User login

My palliative care rotation: Lessons of gratitude, mindfulness, and kindness

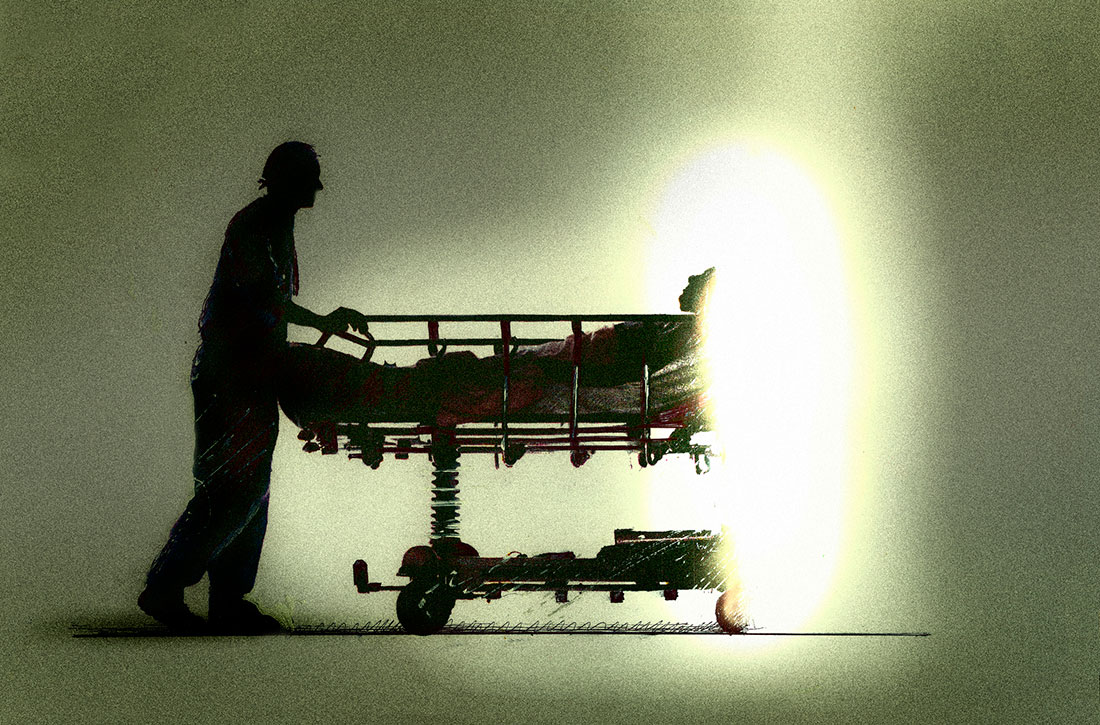

As a psychiatry resident and as a part of consultation-liaison service, I have visited many palliative care patients to assist other physicians in managing psychiatric issues such as depression, anxiety, or delirium. But recently, as the first resident from our Department of Psychiatry who was sent to a palliative care rotation, I followed these patients as a part of a primary palliative care team. Doing so allowed me to see patients from the other side of the bridge.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the suffering and stress of a patient’s illness, with the primary goal of improving the quality of life of the patient and their families. The palliative care team works in collaboration with the patient’s other clinicians to provide an extra layer of support. They provide biopsychosociocultural interventions that are in harmony with the needs of the patient rather than the prognosis of the illness. To do so, they first must evaluate the needs of the patient and their family. This is a time-consuming, energy-consuming, emotionally draining job.

During my palliative care rotation, I attended table rounds, bedside rounds, family meetings, long counseling sessions, and disposition planning meetings. This rotation also gave me the opportunity to place my feet in the shoes of a palliative care team and to reflect on how it feels to be the physician of a patient who is dying, which as a psychiatric resident I had seldom experienced. I learned that although working with patients who are dying can cause stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue, it also helps physicians appreciate the little things in life. To appreciate all the blessings we have that we usually take for granted. To practice gratitude. To be kind.

Upon reflection, I learned that the rounds of palliative care are actually mindfulness-based discussions that provide cushions of supportive work, facilitate feelings of being in control, tend to alleviate physical as well as mental suffering, foster clear-sighted hope, and assist in establishing small, subjectively significant, realistic goals for the patient’s immediate future, and to help the patient achieve these goals.

A valuable lesson from a patient

I want to highlight a case of a 65-year-old woman I first visited while I was shadowing my attending, who had been providing palliative care to the patient and her family for several months. The patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital because cancer had invaded her small bowel and caused mechanical obstruction, resulting in intractable vomiting, abdominal distension, and anorexia. She underwent open laparotomy and ileostomy for symptomatic relief. A nasogastric tube was placed, and she was put on total parenteral nutrition. The day I met her was her third postoperative day. She had been improving significantly, and she wanted to eat. She was missing food. Most of the discussion in the round among my attending, the patient, and her family was centered around how to get to the point where she would be able to eat again and appreciate the taste of biryani.

What my attending did was incredible. After assessing the patient’s needs, he instilled a realistic hope: the hope of tasting food again. The attending, while acknowledging the patient’s apprehensions, respectfully and supportively kept her from wandering into the future, made every possible attempt to bring her attention back to the present moment, and helped her establish goals for the present and her immediate future. My attending was not toxic-positive, forcing his patient to uselessly revisit her current trauma. Instead, he was kind, empathic, and considerate. His primary focus was to understand rather than to be understood, to help her find meaning, and to improve her quality of life—a quality she defined for herself, which was to taste the food of her choice.

That day, when I returned to my working station in the psychiatry ward and had lunch in the break room, I thought, “When I eat, how often do I think about eating?” Mostly I either think about work, tasks, and presentations, or I scroll on social media.

Our taste buds indeed get adapted to repetitive stimulation, but the experience of eating our favorite dish is the naked truth of being alive, and is something that I have been taking for granted for a long time. These are little things in life that I need to appreciate, and learn to cultivate their power.

As a psychiatry resident and as a part of consultation-liaison service, I have visited many palliative care patients to assist other physicians in managing psychiatric issues such as depression, anxiety, or delirium. But recently, as the first resident from our Department of Psychiatry who was sent to a palliative care rotation, I followed these patients as a part of a primary palliative care team. Doing so allowed me to see patients from the other side of the bridge.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the suffering and stress of a patient’s illness, with the primary goal of improving the quality of life of the patient and their families. The palliative care team works in collaboration with the patient’s other clinicians to provide an extra layer of support. They provide biopsychosociocultural interventions that are in harmony with the needs of the patient rather than the prognosis of the illness. To do so, they first must evaluate the needs of the patient and their family. This is a time-consuming, energy-consuming, emotionally draining job.

