User login

COVID-19: Delta variant is raising the stakes

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Needed: More studies of CSF molecular biomarkers in psychiatric disorders

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

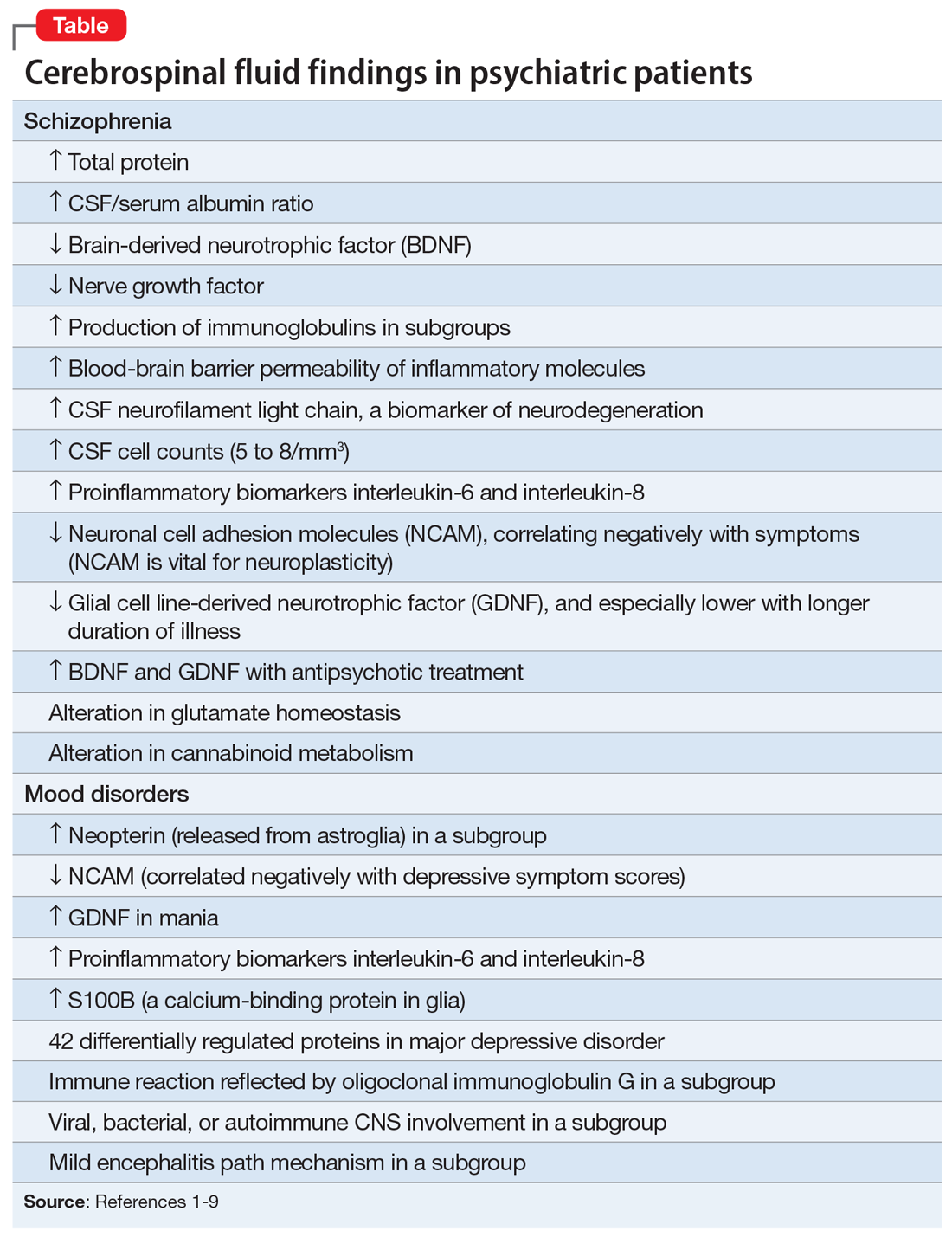

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Medicine’s ‘Big Lie’

While today “The Big Lie” mainly refers to the actions of the prior President, an older and bigger lie that has a real effect on every American is one perpetrated by our very own health care conglomerate. Americans pay the highest rates for health care on the planet; health care consumes about 17% of our gross domestic product.1 If we got higher-quality care, faster services, longer lives, or even greater consumer happiness, paying those rates might be worth it. But we don’t.

