User login

Multistate opioid crackdown nets indictment against seven physicians

In coordination with federal and state law enforcement, the DOJ charged the defendants for their involvement in the illegal distribution of opioids. At the time that they were charged with the alleged offenses, 12 of the defendants were medical professionals.

The 12 persons in eight federal districts across the country distributed more than 115 million controlled substances, including buprenorphine, clonazepam, dextroamphetamine-amphetamine, hydrocodone, morphine sulfate, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and Suboxone, per the DOJ.

“Doctors and health care professionals are entrusted with prescribing medicine responsibly and in the best interests of their patients. Today’s takedown targets medical providers across the country whose greed drove them to abandon this responsibility in favor of criminal profits,” said Anne Milgram, administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Medical professionals, others across six states charged

One former nurse, one business manager, and one individual who practiced medicine without a medical credential are among those listed in the indictment. These include the following:

- Eskender Getachew, MD, a Columbus, Ohio, sleep medicine specialist, was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances outside the use of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical practice.

- Charles Kistler, DO, an Upper Arlington, Ohio, family practice physician, was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances for unlawful prescribing at Midtown Family Practice Clinic in Columbus.

- Yogeshwar Gil, MBBS, a Manchester, Tenn., family medicine doctor and owner of a medical practice, was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances and maintaining a drug-involved premises. Dr. Gil was charged in connection with an alleged scheme to distribute opioids and Suboxone outside the usual course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

- Contessa Holley, RN, a Pulaski, Tenn., former nurse and clinical director, was charged with wire fraud, aggravated identity theft, and possession of a controlled substance with intent to distribute. She’s alleged to be connected with a scheme to unlawfully obtain opioids by filling fraudulent prescriptions in the names of current and former patients who were in hospice. The indictment alleged that Ms. Holley used the patients’ hospice benefits to cover the opioids’ costs while keeping the drugs for her own use and for further distribution.

- Francene Aretha Gayle, MD, an Orlando, Fla., physician, was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances, conspiracy to commit health care fraud, health care fraud, and several substantive counts of illegally issuing opioid prescriptions. Dr. Gayle was charged along with Schara Monique Davis, a Huntsville, Ala.–based business manager. Per the indictment, Dr. Gayle and Ms. Davis operated three medical clinics in Alabama, where Dr. Gayle was the sole physician. The medical clinics billed health insurers for millions of dollars in patient visits that Dr. Gayle had supposedly conducted but during which she was allegedly absent from the clinics; other staff members conducted the visits instead. It’s alleged that Dr. Gayle presigned prescriptions for opioids that were given to patients.

- Robert Taffet, MD, a Haddonfield, N.J., orthopedic surgeon and owner of a medical practice in Sicklerville, N.J., was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances. The indictment alleges that he falsified patient files to state that he interacted with patients when he didn’t and that he issued prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances without assessing the patients in person or by telemedicine. It’s alleged that Dr. Taffett issued prescriptions for more than 179,000 pills that were dispensed by New Jersey pharmacies between April 2020 and December 2021.

- Hau La, MD, a Brentwood, Tenn., family medicine physician and the operator of Absolute Medical Care in Smyrna, Tenn., was charged with sixteen counts of unlawful distribution of a controlled substance. The physician is alleged to have unlawfully prescribed opioids to eight patients outside the usual course of practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

- Frederick De Mesa, of War, W.Va., practiced as a physician and used a DEA registration number that allowed him to prescribe controlled substances. Mr. De Mesa prescribed these substances without a medical license and didn’t have an active DEA registration number, according to the indictment.

- Loey Kousa, a former internist from Paintsville, Ky., was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances, healthcare fraud, and making false statements in connection with the delivery of health care services. The indictment alleges that the former physician issued prescriptions for opioids outside the usual course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose in his capacity as owner and operator of East KY Clinic in Paintsville. He is alleged to have issued the unlawful prescriptions for patients whose treatments were covered by taxpayer-funded programs such as Medicare and Medicaid; he also billed these programs for medically unnecessary procedures for these patients.

Also included in the indictment were Jay Sadrinia, DMD, a Villa Hills, Ky., dentist, who was charged with four counts of illegal distribution of oxycodone and morphine sulfate and one count of illegal distribution of morphine sulfate that resulted in death or serious bodily injury; and Casey Kelleher, an owner-operator of Neighborhood Pharmacy in Boynton Beach, Fla., who allegedly sold large amounts of oxycodone and hydromorphone on the black market.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Center for Program Integrity has taken six administrative actions against health care providers for their alleged involvement in these offenses, per the DOJ’s announcement.

“Patient care and safety are top priorities for us, and CMS has taken administrative action against six providers to protect critical resources entrusted to Medicare while also safeguarding people with Medicare,” said CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

“These actions to combat fraud, waste, and abuse in our federal programs would not be possible without the close and successful partnership of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Justice, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General,” she added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In coordination with federal and state law enforcement, the DOJ charged the defendants for their involvement in the illegal distribution of opioids. At the time that they were charged with the alleged offenses, 12 of the defendants were medical professionals.

The 12 persons in eight federal districts across the country distributed more than 115 million controlled substances, including buprenorphine, clonazepam, dextroamphetamine-amphetamine, hydrocodone, morphine sulfate, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and Suboxone, per the DOJ.

“Doctors and health care professionals are entrusted with prescribing medicine responsibly and in the best interests of their patients. Today’s takedown targets medical providers across the country whose greed drove them to abandon this responsibility in favor of criminal profits,” said Anne Milgram, administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Medical professionals, others across six states charged

One former nurse, one business manager, and one individual who practiced medicine without a medical credential are among those listed in the indictment. These include the following:

- Eskender Getachew, MD, a Columbus, Ohio, sleep medicine specialist, was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances outside the use of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical practice.

