User login

Use your court awareness to go faster in practice

Have you ever had a nightmare you’re running late? Recently I dreamt I was seeing patients on a ship, a little cruiser like the ones that give you tours of Boston Harbor, with low ceilings and narrow iron stairs. My nurse stood where what would have been the coffee and danish window. My first patient was a newborn (this was a nightmare, in case you forgot) who was enormous. She had a big belly and spindly legs that hung off the table. Uniform, umbilicated papules and pustules covered her body. At the sight of her, terror ripped through me – no clue. I rushed to the doctor lounge (nice the ship had one) and flipped channels on a little TV mounted on the ceiling. Suddenly, my nurse burst in, she was frantic because dozens of angry adults and crying children were crammed in the hallway. Apparently, I had been watching TV for hours and my whole clinic was now backed up.

Running-late dreams are common and usually relate to real life. For us, the clinic has been busy lately. Vaccinated patients are returning after a year with their skin cancers that have flourished and psoriasis covering them like kudzu. In particular, they “see the floor” better than other docs and therefore make continual adjustments to stay on pace. At its essence, they are using super-powers of observation to make decisions. It reminded me of a podcast about court awareness and great passers in basketball like the Charlotte Hornets’ LaMelo Ball and NBA great, Bill Bradley.

Bradley had an extraordinary ability to know where all the players were, and where they would be, at any given moment. He spent years honing this skill, noticing details in store windows as he stared straight ahead walking down a street. It’s reported his peripheral vision extended 5%-15% wider than average and he used it to gather more information and to process it more quickly. As a result he made outstanding decisions and fast, ultimately earning a spot in the Hall of Fame in Springfield.

Hall of Fame clinicians similarly take in a wider view than others and process that information quickly. They know how much time they have spent in the room, sense the emotional needs of the patient and anticipate the complexity of the problem. They quickly get to the critical questions and examinations that will make the diagnosis. They know the experience and skill of their medical assistant. They know the level of difficulty and even the temperament of patients who lie ahead on the schedule. All this is processed and used in moment-to-moment decision making. Do I sit down or stand up now? Can I excise this today, or reschedule? Do I ask another question? Do I step out of this room and see another in parallel while this biopsy is set up? And always, do I dare ask about grandkids or do I politely move on?

By broadening out their vision, they optimize their clinic, providing the best possible service, whether the day is busy or slow. I found their economy of motion also means they are less exhausted at the end of the day. I bet if when they dream of being on a ship, they’re sipping a Mai Tai, lounging on the deck.

For more on Bill Bradley and becoming more observant about your surroundings, you might appreciate the following:

www.newyorker.com/magazine/1965/01/23/a-sense-of-where-you-are and freakonomics.com/podcast/nsq-mindfulness/

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Have you ever had a nightmare you’re running late? Recently I dreamt I was seeing patients on a ship, a little cruiser like the ones that give you tours of Boston Harbor, with low ceilings and narrow iron stairs. My nurse stood where what would have been the coffee and danish window. My first patient was a newborn (this was a nightmare, in case you forgot) who was enormous. She had a big belly and spindly legs that hung off the table. Uniform, umbilicated papules and pustules covered her body. At the sight of her, terror ripped through me – no clue. I rushed to the doctor lounge (nice the ship had one) and flipped channels on a little TV mounted on the ceiling. Suddenly, my nurse burst in, she was frantic because dozens of angry adults and crying children were crammed in the hallway. Apparently, I had been watching TV for hours and my whole clinic was now backed up.

Running-late dreams are common and usually relate to real life. For us, the clinic has been busy lately. Vaccinated patients are returning after a year with their skin cancers that have flourished and psoriasis covering them like kudzu. In particular, they “see the floor” better than other docs and therefore make continual adjustments to stay on pace. At its essence, they are using super-powers of observation to make decisions. It reminded me of a podcast about court awareness and great passers in basketball like the Charlotte Hornets’ LaMelo Ball and NBA great, Bill Bradley.

Bradley had an extraordinary ability to know where all the players were, and where they would be, at any given moment. He spent years honing this skill, noticing details in store windows as he stared straight ahead walking down a street. It’s reported his peripheral vision extended 5%-15% wider than average and he used it to gather more information and to process it more quickly. As a result he made outstanding decisions and fast, ultimately earning a spot in the Hall of Fame in Springfield.

Hall of Fame clinicians similarly take in a wider view than others and process that information quickly. They know how much time they have spent in the room, sense the emotional needs of the patient and anticipate the complexity of the problem. They quickly get to the critical questions and examinations that will make the diagnosis. They know the experience and skill of their medical assistant. They know the level of difficulty and even the temperament of patients who lie ahead on the schedule. All this is processed and used in moment-to-moment decision making. Do I sit down or stand up now? Can I excise this today, or reschedule? Do I ask another question? Do I step out of this room and see another in parallel while this biopsy is set up? And always, do I dare ask about grandkids or do I politely move on?

By broadening out their vision, they optimize their clinic, providing the best possible service, whether the day is busy or slow. I found their economy of motion also means they are less exhausted at the end of the day. I bet if when they dream of being on a ship, they’re sipping a Mai Tai, lounging on the deck.

For more on Bill Bradley and becoming more observant about your surroundings, you might appreciate the following:

www.newyorker.com/magazine/1965/01/23/a-sense-of-where-you-are and freakonomics.com/podcast/nsq-mindfulness/

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Have you ever had a nightmare you’re running late? Recently I dreamt I was seeing patients on a ship, a little cruiser like the ones that give you tours of Boston Harbor, with low ceilings and narrow iron stairs. My nurse stood where what would have been the coffee and danish window. My first patient was a newborn (this was a nightmare, in case you forgot) who was enormous. She had a big belly and spindly legs that hung off the table. Uniform, umbilicated papules and pustules covered her body. At the sight of her, terror ripped through me – no clue. I rushed to the doctor lounge (nice the ship had one) and flipped channels on a little TV mounted on the ceiling. Suddenly, my nurse burst in, she was frantic because dozens of angry adults and crying children were crammed in the hallway. Apparently, I had been watching TV for hours and my whole clinic was now backed up.

Running-late dreams are common and usually relate to real life. For us, the clinic has been busy lately. Vaccinated patients are returning after a year with their skin cancers that have flourished and psoriasis covering them like kudzu. In particular, they “see the floor” better than other docs and therefore make continual adjustments to stay on pace. At its essence, they are using super-powers of observation to make decisions. It reminded me of a podcast about court awareness and great passers in basketball like the Charlotte Hornets’ LaMelo Ball and NBA great, Bill Bradley.

Bradley had an extraordinary ability to know where all the players were, and where they would be, at any given moment. He spent years honing this skill, noticing details in store windows as he stared straight ahead walking down a street. It’s reported his peripheral vision extended 5%-15% wider than average and he used it to gather more information and to process it more quickly. As a result he made outstanding decisions and fast, ultimately earning a spot in the Hall of Fame in Springfield.

Hall of Fame clinicians similarly take in a wider view than others and process that information quickly. They know how much time they have spent in the room, sense the emotional needs of the patient and anticipate the complexity of the problem. They quickly get to the critical questions and examinations that will make the diagnosis. They know the experience and skill of their medical assistant. They know the level of difficulty and even the temperament of patients who lie ahead on the schedule. All this is processed and used in moment-to-moment decision making. Do I sit down or stand up now? Can I excise this today, or reschedule? Do I ask another question? Do I step out of this room and see another in parallel while this biopsy is set up? And always, do I dare ask about grandkids or do I politely move on?

By broadening out their vision, they optimize their clinic, providing the best possible service, whether the day is busy or slow. I found their economy of motion also means they are less exhausted at the end of the day. I bet if when they dream of being on a ship, they’re sipping a Mai Tai, lounging on the deck.