During my palliative care rotation, I attended table rounds, bedside rounds, family meetings, long counseling sessions, and disposition planning meetings. This rotation also gave me the opportunity to place my feet in the shoes of a palliative care team and to reflect on how it feels to be the physician of a patient who is dying, which as a psychiatric resident I had seldom experienced. I learned that although working with patients who are dying can cause stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue, it also helps physicians appreciate the little things in life. To appreciate all the blessings we have that we usually take for granted. To practice gratitude. To be kind.

Upon reflection, I learned that the rounds of palliative care are actually mindfulness-based discussions that provide cushions of supportive work, facilitate feelings of being in control, tend to alleviate physical as well as mental suffering, foster clear-sighted hope, and assist in establishing small, subjectively significant, realistic goals for the patient’s immediate future, and to help the patient achieve these goals.

A valuable lesson from a patient

I want to highlight a case of a 65-year-old woman I first visited while I was shadowing my attending, who had been providing palliative care to the patient and her family for several months. The patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital because cancer had invaded her small bowel and caused mechanical obstruction, resulting in intractable vomiting, abdominal distension, and anorexia. She underwent open laparotomy and ileostomy for symptomatic relief. A nasogastric tube was placed, and she was put on total parenteral nutrition. The day I met her was her third postoperative day. She had been improving significantly, and she wanted to eat. She was missing food. Most of the discussion in the round among my attending, the patient, and her family was centered around how to get to the point where she would be able to eat again and appreciate the taste of biryani.

What my attending did was incredible. After assessing the patient’s needs, he instilled a realistic hope: the hope of tasting food again. The attending, while acknowledging the patient’s apprehensions, respectfully and supportively kept her from wandering into the future, made every possible attempt to bring her attention back to the present moment, and helped her establish goals for the present and her immediate future. My attending was not toxic-positive, forcing his patient to uselessly revisit her current trauma. Instead, he was kind, empathic, and considerate. His primary focus was to understand rather than to be understood, to help her find meaning, and to improve her quality of life—a quality she defined for herself, which was to taste the food of her choice.

That day, when I returned to my working station in the psychiatry ward and had lunch in the break room, I thought, “When I eat, how often do I think about eating?” Mostly I either think about work, tasks, and presentations, or I scroll on social media.

Our taste buds indeed get adapted to repetitive stimulation, but the experience of eating our favorite dish is the naked truth of being alive, and is something that I have been taking for granted for a long time. These are little things in life that I need to appreciate, and learn to cultivate their power.

As a psychiatry resident and as a part of consultation-liaison service, I have visited many palliative care patients to assist other physicians in managing psychiatric issues such as depression, anxiety, or delirium. But recently, as the first resident from our Department of Psychiatry who was sent to a palliative care rotation, I followed these patients as a part of a primary palliative care team. Doing so allowed me to see patients from the other side of the bridge.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the suffering and stress of a patient’s illness, with the primary goal of improving the quality of life of the patient and their families. The palliative care team works in collaboration with the patient’s other clinicians to provide an extra layer of support. They provide biopsychosociocultural interventions that are in harmony with the needs of the patient rather than the prognosis of the illness. To do so, they first must evaluate the needs of the patient and their family. This is a time-consuming, energy-consuming, emotionally draining job.

During my palliative care rotation, I attended table rounds, bedside rounds, family meetings, long counseling sessions, and disposition planning meetings. This rotation also gave me the opportunity to place my feet in the shoes of a palliative care team and to reflect on how it feels to be the physician of a patient who is dying, which as a psychiatric resident I had seldom experienced. I learned that although working with patients who are dying can cause stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue, it also helps physicians appreciate the little things in life. To appreciate all the blessings we have that we usually take for granted. To practice gratitude. To be kind.

Upon reflection, I learned that the rounds of palliative care are actually mindfulness-based discussions that provide cushions of supportive work, facilitate feelings of being in control, tend to alleviate physical as well as mental suffering, foster clear-sighted hope, and assist in establishing small, subjectively significant, realistic goals for the patient’s immediate future, and to help the patient achieve these goals.

A valuable lesson from a patient

I want to highlight a case of a 65-year-old woman I first visited while I was shadowing my attending, who had been providing palliative care to the patient and her family for several months. The patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital because cancer had invaded her small bowel and caused mechanical obstruction, resulting in intractable vomiting, abdominal distension, and anorexia. She underwent open laparotomy and ileostomy for symptomatic relief. A nasogastric tube was placed, and she was put on total parenteral nutrition. The day I met her was her third postoperative day. She had been improving significantly, and she wanted to eat. She was missing food. Most of the discussion in the round among my attending, the patient, and her family was centered around how to get to the point where she would be able to eat again and appreciate the taste of biryani.

What my attending did was incredible. After assessing the patient’s needs, he instilled a realistic hope: the hope of tasting food again. The attending, while acknowledging the patient’s apprehensions, respectfully and supportively kept her from wandering into the future, made every possible attempt to bring her attention back to the present moment, and helped her establish goals for the present and her immediate future. My attending was not toxic-positive, forcing his patient to uselessly revisit her current trauma. Instead, he was kind, empathic, and considerate. His primary focus was to understand rather than to be understood, to help her find meaning, and to improve her quality of life—a quality she defined for herself, which was to taste the food of her choice.

That day, when I returned to my working station in the psychiatry ward and had lunch in the break room, I thought, “When I eat, how often do I think about eating?” Mostly I either think about work, tasks, and presentations, or I scroll on social media.

Our taste buds indeed get adapted to repetitive stimulation, but the experience of eating our favorite dish is the naked truth of being alive, and is something that I have been taking for granted for a long time. These are little things in life that I need to appreciate, and learn to cultivate their power.

I Never Wanted To Be a Hero

I have been in the business of medicine for more than 15 years and I will never forget the initial surge of the COVID-19 pandemic in Massachusetts.

As a hospitalist, I admitted patients infected with COVID-19, followed them on the floor, and, since I had some experience working in an intensive care unit (ICU), was assigned to cover a “COVID ICU.” This wing of the hospital used to be a fancy orthopedic floor that our institution was lucky enough to have. So began the most life-changing experience in my career as a physician.

In this role, we witness death more than any of us would care to discuss. It comes with the territory, and we never expected this to change once COVID hit. However, so many patients succumbed to this disease, especially during the first surge, which made it difficult to handle emotionally. Patients that fell ill initially stayed isolated at home, optimistic they would turn the corner only to enter the hospital a week later after their conditioned worsened. After requiring a couple of liters of supplemental oxygen in the emergency room, they eventually ended up on a high flow nasal cannula in just a matter of hours.

