User login

Patients need physicians who see – and feel – beyond the EMR

CHICAGO – Speaking to a rapt audience of radiologists, an infectious disease physician who writes and teaches about the importance of human touch in medicine held sway at the opening session of the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

It wasn’t hard for Abraham Verghese, MD, to find points of commonality between those who sit in dark reading rooms and those who roam the wards.

The EMR, Dr. Verghese said, is a “system of epic disaster. It was not designed for ease of use; it was designed for billing. ... Frankly, we are the highest-paid clerical workers in the hospital, and that has to change. The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stone; it ended because we had better ideas.”

The daily EMR click count for physicians has been estimated at 4,000, and it’s but part of the problem, said Dr. Verghese, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “For every hour of cumulative patient care, physicians spend 1½ hours on the computer, and another hour of our personal time at home dealing with our inbox,” he said. EMR systems may dominate clinical life for physicians, “but they were not built for our ease.”

Dr. Verghese is a practicing physician and medical educator, and is also the author of a body of fiction and nonfiction literature that delineates the physician-patient relationship. His TED-style talk followed opening remarks from Valerie Jackson, MD, the president of the Radiological Society of North America, who encouraged radiologists to reach out for a more direct connection with patients and with nonradiologist colleagues.

The patient connection – the human factor that leads many into the practice of medicine – can be eroded for myriad reasons, but health care systems that don’t elevate the physician-patient relationship do so at the peril of serious physician burnout, said Dr. Verghese. By some measures, and in some specialties, half of physicians score high on validated burnout indices – and a burned-out physician is at high risk for leaving the profession.

Dr. Verghese quoted the poet Anatole Broyard, who was treated for prostate cancer and wrote extensively about his experiences.

Wishing for a more personal connection with his physician, Mr. Broyard wrote: “I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps 5 minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh, to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way.”

It’s this opportunity for connection and contemplation that is sacrificed when, as Dr. Verghese said, “the patient in the bed has become a mere icon for the ‘real’ patient in the computer.”

Dr. Jackson, executive director of the American Board of Radiology, and Dr. Verghese both acknowledged that authentic patient connections can make practice more rewarding and reduce the risk of burnout.

Dr. Verghese also discussed other areas of risk when patients and their physicians are separated by an electronic divide.

“We are all getting distracted by our peripheral brains,” and patients may suffer when medical errors result from inattention and a reluctance to “trust what our eyes are showing us,” he said. He and his colleagues solicited and reported 208 vignettes of medical error. In 63% of the cases, the root cause of the error was failure to perform a physical examination (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1322-4.e3). “Patients have a front side – and a back side!” he said, to appreciative laughter. A careful physical exam, he said, involves inspecting – and palpating – both sides.

The act of putting hands on an unclothed patient for a physical exam would violate many societal norms, said Dr. Verghese, were it not for the special rules conferred on the physician-patient relationship.

“One individual in this dyad disrobes and allows touch. In any other context in this society, this is assault,” he said. “The very great privilege of our profession ... is that we are privileged to examine [patients’] bodies, and to touch.”

The gift of this ritual is not to be squandered, he said, adding that patients understand the special rhythm of the physical examination. “If you come in and do a half-assed probe of their belly and stick your stethoscope on top of their paper gown, they are on to you.”

Describing his own method for the physical exam, Dr. Verghese said that there’s something that feels commandeering and intrusive about beginning directly at the head, as one is taught. Instead, he offers an outstretched hand and begins with a handshake, noting grip strength, any tremor, hydration, and condition of skin and nails. Then, he caps the handshake with his other hand and slides two fingers over to the radial pulse, where he gathers more information, all the while strengthening his bond with his patient. His exam, he said, is his own, with its own rhythms and order which have not varied in decades.

Whatever the method, “this skill has to be passed on, and there is no easy way to do it. ... But when you examine well, you are preserving the ‘person-ality,’ the embodied identity of the patient.”

From the time of William Osler – and perhaps before – the physical examination has been a “symbolic centering on the body as a locus of personhood and disease,” said Dr. Verghese.

Dr. Jackson encouraged her radiologist peers to come out from the reading room to greet and connect with patients in the imaging suite. Similarly, Dr. Verghese said, technology can be used to “connect the image, or the biopsy report, or the lab test, to the personhood” of the patient. Bringing a tablet with imaging results or a laboratory readout to the bedside or the exam table and helping the patient place the findings on or within her own body marries the best of old and new.

He shared with the audience his practice for examining patients presenting with chronic fatigue – a condition that can be challenging to diagnose and manage.

These patients “come to you ready for you to join the long line of physicians who have disappointed them,” said Dr. Verghese, who at one time saw many such patients. He said that he developed a strategy of first listening, and then examining. “A very interesting thing happened – the voluble patient began to quiet down” under his examiner’s hands. If patients could, through his approach, relinquish their ceaseless quest for a definitive diagnosis “and instead begin a partnership toward wellness,” he felt he’d reached success. “It was because something magical had transpired in that encounter.”

Neither Dr. Verghese nor Dr. Jackson reported any conflicts of interest relevant to their presentations.

CHICAGO – Speaking to a rapt audience of radiologists, an infectious disease physician who writes and teaches about the importance of human touch in medicine held sway at the opening session of the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

It wasn’t hard for Abraham Verghese, MD, to find points of commonality between those who sit in dark reading rooms and those who roam the wards.

The EMR, Dr. Verghese said, is a “system of epic disaster. It was not designed for ease of use; it was designed for billing. ... Frankly, we are the highest-paid clerical workers in the hospital, and that has to change. The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stone; it ended because we had better ideas.”

The daily EMR click count for physicians has been estimated at 4,000, and it’s but part of the problem, said Dr. Verghese, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “For every hour of cumulative patient care, physicians spend 1½ hours on the computer, and another hour of our personal time at home dealing with our inbox,” he said. EMR systems may dominate clinical life for physicians, “but they were not built for our ease.”

Dr. Verghese is a practicing physician and medical educator, and is also the author of a body of fiction and nonfiction literature that delineates the physician-patient relationship. His TED-style talk followed opening remarks from Valerie Jackson, MD, the president of the Radiological Society of North America, who encouraged radiologists to reach out for a more direct connection with patients and with nonradiologist colleagues.

The patient connection – the human factor that leads many into the practice of medicine – can be eroded for myriad reasons, but health care systems that don’t elevate the physician-patient relationship do so at the peril of serious physician burnout, said Dr. Verghese. By some measures, and in some specialties, half of physicians score high on validated burnout indices – and a burned-out physician is at high risk for leaving the profession.

Dr. Verghese quoted the poet Anatole Broyard, who was treated for prostate cancer and wrote extensively about his experiences.

Wishing for a more personal connection with his physician, Mr. Broyard wrote: “I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps 5 minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh, to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way.”

It’s this opportunity for connection and contemplation that is sacrificed when, as Dr. Verghese said, “the patient in the bed has become a mere icon for the ‘real’ patient in the computer.”

Dr. Jackson, executive director of the American Board of Radiology, and Dr. Verghese both acknowledged that authentic patient connections can make practice more rewarding and reduce the risk of burnout.

Dr. Verghese also discussed other areas of risk when patients and their physicians are separated by an electronic divide.

“We are all getting distracted by our peripheral brains,” and patients may suffer when medical errors result from inattention and a reluctance to “trust what our eyes are showing us,” he said. He and his colleagues solicited and reported 208 vignettes of medical error. In 63% of the cases, the root cause of the error was failure to perform a physical examination (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1322-4.e3). “Patients have a front side – and a back side!” he said, to appreciative laughter. A careful physical exam, he said, involves inspecting – and palpating – both sides.

The act of putting hands on an unclothed patient for a physical exam would violate many societal norms, said Dr. Verghese, were it not for the special rules conferred on the physician-patient relationship.

