User login

Hospital medicine and the future of smart care

People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten. – Bill Gates

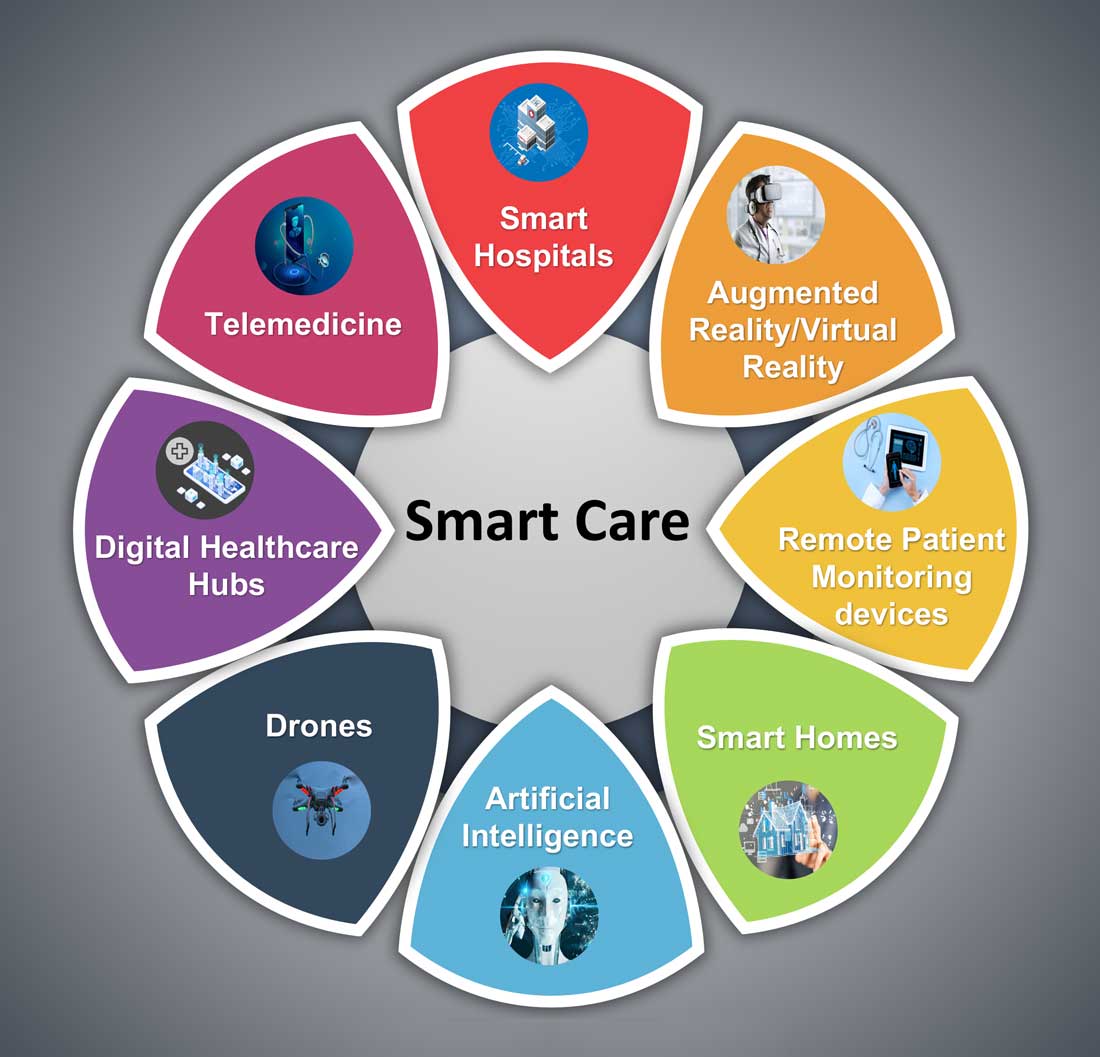

The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion a series of innovations catalyzing the digital transformation of the health care landscape.

Telemedicine use exploded over the last 12 months to the point that it has almost become ubiquitous. With that, we saw a rapid proliferation of wearables and remote patient monitoring devices. Thanks to virtual care, care delivery is no longer strictly dependent on having onsite specialists, and care itself is not confined to the boundaries of hospitals or doctors’ offices anymore.

We saw the formation of the digital front door and the emergence of new virtual care sites like virtual urgent care, virtual home health, virtual office visits, virtual hospital at home that allowed clinical care to be delivered safely outside the boundaries of hospitals. Nonclinical public places like gyms, schools, and community centers were being transformed into virtual health care portals that brought care closer to the people.

Inside the hospital, we saw a fusion of traditional inpatient care and virtual care. Onsite hospital teams embraced telemedicine during the pandemic for various reasons; to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), limit exposure, boost care capacity, improve access to specialists at distant sites, and bring family memberse to “webside” who cannot be at a patient’s bedside.

In clinical trials as well, virtual care is a welcome change. According to one survey1, most trial participants favored the use of telehealth services for clinical trials, as these helped them stay engaged, compliant, monitored, and on track while remaining at home. Furthermore, we are seeing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into telehealth, whether it is to aid physicians in clinical decision-making or to generate reminders to help patients with chronic disease management. However, this integration is only beginning to scratch the surface of the combination of two technologies’ real potential.

What’s next?

Based on these trends, it should be no surprise that digital health will become a vital sign for health care organizations.

The next 12 to 24 months will set new standards for digital health and play a significant role in defining the next generation of virtual care. There are projections that global health care industry revenues will exceed $2.6 trillion by 2025, with AI and telehealth playing a prominent role in this growth.2 According to estimates, telehealth itself will be a $175 billion market by 2026 and approximately one in three patient encounters will go virtual.3,4 Moreover, virtual care will continue to make exciting transformations, helping to make quality care accessible to everyone in innovative ways. For example, the University of Cincinnati has recently developed a pilot project using a drone equipped with video technology, artificial intelligence, sensors, and first aid kits to go to hard-to-reach areas to deliver care via telemedicine.5

Smart hospitals

In coming years, we can expect the integration of AI, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) into telemedicine at lightning speed – and at a much larger scale – that will enable surgeons from different parts of the globe to perform procedures remotely and more precisely.

AI is already gaining traction in different fields within health care – whether it’s predicting length of stay in the ICU, or assisting in triage decisions, or reading radiological images, to name just a few. The Mayo Clinic is using AI and computer-aided decision-making tools to predict the risk of surgery and potential post-op complications, which could allow even better collaboration between medical and surgical teams. We hear about the “X-ray” vision offered to proceduralists using HoloLens – mixed reality smartglasses – a technology that enables them to perform procedures more precisely. Others project that there will be more sensors and voice recognition tools in the OR that will be used to gather data to develop intelligent algorithms, and to build a safety net for interventionalists that can notify them of potential hazards or accidental sterile field breaches. The insights gained will be used to create best practices and even allow some procedures to be performed outside the traditional OR setting.

Additionally, we are seeing the development of “smart” patient rooms. For example, one health system in Florida is working on deploying Amazon Alexa in 2,500 patient rooms to allow patients to connect more easily to their care team members. In the not-so-distant future, smart hospitals with smart patient rooms and smart ORs equipped with telemedicine, AI, AR, mixed reality, and computer-aided decision-making tools will no longer be an exception.

Smart homes for smart care

Smart homes with technologies like gas detectors, movement sensors, and sleep sensors will continue to evolve. According to one estimate, the global smart home health care market was $8.7 billion in 2019, and is expected to be $96.2 billion by 2030.6

Smart technologies will have applications in fall detection and prevention, evaluation of self-administration of medicine, sleep rhythm monitoring, air quality monitoring for the detection of abnormal gas levels, and identification of things like carbon monoxide poisoning or food spoilage. In coming years, expect to see more virtual medical homes and digital health care complexes. Patients, from the convenience of their homes, might be able to connect to a suite of caregivers, all working collaboratively to provide more coordinated, effective care. The “hospital at home” model that started with six hospitals has already grown to over 100 hospitals across 29 states. The shift from onsite specialists to onscreen specialists will continue, providing greater access to specialized services.

