User login

Successful Targeted Therapy with Alectinib in ALK-Positive Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

Background

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates due to its typical late-stage diagnosis and subsequent limited surgical options. However, recent advances in molecular profiling offer hope for targeted therapies. We present a case of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma which progressed despite surgery and chemotherapy yet showed a positive respond to Alectinib.

Case Description

A 79-year-old male with medical history of tobacco use and ulcerative colitis presented to the clinic with 15lb unintentional weight loss over the past few months in 04/2021. Computed tomography (CT) showed dilated common bile duct due to 2.2 x 1.9 x 1.7 cm mass with no metastatic disease. Biopsy was consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient completed 6 cycles of dose-reduced neoadjuvant gemcitabine and paclitaxel in late 2021 due to his severe neuropathy and ECOG. Subsequent CT and PET-CT showed stable disease prior to undergoing pylorus-sparing pancreatoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy with portal vein resection in 05/2022 with surgical pathology grading yPT4N2cM0. The follow- up PET scan in 09/2022 revealed new pulmonary and liver metastases, along with increased uptake in the pancreatic region, suggesting recurrent disease. Next generation sequencing (NGS) identified an ELM4-ALK chromosomal rearrangement on the surgical pathology. Given the patient’s cancer progression and concerns about chemotherapy tolerance, Alectinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor more commonly used in lung cancer, was considered as a treatment option. Patient began Alectinib 10/2022 with no significant side effects and PET scan on 03/2023 and 06/2023 showing resolution of his lung nodules and liver lesions. Patient remained on Alectinib until he transitioned to hospice after an ischemic stroke in 03/2024.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer urgently requires novel therapies as about 25% of patients harbor actionable molecular alterations that have led to the success of targeted therapies. ALK fusion genes are identified in multiple cancers, but the prevalence is only 0.16% in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Alectinib provided an extended progression free survival compared with standard chemotherapy in our patient. ALK inhibitors may demonstrate a remarkable response in metastatic pancreatic cancer even in poor candidates for standard chemotherapy highlighting the emphasis of NGS and targeted therapy options for pancreatic cancer to improve survival.

Background

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates due to its typical late-stage diagnosis and subsequent limited surgical options. However, recent advances in molecular profiling offer hope for targeted therapies. We present a case of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma which progressed despite surgery and chemotherapy yet showed a positive respond to Alectinib.

Case Description

A 79-year-old male with medical history of tobacco use and ulcerative colitis presented to the clinic with 15lb unintentional weight loss over the past few months in 04/2021. Computed tomography (CT) showed dilated common bile duct due to 2.2 x 1.9 x 1.7 cm mass with no metastatic disease. Biopsy was consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient completed 6 cycles of dose-reduced neoadjuvant gemcitabine and paclitaxel in late 2021 due to his severe neuropathy and ECOG. Subsequent CT and PET-CT showed stable disease prior to undergoing pylorus-sparing pancreatoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy with portal vein resection in 05/2022 with surgical pathology grading yPT4N2cM0. The follow- up PET scan in 09/2022 revealed new pulmonary and liver metastases, along with increased uptake in the pancreatic region, suggesting recurrent disease. Next generation sequencing (NGS) identified an ELM4-ALK chromosomal rearrangement on the surgical pathology. Given the patient’s cancer progression and concerns about chemotherapy tolerance, Alectinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor more commonly used in lung cancer, was considered as a treatment option. Patient began Alectinib 10/2022 with no significant side effects and PET scan on 03/2023 and 06/2023 showing resolution of his lung nodules and liver lesions. Patient remained on Alectinib until he transitioned to hospice after an ischemic stroke in 03/2024.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer urgently requires novel therapies as about 25% of patients harbor actionable molecular alterations that have led to the success of targeted therapies. ALK fusion genes are identified in multiple cancers, but the prevalence is only 0.16% in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Alectinib provided an extended progression free survival compared with standard chemotherapy in our patient. ALK inhibitors may demonstrate a remarkable response in metastatic pancreatic cancer even in poor candidates for standard chemotherapy highlighting the emphasis of NGS and targeted therapy options for pancreatic cancer to improve survival.

Background

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates due to its typical late-stage diagnosis and subsequent limited surgical options. However, recent advances in molecular profiling offer hope for targeted therapies. We present a case of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma which progressed despite surgery and chemotherapy yet showed a positive respond to Alectinib.

Case Description

A 79-year-old male with medical history of tobacco use and ulcerative colitis presented to the clinic with 15lb unintentional weight loss over the past few months in 04/2021. Computed tomography (CT) showed dilated common bile duct due to 2.2 x 1.9 x 1.7 cm mass with no metastatic disease. Biopsy was consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient completed 6 cycles of dose-reduced neoadjuvant gemcitabine and paclitaxel in late 2021 due to his severe neuropathy and ECOG. Subsequent CT and PET-CT showed stable disease prior to undergoing pylorus-sparing pancreatoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy with portal vein resection in 05/2022 with surgical pathology grading yPT4N2cM0. The follow- up PET scan in 09/2022 revealed new pulmonary and liver metastases, along with increased uptake in the pancreatic region, suggesting recurrent disease. Next generation sequencing (NGS) identified an ELM4-ALK chromosomal rearrangement on the surgical pathology. Given the patient’s cancer progression and concerns about chemotherapy tolerance, Alectinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor more commonly used in lung cancer, was considered as a treatment option. Patient began Alectinib 10/2022 with no significant side effects and PET scan on 03/2023 and 06/2023 showing resolution of his lung nodules and liver lesions. Patient remained on Alectinib until he transitioned to hospice after an ischemic stroke in 03/2024.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer urgently requires novel therapies as about 25% of patients harbor actionable molecular alterations that have led to the success of targeted therapies. ALK fusion genes are identified in multiple cancers, but the prevalence is only 0.16% in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Alectinib provided an extended progression free survival compared with standard chemotherapy in our patient. ALK inhibitors may demonstrate a remarkable response in metastatic pancreatic cancer even in poor candidates for standard chemotherapy highlighting the emphasis of NGS and targeted therapy options for pancreatic cancer to improve survival.

VA Ann Arbor Immunotherapy Stewardship Program

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Assessing the Impact of Antidepressants on Cancer Treatment: A Retrospective Analysis of 14 Antineoplastic Agents

Assessing the Impact of Antidepressants on Cancer Treatment: A Retrospective Analysis of 14 Antineoplastic Agents

Cancer patients experience depression at rates > 5 times that of the general population.1-11 Despite an increase in palliative care use, depression rates continued to rise.2-4 Between 5% to 16% of outpatients, 4% to 14% of inpatients, and up to 49% of patients receiving palliative care experience depression.5 This issue also impacts families and caregivers.1 A 2021 meta-analysis found that 23% of active military personnel and 20% of veterans experience depression.11

Antidepressants approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) target the serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine systems and include boxed warnings about an increased risk of suicidal thoughts in adults aged 18 to 24 years.12,13 These medications are categorized into several classes: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs), norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), serotonin receptor modulators (SRMs), serotonin-melatonin receptor antagonists (SMRAs), and N—methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists (NMDARAs).14,15 The first FDA-approved antidepressants, iproniazid (an MAOI) and imipramine (a TCA) laid the foundation for the development of newer classes like SSRIs and SNRIs.15-17

Older antidepressants such as MAOIs and TCAs are used less due to their adverse effects (AEs) and drug interactions. MAOIs, such as iproniazid, selegiline, moclobemide, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and phenelzine, have numerous AEs and drug interactions, making them unsuitable for first- or second-line treatment of depression.14,18-21 TCAs such as doxepin, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, trimipramine, protriptyline, maprotiline, and amoxapine have a narrow therapeutic index requiring careful monitoring for signs of toxicity such as QRS widening, tremors, or confusion. Despite the issues, TCAs are generally classified as second-line agents for major depressive disorder (MDD). TCAs have off-label uses for migraine prophylaxis, treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), insomnia, and chronic pain management first-line.14,22-29

Newer antidepressants, including TeCAs and NDRIs, are typically more effective, but also come with safety concerns. TeCAs like mirtazapine interact with several medications, including MAOIs, serotonin-increasing drugs, alcohol, cannabidiol, and marijuana. Mirtazapine is FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in adults. It is also used off-label to treat insomnia, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), headaches, and migraines. Compared to other antidepressants, mirtazapine is effective for all stages of depression and addresses a broad range of related symptoms.14,30-34 NDRIs, such as bupropion, also interact with various medications, including MAOIs, other antidepressants, stimulants, and alcohol. Bupropion is FDA-approved for smoking cessation and to treat depression and SAD. It is also used off-label for depression- related bipolar disorder or sexual dysfunction, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and obesity.14,35-42

SSRIs, SNRIs, and SRMs should be used with caution. SSRIs such as sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine are first-line treatments for depression and various psychiatric disorders due to their safety and efficacy. Common AEs of SSRIs include sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, weight changes, and gastrointestinal (GI) issues. SSRIs can prolong the QT interval, posing a risk of life-threatening arrhythmia, and may interact with other medications, necessitating treatment adjustments. The FDA approved SSRIs for MDD, GAD, bulimia nervosa, bipolar depression, OCD, panic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and SAD. Off-label uses include binge eating disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, fibromyalgia, premature ejaculation, paraphilias, autism, Raynaud phenomenon, and vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Among SSRIs, sertraline and escitalopram are noted for their effectiveness and tolerability.14,43-53

SNRIs, including duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran, and levomilnacipran, may increase bleeding risk, especially when taken with blood thinners. They can also elevate blood pressure, which may worsen if combined with stimulants. SNRIs may interact with other medications that affect serotonin levels, increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome when taken with triptans, pain medications, or other antidepressants.14 Desvenlafaxine has been approved by the FDA (but not by the European Medicines Agency).54-56 Duloxetine is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression, neuropathic pain, anxiety disorders, fibromyalgia, and musculoskeletal disorders. It is used off-label to treat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and stress urinary incontinence.57-61 Venlafaxine is FDA-approved for depression, SAD, and panic disorder, and is prescribed off-label to treat ADHD, neuropathy, fibromyalgia, cataplexy, and PTSD, either alone or in combination with other medications.62,63 Milnacipran is not approved for MDD; levomilnacipran received approval in 2013.64

SRMs such as trazodone, nefazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine also function as serotonin reuptake inhibitors.14,15 Trazodone is FDA-approved for MDD. It has been used off-label to treat anxiety, Alzheimer disease, substance misuse, bulimia nervosa, insomnia, fibromyalgia, and PTSD when first-line SSRIs are ineffective. A notable AE of trazodone is orthostatic hypotension, which can lead to dizziness and increase the risk of falls, especially in geriatric patients.65-70 Nefazodone was discontinued in Europe in 2003 due to rare cases of liver toxicity but remains available in the US.71-74 Vilazodone and vortioxetine are FDA-approved.

The latest classes of antidepressants include SMRAs and NMDARAs.14 Agomelatine, an SMRA, was approved in Europe in 2009 but rejected by the FDA in 2011 due to liver toxicity.75 NMDARAs like esketamine and a combination of dextromethorphan and bupropion received FDA approval in 2019 and 2022, respectively.76,77

This retrospective study analyzes noncancer drugs used during systemic chemotherapy based on a dataset of 14 antineoplastic agents. It sought to identify the most dispensed noncancer drug groups, discuss findings, compare patients with and without antidepressant prescriptions, and examine trends in antidepressant use from 2002 to 2023. This analysis expands on prior research.78-81

Methods

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and ensured compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol. The Joint Pathology Center (JPC) of the US Department of Defense (DoD) Cancer Registry Program and Military Health System (MHS) data experts from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) provided data for the analysis.

Data Sources

The JPC DoD Cancer Registry Program contains data from 1998 to 2024. CAPER and PDTS are part of the MHS Data Repository/Management Analysis and Reporting Tool database. Each observation in CAPER represents an ambulatory encounter at a military treatment facility (MTF). CAPER records are available from 2003 to 2024. PDTS records are available from 2002 to 2004. Each observation in PDTS represents a prescription filled for an MHS beneficiary, excluding those filled at international civilian pharmacies and inpatient pharmacy prescriptions.

This cross-sectional analysis requested data extraction for specific cancer drugs from the DoD Cancer Registry, focusing on treatment details, diagnosis dates, patient demographics, and physicians’ comments on AEs. After identifying patients, CAPER was used to identify additional health conditions. PDTS was used to compile a list of prescription medications filled during systemic cancer treatment or < 2 years postdiagnosis.

The 2016 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Coding and Staging Manual and International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, 1st revision, were used to decode disease and cancer types.82,83 Data sorting and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel. The percentage for the total was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the subgroup divided by the total number of patients or data variables. To compare the mean number of dispensed antidepressants to those without antidepressants, a 2-tailed, 2-sample z test was used to calculate the P value and determine statistical significance (P < .05) using socscistatistics.com.

Data were extracted 3 times between 2021 and 2023. The initial 2021 protocol focused on erlotinib and gefitinib. A modified protocol in 2022 added paclitaxel, cisplatin, docetaxel, pemetrexed, and crizotinib; further modification in 2023 included 8 new antineoplastic agents and 2 anticoagulants. Sotorasib has not been prescribed in the MHS, and JPC lacks records for noncancer drugs. The 2023 dataset comprised 2210 patients with cancer treated with 14 antineoplastic agents; 2104 had documented diagnoses and 2113 had recorded prescriptions. Data for erlotinib, gefitinib, and paclitaxel have been published previously.78,79

