User login

Is it time for neurologists to manage high blood pressure?

In the Nov. 1, 2019, issue of JAMA Neurology, an editorial argues that it’s time for neurologists to start managing high blood pressure.

It makes some very valid points: that targeting a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg results in lower rates of cardiovascular events and all causes of mortality, that poorly controlled hypertension leads to debilitating neurologic conditions, and that high blood pressure is the most common modifiable risk factor for stroke.

All are strong points. I agree with them and definitely believe that more can and should be done to control hypertension.

The editorial then goes on to say that “first and foremost we are charging neurologists with actively diagnosing hypertension and prescribing medications when appropriate.”

Uh, no. I’m not going to be the one managing hypertension, nor should any outpatient neurologist.

Outpatient hypertension treatment has historically been, and should remain, the province of general practitioners, cardiologists, and nephrologists. Too many cooks, as they say, spoils the broth. I don’t want to be in a situation where two (or more) doctors are simultaneously trying to treat the same condition. On that path lies danger.

This doesn’t mean I ignore blood pressure. On the contrary, I take it (myself) at every patient visit, and put it in my note. In most cases I do nothing further, as nothing further needs to be done. On occasion, though, if it’s concerningly high, I’ll write it down for the patient and direct them to call the physician handling it. I also fax a note about it to that office, and if it’s dangerously high will call the doctor myself.

But try to manage it? No. Elevated readings definitely overlap with my world, but treating them shouldn’t.

The article says that, for some chronic patients, neurologists are their de facto internist. Perhaps for a few, but when a patient calls with concerns about a respiratory ailment, gastrointestinal problem, or other nonneurologic issue, I tell them to call their general practitioner. If they don’t have one I’m happy to give them the names and phone numbers of colleagues who practice that field, or even urgent care and emergency department information if needed. Just because I see them for their neurologic problems doesn’t qualify me to practice another branch of medicine.

Beyond the dangers of having more than one doctor involved, as a specialist it’s not practical for me to know the antihypertensive medications – possibly the largest group of agents on the market, – in detail, with their mechanisms of action, side effects, and contraindications. Yes, I do keep a handful in mind, since they’re needed off label for migraines and tremors, but not in the kind of detail a cardiologist would. I have to keep track of enough medications in my specialty as it is.

I wouldn’t try to handle blood pressure any more than I’d expect a nephrologist to treat epilepsy. It’s just looking for trouble.

Even when covering the hospital, I’ll stay out of that arena. This doesn’t mean I ignore blood pressure in such serious conditions as stroke or posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. I’m more than happy to provide guidelines and parameters. But as far as choosing the medications and doses? No.

Like driving, we all have to share the road. We may even be focused on the same journey (or patient). But part of practicing medicine and handling traffic is knowing when to stay in your lane.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the Nov. 1, 2019, issue of JAMA Neurology, an editorial argues that it’s time for neurologists to start managing high blood pressure.

It makes some very valid points: that targeting a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg results in lower rates of cardiovascular events and all causes of mortality, that poorly controlled hypertension leads to debilitating neurologic conditions, and that high blood pressure is the most common modifiable risk factor for stroke.

All are strong points. I agree with them and definitely believe that more can and should be done to control hypertension.

The editorial then goes on to say that “first and foremost we are charging neurologists with actively diagnosing hypertension and prescribing medications when appropriate.”

Uh, no. I’m not going to be the one managing hypertension, nor should any outpatient neurologist.

Outpatient hypertension treatment has historically been, and should remain, the province of general practitioners, cardiologists, and nephrologists. Too many cooks, as they say, spoils the broth. I don’t want to be in a situation where two (or more) doctors are simultaneously trying to treat the same condition. On that path lies danger.

This doesn’t mean I ignore blood pressure. On the contrary, I take it (myself) at every patient visit, and put it in my note. In most cases I do nothing further, as nothing further needs to be done. On occasion, though, if it’s concerningly high, I’ll write it down for the patient and direct them to call the physician handling it. I also fax a note about it to that office, and if it’s dangerously high will call the doctor myself.

But try to manage it? No. Elevated readings definitely overlap with my world, but treating them shouldn’t.

The article says that, for some chronic patients, neurologists are their de facto internist. Perhaps for a few, but when a patient calls with concerns about a respiratory ailment, gastrointestinal problem, or other nonneurologic issue, I tell them to call their general practitioner. If they don’t have one I’m happy to give them the names and phone numbers of colleagues who practice that field, or even urgent care and emergency department information if needed. Just because I see them for their neurologic problems doesn’t qualify me to practice another branch of medicine.

Beyond the dangers of having more than one doctor involved, as a specialist it’s not practical for me to know the antihypertensive medications – possibly the largest group of agents on the market, – in detail, with their mechanisms of action, side effects, and contraindications. Yes, I do keep a handful in mind, since they’re needed off label for migraines and tremors, but not in the kind of detail a cardiologist would. I have to keep track of enough medications in my specialty as it is.

I wouldn’t try to handle blood pressure any more than I’d expect a nephrologist to treat epilepsy. It’s just looking for trouble.

Even when covering the hospital, I’ll stay out of that arena. This doesn’t mean I ignore blood pressure in such serious conditions as stroke or posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. I’m more than happy to provide guidelines and parameters. But as far as choosing the medications and doses? No.

Like driving, we all have to share the road. We may even be focused on the same journey (or patient). But part of practicing medicine and handling traffic is knowing when to stay in your lane.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the Nov. 1, 2019, issue of JAMA Neurology, an editorial argues that it’s time for neurologists to start managing high blood pressure.

It makes some very valid points: that targeting a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg results in lower rates of cardiovascular events and all causes of mortality, that poorly controlled hypertension leads to debilitating neurologic conditions, and that high blood pressure is the most common modifiable risk factor for stroke.

All are strong points. I agree with them and definitely believe that more can and should be done to control hypertension.

The editorial then goes on to say that “first and foremost we are charging neurologists with actively diagnosing hypertension and prescribing medications when appropriate.”

Uh, no. I’m not going to be the one managing hypertension, nor should any outpatient neurologist.

Outpatient hypertension treatment has historically been, and should remain, the province of general practitioners, cardiologists, and nephrologists. Too many cooks, as they say, spoils the broth. I don’t want to be in a situation where two (or more) doctors are simultaneously trying to treat the same condition. On that path lies danger.

This doesn’t mean I ignore blood pressure. On the contrary, I take it (myself) at every patient visit, and put it in my note. In most cases I do nothing further, as nothing further needs to be done. On occasion, though, if it’s concerningly high, I’ll write it down for the patient and direct them to call the physician handling it. I also fax a note about it to that office, and if it’s dangerously high will call the doctor myself.

But try to manage it? No. Elevated readings definitely overlap with my world, but treating them shouldn’t.

The article says that, for some chronic patients, neurologists are their de facto internist. Perhaps for a few, but when a patient calls with concerns about a respiratory ailment, gastrointestinal problem, or other nonneurologic issue, I tell them to call their general practitioner. If they don’t have one I’m happy to give them the names and phone numbers of colleagues who practice that field, or even urgent care and emergency department information if needed. Just because I see them for their neurologic problems doesn’t qualify me to practice another branch of medicine.

Beyond the dangers of having more than one doctor involved, as a specialist it’s not practical for me to know the antihypertensive medications – possibly the largest group of agents on the market, – in detail, with their mechanisms of action, side effects, and contraindications. Yes, I do keep a handful in mind, since they’re needed off label for migraines and tremors, but not in the kind of detail a cardiologist would. I have to keep track of enough medications in my specialty as it is.

I wouldn’t try to handle blood pressure any more than I’d expect a nephrologist to treat epilepsy. It’s just looking for trouble.

Even when covering the hospital, I’ll stay out of that arena. This doesn’t mean I ignore blood pressure in such serious conditions as stroke or posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. I’m more than happy to provide guidelines and parameters. But as far as choosing the medications and doses? No.