With these emerging trends, it can be anticipated that much acute care will be provided to patients outside the hospital – either under the hospital at home model, via drone technology using telemedicine, through smart devices in smart homes, or via wearables and artificial intelligence. Hence, hospitals’ configuration in the future will be much different and more compact than currently, and many hospitals will be reserved for trauma patients, casualties of natural disasters, higher acuity diseases requiring complex procedures, and other emergencies.

The role of hospitalists has evolved over the years and is still evolving. It should be no surprise if, in the future, we work alongside a digital hospitalist twin to provide better and more personalized care to our patients. Change is uncomfortable but it is inevitable. When COVID hit, we were forced to find innovative ways to deliver care to our patients. One thing is for certain: post-pandemic (AD, or After Disease) we are not going back to a Before COVID (BC) state in terms of virtual care. With the new dawn of digital era, the crucial questions to address will be: What will the future role of a hospitalist look like? How can we leverage technology and embrace our flexibility to adapt to these trends? How can we apply the lessons learned during the pandemic to propel hospital medicine into the future? And is it time to rethink our role and even reclassify ourselves – from hospitalists to Acute Care Experts (ACE) or Primary Acute Care Physicians?

Dr. Zia is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and founder of Virtual Hospitalist - a telemedicine company with a 360-degree care model for hospital patients.

References

1. www.subjectwell.com/news/data-shows-a-majority-of-patients-remain-interested-in-clinical-trials-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

2. ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/technology-innovations-and-virtual-consultations-drive-healthcare-2025/

3. www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/telemedicine-market

4. www.healthcareitnews.com/blog/frost-sullivans-top-10-predictions-healthcare-2021

5. www.uc.edu/news/articles/2021/03/virtual-medicine--new-uc-telehealth-drone-makes-house-calls.html

6. www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/smart-home-healthcare-market

People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten. – Bill Gates

The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion a series of innovations catalyzing the digital transformation of the health care landscape.

Telemedicine use exploded over the last 12 months to the point that it has almost become ubiquitous. With that, we saw a rapid proliferation of wearables and remote patient monitoring devices. Thanks to virtual care, care delivery is no longer strictly dependent on having onsite specialists, and care itself is not confined to the boundaries of hospitals or doctors’ offices anymore.

We saw the formation of the digital front door and the emergence of new virtual care sites like virtual urgent care, virtual home health, virtual office visits, virtual hospital at home that allowed clinical care to be delivered safely outside the boundaries of hospitals. Nonclinical public places like gyms, schools, and community centers were being transformed into virtual health care portals that brought care closer to the people.

Inside the hospital, we saw a fusion of traditional inpatient care and virtual care. Onsite hospital teams embraced telemedicine during the pandemic for various reasons; to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), limit exposure, boost care capacity, improve access to specialists at distant sites, and bring family memberse to “webside” who cannot be at a patient’s bedside.

In clinical trials as well, virtual care is a welcome change. According to one survey1, most trial participants favored the use of telehealth services for clinical trials, as these helped them stay engaged, compliant, monitored, and on track while remaining at home. Furthermore, we are seeing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into telehealth, whether it is to aid physicians in clinical decision-making or to generate reminders to help patients with chronic disease management. However, this integration is only beginning to scratch the surface of the combination of two technologies’ real potential.

What’s next?

Based on these trends, it should be no surprise that digital health will become a vital sign for health care organizations.

The next 12 to 24 months will set new standards for digital health and play a significant role in defining the next generation of virtual care. There are projections that global health care industry revenues will exceed $2.6 trillion by 2025, with AI and telehealth playing a prominent role in this growth.2 According to estimates, telehealth itself will be a $175 billion market by 2026 and approximately one in three patient encounters will go virtual.3,4 Moreover, virtual care will continue to make exciting transformations, helping to make quality care accessible to everyone in innovative ways. For example, the University of Cincinnati has recently developed a pilot project using a drone equipped with video technology, artificial intelligence, sensors, and first aid kits to go to hard-to-reach areas to deliver care via telemedicine.5

Smart hospitals

In coming years, we can expect the integration of AI, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) into telemedicine at lightning speed – and at a much larger scale – that will enable surgeons from different parts of the globe to perform procedures remotely and more precisely.

AI is already gaining traction in different fields within health care – whether it’s predicting length of stay in the ICU, or assisting in triage decisions, or reading radiological images, to name just a few. The Mayo Clinic is using AI and computer-aided decision-making tools to predict the risk of surgery and potential post-op complications, which could allow even better collaboration between medical and surgical teams. We hear about the “X-ray” vision offered to proceduralists using HoloLens – mixed reality smartglasses – a technology that enables them to perform procedures more precisely. Others project that there will be more sensors and voice recognition tools in the OR that will be used to gather data to develop intelligent algorithms, and to build a safety net for interventionalists that can notify them of potential hazards or accidental sterile field breaches. The insights gained will be used to create best practices and even allow some procedures to be performed outside the traditional OR setting.

Additionally, we are seeing the development of “smart” patient rooms. For example, one health system in Florida is working on deploying Amazon Alexa in 2,500 patient rooms to allow patients to connect more easily to their care team members. In the not-so-distant future, smart hospitals with smart patient rooms and smart ORs equipped with telemedicine, AI, AR, mixed reality, and computer-aided decision-making tools will no longer be an exception.

Smart homes for smart care

Smart homes with technologies like gas detectors, movement sensors, and sleep sensors will continue to evolve. According to one estimate, the global smart home health care market was $8.7 billion in 2019, and is expected to be $96.2 billion by 2030.6

Smart technologies will have applications in fall detection and prevention, evaluation of self-administration of medicine, sleep rhythm monitoring, air quality monitoring for the detection of abnormal gas levels, and identification of things like carbon monoxide poisoning or food spoilage. In coming years, expect to see more virtual medical homes and digital health care complexes. Patients, from the convenience of their homes, might be able to connect to a suite of caregivers, all working collaboratively to provide more coordinated, effective care. The “hospital at home” model that started with six hospitals has already grown to over 100 hospitals across 29 states. The shift from onsite specialists to onscreen specialists will continue, providing greater access to specialized services.

With these emerging trends, it can be anticipated that much acute care will be provided to patients outside the hospital – either under the hospital at home model, via drone technology using telemedicine, through smart devices in smart homes, or via wearables and artificial intelligence. Hence, hospitals’ configuration in the future will be much different and more compact than currently, and many hospitals will be reserved for trauma patients, casualties of natural disasters, higher acuity diseases requiring complex procedures, and other emergencies.

The role of hospitalists has evolved over the years and is still evolving. It should be no surprise if, in the future, we work alongside a digital hospitalist twin to provide better and more personalized care to our patients. Change is uncomfortable but it is inevitable. When COVID hit, we were forced to find innovative ways to deliver care to our patients. One thing is for certain: post-pandemic (AD, or After Disease) we are not going back to a Before COVID (BC) state in terms of virtual care. With the new dawn of digital era, the crucial questions to address will be: What will the future role of a hospitalist look like? How can we leverage technology and embrace our flexibility to adapt to these trends? How can we apply the lessons learned during the pandemic to propel hospital medicine into the future? And is it time to rethink our role and even reclassify ourselves – from hospitalists to Acute Care Experts (ACE) or Primary Acute Care Physicians?

Dr. Zia is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and founder of Virtual Hospitalist - a telemedicine company with a 360-degree care model for hospital patients.

