User login

Open Notes

. While some clinicians consider it an unwelcome intrusion, advocates say it will improve communication and compliance.

Patient access to notes is not new. In many states, patients already have the ability to request copies of their charts, or to access truncated information via clinic websites. The difference is that most patients will now be able to click on a patient portal – such as MyChart, or other similar apps – and gain instantaneous, unfettered access to everything in their records.

Clinicians have traditionally thought of medical notes as private journal entries; but in the last few decades they have become an important component of the documentation necessary for billing, as well as evidence in the event of litigation. Now, with the implementation of the Cures Act, medical notes have evolved into a tool to communicate with the patient, rather than just among health care providers, lawyers, and billing departments.

Supporters contend that this change will make a big difference, because patients will be able to see exactly what their doctors have written, rather than just a list of confusing test results and diagnosis lists in “medicalese.”

OpenNotes, a think tank that has promoted the sharing of clinical notes with patients for years, calls the Cures Act legislation a “new world” where shared notes are valuable tools to improve communication between patients and physicians while strengthening their relationship. They cite evidence indicating that “when health professionals offer patients and families ready access to clinical notes, the quality and safety of care improves.”

Not all doctors are as enthusiastic. Many are concerned that patients might misinterpret what they see in their doctors’ notes, including complex descriptions of clinical assessments and decisions.

Others worry about patients having immediate access to their records, perhaps even before their physicians. The American Academy of Dermatology is working with the American Medical Association and other groups to gather real-world instances where the release of lab results, reports, or notes directly to patients before their physician could review the information with them caused emotional harm or other adverse consequences.

Undoubtedly, there are scenarios where unrestricted display of clinical notes could be problematic. One example is the issue of adolescents and reproductive health. Since parents now have access to their children’s records, some teenagers might hesitate to confide in their physicians and deny themselves important medical care.

The new rules permit blocking access to records if there is clear evidence that doing so “will substantially reduce the risk of harm” to patients or third parties. Psychotherapy counseling notes, for example, are completely exempt from the new requirements.

There are also state-level laws that can supersede the new federal law and block access to notes. For example, California law forbids providers from posting cancer test results without discussing them with the patient first.

Research indicates that shared notes have benefits that should outweigh the concerns of most physicians. One study showed that about 70% of patients said reviewing their notes helped them understand why medications were prescribed, which improved their compliance. This was particularly true for patients whose primary language is not English. A British study found that patients felt empowered by shared notes, and thought they improved their relationship with their physicians.

Other advantages of sharing notes include the ability of family members to review what happened at visits, which can be particularly important when dementia or other disabilities are involved. Patients will also be able to share their medical records with physicians outside of their health network, thus avoiding unnecessary or repetitious workups.

OpenNotes contends that when patients review their doctors’ notes, they gain “a newfound, deeper respect for what physicians have to understand to do their jobs.” Other predicted advantages include improved medical record accuracy and less miscommunication. In a study published in 2019 that evaluated experiences of patients who read ambulatory visit notes, only 5% were more worried after reading the notes and 3% were confused.

Alleviating worry among clinicians may be a bigger problem; but as a general principle, you should avoid judgmental language, and never write anything in a chart that you wouldn’t want your patients or their family members – or lawyers – to see.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

. While some clinicians consider it an unwelcome intrusion, advocates say it will improve communication and compliance.

Patient access to notes is not new. In many states, patients already have the ability to request copies of their charts, or to access truncated information via clinic websites. The difference is that most patients will now be able to click on a patient portal – such as MyChart, or other similar apps – and gain instantaneous, unfettered access to everything in their records.

Clinicians have traditionally thought of medical notes as private journal entries; but in the last few decades they have become an important component of the documentation necessary for billing, as well as evidence in the event of litigation. Now, with the implementation of the Cures Act, medical notes have evolved into a tool to communicate with the patient, rather than just among health care providers, lawyers, and billing departments.

Supporters contend that this change will make a big difference, because patients will be able to see exactly what their doctors have written, rather than just a list of confusing test results and diagnosis lists in “medicalese.”

OpenNotes, a think tank that has promoted the sharing of clinical notes with patients for years, calls the Cures Act legislation a “new world” where shared notes are valuable tools to improve communication between patients and physicians while strengthening their relationship. They cite evidence indicating that “when health professionals offer patients and families ready access to clinical notes, the quality and safety of care improves.”

Not all doctors are as enthusiastic. Many are concerned that patients might misinterpret what they see in their doctors’ notes, including complex descriptions of clinical assessments and decisions.

Others worry about patients having immediate access to their records, perhaps even before their physicians. The American Academy of Dermatology is working with the American Medical Association and other groups to gather real-world instances where the release of lab results, reports, or notes directly to patients before their physician could review the information with them caused emotional harm or other adverse consequences.

Undoubtedly, there are scenarios where unrestricted display of clinical notes could be problematic. One example is the issue of adolescents and reproductive health. Since parents now have access to their children’s records, some teenagers might hesitate to confide in their physicians and deny themselves important medical care.

The new rules permit blocking access to records if there is clear evidence that doing so “will substantially reduce the risk of harm” to patients or third parties. Psychotherapy counseling notes, for example, are completely exempt from the new requirements.

There are also state-level laws that can supersede the new federal law and block access to notes. For example, California law forbids providers from posting cancer test results without discussing them with the patient first.

Research indicates that shared notes have benefits that should outweigh the concerns of most physicians. One study showed that about 70% of patients said reviewing their notes helped them understand why medications were prescribed, which improved their compliance. This was particularly true for patients whose primary language is not English. A British study found that patients felt empowered by shared notes, and thought they improved their relationship with their physicians.

Other advantages of sharing notes include the ability of family members to review what happened at visits, which can be particularly important when dementia or other disabilities are involved. Patients will also be able to share their medical records with physicians outside of their health network, thus avoiding unnecessary or repetitious workups.

OpenNotes contends that when patients review their doctors’ notes, they gain “a newfound, deeper respect for what physicians have to understand to do their jobs.” Other predicted advantages include improved medical record accuracy and less miscommunication. In a study published in 2019 that evaluated experiences of patients who read ambulatory visit notes, only 5% were more worried after reading the notes and 3% were confused.

Alleviating worry among clinicians may be a bigger problem; but as a general principle, you should avoid judgmental language, and never write anything in a chart that you wouldn’t want your patients or their family members – or lawyers – to see.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

. While some clinicians consider it an unwelcome intrusion, advocates say it will improve communication and compliance.

Patient access to notes is not new. In many states, patients already have the ability to request copies of their charts, or to access truncated information via clinic websites. The difference is that most patients will now be able to click on a patient portal – such as MyChart, or other similar apps – and gain instantaneous, unfettered access to everything in their records.

Clinicians have traditionally thought of medical notes as private journal entries; but in the last few decades they have become an important component of the documentation necessary for billing, as well as evidence in the event of litigation. Now, with the implementation of the Cures Act, medical notes have evolved into a tool to communicate with the patient, rather than just among health care providers, lawyers, and billing departments.

Supporters contend that this change will make a big difference, because patients will be able to see exactly what their doctors have written, rather than just a list of confusing test results and diagnosis lists in “medicalese.”

OpenNotes, a think tank that has promoted the sharing of clinical notes with patients for years, calls the Cures Act legislation a “new world” where shared notes are valuable tools to improve communication between patients and physicians while strengthening their relationship. They cite evidence indicating that “when health professionals offer patients and families ready access to clinical notes, the quality and safety of care improves.”