Worse yet is the idea that “board certification” assures the public that the doctor from whom they receive/purchase care is of a higher quality than one who is not so credentialed. That is our “Big Lie!” For decades, the public has been told that they should seek out board-certified doctors. Doctors in training have been told they must get board-certified. Hospitals brag about employing only board-certified doctors, insurers sometimes mandate board certification for a doctor to get paid, and employers use board certification as a benchmark for hiring and as a factor in compensation.

The sacred secret is that board certification makes no difference. There is no substantial evidence in any branch of medicine that doctors who are board-certified are better. There is no evidence that board-certified doctors get their patients healthier with more frequency, faster, less expensively, or with fewer medical errors than other doctors. The reality is that board certification is a sham. It’s a certificate granted after taking a very expensive test, and it is now part of an industry that is misleading the public and harming the trust the medical profession had once earned. Board certification is the equivalent of a diploma mill or an online certificate in any other field.

Why has this been kept under wraps for so long? Follow the money. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) oversees 24 specialty boards and reported revenue of $22.2M and expenses of $19.3M on its 2019 IRS Form 990.2 They make profit every year. But, looking further, these “not-for-profit” educational entities are sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars in their “foundations.” Take the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, for instance. They had more than $140M in assets in 2019.3 How is this possible? Easy. They have misled the American public and been remarkably successful convincing other organizations, such as the Joint Commission, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, that board certification is an assurance of quality. They charge high fees to “candidates” for taking the computer-based test and have developed a system called maintenance of certification (MOC) that is onerous, expensive, and serves as an annuity that forces doctors to pay annually to keep their board certification.

Medicine is a science. In the practice of our discipline, we are expected to follow the science and to adhere to scientific principles. Yet there is neither scientific proof nor good evidence that board certification means anything in terms of competence, safety to the public, or quality of care. Doctors favor life-long learning, and continuing education has long been the standard and should remain so, not board certification or MOC. The mandatory continuing education required in every state to maintain a medical license is sufficient to prove doctors are current in their field of practice and to protect the public.

It is time for the medical community to admit that the emperor wears no clothes, and demand that the money grab of the ABMS and its affiliates be halted. This would result in greater access to care for patients and would reduce the cost of medical care, as the hundreds of millions being “stolen” from doctors today—costs that get passed on to patients—could be recouped and used for treating patients who clearly are in need and are being forgotten as the medical-industrial complex continues to flex its muscles and ensnare more of our national budget in its tentacles.

Neil S. Kaye, MD, DLFAPA

Hockessin, Delaware

1. The World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Accessed July 12, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

2. American Board of Medical Specialties. 2019 Form 990. Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.abms.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2019-american-board-of-medical-specialties-form-990.pdf

3. ProPublica. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Accessed July 13, 2021. https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/410654864

While today “The Big Lie” mainly refers to the actions of the prior President, an older and bigger lie that has a real effect on every American is one perpetrated by our very own health care conglomerate. Americans pay the highest rates for health care on the planet; health care consumes about 17% of our gross domestic product.1 If we got higher-quality care, faster services, longer lives, or even greater consumer happiness, paying those rates might be worth it. But we don’t.

Worse yet is the idea that “board certification” assures the public that the doctor from whom they receive/purchase care is of a higher quality than one who is not so credentialed. That is our “Big Lie!” For decades, the public has been told that they should seek out board-certified doctors. Doctors in training have been told they must get board-certified. Hospitals brag about employing only board-certified doctors, insurers sometimes mandate board certification for a doctor to get paid, and employers use board certification as a benchmark for hiring and as a factor in compensation.

The sacred secret is that board certification makes no difference. There is no substantial evidence in any branch of medicine that doctors who are board-certified are better. There is no evidence that board-certified doctors get their patients healthier with more frequency, faster, less expensively, or with fewer medical errors than other doctors. The reality is that board certification is a sham. It’s a certificate granted after taking a very expensive test, and it is now part of an industry that is misleading the public and harming the trust the medical profession had once earned. Board certification is the equivalent of a diploma mill or an online certificate in any other field.