Patients slowly got sicker and felt more helpless as the days passed, leading us to prescribe drugs that eventually proved to have no benefit. We checked countless inflammatory markers, most of which we were not even sure what to do with. Many times, we hosted a family meeting via FaceTime, holding a patient’s hand in one hand and an iPad in the other to discuss goals of care. Too often, a dark cloud hung over these discussions, a realization that there was not much else we could do.

I have always felt that helping someone have a decent and peaceful death is important, especially when the prognosis is grim, and that patient is suffering. But the sheer number of times this happened during the initial surge of the pandemic was difficult to handle. It felt like I had more of those discussions in 3 months than I did during my entire career as a hospitalist.

We helped plenty of people get better, with some heading home in a week. They thanked us, painted rocks and the sidewalks in front of the hospital displaying messages of gratitude, and sent lunches. Others, though, left the hospital 2 months later with a tube in their stomach so they could receive some form of nutrition and another in their neck to help them breathe.

These struggles were by no means special to me; other hospitalists around the world faced similar situations at one point or another during the pandemic. Working overtime, coming home late, exhausted, undressing in the garage, trying to be there for my 3 kids who were full of energy after a whole day of Zoom and doing the usual kid stuff. My house used to have strict rules about screen time. No more.

The summer months provided a bit of a COVID break, with only 1 or 2 infected patients entering my care. We went to outdoor restaurants and tried to get our lives back to “normal.” As the weather turned cold, however, things went south again. This time no more hydroxychloroquine, a drug used to fight malaria but also treat other autoimmune diseases, as it was proven eventually over many studies that it is not helpful and was potentially harmful. We instead shifted our focus to remdesivir—an antiviral drug that displayed some benefits—tocilizumab, and dexamethasone, anti-inflammatory drugs with the latter providing some positive outcomes on mortality.

Patient survival rates improved slightly, likely due to a combination of factors. We were more experienced at fighting the disease, which led to things in the hospital not being as chaotic and more time available to spend with the patients. Personal protective equipment (PPE) and tests were more readily available, and the population getting hit by the disease changed slightly with fewer elderly people from nursing homes falling ill because of social distancing, other safety measures, or having already fought the disease. Our attention turned instead to more young people that had returned to work and their social lives.

The arrival of the vaccines brought considerable relief. I remember a few decades ago debating and sometimes fighting with friends and family over who was better: Iron Man or Spider-Man. Now I found myself having the same conversation about the Pfizer and Moderna COVID vaccines.

Summer 2021 holds significantly more promise. Most of the adult population is getting vaccinated, and I am very hopeful that we are approaching the end of this nightmare. In June, our office received word that we could remove our masks if we were fully vaccinated. It felt weird, but represented another sign that things are improving. I took my kids to the mall and removed my mask. It felt odd considering how that little blue thing became part of me during the pandemic. It also felt strange to not prescribe a single dose of remdesivir for an entire month.

It feels good—and normal—to care for the patients that we neglected for a year. It has been a needed boost to see patients return to their health care providers for their colonoscopy screenings, mammograms, and managing chronic problems like coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or receiving chemotherapy.

I learned plenty from this pandemic and hope I am not alone. I learned to be humble. We started with a drug that was harmful, moved on to a drug that is probably neutral and eventually were able to come up with a drug that seems to decrease mortality at least in some COVID patients. I learned it is fine to try new therapies based on the best data in the hope they result in positive clinical outcomes. However, it is critical that we all keep an eye on the rapidly evolving literature and adjust our behavior accordingly.

I also learned, or relearned, that if people are desperate enough, they will drink bleach to see if it works. Others are convinced that the purpose of vaccination is to inject a microchip allowing ourselves to be tracked by some higher power. I learned that we must take the first step to prepare for the next pandemic by having a decent reserve of PPE.

It is clear synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) technology is here to stay, and I believe it has a huge potential to change many areas of medicine. mRNA vaccines proved to be much faster to develop and probably much easier to change as the pathogen, in this case coronavirus, changes.

The technology could be used against a variety of infectious diseases to make vaccines against malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, or hepatitis. It can also be very useful for faster vaccine development needed in future possible pandemics such as influenza, Ebola, or severe acute respiratory syndrome. It may also be used for cancer treatment.

As John P. Cooke, MD, PhD, the medical director for the Center of RNA Therapeutics Program at the Houston Methodist Research Institute, said, “Most vaccines today are still viral vaccines – they are inactivated virus, so it’s potentially infectious and you have to have virus on hand. With mRNA, you’re just writing code which is going to tell the cell to make a viral protein – one part of a viral protein to stimulate an immune response. And, here’s the wonderful thing, you don’t even need the virus in hand, just its DNA code.”1

Corresponding author: Dragos Vesbianu, MD, Attending Hospitalist, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, 2014 Washington St, Newton, MA 02462; dragosv@yahoo.com.

Financial dislosures: None.

1. Houston Methodist. Messenger RNA – the Therapy of the Future. Newswise. November 16, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/messenger-rna-the-therapy-of-the-future/

I have been in the business of medicine for more than 15 years and I will never forget the initial surge of the COVID-19 pandemic in Massachusetts.

As a hospitalist, I admitted patients infected with COVID-19, followed them on the floor, and, since I had some experience working in an intensive care unit (ICU), was assigned to cover a “COVID ICU.” This wing of the hospital used to be a fancy orthopedic floor that our institution was lucky enough to have. So began the most life-changing experience in my career as a physician.

In this role, we witness death more than any of us would care to discuss. It comes with the territory, and we never expected this to change once COVID hit. However, so many patients succumbed to this disease, especially during the first surge, which made it difficult to handle emotionally. Patients that fell ill initially stayed isolated at home, optimistic they would turn the corner only to enter the hospital a week later after their conditioned worsened. After requiring a couple of liters of supplemental oxygen in the emergency room, they eventually ended up on a high flow nasal cannula in just a matter of hours.

Patients slowly got sicker and felt more helpless as the days passed, leading us to prescribe drugs that eventually proved to have no benefit. We checked countless inflammatory markers, most of which we were not even sure what to do with. Many times, we hosted a family meeting via FaceTime, holding a patient’s hand in one hand and an iPad in the other to discuss goals of care. Too often, a dark cloud hung over these discussions, a realization that there was not much else we could do.

I have always felt that helping someone have a decent and peaceful death is important, especially when the prognosis is grim, and that patient is suffering. But the sheer number of times this happened during the initial surge of the pandemic was difficult to handle. It felt like I had more of those discussions in 3 months than I did during my entire career as a hospitalist.

