User login

Recognizing Burnout: Why Physicians Often Miss the Signs in Themselves

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: This section explores why physicians often struggle to recognize burnout within themselves, partly due to stigma and a tendency to focus on productivity over well-being. Dr. Tyra Fainstad shares personal experiences of burnout symptoms, emphasizing the importance of awareness and self-reflection. Recognizing and addressing burnout early can help physicians find healthier coping strategies, avoid productivity traps, and seek support.

Key Takeaways:

- Many physicians struggle to identify burnout due to stigma and self-blame.

- Awareness of burnout symptoms is essential for early intervention and healthy coping.

- Seeking support can prevent burnout from worsening and improve quality of life.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

Lotte Dyrbye, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Co-inventor of the Well-being Index and its derivatives, which Mayo Clinic has licensed. Dyrbye receives royalties.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: This section explores why physicians often struggle to recognize burnout within themselves, partly due to stigma and a tendency to focus on productivity over well-being. Dr. Tyra Fainstad shares personal experiences of burnout symptoms, emphasizing the importance of awareness and self-reflection. Recognizing and addressing burnout early can help physicians find healthier coping strategies, avoid productivity traps, and seek support.

Key Takeaways:

- Many physicians struggle to identify burnout due to stigma and self-blame.

- Awareness of burnout symptoms is essential for early intervention and healthy coping.

- Seeking support can prevent burnout from worsening and improve quality of life.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

Lotte Dyrbye, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Co-inventor of the Well-being Index and its derivatives, which Mayo Clinic has licensed. Dyrbye receives royalties.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: This section explores why physicians often struggle to recognize burnout within themselves, partly due to stigma and a tendency to focus on productivity over well-being. Dr. Tyra Fainstad shares personal experiences of burnout symptoms, emphasizing the importance of awareness and self-reflection. Recognizing and addressing burnout early can help physicians find healthier coping strategies, avoid productivity traps, and seek support.

Key Takeaways:

- Many physicians struggle to identify burnout due to stigma and self-blame.

- Awareness of burnout symptoms is essential for early intervention and healthy coping.

- Seeking support can prevent burnout from worsening and improve quality of life.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

Lotte Dyrbye, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Co-inventor of the Well-being Index and its derivatives, which Mayo Clinic has licensed. Dyrbye receives royalties.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Breaking the Cycle: Why Self-Compassion Is Essential for Today’s Physicians

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad explores the ingrained culture in medicine that encourages self-criticism, with many physicians feeling that they must be hard on themselves to succeed. Dr Fainstad challenges this belief, advocating for self-compassion as a healthier alternative. The evolving medical field now includes physicians who prioritize well-being without sacrificing quality of care, underscoring the importance of self-kindness for sustainable practice.

Key Takeaways:

- Many physicians believe that self-criticism is necessary for success, a mindset rooted in medical culture.

- Practicing self-compassion can improve long-term resilience and prevent burnout.

- The changing landscape of healthcare supports a more balanced approach to physician well-being.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

Lotte Dyrbye, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Co-inventor of the Well-being Index and its derivatives, which Mayo Clinic has licensed. Dyrbye receives royalties.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad explores the ingrained culture in medicine that encourages self-criticism, with many physicians feeling that they must be hard on themselves to succeed. Dr Fainstad challenges this belief, advocating for self-compassion as a healthier alternative. The evolving medical field now includes physicians who prioritize well-being without sacrificing quality of care, underscoring the importance of self-kindness for sustainable practice.

Key Takeaways:

- Many physicians believe that self-criticism is necessary for success, a mindset rooted in medical culture.

- Practicing self-compassion can improve long-term resilience and prevent burnout.

- The changing landscape of healthcare supports a more balanced approach to physician well-being.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

Lotte Dyrbye, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Co-inventor of the Well-being Index and its derivatives, which Mayo Clinic has licensed. Dyrbye receives royalties.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad explores the ingrained culture in medicine that encourages self-criticism, with many physicians feeling that they must be hard on themselves to succeed. Dr Fainstad challenges this belief, advocating for self-compassion as a healthier alternative. The evolving medical field now includes physicians who prioritize well-being without sacrificing quality of care, underscoring the importance of self-kindness for sustainable practice.

Key Takeaways:

- Many physicians believe that self-criticism is necessary for success, a mindset rooted in medical culture.

- Practicing self-compassion can improve long-term resilience and prevent burnout.

- The changing landscape of healthcare supports a more balanced approach to physician well-being.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

Lotte Dyrbye, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Co-inventor of the Well-being Index and its derivatives, which Mayo Clinic has licensed. Dyrbye receives royalties.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Finding Fulfillment Beyond Metrics: A Physician’s Path to Lasting Well-Being

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad shares her personal experience with burnout and the journey to recovery through coaching and self-compassion. She describes the pressures of seeking validation through external achievements, which ultimately led to a crisis in self-worth after medical training. Through coaching, she learned to cultivate a sense of internal fulfillment, reconnecting with her passion for medicine and achieving a healthier balance.

Key Takeaways:

- Relying solely on external validation can deepen burnout and affect well-being.

- Coaching empowers physicians to develop self-compassion and sustainable coping strategies.

- Shifting from external to internal validation strengthens long-term fulfillment and job satisfaction.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad shares her personal experience with burnout and the journey to recovery through coaching and self-compassion. She describes the pressures of seeking validation through external achievements, which ultimately led to a crisis in self-worth after medical training. Through coaching, she learned to cultivate a sense of internal fulfillment, reconnecting with her passion for medicine and achieving a healthier balance.

Key Takeaways:

- Relying solely on external validation can deepen burnout and affect well-being.

- Coaching empowers physicians to develop self-compassion and sustainable coping strategies.