References

1. www.subjectwell.com/news/data-shows-a-majority-of-patients-remain-interested-in-clinical-trials-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

2. ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/technology-innovations-and-virtual-consultations-drive-healthcare-2025/

3. www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/telemedicine-market

4. www.healthcareitnews.com/blog/frost-sullivans-top-10-predictions-healthcare-2021

5. www.uc.edu/news/articles/2021/03/virtual-medicine--new-uc-telehealth-drone-makes-house-calls.html

6. www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/smart-home-healthcare-market

People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten. – Bill Gates

The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion a series of innovations catalyzing the digital transformation of the health care landscape.

Telemedicine use exploded over the last 12 months to the point that it has almost become ubiquitous. With that, we saw a rapid proliferation of wearables and remote patient monitoring devices. Thanks to virtual care, care delivery is no longer strictly dependent on having onsite specialists, and care itself is not confined to the boundaries of hospitals or doctors’ offices anymore.

We saw the formation of the digital front door and the emergence of new virtual care sites like virtual urgent care, virtual home health, virtual office visits, virtual hospital at home that allowed clinical care to be delivered safely outside the boundaries of hospitals. Nonclinical public places like gyms, schools, and community centers were being transformed into virtual health care portals that brought care closer to the people.

Inside the hospital, we saw a fusion of traditional inpatient care and virtual care. Onsite hospital teams embraced telemedicine during the pandemic for various reasons; to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE), limit exposure, boost care capacity, improve access to specialists at distant sites, and bring family memberse to “webside” who cannot be at a patient’s bedside.

In clinical trials as well, virtual care is a welcome change. According to one survey1, most trial participants favored the use of telehealth services for clinical trials, as these helped them stay engaged, compliant, monitored, and on track while remaining at home. Furthermore, we are seeing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into telehealth, whether it is to aid physicians in clinical decision-making or to generate reminders to help patients with chronic disease management. However, this integration is only beginning to scratch the surface of the combination of two technologies’ real potential.

What’s next?

Based on these trends, it should be no surprise that digital health will become a vital sign for health care organizations.

The next 12 to 24 months will set new standards for digital health and play a significant role in defining the next generation of virtual care. There are projections that global health care industry revenues will exceed $2.6 trillion by 2025, with AI and telehealth playing a prominent role in this growth.2 According to estimates, telehealth itself will be a $175 billion market by 2026 and approximately one in three patient encounters will go virtual.3,4 Moreover, virtual care will continue to make exciting transformations, helping to make quality care accessible to everyone in innovative ways. For example, the University of Cincinnati has recently developed a pilot project using a drone equipped with video technology, artificial intelligence, sensors, and first aid kits to go to hard-to-reach areas to deliver care via telemedicine.5

Smart hospitals

In coming years, we can expect the integration of AI, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) into telemedicine at lightning speed – and at a much larger scale – that will enable surgeons from different parts of the globe to perform procedures remotely and more precisely.

AI is already gaining traction in different fields within health care – whether it’s predicting length of stay in the ICU, or assisting in triage decisions, or reading radiological images, to name just a few. The Mayo Clinic is using AI and computer-aided decision-making tools to predict the risk of surgery and potential post-op complications, which could allow even better collaboration between medical and surgical teams. We hear about the “X-ray” vision offered to proceduralists using HoloLens – mixed reality smartglasses – a technology that enables them to perform procedures more precisely. Others project that there will be more sensors and voice recognition tools in the OR that will be used to gather data to develop intelligent algorithms, and to build a safety net for interventionalists that can notify them of potential hazards or accidental sterile field breaches. The insights gained will be used to create best practices and even allow some procedures to be performed outside the traditional OR setting.

Additionally, we are seeing the development of “smart” patient rooms. For example, one health system in Florida is working on deploying Amazon Alexa in 2,500 patient rooms to allow patients to connect more easily to their care team members. In the not-so-distant future, smart hospitals with smart patient rooms and smart ORs equipped with telemedicine, AI, AR, mixed reality, and computer-aided decision-making tools will no longer be an exception.

Smart homes for smart care

Smart homes with technologies like gas detectors, movement sensors, and sleep sensors will continue to evolve. According to one estimate, the global smart home health care market was $8.7 billion in 2019, and is expected to be $96.2 billion by 2030.6

Smart technologies will have applications in fall detection and prevention, evaluation of self-administration of medicine, sleep rhythm monitoring, air quality monitoring for the detection of abnormal gas levels, and identification of things like carbon monoxide poisoning or food spoilage. In coming years, expect to see more virtual medical homes and digital health care complexes. Patients, from the convenience of their homes, might be able to connect to a suite of caregivers, all working collaboratively to provide more coordinated, effective care. The “hospital at home” model that started with six hospitals has already grown to over 100 hospitals across 29 states. The shift from onsite specialists to onscreen specialists will continue, providing greater access to specialized services.

With these emerging trends, it can be anticipated that much acute care will be provided to patients outside the hospital – either under the hospital at home model, via drone technology using telemedicine, through smart devices in smart homes, or via wearables and artificial intelligence. Hence, hospitals’ configuration in the future will be much different and more compact than currently, and many hospitals will be reserved for trauma patients, casualties of natural disasters, higher acuity diseases requiring complex procedures, and other emergencies.

The role of hospitalists has evolved over the years and is still evolving. It should be no surprise if, in the future, we work alongside a digital hospitalist twin to provide better and more personalized care to our patients. Change is uncomfortable but it is inevitable. When COVID hit, we were forced to find innovative ways to deliver care to our patients. One thing is for certain: post-pandemic (AD, or After Disease) we are not going back to a Before COVID (BC) state in terms of virtual care. With the new dawn of digital era, the crucial questions to address will be: What will the future role of a hospitalist look like? How can we leverage technology and embrace our flexibility to adapt to these trends? How can we apply the lessons learned during the pandemic to propel hospital medicine into the future? And is it time to rethink our role and even reclassify ourselves – from hospitalists to Acute Care Experts (ACE) or Primary Acute Care Physicians?

Dr. Zia is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and founder of Virtual Hospitalist - a telemedicine company with a 360-degree care model for hospital patients.

References

1. www.subjectwell.com/news/data-shows-a-majority-of-patients-remain-interested-in-clinical-trials-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

2. ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/technology-innovations-and-virtual-consultations-drive-healthcare-2025/

3. www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/telemedicine-market

4. www.healthcareitnews.com/blog/frost-sullivans-top-10-predictions-healthcare-2021

5. www.uc.edu/news/articles/2021/03/virtual-medicine--new-uc-telehealth-drone-makes-house-calls.html

6. www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/smart-home-healthcare-market

Vaccine mandates, passports, and Kant

Houston Methodist Hospital in June 2021 enforced an April mandate that all its employees, about 26,000 of them, must be vaccinated against COVID-19. In the following weeks, many other large health care systems adopted a similar employer mandate.

Compliance with Houston Methodist’s mandate has been very high at nearly 99%. There were some deferrals, mostly because of pregnancy. There were some “medical and personal” exemptions for less than 1% of employees. The reasons for those personal exemptions have not been made public. A lawsuit by 117 employees objecting to the vaccine mandate was dismissed by a federal district judge on June 12.

Objections to the vaccine mandate have rarely involved religious-based conscientious objections, which need to be accommodated differently, legally and ethically. The objections have been disagreements on the science. As a politician said decades ago: “People are entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts.” A medical institution is an excellent organization for determining the risks and benefits of vaccination. The judge dismissing the case was very critical of the characterizations used by the plaintiffs.

The vaccine mandate has strong ethical support from both the universalizability principle of Kant and a consequentialist analysis. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on May 28, 2021, released technical assistance that has generally been interpreted to support an employer’s right to set vaccine requirements. HIPAA does not forbid an employer from asking about vaccination, but the EEOC guidance reminds employers that if they do ask, employers have legal obligations to protect the health information and keep it separate from other personnel files.

