User login

Fetal movement education: Time to change the status quo

Every antepartum record, whether it is on paper or EMR, has a space asking whether the patient feels fetal movement at the visit. Every provider inherently knows that fetal movement is important and worth asking about at each visit. Yet the education for patients about fetal movement and when to alert a provider to changes is not currently standardized in the United States. There is no practice bulletin or guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and, therefore, there is a wide variation in clinical practice. An Australian study found that 97% of women were asked about fetal movement, but only 62% reported formal education regarding fetal movement. More concerning, only 40% were advised to call immediately if concerned about fetal movement change. A quarter were told to call only if baby moved fewer than 10 times in an hour.1

We have a standardized approach to most aspects of prenatal care. We know what to do if the patient has contractions, or protein in their urine, or an increased blood pressure. Our management and education regarding fetal movement must be standardized as well. In this article I will go through the incorrect education that often is given and the data that do not support this. We need a similar care plan or model for fetal movement education in the United States.

Myth one: Kick counts

When education is done, kick counts are far and away what providers and nurses advise in the clinic and hospital triage when women present with complaint of decreased fetal movement. The standard approach to this is advising the patient to perform a kick count several times per day to check in on the baby and call if less than 10 kicks per hour. This is not bad advice as it may help create awareness for the mom about what is “normal” for her baby and may help her to “check in” on the baby when she is occupied at work or with older children. However, advising that a kick count should be done to reassure a patient about a concerning change in fetal movement is not supported in the literature. A meta-analysis in the February 2020 issue of the Green Journal found that advised kick count monitoring did not significantly reduce stillbirth risk.2 Research shows that most moms will get 10 kicks normally within an hour, but there are no data showing what percentage of moms with perceived decreased fetal movement also will get a “passing” result despite their concern. For example, take a patient who normally feels 50 movements in an hour and is not reassured by 10 movements in an hour, but because she is told that 10 movements is okay, she tries not to worry about the concerning change. Many mothers in the stillbirth community report “passing kick counts” in the days leading up to the diagnosis. We need to move away from kick count education to a much simpler plan. We must tell patients if they are worried about a concerning change in fetal movement, they should call their provider.

Myth 2: Fetuses slow down at the end of pregnancy

There is a very common myth that fetuses slow down at the end of pregnancy, especially once labor has started. A study in the Journal of Physiology continuously monitored term fetuses when mom was both awake and asleep. The study also looked at the effect on fetal heart rate and fetal activity based on different maternal positions. The study found the fetuses spent around 90% of the day with active movements and with reactive nonstress tests (NSTs).3 A 2019 study looking at fetal movement at term and preterm in third-trimester patients illustrated that fetal movement does not decrease in frequency or strength at term. It found that only 6% of patients noted decreased strength and 14% decreased frequency of movements at term. Furthermore, 59% reported an increase in strength, and nearly 39% reported an increase in frequency of fetal movements at term.4 We must educate patients that a change in frequency or strength of movements is not normal or expected, and they must call if concerned about a change.

Myth 3: Try juice, ice water, or food before coming in for evaluation

A common set of advice when a patient calls with a complaint of decreased fetal movement is to suggest a meal or something sugary, although there is little or no evidence to support this. A randomized controlled trial found maternal perception of increased fetal movement was similar among the two groups. Giving something sugary at NST also was not shown in this study to improve reactivity.5 Another randomized, double placebo blind study was done to answer the question of whether glucose via IV helped improve fetal movements and decreased the need for admission for induction or further monitoring. In this study, no difference in outcome is found.6

When a patient calls with decreased fetal movement, advice should be to come and be evaluated, not recommendation of measures like ice water, orange juice, or sugary meal because it is not supported by the literature. This incorrect message also may further the false impression that a baby who is not moving is most likely sleeping or is simply in need of sugar, not that the baby may be at risk for impending stillbirth. The Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have fetal movement protocol that both discourage this advice and encourage immediate evaluation of patients with complaint of concerning fetal movement change.7,8

Myth 4: An increase in fetal movement is not of concern

I used to believe that increased fetal movement is never of concern. However, the STARS study illustrated that a concerning increase in fetal movement often is noted just before the diagnosis of stillbirth. A single episode of excessively vigorous activity which often is described as frantic or crazy is associated with an odds ratio for stillbirth of 4.3. In the study, 30% of cases reported this, compared with 7% of controls.9 In our practice, we manage mothers who call with this concern the same way as a decreased fetal movement complaint, and bring the mother in immediately for evaluation.

Myth 5: Patients all know that a concerning change in fetal movement is a risk factor for stillbirth

Decreased fetal movement has been associated with an increased OR for stillbirth of 4.51.10 However, patients often do not know of this association. A study in the United States of providers and stillbirth families showed fear of anxiety kept providers from talking about stillbirth and that it still happens. Because of this patients were completely surprised by the diagnosis.11 We tell patients that stillbirth still happens because research by Dr Suzanne Pullen found that 77% of families said they never worried their baby could die outside of the first trimester. Our patients have received this information without increased anxiety and are very appreciative and reassured about the education and protocol (based on the U.K. Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle Version 2) that we have implemented in our practice.

Fact: Fetal movement education guidelines exist and are easy to implement

The practice I am a partner at has been using a formalized method for educating patients about fetal movement over the past year. As mentioned earlier the U.K. and Australia have formal fetal movement education and management guidelines.7,8 Both protocols encourage formal education around 20-24 weeks and education for the patient to call immediately with concerns; the patient should be evaluated within 2 hours of the complaint. The formal education we provide is quite simple. The Star Legacy Foundation (United States) and Still Aware (Australia) have created a simple card to educate patients.

These patient-centric materials were devised from the results of the case/control cohort STARS study by Heazell et al. The STARS study demonstrated that patient report of reduced fetal movement in the 2 weeks prior to loss was associated with an OR of 12.9 for stillbirth, that decreased strength of fetal movement was associated with stillbirth OR of 2.83, and that decreased night time activity was strongly associated with impending stillbirth (74% of cases felt their fetuses died at night).12 This card also addresses sleep position data, supported by a 2018 meta-analysis in the journal Sleep Medicine. The study identified an OR for stillbirth of 2.45 for supine sleepers with LGA or average sized babies. Furthermore, if the baby was SGA and the mother slept supine, the OR for stillbirth increased to 15.66.13

Conclusions

When I think about the patients I have cared for who have presented with a stillborn baby, I think often that they usually presented for a complaint other than decreased fetal movement such as labor check or routine prenatal visit. When asked when they last felt fetal movement they will often say days before. This does not need to happen. Protocols in Norway for fetal movement education have shown that patients call sooner with decreased fetal movement when they have received a formal education.14

Not all stillbirth can be prevented but proper education about fetal movement and not perpetuating dangerous myths about fetal movement, may keep presentations like this from happening. I hope we may soon have a formal protocol for fetal movement education, but until then, I hope some will take these educational tips to heart.

Dr. Heather Florescue is an ob.gyn. in private practice at Women Gynecology and Childbirth Associates in Rochester, NY. She delivers babies at Highland Hospital in Rochester. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Oct;52(5):445-9.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):453-62.

3. J Physiol. 2017 Feb 15;595(4):1213-21.

4. PLOS One. 2019 Jun 12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217583.

5. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013 Jun;26(9):915-9.