- Shifting from external to internal validation strengthens long-term fulfillment and job satisfaction.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad shares her personal experience with burnout and the journey to recovery through coaching and self-compassion. She describes the pressures of seeking validation through external achievements, which ultimately led to a crisis in self-worth after medical training. Through coaching, she learned to cultivate a sense of internal fulfillment, reconnecting with her passion for medicine and achieving a healthier balance.

Key Takeaways:

- Relying solely on external validation can deepen burnout and affect well-being.

- Coaching empowers physicians to develop self-compassion and sustainable coping strategies.

- Shifting from external to internal validation strengthens long-term fulfillment and job satisfaction.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Portrait of the Patient

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

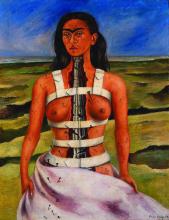

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Telehealth Vs In-Person Diabetes Care: Is One Better?

Adults with diabetes who participated in telehealth visits reported similar levels of care, trust in the healthcare system, and patient-centered communication compared to those who had in-person visits, a cross-sectional study suggested.

The authors urged continued integration of telehealth into diabetes care beyond December 31, 2024, when the pandemic public health emergency ends, potentially limiting such services.

The study “provides population-level evidence that telehealth can deliver care quality comparable to in-person visits in diabetes management,” lead author Young-Rock Hong, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in the University of Florida, Gainesville, told this news organization.

“Perhaps the most meaningful finding was the high utilization of telephone-only visits among older adults,” he said. “This has important policy implications, particularly as some insurers and healthcare systems have pushed to restrict telehealth coverage to video-only visits.”

“Maintaining telephone visit coverage is crucial for equitable access, especially for older adults who may be less comfortable with video technology; those with limited internet access; or patients facing other barriers to video visits,” he explained.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

Video-only, Voice-only, Both

The researchers did a secondary analysis of data from the 2022 Health Information National Trends Survey, a nationally representative survey that includes information on health communication and knowledge and perceptions about all health conditions among US adults aged ≥ 18 years.

Participants had a self-reported diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The mean age was 59.4 years; 50% were women; and 53% were non-Hispanic White individuals.

Primary and secondary outcomes were use of telehealth in the last 12-months; telehealth modality; overall perception of quality of care; perceived trust in the healthcare system; and patient-centered communication score.

In the analysis of 1116 participants representing 33.6 million individuals, 48.1% reported telehealth use in the past 12 months.

Telehealth users were more likely to be younger and women with higher household incomes and health insurance coverage; live in metropolitan areas; and have multiple chronic conditions, poorer perceived health status, and more frequent physician visits than nonusers.

After adjustment, adults aged ≥ 65 years had a significantly lower likelihood of telehealth use than those ages 18-49 years (odds ratio [OR], 0.43).

Higher income and more frequent healthcare visits were predictors of telehealth usage, with no significant differences across race, education, or location.

Those with a household income between $35,000 and $74,999 had more than double the likelihood of telehealth use (OR, 2.14) than those with incomes below $35,000.

Among telehealth users, 39.3% reported having video-only; 35%, phone (voice)-only; and 25.7%, both modalities. Among those aged ≥ 65 years, 55.5% used phone calls only and 25.5% used video only. In contrast, those aged 18-49 years had higher rates of video-only use (36.1%) and combined video/phone use (31.2%).

Healthcare provider recommendation (68.1%) was the most common reason for telehealth use, followed by convenience (57.7%), avoiding potential COVID-19 exposure (48.1%), and obtaining advice about the need for in-person care (23.6%).

Nonusers said they preferred in-person visits and also cited privacy concerns and technology challenges.

Patient-reported quality-of-care outcomes were comparable between telehealth users and nonusers, with no significant differences by telehealth modality or area of residence (urban or rural).

Around 70% of individuals with diabetes in both groups rated their quality of care as “excellent” and “very good;” fewer than 10% rated their care as “fair” and “poor.”

Similarly, trust in the healthcare system was comparable between users and nonusers: 41.3% of telehealth users 41% of nonusers reported trusting the healthcare system “very much.” Patient-centered communication scores were also similar between users and nonusers.

Telehealth appears to be a good option from the providers’ perspective as well, according to the authors. A previous study by the team found more than 80% of US physicians intended to continue telehealth beyond the pandemic.

“The recent unanimous bipartisan passage of the Telehealth Modernization Act by the House Energy & Commerce Committee signals strong political support for extending telehealth flexibilities through 2026,” Hong said. “The bill addresses key access issues by permanently removing geographic restrictions, expanding eligible providers, and maintaining audio-only coverage — provisions that align with our study’s findings about the importance of telephone visits, particularly for older adults and underserved populations.”

There is concern that extending telehealth services might increase Medicare spending by over $2 billion, he added. “While this may be a valid concern, there is a need for more robust evidence regarding the overall value of telehealth services — ie, the ‘benefits’ they provide relative to their costs and outcomes.”

Reassuring, but More Research Needed

COVID prompted “dramatic shifts” in care delivery from in-person to telehealth, Kevin Peterson, MD, MPH, American Diabetes Association vice president of primary care told this news organization. “The authors’ findings provide reassurance that these changes provided for additional convenience in care delivery without being associated with compromises in patient-reported care quality.”

However, he said, “the study does not necessarily capture representative samples of rural and underserved populations, making the impact of telehealth on health equity difficult to determine.” In addition, although patient-perceived care quality did not change with telehealth delivery, the study “does not address impacts on safety, clinical outcomes, equity, costs, or other important measures.”

Furthermore, he noted, “this is an association study that occurred during the dramatic changes brought about by COVID. It may not represent provider or patient preferences that characterize the role of telehealth under more normal circumstances.”