Why has this been kept under wraps for so long? Follow the money. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) oversees 24 specialty boards and reported revenue of $22.2M and expenses of $19.3M on its 2019 IRS Form 990.2 They make profit every year. But, looking further, these “not-for-profit” educational entities are sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars in their “foundations.” Take the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, for instance. They had more than $140M in assets in 2019.3 How is this possible? Easy. They have misled the American public and been remarkably successful convincing other organizations, such as the Joint Commission, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, that board certification is an assurance of quality. They charge high fees to “candidates” for taking the computer-based test and have developed a system called maintenance of certification (MOC) that is onerous, expensive, and serves as an annuity that forces doctors to pay annually to keep their board certification.

Medicine is a science. In the practice of our discipline, we are expected to follow the science and to adhere to scientific principles. Yet there is neither scientific proof nor good evidence that board certification means anything in terms of competence, safety to the public, or quality of care. Doctors favor life-long learning, and continuing education has long been the standard and should remain so, not board certification or MOC. The mandatory continuing education required in every state to maintain a medical license is sufficient to prove doctors are current in their field of practice and to protect the public.

It is time for the medical community to admit that the emperor wears no clothes, and demand that the money grab of the ABMS and its affiliates be halted. This would result in greater access to care for patients and would reduce the cost of medical care, as the hundreds of millions being “stolen” from doctors today—costs that get passed on to patients—could be recouped and used for treating patients who clearly are in need and are being forgotten as the medical-industrial complex continues to flex its muscles and ensnare more of our national budget in its tentacles.

Neil S. Kaye, MD, DLFAPA

Hockessin, Delaware

While today “The Big Lie” mainly refers to the actions of the prior President, an older and bigger lie that has a real effect on every American is one perpetrated by our very own health care conglomerate. Americans pay the highest rates for health care on the planet; health care consumes about 17% of our gross domestic product.1 If we got higher-quality care, faster services, longer lives, or even greater consumer happiness, paying those rates might be worth it. But we don’t.

Worse yet is the idea that “board certification” assures the public that the doctor from whom they receive/purchase care is of a higher quality than one who is not so credentialed. That is our “Big Lie!” For decades, the public has been told that they should seek out board-certified doctors. Doctors in training have been told they must get board-certified. Hospitals brag about employing only board-certified doctors, insurers sometimes mandate board certification for a doctor to get paid, and employers use board certification as a benchmark for hiring and as a factor in compensation.

The sacred secret is that board certification makes no difference. There is no substantial evidence in any branch of medicine that doctors who are board-certified are better. There is no evidence that board-certified doctors get their patients healthier with more frequency, faster, less expensively, or with fewer medical errors than other doctors. The reality is that board certification is a sham. It’s a certificate granted after taking a very expensive test, and it is now part of an industry that is misleading the public and harming the trust the medical profession had once earned. Board certification is the equivalent of a diploma mill or an online certificate in any other field.

Why has this been kept under wraps for so long? Follow the money. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) oversees 24 specialty boards and reported revenue of $22.2M and expenses of $19.3M on its 2019 IRS Form 990.2 They make profit every year. But, looking further, these “not-for-profit” educational entities are sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars in their “foundations.” Take the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, for instance. They had more than $140M in assets in 2019.3 How is this possible? Easy. They have misled the American public and been remarkably successful convincing other organizations, such as the Joint Commission, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, that board certification is an assurance of quality. They charge high fees to “candidates” for taking the computer-based test and have developed a system called maintenance of certification (MOC) that is onerous, expensive, and serves as an annuity that forces doctors to pay annually to keep their board certification.

Medicine is a science. In the practice of our discipline, we are expected to follow the science and to adhere to scientific principles. Yet there is neither scientific proof nor good evidence that board certification means anything in terms of competence, safety to the public, or quality of care. Doctors favor life-long learning, and continuing education has long been the standard and should remain so, not board certification or MOC. The mandatory continuing education required in every state to maintain a medical license is sufficient to prove doctors are current in their field of practice and to protect the public.