Like driving, we all have to share the road. We may even be focused on the same journey (or patient). But part of practicing medicine and handling traffic is knowing when to stay in your lane.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Quantifying the EHR connection to burnout

While plenty of anecdotal and other evidence exists to connect the use of electronic health records to physician burnout, new research puts a more standard, quantifiable measure to it in an effort to help measure progress in improving the usability of EHRs.

Researchers used the System Usability Scale (SUS), “favored as an industry standard as a short, simple, and reliable measurement of technology usability with solid benchmarks to easily interpret its results, as the measure in this research, Edward Melnick, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

“The previous studies have definitely hinted at [the link between EHRs and burnout], but never really quantified it,” Dr. Melnick said in an interview.

Among the 870 physicians evaluating their EHRs’ usability, the mean score on a scale of 0-100 (higher being more usable) was 45.9. As a point of comparison, Microsoft Excel has an SUS score of 57, digital video recorders score 74, Amazon scores 82, microwave ovens score 87, and Google search scores 93.

“A score of 45.9 is in the bottom 9% of usability scores across studies in other industries and is categorized as in the ‘not acceptable’ range with a grade of F,” the authors wrote. “In aggregate, 733 of 870 (84.2%) of respondents rated their EHR less than 68 on the SUS, the average score across industries.”

In tying the SUS results to burnout, which was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the authors noted that the scores “were strongly and independently associated with physician burnout in a dose-response relationship. The odds of burnout were lower for each 1 point more favorable SUS score, a finding that persisted after adjusting for an extensive array of other personal and professional characteristics. The relationship between SUS score and burnout also persisted when emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were treated as continuous variables.”

The authors did note that, despite the strong relationship, they could not determine a causation given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

“I’m hoping that this paper will spark conversation and drive change and be a way of tracking improvements,” Dr. Melnick said. “So, if you bring in something new and say this is going to be better, how do you know it is going to be better? Well maybe you measure it using the System Usability Scale” to give it a quantifiable measure of improvement. He said it is an advantage “of having a metric that has been standardized and used in other industries,” allowing EHR stakeholders to measure improvement. “Once you can measure it, you can manage it and make improvements faster.”

The findings “will not come as a surprise to anyone who practices medicine,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement. “It is a national imperative to overhaul the design and use of EHRs and reframe the technology to focus primarily on its most critical function: helping physicians care for patients. Significantly enhancing EHR usability is key and the AMA is working to ensure a new generation of EHRs are designed to prioritize time with patients, rather than overload physicians with type-and-click tasks.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stanford Medicine WebMD Center, AMA, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being. No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

SOURCE: Melnick E et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019 Nov 14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.024.

While plenty of anecdotal and other evidence exists to connect the use of electronic health records to physician burnout, new research puts a more standard, quantifiable measure to it in an effort to help measure progress in improving the usability of EHRs.

Researchers used the System Usability Scale (SUS), “favored as an industry standard as a short, simple, and reliable measurement of technology usability with solid benchmarks to easily interpret its results, as the measure in this research, Edward Melnick, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

“The previous studies have definitely hinted at [the link between EHRs and burnout], but never really quantified it,” Dr. Melnick said in an interview.

Among the 870 physicians evaluating their EHRs’ usability, the mean score on a scale of 0-100 (higher being more usable) was 45.9. As a point of comparison, Microsoft Excel has an SUS score of 57, digital video recorders score 74, Amazon scores 82, microwave ovens score 87, and Google search scores 93.

“A score of 45.9 is in the bottom 9% of usability scores across studies in other industries and is categorized as in the ‘not acceptable’ range with a grade of F,” the authors wrote. “In aggregate, 733 of 870 (84.2%) of respondents rated their EHR less than 68 on the SUS, the average score across industries.”

In tying the SUS results to burnout, which was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the authors noted that the scores “were strongly and independently associated with physician burnout in a dose-response relationship. The odds of burnout were lower for each 1 point more favorable SUS score, a finding that persisted after adjusting for an extensive array of other personal and professional characteristics. The relationship between SUS score and burnout also persisted when emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were treated as continuous variables.”

The authors did note that, despite the strong relationship, they could not determine a causation given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

“I’m hoping that this paper will spark conversation and drive change and be a way of tracking improvements,” Dr. Melnick said. “So, if you bring in something new and say this is going to be better, how do you know it is going to be better? Well maybe you measure it using the System Usability Scale” to give it a quantifiable measure of improvement. He said it is an advantage “of having a metric that has been standardized and used in other industries,” allowing EHR stakeholders to measure improvement. “Once you can measure it, you can manage it and make improvements faster.”

The findings “will not come as a surprise to anyone who practices medicine,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement. “It is a national imperative to overhaul the design and use of EHRs and reframe the technology to focus primarily on its most critical function: helping physicians care for patients. Significantly enhancing EHR usability is key and the AMA is working to ensure a new generation of EHRs are designed to prioritize time with patients, rather than overload physicians with type-and-click tasks.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stanford Medicine WebMD Center, AMA, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being. No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

SOURCE: Melnick E et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019 Nov 14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.024.

While plenty of anecdotal and other evidence exists to connect the use of electronic health records to physician burnout, new research puts a more standard, quantifiable measure to it in an effort to help measure progress in improving the usability of EHRs.

Researchers used the System Usability Scale (SUS), “favored as an industry standard as a short, simple, and reliable measurement of technology usability with solid benchmarks to easily interpret its results, as the measure in this research, Edward Melnick, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

“The previous studies have definitely hinted at [the link between EHRs and burnout], but never really quantified it,” Dr. Melnick said in an interview.

Among the 870 physicians evaluating their EHRs’ usability, the mean score on a scale of 0-100 (higher being more usable) was 45.9. As a point of comparison, Microsoft Excel has an SUS score of 57, digital video recorders score 74, Amazon scores 82, microwave ovens score 87, and Google search scores 93.

“A score of 45.9 is in the bottom 9% of usability scores across studies in other industries and is categorized as in the ‘not acceptable’ range with a grade of F,” the authors wrote. “In aggregate, 733 of 870 (84.2%) of respondents rated their EHR less than 68 on the SUS, the average score across industries.”

In tying the SUS results to burnout, which was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the authors noted that the scores “were strongly and independently associated with physician burnout in a dose-response relationship. The odds of burnout were lower for each 1 point more favorable SUS score, a finding that persisted after adjusting for an extensive array of other personal and professional characteristics. The relationship between SUS score and burnout also persisted when emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were treated as continuous variables.”

The authors did note that, despite the strong relationship, they could not determine a causation given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

“I’m hoping that this paper will spark conversation and drive change and be a way of tracking improvements,” Dr. Melnick said. “So, if you bring in something new and say this is going to be better, how do you know it is going to be better? Well maybe you measure it using the System Usability Scale” to give it a quantifiable measure of improvement. He said it is an advantage “of having a metric that has been standardized and used in other industries,” allowing EHR stakeholders to measure improvement. “Once you can measure it, you can manage it and make improvements faster.”

The findings “will not come as a surprise to anyone who practices medicine,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement. “It is a national imperative to overhaul the design and use of EHRs and reframe the technology to focus primarily on its most critical function: helping physicians care for patients. Significantly enhancing EHR usability is key and the AMA is working to ensure a new generation of EHRs are designed to prioritize time with patients, rather than overload physicians with type-and-click tasks.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stanford Medicine WebMD Center, AMA, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being. No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

SOURCE: Melnick E et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019 Nov 14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.024.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

Ob.Gyn. News welcomes Dr. Angela Martin to the board

Dr. Martin is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, where she is the director of ultrasound training for the residency program. She also serves on the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee at the university.

Dr. Martin has been a primary author or coauthor of many articles published and accepted in refereed medical publications on topics including influenza infection during pregnancy, maternal and fetal risk associated with assisted reproductive technology, hepatitis B in pregnancy, umbilical cord blood banking, pregnancy and obesity, and cell-free fetal DNA. She currently is involved in research on resident operative delivery training, chorionic villus sampling, and preterm birth.