For more on Bill Bradley and becoming more observant about your surroundings, you might appreciate the following:

www.newyorker.com/magazine/1965/01/23/a-sense-of-where-you-are and freakonomics.com/podcast/nsq-mindfulness/

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Internists’ patient visits rebound to near pre-COVID norms: Pay down slightly from previous year

Internists are seeing only 3% fewer patients than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic (72 per week on average now vs. 74 before the pandemic). Comparatively, for pediatricians, patient volume remains down 18%. Dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and orthopedists report that visits are down by about 15%.

The number of hours worked also rebounded for internists. In fact, some report working slightly more hours now than they did before the pandemic (52 hours a week, up from 50).

Pay for internists continues to hover near the bottom of the scale among specialties. In this year’s Medscape Internist Compensation Report 2021, internists averaged $248,000, down from $251,000 last year. Pediatricians were the lowest paid, at $221,000, followed by family physicians, at $236,000. Plastic surgeons made the most, at $526,000, followed by orthopedists, at $511,000.

It helped to be self-employed. These internists made $276,000 on average, compared with $238,000 for their employed counterparts.

Half say pay is fair

Internists are also near the bottom among specialists who feel they are fairly compensated. As in last year’s survey, just more than half of internists (52%) said they felt that they were fairly paid this year. By comparison, 79% of oncologists reported they were fairly compensated, which is on the high end regarding satisfaction, but only 44% of infectious diseases specialists felt that way.

Some indicators in the survey responses may help explain the dissatisfaction.

Internists are near the top in time spent on paperwork. On average, they spent 19.7 hours on paperwork and administration this year, up slightly from 18.5 last year. Infectious disease physicians spent the most time on those tasks (24.2 hours a week), and anesthesiologists spent the fewest, at 10.1 hours per week.

Administrative work was among many frustrations internists reported. The following are the top five most challenging aspects of the job, according to the respondents:

- Having so many rules and regulations (24%)

- Having to work long hours (16%)

- Dealing with difficult patients (16%)

- Working with electronic health records systems (11%)

- Danger/risk associated with treating COVID-19 patients (10%)

Conversely, the most rewarding aspects were “gratitude/relationships with patients” (31%); “knowing that I’m making the world a better place” (26%); and “being very good at what I do” (20%).

More than one-third lost income

More than one-third of internists (36%) reported that they lost some income during the past year.

Among those who lost income, 81% said they expect income to return to prepandemic levels within 3 years. Half of that group expected the rebound would come within the next year.

Slightly more than one-third of internists said they would participate in the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS), and 12% said they would participate in advanced alternative payment models. The rest either said they would participate in neither, or they hadn’t decided.

“The stakes for the Quality Payment Program – the program that incorporates MIPS – are high, with a 9% penalty applied to all Medicare reimbursement for failure to participate,” says Elizabeth Woodcock, MBA, CPC, president of the physician practice consulting firm Woodcock and Associates, in Atlanta, Georgia.

“With margins already slim,” she told this news organization, “most physicians can’t afford this massive penalty.”

If they could choose again, most internists (76%) said they would choose medicine, which was almost the same number as physicians overall who would pick medicine again. Oncologists (88%) and ophthalmologists (87%) were the specialists most likely to choose medicine again. Those in physical medicine and rehabilitation were least likely to choose medicine again, at 67%.

But asked about their specialty, internists’ enthusiasm decreased. Only 68% said that they would make that same choice again.

That was up considerably, however, from the 2015 survey: For that year, only 25% said they would choose internal medicine again.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Internists are seeing only 3% fewer patients than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic (72 per week on average now vs. 74 before the pandemic). Comparatively, for pediatricians, patient volume remains down 18%. Dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and orthopedists report that visits are down by about 15%.

The number of hours worked also rebounded for internists. In fact, some report working slightly more hours now than they did before the pandemic (52 hours a week, up from 50).

Pay for internists continues to hover near the bottom of the scale among specialties. In this year’s Medscape Internist Compensation Report 2021, internists averaged $248,000, down from $251,000 last year. Pediatricians were the lowest paid, at $221,000, followed by family physicians, at $236,000. Plastic surgeons made the most, at $526,000, followed by orthopedists, at $511,000.

It helped to be self-employed. These internists made $276,000 on average, compared with $238,000 for their employed counterparts.

Half say pay is fair

Internists are also near the bottom among specialists who feel they are fairly compensated. As in last year’s survey, just more than half of internists (52%) said they felt that they were fairly paid this year. By comparison, 79% of oncologists reported they were fairly compensated, which is on the high end regarding satisfaction, but only 44% of infectious diseases specialists felt that way.

Some indicators in the survey responses may help explain the dissatisfaction.

Internists are near the top in time spent on paperwork. On average, they spent 19.7 hours on paperwork and administration this year, up slightly from 18.5 last year. Infectious disease physicians spent the most time on those tasks (24.2 hours a week), and anesthesiologists spent the fewest, at 10.1 hours per week.

Administrative work was among many frustrations internists reported. The following are the top five most challenging aspects of the job, according to the respondents:

- Having so many rules and regulations (24%)

- Having to work long hours (16%)

- Dealing with difficult patients (16%)

- Working with electronic health records systems (11%)

- Danger/risk associated with treating COVID-19 patients (10%)

Conversely, the most rewarding aspects were “gratitude/relationships with patients” (31%); “knowing that I’m making the world a better place” (26%); and “being very good at what I do” (20%).

More than one-third lost income

More than one-third of internists (36%) reported that they lost some income during the past year.

Among those who lost income, 81% said they expect income to return to prepandemic levels within 3 years. Half of that group expected the rebound would come within the next year.

Slightly more than one-third of internists said they would participate in the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS), and 12% said they would participate in advanced alternative payment models. The rest either said they would participate in neither, or they hadn’t decided.

“The stakes for the Quality Payment Program – the program that incorporates MIPS – are high, with a 9% penalty applied to all Medicare reimbursement for failure to participate,” says Elizabeth Woodcock, MBA, CPC, president of the physician practice consulting firm Woodcock and Associates, in Atlanta, Georgia.

“With margins already slim,” she told this news organization, “most physicians can’t afford this massive penalty.”

If they could choose again, most internists (76%) said they would choose medicine, which was almost the same number as physicians overall who would pick medicine again. Oncologists (88%) and ophthalmologists (87%) were the specialists most likely to choose medicine again. Those in physical medicine and rehabilitation were least likely to choose medicine again, at 67%.

But asked about their specialty, internists’ enthusiasm decreased. Only 68% said that they would make that same choice again.

That was up considerably, however, from the 2015 survey: For that year, only 25% said they would choose internal medicine again.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Internists are seeing only 3% fewer patients than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic (72 per week on average now vs. 74 before the pandemic). Comparatively, for pediatricians, patient volume remains down 18%. Dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and orthopedists report that visits are down by about 15%.

The number of hours worked also rebounded for internists. In fact, some report working slightly more hours now than they did before the pandemic (52 hours a week, up from 50).

Pay for internists continues to hover near the bottom of the scale among specialties. In this year’s Medscape Internist Compensation Report 2021, internists averaged $248,000, down from $251,000 last year. Pediatricians were the lowest paid, at $221,000, followed by family physicians, at $236,000. Plastic surgeons made the most, at $526,000, followed by orthopedists, at $511,000.

It helped to be self-employed. These internists made $276,000 on average, compared with $238,000 for their employed counterparts.

Half say pay is fair

Internists are also near the bottom among specialists who feel they are fairly compensated. As in last year’s survey, just more than half of internists (52%) said they felt that they were fairly paid this year. By comparison, 79% of oncologists reported they were fairly compensated, which is on the high end regarding satisfaction, but only 44% of infectious diseases specialists felt that way.

Some indicators in the survey responses may help explain the dissatisfaction.

Internists are near the top in time spent on paperwork. On average, they spent 19.7 hours on paperwork and administration this year, up slightly from 18.5 last year. Infectious disease physicians spent the most time on those tasks (24.2 hours a week), and anesthesiologists spent the fewest, at 10.1 hours per week.