It is time for the medical community to admit that the emperor wears no clothes, and demand that the money grab of the ABMS and its affiliates be halted. This would result in greater access to care for patients and would reduce the cost of medical care, as the hundreds of millions being “stolen” from doctors today—costs that get passed on to patients—could be recouped and used for treating patients who clearly are in need and are being forgotten as the medical-industrial complex continues to flex its muscles and ensnare more of our national budget in its tentacles.

Neil S. Kaye, MD, DLFAPA

Hockessin, Delaware

1. The World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Accessed July 12, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

2. American Board of Medical Specialties. 2019 Form 990. Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.abms.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2019-american-board-of-medical-specialties-form-990.pdf

3. ProPublica. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Accessed July 13, 2021. https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/410654864

1. The World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Accessed July 12, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

2. American Board of Medical Specialties. 2019 Form 990. Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.abms.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2019-american-board-of-medical-specialties-form-990.pdf

3. ProPublica. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Accessed July 13, 2021. https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/410654864

My palliative care rotation: Lessons of gratitude, mindfulness, and kindness

As a psychiatry resident and as a part of consultation-liaison service, I have visited many palliative care patients to assist other physicians in managing psychiatric issues such as depression, anxiety, or delirium. But recently, as the first resident from our Department of Psychiatry who was sent to a palliative care rotation, I followed these patients as a part of a primary palliative care team. Doing so allowed me to see patients from the other side of the bridge.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the suffering and stress of a patient’s illness, with the primary goal of improving the quality of life of the patient and their families. The palliative care team works in collaboration with the patient’s other clinicians to provide an extra layer of support. They provide biopsychosociocultural interventions that are in harmony with the needs of the patient rather than the prognosis of the illness. To do so, they first must evaluate the needs of the patient and their family. This is a time-consuming, energy-consuming, emotionally draining job.

During my palliative care rotation, I attended table rounds, bedside rounds, family meetings, long counseling sessions, and disposition planning meetings. This rotation also gave me the opportunity to place my feet in the shoes of a palliative care team and to reflect on how it feels to be the physician of a patient who is dying, which as a psychiatric resident I had seldom experienced. I learned that although working with patients who are dying can cause stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue, it also helps physicians appreciate the little things in life. To appreciate all the blessings we have that we usually take for granted. To practice gratitude. To be kind.

Upon reflection, I learned that the rounds of palliative care are actually mindfulness-based discussions that provide cushions of supportive work, facilitate feelings of being in control, tend to alleviate physical as well as mental suffering, foster clear-sighted hope, and assist in establishing small, subjectively significant, realistic goals for the patient’s immediate future, and to help the patient achieve these goals.

A valuable lesson from a patient

I want to highlight a case of a 65-year-old woman I first visited while I was shadowing my attending, who had been providing palliative care to the patient and her family for several months. The patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital because cancer had invaded her small bowel and caused mechanical obstruction, resulting in intractable vomiting, abdominal distension, and anorexia. She underwent open laparotomy and ileostomy for symptomatic relief. A nasogastric tube was placed, and she was put on total parenteral nutrition. The day I met her was her third postoperative day. She had been improving significantly, and she wanted to eat. She was missing food. Most of the discussion in the round among my attending, the patient, and her family was centered around how to get to the point where she would be able to eat again and appreciate the taste of biryani.

What my attending did was incredible. After assessing the patient’s needs, he instilled a realistic hope: the hope of tasting food again. The attending, while acknowledging the patient’s apprehensions, respectfully and supportively kept her from wandering into the future, made every possible attempt to bring her attention back to the present moment, and helped her establish goals for the present and her immediate future. My attending was not toxic-positive, forcing his patient to uselessly revisit her current trauma. Instead, he was kind, empathic, and considerate. His primary focus was to understand rather than to be understood, to help her find meaning, and to improve her quality of life—a quality she defined for herself, which was to taste the food of her choice.

That day, when I returned to my working station in the psychiatry ward and had lunch in the break room, I thought, “When I eat, how often do I think about eating?” Mostly I either think about work, tasks, and presentations, or I scroll on social media.