“One individual in this dyad disrobes and allows touch. In any other context in this society, this is assault,” he said. “The very great privilege of our profession ... is that we are privileged to examine [patients’] bodies, and to touch.”

The gift of this ritual is not to be squandered, he said, adding that patients understand the special rhythm of the physical examination. “If you come in and do a half-assed probe of their belly and stick your stethoscope on top of their paper gown, they are on to you.”

Describing his own method for the physical exam, Dr. Verghese said that there’s something that feels commandeering and intrusive about beginning directly at the head, as one is taught. Instead, he offers an outstretched hand and begins with a handshake, noting grip strength, any tremor, hydration, and condition of skin and nails. Then, he caps the handshake with his other hand and slides two fingers over to the radial pulse, where he gathers more information, all the while strengthening his bond with his patient. His exam, he said, is his own, with its own rhythms and order which have not varied in decades.

Whatever the method, “this skill has to be passed on, and there is no easy way to do it. ... But when you examine well, you are preserving the ‘person-ality,’ the embodied identity of the patient.”

From the time of William Osler – and perhaps before – the physical examination has been a “symbolic centering on the body as a locus of personhood and disease,” said Dr. Verghese.

Dr. Jackson encouraged her radiologist peers to come out from the reading room to greet and connect with patients in the imaging suite. Similarly, Dr. Verghese said, technology can be used to “connect the image, or the biopsy report, or the lab test, to the personhood” of the patient. Bringing a tablet with imaging results or a laboratory readout to the bedside or the exam table and helping the patient place the findings on or within her own body marries the best of old and new.

He shared with the audience his practice for examining patients presenting with chronic fatigue – a condition that can be challenging to diagnose and manage.

These patients “come to you ready for you to join the long line of physicians who have disappointed them,” said Dr. Verghese, who at one time saw many such patients. He said that he developed a strategy of first listening, and then examining. “A very interesting thing happened – the voluble patient began to quiet down” under his examiner’s hands. If patients could, through his approach, relinquish their ceaseless quest for a definitive diagnosis “and instead begin a partnership toward wellness,” he felt he’d reached success. “It was because something magical had transpired in that encounter.”

Neither Dr. Verghese nor Dr. Jackson reported any conflicts of interest relevant to their presentations.

CHICAGO – Speaking to a rapt audience of radiologists, an infectious disease physician who writes and teaches about the importance of human touch in medicine held sway at the opening session of the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

It wasn’t hard for Abraham Verghese, MD, to find points of commonality between those who sit in dark reading rooms and those who roam the wards.

The EMR, Dr. Verghese said, is a “system of epic disaster. It was not designed for ease of use; it was designed for billing. ... Frankly, we are the highest-paid clerical workers in the hospital, and that has to change. The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stone; it ended because we had better ideas.”

The daily EMR click count for physicians has been estimated at 4,000, and it’s but part of the problem, said Dr. Verghese, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “For every hour of cumulative patient care, physicians spend 1½ hours on the computer, and another hour of our personal time at home dealing with our inbox,” he said. EMR systems may dominate clinical life for physicians, “but they were not built for our ease.”

Dr. Verghese is a practicing physician and medical educator, and is also the author of a body of fiction and nonfiction literature that delineates the physician-patient relationship. His TED-style talk followed opening remarks from Valerie Jackson, MD, the president of the Radiological Society of North America, who encouraged radiologists to reach out for a more direct connection with patients and with nonradiologist colleagues.

The patient connection – the human factor that leads many into the practice of medicine – can be eroded for myriad reasons, but health care systems that don’t elevate the physician-patient relationship do so at the peril of serious physician burnout, said Dr. Verghese. By some measures, and in some specialties, half of physicians score high on validated burnout indices – and a burned-out physician is at high risk for leaving the profession.

Dr. Verghese quoted the poet Anatole Broyard, who was treated for prostate cancer and wrote extensively about his experiences.

Wishing for a more personal connection with his physician, Mr. Broyard wrote: “I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps 5 minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh, to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way.”

It’s this opportunity for connection and contemplation that is sacrificed when, as Dr. Verghese said, “the patient in the bed has become a mere icon for the ‘real’ patient in the computer.”

Dr. Jackson, executive director of the American Board of Radiology, and Dr. Verghese both acknowledged that authentic patient connections can make practice more rewarding and reduce the risk of burnout.

Dr. Verghese also discussed other areas of risk when patients and their physicians are separated by an electronic divide.

“We are all getting distracted by our peripheral brains,” and patients may suffer when medical errors result from inattention and a reluctance to “trust what our eyes are showing us,” he said. He and his colleagues solicited and reported 208 vignettes of medical error. In 63% of the cases, the root cause of the error was failure to perform a physical examination (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1322-4.e3). “Patients have a front side – and a back side!” he said, to appreciative laughter. A careful physical exam, he said, involves inspecting – and palpating – both sides.

The act of putting hands on an unclothed patient for a physical exam would violate many societal norms, said Dr. Verghese, were it not for the special rules conferred on the physician-patient relationship.

“One individual in this dyad disrobes and allows touch. In any other context in this society, this is assault,” he said. “The very great privilege of our profession ... is that we are privileged to examine [patients’] bodies, and to touch.”

The gift of this ritual is not to be squandered, he said, adding that patients understand the special rhythm of the physical examination. “If you come in and do a half-assed probe of their belly and stick your stethoscope on top of their paper gown, they are on to you.”

Describing his own method for the physical exam, Dr. Verghese said that there’s something that feels commandeering and intrusive about beginning directly at the head, as one is taught. Instead, he offers an outstretched hand and begins with a handshake, noting grip strength, any tremor, hydration, and condition of skin and nails. Then, he caps the handshake with his other hand and slides two fingers over to the radial pulse, where he gathers more information, all the while strengthening his bond with his patient. His exam, he said, is his own, with its own rhythms and order which have not varied in decades.

Whatever the method, “this skill has to be passed on, and there is no easy way to do it. ... But when you examine well, you are preserving the ‘person-ality,’ the embodied identity of the patient.”

From the time of William Osler – and perhaps before – the physical examination has been a “symbolic centering on the body as a locus of personhood and disease,” said Dr. Verghese.

Dr. Jackson encouraged her radiologist peers to come out from the reading room to greet and connect with patients in the imaging suite. Similarly, Dr. Verghese said, technology can be used to “connect the image, or the biopsy report, or the lab test, to the personhood” of the patient. Bringing a tablet with imaging results or a laboratory readout to the bedside or the exam table and helping the patient place the findings on or within her own body marries the best of old and new.

He shared with the audience his practice for examining patients presenting with chronic fatigue – a condition that can be challenging to diagnose and manage.

These patients “come to you ready for you to join the long line of physicians who have disappointed them,” said Dr. Verghese, who at one time saw many such patients. He said that he developed a strategy of first listening, and then examining. “A very interesting thing happened – the voluble patient began to quiet down” under his examiner’s hands. If patients could, through his approach, relinquish their ceaseless quest for a definitive diagnosis “and instead begin a partnership toward wellness,” he felt he’d reached success. “It was because something magical had transpired in that encounter.”

Neither Dr. Verghese nor Dr. Jackson reported any conflicts of interest relevant to their presentations.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RSNA 2019

Docs push back on surprise billing compromise

Compromise bipartisan legislation to address surprise medical bills is getting push back from physician groups.

Leadership from the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee on Dec. 9 unveiled a compromise bill that includes rate-setting for small surprise billing and arbitration for larger ones at a lower threshold than what was originally proposed.

The new bill, part of a broader Lower Health Care Costs Act, would protect patients from surprise medical bills related to emergency care, holding them responsible for in-network cost-sharing rates for out-of-network care provided at an in-network facility without their informed consent. Out-of-network surprise bills would be applied to the patient’s in-network deductible.

