User login

MDedge latest news is breaking news from medical conferences, journals, guidelines, the FDA and CDC.

Vasculitis Patients Need Multiple COVID Vaccine Boosters

People with vasculitis may need at least three or four vaccinations for COVID-19 before they start to show an immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection, new research has suggested.

In a longitudinal retrospective study, serum antibody neutralization against the Omicron variant of the virus and its descendants was found to be “largely absent” after the first two doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been given to patients. But increasing neutralizing antibody titers were seen after both the third and fourth vaccine boosters had been administered.

Results also showed that the more recently people had been treated with the B cell–depleting therapy rituximab, the lower the levels of immunogenicity that were achieved, and thus protection against SARS-CoV-2.

“Our results have significant implications for individuals treated with rituximab in the post-Omicron era, highlighting the value of additive boosters in affirming increasing protection in clinically vulnerable populations,” the team behind the work at the University of Cambridge in England, has reported in Science Advances.

Moreover, because the use of rituximab reduced the neutralization of not just wild-type (WT) Omicron but also the Omicron-descendant variants BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB, this highlights “the urgent need for additional adjunctive strategies to enhance vaccine-induced immunity as well as preferential access for such patients to updated vaccines using spike from now circulating Omicron lineages,” the team added.

Studying Humoral Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

Corresponding author Ravindra K. Gupta, BMBCh, MA, MPH, PhD, told this news organization that studying humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunocompromised individuals such as those with vasculitis was important for two main reasons.

“It is really important at individual level for their own health, of course, but also because we know that variants of concern have often evolved and developed within patients and can then spread in wider populations,” he said.

Gupta, who is professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute for Therapeutic Immunology & Infectious Disease added: “We believe that the variants of concern that we’re having to deal with right now, including Omicron, have come from such [immunocompromised] individuals.”

Omicron “was a big shift,” Gupta noted. “It had a lot of new mutations on it, so it was almost like a new strain of the virus.” Few studies have looked at the longitudinal immunogenicity proffered by COVID vaccines in the post-Omicron era, particularly in those with vasculitis who are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including rituximab.

Two-Pronged Study Approach

For the study, a population of immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with vasculitis who had been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years was identified. Just over half (58%) had received adenovirus-based AZD1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca-Oxford; AZN) and 37% BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech; mRNA) as their primary vaccines. Patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis comprised the majority of those who received rituximab (83%), compared with less than half of those who did not take rituximab (48%).

A two-pronged approach was taken with the researchers first measuring neutralizing antibody titers before and 30 days after four successive COVID vaccinations in a group of 32 individuals with available samples. They then performed a cross-sectional, case-control study in 95 individuals to look at neutralizing antibody titers and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) in individuals who had (n = 64) and had not (n = 31) been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years and had samples available after their third and fourth COVID vaccinations.

The first analysis was done to see how people were responding to vaccination over time. “That told us that there was a problem with the first two doses and that we got some response after doses three and four, but the response was uniformly quite poor against the new variants of concern,” Gupta said.

A human embryonic kidney cell model had been used to determine individuals’ neutralizing antibody titers in response to WT, BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB pseudotyped viruses. After the first and second COVID vaccinations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) against each variant barely increased from a baseline of 40.0. The greatest increases in GMT was seen with the WT virus, at 43.7, 90.7, 256.3, and 394.2, after the first, second, third and fourth doses, respectively. The lowest increases in GMT were seen with the XBB variant, with respective values of 40.0, 40.8, 45.7, and 53.9.

Incremental Benefit Offers Some ‘Reassurance’

Vasculitis specialist Rona Smith, MA, MB BChir, MD, who was one of the authors of the paper, told this news organization separately that the results showed there was “an incremental benefit of having COVID vaccinations,” which “offers a little bit of reassurance” that there can be an immune response in people with vasculitis.

Although results of the cross-sectional study showed that there was a significant dampening effect of rituximab treatment on the immune response, “I don’t think it’s an isolated effect in our [vasculitis] patients,” Smith suggested, adding the results were “probably still relevant to patients who receive routine dosing of rituximab for other conditions.”

Neutralizing antibody titers were consistently lower among individuals who had been treated with rituximab vs those who had not, with treatment in the past 18 months found to significantly impair immunogenicity.

The ADCC response was better preserved than the neutralizing antibody response, Gupta said, although it was still significantly lower in the rituximab-treated than in the non–rituximab-treated patients.

When to Vaccinate in Vasculitis?

Regarding when to give vaccines to people with vasculitis, Smith said: “Current recommendations are that patients should receive any vaccines that they’re offered routinely, whether that be COVID vaccines, flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccines.”

As for the timing of those vaccinations, she observed that the current thinking was that vaccinations should “ideally be at least 1 month before a rituximab treatment, and ideally 3-4 [months] after their last dose. However, as many patients are on a 6-month dosing cycle, it can be difficult for some of them to find a suitable time window to have the COVID vaccine when it is offered.”

Additional precautions, such as wearing masks in crowded places and avoiding visits to acutely unwell friends or relatives, may still be prudent, Smith acknowledged, but he was clear that people should not be locking themselves away as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When advising patients, “our general recommendation is that it is better to have a vaccine than not, but we can’t guarantee how well you will respond to it, but some response is better than none,” Smith said.

The study was independently supported. Gupta had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Smith was a coauthor of the paper and has received research grant funding from Union Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline/Vir Biotechnology, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, and Vasculitis UK. Another coauthor reported receiving research grants from CSL Vifor, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board, consultancy, and lecture fees from Roche and CSL Vifor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with vasculitis may need at least three or four vaccinations for COVID-19 before they start to show an immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection, new research has suggested.

In a longitudinal retrospective study, serum antibody neutralization against the Omicron variant of the virus and its descendants was found to be “largely absent” after the first two doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been given to patients. But increasing neutralizing antibody titers were seen after both the third and fourth vaccine boosters had been administered.

Results also showed that the more recently people had been treated with the B cell–depleting therapy rituximab, the lower the levels of immunogenicity that were achieved, and thus protection against SARS-CoV-2.

“Our results have significant implications for individuals treated with rituximab in the post-Omicron era, highlighting the value of additive boosters in affirming increasing protection in clinically vulnerable populations,” the team behind the work at the University of Cambridge in England, has reported in Science Advances.

Moreover, because the use of rituximab reduced the neutralization of not just wild-type (WT) Omicron but also the Omicron-descendant variants BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB, this highlights “the urgent need for additional adjunctive strategies to enhance vaccine-induced immunity as well as preferential access for such patients to updated vaccines using spike from now circulating Omicron lineages,” the team added.

Studying Humoral Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

Corresponding author Ravindra K. Gupta, BMBCh, MA, MPH, PhD, told this news organization that studying humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunocompromised individuals such as those with vasculitis was important for two main reasons.

“It is really important at individual level for their own health, of course, but also because we know that variants of concern have often evolved and developed within patients and can then spread in wider populations,” he said.

Gupta, who is professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute for Therapeutic Immunology & Infectious Disease added: “We believe that the variants of concern that we’re having to deal with right now, including Omicron, have come from such [immunocompromised] individuals.”

Omicron “was a big shift,” Gupta noted. “It had a lot of new mutations on it, so it was almost like a new strain of the virus.” Few studies have looked at the longitudinal immunogenicity proffered by COVID vaccines in the post-Omicron era, particularly in those with vasculitis who are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including rituximab.

Two-Pronged Study Approach

For the study, a population of immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with vasculitis who had been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years was identified. Just over half (58%) had received adenovirus-based AZD1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca-Oxford; AZN) and 37% BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech; mRNA) as their primary vaccines. Patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis comprised the majority of those who received rituximab (83%), compared with less than half of those who did not take rituximab (48%).

A two-pronged approach was taken with the researchers first measuring neutralizing antibody titers before and 30 days after four successive COVID vaccinations in a group of 32 individuals with available samples. They then performed a cross-sectional, case-control study in 95 individuals to look at neutralizing antibody titers and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) in individuals who had (n = 64) and had not (n = 31) been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years and had samples available after their third and fourth COVID vaccinations.

The first analysis was done to see how people were responding to vaccination over time. “That told us that there was a problem with the first two doses and that we got some response after doses three and four, but the response was uniformly quite poor against the new variants of concern,” Gupta said.

A human embryonic kidney cell model had been used to determine individuals’ neutralizing antibody titers in response to WT, BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB pseudotyped viruses. After the first and second COVID vaccinations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) against each variant barely increased from a baseline of 40.0. The greatest increases in GMT was seen with the WT virus, at 43.7, 90.7, 256.3, and 394.2, after the first, second, third and fourth doses, respectively. The lowest increases in GMT were seen with the XBB variant, with respective values of 40.0, 40.8, 45.7, and 53.9.

Incremental Benefit Offers Some ‘Reassurance’

Vasculitis specialist Rona Smith, MA, MB BChir, MD, who was one of the authors of the paper, told this news organization separately that the results showed there was “an incremental benefit of having COVID vaccinations,” which “offers a little bit of reassurance” that there can be an immune response in people with vasculitis.