Our taste buds indeed get adapted to repetitive stimulation, but the experience of eating our favorite dish is the naked truth of being alive, and is something that I have been taking for granted for a long time. These are little things in life that I need to appreciate, and learn to cultivate their power.

As a psychiatry resident and as a part of consultation-liaison service, I have visited many palliative care patients to assist other physicians in managing psychiatric issues such as depression, anxiety, or delirium. But recently, as the first resident from our Department of Psychiatry who was sent to a palliative care rotation, I followed these patients as a part of a primary palliative care team. Doing so allowed me to see patients from the other side of the bridge.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the suffering and stress of a patient’s illness, with the primary goal of improving the quality of life of the patient and their families. The palliative care team works in collaboration with the patient’s other clinicians to provide an extra layer of support. They provide biopsychosociocultural interventions that are in harmony with the needs of the patient rather than the prognosis of the illness. To do so, they first must evaluate the needs of the patient and their family. This is a time-consuming, energy-consuming, emotionally draining job.

During my palliative care rotation, I attended table rounds, bedside rounds, family meetings, long counseling sessions, and disposition planning meetings. This rotation also gave me the opportunity to place my feet in the shoes of a palliative care team and to reflect on how it feels to be the physician of a patient who is dying, which as a psychiatric resident I had seldom experienced. I learned that although working with patients who are dying can cause stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue, it also helps physicians appreciate the little things in life. To appreciate all the blessings we have that we usually take for granted. To practice gratitude. To be kind.

Upon reflection, I learned that the rounds of palliative care are actually mindfulness-based discussions that provide cushions of supportive work, facilitate feelings of being in control, tend to alleviate physical as well as mental suffering, foster clear-sighted hope, and assist in establishing small, subjectively significant, realistic goals for the patient’s immediate future, and to help the patient achieve these goals.

A valuable lesson from a patient

I want to highlight a case of a 65-year-old woman I first visited while I was shadowing my attending, who had been providing palliative care to the patient and her family for several months. The patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital because cancer had invaded her small bowel and caused mechanical obstruction, resulting in intractable vomiting, abdominal distension, and anorexia. She underwent open laparotomy and ileostomy for symptomatic relief. A nasogastric tube was placed, and she was put on total parenteral nutrition. The day I met her was her third postoperative day. She had been improving significantly, and she wanted to eat. She was missing food. Most of the discussion in the round among my attending, the patient, and her family was centered around how to get to the point where she would be able to eat again and appreciate the taste of biryani.

What my attending did was incredible. After assessing the patient’s needs, he instilled a realistic hope: the hope of tasting food again. The attending, while acknowledging the patient’s apprehensions, respectfully and supportively kept her from wandering into the future, made every possible attempt to bring her attention back to the present moment, and helped her establish goals for the present and her immediate future. My attending was not toxic-positive, forcing his patient to uselessly revisit her current trauma. Instead, he was kind, empathic, and considerate. His primary focus was to understand rather than to be understood, to help her find meaning, and to improve her quality of life—a quality she defined for herself, which was to taste the food of her choice.

That day, when I returned to my working station in the psychiatry ward and had lunch in the break room, I thought, “When I eat, how often do I think about eating?” Mostly I either think about work, tasks, and presentations, or I scroll on social media.

Our taste buds indeed get adapted to repetitive stimulation, but the experience of eating our favorite dish is the naked truth of being alive, and is something that I have been taking for granted for a long time. These are little things in life that I need to appreciate, and learn to cultivate their power.

As a psychiatry resident and as a part of consultation-liaison service, I have visited many palliative care patients to assist other physicians in managing psychiatric issues such as depression, anxiety, or delirium. But recently, as the first resident from our Department of Psychiatry who was sent to a palliative care rotation, I followed these patients as a part of a primary palliative care team. Doing so allowed me to see patients from the other side of the bridge.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the suffering and stress of a patient’s illness, with the primary goal of improving the quality of life of the patient and their families. The palliative care team works in collaboration with the patient’s other clinicians to provide an extra layer of support. They provide biopsychosociocultural interventions that are in harmony with the needs of the patient rather than the prognosis of the illness. To do so, they first must evaluate the needs of the patient and their family. This is a time-consuming, energy-consuming, emotionally draining job.