Not all doctors are as enthusiastic. Many are concerned that patients might misinterpret what they see in their doctors’ notes, including complex descriptions of clinical assessments and decisions.

Others worry about patients having immediate access to their records, perhaps even before their physicians. The American Academy of Dermatology is working with the American Medical Association and other groups to gather real-world instances where the release of lab results, reports, or notes directly to patients before their physician could review the information with them caused emotional harm or other adverse consequences.

Undoubtedly, there are scenarios where unrestricted display of clinical notes could be problematic. One example is the issue of adolescents and reproductive health. Since parents now have access to their children’s records, some teenagers might hesitate to confide in their physicians and deny themselves important medical care.

The new rules permit blocking access to records if there is clear evidence that doing so “will substantially reduce the risk of harm” to patients or third parties. Psychotherapy counseling notes, for example, are completely exempt from the new requirements.

There are also state-level laws that can supersede the new federal law and block access to notes. For example, California law forbids providers from posting cancer test results without discussing them with the patient first.

Research indicates that shared notes have benefits that should outweigh the concerns of most physicians. One study showed that about 70% of patients said reviewing their notes helped them understand why medications were prescribed, which improved their compliance. This was particularly true for patients whose primary language is not English. A British study found that patients felt empowered by shared notes, and thought they improved their relationship with their physicians.

Other advantages of sharing notes include the ability of family members to review what happened at visits, which can be particularly important when dementia or other disabilities are involved. Patients will also be able to share their medical records with physicians outside of their health network, thus avoiding unnecessary or repetitious workups.

OpenNotes contends that when patients review their doctors’ notes, they gain “a newfound, deeper respect for what physicians have to understand to do their jobs.” Other predicted advantages include improved medical record accuracy and less miscommunication. In a study published in 2019 that evaluated experiences of patients who read ambulatory visit notes, only 5% were more worried after reading the notes and 3% were confused.

Alleviating worry among clinicians may be a bigger problem; but as a general principle, you should avoid judgmental language, and never write anything in a chart that you wouldn’t want your patients or their family members – or lawyers – to see.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Say my name

Dr. Ben-a-bo?

Nope.

Ben-nabi?

Nope.

Ben-NO-bo?

Also no.

My surname is tricky to pronounce for some people. I sometimes exaggerate to help patients get it right: “Beh-NAAH-bee-oh.” Almost daily someone will reply: “Oh, you’re Italian!” Well, no actually, my friend Enzo who was born in Sicily and lives in Milan, he’s Italian. I’m just a Rhode Islander who knows some Italian words from his grandmother. Most times though, I just answer: ‘Yep, I’m Italian.” It’s faster.

We use names as a shortcut to identify people. In clinic, it can help to find things in common quickly, similar to asking where you’re from. (East Coast patients seem to love that I’m from New England and if they’re Italian and from New York, well then, we’re paisans right from the start.)

However, using names to guess how someone identifies can be risky. In some instances, it could even be seen as microaggressive, particularly if you got it wrong.

Like most of you I’ll bet, I’m pretty good at pronouncing names – we practice thousands of times! Other than accepting a compliment for getting a tricky one right, such as Radivojevic (I think it’s Ra-di-VOI-ye-vich), I hadn’t thought much about names until I heard a great podcast on the topic. I thought I’d share a couple tips.

First, if you’re not particularly good at names or if you struggle with certain types of names, it’s better to ask than to butcher it. Like learning the wrong way to hit a golf ball, you may never be able to do it properly once you’ve done it wrong. (Trust me, I know from both.)

If I’m feeling confident, I’ll give it a try. But if unsure, I ask the patient to pronounce it for me, then I repeat it to confirm I’ve gotten it correct. Then I say it once or twice more during the visit. Lastly, for the knotty tongue-twisting ones, I write it phonetically in their chart.

It is important because mispronouncing names can alienate patients. It might make them feel like we don’t “know” them or that we don’t care about them. and eliminating ethnic disparities in care. Just think how much harder it might be to convince skeptical patients to take their lisinopril if you can’t even get their names right.

Worse perhaps than getting the pronunciation wrong is to turn the name into an issue. Saying: “Oh, that’s hard to pronounce” could be felt as a subtly racist remark – it’s not hard for them to pronounce of course, only for you. Also, guessing a patient’s nationality from the name is risky. Asking “are you Russian?” to someone from Ukraine or “is that Chinese?” to someone from Vietnam can quickly turn a nice office visit down a road named “Awkward.” It can give the impression that they “all look the same” to you, exactly the type of exclusion we’re trying to eliminate in medicine.

Saying a patient’s name perfectly is rewarding and a super-efficient way to connect. It can make salient the truth that you care about the patient and about his or her story, even if the name happens to be Mrs. Xiomara Winyuwongse Khosrowshahi Sundararajan Ngoc. Go ahead, give it a try.

Want more on how properly pronounce names correctly? You might like this episode of NPR’s Life Kit.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Dr. Ben-a-bo?

Nope.

Ben-nabi?

Nope.

Ben-NO-bo?

Also no.

My surname is tricky to pronounce for some people. I sometimes exaggerate to help patients get it right: “Beh-NAAH-bee-oh.” Almost daily someone will reply: “Oh, you’re Italian!” Well, no actually, my friend Enzo who was born in Sicily and lives in Milan, he’s Italian. I’m just a Rhode Islander who knows some Italian words from his grandmother. Most times though, I just answer: ‘Yep, I’m Italian.” It’s faster.

We use names as a shortcut to identify people. In clinic, it can help to find things in common quickly, similar to asking where you’re from. (East Coast patients seem to love that I’m from New England and if they’re Italian and from New York, well then, we’re paisans right from the start.)

However, using names to guess how someone identifies can be risky. In some instances, it could even be seen as microaggressive, particularly if you got it wrong.

Like most of you I’ll bet, I’m pretty good at pronouncing names – we practice thousands of times! Other than accepting a compliment for getting a tricky one right, such as Radivojevic (I think it’s Ra-di-VOI-ye-vich), I hadn’t thought much about names until I heard a great podcast on the topic. I thought I’d share a couple tips.

First, if you’re not particularly good at names or if you struggle with certain types of names, it’s better to ask than to butcher it. Like learning the wrong way to hit a golf ball, you may never be able to do it properly once you’ve done it wrong. (Trust me, I know from both.)

If I’m feeling confident, I’ll give it a try. But if unsure, I ask the patient to pronounce it for me, then I repeat it to confirm I’ve gotten it correct. Then I say it once or twice more during the visit. Lastly, for the knotty tongue-twisting ones, I write it phonetically in their chart.

It is important because mispronouncing names can alienate patients. It might make them feel like we don’t “know” them or that we don’t care about them. and eliminating ethnic disparities in care. Just think how much harder it might be to convince skeptical patients to take their lisinopril if you can’t even get their names right.

Worse perhaps than getting the pronunciation wrong is to turn the name into an issue. Saying: “Oh, that’s hard to pronounce” could be felt as a subtly racist remark – it’s not hard for them to pronounce of course, only for you. Also, guessing a patient’s nationality from the name is risky. Asking “are you Russian?” to someone from Ukraine or “is that Chinese?” to someone from Vietnam can quickly turn a nice office visit down a road named “Awkward.” It can give the impression that they “all look the same” to you, exactly the type of exclusion we’re trying to eliminate in medicine.

Saying a patient’s name perfectly is rewarding and a super-efficient way to connect. It can make salient the truth that you care about the patient and about his or her story, even if the name happens to be Mrs. Xiomara Winyuwongse Khosrowshahi Sundararajan Ngoc. Go ahead, give it a try.