6. J Perinatol. 2016 Aug;36(8):598-600.

7. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Aug;58(4):463-8.

8. Reduced fetal movements: Green top #57, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

9. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1555-6.

10. BMJ Open. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020031.

11. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-137.

12. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0602-4.

13. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.03.014.

14. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-32.

Every antepartum record, whether it is on paper or EMR, has a space asking whether the patient feels fetal movement at the visit. Every provider inherently knows that fetal movement is important and worth asking about at each visit. Yet the education for patients about fetal movement and when to alert a provider to changes is not currently standardized in the United States. There is no practice bulletin or guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and, therefore, there is a wide variation in clinical practice. An Australian study found that 97% of women were asked about fetal movement, but only 62% reported formal education regarding fetal movement. More concerning, only 40% were advised to call immediately if concerned about fetal movement change. A quarter were told to call only if baby moved fewer than 10 times in an hour.1

We have a standardized approach to most aspects of prenatal care. We know what to do if the patient has contractions, or protein in their urine, or an increased blood pressure. Our management and education regarding fetal movement must be standardized as well. In this article I will go through the incorrect education that often is given and the data that do not support this. We need a similar care plan or model for fetal movement education in the United States.

Myth one: Kick counts

When education is done, kick counts are far and away what providers and nurses advise in the clinic and hospital triage when women present with complaint of decreased fetal movement. The standard approach to this is advising the patient to perform a kick count several times per day to check in on the baby and call if less than 10 kicks per hour. This is not bad advice as it may help create awareness for the mom about what is “normal” for her baby and may help her to “check in” on the baby when she is occupied at work or with older children. However, advising that a kick count should be done to reassure a patient about a concerning change in fetal movement is not supported in the literature. A meta-analysis in the February 2020 issue of the Green Journal found that advised kick count monitoring did not significantly reduce stillbirth risk.2 Research shows that most moms will get 10 kicks normally within an hour, but there are no data showing what percentage of moms with perceived decreased fetal movement also will get a “passing” result despite their concern. For example, take a patient who normally feels 50 movements in an hour and is not reassured by 10 movements in an hour, but because she is told that 10 movements is okay, she tries not to worry about the concerning change. Many mothers in the stillbirth community report “passing kick counts” in the days leading up to the diagnosis. We need to move away from kick count education to a much simpler plan. We must tell patients if they are worried about a concerning change in fetal movement, they should call their provider.

Myth 2: Fetuses slow down at the end of pregnancy

There is a very common myth that fetuses slow down at the end of pregnancy, especially once labor has started. A study in the Journal of Physiology continuously monitored term fetuses when mom was both awake and asleep. The study also looked at the effect on fetal heart rate and fetal activity based on different maternal positions. The study found the fetuses spent around 90% of the day with active movements and with reactive nonstress tests (NSTs).3 A 2019 study looking at fetal movement at term and preterm in third-trimester patients illustrated that fetal movement does not decrease in frequency or strength at term. It found that only 6% of patients noted decreased strength and 14% decreased frequency of movements at term. Furthermore, 59% reported an increase in strength, and nearly 39% reported an increase in frequency of fetal movements at term.4 We must educate patients that a change in frequency or strength of movements is not normal or expected, and they must call if concerned about a change.

Myth 3: Try juice, ice water, or food before coming in for evaluation

A common set of advice when a patient calls with a complaint of decreased fetal movement is to suggest a meal or something sugary, although there is little or no evidence to support this. A randomized controlled trial found maternal perception of increased fetal movement was similar among the two groups. Giving something sugary at NST also was not shown in this study to improve reactivity.5 Another randomized, double placebo blind study was done to answer the question of whether glucose via IV helped improve fetal movements and decreased the need for admission for induction or further monitoring. In this study, no difference in outcome is found.6

When a patient calls with decreased fetal movement, advice should be to come and be evaluated, not recommendation of measures like ice water, orange juice, or sugary meal because it is not supported by the literature. This incorrect message also may further the false impression that a baby who is not moving is most likely sleeping or is simply in need of sugar, not that the baby may be at risk for impending stillbirth. The Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have fetal movement protocol that both discourage this advice and encourage immediate evaluation of patients with complaint of concerning fetal movement change.7,8

Myth 4: An increase in fetal movement is not of concern

I used to believe that increased fetal movement is never of concern. However, the STARS study illustrated that a concerning increase in fetal movement often is noted just before the diagnosis of stillbirth. A single episode of excessively vigorous activity which often is described as frantic or crazy is associated with an odds ratio for stillbirth of 4.3. In the study, 30% of cases reported this, compared with 7% of controls.9 In our practice, we manage mothers who call with this concern the same way as a decreased fetal movement complaint, and bring the mother in immediately for evaluation.

Myth 5: Patients all know that a concerning change in fetal movement is a risk factor for stillbirth

Decreased fetal movement has been associated with an increased OR for stillbirth of 4.51.10 However, patients often do not know of this association. A study in the United States of providers and stillbirth families showed fear of anxiety kept providers from talking about stillbirth and that it still happens. Because of this patients were completely surprised by the diagnosis.11 We tell patients that stillbirth still happens because research by Dr Suzanne Pullen found that 77% of families said they never worried their baby could die outside of the first trimester. Our patients have received this information without increased anxiety and are very appreciative and reassured about the education and protocol (based on the U.K. Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle Version 2) that we have implemented in our practice.

Fact: Fetal movement education guidelines exist and are easy to implement

The practice I am a partner at has been using a formalized method for educating patients about fetal movement over the past year. As mentioned earlier the U.K. and Australia have formal fetal movement education and management guidelines.7,8 Both protocols encourage formal education around 20-24 weeks and education for the patient to call immediately with concerns; the patient should be evaluated within 2 hours of the complaint. The formal education we provide is quite simple. The Star Legacy Foundation (United States) and Still Aware (Australia) have created a simple card to educate patients.

These patient-centric materials were devised from the results of the case/control cohort STARS study by Heazell et al. The STARS study demonstrated that patient report of reduced fetal movement in the 2 weeks prior to loss was associated with an OR of 12.9 for stillbirth, that decreased strength of fetal movement was associated with stillbirth OR of 2.83, and that decreased night time activity was strongly associated with impending stillbirth (74% of cases felt their fetuses died at night).12 This card also addresses sleep position data, supported by a 2018 meta-analysis in the journal Sleep Medicine. The study identified an OR for stillbirth of 2.45 for supine sleepers with LGA or average sized babies. Furthermore, if the baby was SGA and the mother slept supine, the OR for stillbirth increased to 15.66.13

Conclusions

When I think about the patients I have cared for who have presented with a stillborn baby, I think often that they usually presented for a complaint other than decreased fetal movement such as labor check or routine prenatal visit. When asked when they last felt fetal movement they will often say days before. This does not need to happen. Protocols in Norway for fetal movement education have shown that patients call sooner with decreased fetal movement when they have received a formal education.14

Not all stillbirth can be prevented but proper education about fetal movement and not perpetuating dangerous myths about fetal movement, may keep presentations like this from happening. I hope we may soon have a formal protocol for fetal movement education, but until then, I hope some will take these educational tips to heart.