Although results of the cross-sectional study showed that there was a significant dampening effect of rituximab treatment on the immune response, “I don’t think it’s an isolated effect in our [vasculitis] patients,” Smith suggested, adding the results were “probably still relevant to patients who receive routine dosing of rituximab for other conditions.”

Neutralizing antibody titers were consistently lower among individuals who had been treated with rituximab vs those who had not, with treatment in the past 18 months found to significantly impair immunogenicity.

The ADCC response was better preserved than the neutralizing antibody response, Gupta said, although it was still significantly lower in the rituximab-treated than in the non–rituximab-treated patients.

When to Vaccinate in Vasculitis?

Regarding when to give vaccines to people with vasculitis, Smith said: “Current recommendations are that patients should receive any vaccines that they’re offered routinely, whether that be COVID vaccines, flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccines.”

As for the timing of those vaccinations, she observed that the current thinking was that vaccinations should “ideally be at least 1 month before a rituximab treatment, and ideally 3-4 [months] after their last dose. However, as many patients are on a 6-month dosing cycle, it can be difficult for some of them to find a suitable time window to have the COVID vaccine when it is offered.”

Additional precautions, such as wearing masks in crowded places and avoiding visits to acutely unwell friends or relatives, may still be prudent, Smith acknowledged, but he was clear that people should not be locking themselves away as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When advising patients, “our general recommendation is that it is better to have a vaccine than not, but we can’t guarantee how well you will respond to it, but some response is better than none,” Smith said.

The study was independently supported. Gupta had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Smith was a coauthor of the paper and has received research grant funding from Union Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline/Vir Biotechnology, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, and Vasculitis UK. Another coauthor reported receiving research grants from CSL Vifor, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board, consultancy, and lecture fees from Roche and CSL Vifor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with vasculitis may need at least three or four vaccinations for COVID-19 before they start to show an immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection, new research has suggested.

In a longitudinal retrospective study, serum antibody neutralization against the Omicron variant of the virus and its descendants was found to be “largely absent” after the first two doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been given to patients. But increasing neutralizing antibody titers were seen after both the third and fourth vaccine boosters had been administered.

Results also showed that the more recently people had been treated with the B cell–depleting therapy rituximab, the lower the levels of immunogenicity that were achieved, and thus protection against SARS-CoV-2.

“Our results have significant implications for individuals treated with rituximab in the post-Omicron era, highlighting the value of additive boosters in affirming increasing protection in clinically vulnerable populations,” the team behind the work at the University of Cambridge in England, has reported in Science Advances.

Moreover, because the use of rituximab reduced the neutralization of not just wild-type (WT) Omicron but also the Omicron-descendant variants BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB, this highlights “the urgent need for additional adjunctive strategies to enhance vaccine-induced immunity as well as preferential access for such patients to updated vaccines using spike from now circulating Omicron lineages,” the team added.

Studying Humoral Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

Corresponding author Ravindra K. Gupta, BMBCh, MA, MPH, PhD, told this news organization that studying humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunocompromised individuals such as those with vasculitis was important for two main reasons.

“It is really important at individual level for their own health, of course, but also because we know that variants of concern have often evolved and developed within patients and can then spread in wider populations,” he said.

Gupta, who is professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute for Therapeutic Immunology & Infectious Disease added: “We believe that the variants of concern that we’re having to deal with right now, including Omicron, have come from such [immunocompromised] individuals.”

Omicron “was a big shift,” Gupta noted. “It had a lot of new mutations on it, so it was almost like a new strain of the virus.” Few studies have looked at the longitudinal immunogenicity proffered by COVID vaccines in the post-Omicron era, particularly in those with vasculitis who are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including rituximab.

Two-Pronged Study Approach

For the study, a population of immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with vasculitis who had been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years was identified. Just over half (58%) had received adenovirus-based AZD1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca-Oxford; AZN) and 37% BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech; mRNA) as their primary vaccines. Patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis comprised the majority of those who received rituximab (83%), compared with less than half of those who did not take rituximab (48%).

A two-pronged approach was taken with the researchers first measuring neutralizing antibody titers before and 30 days after four successive COVID vaccinations in a group of 32 individuals with available samples. They then performed a cross-sectional, case-control study in 95 individuals to look at neutralizing antibody titers and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) in individuals who had (n = 64) and had not (n = 31) been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years and had samples available after their third and fourth COVID vaccinations.

The first analysis was done to see how people were responding to vaccination over time. “That told us that there was a problem with the first two doses and that we got some response after doses three and four, but the response was uniformly quite poor against the new variants of concern,” Gupta said.

A human embryonic kidney cell model had been used to determine individuals’ neutralizing antibody titers in response to WT, BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB pseudotyped viruses. After the first and second COVID vaccinations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) against each variant barely increased from a baseline of 40.0. The greatest increases in GMT was seen with the WT virus, at 43.7, 90.7, 256.3, and 394.2, after the first, second, third and fourth doses, respectively. The lowest increases in GMT were seen with the XBB variant, with respective values of 40.0, 40.8, 45.7, and 53.9.

Incremental Benefit Offers Some ‘Reassurance’

Vasculitis specialist Rona Smith, MA, MB BChir, MD, who was one of the authors of the paper, told this news organization separately that the results showed there was “an incremental benefit of having COVID vaccinations,” which “offers a little bit of reassurance” that there can be an immune response in people with vasculitis.

Although results of the cross-sectional study showed that there was a significant dampening effect of rituximab treatment on the immune response, “I don’t think it’s an isolated effect in our [vasculitis] patients,” Smith suggested, adding the results were “probably still relevant to patients who receive routine dosing of rituximab for other conditions.”

Neutralizing antibody titers were consistently lower among individuals who had been treated with rituximab vs those who had not, with treatment in the past 18 months found to significantly impair immunogenicity.

The ADCC response was better preserved than the neutralizing antibody response, Gupta said, although it was still significantly lower in the rituximab-treated than in the non–rituximab-treated patients.

When to Vaccinate in Vasculitis?

Regarding when to give vaccines to people with vasculitis, Smith said: “Current recommendations are that patients should receive any vaccines that they’re offered routinely, whether that be COVID vaccines, flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccines.”

As for the timing of those vaccinations, she observed that the current thinking was that vaccinations should “ideally be at least 1 month before a rituximab treatment, and ideally 3-4 [months] after their last dose. However, as many patients are on a 6-month dosing cycle, it can be difficult for some of them to find a suitable time window to have the COVID vaccine when it is offered.”

Additional precautions, such as wearing masks in crowded places and avoiding visits to acutely unwell friends or relatives, may still be prudent, Smith acknowledged, but he was clear that people should not be locking themselves away as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When advising patients, “our general recommendation is that it is better to have a vaccine than not, but we can’t guarantee how well you will respond to it, but some response is better than none,” Smith said.

The study was independently supported. Gupta had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Smith was a coauthor of the paper and has received research grant funding from Union Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline/Vir Biotechnology, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, and Vasculitis UK. Another coauthor reported receiving research grants from CSL Vifor, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board, consultancy, and lecture fees from Roche and CSL Vifor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SCIENCE ADVANCES

New Five-Type Index Provides Doctors Guide for Long COVID

A new analysis of long-COVID patients has identified five distinct subtypes that researchers say will help doctors diagnose the condition.

The new five-type index, developed by federal researchers with the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER COVID Initiative, identified the most common symptoms in 14,000 people with long COVID, with data from an additional 4000 people added to the updated 2024 index.

By using the index, physicians and researchers can better understand the condition, which is difficult to treat and diagnose because no standard definitions or therapies have been developed. Doctors can use the index to offer more targeted care and help patients manage their symptoms more effectively.

The index may also help researchers find more treatments for long COVID. Because long COVID can affect so many different parts of the body, it will take time to fully understand how to treat it, but studies like this are making progress in the right direction, experts said.

This new index uses an updated point system, where points are allotted to each symptom in a list of the 44 most reported symptoms in people with likely long COVID based on how often they occur. Among people in the study with prior COVID infection, 2213 (18%) met the threshold for long COVID.

The 44 most common symptoms were then distributed among 5 subtypes, with each representing a difference in impact on quality of life and overall health. The most common symptoms were fatigue (85.8%), postexertional malaise (87.4%), and postexertional soreness (75.0%) — where persistent fatigue and discomfort occur after physical or mental exertion — dizziness (65.8%), brain fog (63.8%), gastrointestinal symptoms (59.3%), and palpitations (58%).

For those with prior COVID infection, symptoms were more prevalent in all cases.

Subtype 1

Those grouped into subtype 1 did not report a high incidence of impact on quality of life, physical health, or daily function. Only 21% of people in subtype 1 reported a “poor or fair quality of life.”

A change in smell or taste — usually a symptom that’s bothersome but doesn’t seriously impact overall health — was most present in subtype 1, with 100% of people in subtype 1 reporting it.

The only other symptoms in over 50% of people with subtype 1— which were 490 of the 2213 with prior COVID infection — were fatigue (66%), postexertional malaise (53%), and postexertional soreness (55%).

Though these two symptoms can certainly impact quality of life, they became much more prevalent in other subtypes.