Under the legislation, providers would be paid at minimum the local, market-based median in-network negotiated rate for services, with a median rate under a $750 threshold. When the median exceeds $750, the provider or insurer would be allowed to choose arbitration process to resolve payment disputes.

The bill also protects patients by banning out-of-network facilities and providers from sending balance bills for more than in-network cost-sharing amounts.

Physician groups, however, see the legislation as a giveback to insurers that puts health care professionals at a disadvantage when negotiating to be included in insurer networks.

At issue is the $750 threshold for optional arbitration.

“If you set the arbitration system in such a way that limits the ability of a physician to go to arbitration to settle a dispute between a health plan and the doctor, and if you say that can only be done when there [are] bills that are greater than $750 for a particular service, then the vast majority of services provided by doctors will not be able to go to arbitration,” Christian Shalgian, director of advocacy and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, said in an interview.

Cynthia Moran, executive vice president of government relations and health policy at the American College of Radiology, agreed.

“This particular product is going in a direction that we’re not comfortable with so we can’t support it on the basis of the benchmarks and the independent dispute resolution (IDR) process with the $750 threshold,” she said in an interview. The services radiologists provide tend to be in the $100-200 range, she said, so that would automatically exclude them from accessing arbitration. She also said that it is her understanding that many physician services will fall under that $750 threshold.

“That $750 is really going to mean that the vast majority of this policy is a benchmark-driven policy,” she said. “It is not going to be an IDR-driven policy and that is the crux of our objection to it.”

And by taking arbitration off the table, insurers have no incentive to negotiate in good faith with doctors to ensure that doctors are getting paid for the services they perform.

“For those situations where there is an out-of-network physician at an in-network facility, we believe that the patient should not have to pay any more for those emergency situations where they patient doesn’t get to choose their doctor,” Mr. Shalgian said. “The dispute really comes down to how much does the health plan have to pay the doctor.”

He noted that the legislation ties the rate to median in-network rates “and that’s a problem for us as well because of the fact that [this is] going to allow the health plans to set median in-network rates as the rate that they can pay the doctors.”

If the bill becomes law, “when you have a situation where you have an in-network physician trying to negotiate with a health plan to stay in network, that health plan now has more power in that negotiation because if [the physician] is making more than median in-network rates, then the health plan can say, ‘go out of network because we will just pay you median in-network’ at that point. That is a significant concern to us as well.”

Mr. Shalgian said that the ideal solution would be to eliminate the threshold entirely and just send disputes to arbitration. Recognizing that it might not be practical, the $750 threshold should be lowered.

ACS supported a $300 threshold, he added.

The bill is expected to be tacked on to one of the mandatory spending bills that Congress needs to pass by the end of the year.

The $750 threshold would be a savings generator for the government and an important bill such as this should be passed on its own merits, Mr. Shalgian said.

Ms. Moran called for Congress to take its time with the legislation.

“We do think that this whole issue needs more time for everyone to understand what the impact is on this first run of the solution and we think it should be slowed down a bit,” she said. “It should not go to the floor until you hear more from the providers [after] the providers figure out what the impact will be.”

The American Medical Association also called for Congress to slow down.

“The current proposal relies on benchmark rate setting that would serve only to benefit the bottom line of insurance companies at the expense of patients seeking a robust network of physicians for their care,” AMA President Patrice Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Rather than rushing to meet arbitrary deadlines, it is important to get this legislation right.”

Compromise bipartisan legislation to address surprise medical bills is getting push back from physician groups.

Leadership from the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee on Dec. 9 unveiled a compromise bill that includes rate-setting for small surprise billing and arbitration for larger ones at a lower threshold than what was originally proposed.

The new bill, part of a broader Lower Health Care Costs Act, would protect patients from surprise medical bills related to emergency care, holding them responsible for in-network cost-sharing rates for out-of-network care provided at an in-network facility without their informed consent. Out-of-network surprise bills would be applied to the patient’s in-network deductible.

Under the legislation, providers would be paid at minimum the local, market-based median in-network negotiated rate for services, with a median rate under a $750 threshold. When the median exceeds $750, the provider or insurer would be allowed to choose arbitration process to resolve payment disputes.

The bill also protects patients by banning out-of-network facilities and providers from sending balance bills for more than in-network cost-sharing amounts.

Physician groups, however, see the legislation as a giveback to insurers that puts health care professionals at a disadvantage when negotiating to be included in insurer networks.

At issue is the $750 threshold for optional arbitration.

“If you set the arbitration system in such a way that limits the ability of a physician to go to arbitration to settle a dispute between a health plan and the doctor, and if you say that can only be done when there [are] bills that are greater than $750 for a particular service, then the vast majority of services provided by doctors will not be able to go to arbitration,” Christian Shalgian, director of advocacy and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, said in an interview.

Cynthia Moran, executive vice president of government relations and health policy at the American College of Radiology, agreed.

“This particular product is going in a direction that we’re not comfortable with so we can’t support it on the basis of the benchmarks and the independent dispute resolution (IDR) process with the $750 threshold,” she said in an interview. The services radiologists provide tend to be in the $100-200 range, she said, so that would automatically exclude them from accessing arbitration. She also said that it is her understanding that many physician services will fall under that $750 threshold.

“That $750 is really going to mean that the vast majority of this policy is a benchmark-driven policy,” she said. “It is not going to be an IDR-driven policy and that is the crux of our objection to it.”

And by taking arbitration off the table, insurers have no incentive to negotiate in good faith with doctors to ensure that doctors are getting paid for the services they perform.

“For those situations where there is an out-of-network physician at an in-network facility, we believe that the patient should not have to pay any more for those emergency situations where they patient doesn’t get to choose their doctor,” Mr. Shalgian said. “The dispute really comes down to how much does the health plan have to pay the doctor.”

He noted that the legislation ties the rate to median in-network rates “and that’s a problem for us as well because of the fact that [this is] going to allow the health plans to set median in-network rates as the rate that they can pay the doctors.”

If the bill becomes law, “when you have a situation where you have an in-network physician trying to negotiate with a health plan to stay in network, that health plan now has more power in that negotiation because if [the physician] is making more than median in-network rates, then the health plan can say, ‘go out of network because we will just pay you median in-network’ at that point. That is a significant concern to us as well.”

Mr. Shalgian said that the ideal solution would be to eliminate the threshold entirely and just send disputes to arbitration. Recognizing that it might not be practical, the $750 threshold should be lowered.

ACS supported a $300 threshold, he added.

The bill is expected to be tacked on to one of the mandatory spending bills that Congress needs to pass by the end of the year.

The $750 threshold would be a savings generator for the government and an important bill such as this should be passed on its own merits, Mr. Shalgian said.

Ms. Moran called for Congress to take its time with the legislation.

“We do think that this whole issue needs more time for everyone to understand what the impact is on this first run of the solution and we think it should be slowed down a bit,” she said. “It should not go to the floor until you hear more from the providers [after] the providers figure out what the impact will be.”

The American Medical Association also called for Congress to slow down.

“The current proposal relies on benchmark rate setting that would serve only to benefit the bottom line of insurance companies at the expense of patients seeking a robust network of physicians for their care,” AMA President Patrice Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Rather than rushing to meet arbitrary deadlines, it is important to get this legislation right.”

Compromise bipartisan legislation to address surprise medical bills is getting push back from physician groups.

Leadership from the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee on Dec. 9 unveiled a compromise bill that includes rate-setting for small surprise billing and arbitration for larger ones at a lower threshold than what was originally proposed.

The new bill, part of a broader Lower Health Care Costs Act, would protect patients from surprise medical bills related to emergency care, holding them responsible for in-network cost-sharing rates for out-of-network care provided at an in-network facility without their informed consent. Out-of-network surprise bills would be applied to the patient’s in-network deductible.