Results

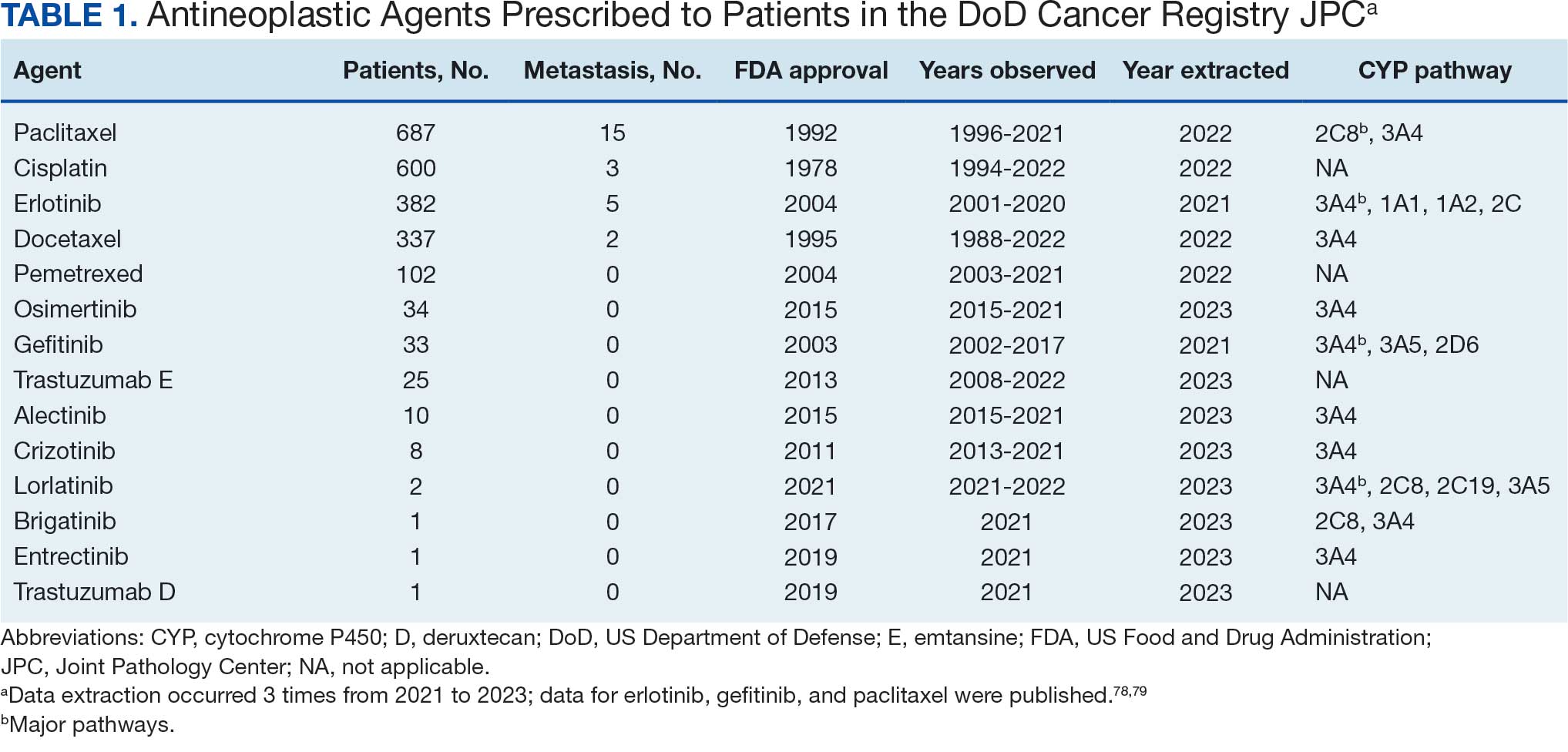

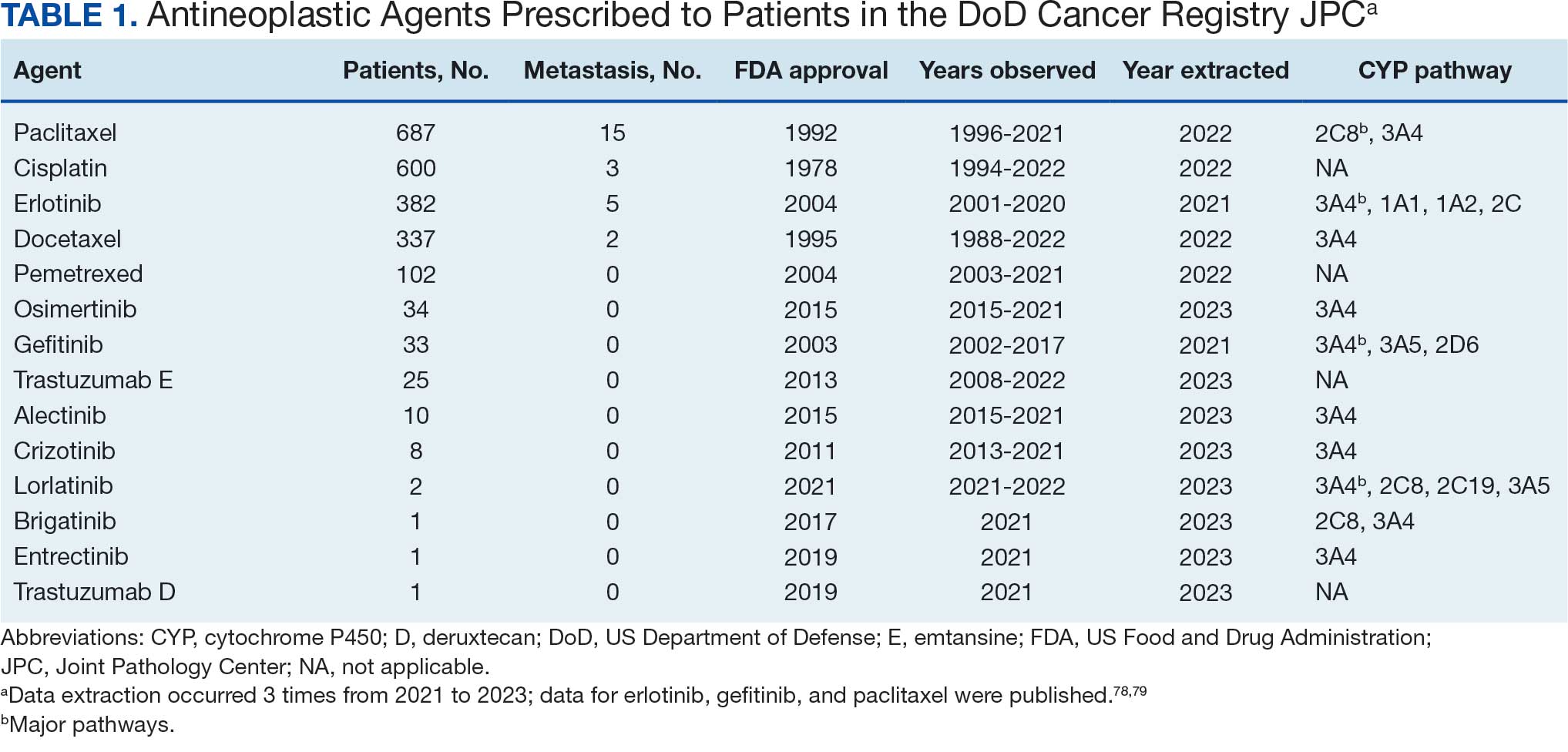

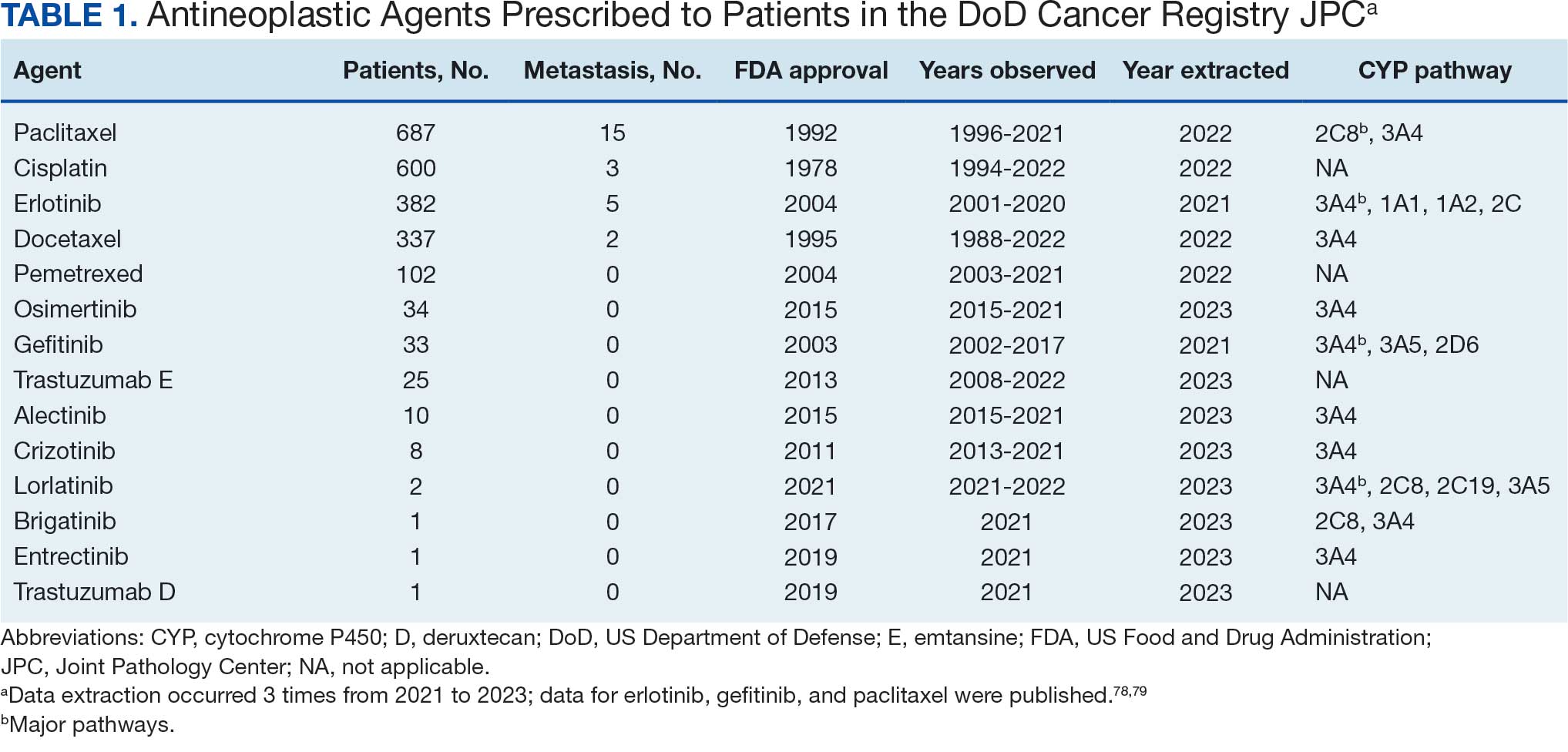

Of 2113 patients with recorded prescriptions, 1297 patients (61.4%) received 109 cancer drugs, including 96 antineoplastics, 7 disease-modifying antirheumatic agents, 4 biologic response modifiers, and 2 calcitonin gene-related peptides. Fourteen antineoplastic agents had complete data from JPC, while others were noted for combination therapies or treatment switches from the PDTS (Table 1). Seventy-six cancer drugs were prescribed with antidepressants in 489 patients (eAppendix).

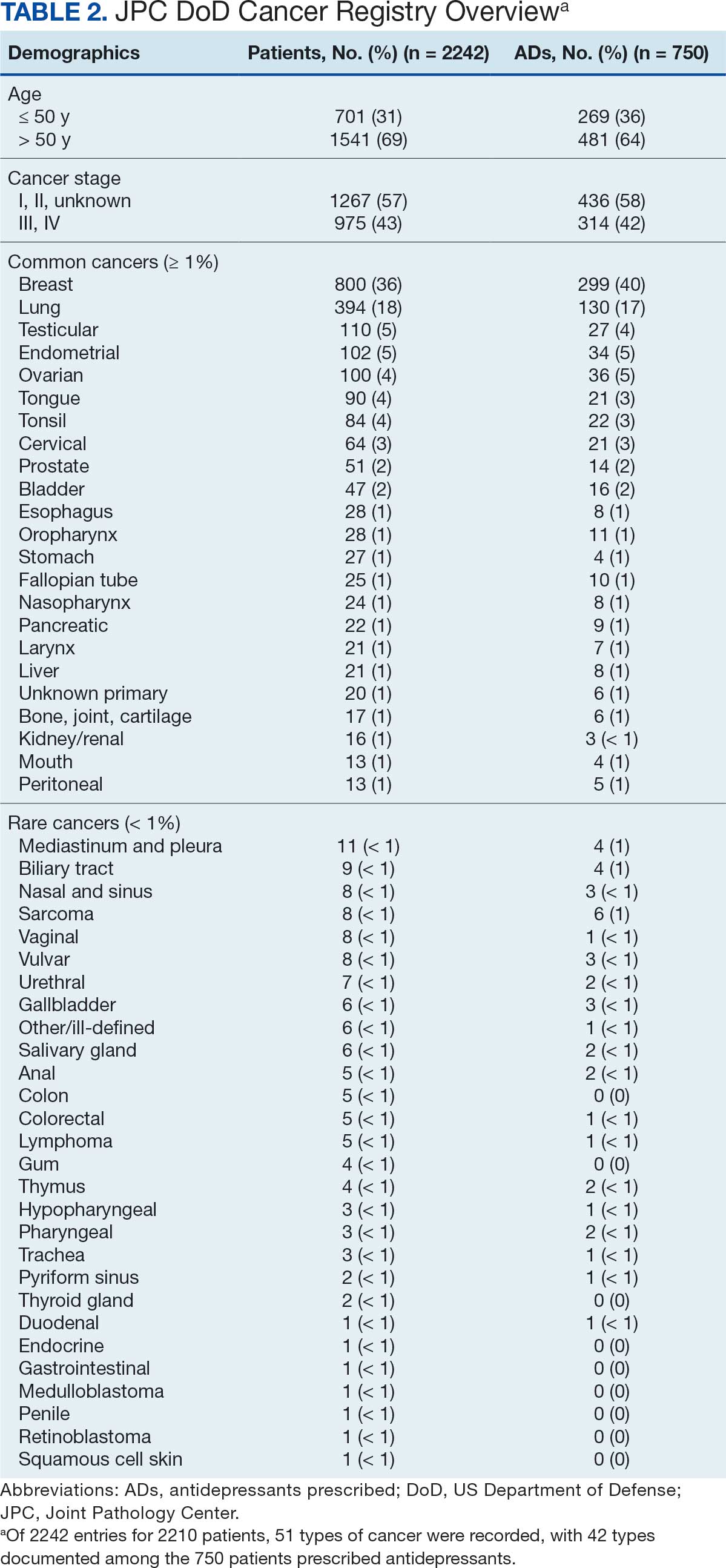

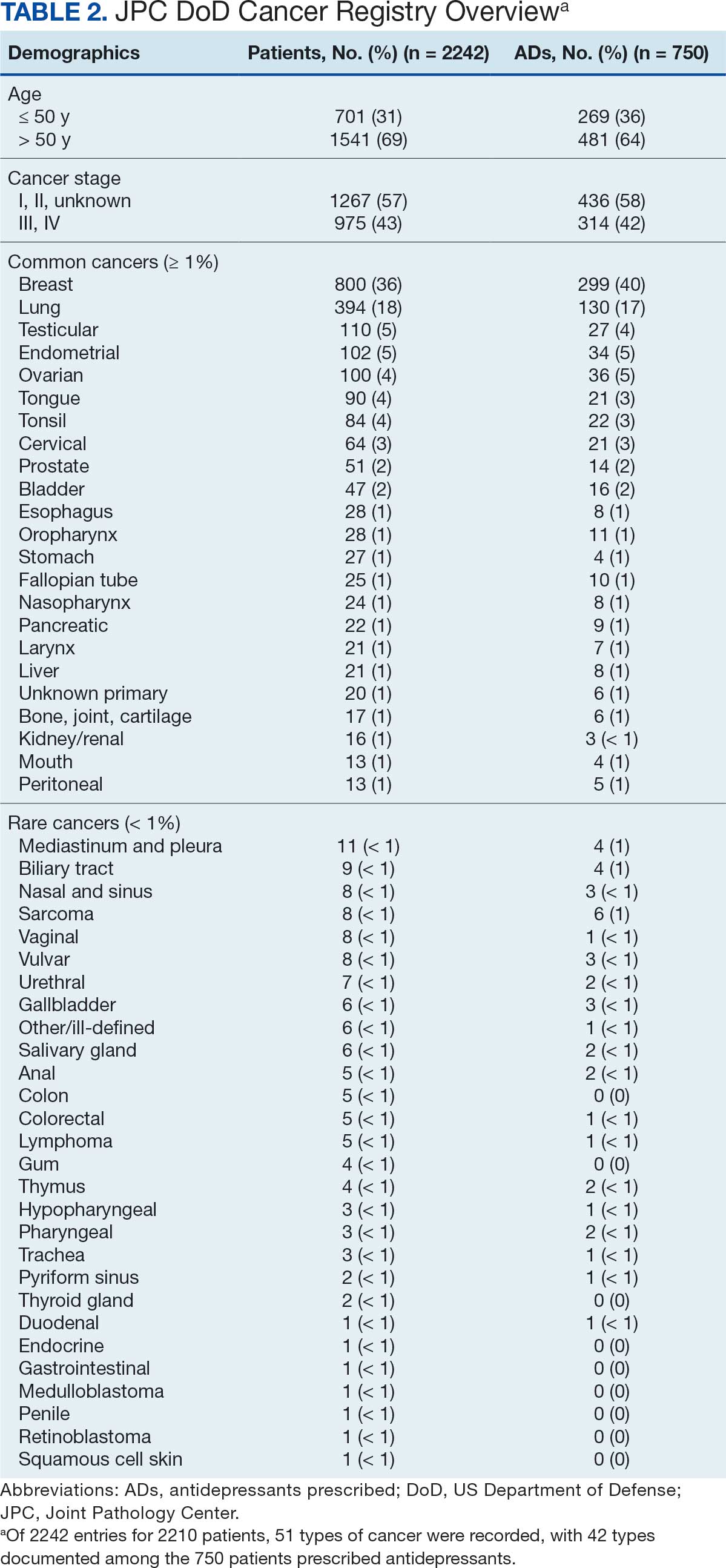

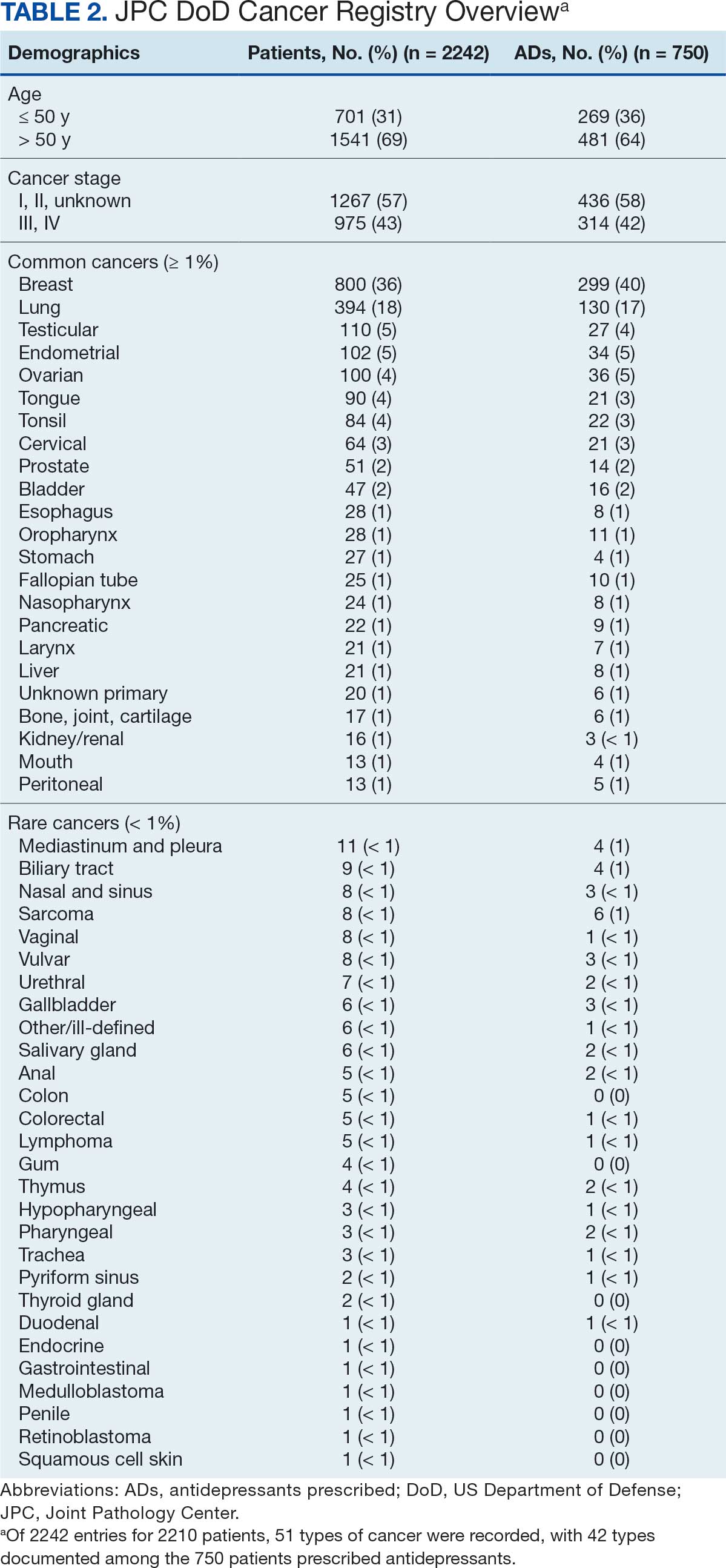

The JPC provided 2242 entries for 2210 patients, ranging in age from 2 months to 88 years (mean, 56 years), documenting treatment from September 1988 to January 2023. Thirty-two patients had duplicate entries due to multiple cancer locations or occurrences. Of the 2242 patients, 1541 (68.7%) were aged > 50 years, 975 patients (43.5%) had cancers that were stage III or IV, and 1267 (56.5%) had cancers that were stage 0, I, II, or not applicable/unknown. There were 51 different types of cancer: breast, lung, testicular, endometrial, and ovarian were most common (n ≥ 100 patients). Forty-two cancer types were documented among 750 patients prescribed antidepressants (Table 2).