In the past few years, many hospitals and clinics have adopted mandates for influenza vaccines. In many children’s hospitals staff have been required to have chicken pox vaccines (or, as in my case, titers showing immunity from the real thing – I’m old) since the early 2000s. Measles titers (again, mine were acquired naturally – I still remember the illness and recommend against that) and TB status are occasionally required for locum tenens positions. I keep copies of these labs alongside copies of my diplomas. To me, the COVID-19 mandate is not capricious.

Some people have pointed out that the COVID-19 vaccines are not fully Food and Drug Administration approved. They are used under an emergency use authorization. Any traction that distinction might have had ethically and scientifically in November 2020 has disappeared with the experience of 9 months and 300 million doses in the United States. Dr. Fauci on July 11, 2021, said: “These vaccines are as good as officially approved with all the I’s dotted and the T’s crossed.”

On July 12, 2021, French President Macron, facing a resurgence of the pandemic because of the delta variant, announced a national vaccine mandate for all health care workers. He also announced plans to require proof of vaccination (or prior disease) in order to enter amusement parks, restaurants, and other public facilities. The ethics of his plans have been debated by ethicists and politicians for months under the rubric of a “vaccine passport.” England has required proof of vaccination or a recent negative COVID-19 test before entering soccer stadiums. In the United States, some localities, particularly those where the local politicians are against the vaccine, have passed laws proscribing the creation of these passport-like restrictions. Elsewhere, many businesses have already started to exclude customers who are not vaccinated. Airlines, hotels, and cruise ships are at the forefront of this. Society has started to create consequences for not getting the vaccine. President Macron indicated that the goal was now to put restrictions on the unvaccinated rather than on everyone.

Pediatricians are experts on the importance of consequences for misbehavior and refusals. It is a frequent topic of conversation with parents of toddlers and teenagers. Consequences are ethical, just, and effective ways of promoting safe and fair behavior. At this point, the public has been educated about the disease and the vaccines. In the United States, there has been ample access to the vaccine. It is time to enforce consequences.

Daily vaccination rates in the United States have slowed to 25% of the peak rates. The reasons for hesitancy have been analyzed in many publications. Further public education hasn’t been productive, so empathic listening has been urged to overcome hesitancy. (A similar program has long been advocated to deal with hesitancy for teenage HPV vaccines.) President Biden on July 6, 2021, proposed a program of going door to door to overcome resistance.

The world is in a race between vaccines and the delta variant. The Delta variant is moving the finish line, with some French epidemiologists advising President Macron that this more contagious variant may require a 90% vaccination level to achieve herd immunity. Israel has started giving a third booster shot in select situations and Pfizer is considering the idea. I agree with providing education, using empathic listening, and improving access. Those are all reasonable, even necessary, strategies. But at this point, I anchor my suggestions with the same advice pediatricians have long given to parents. Set rules and create consequences for misbehavior.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Houston Methodist Hospital in June 2021 enforced an April mandate that all its employees, about 26,000 of them, must be vaccinated against COVID-19. In the following weeks, many other large health care systems adopted a similar employer mandate.

Compliance with Houston Methodist’s mandate has been very high at nearly 99%. There were some deferrals, mostly because of pregnancy. There were some “medical and personal” exemptions for less than 1% of employees. The reasons for those personal exemptions have not been made public. A lawsuit by 117 employees objecting to the vaccine mandate was dismissed by a federal district judge on June 12.

Objections to the vaccine mandate have rarely involved religious-based conscientious objections, which need to be accommodated differently, legally and ethically. The objections have been disagreements on the science. As a politician said decades ago: “People are entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts.” A medical institution is an excellent organization for determining the risks and benefits of vaccination. The judge dismissing the case was very critical of the characterizations used by the plaintiffs.

The vaccine mandate has strong ethical support from both the universalizability principle of Kant and a consequentialist analysis. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on May 28, 2021, released technical assistance that has generally been interpreted to support an employer’s right to set vaccine requirements. HIPAA does not forbid an employer from asking about vaccination, but the EEOC guidance reminds employers that if they do ask, employers have legal obligations to protect the health information and keep it separate from other personnel files.

In the past few years, many hospitals and clinics have adopted mandates for influenza vaccines. In many children’s hospitals staff have been required to have chicken pox vaccines (or, as in my case, titers showing immunity from the real thing – I’m old) since the early 2000s. Measles titers (again, mine were acquired naturally – I still remember the illness and recommend against that) and TB status are occasionally required for locum tenens positions. I keep copies of these labs alongside copies of my diplomas. To me, the COVID-19 mandate is not capricious.

Some people have pointed out that the COVID-19 vaccines are not fully Food and Drug Administration approved. They are used under an emergency use authorization. Any traction that distinction might have had ethically and scientifically in November 2020 has disappeared with the experience of 9 months and 300 million doses in the United States. Dr. Fauci on July 11, 2021, said: “These vaccines are as good as officially approved with all the I’s dotted and the T’s crossed.”

On July 12, 2021, French President Macron, facing a resurgence of the pandemic because of the delta variant, announced a national vaccine mandate for all health care workers. He also announced plans to require proof of vaccination (or prior disease) in order to enter amusement parks, restaurants, and other public facilities. The ethics of his plans have been debated by ethicists and politicians for months under the rubric of a “vaccine passport.” England has required proof of vaccination or a recent negative COVID-19 test before entering soccer stadiums. In the United States, some localities, particularly those where the local politicians are against the vaccine, have passed laws proscribing the creation of these passport-like restrictions. Elsewhere, many businesses have already started to exclude customers who are not vaccinated. Airlines, hotels, and cruise ships are at the forefront of this. Society has started to create consequences for not getting the vaccine. President Macron indicated that the goal was now to put restrictions on the unvaccinated rather than on everyone.

Pediatricians are experts on the importance of consequences for misbehavior and refusals. It is a frequent topic of conversation with parents of toddlers and teenagers. Consequences are ethical, just, and effective ways of promoting safe and fair behavior. At this point, the public has been educated about the disease and the vaccines. In the United States, there has been ample access to the vaccine. It is time to enforce consequences.

Daily vaccination rates in the United States have slowed to 25% of the peak rates. The reasons for hesitancy have been analyzed in many publications. Further public education hasn’t been productive, so empathic listening has been urged to overcome hesitancy. (A similar program has long been advocated to deal with hesitancy for teenage HPV vaccines.) President Biden on July 6, 2021, proposed a program of going door to door to overcome resistance.

The world is in a race between vaccines and the delta variant. The Delta variant is moving the finish line, with some French epidemiologists advising President Macron that this more contagious variant may require a 90% vaccination level to achieve herd immunity. Israel has started giving a third booster shot in select situations and Pfizer is considering the idea. I agree with providing education, using empathic listening, and improving access. Those are all reasonable, even necessary, strategies. But at this point, I anchor my suggestions with the same advice pediatricians have long given to parents. Set rules and create consequences for misbehavior.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Houston Methodist Hospital in June 2021 enforced an April mandate that all its employees, about 26,000 of them, must be vaccinated against COVID-19. In the following weeks, many other large health care systems adopted a similar employer mandate.

Compliance with Houston Methodist’s mandate has been very high at nearly 99%. There were some deferrals, mostly because of pregnancy. There were some “medical and personal” exemptions for less than 1% of employees. The reasons for those personal exemptions have not been made public. A lawsuit by 117 employees objecting to the vaccine mandate was dismissed by a federal district judge on June 12.

Objections to the vaccine mandate have rarely involved religious-based conscientious objections, which need to be accommodated differently, legally and ethically. The objections have been disagreements on the science. As a politician said decades ago: “People are entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts.” A medical institution is an excellent organization for determining the risks and benefits of vaccination. The judge dismissing the case was very critical of the characterizations used by the plaintiffs.