- Charles Kistler, DO, an Upper Arlington, Ohio, family practice physician, was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances for unlawful prescribing at Midtown Family Practice Clinic in Columbus.

- Yogeshwar Gil, MBBS, a Manchester, Tenn., family medicine doctor and owner of a medical practice, was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances and maintaining a drug-involved premises. Dr. Gil was charged in connection with an alleged scheme to distribute opioids and Suboxone outside the usual course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

- Contessa Holley, RN, a Pulaski, Tenn., former nurse and clinical director, was charged with wire fraud, aggravated identity theft, and possession of a controlled substance with intent to distribute. She’s alleged to be connected with a scheme to unlawfully obtain opioids by filling fraudulent prescriptions in the names of current and former patients who were in hospice. The indictment alleged that Ms. Holley used the patients’ hospice benefits to cover the opioids’ costs while keeping the drugs for her own use and for further distribution.

- Francene Aretha Gayle, MD, an Orlando, Fla., physician, was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances, conspiracy to commit health care fraud, health care fraud, and several substantive counts of illegally issuing opioid prescriptions. Dr. Gayle was charged along with Schara Monique Davis, a Huntsville, Ala.–based business manager. Per the indictment, Dr. Gayle and Ms. Davis operated three medical clinics in Alabama, where Dr. Gayle was the sole physician. The medical clinics billed health insurers for millions of dollars in patient visits that Dr. Gayle had supposedly conducted but during which she was allegedly absent from the clinics; other staff members conducted the visits instead. It’s alleged that Dr. Gayle presigned prescriptions for opioids that were given to patients.

- Robert Taffet, MD, a Haddonfield, N.J., orthopedic surgeon and owner of a medical practice in Sicklerville, N.J., was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances. The indictment alleges that he falsified patient files to state that he interacted with patients when he didn’t and that he issued prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances without assessing the patients in person or by telemedicine. It’s alleged that Dr. Taffett issued prescriptions for more than 179,000 pills that were dispensed by New Jersey pharmacies between April 2020 and December 2021.

- Hau La, MD, a Brentwood, Tenn., family medicine physician and the operator of Absolute Medical Care in Smyrna, Tenn., was charged with sixteen counts of unlawful distribution of a controlled substance. The physician is alleged to have unlawfully prescribed opioids to eight patients outside the usual course of practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

- Frederick De Mesa, of War, W.Va., practiced as a physician and used a DEA registration number that allowed him to prescribe controlled substances. Mr. De Mesa prescribed these substances without a medical license and didn’t have an active DEA registration number, according to the indictment.

- Loey Kousa, a former internist from Paintsville, Ky., was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances, healthcare fraud, and making false statements in connection with the delivery of health care services. The indictment alleges that the former physician issued prescriptions for opioids outside the usual course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose in his capacity as owner and operator of East KY Clinic in Paintsville. He is alleged to have issued the unlawful prescriptions for patients whose treatments were covered by taxpayer-funded programs such as Medicare and Medicaid; he also billed these programs for medically unnecessary procedures for these patients.

Also included in the indictment were Jay Sadrinia, DMD, a Villa Hills, Ky., dentist, who was charged with four counts of illegal distribution of oxycodone and morphine sulfate and one count of illegal distribution of morphine sulfate that resulted in death or serious bodily injury; and Casey Kelleher, an owner-operator of Neighborhood Pharmacy in Boynton Beach, Fla., who allegedly sold large amounts of oxycodone and hydromorphone on the black market.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Center for Program Integrity has taken six administrative actions against health care providers for their alleged involvement in these offenses, per the DOJ’s announcement.

“Patient care and safety are top priorities for us, and CMS has taken administrative action against six providers to protect critical resources entrusted to Medicare while also safeguarding people with Medicare,” said CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

“These actions to combat fraud, waste, and abuse in our federal programs would not be possible without the close and successful partnership of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Justice, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General,” she added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In coordination with federal and state law enforcement, the DOJ charged the defendants for their involvement in the illegal distribution of opioids. At the time that they were charged with the alleged offenses, 12 of the defendants were medical professionals.

The 12 persons in eight federal districts across the country distributed more than 115 million controlled substances, including buprenorphine, clonazepam, dextroamphetamine-amphetamine, hydrocodone, morphine sulfate, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and Suboxone, per the DOJ.

“Doctors and health care professionals are entrusted with prescribing medicine responsibly and in the best interests of their patients. Today’s takedown targets medical providers across the country whose greed drove them to abandon this responsibility in favor of criminal profits,” said Anne Milgram, administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Medical professionals, others across six states charged

One former nurse, one business manager, and one individual who practiced medicine without a medical credential are among those listed in the indictment. These include the following:

- Eskender Getachew, MD, a Columbus, Ohio, sleep medicine specialist, was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances outside the use of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical practice.

- Charles Kistler, DO, an Upper Arlington, Ohio, family practice physician, was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances for unlawful prescribing at Midtown Family Practice Clinic in Columbus.

- Yogeshwar Gil, MBBS, a Manchester, Tenn., family medicine doctor and owner of a medical practice, was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances and maintaining a drug-involved premises. Dr. Gil was charged in connection with an alleged scheme to distribute opioids and Suboxone outside the usual course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

- Contessa Holley, RN, a Pulaski, Tenn., former nurse and clinical director, was charged with wire fraud, aggravated identity theft, and possession of a controlled substance with intent to distribute. She’s alleged to be connected with a scheme to unlawfully obtain opioids by filling fraudulent prescriptions in the names of current and former patients who were in hospice. The indictment alleged that Ms. Holley used the patients’ hospice benefits to cover the opioids’ costs while keeping the drugs for her own use and for further distribution.