Under the legislation, providers would be paid at minimum the local, market-based median in-network negotiated rate for services, with a median rate under a $750 threshold. When the median exceeds $750, the provider or insurer would be allowed to choose arbitration process to resolve payment disputes.

The bill also protects patients by banning out-of-network facilities and providers from sending balance bills for more than in-network cost-sharing amounts.

Physician groups, however, see the legislation as a giveback to insurers that puts health care professionals at a disadvantage when negotiating to be included in insurer networks.

At issue is the $750 threshold for optional arbitration.

“If you set the arbitration system in such a way that limits the ability of a physician to go to arbitration to settle a dispute between a health plan and the doctor, and if you say that can only be done when there [are] bills that are greater than $750 for a particular service, then the vast majority of services provided by doctors will not be able to go to arbitration,” Christian Shalgian, director of advocacy and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, said in an interview.

Cynthia Moran, executive vice president of government relations and health policy at the American College of Radiology, agreed.

“This particular product is going in a direction that we’re not comfortable with so we can’t support it on the basis of the benchmarks and the independent dispute resolution (IDR) process with the $750 threshold,” she said in an interview. The services radiologists provide tend to be in the $100-200 range, she said, so that would automatically exclude them from accessing arbitration. She also said that it is her understanding that many physician services will fall under that $750 threshold.

“That $750 is really going to mean that the vast majority of this policy is a benchmark-driven policy,” she said. “It is not going to be an IDR-driven policy and that is the crux of our objection to it.”

And by taking arbitration off the table, insurers have no incentive to negotiate in good faith with doctors to ensure that doctors are getting paid for the services they perform.

“For those situations where there is an out-of-network physician at an in-network facility, we believe that the patient should not have to pay any more for those emergency situations where they patient doesn’t get to choose their doctor,” Mr. Shalgian said. “The dispute really comes down to how much does the health plan have to pay the doctor.”

He noted that the legislation ties the rate to median in-network rates “and that’s a problem for us as well because of the fact that [this is] going to allow the health plans to set median in-network rates as the rate that they can pay the doctors.”

If the bill becomes law, “when you have a situation where you have an in-network physician trying to negotiate with a health plan to stay in network, that health plan now has more power in that negotiation because if [the physician] is making more than median in-network rates, then the health plan can say, ‘go out of network because we will just pay you median in-network’ at that point. That is a significant concern to us as well.”

Mr. Shalgian said that the ideal solution would be to eliminate the threshold entirely and just send disputes to arbitration. Recognizing that it might not be practical, the $750 threshold should be lowered.

ACS supported a $300 threshold, he added.

The bill is expected to be tacked on to one of the mandatory spending bills that Congress needs to pass by the end of the year.

The $750 threshold would be a savings generator for the government and an important bill such as this should be passed on its own merits, Mr. Shalgian said.

Ms. Moran called for Congress to take its time with the legislation.

“We do think that this whole issue needs more time for everyone to understand what the impact is on this first run of the solution and we think it should be slowed down a bit,” she said. “It should not go to the floor until you hear more from the providers [after] the providers figure out what the impact will be.”

The American Medical Association also called for Congress to slow down.

“The current proposal relies on benchmark rate setting that would serve only to benefit the bottom line of insurance companies at the expense of patients seeking a robust network of physicians for their care,” AMA President Patrice Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Rather than rushing to meet arbitrary deadlines, it is important to get this legislation right.”

Study: More pediatricians participating in global health opportunities

A look across nearly 3 decades finds that

Lead author Kevin Chan, MD, MPH, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues analyzed the responses of 668 pediatricians from the 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey and compared the data with responses from 638 pediatricians collected in the 1989 periodic survey about pediatricians’ global health experiences and interests. Findings showed that participation in global health activities rose from 2% in 1989 to 5% in 2017, while interest in future global health experiences grew from 25% in 1989 to 32% in 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics.

Notable increases in global health participation were found in women (1% in 1989 to 5% in 2017) and men (3% in 1989 to 6% in 2017), subspecialists (3% in 1989 to 9% in 2017), and pediatricians who worked in medical school, hospital, or clinic settings (3% in 1989 to 8% in 2017).

In terms of age, pediatricians 50 years or older had a higher rate of a recent global health experience, with the largest increase in global health participation occurring in pediatricians 60 years and older (2% in 1989 to 9% in 2017), the study found.

Similarly, interest in future global health activities increased during the same time period for male and female pediatricians, for generalists and subspecialists, and for those working in medical school, hospital, or clinic settings. Clinical care and teaching settings were the most common preferences for future global health experiences in both 1989 and 2017. Administration and research were the least likely selected preferences in both surveys. Pediatricians affiliated with an academic institution, hospital, or clinic were more likely to have recently engaged in a global health activity and also were more likely express interest in such an opportunity, compared with solo pediatricians or those in small practices.

In an editorial accompanying the article, Suzinne Pak-Gorstein, MD, MPH, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said that the study highlights the importance of preparation for pediatricians who seek global health opportunities, particularly experiences that are short term.

“Ethical approaches to international work should be thoughtful and intentional, such as deciding to work with organizations that offer short-term experiences only in the context of long-term partnerships, considering the burden on local partners for hosting visitors, and insisting on a commitment to equitable collaborations that are mutually beneficial,” she wrote.

Dr. Pak-Gorstein added that future innovations in global health education can inspire learning experiences for pediatricians that utilize their passion and enthusiasm, while also enabling them to become more globally minded.

“In this way, pediatricians can be empowered to understand the world’s daunting challenges; respect cultural, religious, and socioeconomic differences; and facilitate dialogue and solutions for improving child health worldwide,” she concluded.

The survey was funded by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Pak-Gorstein said she received no funding for the editorial and had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chan K et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Dec 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1655.

A look across nearly 3 decades finds that

Lead author Kevin Chan, MD, MPH, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues analyzed the responses of 668 pediatricians from the 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey and compared the data with responses from 638 pediatricians collected in the 1989 periodic survey about pediatricians’ global health experiences and interests. Findings showed that participation in global health activities rose from 2% in 1989 to 5% in 2017, while interest in future global health experiences grew from 25% in 1989 to 32% in 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics.

Notable increases in global health participation were found in women (1% in 1989 to 5% in 2017) and men (3% in 1989 to 6% in 2017), subspecialists (3% in 1989 to 9% in 2017), and pediatricians who worked in medical school, hospital, or clinic settings (3% in 1989 to 8% in 2017).

In terms of age, pediatricians 50 years or older had a higher rate of a recent global health experience, with the largest increase in global health participation occurring in pediatricians 60 years and older (2% in 1989 to 9% in 2017), the study found.

Similarly, interest in future global health activities increased during the same time period for male and female pediatricians, for generalists and subspecialists, and for those working in medical school, hospital, or clinic settings. Clinical care and teaching settings were the most common preferences for future global health experiences in both 1989 and 2017. Administration and research were the least likely selected preferences in both surveys. Pediatricians affiliated with an academic institution, hospital, or clinic were more likely to have recently engaged in a global health activity and also were more likely express interest in such an opportunity, compared with solo pediatricians or those in small practices.

In an editorial accompanying the article, Suzinne Pak-Gorstein, MD, MPH, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said that the study highlights the importance of preparation for pediatricians who seek global health opportunities, particularly experiences that are short term.

“Ethical approaches to international work should be thoughtful and intentional, such as deciding to work with organizations that offer short-term experiences only in the context of long-term partnerships, considering the burden on local partners for hosting visitors, and insisting on a commitment to equitable collaborations that are mutually beneficial,” she wrote.

Dr. Pak-Gorstein added that future innovations in global health education can inspire learning experiences for pediatricians that utilize their passion and enthusiasm, while also enabling them to become more globally minded.

“In this way, pediatricians can be empowered to understand the world’s daunting challenges; respect cultural, religious, and socioeconomic differences; and facilitate dialogue and solutions for improving child health worldwide,” she concluded.