We helped plenty of people get better, with some heading home in a week. They thanked us, painted rocks and the sidewalks in front of the hospital displaying messages of gratitude, and sent lunches. Others, though, left the hospital 2 months later with a tube in their stomach so they could receive some form of nutrition and another in their neck to help them breathe.

These struggles were by no means special to me; other hospitalists around the world faced similar situations at one point or another during the pandemic. Working overtime, coming home late, exhausted, undressing in the garage, trying to be there for my 3 kids who were full of energy after a whole day of Zoom and doing the usual kid stuff. My house used to have strict rules about screen time. No more.

The summer months provided a bit of a COVID break, with only 1 or 2 infected patients entering my care. We went to outdoor restaurants and tried to get our lives back to “normal.” As the weather turned cold, however, things went south again. This time no more hydroxychloroquine, a drug used to fight malaria but also treat other autoimmune diseases, as it was proven eventually over many studies that it is not helpful and was potentially harmful. We instead shifted our focus to remdesivir—an antiviral drug that displayed some benefits—tocilizumab, and dexamethasone, anti-inflammatory drugs with the latter providing some positive outcomes on mortality.

Patient survival rates improved slightly, likely due to a combination of factors. We were more experienced at fighting the disease, which led to things in the hospital not being as chaotic and more time available to spend with the patients. Personal protective equipment (PPE) and tests were more readily available, and the population getting hit by the disease changed slightly with fewer elderly people from nursing homes falling ill because of social distancing, other safety measures, or having already fought the disease. Our attention turned instead to more young people that had returned to work and their social lives.

The arrival of the vaccines brought considerable relief. I remember a few decades ago debating and sometimes fighting with friends and family over who was better: Iron Man or Spider-Man. Now I found myself having the same conversation about the Pfizer and Moderna COVID vaccines.

Summer 2021 holds significantly more promise. Most of the adult population is getting vaccinated, and I am very hopeful that we are approaching the end of this nightmare. In June, our office received word that we could remove our masks if we were fully vaccinated. It felt weird, but represented another sign that things are improving. I took my kids to the mall and removed my mask. It felt odd considering how that little blue thing became part of me during the pandemic. It also felt strange to not prescribe a single dose of remdesivir for an entire month.

It feels good—and normal—to care for the patients that we neglected for a year. It has been a needed boost to see patients return to their health care providers for their colonoscopy screenings, mammograms, and managing chronic problems like coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or receiving chemotherapy.

I learned plenty from this pandemic and hope I am not alone. I learned to be humble. We started with a drug that was harmful, moved on to a drug that is probably neutral and eventually were able to come up with a drug that seems to decrease mortality at least in some COVID patients. I learned it is fine to try new therapies based on the best data in the hope they result in positive clinical outcomes. However, it is critical that we all keep an eye on the rapidly evolving literature and adjust our behavior accordingly.

I also learned, or relearned, that if people are desperate enough, they will drink bleach to see if it works. Others are convinced that the purpose of vaccination is to inject a microchip allowing ourselves to be tracked by some higher power. I learned that we must take the first step to prepare for the next pandemic by having a decent reserve of PPE.

It is clear synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) technology is here to stay, and I believe it has a huge potential to change many areas of medicine. mRNA vaccines proved to be much faster to develop and probably much easier to change as the pathogen, in this case coronavirus, changes.

The technology could be used against a variety of infectious diseases to make vaccines against malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, or hepatitis. It can also be very useful for faster vaccine development needed in future possible pandemics such as influenza, Ebola, or severe acute respiratory syndrome. It may also be used for cancer treatment.

As John P. Cooke, MD, PhD, the medical director for the Center of RNA Therapeutics Program at the Houston Methodist Research Institute, said, “Most vaccines today are still viral vaccines – they are inactivated virus, so it’s potentially infectious and you have to have virus on hand. With mRNA, you’re just writing code which is going to tell the cell to make a viral protein – one part of a viral protein to stimulate an immune response. And, here’s the wonderful thing, you don’t even need the virus in hand, just its DNA code.”1

Corresponding author: Dragos Vesbianu, MD, Attending Hospitalist, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, 2014 Washington St, Newton, MA 02462; dragosv@yahoo.com.

Financial dislosures: None.

I have been in the business of medicine for more than 15 years and I will never forget the initial surge of the COVID-19 pandemic in Massachusetts.

As a hospitalist, I admitted patients infected with COVID-19, followed them on the floor, and, since I had some experience working in an intensive care unit (ICU), was assigned to cover a “COVID ICU.” This wing of the hospital used to be a fancy orthopedic floor that our institution was lucky enough to have. So began the most life-changing experience in my career as a physician.

In this role, we witness death more than any of us would care to discuss. It comes with the territory, and we never expected this to change once COVID hit. However, so many patients succumbed to this disease, especially during the first surge, which made it difficult to handle emotionally. Patients that fell ill initially stayed isolated at home, optimistic they would turn the corner only to enter the hospital a week later after their conditioned worsened. After requiring a couple of liters of supplemental oxygen in the emergency room, they eventually ended up on a high flow nasal cannula in just a matter of hours.

Patients slowly got sicker and felt more helpless as the days passed, leading us to prescribe drugs that eventually proved to have no benefit. We checked countless inflammatory markers, most of which we were not even sure what to do with. Many times, we hosted a family meeting via FaceTime, holding a patient’s hand in one hand and an iPad in the other to discuss goals of care. Too often, a dark cloud hung over these discussions, a realization that there was not much else we could do.

I have always felt that helping someone have a decent and peaceful death is important, especially when the prognosis is grim, and that patient is suffering. But the sheer number of times this happened during the initial surge of the pandemic was difficult to handle. It felt like I had more of those discussions in 3 months than I did during my entire career as a hospitalist.

We helped plenty of people get better, with some heading home in a week. They thanked us, painted rocks and the sidewalks in front of the hospital displaying messages of gratitude, and sent lunches. Others, though, left the hospital 2 months later with a tube in their stomach so they could receive some form of nutrition and another in their neck to help them breathe.

These struggles were by no means special to me; other hospitalists around the world faced similar situations at one point or another during the pandemic. Working overtime, coming home late, exhausted, undressing in the garage, trying to be there for my 3 kids who were full of energy after a whole day of Zoom and doing the usual kid stuff. My house used to have strict rules about screen time. No more.

The summer months provided a bit of a COVID break, with only 1 or 2 infected patients entering my care. We went to outdoor restaurants and tried to get our lives back to “normal.” As the weather turned cold, however, things went south again. This time no more hydroxychloroquine, a drug used to fight malaria but also treat other autoimmune diseases, as it was proven eventually over many studies that it is not helpful and was potentially harmful. We instead shifted our focus to remdesivir—an antiviral drug that displayed some benefits—tocilizumab, and dexamethasone, anti-inflammatory drugs with the latter providing some positive outcomes on mortality.