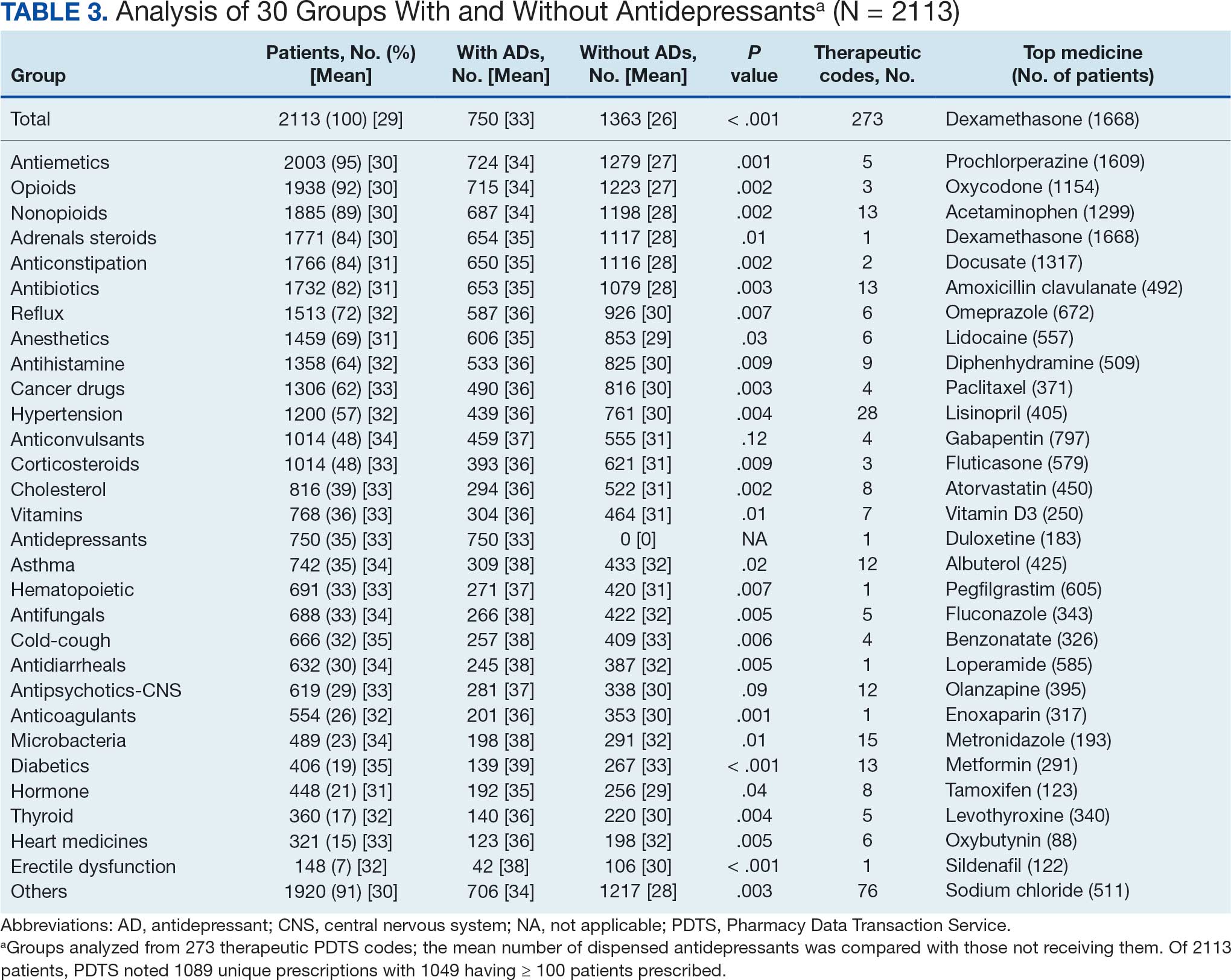

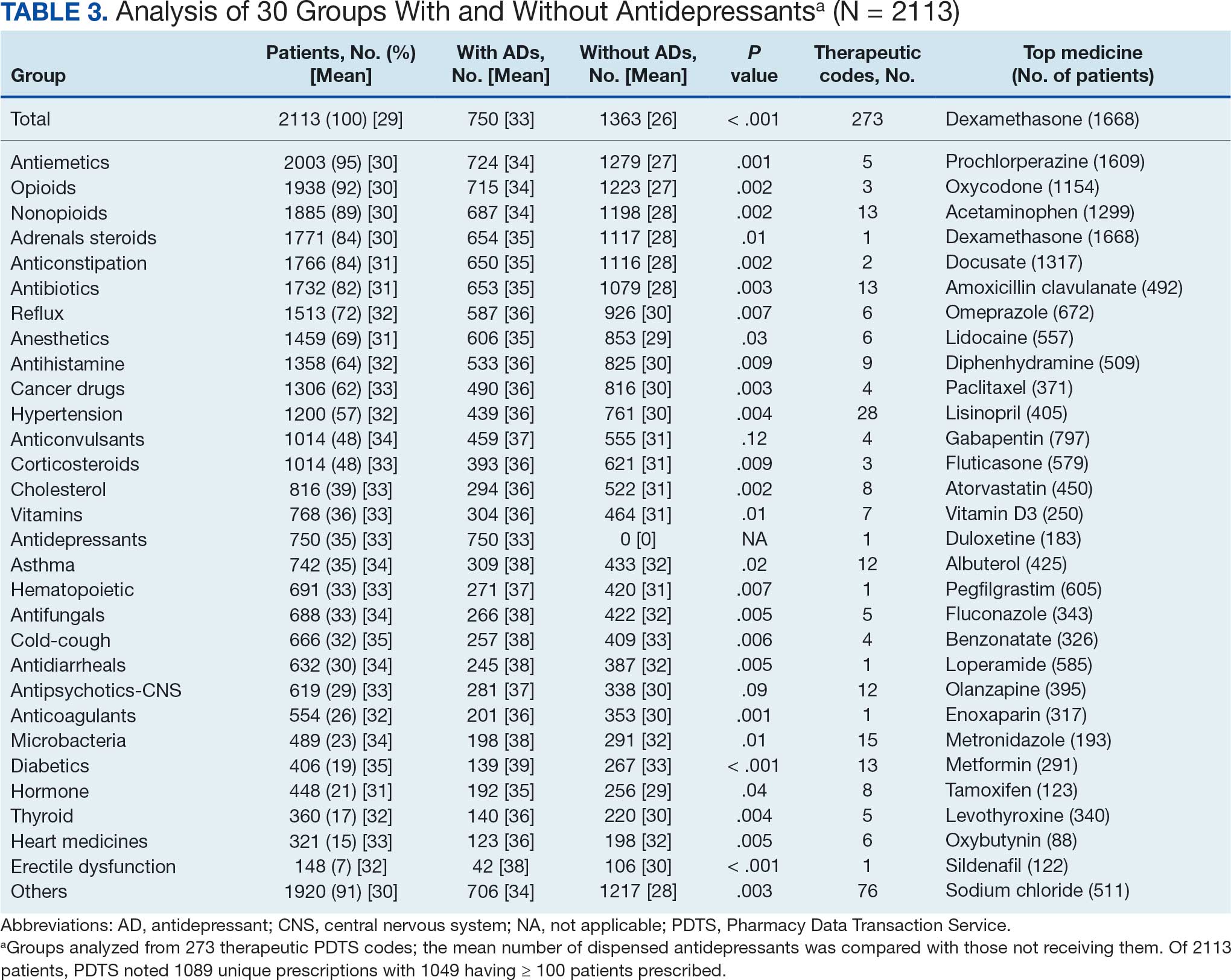

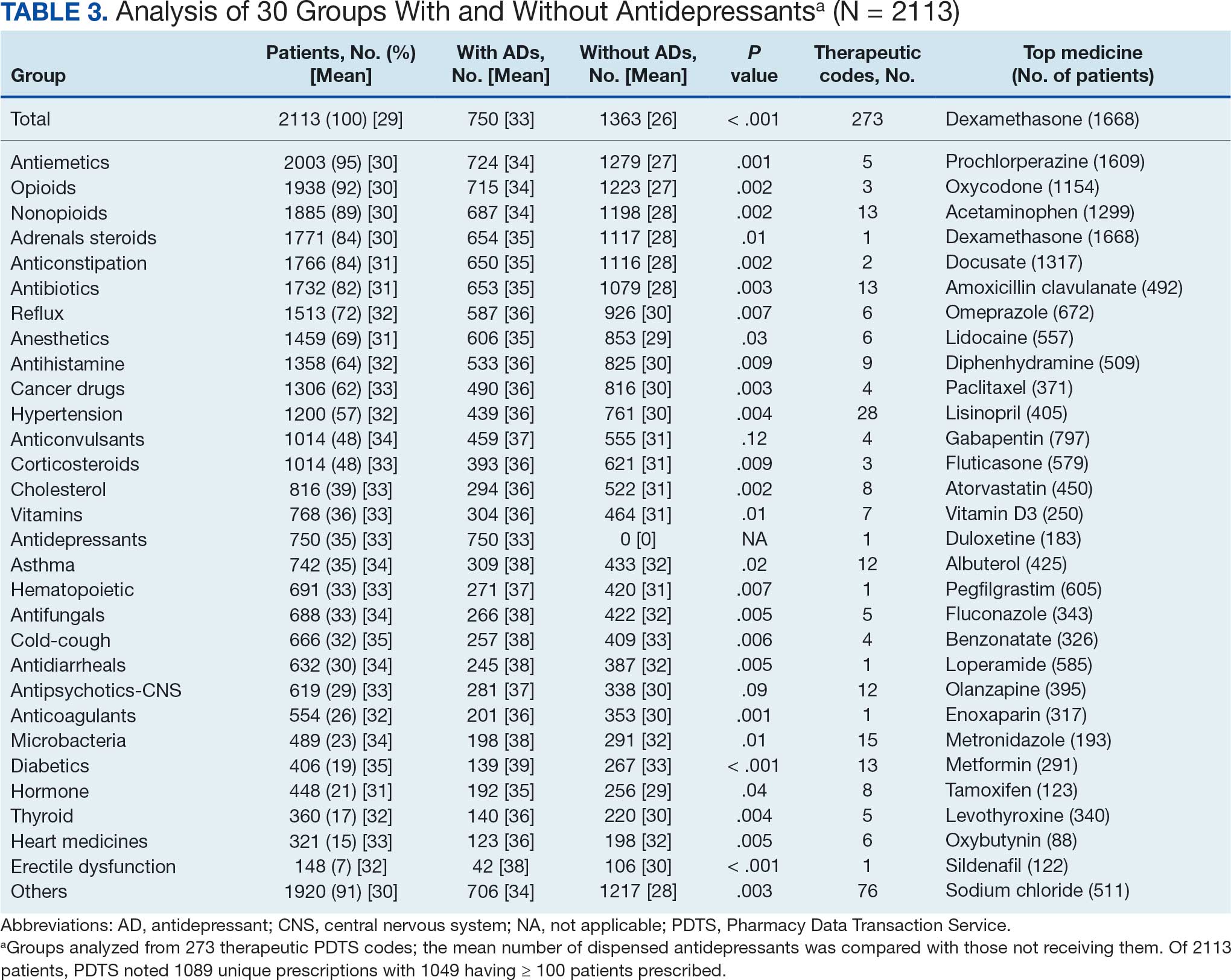

The CAPER database recorded 8882 unique diagnoses for 2104 patients, while PDTS noted 1089 unique prescriptions within 273 therapeutic codes for 2113 patients. Nine therapeutic codes (opiate agonists, adrenals, cathartics-laxatives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, antihistamines for GI conditions, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, analgesics and antipyretic miscellanea, antineoplastic agents, and proton-pump inhibitors) and 8 drugs (dexamethasone, prochlorperazine, ondansetron, docusate, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, oxycodone, and polyethylene glycol 3350) were associated with > 1000 patients (≥ 50%). Patients had between 1 and 275 unique health conditions and filled 1 to 108 prescriptions. The mean (SD) number of diagnoses and prescriptions was 50 (28) and 29 (12), respectively. Of the 273 therapeutic codes, 30 groups were analyzed, with others categorized into miscellaneous groups such as lotions, vaccines, and devices. Significant differences in mean number of prescriptions were found for patients taking antidepressants compared to those not (P < .05), except for anticonvulsants and antipsychotics (P = .12 and .09, respectively) (Table 3).