Want more on how properly pronounce names correctly? You might like this episode of NPR’s Life Kit.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Dr. Ben-a-bo?

Nope.

Ben-nabi?

Nope.

Ben-NO-bo?

Also no.

My surname is tricky to pronounce for some people. I sometimes exaggerate to help patients get it right: “Beh-NAAH-bee-oh.” Almost daily someone will reply: “Oh, you’re Italian!” Well, no actually, my friend Enzo who was born in Sicily and lives in Milan, he’s Italian. I’m just a Rhode Islander who knows some Italian words from his grandmother. Most times though, I just answer: ‘Yep, I’m Italian.” It’s faster.

We use names as a shortcut to identify people. In clinic, it can help to find things in common quickly, similar to asking where you’re from. (East Coast patients seem to love that I’m from New England and if they’re Italian and from New York, well then, we’re paisans right from the start.)

However, using names to guess how someone identifies can be risky. In some instances, it could even be seen as microaggressive, particularly if you got it wrong.

Like most of you I’ll bet, I’m pretty good at pronouncing names – we practice thousands of times! Other than accepting a compliment for getting a tricky one right, such as Radivojevic (I think it’s Ra-di-VOI-ye-vich), I hadn’t thought much about names until I heard a great podcast on the topic. I thought I’d share a couple tips.

First, if you’re not particularly good at names or if you struggle with certain types of names, it’s better to ask than to butcher it. Like learning the wrong way to hit a golf ball, you may never be able to do it properly once you’ve done it wrong. (Trust me, I know from both.)

If I’m feeling confident, I’ll give it a try. But if unsure, I ask the patient to pronounce it for me, then I repeat it to confirm I’ve gotten it correct. Then I say it once or twice more during the visit. Lastly, for the knotty tongue-twisting ones, I write it phonetically in their chart.

It is important because mispronouncing names can alienate patients. It might make them feel like we don’t “know” them or that we don’t care about them. and eliminating ethnic disparities in care. Just think how much harder it might be to convince skeptical patients to take their lisinopril if you can’t even get their names right.

Worse perhaps than getting the pronunciation wrong is to turn the name into an issue. Saying: “Oh, that’s hard to pronounce” could be felt as a subtly racist remark – it’s not hard for them to pronounce of course, only for you. Also, guessing a patient’s nationality from the name is risky. Asking “are you Russian?” to someone from Ukraine or “is that Chinese?” to someone from Vietnam can quickly turn a nice office visit down a road named “Awkward.” It can give the impression that they “all look the same” to you, exactly the type of exclusion we’re trying to eliminate in medicine.

Saying a patient’s name perfectly is rewarding and a super-efficient way to connect. It can make salient the truth that you care about the patient and about his or her story, even if the name happens to be Mrs. Xiomara Winyuwongse Khosrowshahi Sundararajan Ngoc. Go ahead, give it a try.

Want more on how properly pronounce names correctly? You might like this episode of NPR’s Life Kit.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

A 12-year-old male has persistent purple toes and new red lesions on his hands

A punch biopsy from one of the lesions on the feet showed subtle basal vacuolar interface inflammation on the epidermis and rare apoptotic keratinocytes. There was an underlying dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate around the vascular plexus. Dermal mucin appeared slightly increased. The histologic findings are consistent with pernio. He had a negative direct immunofluorescence study.

Laboratory work-up showed an elevated antinuclear antibody (ANA) of 1:620; positive anticardiolipin IgM was at 15.2. A complete blood count showed no anemia or lymphopenia, he had normal complement C3 and C4 levels, normal urinalysis, negative cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins, and a normal protein electrophoresis.

Given the chronicity of his lesions, the lack of improvement with weather changes, the histopathologic findings of a vacuolar interface dermatitis and the positive ANA titer he was diagnosed with chilblain lupus.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus (CLE) is an uncommon form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus that presents with tender pink to violaceous macules, papules, and/or nodules that sometimes can ulcerate and are present on the fingers, toes, and sometimes the nose and ears. The lesions are usually triggered by cold exposure.1 These patients also have clinical and laboratory findings consistent with lupus erythematosus.

Even though more studies are needed to clarify the clinical and histopathologic features of chilblain lupus, compared with idiopathic pernio, some authors suggest several characteristics: CLE lesions tend to persist in summer months, as occurred in our patient, and histopathologic evaluation usually shows vacuolar and interface inflammation on the basal cell layer and may also have a positive lupus band on direct immunofluorescence.2 About 20% of patient with CLE may later develop systemic lupus erythematosus.3

There is also a familial form of CLE which is usually inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait. Mutations in TREX1, SAMHD1, and STING have been described in these patients.4 Affected children present with skin lesions at a young age and those with TREX1 mutations are at a higher risk to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of chilblain lupus includes idiopathic pernio or pernio secondary to other conditions. Other conditions that are thought to be associated with pernio, besides lupus erythematosus, include infectious causes (hepatitis B, COVID-19 infection),5 autoimmune conditions, malignancy and hematologic disorders (paraproteinemia).6 In histopathology, pernio lesions present with dermal edema and superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate.

The pathogenesis of pernio is not fully understood but is thought be related to vasospasm with secondary poor perfusion and ischemia and type I interferon (INF1) immune response. A recent review of the published studies trying to explain the causality between COVID 19 and pernio-like lesions, from January 2020 to December 2020, speculate several possible mechanisms: an increase in the vasoconstrictive, prothrombotic, and proinflammatory effects of the angiotensin II pathway through activation of the ACE2 by the virus; COVID-19 triggers a robust INF1 immune response in predisposed patients; pernio as a sign of mild disease, may be explained by genetic and hormonal differences in the patients affected.7

Another condition that can be confused with CLE is Raynaud phenomenon, were patients present with white to purple to red patches on the fingers and toes after exposure to cold, but in comparison with pernio, the lesions improve within minutes to hours after rewarming. Secondary Raynaud phenomenon can be seen in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and in patients with other connective tissue disorders. The skin lesions in our patient were persistent and were not triggered by cold exposure, making Raynaud phenomenon less likely. Children with vasculitis can present with painful red, violaceous, or necrotic lesions on the extremities, which can mimic pernio. Vasculitis lesions tend to be more purpuric and angulated, compared with pernio lesions, though in severe cases of pernio with ulceration it may be difficult to distinguish between the two entities and a skin biopsy may be needed.

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which children present with edematous tender nodules on the hands and with less frequency in other parts of the body with associated fever, malaise, conjunctivitis, or joint pain and it is usually associated with infection or malignancy. Our patient denied any systemic symptoms and had no conjunctivitis nor arthritis.

Most patients with idiopathic pernio do not require a biopsy or further laboratory evaluation unless the lesions are atypical, chronic, or there is a suspected associated condition. The workup for patients with prolonged or atypical pernio-like lesions include a skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence, ANA, complete blood count, complement levels, antiphospholipid antibodies, cold agglutinins, and cryoglobulins.

Treatment of mild CLE is with moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. In those patients not responding to topical measures and keeping the extremities warm, the use of hydroxychloroquine has been reported to be beneficial in some patients as well as the use of calcium-channel blockers.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Su WP et al. Cutis. 1994 Dec;54(6):395-9.

2. Boada A et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010 Feb;32(1):19-23.

3. Patel et al. SBMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201165.

4. Genes Yi et al. BMC. 2020 Apr 15;18(1):32.

5. Battesti G et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1219-22.

6. Cappel JA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

7. Cappel MA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(4):989-1005.

A punch biopsy from one of the lesions on the feet showed subtle basal vacuolar interface inflammation on the epidermis and rare apoptotic keratinocytes. There was an underlying dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate around the vascular plexus. Dermal mucin appeared slightly increased. The histologic findings are consistent with pernio. He had a negative direct immunofluorescence study.