The survey was funded by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Pak-Gorstein said she received no funding for the editorial and had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chan K et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Dec 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1655.

A look across nearly 3 decades finds that

Lead author Kevin Chan, MD, MPH, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues analyzed the responses of 668 pediatricians from the 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey and compared the data with responses from 638 pediatricians collected in the 1989 periodic survey about pediatricians’ global health experiences and interests. Findings showed that participation in global health activities rose from 2% in 1989 to 5% in 2017, while interest in future global health experiences grew from 25% in 1989 to 32% in 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics.

Notable increases in global health participation were found in women (1% in 1989 to 5% in 2017) and men (3% in 1989 to 6% in 2017), subspecialists (3% in 1989 to 9% in 2017), and pediatricians who worked in medical school, hospital, or clinic settings (3% in 1989 to 8% in 2017).

In terms of age, pediatricians 50 years or older had a higher rate of a recent global health experience, with the largest increase in global health participation occurring in pediatricians 60 years and older (2% in 1989 to 9% in 2017), the study found.

Similarly, interest in future global health activities increased during the same time period for male and female pediatricians, for generalists and subspecialists, and for those working in medical school, hospital, or clinic settings. Clinical care and teaching settings were the most common preferences for future global health experiences in both 1989 and 2017. Administration and research were the least likely selected preferences in both surveys. Pediatricians affiliated with an academic institution, hospital, or clinic were more likely to have recently engaged in a global health activity and also were more likely express interest in such an opportunity, compared with solo pediatricians or those in small practices.

In an editorial accompanying the article, Suzinne Pak-Gorstein, MD, MPH, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said that the study highlights the importance of preparation for pediatricians who seek global health opportunities, particularly experiences that are short term.

“Ethical approaches to international work should be thoughtful and intentional, such as deciding to work with organizations that offer short-term experiences only in the context of long-term partnerships, considering the burden on local partners for hosting visitors, and insisting on a commitment to equitable collaborations that are mutually beneficial,” she wrote.

Dr. Pak-Gorstein added that future innovations in global health education can inspire learning experiences for pediatricians that utilize their passion and enthusiasm, while also enabling them to become more globally minded.

“In this way, pediatricians can be empowered to understand the world’s daunting challenges; respect cultural, religious, and socioeconomic differences; and facilitate dialogue and solutions for improving child health worldwide,” she concluded.

The survey was funded by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Pak-Gorstein said she received no funding for the editorial and had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chan K et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Dec 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1655.

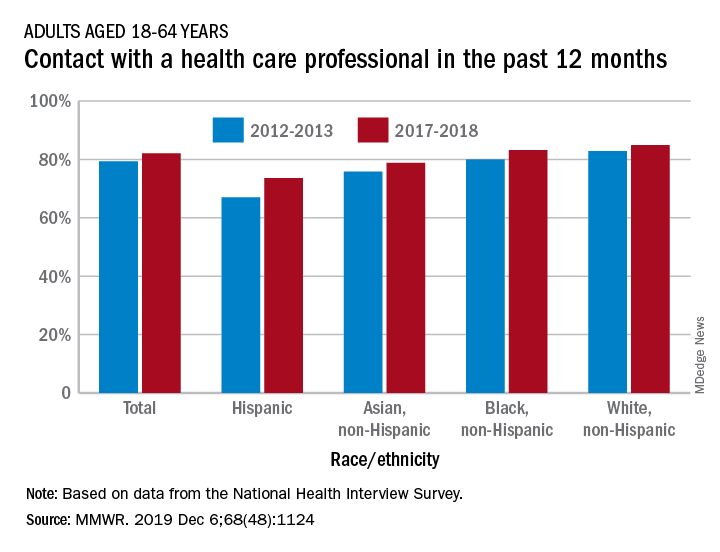

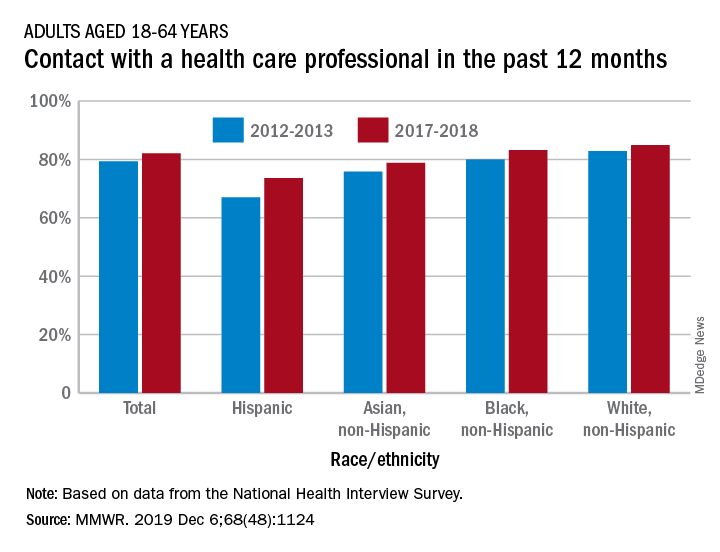

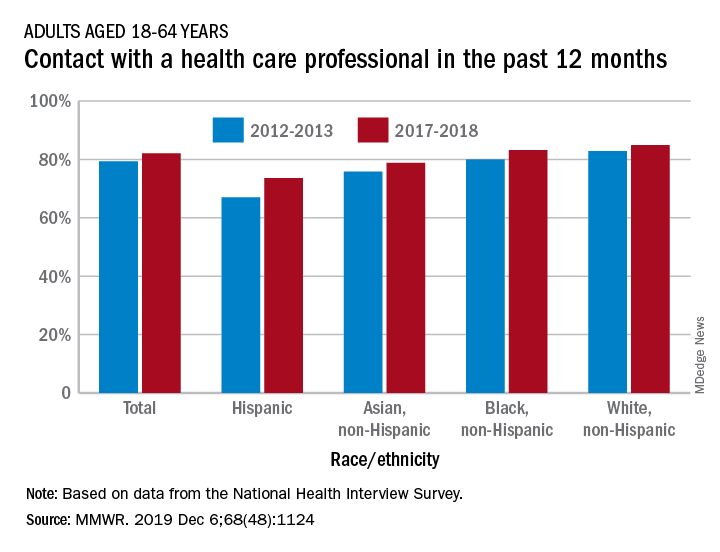

Contacts with health care professionals increased among adults

Adults aged 18-64 years were more likely to see or talk to a health care professional in 2017-2018 than they were in 2012-2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of American adults who had seen or talked to a health care professional in the past 12 months rose from 79.3% in 2012-2013 to 82.1% in 2017-2018, Michael E. Martinez, MPH, and Tainya C. Clarke, PhD, reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Analysis by race/ethnicity showed that Hispanic adults were still the least likely to have seen or talked to a health care professional in 2017-2018, even though they had the largest increase – more than six percentage points – between the two time periods, the CDC investigators reported.

White adults were the most likely to have seen or talked to a health care provider in both 2012-2013 and 2017-2018 but their 2.1-percentage-point increase over the course of the analysis was the smallest of the four groups included, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

SOURCE: Martinez ME, Clarke TC. MMWR. 2019 Dec 6;68(48):1124.

Adults aged 18-64 years were more likely to see or talk to a health care professional in 2017-2018 than they were in 2012-2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of American adults who had seen or talked to a health care professional in the past 12 months rose from 79.3% in 2012-2013 to 82.1% in 2017-2018, Michael E. Martinez, MPH, and Tainya C. Clarke, PhD, reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Analysis by race/ethnicity showed that Hispanic adults were still the least likely to have seen or talked to a health care professional in 2017-2018, even though they had the largest increase – more than six percentage points – between the two time periods, the CDC investigators reported.