The vaccine mandate has strong ethical support from both the universalizability principle of Kant and a consequentialist analysis. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on May 28, 2021, released technical assistance that has generally been interpreted to support an employer’s right to set vaccine requirements. HIPAA does not forbid an employer from asking about vaccination, but the EEOC guidance reminds employers that if they do ask, employers have legal obligations to protect the health information and keep it separate from other personnel files.

In the past few years, many hospitals and clinics have adopted mandates for influenza vaccines. In many children’s hospitals staff have been required to have chicken pox vaccines (or, as in my case, titers showing immunity from the real thing – I’m old) since the early 2000s. Measles titers (again, mine were acquired naturally – I still remember the illness and recommend against that) and TB status are occasionally required for locum tenens positions. I keep copies of these labs alongside copies of my diplomas. To me, the COVID-19 mandate is not capricious.

Some people have pointed out that the COVID-19 vaccines are not fully Food and Drug Administration approved. They are used under an emergency use authorization. Any traction that distinction might have had ethically and scientifically in November 2020 has disappeared with the experience of 9 months and 300 million doses in the United States. Dr. Fauci on July 11, 2021, said: “These vaccines are as good as officially approved with all the I’s dotted and the T’s crossed.”

On July 12, 2021, French President Macron, facing a resurgence of the pandemic because of the delta variant, announced a national vaccine mandate for all health care workers. He also announced plans to require proof of vaccination (or prior disease) in order to enter amusement parks, restaurants, and other public facilities. The ethics of his plans have been debated by ethicists and politicians for months under the rubric of a “vaccine passport.” England has required proof of vaccination or a recent negative COVID-19 test before entering soccer stadiums. In the United States, some localities, particularly those where the local politicians are against the vaccine, have passed laws proscribing the creation of these passport-like restrictions. Elsewhere, many businesses have already started to exclude customers who are not vaccinated. Airlines, hotels, and cruise ships are at the forefront of this. Society has started to create consequences for not getting the vaccine. President Macron indicated that the goal was now to put restrictions on the unvaccinated rather than on everyone.

Pediatricians are experts on the importance of consequences for misbehavior and refusals. It is a frequent topic of conversation with parents of toddlers and teenagers. Consequences are ethical, just, and effective ways of promoting safe and fair behavior. At this point, the public has been educated about the disease and the vaccines. In the United States, there has been ample access to the vaccine. It is time to enforce consequences.

Daily vaccination rates in the United States have slowed to 25% of the peak rates. The reasons for hesitancy have been analyzed in many publications. Further public education hasn’t been productive, so empathic listening has been urged to overcome hesitancy. (A similar program has long been advocated to deal with hesitancy for teenage HPV vaccines.) President Biden on July 6, 2021, proposed a program of going door to door to overcome resistance.

The world is in a race between vaccines and the delta variant. The Delta variant is moving the finish line, with some French epidemiologists advising President Macron that this more contagious variant may require a 90% vaccination level to achieve herd immunity. Israel has started giving a third booster shot in select situations and Pfizer is considering the idea. I agree with providing education, using empathic listening, and improving access. Those are all reasonable, even necessary, strategies. But at this point, I anchor my suggestions with the same advice pediatricians have long given to parents. Set rules and create consequences for misbehavior.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Dogs know their humans, but humans don’t know expiration dates

An extreme price to pay for immortality

We know that men don’t live as long as women, but the reasons aren’t entirely clear. However, some New Zealand scientists have a thought on the subject, thanks to a sheep called Shrek.

The researchers were inspired by a famous old sheep who escaped captivity, but was captured 6 years later at the age of 10. The sheep then lived 6 more years, far beyond the lifespan of a normal sheep, capturing the hearts and minds of Kiwis everywhere. Look, it’s New Zealand, sheep are life, so it’s only natural the country got attached. Scientists from the University of Otago suspected that Shrek lived such a long life because he was castrated.

So they undertook a study of sheep, and lo and behold, sheep that were castrated lived significantly longer than their uncastrated kin, thanks to a slowing of their epigenetic clocks – the DNA aged noticeably slower in the castrated sheep.

Although the research can most immediately be applied to the improvement of the New Zealand sheep industry, the implication for humanity is also apparent. Want to live longer? Get rid of the testosterone. An extreme solution to be sure. As previously reported in this column, researchers wanted to torture our mouths to get us to lose weight, and now they want to castrate people for longer life. What exactly is going on down there in New Zealand?

Man’s best mind reader

There are a lot of reasons why dogs are sometimes called “man’s best friend,” but the root of it may actually have something to do with how easily we communicate with each other. Researchers dug deeper and fetched something that Fido is born with, but his wild wolf cousin isn’t.

That something is known as the “theory of mind” ability. Have you noticed that when you point and tell dogs to grab a leash or toy, they react as if they understood the language you spoke? Researchers from Duke University wondered if this ability is a canine thing or just a domesticated dog thing.

They compared 44 canine puppies and 37 wolf pups between 5 and 18 weeks old. The wolf pups were taken into human homes and raised with a great amount of human interaction, while the dog pups were left with their mothers and raised with less human interaction.

All the puppies were then put through multiple tests. In one test, they were given clues to find a treat under a bowl. In another test, a block of wood was placed next to the treat as a physical marker. During yet another test, researchers pointed to the food directly.

The researchers discovered that the dog puppies knew where the treat was every time, while their wild relatives didn’t.

“This study really solidifies the evidence that the social genius of dogs is a product of domestication,” senior author Brian Hare said in a separate statement.

The domestication hypothesis theorizes that dogs picked up the human social cues through thousands of years of interaction. The more friendly and cooperative a wolf was with humans, the more likely it was to survive and pass on those same traits and practices. Even within the study, the dog puppies were 30 times more likely to approach a stranger than were the wolf pups.

You may think your dog understands everything you say, but it’s actually body language that Fido is most fluent in.

I’m not a dentist, but I play one on TikTok

In last week’s column, it was garlic cloves up the nose to treat a cold. This week, TikTok brings us a new way to whiten teeth.

Familiar with the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser? If not, we’ll save you the trouble of Googling it: Check it out here and here.

Have you heard anything about using it to clean your teeth? No, neither did we, and we did a lot of Googling. Proctor & Gamble, which makes the Magic Eraser, goes so far as to say on the package: “Do not use on skin or other parts of the body. Using on skin will likely cause abrasions.” (The warning is actually in all caps, but we are stylistically forbidden by our editorial overlords to do that.)

But it’s magic, right? How can you not use it on your teeth? Enter TikTok. Heather Dunn posted a video in which she rubbed a bit of a Magic Eraser on her teeth – being careful to avoid her gums, because you can never be too careful – “as the product squeaked back and forth,” the Miami Herald reported. The video has almost 256,000 likes so far.

“Yeah, your teeth are white because you scrubbed all the enamel off them. So don’t do this,” Dr. Benjamin Winters, aka the Bentist, said in a YouTube video that has 105,000 likes.

In this race for common sense, common sense is losing. Please help the Bentist restore sanity to the dental world by liking his video. It would make Mr. Clean happy.

Don’t let an expiration date boss you around

Surely you’ve been there: It’s Taco Tuesday and you’re rummaging through the refrigerator to find that shredded cheese you’re sure you have. Jackpot! You find it, but realize it’s probably been in the refrigerator for a while. You open the bag, it smells and looks fine, but the expiration date was 2 days ago. Now you have a decision to make. Maybe you’ll be fine, or maybe you’ll risk food poisoning right before your brother’s wedding.

But here’s the truth: Americans throw away perfectly good food every day. The average American family throws out $1,365 to $2,275 worth of food a year, according to a 2013 study.