Subtype 2

The prevalence of possibly debilitating symptoms like postexertional malaise (94%), fatigue (81%), and chronic cough (100%) rose dramatically in people grouped into subtype 2.

Plus, 25% of people in subtype 2 reported a “poor or fair quality of life. Postexertional malaise, I think, is probably one of the most debilitating of the symptoms. When somebody comes in and tells me that they’re tired and I think they might have long COVID, the first thing I try to do is see if it is postexertional malaise vs just postinfectious fatigue,” said Lisa Sanders, MD, medical director of Yale’s Long Covid Multidisciplinary Care Center in New Haven, Connecticut.

Postinfectious fatigue usually resolves much more quickly than postexertional malaise. The latter accounts for several symptoms as also associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is a chronic illness that causes severe fatigue and makes it difficult for sufferers to perform routine, daily activities.

“Postexertional malaise is an additive symptom of ME/CFS, and that can take a long time to resolve,” Sanders added.

The similarity between these two symptoms highlights the importance that physicians must place in scrutinizing symptoms to a high degree when they suspect a patient of having long COVID, experts said. By doing so, clinicians can unveil the mask of overlapping symptoms between long COVID symptoms and symptoms of other illnesses.

Subtype 3

About 37% of people grouped in subtype 3 reported a poor or fair quality of life, a significant rise from subtypes 1 and 2.

Fatigue symptoms were reported by 92%, whereas 82% reported postexertional soreness, and 70% reported dizziness. Additionally, 100% of people in subtype 3 reported brain fog as a symptom.

Sanders said these symptoms are also common in people with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. This condition results from a reduced volume of blood returning to the heart after standing up, which leads to an abnormally fast heart rate. Palpitations and fainting can then occur.

Brain fog can be especially debilitating in people who are used to multitasking. With brain fog, people accustomed to easily alternating between tasks or doing multiple tasks at once can only do one thing at a time. This can cause stress and an overload of thoughts, even precipitating a change in careers if severe enough.

Though brain fog tends to resolve within 6-9 months after infection, it can last up to 18 months or more. Experts say doctors should always be on the lookout if a patient complains they have trouble concentrating or multitasking in the months after a COVID infection. A neurological exam and cognitive testing can identify abnormalities in brain function.

Subtype 4

About 40% of people in the study grouped into subtype 4 reported a poor or fair quality of life, a modest increase from those with subtype 3. About 65% reported symptoms of brain fog and 92% reported palpitations.

Dizziness was also prevalent at 71%, whereas 60% reported gastrointestinal issues, and 36% said they experienced fever, sweats, and chills.

Nearly 700 of the 2213 people fell into this subtype group, by far the highest number.

Subtype 5

A whopping 66% of people in subtype 5 reported a poor to fair quality of life. These people usually reported multisystem symptoms.

In terms of prevalence rises across the spectrum of 44 common long-COVID symptoms, 99% reported shortness of breath; 98%, postexertional soreness; 94%, dizziness; 92%, postexertional malaise; 80%, GI problems; 78%, weakness; and 69%, chest pain.

A higher proportion of Hispanic and multiracial participants were classified as having subtype 5. Also, according to the study, “higher proportions of unvaccinated participants and those with SARS-CoV-2 infection before circulation of the Omicron variant were in subtype 5.”

This suggests the severity of the Delta variant of COVID-19 be linked to some of the worst long COVID symptoms, but further study would have to be done to conclusively determine may be just a correlation.

When Do Symptoms Resolve?

According to Sanders, around 17 million Americans are thought to have long COVID. Although 90%-100% of people typically recover within 3 years, that still leaves possibly around 5% of those who don’t recover.

“What people usually say is, ‘I got COVID, and I never quite recovered,” Sanders said.

“Five percent of 17 million turns out to be a lot. It’s a lot of suffering,” she added. “I would say that the most common symptoms are fatigue, brain fog, anosmia or dysgeusia, and sleep disorders,” as evidenced by the high percentage of people in certain subtypes of the study reporting a poor quality of life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new analysis of long-COVID patients has identified five distinct subtypes that researchers say will help doctors diagnose the condition.

The new five-type index, developed by federal researchers with the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER COVID Initiative, identified the most common symptoms in 14,000 people with long COVID, with data from an additional 4000 people added to the updated 2024 index.

By using the index, physicians and researchers can better understand the condition, which is difficult to treat and diagnose because no standard definitions or therapies have been developed. Doctors can use the index to offer more targeted care and help patients manage their symptoms more effectively.

The index may also help researchers find more treatments for long COVID. Because long COVID can affect so many different parts of the body, it will take time to fully understand how to treat it, but studies like this are making progress in the right direction, experts said.

This new index uses an updated point system, where points are allotted to each symptom in a list of the 44 most reported symptoms in people with likely long COVID based on how often they occur. Among people in the study with prior COVID infection, 2213 (18%) met the threshold for long COVID.

The 44 most common symptoms were then distributed among 5 subtypes, with each representing a difference in impact on quality of life and overall health. The most common symptoms were fatigue (85.8%), postexertional malaise (87.4%), and postexertional soreness (75.0%) — where persistent fatigue and discomfort occur after physical or mental exertion — dizziness (65.8%), brain fog (63.8%), gastrointestinal symptoms (59.3%), and palpitations (58%).

For those with prior COVID infection, symptoms were more prevalent in all cases.

Subtype 1

Those grouped into subtype 1 did not report a high incidence of impact on quality of life, physical health, or daily function. Only 21% of people in subtype 1 reported a “poor or fair quality of life.”

A change in smell or taste — usually a symptom that’s bothersome but doesn’t seriously impact overall health — was most present in subtype 1, with 100% of people in subtype 1 reporting it.

The only other symptoms in over 50% of people with subtype 1— which were 490 of the 2213 with prior COVID infection — were fatigue (66%), postexertional malaise (53%), and postexertional soreness (55%).

Though these two symptoms can certainly impact quality of life, they became much more prevalent in other subtypes.

Subtype 2

The prevalence of possibly debilitating symptoms like postexertional malaise (94%), fatigue (81%), and chronic cough (100%) rose dramatically in people grouped into subtype 2.

Plus, 25% of people in subtype 2 reported a “poor or fair quality of life. Postexertional malaise, I think, is probably one of the most debilitating of the symptoms. When somebody comes in and tells me that they’re tired and I think they might have long COVID, the first thing I try to do is see if it is postexertional malaise vs just postinfectious fatigue,” said Lisa Sanders, MD, medical director of Yale’s Long Covid Multidisciplinary Care Center in New Haven, Connecticut.

Postinfectious fatigue usually resolves much more quickly than postexertional malaise. The latter accounts for several symptoms as also associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is a chronic illness that causes severe fatigue and makes it difficult for sufferers to perform routine, daily activities.

“Postexertional malaise is an additive symptom of ME/CFS, and that can take a long time to resolve,” Sanders added.

The similarity between these two symptoms highlights the importance that physicians must place in scrutinizing symptoms to a high degree when they suspect a patient of having long COVID, experts said. By doing so, clinicians can unveil the mask of overlapping symptoms between long COVID symptoms and symptoms of other illnesses.

Subtype 3

About 37% of people grouped in subtype 3 reported a poor or fair quality of life, a significant rise from subtypes 1 and 2.

Fatigue symptoms were reported by 92%, whereas 82% reported postexertional soreness, and 70% reported dizziness. Additionally, 100% of people in subtype 3 reported brain fog as a symptom.

Sanders said these symptoms are also common in people with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. This condition results from a reduced volume of blood returning to the heart after standing up, which leads to an abnormally fast heart rate. Palpitations and fainting can then occur.

Brain fog can be especially debilitating in people who are used to multitasking. With brain fog, people accustomed to easily alternating between tasks or doing multiple tasks at once can only do one thing at a time. This can cause stress and an overload of thoughts, even precipitating a change in careers if severe enough.

Though brain fog tends to resolve within 6-9 months after infection, it can last up to 18 months or more. Experts say doctors should always be on the lookout if a patient complains they have trouble concentrating or multitasking in the months after a COVID infection. A neurological exam and cognitive testing can identify abnormalities in brain function.

Subtype 4

About 40% of people in the study grouped into subtype 4 reported a poor or fair quality of life, a modest increase from those with subtype 3. About 65% reported symptoms of brain fog and 92% reported palpitations.

Dizziness was also prevalent at 71%, whereas 60% reported gastrointestinal issues, and 36% said they experienced fever, sweats, and chills.

Nearly 700 of the 2213 people fell into this subtype group, by far the highest number.

Subtype 5

A whopping 66% of people in subtype 5 reported a poor to fair quality of life. These people usually reported multisystem symptoms.

In terms of prevalence rises across the spectrum of 44 common long-COVID symptoms, 99% reported shortness of breath; 98%, postexertional soreness; 94%, dizziness; 92%, postexertional malaise; 80%, GI problems; 78%, weakness; and 69%, chest pain.

A higher proportion of Hispanic and multiracial participants were classified as having subtype 5. Also, according to the study, “higher proportions of unvaccinated participants and those with SARS-CoV-2 infection before circulation of the Omicron variant were in subtype 5.”