White adults were the most likely to have seen or talked to a health care provider in both 2012-2013 and 2017-2018 but their 2.1-percentage-point increase over the course of the analysis was the smallest of the four groups included, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

SOURCE: Martinez ME, Clarke TC. MMWR. 2019 Dec 6;68(48):1124.

Adults aged 18-64 years were more likely to see or talk to a health care professional in 2017-2018 than they were in 2012-2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of American adults who had seen or talked to a health care professional in the past 12 months rose from 79.3% in 2012-2013 to 82.1% in 2017-2018, Michael E. Martinez, MPH, and Tainya C. Clarke, PhD, reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Analysis by race/ethnicity showed that Hispanic adults were still the least likely to have seen or talked to a health care professional in 2017-2018, even though they had the largest increase – more than six percentage points – between the two time periods, the CDC investigators reported.

White adults were the most likely to have seen or talked to a health care provider in both 2012-2013 and 2017-2018 but their 2.1-percentage-point increase over the course of the analysis was the smallest of the four groups included, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

SOURCE: Martinez ME, Clarke TC. MMWR. 2019 Dec 6;68(48):1124.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Negligent use of steroids

Question: Mr. M, a car mechanic, was treated with long-term ACTH and Kenalog after he developed severe contact dermatitis from daily exposure to petroleum-based solvents. His subsequent course was complicated by cataracts and osteoporosis. Which of the following is true in case he files a malpractice action?

A. Treatment with steroids was medically indicated for Mr. Mechanic’s dermatologic condition, so the doctor could not have breached the standard of care.

B. Under the “Learned Intermediary” doctrine, both the manufacturer and the prescribing doctor are jointly liable.

C. Corticosteroids are a known cause of osteoporosis and other complications, but not of cataracts, so that part of the malpractice action should be thrown out.

D. The plaintiff would prevail even if he could not find an expert witnesses to testify as to standard of care, since it is “common knowledge” that steroids cause osteoporosis.

E. Lack of informed consent may be his best legal theory of liability, as many jurisdictions now use the patient-centered standard, which does not require expert testimony.

Answer: E. The above hypothetical was modified from an old Montana case1 in which the patient failed in his negligence lawsuit because he did not have expert witnesses to testify as to standard of care and to adequacy of warning label. However, in some jurisdictions under today’s case law, informed consent relies on a subjective, i.e., patient-oriented standard, and expert testimony is unnecessary to prove breach of duty, although still needed to prove causation.

Steroid-related litigation

Steroid-related malpractice litigation is quite prevalent. In a retrospective study of a tertiary medical center from 1996 to 2008, Nash and coworkers identified 83 such cases.2 Steroids were prescribed for pain (23%), asthma or another pulmonary condition (20%), a dermatologic condition (18%), an autoimmune condition (17%), or allergies (6%).

Learned intermediary

“Drug reps” have a responsibility to inform doctors of both benefits and risks of their medications, a process termed “fair balance.” Generally speaking, if a doctor fails to warn the patient of a medication risk, and injury results, the patient may have a claim against the doctor but not the drug manufacturer. This is termed the “learned intermediary” doctrine, which is also applicable to medical devices such as dialysis equipment, breast implants, and blood products.

The justification is that manufacturers can reasonably rely on the treating doctor to warn of adverse effects, which are disclosed to the profession through their sales reps and in the package insert and PDR. The treating doctor, in turn, is expected to use his or her professional judgment to adequately warn the patient. It is simply not feasible for the manufacturer to directly warn every patient without usurping the doctor-patient relationship. However, where known complications were undisclosed to the FDA and the profession, then plaintiff attorneys can file class action lawsuits directed at the manufacturer.

Complications

Complications arising out of the use of steroids are typical examples of medical products liability. This may be on the basis of the doctor having prescribed the medication without a proper indication or where contraindicated, or may have prescribed “the wrong dose for the wrong patient by the wrong route.” In addition, there may have been a lack of informed consent, i.e., failure to explain the underlying condition and the material risks associated with using the drug. Other acts of negligence, e.g., vicarious liability, may also apply.

Corticosteroids such as Prednisone, Decadron, Kenalog, etc., are widely prescribed, and can cause serious complications, especially when used in high doses for extended periods. Examples include suppression of the immune system with supervening infections, steroid osteoporosis and fractures,3 aseptic necrosis, steroid diabetes, hypertension, emotional changes, weight gain, cataracts, neurological complications, and many others. As in all malpractice actions, the plaintiff bears the burden of proof covering the four requisite tort elements, i.e., duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages. Expert testimony is almost always needed in a professional negligence lawsuit.

Aseptic necrosis is a feared complication of steroid therapy.

A recent report4 featured a nurse in her 40s who developed aseptic necrosis of the right shoulder and both hips after taking high dose prednisone for 6 months. She was being treated for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura by a hematologist as well as sarcoidosis by a pulmonologist. The plaintiff claimed that both defendants negligently prescribed the medication for an extended period of time without proper monitoring, which caused her severe bone complications requiring a hip and shoulder replacement. The defendants maintained that the steroid medication was necessary to treat the life-threatening conditions from which the plaintiff suffered and that the dosage was carefully monitored and was not excessive. However, in a jury trial, the defendant hematologist and pulmonologist were each found 50% negligent, and the patient was awarded $4.1 million in damages.

In a case5 of steroid-related neurological sequelae, a Colorado jury awarded $14.9 million to a couple against an outpatient surgery center for negligently administering an epidural dose of Kenalog that rendered the patient paraplegic, and for failure to obtain informed consent. The jury awarded the woman, age 57, approximately $1.7 million in past and future medical expenses; $3.2 million in unspecified economic damages; and $6.5 million in past and future noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering. Her husband will receive $3.5 million in past and future noneconomic damages for loss of consortium, according to the verdict. Two years before the injection date of 2013, the drug maker had announced that Kenalog should not be used for epidural procedures because of cord complications including infarction and paraplegia.

Contributory role

The putative offending drug does not have to be the sole cause of injury; if it played a contributory role, the court may find the presence of liability. For example, a Kansas appeals court6 upheld a jury award of $2.88 million in the case of a 40-year-old man who took his life after neurologic complications followed an epidural injection. During one of patient’s visits for chronic low back pain, the defendant-anesthesiologist administered an epidural steroid injection into an area left swollen from a previous injection.

The patient developed neurologic symptoms, and lumbar puncture yielded green pus caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. He went on to develop arachnoiditis, which left him with impotence, incontinence, and excruciating pain. His lawsuit contended the injection needle had passed through an infected edematous area, causing meningitis and arachnoiditis. Before the case went to trial, the patient took his life because of unremitting pain.

In March 2014, a Johnson County jury found the doctor 75% at fault and the clinic 25% at fault and awarded damages, which were reduced to $1.67 million because Kansas caps noneconomic damages at $250,000. The court rejected the defendants’ argument that the trial judge improperly instructed the jury it could find liability only if negligence “caused” rather than merely “contributed to” the patient’s death, holding that “... one who contributes to a wrongful death is a cause of that death as contemplated by the wrongful death statute.”

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu .

References

1. Hill v. Squibb Sons, E.R, 592 P.2d 1383 (Mont. 1979).

2. Nash JJ et al, Medical malpractice and corticosteroid use. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011; 144:10-5.

3. Buckley L. et al, Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:2547-56.

4. Zarin’s Jury Verdict: Review and Analysis. Article ID 40229, Philadelphia County.

5. Robbin Smith et al. v. The Surgery Center at Lone Tree, 2015-CV-30922, Douglas County District Court, Colo. Verdict for plaintiff, March 23, 2017.

6. Burnette v. Kimber L. Eubanks, M.D., & Paincare, P.A., 379 P.3d 372 (Kan. Ct. App. 2016).

Question: Mr. M, a car mechanic, was treated with long-term ACTH and Kenalog after he developed severe contact dermatitis from daily exposure to petroleum-based solvents. His subsequent course was complicated by cataracts and osteoporosis. Which of the following is true in case he files a malpractice action?