Dr. Heather Florescue is an ob.gyn. in private practice at Women Gynecology and Childbirth Associates in Rochester, NY. She delivers babies at Highland Hospital in Rochester. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Oct;52(5):445-9.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):453-62.

3. J Physiol. 2017 Feb 15;595(4):1213-21.

4. PLOS One. 2019 Jun 12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217583.

5. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013 Jun;26(9):915-9.

6. J Perinatol. 2016 Aug;36(8):598-600.

7. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Aug;58(4):463-8.

8. Reduced fetal movements: Green top #57, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

9. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1555-6.

10. BMJ Open. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020031.

11. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-137.

12. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0602-4.

13. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.03.014.

14. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-32.

Every antepartum record, whether it is on paper or EMR, has a space asking whether the patient feels fetal movement at the visit. Every provider inherently knows that fetal movement is important and worth asking about at each visit. Yet the education for patients about fetal movement and when to alert a provider to changes is not currently standardized in the United States. There is no practice bulletin or guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and, therefore, there is a wide variation in clinical practice. An Australian study found that 97% of women were asked about fetal movement, but only 62% reported formal education regarding fetal movement. More concerning, only 40% were advised to call immediately if concerned about fetal movement change. A quarter were told to call only if baby moved fewer than 10 times in an hour.1

We have a standardized approach to most aspects of prenatal care. We know what to do if the patient has contractions, or protein in their urine, or an increased blood pressure. Our management and education regarding fetal movement must be standardized as well. In this article I will go through the incorrect education that often is given and the data that do not support this. We need a similar care plan or model for fetal movement education in the United States.

Myth one: Kick counts

When education is done, kick counts are far and away what providers and nurses advise in the clinic and hospital triage when women present with complaint of decreased fetal movement. The standard approach to this is advising the patient to perform a kick count several times per day to check in on the baby and call if less than 10 kicks per hour. This is not bad advice as it may help create awareness for the mom about what is “normal” for her baby and may help her to “check in” on the baby when she is occupied at work or with older children. However, advising that a kick count should be done to reassure a patient about a concerning change in fetal movement is not supported in the literature. A meta-analysis in the February 2020 issue of the Green Journal found that advised kick count monitoring did not significantly reduce stillbirth risk.2 Research shows that most moms will get 10 kicks normally within an hour, but there are no data showing what percentage of moms with perceived decreased fetal movement also will get a “passing” result despite their concern. For example, take a patient who normally feels 50 movements in an hour and is not reassured by 10 movements in an hour, but because she is told that 10 movements is okay, she tries not to worry about the concerning change. Many mothers in the stillbirth community report “passing kick counts” in the days leading up to the diagnosis. We need to move away from kick count education to a much simpler plan. We must tell patients if they are worried about a concerning change in fetal movement, they should call their provider.

Myth 2: Fetuses slow down at the end of pregnancy

There is a very common myth that fetuses slow down at the end of pregnancy, especially once labor has started. A study in the Journal of Physiology continuously monitored term fetuses when mom was both awake and asleep. The study also looked at the effect on fetal heart rate and fetal activity based on different maternal positions. The study found the fetuses spent around 90% of the day with active movements and with reactive nonstress tests (NSTs).3 A 2019 study looking at fetal movement at term and preterm in third-trimester patients illustrated that fetal movement does not decrease in frequency or strength at term. It found that only 6% of patients noted decreased strength and 14% decreased frequency of movements at term. Furthermore, 59% reported an increase in strength, and nearly 39% reported an increase in frequency of fetal movements at term.4 We must educate patients that a change in frequency or strength of movements is not normal or expected, and they must call if concerned about a change.

Myth 3: Try juice, ice water, or food before coming in for evaluation

A common set of advice when a patient calls with a complaint of decreased fetal movement is to suggest a meal or something sugary, although there is little or no evidence to support this. A randomized controlled trial found maternal perception of increased fetal movement was similar among the two groups. Giving something sugary at NST also was not shown in this study to improve reactivity.5 Another randomized, double placebo blind study was done to answer the question of whether glucose via IV helped improve fetal movements and decreased the need for admission for induction or further monitoring. In this study, no difference in outcome is found.6

When a patient calls with decreased fetal movement, advice should be to come and be evaluated, not recommendation of measures like ice water, orange juice, or sugary meal because it is not supported by the literature. This incorrect message also may further the false impression that a baby who is not moving is most likely sleeping or is simply in need of sugar, not that the baby may be at risk for impending stillbirth. The Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have fetal movement protocol that both discourage this advice and encourage immediate evaluation of patients with complaint of concerning fetal movement change.7,8

Myth 4: An increase in fetal movement is not of concern

I used to believe that increased fetal movement is never of concern. However, the STARS study illustrated that a concerning increase in fetal movement often is noted just before the diagnosis of stillbirth. A single episode of excessively vigorous activity which often is described as frantic or crazy is associated with an odds ratio for stillbirth of 4.3. In the study, 30% of cases reported this, compared with 7% of controls.9 In our practice, we manage mothers who call with this concern the same way as a decreased fetal movement complaint, and bring the mother in immediately for evaluation.

Myth 5: Patients all know that a concerning change in fetal movement is a risk factor for stillbirth

Decreased fetal movement has been associated with an increased OR for stillbirth of 4.51.10 However, patients often do not know of this association. A study in the United States of providers and stillbirth families showed fear of anxiety kept providers from talking about stillbirth and that it still happens. Because of this patients were completely surprised by the diagnosis.11 We tell patients that stillbirth still happens because research by Dr Suzanne Pullen found that 77% of families said they never worried their baby could die outside of the first trimester. Our patients have received this information without increased anxiety and are very appreciative and reassured about the education and protocol (based on the U.K. Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle Version 2) that we have implemented in our practice.

Fact: Fetal movement education guidelines exist and are easy to implement

The practice I am a partner at has been using a formalized method for educating patients about fetal movement over the past year. As mentioned earlier the U.K. and Australia have formal fetal movement education and management guidelines.7,8 Both protocols encourage formal education around 20-24 weeks and education for the patient to call immediately with concerns; the patient should be evaluated within 2 hours of the complaint. The formal education we provide is quite simple. The Star Legacy Foundation (United States) and Still Aware (Australia) have created a simple card to educate patients.

These patient-centric materials were devised from the results of the case/control cohort STARS study by Heazell et al. The STARS study demonstrated that patient report of reduced fetal movement in the 2 weeks prior to loss was associated with an OR of 12.9 for stillbirth, that decreased strength of fetal movement was associated with stillbirth OR of 2.83, and that decreased night time activity was strongly associated with impending stillbirth (74% of cases felt their fetuses died at night).12 This card also addresses sleep position data, supported by a 2018 meta-analysis in the journal Sleep Medicine. The study identified an OR for stillbirth of 2.45 for supine sleepers with LGA or average sized babies. Furthermore, if the baby was SGA and the mother slept supine, the OR for stillbirth increased to 15.66.13

Conclusions

When I think about the patients I have cared for who have presented with a stillborn baby, I think often that they usually presented for a complaint other than decreased fetal movement such as labor check or routine prenatal visit. When asked when they last felt fetal movement they will often say days before. This does not need to happen. Protocols in Norway for fetal movement education have shown that patients call sooner with decreased fetal movement when they have received a formal education.14

Not all stillbirth can be prevented but proper education about fetal movement and not perpetuating dangerous myths about fetal movement, may keep presentations like this from happening. I hope we may soon have a formal protocol for fetal movement education, but until then, I hope some will take these educational tips to heart.