This suggests the severity of the Delta variant of COVID-19 be linked to some of the worst long COVID symptoms, but further study would have to be done to conclusively determine may be just a correlation.

When Do Symptoms Resolve?

According to Sanders, around 17 million Americans are thought to have long COVID. Although 90%-100% of people typically recover within 3 years, that still leaves possibly around 5% of those who don’t recover.

“What people usually say is, ‘I got COVID, and I never quite recovered,” Sanders said.

“Five percent of 17 million turns out to be a lot. It’s a lot of suffering,” she added. “I would say that the most common symptoms are fatigue, brain fog, anosmia or dysgeusia, and sleep disorders,” as evidenced by the high percentage of people in certain subtypes of the study reporting a poor quality of life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new analysis of long-COVID patients has identified five distinct subtypes that researchers say will help doctors diagnose the condition.

The new five-type index, developed by federal researchers with the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER COVID Initiative, identified the most common symptoms in 14,000 people with long COVID, with data from an additional 4000 people added to the updated 2024 index.

By using the index, physicians and researchers can better understand the condition, which is difficult to treat and diagnose because no standard definitions or therapies have been developed. Doctors can use the index to offer more targeted care and help patients manage their symptoms more effectively.

The index may also help researchers find more treatments for long COVID. Because long COVID can affect so many different parts of the body, it will take time to fully understand how to treat it, but studies like this are making progress in the right direction, experts said.

This new index uses an updated point system, where points are allotted to each symptom in a list of the 44 most reported symptoms in people with likely long COVID based on how often they occur. Among people in the study with prior COVID infection, 2213 (18%) met the threshold for long COVID.

The 44 most common symptoms were then distributed among 5 subtypes, with each representing a difference in impact on quality of life and overall health. The most common symptoms were fatigue (85.8%), postexertional malaise (87.4%), and postexertional soreness (75.0%) — where persistent fatigue and discomfort occur after physical or mental exertion — dizziness (65.8%), brain fog (63.8%), gastrointestinal symptoms (59.3%), and palpitations (58%).

For those with prior COVID infection, symptoms were more prevalent in all cases.

Subtype 1

Those grouped into subtype 1 did not report a high incidence of impact on quality of life, physical health, or daily function. Only 21% of people in subtype 1 reported a “poor or fair quality of life.”

A change in smell or taste — usually a symptom that’s bothersome but doesn’t seriously impact overall health — was most present in subtype 1, with 100% of people in subtype 1 reporting it.

The only other symptoms in over 50% of people with subtype 1— which were 490 of the 2213 with prior COVID infection — were fatigue (66%), postexertional malaise (53%), and postexertional soreness (55%).

Though these two symptoms can certainly impact quality of life, they became much more prevalent in other subtypes.

Subtype 2

The prevalence of possibly debilitating symptoms like postexertional malaise (94%), fatigue (81%), and chronic cough (100%) rose dramatically in people grouped into subtype 2.

Plus, 25% of people in subtype 2 reported a “poor or fair quality of life. Postexertional malaise, I think, is probably one of the most debilitating of the symptoms. When somebody comes in and tells me that they’re tired and I think they might have long COVID, the first thing I try to do is see if it is postexertional malaise vs just postinfectious fatigue,” said Lisa Sanders, MD, medical director of Yale’s Long Covid Multidisciplinary Care Center in New Haven, Connecticut.

Postinfectious fatigue usually resolves much more quickly than postexertional malaise. The latter accounts for several symptoms as also associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is a chronic illness that causes severe fatigue and makes it difficult for sufferers to perform routine, daily activities.

“Postexertional malaise is an additive symptom of ME/CFS, and that can take a long time to resolve,” Sanders added.

The similarity between these two symptoms highlights the importance that physicians must place in scrutinizing symptoms to a high degree when they suspect a patient of having long COVID, experts said. By doing so, clinicians can unveil the mask of overlapping symptoms between long COVID symptoms and symptoms of other illnesses.

Subtype 3

About 37% of people grouped in subtype 3 reported a poor or fair quality of life, a significant rise from subtypes 1 and 2.

Fatigue symptoms were reported by 92%, whereas 82% reported postexertional soreness, and 70% reported dizziness. Additionally, 100% of people in subtype 3 reported brain fog as a symptom.

Sanders said these symptoms are also common in people with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. This condition results from a reduced volume of blood returning to the heart after standing up, which leads to an abnormally fast heart rate. Palpitations and fainting can then occur.

Brain fog can be especially debilitating in people who are used to multitasking. With brain fog, people accustomed to easily alternating between tasks or doing multiple tasks at once can only do one thing at a time. This can cause stress and an overload of thoughts, even precipitating a change in careers if severe enough.

Though brain fog tends to resolve within 6-9 months after infection, it can last up to 18 months or more. Experts say doctors should always be on the lookout if a patient complains they have trouble concentrating or multitasking in the months after a COVID infection. A neurological exam and cognitive testing can identify abnormalities in brain function.

Subtype 4

About 40% of people in the study grouped into subtype 4 reported a poor or fair quality of life, a modest increase from those with subtype 3. About 65% reported symptoms of brain fog and 92% reported palpitations.

Dizziness was also prevalent at 71%, whereas 60% reported gastrointestinal issues, and 36% said they experienced fever, sweats, and chills.

Nearly 700 of the 2213 people fell into this subtype group, by far the highest number.

Subtype 5

A whopping 66% of people in subtype 5 reported a poor to fair quality of life. These people usually reported multisystem symptoms.

In terms of prevalence rises across the spectrum of 44 common long-COVID symptoms, 99% reported shortness of breath; 98%, postexertional soreness; 94%, dizziness; 92%, postexertional malaise; 80%, GI problems; 78%, weakness; and 69%, chest pain.

A higher proportion of Hispanic and multiracial participants were classified as having subtype 5. Also, according to the study, “higher proportions of unvaccinated participants and those with SARS-CoV-2 infection before circulation of the Omicron variant were in subtype 5.”

This suggests the severity of the Delta variant of COVID-19 be linked to some of the worst long COVID symptoms, but further study would have to be done to conclusively determine may be just a correlation.

When Do Symptoms Resolve?

According to Sanders, around 17 million Americans are thought to have long COVID. Although 90%-100% of people typically recover within 3 years, that still leaves possibly around 5% of those who don’t recover.

“What people usually say is, ‘I got COVID, and I never quite recovered,” Sanders said.

“Five percent of 17 million turns out to be a lot. It’s a lot of suffering,” she added. “I would say that the most common symptoms are fatigue, brain fog, anosmia or dysgeusia, and sleep disorders,” as evidenced by the high percentage of people in certain subtypes of the study reporting a poor quality of life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Next-Gen Sequencing Tumor Testing Remains Low in Prostate and Urothelial Cancer Cases

This article is a based on a video essay. The transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to discuss what I think is a very interesting analysis that we need to see much more of. It’s perhaps not surprising, but the data, I think, are sobering. The paper was published in JAMA Network Open, entitled, “Trends and Disparities in Next-Generation Sequencing in Metastatic Prostate and Urothelial Cancers.”

As I think most of the listening audience is aware, we are in the midst of an ongoing — I would argue, accelerating — revolution in our understanding of cancer, its development and treatments, based upon our characterization at the molecular level of individual cancers.

This, of course, is changing the treatment paradigms and the drugs that we might have available in the first-, second-, and third-line settings. The question to be asked is, how are we, at a clinical level, keeping up with all of these changes, like those approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and new diagnostic testing with a variety of molecular platforms?

This particular analysis looked at that specific question in metastatic prostate cancer and urothelial malignancies, obviously including bladder cancer. With the new approvals — including tumor agnostic testing, very specific testing, and very molecularly based drugs that are approved for particular abnormalities — they looked at the percentages of patients and the potential disparities in terms of the testing that has been performed.

There were 11,927 patients with prostate cancer. There were 6490 patients with advanced urothelial malignancies; the majority of these were male, but there were females included in this group.

The researchers looked at 2015 vs 2022 data. It’s not 2024 data, but it goes all the way to the end of 2022, so, not that long ago. In the metastatic prostate cancer group, 19% of patients had undergone molecular testing or next-generation sequencing in 2015.

By 2022, that number had increased, but only to 27%. Three out of four patients with metastatic prostate cancer had not undergone testing to know whether they were potential candidates for specific therapies. I won’t even get into the question of potential germline abnormalities that might be observed that are relevant for other discussions.

Among patients with urothelial cancer, in 2015, 14% had undergone such testing. By 2022, this number was substantially increased to 46.6%, but still, that’s less than 1 out of 2 patients. More than 50% of patients had not undergone the testing, and yet we have therapy that might be available for these populations based on such testing.

I should add that the population of Black, African American, and Hispanic patients was actually considerably lower, percentage-wise, than the numbers that I’ve quoted.

Clearly, there are explanations. There are socioeconomic explanations and insurance coverage explanations. However, the bottom line is that we have therapies available today, and we’ll have more in the future, that are based on knowledge of this testing.

Based on these data, which most recently included 2022 — we’ll see where we are in 2024 and 2025, and with other types — more than half of patients are not getting the testing to know if this is relevant for them and their care.