Laboratory work-up showed an elevated antinuclear antibody (ANA) of 1:620; positive anticardiolipin IgM was at 15.2. A complete blood count showed no anemia or lymphopenia, he had normal complement C3 and C4 levels, normal urinalysis, negative cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins, and a normal protein electrophoresis.

Given the chronicity of his lesions, the lack of improvement with weather changes, the histopathologic findings of a vacuolar interface dermatitis and the positive ANA titer he was diagnosed with chilblain lupus.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus (CLE) is an uncommon form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus that presents with tender pink to violaceous macules, papules, and/or nodules that sometimes can ulcerate and are present on the fingers, toes, and sometimes the nose and ears. The lesions are usually triggered by cold exposure.1 These patients also have clinical and laboratory findings consistent with lupus erythematosus.

Even though more studies are needed to clarify the clinical and histopathologic features of chilblain lupus, compared with idiopathic pernio, some authors suggest several characteristics: CLE lesions tend to persist in summer months, as occurred in our patient, and histopathologic evaluation usually shows vacuolar and interface inflammation on the basal cell layer and may also have a positive lupus band on direct immunofluorescence.2 About 20% of patient with CLE may later develop systemic lupus erythematosus.3

There is also a familial form of CLE which is usually inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait. Mutations in TREX1, SAMHD1, and STING have been described in these patients.4 Affected children present with skin lesions at a young age and those with TREX1 mutations are at a higher risk to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of chilblain lupus includes idiopathic pernio or pernio secondary to other conditions. Other conditions that are thought to be associated with pernio, besides lupus erythematosus, include infectious causes (hepatitis B, COVID-19 infection),5 autoimmune conditions, malignancy and hematologic disorders (paraproteinemia).6 In histopathology, pernio lesions present with dermal edema and superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate.

The pathogenesis of pernio is not fully understood but is thought be related to vasospasm with secondary poor perfusion and ischemia and type I interferon (INF1) immune response. A recent review of the published studies trying to explain the causality between COVID 19 and pernio-like lesions, from January 2020 to December 2020, speculate several possible mechanisms: an increase in the vasoconstrictive, prothrombotic, and proinflammatory effects of the angiotensin II pathway through activation of the ACE2 by the virus; COVID-19 triggers a robust INF1 immune response in predisposed patients; pernio as a sign of mild disease, may be explained by genetic and hormonal differences in the patients affected.7

Another condition that can be confused with CLE is Raynaud phenomenon, were patients present with white to purple to red patches on the fingers and toes after exposure to cold, but in comparison with pernio, the lesions improve within minutes to hours after rewarming. Secondary Raynaud phenomenon can be seen in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and in patients with other connective tissue disorders. The skin lesions in our patient were persistent and were not triggered by cold exposure, making Raynaud phenomenon less likely. Children with vasculitis can present with painful red, violaceous, or necrotic lesions on the extremities, which can mimic pernio. Vasculitis lesions tend to be more purpuric and angulated, compared with pernio lesions, though in severe cases of pernio with ulceration it may be difficult to distinguish between the two entities and a skin biopsy may be needed.

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which children present with edematous tender nodules on the hands and with less frequency in other parts of the body with associated fever, malaise, conjunctivitis, or joint pain and it is usually associated with infection or malignancy. Our patient denied any systemic symptoms and had no conjunctivitis nor arthritis.

Most patients with idiopathic pernio do not require a biopsy or further laboratory evaluation unless the lesions are atypical, chronic, or there is a suspected associated condition. The workup for patients with prolonged or atypical pernio-like lesions include a skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence, ANA, complete blood count, complement levels, antiphospholipid antibodies, cold agglutinins, and cryoglobulins.

Treatment of mild CLE is with moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. In those patients not responding to topical measures and keeping the extremities warm, the use of hydroxychloroquine has been reported to be beneficial in some patients as well as the use of calcium-channel blockers.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Su WP et al. Cutis. 1994 Dec;54(6):395-9.

2. Boada A et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010 Feb;32(1):19-23.

3. Patel et al. SBMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201165.

4. Genes Yi et al. BMC. 2020 Apr 15;18(1):32.

5. Battesti G et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1219-22.

6. Cappel JA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

7. Cappel MA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(4):989-1005.

A punch biopsy from one of the lesions on the feet showed subtle basal vacuolar interface inflammation on the epidermis and rare apoptotic keratinocytes. There was an underlying dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate around the vascular plexus. Dermal mucin appeared slightly increased. The histologic findings are consistent with pernio. He had a negative direct immunofluorescence study.

Laboratory work-up showed an elevated antinuclear antibody (ANA) of 1:620; positive anticardiolipin IgM was at 15.2. A complete blood count showed no anemia or lymphopenia, he had normal complement C3 and C4 levels, normal urinalysis, negative cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins, and a normal protein electrophoresis.

Given the chronicity of his lesions, the lack of improvement with weather changes, the histopathologic findings of a vacuolar interface dermatitis and the positive ANA titer he was diagnosed with chilblain lupus.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus (CLE) is an uncommon form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus that presents with tender pink to violaceous macules, papules, and/or nodules that sometimes can ulcerate and are present on the fingers, toes, and sometimes the nose and ears. The lesions are usually triggered by cold exposure.1 These patients also have clinical and laboratory findings consistent with lupus erythematosus.

Even though more studies are needed to clarify the clinical and histopathologic features of chilblain lupus, compared with idiopathic pernio, some authors suggest several characteristics: CLE lesions tend to persist in summer months, as occurred in our patient, and histopathologic evaluation usually shows vacuolar and interface inflammation on the basal cell layer and may also have a positive lupus band on direct immunofluorescence.2 About 20% of patient with CLE may later develop systemic lupus erythematosus.3

There is also a familial form of CLE which is usually inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait. Mutations in TREX1, SAMHD1, and STING have been described in these patients.4 Affected children present with skin lesions at a young age and those with TREX1 mutations are at a higher risk to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of chilblain lupus includes idiopathic pernio or pernio secondary to other conditions. Other conditions that are thought to be associated with pernio, besides lupus erythematosus, include infectious causes (hepatitis B, COVID-19 infection),5 autoimmune conditions, malignancy and hematologic disorders (paraproteinemia).6 In histopathology, pernio lesions present with dermal edema and superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate.

The pathogenesis of pernio is not fully understood but is thought be related to vasospasm with secondary poor perfusion and ischemia and type I interferon (INF1) immune response. A recent review of the published studies trying to explain the causality between COVID 19 and pernio-like lesions, from January 2020 to December 2020, speculate several possible mechanisms: an increase in the vasoconstrictive, prothrombotic, and proinflammatory effects of the angiotensin II pathway through activation of the ACE2 by the virus; COVID-19 triggers a robust INF1 immune response in predisposed patients; pernio as a sign of mild disease, may be explained by genetic and hormonal differences in the patients affected.7

Another condition that can be confused with CLE is Raynaud phenomenon, were patients present with white to purple to red patches on the fingers and toes after exposure to cold, but in comparison with pernio, the lesions improve within minutes to hours after rewarming. Secondary Raynaud phenomenon can be seen in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and in patients with other connective tissue disorders. The skin lesions in our patient were persistent and were not triggered by cold exposure, making Raynaud phenomenon less likely. Children with vasculitis can present with painful red, violaceous, or necrotic lesions on the extremities, which can mimic pernio. Vasculitis lesions tend to be more purpuric and angulated, compared with pernio lesions, though in severe cases of pernio with ulceration it may be difficult to distinguish between the two entities and a skin biopsy may be needed.