Dr. Heather Florescue is an ob.gyn. in private practice at Women Gynecology and Childbirth Associates in Rochester, NY. She delivers babies at Highland Hospital in Rochester. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Oct;52(5):445-9.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):453-62.

3. J Physiol. 2017 Feb 15;595(4):1213-21.

4. PLOS One. 2019 Jun 12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217583.

5. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013 Jun;26(9):915-9.

6. J Perinatol. 2016 Aug;36(8):598-600.

7. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Aug;58(4):463-8.

8. Reduced fetal movements: Green top #57, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

9. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1555-6.

10. BMJ Open. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020031.

11. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-137.

12. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0602-4.

13. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.03.014.

14. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-32.

How to truly connect with your patients

Introducing the ‘6H model’

I vividly remember the conversation that changed the way I practice medicine today.

During my medicine residency rounds, my attending at a Veterans Affairs hospital stated: “Remember Swati, there are three simple steps to gain your patients’ trust. The three questions they have are: No. 1, who are you? No. 2, are you any good? No. 3, do you really care about me?”

The first two questions are easier to address. The third question requires us bare our authentic human self often hiding behind our white coat and medical degree.

Who are you?

- Introduce yourself (everyone is wearing scrubs/white coats – state your full name and title)

- Describe your role in patient’s care plan

- Hand them your card (your name, photo, and a short description of the role of a hospitalist)

Are you any good?

- Briefly address your professional experience

- Explicitly state all the hard work you have done prior to entering the patient’s room (reviewing past medical records, hand off from ED provider or prior hospitalist)

- State your aim to collaborate with all people involved – their primary care provider, nurse, consultant

“Hello Mrs. Jones, my name is Dr. Swati Mehta. I will be your physician today. As a hospitalist, my role is to take care of your medical needs & worries. I will coordinate with your consultants, primary care physician, and other care teams to get you the answers you need. I have been working at XYZ Hospital for 6 years and have over 12 years of experience in medicine taking care of patients. I have reviewed your medical records, blood work, and x-rays before coming in. How are you feeling today? Do you mind if I ask you a few questions?”

Addressing the third question – Do you really care about me? – is the foundation of every human interaction. Answering this question involves addressing our patients’ many fears: Do you care about what I think is going on with my disease? Will you judge me by my socioeconomic status, gender, color of my skin, or addictions? Am I safe to open up and trust you? Are we equal partners in my health care journey? Do you really care?

A successful connection is achieved when we create a space of psychological safety and mutual respect. Once that happens, our patients open up to let us in their world and become more amenable to our opinion and recommendations. That is when true healing begins.

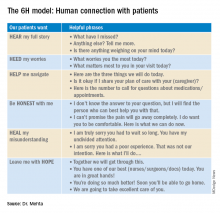

The “6H model” is an aide to form a strong human-centric connection.

The 6H model: Human connection with patients

Looking back at each patient interaction, good or bad, I have had in my almost 2 decades of practicing clinical medicine, the 6H model has brought me closer to my patients. We have formed a bond which has helped them navigate their arduous hospital journey, including medical and financial burdens, social and emotional needs. Utilizing this model, we were fortunate to receive the highest HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) Survey scores for 3 consecutive years while I served as the medical director of a 40-provider hospitalist program in a busy 450-bed hospital in Oregon.

In 2020, we are in the process of embedding the 6H model in several hospitalist programs across California. We are optimistic this intuitive approach will strengthen patient-provider relationships and ultimately improve HCAHPS scores.

To form an authentic connection with our patients doesn’t necessary require a lot of our time. Hardwiring the 6H approach when addressing our patients’ three questions is the key. The answers can change slightly, but the core message remains the same.

While we might not have much influence on all the factors that make or break our patients’ experience, the patient encounter is where we can truly make a difference. Consider using this 6H model in your next clinical shift. Human connection in health care is the need of the hour. Let’s bring “care” back to health care.

Dr. Mehta is director of quality & performance and patient experience at Vituity in Emeryville, Calif., and vice chair of the SHM patient experience committee.

Introducing the ‘6H model’

Introducing the ‘6H model’

I vividly remember the conversation that changed the way I practice medicine today.

During my medicine residency rounds, my attending at a Veterans Affairs hospital stated: “Remember Swati, there are three simple steps to gain your patients’ trust. The three questions they have are: No. 1, who are you? No. 2, are you any good? No. 3, do you really care about me?”

The first two questions are easier to address. The third question requires us bare our authentic human self often hiding behind our white coat and medical degree.

Who are you?

- Introduce yourself (everyone is wearing scrubs/white coats – state your full name and title)

- Describe your role in patient’s care plan

- Hand them your card (your name, photo, and a short description of the role of a hospitalist)

Are you any good?

- Briefly address your professional experience

- Explicitly state all the hard work you have done prior to entering the patient’s room (reviewing past medical records, hand off from ED provider or prior hospitalist)

- State your aim to collaborate with all people involved – their primary care provider, nurse, consultant

“Hello Mrs. Jones, my name is Dr. Swati Mehta. I will be your physician today. As a hospitalist, my role is to take care of your medical needs & worries. I will coordinate with your consultants, primary care physician, and other care teams to get you the answers you need. I have been working at XYZ Hospital for 6 years and have over 12 years of experience in medicine taking care of patients. I have reviewed your medical records, blood work, and x-rays before coming in. How are you feeling today? Do you mind if I ask you a few questions?”

Addressing the third question – Do you really care about me? – is the foundation of every human interaction. Answering this question involves addressing our patients’ many fears: Do you care about what I think is going on with my disease? Will you judge me by my socioeconomic status, gender, color of my skin, or addictions? Am I safe to open up and trust you? Are we equal partners in my health care journey? Do you really care?

A successful connection is achieved when we create a space of psychological safety and mutual respect. Once that happens, our patients open up to let us in their world and become more amenable to our opinion and recommendations. That is when true healing begins.

The “6H model” is an aide to form a strong human-centric connection.

The 6H model: Human connection with patients

Looking back at each patient interaction, good or bad, I have had in my almost 2 decades of practicing clinical medicine, the 6H model has brought me closer to my patients. We have formed a bond which has helped them navigate their arduous hospital journey, including medical and financial burdens, social and emotional needs. Utilizing this model, we were fortunate to receive the highest HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) Survey scores for 3 consecutive years while I served as the medical director of a 40-provider hospitalist program in a busy 450-bed hospital in Oregon.

In 2020, we are in the process of embedding the 6H model in several hospitalist programs across California. We are optimistic this intuitive approach will strengthen patient-provider relationships and ultimately improve HCAHPS scores.

To form an authentic connection with our patients doesn’t necessary require a lot of our time. Hardwiring the 6H approach when addressing our patients’ three questions is the key. The answers can change slightly, but the core message remains the same.

While we might not have much influence on all the factors that make or break our patients’ experience, the patient encounter is where we can truly make a difference. Consider using this 6H model in your next clinical shift. Human connection in health care is the need of the hour. Let’s bring “care” back to health care.