Patient survival rates improved slightly, likely due to a combination of factors. We were more experienced at fighting the disease, which led to things in the hospital not being as chaotic and more time available to spend with the patients. Personal protective equipment (PPE) and tests were more readily available, and the population getting hit by the disease changed slightly with fewer elderly people from nursing homes falling ill because of social distancing, other safety measures, or having already fought the disease. Our attention turned instead to more young people that had returned to work and their social lives.

The arrival of the vaccines brought considerable relief. I remember a few decades ago debating and sometimes fighting with friends and family over who was better: Iron Man or Spider-Man. Now I found myself having the same conversation about the Pfizer and Moderna COVID vaccines.

Summer 2021 holds significantly more promise. Most of the adult population is getting vaccinated, and I am very hopeful that we are approaching the end of this nightmare. In June, our office received word that we could remove our masks if we were fully vaccinated. It felt weird, but represented another sign that things are improving. I took my kids to the mall and removed my mask. It felt odd considering how that little blue thing became part of me during the pandemic. It also felt strange to not prescribe a single dose of remdesivir for an entire month.

It feels good—and normal—to care for the patients that we neglected for a year. It has been a needed boost to see patients return to their health care providers for their colonoscopy screenings, mammograms, and managing chronic problems like coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or receiving chemotherapy.

I learned plenty from this pandemic and hope I am not alone. I learned to be humble. We started with a drug that was harmful, moved on to a drug that is probably neutral and eventually were able to come up with a drug that seems to decrease mortality at least in some COVID patients. I learned it is fine to try new therapies based on the best data in the hope they result in positive clinical outcomes. However, it is critical that we all keep an eye on the rapidly evolving literature and adjust our behavior accordingly.

I also learned, or relearned, that if people are desperate enough, they will drink bleach to see if it works. Others are convinced that the purpose of vaccination is to inject a microchip allowing ourselves to be tracked by some higher power. I learned that we must take the first step to prepare for the next pandemic by having a decent reserve of PPE.

It is clear synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) technology is here to stay, and I believe it has a huge potential to change many areas of medicine. mRNA vaccines proved to be much faster to develop and probably much easier to change as the pathogen, in this case coronavirus, changes.

The technology could be used against a variety of infectious diseases to make vaccines against malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, or hepatitis. It can also be very useful for faster vaccine development needed in future possible pandemics such as influenza, Ebola, or severe acute respiratory syndrome. It may also be used for cancer treatment.

As John P. Cooke, MD, PhD, the medical director for the Center of RNA Therapeutics Program at the Houston Methodist Research Institute, said, “Most vaccines today are still viral vaccines – they are inactivated virus, so it’s potentially infectious and you have to have virus on hand. With mRNA, you’re just writing code which is going to tell the cell to make a viral protein – one part of a viral protein to stimulate an immune response. And, here’s the wonderful thing, you don’t even need the virus in hand, just its DNA code.”1

Corresponding author: Dragos Vesbianu, MD, Attending Hospitalist, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, 2014 Washington St, Newton, MA 02462; dragosv@yahoo.com.

Financial dislosures: None.

1. Houston Methodist. Messenger RNA – the Therapy of the Future. Newswise. November 16, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/messenger-rna-the-therapy-of-the-future/

1. Houston Methodist. Messenger RNA – the Therapy of the Future. Newswise. November 16, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/messenger-rna-the-therapy-of-the-future/

Nowhere to run and nowhere to hide

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Advice on biopsies, workups, and referrals

Over the next 2 months we will dedicate this column to some general tips and pearls from the perspective of a gynecologic oncologist to guide general obstetrician gynecologists in the workup and management of preinvasive or invasive gynecologic diseases. The goal of these recommendations is to minimize misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis and avoid unnecessary or untimely referrals.

Perform biopsy, not Pap smears, on visible cervical and vaginal lesions

The purpose of the Pap smear is to screen asymptomatic patients for cervical dysplasia or microscopic invasive disease. Cytology is an unreliable diagnostic tool for visible, symptomatic lesions in large part because of sampling errors, and the lack of architectural information in cytologic versus histopathologic specimens. Invasive lesions can be mischaracterized as preinvasive on a Pap smear. This can result in delayed diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic procedures. For example, if a visible, abnormal-appearing, cervical lesion is seen during a routine visit and a Pap smear is performed (rather than a biopsy of the mass), the patient may receive an incorrect preliminary diagnosis of “high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ” as it can be difficult to distinguish invasive carcinoma from carcinoma in situ on cytology. If the patient and provider do not understand the limitations of Pap smears in diagnosing invasive cancers, they may be falsely reassured and possibly delay or abstain from follow-up for an excisional procedure. If she does return for the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), there might still be unnecessary delays in making referrals and definitive treatment while waiting for results. Radical hysterectomy may not promptly follow because, if performed within 6 weeks of an excisional procedure, it is associated with a significantly higher risk for perioperative complication, and therefore, if the excisional procedure was unnecessary to begin with, there may be additional time lost that need not be.1

Some clinicians avoid biopsy of visible lesions because they are concerned about bleeding complications that might arise in the office. Straightforward strategies to control bleeding are readily available in most gynecology offices, especially those already equipped for procedures such as LEEP and colposcopy. Prior to performing the biopsy, clinicians should ensure that they have supplies such as gauze sponges and ring forceps or packing forceps, silver nitrate, and ferric subsulfate solution (“Monsel’s solution”) close at hand. In the vast majority of cases, direct pressure for 5 minutes with gauze sponges and ferric subsulfate is highly effective at resolving most bleeding from a cervical or vaginal biopsy site. If this does not bring hemostasis, cautery devices or suture can be employed. If all else fails, be prepared to place vaginal packing (always with the insertion of a urinary Foley catheter to prevent urinary retention). In my experience, this is rarely needed.

Wherever possible, visible cervical or vaginal (or vulvar, see below) lesions should be biopsied for histopathology, sampling representative areas of the most concerning portion, in order to minimize misdiagnosis and expedite referral and definitive treatment. For necrotic-appearing lesions I recommend taking multiple samples of the tumor, as necrotic, nonviable tissue can prevent accurate diagnosis of a cancer. In general, Pap smears should be reserved as screening tests for asymptomatic women without visible pathology.