These are major questions that need to be addressed. Hopefully, answers will be forthcoming and we will see in the future that these percentages will be much higher for the benefit of our patients.

Dr Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article is a based on a video essay. The transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to discuss what I think is a very interesting analysis that we need to see much more of. It’s perhaps not surprising, but the data, I think, are sobering. The paper was published in JAMA Network Open, entitled, “Trends and Disparities in Next-Generation Sequencing in Metastatic Prostate and Urothelial Cancers.”

As I think most of the listening audience is aware, we are in the midst of an ongoing — I would argue, accelerating — revolution in our understanding of cancer, its development and treatments, based upon our characterization at the molecular level of individual cancers.

This, of course, is changing the treatment paradigms and the drugs that we might have available in the first-, second-, and third-line settings. The question to be asked is, how are we, at a clinical level, keeping up with all of these changes, like those approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and new diagnostic testing with a variety of molecular platforms?

This particular analysis looked at that specific question in metastatic prostate cancer and urothelial malignancies, obviously including bladder cancer. With the new approvals — including tumor agnostic testing, very specific testing, and very molecularly based drugs that are approved for particular abnormalities — they looked at the percentages of patients and the potential disparities in terms of the testing that has been performed.

There were 11,927 patients with prostate cancer. There were 6490 patients with advanced urothelial malignancies; the majority of these were male, but there were females included in this group.

The researchers looked at 2015 vs 2022 data. It’s not 2024 data, but it goes all the way to the end of 2022, so, not that long ago. In the metastatic prostate cancer group, 19% of patients had undergone molecular testing or next-generation sequencing in 2015.

By 2022, that number had increased, but only to 27%. Three out of four patients with metastatic prostate cancer had not undergone testing to know whether they were potential candidates for specific therapies. I won’t even get into the question of potential germline abnormalities that might be observed that are relevant for other discussions.

Among patients with urothelial cancer, in 2015, 14% had undergone such testing. By 2022, this number was substantially increased to 46.6%, but still, that’s less than 1 out of 2 patients. More than 50% of patients had not undergone the testing, and yet we have therapy that might be available for these populations based on such testing.

I should add that the population of Black, African American, and Hispanic patients was actually considerably lower, percentage-wise, than the numbers that I’ve quoted.

Clearly, there are explanations. There are socioeconomic explanations and insurance coverage explanations. However, the bottom line is that we have therapies available today, and we’ll have more in the future, that are based on knowledge of this testing.

Based on these data, which most recently included 2022 — we’ll see where we are in 2024 and 2025, and with other types — more than half of patients are not getting the testing to know if this is relevant for them and their care.

These are major questions that need to be addressed. Hopefully, answers will be forthcoming and we will see in the future that these percentages will be much higher for the benefit of our patients.

Dr Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article is a based on a video essay. The transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to discuss what I think is a very interesting analysis that we need to see much more of. It’s perhaps not surprising, but the data, I think, are sobering. The paper was published in JAMA Network Open, entitled, “Trends and Disparities in Next-Generation Sequencing in Metastatic Prostate and Urothelial Cancers.”

As I think most of the listening audience is aware, we are in the midst of an ongoing — I would argue, accelerating — revolution in our understanding of cancer, its development and treatments, based upon our characterization at the molecular level of individual cancers.

This, of course, is changing the treatment paradigms and the drugs that we might have available in the first-, second-, and third-line settings. The question to be asked is, how are we, at a clinical level, keeping up with all of these changes, like those approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and new diagnostic testing with a variety of molecular platforms?

This particular analysis looked at that specific question in metastatic prostate cancer and urothelial malignancies, obviously including bladder cancer. With the new approvals — including tumor agnostic testing, very specific testing, and very molecularly based drugs that are approved for particular abnormalities — they looked at the percentages of patients and the potential disparities in terms of the testing that has been performed.

There were 11,927 patients with prostate cancer. There were 6490 patients with advanced urothelial malignancies; the majority of these were male, but there were females included in this group.

The researchers looked at 2015 vs 2022 data. It’s not 2024 data, but it goes all the way to the end of 2022, so, not that long ago. In the metastatic prostate cancer group, 19% of patients had undergone molecular testing or next-generation sequencing in 2015.

By 2022, that number had increased, but only to 27%. Three out of four patients with metastatic prostate cancer had not undergone testing to know whether they were potential candidates for specific therapies. I won’t even get into the question of potential germline abnormalities that might be observed that are relevant for other discussions.

Among patients with urothelial cancer, in 2015, 14% had undergone such testing. By 2022, this number was substantially increased to 46.6%, but still, that’s less than 1 out of 2 patients. More than 50% of patients had not undergone the testing, and yet we have therapy that might be available for these populations based on such testing.

I should add that the population of Black, African American, and Hispanic patients was actually considerably lower, percentage-wise, than the numbers that I’ve quoted.

Clearly, there are explanations. There are socioeconomic explanations and insurance coverage explanations. However, the bottom line is that we have therapies available today, and we’ll have more in the future, that are based on knowledge of this testing.

Based on these data, which most recently included 2022 — we’ll see where we are in 2024 and 2025, and with other types — more than half of patients are not getting the testing to know if this is relevant for them and their care.

These are major questions that need to be addressed. Hopefully, answers will be forthcoming and we will see in the future that these percentages will be much higher for the benefit of our patients.

Dr Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Navigating Esophageal Dysfunction in Immune and Infectious Disorders: AGA Clinical Practice Update

“Many different disorders can lead to esophageal dysfunction, which is characterized by symptoms including dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain and heartburn. These symptoms can be caused either by immune or infectious conditions and can either be localized to the esophagus or part of a larger systemic process,” co–first author Emily McGowan, MD, PhD, with the division of allergy and immunology, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, said in an AGA podcast.

However, without a “high index of suspicion,” these conditions can be overlooked, leading to delays in diagnosis and unnecessary procedures. “With this clinical practice update, we wanted to help providers more readily recognize these conditions so that patients can be diagnosed and treated earlier in the course of their disease,” McGowan explained.

“This is a fantastic review that highlights how many different systemic disorders can affect the esophagus,” Scott Gabbard, MD, gastroenterologist and section head at the Center for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, who wasn’t involved in the review, said in an interview.

“Honestly, for the practicing gastroenterologist, this is one of those reviews that I could envision someone either saving to his or her desktop for reference or printing it and pinning it next to his or her desk,” Gabbard said.

Best Practice Advice

The clinical practice update is published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. It includes 10 “best practice advice” statements and a table highlighting “important” considerations when evaluating patients with esophageal dysfunction.

The review authors note that esophageal dysfunction may result from localized infections — most commonly Candida, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus — or systemic immune-mediated diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

They advise clinicians to identify if there are risks for inflammatory or infectious possibilities for a patient’s esophageal symptoms and investigate for these disorders as a potential cause of esophageal dysfunction.

Once esophageal infection is identified, it’s important to identify whether accompanying signs and symptoms point to immunocompromise leading to a more systemic infection. Consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended to guide appropriate treatment, the authors said.

If symptoms fail to improve after therapy for infectious esophagitis, the patient should be evaluated for refractory infection or additional underlying sources of esophageal and immunologic dysfunction is advised.

It’s also important to recognize that patients with EoE who continue to have symptoms of esophageal dysfunction despite histologic and endoscopic disease remission, may develop a motility disorder and evaluation of esophageal motility may be warranted, the authors said.

In patients with histologic and endoscopic features of lymphocytic esophagitis, treatment of lymphocytic-related inflammation with proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy or swallowed topical corticosteroids and esophageal dilation as needed should be considered.

In patients who present with esophageal symptoms in the setting of hypereosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count > 1500 cells/uL), the authors advise further workup of non-EoE eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis should be considered, with consultation with an allergy/immunology specialist if helpful.

In patients with rheumatologic diseases, especially SSc and MCTD, it’s important to be aware that esophageal symptoms can occur because of involvement of the esophageal muscle layer, resulting in dysmotility and/or incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, they said.

In the setting of Crohn’s disease, some patients can develop esophageal involvement from inflammation, stricturing, or fistulizing changes with granulomas seen histologically. Esophageal manifestations of Crohn’s disease tend to occur in patients with active intestinal disease.

In patients with dermatologic diseases of lichen planus or bullous disorders, dysphagia can occur because of endoscopically visible esophageal mucosal involvement. Esophageal lichen planus, in particular, can occur without skin involvement and can be difficult to define on esophageal histopathology.

The authors also advise clinicians to consider infectious and inflammatory causes of secondary achalasia during initial evaluation.

“Achalasia and EoE might coexist more commonly than what gastroenterologists think, especially in younger patients,” co–first author Chanakyaram Reddy, MD, a gastroenterologist with Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, said in the AGA podcast.

He noted that in a recent population-based study, the estimated relative risk of EoE was over 30-fold higher in patients with achalasia aged ≤ 40 years.

“In any suspected achalasia case, it would be wise to obtain biopsies throughout the entire esophagus when the patient is off confounding medications such as PPI therapy to establish if significant esophageal eosinophilia is coexistent,” Reddy said.