Truthfully, expiration dates are not for buyers, rather they’re for stores to have an idea of their stock’s freshness. Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Law School Food and Policy Clinic and lead author of the 2013 study, told Vox that manufacturers use the dates as a way of “protecting the brand” to keep consumers from eating food that’s just a little past its peak.

With approximately 40 million people in the United States concerned about where their next meal is coming from, the Vox article noted, we need to reevaluate our system. Our national misunderstanding of expiration labels is hurting both suppliers and consumers because perfectly good food is wasted.

Sure, there is always that chance that something might be a little funky after a certain amount of time, but all in all, food probably stays fresh a lot longer than we think. Don’t always judge the shredded cheese by its expiration date.

An extreme price to pay for immortality

We know that men don’t live as long as women, but the reasons aren’t entirely clear. However, some New Zealand scientists have a thought on the subject, thanks to a sheep called Shrek.

The researchers were inspired by a famous old sheep who escaped captivity, but was captured 6 years later at the age of 10. The sheep then lived 6 more years, far beyond the lifespan of a normal sheep, capturing the hearts and minds of Kiwis everywhere. Look, it’s New Zealand, sheep are life, so it’s only natural the country got attached. Scientists from the University of Otago suspected that Shrek lived such a long life because he was castrated.

So they undertook a study of sheep, and lo and behold, sheep that were castrated lived significantly longer than their uncastrated kin, thanks to a slowing of their epigenetic clocks – the DNA aged noticeably slower in the castrated sheep.

Although the research can most immediately be applied to the improvement of the New Zealand sheep industry, the implication for humanity is also apparent. Want to live longer? Get rid of the testosterone. An extreme solution to be sure. As previously reported in this column, researchers wanted to torture our mouths to get us to lose weight, and now they want to castrate people for longer life. What exactly is going on down there in New Zealand?

Man’s best mind reader

There are a lot of reasons why dogs are sometimes called “man’s best friend,” but the root of it may actually have something to do with how easily we communicate with each other. Researchers dug deeper and fetched something that Fido is born with, but his wild wolf cousin isn’t.

That something is known as the “theory of mind” ability. Have you noticed that when you point and tell dogs to grab a leash or toy, they react as if they understood the language you spoke? Researchers from Duke University wondered if this ability is a canine thing or just a domesticated dog thing.

They compared 44 canine puppies and 37 wolf pups between 5 and 18 weeks old. The wolf pups were taken into human homes and raised with a great amount of human interaction, while the dog pups were left with their mothers and raised with less human interaction.

All the puppies were then put through multiple tests. In one test, they were given clues to find a treat under a bowl. In another test, a block of wood was placed next to the treat as a physical marker. During yet another test, researchers pointed to the food directly.

The researchers discovered that the dog puppies knew where the treat was every time, while their wild relatives didn’t.

“This study really solidifies the evidence that the social genius of dogs is a product of domestication,” senior author Brian Hare said in a separate statement.

The domestication hypothesis theorizes that dogs picked up the human social cues through thousands of years of interaction. The more friendly and cooperative a wolf was with humans, the more likely it was to survive and pass on those same traits and practices. Even within the study, the dog puppies were 30 times more likely to approach a stranger than were the wolf pups.

You may think your dog understands everything you say, but it’s actually body language that Fido is most fluent in.

I’m not a dentist, but I play one on TikTok

In last week’s column, it was garlic cloves up the nose to treat a cold. This week, TikTok brings us a new way to whiten teeth.

Familiar with the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser? If not, we’ll save you the trouble of Googling it: Check it out here and here.

Have you heard anything about using it to clean your teeth? No, neither did we, and we did a lot of Googling. Proctor & Gamble, which makes the Magic Eraser, goes so far as to say on the package: “Do not use on skin or other parts of the body. Using on skin will likely cause abrasions.” (The warning is actually in all caps, but we are stylistically forbidden by our editorial overlords to do that.)

But it’s magic, right? How can you not use it on your teeth? Enter TikTok. Heather Dunn posted a video in which she rubbed a bit of a Magic Eraser on her teeth – being careful to avoid her gums, because you can never be too careful – “as the product squeaked back and forth,” the Miami Herald reported. The video has almost 256,000 likes so far.

“Yeah, your teeth are white because you scrubbed all the enamel off them. So don’t do this,” Dr. Benjamin Winters, aka the Bentist, said in a YouTube video that has 105,000 likes.

In this race for common sense, common sense is losing. Please help the Bentist restore sanity to the dental world by liking his video. It would make Mr. Clean happy.

Don’t let an expiration date boss you around

Surely you’ve been there: It’s Taco Tuesday and you’re rummaging through the refrigerator to find that shredded cheese you’re sure you have. Jackpot! You find it, but realize it’s probably been in the refrigerator for a while. You open the bag, it smells and looks fine, but the expiration date was 2 days ago. Now you have a decision to make. Maybe you’ll be fine, or maybe you’ll risk food poisoning right before your brother’s wedding.

But here’s the truth: Americans throw away perfectly good food every day. The average American family throws out $1,365 to $2,275 worth of food a year, according to a 2013 study.

Truthfully, expiration dates are not for buyers, rather they’re for stores to have an idea of their stock’s freshness. Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Law School Food and Policy Clinic and lead author of the 2013 study, told Vox that manufacturers use the dates as a way of “protecting the brand” to keep consumers from eating food that’s just a little past its peak.

With approximately 40 million people in the United States concerned about where their next meal is coming from, the Vox article noted, we need to reevaluate our system. Our national misunderstanding of expiration labels is hurting both suppliers and consumers because perfectly good food is wasted.

Sure, there is always that chance that something might be a little funky after a certain amount of time, but all in all, food probably stays fresh a lot longer than we think. Don’t always judge the shredded cheese by its expiration date.

An extreme price to pay for immortality

We know that men don’t live as long as women, but the reasons aren’t entirely clear. However, some New Zealand scientists have a thought on the subject, thanks to a sheep called Shrek.

The researchers were inspired by a famous old sheep who escaped captivity, but was captured 6 years later at the age of 10. The sheep then lived 6 more years, far beyond the lifespan of a normal sheep, capturing the hearts and minds of Kiwis everywhere. Look, it’s New Zealand, sheep are life, so it’s only natural the country got attached. Scientists from the University of Otago suspected that Shrek lived such a long life because he was castrated.

So they undertook a study of sheep, and lo and behold, sheep that were castrated lived significantly longer than their uncastrated kin, thanks to a slowing of their epigenetic clocks – the DNA aged noticeably slower in the castrated sheep.

Although the research can most immediately be applied to the improvement of the New Zealand sheep industry, the implication for humanity is also apparent. Want to live longer? Get rid of the testosterone. An extreme solution to be sure. As previously reported in this column, researchers wanted to torture our mouths to get us to lose weight, and now they want to castrate people for longer life. What exactly is going on down there in New Zealand?

Man’s best mind reader

There are a lot of reasons why dogs are sometimes called “man’s best friend,” but the root of it may actually have something to do with how easily we communicate with each other. Researchers dug deeper and fetched something that Fido is born with, but his wild wolf cousin isn’t.

That something is known as the “theory of mind” ability. Have you noticed that when you point and tell dogs to grab a leash or toy, they react as if they understood the language you spoke? Researchers from Duke University wondered if this ability is a canine thing or just a domesticated dog thing.

They compared 44 canine puppies and 37 wolf pups between 5 and 18 weeks old. The wolf pups were taken into human homes and raised with a great amount of human interaction, while the dog pups were left with their mothers and raised with less human interaction.

All the puppies were then put through multiple tests. In one test, they were given clues to find a treat under a bowl. In another test, a block of wood was placed next to the treat as a physical marker. During yet another test, researchers pointed to the food directly.

The researchers discovered that the dog puppies knew where the treat was every time, while their wild relatives didn’t.

“This study really solidifies the evidence that the social genius of dogs is a product of domestication,” senior author Brian Hare said in a separate statement.