During my palliative care rotation, I attended table rounds, bedside rounds, family meetings, long counseling sessions, and disposition planning meetings. This rotation also gave me the opportunity to place my feet in the shoes of a palliative care team and to reflect on how it feels to be the physician of a patient who is dying, which as a psychiatric resident I had seldom experienced. I learned that although working with patients who are dying can cause stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue, it also helps physicians appreciate the little things in life. To appreciate all the blessings we have that we usually take for granted. To practice gratitude. To be kind.

Upon reflection, I learned that the rounds of palliative care are actually mindfulness-based discussions that provide cushions of supportive work, facilitate feelings of being in control, tend to alleviate physical as well as mental suffering, foster clear-sighted hope, and assist in establishing small, subjectively significant, realistic goals for the patient’s immediate future, and to help the patient achieve these goals.

A valuable lesson from a patient

I want to highlight a case of a 65-year-old woman I first visited while I was shadowing my attending, who had been providing palliative care to the patient and her family for several months. The patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital because cancer had invaded her small bowel and caused mechanical obstruction, resulting in intractable vomiting, abdominal distension, and anorexia. She underwent open laparotomy and ileostomy for symptomatic relief. A nasogastric tube was placed, and she was put on total parenteral nutrition. The day I met her was her third postoperative day. She had been improving significantly, and she wanted to eat. She was missing food. Most of the discussion in the round among my attending, the patient, and her family was centered around how to get to the point where she would be able to eat again and appreciate the taste of biryani.

What my attending did was incredible. After assessing the patient’s needs, he instilled a realistic hope: the hope of tasting food again. The attending, while acknowledging the patient’s apprehensions, respectfully and supportively kept her from wandering into the future, made every possible attempt to bring her attention back to the present moment, and helped her establish goals for the present and her immediate future. My attending was not toxic-positive, forcing his patient to uselessly revisit her current trauma. Instead, he was kind, empathic, and considerate. His primary focus was to understand rather than to be understood, to help her find meaning, and to improve her quality of life—a quality she defined for herself, which was to taste the food of her choice.

That day, when I returned to my working station in the psychiatry ward and had lunch in the break room, I thought, “When I eat, how often do I think about eating?” Mostly I either think about work, tasks, and presentations, or I scroll on social media.

Our taste buds indeed get adapted to repetitive stimulation, but the experience of eating our favorite dish is the naked truth of being alive, and is something that I have been taking for granted for a long time. These are little things in life that I need to appreciate, and learn to cultivate their power.

Introduction: Precision Oncology Changes the Game for VA Health Care (FULL)

For US Army veteran Tam Huynh, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) precision oncology program has been the proverbial game changer. Diagnosed in 2016 with stage IV lung cancer and physically depleted by chemotherapy, Huynh learned that treatment based on the precise molecular makeup of his tumors held the potential for improving quality of life. Through the VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), Huynh was matched to a medication shown to help patients whose tumors had the same genetic mutation as Huynh’s tumors. Today, Huynh is not only free of chemotherapy’s debilitating adverse effects, but able to enjoy time with his family and return to work.

Huynh is one of 400,000 veterans treated for cancer annually at the VA. The life-changing treatment he received is due to the legacy of research, integrated care, and collaboration that is the hallmark of the VA health care system. The NPOP is a natural outgrowth of this legacy, and, as Executive-in-Charge Richard Stone, MD, notes in his Foreword, part of the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) evolution as a learning health care system. The articles in this special issue represent a snapshot of the work underway under VHA NPOP as well as the dedication of VHA staff nationwide to provide patient-centric care to every veteran.