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which children present with edematous tender nodules on the hands and with less frequency in other parts of the body with associated fever, malaise, conjunctivitis, or joint pain and it is usually associated with infection or malignancy. Our patient denied any systemic symptoms and had no conjunctivitis nor arthritis.

Most patients with idiopathic pernio do not require a biopsy or further laboratory evaluation unless the lesions are atypical, chronic, or there is a suspected associated condition. The workup for patients with prolonged or atypical pernio-like lesions include a skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence, ANA, complete blood count, complement levels, antiphospholipid antibodies, cold agglutinins, and cryoglobulins.

Treatment of mild CLE is with moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. In those patients not responding to topical measures and keeping the extremities warm, the use of hydroxychloroquine has been reported to be beneficial in some patients as well as the use of calcium-channel blockers.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Su WP et al. Cutis. 1994 Dec;54(6):395-9.

2. Boada A et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010 Feb;32(1):19-23.

3. Patel et al. SBMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201165.

4. Genes Yi et al. BMC. 2020 Apr 15;18(1):32.

5. Battesti G et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1219-22.

6. Cappel JA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

7. Cappel MA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(4):989-1005.

He denied any hair loss, mouth sores, sun sensitivity, headaches, gastrointestinal complaints, joint pain, or muscle weakness.

He is not taking any medications.

He has been at home doing virtual school and has not traveled. He likes to play the piano. There is no family history of similar lesions, connective tissue disorder, or autoimmunity.

On physical exam he has purple discoloration on the toes with some violaceous and pink papules. On the fingers he has pink to violaceous papules and macules.

There is no joint edema or pain.

Navigating challenges in COVID-19 care

Early strategies for adapting to a moving target

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital groups and systems scrambled to create protocols and models to respond to the novel coronavirus. In the pre-pandemic world, hospital groups have traditionally focused on standardizing clinical protocols and care models that rely on evidence-based medical practices or extended experience.

During COVID-19, however, our team at Dell Medical School needed to rapidly and iteratively standardize care based on evolving science, effectively communicate that approach across rotating hospital medicine physicians and residents, and update care models, workflows, and technology every few days. In this article, we review our initial experiences, describe the strategies we employed to respond to these challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned and our proposed strategy moving forward.

Early pandemic challenges

Our initial inpatient strategies focused on containment, infection prevention, and bracing ourselves rather than creating a COVID Center of Excellence (COE). In fact, our hospital network’s initial strategy was to have COVID-19 patients transferred to a different hospital within our network. However, as March progressed, we became the designated COVID-19 hospital in our area’s network because of the increasing volume of patients we saw.

Patients from the surrounding regional hospitals were transferring their COVID-19 patients to us and we quickly saw the wide spectrum of illness, ranging from mild pneumonia to severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation upon admission. All frontline providers felt the stress of needing to find treatment options quickly for our sickest patients. We realized that to provide safe, effective, and high-quality care to COVID-19 patients, we needed to create a sustainable and standardized interdisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 testing was a major challenge when the pandemic hit as testing kits and personal protective equipment were in limited supply. How would we choose who to test or empirically place in COVID-19 isolation? In addition, we faced questions surrounding safe discharge practices, especially for patients who could not self-isolate in their home (if they even had one).

In March, emergency use authorization (EUA) for hydroxychloroquine was granted by the U.S. FDA despite limited data. This resulted in pressure from the public to use this drug in our patients. At the same time, we saw that some patients quickly got better on their own with supportive care. As clinicians striving to practice evidence-based medicine, we certainly did not want to give patients an unproven therapy that could do more harm than good. We also felt the need to respond with statements about what we could do that worked – rather than negotiate about withholding certain treatments featured in the news. Clearly, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to therapeutics was not going to work in treating patients with COVID-19.

We realized we were going to have to learn and adapt together – quickly. It became apparent that we needed to create structures to rapidly adjudicate and integrate emerging science into standardized clinical care delivery.

Solutions in the form of better structures

In response to these challenges, we created early morning meetings or “huddles” among COVID-19 care teams and hospital administration. A designated “COVID ID” physician from Infectious Diseases would meet with hospitalist and critical care teams each morning in our daily huddles to review all newly admitted patients, current hospitalized patients, and patients with pending COVID-19 tests or suspected initial false-negative tests.

Together, and via the newly developed Therapeutics and Informatics Committee, we created early treatment recommendations based upon available evidence, treatment availability, and the patient’s severity of illness. Within the first ten days of admitting our first patient, it had become standard practice to review eligible patients soon after admission for therapies such as convalescent plasma, and, later, remdesivir and steroids.

We codified these consensus recommendations and processes in our Dell Med COVID Manual, a living document that was frequently updated and disseminated to our group. It created a single ‘true north’ of standardized workflows for triage, diagnosis, management, discharge coordination, and end-of-life care. The document allowed for continuous and asynchronous multi-person collaboration and extremely rapid cycles of improvement. Between March and December 2020, this 100-page handbook went through more than 130 iterations.

Strategy for the future

This approach – communicating frequently, adapting on a daily to weekly basis, and continuously scanning the science for opportunities to improve our care delivery – became the foundation of our approach and the Therapeutics and Informatics Committee. Just as importantly, this created a culture of engagement, collaboration, and shared problem-solving that helped us stay organized, keep up to date with the latest science, and innovate rather than panic when faced with ongoing unpredictability and chaos in the early days of the pandemic.

As the pandemic enters into its 13th month, we carry this foundation and our strategies forward. The infrastructure and systems of communication that we have set in place will allow us to be nimble in our response as COVID-19 numbers surge in our region.

Dr. Gandhi is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Mondy is chief of the division of infectious disease and associate professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Busch and Dr. Brode are assistant professors in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Early strategies for adapting to a moving target

Early strategies for adapting to a moving target

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital groups and systems scrambled to create protocols and models to respond to the novel coronavirus. In the pre-pandemic world, hospital groups have traditionally focused on standardizing clinical protocols and care models that rely on evidence-based medical practices or extended experience.

During COVID-19, however, our team at Dell Medical School needed to rapidly and iteratively standardize care based on evolving science, effectively communicate that approach across rotating hospital medicine physicians and residents, and update care models, workflows, and technology every few days. In this article, we review our initial experiences, describe the strategies we employed to respond to these challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned and our proposed strategy moving forward.

Early pandemic challenges

Our initial inpatient strategies focused on containment, infection prevention, and bracing ourselves rather than creating a COVID Center of Excellence (COE). In fact, our hospital network’s initial strategy was to have COVID-19 patients transferred to a different hospital within our network. However, as March progressed, we became the designated COVID-19 hospital in our area’s network because of the increasing volume of patients we saw.

Patients from the surrounding regional hospitals were transferring their COVID-19 patients to us and we quickly saw the wide spectrum of illness, ranging from mild pneumonia to severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation upon admission. All frontline providers felt the stress of needing to find treatment options quickly for our sickest patients. We realized that to provide safe, effective, and high-quality care to COVID-19 patients, we needed to create a sustainable and standardized interdisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 testing was a major challenge when the pandemic hit as testing kits and personal protective equipment were in limited supply. How would we choose who to test or empirically place in COVID-19 isolation? In addition, we faced questions surrounding safe discharge practices, especially for patients who could not self-isolate in their home (if they even had one).