The domestication hypothesis theorizes that dogs picked up the human social cues through thousands of years of interaction. The more friendly and cooperative a wolf was with humans, the more likely it was to survive and pass on those same traits and practices. Even within the study, the dog puppies were 30 times more likely to approach a stranger than were the wolf pups.

You may think your dog understands everything you say, but it’s actually body language that Fido is most fluent in.

I’m not a dentist, but I play one on TikTok

In last week’s column, it was garlic cloves up the nose to treat a cold. This week, TikTok brings us a new way to whiten teeth.

Familiar with the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser? If not, we’ll save you the trouble of Googling it: Check it out here and here.

Have you heard anything about using it to clean your teeth? No, neither did we, and we did a lot of Googling. Proctor & Gamble, which makes the Magic Eraser, goes so far as to say on the package: “Do not use on skin or other parts of the body. Using on skin will likely cause abrasions.” (The warning is actually in all caps, but we are stylistically forbidden by our editorial overlords to do that.)

But it’s magic, right? How can you not use it on your teeth? Enter TikTok. Heather Dunn posted a video in which she rubbed a bit of a Magic Eraser on her teeth – being careful to avoid her gums, because you can never be too careful – “as the product squeaked back and forth,” the Miami Herald reported. The video has almost 256,000 likes so far.

“Yeah, your teeth are white because you scrubbed all the enamel off them. So don’t do this,” Dr. Benjamin Winters, aka the Bentist, said in a YouTube video that has 105,000 likes.

In this race for common sense, common sense is losing. Please help the Bentist restore sanity to the dental world by liking his video. It would make Mr. Clean happy.

Don’t let an expiration date boss you around

Surely you’ve been there: It’s Taco Tuesday and you’re rummaging through the refrigerator to find that shredded cheese you’re sure you have. Jackpot! You find it, but realize it’s probably been in the refrigerator for a while. You open the bag, it smells and looks fine, but the expiration date was 2 days ago. Now you have a decision to make. Maybe you’ll be fine, or maybe you’ll risk food poisoning right before your brother’s wedding.

But here’s the truth: Americans throw away perfectly good food every day. The average American family throws out $1,365 to $2,275 worth of food a year, according to a 2013 study.

Truthfully, expiration dates are not for buyers, rather they’re for stores to have an idea of their stock’s freshness. Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Law School Food and Policy Clinic and lead author of the 2013 study, told Vox that manufacturers use the dates as a way of “protecting the brand” to keep consumers from eating food that’s just a little past its peak.

With approximately 40 million people in the United States concerned about where their next meal is coming from, the Vox article noted, we need to reevaluate our system. Our national misunderstanding of expiration labels is hurting both suppliers and consumers because perfectly good food is wasted.

Sure, there is always that chance that something might be a little funky after a certain amount of time, but all in all, food probably stays fresh a lot longer than we think. Don’t always judge the shredded cheese by its expiration date.

Denial or a call to action?

Now that everyone in my family has been vaccinated, we’re starting to do more.

Last week we met my mom and some of her (vaccinated) friends for dinner at a local restaurant. Except for picking up takeout, I hadn’t been to one since early March 2020.

During the usual chatting about jobs, music, my kids, and trips we were thinking about, one of her friends suddenly said: “That’s funny.”

I asked him what was funny, and he said: “My left vision suddenly went dark.”

It only takes a fraction of a second to shift into doctor mode. I asked a few pointed questions and did a quick neuroscan for asymmetries, slurred speech, the things that, after 23 years, have become second nature.

It resolved after about 30 seconds. He clearly didn’t think it was anything to be alarmed about. He’s intelligent and well educated, but not a doctor. I wasn’t going to let it go, and quietly spoke to him a short while later. He may not be my patient, but pushing him in the needed direction is the right thing to do.

I’ve gotten him to the right doctors now, and the ball is rolling, but I keep thinking about it. If I hadn’t been there it’s likely nothing would have been done. In fact, he seemed to think it was more amusing than potentially serious.

Medical blogs and doctors’ lounge stories are full of similar anecdotes, where we wonder why people don’t take such things seriously. We tend to view such people as stupid and/or ignorant.

Yet, this gentleman is neither. I’ve known him since childhood. He’s smart, well educated, and well read. He’s not a medical person, though.

In reality, I don’t think doctors or nurses are any better. I suspect that’s more human nature, which is hard to override regardless of training.

But maybe it’s time to start giving these people, like my family friend, a pass, with the realization that denial and different training are part of being human, and not something to be poked fun at.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Now that everyone in my family has been vaccinated, we’re starting to do more.

Last week we met my mom and some of her (vaccinated) friends for dinner at a local restaurant. Except for picking up takeout, I hadn’t been to one since early March 2020.

During the usual chatting about jobs, music, my kids, and trips we were thinking about, one of her friends suddenly said: “That’s funny.”

I asked him what was funny, and he said: “My left vision suddenly went dark.”

It only takes a fraction of a second to shift into doctor mode. I asked a few pointed questions and did a quick neuroscan for asymmetries, slurred speech, the things that, after 23 years, have become second nature.

It resolved after about 30 seconds. He clearly didn’t think it was anything to be alarmed about. He’s intelligent and well educated, but not a doctor. I wasn’t going to let it go, and quietly spoke to him a short while later. He may not be my patient, but pushing him in the needed direction is the right thing to do.

I’ve gotten him to the right doctors now, and the ball is rolling, but I keep thinking about it. If I hadn’t been there it’s likely nothing would have been done. In fact, he seemed to think it was more amusing than potentially serious.

Medical blogs and doctors’ lounge stories are full of similar anecdotes, where we wonder why people don’t take such things seriously. We tend to view such people as stupid and/or ignorant.

Yet, this gentleman is neither. I’ve known him since childhood. He’s smart, well educated, and well read. He’s not a medical person, though.

In reality, I don’t think doctors or nurses are any better. I suspect that’s more human nature, which is hard to override regardless of training.

But maybe it’s time to start giving these people, like my family friend, a pass, with the realization that denial and different training are part of being human, and not something to be poked fun at.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Now that everyone in my family has been vaccinated, we’re starting to do more.

Last week we met my mom and some of her (vaccinated) friends for dinner at a local restaurant. Except for picking up takeout, I hadn’t been to one since early March 2020.

During the usual chatting about jobs, music, my kids, and trips we were thinking about, one of her friends suddenly said: “That’s funny.”

I asked him what was funny, and he said: “My left vision suddenly went dark.”

It only takes a fraction of a second to shift into doctor mode. I asked a few pointed questions and did a quick neuroscan for asymmetries, slurred speech, the things that, after 23 years, have become second nature.

It resolved after about 30 seconds. He clearly didn’t think it was anything to be alarmed about. He’s intelligent and well educated, but not a doctor. I wasn’t going to let it go, and quietly spoke to him a short while later. He may not be my patient, but pushing him in the needed direction is the right thing to do.

I’ve gotten him to the right doctors now, and the ball is rolling, but I keep thinking about it. If I hadn’t been there it’s likely nothing would have been done. In fact, he seemed to think it was more amusing than potentially serious.

Medical blogs and doctors’ lounge stories are full of similar anecdotes, where we wonder why people don’t take such things seriously. We tend to view such people as stupid and/or ignorant.

Yet, this gentleman is neither. I’ve known him since childhood. He’s smart, well educated, and well read. He’s not a medical person, though.

In reality, I don’t think doctors or nurses are any better. I suspect that’s more human nature, which is hard to override regardless of training.

But maybe it’s time to start giving these people, like my family friend, a pass, with the realization that denial and different training are part of being human, and not something to be poked fun at.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Are there some things we might want to keep from the COVID experience?