Administrative work was among many frustrations internists reported. The following are the top five most challenging aspects of the job, according to the respondents:

- Having so many rules and regulations (24%)

- Having to work long hours (16%)

- Dealing with difficult patients (16%)

- Working with electronic health records systems (11%)

- Danger/risk associated with treating COVID-19 patients (10%)

Conversely, the most rewarding aspects were “gratitude/relationships with patients” (31%); “knowing that I’m making the world a better place” (26%); and “being very good at what I do” (20%).

More than one-third lost income

More than one-third of internists (36%) reported that they lost some income during the past year.

Among those who lost income, 81% said they expect income to return to prepandemic levels within 3 years. Half of that group expected the rebound would come within the next year.

Slightly more than one-third of internists said they would participate in the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS), and 12% said they would participate in advanced alternative payment models. The rest either said they would participate in neither, or they hadn’t decided.

“The stakes for the Quality Payment Program – the program that incorporates MIPS – are high, with a 9% penalty applied to all Medicare reimbursement for failure to participate,” says Elizabeth Woodcock, MBA, CPC, president of the physician practice consulting firm Woodcock and Associates, in Atlanta, Georgia.

“With margins already slim,” she told this news organization, “most physicians can’t afford this massive penalty.”

If they could choose again, most internists (76%) said they would choose medicine, which was almost the same number as physicians overall who would pick medicine again. Oncologists (88%) and ophthalmologists (87%) were the specialists most likely to choose medicine again. Those in physical medicine and rehabilitation were least likely to choose medicine again, at 67%.

But asked about their specialty, internists’ enthusiasm decreased. Only 68% said that they would make that same choice again.

That was up considerably, however, from the 2015 survey: For that year, only 25% said they would choose internal medicine again.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Less ambulatory care occurred than expected in pandemic, according to study

according to an analysis of national claims data from Jan. 1, 2019, to Oct. 31, 2020.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has seriously disrupted access to U.S. ambulatory care, endangering population health,” said John N. Mafi, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Dr. Mafi and colleagues conducted the analysis, which included 20 monthly cohorts, and measured outpatient visit rates per 100 members across all 20 study months. The researchers used a “difference-in-differences study design” and compared changes in rates of ambulatory care visits in January-February 2019 through September-October 2019 with the same periods in 2020.

They found that overall utilization fell to 68.9% of expected rates. This number increased to 82.6% of expected rates by May-June 2020 and to 87.7% of expected rates by July-August 2020.

To examine the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. ambulatory care patterns, the researchers identified 10.4 million individuals aged 18 years and older using the MedInsight research claims database. This database included Medicaid, commercial, dual eligible (receiving both Medicare and Medicaid benefits), Medicare Advantage (MA), and Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) patients. The average age of the individuals studied was 52 years, and 55% of the population were women. The researchers measured outpatient visit rates per 100 beneficiaries for several types of ambulatory care visits: emergency, urgent care, office, physical exams, preventive, alcohol/drug, and psychiatric care.

The researchers verified parallel trends in visits between 2018 and 2019 to establish a historical benchmark and divided the patient population into three groups based on insurance enrollment (continuously enrolled, not continuously enrolled, and fully enrolled) to account for new members adding insurance and disrupted coverage caused by job losses or other factors. The trends in ambulatory care utilization were similar between cohorts across the groups.

The rebound seen by the summer of 2020 showed variation when broken out by insurance type: 94.0% for Medicare FFS; 88.9% for commercial insurance; 86.3% for Medicare Advantage; 83.6% for dual eligible; and 78.0% for Medicaid.

“The big picture is that utilization looks similar across the three groups and has not attained prepandemic levels,” Dr. Mafi said.

When the results were divided by service type, utilization rates remained below expected rates while needs remain similar for U.S. Preventive Services Task Force–recommended preventive screening services, Dr. Mafi noted. The demand for psychiatric and substance use services has increased, but use rates are below expected rates. In addition, both avoidable and nonavoidable ED utilization both remained below expected rates.

In-person visits are down across insurance groups, but virtual visits are skyrocketing, across all insurance groups, Dr. Mafi added. However, virtual care visits have not completely compensated for declines in in-person visits, notably among dual-eligible and Medicaid insurance members.

Takeaways for policy makers include the fact that, while some reductions in unnecessary care, such as avoidable ED visits, may be beneficial, the “reduced USPSTF-recommended cancer and other evidence-based disease prevention may worsen health outcomes, particularly for Medicaid beneficiaries,” he said.

Outreach and outcomes

The study is important because “understanding ambulatory care patterns during the pandemic can highlight vulnerabilities and opportunities in our health care system,” Dr. Mafi said in an interview.

“While the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously disrupted access to U.S. ambulatory care, most studies have focused on the early months of the pandemic,” he noted.

Dr. Mafi said he was not surprised that ambulatory care utilization has not rebounded among Medicaid beneficiaries relative to other insurance groups.

“Medicaid beneficiaries are underresourced individuals who are disproportionately racial/ethnic minorities, and they historically have had difficulties accessing care. Our data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic may be widening these preexisting inequities in access to ambulatory care,” he observed.

The study findings were limited by the use of the MedInsight research dataset, which is a convenience sample; and, therefore, the results might not be generalizable nationally, Dr. Mafi said. “However, it does include beneficiaries from all major insurance types across all 50 U.S. states. Additionally, our analysis was completed at the population level rather than the patient level, and so we were unable to account for patient-level characteristics such as clinical complexity,” he explained.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that our patients with Medicaid insurance may need additional efforts to overcome barriers to accessing ambulatory care, such as creating robust telemedicine outreach programs,” said Dr. Mafi. “Policy makers should also consider providing additional support and resources to safety net health systems who disproportionately care for Medicaid beneficiaries, such as higher reimbursements for both in-person and telemedicine visits.”

More research is needed, he emphasized. “We urgently need further inquiry into the impact of this persistently deferred ambulatory care utilization on important health outcomes such as preventable death/disability and quality of care.”

COVID consequences challenge ambulatory care

“These study findings mirror what we are seeing in primary care settings,” Maureen Lyons, MD, of Washington University. St. Louis, said in an interview. “With the pandemic, there are many additional barriers for patients accessing care, and these barriers have disproportionately impacted those who are already disadvantaged.

“From clinical experience, there are barriers directly related to COVID-19, such as the risk of infection or discomfort being in a clinic setting with other people. However, there also are barriers related to change in financial situation or insurance related to changes or loss of employment,” she said.

“Additionally, many patients have needed to take on increased responsibilities in other areas of their lives, such as caring for an ill family member or being responsible for children’s virtual school,” she said. These new responsibilities can lead people to skip or postpone ambulatory care visits.

“Loss of ambulatory care is likely to lead to increases in preventable illnesses with long-lasting effects,” Dr. Lyons noted. “Studying this in a robust fashion, as Dr. Mafi and colleagues have done, is a critical step in understanding and addressing this urgent need.”

Dr. Mafi noted that the data he presented is preliminary, and that he and his team hope to publish finalized estimates of ambulatory utilization rates in a forthcoming scientific paper.

The study was a collaboration between UCLA and Millman MedInsight, an actuarial health analytics company. Several coauthors are Millman employees. Dr. Mafi and the other researchers had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lyons had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to an analysis of national claims data from Jan. 1, 2019, to Oct. 31, 2020.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has seriously disrupted access to U.S. ambulatory care, endangering population health,” said John N. Mafi, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Dr. Mafi and colleagues conducted the analysis, which included 20 monthly cohorts, and measured outpatient visit rates per 100 members across all 20 study months. The researchers used a “difference-in-differences study design” and compared changes in rates of ambulatory care visits in January-February 2019 through September-October 2019 with the same periods in 2020.

They found that overall utilization fell to 68.9% of expected rates. This number increased to 82.6% of expected rates by May-June 2020 and to 87.7% of expected rates by July-August 2020.