For now, clinicians should be aware that “initial evidence suggests that telehealth can be integrated into care without significantly compromising the patient’s perception of the quality of care,” he concluded.

No funding was declared. Hong and Peterson reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adults with diabetes who participated in telehealth visits reported similar levels of care, trust in the healthcare system, and patient-centered communication compared to those who had in-person visits, a cross-sectional study suggested.

The authors urged continued integration of telehealth into diabetes care beyond December 31, 2024, when the pandemic public health emergency ends, potentially limiting such services.

The study “provides population-level evidence that telehealth can deliver care quality comparable to in-person visits in diabetes management,” lead author Young-Rock Hong, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in the University of Florida, Gainesville, told this news organization.

“Perhaps the most meaningful finding was the high utilization of telephone-only visits among older adults,” he said. “This has important policy implications, particularly as some insurers and healthcare systems have pushed to restrict telehealth coverage to video-only visits.”

“Maintaining telephone visit coverage is crucial for equitable access, especially for older adults who may be less comfortable with video technology; those with limited internet access; or patients facing other barriers to video visits,” he explained.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

Video-only, Voice-only, Both

The researchers did a secondary analysis of data from the 2022 Health Information National Trends Survey, a nationally representative survey that includes information on health communication and knowledge and perceptions about all health conditions among US adults aged ≥ 18 years.

Participants had a self-reported diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The mean age was 59.4 years; 50% were women; and 53% were non-Hispanic White individuals.

Primary and secondary outcomes were use of telehealth in the last 12-months; telehealth modality; overall perception of quality of care; perceived trust in the healthcare system; and patient-centered communication score.

In the analysis of 1116 participants representing 33.6 million individuals, 48.1% reported telehealth use in the past 12 months.

Telehealth users were more likely to be younger and women with higher household incomes and health insurance coverage; live in metropolitan areas; and have multiple chronic conditions, poorer perceived health status, and more frequent physician visits than nonusers.

After adjustment, adults aged ≥ 65 years had a significantly lower likelihood of telehealth use than those ages 18-49 years (odds ratio [OR], 0.43).

Higher income and more frequent healthcare visits were predictors of telehealth usage, with no significant differences across race, education, or location.

Those with a household income between $35,000 and $74,999 had more than double the likelihood of telehealth use (OR, 2.14) than those with incomes below $35,000.

Among telehealth users, 39.3% reported having video-only; 35%, phone (voice)-only; and 25.7%, both modalities. Among those aged ≥ 65 years, 55.5% used phone calls only and 25.5% used video only. In contrast, those aged 18-49 years had higher rates of video-only use (36.1%) and combined video/phone use (31.2%).

Healthcare provider recommendation (68.1%) was the most common reason for telehealth use, followed by convenience (57.7%), avoiding potential COVID-19 exposure (48.1%), and obtaining advice about the need for in-person care (23.6%).

Nonusers said they preferred in-person visits and also cited privacy concerns and technology challenges.

Patient-reported quality-of-care outcomes were comparable between telehealth users and nonusers, with no significant differences by telehealth modality or area of residence (urban or rural).

Around 70% of individuals with diabetes in both groups rated their quality of care as “excellent” and “very good;” fewer than 10% rated their care as “fair” and “poor.”

Similarly, trust in the healthcare system was comparable between users and nonusers: 41.3% of telehealth users 41% of nonusers reported trusting the healthcare system “very much.” Patient-centered communication scores were also similar between users and nonusers.

Telehealth appears to be a good option from the providers’ perspective as well, according to the authors. A previous study by the team found more than 80% of US physicians intended to continue telehealth beyond the pandemic.

“The recent unanimous bipartisan passage of the Telehealth Modernization Act by the House Energy & Commerce Committee signals strong political support for extending telehealth flexibilities through 2026,” Hong said. “The bill addresses key access issues by permanently removing geographic restrictions, expanding eligible providers, and maintaining audio-only coverage — provisions that align with our study’s findings about the importance of telephone visits, particularly for older adults and underserved populations.”

There is concern that extending telehealth services might increase Medicare spending by over $2 billion, he added. “While this may be a valid concern, there is a need for more robust evidence regarding the overall value of telehealth services — ie, the ‘benefits’ they provide relative to their costs and outcomes.”

Reassuring, but More Research Needed

COVID prompted “dramatic shifts” in care delivery from in-person to telehealth, Kevin Peterson, MD, MPH, American Diabetes Association vice president of primary care told this news organization. “The authors’ findings provide reassurance that these changes provided for additional convenience in care delivery without being associated with compromises in patient-reported care quality.”

However, he said, “the study does not necessarily capture representative samples of rural and underserved populations, making the impact of telehealth on health equity difficult to determine.” In addition, although patient-perceived care quality did not change with telehealth delivery, the study “does not address impacts on safety, clinical outcomes, equity, costs, or other important measures.”

Furthermore, he noted, “this is an association study that occurred during the dramatic changes brought about by COVID. It may not represent provider or patient preferences that characterize the role of telehealth under more normal circumstances.”

For now, clinicians should be aware that “initial evidence suggests that telehealth can be integrated into care without significantly compromising the patient’s perception of the quality of care,” he concluded.

No funding was declared. Hong and Peterson reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adults with diabetes who participated in telehealth visits reported similar levels of care, trust in the healthcare system, and patient-centered communication compared to those who had in-person visits, a cross-sectional study suggested.

The authors urged continued integration of telehealth into diabetes care beyond December 31, 2024, when the pandemic public health emergency ends, potentially limiting such services.

The study “provides population-level evidence that telehealth can deliver care quality comparable to in-person visits in diabetes management,” lead author Young-Rock Hong, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in the University of Florida, Gainesville, told this news organization.

