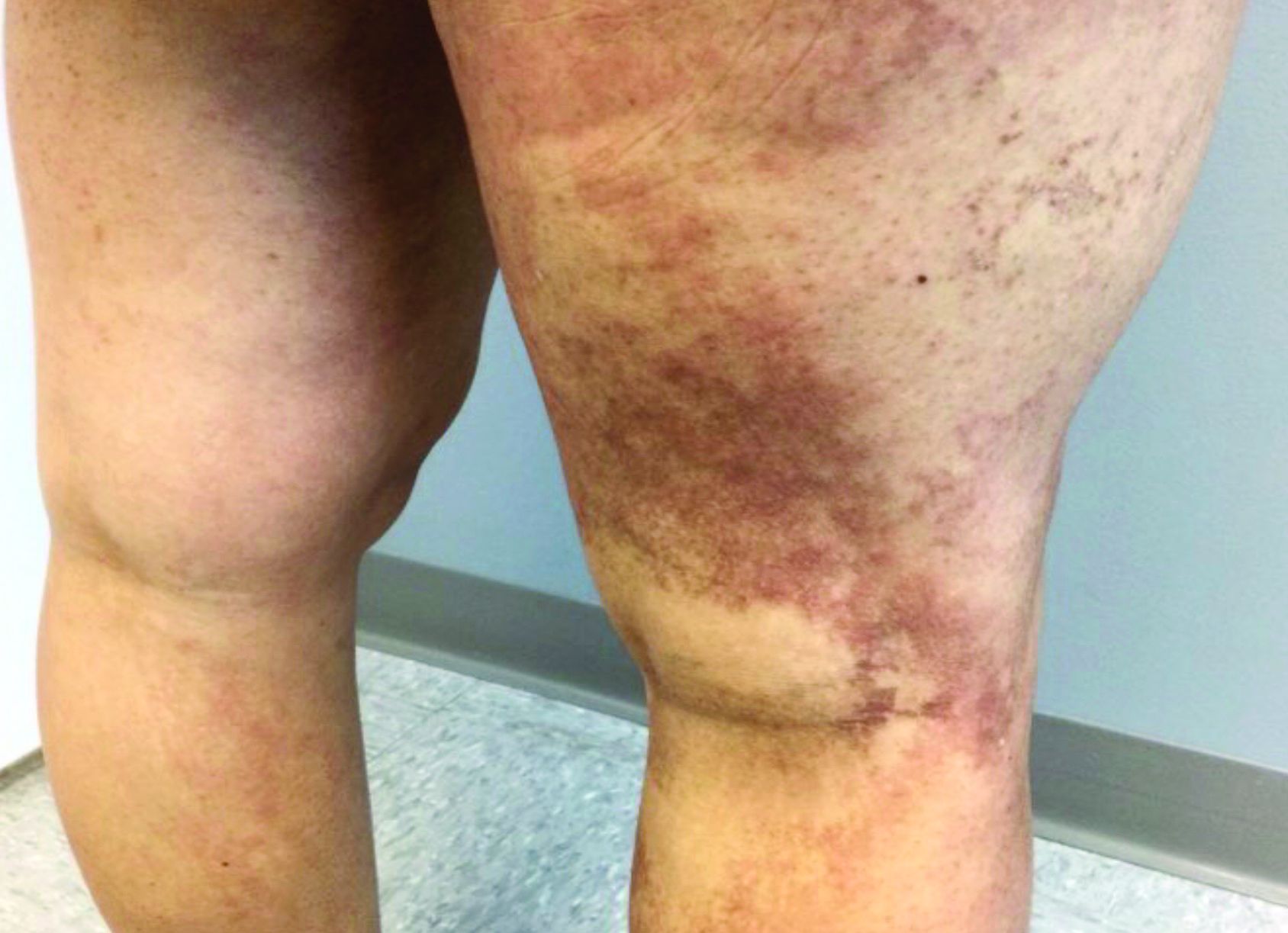

A 35-year-old with erythematous, dusky patches on both lower extremities

Zinc deficiency may be inherited or acquired. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes a zinc transporter. It presents in infancy with the classic triad of diarrhea, dermatitis, and alopecia. Acquired zinc deficiency is due to causes such as alcoholism, malabsorption disorders like cystic fibrosis, inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal surgery, metabolic stress following general surgery, eating disorders, infections, malignancy, or occasionally in pregnancy. Classically, the face, groin, and extremities are affected (often acral), with erythematous, scaly patches. Pustules and bullae may be present. Angular cheilitis is often seen.