To examine the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. ambulatory care patterns, the researchers identified 10.4 million individuals aged 18 years and older using the MedInsight research claims database. This database included Medicaid, commercial, dual eligible (receiving both Medicare and Medicaid benefits), Medicare Advantage (MA), and Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) patients. The average age of the individuals studied was 52 years, and 55% of the population were women. The researchers measured outpatient visit rates per 100 beneficiaries for several types of ambulatory care visits: emergency, urgent care, office, physical exams, preventive, alcohol/drug, and psychiatric care.

The researchers verified parallel trends in visits between 2018 and 2019 to establish a historical benchmark and divided the patient population into three groups based on insurance enrollment (continuously enrolled, not continuously enrolled, and fully enrolled) to account for new members adding insurance and disrupted coverage caused by job losses or other factors. The trends in ambulatory care utilization were similar between cohorts across the groups.

The rebound seen by the summer of 2020 showed variation when broken out by insurance type: 94.0% for Medicare FFS; 88.9% for commercial insurance; 86.3% for Medicare Advantage; 83.6% for dual eligible; and 78.0% for Medicaid.

“The big picture is that utilization looks similar across the three groups and has not attained prepandemic levels,” Dr. Mafi said.

When the results were divided by service type, utilization rates remained below expected rates while needs remain similar for U.S. Preventive Services Task Force–recommended preventive screening services, Dr. Mafi noted. The demand for psychiatric and substance use services has increased, but use rates are below expected rates. In addition, both avoidable and nonavoidable ED utilization both remained below expected rates.

In-person visits are down across insurance groups, but virtual visits are skyrocketing, across all insurance groups, Dr. Mafi added. However, virtual care visits have not completely compensated for declines in in-person visits, notably among dual-eligible and Medicaid insurance members.

Takeaways for policy makers include the fact that, while some reductions in unnecessary care, such as avoidable ED visits, may be beneficial, the “reduced USPSTF-recommended cancer and other evidence-based disease prevention may worsen health outcomes, particularly for Medicaid beneficiaries,” he said.

Outreach and outcomes

The study is important because “understanding ambulatory care patterns during the pandemic can highlight vulnerabilities and opportunities in our health care system,” Dr. Mafi said in an interview.

“While the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously disrupted access to U.S. ambulatory care, most studies have focused on the early months of the pandemic,” he noted.

Dr. Mafi said he was not surprised that ambulatory care utilization has not rebounded among Medicaid beneficiaries relative to other insurance groups.

“Medicaid beneficiaries are underresourced individuals who are disproportionately racial/ethnic minorities, and they historically have had difficulties accessing care. Our data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic may be widening these preexisting inequities in access to ambulatory care,” he observed.

The study findings were limited by the use of the MedInsight research dataset, which is a convenience sample; and, therefore, the results might not be generalizable nationally, Dr. Mafi said. “However, it does include beneficiaries from all major insurance types across all 50 U.S. states. Additionally, our analysis was completed at the population level rather than the patient level, and so we were unable to account for patient-level characteristics such as clinical complexity,” he explained.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that our patients with Medicaid insurance may need additional efforts to overcome barriers to accessing ambulatory care, such as creating robust telemedicine outreach programs,” said Dr. Mafi. “Policy makers should also consider providing additional support and resources to safety net health systems who disproportionately care for Medicaid beneficiaries, such as higher reimbursements for both in-person and telemedicine visits.”

More research is needed, he emphasized. “We urgently need further inquiry into the impact of this persistently deferred ambulatory care utilization on important health outcomes such as preventable death/disability and quality of care.”

COVID consequences challenge ambulatory care

“These study findings mirror what we are seeing in primary care settings,” Maureen Lyons, MD, of Washington University. St. Louis, said in an interview. “With the pandemic, there are many additional barriers for patients accessing care, and these barriers have disproportionately impacted those who are already disadvantaged.

“From clinical experience, there are barriers directly related to COVID-19, such as the risk of infection or discomfort being in a clinic setting with other people. However, there also are barriers related to change in financial situation or insurance related to changes or loss of employment,” she said.

“Additionally, many patients have needed to take on increased responsibilities in other areas of their lives, such as caring for an ill family member or being responsible for children’s virtual school,” she said. These new responsibilities can lead people to skip or postpone ambulatory care visits.

“Loss of ambulatory care is likely to lead to increases in preventable illnesses with long-lasting effects,” Dr. Lyons noted. “Studying this in a robust fashion, as Dr. Mafi and colleagues have done, is a critical step in understanding and addressing this urgent need.”

Dr. Mafi noted that the data he presented is preliminary, and that he and his team hope to publish finalized estimates of ambulatory utilization rates in a forthcoming scientific paper.

The study was a collaboration between UCLA and Millman MedInsight, an actuarial health analytics company. Several coauthors are Millman employees. Dr. Mafi and the other researchers had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lyons had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to an analysis of national claims data from Jan. 1, 2019, to Oct. 31, 2020.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has seriously disrupted access to U.S. ambulatory care, endangering population health,” said John N. Mafi, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

Dr. Mafi and colleagues conducted the analysis, which included 20 monthly cohorts, and measured outpatient visit rates per 100 members across all 20 study months. The researchers used a “difference-in-differences study design” and compared changes in rates of ambulatory care visits in January-February 2019 through September-October 2019 with the same periods in 2020.

They found that overall utilization fell to 68.9% of expected rates. This number increased to 82.6% of expected rates by May-June 2020 and to 87.7% of expected rates by July-August 2020.

To examine the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. ambulatory care patterns, the researchers identified 10.4 million individuals aged 18 years and older using the MedInsight research claims database. This database included Medicaid, commercial, dual eligible (receiving both Medicare and Medicaid benefits), Medicare Advantage (MA), and Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) patients. The average age of the individuals studied was 52 years, and 55% of the population were women. The researchers measured outpatient visit rates per 100 beneficiaries for several types of ambulatory care visits: emergency, urgent care, office, physical exams, preventive, alcohol/drug, and psychiatric care.

The researchers verified parallel trends in visits between 2018 and 2019 to establish a historical benchmark and divided the patient population into three groups based on insurance enrollment (continuously enrolled, not continuously enrolled, and fully enrolled) to account for new members adding insurance and disrupted coverage caused by job losses or other factors. The trends in ambulatory care utilization were similar between cohorts across the groups.

The rebound seen by the summer of 2020 showed variation when broken out by insurance type: 94.0% for Medicare FFS; 88.9% for commercial insurance; 86.3% for Medicare Advantage; 83.6% for dual eligible; and 78.0% for Medicaid.

“The big picture is that utilization looks similar across the three groups and has not attained prepandemic levels,” Dr. Mafi said.

When the results were divided by service type, utilization rates remained below expected rates while needs remain similar for U.S. Preventive Services Task Force–recommended preventive screening services, Dr. Mafi noted. The demand for psychiatric and substance use services has increased, but use rates are below expected rates. In addition, both avoidable and nonavoidable ED utilization both remained below expected rates.

In-person visits are down across insurance groups, but virtual visits are skyrocketing, across all insurance groups, Dr. Mafi added. However, virtual care visits have not completely compensated for declines in in-person visits, notably among dual-eligible and Medicaid insurance members.

Takeaways for policy makers include the fact that, while some reductions in unnecessary care, such as avoidable ED visits, may be beneficial, the “reduced USPSTF-recommended cancer and other evidence-based disease prevention may worsen health outcomes, particularly for Medicaid beneficiaries,” he said.

Outreach and outcomes

The study is important because “understanding ambulatory care patterns during the pandemic can highlight vulnerabilities and opportunities in our health care system,” Dr. Mafi said in an interview.

“While the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously disrupted access to U.S. ambulatory care, most studies have focused on the early months of the pandemic,” he noted.

Dr. Mafi said he was not surprised that ambulatory care utilization has not rebounded among Medicaid beneficiaries relative to other insurance groups.