In March, emergency use authorization (EUA) for hydroxychloroquine was granted by the U.S. FDA despite limited data. This resulted in pressure from the public to use this drug in our patients. At the same time, we saw that some patients quickly got better on their own with supportive care. As clinicians striving to practice evidence-based medicine, we certainly did not want to give patients an unproven therapy that could do more harm than good. We also felt the need to respond with statements about what we could do that worked – rather than negotiate about withholding certain treatments featured in the news. Clearly, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to therapeutics was not going to work in treating patients with COVID-19.

We realized we were going to have to learn and adapt together – quickly. It became apparent that we needed to create structures to rapidly adjudicate and integrate emerging science into standardized clinical care delivery.

Solutions in the form of better structures

In response to these challenges, we created early morning meetings or “huddles” among COVID-19 care teams and hospital administration. A designated “COVID ID” physician from Infectious Diseases would meet with hospitalist and critical care teams each morning in our daily huddles to review all newly admitted patients, current hospitalized patients, and patients with pending COVID-19 tests or suspected initial false-negative tests.

Together, and via the newly developed Therapeutics and Informatics Committee, we created early treatment recommendations based upon available evidence, treatment availability, and the patient’s severity of illness. Within the first ten days of admitting our first patient, it had become standard practice to review eligible patients soon after admission for therapies such as convalescent plasma, and, later, remdesivir and steroids.

We codified these consensus recommendations and processes in our Dell Med COVID Manual, a living document that was frequently updated and disseminated to our group. It created a single ‘true north’ of standardized workflows for triage, diagnosis, management, discharge coordination, and end-of-life care. The document allowed for continuous and asynchronous multi-person collaboration and extremely rapid cycles of improvement. Between March and December 2020, this 100-page handbook went through more than 130 iterations.

Strategy for the future

This approach – communicating frequently, adapting on a daily to weekly basis, and continuously scanning the science for opportunities to improve our care delivery – became the foundation of our approach and the Therapeutics and Informatics Committee. Just as importantly, this created a culture of engagement, collaboration, and shared problem-solving that helped us stay organized, keep up to date with the latest science, and innovate rather than panic when faced with ongoing unpredictability and chaos in the early days of the pandemic.

As the pandemic enters into its 13th month, we carry this foundation and our strategies forward. The infrastructure and systems of communication that we have set in place will allow us to be nimble in our response as COVID-19 numbers surge in our region.

Dr. Gandhi is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Mondy is chief of the division of infectious disease and associate professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Busch and Dr. Brode are assistant professors in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital groups and systems scrambled to create protocols and models to respond to the novel coronavirus. In the pre-pandemic world, hospital groups have traditionally focused on standardizing clinical protocols and care models that rely on evidence-based medical practices or extended experience.

During COVID-19, however, our team at Dell Medical School needed to rapidly and iteratively standardize care based on evolving science, effectively communicate that approach across rotating hospital medicine physicians and residents, and update care models, workflows, and technology every few days. In this article, we review our initial experiences, describe the strategies we employed to respond to these challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned and our proposed strategy moving forward.

Early pandemic challenges

Our initial inpatient strategies focused on containment, infection prevention, and bracing ourselves rather than creating a COVID Center of Excellence (COE). In fact, our hospital network’s initial strategy was to have COVID-19 patients transferred to a different hospital within our network. However, as March progressed, we became the designated COVID-19 hospital in our area’s network because of the increasing volume of patients we saw.

Patients from the surrounding regional hospitals were transferring their COVID-19 patients to us and we quickly saw the wide spectrum of illness, ranging from mild pneumonia to severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation upon admission. All frontline providers felt the stress of needing to find treatment options quickly for our sickest patients. We realized that to provide safe, effective, and high-quality care to COVID-19 patients, we needed to create a sustainable and standardized interdisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 testing was a major challenge when the pandemic hit as testing kits and personal protective equipment were in limited supply. How would we choose who to test or empirically place in COVID-19 isolation? In addition, we faced questions surrounding safe discharge practices, especially for patients who could not self-isolate in their home (if they even had one).

In March, emergency use authorization (EUA) for hydroxychloroquine was granted by the U.S. FDA despite limited data. This resulted in pressure from the public to use this drug in our patients. At the same time, we saw that some patients quickly got better on their own with supportive care. As clinicians striving to practice evidence-based medicine, we certainly did not want to give patients an unproven therapy that could do more harm than good. We also felt the need to respond with statements about what we could do that worked – rather than negotiate about withholding certain treatments featured in the news. Clearly, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to therapeutics was not going to work in treating patients with COVID-19.

We realized we were going to have to learn and adapt together – quickly. It became apparent that we needed to create structures to rapidly adjudicate and integrate emerging science into standardized clinical care delivery.

Solutions in the form of better structures

In response to these challenges, we created early morning meetings or “huddles” among COVID-19 care teams and hospital administration. A designated “COVID ID” physician from Infectious Diseases would meet with hospitalist and critical care teams each morning in our daily huddles to review all newly admitted patients, current hospitalized patients, and patients with pending COVID-19 tests or suspected initial false-negative tests.

Together, and via the newly developed Therapeutics and Informatics Committee, we created early treatment recommendations based upon available evidence, treatment availability, and the patient’s severity of illness. Within the first ten days of admitting our first patient, it had become standard practice to review eligible patients soon after admission for therapies such as convalescent plasma, and, later, remdesivir and steroids.

We codified these consensus recommendations and processes in our Dell Med COVID Manual, a living document that was frequently updated and disseminated to our group. It created a single ‘true north’ of standardized workflows for triage, diagnosis, management, discharge coordination, and end-of-life care. The document allowed for continuous and asynchronous multi-person collaboration and extremely rapid cycles of improvement. Between March and December 2020, this 100-page handbook went through more than 130 iterations.

Strategy for the future

This approach – communicating frequently, adapting on a daily to weekly basis, and continuously scanning the science for opportunities to improve our care delivery – became the foundation of our approach and the Therapeutics and Informatics Committee. Just as importantly, this created a culture of engagement, collaboration, and shared problem-solving that helped us stay organized, keep up to date with the latest science, and innovate rather than panic when faced with ongoing unpredictability and chaos in the early days of the pandemic.

As the pandemic enters into its 13th month, we carry this foundation and our strategies forward. The infrastructure and systems of communication that we have set in place will allow us to be nimble in our response as COVID-19 numbers surge in our region.

Dr. Gandhi is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Mondy is chief of the division of infectious disease and associate professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Busch and Dr. Brode are assistant professors in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Goodbye, OTC hydroquinone

In 1972, an over-the-counter drug review process was established by the Food and Drug Administration to regulate the safety and efficacy of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. This created a book or “monograph” for each medication category that describes the active ingredients, indications, doses, route of administration, testing, and labeling. If a drug meets the criteria in its therapeutic category, it does not have to undergo an FDA review before being marketed to consumers.

As part of this process, drugs are classified into one of three categories: category I: generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) and not misbranded; category II: not GRASE; category III: lacking sufficient data on safety and efficacy to permit classification. This methodology was outdated and made it difficult under the old guidelines to make changes to medications in the evolving world of drug development. Some categories of OTC drugs, including hand sanitizers, hydroquinone, and sunscreens, have been marketed for years without a final monograph.

The signing of the “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act in March 2020 included reforms in the FDA monograph process for OTC medications. Under this proceeding, a final monograph determination was made for all OTC categories. While drugs in category I and some in category III may remain on the market, if certain specifications are met, category II drugs had to be removed within 180 days of the enactment of the CARES Act.