Graduating summa cum laude from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, with a bachelor of science degree in biology and a minor in psychology, Dr. Martin received her doctorate of medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia. She completed her postgraduate training at Emory University in Atlanta with an internship and residency in the department of gynecology and obstetrics, followed by a fellowship in the maternal-fetal medicine division.

Dr. Martin has won numerous honors and awards, including Outstanding Research Proposal by a fellow at Emory University, Excellence in Teaching awards for a fellow for several consecutive years at the university, and a National Faculty Award from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.*

*This article was updated 2/7/2020.

Dr. Martin is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, where she is the director of ultrasound training for the residency program. She also serves on the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee at the university.

Dr. Martin has been a primary author or coauthor of many articles published and accepted in refereed medical publications on topics including influenza infection during pregnancy, maternal and fetal risk associated with assisted reproductive technology, hepatitis B in pregnancy, umbilical cord blood banking, pregnancy and obesity, and cell-free fetal DNA. She currently is involved in research on resident operative delivery training, chorionic villus sampling, and preterm birth.

Graduating summa cum laude from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, with a bachelor of science degree in biology and a minor in psychology, Dr. Martin received her doctorate of medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia. She completed her postgraduate training at Emory University in Atlanta with an internship and residency in the department of gynecology and obstetrics, followed by a fellowship in the maternal-fetal medicine division.

Dr. Martin has won numerous honors and awards, including Outstanding Research Proposal by a fellow at Emory University, Excellence in Teaching awards for a fellow for several consecutive years at the university, and a National Faculty Award from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.*

*This article was updated 2/7/2020.

Dr. Martin is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, where she is the director of ultrasound training for the residency program. She also serves on the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee at the university.

Dr. Martin has been a primary author or coauthor of many articles published and accepted in refereed medical publications on topics including influenza infection during pregnancy, maternal and fetal risk associated with assisted reproductive technology, hepatitis B in pregnancy, umbilical cord blood banking, pregnancy and obesity, and cell-free fetal DNA. She currently is involved in research on resident operative delivery training, chorionic villus sampling, and preterm birth.

Graduating summa cum laude from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, with a bachelor of science degree in biology and a minor in psychology, Dr. Martin received her doctorate of medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia. She completed her postgraduate training at Emory University in Atlanta with an internship and residency in the department of gynecology and obstetrics, followed by a fellowship in the maternal-fetal medicine division.

Dr. Martin has won numerous honors and awards, including Outstanding Research Proposal by a fellow at Emory University, Excellence in Teaching awards for a fellow for several consecutive years at the university, and a National Faculty Award from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.*

*This article was updated 2/7/2020.

ASH to recognize researchers at annual meeting

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) plans to honor 10 researchers with awards and lectures at this year’s annual meeting, scheduled to take place Dec. 7-10 in Orlando.

Richard Aster, MD, will receive the 2019 Wallace H. Coulter Award for Lifetime Achievement in Hematology. Dr. Aster, of the Medical College of Wisconsin and Versiti Blood Center of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, “will be honored for his significant contributions to hematology through research, mentorship, and education throughout his 62-year career,” according to ASH.

Dr. Aster is known for his research on immune diseases that affect blood cells, particularly platelets. His work has led to improvements in platelet preparation, storage, and matching. In addition, he and his team developed the standard techniques for diagnosing immune thrombocytopenia and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia-thrombosis.

Other ASH awardees include William Eaton, MD, PhD, and Richard A. Larson, MD, who will receive the 2019 Henry M. Stratton Medal “for their seminal contributions to basic and clinical/translational hematology research, respectively.”

Dr. Eaton, of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases conducts research on sickle cell disease, and his work contributed to the development of hydroxyurea. Dr. Larson, of the University of Chicago is the namesake of the Larson regimen (CALGB 8811) for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and he played a key role in research that led to the U.S. approval of midostaurin.

Philip Greenberg, MD, will deliver the 2019 E. Donnall Thomas Lecture in recognition of “his outstanding contributions to the field of immunotherapy.” Dr. Greenberg, of theFred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington in Seattle, is known for contributing to the development of T-cell adoptive immune therapy. His lecture will focus on the engineering of T cells to target acute myeloid leukemia and other malignancies.

Sriram Krishnaswamy, PhD, and Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, will deliver the 2019 Ernest Beutler Lecture in recognition of “their significant research contributions to the understanding and treatment of blood clots.” The researchers will each deliver one part of the lecture at the meeting, and both will discuss research related to novel anticoagulants.

Dr. Krishnaswamy, of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is considered an authority on the function of surface-dependent coagulation complexes. Dr. Weitz, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., has conducted research that led to the development of novel anticoagulants.

Emmanuelle Passegué, PhD, will receive the 2019 William Dameshek Prize “for her outstanding contributions to the understanding of hematopoietic stem cells.” Dr. Passegué, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, conducts research focused on changes to hematopoietic stem cells in the contexts of myeloid malignancies and physiological aging.

Griffin Rodgers, MD, will receive the ASH Award for Leadership in Promoting Diversity “for his extraordinary commitment to diversity and inclusion in hematology.” As director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Dr. Rodgers has worked to promote diversity in the scientific workforce and in clinical trials.

Leonard Zon, MD, and Michael R. DeBaun, MD, will receive the 2019 ASH Mentor Award “for their sustained, outstanding commitment to the training and career development of early career hematologists.”

Dr. DeBaun, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., has mentees ranging from high school students with sickle cell disease to tenured faculty members at medical schools. Dr. Zon, of Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital, organizes mentoring events for postdocs, graduate students, and technicians.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) plans to honor 10 researchers with awards and lectures at this year’s annual meeting, scheduled to take place Dec. 7-10 in Orlando.

Richard Aster, MD, will receive the 2019 Wallace H. Coulter Award for Lifetime Achievement in Hematology. Dr. Aster, of the Medical College of Wisconsin and Versiti Blood Center of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, “will be honored for his significant contributions to hematology through research, mentorship, and education throughout his 62-year career,” according to ASH.

Dr. Aster is known for his research on immune diseases that affect blood cells, particularly platelets. His work has led to improvements in platelet preparation, storage, and matching. In addition, he and his team developed the standard techniques for diagnosing immune thrombocytopenia and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia-thrombosis.

Other ASH awardees include William Eaton, MD, PhD, and Richard A. Larson, MD, who will receive the 2019 Henry M. Stratton Medal “for their seminal contributions to basic and clinical/translational hematology research, respectively.”

Dr. Eaton, of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases conducts research on sickle cell disease, and his work contributed to the development of hydroxyurea. Dr. Larson, of the University of Chicago is the namesake of the Larson regimen (CALGB 8811) for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and he played a key role in research that led to the U.S. approval of midostaurin.

Philip Greenberg, MD, will deliver the 2019 E. Donnall Thomas Lecture in recognition of “his outstanding contributions to the field of immunotherapy.” Dr. Greenberg, of theFred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington in Seattle, is known for contributing to the development of T-cell adoptive immune therapy. His lecture will focus on the engineering of T cells to target acute myeloid leukemia and other malignancies.

Sriram Krishnaswamy, PhD, and Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, will deliver the 2019 Ernest Beutler Lecture in recognition of “their significant research contributions to the understanding and treatment of blood clots.” The researchers will each deliver one part of the lecture at the meeting, and both will discuss research related to novel anticoagulants.

Dr. Krishnaswamy, of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is considered an authority on the function of surface-dependent coagulation complexes. Dr. Weitz, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., has conducted research that led to the development of novel anticoagulants.

Emmanuelle Passegué, PhD, will receive the 2019 William Dameshek Prize “for her outstanding contributions to the understanding of hematopoietic stem cells.” Dr. Passegué, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, conducts research focused on changes to hematopoietic stem cells in the contexts of myeloid malignancies and physiological aging.

Griffin Rodgers, MD, will receive the ASH Award for Leadership in Promoting Diversity “for his extraordinary commitment to diversity and inclusion in hematology.” As director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Dr. Rodgers has worked to promote diversity in the scientific workforce and in clinical trials.