“Medicaid beneficiaries are underresourced individuals who are disproportionately racial/ethnic minorities, and they historically have had difficulties accessing care. Our data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic may be widening these preexisting inequities in access to ambulatory care,” he observed.

The study findings were limited by the use of the MedInsight research dataset, which is a convenience sample; and, therefore, the results might not be generalizable nationally, Dr. Mafi said. “However, it does include beneficiaries from all major insurance types across all 50 U.S. states. Additionally, our analysis was completed at the population level rather than the patient level, and so we were unable to account for patient-level characteristics such as clinical complexity,” he explained.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that our patients with Medicaid insurance may need additional efforts to overcome barriers to accessing ambulatory care, such as creating robust telemedicine outreach programs,” said Dr. Mafi. “Policy makers should also consider providing additional support and resources to safety net health systems who disproportionately care for Medicaid beneficiaries, such as higher reimbursements for both in-person and telemedicine visits.”

More research is needed, he emphasized. “We urgently need further inquiry into the impact of this persistently deferred ambulatory care utilization on important health outcomes such as preventable death/disability and quality of care.”

COVID consequences challenge ambulatory care

“These study findings mirror what we are seeing in primary care settings,” Maureen Lyons, MD, of Washington University. St. Louis, said in an interview. “With the pandemic, there are many additional barriers for patients accessing care, and these barriers have disproportionately impacted those who are already disadvantaged.

“From clinical experience, there are barriers directly related to COVID-19, such as the risk of infection or discomfort being in a clinic setting with other people. However, there also are barriers related to change in financial situation or insurance related to changes or loss of employment,” she said.

“Additionally, many patients have needed to take on increased responsibilities in other areas of their lives, such as caring for an ill family member or being responsible for children’s virtual school,” she said. These new responsibilities can lead people to skip or postpone ambulatory care visits.

“Loss of ambulatory care is likely to lead to increases in preventable illnesses with long-lasting effects,” Dr. Lyons noted. “Studying this in a robust fashion, as Dr. Mafi and colleagues have done, is a critical step in understanding and addressing this urgent need.”

Dr. Mafi noted that the data he presented is preliminary, and that he and his team hope to publish finalized estimates of ambulatory utilization rates in a forthcoming scientific paper.

The study was a collaboration between UCLA and Millman MedInsight, an actuarial health analytics company. Several coauthors are Millman employees. Dr. Mafi and the other researchers had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lyons had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SGIM 2021

Telemedicine is popular among Mohs surgeons – for now

A majority of

A variety of factors combine to make it “very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices,” said Mario Maruthur, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “Telemedicine likely has a role in Mohs practices, particularly with postop follow-up visits. However, postpandemic reimbursement and regulatory issues need to be formally laid out before Mohs surgeons are able to incorporate it into their permanent work flow.”

Dr. Maruthur, a Mohs surgery and dermatologic oncology fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members in September and October 2020. “We saw first-hand in our surgical practice that telemedicine quickly became an important tool when the pandemic surged in the spring of 2020,” he said. Considering that surgical practices are highly dependent on in-person visits, the impetus for this study was to assess to what degree Mohs practices from across the spectrum, including academic and private practices, embraced telemedicine during the pandemic, and “what these surgical practices used telemedicine for, how it was received by their patients, which telemedicine platforms were most often utilized, and lastly, what are their plans if any for incorporating telemedicine into their surgical practices after the pandemic subsides.”

The researchers received responses from 115 surgeons representing all regions of the country (40% Northeast, 21% South, 21% Midwest, and 18% West). Half practiced in urban areas (37%) and large cities (13%), and 40% were in an academic setting versus 36% in a single-specialty private practice.

More than 70% of the respondents said their case load fell by at least 75% during the initial surge of the pandemic; 80% turned to telemedicine, compared with just 23% who relied on the technology prior to the pandemic. The most commonly used telemedicine technologies were FaceTime, Zoom, Doximity, and Epic.

Mohs surgeons reported most commonly using telemedicine for postsurgery management (77% of the total 115 responses). “Telemedicine is a great fit for this category of visits as they allow the surgeon to view the surgical site and answer any questions they patient may have,” Dr. Maruthur said. “If the surgeon does suspect a postop infection or other concern based on a patient’s signs or symptoms, they can easily schedule the patient for an in-person assessment. We suspect that postop follow-up visits may be the best candidate for long-term use of telemedicine in Mohs surgery practices.”

Surgeons also reported using telemedicine for “spot checks” (61%) and surgical consultations (59%).

However, Dr. Maruther noted that preoperative assessments and spot checks can be difficult to perform using telemedicine. “The quality of the video image is not always great, patients can have a difficult time pointing the camera at the right spot and at the right distance. Even appreciating the actual size of the lesion are all difficult over a video encounter. And there is a lot of information gleaned from in-person physical examination, such as whether the lesion is fixed to a deeper structure and whether there are any nearby scars or other suspicious lesions.”

Nearly three-quarters of the surgeons using the technology said most or all patients were receptive to telemedicine.

However, the surgeons reported multiple barriers to the use of telemedicine: Limitations when compared with physical exams (88%), fitting it into the work flow (58%), patient response and training (57%), reimbursement concerns (50%), implementation of the technology (37%), regulations such as HIPAA (24%), training of staff (17%), and licensing (8%).

In an interview, Sumaira Z. Aasi, MD, director of Mohs and dermatologic surgery, Stanford University, agreed that there are many obstacles to routine use of telemedicine by Mohs surgeons. “As surgeons, we rely on the physical and tactile exam to get a sense of the size and extent of the cancer and characteristics such as the laxity of the surrounding tissue whether the tumor is fixed,” she said. “It is very difficult to access this on a telemedicine visit.”

In addition, she said, “many of our patients are in the elderly population, and some may not be comfortable using this technology. Also, it’s not a work flow that we are comfortable or familiar with. And I think that the technology has to improve to allow for better resolution of images as we ‘examine’ patients through a telemedicine visit.”

She added that “another con is there is a reliance on having the patient point out lesions of concern. Many cancers are picked by a careful in-person examination by a qualified physician/dermatologist/Mohs surgeon when the lesion is quite small or subtle and not even noticed by the patient themselves. This approach invariably leads to earlier biopsies and earlier treatments that can prevent morbidity and save health care money.”

On the other hand, she said, telemedicine “may save patients some time and money in terms of the effort and cost of transportation to come in for simpler postoperative medical visits that are often short in their very nature, such as postop check-ups.”

Most of the surgeons surveyed (69%) said telemedicine probably or definitely deserves a place in the practice Mohs surgery, but only 50% said they’d like to or would definitely pursue giving telemedicine a role in their practices once the pandemic is over.

“At the start of the pandemic, many regulations in areas such as HIPAA were eased, and reimbursements were increased, which allowed telemedicine to be quickly adopted,” Dr. Maruther said. “The government and payers have yet to decide which regulations and reimbursements will be in place after the pandemic. That makes it very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices.”

Dr. Aasi predicted that telemedicine will become more appealing to patients and physicians as it its technology and usability improves. More familiarity with its use will also be helpful, she said, and surgeons will be more receptive as it’s incorporated into efficient daily work flow.

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

A majority of

A variety of factors combine to make it “very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices,” said Mario Maruthur, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “Telemedicine likely has a role in Mohs practices, particularly with postop follow-up visits. However, postpandemic reimbursement and regulatory issues need to be formally laid out before Mohs surgeons are able to incorporate it into their permanent work flow.”

Dr. Maruthur, a Mohs surgery and dermatologic oncology fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members in September and October 2020. “We saw first-hand in our surgical practice that telemedicine quickly became an important tool when the pandemic surged in the spring of 2020,” he said. Considering that surgical practices are highly dependent on in-person visits, the impetus for this study was to assess to what degree Mohs practices from across the spectrum, including academic and private practices, embraced telemedicine during the pandemic, and “what these surgical practices used telemedicine for, how it was received by their patients, which telemedicine platforms were most often utilized, and lastly, what are their plans if any for incorporating telemedicine into their surgical practices after the pandemic subsides.”