Dr. Mehta is director of quality & performance and patient experience at Vituity in Emeryville, Calif., and vice chair of the SHM patient experience committee.

I vividly remember the conversation that changed the way I practice medicine today.

During my medicine residency rounds, my attending at a Veterans Affairs hospital stated: “Remember Swati, there are three simple steps to gain your patients’ trust. The three questions they have are: No. 1, who are you? No. 2, are you any good? No. 3, do you really care about me?”

The first two questions are easier to address. The third question requires us bare our authentic human self often hiding behind our white coat and medical degree.

Who are you?

- Introduce yourself (everyone is wearing scrubs/white coats – state your full name and title)

- Describe your role in patient’s care plan

- Hand them your card (your name, photo, and a short description of the role of a hospitalist)

Are you any good?

- Briefly address your professional experience

- Explicitly state all the hard work you have done prior to entering the patient’s room (reviewing past medical records, hand off from ED provider or prior hospitalist)

- State your aim to collaborate with all people involved – their primary care provider, nurse, consultant

“Hello Mrs. Jones, my name is Dr. Swati Mehta. I will be your physician today. As a hospitalist, my role is to take care of your medical needs & worries. I will coordinate with your consultants, primary care physician, and other care teams to get you the answers you need. I have been working at XYZ Hospital for 6 years and have over 12 years of experience in medicine taking care of patients. I have reviewed your medical records, blood work, and x-rays before coming in. How are you feeling today? Do you mind if I ask you a few questions?”

Addressing the third question – Do you really care about me? – is the foundation of every human interaction. Answering this question involves addressing our patients’ many fears: Do you care about what I think is going on with my disease? Will you judge me by my socioeconomic status, gender, color of my skin, or addictions? Am I safe to open up and trust you? Are we equal partners in my health care journey? Do you really care?

A successful connection is achieved when we create a space of psychological safety and mutual respect. Once that happens, our patients open up to let us in their world and become more amenable to our opinion and recommendations. That is when true healing begins.

The “6H model” is an aide to form a strong human-centric connection.

The 6H model: Human connection with patients

Looking back at each patient interaction, good or bad, I have had in my almost 2 decades of practicing clinical medicine, the 6H model has brought me closer to my patients. We have formed a bond which has helped them navigate their arduous hospital journey, including medical and financial burdens, social and emotional needs. Utilizing this model, we were fortunate to receive the highest HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) Survey scores for 3 consecutive years while I served as the medical director of a 40-provider hospitalist program in a busy 450-bed hospital in Oregon.

In 2020, we are in the process of embedding the 6H model in several hospitalist programs across California. We are optimistic this intuitive approach will strengthen patient-provider relationships and ultimately improve HCAHPS scores.

To form an authentic connection with our patients doesn’t necessary require a lot of our time. Hardwiring the 6H approach when addressing our patients’ three questions is the key. The answers can change slightly, but the core message remains the same.

While we might not have much influence on all the factors that make or break our patients’ experience, the patient encounter is where we can truly make a difference. Consider using this 6H model in your next clinical shift. Human connection in health care is the need of the hour. Let’s bring “care” back to health care.

Dr. Mehta is director of quality & performance and patient experience at Vituity in Emeryville, Calif., and vice chair of the SHM patient experience committee.

Action and awareness are needed to increase immunization rates

August was National Immunization Awareness Month. ... just in time to address the precipitous drop in immunization delivered during the early months of the pandemic.

In May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported substantial reductions in vaccine doses ordered through the Vaccines for Children program after the declaration of national emergency because of COVID-19 on March 13. Approximately 2.5 million fewer doses of routine, noninfluenza vaccines were administered between Jan. 6 and April 2020, compared with a similar period last year (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 May 15;69[19]:591-3). Declines in immunization rates were echoed by states and municipalities across the United States. Last month, the health system in which I work reported 40,000 children behind on at least one vaccine.

We all know that, when immunization rates drop, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases follow. In order and that is going to take more than a single month.

Identify patients who’ve missed vaccinations

Simply being open and ready to vaccinate is not enough. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urges providers to identify patients who have missed vaccines, and call them to schedule in-person visits. Proactively let parents know about strategies implemented in your office to ensure a safe environment.

Pediatricians are accustomed to an influx of patients in the summer, as parents make sure their children have all of the vaccines required for school attendance. As noted in a Washington Post article from Aug. 4, 2020, schools have traditionally served as a backstop for immunization rates. But as many school districts opt to take education online this fall, the implications for vaccine requirements are unclear. District of Columbia public schools continue to require immunization for virtual school attendance, but it is not clear how easily this can be enforced. To read about how other school districts have chosen to address – or not address – immunization requirements for school, visit the the Immunization Action Coalition’s Repository of Resources for Maintaining Immunization during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The repository links to international, national, and state-level policies and guidance and advocacy materials, including talking points, webinars, press releases, media articles from around the United States and social media posts, as well as telehealth resources.

Get some inspiration to talk about vaccination

Need a little inspiration for talking to parents about vaccines? Check out the CDC’s #HowIRecommend video series. These are short videos, most under a minute in length, that explain the importance of vaccination, how to effectively address questions from parents about vaccine safety, and how clinicians routinely recommend same day vaccination to their patients. These videos are part of the CDC’s National Immunization Awareness Month (NIAM) toolkit for communication with health care professionals. A companion toolkit for communicating with parents and patients contains sample social media messages with graphics, along with educational resources to share with parents.

The “Comprehensive Vaccine Education Program – From Training to Practice,” a free online program offered by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, takes a deeper dive into strategies to combat vaccine misinformation and address vaccine hesitancy. Available modules cover vaccine fundamentals, vaccine safety, clinical manifestations of vaccine-preventable diseases, and communication skills that lead to more effective conversations with patients and parents. The curriculum also includes the newest edition of The Vaccine Handbook app, a comprehensive source of practical information for vaccine providers.

Educate young children about vaccines

Don’t leave young children out of the conversation. Vax-Force is a children’s book that explores how vaccination works inside the human body. Dr. Vaxson the pediatrician explains how trusted doctors and scientists made Vicky the Vaccine. Her mission is to tell Willy the White Blood Cell and his Antibuddies how to find and fight bad-guy germs like measles, tetanus, and polio. The book was written by Kelsey Rowe, MD, while she was a medical student at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Dr. Rowe, now a pediatric resident, notes, “In a world where anti-vaccination rhetoric threatens the health of our global community, this book’s mission is to teach children and adults alike that getting vaccinations is a safe, effective, and even exciting thing to do.” The book is available for purchase at https://www.vax-force.com/, and a small part of every sale is donated to Unicef USA.

Consider vaccination advocacy in your communities

Vaccinate Your Family, a national, nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting people of all ages from vaccine-preventable diseases, suggests that health care providers need to take an active role in raising immunization rates, not just in their own practices, but in their communities. One way to do this is to submit an opinion piece or letter to the editor to a local newspaper describing why it’s important for parents to make sure their child’s immunizations are current. Those who have never written an opinion-editorial should look at the guidance developed by Voices for Vaccines.

How are we doing?