- Francene Aretha Gayle, MD, an Orlando, Fla., physician, was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances, conspiracy to commit health care fraud, health care fraud, and several substantive counts of illegally issuing opioid prescriptions. Dr. Gayle was charged along with Schara Monique Davis, a Huntsville, Ala.–based business manager. Per the indictment, Dr. Gayle and Ms. Davis operated three medical clinics in Alabama, where Dr. Gayle was the sole physician. The medical clinics billed health insurers for millions of dollars in patient visits that Dr. Gayle had supposedly conducted but during which she was allegedly absent from the clinics; other staff members conducted the visits instead. It’s alleged that Dr. Gayle presigned prescriptions for opioids that were given to patients.

- Robert Taffet, MD, a Haddonfield, N.J., orthopedic surgeon and owner of a medical practice in Sicklerville, N.J., was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully distribute controlled substances. The indictment alleges that he falsified patient files to state that he interacted with patients when he didn’t and that he issued prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances without assessing the patients in person or by telemedicine. It’s alleged that Dr. Taffett issued prescriptions for more than 179,000 pills that were dispensed by New Jersey pharmacies between April 2020 and December 2021.

- Hau La, MD, a Brentwood, Tenn., family medicine physician and the operator of Absolute Medical Care in Smyrna, Tenn., was charged with sixteen counts of unlawful distribution of a controlled substance. The physician is alleged to have unlawfully prescribed opioids to eight patients outside the usual course of practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

- Frederick De Mesa, of War, W.Va., practiced as a physician and used a DEA registration number that allowed him to prescribe controlled substances. Mr. De Mesa prescribed these substances without a medical license and didn’t have an active DEA registration number, according to the indictment.

- Loey Kousa, a former internist from Paintsville, Ky., was charged with unlawful distribution of controlled substances, healthcare fraud, and making false statements in connection with the delivery of health care services. The indictment alleges that the former physician issued prescriptions for opioids outside the usual course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose in his capacity as owner and operator of East KY Clinic in Paintsville. He is alleged to have issued the unlawful prescriptions for patients whose treatments were covered by taxpayer-funded programs such as Medicare and Medicaid; he also billed these programs for medically unnecessary procedures for these patients.

Also included in the indictment were Jay Sadrinia, DMD, a Villa Hills, Ky., dentist, who was charged with four counts of illegal distribution of oxycodone and morphine sulfate and one count of illegal distribution of morphine sulfate that resulted in death or serious bodily injury; and Casey Kelleher, an owner-operator of Neighborhood Pharmacy in Boynton Beach, Fla., who allegedly sold large amounts of oxycodone and hydromorphone on the black market.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Center for Program Integrity has taken six administrative actions against health care providers for their alleged involvement in these offenses, per the DOJ’s announcement.

“Patient care and safety are top priorities for us, and CMS has taken administrative action against six providers to protect critical resources entrusted to Medicare while also safeguarding people with Medicare,” said CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

“These actions to combat fraud, waste, and abuse in our federal programs would not be possible without the close and successful partnership of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Justice, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General,” she added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Surgery handoffs still a risky juncture in care – but increasing communication can help

It involved a 70-year-old man who had a history of prostate cancer, obstructive sleep apnea, and hernias. In January, he had a surgery for hernia repair. On the 3rd day after the procedure, he was transferred to the hospital medicine service at about 9 p.m. and was on a patient-controlled pump for pain and had abdominal drains. Because of the extensive surgery and because he had begun to walk shortly after the procedure, he wasn’t on thrombosis prevention medication, Dr. Merli explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The day after his transfer he was walking with a physical therapist when he became short of breath, his oxygen saturation dropped, and his heart rate soared. Bilateral pulmonary emboli were found, along with thrombosis in the right leg.

What was remarkable, Dr. Merli noted, was what the patient’s medical record was lacking.

He added, “I think if we start looking at this at our sites, we may find out that communication needs to be improved, and I believe standardized.”

This situation underscores the continuing need to refine handoffs between surgery and hospital medicine, a point in care that is primed for potential errors, the other panelists noted during the session.

Most important information is often not communicated

A 2010 study in pediatrics that looked at intern-to-intern handoffs found that the most important piece of information wasn’t communicated successfully 60% of the time – in other words, more often than not, the person on the receiving end didn’t really understand that crucial part of the scenario. Since then, the literature has been regularly populated with studies attempting to refine handoff procedures.

Lily Ackermann, MD, hospitalist and clinical associate professor of medicine at Jefferson, said in the session that hospitalists need to be sure to reach out to surgery at important junctures in care.

“I would say the No. 1 biggest mistake we make is not calling the surgery attending directly when clinical questions arise,” she said. “I think this is very important – attending [physician in hospital medicine] to attending [physician in surgery].”

Murray Cohen, MD, director of acute care surgery at Jefferson, said he shared that concern.

“We want to be called, we want to be called for our patients,” he said in the session. “And we’re upset when you don’t call for our patients.”

Hospitalists should discuss blood loss, pain management, management of drains, deep vein thrombosis prevention, nutrition, infectious disease concerns, and timing of vaccines post procedure, Dr. Ackermann said during the presentation,

The panelists also emphasized that understanding the follow-up care that surgery was planning after a procedure is important, and to not just expect surgeons to actively follow a patient. They also reminded hospitalists to look at the wounds and make sure they understand how to handle the wounds going forward. Plus, when transferring a patient to surgery, hospitalists should understand when getting someone to surgery is urgent and not to order unnecessary tests as a formality when time is of the essence, they said.