Leonard Zon, MD, and Michael R. DeBaun, MD, will receive the 2019 ASH Mentor Award “for their sustained, outstanding commitment to the training and career development of early career hematologists.”

Dr. DeBaun, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., has mentees ranging from high school students with sickle cell disease to tenured faculty members at medical schools. Dr. Zon, of Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital, organizes mentoring events for postdocs, graduate students, and technicians.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) plans to honor 10 researchers with awards and lectures at this year’s annual meeting, scheduled to take place Dec. 7-10 in Orlando.

Richard Aster, MD, will receive the 2019 Wallace H. Coulter Award for Lifetime Achievement in Hematology. Dr. Aster, of the Medical College of Wisconsin and Versiti Blood Center of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, “will be honored for his significant contributions to hematology through research, mentorship, and education throughout his 62-year career,” according to ASH.

Dr. Aster is known for his research on immune diseases that affect blood cells, particularly platelets. His work has led to improvements in platelet preparation, storage, and matching. In addition, he and his team developed the standard techniques for diagnosing immune thrombocytopenia and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia-thrombosis.

Other ASH awardees include William Eaton, MD, PhD, and Richard A. Larson, MD, who will receive the 2019 Henry M. Stratton Medal “for their seminal contributions to basic and clinical/translational hematology research, respectively.”

Dr. Eaton, of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases conducts research on sickle cell disease, and his work contributed to the development of hydroxyurea. Dr. Larson, of the University of Chicago is the namesake of the Larson regimen (CALGB 8811) for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and he played a key role in research that led to the U.S. approval of midostaurin.

Philip Greenberg, MD, will deliver the 2019 E. Donnall Thomas Lecture in recognition of “his outstanding contributions to the field of immunotherapy.” Dr. Greenberg, of theFred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington in Seattle, is known for contributing to the development of T-cell adoptive immune therapy. His lecture will focus on the engineering of T cells to target acute myeloid leukemia and other malignancies.

Sriram Krishnaswamy, PhD, and Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, will deliver the 2019 Ernest Beutler Lecture in recognition of “their significant research contributions to the understanding and treatment of blood clots.” The researchers will each deliver one part of the lecture at the meeting, and both will discuss research related to novel anticoagulants.

Dr. Krishnaswamy, of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is considered an authority on the function of surface-dependent coagulation complexes. Dr. Weitz, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., has conducted research that led to the development of novel anticoagulants.

Emmanuelle Passegué, PhD, will receive the 2019 William Dameshek Prize “for her outstanding contributions to the understanding of hematopoietic stem cells.” Dr. Passegué, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, conducts research focused on changes to hematopoietic stem cells in the contexts of myeloid malignancies and physiological aging.

Griffin Rodgers, MD, will receive the ASH Award for Leadership in Promoting Diversity “for his extraordinary commitment to diversity and inclusion in hematology.” As director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Dr. Rodgers has worked to promote diversity in the scientific workforce and in clinical trials.

Leonard Zon, MD, and Michael R. DeBaun, MD, will receive the 2019 ASH Mentor Award “for their sustained, outstanding commitment to the training and career development of early career hematologists.”

Dr. DeBaun, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., has mentees ranging from high school students with sickle cell disease to tenured faculty members at medical schools. Dr. Zon, of Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital, organizes mentoring events for postdocs, graduate students, and technicians.

Black-box warnings: How they can improve your clinical practice

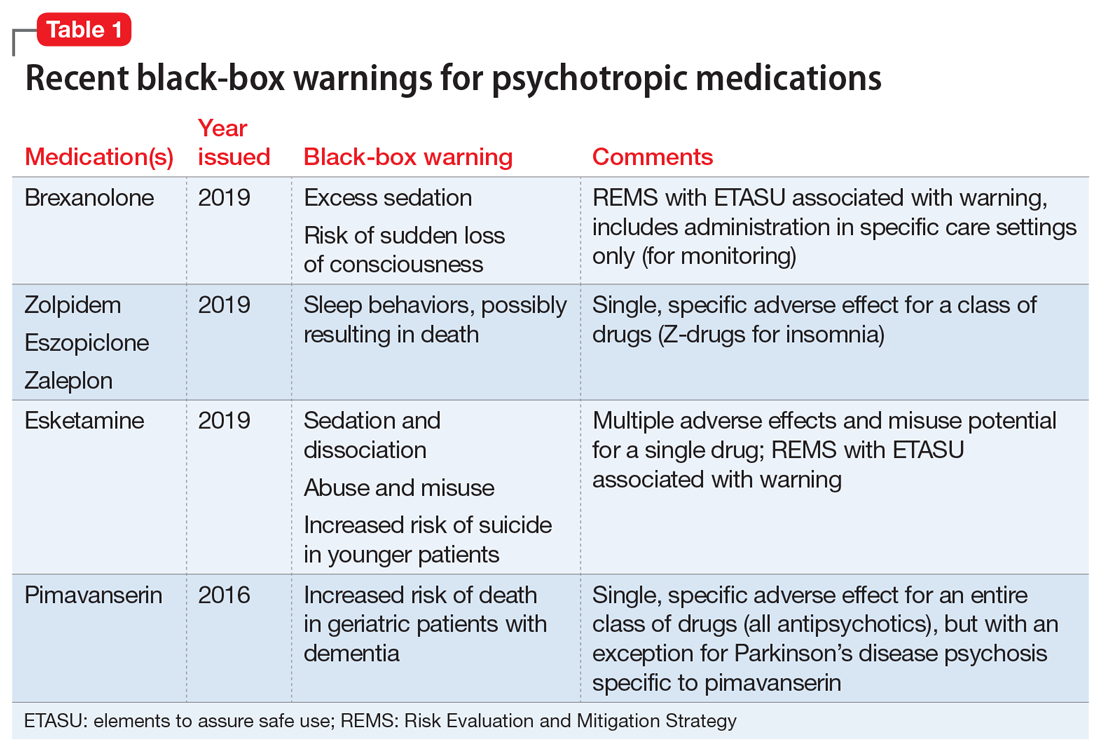

Recently, the FDA issued “black-box” warnings, its most prominent drug safety statements, for esketamine,1 which is indicated for treatment-resistant depression, and the Z-drugs, which are indicated for insomnia2 (Table 1). A black-box warning also comes with brexanolone, which was recently approved for postpartum depression.3 While these newly issued warnings serve as a timely reminder of the importance of black-box warnings, older black-box warnings also cover large areas of psychiatric prescribing, including all medications indicated for treating psychosis or schizophrenia (increased mortality in patients with dementia), and all psychotropic medications with a depression indication (suicidality in younger people).

In this article, we help busy prescribers navigate the landscape of black-box warnings by providing a concise review of how to use them in clinical practice, and where to find information to keep up-to-date.

What are black-box warnings?

A black-box warning is a summary of the potential serious or life-threatening risks of a specific prescription medication. The black-box warning is formatted within a black border found at the top of the manufacturer’s prescribing information document (also known as the package insert or product label). Below the black-box warning, potential risks appear in descending order in sections titled “Contraindications,” “Warnings and Precautions,” and “Adverse Reactions.”4 The FDA issues black-box warnings either during drug development, to take effect upon approval of a new agent, or (more commonly) based on post-marketing safety information,5 which the FDA continuously gathers from reports by patients, clinicians, and industry.6 Federal law mandates the existence of black-box warnings, stating in part that, “special problems, particularly those that may lead to death or serious injury, may be required by the [FDA] to be placed in a prominently displayed box” (21 CFR 201.57(e)).

When is a black-box warning necessary?

The FDA issues a black-box warning based upon its judgment of the seriousness of the adverse effect. However, by definition, these risks do not inherently outweigh the benefits a medication may offer to certain patients. According to the FDA,7 black-box warnings are placed when:

- an adverse reaction so significant exists that this potential negative effect must be considered in risks and benefits when prescribing the medication

- a serious adverse reaction exists that can be prevented, or the risk reduced, by appropriate use of the medication

- the FDA has approved the medication with restrictions to ensure safe use.