“Perhaps the most meaningful finding was the high utilization of telephone-only visits among older adults,” he said. “This has important policy implications, particularly as some insurers and healthcare systems have pushed to restrict telehealth coverage to video-only visits.”

“Maintaining telephone visit coverage is crucial for equitable access, especially for older adults who may be less comfortable with video technology; those with limited internet access; or patients facing other barriers to video visits,” he explained.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

Video-only, Voice-only, Both

The researchers did a secondary analysis of data from the 2022 Health Information National Trends Survey, a nationally representative survey that includes information on health communication and knowledge and perceptions about all health conditions among US adults aged ≥ 18 years.

Participants had a self-reported diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The mean age was 59.4 years; 50% were women; and 53% were non-Hispanic White individuals.

Primary and secondary outcomes were use of telehealth in the last 12-months; telehealth modality; overall perception of quality of care; perceived trust in the healthcare system; and patient-centered communication score.

In the analysis of 1116 participants representing 33.6 million individuals, 48.1% reported telehealth use in the past 12 months.

Telehealth users were more likely to be younger and women with higher household incomes and health insurance coverage; live in metropolitan areas; and have multiple chronic conditions, poorer perceived health status, and more frequent physician visits than nonusers.

After adjustment, adults aged ≥ 65 years had a significantly lower likelihood of telehealth use than those ages 18-49 years (odds ratio [OR], 0.43).

Higher income and more frequent healthcare visits were predictors of telehealth usage, with no significant differences across race, education, or location.

Those with a household income between $35,000 and $74,999 had more than double the likelihood of telehealth use (OR, 2.14) than those with incomes below $35,000.

Among telehealth users, 39.3% reported having video-only; 35%, phone (voice)-only; and 25.7%, both modalities. Among those aged ≥ 65 years, 55.5% used phone calls only and 25.5% used video only. In contrast, those aged 18-49 years had higher rates of video-only use (36.1%) and combined video/phone use (31.2%).

Healthcare provider recommendation (68.1%) was the most common reason for telehealth use, followed by convenience (57.7%), avoiding potential COVID-19 exposure (48.1%), and obtaining advice about the need for in-person care (23.6%).

Nonusers said they preferred in-person visits and also cited privacy concerns and technology challenges.

Patient-reported quality-of-care outcomes were comparable between telehealth users and nonusers, with no significant differences by telehealth modality or area of residence (urban or rural).

Around 70% of individuals with diabetes in both groups rated their quality of care as “excellent” and “very good;” fewer than 10% rated their care as “fair” and “poor.”

Similarly, trust in the healthcare system was comparable between users and nonusers: 41.3% of telehealth users 41% of nonusers reported trusting the healthcare system “very much.” Patient-centered communication scores were also similar between users and nonusers.

Telehealth appears to be a good option from the providers’ perspective as well, according to the authors. A previous study by the team found more than 80% of US physicians intended to continue telehealth beyond the pandemic.

“The recent unanimous bipartisan passage of the Telehealth Modernization Act by the House Energy & Commerce Committee signals strong political support for extending telehealth flexibilities through 2026,” Hong said. “The bill addresses key access issues by permanently removing geographic restrictions, expanding eligible providers, and maintaining audio-only coverage — provisions that align with our study’s findings about the importance of telephone visits, particularly for older adults and underserved populations.”

There is concern that extending telehealth services might increase Medicare spending by over $2 billion, he added. “While this may be a valid concern, there is a need for more robust evidence regarding the overall value of telehealth services — ie, the ‘benefits’ they provide relative to their costs and outcomes.”

Reassuring, but More Research Needed

COVID prompted “dramatic shifts” in care delivery from in-person to telehealth, Kevin Peterson, MD, MPH, American Diabetes Association vice president of primary care told this news organization. “The authors’ findings provide reassurance that these changes provided for additional convenience in care delivery without being associated with compromises in patient-reported care quality.”

However, he said, “the study does not necessarily capture representative samples of rural and underserved populations, making the impact of telehealth on health equity difficult to determine.” In addition, although patient-perceived care quality did not change with telehealth delivery, the study “does not address impacts on safety, clinical outcomes, equity, costs, or other important measures.”

Furthermore, he noted, “this is an association study that occurred during the dramatic changes brought about by COVID. It may not represent provider or patient preferences that characterize the role of telehealth under more normal circumstances.”

For now, clinicians should be aware that “initial evidence suggests that telehealth can be integrated into care without significantly compromising the patient’s perception of the quality of care,” he concluded.

No funding was declared. Hong and Peterson reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

The Emotional Cost of Nursing School: Depression

Nursing is a competitive field. In 2022, nursing schools rejected more than 78,000 qualified applications, and the students whose applications were accepted faced demanding schedules and rigorous academics and clinical rotations. Is this a recipe for depression?

In 2024, 38% of nursing students experienced depression — a 9.3% increase over 2019, according to research from higher education research group Degreechoices. Catherine A. Stubin, PhD, RN, assistant professor of nursing at Rutgers University–Camden in New Jersey, calls it “a mental health crisis in nursing.”

“Nursing is a very rigorous, difficult, psychologically and physically demanding profession,” she said. “If students don’t have the tools and resources to adequately deal with these stressors in nursing school, it’s going to carry over to their professional practice.”

A growing recognition of the toll that nursing programs may have on students’ mental health has led schools to launch initiatives to better support the next generation of nurses.

Diagnosing the Problem

Higher than average rates of depression among nursing students are not new. Nursing students often work long shifts with limited breaks. The academic rigors and clinical demands of caring for patients with acute and chronic conditions while instructors evaluate and watch for mistakes can cause high levels of stress, Stubin told this news organization. “Eventually, something has to give, and it’s usually their mental health.”