Don’t treat or refer low-grade dysplasia, even if persistent

Increasingly we are understanding that low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract (CIN I, VAIN I, VIN I) is less a precursor for cancer, and more a phenomenon of benign HPV-associated changes.2 This HPV change may be chronically persistent, may require years of observation and serial Pap smears, and may be a general nuisance for the patient. However, current guidelines do not recommend intervention for low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract.2 Interventions to resect these lesions can result in morbidity, including perineal pain, vaginal scarring, and cervical stenosis or insufficiency. Given the extremely low risk for progression to cancer, these morbidities do not outweigh any small potential benefit.

When I am conferring with patients who have chronic low-grade dysplasia I spend a great deal of time exploring their understanding of the diagnosis and its pathophysiology, their fears, and their expectation regarding “success” of treatment. I spend the time educating them that this is a sequela of chronic viral infection that will not be eradicated with local surgical excisions, that their cancer risk and need for surveillance would persist even if surgical intervention were offered, and that the side effects of treatment would outweigh any benefit from the small risk of cancer or high-grade dysplasia.

In summary, the treatment of choice for persistent low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract is comprehensive patient education, not surgical resection or referral to gynecologic oncology.

Repeat sampling if there’s a discordance between imaging and biopsy results

Delay in cancer diagnosis is one of the greatest concerns for front-line gynecology providers. One of the more modifiable strategies to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis is to ensure that there is concordance between clinical findings and testing results. Otherwise said: The results and findings should make sense in aggregate. An example was cited above in which a visible cervical mass demonstrated CIN III on cytologic testing. Another common example is a biopsy result of “scant benign endometrium” in a patient with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrial stripe on ultrasound. In both of these cases there is clear discordance between physical findings and the results of pathology sampling. A pathology report, in all of its black and white certitude, seems like the most reliable source of information. However, always trust your clinical judgment. If the clinical picture is suggesting something far worse than these limited, often random or blind samplings, I recommend repeated or more extensive sampling (for example, dilation and curettage). At the very least, schedule close follow-up with repeated sampling if the symptom or finding persists. The emphasis here is on scheduled follow-up, rather than “p.r.n.,” because a patient who was given a “normal” pathology result to explain her abnormal symptoms may not volunteer that those symptoms are persistent as she may feel that anything sinister was already ruled out. Make certain that you explain the potential for misdiagnosis as the reason for why you would like to see her back shortly to ensure the issue has resolved.

Biopsy vulvar lesions, minimize empiric treatment

Vulvar cancer is notoriously associated with delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for gynecologic oncologists to see women who have vulvar cancers that have been empirically treated, sometimes for months or years, with steroids or other topical agents. If a lesion on the vulva is characteristically benign in appearance (such as condyloma or lichen sclerosis), it may be reasonable to start empiric treatment. However, all patients who are treated without biopsy should be rescheduled for a planned follow-up appointment in 2-3 months. If the lesion/area remains unchanged, or worse, the lesion should be biopsied before proceeding with a change in therapy or continued therapy. Once again, don’t rely on patients to return for evaluation if the lesion doesn’t improve. Many patients assume that our first empiric diagnosis is “gospel,” and therefore may not return if the treatment doesn’t work. Meanwhile, providers may assume that patients will know that there is uncertainty in our interpretation and that they will know to report if the initial treatment didn’t work. These assumptions are the recipe for delayed diagnosis. If there is too great a burden on the patient to schedule a return visit because of social or financial reasons then the patient should have a biopsy prior to initiation of treatment. As a rule, empiric treatment is not a good strategy for patients without good access to follow-up.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Sullivan S. et al Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):294-8.

2. Perkins R .et al J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020 Apr;24(2):102-31.

Over the next 2 months we will dedicate this column to some general tips and pearls from the perspective of a gynecologic oncologist to guide general obstetrician gynecologists in the workup and management of preinvasive or invasive gynecologic diseases. The goal of these recommendations is to minimize misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis and avoid unnecessary or untimely referrals.

Perform biopsy, not Pap smears, on visible cervical and vaginal lesions

The purpose of the Pap smear is to screen asymptomatic patients for cervical dysplasia or microscopic invasive disease. Cytology is an unreliable diagnostic tool for visible, symptomatic lesions in large part because of sampling errors, and the lack of architectural information in cytologic versus histopathologic specimens. Invasive lesions can be mischaracterized as preinvasive on a Pap smear. This can result in delayed diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic procedures. For example, if a visible, abnormal-appearing, cervical lesion is seen during a routine visit and a Pap smear is performed (rather than a biopsy of the mass), the patient may receive an incorrect preliminary diagnosis of “high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ” as it can be difficult to distinguish invasive carcinoma from carcinoma in situ on cytology. If the patient and provider do not understand the limitations of Pap smears in diagnosing invasive cancers, they may be falsely reassured and possibly delay or abstain from follow-up for an excisional procedure. If she does return for the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), there might still be unnecessary delays in making referrals and definitive treatment while waiting for results. Radical hysterectomy may not promptly follow because, if performed within 6 weeks of an excisional procedure, it is associated with a significantly higher risk for perioperative complication, and therefore, if the excisional procedure was unnecessary to begin with, there may be additional time lost that need not be.1

Some clinicians avoid biopsy of visible lesions because they are concerned about bleeding complications that might arise in the office. Straightforward strategies to control bleeding are readily available in most gynecology offices, especially those already equipped for procedures such as LEEP and colposcopy. Prior to performing the biopsy, clinicians should ensure that they have supplies such as gauze sponges and ring forceps or packing forceps, silver nitrate, and ferric subsulfate solution (“Monsel’s solution”) close at hand. In the vast majority of cases, direct pressure for 5 minutes with gauze sponges and ferric subsulfate is highly effective at resolving most bleeding from a cervical or vaginal biopsy site. If this does not bring hemostasis, cautery devices or suture can be employed. If all else fails, be prepared to place vaginal packing (always with the insertion of a urinary Foley catheter to prevent urinary retention). In my experience, this is rarely needed.

Wherever possible, visible cervical or vaginal (or vulvar, see below) lesions should be biopsied for histopathology, sampling representative areas of the most concerning portion, in order to minimize misdiagnosis and expedite referral and definitive treatment. For necrotic-appearing lesions I recommend taking multiple samples of the tumor, as necrotic, nonviable tissue can prevent accurate diagnosis of a cancer. In general, Pap smears should be reserved as screening tests for asymptomatic women without visible pathology.

Don’t treat or refer low-grade dysplasia, even if persistent

Increasingly we are understanding that low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract (CIN I, VAIN I, VIN I) is less a precursor for cancer, and more a phenomenon of benign HPV-associated changes.2 This HPV change may be chronically persistent, may require years of observation and serial Pap smears, and may be a general nuisance for the patient. However, current guidelines do not recommend intervention for low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract.2 Interventions to resect these lesions can result in morbidity, including perineal pain, vaginal scarring, and cervical stenosis or insufficiency. Given the extremely low risk for progression to cancer, these morbidities do not outweigh any small potential benefit.