IPASS: a formalized handoff process

The panelists all spoke highly of a formalized handoff process known as IPASS. This acronym reminds physicians to ask specific questions.

The I represents illness severity and calls for asking: “Is the patient stable or unstable?

The P stands for patient summary and is meant to prompt physicians to seek details about the procedure.

The A is for action list, which is meant to remind the physician to get the post-op plan for neurological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and other areas.

The first S is for situational awareness, and calls for asking: What is the biggest concern over the next 24 hours?

The final S represents synthesis by the receiver, prompting a physician to summarize the information he or she has received about the patient.

Natalie Margules, MD, a clinical instructor and hospitalist at Jefferson who did not present in the session, reiterated the value of the IPASS system. Before it was used for handoffs, she said, “I was never taught anything formalized – basically, just ‘Tell them what’s important.’

Dr. Margules noted that she considers the framework’s call for the synthesis to be one of it most useful parts.

Dr. Merli, Dr. Ackermann, and Dr. Cohen reported no relevant financial disclosures.

It involved a 70-year-old man who had a history of prostate cancer, obstructive sleep apnea, and hernias. In January, he had a surgery for hernia repair. On the 3rd day after the procedure, he was transferred to the hospital medicine service at about 9 p.m. and was on a patient-controlled pump for pain and had abdominal drains. Because of the extensive surgery and because he had begun to walk shortly after the procedure, he wasn’t on thrombosis prevention medication, Dr. Merli explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The day after his transfer he was walking with a physical therapist when he became short of breath, his oxygen saturation dropped, and his heart rate soared. Bilateral pulmonary emboli were found, along with thrombosis in the right leg.

What was remarkable, Dr. Merli noted, was what the patient’s medical record was lacking.

He added, “I think if we start looking at this at our sites, we may find out that communication needs to be improved, and I believe standardized.”

This situation underscores the continuing need to refine handoffs between surgery and hospital medicine, a point in care that is primed for potential errors, the other panelists noted during the session.

Most important information is often not communicated

A 2010 study in pediatrics that looked at intern-to-intern handoffs found that the most important piece of information wasn’t communicated successfully 60% of the time – in other words, more often than not, the person on the receiving end didn’t really understand that crucial part of the scenario. Since then, the literature has been regularly populated with studies attempting to refine handoff procedures.

Lily Ackermann, MD, hospitalist and clinical associate professor of medicine at Jefferson, said in the session that hospitalists need to be sure to reach out to surgery at important junctures in care.

“I would say the No. 1 biggest mistake we make is not calling the surgery attending directly when clinical questions arise,” she said. “I think this is very important – attending [physician in hospital medicine] to attending [physician in surgery].”

Murray Cohen, MD, director of acute care surgery at Jefferson, said he shared that concern.

“We want to be called, we want to be called for our patients,” he said in the session. “And we’re upset when you don’t call for our patients.”

Hospitalists should discuss blood loss, pain management, management of drains, deep vein thrombosis prevention, nutrition, infectious disease concerns, and timing of vaccines post procedure, Dr. Ackermann said during the presentation,

The panelists also emphasized that understanding the follow-up care that surgery was planning after a procedure is important, and to not just expect surgeons to actively follow a patient. They also reminded hospitalists to look at the wounds and make sure they understand how to handle the wounds going forward. Plus, when transferring a patient to surgery, hospitalists should understand when getting someone to surgery is urgent and not to order unnecessary tests as a formality when time is of the essence, they said.

IPASS: a formalized handoff process

The panelists all spoke highly of a formalized handoff process known as IPASS. This acronym reminds physicians to ask specific questions.

The I represents illness severity and calls for asking: “Is the patient stable or unstable?

The P stands for patient summary and is meant to prompt physicians to seek details about the procedure.

The A is for action list, which is meant to remind the physician to get the post-op plan for neurological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and other areas.

The first S is for situational awareness, and calls for asking: What is the biggest concern over the next 24 hours?

The final S represents synthesis by the receiver, prompting a physician to summarize the information he or she has received about the patient.

Natalie Margules, MD, a clinical instructor and hospitalist at Jefferson who did not present in the session, reiterated the value of the IPASS system. Before it was used for handoffs, she said, “I was never taught anything formalized – basically, just ‘Tell them what’s important.’

Dr. Margules noted that she considers the framework’s call for the synthesis to be one of it most useful parts.

Dr. Merli, Dr. Ackermann, and Dr. Cohen reported no relevant financial disclosures.

It involved a 70-year-old man who had a history of prostate cancer, obstructive sleep apnea, and hernias. In January, he had a surgery for hernia repair. On the 3rd day after the procedure, he was transferred to the hospital medicine service at about 9 p.m. and was on a patient-controlled pump for pain and had abdominal drains. Because of the extensive surgery and because he had begun to walk shortly after the procedure, he wasn’t on thrombosis prevention medication, Dr. Merli explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The day after his transfer he was walking with a physical therapist when he became short of breath, his oxygen saturation dropped, and his heart rate soared. Bilateral pulmonary emboli were found, along with thrombosis in the right leg.

What was remarkable, Dr. Merli noted, was what the patient’s medical record was lacking.

He added, “I think if we start looking at this at our sites, we may find out that communication needs to be improved, and I believe standardized.”

This situation underscores the continuing need to refine handoffs between surgery and hospital medicine, a point in care that is primed for potential errors, the other panelists noted during the session.

Most important information is often not communicated

A 2010 study in pediatrics that looked at intern-to-intern handoffs found that the most important piece of information wasn’t communicated successfully 60% of the time – in other words, more often than not, the person on the receiving end didn’t really understand that crucial part of the scenario. Since then, the literature has been regularly populated with studies attempting to refine handoff procedures.