The researchers received responses from 115 surgeons representing all regions of the country (40% Northeast, 21% South, 21% Midwest, and 18% West). Half practiced in urban areas (37%) and large cities (13%), and 40% were in an academic setting versus 36% in a single-specialty private practice.

More than 70% of the respondents said their case load fell by at least 75% during the initial surge of the pandemic; 80% turned to telemedicine, compared with just 23% who relied on the technology prior to the pandemic. The most commonly used telemedicine technologies were FaceTime, Zoom, Doximity, and Epic.

Mohs surgeons reported most commonly using telemedicine for postsurgery management (77% of the total 115 responses). “Telemedicine is a great fit for this category of visits as they allow the surgeon to view the surgical site and answer any questions they patient may have,” Dr. Maruthur said. “If the surgeon does suspect a postop infection or other concern based on a patient’s signs or symptoms, they can easily schedule the patient for an in-person assessment. We suspect that postop follow-up visits may be the best candidate for long-term use of telemedicine in Mohs surgery practices.”

Surgeons also reported using telemedicine for “spot checks” (61%) and surgical consultations (59%).

However, Dr. Maruther noted that preoperative assessments and spot checks can be difficult to perform using telemedicine. “The quality of the video image is not always great, patients can have a difficult time pointing the camera at the right spot and at the right distance. Even appreciating the actual size of the lesion are all difficult over a video encounter. And there is a lot of information gleaned from in-person physical examination, such as whether the lesion is fixed to a deeper structure and whether there are any nearby scars or other suspicious lesions.”

Nearly three-quarters of the surgeons using the technology said most or all patients were receptive to telemedicine.

However, the surgeons reported multiple barriers to the use of telemedicine: Limitations when compared with physical exams (88%), fitting it into the work flow (58%), patient response and training (57%), reimbursement concerns (50%), implementation of the technology (37%), regulations such as HIPAA (24%), training of staff (17%), and licensing (8%).

In an interview, Sumaira Z. Aasi, MD, director of Mohs and dermatologic surgery, Stanford University, agreed that there are many obstacles to routine use of telemedicine by Mohs surgeons. “As surgeons, we rely on the physical and tactile exam to get a sense of the size and extent of the cancer and characteristics such as the laxity of the surrounding tissue whether the tumor is fixed,” she said. “It is very difficult to access this on a telemedicine visit.”

In addition, she said, “many of our patients are in the elderly population, and some may not be comfortable using this technology. Also, it’s not a work flow that we are comfortable or familiar with. And I think that the technology has to improve to allow for better resolution of images as we ‘examine’ patients through a telemedicine visit.”

She added that “another con is there is a reliance on having the patient point out lesions of concern. Many cancers are picked by a careful in-person examination by a qualified physician/dermatologist/Mohs surgeon when the lesion is quite small or subtle and not even noticed by the patient themselves. This approach invariably leads to earlier biopsies and earlier treatments that can prevent morbidity and save health care money.”

On the other hand, she said, telemedicine “may save patients some time and money in terms of the effort and cost of transportation to come in for simpler postoperative medical visits that are often short in their very nature, such as postop check-ups.”

Most of the surgeons surveyed (69%) said telemedicine probably or definitely deserves a place in the practice Mohs surgery, but only 50% said they’d like to or would definitely pursue giving telemedicine a role in their practices once the pandemic is over.

“At the start of the pandemic, many regulations in areas such as HIPAA were eased, and reimbursements were increased, which allowed telemedicine to be quickly adopted,” Dr. Maruther said. “The government and payers have yet to decide which regulations and reimbursements will be in place after the pandemic. That makes it very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices.”

Dr. Aasi predicted that telemedicine will become more appealing to patients and physicians as it its technology and usability improves. More familiarity with its use will also be helpful, she said, and surgeons will be more receptive as it’s incorporated into efficient daily work flow.

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

A majority of

A variety of factors combine to make it “very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices,” said Mario Maruthur, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “Telemedicine likely has a role in Mohs practices, particularly with postop follow-up visits. However, postpandemic reimbursement and regulatory issues need to be formally laid out before Mohs surgeons are able to incorporate it into their permanent work flow.”

Dr. Maruthur, a Mohs surgery and dermatologic oncology fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members in September and October 2020. “We saw first-hand in our surgical practice that telemedicine quickly became an important tool when the pandemic surged in the spring of 2020,” he said. Considering that surgical practices are highly dependent on in-person visits, the impetus for this study was to assess to what degree Mohs practices from across the spectrum, including academic and private practices, embraced telemedicine during the pandemic, and “what these surgical practices used telemedicine for, how it was received by their patients, which telemedicine platforms were most often utilized, and lastly, what are their plans if any for incorporating telemedicine into their surgical practices after the pandemic subsides.”

The researchers received responses from 115 surgeons representing all regions of the country (40% Northeast, 21% South, 21% Midwest, and 18% West). Half practiced in urban areas (37%) and large cities (13%), and 40% were in an academic setting versus 36% in a single-specialty private practice.

More than 70% of the respondents said their case load fell by at least 75% during the initial surge of the pandemic; 80% turned to telemedicine, compared with just 23% who relied on the technology prior to the pandemic. The most commonly used telemedicine technologies were FaceTime, Zoom, Doximity, and Epic.

Mohs surgeons reported most commonly using telemedicine for postsurgery management (77% of the total 115 responses). “Telemedicine is a great fit for this category of visits as they allow the surgeon to view the surgical site and answer any questions they patient may have,” Dr. Maruthur said. “If the surgeon does suspect a postop infection or other concern based on a patient’s signs or symptoms, they can easily schedule the patient for an in-person assessment. We suspect that postop follow-up visits may be the best candidate for long-term use of telemedicine in Mohs surgery practices.”

Surgeons also reported using telemedicine for “spot checks” (61%) and surgical consultations (59%).

However, Dr. Maruther noted that preoperative assessments and spot checks can be difficult to perform using telemedicine. “The quality of the video image is not always great, patients can have a difficult time pointing the camera at the right spot and at the right distance. Even appreciating the actual size of the lesion are all difficult over a video encounter. And there is a lot of information gleaned from in-person physical examination, such as whether the lesion is fixed to a deeper structure and whether there are any nearby scars or other suspicious lesions.”

Nearly three-quarters of the surgeons using the technology said most or all patients were receptive to telemedicine.

However, the surgeons reported multiple barriers to the use of telemedicine: Limitations when compared with physical exams (88%), fitting it into the work flow (58%), patient response and training (57%), reimbursement concerns (50%), implementation of the technology (37%), regulations such as HIPAA (24%), training of staff (17%), and licensing (8%).

In an interview, Sumaira Z. Aasi, MD, director of Mohs and dermatologic surgery, Stanford University, agreed that there are many obstacles to routine use of telemedicine by Mohs surgeons. “As surgeons, we rely on the physical and tactile exam to get a sense of the size and extent of the cancer and characteristics such as the laxity of the surrounding tissue whether the tumor is fixed,” she said. “It is very difficult to access this on a telemedicine visit.”

In addition, she said, “many of our patients are in the elderly population, and some may not be comfortable using this technology. Also, it’s not a work flow that we are comfortable or familiar with. And I think that the technology has to improve to allow for better resolution of images as we ‘examine’ patients through a telemedicine visit.”

She added that “another con is there is a reliance on having the patient point out lesions of concern. Many cancers are picked by a careful in-person examination by a qualified physician/dermatologist/Mohs surgeon when the lesion is quite small or subtle and not even noticed by the patient themselves. This approach invariably leads to earlier biopsies and earlier treatments that can prevent morbidity and save health care money.”

On the other hand, she said, telemedicine “may save patients some time and money in terms of the effort and cost of transportation to come in for simpler postoperative medical visits that are often short in their very nature, such as postop check-ups.”