Clinical practicums often start when nursing students are still freshmen, and asking 18-year-old students to provide patient care in often-chaotic clinical environments is “overwhelming,” according to Stubin. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the issue.

During lockdown, more than half the nursing students reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and depression, which was attributed to the transition to online learning, fear of infection, burnout, and the psychological distress of lockdown.

“The pandemic exacerbated existing mental health problems in undergraduate nursing students,” said Stubin. “In the wake of it ... a lot of [registered nurses] have mental health issues and are leaving the profession.”

Helping Nurses Heal

A significant shift in the willingness to talk about mental health and seek treatment could help. In 2011, just one third of students participated in the treatment for a mental health disorder. The latest data show that 61% of students experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety take medication or seek therapy or counseling.

Incoming health sciences students at Ohio State University (OSU), Columbus, are screened for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and directed to campus health services as needed. Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, PhD, APRN-CNP, OSU’s chief wellness officer and former dean in the College of Nursing, believes it’s an essential step in supporting students, adding, “If you don’t screen, you don’t know the students are suffering, and we’re able to get help to the students who need it quickly.”

Prioritizing Solutions

Counseling services available through campus health centers are just one part of a multipronged approach that nursing schools have taken to improve the health and well-being of students. Nursing programs have also introduced initiatives to lower stress, prevent burnout, and relieve emotional trauma.

“In nursing education, we have to lay the groundwork for the self-care, wellness, and resilience practices that can, hopefully, be carried over into their professional practices,” Stubin said.

At Rutgers University–Camden, the wellness center provides counseling services, and the Student Nursing Association offers a pet therapy program. Stubin also incorporates self-care, resilience-building strategies, and wellness programming into the curriculum.

During the pandemic, the University of Colorado College of Nursing, Aurora, created a class called Stress Impact and Care for COVID-19 to provide content, exercises, and support groups for nursing students. The class was so popular that it was adapted and integrated into the curriculum.

The University of Vermont, Burlington, introduced the Benson-Henry Institute Stress Management and Resiliency Training program in 2021. The 8-week program was designed to teach nursing students coping strategies to reduce stress.

Offering stress management programs to first-year nursing students has been linked to improved problem-solving skills and fewer emotional and social behavioral symptoms. However, for programs to be effective, Melnyk believes that they need to be integrated into the curriculum, not offered as electives.

“We know mindfulness works, we know cognitive behavior skills-building works, and these types of evidence-based programs with such efficacy behind them should not be optional,” she said. “Students are overwhelmed just with their coursework, so if these programs exist for extra credit, students won’t take them.”

Creating a Culture of Wellness

Teaching nursing students how to manage stress and providing the resources to combat depression and anxiety is just the first step in building a healthy, resilient nursing workforce.

Prioritizing wellness in nursing isn’t just essential for addressing the nationwide nursing shortage. Burnout in the medical field costs the United States healthcare system $4.6 billion per year, and preventable medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States.

“There is a nice movement across the United States to reduce these mental health issues because they’re so costly,” Melnyk said.

There are also national efforts to address the issue. The National Academy of Medicine introduced the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, which has grown to include more than 200 organizations committed to reversing burnout and improving mental health in the clinical workforce. The American Nurses Foundation created The Nurse Well-Being: Building Peer and Leadership Support Program to provide resources and peer support to help nurses manage stress.

Health systems and hospitals also need to prioritize clinical well-being to reduce stress and burnout — and these efforts must be ongoing.

“These resources have to be extended into the working world ... and not just once a year for Nurses Week in May, but on a regular continued basis,” said Stubin. “Healthcare corporations and hospitals have to continue these resources and this help; it has to be a priority.”

Until the culture changes, Stubin fears that nursing students will continue facing barriers to completing their programs and maintaining nursing careers. Currently, 43% of college students considered leaving their program for mental health reasons, and 21.7% of nurses reported suicidal ideation.

“There’s a nursing shortage, and the acuity of patient care is increasing, so the stressors in the clinical area aren’t going to decrease,” Stubin said. “We as nursing faculty must teach our students how to manage these stressors to build a resilient, mentally and physically healthy workforce.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nursing is a competitive field. In 2022, nursing schools rejected more than 78,000 qualified applications, and the students whose applications were accepted faced demanding schedules and rigorous academics and clinical rotations. Is this a recipe for depression?

In 2024, 38% of nursing students experienced depression — a 9.3% increase over 2019, according to research from higher education research group Degreechoices. Catherine A. Stubin, PhD, RN, assistant professor of nursing at Rutgers University–Camden in New Jersey, calls it “a mental health crisis in nursing.”

“Nursing is a very rigorous, difficult, psychologically and physically demanding profession,” she said. “If students don’t have the tools and resources to adequately deal with these stressors in nursing school, it’s going to carry over to their professional practice.”

A growing recognition of the toll that nursing programs may have on students’ mental health has led schools to launch initiatives to better support the next generation of nurses.

Diagnosing the Problem

Higher than average rates of depression among nursing students are not new. Nursing students often work long shifts with limited breaks. The academic rigors and clinical demands of caring for patients with acute and chronic conditions while instructors evaluate and watch for mistakes can cause high levels of stress, Stubin told this news organization. “Eventually, something has to give, and it’s usually their mental health.”

Clinical practicums often start when nursing students are still freshmen, and asking 18-year-old students to provide patient care in often-chaotic clinical environments is “overwhelming,” according to Stubin. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the issue.

During lockdown, more than half the nursing students reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and depression, which was attributed to the transition to online learning, fear of infection, burnout, and the psychological distress of lockdown.

“The pandemic exacerbated existing mental health problems in undergraduate nursing students,” said Stubin. “In the wake of it ... a lot of [registered nurses] have mental health issues and are leaving the profession.”