Antidepressants

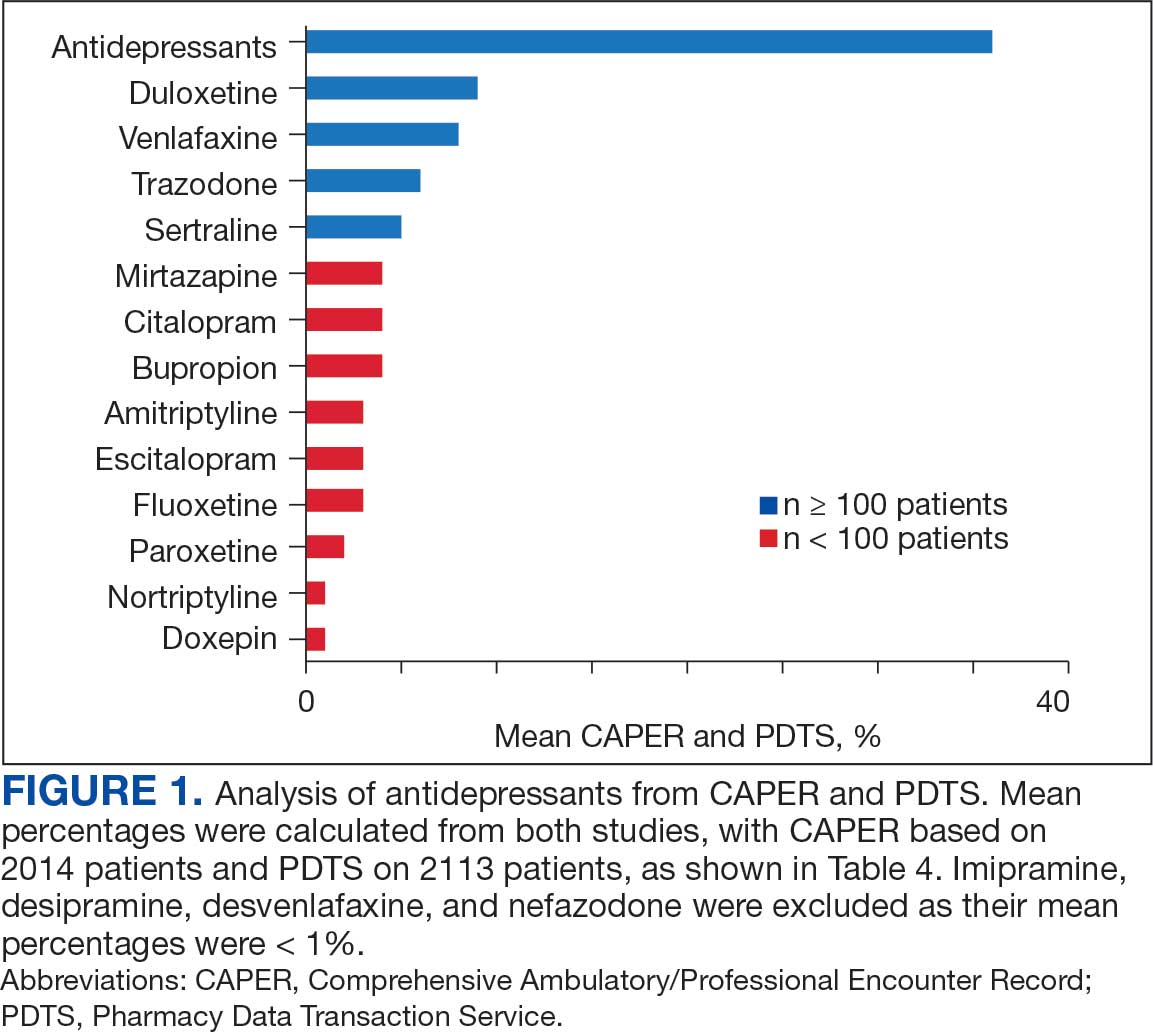

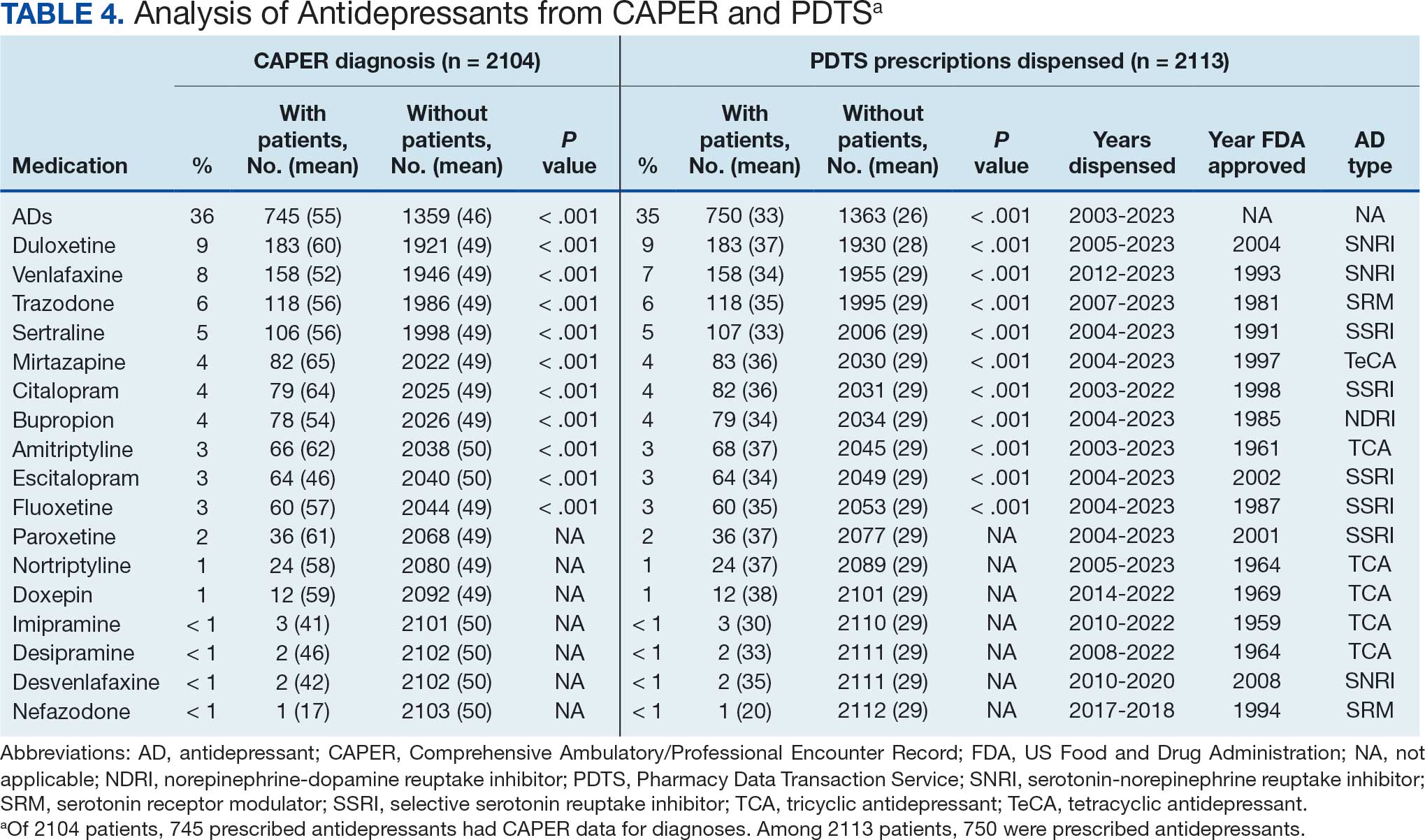

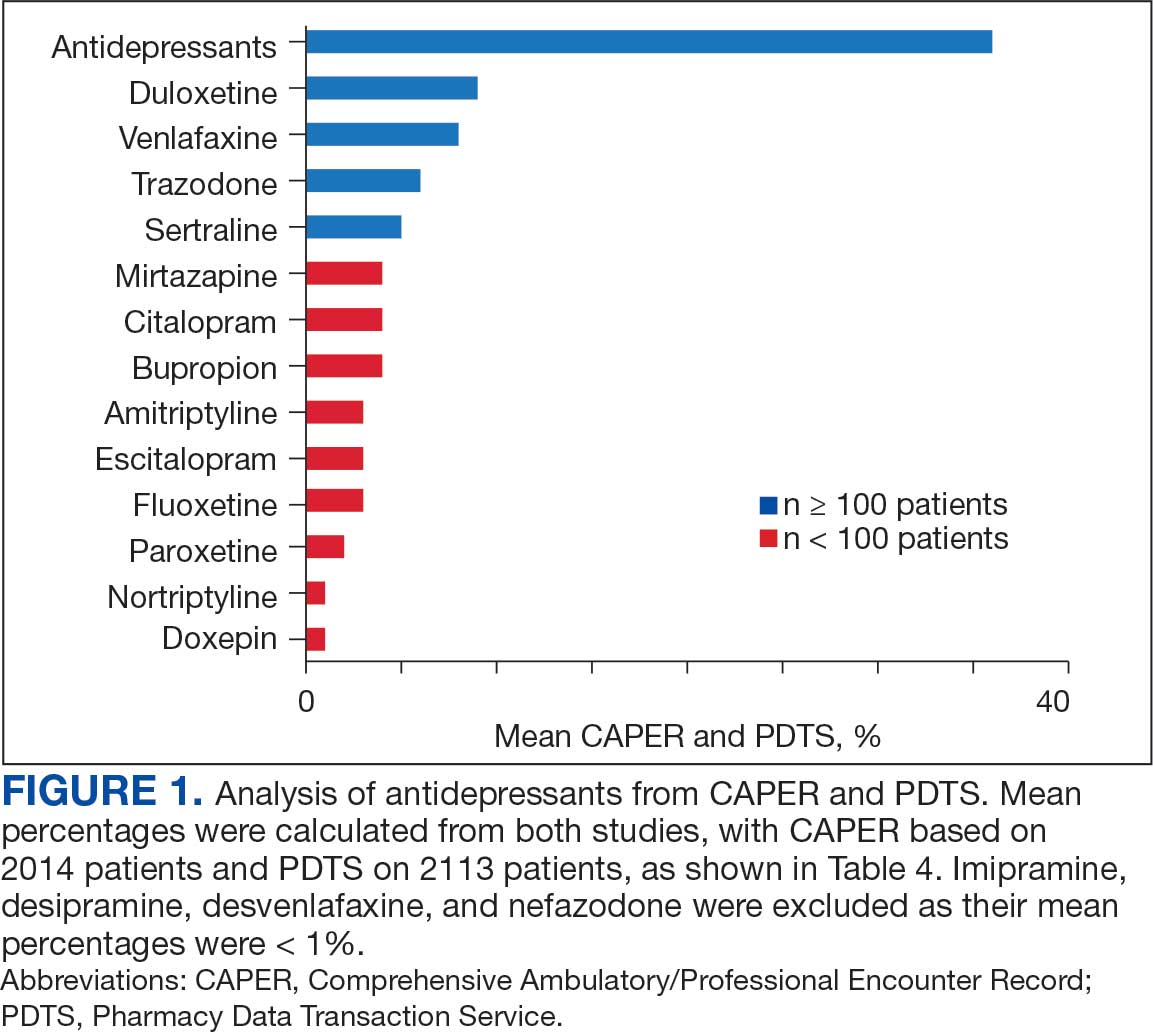

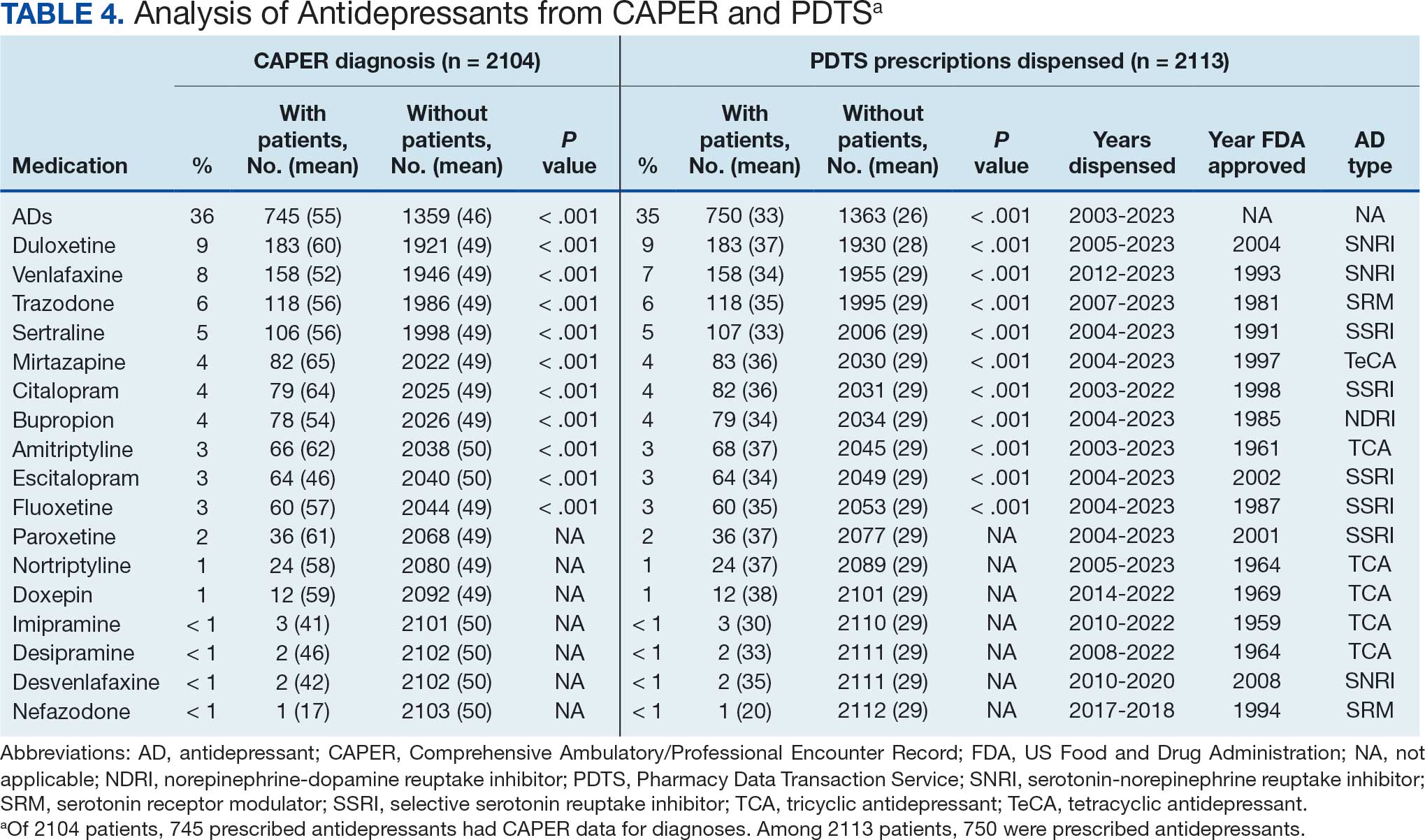

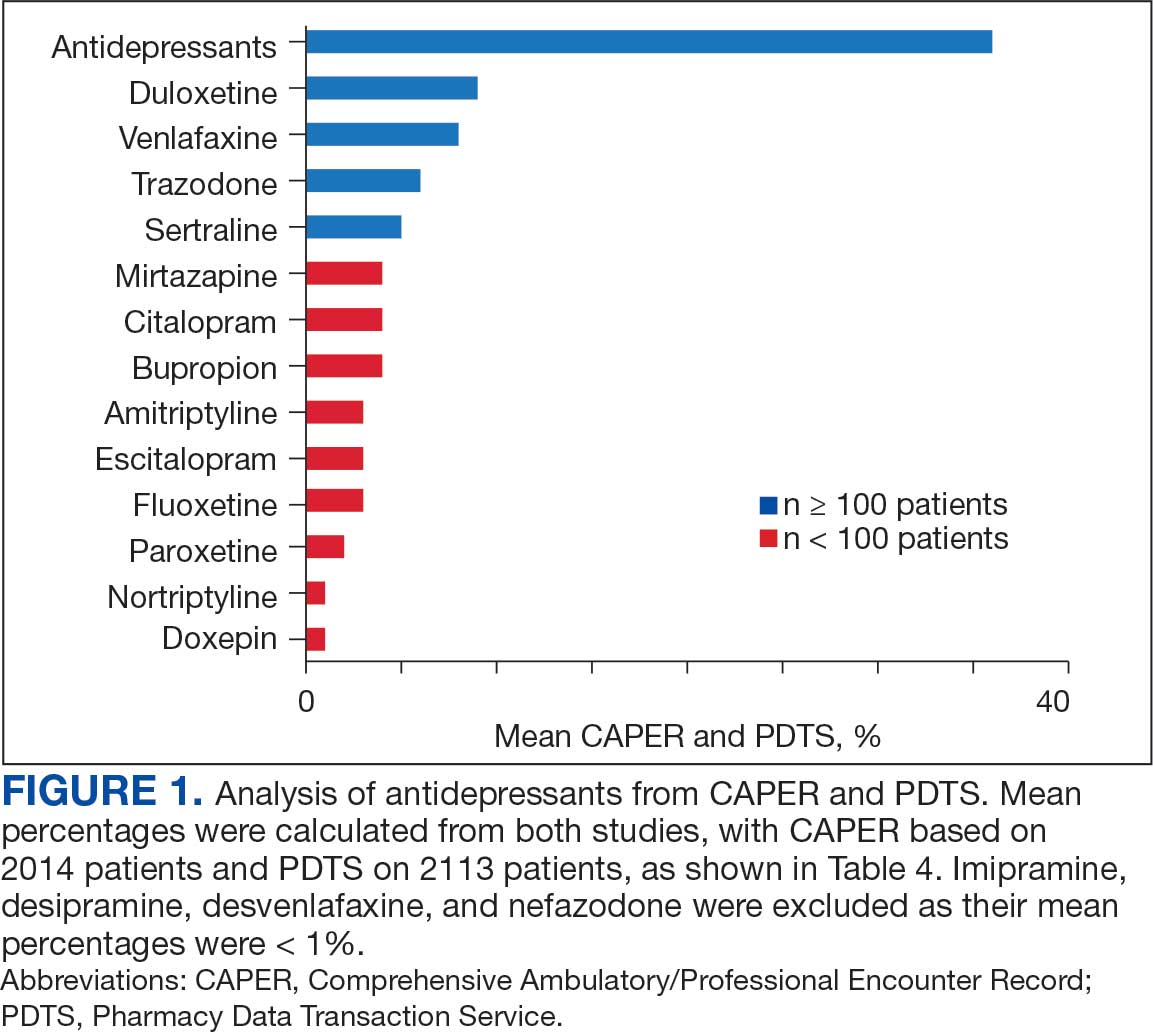

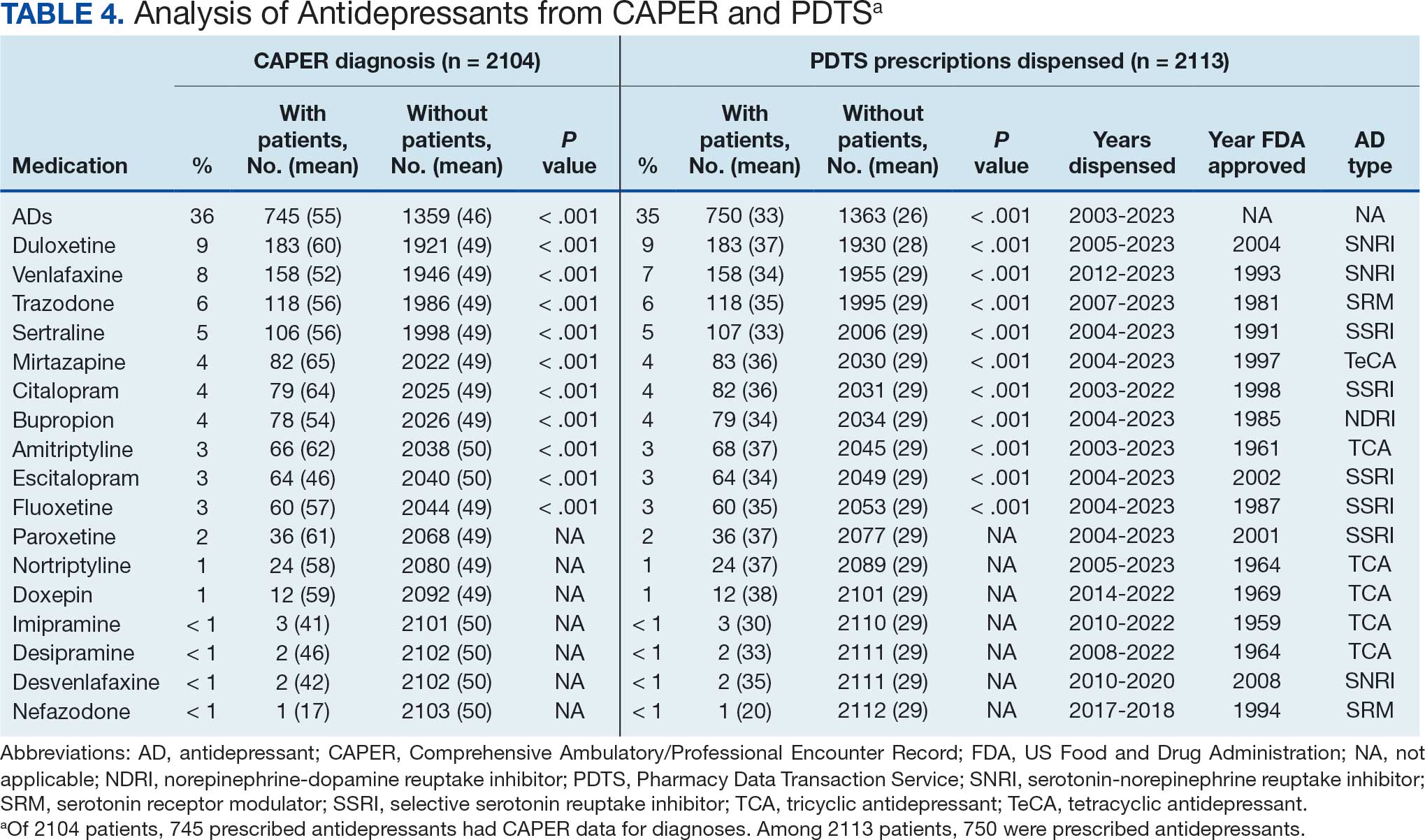

Of the 2113 patients with recorded prescriptions, 750 (35.5%) were dispensed 17 different antidepressants. Among these 17 antidepressants, 183 (8.7%) patients received duloxetine, 158 (7.5%) received venlafaxine, 118 (5.6%) received trazodone, and 107 (5.1%) received sertraline (Figure 1, Table 4). Of the 750 patients, 509 (67.9%) received 1 antidepressant, 168 (22.4%) received 2, 60 (8.0%) received 3, and 13 (1.7%) received > 3. Combinations varied, but only duloxetine and trazodone were prescribed to > 10 patients.