Most of the surgeons surveyed (69%) said telemedicine probably or definitely deserves a place in the practice Mohs surgery, but only 50% said they’d like to or would definitely pursue giving telemedicine a role in their practices once the pandemic is over.

“At the start of the pandemic, many regulations in areas such as HIPAA were eased, and reimbursements were increased, which allowed telemedicine to be quickly adopted,” Dr. Maruther said. “The government and payers have yet to decide which regulations and reimbursements will be in place after the pandemic. That makes it very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices.”

Dr. Aasi predicted that telemedicine will become more appealing to patients and physicians as it its technology and usability improves. More familiarity with its use will also be helpful, she said, and surgeons will be more receptive as it’s incorporated into efficient daily work flow.

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Pediatricians see drop in income during the pandemic

The average income for pediatricians declined slightly from 2019 to 2020, according to the Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2021.

The report, which was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021, found that the average pediatrician income was down $11,000 – from $232,000 in 2019 to $221,000 in 2020, with 48% of pediatricians reporting at least some decline in compensation.

The specialty also earned the least amount of money in 2020, compared with all of the other specialties, which isn’t surprising since pediatricians have been among the lowest-paid physician specialties since 2013. The highest-earning specialty was plastic surgery with an average income of $526,000 annually.

Most pediatricians who saw a drop in income cited pandemic-related issues such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients.

Jesse Hackell, MD, vice president and chief operating officer of Ponoma Pediatrics in New York, said in an interview the reduced wages pediatricians saw in 2020 didn’t surprise him because many pediatric offices saw a huge drop in visits that were not urgent.

“[The report] shows that procedural specialties tended to do a lot better than the nonprocedural specialties,” Dr. Hackell said. “That’s because, during the shutdown, if you broke your leg, you still needed the orthopedist. And even though the hospitals weren’t doing elective surgeries, they were certainly doing the emergency stuff.”

Meanwhile, in pediatrician offices, where Dr. Hackell said office visits dropped 70%-80% at the beginning of the pandemic, “parents weren’t going to bring a healthy kid out for routine visits and they weren’t going to bring a kid out for minor illnesses and expose them to possibly communicable diseases in the office.”

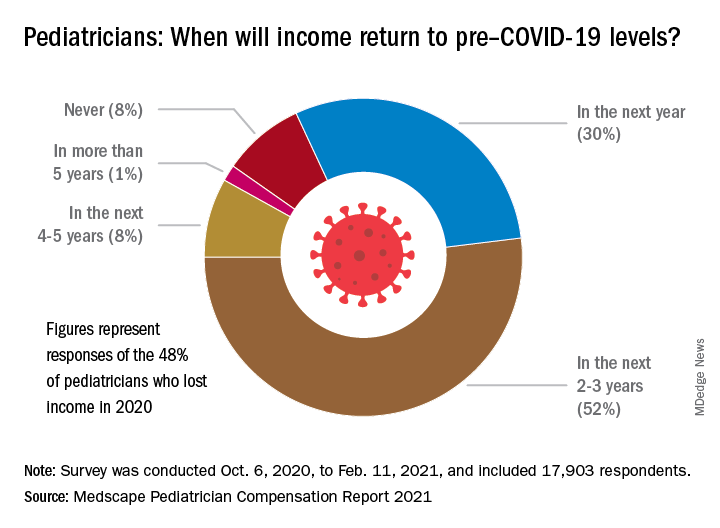

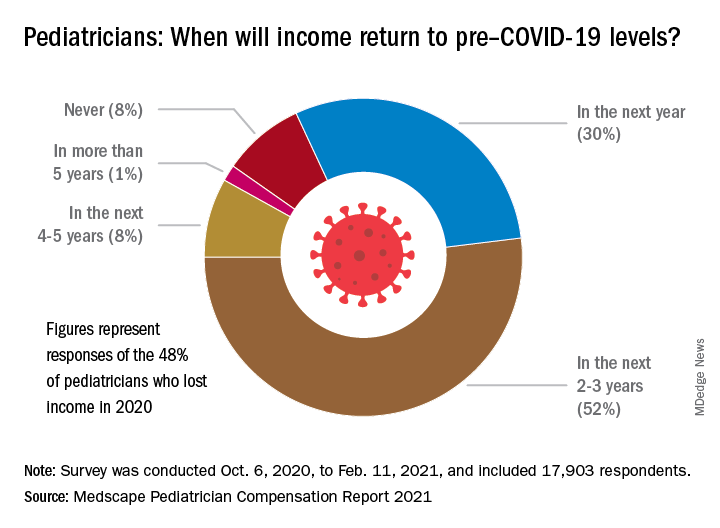

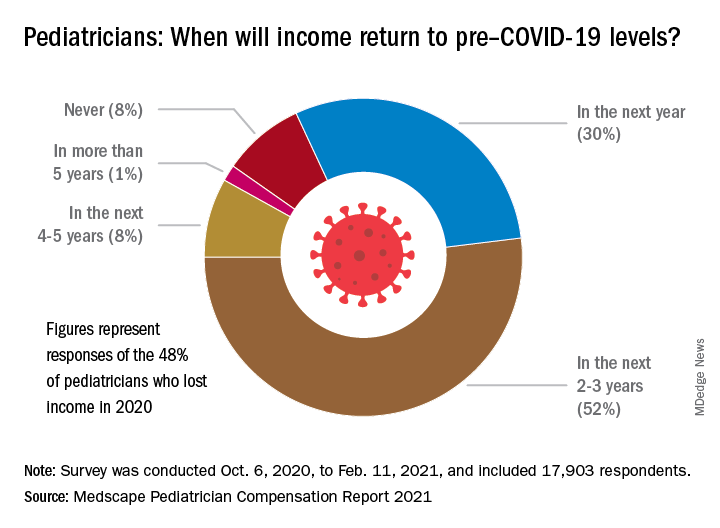

About 52% of pediatricians who lost income because of the pandemic believe their income levels will return to normal in 2-3 years. Meanwhile 30% of pediatricians expect their income to return to normal within a year, and 8% believe it will take 4 years for them to bounce back.

Physician work hours generally declined for some time during the pandemic, according to the report. However, most pediatricians are working about the same number of hours as they did before the pandemic, which is 47 hours per week.

Despite working the same number of hours per week that they did prepandemic, they are seeing fewer patients. They are currently seeing on average 64 patients per week, compared with the 78 patients they used to see weekly before the pandemic.

Dr. Hackell said that might be because pediatric offices are trying to make up the loss of revenue during the beginning of the pandemic, from the reduced number of well visits and immunizations, in the second half of the year with outreach.

“Since about June 2020, we’ve been making concerted efforts to remind parents that preventing other infectious diseases is critically important,” Dr. Hackell explained. “And so actually, for the second half of the year, many of us saw more well visits and immunization volume than in 2019 as we sought to make up the gap. It wasn’t that we were seeing more overall, but we’re trying to make up the gap that happened from March, April, May, [and] June.”

Most pediatricians find their work rewarding. One-third say the most rewarding part of their job is gratitude from and relationships with their patients. Meanwhile, 31% of pediatricians said knowing they are making the world a better place was a rewarding part of their job. Only 8% of them said making money was a rewarding part of their job.

Dr. Hackell said he did not go into pediatrics to make money, it was because he found it stimulating and has “no complaints.”

“I’ve been a pediatrician for 40 years and I wouldn’t do anything else,” Dr. Hackell said. “I don’t know that there’s anything that I would find as rewarding as the relationships that I’ve had over 40 years with my patients. You know, getting invited to weddings of kids who I saw when they were newborns is pretty impressive. It’s the gratification of having ongoing relationships with families.”

Furthermore, the report revealed that 77% of pediatricians said they would pick medicine again if they had a choice, and 82% said they would choose the same specialty.

The experts disclosed no relevant financial interests.