Early data suggest a rebound in immunization rates in May and June, but that is unlikely to close the gap created by disruptions in health care delivery earlier in the year. Collectively, we need to set ambitious goals. Are we just trying to reach prepandemic immunization levels? In Kentucky, where I practice, only 71% of kids aged 19-45 months had received all doses of seven routinely recommended vaccines (≥4 DTaP doses, ≥3 polio doses, ≥1 MMR dose, Hib full series, ≥3 HepB doses, ≥1 varicella dose, and ≥4 PCV doses) based on 2017 National Immunization Survey data. The Healthy People 2020 target goal is 80%. Only 55% of Kentucky girls aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of HPV vaccine, and rates in boys were even lower. Flu vaccine coverage in children 6 months to 17 years also was 55%. The status quo sets the bar too low. To see how your state is doing, check out the interactive map developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Are we attempting to avoid disaster or can we seize the opportunity to protect more children than ever from vaccine-preventable diseases? The latter would really be something to celebrate.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

August was National Immunization Awareness Month. ... just in time to address the precipitous drop in immunization delivered during the early months of the pandemic.

In May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported substantial reductions in vaccine doses ordered through the Vaccines for Children program after the declaration of national emergency because of COVID-19 on March 13. Approximately 2.5 million fewer doses of routine, noninfluenza vaccines were administered between Jan. 6 and April 2020, compared with a similar period last year (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 May 15;69[19]:591-3). Declines in immunization rates were echoed by states and municipalities across the United States. Last month, the health system in which I work reported 40,000 children behind on at least one vaccine.

We all know that, when immunization rates drop, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases follow. In order and that is going to take more than a single month.

Identify patients who’ve missed vaccinations

Simply being open and ready to vaccinate is not enough. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urges providers to identify patients who have missed vaccines, and call them to schedule in-person visits. Proactively let parents know about strategies implemented in your office to ensure a safe environment.

Pediatricians are accustomed to an influx of patients in the summer, as parents make sure their children have all of the vaccines required for school attendance. As noted in a Washington Post article from Aug. 4, 2020, schools have traditionally served as a backstop for immunization rates. But as many school districts opt to take education online this fall, the implications for vaccine requirements are unclear. District of Columbia public schools continue to require immunization for virtual school attendance, but it is not clear how easily this can be enforced. To read about how other school districts have chosen to address – or not address – immunization requirements for school, visit the the Immunization Action Coalition’s Repository of Resources for Maintaining Immunization during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The repository links to international, national, and state-level policies and guidance and advocacy materials, including talking points, webinars, press releases, media articles from around the United States and social media posts, as well as telehealth resources.

Get some inspiration to talk about vaccination

Need a little inspiration for talking to parents about vaccines? Check out the CDC’s #HowIRecommend video series. These are short videos, most under a minute in length, that explain the importance of vaccination, how to effectively address questions from parents about vaccine safety, and how clinicians routinely recommend same day vaccination to their patients. These videos are part of the CDC’s National Immunization Awareness Month (NIAM) toolkit for communication with health care professionals. A companion toolkit for communicating with parents and patients contains sample social media messages with graphics, along with educational resources to share with parents.

The “Comprehensive Vaccine Education Program – From Training to Practice,” a free online program offered by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, takes a deeper dive into strategies to combat vaccine misinformation and address vaccine hesitancy. Available modules cover vaccine fundamentals, vaccine safety, clinical manifestations of vaccine-preventable diseases, and communication skills that lead to more effective conversations with patients and parents. The curriculum also includes the newest edition of The Vaccine Handbook app, a comprehensive source of practical information for vaccine providers.

Educate young children about vaccines

Don’t leave young children out of the conversation. Vax-Force is a children’s book that explores how vaccination works inside the human body. Dr. Vaxson the pediatrician explains how trusted doctors and scientists made Vicky the Vaccine. Her mission is to tell Willy the White Blood Cell and his Antibuddies how to find and fight bad-guy germs like measles, tetanus, and polio. The book was written by Kelsey Rowe, MD, while she was a medical student at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Dr. Rowe, now a pediatric resident, notes, “In a world where anti-vaccination rhetoric threatens the health of our global community, this book’s mission is to teach children and adults alike that getting vaccinations is a safe, effective, and even exciting thing to do.” The book is available for purchase at https://www.vax-force.com/, and a small part of every sale is donated to Unicef USA.

Consider vaccination advocacy in your communities

Vaccinate Your Family, a national, nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting people of all ages from vaccine-preventable diseases, suggests that health care providers need to take an active role in raising immunization rates, not just in their own practices, but in their communities. One way to do this is to submit an opinion piece or letter to the editor to a local newspaper describing why it’s important for parents to make sure their child’s immunizations are current. Those who have never written an opinion-editorial should look at the guidance developed by Voices for Vaccines.

How are we doing?

Early data suggest a rebound in immunization rates in May and June, but that is unlikely to close the gap created by disruptions in health care delivery earlier in the year. Collectively, we need to set ambitious goals. Are we just trying to reach prepandemic immunization levels? In Kentucky, where I practice, only 71% of kids aged 19-45 months had received all doses of seven routinely recommended vaccines (≥4 DTaP doses, ≥3 polio doses, ≥1 MMR dose, Hib full series, ≥3 HepB doses, ≥1 varicella dose, and ≥4 PCV doses) based on 2017 National Immunization Survey data. The Healthy People 2020 target goal is 80%. Only 55% of Kentucky girls aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of HPV vaccine, and rates in boys were even lower. Flu vaccine coverage in children 6 months to 17 years also was 55%. The status quo sets the bar too low. To see how your state is doing, check out the interactive map developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Are we attempting to avoid disaster or can we seize the opportunity to protect more children than ever from vaccine-preventable diseases? The latter would really be something to celebrate.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

August was National Immunization Awareness Month. ... just in time to address the precipitous drop in immunization delivered during the early months of the pandemic.

In May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported substantial reductions in vaccine doses ordered through the Vaccines for Children program after the declaration of national emergency because of COVID-19 on March 13. Approximately 2.5 million fewer doses of routine, noninfluenza vaccines were administered between Jan. 6 and April 2020, compared with a similar period last year (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 May 15;69[19]:591-3). Declines in immunization rates were echoed by states and municipalities across the United States. Last month, the health system in which I work reported 40,000 children behind on at least one vaccine.

We all know that, when immunization rates drop, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases follow. In order and that is going to take more than a single month.

Identify patients who’ve missed vaccinations

Simply being open and ready to vaccinate is not enough. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urges providers to identify patients who have missed vaccines, and call them to schedule in-person visits. Proactively let parents know about strategies implemented in your office to ensure a safe environment.

Pediatricians are accustomed to an influx of patients in the summer, as parents make sure their children have all of the vaccines required for school attendance. As noted in a Washington Post article from Aug. 4, 2020, schools have traditionally served as a backstop for immunization rates. But as many school districts opt to take education online this fall, the implications for vaccine requirements are unclear. District of Columbia public schools continue to require immunization for virtual school attendance, but it is not clear how easily this can be enforced. To read about how other school districts have chosen to address – or not address – immunization requirements for school, visit the the Immunization Action Coalition’s Repository of Resources for Maintaining Immunization during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The repository links to international, national, and state-level policies and guidance and advocacy materials, including talking points, webinars, press releases, media articles from around the United States and social media posts, as well as telehealth resources.