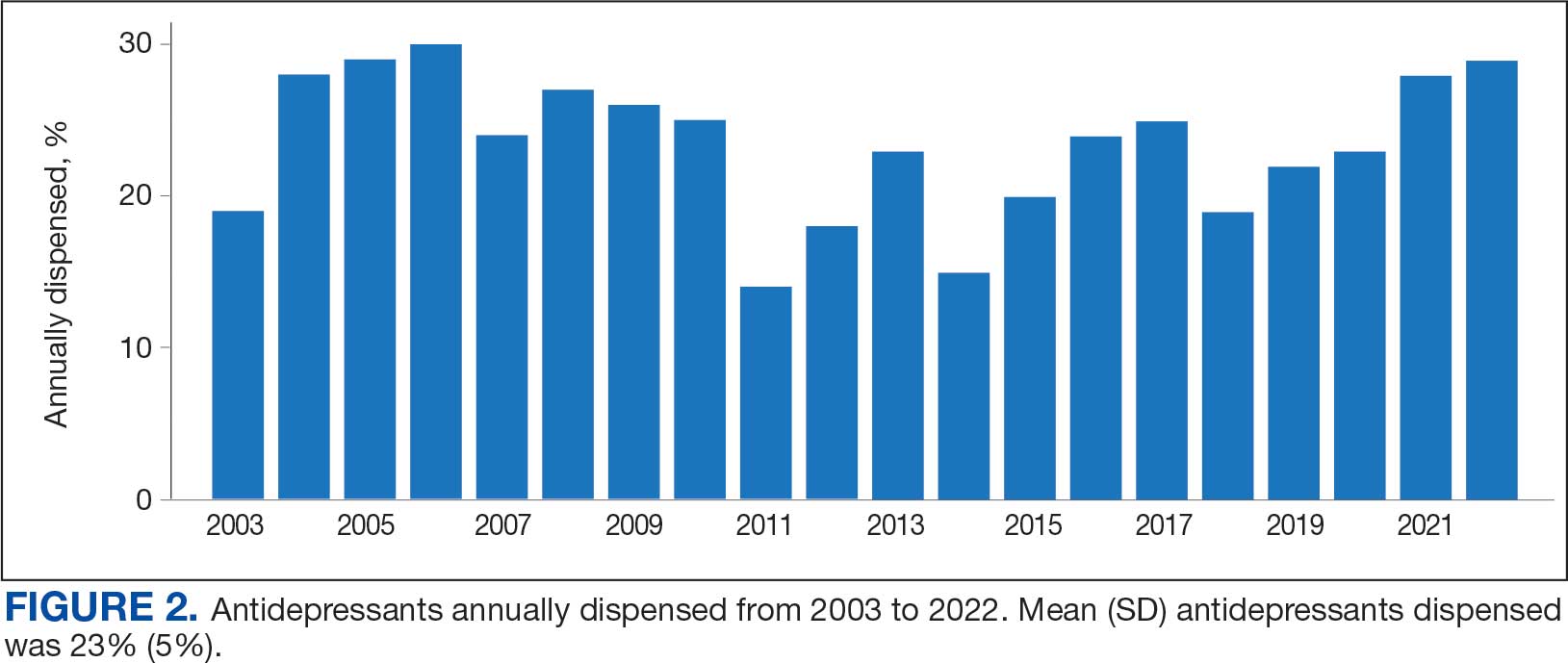

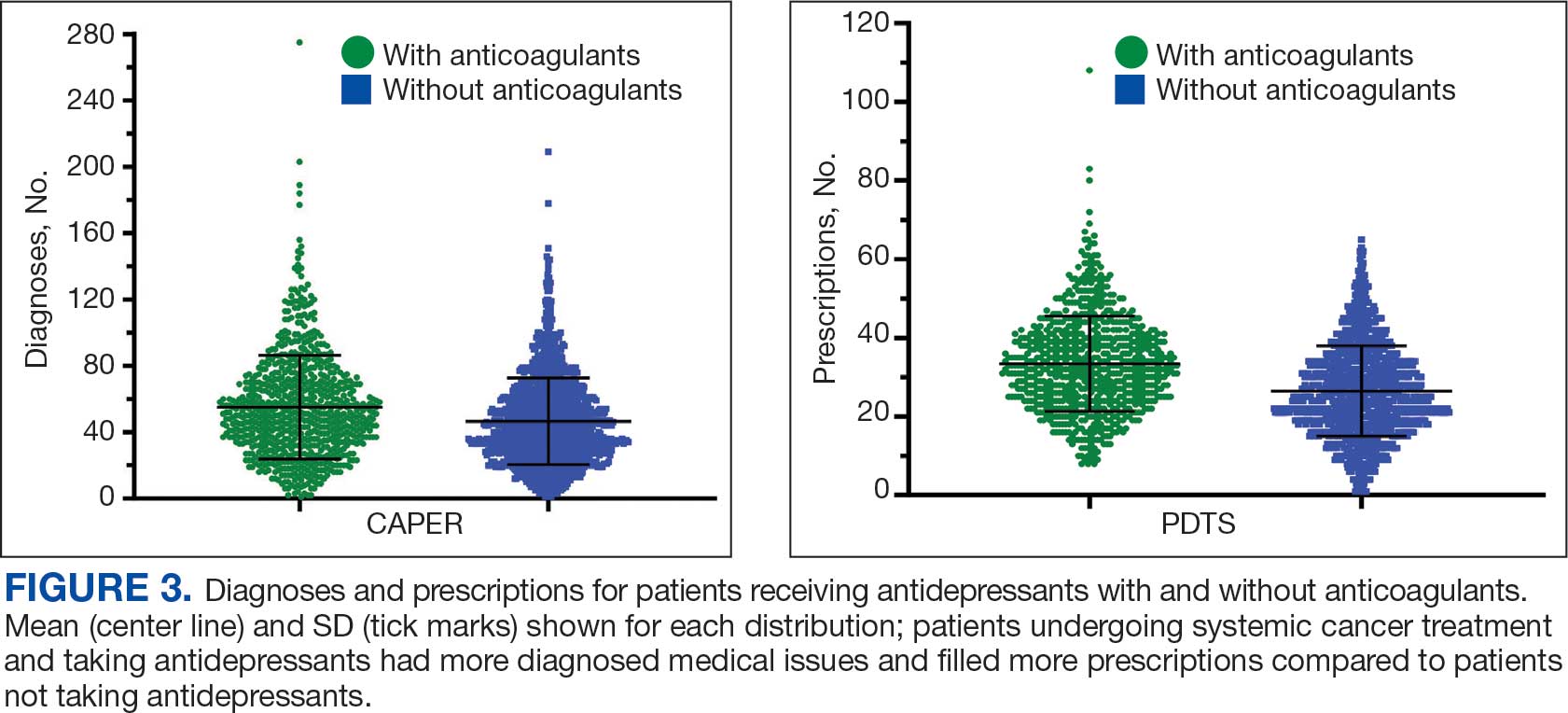

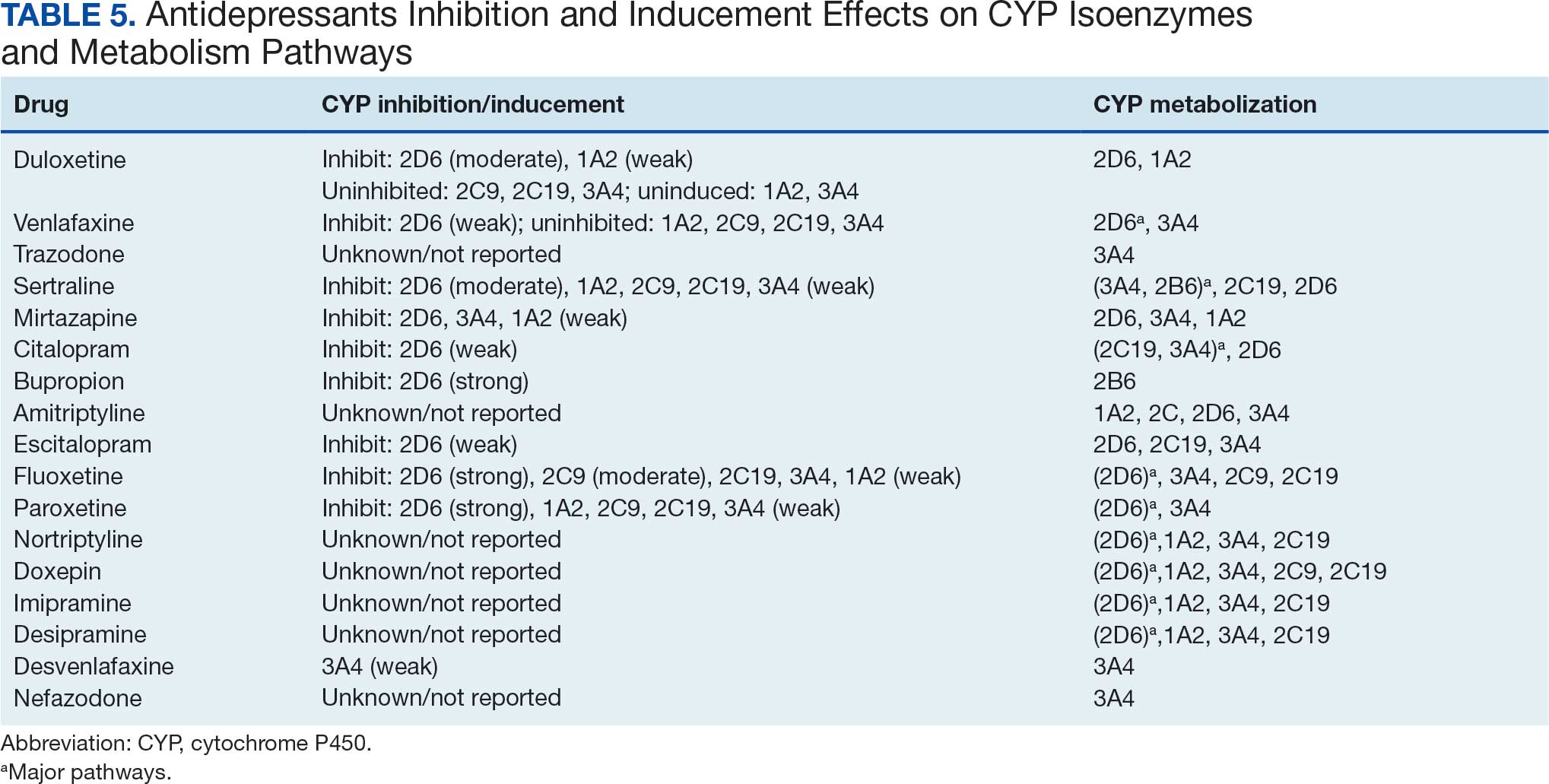

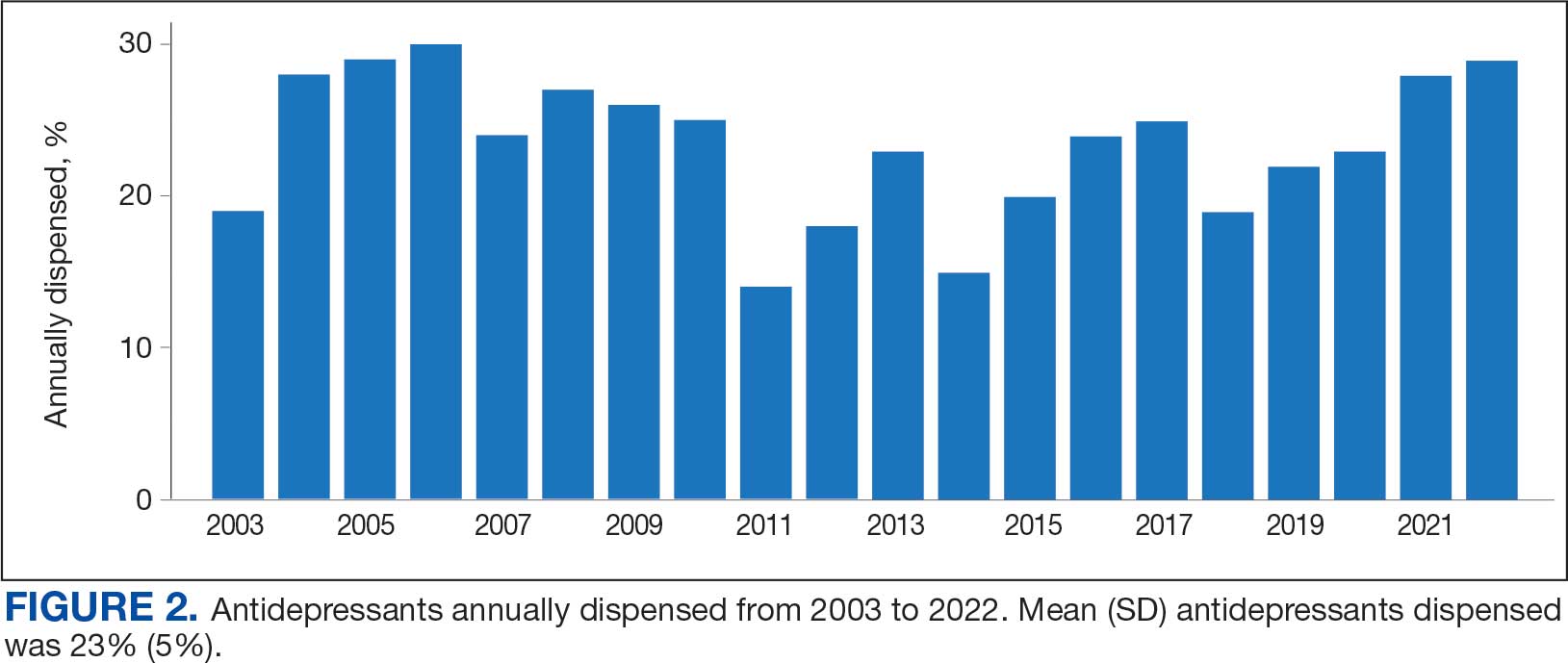

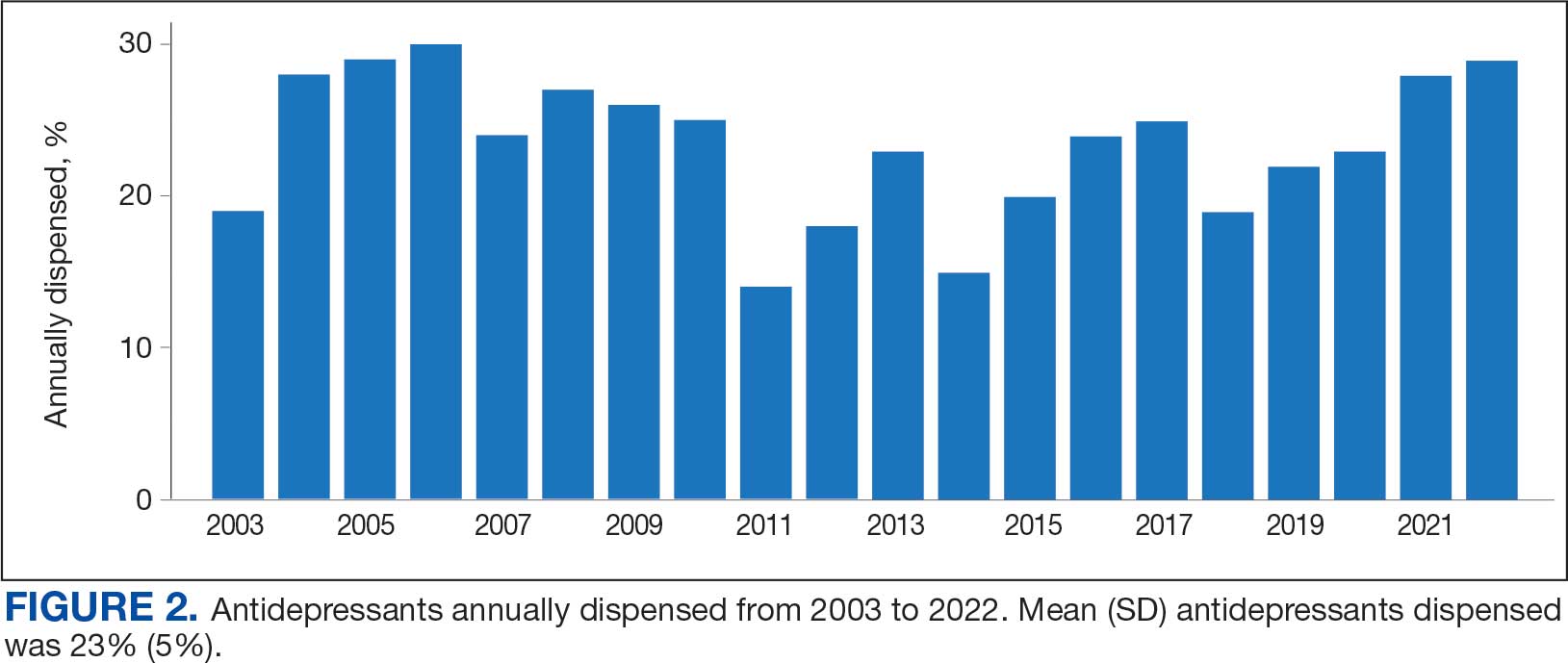

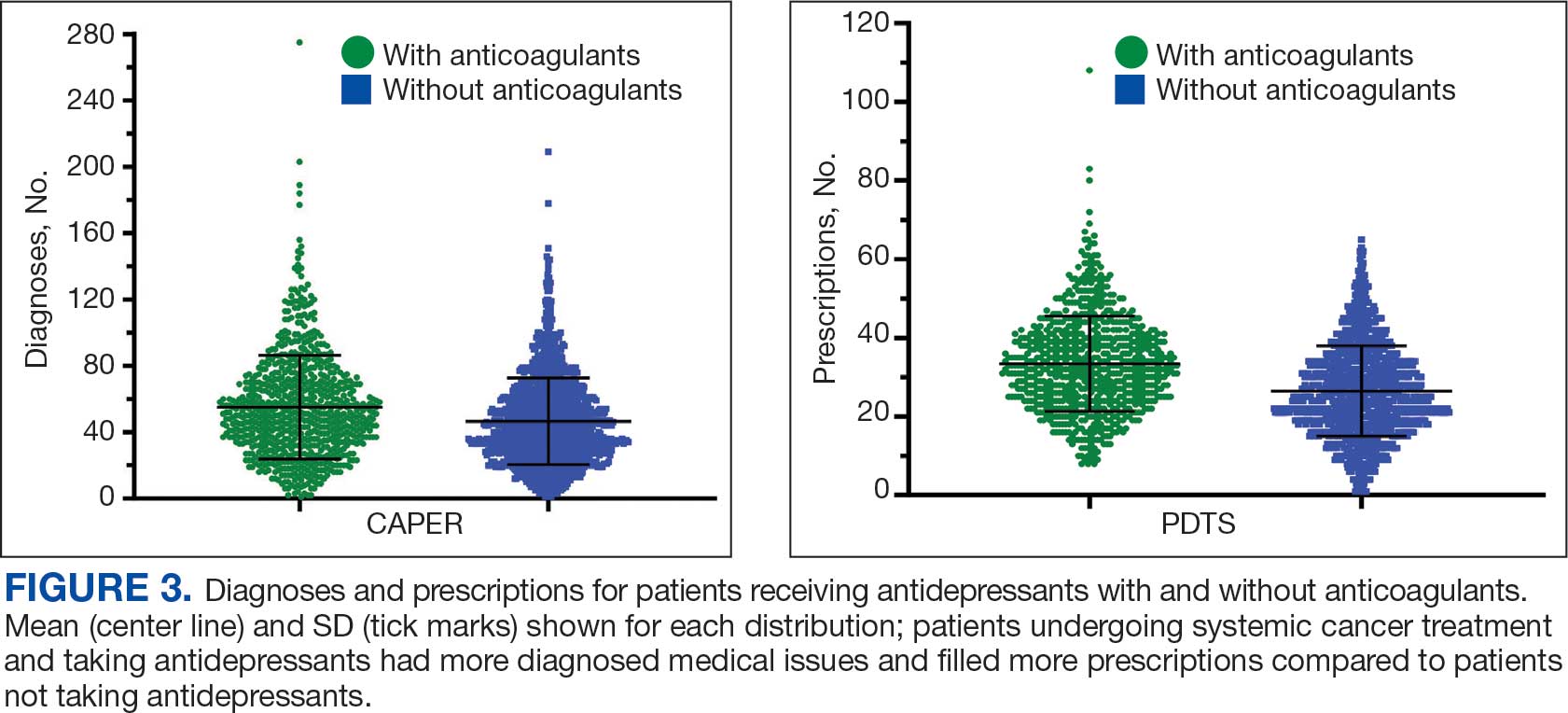

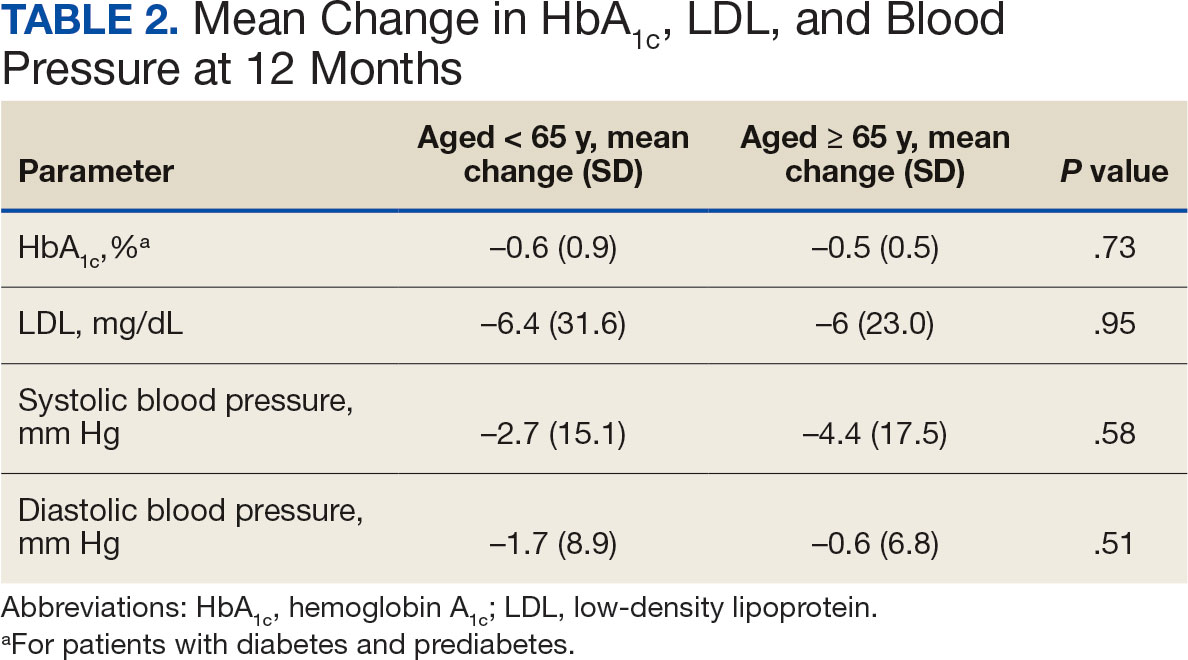

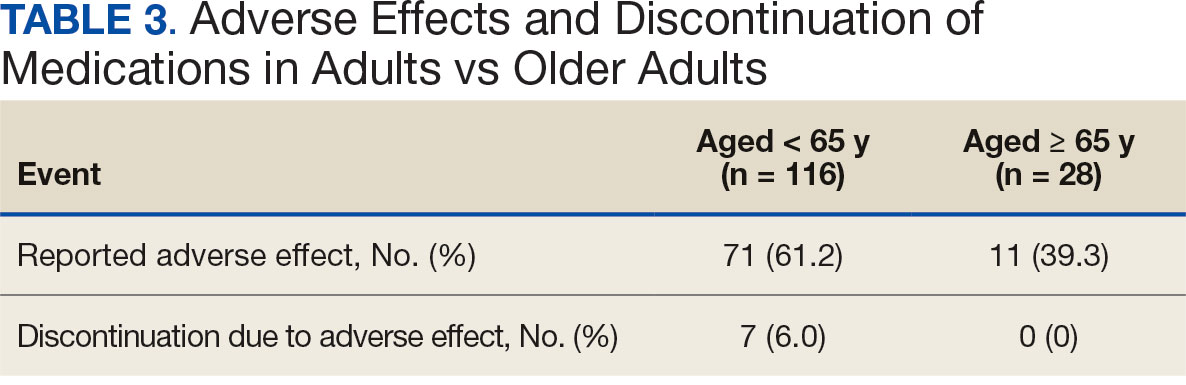

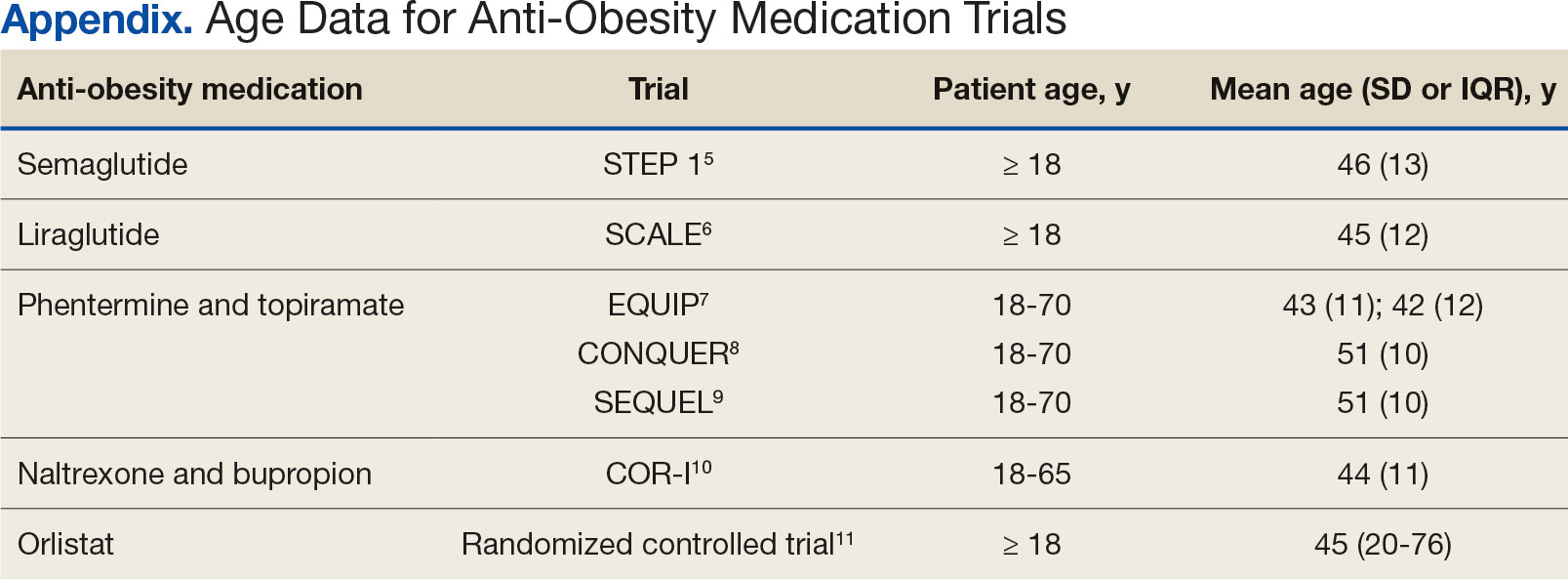

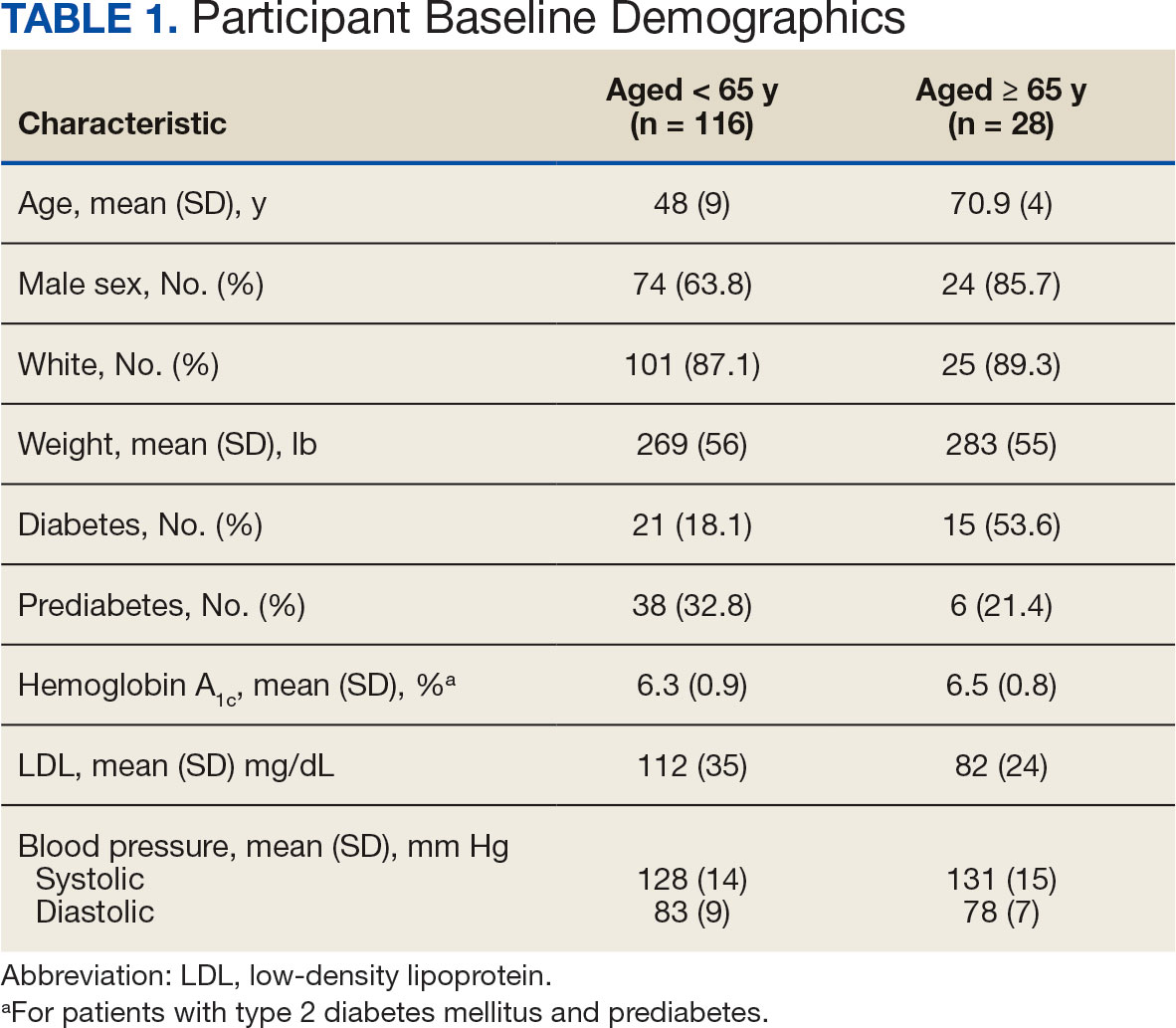

Antidepressants were prescribed annually at an overall mean (SD) rate of 23% (5%) from 2003 to 2022 (Figure 2). Patients on antidepressants during systemic therapy had a greater number of diagnosed medical conditions and received more prescription medications compared to those not taking antidepressants (P < .001) (Figure 3). The 745 patients taking antidepressants in CAPER data had between 1 and 275 diagnosed medical issues, with a mean (SD) of 55 (31) vs a range of 1 to 209 and a mean (SD) of 46 (26) for the 1359 patients not taking antidepressants. The 750 patients on antidepressants in PDTS data had between 8 and 108 prescriptions dispensed, with a mean (SD) of 32 (12), vs a range of 1 to 65 prescriptions and a mean (SD) of 29 (12) for 1363 patients not taking antidepressants.