Helping Nurses Heal

A significant shift in the willingness to talk about mental health and seek treatment could help. In 2011, just one third of students participated in the treatment for a mental health disorder. The latest data show that 61% of students experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety take medication or seek therapy or counseling.

Incoming health sciences students at Ohio State University (OSU), Columbus, are screened for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and directed to campus health services as needed. Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, PhD, APRN-CNP, OSU’s chief wellness officer and former dean in the College of Nursing, believes it’s an essential step in supporting students, adding, “If you don’t screen, you don’t know the students are suffering, and we’re able to get help to the students who need it quickly.”

Prioritizing Solutions

Counseling services available through campus health centers are just one part of a multipronged approach that nursing schools have taken to improve the health and well-being of students. Nursing programs have also introduced initiatives to lower stress, prevent burnout, and relieve emotional trauma.

“In nursing education, we have to lay the groundwork for the self-care, wellness, and resilience practices that can, hopefully, be carried over into their professional practices,” Stubin said.

At Rutgers University–Camden, the wellness center provides counseling services, and the Student Nursing Association offers a pet therapy program. Stubin also incorporates self-care, resilience-building strategies, and wellness programming into the curriculum.

During the pandemic, the University of Colorado College of Nursing, Aurora, created a class called Stress Impact and Care for COVID-19 to provide content, exercises, and support groups for nursing students. The class was so popular that it was adapted and integrated into the curriculum.

The University of Vermont, Burlington, introduced the Benson-Henry Institute Stress Management and Resiliency Training program in 2021. The 8-week program was designed to teach nursing students coping strategies to reduce stress.

Offering stress management programs to first-year nursing students has been linked to improved problem-solving skills and fewer emotional and social behavioral symptoms. However, for programs to be effective, Melnyk believes that they need to be integrated into the curriculum, not offered as electives.

“We know mindfulness works, we know cognitive behavior skills-building works, and these types of evidence-based programs with such efficacy behind them should not be optional,” she said. “Students are overwhelmed just with their coursework, so if these programs exist for extra credit, students won’t take them.”

Creating a Culture of Wellness

Teaching nursing students how to manage stress and providing the resources to combat depression and anxiety is just the first step in building a healthy, resilient nursing workforce.

Prioritizing wellness in nursing isn’t just essential for addressing the nationwide nursing shortage. Burnout in the medical field costs the United States healthcare system $4.6 billion per year, and preventable medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States.

“There is a nice movement across the United States to reduce these mental health issues because they’re so costly,” Melnyk said.

There are also national efforts to address the issue. The National Academy of Medicine introduced the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, which has grown to include more than 200 organizations committed to reversing burnout and improving mental health in the clinical workforce. The American Nurses Foundation created The Nurse Well-Being: Building Peer and Leadership Support Program to provide resources and peer support to help nurses manage stress.

Health systems and hospitals also need to prioritize clinical well-being to reduce stress and burnout — and these efforts must be ongoing.

“These resources have to be extended into the working world ... and not just once a year for Nurses Week in May, but on a regular continued basis,” said Stubin. “Healthcare corporations and hospitals have to continue these resources and this help; it has to be a priority.”

Until the culture changes, Stubin fears that nursing students will continue facing barriers to completing their programs and maintaining nursing careers. Currently, 43% of college students considered leaving their program for mental health reasons, and 21.7% of nurses reported suicidal ideation.

“There’s a nursing shortage, and the acuity of patient care is increasing, so the stressors in the clinical area aren’t going to decrease,” Stubin said. “We as nursing faculty must teach our students how to manage these stressors to build a resilient, mentally and physically healthy workforce.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nursing is a competitive field. In 2022, nursing schools rejected more than 78,000 qualified applications, and the students whose applications were accepted faced demanding schedules and rigorous academics and clinical rotations. Is this a recipe for depression?

In 2024, 38% of nursing students experienced depression — a 9.3% increase over 2019, according to research from higher education research group Degreechoices. Catherine A. Stubin, PhD, RN, assistant professor of nursing at Rutgers University–Camden in New Jersey, calls it “a mental health crisis in nursing.”

“Nursing is a very rigorous, difficult, psychologically and physically demanding profession,” she said. “If students don’t have the tools and resources to adequately deal with these stressors in nursing school, it’s going to carry over to their professional practice.”

A growing recognition of the toll that nursing programs may have on students’ mental health has led schools to launch initiatives to better support the next generation of nurses.

Diagnosing the Problem

Higher than average rates of depression among nursing students are not new. Nursing students often work long shifts with limited breaks. The academic rigors and clinical demands of caring for patients with acute and chronic conditions while instructors evaluate and watch for mistakes can cause high levels of stress, Stubin told this news organization. “Eventually, something has to give, and it’s usually their mental health.”

Clinical practicums often start when nursing students are still freshmen, and asking 18-year-old students to provide patient care in often-chaotic clinical environments is “overwhelming,” according to Stubin. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the issue.

During lockdown, more than half the nursing students reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and depression, which was attributed to the transition to online learning, fear of infection, burnout, and the psychological distress of lockdown.

“The pandemic exacerbated existing mental health problems in undergraduate nursing students,” said Stubin. “In the wake of it ... a lot of [registered nurses] have mental health issues and are leaving the profession.”

Helping Nurses Heal

A significant shift in the willingness to talk about mental health and seek treatment could help. In 2011, just one third of students participated in the treatment for a mental health disorder. The latest data show that 61% of students experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety take medication or seek therapy or counseling.

Incoming health sciences students at Ohio State University (OSU), Columbus, are screened for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and directed to campus health services as needed. Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, PhD, APRN-CNP, OSU’s chief wellness officer and former dean in the College of Nursing, believes it’s an essential step in supporting students, adding, “If you don’t screen, you don’t know the students are suffering, and we’re able to get help to the students who need it quickly.”