When I am conferring with patients who have chronic low-grade dysplasia I spend a great deal of time exploring their understanding of the diagnosis and its pathophysiology, their fears, and their expectation regarding “success” of treatment. I spend the time educating them that this is a sequela of chronic viral infection that will not be eradicated with local surgical excisions, that their cancer risk and need for surveillance would persist even if surgical intervention were offered, and that the side effects of treatment would outweigh any benefit from the small risk of cancer or high-grade dysplasia.

In summary, the treatment of choice for persistent low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract is comprehensive patient education, not surgical resection or referral to gynecologic oncology.

Repeat sampling if there’s a discordance between imaging and biopsy results

Delay in cancer diagnosis is one of the greatest concerns for front-line gynecology providers. One of the more modifiable strategies to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis is to ensure that there is concordance between clinical findings and testing results. Otherwise said: The results and findings should make sense in aggregate. An example was cited above in which a visible cervical mass demonstrated CIN III on cytologic testing. Another common example is a biopsy result of “scant benign endometrium” in a patient with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrial stripe on ultrasound. In both of these cases there is clear discordance between physical findings and the results of pathology sampling. A pathology report, in all of its black and white certitude, seems like the most reliable source of information. However, always trust your clinical judgment. If the clinical picture is suggesting something far worse than these limited, often random or blind samplings, I recommend repeated or more extensive sampling (for example, dilation and curettage). At the very least, schedule close follow-up with repeated sampling if the symptom or finding persists. The emphasis here is on scheduled follow-up, rather than “p.r.n.,” because a patient who was given a “normal” pathology result to explain her abnormal symptoms may not volunteer that those symptoms are persistent as she may feel that anything sinister was already ruled out. Make certain that you explain the potential for misdiagnosis as the reason for why you would like to see her back shortly to ensure the issue has resolved.

Biopsy vulvar lesions, minimize empiric treatment

Vulvar cancer is notoriously associated with delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for gynecologic oncologists to see women who have vulvar cancers that have been empirically treated, sometimes for months or years, with steroids or other topical agents. If a lesion on the vulva is characteristically benign in appearance (such as condyloma or lichen sclerosis), it may be reasonable to start empiric treatment. However, all patients who are treated without biopsy should be rescheduled for a planned follow-up appointment in 2-3 months. If the lesion/area remains unchanged, or worse, the lesion should be biopsied before proceeding with a change in therapy or continued therapy. Once again, don’t rely on patients to return for evaluation if the lesion doesn’t improve. Many patients assume that our first empiric diagnosis is “gospel,” and therefore may not return if the treatment doesn’t work. Meanwhile, providers may assume that patients will know that there is uncertainty in our interpretation and that they will know to report if the initial treatment didn’t work. These assumptions are the recipe for delayed diagnosis. If there is too great a burden on the patient to schedule a return visit because of social or financial reasons then the patient should have a biopsy prior to initiation of treatment. As a rule, empiric treatment is not a good strategy for patients without good access to follow-up.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Sullivan S. et al Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):294-8.

2. Perkins R .et al J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020 Apr;24(2):102-31.

Over the next 2 months we will dedicate this column to some general tips and pearls from the perspective of a gynecologic oncologist to guide general obstetrician gynecologists in the workup and management of preinvasive or invasive gynecologic diseases. The goal of these recommendations is to minimize misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis and avoid unnecessary or untimely referrals.

Perform biopsy, not Pap smears, on visible cervical and vaginal lesions

The purpose of the Pap smear is to screen asymptomatic patients for cervical dysplasia or microscopic invasive disease. Cytology is an unreliable diagnostic tool for visible, symptomatic lesions in large part because of sampling errors, and the lack of architectural information in cytologic versus histopathologic specimens. Invasive lesions can be mischaracterized as preinvasive on a Pap smear. This can result in delayed diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic procedures. For example, if a visible, abnormal-appearing, cervical lesion is seen during a routine visit and a Pap smear is performed (rather than a biopsy of the mass), the patient may receive an incorrect preliminary diagnosis of “high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ” as it can be difficult to distinguish invasive carcinoma from carcinoma in situ on cytology. If the patient and provider do not understand the limitations of Pap smears in diagnosing invasive cancers, they may be falsely reassured and possibly delay or abstain from follow-up for an excisional procedure. If she does return for the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), there might still be unnecessary delays in making referrals and definitive treatment while waiting for results. Radical hysterectomy may not promptly follow because, if performed within 6 weeks of an excisional procedure, it is associated with a significantly higher risk for perioperative complication, and therefore, if the excisional procedure was unnecessary to begin with, there may be additional time lost that need not be.1

Some clinicians avoid biopsy of visible lesions because they are concerned about bleeding complications that might arise in the office. Straightforward strategies to control bleeding are readily available in most gynecology offices, especially those already equipped for procedures such as LEEP and colposcopy. Prior to performing the biopsy, clinicians should ensure that they have supplies such as gauze sponges and ring forceps or packing forceps, silver nitrate, and ferric subsulfate solution (“Monsel’s solution”) close at hand. In the vast majority of cases, direct pressure for 5 minutes with gauze sponges and ferric subsulfate is highly effective at resolving most bleeding from a cervical or vaginal biopsy site. If this does not bring hemostasis, cautery devices or suture can be employed. If all else fails, be prepared to place vaginal packing (always with the insertion of a urinary Foley catheter to prevent urinary retention). In my experience, this is rarely needed.

Wherever possible, visible cervical or vaginal (or vulvar, see below) lesions should be biopsied for histopathology, sampling representative areas of the most concerning portion, in order to minimize misdiagnosis and expedite referral and definitive treatment. For necrotic-appearing lesions I recommend taking multiple samples of the tumor, as necrotic, nonviable tissue can prevent accurate diagnosis of a cancer. In general, Pap smears should be reserved as screening tests for asymptomatic women without visible pathology.

Don’t treat or refer low-grade dysplasia, even if persistent

Increasingly we are understanding that low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract (CIN I, VAIN I, VIN I) is less a precursor for cancer, and more a phenomenon of benign HPV-associated changes.2 This HPV change may be chronically persistent, may require years of observation and serial Pap smears, and may be a general nuisance for the patient. However, current guidelines do not recommend intervention for low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract.2 Interventions to resect these lesions can result in morbidity, including perineal pain, vaginal scarring, and cervical stenosis or insufficiency. Given the extremely low risk for progression to cancer, these morbidities do not outweigh any small potential benefit.