Leading off this special issue, NPOP director Michael J. Kelley, MD, provides context for understanding the paradigm shift represented by precision oncology.2 He also discusses how, within 5 years, the program came together from its start as a regional effort to its use today by almost every VA oncology practice. Kelley also explains the complexity behind interpreting next-generation sequencing (NGS) gene panel test results and how VA medical centers can call upon NPOP for assistance with this interpretation. Further, he states the “obligation” for new medical technology to be accessible and notes how NPOP was “intentional” during implementation to ensure rural veterans would be offered testing.2

Following Kelley’s discussion is a series of articles focused on precision oncology for prostate cancer, which affects 15,000 veterans yearly. The first, an overview of the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), provides a short history of the organization and how it came to partner with the VA.3 Written by several PCF staff, including President and CEO Jonathan Simons, MD, the paper notes how the commitment of early leaders like S. Ward Casscells, MD, and Larry Stupski led to PCF’s “no veteran left behind” philosophy; ie, ensuring veteran access to clinical trials and world class care regardless of location. As the first disease-specific national network for oncology trials serving veterans, PCF aims to provide a model for all of US health care in the delivery of precision oncology care.

A critical part of PCF is the Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP), which focuses on genetics and genomic testing. Bruce Montgomery, MD, and Matthew Retting, MD—VHA’s leading experts in prostate cancer—shine the spotlight on VA’s research track record, specifically the genomics of metastatic prostate cancer.4 They also note the program’s focus on African American veteran patients who are disproportionately affected by the disease but well represented in the VA. In discussing future directions, the authors explain the importance of expanding genetic testing for those diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice (PATCH) is a clinical trials network that works hand-in-hand with POPCaP to use genetic data collected by POPCaP sites to find patients for trials. In their discussion, authors Julie N. Graff, MD, and Grant D. Huang, MD, who leads VA Research’s Cooperative Studies Program, focus on 3 key areas: (1) the challenges of precision oncology when working with relatively rare mutations; (2) 2 new drug trials at VA that will help clinicians know whether certain targeted therapies work for prostate cancer; and (3) how VA is emerging as a national partner in drug discovery and the approval of precision drugs.5

Turning to lung cancer–the second leading cause of cancer death among veterans–Drew Moghanaki, MD, MPH, and Michael Hagan, MD, discuss 3 multisite initiatives launched in 2016 and 2017.6 The first trial, VA Partnership to Increase Access to Lung Cancer Screening (VA-PALS), is a multisite project sponsored by the VA’s Office of Rural Health and Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. The trial’s goal is to reduce lung cancer mortality through a robust early detection program. The second trial, VA Lung Cancer Surgery OR Radiation therapy (VALOR) compares whether radiation or surgery is the best for early-stage lung cancer. Notably, VALOR may be one of the most difficult randomized trial ever attempted in lung cancer research (4 previous phase 3 trials outside the VA closed prematurely). By addressing the previous challenges associated with running such a trial, the VALOR study team already has enrolled more than all of the previous phase 3 efforts combined. The third trial is VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program (VA-ROQS), which was created in 2016 to benchmark the treatment of veterans with lung cancer. VA-ROQS aims to create a national network of Lung Cancer Centers of Excellence that work with VISNs to ensure that treatment decisions for veterans with lung cancer are based on all available molecular information.

The final group of authors, led by Maren T. Scheuner, MD, discuss how the advent of germline testing as a standard-of-care practice for certain tumor types presents opportunities and challenges for precision oncology.7 One of the primary challenges they note is the shortage of genetics professionals, both within the VA system and health care generally. To help address this issue, they recommend leveraging VA’s longstanding partnership with its academic affiliates.

Precision oncology clearly demonstrates how applying knowledge regarding one of the smallest of living matter can make a tremendous difference in the matter of living. Tam Huynh’s story is proof positive. Speaking at last year’s AMSUS (Society for Federal Health Professionals) annual meeting about his experience, Huynh said that all veterans should have access to the same life-changing treatment he received. This is exactly where the VA NPOP is heading.

1. How the VA is using AI to target cancer, https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/ibm-2018/watson-va-cancer/1925. Accessed August 6, 2020.