As your patients return to your offices for annual exams and sports physicals before the school year starts, everyone will still be processing the challenges, losses, and grief that have marked end of the COVID experience. There will be questions about the safety of vaccines for younger children, whether foreign travel is now a reasonable option, and about how best to help children – school age and teenagers, vulnerable and secure – get their footing socially and academically in the new school year. But dig a little, and you may hear about the silver linings of this past year: children who enjoyed having more time with their parents, parents who were with their families rather than in a car commuting for hours a day or traveling many days a month, grocery deliveries that eased the parent’s workload, adolescents who were able to pull back from overscheduled days, and opportunities for calm conversations that occurred quite naturally during nightly family dinners. Office visits present a dual opportunity to review – what were the psychological costs of COVID and what were positive personal and family adaptations to COVID they may want to continue as the pandemic ends?

Family dinner: Whether because sports practice was suspended, schooling was virtual, or working was at home, many families returned to eating dinner together during the pandemic year. Nightly dinners are a simple but powerful routine allowing all members of a family to reconnect and recharge together, and they are often the first things to disappear in the face of school, sports, and work demands. Research over the past several decades has demonstrated that regular family dinners are associated with better academic performance and higher self-esteem in children. They are also associated with lower rates of depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, and pregnancy in adolescents. Finally, they are associated with better cardiovascular health and lower rates of obesity in both youth and parents. The response is dose dependent, with more regular dinners leading to better outcomes. The food can be simple, what matters most is that the tone is warm, sharing, and curious, not rigid and controlling. Families can be an essential source of support as they help put events and feelings into context, giving them meaning or a framework based on the parents’ past, values, or perspective and on the family’s cultural history. Everyone benefits as family members cope with small and large setbacks, share values, and celebrate one another’s small and large successes. The return of the family dinner table, as often as is reasonable, is one “consequence” of COVID that families should try to preserve.

Consistent virtual family visits: Many families managed the cancellation of holiday visits or supported elderly relatives by connecting with family virtually. For some families, a weekly Zoom call came to function like a weekly family dinner with cousins and grandparents. Not only do these regular video calls protect elderly relatives from loneliness and isolation, but they also made it very easy for extended families to stay connected. Children cannot have too many caring adults around them, and regular calls mean that aunts, uncles, and grandparents can be an enthusiastic audience for their achievements and can offer perspective and guidance when needed. Staying connected without having to manage hours of travel makes it easy to build and maintain these family connections, creating bonds that will be deeper and stronger. Like family dinner, regular virtual gatherings with extended family are unequivocally beneficial for younger and older children and a valuable legacy of COVID.

Lowering the pressure: Many children struggled to stay engaged with virtual school and deeply missed time with friends or in activities like woodshop, soccer, or theater. But many other children had a chance to slow down from a relentless schedule of school, homework, sports, clubs, music lessons, tutoring, and on and on. For these children, many of whom are intensely ambitious and were not willing to voluntarily give up any activities, the forced slowdown of COVID has offered a new perspective on how they might manage their time. The COVID slowdown shone a light on the value of spending enough time in an activity to really learn it, and then choosing which activities to continue to explore and master, while opening time to explore new activities. There was also more time for “senseless fun,” activities that do not lead to achievement or recognition, but are simply fun, e.g., playing video games, splashing in a pool, or surfing the web. This process is critical to healthy development in early and later adolescence, and for many driven teenagers, it has been replaced by a tightly packed schedule of activities they felt they “should” be doing. If these young people hear from you that not only does the COVID pace feel better, but it can also contribute to better health and more meaningful learning and engagement, they may adopt a more thoughtful and intentional approach to managing their most precious asset – their time. Your discussion about prioritizing healthy exercise, virtual visits with friends, hobbies, or even senseless fun might reset the pressure gauge from high to moderate.

Homework help: Many children (and teenagers) found that their parents became an important source of academic support during the year of virtual school. While few parents welcomed the chance to master calculus, it is powerful for parents to know what their children are facing at school and for children to know that their parents are available to help them when they face a challenge. When parents can bear uncertainty, frustration, and even failure alongside their children, they help their children to cultivate tenacity and resilience, whether or not they can help them with a chemistry problem. Some parents will have special skills like knowing a language, being a good writer, or an academic expertise related to their work. But what matters more is working out how to help, not pressure or argue – how to share knowledge in a pleasurable manner. While it is important for children to have access to teachers and tutors with the knowledge and skills to help them learn specific subjects, the positive presence and involvement of their parents can make a valuable contribution to their psychological and educational development.

New ritual: Over the past 16 months, families found many creative ways to pass time together, from evening walks to reading aloud, listening to music, and even mastering new card games. The family evenings of a century earlier, when family members listened together to radio programs, practiced music, or played board games, seemed to have returned. While everyone could still escape to their own space to be on a screen activity alone, solitary computer time was leavened by collective time. Families may have rediscovered joy in shared recreation, exploration, or diversion. This kind of family time is a reward in itself, but it also deepens a child’s connections to everyone in their family. Such time provides lessons in how to turn boredom into something meaningful and even fun. COVID forced families inward and gave them more time. There were many costs including illness, deaths of friends and relatives, loss of time with peers, missed activities and milestones, and an impaired education. However, many of the coerced adaptations had a silver lining or unanticipated benefit. Keeping some of those benefits post COVID could enhance the lives of every member of the family.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

As your patients return to your offices for annual exams and sports physicals before the school year starts, everyone will still be processing the challenges, losses, and grief that have marked end of the COVID experience. There will be questions about the safety of vaccines for younger children, whether foreign travel is now a reasonable option, and about how best to help children – school age and teenagers, vulnerable and secure – get their footing socially and academically in the new school year. But dig a little, and you may hear about the silver linings of this past year: children who enjoyed having more time with their parents, parents who were with their families rather than in a car commuting for hours a day or traveling many days a month, grocery deliveries that eased the parent’s workload, adolescents who were able to pull back from overscheduled days, and opportunities for calm conversations that occurred quite naturally during nightly family dinners. Office visits present a dual opportunity to review – what were the psychological costs of COVID and what were positive personal and family adaptations to COVID they may want to continue as the pandemic ends?

Family dinner: Whether because sports practice was suspended, schooling was virtual, or working was at home, many families returned to eating dinner together during the pandemic year. Nightly dinners are a simple but powerful routine allowing all members of a family to reconnect and recharge together, and they are often the first things to disappear in the face of school, sports, and work demands. Research over the past several decades has demonstrated that regular family dinners are associated with better academic performance and higher self-esteem in children. They are also associated with lower rates of depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, and pregnancy in adolescents. Finally, they are associated with better cardiovascular health and lower rates of obesity in both youth and parents. The response is dose dependent, with more regular dinners leading to better outcomes. The food can be simple, what matters most is that the tone is warm, sharing, and curious, not rigid and controlling. Families can be an essential source of support as they help put events and feelings into context, giving them meaning or a framework based on the parents’ past, values, or perspective and on the family’s cultural history. Everyone benefits as family members cope with small and large setbacks, share values, and celebrate one another’s small and large successes. The return of the family dinner table, as often as is reasonable, is one “consequence” of COVID that families should try to preserve.

Consistent virtual family visits: Many families managed the cancellation of holiday visits or supported elderly relatives by connecting with family virtually. For some families, a weekly Zoom call came to function like a weekly family dinner with cousins and grandparents. Not only do these regular video calls protect elderly relatives from loneliness and isolation, but they also made it very easy for extended families to stay connected. Children cannot have too many caring adults around them, and regular calls mean that aunts, uncles, and grandparents can be an enthusiastic audience for their achievements and can offer perspective and guidance when needed. Staying connected without having to manage hours of travel makes it easy to build and maintain these family connections, creating bonds that will be deeper and stronger. Like family dinner, regular virtual gatherings with extended family are unequivocally beneficial for younger and older children and a valuable legacy of COVID.