Prioritizing Solutions

Counseling services available through campus health centers are just one part of a multipronged approach that nursing schools have taken to improve the health and well-being of students. Nursing programs have also introduced initiatives to lower stress, prevent burnout, and relieve emotional trauma.

“In nursing education, we have to lay the groundwork for the self-care, wellness, and resilience practices that can, hopefully, be carried over into their professional practices,” Stubin said.

At Rutgers University–Camden, the wellness center provides counseling services, and the Student Nursing Association offers a pet therapy program. Stubin also incorporates self-care, resilience-building strategies, and wellness programming into the curriculum.

During the pandemic, the University of Colorado College of Nursing, Aurora, created a class called Stress Impact and Care for COVID-19 to provide content, exercises, and support groups for nursing students. The class was so popular that it was adapted and integrated into the curriculum.

The University of Vermont, Burlington, introduced the Benson-Henry Institute Stress Management and Resiliency Training program in 2021. The 8-week program was designed to teach nursing students coping strategies to reduce stress.

Offering stress management programs to first-year nursing students has been linked to improved problem-solving skills and fewer emotional and social behavioral symptoms. However, for programs to be effective, Melnyk believes that they need to be integrated into the curriculum, not offered as electives.

“We know mindfulness works, we know cognitive behavior skills-building works, and these types of evidence-based programs with such efficacy behind them should not be optional,” she said. “Students are overwhelmed just with their coursework, so if these programs exist for extra credit, students won’t take them.”

Creating a Culture of Wellness

Teaching nursing students how to manage stress and providing the resources to combat depression and anxiety is just the first step in building a healthy, resilient nursing workforce.

Prioritizing wellness in nursing isn’t just essential for addressing the nationwide nursing shortage. Burnout in the medical field costs the United States healthcare system $4.6 billion per year, and preventable medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States.

“There is a nice movement across the United States to reduce these mental health issues because they’re so costly,” Melnyk said.

There are also national efforts to address the issue. The National Academy of Medicine introduced the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, which has grown to include more than 200 organizations committed to reversing burnout and improving mental health in the clinical workforce. The American Nurses Foundation created The Nurse Well-Being: Building Peer and Leadership Support Program to provide resources and peer support to help nurses manage stress.

Health systems and hospitals also need to prioritize clinical well-being to reduce stress and burnout — and these efforts must be ongoing.

“These resources have to be extended into the working world ... and not just once a year for Nurses Week in May, but on a regular continued basis,” said Stubin. “Healthcare corporations and hospitals have to continue these resources and this help; it has to be a priority.”

Until the culture changes, Stubin fears that nursing students will continue facing barriers to completing their programs and maintaining nursing careers. Currently, 43% of college students considered leaving their program for mental health reasons, and 21.7% of nurses reported suicidal ideation.

“There’s a nursing shortage, and the acuity of patient care is increasing, so the stressors in the clinical area aren’t going to decrease,” Stubin said. “We as nursing faculty must teach our students how to manage these stressors to build a resilient, mentally and physically healthy workforce.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lessons Learned: What Docs Wish Med Students Knew

Despite 4 years of med school and 3-7 years in residency, when you enter the workforce as a doctor, you still have much to learn. There is only so much your professors and attending physicians can pack in. Going forward, you’ll continue to learn on the job and via continuing education.

Some of that lifelong learning will involve soft skills — how to compassionately work with your patients and their families, for instance. Other lessons will get down to the business of medicine — the paperwork, the work/life balance, and the moral dilemmas you never saw coming. And still others will involve learning how to take care of yourself in the middle of seemingly endless hours on the job.

“We all have things we wish we had known upon starting our careers,” said Daniel Opris, MD, a primary care physician at Ohio-based Executive Medical Centers.

We tapped several veteran physicians and an educator to learn what they wish med students knew as they enter the workforce. We’ve compiled them here to give you a head start on the lessons ahead.

You Won’t Know Everything, and That’s Okay

When you go through your medical training, it can feel overwhelming to absorb all the knowledge your professors and attendings impart. The bottom line, said Shoshana Ungerleider, MD, an internal medicine specialist, is that you shouldn’t worry about it.

David Lenihan, PhD, CEO at Ponce Health Sciences University, agrees. “What we’ve lost in recent years, is the ability to apply your skill set and say, ‘let me take a day and get back to you,’” he said. “Doctors love it when you do that because it shows you can pitch in and work as part of a team.”

Medicine is a collaborative field, said Ungerleider, and learning from others, whether peers, nurses, or specialists, is “not a weakness.” She recommends embracing uncertainty and getting comfortable with the unknown.

You’ll Take Your Work Home With You

Doctors enter the field because they care about their patients and want to help. Successful outcomes are never guaranteed, however, no matter how much you try. The result? Some days you’ll bring home those upsetting and haunting cases, said Lenihan.

“We often believe that we should leave our work at the office, but sometimes you need to bring it home and think it through,” he said. “It can’t overwhelm you, but you should digest what happened.”

When you do, said Lenihan, you’ll come out the other end more empathetic and that helps the healthcare system in the long run. “The more you reflect on your day, the better you’ll get at reading the room and treating your patients.”

Drew Remignanti, MD, a retired emergency medicine physician from New Hampshire, agrees, but puts a different spin on bringing work home.

“We revisit the patient care decisions we made, second-guess ourselves, and worry about our patients’ welfare and outcomes,” he said. “I think it can only lead to better outcomes down the road, however, if you learn from that bad decision, preventing you from committing a similar mistake.”