Hydroquinone was one of those that fell victim to the ban. This ban is similar to hydroquinone bans in other places, including Europe. However, for manufacturers, this issue was under the radar and packaged in a seemingly irrelevant piece of legislation.

Among dermatologists, there is no consensus as to whether 2% hydroquinone is safe or not. However, the unmonitored use and overuse that is common for this type of medication has led to heightened safety concerns. Common side effects of hydroquinone include irritant and allergic contact dermatitis; the most difficult to treat side effect with long-term use is ochronosis. But there are no reported cancer data in humans with the use of topical hydroquinone as previously thought. Hydroquinone used short term is a very safe and effective treatment for hard to treat hyperpigmentation and is often necessary when other topicals are ineffective, particularly in our patients with skin of color.

The bigger problem however is the legislative process involved, as exemplified by this ban, which only came to light because of the CARES act.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

In 1972, an over-the-counter drug review process was established by the Food and Drug Administration to regulate the safety and efficacy of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. This created a book or “monograph” for each medication category that describes the active ingredients, indications, doses, route of administration, testing, and labeling. If a drug meets the criteria in its therapeutic category, it does not have to undergo an FDA review before being marketed to consumers.

As part of this process, drugs are classified into one of three categories: category I: generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) and not misbranded; category II: not GRASE; category III: lacking sufficient data on safety and efficacy to permit classification. This methodology was outdated and made it difficult under the old guidelines to make changes to medications in the evolving world of drug development. Some categories of OTC drugs, including hand sanitizers, hydroquinone, and sunscreens, have been marketed for years without a final monograph.

The signing of the “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act in March 2020 included reforms in the FDA monograph process for OTC medications. Under this proceeding, a final monograph determination was made for all OTC categories. While drugs in category I and some in category III may remain on the market, if certain specifications are met, category II drugs had to be removed within 180 days of the enactment of the CARES Act.

Hydroquinone was one of those that fell victim to the ban. This ban is similar to hydroquinone bans in other places, including Europe. However, for manufacturers, this issue was under the radar and packaged in a seemingly irrelevant piece of legislation.

Among dermatologists, there is no consensus as to whether 2% hydroquinone is safe or not. However, the unmonitored use and overuse that is common for this type of medication has led to heightened safety concerns. Common side effects of hydroquinone include irritant and allergic contact dermatitis; the most difficult to treat side effect with long-term use is ochronosis. But there are no reported cancer data in humans with the use of topical hydroquinone as previously thought. Hydroquinone used short term is a very safe and effective treatment for hard to treat hyperpigmentation and is often necessary when other topicals are ineffective, particularly in our patients with skin of color.

The bigger problem however is the legislative process involved, as exemplified by this ban, which only came to light because of the CARES act.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

In 1972, an over-the-counter drug review process was established by the Food and Drug Administration to regulate the safety and efficacy of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. This created a book or “monograph” for each medication category that describes the active ingredients, indications, doses, route of administration, testing, and labeling. If a drug meets the criteria in its therapeutic category, it does not have to undergo an FDA review before being marketed to consumers.

As part of this process, drugs are classified into one of three categories: category I: generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) and not misbranded; category II: not GRASE; category III: lacking sufficient data on safety and efficacy to permit classification. This methodology was outdated and made it difficult under the old guidelines to make changes to medications in the evolving world of drug development. Some categories of OTC drugs, including hand sanitizers, hydroquinone, and sunscreens, have been marketed for years without a final monograph.

The signing of the “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act in March 2020 included reforms in the FDA monograph process for OTC medications. Under this proceeding, a final monograph determination was made for all OTC categories. While drugs in category I and some in category III may remain on the market, if certain specifications are met, category II drugs had to be removed within 180 days of the enactment of the CARES Act.

Hydroquinone was one of those that fell victim to the ban. This ban is similar to hydroquinone bans in other places, including Europe. However, for manufacturers, this issue was under the radar and packaged in a seemingly irrelevant piece of legislation.

Among dermatologists, there is no consensus as to whether 2% hydroquinone is safe or not. However, the unmonitored use and overuse that is common for this type of medication has led to heightened safety concerns. Common side effects of hydroquinone include irritant and allergic contact dermatitis; the most difficult to treat side effect with long-term use is ochronosis. But there are no reported cancer data in humans with the use of topical hydroquinone as previously thought. Hydroquinone used short term is a very safe and effective treatment for hard to treat hyperpigmentation and is often necessary when other topicals are ineffective, particularly in our patients with skin of color.

The bigger problem however is the legislative process involved, as exemplified by this ban, which only came to light because of the CARES act.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

Tick talk for families and pediatricians

Spring 2021 has arrived with summer quickly approaching. It is our second spring and summer during the pandemic. Travel restrictions have minimally eased for vaccinated adults. However, neither domestic nor international leisure travel is encouraged for anyone. Ironically, air travel is increasing. For many families, it is time to make decisions regarding summer activities. Outdoor activities have been encouraged throughout the pandemic, which makes it a good time to review tick-borne diseases. Depending on your location, your patients may only have to travel as far as their backyard to sustain a tick bite.

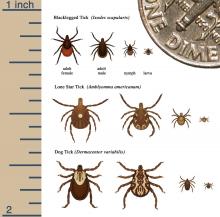

Ticks are a group of obligate, bloodsucking arthropods that feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles. There are three families of ticks. Two families, Ixodidae (hard-bodied ticks) and Argasidae (soft-bodied ticks) are responsible for transmitting the most diseases to humans in the United States. Once a tick is infected with a pathogen it usually survives and transmits it to its next host. Ticks efficiently transmit bacteria, spirochetes, protozoa, rickettsiae, nematodes, and toxins to humans during feeding when the site is exposed to infected salivary gland secretions or regurgitated midgut contents. Pathogen transmission can also occur when the feeding site is contaminated by feces or coxal fluid. Sometimes a tick can transmit multiple pathogens. Not all pathogens are infectious (e.g., tick paralysis, which occurs after exposure to a neurotoxin and red meat allergy because of alpha-gal). Ticks require a blood meal to transform to their next stage of development (larva to nymph to adult). Life cycles of hard and soft ticks differ with most hard ticks undergoing a 2-year life cycle and feeding slowly over many days. In contrast, soft ticks feed multiple times often for less than 1 hour and are capable of transmitting diseases in less than 1 minute.