Necrolytic migratory erythema, or glucagonoma syndrome, is a very rare syndrome that presents as annular, erythematous patches with blisters that erode on the lower extremities and groin. The condition results from a cancerous tumor in the alpha cells of the pancreas called a glucagonoma, which secretes the hormone glucagon. It is often associated with diabetes and hyperglycemia.

Necrolytic acral erythema resembles acrodermatitis enteropathica and necrolytic migratory erythema clinically, however, it is associated with hepatitis C infection. Lesions are plaques with well defined borders distributed acrally. Treatment of the hepatitis C often improves the dermatitis.

Our patient’s blood work was consistent with nutritional deficiency and revealed low levels of zinc, vitamin A, ceruloplasmin, albumin and prealbumin, total protein, calcium, selenium, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C. Her hemoglobin A1C was under 4. Her hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient received total parenteral nutrition with subsequent complete resolution of her rash. Follow up for gastric bypass patients should be performed long term as they are at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Dr. Bilu Martin, and Andrew Harris, DO, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Aventura, Fla., provided the case and photos.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15; 22(11):13030.

Andrews’ Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Bolognia et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

Zinc deficiency may be inherited or acquired. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes a zinc transporter. It presents in infancy with the classic triad of diarrhea, dermatitis, and alopecia. Acquired zinc deficiency is due to causes such as alcoholism, malabsorption disorders like cystic fibrosis, inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal surgery, metabolic stress following general surgery, eating disorders, infections, malignancy, or occasionally in pregnancy. Classically, the face, groin, and extremities are affected (often acral), with erythematous, scaly patches. Pustules and bullae may be present. Angular cheilitis is often seen.

Necrolytic migratory erythema, or glucagonoma syndrome, is a very rare syndrome that presents as annular, erythematous patches with blisters that erode on the lower extremities and groin. The condition results from a cancerous tumor in the alpha cells of the pancreas called a glucagonoma, which secretes the hormone glucagon. It is often associated with diabetes and hyperglycemia.

Necrolytic acral erythema resembles acrodermatitis enteropathica and necrolytic migratory erythema clinically, however, it is associated with hepatitis C infection. Lesions are plaques with well defined borders distributed acrally. Treatment of the hepatitis C often improves the dermatitis.

Our patient’s blood work was consistent with nutritional deficiency and revealed low levels of zinc, vitamin A, ceruloplasmin, albumin and prealbumin, total protein, calcium, selenium, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C. Her hemoglobin A1C was under 4. Her hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient received total parenteral nutrition with subsequent complete resolution of her rash. Follow up for gastric bypass patients should be performed long term as they are at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Dr. Bilu Martin, and Andrew Harris, DO, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Aventura, Fla., provided the case and photos.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15; 22(11):13030.

Andrews’ Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Bolognia et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

Zinc deficiency may be inherited or acquired. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes a zinc transporter. It presents in infancy with the classic triad of diarrhea, dermatitis, and alopecia. Acquired zinc deficiency is due to causes such as alcoholism, malabsorption disorders like cystic fibrosis, inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal surgery, metabolic stress following general surgery, eating disorders, infections, malignancy, or occasionally in pregnancy. Classically, the face, groin, and extremities are affected (often acral), with erythematous, scaly patches. Pustules and bullae may be present. Angular cheilitis is often seen.

Necrolytic migratory erythema, or glucagonoma syndrome, is a very rare syndrome that presents as annular, erythematous patches with blisters that erode on the lower extremities and groin. The condition results from a cancerous tumor in the alpha cells of the pancreas called a glucagonoma, which secretes the hormone glucagon. It is often associated with diabetes and hyperglycemia.

Necrolytic acral erythema resembles acrodermatitis enteropathica and necrolytic migratory erythema clinically, however, it is associated with hepatitis C infection. Lesions are plaques with well defined borders distributed acrally. Treatment of the hepatitis C often improves the dermatitis.

Our patient’s blood work was consistent with nutritional deficiency and revealed low levels of zinc, vitamin A, ceruloplasmin, albumin and prealbumin, total protein, calcium, selenium, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C. Her hemoglobin A1C was under 4. Her hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient received total parenteral nutrition with subsequent complete resolution of her rash. Follow up for gastric bypass patients should be performed long term as they are at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Dr. Bilu Martin, and Andrew Harris, DO, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Aventura, Fla., provided the case and photos.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15; 22(11):13030.

Andrews’ Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Bolognia et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

Is this a psychiatric emergency? How to screen, assess, and triage safety concerns from the primary care office