“If EoE-level eosinophilia is found, it would be reasonable to consider treating medically for EoE prior to committing to achalasia-specific interventions, which often involve permanent disruption of the esophageal muscle layer,” he added.

Gabbard said this review helps the clinician think beyond gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) — the most common cause of esophageal dysfunction — and consider other causes for esophageal dysfunction.

“We are seeing more complex disorders affect the esophagus. It’s not just GERD and you absolutely need a high index of suspicion because you can find varying disorders to blame for many esophageal symptoms that could otherwise be thought to be just reflux,” he said.

This research had no commercial funding. Disclosures for the authors are listed with the original article. Gabbard had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“Many different disorders can lead to esophageal dysfunction, which is characterized by symptoms including dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain and heartburn. These symptoms can be caused either by immune or infectious conditions and can either be localized to the esophagus or part of a larger systemic process,” co–first author Emily McGowan, MD, PhD, with the division of allergy and immunology, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, said in an AGA podcast.

However, without a “high index of suspicion,” these conditions can be overlooked, leading to delays in diagnosis and unnecessary procedures. “With this clinical practice update, we wanted to help providers more readily recognize these conditions so that patients can be diagnosed and treated earlier in the course of their disease,” McGowan explained.

“This is a fantastic review that highlights how many different systemic disorders can affect the esophagus,” Scott Gabbard, MD, gastroenterologist and section head at the Center for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, who wasn’t involved in the review, said in an interview.

“Honestly, for the practicing gastroenterologist, this is one of those reviews that I could envision someone either saving to his or her desktop for reference or printing it and pinning it next to his or her desk,” Gabbard said.

Best Practice Advice

The clinical practice update is published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. It includes 10 “best practice advice” statements and a table highlighting “important” considerations when evaluating patients with esophageal dysfunction.

The review authors note that esophageal dysfunction may result from localized infections — most commonly Candida, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus — or systemic immune-mediated diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

They advise clinicians to identify if there are risks for inflammatory or infectious possibilities for a patient’s esophageal symptoms and investigate for these disorders as a potential cause of esophageal dysfunction.

Once esophageal infection is identified, it’s important to identify whether accompanying signs and symptoms point to immunocompromise leading to a more systemic infection. Consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended to guide appropriate treatment, the authors said.

If symptoms fail to improve after therapy for infectious esophagitis, the patient should be evaluated for refractory infection or additional underlying sources of esophageal and immunologic dysfunction is advised.

It’s also important to recognize that patients with EoE who continue to have symptoms of esophageal dysfunction despite histologic and endoscopic disease remission, may develop a motility disorder and evaluation of esophageal motility may be warranted, the authors said.

In patients with histologic and endoscopic features of lymphocytic esophagitis, treatment of lymphocytic-related inflammation with proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy or swallowed topical corticosteroids and esophageal dilation as needed should be considered.

In patients who present with esophageal symptoms in the setting of hypereosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count > 1500 cells/uL), the authors advise further workup of non-EoE eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis should be considered, with consultation with an allergy/immunology specialist if helpful.

In patients with rheumatologic diseases, especially SSc and MCTD, it’s important to be aware that esophageal symptoms can occur because of involvement of the esophageal muscle layer, resulting in dysmotility and/or incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, they said.

In the setting of Crohn’s disease, some patients can develop esophageal involvement from inflammation, stricturing, or fistulizing changes with granulomas seen histologically. Esophageal manifestations of Crohn’s disease tend to occur in patients with active intestinal disease.

In patients with dermatologic diseases of lichen planus or bullous disorders, dysphagia can occur because of endoscopically visible esophageal mucosal involvement. Esophageal lichen planus, in particular, can occur without skin involvement and can be difficult to define on esophageal histopathology.

The authors also advise clinicians to consider infectious and inflammatory causes of secondary achalasia during initial evaluation.

“Achalasia and EoE might coexist more commonly than what gastroenterologists think, especially in younger patients,” co–first author Chanakyaram Reddy, MD, a gastroenterologist with Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, said in the AGA podcast.

He noted that in a recent population-based study, the estimated relative risk of EoE was over 30-fold higher in patients with achalasia aged ≤ 40 years.

“In any suspected achalasia case, it would be wise to obtain biopsies throughout the entire esophagus when the patient is off confounding medications such as PPI therapy to establish if significant esophageal eosinophilia is coexistent,” Reddy said.

“If EoE-level eosinophilia is found, it would be reasonable to consider treating medically for EoE prior to committing to achalasia-specific interventions, which often involve permanent disruption of the esophageal muscle layer,” he added.

Gabbard said this review helps the clinician think beyond gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) — the most common cause of esophageal dysfunction — and consider other causes for esophageal dysfunction.

“We are seeing more complex disorders affect the esophagus. It’s not just GERD and you absolutely need a high index of suspicion because you can find varying disorders to blame for many esophageal symptoms that could otherwise be thought to be just reflux,” he said.

This research had no commercial funding. Disclosures for the authors are listed with the original article. Gabbard had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“Many different disorders can lead to esophageal dysfunction, which is characterized by symptoms including dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain and heartburn. These symptoms can be caused either by immune or infectious conditions and can either be localized to the esophagus or part of a larger systemic process,” co–first author Emily McGowan, MD, PhD, with the division of allergy and immunology, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, said in an AGA podcast.

However, without a “high index of suspicion,” these conditions can be overlooked, leading to delays in diagnosis and unnecessary procedures. “With this clinical practice update, we wanted to help providers more readily recognize these conditions so that patients can be diagnosed and treated earlier in the course of their disease,” McGowan explained.

“This is a fantastic review that highlights how many different systemic disorders can affect the esophagus,” Scott Gabbard, MD, gastroenterologist and section head at the Center for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, who wasn’t involved in the review, said in an interview.

“Honestly, for the practicing gastroenterologist, this is one of those reviews that I could envision someone either saving to his or her desktop for reference or printing it and pinning it next to his or her desk,” Gabbard said.

Best Practice Advice

The clinical practice update is published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. It includes 10 “best practice advice” statements and a table highlighting “important” considerations when evaluating patients with esophageal dysfunction.

The review authors note that esophageal dysfunction may result from localized infections — most commonly Candida, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus — or systemic immune-mediated diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

They advise clinicians to identify if there are risks for inflammatory or infectious possibilities for a patient’s esophageal symptoms and investigate for these disorders as a potential cause of esophageal dysfunction.

Once esophageal infection is identified, it’s important to identify whether accompanying signs and symptoms point to immunocompromise leading to a more systemic infection. Consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended to guide appropriate treatment, the authors said.

If symptoms fail to improve after therapy for infectious esophagitis, the patient should be evaluated for refractory infection or additional underlying sources of esophageal and immunologic dysfunction is advised.

It’s also important to recognize that patients with EoE who continue to have symptoms of esophageal dysfunction despite histologic and endoscopic disease remission, may develop a motility disorder and evaluation of esophageal motility may be warranted, the authors said.

In patients with histologic and endoscopic features of lymphocytic esophagitis, treatment of lymphocytic-related inflammation with proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy or swallowed topical corticosteroids and esophageal dilation as needed should be considered.

In patients who present with esophageal symptoms in the setting of hypereosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count > 1500 cells/uL), the authors advise further workup of non-EoE eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis should be considered, with consultation with an allergy/immunology specialist if helpful.

In patients with rheumatologic diseases, especially SSc and MCTD, it’s important to be aware that esophageal symptoms can occur because of involvement of the esophageal muscle layer, resulting in dysmotility and/or incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, they said.

In the setting of Crohn’s disease, some patients can develop esophageal involvement from inflammation, stricturing, or fistulizing changes with granulomas seen histologically. Esophageal manifestations of Crohn’s disease tend to occur in patients with active intestinal disease.

In patients with dermatologic diseases of lichen planus or bullous disorders, dysphagia can occur because of endoscopically visible esophageal mucosal involvement. Esophageal lichen planus, in particular, can occur without skin involvement and can be difficult to define on esophageal histopathology.

The authors also advise clinicians to consider infectious and inflammatory causes of secondary achalasia during initial evaluation.

“Achalasia and EoE might coexist more commonly than what gastroenterologists think, especially in younger patients,” co–first author Chanakyaram Reddy, MD, a gastroenterologist with Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, said in the AGA podcast.

He noted that in a recent population-based study, the estimated relative risk of EoE was over 30-fold higher in patients with achalasia aged ≤ 40 years.

“In any suspected achalasia case, it would be wise to obtain biopsies throughout the entire esophagus when the patient is off confounding medications such as PPI therapy to establish if significant esophageal eosinophilia is coexistent,” Reddy said.

“If EoE-level eosinophilia is found, it would be reasonable to consider treating medically for EoE prior to committing to achalasia-specific interventions, which often involve permanent disruption of the esophageal muscle layer,” he added.

Gabbard said this review helps the clinician think beyond gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) — the most common cause of esophageal dysfunction — and consider other causes for esophageal dysfunction.

“We are seeing more complex disorders affect the esophagus. It’s not just GERD and you absolutely need a high index of suspicion because you can find varying disorders to blame for many esophageal symptoms that could otherwise be thought to be just reflux,” he said.