Burnout Is Real — Make Self-Care a Priority

As a retired physician who spent 40 years practicing medicine, Remignanti experienced the evolution of healthcare as it has become what he calls a “consumer-provider” model. “Productivity didn’t use to be part of the equation, but now it’s the focus,” he said.

The result is burnout, a very real threat to incoming physicians. Remignanti holds that if you are aware of the risk, you can resist it. Part of avoiding burnout is self-care, according to Ungerleider. “The sooner you prioritize your mental, emotional, and physical well-being, the better,” she said. “Balancing work and life may feel impossible at times but taking care of yourself is essential to being a better physician in the long run.”

That means carving out time for exercise, hobbies, and connections outside of the medical field. It also means making sleep and nutrition a priority, even when that feels hard to accomplish. “If you don’t take care of yourself, you can’t take care of others,” added Opris. “It’s so common to lose yourself in your career, but you need to hold onto your physical, emotional, and spiritual self.”

Avoid Relying Too Heavily on Tech

Technology is invading every aspect of our lives — often for the greater good — but in medicine, it’s important to always return to your core knowledge above all else. Case in point, said Opris, the UpToDate app. While it can be a useful tool, it’s important not to become too reliant on it. “UpToDate is expert opinion-based guidance, and it’s a fantastic resource,” he said. “But you need to use your references and knowledge in every case.”

It’s key to remember that every patient is different, and their case may not line up perfectly with the guidance presented in UpToDate or other technology source. Piggybacking on that, Ungerleider added that it’s important to remember medicine is about people, not just conditions.

“It’s easy to focus on mastering the science, but the real art of medicine comes from seeing the whole person in front of you,” she said. “Your patients are more than their diagnoses — they come with complex emotions, life stories, and needs.” Being compassionate, listening carefully, and building trust should match up to your clinical skills.

Partner With Your Patients, Even When It’s Difficult

Perhaps the most difficult lesson of all is remembering that your patients may not always agree with your recommendations and choose to ignore them. After all your years spent learning, there may be times when it feels your education is going to waste.

“Remember that the landscape today is so varied, and that bleeds into medicine,” said Opris. “We go into cases with our own biases, and it’s important to take a step back to reset, every time.”

Opris reminds himself of Sir William Osler’s famous essay, “Aequanimitas,” in which he tells graduating medical students to practice with “coolness and presence of mind under all circumstances.”

Remignanti offers this advice: “Physicians need to be able to partner with their patients and jointly decide which courses of action are most effective,” he said. “Cling to the idea that you are forming a partnership with your patients — what can we together determine is the best course?”

At the same time, the path the patient chooses may not be what’s best for them — potentially even leading to a poor outcome.

“You may not always understand their choices,” said Opris. “But they do have a choice. Think of yourself almost like a consultant.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite 4 years of med school and 3-7 years in residency, when you enter the workforce as a doctor, you still have much to learn. There is only so much your professors and attending physicians can pack in. Going forward, you’ll continue to learn on the job and via continuing education.

Some of that lifelong learning will involve soft skills — how to compassionately work with your patients and their families, for instance. Other lessons will get down to the business of medicine — the paperwork, the work/life balance, and the moral dilemmas you never saw coming. And still others will involve learning how to take care of yourself in the middle of seemingly endless hours on the job.

“We all have things we wish we had known upon starting our careers,” said Daniel Opris, MD, a primary care physician at Ohio-based Executive Medical Centers.

We tapped several veteran physicians and an educator to learn what they wish med students knew as they enter the workforce. We’ve compiled them here to give you a head start on the lessons ahead.

You Won’t Know Everything, and That’s Okay

When you go through your medical training, it can feel overwhelming to absorb all the knowledge your professors and attendings impart. The bottom line, said Shoshana Ungerleider, MD, an internal medicine specialist, is that you shouldn’t worry about it.

David Lenihan, PhD, CEO at Ponce Health Sciences University, agrees. “What we’ve lost in recent years, is the ability to apply your skill set and say, ‘let me take a day and get back to you,’” he said. “Doctors love it when you do that because it shows you can pitch in and work as part of a team.”

Medicine is a collaborative field, said Ungerleider, and learning from others, whether peers, nurses, or specialists, is “not a weakness.” She recommends embracing uncertainty and getting comfortable with the unknown.

You’ll Take Your Work Home With You

Doctors enter the field because they care about their patients and want to help. Successful outcomes are never guaranteed, however, no matter how much you try. The result? Some days you’ll bring home those upsetting and haunting cases, said Lenihan.

“We often believe that we should leave our work at the office, but sometimes you need to bring it home and think it through,” he said. “It can’t overwhelm you, but you should digest what happened.”

When you do, said Lenihan, you’ll come out the other end more empathetic and that helps the healthcare system in the long run. “The more you reflect on your day, the better you’ll get at reading the room and treating your patients.”

Drew Remignanti, MD, a retired emergency medicine physician from New Hampshire, agrees, but puts a different spin on bringing work home.

“We revisit the patient care decisions we made, second-guess ourselves, and worry about our patients’ welfare and outcomes,” he said. “I think it can only lead to better outcomes down the road, however, if you learn from that bad decision, preventing you from committing a similar mistake.”

Burnout Is Real — Make Self-Care a Priority

As a retired physician who spent 40 years practicing medicine, Remignanti experienced the evolution of healthcare as it has become what he calls a “consumer-provider” model. “Productivity didn’t use to be part of the equation, but now it’s the focus,” he said.

The result is burnout, a very real threat to incoming physicians. Remignanti holds that if you are aware of the risk, you can resist it. Part of avoiding burnout is self-care, according to Ungerleider. “The sooner you prioritize your mental, emotional, and physical well-being, the better,” she said. “Balancing work and life may feel impossible at times but taking care of yourself is essential to being a better physician in the long run.”