Discussion

The JPC DoD Cancer Registry includes information on cancer types, stages, treatment regimens, and physicians’ notes, while noncancer drugs are sourced from the PDTS database. The pharmacy uses a different documentation system, leading to varied classifications.

Database reliance has its drawbacks. For example, megestrol is coded as a cancer drug, although it’s primarily used for endometrial or gynecologic cancers. Many drugs have multiple therapeutic codes assigned to them, including 10 antineoplastic agents: diclofenac, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), megestrol acetate, tamoxifen, anastrozole, letrozole, leuprolide, goserelin, degarelix, and fluorouracil. Diclofenac, BCG, and mitomycin have been repurposed for cancer treatment.84-87 From 2003 to 2023, diclofenac was prescribed to 350 patients for mild-to-moderate pain, with only 2 patients receiving it for cancer in 2018. FDA-approved for bladder cancer in 1990, BCG was prescribed for cancer treatment for 1 patient in 2021 after being used for vaccines between 2003 and 2018. Tamoxifen, used for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer from 2004 to 2017 with 53 patients, switched to estrogen agonist-antagonists from 2017 to 2023 with 123 patients. Only a few of the 168 patients were prescribed tamoxifen using both codes.88-91 Anastrozole and letrozole were coded as antiestrogens for 7 and 18 patients, respectively, while leuprolide and goserelin were coded as gonadotropins for 59 and 18 patients. Degarelix was coded as antigonadotropins, fluorouracil as skin and mucous membrane agents miscellaneous, and megestrol acetate as progestins for 7, 6, and 3 patients, respectively. Duloxetine was given to 186 patients, primarily for depression from 2005 to 2023, with 7 patients treated for fibromyalgia from 2022 to 2023.

Antidepressants Observed

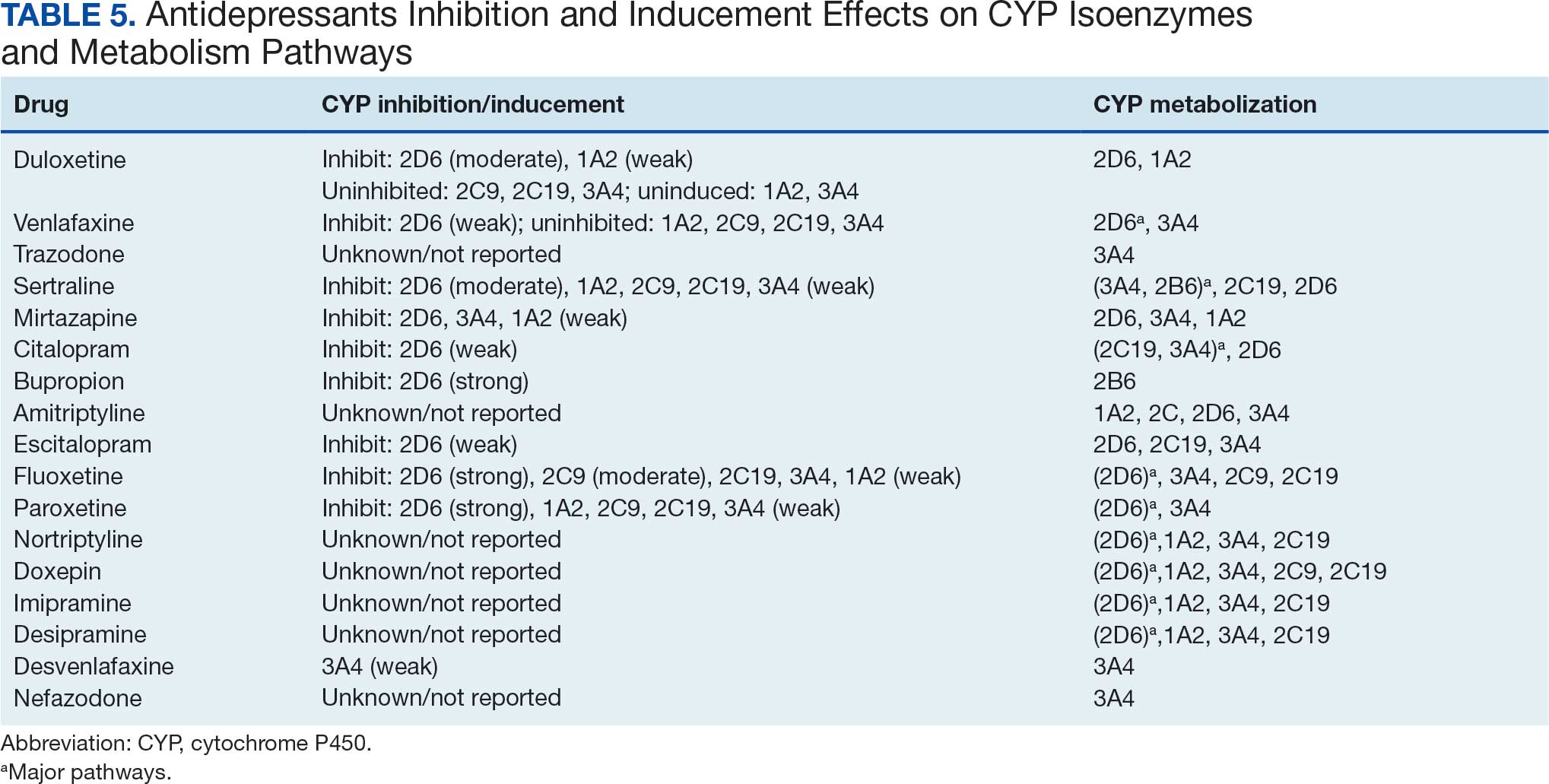

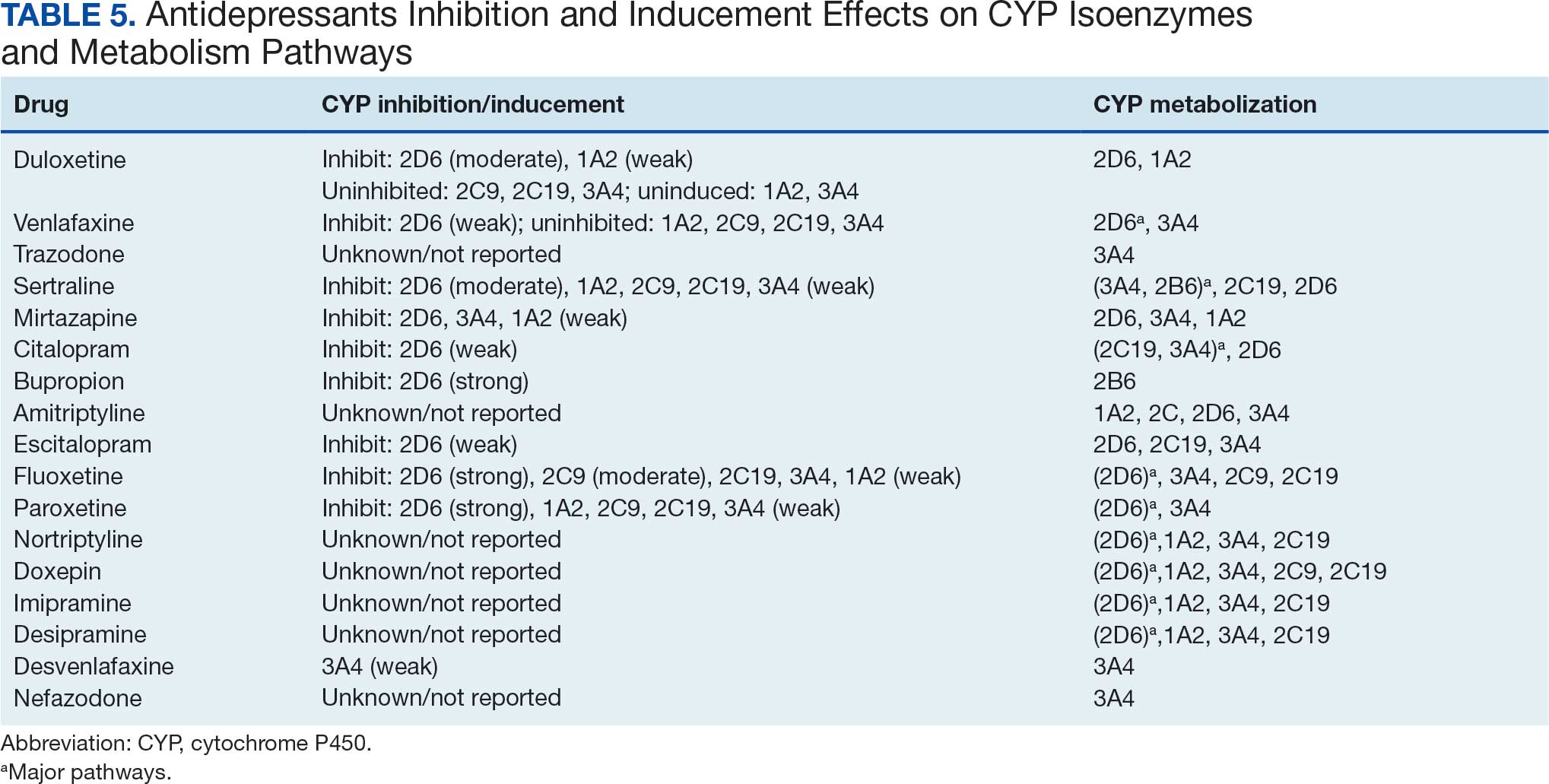

Tables 1 and 5 provide insight into the FDA approval of 14 antineoplastics and antidepressants and their CYP metabolic pathways.92-122 In Table 4, the most prescribed antidepressant classes are SNRIs, SRMs, SSRIs, TeCAs, NDRIs, and TCAs. This trend highlights a preference for newer medications with weak CYP inhibition. A total of 349 patients were prescribed SSRIs, 343 SNRIs, 119 SRMs, 109 TCAs, 83 TeCAs, and 79 NDRIs. MAOIs, SMRAs, and NMDARAs were not observed in this dataset. While there are instances of dextromethorphan-bupropion and sertraline-escitalopram being dispensed together, it remains unclear whether these were NMDARA combinations.

Among the 14 specific antineoplastic agents, 10 are metabolized by CYP isoenzymes, primarily CYP3A4. Duloxetine neither inhibits nor is metabolized by CYP3A4, a reason it is often recommended, following venlafaxine.

Both duloxetine and venlafaxine are used off-label for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy related to paclitaxel and docetaxel. According to the CYP metabolized pathway, duloxetine tends to have more favorable DDIs than venlafaxine. In PDTS data, 371 patients were treated with paclitaxel and 180 with docetaxel, with respective antidepressant prescriptions of 156 and 70. Of the 156 patients dispensed paclitaxel, 62 (40%) were dispensed with duloxetine compared to 43 (28%) with venlafaxine. Of the 70 patients dispensed docetaxel, 23 (33%) received duloxetine vs 24 (34%) with venlafaxine.

Of 85 patients prescribed duloxetine, 75 received it with either paclitaxel or docetaxel (5 received both). Five patients had documented AEs (1 neuropathy related). Of 67 patients prescribed venlafaxine, 66 received it with either paclitaxel or docetaxel. Two patients had documented AEs (1 was neuropathy related, the same patient who received duloxetine). Of the 687 patients treated with paclitaxel and 337 with docetaxel in all databases, 4 experienced neuropathic AEs from both medications.79