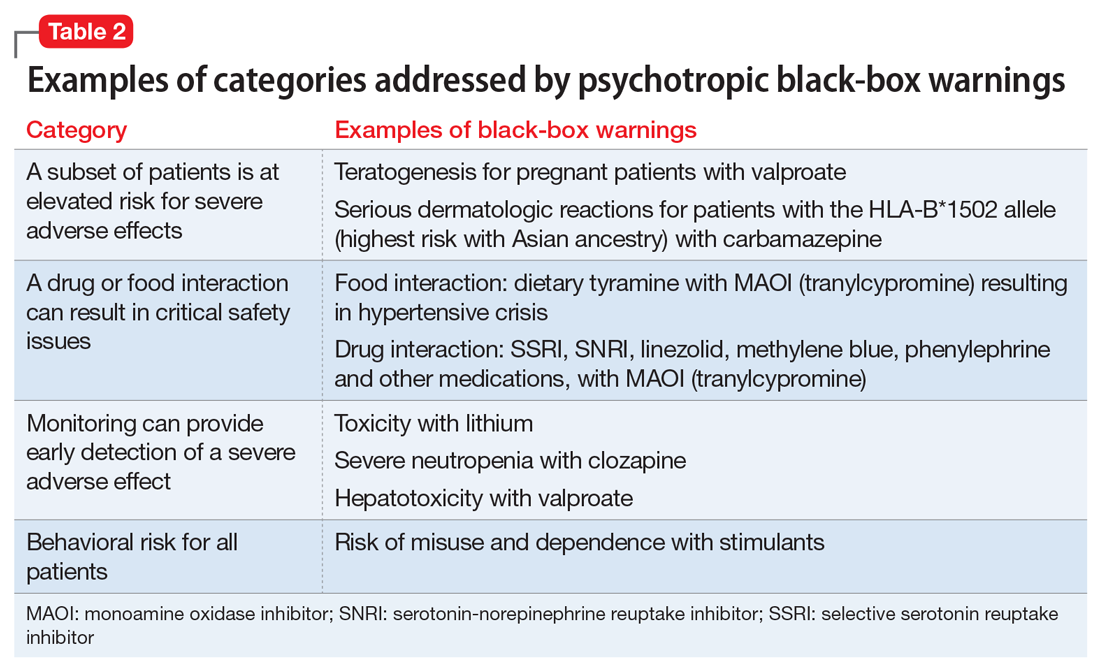

Table 2 shows examples of scenarios where black-box warnings have been issued.8 Black-box warnings may be placed on an individual agent or on an entire class of medications. For example, both antipsychotics and antidepressants have class-wide warnings. Finally, black-box warnings are not static, and their content may change; in a study of black-box warnings issued from 2007 to 2015, 29% were entirely new, 32% were considered major updates to existing black-box warnings, and 40% were minor updates.5

Critiques of black-box warnings focus on the absence of published, formal criteria for instituting such warnings, the lack of a consistent approach in their content, and the infrequent inclusion of any information on the relative size of the risk.9 Suggestions for improvement include offering guidance on how to implement the black-box warnings in a patient-centered, shared decision-making model by adding evidence profiles and implementation guides.10 Less frequently considered, black-box warnings may be discontinued if new evidence demonstrates that the risk is lower than previously appreciated; however, similarly to their placement, no explicit criteria for the removal of black-box warnings have been made public.11

When a medication poses an especially high safety risk, the FDA may require the manufacturer to implement a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. These programs can describe specific steps to improve medication safety, known as elements to assure safe use (ETASU).4 A familiar example is the clozapine REMS. In order to reduce the risk of severe neutropenia, the clozapine REMS requires prescribers (and pharmacists) to complete specialized training (making up the ETASU). Surprisingly, not every medication with a REMS has a corresponding black-box warning12; more understandably, many medications with black-box warnings do not have an associated REMS, because their risks are evaluated to be manageable by an individual prescriber’s clinical judgment. Most recently, esketamine carries both a black-box warning and a REMS. The black-box warning focuses on adverse effects (Table 1), while the REMS focuses on specific steps used to lessen these risks, including requiring use of a patient enrollment and monitoring form, a fact sheet for patients, and health care setting and pharmacy enrollment forms.13

Continue to: Psychotropic medications and black-box warnings

Psychotropic medications and black-box warnings

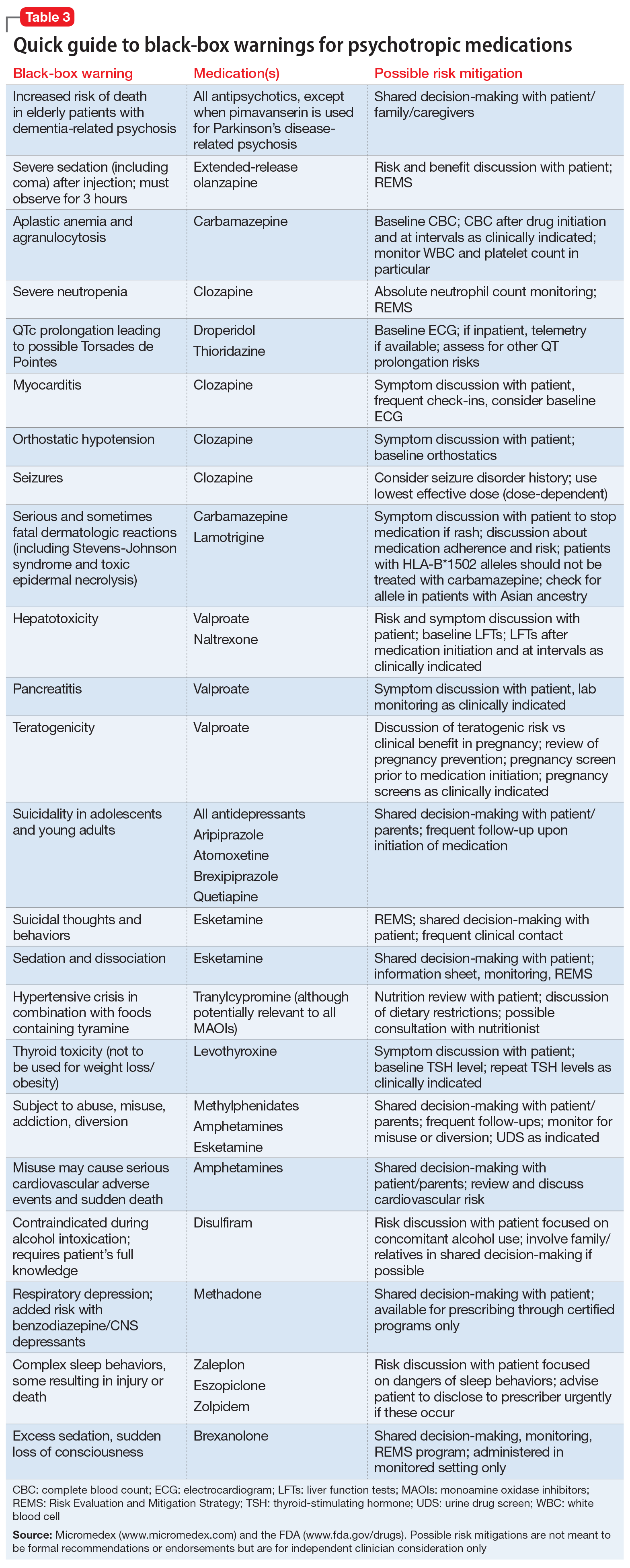

Psychotropic medications have a large number of black-box warnings.14 Because it is difficult to find black-box warnings for multiple medications in one place, we have provided 2 convenient resources to address this gap: a concise summary guide (Table 3) and a more detailed database (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, and Table 8). In these Tables, the possible risk mitigations, off-label uses, and monitoring are not meant to be formal recommendations or endorsements but are for independent clinician consideration only.

The information in these Tables was drawn from publicly available data, primarily the Micromedex and FDA web sites (see Related Resources). Because this information changes over time, at the end of this article we suggest ways for clinicians to stay updated with black-box warnings and build on the information provided in this article. These tools can be useful for day-to-day clinical practice in addition to studying for professional examinations. The following are selected high-profile black-box warnings.