Lily Ackermann, MD, hospitalist and clinical associate professor of medicine at Jefferson, said in the session that hospitalists need to be sure to reach out to surgery at important junctures in care.

“I would say the No. 1 biggest mistake we make is not calling the surgery attending directly when clinical questions arise,” she said. “I think this is very important – attending [physician in hospital medicine] to attending [physician in surgery].”

Murray Cohen, MD, director of acute care surgery at Jefferson, said he shared that concern.

“We want to be called, we want to be called for our patients,” he said in the session. “And we’re upset when you don’t call for our patients.”

Hospitalists should discuss blood loss, pain management, management of drains, deep vein thrombosis prevention, nutrition, infectious disease concerns, and timing of vaccines post procedure, Dr. Ackermann said during the presentation,

The panelists also emphasized that understanding the follow-up care that surgery was planning after a procedure is important, and to not just expect surgeons to actively follow a patient. They also reminded hospitalists to look at the wounds and make sure they understand how to handle the wounds going forward. Plus, when transferring a patient to surgery, hospitalists should understand when getting someone to surgery is urgent and not to order unnecessary tests as a formality when time is of the essence, they said.

IPASS: a formalized handoff process

The panelists all spoke highly of a formalized handoff process known as IPASS. This acronym reminds physicians to ask specific questions.

The I represents illness severity and calls for asking: “Is the patient stable or unstable?

The P stands for patient summary and is meant to prompt physicians to seek details about the procedure.

The A is for action list, which is meant to remind the physician to get the post-op plan for neurological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and other areas.

The first S is for situational awareness, and calls for asking: What is the biggest concern over the next 24 hours?

The final S represents synthesis by the receiver, prompting a physician to summarize the information he or she has received about the patient.

Natalie Margules, MD, a clinical instructor and hospitalist at Jefferson who did not present in the session, reiterated the value of the IPASS system. Before it was used for handoffs, she said, “I was never taught anything formalized – basically, just ‘Tell them what’s important.’

Dr. Margules noted that she considers the framework’s call for the synthesis to be one of it most useful parts.

Dr. Merli, Dr. Ackermann, and Dr. Cohen reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

Burnout ‘highly prevalent’ in psychiatrists across the globe

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

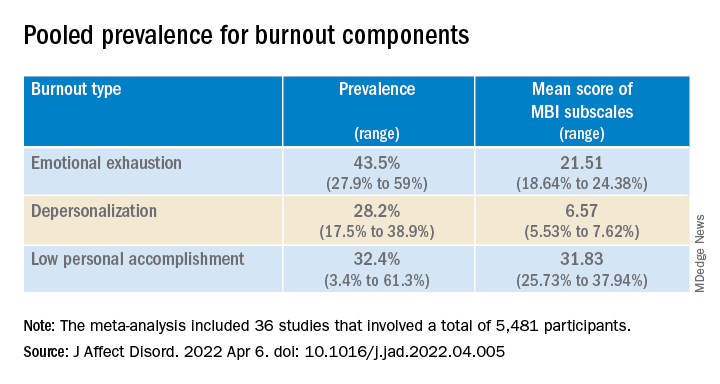

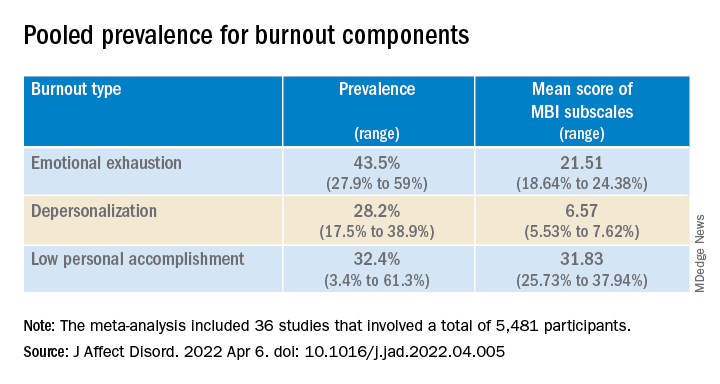

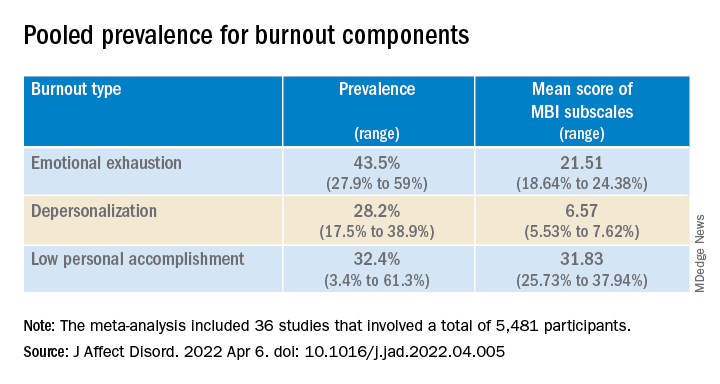

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Abortion politics lead to power struggles over family planning grants

BOZEMAN, Mont. – In a busy downtown coffee shop, a drawing of a ski lift with intrauterine devices for chairs draws the eyes of sleepy customers getting their morning underway with a caffeine jolt.

The flyer touts the services of Bridgercare, a nonprofit reproductive health clinic a few miles up the road. The clinic offers wellness exams, birth control, and LGBTQ+ services – and, starting in April, it oversees the state’s multimillion-dollar share of federal family planning program funding.

In March, Bridgercare beat out the state health department to become administrator of Montana’s $2.3 million Title X program, which helps pay for family planning and preventive health services. The organization applied for the grant because its leaders were concerned about a new state law that sought to restrict which local providers are funded.