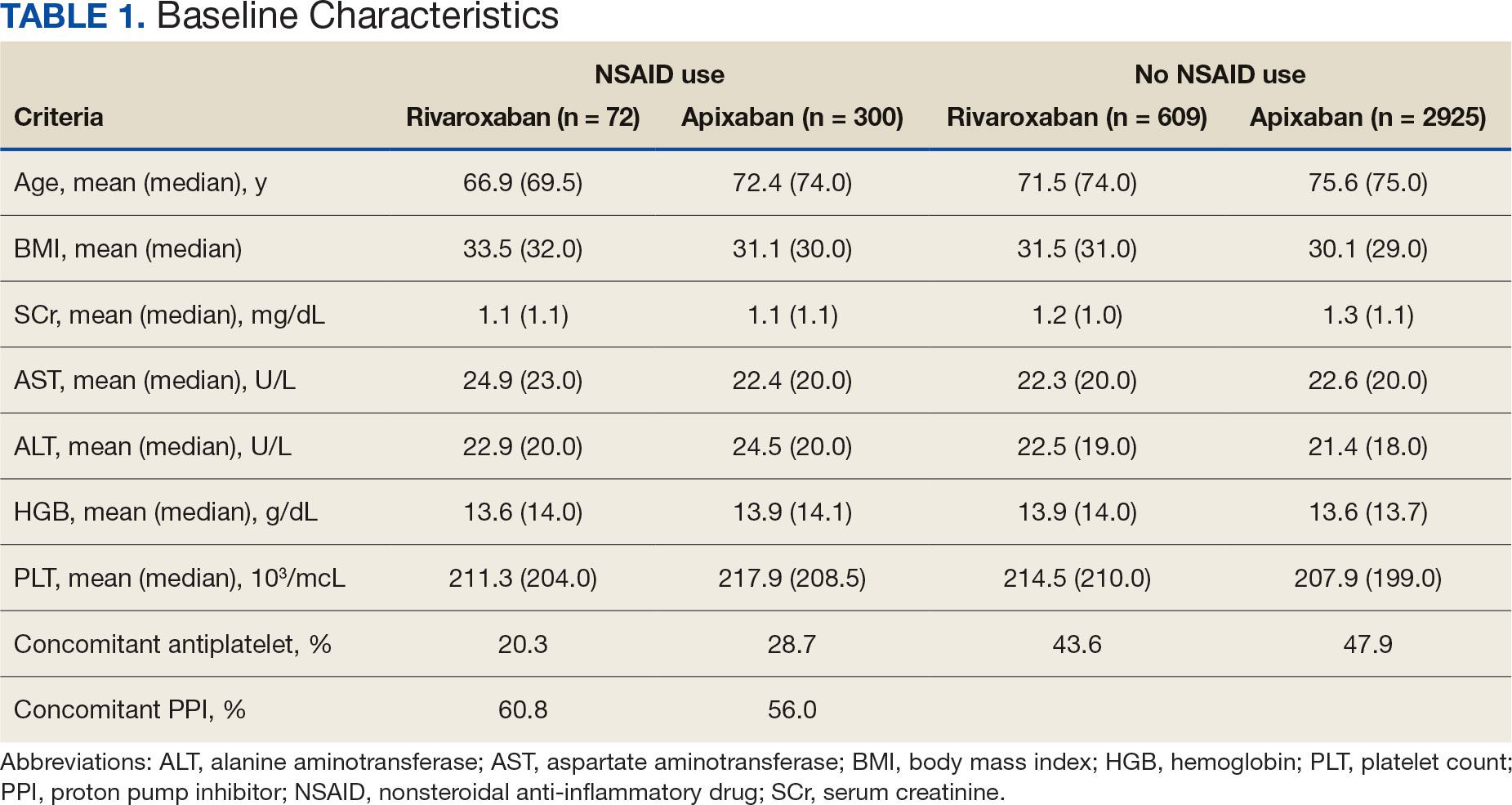

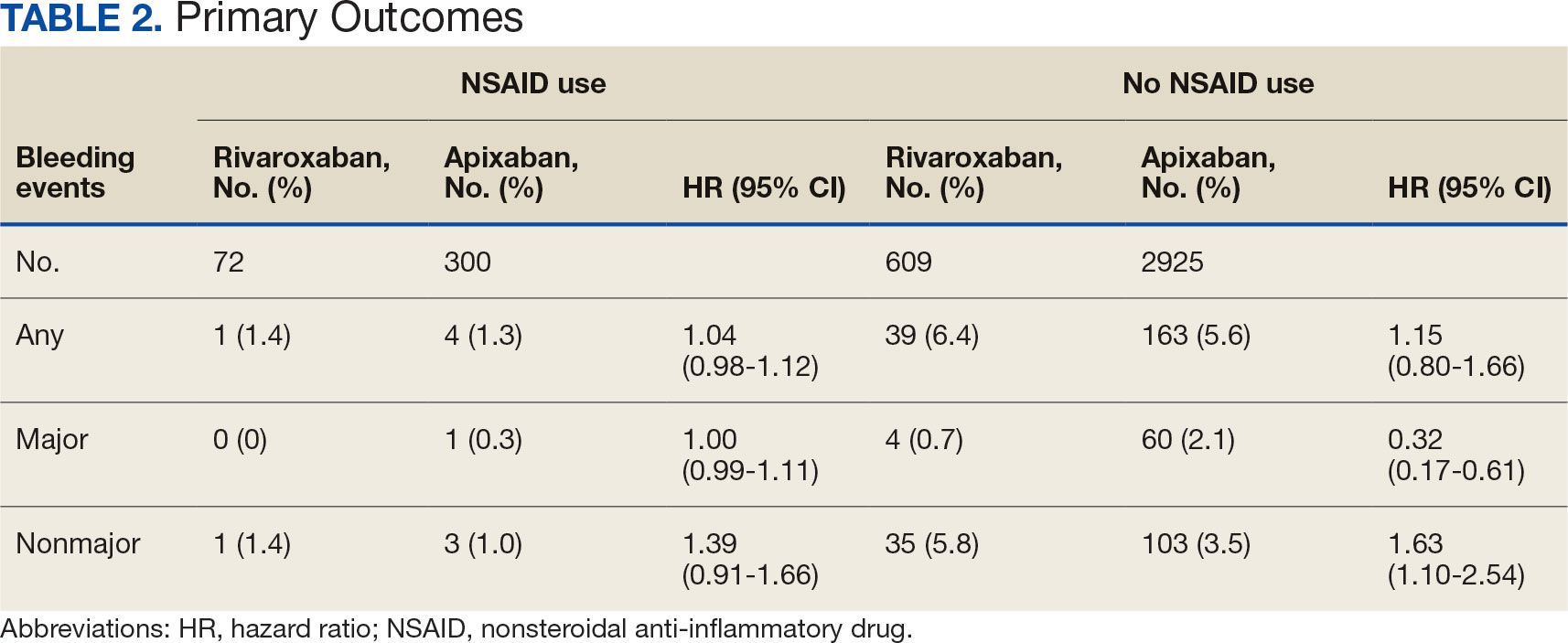

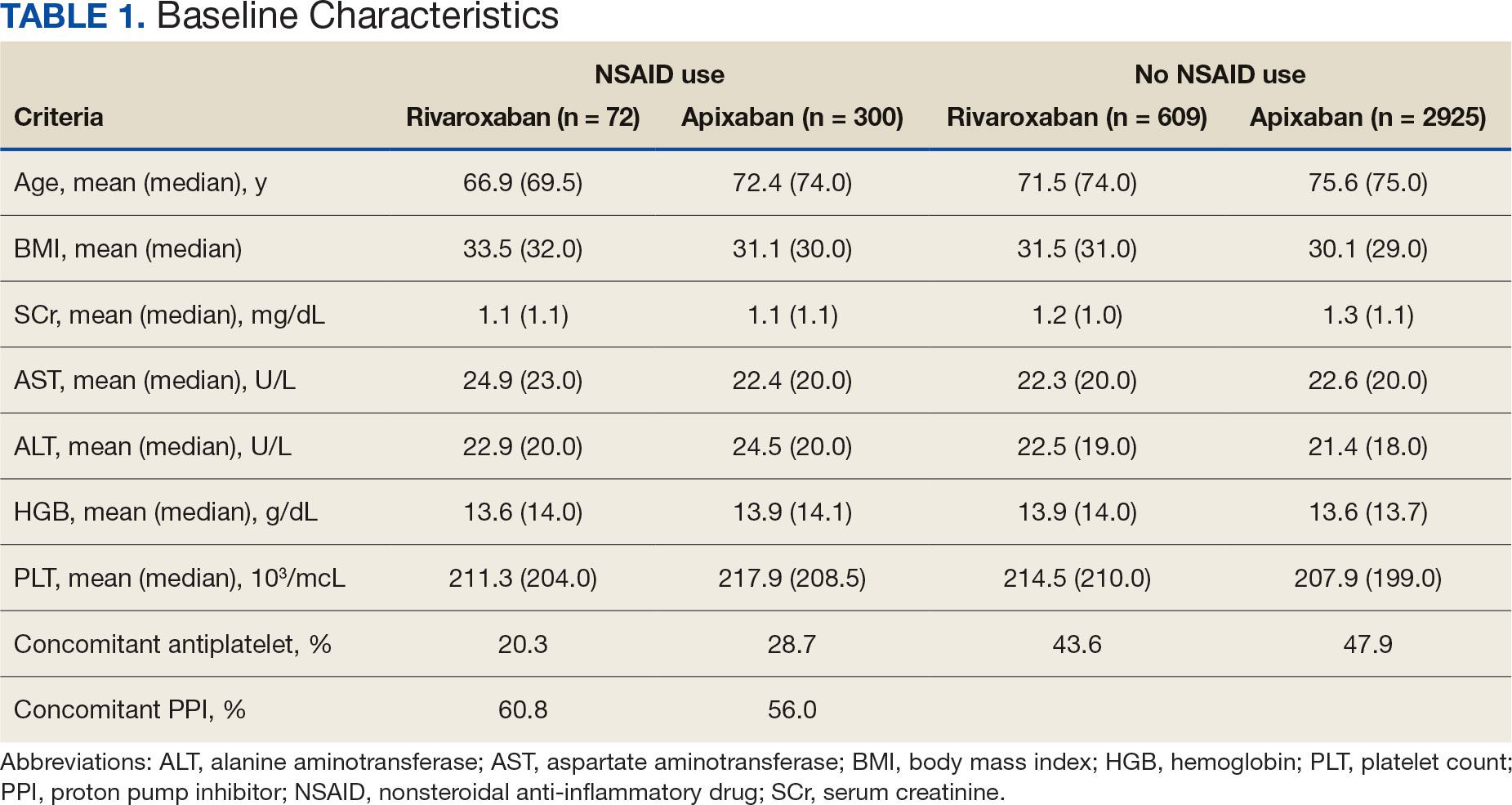

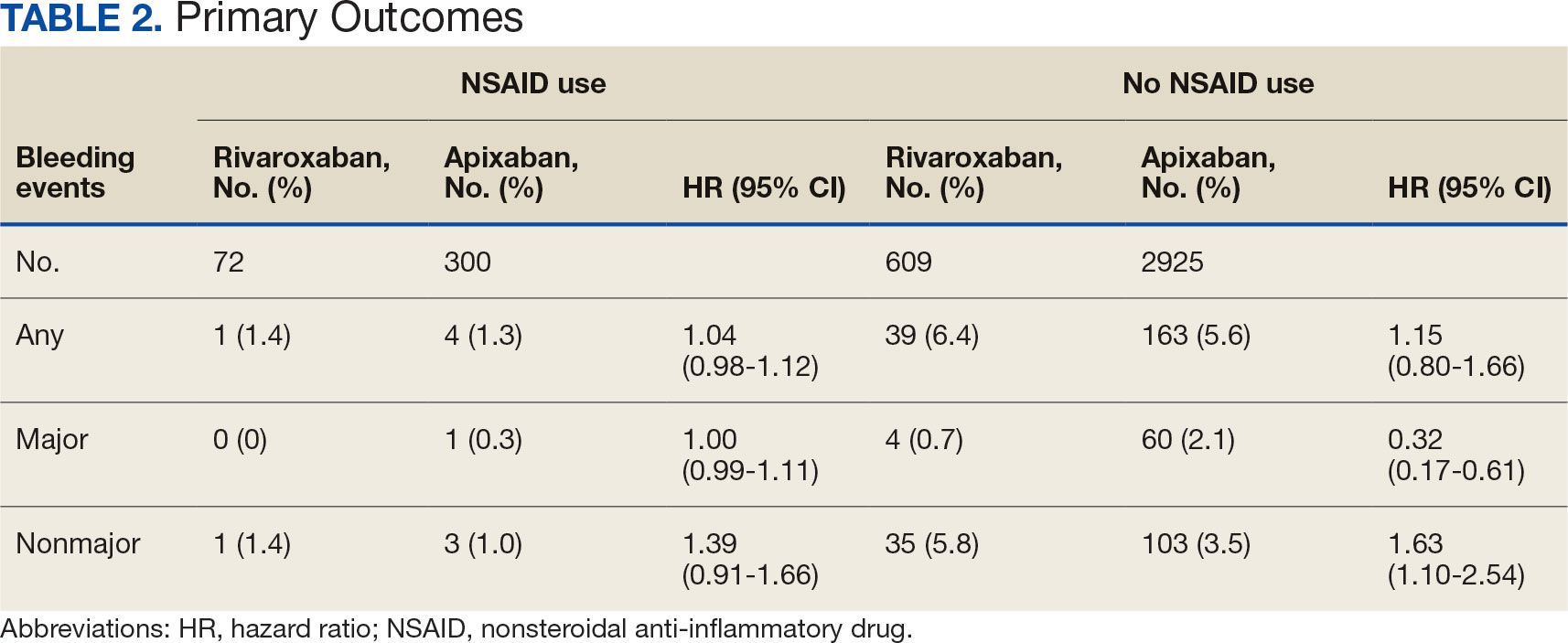

Antidepressants can increase the risk of bleeding, especially when combined with blood thinners, and may elevate blood pressure, particularly alongside stimulants. Of the 554 patients prescribed 9 different anticoagulants, enoxaparin, apixaban, and rivaroxaban were the most common (each > 100 patients). Among these, 201 patients (36%) received both anticoagulants and antidepressants: duloxetine for 64 patients, venlafaxine for 30, trazodone for 35, and sertraline for 26. There were no data available to assess bleeding rates related to the evaluation of DDIs between these medication classes.

Antidepressants can be prescribed for erectile dysfunction. Of the 148 patients prescribed an antidepressant for erectile dysfunction, duloxetine, trazodone, and mirtazapine were the most common. Antidepressant preferences varied by cancer type. Duloxetine was the only antidepressant used for all types of cancer. Venlafaxine, duloxetine, trazodone, sertraline, and escitalopram were the most prescribed antidepressants for breast cancer, while duloxetine, mirtazapine, citalopram, sertraline, and trazodone were the most prescribed for lung cancer. Sertraline, duloxetine, trazodone, amitriptyline, and escitalopram were most common for testicular cancer. Duloxetine, venlafaxine, trazodone, amitriptyline, and sertraline were the most prescribed for endometrial cancer, while duloxetine, venlafaxine, amitriptyline, citalopram, and sertraline were most prescribed for ovarian cancer.

The broadness of International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes made it challenging to identify nondepression diagnoses in the analyzed population. However, if all antidepressants were prescribed to treat depression, service members with cancer exhibited a higher depression rate (35%) than the general population (25%). Of 2104 patients, 191 (9.1%) had mood disorders, and 706 (33.6%) had mental disorders: 346 (49.0%) had 1 diagnosis, and 360 (51.0%) had multiple diagnoses. The percentage of diagnoses varied yearly, with notable drops in 2003, 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2018, and peaks in 2006, 2008, 2013, 2017, and 2022. This fluctuation was influenced by events like the establishment of PDTS in 2002, the 2008 economic recession, a hospital relocation in 2011, the 2014 Ebola outbreak, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the number of patients receiving antidepressants increased from 2019 to 2022, the overall percentage of patients receiving them did not significantly change from 2003 to 2022, aligning with previous research.5,125

Many medications have potential uses beyond what is detailed in the prescribing information. Antidepressants can relieve pain, while pain medications may help with depression. Opioids were once thought to effectively treat depression, but this perspective has changed with a greater understanding of their risks, including misuse.126-131 Pain is a severe and often unbearable AE of cancer. Of 2113 patients, 92% received opioids; 34% received both opioids and antidepressants; 2% received only antidepressants; and 7% received neither. This study didn’t clarify whether those on opioids alone recognized their depression or if those on both were aware of their dependence. While SSRIs are generally not addictive, they can lead to physical dependence, and any medication can be abused if not managed properly.132-134

Conclusions

This retrospective study analyzes data from antineoplastic agents used in systemic cancer treatment between 1988 and 2023, with a particular focus on the use of antidepressants. Data on antidepressant prescriptions are incomplete and specific to these agents, which means the findings cannot be generalized to all antidepressants. Hence, the results indicate that patients taking antidepressants had more diagnosed health issues and received more medications compared to patients who were not on these drugs.

This study underscores the need for further research into the effects of antidepressants on cancer treatment, utilizing all data from the DoD Cancer Registry. Future research should explore DDIs between antidepressants and other cancer and noncancer medications, as this study did not assess AE documentation, unlike in studies involving erlotinib, gefitinib, and paclitaxel.78,79 Further investigation is needed to evaluate the impact of discontinuing antidepressant use during cancer treatment. This comprehensive overview provides insights for clinicians to help them make informed decisions regarding the prescription of antidepressants in the context of cancer treatment.

- National Cancer Institute. Depression (PDQ)-Health Professional Version. Updated July 25, 2024. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/feelings/depression-hp-pdq

- Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014;23(2):121-130. doi:10.1002/pon.3409

- Xiang X, An R, Gehlert S. Trends in antidepressant use among U.S. cancer survivors, 1999-2012. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):564. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500007

- Hartung TJ, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. The risk of being depressed is significantly higher in cancer patients than in the general population: Prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms across major cancer types. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:46-53. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.017

- Walker J, Holm Hansen C, Martin P, et al. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):895-900. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds575

- Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415. doi:10.1136/bmj.k1415

- Kisely S, Alotiby MKN, Protani MM, Soole R, Arnautovska U, Siskind D. Breast cancer treatment disparities in patients with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2023;32(5):651-662. doi:10.1002/pon.6120

- Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):57-71. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014

- Rodin G, Katz M, Lloyd N, Green E, Mackay JA, Wong RK. Treatment of depression in cancer patients. Curr Oncol. 2007;14(5):180-188. doi:10.3747/co.2007.146

- Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, Skirko MG, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(2):118-129. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.016

- Moradi Y, Dowran B, Sepandi M. The global prevalence of depression, suicide ideation, and attempts in the military forces: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):510. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2

- Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. 2014;348:g3596. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3596

- Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning--10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666-1668. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1408480

- Sheffler ZM, Patel P, Abdijadid S. Antidepressants. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated May 26, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538182/

- Miller JJ. Antidepressants, Part 1: 100 Years and Counting. Accessed April 4, 2025. Psychiatric Times. https:// www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/antidepressants-part-1-100-years-and-counting

- Hillhouse TM, Porter JH. A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(1):1-21. doi:10.1037/a0038550

- Mitchell PB, Mitchell MS. The management of depression. Part 2. The place of the new antidepressants. Aust Fam Physician. 1994;23(9):1771-1781.

- Sabri MA, Saber-Ayad MM. MAO Inhibitors. In: Stat- Pearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557395/

- Sub Laban T, Saadabadi A. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOI). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 17, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539848/

- Fiedorowicz JG, Swartz KL. The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):239-248. doi:10.1097/00131746-200407000-00005

- Flockhart DA. Dietary restrictions and drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: an update. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73 Suppl 1:17-24. doi:10.4088/JCP.11096su1c.03

- Moraczewski J, Awosika AO, Aedma KK. Tricyclic Antidepressants. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 17, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557791/

- Almasi A, Patel P, Meza CE. Doxepin. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated February 14, 2024. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542306/

- Thour A, Marwaha R. Amitriptyline. In: StatPearls. Stat- Pearls Publishing. Updated July 18, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537225/

- Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021

- Tesfaye S, Sloan G, Petrie J, et al. Comparison of amitriptyline supplemented with pregabalin, pregabalin supplemented with amitriptyline, and duloxetine supplemented with pregabalin for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (OPTION-DM): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised crossover trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10353):680- 690. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01472-6

- Farag HM, Yunusa I, Goswami H, Sultan I, Doucette JA, Eguale T. Comparison of amitriptyline and US Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and network metaanalysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2212939. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.12939

- Merwar G, Gibbons JR, Hosseini SA, Saadabadi A. Nortriptyline. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482214/

- Fayez R, Gupta V. Imipramine. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated May 22, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557656/

- Jilani TN, Gibbons JR, Faizy RM, Saadabadi A. Mirtazapine. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519059/

- Nutt DJ. Tolerability and safety aspects of mirtazapine. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17 Suppl 1:S37-S41. doi:10.1002/hup.388

- Gandotra K, Chen P, Jaskiw GE, Konicki PE, Strohl KP. Effective treatment of insomnia with mirtazapine attenuates concomitant suicidal ideation. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):901-902. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7142

- Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7(3):249-264. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00198.x

- Wang SM, Han C, Bahk WM, et al. Addressing the side effects of contemporary antidepressant drugs: a comprehensive review. Chonnam Med J. 2018;54(2):101-112. doi:10.4068/cmj.2018.54.2.101

- Huecker MR, Smiley A, Saadabadi A. Bupropion. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated April 9, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470212/

- Hsieh MT, Tseng PT, Wu YC, et al. Effects of different pharmacologic smoking cessation treatments on body weight changes and success rates in patients with nicotine dependence: a network meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(6):895- 905. doi:10.1111/obr.12835

- Hankosky ER, Bush HM, Dwoskin LP, et al. Retrospective analysis of health claims to evaluate pharmacotherapies with potential for repurposing: association of bupropion and stimulant use disorder remission. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:1292-1299.

- Livingstone-Banks J, Norris E, Hartmann-Boyce J, West R, Jarvis M, Hajek P. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019; 2(2):CD003999. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub5

- Clayton AH, Kingsberg SA, Goldstein I. Evaluation and management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Sex Med. 2018;6(2):59-74. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2018.01.004

- Verbeeck W, Bekkering GE, Van den Noortgate W, Kramers C. Bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10(10):CD009504. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009504.pub2

- Ng QX. A systematic review of the use of bupropion for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(2):112-116. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0124

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106-113. doi:10.4088/pcc.v07n0305

- Chu A, Wadhwa R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated May 1, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/

- Singh HK, Saadabadi A. Sertraline. In: StatPearls. Stat- Pearls Publishing. Updated February 13, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- MacQueen G, Born L, Steiner M. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline: its profile and use in psychiatric disorders. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7(1):1-24. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00188.x

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746-758. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5

- Nelson JC. The STAR*D study: a four-course meal that leaves us wanting more. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1864-1866. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1864

- Sharbaf Shoar N, Fariba KA, Padhy RK. Citalopram. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated November 7, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482222/

- Landy K, Rosani A, Estevez R. Escitalopram. In: Stat- Pearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated November 10, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557734/

- Cavanah LR, Ray P, Goldhirsh JL, Huey LY, Piper BJ. Rise of escitalopram and the fall of citalopram. medRxiv. Preprint published online May 8, 2023. doi:10.1101/2023.05.07.23289632

- Sohel AJ, Shutter MC, Patel P, Molla M. Fluoxetine. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 4, 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459223/

- Wong DT, Perry KW, Bymaster FP. Case history: the discovery of fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac). Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(9):764-774. doi:10.1038/nrd1821

- Shrestha P, Fariba KA, Abdijadid S. Paroxetine. In: Stat- Pearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 17, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526022/

- Naseeruddin R, Rosani A, Marwaha R. Desvenlafaxine. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 10, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534829

- Lieberman DZ, Massey SH. Desvenlafaxine in major depressive disorder: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evid. 2010;4:67-82. doi:10.2147/ce.s5998

- Withdrawal assessment report for Ellefore (desvenlafaxine). European Medicine Agency. 2009. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/withdrawal-report/withdrawal-assessment-report-ellefore_en.pdf

- Dhaliwal JS, Spurling BC, Molla M. Duloxetine. In: Stat- Pearls. Statpearls Publishing. Updated May 29, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549806/

- Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941-1967. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914

- Sommer C, Häuser W, Alten R, et al. Medikamentöse Therapie des Fibromyalgiesyndroms. Systematische Übersicht und Metaanalyse [Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline]. Schmerz. 2012;26(3):297-310. doi:10.1007/s00482-012-1172-2

- Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1758-1765. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166ebe

- Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, et al. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(9):1113-e88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x

- Singh D, Saadabadi A. Venlafaxine. In: StatPearls. StatePearls Publishing. Updated February 26, 2024. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535363/

- Sertraline and venlafaxine: new indication. Prevention of recurrent depression: no advance. Prescrire Int. 2005;14(75):19-20.

- Bruno A, Morabito P, S p i n a E , M u s c a t ello MRl. The role of levomilnacipran in the management of major depressive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Neuro pharmacol. 2016;14(2):191-199. doi:10.2174/1570159x14666151117122458

- Shin JJ, Saadabadi A. Trazodone. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated February 29, 2024. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470560/

- Khouzam HR. A review of trazodone use in psychiatric and medical conditions. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(1):140-148. doi:10.1080/00325481.2017.1249265

- Smales ET, Edwards BA, Deyoung PN, et al. Trazodone effects on obstructive sleep apnea and non-REM arousal threshold. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(5):758-764. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-399OC

- Eckert DJ, Malhotra A, Wellman A, White DP. Trazodone increases the respiratory arousal threshold in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and a low arousal threshold. Sleep. 2014;37(4):811-819. doi:10.5665/sleep.3596

- Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. The American Psychiat ric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

- Ruxton K, Woodman RJ, Mangoni AA. Drugs with anticholinergic effects and cognitive impairment, falls and allcause mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(2):209-220. doi:10.1111/bcp.12617

- Nefazodone. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Updated March 6, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548179/

- Drugs of Current Interest: Nefazodone. WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter:(1). 2003(1):7. https://web.archive.org/web/20150403165029/http:/apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4944e/3.html

- Choi S. Nefazodone (serzone) withdrawn because of hepatotoxicity. CMAJ. 2003;169(11):1187.