Antidepressants and suicide risk. As a class, antidepressants carry a black-box warning on suicide risk in patients age ≤24. Initially issued in 2005, this warning was extended in 2007 to indicate that depression itself is associated with an increased risk of suicide. This black-box warning is used for an entire class of medications as well as for a specific patient population (age ≤24). Moreover, it indicates that suicide rates in patients age >65 were lower among patients using antidepressants.

Among psychotropic medication black-box warnings, this warning has perhaps been the most controversial. For example, it has been suggested that this black-box warning may have inadvertently increased suicide rates by discouraging clinicians from prescribing antidepressants,15 although this also has been called into question.16 This black-box warning illustrates that the consequences of issuing black-box warnings can be very difficult to assess, which makes their clinical effects highly complex and challenging to evaluate.14

Antipsychotics and dementia-related psychosis. This warning was initially issued in 2005 for second-generation antipsychotics and extended to first-generation antipsychotics in 2008. Antipsychotics as a class carry a black-box warning for increased risk of death in patients with dementia (major neurocognitive disorder). This warning extends to the recently approved antipsychotic pimavanserin, even though this agent’s proposed mechanism of action differs from that of other antipsychotics.17 However, it specifically allows for use in Parkinson’s disease psychosis, which is pimavanserin’s indication.18 In light of recent research suggesting pimavanserin is effective in dementia-related psychosis,19 it bears watching whether this agent becomes the first antipsychotic to have this warning removed.

Continue to: This class warning has...

This class warning has had widespread effects. For example, it has prompted less use of antipsychotics in nursing home facilities, as a result of stricter Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services regulations20; overall, there is some evidence that there has been reduced prescribing of antipsychotics in general.21 Additionally, this black-box warning is unusual in that it warns about a specific off-label indication, which is itself poorly supported by evidence.21 Concomitantly, few other treatment options are available for this clinical situation. These medications are often seen as the only option for patients with dementia complicated by severe behavioral disturbance, and thus this black-box warning reflects real-world practices.14

Varenicline and neuropsychiatric complications. The withdrawal of the black-box warning on potential neuropsychiatric complications of using varenicline for smoking cessation shows that black-box warnings are not static and can, though infrequently, be removed as more safety data accumulates.11 As additional post-marketing information emerged on this risk, this black-box warning was reconsidered and withdrawn in 2016.22 Its withdrawal could potentially make clinicians more comfortable prescribing varenicline and in turn, help to reduce smoking rates.

How to use black-box warnings

To enhance their clinical practice, prescribers can use black-box warnings to inform safe prescribing practices, to guide shared decision-making, and to improve documentation of their treatment decisions.

Informing safe prescribing practices. A prescriber should be aware of the main safety concerns contained in a medication’s black-box warning; at the same time, these warnings are not meant to unduly limit use when crucial treatment is needed.14 In issuing a black-box warning, the FDA has clearly stated the priority and seriousness of its concern. These safety issues must be balanced against the medication’s utility for a given patient, at the prescriber’s clinical judgment.

Guiding shared decision-making. Clinicians are not required to disclose black-box warnings to patients, and there are no criteria that clearly define the role of these warnings in patient care. As is often noted, the FDA does not regulate the practice of medicine.6 However, given the seriousness of the potential adverse effects delineated by black-box warnings, it is reasonable for clinicians to have a solid grasp of black-box warnings for all medications they prescribe, and to be able to relate these warnings to patients, in appropriate language. This patient-centered discussion should include weighing the risks and benefits with the patient and educating the patient about the risks and strategies to mitigate those risks. This discussion can be augmented by patient handouts, which are often offered by pharmaceutical manufacturers, and by shared decision-making tools. A proactive discussion with patients and families about black-box warnings and other risks discussed in product labels can help reduce fears associated with taking medications and may improve adherence.

Continue to: Improving documentation of treatment decisions

Improving documentation of treatment decisions. Fluent knowledge of black-box warnings may help clinicians improve documentation of their treatment decisions, particularly the risks and benefits of their medication choices. Fluency with black-box warnings will help clinicians accurately document both their awareness of these risks, and how these risks informed their risk-benefit analysis in specific clinical situations.

Despite the clear importance the FDA places on black-box warnings, they are not often a topic of study in training or in postgraduate continuing education, and as a result, not all clinicians may be equally conversant with black-box warnings. While black-box warnings do change over time, many psychotropic medication black-box warnings are long-standing and well-established, and they evolve slowly enough to make mastering these warnings worthwhile in order to make the most informed clinical decisions for patient care.

Keeping up-to-date

There are practical and useful ways for busy clinicians to stay up-to-date with black-box warnings. Although these resources exist in multiple locations, together they provide convenient ways to keep current.

The FDA provides access to black-box warnings via its comprehensive database, DRUGS@FDA (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/). Detailed information about REMS (and corresponding ETASU and other information related to REMS programs) is available at REMS@FDA (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm). Clinicians can make safety reports that may contribute to FDA decision-making on black-box warnings by contacting MedWatch (https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-information-and-adverse-event-reporting-program), the FDA’s adverse events reporting system. MedWatch releases safety information reports, which can be followed on Twitter @FDAMedWatch. Note that FDA information generally is organized by specific drug, and not into categories, such as psychotropic medications.

BlackBoxRx (www.blackboxrx.com) is a subscription-based web service that some clinicians may have access to via facility or academic resources as part of a larger FormWeb software package. Individuals also can subscribe (currently, $89/year).

Continue to: Micromedex

Micromedex (www.micromedex.com), which is widely available through medical libraries, is a subscription-based web service that provides black-box warning information from a separate tab that is easily accessed in each drug’s information front page. There is also an alphabetical list of black-box warnings under a separate tab on the Micromedex landing page.

ePocrates (www.epocrates.com) is a subscription-based service that provides extensive drug information, including black-box warnings, in a convenient mobile app.

Bottom Line

Black-box warnings are the most prominent drug safety warnings issued by the FDA. Many psychotropic medications carry black-box warnings that are crucial to everyday psychiatric prescribing. A better understanding of blackbox warnings can enhance your clinical practice by informing safe prescribing practices, guiding shared decision-making, and improving documentation of your treatment decisions.

Related Resources

- US Food and Drug Administration. DRUGS@FDA: FDAapproved drug products. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Drug safety and availability. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability. Updated October 10, 2019.

- BlackBoxRx. www.blackboxrx.com. (Subscription required.)

- Mircromedex. www.micromedex.com. (Subscription required.)

- ePocrates. www.epocrates.com. (Subscription required.)

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Vanatrip

Amoxatine • Strattera

Amoxapine • Asendin

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Brexpiprazole • Rexulti

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Cariprazine • Vraylar

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Doxepin • Prudoxin, Silenor

Droperidol • Inapsine

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Esketamine • Spravato

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Haloperidol • Haldol

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Imipramine • Tofranil

Isocarboxazid • Marplan

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Linezolid • Zyvox

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Loxitane

Lurasidone • Latuda

Maprotiline • Ludiomil

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

Midazolam • Versed

Milnacipran • Savella

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • Revia, Vivitrol

Nefazodone • Serzone

Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paroxetine • Paxil

Perphenazine • Trilafon

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Prochlorperazine • Compro

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Selegiline • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

Trimipramine • Surmontil

Valproate • Depakote

Varenicline • Chantix, Wellbutrin

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Spravato [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies; 2019.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety announcement: FDA adds boxed warning for risk of serious injuries caused by sleepwalking with certain prescription insomnia medicines. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-adds-boxed-warning-risk-serious-injuries-caused-sleepwalking-certain-prescription-insomnia. Published April 30, 2019. Accessed October 28, 2019.

3. Zulresso [package insert]. Cambridge, Mass.: Sage Therapeutics Inc.; 2019.

4. Gassman AL, Nguyen CP, Joffe HV. FDA regulation of prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):674-682.

5. Solotke MT, Dhruva SS, Downing NS, et al. New and incremental FDA black box warnings from 2008 to 2015. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(2):117-123.