What is happening in Montana is the latest example of an ongoing power struggle between nonprofits and conservative-leaning states over who receives federal family planning money. That has intensified in recent years as the Title X program has increasingly become entangled with the politics of abortion.

This year, the federal government set aside $257 million for family planning and preventive care. The providers that get that funding often serve families with low incomes, and Title X is one of the few federal programs in which people without legal permission to be in the United States can participate.

“The program permeates into communities that otherwise would be unreached by public health efforts,” said Rebecca Kreitzer, an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services controlled the distribution of the state’s Title X funds for decades. Bridgercare sought the administrator role to circumvent a Republican-sponsored law passed last year that required the state to prioritize the money for local health departments and federally qualified health centers. That would have put the nonprofit – which doesn’t provide abortion procedures – and similar organizations at the bottom of the list. The law also banned clinics that perform abortions from receiving Title X funds from the state health department.

Bridgercare Executive Director Stephanie McDowell said the group applied for the grant to try to protect the program from decisions coming out of the state capitol. “Because of the politicization of Title X, we’re seeing how it’s run, swinging back and forth based on partisan leadership,” Ms. McDowell said.

A U.S. Department of Health & Human Services spokesperson, Tara Broido, didn’t answer a question about whether the agency intentionally awarded grants to nonprofits to avoid state politics. Instead, she said in a statement that applicants were evaluated in a competitive process by a panel of independent reviewers based on criteria to deliver high-quality, client-centered services.

Federal law prohibits the money from being used to perform abortions. But it can cover other services provided by groups that offer abortions – the largest and best-known by far is Planned Parenthood. In recent years, conservative politicians have tried to keep such providers from receiving Title X funding.

In some cases, contraception has entered the debate around which family planning services government should help fund. Some abortion opponents have raised concerns that long-lasting forms of birth control, such as IUDs, lead to abortions. Those claims are disputed by reproductive health experts.

In 2019, the Trump administration introduced several new rules for Title X, including disqualifying from receiving the funding family planning clinics that also offered abortion services or referrals. Many clinics across the nation left the program instead of conforming to the rules. Simultaneously, the spread of COVID-19 interrupted routine care. The number of patients served by Title X plummeted.

The Biden administration reversed most of those rules, including allowing providers with abortion services back into the Title X program. States also try to influence the funding’s reach, either through legislation or budget rules.

The current Title X funding cycle is 5 years, and the amount of money available each year could shift based on the state’s network of providers or federal budget changes. Jon Ebelt, a spokesperson for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, didn’t answer when asked whether the state planned to reapply to administer the funding in 2027. He said the department was disappointed with the Biden administration’s “refusal” to renew the state’s funding.

“We recognize, however, that recent proabortion federal rule changes have distorted Title X and conflict with Montana law,” he said.

Conservative states have been tangling with nonprofits and the federal government over Title X funding for more than a decade. In 2011, during the Obama administration, Texas whittled down the state’s family planning spending and prioritized sending the federal money to general primary care providers over reproductive health clinics. As a result, 25% of family planning clinics in Texas closed. In 2013, a nonprofit now called Every Body Texas joined the competition to distribute the state’s Title X dollars and won.

“Filling and rebuilding those holes have taken this last decade, essentially,” said Berna Mason, director of service delivery improvement for Every Body Texas.

In 2019, the governor of Nebraska proposed a budget that would have prohibited the money from going to any organization that provided abortions or referred patients for abortions outside of an emergency. It also would have required that funding recipients be legally and financially separate from such clinics, a restriction that would have gone further than the Trump administration’s rules. Afterward, a family planning council won the right to administer Title X money.

In 2017, the nonprofit Arizona Family Health Partnership lost its status as that state’s only Title X administrator when the state health department was given 25% of the funding to deliver to providers. That came after Arizona lawmakers ordered the department to apply for the funds and distribute them first to state- or county-owned clinics, with the remaining money going to primary care facilities. The change was backed by groups that were opposed to abortion, and reproductive health care providers saw it as an attempt to weaken clinics that offer abortion services.

However, the state left nearly all the money it received untouched, and although it’s still required by law to apply for Title X funding, it hasn’t received a portion of the grant since.

Bré Thomas, CEO of Arizona Family Health Partnership, said that, even though the nonprofit is the sole administrator of the Title X funding again, the threat remains that some or all could be taken away because of politics. “We’re at the will of who’s in charge,” Ms. Thomas said.

Nonprofits say they have an advantage over state agencies in expanding services because they have more flexibility in fundraising and fewer administrative hurdles.

In April, Mississippi nonprofit Converge took over administration of Title X funds, a role the state had held for decades. The organization’s founders said they weren’t worried that conservative politicians would restrict access to services but simply believed they could do a better job. “Service quality was very low, and it was very hard to get appointments,” said cofounder Danielle Lampton.

A Mississippi State Department of Health spokesperson, Liz Sharlot, said the agency looks forward to working with Converge.

In Montana, Bridgercare plans to restore funding to Planned Parenthood clinics that have been cut off from the program since 2019, recruit more health centers to participate, and expand the program’s reach in rural, frontier, and tribal communities using telehealth services, Ms. McDowell said.

The organization’s goal is to increase the number of patients benefiting from the federal program by at least 10% in each year of the 5-year grant cycle. The clinic also plans to apply to keep its Title X role beyond this grant.

“In 5 years, our grant application should be a clear front-runner for funding,” she said. “It’s less about ‘How do we beat someone in 5 years?’ And more about ‘How do we grow this program to serve patients?’”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

BOZEMAN, Mont. – In a busy downtown coffee shop, a drawing of a ski lift with intrauterine devices for chairs draws the eyes of sleepy customers getting their morning underway with a caffeine jolt.