Get some inspiration to talk about vaccination

Need a little inspiration for talking to parents about vaccines? Check out the CDC’s #HowIRecommend video series. These are short videos, most under a minute in length, that explain the importance of vaccination, how to effectively address questions from parents about vaccine safety, and how clinicians routinely recommend same day vaccination to their patients. These videos are part of the CDC’s National Immunization Awareness Month (NIAM) toolkit for communication with health care professionals. A companion toolkit for communicating with parents and patients contains sample social media messages with graphics, along with educational resources to share with parents.

The “Comprehensive Vaccine Education Program – From Training to Practice,” a free online program offered by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, takes a deeper dive into strategies to combat vaccine misinformation and address vaccine hesitancy. Available modules cover vaccine fundamentals, vaccine safety, clinical manifestations of vaccine-preventable diseases, and communication skills that lead to more effective conversations with patients and parents. The curriculum also includes the newest edition of The Vaccine Handbook app, a comprehensive source of practical information for vaccine providers.

Educate young children about vaccines

Don’t leave young children out of the conversation. Vax-Force is a children’s book that explores how vaccination works inside the human body. Dr. Vaxson the pediatrician explains how trusted doctors and scientists made Vicky the Vaccine. Her mission is to tell Willy the White Blood Cell and his Antibuddies how to find and fight bad-guy germs like measles, tetanus, and polio. The book was written by Kelsey Rowe, MD, while she was a medical student at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Dr. Rowe, now a pediatric resident, notes, “In a world where anti-vaccination rhetoric threatens the health of our global community, this book’s mission is to teach children and adults alike that getting vaccinations is a safe, effective, and even exciting thing to do.” The book is available for purchase at https://www.vax-force.com/, and a small part of every sale is donated to Unicef USA.

Consider vaccination advocacy in your communities

Vaccinate Your Family, a national, nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting people of all ages from vaccine-preventable diseases, suggests that health care providers need to take an active role in raising immunization rates, not just in their own practices, but in their communities. One way to do this is to submit an opinion piece or letter to the editor to a local newspaper describing why it’s important for parents to make sure their child’s immunizations are current. Those who have never written an opinion-editorial should look at the guidance developed by Voices for Vaccines.

How are we doing?

Early data suggest a rebound in immunization rates in May and June, but that is unlikely to close the gap created by disruptions in health care delivery earlier in the year. Collectively, we need to set ambitious goals. Are we just trying to reach prepandemic immunization levels? In Kentucky, where I practice, only 71% of kids aged 19-45 months had received all doses of seven routinely recommended vaccines (≥4 DTaP doses, ≥3 polio doses, ≥1 MMR dose, Hib full series, ≥3 HepB doses, ≥1 varicella dose, and ≥4 PCV doses) based on 2017 National Immunization Survey data. The Healthy People 2020 target goal is 80%. Only 55% of Kentucky girls aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of HPV vaccine, and rates in boys were even lower. Flu vaccine coverage in children 6 months to 17 years also was 55%. The status quo sets the bar too low. To see how your state is doing, check out the interactive map developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Are we attempting to avoid disaster or can we seize the opportunity to protect more children than ever from vaccine-preventable diseases? The latter would really be something to celebrate.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Pandemic effect: Telemedicine is now a ‘must-have’ service

If people try telemedicine, they’ll like telemedicine. And if they want to avoid a doctor’s office, as most people do these days, they’ll try telemedicine. That is the message coming from 1,000 people surveyed for DocASAP, a provider of online patient access and engagement systems.

Here are a couple of numbers: 92% of those who made a telemedicine visit said they were satisfied with the overall appointment experience, and 91% said that they are more likely to schedule a telemedicine visit instead of an in-person appointment. All of the survey respondents had visited a health care provider in the past year, and 40% already had made a telemedicine visit, DocASAP reported.

Puneet Maheshwari, DocASAP cofounder and CEO, said in a statement. “As providers continue to adopt innovative technology to power a more seamless, end-to-end digital consumer experience, I expect telehealth to become fully integrated into overall care management.”

For now, though, COVID-19 is an overriding concern and health care facilities are suspect. When respondents were asked to identify the types of public facilities where they felt safe, hospitals were named by 32%, doctors’ offices by 26%, and ED/urgent care by just 12%, the DocASAP report said. Even public transportation got 13%.

The safest place to be, according to 42% of the respondents? The grocery store.

Of those surveyed, 43% “indicated they will not feel safe entering any health care setting until at least the fall,” the company said. An even higher share of patients, 68%, canceled or postponed an in-person appointment during the pandemic.

“No longer are remote health services viewed as ‘nice to have’ – they are now a must-have care delivery option,” DocASAP said in their report.

Safety concerns involving COVID-19, named by 47% of the sample, were the leading factor that would influence patients’ decision to schedule a telemedicine visit. Insurance coverage was next at 43%, followed by “ease of accessing quality care” at 40%, the report said.

Among those who had made a telemedicine visit, scheduling the appointment was the most satisfying aspect of the experience, according to 54% of respondents, with day-of-appointment wait time next at 38% and quality of the video/audio technology tied with preappointment communication at almost 33%, the survey data show.

Conversely, scheduling the appointment also was declared the most frustrating aspect of the telemedicine experience, although the total in that category was a much lower 29%.

“The pandemic has thrust profound change on every aspect of life, particularly health care. … Innovations – like digital and telehealth solutions – designed to meet patient needs will likely become embedded into the health care delivery system,” DocASAP said.

The survey was commissioned by DocASAP and conducted by marketing research company OnePoll on June 29-30, 2020.

If people try telemedicine, they’ll like telemedicine. And if they want to avoid a doctor’s office, as most people do these days, they’ll try telemedicine. That is the message coming from 1,000 people surveyed for DocASAP, a provider of online patient access and engagement systems.

Here are a couple of numbers: 92% of those who made a telemedicine visit said they were satisfied with the overall appointment experience, and 91% said that they are more likely to schedule a telemedicine visit instead of an in-person appointment. All of the survey respondents had visited a health care provider in the past year, and 40% already had made a telemedicine visit, DocASAP reported.

Puneet Maheshwari, DocASAP cofounder and CEO, said in a statement. “As providers continue to adopt innovative technology to power a more seamless, end-to-end digital consumer experience, I expect telehealth to become fully integrated into overall care management.”

For now, though, COVID-19 is an overriding concern and health care facilities are suspect. When respondents were asked to identify the types of public facilities where they felt safe, hospitals were named by 32%, doctors’ offices by 26%, and ED/urgent care by just 12%, the DocASAP report said. Even public transportation got 13%.

The safest place to be, according to 42% of the respondents? The grocery store.

Of those surveyed, 43% “indicated they will not feel safe entering any health care setting until at least the fall,” the company said. An even higher share of patients, 68%, canceled or postponed an in-person appointment during the pandemic.

“No longer are remote health services viewed as ‘nice to have’ – they are now a must-have care delivery option,” DocASAP said in their report.

Safety concerns involving COVID-19, named by 47% of the sample, were the leading factor that would influence patients’ decision to schedule a telemedicine visit. Insurance coverage was next at 43%, followed by “ease of accessing quality care” at 40%, the report said.