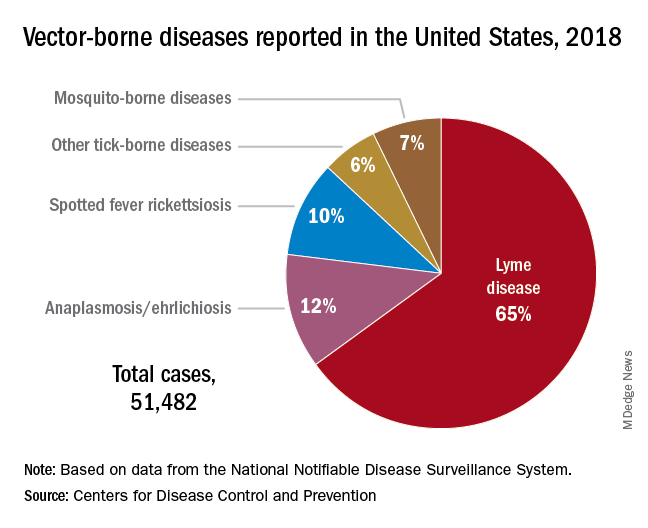

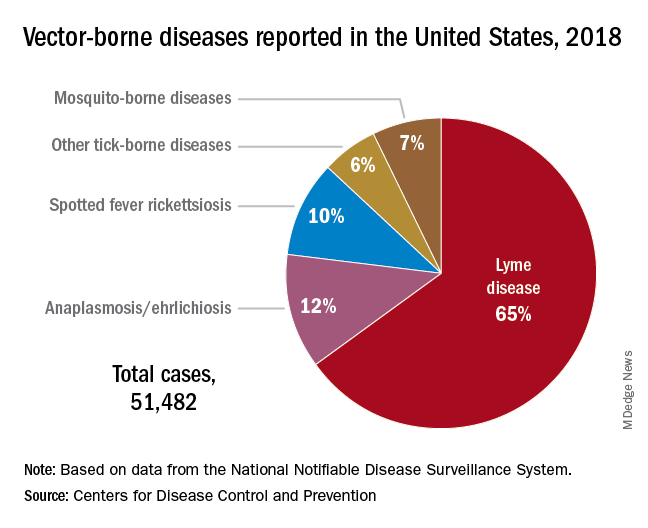

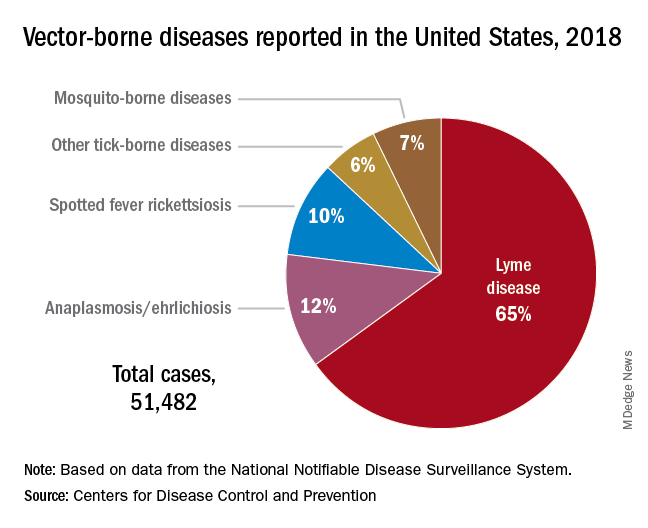

Rocky Mountain spotted fever was the first recognized tick-borne disease (TBD) in humans. Since then, 18 additional pathogens transmitted by ticks have been identified with 40% being described since 1980. The increased discovery of tickborne pathogens has been attributed to physician awareness of TBD and improved diagnostics. The number of cases of TBD has risen yearly. Ticks are responsible for most vector-transmitted diseases in the United States with Lyme disease most frequently reported.

Mosquito transmission accounts for only 7% of vector-borne diseases. Three species of ticks are responsible for most human disease: Ixodes scapularis (Black-legged tick), Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), and Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick). Each is capable of transmitting agents that cause multiple diseases.

Risk for acquisition of a specific disease is dependent upon the type of tick, its geographic location, the season, and duration of the exposure.

Humans are usually incidental hosts. Tick exposure can occur year-round, but tick activity is greatest between April and September. Ticks are generally found near the ground, in brushy or wooded areas. They can climb tall grasses or shrubs and wait for a potential host to brush against them. When this occurs, they seek a site for attachment.

In the absence of a vaccine, prevention of TBD is totally dependent upon your patients/parents understanding of when and where they are at risk for exposure and for us as physicians to know which pathogens can potentially be transmitted by ticks. Data regarding potential exposure risks are based on where a TBD was diagnosed, not necessarily where it was acquired. National maps that illustrate the distribution of medically significant ticks and presence or prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in specific areas within a region previously may have been incomplete or outdated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiated a national tick surveillance program in 2017; five universities were established as regional centers of excellence to help prevent and rapidly respond to emerging vector-borne diseases across the United States. One goal is to standardize tick surveillance activities at the state level. For state-specific activity go to https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/vital-signs/index.html.

Prevention: Here are a few environmental interventions you can recommend to your patients

- Remove leaf litter, clear tall brush, and grass around the home and at edge of lawns. Mow the lawn frequently.

- Keep playground equipment, decks, and patios away from yard edges and trees.

- Live near a wooded area? Place a 3-ft.-wide barrier of gravel or wood chips between the areas.

- Put up a fence to keep unwanted animals out.

- Keep the yard free of potential hiding place for ticks (e.g., mattresses or furniture).

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area.

- Use pesticides, but do not rely on them solely to prevent ticks exposure.

Personal interventions for patients when outdoors

- Use Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents. Note: Oil of lemon-, eucalyptus-, and para-menthane-diol–containing products should not be used in children aged3 years or less.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin to repel mosquitoes and ticks.

- Check cloths for ticks. Drying clothes on high heat for 10 minutes will kill ticks. If washing is needed use hot water. Lower temperatures will not kill ticks.

- Do daily body checks for ticks after coming indoors.

- Check pets for ticks.

Tick removal

- Take tweezers, grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward. Do not twist or jerk the tick. Place in a container. Ideally submit for species identification.

- After removal, clean the bite area with alcohol or soap and water.

- Never crush a tick with your fingers.

When should you include TBD in your differential for a sick child?

Headache, fever, arthralgia, and rash are symptoms for several infectious diseases. Obtaining a history of recent activities, tick bite, or travel to areas where these diseases are more prevalent is important. You must have a high index of suspicion. Clinical and laboratory clues may help.

Delay in treatment is more detrimental. If you suspect rickettsia, ehrlichiosis, or anaplasmosis, doxycycline should be started promptly regardless of age. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended.

The United States recognizes it is not adequately prepared to address the continuing rise of vector-borne diseases. In response, on Jan. 20, 2021, the CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases with input from five federal departments and the EPA developed a joint National Public Health Framework for the Prevention and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases in Humans to tackle issues including risk, detection, diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of TBD. Stay tuned.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Spring 2021 has arrived with summer quickly approaching. It is our second spring and summer during the pandemic. Travel restrictions have minimally eased for vaccinated adults. However, neither domestic nor international leisure travel is encouraged for anyone. Ironically, air travel is increasing. For many families, it is time to make decisions regarding summer activities. Outdoor activities have been encouraged throughout the pandemic, which makes it a good time to review tick-borne diseases. Depending on your location, your patients may only have to travel as far as their backyard to sustain a tick bite.

Ticks are a group of obligate, bloodsucking arthropods that feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles. There are three families of ticks. Two families, Ixodidae (hard-bodied ticks) and Argasidae (soft-bodied ticks) are responsible for transmitting the most diseases to humans in the United States. Once a tick is infected with a pathogen it usually survives and transmits it to its next host. Ticks efficiently transmit bacteria, spirochetes, protozoa, rickettsiae, nematodes, and toxins to humans during feeding when the site is exposed to infected salivary gland secretions or regurgitated midgut contents. Pathogen transmission can also occur when the feeding site is contaminated by feces or coxal fluid. Sometimes a tick can transmit multiple pathogens. Not all pathogens are infectious (e.g., tick paralysis, which occurs after exposure to a neurotoxin and red meat allergy because of alpha-gal). Ticks require a blood meal to transform to their next stage of development (larva to nymph to adult). Life cycles of hard and soft ticks differ with most hard ticks undergoing a 2-year life cycle and feeding slowly over many days. In contrast, soft ticks feed multiple times often for less than 1 hour and are capable of transmitting diseases in less than 1 minute.