The flyer touts the services of Bridgercare, a nonprofit reproductive health clinic a few miles up the road. The clinic offers wellness exams, birth control, and LGBTQ+ services – and, starting in April, it oversees the state’s multimillion-dollar share of federal family planning program funding.

In March, Bridgercare beat out the state health department to become administrator of Montana’s $2.3 million Title X program, which helps pay for family planning and preventive health services. The organization applied for the grant because its leaders were concerned about a new state law that sought to restrict which local providers are funded.

What is happening in Montana is the latest example of an ongoing power struggle between nonprofits and conservative-leaning states over who receives federal family planning money. That has intensified in recent years as the Title X program has increasingly become entangled with the politics of abortion.

This year, the federal government set aside $257 million for family planning and preventive care. The providers that get that funding often serve families with low incomes, and Title X is one of the few federal programs in which people without legal permission to be in the United States can participate.

“The program permeates into communities that otherwise would be unreached by public health efforts,” said Rebecca Kreitzer, an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services controlled the distribution of the state’s Title X funds for decades. Bridgercare sought the administrator role to circumvent a Republican-sponsored law passed last year that required the state to prioritize the money for local health departments and federally qualified health centers. That would have put the nonprofit – which doesn’t provide abortion procedures – and similar organizations at the bottom of the list. The law also banned clinics that perform abortions from receiving Title X funds from the state health department.

Bridgercare Executive Director Stephanie McDowell said the group applied for the grant to try to protect the program from decisions coming out of the state capitol. “Because of the politicization of Title X, we’re seeing how it’s run, swinging back and forth based on partisan leadership,” Ms. McDowell said.

A U.S. Department of Health & Human Services spokesperson, Tara Broido, didn’t answer a question about whether the agency intentionally awarded grants to nonprofits to avoid state politics. Instead, she said in a statement that applicants were evaluated in a competitive process by a panel of independent reviewers based on criteria to deliver high-quality, client-centered services.

Federal law prohibits the money from being used to perform abortions. But it can cover other services provided by groups that offer abortions – the largest and best-known by far is Planned Parenthood. In recent years, conservative politicians have tried to keep such providers from receiving Title X funding.

In some cases, contraception has entered the debate around which family planning services government should help fund. Some abortion opponents have raised concerns that long-lasting forms of birth control, such as IUDs, lead to abortions. Those claims are disputed by reproductive health experts.

In 2019, the Trump administration introduced several new rules for Title X, including disqualifying from receiving the funding family planning clinics that also offered abortion services or referrals. Many clinics across the nation left the program instead of conforming to the rules. Simultaneously, the spread of COVID-19 interrupted routine care. The number of patients served by Title X plummeted.

The Biden administration reversed most of those rules, including allowing providers with abortion services back into the Title X program. States also try to influence the funding’s reach, either through legislation or budget rules.

The current Title X funding cycle is 5 years, and the amount of money available each year could shift based on the state’s network of providers or federal budget changes. Jon Ebelt, a spokesperson for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, didn’t answer when asked whether the state planned to reapply to administer the funding in 2027. He said the department was disappointed with the Biden administration’s “refusal” to renew the state’s funding.

“We recognize, however, that recent proabortion federal rule changes have distorted Title X and conflict with Montana law,” he said.

Conservative states have been tangling with nonprofits and the federal government over Title X funding for more than a decade. In 2011, during the Obama administration, Texas whittled down the state’s family planning spending and prioritized sending the federal money to general primary care providers over reproductive health clinics. As a result, 25% of family planning clinics in Texas closed. In 2013, a nonprofit now called Every Body Texas joined the competition to distribute the state’s Title X dollars and won.

“Filling and rebuilding those holes have taken this last decade, essentially,” said Berna Mason, director of service delivery improvement for Every Body Texas.

In 2019, the governor of Nebraska proposed a budget that would have prohibited the money from going to any organization that provided abortions or referred patients for abortions outside of an emergency. It also would have required that funding recipients be legally and financially separate from such clinics, a restriction that would have gone further than the Trump administration’s rules. Afterward, a family planning council won the right to administer Title X money.

In 2017, the nonprofit Arizona Family Health Partnership lost its status as that state’s only Title X administrator when the state health department was given 25% of the funding to deliver to providers. That came after Arizona lawmakers ordered the department to apply for the funds and distribute them first to state- or county-owned clinics, with the remaining money going to primary care facilities. The change was backed by groups that were opposed to abortion, and reproductive health care providers saw it as an attempt to weaken clinics that offer abortion services.

However, the state left nearly all the money it received untouched, and although it’s still required by law to apply for Title X funding, it hasn’t received a portion of the grant since.

Bré Thomas, CEO of Arizona Family Health Partnership, said that, even though the nonprofit is the sole administrator of the Title X funding again, the threat remains that some or all could be taken away because of politics. “We’re at the will of who’s in charge,” Ms. Thomas said.

Nonprofits say they have an advantage over state agencies in expanding services because they have more flexibility in fundraising and fewer administrative hurdles.

In April, Mississippi nonprofit Converge took over administration of Title X funds, a role the state had held for decades. The organization’s founders said they weren’t worried that conservative politicians would restrict access to services but simply believed they could do a better job. “Service quality was very low, and it was very hard to get appointments,” said cofounder Danielle Lampton.

A Mississippi State Department of Health spokesperson, Liz Sharlot, said the agency looks forward to working with Converge.

In Montana, Bridgercare plans to restore funding to Planned Parenthood clinics that have been cut off from the program since 2019, recruit more health centers to participate, and expand the program’s reach in rural, frontier, and tribal communities using telehealth services, Ms. McDowell said.

The organization’s goal is to increase the number of patients benefiting from the federal program by at least 10% in each year of the 5-year grant cycle. The clinic also plans to apply to keep its Title X role beyond this grant.