This research had no commercial funding. Disclosures for the authors are listed with the original article. Gabbard had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Finding and Following Your Passion

Dear Friends,

Over the last year, I have been reading more about professional identity and professional branding, all of which have evolved in the setting of social media. However, the root of it remains constant — finding the intersection(s) of what you love. A common problem, especially as a trainee and early-career gastroenterologist, is that you may have many interests: various disease processes, innovation, medical education, leadership development, and much more. Since becoming faculty, I continue to define and refine my professional niche, trying to distinguish my “interests” from “passions.” It is a journey that my mentors advise me not to rush through and I am enjoying every moment of it!

In this issue’s “In Focus,” Dr. Hamza Salim, Dr. Anni Chowdhury, and Dr. Lavanya Viswanathan provide a practical guide for the clinical evaluation of chronic constipation and a systematic approach to treatment.

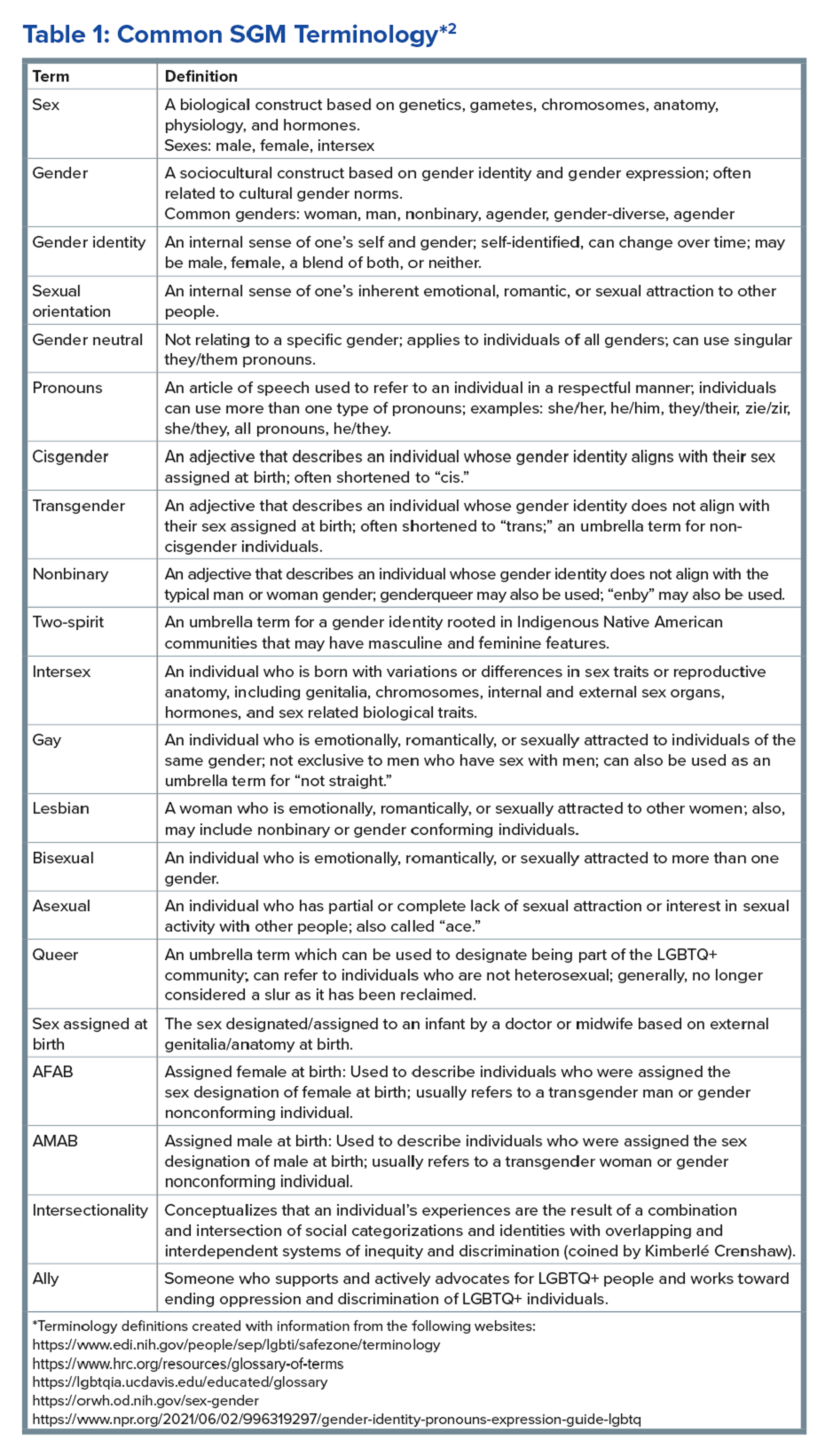

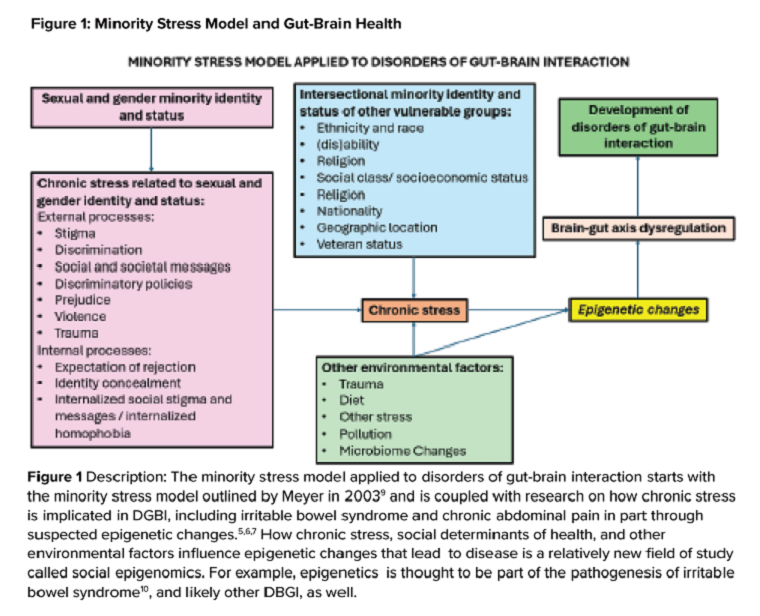

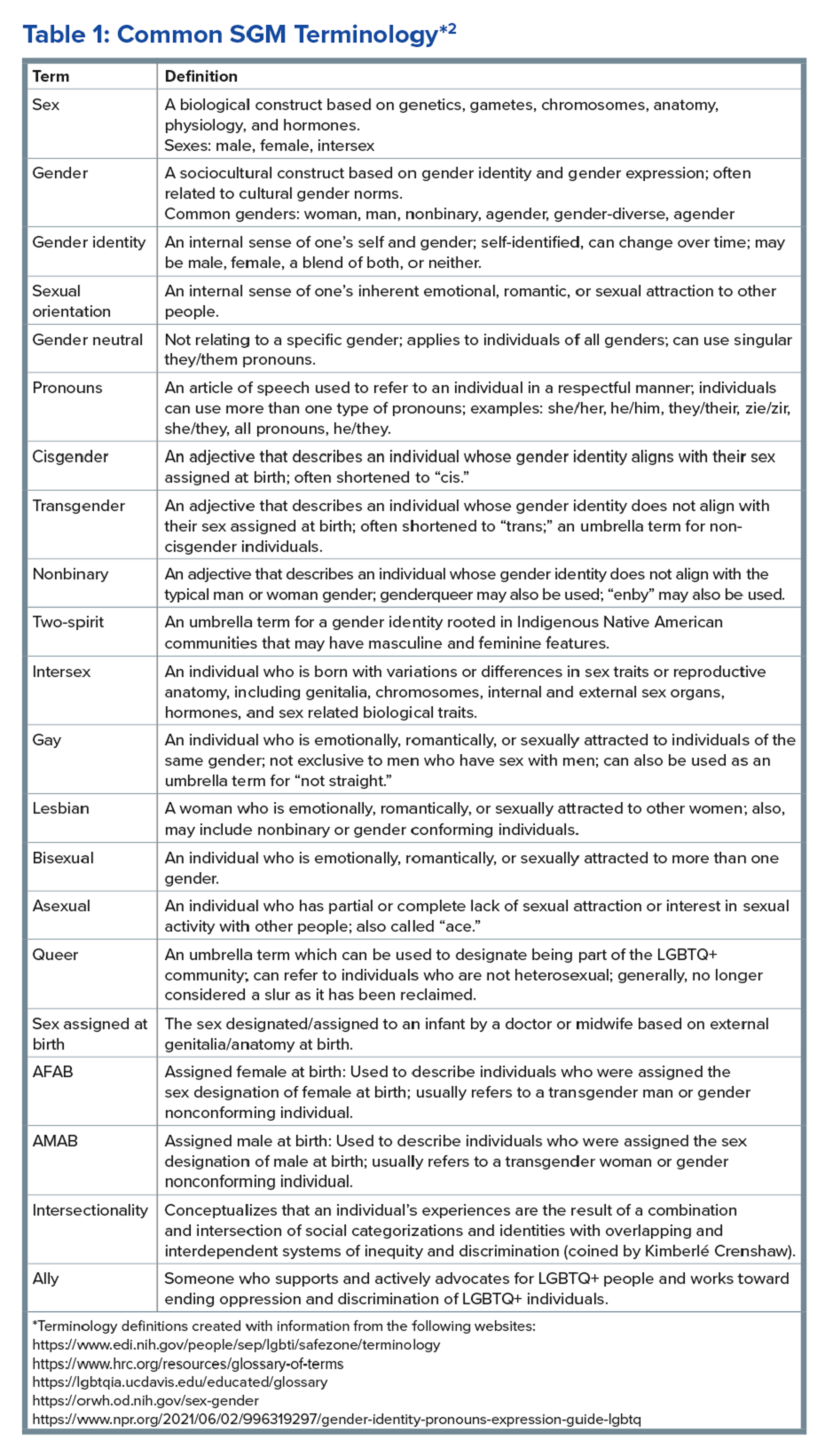

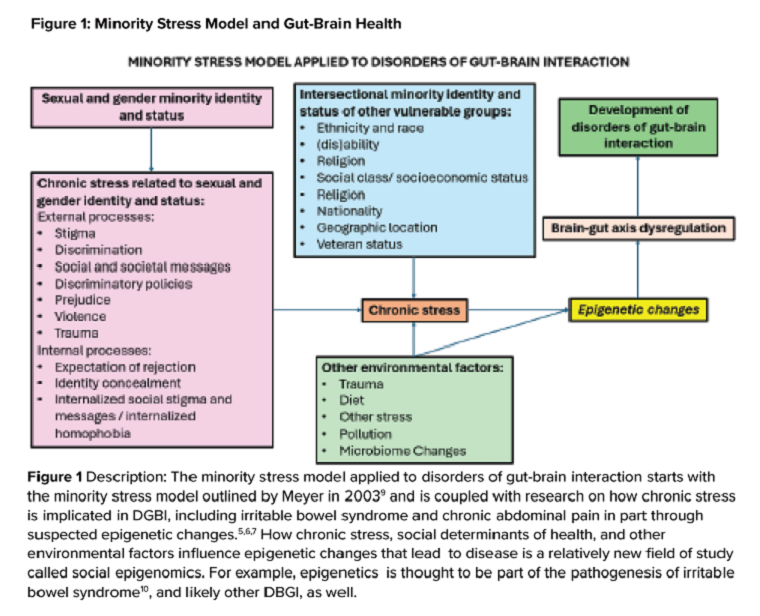

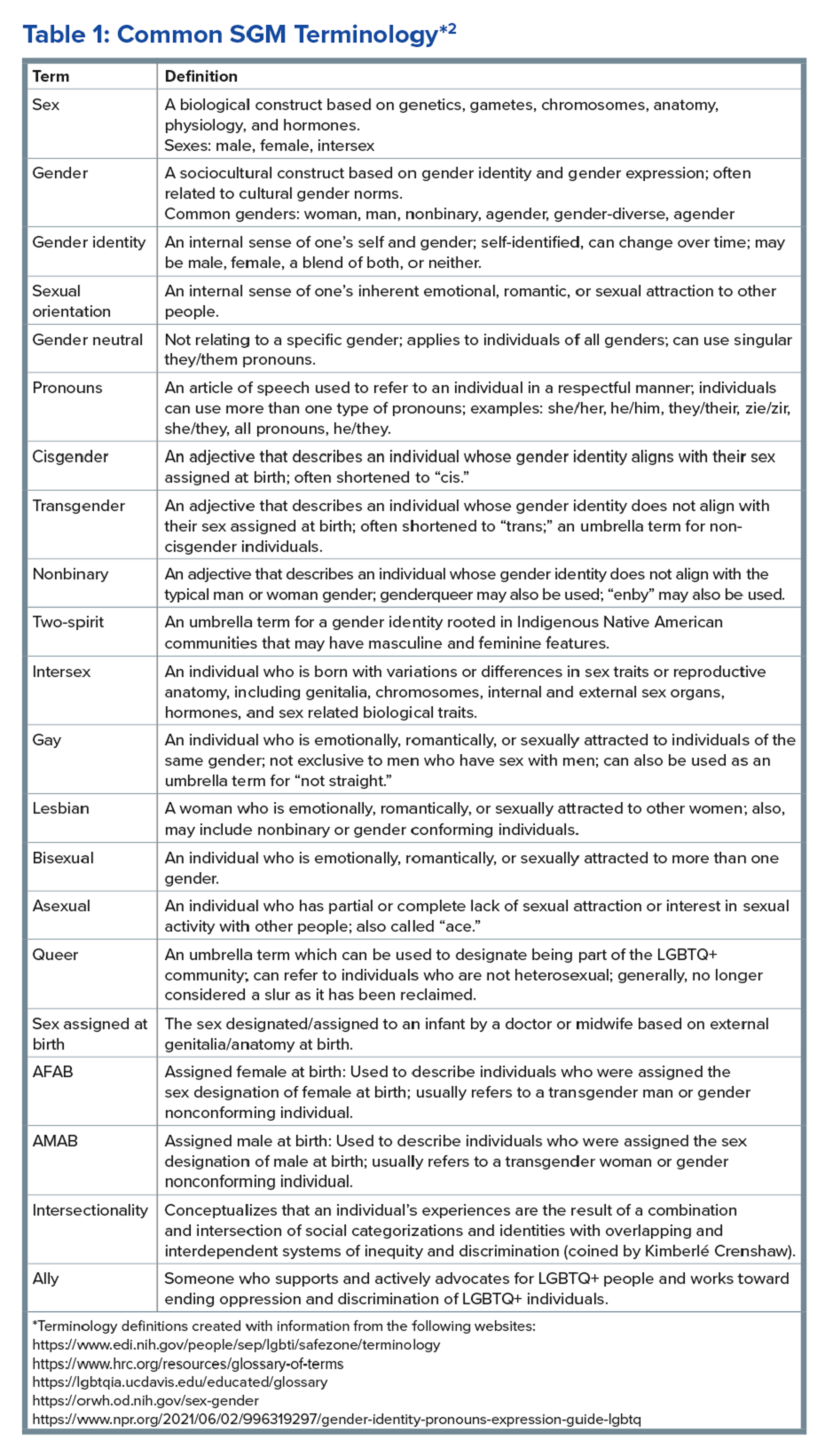

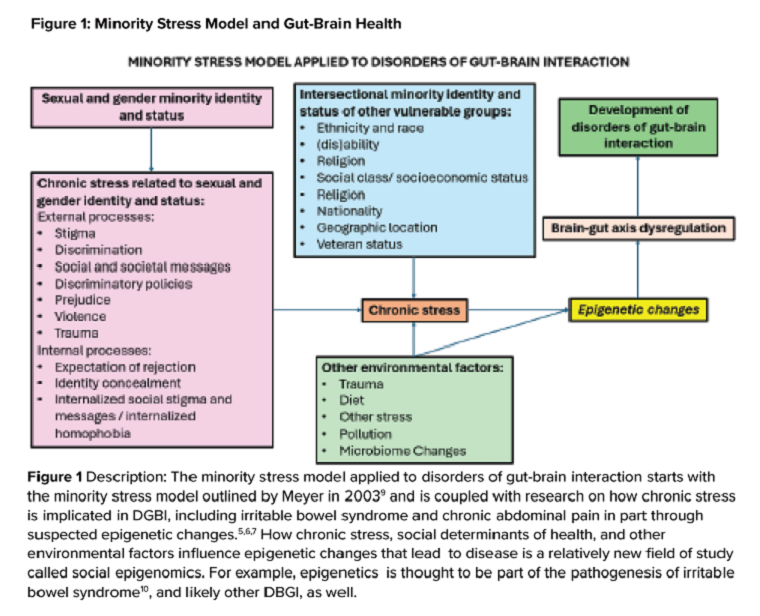

In the first of a two-part series in the “Short Clinical Review” section, Dr. Christopher Velez and Dr. Kara J. Jencks discuss the health inequities among sexual and gender minority (SGM) patients, particularly with disorders of brain-gut interaction (DBGI). They review common SGM terminology, sample verbiage for trauma-informed care, and case presentations to help guide our approach to providing care for SGM patients with DGBI.

The transition from trainee to early faculty may be difficult for those who are interested in research but struggle with the change from being a part of a research team to running one. In the “Early Career” section, Dr. Lauren Feld and colleagues describes her experience establishing a research lab as an early-career academic, from creating a niche to time management and mentorship.

The Federal Trade Commission’s noncompete ban made big news in April 2024 but there is still a lot of gray area for physicians. Dr. Timothy Craig Allen explains the ruling, what it means to physicians, the status of it today, and what the future may hold. Lastly, for “Private Practice Perspectives” in collaboration with Digestive Health Physicians Alliance, I interview Dr. Vasu Appalaneni on her use of artificial intelligence in private practice.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu) or Danielle Kiefer (dkiefer@gastro.org), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: Polyethylene glycol was first used in the 1940s and 1950s to understand the physiology of the intestines, and first published as a compound for colonoscopy bowel preparation in 1981.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,