*This story was updated on 5/18/2021.

The average income for pediatricians declined slightly from 2019 to 2020, according to the Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2021.

The report, which was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021, found that the average pediatrician income was down $11,000 – from $232,000 in 2019 to $221,000 in 2020, with 48% of pediatricians reporting at least some decline in compensation.

The specialty also earned the least amount of money in 2020, compared with all of the other specialties, which isn’t surprising since pediatricians have been among the lowest-paid physician specialties since 2013. The highest-earning specialty was plastic surgery with an average income of $526,000 annually.

Most pediatricians who saw a drop in income cited pandemic-related issues such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients.

Jesse Hackell, MD, vice president and chief operating officer of Ponoma Pediatrics in New York, said in an interview the reduced wages pediatricians saw in 2020 didn’t surprise him because many pediatric offices saw a huge drop in visits that were not urgent.

“[The report] shows that procedural specialties tended to do a lot better than the nonprocedural specialties,” Dr. Hackell said. “That’s because, during the shutdown, if you broke your leg, you still needed the orthopedist. And even though the hospitals weren’t doing elective surgeries, they were certainly doing the emergency stuff.”

Meanwhile, in pediatrician offices, where Dr. Hackell said office visits dropped 70%-80% at the beginning of the pandemic, “parents weren’t going to bring a healthy kid out for routine visits and they weren’t going to bring a kid out for minor illnesses and expose them to possibly communicable diseases in the office.”

About 52% of pediatricians who lost income because of the pandemic believe their income levels will return to normal in 2-3 years. Meanwhile 30% of pediatricians expect their income to return to normal within a year, and 8% believe it will take 4 years for them to bounce back.

Physician work hours generally declined for some time during the pandemic, according to the report. However, most pediatricians are working about the same number of hours as they did before the pandemic, which is 47 hours per week.

Despite working the same number of hours per week that they did prepandemic, they are seeing fewer patients. They are currently seeing on average 64 patients per week, compared with the 78 patients they used to see weekly before the pandemic.

Dr. Hackell said that might be because pediatric offices are trying to make up the loss of revenue during the beginning of the pandemic, from the reduced number of well visits and immunizations, in the second half of the year with outreach.

“Since about June 2020, we’ve been making concerted efforts to remind parents that preventing other infectious diseases is critically important,” Dr. Hackell explained. “And so actually, for the second half of the year, many of us saw more well visits and immunization volume than in 2019 as we sought to make up the gap. It wasn’t that we were seeing more overall, but we’re trying to make up the gap that happened from March, April, May, [and] June.”

Most pediatricians find their work rewarding. One-third say the most rewarding part of their job is gratitude from and relationships with their patients. Meanwhile, 31% of pediatricians said knowing they are making the world a better place was a rewarding part of their job. Only 8% of them said making money was a rewarding part of their job.

Dr. Hackell said he did not go into pediatrics to make money, it was because he found it stimulating and has “no complaints.”

“I’ve been a pediatrician for 40 years and I wouldn’t do anything else,” Dr. Hackell said. “I don’t know that there’s anything that I would find as rewarding as the relationships that I’ve had over 40 years with my patients. You know, getting invited to weddings of kids who I saw when they were newborns is pretty impressive. It’s the gratification of having ongoing relationships with families.”

Furthermore, the report revealed that 77% of pediatricians said they would pick medicine again if they had a choice, and 82% said they would choose the same specialty.

The experts disclosed no relevant financial interests.

*This story was updated on 5/18/2021.

The average income for pediatricians declined slightly from 2019 to 2020, according to the Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2021.

The report, which was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021, found that the average pediatrician income was down $11,000 – from $232,000 in 2019 to $221,000 in 2020, with 48% of pediatricians reporting at least some decline in compensation.

The specialty also earned the least amount of money in 2020, compared with all of the other specialties, which isn’t surprising since pediatricians have been among the lowest-paid physician specialties since 2013. The highest-earning specialty was plastic surgery with an average income of $526,000 annually.

Most pediatricians who saw a drop in income cited pandemic-related issues such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients.

Jesse Hackell, MD, vice president and chief operating officer of Ponoma Pediatrics in New York, said in an interview the reduced wages pediatricians saw in 2020 didn’t surprise him because many pediatric offices saw a huge drop in visits that were not urgent.

“[The report] shows that procedural specialties tended to do a lot better than the nonprocedural specialties,” Dr. Hackell said. “That’s because, during the shutdown, if you broke your leg, you still needed the orthopedist. And even though the hospitals weren’t doing elective surgeries, they were certainly doing the emergency stuff.”

Meanwhile, in pediatrician offices, where Dr. Hackell said office visits dropped 70%-80% at the beginning of the pandemic, “parents weren’t going to bring a healthy kid out for routine visits and they weren’t going to bring a kid out for minor illnesses and expose them to possibly communicable diseases in the office.”

About 52% of pediatricians who lost income because of the pandemic believe their income levels will return to normal in 2-3 years. Meanwhile 30% of pediatricians expect their income to return to normal within a year, and 8% believe it will take 4 years for them to bounce back.

Physician work hours generally declined for some time during the pandemic, according to the report. However, most pediatricians are working about the same number of hours as they did before the pandemic, which is 47 hours per week.

Despite working the same number of hours per week that they did prepandemic, they are seeing fewer patients. They are currently seeing on average 64 patients per week, compared with the 78 patients they used to see weekly before the pandemic.

Dr. Hackell said that might be because pediatric offices are trying to make up the loss of revenue during the beginning of the pandemic, from the reduced number of well visits and immunizations, in the second half of the year with outreach.

“Since about June 2020, we’ve been making concerted efforts to remind parents that preventing other infectious diseases is critically important,” Dr. Hackell explained. “And so actually, for the second half of the year, many of us saw more well visits and immunization volume than in 2019 as we sought to make up the gap. It wasn’t that we were seeing more overall, but we’re trying to make up the gap that happened from March, April, May, [and] June.”

Most pediatricians find their work rewarding. One-third say the most rewarding part of their job is gratitude from and relationships with their patients. Meanwhile, 31% of pediatricians said knowing they are making the world a better place was a rewarding part of their job. Only 8% of them said making money was a rewarding part of their job.

Dr. Hackell said he did not go into pediatrics to make money, it was because he found it stimulating and has “no complaints.”

“I’ve been a pediatrician for 40 years and I wouldn’t do anything else,” Dr. Hackell said. “I don’t know that there’s anything that I would find as rewarding as the relationships that I’ve had over 40 years with my patients. You know, getting invited to weddings of kids who I saw when they were newborns is pretty impressive. It’s the gratification of having ongoing relationships with families.”

Furthermore, the report revealed that 77% of pediatricians said they would pick medicine again if they had a choice, and 82% said they would choose the same specialty.

The experts disclosed no relevant financial interests.

*This story was updated on 5/18/2021.

Are more naturopaths trying to compete with docs?

Jon Hislop, MD, PhD, hadn’t been in practice very long before patients began coming to him with requests to order tests that their naturopaths had recommended.

The family physician in North Vancouver, British Columbia, knew little about naturopathy but began researching it.

“I was finding that some of what the naturopaths were telling them was a little odd. Some of the tests they were asking for were unnecessary,” Dr. Hislop said.

The more he learned about naturopathy, the more appalled he became. He eventually took to Twitter, where he wages a campaign against naturopathy and alternative medicine.

“There is no alternative medicine,” he said. “There’s medicine and there’s other stuff. We need to stick to medicine and stay away from the other stuff.”

Dr. Hislop is not alone in his criticism of naturopathic medicine. Professional medical societies almost universally oppose naturopathy, but that has not stopped its spread or prevented it from becoming part of some health care systems.

Americans spent $30.2 billion on out-of-pocket complementary health care, according to a 2016 report from the National Institutes of Health. That includes everything from herbal supplements and massage therapy to chiropractic care.

What is naturopathic medicine?