A. Treatment with steroids was medically indicated for Mr. Mechanic’s dermatologic condition, so the doctor could not have breached the standard of care.

B. Under the “Learned Intermediary” doctrine, both the manufacturer and the prescribing doctor are jointly liable.

C. Corticosteroids are a known cause of osteoporosis and other complications, but not of cataracts, so that part of the malpractice action should be thrown out.

D. The plaintiff would prevail even if he could not find an expert witnesses to testify as to standard of care, since it is “common knowledge” that steroids cause osteoporosis.

E. Lack of informed consent may be his best legal theory of liability, as many jurisdictions now use the patient-centered standard, which does not require expert testimony.

Answer: E. The above hypothetical was modified from an old Montana case1 in which the patient failed in his negligence lawsuit because he did not have expert witnesses to testify as to standard of care and to adequacy of warning label. However, in some jurisdictions under today’s case law, informed consent relies on a subjective, i.e., patient-oriented standard, and expert testimony is unnecessary to prove breach of duty, although still needed to prove causation.

Steroid-related litigation

Steroid-related malpractice litigation is quite prevalent. In a retrospective study of a tertiary medical center from 1996 to 2008, Nash and coworkers identified 83 such cases.2 Steroids were prescribed for pain (23%), asthma or another pulmonary condition (20%), a dermatologic condition (18%), an autoimmune condition (17%), or allergies (6%).

Learned intermediary

“Drug reps” have a responsibility to inform doctors of both benefits and risks of their medications, a process termed “fair balance.” Generally speaking, if a doctor fails to warn the patient of a medication risk, and injury results, the patient may have a claim against the doctor but not the drug manufacturer. This is termed the “learned intermediary” doctrine, which is also applicable to medical devices such as dialysis equipment, breast implants, and blood products.

The justification is that manufacturers can reasonably rely on the treating doctor to warn of adverse effects, which are disclosed to the profession through their sales reps and in the package insert and PDR. The treating doctor, in turn, is expected to use his or her professional judgment to adequately warn the patient. It is simply not feasible for the manufacturer to directly warn every patient without usurping the doctor-patient relationship. However, where known complications were undisclosed to the FDA and the profession, then plaintiff attorneys can file class action lawsuits directed at the manufacturer.

Complications

Complications arising out of the use of steroids are typical examples of medical products liability. This may be on the basis of the doctor having prescribed the medication without a proper indication or where contraindicated, or may have prescribed “the wrong dose for the wrong patient by the wrong route.” In addition, there may have been a lack of informed consent, i.e., failure to explain the underlying condition and the material risks associated with using the drug. Other acts of negligence, e.g., vicarious liability, may also apply.

Corticosteroids such as Prednisone, Decadron, Kenalog, etc., are widely prescribed, and can cause serious complications, especially when used in high doses for extended periods. Examples include suppression of the immune system with supervening infections, steroid osteoporosis and fractures,3 aseptic necrosis, steroid diabetes, hypertension, emotional changes, weight gain, cataracts, neurological complications, and many others. As in all malpractice actions, the plaintiff bears the burden of proof covering the four requisite tort elements, i.e., duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages. Expert testimony is almost always needed in a professional negligence lawsuit.

Aseptic necrosis is a feared complication of steroid therapy.

A recent report4 featured a nurse in her 40s who developed aseptic necrosis of the right shoulder and both hips after taking high dose prednisone for 6 months. She was being treated for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura by a hematologist as well as sarcoidosis by a pulmonologist. The plaintiff claimed that both defendants negligently prescribed the medication for an extended period of time without proper monitoring, which caused her severe bone complications requiring a hip and shoulder replacement. The defendants maintained that the steroid medication was necessary to treat the life-threatening conditions from which the plaintiff suffered and that the dosage was carefully monitored and was not excessive. However, in a jury trial, the defendant hematologist and pulmonologist were each found 50% negligent, and the patient was awarded $4.1 million in damages.

In a case5 of steroid-related neurological sequelae, a Colorado jury awarded $14.9 million to a couple against an outpatient surgery center for negligently administering an epidural dose of Kenalog that rendered the patient paraplegic, and for failure to obtain informed consent. The jury awarded the woman, age 57, approximately $1.7 million in past and future medical expenses; $3.2 million in unspecified economic damages; and $6.5 million in past and future noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering. Her husband will receive $3.5 million in past and future noneconomic damages for loss of consortium, according to the verdict. Two years before the injection date of 2013, the drug maker had announced that Kenalog should not be used for epidural procedures because of cord complications including infarction and paraplegia.

Contributory role

The putative offending drug does not have to be the sole cause of injury; if it played a contributory role, the court may find the presence of liability. For example, a Kansas appeals court6 upheld a jury award of $2.88 million in the case of a 40-year-old man who took his life after neurologic complications followed an epidural injection. During one of patient’s visits for chronic low back pain, the defendant-anesthesiologist administered an epidural steroid injection into an area left swollen from a previous injection.

The patient developed neurologic symptoms, and lumbar puncture yielded green pus caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. He went on to develop arachnoiditis, which left him with impotence, incontinence, and excruciating pain. His lawsuit contended the injection needle had passed through an infected edematous area, causing meningitis and arachnoiditis. Before the case went to trial, the patient took his life because of unremitting pain.

In March 2014, a Johnson County jury found the doctor 75% at fault and the clinic 25% at fault and awarded damages, which were reduced to $1.67 million because Kansas caps noneconomic damages at $250,000. The court rejected the defendants’ argument that the trial judge improperly instructed the jury it could find liability only if negligence “caused” rather than merely “contributed to” the patient’s death, holding that “... one who contributes to a wrongful death is a cause of that death as contemplated by the wrongful death statute.”

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu .

References

1. Hill v. Squibb Sons, E.R, 592 P.2d 1383 (Mont. 1979).

2. Nash JJ et al, Medical malpractice and corticosteroid use. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011; 144:10-5.

3. Buckley L. et al, Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:2547-56.

4. Zarin’s Jury Verdict: Review and Analysis. Article ID 40229, Philadelphia County.

5. Robbin Smith et al. v. The Surgery Center at Lone Tree, 2015-CV-30922, Douglas County District Court, Colo. Verdict for plaintiff, March 23, 2017.

6. Burnette v. Kimber L. Eubanks, M.D., & Paincare, P.A., 379 P.3d 372 (Kan. Ct. App. 2016).

Question: Mr. M, a car mechanic, was treated with long-term ACTH and Kenalog after he developed severe contact dermatitis from daily exposure to petroleum-based solvents. His subsequent course was complicated by cataracts and osteoporosis. Which of the following is true in case he files a malpractice action?

A. Treatment with steroids was medically indicated for Mr. Mechanic’s dermatologic condition, so the doctor could not have breached the standard of care.

B. Under the “Learned Intermediary” doctrine, both the manufacturer and the prescribing doctor are jointly liable.

C. Corticosteroids are a known cause of osteoporosis and other complications, but not of cataracts, so that part of the malpractice action should be thrown out.

D. The plaintiff would prevail even if he could not find an expert witnesses to testify as to standard of care, since it is “common knowledge” that steroids cause osteoporosis.

E. Lack of informed consent may be his best legal theory of liability, as many jurisdictions now use the patient-centered standard, which does not require expert testimony.

Answer: E. The above hypothetical was modified from an old Montana case1 in which the patient failed in his negligence lawsuit because he did not have expert witnesses to testify as to standard of care and to adequacy of warning label. However, in some jurisdictions under today’s case law, informed consent relies on a subjective, i.e., patient-oriented standard, and expert testimony is unnecessary to prove breach of duty, although still needed to prove causation.