2. Kelley MJ. VA National Precision Oncology Program. Fed Pract. 2020;37 (suppl 4):S22-S27. doi:10.12788/fp.0037

3. Levine RD, Ekanayake RN, Martin AC, et al. Prostate Cancer Foundation-Department of Veterans Affairs partnership: a model of public-private collaboration to advance treatment and care of invasive cancers. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 4):S32-S37. doi: 10.12788/fp.0035

4. Montgomery B, Rettig M, Kasten J, Muralidhar S, Myrie K, Ramoni R. The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) network: a Veterans Affairs/Prostate Cancer Foundation collaboration. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 4):S48-S53. doi:10.12788/fp.0021

5. Graff JN, Huang GD. Leveraging Veterans Health Administration clinical and research resources to accelerate discovery and testing in precision oncology. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 4):S62-S67. doi:10.12788/fp.0028

6. Moghanaki D, Hagan M. Strategic initiatives for veterans with lung cancer. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 4):S76-S80. doi:10.12788/fp.0019

7. Scheuner MT, Myrie K, Peredo J, et al. Integrating germline genetics into precision oncology practice in the Veterans Health Administration: challenges and opportunities. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 4):S82-S88. doi:10.12788/fp.0033

For US Army veteran Tam Huynh, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) precision oncology program has been the proverbial game changer. Diagnosed in 2016 with stage IV lung cancer and physically depleted by chemotherapy, Huynh learned that treatment based on the precise molecular makeup of his tumors held the potential for improving quality of life. Through the VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), Huynh was matched to a medication shown to help patients whose tumors had the same genetic mutation as Huynh’s tumors. Today, Huynh is not only free of chemotherapy’s debilitating adverse effects, but able to enjoy time with his family and return to work.

Huynh is one of 400,000 veterans treated for cancer annually at the VA. The life-changing treatment he received is due to the legacy of research, integrated care, and collaboration that is the hallmark of the VA health care system. The NPOP is a natural outgrowth of this legacy, and, as Executive-in-Charge Richard Stone, MD, notes in his Foreword, part of the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) evolution as a learning health care system. The articles in this special issue represent a snapshot of the work underway under VHA NPOP as well as the dedication of VHA staff nationwide to provide patient-centric care to every veteran.

Leading off this special issue, NPOP director Michael J. Kelley, MD, provides context for understanding the paradigm shift represented by precision oncology.2 He also discusses how, within 5 years, the program came together from its start as a regional effort to its use today by almost every VA oncology practice. Kelley also explains the complexity behind interpreting next-generation sequencing (NGS) gene panel test results and how VA medical centers can call upon NPOP for assistance with this interpretation. Further, he states the “obligation” for new medical technology to be accessible and notes how NPOP was “intentional” during implementation to ensure rural veterans would be offered testing.2

Following Kelley’s discussion is a series of articles focused on precision oncology for prostate cancer, which affects 15,000 veterans yearly. The first, an overview of the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), provides a short history of the organization and how it came to partner with the VA.3 Written by several PCF staff, including President and CEO Jonathan Simons, MD, the paper notes how the commitment of early leaders like S. Ward Casscells, MD, and Larry Stupski led to PCF’s “no veteran left behind” philosophy; ie, ensuring veteran access to clinical trials and world class care regardless of location. As the first disease-specific national network for oncology trials serving veterans, PCF aims to provide a model for all of US health care in the delivery of precision oncology care.

A critical part of PCF is the Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP), which focuses on genetics and genomic testing. Bruce Montgomery, MD, and Matthew Retting, MD—VHA’s leading experts in prostate cancer—shine the spotlight on VA’s research track record, specifically the genomics of metastatic prostate cancer.4 They also note the program’s focus on African American veteran patients who are disproportionately affected by the disease but well represented in the VA. In discussing future directions, the authors explain the importance of expanding genetic testing for those diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice (PATCH) is a clinical trials network that works hand-in-hand with POPCaP to use genetic data collected by POPCaP sites to find patients for trials. In their discussion, authors Julie N. Graff, MD, and Grant D. Huang, MD, who leads VA Research’s Cooperative Studies Program, focus on 3 key areas: (1) the challenges of precision oncology when working with relatively rare mutations; (2) 2 new drug trials at VA that will help clinicians know whether certain targeted therapies work for prostate cancer; and (3) how VA is emerging as a national partner in drug discovery and the approval of precision drugs.5