Among those who had made a telemedicine visit, scheduling the appointment was the most satisfying aspect of the experience, according to 54% of respondents, with day-of-appointment wait time next at 38% and quality of the video/audio technology tied with preappointment communication at almost 33%, the survey data show.

Conversely, scheduling the appointment also was declared the most frustrating aspect of the telemedicine experience, although the total in that category was a much lower 29%.

“The pandemic has thrust profound change on every aspect of life, particularly health care. … Innovations – like digital and telehealth solutions – designed to meet patient needs will likely become embedded into the health care delivery system,” DocASAP said.

The survey was commissioned by DocASAP and conducted by marketing research company OnePoll on June 29-30, 2020.

If people try telemedicine, they’ll like telemedicine. And if they want to avoid a doctor’s office, as most people do these days, they’ll try telemedicine. That is the message coming from 1,000 people surveyed for DocASAP, a provider of online patient access and engagement systems.

Here are a couple of numbers: 92% of those who made a telemedicine visit said they were satisfied with the overall appointment experience, and 91% said that they are more likely to schedule a telemedicine visit instead of an in-person appointment. All of the survey respondents had visited a health care provider in the past year, and 40% already had made a telemedicine visit, DocASAP reported.

Puneet Maheshwari, DocASAP cofounder and CEO, said in a statement. “As providers continue to adopt innovative technology to power a more seamless, end-to-end digital consumer experience, I expect telehealth to become fully integrated into overall care management.”

For now, though, COVID-19 is an overriding concern and health care facilities are suspect. When respondents were asked to identify the types of public facilities where they felt safe, hospitals were named by 32%, doctors’ offices by 26%, and ED/urgent care by just 12%, the DocASAP report said. Even public transportation got 13%.

The safest place to be, according to 42% of the respondents? The grocery store.

Of those surveyed, 43% “indicated they will not feel safe entering any health care setting until at least the fall,” the company said. An even higher share of patients, 68%, canceled or postponed an in-person appointment during the pandemic.

“No longer are remote health services viewed as ‘nice to have’ – they are now a must-have care delivery option,” DocASAP said in their report.

Safety concerns involving COVID-19, named by 47% of the sample, were the leading factor that would influence patients’ decision to schedule a telemedicine visit. Insurance coverage was next at 43%, followed by “ease of accessing quality care” at 40%, the report said.

Among those who had made a telemedicine visit, scheduling the appointment was the most satisfying aspect of the experience, according to 54% of respondents, with day-of-appointment wait time next at 38% and quality of the video/audio technology tied with preappointment communication at almost 33%, the survey data show.

Conversely, scheduling the appointment also was declared the most frustrating aspect of the telemedicine experience, although the total in that category was a much lower 29%.

“The pandemic has thrust profound change on every aspect of life, particularly health care. … Innovations – like digital and telehealth solutions – designed to meet patient needs will likely become embedded into the health care delivery system,” DocASAP said.

The survey was commissioned by DocASAP and conducted by marketing research company OnePoll on June 29-30, 2020.

Back to school: How pediatricians can help LGBTQ youth

September every year means one thing to students across the country: Summer break is over, and it is time to go back to school. For LGBTQ youth, this can be both a blessing and a curse. Schools can be a refuge from being stuck at home with unsupportive family, but it also can mean returning to hallways full of harassment from other students and/or staff. Groups such as a gender-sexuality alliance (GSA) or a chapter of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) can provide a safe space for these students at school. Pediatricians can play an important role in ensuring that their patients know about access to these resources.

Gender-sexuality alliances, or gay-straight alliances as they have been more commonly known, have been around since the late 1980s. The first one was founded at Concord Academy in Massachusetts in 1988 by a straight student who was upset at how her gay classmates were being treated. Today’s GSAs continue this mission to create a welcoming environment for students of all gender identities and sexual orientations to gather, increase awareness on their campus of LGBTQ issues, and make the school environment safer for all students. According to the GSA network, there are over 4,000 active GSAs today in the United States located in 40 states.1

GLSEN was founded in 1990 initially as a network of gay and lesbian educators who wanted to create safer spaces in schools for LGBTQ students. Over the last 30 years, GLSEN continues to support this mission but has expanded into research and advocacy as well. There are currently 43 chapters of GLSEN in 30 states.2 GLSEN sponsors a number of national events throughout the year to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues in schools, including No Name Calling Week and the Day of Silence. Many chapters provide mentoring to local GSAs and volunteering as a mentor can be a great way for pediatricians to become involved in their local schools.

You may be asking yourself, why are GSAs important? According to GLSEN’s 2017 National School Climate Survey, nearly 35% of LGBTQ students missed at least 1 day of school in the previous month because of feeling unsafe, and nearly 57% of students reported hearing homophobic remarks from teachers and staff at their school.3 Around 10% of LGBTQ students reported being physically assaulted based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Those LGBTQ students who experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity were more likely to have lower grade point averages and were more likely to be disciplined than those students who had not experienced discrimination.3 The cumulative effect of these negative experiences at school lead a sizable portion of affected students to drop out of school and possibly not pursue postsecondary education. This then leads to decreased job opportunities or career advancement, which could then lead to unemployment or low-wage jobs. Creating safe spaces for education to take place can have a lasting effect on the lives of LGBTQ students.

The 53% of students who reported having a GSA at their school in the National School Climate survey were less likely to report hearing negative comments about LGBTQ students, were less likely to miss school, experienced lower levels of victimization, and reported higher levels of supportive teachers and staff. All of these factors taken together ensure that LGBTQ students are more likely to complete their high school education. Russell B. Toomey, PhD, and colleagues were able to show that LGBTQ students with a perceived effective GSA were two times more likely than those without an effective GSA to attain a college education.4 Research also has shown that the presence of a GSA can have a beneficial impact on reducing bullying in general for all students, whether they identify as LGBTQ or not.5

What active steps can a pediatrician take to support their LGBTQ students? First, If the families run into trouble from the school, have your social workers help them connect with legal resources, as many court cases have established precedent that public schools cannot have a blanket ban on GSAs solely because they focus on LGBTQ issues. Second, if your patient has a GSA at their school and seems to be struggling with his/her sexual orientation and/or gender identity, encourage that student to consider attending their GSA so that they are able to spend time with other students like themselves. Third, as many schools will be starting virtually this year, you can provide your LGBTQ patients with a list of local online groups that students can participate in virtually if their school’s GSA is not meeting (see my LGBTQ Youth Consult column entitled, “Resources for LGBTQ youth during challenging times” at mdedge.com/pediatrics for a few ideas).* Lastly, be an active advocate in your own local school district for the inclusion of comprehensive nondiscrimination policies and the presence of GSAs for students. These small steps can go a long way to helping your LGBTQ patients thrive and succeed in school.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. Dr. Cooper has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. gsanetwork.org/mission-vision-history/.

2. www.glsen.org/find_chapter?field_chapter_state_target_id=All.

3. live-glsen-website.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2019-10/GLSEN-2017-National-School-Climate-Survey-NSCS-Full-Report.pdf.

4. Appl Dev Sci. 2011 Nov 7;15(4):175-85.

5.www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-08-04/gay-straight-alliances-in-schools-pay-off-for-all-students-study-finds.

*This article was updated 8/17/2020.