“In 5 years, our grant application should be a clear front-runner for funding,” she said. “It’s less about ‘How do we beat someone in 5 years?’ And more about ‘How do we grow this program to serve patients?’”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

BOZEMAN, Mont. – In a busy downtown coffee shop, a drawing of a ski lift with intrauterine devices for chairs draws the eyes of sleepy customers getting their morning underway with a caffeine jolt.

The flyer touts the services of Bridgercare, a nonprofit reproductive health clinic a few miles up the road. The clinic offers wellness exams, birth control, and LGBTQ+ services – and, starting in April, it oversees the state’s multimillion-dollar share of federal family planning program funding.

In March, Bridgercare beat out the state health department to become administrator of Montana’s $2.3 million Title X program, which helps pay for family planning and preventive health services. The organization applied for the grant because its leaders were concerned about a new state law that sought to restrict which local providers are funded.

What is happening in Montana is the latest example of an ongoing power struggle between nonprofits and conservative-leaning states over who receives federal family planning money. That has intensified in recent years as the Title X program has increasingly become entangled with the politics of abortion.

This year, the federal government set aside $257 million for family planning and preventive care. The providers that get that funding often serve families with low incomes, and Title X is one of the few federal programs in which people without legal permission to be in the United States can participate.

“The program permeates into communities that otherwise would be unreached by public health efforts,” said Rebecca Kreitzer, an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services controlled the distribution of the state’s Title X funds for decades. Bridgercare sought the administrator role to circumvent a Republican-sponsored law passed last year that required the state to prioritize the money for local health departments and federally qualified health centers. That would have put the nonprofit – which doesn’t provide abortion procedures – and similar organizations at the bottom of the list. The law also banned clinics that perform abortions from receiving Title X funds from the state health department.

Bridgercare Executive Director Stephanie McDowell said the group applied for the grant to try to protect the program from decisions coming out of the state capitol. “Because of the politicization of Title X, we’re seeing how it’s run, swinging back and forth based on partisan leadership,” Ms. McDowell said.

A U.S. Department of Health & Human Services spokesperson, Tara Broido, didn’t answer a question about whether the agency intentionally awarded grants to nonprofits to avoid state politics. Instead, she said in a statement that applicants were evaluated in a competitive process by a panel of independent reviewers based on criteria to deliver high-quality, client-centered services.

Federal law prohibits the money from being used to perform abortions. But it can cover other services provided by groups that offer abortions – the largest and best-known by far is Planned Parenthood. In recent years, conservative politicians have tried to keep such providers from receiving Title X funding.

In some cases, contraception has entered the debate around which family planning services government should help fund. Some abortion opponents have raised concerns that long-lasting forms of birth control, such as IUDs, lead to abortions. Those claims are disputed by reproductive health experts.

In 2019, the Trump administration introduced several new rules for Title X, including disqualifying from receiving the funding family planning clinics that also offered abortion services or referrals. Many clinics across the nation left the program instead of conforming to the rules. Simultaneously, the spread of COVID-19 interrupted routine care. The number of patients served by Title X plummeted.

The Biden administration reversed most of those rules, including allowing providers with abortion services back into the Title X program. States also try to influence the funding’s reach, either through legislation or budget rules.

The current Title X funding cycle is 5 years, and the amount of money available each year could shift based on the state’s network of providers or federal budget changes. Jon Ebelt, a spokesperson for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, didn’t answer when asked whether the state planned to reapply to administer the funding in 2027. He said the department was disappointed with the Biden administration’s “refusal” to renew the state’s funding.

“We recognize, however, that recent proabortion federal rule changes have distorted Title X and conflict with Montana law,” he said.

Conservative states have been tangling with nonprofits and the federal government over Title X funding for more than a decade. In 2011, during the Obama administration, Texas whittled down the state’s family planning spending and prioritized sending the federal money to general primary care providers over reproductive health clinics. As a result, 25% of family planning clinics in Texas closed. In 2013, a nonprofit now called Every Body Texas joined the competition to distribute the state’s Title X dollars and won.

“Filling and rebuilding those holes have taken this last decade, essentially,” said Berna Mason, director of service delivery improvement for Every Body Texas.

In 2019, the governor of Nebraska proposed a budget that would have prohibited the money from going to any organization that provided abortions or referred patients for abortions outside of an emergency. It also would have required that funding recipients be legally and financially separate from such clinics, a restriction that would have gone further than the Trump administration’s rules. Afterward, a family planning council won the right to administer Title X money.

In 2017, the nonprofit Arizona Family Health Partnership lost its status as that state’s only Title X administrator when the state health department was given 25% of the funding to deliver to providers. That came after Arizona lawmakers ordered the department to apply for the funds and distribute them first to state- or county-owned clinics, with the remaining money going to primary care facilities. The change was backed by groups that were opposed to abortion, and reproductive health care providers saw it as an attempt to weaken clinics that offer abortion services.

However, the state left nearly all the money it received untouched, and although it’s still required by law to apply for Title X funding, it hasn’t received a portion of the grant since.

Bré Thomas, CEO of Arizona Family Health Partnership, said that, even though the nonprofit is the sole administrator of the Title X funding again, the threat remains that some or all could be taken away because of politics. “We’re at the will of who’s in charge,” Ms. Thomas said.

Nonprofits say they have an advantage over state agencies in expanding services because they have more flexibility in fundraising and fewer administrative hurdles.

In April, Mississippi nonprofit Converge took over administration of Title X funds, a role the state had held for decades. The organization’s founders said they weren’t worried that conservative politicians would restrict access to services but simply believed they could do a better job. “Service quality was very low, and it was very hard to get appointments,” said cofounder Danielle Lampton.