6. Murphy S, Roberts R. “Black box” 101: how the Food and Drug Administration evaluates, communicates, and manages drug benefit/risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(1):34-39.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance document: Warnings and precautions, contraindications, and boxed warning sections of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products – content and format. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/warnings-and-precautions-contraindications-and-boxed-warning-sections-labeling-human-prescription. Published October 2011. Accessed October 28, 2019.

8. Beach JE, Faich GA, Bormel FG, et al. Black box warnings in prescription drug labeling: results of a survey of 206 drugs. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53(3):403-411.

9. Matlock A, Allan N, Wills B, et al. A continuing black hole? The FDA boxed warning: an appeal to improve its clinical utility. Clinical Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(6):443-447.

10. Elraiyah T, Gionfriddo MR, Montori VM, et al. Content, consistency, and quality of black box warnings: time for a change. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):875-876.

11. Yeh JS, Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Ethical and practical considerations in removing black box warnings from drug labels. Drug Saf. 2016;39(8):709-714.

12. Boudes PF. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMSs): are they improving drug safety? A critical review of REMSs requiring Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU). Drugs R D. 2017;17(2):245-254.

13. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved risk evaluation mitigation strategies (REMS): Spravato (esketamine) REMS program. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=386. Updated June 25, 2019. Accessed October 28, 2018.

14. Stevens JR, Jarrahzadeh T, Brendel RW, et al. Strategies for the prescription of psychotropic drugs with black box warnings. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):123-133.

15. Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning--10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666-1668.

16. Stone MB. The FDA warning on antidepressants and suicidality--why the controversy? N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1668-1671.

17. Mathis MV, Muoio BM, Andreason P, et al. The US Food and Drug Administration’s perspective on the new antipsychotic pimavanserin. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(6):e668-e673. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16r11119.

18. Nuplazid [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc.; May 2019.

19. Ballard C, Banister C, Khan Z, et al. Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(3):213-222.

20. Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, et al. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care with the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropics in long-term care in the United States from 2009 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):640-647.

21. Dorsey ER, Rabbani A, Gallagher SA, et al. Impact of FDA black box advisory on antipsychotic medication use. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):96-103.

22. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-revises-description-mental-health-side-effects-stop-smoking. Published December 16, 2016. Accessed October 28, 2019.

Recently, the FDA issued “black-box” warnings, its most prominent drug safety statements, for esketamine,1 which is indicated for treatment-resistant depression, and the Z-drugs, which are indicated for insomnia2 (Table 1). A black-box warning also comes with brexanolone, which was recently approved for postpartum depression.3 While these newly issued warnings serve as a timely reminder of the importance of black-box warnings, older black-box warnings also cover large areas of psychiatric prescribing, including all medications indicated for treating psychosis or schizophrenia (increased mortality in patients with dementia), and all psychotropic medications with a depression indication (suicidality in younger people).

In this article, we help busy prescribers navigate the landscape of black-box warnings by providing a concise review of how to use them in clinical practice, and where to find information to keep up-to-date.

What are black-box warnings?

A black-box warning is a summary of the potential serious or life-threatening risks of a specific prescription medication. The black-box warning is formatted within a black border found at the top of the manufacturer’s prescribing information document (also known as the package insert or product label). Below the black-box warning, potential risks appear in descending order in sections titled “Contraindications,” “Warnings and Precautions,” and “Adverse Reactions.”4 The FDA issues black-box warnings either during drug development, to take effect upon approval of a new agent, or (more commonly) based on post-marketing safety information,5 which the FDA continuously gathers from reports by patients, clinicians, and industry.6 Federal law mandates the existence of black-box warnings, stating in part that, “special problems, particularly those that may lead to death or serious injury, may be required by the [FDA] to be placed in a prominently displayed box” (21 CFR 201.57(e)).

When is a black-box warning necessary?

The FDA issues a black-box warning based upon its judgment of the seriousness of the adverse effect. However, by definition, these risks do not inherently outweigh the benefits a medication may offer to certain patients. According to the FDA,7 black-box warnings are placed when:

- an adverse reaction so significant exists that this potential negative effect must be considered in risks and benefits when prescribing the medication

- a serious adverse reaction exists that can be prevented, or the risk reduced, by appropriate use of the medication

- the FDA has approved the medication with restrictions to ensure safe use.

Table 2 shows examples of scenarios where black-box warnings have been issued.8 Black-box warnings may be placed on an individual agent or on an entire class of medications. For example, both antipsychotics and antidepressants have class-wide warnings. Finally, black-box warnings are not static, and their content may change; in a study of black-box warnings issued from 2007 to 2015, 29% were entirely new, 32% were considered major updates to existing black-box warnings, and 40% were minor updates.5

Critiques of black-box warnings focus on the absence of published, formal criteria for instituting such warnings, the lack of a consistent approach in their content, and the infrequent inclusion of any information on the relative size of the risk.9 Suggestions for improvement include offering guidance on how to implement the black-box warnings in a patient-centered, shared decision-making model by adding evidence profiles and implementation guides.10 Less frequently considered, black-box warnings may be discontinued if new evidence demonstrates that the risk is lower than previously appreciated; however, similarly to their placement, no explicit criteria for the removal of black-box warnings have been made public.11

When a medication poses an especially high safety risk, the FDA may require the manufacturer to implement a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. These programs can describe specific steps to improve medication safety, known as elements to assure safe use (ETASU).4 A familiar example is the clozapine REMS. In order to reduce the risk of severe neutropenia, the clozapine REMS requires prescribers (and pharmacists) to complete specialized training (making up the ETASU). Surprisingly, not every medication with a REMS has a corresponding black-box warning12; more understandably, many medications with black-box warnings do not have an associated REMS, because their risks are evaluated to be manageable by an individual prescriber’s clinical judgment. Most recently, esketamine carries both a black-box warning and a REMS. The black-box warning focuses on adverse effects (Table 1), while the REMS focuses on specific steps used to lessen these risks, including requiring use of a patient enrollment and monitoring form, a fact sheet for patients, and health care setting and pharmacy enrollment forms.13

Continue to: Psychotropic medications and black-box warnings

Psychotropic medications and black-box warnings

Psychotropic medications have a large number of black-box warnings.14 Because it is difficult to find black-box warnings for multiple medications in one place, we have provided 2 convenient resources to address this gap: a concise summary guide (Table 3) and a more detailed database (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, and Table 8). In these Tables, the possible risk mitigations, off-label uses, and monitoring are not meant to be formal recommendations or endorsements but are for independent clinician consideration only.

The information in these Tables was drawn from publicly available data, primarily the Micromedex and FDA web sites (see Related Resources). Because this information changes over time, at the end of this article we suggest ways for clinicians to stay updated with black-box warnings and build on the information provided in this article. These tools can be useful for day-to-day clinical practice in addition to studying for professional examinations. The following are selected high-profile black-box warnings.

Antidepressants and suicide risk. As a class, antidepressants carry a black-box warning on suicide risk in patients age ≤24. Initially issued in 2005, this warning was extended in 2007 to indicate that depression itself is associated with an increased risk of suicide. This black-box warning is used for an entire class of medications as well as for a specific patient population (age ≤24). Moreover, it indicates that suicide rates in patients age >65 were lower among patients using antidepressants.

Among psychotropic medication black-box warnings, this warning has perhaps been the most controversial. For example, it has been suggested that this black-box warning may have inadvertently increased suicide rates by discouraging clinicians from prescribing antidepressants,15 although this also has been called into question.16 This black-box warning illustrates that the consequences of issuing black-box warnings can be very difficult to assess, which makes their clinical effects highly complex and challenging to evaluate.14

Antipsychotics and dementia-related psychosis. This warning was initially issued in 2005 for second-generation antipsychotics and extended to first-generation antipsychotics in 2008. Antipsychotics as a class carry a black-box warning for increased risk of death in patients with dementia (major neurocognitive disorder). This warning extends to the recently approved antipsychotic pimavanserin, even though this agent’s proposed mechanism of action differs from that of other antipsychotics.17 However, it specifically allows for use in Parkinson’s disease psychosis, which is pimavanserin’s indication.18 In light of recent research suggesting pimavanserin is effective in dementia-related psychosis,19 it bears watching whether this agent becomes the first antipsychotic to have this warning removed.