When I am conferring with patients who have chronic low-grade dysplasia I spend a great deal of time exploring their understanding of the diagnosis and its pathophysiology, their fears, and their expectation regarding “success” of treatment. I spend the time educating them that this is a sequela of chronic viral infection that will not be eradicated with local surgical excisions, that their cancer risk and need for surveillance would persist even if surgical intervention were offered, and that the side effects of treatment would outweigh any benefit from the small risk of cancer or high-grade dysplasia.

In summary, the treatment of choice for persistent low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract is comprehensive patient education, not surgical resection or referral to gynecologic oncology.

Repeat sampling if there’s a discordance between imaging and biopsy results

Delay in cancer diagnosis is one of the greatest concerns for front-line gynecology providers. One of the more modifiable strategies to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis is to ensure that there is concordance between clinical findings and testing results. Otherwise said: The results and findings should make sense in aggregate. An example was cited above in which a visible cervical mass demonstrated CIN III on cytologic testing. Another common example is a biopsy result of “scant benign endometrium” in a patient with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrial stripe on ultrasound. In both of these cases there is clear discordance between physical findings and the results of pathology sampling. A pathology report, in all of its black and white certitude, seems like the most reliable source of information. However, always trust your clinical judgment. If the clinical picture is suggesting something far worse than these limited, often random or blind samplings, I recommend repeated or more extensive sampling (for example, dilation and curettage). At the very least, schedule close follow-up with repeated sampling if the symptom or finding persists. The emphasis here is on scheduled follow-up, rather than “p.r.n.,” because a patient who was given a “normal” pathology result to explain her abnormal symptoms may not volunteer that those symptoms are persistent as she may feel that anything sinister was already ruled out. Make certain that you explain the potential for misdiagnosis as the reason for why you would like to see her back shortly to ensure the issue has resolved.

Biopsy vulvar lesions, minimize empiric treatment

Vulvar cancer is notoriously associated with delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for gynecologic oncologists to see women who have vulvar cancers that have been empirically treated, sometimes for months or years, with steroids or other topical agents. If a lesion on the vulva is characteristically benign in appearance (such as condyloma or lichen sclerosis), it may be reasonable to start empiric treatment. However, all patients who are treated without biopsy should be rescheduled for a planned follow-up appointment in 2-3 months. If the lesion/area remains unchanged, or worse, the lesion should be biopsied before proceeding with a change in therapy or continued therapy. Once again, don’t rely on patients to return for evaluation if the lesion doesn’t improve. Many patients assume that our first empiric diagnosis is “gospel,” and therefore may not return if the treatment doesn’t work. Meanwhile, providers may assume that patients will know that there is uncertainty in our interpretation and that they will know to report if the initial treatment didn’t work. These assumptions are the recipe for delayed diagnosis. If there is too great a burden on the patient to schedule a return visit because of social or financial reasons then the patient should have a biopsy prior to initiation of treatment. As a rule, empiric treatment is not a good strategy for patients without good access to follow-up.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Sullivan S. et al Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):294-8.

2. Perkins R .et al J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020 Apr;24(2):102-31.

Fibroids: Is surgery the only management approach?

Two chronic gynecologic conditions notably affect a woman’s quality of life (QoL), including fertility – one is endometriosis, and the other is a fibroid uterus. For a benign tumor, fibroids have an impressive prevalence found in approximately 50%-60% of women during their reproductive years. By menopause, it is estimated that 70% of woman have a fibroid, yet the true incidence is unknown given that only 25% of women experience symptoms bothersome enough to warrant intervention. This month’s article reviews the burden of fibroids and the latest management options that may potentially avoid surgery.

Background

Fibroids are monoclonal tumors of uterine smooth muscle that originate from the myometrium. Risk factors include family history, being premenopausal, increasing time since last delivery, obesity, and hypertension (ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 228 Jun 2021: Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jun 1;137[6]:e100-e15) but oral hormonal contraception, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), and increased parity reduce the risk of fibroids. Compared with White women, Black women have a 2-3 times higher prevalence of fibroids, develop them at a younger age, and present with larger fibroids.

The FIGO leiomyoma classification is the agreed upon system for identifying fibroid location. Symptoms are all too familiar to gynecologists, with life-threatening hemorrhage with severe anemia being the most feared, particularly for FIGO types 1-5. Transvaginal ultrasound is the simplest imaging tool for evaluation.

Fibroids and fertility

Fibroids can impair fertility in several ways: alteration of local anatomy, including the detrimental effects of abnormal uterine bleeding; functional changes by increasing uterine contractions and impairing endometrium and myometrial blood supply; and changes to the local hormonal environment that could impair egg/sperm transport, or embryo implantation (Hum Reprod Update. 2017;22:665-86).

Prior to consideration of surgery, saline infusion sonogram can determine the degree of impact on the endometrium, which is most applicable to the infertility patient, but can also allow guidance toward the appropriate surgical approach.

Treatment options – medical

Management of fibroids is based on a woman’s age, desire for fertility, symptoms, and location of the fibroid(s). Expectant observation of a woman with fibroids may be a reasonable approach, provided the lack of symptoms impairing QoL and of anemia. Typically, there is no change in fibroid size during the short term, considered less than 1 year. Regarding fertility, studies are heterogeneous so there is no definitive conclusion that fibroids impair natural fertility (Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;43:100-10). Spontaneous regression, defined by a reduction in fibroid volume of greater than 20%, has been noted to occur in 7.0% of fibroids (Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2018;7[3]:117-21).

When fertility is not desired, medical management of fibroids is the initial conservative approach. GnRH agonists have been utilized for temporary relief of menometrorrhagia because of fibroids and to reduce their volume, particularly preoperatively. However, extended treatment can induce bone mineral density loss. Add-back therapy (tibolone, raloxifene, estriol, and ipriflavone) is of value in reducing bone loss while MPA and tibolone may manage vasomotor symptoms. More recently, the use of a GnRH antagonist (elagolix) along with add-back therapy has been approved for up to 24 months by the Food and Drug Administration and has demonstrated a more than 50% amenorrhea rate at 12 months (Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1313-26).

Progesterone plays an important role in fibroid growth, but the mechanism is unclear. Although not FDA approved, selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRM) act directly on fibroid size reduction at the level of the pituitary to induce amenorrhea through inhibition of ovulation. Also, more than one course of SPRMs can provide benefit for bleeding control and volume reduction. The SPRM ulipristal acetate for four courses of 3 months demonstrated 73.5% of patients experienced a fibroid volume reduction of greater than 25% and were amenorrheic (Fertil Steril. 2017;108:416-25). GnRH agonists or SPRMs may benefit women if the fibroid is larger than 3 cm or anemia exists, thereby precluding immediate surgery.