Steroid-related litigation

Steroid-related malpractice litigation is quite prevalent. In a retrospective study of a tertiary medical center from 1996 to 2008, Nash and coworkers identified 83 such cases.2 Steroids were prescribed for pain (23%), asthma or another pulmonary condition (20%), a dermatologic condition (18%), an autoimmune condition (17%), or allergies (6%).

Learned intermediary

“Drug reps” have a responsibility to inform doctors of both benefits and risks of their medications, a process termed “fair balance.” Generally speaking, if a doctor fails to warn the patient of a medication risk, and injury results, the patient may have a claim against the doctor but not the drug manufacturer. This is termed the “learned intermediary” doctrine, which is also applicable to medical devices such as dialysis equipment, breast implants, and blood products.

The justification is that manufacturers can reasonably rely on the treating doctor to warn of adverse effects, which are disclosed to the profession through their sales reps and in the package insert and PDR. The treating doctor, in turn, is expected to use his or her professional judgment to adequately warn the patient. It is simply not feasible for the manufacturer to directly warn every patient without usurping the doctor-patient relationship. However, where known complications were undisclosed to the FDA and the profession, then plaintiff attorneys can file class action lawsuits directed at the manufacturer.

Complications

Complications arising out of the use of steroids are typical examples of medical products liability. This may be on the basis of the doctor having prescribed the medication without a proper indication or where contraindicated, or may have prescribed “the wrong dose for the wrong patient by the wrong route.” In addition, there may have been a lack of informed consent, i.e., failure to explain the underlying condition and the material risks associated with using the drug. Other acts of negligence, e.g., vicarious liability, may also apply.

Corticosteroids such as Prednisone, Decadron, Kenalog, etc., are widely prescribed, and can cause serious complications, especially when used in high doses for extended periods. Examples include suppression of the immune system with supervening infections, steroid osteoporosis and fractures,3 aseptic necrosis, steroid diabetes, hypertension, emotional changes, weight gain, cataracts, neurological complications, and many others. As in all malpractice actions, the plaintiff bears the burden of proof covering the four requisite tort elements, i.e., duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages. Expert testimony is almost always needed in a professional negligence lawsuit.

Aseptic necrosis is a feared complication of steroid therapy.

A recent report4 featured a nurse in her 40s who developed aseptic necrosis of the right shoulder and both hips after taking high dose prednisone for 6 months. She was being treated for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura by a hematologist as well as sarcoidosis by a pulmonologist. The plaintiff claimed that both defendants negligently prescribed the medication for an extended period of time without proper monitoring, which caused her severe bone complications requiring a hip and shoulder replacement. The defendants maintained that the steroid medication was necessary to treat the life-threatening conditions from which the plaintiff suffered and that the dosage was carefully monitored and was not excessive. However, in a jury trial, the defendant hematologist and pulmonologist were each found 50% negligent, and the patient was awarded $4.1 million in damages.

In a case5 of steroid-related neurological sequelae, a Colorado jury awarded $14.9 million to a couple against an outpatient surgery center for negligently administering an epidural dose of Kenalog that rendered the patient paraplegic, and for failure to obtain informed consent. The jury awarded the woman, age 57, approximately $1.7 million in past and future medical expenses; $3.2 million in unspecified economic damages; and $6.5 million in past and future noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering. Her husband will receive $3.5 million in past and future noneconomic damages for loss of consortium, according to the verdict. Two years before the injection date of 2013, the drug maker had announced that Kenalog should not be used for epidural procedures because of cord complications including infarction and paraplegia.

Contributory role

The putative offending drug does not have to be the sole cause of injury; if it played a contributory role, the court may find the presence of liability. For example, a Kansas appeals court6 upheld a jury award of $2.88 million in the case of a 40-year-old man who took his life after neurologic complications followed an epidural injection. During one of patient’s visits for chronic low back pain, the defendant-anesthesiologist administered an epidural steroid injection into an area left swollen from a previous injection.

The patient developed neurologic symptoms, and lumbar puncture yielded green pus caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. He went on to develop arachnoiditis, which left him with impotence, incontinence, and excruciating pain. His lawsuit contended the injection needle had passed through an infected edematous area, causing meningitis and arachnoiditis. Before the case went to trial, the patient took his life because of unremitting pain.

In March 2014, a Johnson County jury found the doctor 75% at fault and the clinic 25% at fault and awarded damages, which were reduced to $1.67 million because Kansas caps noneconomic damages at $250,000. The court rejected the defendants’ argument that the trial judge improperly instructed the jury it could find liability only if negligence “caused” rather than merely “contributed to” the patient’s death, holding that “... one who contributes to a wrongful death is a cause of that death as contemplated by the wrongful death statute.”

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu .

References

1. Hill v. Squibb Sons, E.R, 592 P.2d 1383 (Mont. 1979).

2. Nash JJ et al, Medical malpractice and corticosteroid use. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011; 144:10-5.

3. Buckley L. et al, Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:2547-56.

4. Zarin’s Jury Verdict: Review and Analysis. Article ID 40229, Philadelphia County.

5. Robbin Smith et al. v. The Surgery Center at Lone Tree, 2015-CV-30922, Douglas County District Court, Colo. Verdict for plaintiff, March 23, 2017.

6. Burnette v. Kimber L. Eubanks, M.D., & Paincare, P.A., 379 P.3d 372 (Kan. Ct. App. 2016).

More states pushing plans to pay for telehealth care

More states are enacting laws that require private plans to cover telehealth services, but fair payment remains a challenge for providers, a new analysis finds.

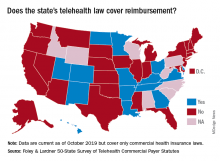

In 2019, 42 states and the District of Columbia had commercial payer telehealth laws, according to a December report by Foley & Lardner LLP, an international law firm. In contrast, about 30 states had such laws in 2015, according to a 2015 report by the National Conference of State Legislatures. Telehealth coverage laws generally require private plans to cover services provided via telehealth to the extent they cover in-person services of the same nature. The measures also frequently protect patients from cost-shifting, in which an insurer imposes higher deductibles or copays for telehealth services.

Private coverage for asynchronous telehealth and remote patient monitoring (RPM) is also growing. Twenty-four states mandate coverage for store and forward asynchronous telehealth, while 13 states require commercial health plans to cover RPM services, the analysis found. In addition, most telehealth coverage laws do not limit where a patient can receive telehealth services. However, some states, such as Arizona, Tennessee, and Washington, still require that patients be located in a particular clinical setting at the time of the telehealth consultation.

Overall, the landscape for reimbursement of telehealth services by commercial payers has improved, said Jacqueline Acosta, a health care attorney with Foley & Lardner and a coauthor of the report.

“[Foley& Lardner’s] 2017 report really noted that implementation [of telehealth] had really picked up both from providers and patients asking for telemedicine, but reimbursement still lagged behind,” Ms. Acosta said in an interview. “This one shows real progress on that front.”

However, the survey notes that payment parity for telehealth services remains lacking. Payment parity refers to insurers paying for telehealth services at the same or an equivalent rate as those delivered in-person. In 2019, 16 states had laws that specifically addressed reimbursement of telehealth services, but only 10 offer true payment parity, according to the Foley analysis. The 10 states with payment parity laws are Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, Utah, and Virginia. Other telehealth reimbursement measures often include ambiguity or allow room for payment negotiation, Ms. Acosta said.

She predicts that more payment parity laws and improved telehealth coverage laws are on the horizon for 2020 and beyond. California, for example, recently revised its telehealth law to require both coverage and payment parity for telehealth services. Mississippi meanwhile, recently expanded its law to include RPM coverage.

That states are revising existing laws and expanding their statutes shows an optimistic trend toward telehealth acceptance and coverage growth, Ms. Acosta said.

More states are enacting laws that require private plans to cover telehealth services, but fair payment remains a challenge for providers, a new analysis finds.