- Teva Nefazodone Statement. News release. Teva USA. December 20, 2021. Accessed April 4, 2025. https:// www.tevausa.com/news-and-media/press-releases/teva-nefazodone-statement/

- Levitan MN, Papelbaum M, Nardi AE. Profile of agomelatine and its potential in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1149- 1155. doi:10.2147/NDT.S67470

- Fu DJ, Ionescu DF, Li X, et al. Esketamine nasal spray for rapid reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms in patients who have active suicidal ideation with intent: double-blind, randomized study (ASPIRE I). J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19m13191. doi:10.4088/JCP.19m13191

- Iosifescu DV, Jones A, O’Gorman C, et al. Efficacy and safety of AXS-05 (dextromethorphan-bupropion) in patients with major depressive disorder: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial (GEMINI). J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(4): 21m14345. doi:10.4088/JCP.21m14345

- Luong TT, Powers CN, Reinhardt BJ, et al. Retrospective evaluation of drug-drug interactions with erlotinib and gefitinib use in the Military Health System. Fed Pract. 2023;40(Suppl 3):S24-S34. doi:10.12788/fp.0401

- Luong TT, Shou KJ, Reinhard BJ, Kigelman OF, Greenfield KM. Paclitaxel drug-drug interactions in the Military Health System. Fed Pract. 2024;41(Suppl 3):S70-S82. doi:10.12788/fp.0499

- Luong TT, Powers CN, Reinhardt BJ, Weina PJ. Preclinical drug-drug interactions (DDIs) of gefitinib with/without losartan and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov. 2022;3:100112. doi:10.1016/j.crphar.2022.100112

- Luong TT, McAnulty MJ, Evers DL, Reinhardt BJ, Weina PJ. Pre-clinical drug-drug interaction (DDI) of gefitinib or erlotinib with cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibiting drugs, fluoxetine and/or losartan. Curr Res Toxicol. 2021;2:217- 224. doi:10.1016/j.crtox.2021.05.006,

- Adamo M, Dickie L, Ruhl J. SEER program coding and staging manual 2016. National Cancer Institute; 2016. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/manuals/2016/SPCSM_2016_maindoc.pdf

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for oncology (ICD-O). 3rd ed, 1st revision. World Health Organization; 2013. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/96612

- Simon S. FDA approves Jelmyto (mitomycin gel) for urothelial cancer. American Cancer Society. April 20, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/latest-news/fda-approves-jelmyto-mitomycin-gel-for-urothelial-cancer.html

- Pantziarka P, Sukhatme V, Bouche G, Meheus L, Sukhatme VP. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)- diclofenac as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2016;10:610. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2016.610

- Choi S, Kim S, Park J, Lee SE, Kim C, Kang D. Diclofenac: a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug inducing cancer cell death by inhibiting microtubule polymerization and autophagy flux. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(5):1009. doi:10.3390/antiox11051009

- Tontonoz M. The ABCs of BCG: oldest approved immunotherapy gets new explanation. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. July 17, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.mskcc.org/news/oldest-approved-immunotherapy-gets-new-explanation

- Jordan VC. Tamoxifen as the first targeted long-term adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):R235-R246. doi:10.1530/ERC-14-0092

- Cole MP, Jones CT, Todd ID. A new anti-oestrogenic agent in late breast cancer. An early clinical appraisal of ICI46474. Br J Cancer. 1971;25(2):270-275. doi:10.1038/bjc.1971.33

- Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: a most unlikely pioneering medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(3):205-213. doi:10.1038/nrd1031

- Maximov PY, McDaniel RE, Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: Pioneering Medicine in Breast Cancer. Springer Basel; 2013. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-0348-0664-0

- Taxol (paclitaxel). Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2011. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020262s049lbl.pdf

- Abraxane (paclitaxel). Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021660s047lbl.pdf

- Tarceva (erlotinib). Prescribing information. OSI Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2016. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/021743s025lbl.pdf

- Docetaxel. Prescribing information. Sichuan Hyiyu Pharmaceutical Co.; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215813s000lbl.pdf

- Alimta (pemetrexed). Prescribing information. Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208419s004lbl.pdf

- Tagrisso (osimertinib). Prescribing information. Astra- Zeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/208065s021lbl.pdf

- Iressa (gefitinib). Prescribing information. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2018. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/206995s003lbl.pdf

- Kadcyla (ado-trastuzumab emtansine). Prescribing information. Genentech, Inc.; 2013. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/125427lbl.pdf

- Alecensa (alectinib). Prescribing information. Genetech, Inc.; 2017. Accessed April 4, 2025. https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/208434s003lbl.pdf

- Xalkori (crizotinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Laboratories; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/202570s033lbl.pdf

- Lorbrena (lorlatinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Laboratories; 2018. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210868s000lbl.pdf

- Alunbrig (brigatinib). Prescribing information. Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/208772s008lbl.pdf

- Rozlytrek (entrectinib). Prescribing information. Genentech, Inc.; 2019. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212725s000lbl.pdf

- Herceptin (trastuzumab). Prescribing information. Genentech, Inc.; 2010. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/103792s5250lbl.pdf

- Cybalta (duloxetine). Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2017. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/021427s049lbl.pdf

- Effexor XR (venlafaxine). Prescribing information. Pfizer Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/020699s112lbl.pdf

- Desyrel (trazodone hydrochloride). Prescribing information. Pragma Pharmaceuticals; 2017. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018207s032lbl.pdf

- Sertraline hydrochloride. Prescribing information. Almatica Pharma LLC; 2021. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215133s000lbl.pdf

- Remeron (mirtazapine). Prescribing information. Merck & Co. Inc; 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/020415s029,%20021208s019lbl.pdf

- Celexa (citalopram). Prescribing information. Allergan USA Inc; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/020822s041lbl.pdf

- information. GlaxoSmithKline; 2019. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/020358s066lbl.pdf

- Amitriptyline hydrochloride tablet. Prescribing information. Quality Care Products LLC; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/spl/data/0f12f50f-7087-46e7-a2e6-356b4c566c9f/0f12f50f-7087-46e7-a2e6-356b4c566c9f.xml

- Lexapro (escitalopram). Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2023. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/021323s055,021365s039lbl.pdf

- Fluoxetine. Prescribing information. Edgemont Pharmaceutical, LLC; 2017. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/202133s004s005lbl.pdf

- Paxil (paroxetine). Prescribing Information. Apotex Inc; 2021. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/020031s077lbl.pdf

- Pamelor (nortriptyline HCl). Prescribing information. Mallinckrodt, Inc; 2012. Accessed April 4, 2025. https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/018012s029,018013s061lbl.pdf

- Silenor (doxepin). Prescribing information. Currax Pharmaceuticals; 2020. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/022036s006lbl.pdf

- Tofranil-PM (imipramine pamote). Prescribing information. Mallinckrodt, Inc; 2014. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/017090s078lbl.pdf

- Norpramin (desipramine hydrochloride). Prescribing information. Sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; 2014. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/014399s069lbl.pdf

- Khedezla (desvenlafaxine). Prescribing information. Osmotical Pharmaceutical US LLC; 2019. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/204683s006lbl.pdf

- Nefazodone hydrochloride. Prescribing information. Bryant Ranch Prepack; 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/spl/data/0bd4c34a-4f43-4c84-8b98-1d074cba97d5/0bd4c34a-4f43-4c84-8b98-1d074cba97d5.xml

- Grassi L, Nanni MG, Rodin G, Li M, Caruso R. The use of antidepressants in oncology: a review and practical tips for oncologists. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(1):101-111. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx526

- Lee E, Park Y, Li D, Rodriguez-Fuguet A, Wang X, Zhang WC. Antidepressant use and lung cancer risk and survival: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Res Commun. 2023;3(6):1013-1025. doi:10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-23-0003

- Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):848 -856. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81

- Grattan A, Sullivan MD, Saunders KW, Campbell CI, Von Korff MR. Depression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic opioid therapy recipients with no history of substance abuse. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(4):304-311. doi:10.1370/afm.1371

- Cowan DT, Wilson-Barnett J, Griffiths P, Allan LG. A survey of chronic noncancer pain patients prescribed opioid analgesics. Pain Med. 2003;4(4):340-351. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2003.03038.x

- Breckenridge J, Clark JD. Patient characteristics associated with opioid versus nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug management of chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2003;4(6):344-350. doi:10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00638-2

- Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b99f35

- Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, DeVries A, Braden JB, Martin BC. Risks for possible and probable opioid misuse among recipients of chronic opioid therapy in commercial and medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2010;150(2):332-339. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.020

- Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006

- Haddad P. Do antidepressants have any potential to cause addiction? J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(3):300- 307. doi:10.1177/026988119901300321

- Lakeview Health Staff. America’s most abused antidepressants. Lakeview Health. January 24, 2004. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.lakeviewhealth.com/blog/us-most-abused-antidepressants/

- Greenhouse Treatment Center Editorial Staff. Addiction to antidepressants: is it possible? America Addiction Centers: Greenhouse Treatment Center. Updated April 23, 2024. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://greenhousetreatment.com/prescription-medication/antidepressants/

Cancer patients experience depression at rates > 5 times that of the general population.1-11 Despite an increase in palliative care use, depression rates continued to rise.2-4 Between 5% to 16% of outpatients, 4% to 14% of inpatients, and up to 49% of patients receiving palliative care experience depression.5 This issue also impacts families and caregivers.1 A 2021 meta-analysis found that 23% of active military personnel and 20% of veterans experience depression.11

Antidepressants approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) target the serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine systems and include boxed warnings about an increased risk of suicidal thoughts in adults aged 18 to 24 years.12,13 These medications are categorized into several classes: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs), norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), serotonin receptor modulators (SRMs), serotonin-melatonin receptor antagonists (SMRAs), and N—methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists (NMDARAs).14,15 The first FDA-approved antidepressants, iproniazid (an MAOI) and imipramine (a TCA) laid the foundation for the development of newer classes like SSRIs and SNRIs.15-17

Older antidepressants such as MAOIs and TCAs are used less due to their adverse effects (AEs) and drug interactions. MAOIs, such as iproniazid, selegiline, moclobemide, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and phenelzine, have numerous AEs and drug interactions, making them unsuitable for first- or second-line treatment of depression.14,18-21 TCAs such as doxepin, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, trimipramine, protriptyline, maprotiline, and amoxapine have a narrow therapeutic index requiring careful monitoring for signs of toxicity such as QRS widening, tremors, or confusion. Despite the issues, TCAs are generally classified as second-line agents for major depressive disorder (MDD). TCAs have off-label uses for migraine prophylaxis, treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), insomnia, and chronic pain management first-line.14,22-29

Newer antidepressants, including TeCAs and NDRIs, are typically more effective, but also come with safety concerns. TeCAs like mirtazapine interact with several medications, including MAOIs, serotonin-increasing drugs, alcohol, cannabidiol, and marijuana. Mirtazapine is FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in adults. It is also used off-label to treat insomnia, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), headaches, and migraines. Compared to other antidepressants, mirtazapine is effective for all stages of depression and addresses a broad range of related symptoms.14,30-34 NDRIs, such as bupropion, also interact with various medications, including MAOIs, other antidepressants, stimulants, and alcohol. Bupropion is FDA-approved for smoking cessation and to treat depression and SAD. It is also used off-label for depression- related bipolar disorder or sexual dysfunction, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and obesity.14,35-42

SSRIs, SNRIs, and SRMs should be used with caution. SSRIs such as sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine are first-line treatments for depression and various psychiatric disorders due to their safety and efficacy. Common AEs of SSRIs include sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, weight changes, and gastrointestinal (GI) issues. SSRIs can prolong the QT interval, posing a risk of life-threatening arrhythmia, and may interact with other medications, necessitating treatment adjustments. The FDA approved SSRIs for MDD, GAD, bulimia nervosa, bipolar depression, OCD, panic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and SAD. Off-label uses include binge eating disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, fibromyalgia, premature ejaculation, paraphilias, autism, Raynaud phenomenon, and vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Among SSRIs, sertraline and escitalopram are noted for their effectiveness and tolerability.14,43-53

SNRIs, including duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran, and levomilnacipran, may increase bleeding risk, especially when taken with blood thinners. They can also elevate blood pressure, which may worsen if combined with stimulants. SNRIs may interact with other medications that affect serotonin levels, increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome when taken with triptans, pain medications, or other antidepressants.14 Desvenlafaxine has been approved by the FDA (but not by the European Medicines Agency).54-56 Duloxetine is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression, neuropathic pain, anxiety disorders, fibromyalgia, and musculoskeletal disorders. It is used off-label to treat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and stress urinary incontinence.57-61 Venlafaxine is FDA-approved for depression, SAD, and panic disorder, and is prescribed off-label to treat ADHD, neuropathy, fibromyalgia, cataplexy, and PTSD, either alone or in combination with other medications.62,63 Milnacipran is not approved for MDD; levomilnacipran received approval in 2013.64

SRMs such as trazodone, nefazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine also function as serotonin reuptake inhibitors.14,15 Trazodone is FDA-approved for MDD. It has been used off-label to treat anxiety, Alzheimer disease, substance misuse, bulimia nervosa, insomnia, fibromyalgia, and PTSD when first-line SSRIs are ineffective. A notable AE of trazodone is orthostatic hypotension, which can lead to dizziness and increase the risk of falls, especially in geriatric patients.65-70 Nefazodone was discontinued in Europe in 2003 due to rare cases of liver toxicity but remains available in the US.71-74 Vilazodone and vortioxetine are FDA-approved.

The latest classes of antidepressants include SMRAs and NMDARAs.14 Agomelatine, an SMRA, was approved in Europe in 2009 but rejected by the FDA in 2011 due to liver toxicity.75 NMDARAs like esketamine and a combination of dextromethorphan and bupropion received FDA approval in 2019 and 2022, respectively.76,77

This retrospective study analyzes noncancer drugs used during systemic chemotherapy based on a dataset of 14 antineoplastic agents. It sought to identify the most dispensed noncancer drug groups, discuss findings, compare patients with and without antidepressant prescriptions, and examine trends in antidepressant use from 2002 to 2023. This analysis expands on prior research.78-81

Methods

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and ensured compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol. The Joint Pathology Center (JPC) of the US Department of Defense (DoD) Cancer Registry Program and Military Health System (MHS) data experts from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) provided data for the analysis.

Data Sources

The JPC DoD Cancer Registry Program contains data from 1998 to 2024. CAPER and PDTS are part of the MHS Data Repository/Management Analysis and Reporting Tool database. Each observation in CAPER represents an ambulatory encounter at a military treatment facility (MTF). CAPER records are available from 2003 to 2024. PDTS records are available from 2002 to 2004. Each observation in PDTS represents a prescription filled for an MHS beneficiary, excluding those filled at international civilian pharmacies and inpatient pharmacy prescriptions.

This cross-sectional analysis requested data extraction for specific cancer drugs from the DoD Cancer Registry, focusing on treatment details, diagnosis dates, patient demographics, and physicians’ comments on AEs. After identifying patients, CAPER was used to identify additional health conditions. PDTS was used to compile a list of prescription medications filled during systemic cancer treatment or < 2 years postdiagnosis.

The 2016 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Coding and Staging Manual and International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, 1st revision, were used to decode disease and cancer types.82,83 Data sorting and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel. The percentage for the total was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the subgroup divided by the total number of patients or data variables. To compare the mean number of dispensed antidepressants to those without antidepressants, a 2-tailed, 2-sample z test was used to calculate the P value and determine statistical significance (P < .05) using socscistatistics.com.

Data were extracted 3 times between 2021 and 2023. The initial 2021 protocol focused on erlotinib and gefitinib. A modified protocol in 2022 added paclitaxel, cisplatin, docetaxel, pemetrexed, and crizotinib; further modification in 2023 included 8 new antineoplastic agents and 2 anticoagulants. Sotorasib has not been prescribed in the MHS, and JPC lacks records for noncancer drugs. The 2023 dataset comprised 2210 patients with cancer treated with 14 antineoplastic agents; 2104 had documented diagnoses and 2113 had recorded prescriptions. Data for erlotinib, gefitinib, and paclitaxel have been published previously.78,79

Results

Of 2113 patients with recorded prescriptions, 1297 patients (61.4%) received 109 cancer drugs, including 96 antineoplastics, 7 disease-modifying antirheumatic agents, 4 biologic response modifiers, and 2 calcitonin gene-related peptides. Fourteen antineoplastic agents had complete data from JPC, while others were noted for combination therapies or treatment switches from the PDTS (Table 1). Seventy-six cancer drugs were prescribed with antidepressants in 489 patients (eAppendix).

The JPC provided 2242 entries for 2210 patients, ranging in age from 2 months to 88 years (mean, 56 years), documenting treatment from September 1988 to January 2023. Thirty-two patients had duplicate entries due to multiple cancer locations or occurrences. Of the 2242 patients, 1541 (68.7%) were aged > 50 years, 975 patients (43.5%) had cancers that were stage III or IV, and 1267 (56.5%) had cancers that were stage 0, I, II, or not applicable/unknown. There were 51 different types of cancer: breast, lung, testicular, endometrial, and ovarian were most common (n ≥ 100 patients). Forty-two cancer types were documented among 750 patients prescribed antidepressants (Table 2).

The CAPER database recorded 8882 unique diagnoses for 2104 patients, while PDTS noted 1089 unique prescriptions within 273 therapeutic codes for 2113 patients. Nine therapeutic codes (opiate agonists, adrenals, cathartics-laxatives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, antihistamines for GI conditions, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, analgesics and antipyretic miscellanea, antineoplastic agents, and proton-pump inhibitors) and 8 drugs (dexamethasone, prochlorperazine, ondansetron, docusate, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, oxycodone, and polyethylene glycol 3350) were associated with > 1000 patients (≥ 50%). Patients had between 1 and 275 unique health conditions and filled 1 to 108 prescriptions. The mean (SD) number of diagnoses and prescriptions was 50 (28) and 29 (12), respectively. Of the 273 therapeutic codes, 30 groups were analyzed, with others categorized into miscellaneous groups such as lotions, vaccines, and devices. Significant differences in mean number of prescriptions were found for patients taking antidepressants compared to those not (P < .05), except for anticonvulsants and antipsychotics (P = .12 and .09, respectively) (Table 3).

Antidepressants

Of the 2113 patients with recorded prescriptions, 750 (35.5%) were dispensed 17 different antidepressants. Among these 17 antidepressants, 183 (8.7%) patients received duloxetine, 158 (7.5%) received venlafaxine, 118 (5.6%) received trazodone, and 107 (5.1%) received sertraline (Figure 1, Table 4). Of the 750 patients, 509 (67.9%) received 1 antidepressant, 168 (22.4%) received 2, 60 (8.0%) received 3, and 13 (1.7%) received > 3. Combinations varied, but only duloxetine and trazodone were prescribed to > 10 patients.

Antidepressants were prescribed annually at an overall mean (SD) rate of 23% (5%) from 2003 to 2022 (Figure 2). Patients on antidepressants during systemic therapy had a greater number of diagnosed medical conditions and received more prescription medications compared to those not taking antidepressants (P < .001) (Figure 3). The 745 patients taking antidepressants in CAPER data had between 1 and 275 diagnosed medical issues, with a mean (SD) of 55 (31) vs a range of 1 to 209 and a mean (SD) of 46 (26) for the 1359 patients not taking antidepressants. The 750 patients on antidepressants in PDTS data had between 8 and 108 prescriptions dispensed, with a mean (SD) of 32 (12), vs a range of 1 to 65 prescriptions and a mean (SD) of 29 (12) for 1363 patients not taking antidepressants.

Discussion

The JPC DoD Cancer Registry includes information on cancer types, stages, treatment regimens, and physicians’ notes, while noncancer drugs are sourced from the PDTS database. The pharmacy uses a different documentation system, leading to varied classifications.

Database reliance has its drawbacks. For example, megestrol is coded as a cancer drug, although it’s primarily used for endometrial or gynecologic cancers. Many drugs have multiple therapeutic codes assigned to them, including 10 antineoplastic agents: diclofenac, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), megestrol acetate, tamoxifen, anastrozole, letrozole, leuprolide, goserelin, degarelix, and fluorouracil. Diclofenac, BCG, and mitomycin have been repurposed for cancer treatment.84-87 From 2003 to 2023, diclofenac was prescribed to 350 patients for mild-to-moderate pain, with only 2 patients receiving it for cancer in 2018. FDA-approved for bladder cancer in 1990, BCG was prescribed for cancer treatment for 1 patient in 2021 after being used for vaccines between 2003 and 2018. Tamoxifen, used for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer from 2004 to 2017 with 53 patients, switched to estrogen agonist-antagonists from 2017 to 2023 with 123 patients. Only a few of the 168 patients were prescribed tamoxifen using both codes.88-91 Anastrozole and letrozole were coded as antiestrogens for 7 and 18 patients, respectively, while leuprolide and goserelin were coded as gonadotropins for 59 and 18 patients. Degarelix was coded as antigonadotropins, fluorouracil as skin and mucous membrane agents miscellaneous, and megestrol acetate as progestins for 7, 6, and 3 patients, respectively. Duloxetine was given to 186 patients, primarily for depression from 2005 to 2023, with 7 patients treated for fibromyalgia from 2022 to 2023.

Antidepressants Observed

Tables 1 and 5 provide insight into the FDA approval of 14 antineoplastics and antidepressants and their CYP metabolic pathways.92-122 In Table 4, the most prescribed antidepressant classes are SNRIs, SRMs, SSRIs, TeCAs, NDRIs, and TCAs. This trend highlights a preference for newer medications with weak CYP inhibition. A total of 349 patients were prescribed SSRIs, 343 SNRIs, 119 SRMs, 109 TCAs, 83 TeCAs, and 79 NDRIs. MAOIs, SMRAs, and NMDARAs were not observed in this dataset. While there are instances of dextromethorphan-bupropion and sertraline-escitalopram being dispensed together, it remains unclear whether these were NMDARA combinations.

Among the 14 specific antineoplastic agents, 10 are metabolized by CYP isoenzymes, primarily CYP3A4. Duloxetine neither inhibits nor is metabolized by CYP3A4, a reason it is often recommended, following venlafaxine.