Continue to: This class warning has...

This class warning has had widespread effects. For example, it has prompted less use of antipsychotics in nursing home facilities, as a result of stricter Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services regulations20; overall, there is some evidence that there has been reduced prescribing of antipsychotics in general.21 Additionally, this black-box warning is unusual in that it warns about a specific off-label indication, which is itself poorly supported by evidence.21 Concomitantly, few other treatment options are available for this clinical situation. These medications are often seen as the only option for patients with dementia complicated by severe behavioral disturbance, and thus this black-box warning reflects real-world practices.14

Varenicline and neuropsychiatric complications. The withdrawal of the black-box warning on potential neuropsychiatric complications of using varenicline for smoking cessation shows that black-box warnings are not static and can, though infrequently, be removed as more safety data accumulates.11 As additional post-marketing information emerged on this risk, this black-box warning was reconsidered and withdrawn in 2016.22 Its withdrawal could potentially make clinicians more comfortable prescribing varenicline and in turn, help to reduce smoking rates.

How to use black-box warnings

To enhance their clinical practice, prescribers can use black-box warnings to inform safe prescribing practices, to guide shared decision-making, and to improve documentation of their treatment decisions.

Informing safe prescribing practices. A prescriber should be aware of the main safety concerns contained in a medication’s black-box warning; at the same time, these warnings are not meant to unduly limit use when crucial treatment is needed.14 In issuing a black-box warning, the FDA has clearly stated the priority and seriousness of its concern. These safety issues must be balanced against the medication’s utility for a given patient, at the prescriber’s clinical judgment.

Guiding shared decision-making. Clinicians are not required to disclose black-box warnings to patients, and there are no criteria that clearly define the role of these warnings in patient care. As is often noted, the FDA does not regulate the practice of medicine.6 However, given the seriousness of the potential adverse effects delineated by black-box warnings, it is reasonable for clinicians to have a solid grasp of black-box warnings for all medications they prescribe, and to be able to relate these warnings to patients, in appropriate language. This patient-centered discussion should include weighing the risks and benefits with the patient and educating the patient about the risks and strategies to mitigate those risks. This discussion can be augmented by patient handouts, which are often offered by pharmaceutical manufacturers, and by shared decision-making tools. A proactive discussion with patients and families about black-box warnings and other risks discussed in product labels can help reduce fears associated with taking medications and may improve adherence.

Continue to: Improving documentation of treatment decisions

Improving documentation of treatment decisions. Fluent knowledge of black-box warnings may help clinicians improve documentation of their treatment decisions, particularly the risks and benefits of their medication choices. Fluency with black-box warnings will help clinicians accurately document both their awareness of these risks, and how these risks informed their risk-benefit analysis in specific clinical situations.

Despite the clear importance the FDA places on black-box warnings, they are not often a topic of study in training or in postgraduate continuing education, and as a result, not all clinicians may be equally conversant with black-box warnings. While black-box warnings do change over time, many psychotropic medication black-box warnings are long-standing and well-established, and they evolve slowly enough to make mastering these warnings worthwhile in order to make the most informed clinical decisions for patient care.

Keeping up-to-date

There are practical and useful ways for busy clinicians to stay up-to-date with black-box warnings. Although these resources exist in multiple locations, together they provide convenient ways to keep current.

The FDA provides access to black-box warnings via its comprehensive database, DRUGS@FDA (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/). Detailed information about REMS (and corresponding ETASU and other information related to REMS programs) is available at REMS@FDA (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm). Clinicians can make safety reports that may contribute to FDA decision-making on black-box warnings by contacting MedWatch (https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-information-and-adverse-event-reporting-program), the FDA’s adverse events reporting system. MedWatch releases safety information reports, which can be followed on Twitter @FDAMedWatch. Note that FDA information generally is organized by specific drug, and not into categories, such as psychotropic medications.

BlackBoxRx (www.blackboxrx.com) is a subscription-based web service that some clinicians may have access to via facility or academic resources as part of a larger FormWeb software package. Individuals also can subscribe (currently, $89/year).

Continue to: Micromedex

Micromedex (www.micromedex.com), which is widely available through medical libraries, is a subscription-based web service that provides black-box warning information from a separate tab that is easily accessed in each drug’s information front page. There is also an alphabetical list of black-box warnings under a separate tab on the Micromedex landing page.

ePocrates (www.epocrates.com) is a subscription-based service that provides extensive drug information, including black-box warnings, in a convenient mobile app.

Bottom Line

Black-box warnings are the most prominent drug safety warnings issued by the FDA. Many psychotropic medications carry black-box warnings that are crucial to everyday psychiatric prescribing. A better understanding of blackbox warnings can enhance your clinical practice by informing safe prescribing practices, guiding shared decision-making, and improving documentation of your treatment decisions.

Related Resources

- US Food and Drug Administration. DRUGS@FDA: FDAapproved drug products. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Drug safety and availability. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability. Updated October 10, 2019.

- BlackBoxRx. www.blackboxrx.com. (Subscription required.)

- Mircromedex. www.micromedex.com. (Subscription required.)

- ePocrates. www.epocrates.com. (Subscription required.)

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Vanatrip

Amoxatine • Strattera

Amoxapine • Asendin

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Brexpiprazole • Rexulti

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Cariprazine • Vraylar

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Doxepin • Prudoxin, Silenor

Droperidol • Inapsine

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Esketamine • Spravato

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Haloperidol • Haldol

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Imipramine • Tofranil

Isocarboxazid • Marplan

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Linezolid • Zyvox

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Loxitane

Lurasidone • Latuda

Maprotiline • Ludiomil

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

Midazolam • Versed

Milnacipran • Savella

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • Revia, Vivitrol

Nefazodone • Serzone

Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paroxetine • Paxil

Perphenazine • Trilafon

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Prochlorperazine • Compro

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Selegiline • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

Trimipramine • Surmontil

Valproate • Depakote

Varenicline • Chantix, Wellbutrin

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Recently, the FDA issued “black-box” warnings, its most prominent drug safety statements, for esketamine,1 which is indicated for treatment-resistant depression, and the Z-drugs, which are indicated for insomnia2 (Table 1). A black-box warning also comes with brexanolone, which was recently approved for postpartum depression.3 While these newly issued warnings serve as a timely reminder of the importance of black-box warnings, older black-box warnings also cover large areas of psychiatric prescribing, including all medications indicated for treating psychosis or schizophrenia (increased mortality in patients with dementia), and all psychotropic medications with a depression indication (suicidality in younger people).

In this article, we help busy prescribers navigate the landscape of black-box warnings by providing a concise review of how to use them in clinical practice, and where to find information to keep up-to-date.

What are black-box warnings?

A black-box warning is a summary of the potential serious or life-threatening risks of a specific prescription medication. The black-box warning is formatted within a black border found at the top of the manufacturer’s prescribing information document (also known as the package insert or product label). Below the black-box warning, potential risks appear in descending order in sections titled “Contraindications,” “Warnings and Precautions,” and “Adverse Reactions.”4 The FDA issues black-box warnings either during drug development, to take effect upon approval of a new agent, or (more commonly) based on post-marketing safety information,5 which the FDA continuously gathers from reports by patients, clinicians, and industry.6 Federal law mandates the existence of black-box warnings, stating in part that, “special problems, particularly those that may lead to death or serious injury, may be required by the [FDA] to be placed in a prominently displayed box” (21 CFR 201.57(e)).

When is a black-box warning necessary?

The FDA issues a black-box warning based upon its judgment of the seriousness of the adverse effect. However, by definition, these risks do not inherently outweigh the benefits a medication may offer to certain patients. According to the FDA,7 black-box warnings are placed when: