User login

Stroke risk in new-onset atrial fib goes up with greater alcohol intake

There’s abundant evidence linking higher alcohol intake levels to greater stroke risk and, separately, increasing risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). Less settled is whether moderate to heavy drinking worsens the risk for stroke in patients already in AFib and whether giving up alcohol can attenuate that risk. A new observational study suggests the answer to both questions is yes.

The risk for ischemic stroke was only around 1% over about 5 years in a Korean nationwide cohort of almost 98,000 patients with new-onset AFib. About half the patients followed were nondrinkers, as they had been before the study, 13% became abstinent soon after their AFib diagnosis, and 36% were currently drinkers.

But stroke risk went up about 30% with “moderate” current alcohol intake, compared with no intake, and by more than 40% for current drinkers reporting “heavy” alcohol intake, researchers found in an adjusted analysis.

However, abstainers who had mild to moderate alcohol-intake levels before their AFib diagnosis “had a similar risk of ischemic stroke as nondrinkers,” write the authors, led by So-Ryoung Lee, MD, PhD, and colleagues, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, in their report published June 7 in the European Heart Journal. In a secondary analysis, binge drinking was also independently associated with risk for ischemic stroke.

The findings suggest that “alcohol abstinence after the diagnosis of AFib could reduce the risk of ischemic stroke,” they conclude. “Lifestyle interventions, including attention to alcohol consumption, should be encouraged as part of a comprehensive approach in the management of patients with a new diagnosis of AFib” for lowering the risk for stroke and other clinical outcomes.

“These results are pretty comparable to those obtained in the more general population,” David Conen, MD, MPH, not connected to the analysis, told this news organization.

In the study’s population with new-onset AFib, there is an alcohol-dependent risk for stroke “that goes up with increasing alcohol intake, which is more or less similar to that found without atrial fibrillation in previous studies,” said Dr. Conen, from the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The study, “which overall I think is very well done,” he said, is noteworthy for also suggesting that binge drinking, which was scrutinized in a secondary analysis, appeared independently to worsen the risk for stroke in its AFib population.

Dr. Conen said the observed 1% overall risk for stroke was very similar to the rate he and his colleagues saw in a recent combined analysis of two European cohorts with AFib that was usually longer standing; the median was 3 years. That analysis, in contrast, showed no significant association between increasing levels of alcohol intake and risk for stroke or systemic embolism.

However, “our confidence limits did not exclude the possibility of a small to moderate association,” he said. Given that, and the current study from Korea, there might indeed be “a weak association between alcohol consumption and stroke” in patients with AFib.

“Their results are just more precise because of the larger sample size. That’s why they were able to show those associations,” said Dr. Conen, who was senior author on the earlier report, which covered a pooled analysis of 3,852 patients with AFib in the BEAT-AF and SWISS-AF cohort studies. It was published January 25 in CMAJ, with lead author Philipp Reddiess, MD, Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel, Switzerland.

The two published studies contrast in other ways that are worth noting and together suggest the stroke rate might have been 1% in both by chance, Dr. Conen said. “The populations were pretty different.”

In the earlier study, for example, the overwhelmingly European patients had more comorbidities and had been in AFib for much longer; their mean age was 71 years; and 84% were on oral anticoagulation (OAC).

In contrast, the Korean cohort averaged 61 years in age and only about 24% were taking oral anticoagulants. Given their distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc scores and mean score of 2.3, more than twice as many should have been on OAC, Dr. Conen speculated. “Even if you take into account that some patients may have contraindications, this is clearly an underanticoagulated population.”

The European cohort might have been “a little bit more representative because atrial fibrillation is a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Conen said, but “the Korean paper has the advantage of being a population-based study.”

It involved 97,869 patients from a Korean national data base who were newly diagnosed with AFib from 2010 to 2016. Of the total, 49,781 (51%) were continuously nondrinkers before and after their diagnosis; 12,789 (13%) abstained from alcohol only after their AFib diagnosis; and 35,299 (36%) were drinkers during the follow-up, either because they continued to drink or newly started after their diagnosis.

Of the cohort, 3,120 were diagnosed with new ischemic stroke over a follow-up of 310,926 person-years, for a rate of 1 per 100 person-years.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke over a 5-year follow-up, compared with nondrinkers, was:

- 1.127 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.266) among abstainers

- 1.280 (95% CI, 1.166-1.405) for current drinkers

The corresponding HR, compared with current drinkers, was:

- 0.781 (95% CI, 0.712-0.858) for nondrinkers

- 0.880 (95% CI, 0.782-0.990) among abstainers

No significant interactions with ischemic stroke risk were observed in groups by sex, age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, or smoking status. The risk rose consistently with current drinking levels.

The overall stroke rate of 1% per year is “very low,” and “the absolute differences are small, even though there is a clear significant trend from nondrinking to drinking,” Dr. Conen said.

However, “the difference becomes more sizable when you compare heavy drinking to abstinence.”

Dr. Lee reports no conflicts of interest; disclosures for the other authors are in their report. Dr. Conen reports receiving speaker fees from Servier Canada; disclosures for the other authors are in their report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There’s abundant evidence linking higher alcohol intake levels to greater stroke risk and, separately, increasing risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). Less settled is whether moderate to heavy drinking worsens the risk for stroke in patients already in AFib and whether giving up alcohol can attenuate that risk. A new observational study suggests the answer to both questions is yes.

The risk for ischemic stroke was only around 1% over about 5 years in a Korean nationwide cohort of almost 98,000 patients with new-onset AFib. About half the patients followed were nondrinkers, as they had been before the study, 13% became abstinent soon after their AFib diagnosis, and 36% were currently drinkers.

But stroke risk went up about 30% with “moderate” current alcohol intake, compared with no intake, and by more than 40% for current drinkers reporting “heavy” alcohol intake, researchers found in an adjusted analysis.

However, abstainers who had mild to moderate alcohol-intake levels before their AFib diagnosis “had a similar risk of ischemic stroke as nondrinkers,” write the authors, led by So-Ryoung Lee, MD, PhD, and colleagues, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, in their report published June 7 in the European Heart Journal. In a secondary analysis, binge drinking was also independently associated with risk for ischemic stroke.

The findings suggest that “alcohol abstinence after the diagnosis of AFib could reduce the risk of ischemic stroke,” they conclude. “Lifestyle interventions, including attention to alcohol consumption, should be encouraged as part of a comprehensive approach in the management of patients with a new diagnosis of AFib” for lowering the risk for stroke and other clinical outcomes.

“These results are pretty comparable to those obtained in the more general population,” David Conen, MD, MPH, not connected to the analysis, told this news organization.

In the study’s population with new-onset AFib, there is an alcohol-dependent risk for stroke “that goes up with increasing alcohol intake, which is more or less similar to that found without atrial fibrillation in previous studies,” said Dr. Conen, from the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The study, “which overall I think is very well done,” he said, is noteworthy for also suggesting that binge drinking, which was scrutinized in a secondary analysis, appeared independently to worsen the risk for stroke in its AFib population.

Dr. Conen said the observed 1% overall risk for stroke was very similar to the rate he and his colleagues saw in a recent combined analysis of two European cohorts with AFib that was usually longer standing; the median was 3 years. That analysis, in contrast, showed no significant association between increasing levels of alcohol intake and risk for stroke or systemic embolism.

However, “our confidence limits did not exclude the possibility of a small to moderate association,” he said. Given that, and the current study from Korea, there might indeed be “a weak association between alcohol consumption and stroke” in patients with AFib.

“Their results are just more precise because of the larger sample size. That’s why they were able to show those associations,” said Dr. Conen, who was senior author on the earlier report, which covered a pooled analysis of 3,852 patients with AFib in the BEAT-AF and SWISS-AF cohort studies. It was published January 25 in CMAJ, with lead author Philipp Reddiess, MD, Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel, Switzerland.

The two published studies contrast in other ways that are worth noting and together suggest the stroke rate might have been 1% in both by chance, Dr. Conen said. “The populations were pretty different.”

In the earlier study, for example, the overwhelmingly European patients had more comorbidities and had been in AFib for much longer; their mean age was 71 years; and 84% were on oral anticoagulation (OAC).

In contrast, the Korean cohort averaged 61 years in age and only about 24% were taking oral anticoagulants. Given their distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc scores and mean score of 2.3, more than twice as many should have been on OAC, Dr. Conen speculated. “Even if you take into account that some patients may have contraindications, this is clearly an underanticoagulated population.”

The European cohort might have been “a little bit more representative because atrial fibrillation is a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Conen said, but “the Korean paper has the advantage of being a population-based study.”

It involved 97,869 patients from a Korean national data base who were newly diagnosed with AFib from 2010 to 2016. Of the total, 49,781 (51%) were continuously nondrinkers before and after their diagnosis; 12,789 (13%) abstained from alcohol only after their AFib diagnosis; and 35,299 (36%) were drinkers during the follow-up, either because they continued to drink or newly started after their diagnosis.

Of the cohort, 3,120 were diagnosed with new ischemic stroke over a follow-up of 310,926 person-years, for a rate of 1 per 100 person-years.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke over a 5-year follow-up, compared with nondrinkers, was:

- 1.127 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.266) among abstainers

- 1.280 (95% CI, 1.166-1.405) for current drinkers

The corresponding HR, compared with current drinkers, was:

- 0.781 (95% CI, 0.712-0.858) for nondrinkers

- 0.880 (95% CI, 0.782-0.990) among abstainers

No significant interactions with ischemic stroke risk were observed in groups by sex, age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, or smoking status. The risk rose consistently with current drinking levels.

The overall stroke rate of 1% per year is “very low,” and “the absolute differences are small, even though there is a clear significant trend from nondrinking to drinking,” Dr. Conen said.

However, “the difference becomes more sizable when you compare heavy drinking to abstinence.”

Dr. Lee reports no conflicts of interest; disclosures for the other authors are in their report. Dr. Conen reports receiving speaker fees from Servier Canada; disclosures for the other authors are in their report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There’s abundant evidence linking higher alcohol intake levels to greater stroke risk and, separately, increasing risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). Less settled is whether moderate to heavy drinking worsens the risk for stroke in patients already in AFib and whether giving up alcohol can attenuate that risk. A new observational study suggests the answer to both questions is yes.

The risk for ischemic stroke was only around 1% over about 5 years in a Korean nationwide cohort of almost 98,000 patients with new-onset AFib. About half the patients followed were nondrinkers, as they had been before the study, 13% became abstinent soon after their AFib diagnosis, and 36% were currently drinkers.

But stroke risk went up about 30% with “moderate” current alcohol intake, compared with no intake, and by more than 40% for current drinkers reporting “heavy” alcohol intake, researchers found in an adjusted analysis.

However, abstainers who had mild to moderate alcohol-intake levels before their AFib diagnosis “had a similar risk of ischemic stroke as nondrinkers,” write the authors, led by So-Ryoung Lee, MD, PhD, and colleagues, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, in their report published June 7 in the European Heart Journal. In a secondary analysis, binge drinking was also independently associated with risk for ischemic stroke.

The findings suggest that “alcohol abstinence after the diagnosis of AFib could reduce the risk of ischemic stroke,” they conclude. “Lifestyle interventions, including attention to alcohol consumption, should be encouraged as part of a comprehensive approach in the management of patients with a new diagnosis of AFib” for lowering the risk for stroke and other clinical outcomes.

“These results are pretty comparable to those obtained in the more general population,” David Conen, MD, MPH, not connected to the analysis, told this news organization.

In the study’s population with new-onset AFib, there is an alcohol-dependent risk for stroke “that goes up with increasing alcohol intake, which is more or less similar to that found without atrial fibrillation in previous studies,” said Dr. Conen, from the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The study, “which overall I think is very well done,” he said, is noteworthy for also suggesting that binge drinking, which was scrutinized in a secondary analysis, appeared independently to worsen the risk for stroke in its AFib population.

Dr. Conen said the observed 1% overall risk for stroke was very similar to the rate he and his colleagues saw in a recent combined analysis of two European cohorts with AFib that was usually longer standing; the median was 3 years. That analysis, in contrast, showed no significant association between increasing levels of alcohol intake and risk for stroke or systemic embolism.

However, “our confidence limits did not exclude the possibility of a small to moderate association,” he said. Given that, and the current study from Korea, there might indeed be “a weak association between alcohol consumption and stroke” in patients with AFib.

“Their results are just more precise because of the larger sample size. That’s why they were able to show those associations,” said Dr. Conen, who was senior author on the earlier report, which covered a pooled analysis of 3,852 patients with AFib in the BEAT-AF and SWISS-AF cohort studies. It was published January 25 in CMAJ, with lead author Philipp Reddiess, MD, Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel, Switzerland.

The two published studies contrast in other ways that are worth noting and together suggest the stroke rate might have been 1% in both by chance, Dr. Conen said. “The populations were pretty different.”

In the earlier study, for example, the overwhelmingly European patients had more comorbidities and had been in AFib for much longer; their mean age was 71 years; and 84% were on oral anticoagulation (OAC).

In contrast, the Korean cohort averaged 61 years in age and only about 24% were taking oral anticoagulants. Given their distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc scores and mean score of 2.3, more than twice as many should have been on OAC, Dr. Conen speculated. “Even if you take into account that some patients may have contraindications, this is clearly an underanticoagulated population.”

The European cohort might have been “a little bit more representative because atrial fibrillation is a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Conen said, but “the Korean paper has the advantage of being a population-based study.”

It involved 97,869 patients from a Korean national data base who were newly diagnosed with AFib from 2010 to 2016. Of the total, 49,781 (51%) were continuously nondrinkers before and after their diagnosis; 12,789 (13%) abstained from alcohol only after their AFib diagnosis; and 35,299 (36%) were drinkers during the follow-up, either because they continued to drink or newly started after their diagnosis.

Of the cohort, 3,120 were diagnosed with new ischemic stroke over a follow-up of 310,926 person-years, for a rate of 1 per 100 person-years.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke over a 5-year follow-up, compared with nondrinkers, was:

- 1.127 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.266) among abstainers

- 1.280 (95% CI, 1.166-1.405) for current drinkers

The corresponding HR, compared with current drinkers, was:

- 0.781 (95% CI, 0.712-0.858) for nondrinkers

- 0.880 (95% CI, 0.782-0.990) among abstainers

No significant interactions with ischemic stroke risk were observed in groups by sex, age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, or smoking status. The risk rose consistently with current drinking levels.

The overall stroke rate of 1% per year is “very low,” and “the absolute differences are small, even though there is a clear significant trend from nondrinking to drinking,” Dr. Conen said.

However, “the difference becomes more sizable when you compare heavy drinking to abstinence.”

Dr. Lee reports no conflicts of interest; disclosures for the other authors are in their report. Dr. Conen reports receiving speaker fees from Servier Canada; disclosures for the other authors are in their report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An overlooked cause of palpitations

Your article, “Is an underlying cardiac condition causing your patient’s palpitations?” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:60-68), listed a number of causes of palpitations in the table on page 62. However, 1 cause was noticeably missing: underlying genetic disorders, such as amyloidosis. Genetic disorders can affect the cardiac muscle and lead to increased rates of both cardiac arrhythmias and palpitations.

I recently treated a 43-year-old man who presented with shortness of breath and presyncopal episodes; his medical history included anxiety and gastritis. He previously had undergone a cervical spine fusion and was postoperatively given a diagnosis of bigeminy and frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). An echocardiogram was ordered and came back negative, while a Holter monitor showed PVCs > 30%. Genetic testing was performed only after the family history offered some clues. The diagnosis was hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Now, he is awaiting cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to determine whether muscle or pericardium has been affected.

When I discussed the findings with the patient, he wisely stated, “Perhaps it is more common than studies show if patients are not normally tested until elderly or hospitalized.” This resonated with me when I considered that routine lab work done in an office would miss amyloidosis. This definitely reinforced my philosophy to always listen to the patient and take symptoms seriously, as sometimes we just haven’t figured out the true diagnosis yet.

Your article, “Is an underlying cardiac condition causing your patient’s palpitations?” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:60-68), listed a number of causes of palpitations in the table on page 62. However, 1 cause was noticeably missing: underlying genetic disorders, such as amyloidosis. Genetic disorders can affect the cardiac muscle and lead to increased rates of both cardiac arrhythmias and palpitations.

I recently treated a 43-year-old man who presented with shortness of breath and presyncopal episodes; his medical history included anxiety and gastritis. He previously had undergone a cervical spine fusion and was postoperatively given a diagnosis of bigeminy and frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). An echocardiogram was ordered and came back negative, while a Holter monitor showed PVCs > 30%. Genetic testing was performed only after the family history offered some clues. The diagnosis was hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Now, he is awaiting cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to determine whether muscle or pericardium has been affected.

When I discussed the findings with the patient, he wisely stated, “Perhaps it is more common than studies show if patients are not normally tested until elderly or hospitalized.” This resonated with me when I considered that routine lab work done in an office would miss amyloidosis. This definitely reinforced my philosophy to always listen to the patient and take symptoms seriously, as sometimes we just haven’t figured out the true diagnosis yet.

Your article, “Is an underlying cardiac condition causing your patient’s palpitations?” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:60-68), listed a number of causes of palpitations in the table on page 62. However, 1 cause was noticeably missing: underlying genetic disorders, such as amyloidosis. Genetic disorders can affect the cardiac muscle and lead to increased rates of both cardiac arrhythmias and palpitations.

I recently treated a 43-year-old man who presented with shortness of breath and presyncopal episodes; his medical history included anxiety and gastritis. He previously had undergone a cervical spine fusion and was postoperatively given a diagnosis of bigeminy and frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). An echocardiogram was ordered and came back negative, while a Holter monitor showed PVCs > 30%. Genetic testing was performed only after the family history offered some clues. The diagnosis was hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Now, he is awaiting cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to determine whether muscle or pericardium has been affected.

When I discussed the findings with the patient, he wisely stated, “Perhaps it is more common than studies show if patients are not normally tested until elderly or hospitalized.” This resonated with me when I considered that routine lab work done in an office would miss amyloidosis. This definitely reinforced my philosophy to always listen to the patient and take symptoms seriously, as sometimes we just haven’t figured out the true diagnosis yet.

To screen or not to screen children for hypertension?

In this issue of JFP, Smith et al recommend following guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics to annually screen children for hypertension (see page 220). This recommendation appears to be at odds with the recent US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) statement that concluded there is insufficient evidence for screening children and adolescents for hypertension. But an “I” recommendation from the USPSTF is not the same as a “D” recommendation. “D” means don’t do it, because the evidence indicates that the harms outweigh the benefits. “I” means we don’t have enough evidence to weigh the harms and benefits, so it is up to you and your patients to decide what to do.

So whose recommendations should we follow?

Our decision should be based on a thorough understanding of the evidence, and that evidence is well summarized in the recent USPSTF report.1 The reviewers found no studies that evaluated the benefits and harms of screening children and adolescents for hypertension and no studies evaluating disease outcomes from treating hypertension in these patients.

There is, however, an association between elevated blood pressure in childhood and outcomes such as left ventricular hypertrophy and carotid intimal thickness.2 Some physicians contend that these “disease-oriented outcomes” are sufficient reason to identify and treat hypertension in children and adolescents.3 The USPSTF, however, requires a higher level of evidence that includes patient-oriented outcomes, such as a lower risk of congestive heart failure, renal failure, or death, before recommending treatment. Physicians and patients have to choose what level of evidence is sufficient to take action.

Dr. Smith comments: “As noted in their report, the USPSTF acknowledges that observational studies indicate an association between hypertension in childhood and hypertension in adulthood, but there have been no randomized trials to determine if treating hypertension in children and adolescents reduces risk of cardiovascular events. Although it is a cohort study, not a randomized trial, the ongoing i3C Consortium Outcomes Study4 may provide better information to guide decision-making for children and adolescents with elevated blood pressure.”

What we can all agree on is that, when hypertension is identified in a child or adolescent, it is important to determine if there is a treatable cause of elevated blood pressure such as coarctation of the aorta or renal disease. It is also important to address risk factors for elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, such as obesity, poor dietary habits, and smoking. The treatment is lifestyle modification with diet, exercise, and smoking cessation.

- USPSTF: High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

- Yang L, Magnussen CG, Yang L, et al. Elevated blood pressure in childhood or adolescence and cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2020;75:948–955. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.14168

- Falkner B, Lurbe E. The USPSTF call to inaction on blood pressure screening in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36:1327-1329. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-04926-y

- Sinaiko AR, Jacobs DR Jr, Woo JG, et al. The International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort (i3C) consortium outcomes study of childhood cardiovascular risk factors and adult cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: Design and recruitment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;69:55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.04.009

In this issue of JFP, Smith et al recommend following guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics to annually screen children for hypertension (see page 220). This recommendation appears to be at odds with the recent US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) statement that concluded there is insufficient evidence for screening children and adolescents for hypertension. But an “I” recommendation from the USPSTF is not the same as a “D” recommendation. “D” means don’t do it, because the evidence indicates that the harms outweigh the benefits. “I” means we don’t have enough evidence to weigh the harms and benefits, so it is up to you and your patients to decide what to do.

So whose recommendations should we follow?

Our decision should be based on a thorough understanding of the evidence, and that evidence is well summarized in the recent USPSTF report.1 The reviewers found no studies that evaluated the benefits and harms of screening children and adolescents for hypertension and no studies evaluating disease outcomes from treating hypertension in these patients.

There is, however, an association between elevated blood pressure in childhood and outcomes such as left ventricular hypertrophy and carotid intimal thickness.2 Some physicians contend that these “disease-oriented outcomes” are sufficient reason to identify and treat hypertension in children and adolescents.3 The USPSTF, however, requires a higher level of evidence that includes patient-oriented outcomes, such as a lower risk of congestive heart failure, renal failure, or death, before recommending treatment. Physicians and patients have to choose what level of evidence is sufficient to take action.

Dr. Smith comments: “As noted in their report, the USPSTF acknowledges that observational studies indicate an association between hypertension in childhood and hypertension in adulthood, but there have been no randomized trials to determine if treating hypertension in children and adolescents reduces risk of cardiovascular events. Although it is a cohort study, not a randomized trial, the ongoing i3C Consortium Outcomes Study4 may provide better information to guide decision-making for children and adolescents with elevated blood pressure.”

What we can all agree on is that, when hypertension is identified in a child or adolescent, it is important to determine if there is a treatable cause of elevated blood pressure such as coarctation of the aorta or renal disease. It is also important to address risk factors for elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, such as obesity, poor dietary habits, and smoking. The treatment is lifestyle modification with diet, exercise, and smoking cessation.

In this issue of JFP, Smith et al recommend following guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics to annually screen children for hypertension (see page 220). This recommendation appears to be at odds with the recent US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) statement that concluded there is insufficient evidence for screening children and adolescents for hypertension. But an “I” recommendation from the USPSTF is not the same as a “D” recommendation. “D” means don’t do it, because the evidence indicates that the harms outweigh the benefits. “I” means we don’t have enough evidence to weigh the harms and benefits, so it is up to you and your patients to decide what to do.

So whose recommendations should we follow?

Our decision should be based on a thorough understanding of the evidence, and that evidence is well summarized in the recent USPSTF report.1 The reviewers found no studies that evaluated the benefits and harms of screening children and adolescents for hypertension and no studies evaluating disease outcomes from treating hypertension in these patients.

There is, however, an association between elevated blood pressure in childhood and outcomes such as left ventricular hypertrophy and carotid intimal thickness.2 Some physicians contend that these “disease-oriented outcomes” are sufficient reason to identify and treat hypertension in children and adolescents.3 The USPSTF, however, requires a higher level of evidence that includes patient-oriented outcomes, such as a lower risk of congestive heart failure, renal failure, or death, before recommending treatment. Physicians and patients have to choose what level of evidence is sufficient to take action.

Dr. Smith comments: “As noted in their report, the USPSTF acknowledges that observational studies indicate an association between hypertension in childhood and hypertension in adulthood, but there have been no randomized trials to determine if treating hypertension in children and adolescents reduces risk of cardiovascular events. Although it is a cohort study, not a randomized trial, the ongoing i3C Consortium Outcomes Study4 may provide better information to guide decision-making for children and adolescents with elevated blood pressure.”

What we can all agree on is that, when hypertension is identified in a child or adolescent, it is important to determine if there is a treatable cause of elevated blood pressure such as coarctation of the aorta or renal disease. It is also important to address risk factors for elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, such as obesity, poor dietary habits, and smoking. The treatment is lifestyle modification with diet, exercise, and smoking cessation.

- USPSTF: High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

- Yang L, Magnussen CG, Yang L, et al. Elevated blood pressure in childhood or adolescence and cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2020;75:948–955. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.14168

- Falkner B, Lurbe E. The USPSTF call to inaction on blood pressure screening in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36:1327-1329. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-04926-y

- Sinaiko AR, Jacobs DR Jr, Woo JG, et al. The International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort (i3C) consortium outcomes study of childhood cardiovascular risk factors and adult cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: Design and recruitment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;69:55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.04.009

- USPSTF: High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

- Yang L, Magnussen CG, Yang L, et al. Elevated blood pressure in childhood or adolescence and cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2020;75:948–955. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.14168

- Falkner B, Lurbe E. The USPSTF call to inaction on blood pressure screening in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36:1327-1329. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-04926-y

- Sinaiko AR, Jacobs DR Jr, Woo JG, et al. The International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort (i3C) consortium outcomes study of childhood cardiovascular risk factors and adult cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: Design and recruitment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;69:55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.04.009

Treating sleep apnea lowers MI and stroke risk

particularly for patients with moderate to severe OSA and those who are more adherent to CPAP therapy, a new study suggests.

“Most clinical trials on the effect of CPAP on CV diseases to date have focused on secondary CV prevention. This study contributes another piece of evidence about the role of CPAP therapy to prevent CV diseases,” said Diego R. Mazzotti, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

“Our study, while observational, suggests that clinical trials focused on understanding how to sustain long-term CPAP adherence in obstructive sleep apnea patients are necessary and could be critical for optimizing comorbidity risk reduction,” Dr. Mazzotti said.

The study was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Good adherence important

The researchers analyzed the electronic health records of adults referred for a sleep study through the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health system. The sample included 11,145 adults without OSA, 13,898 with OSA who used CPAP, and 20,884 adults with OSA who did not use CPAP. None of them had CV disease at baseline. Median follow-up was 262 days.

The primary outcome was first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina, heart failure, or death caused by CV disease.

In adjusted models, adults with moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index ≥15) who did not use CPAP were 71% more likely than those without OSA to have a first CV event (hazard ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.11-2.64). However, the risk for a CV event during follow-up was 32% lower among OSA patients with any CPAP use (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50-0.93; P = .016).

The effect was mostly driven by those who used CPAP for at least 4 hours per night (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.95). This association was stronger for those with moderate to severe OSA (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.81).

“This study highlights the importance of long-term management of CPAP therapy in patients with moderate-severe OSA,” Dr. Mazzotti said in an interview.

“It suggests that maintaining good CPAP adherence might be beneficial for cardiovascular health, besides the already established benefits on quality of life, sleepiness, and other cardiometabolic functions,” he said.

Dr. Mazzotti said several mechanisms might explain the association between CPAP use and lower risk for CV events. “CPAP treats OSA by preventing respiratory pauses that occur during sleep, therefore preventing arousals, sleep fragmentation, and decreases in blood oxygen. These improved cardiorespiratory functions can be beneficial to avoid certain molecular changes that are known to contribute to cardiovascular risk, such as oxidative stress and inflammation,” he explained.

“However, specific studies fully understanding these mechanisms are necessary,” Dr. Mazzotti added.

In a comment, Nitun Verma, MD, a spokesperson for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, said that “the frequent decreases in oxygen levels and fragmented sleep from apnea are associated with cardiovascular disorders. We know this from multiple studies. This, however, was a large study and strengthens the association between improving apnea and reduced serious cardiovascular events.”

Funding for the study was provided by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation and the American Heart Association. Dr. Mazzotti and Dr. Verma disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

particularly for patients with moderate to severe OSA and those who are more adherent to CPAP therapy, a new study suggests.

“Most clinical trials on the effect of CPAP on CV diseases to date have focused on secondary CV prevention. This study contributes another piece of evidence about the role of CPAP therapy to prevent CV diseases,” said Diego R. Mazzotti, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

“Our study, while observational, suggests that clinical trials focused on understanding how to sustain long-term CPAP adherence in obstructive sleep apnea patients are necessary and could be critical for optimizing comorbidity risk reduction,” Dr. Mazzotti said.

The study was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Good adherence important

The researchers analyzed the electronic health records of adults referred for a sleep study through the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health system. The sample included 11,145 adults without OSA, 13,898 with OSA who used CPAP, and 20,884 adults with OSA who did not use CPAP. None of them had CV disease at baseline. Median follow-up was 262 days.

The primary outcome was first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina, heart failure, or death caused by CV disease.

In adjusted models, adults with moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index ≥15) who did not use CPAP were 71% more likely than those without OSA to have a first CV event (hazard ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.11-2.64). However, the risk for a CV event during follow-up was 32% lower among OSA patients with any CPAP use (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50-0.93; P = .016).

The effect was mostly driven by those who used CPAP for at least 4 hours per night (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.95). This association was stronger for those with moderate to severe OSA (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.81).

“This study highlights the importance of long-term management of CPAP therapy in patients with moderate-severe OSA,” Dr. Mazzotti said in an interview.

“It suggests that maintaining good CPAP adherence might be beneficial for cardiovascular health, besides the already established benefits on quality of life, sleepiness, and other cardiometabolic functions,” he said.

Dr. Mazzotti said several mechanisms might explain the association between CPAP use and lower risk for CV events. “CPAP treats OSA by preventing respiratory pauses that occur during sleep, therefore preventing arousals, sleep fragmentation, and decreases in blood oxygen. These improved cardiorespiratory functions can be beneficial to avoid certain molecular changes that are known to contribute to cardiovascular risk, such as oxidative stress and inflammation,” he explained.

“However, specific studies fully understanding these mechanisms are necessary,” Dr. Mazzotti added.

In a comment, Nitun Verma, MD, a spokesperson for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, said that “the frequent decreases in oxygen levels and fragmented sleep from apnea are associated with cardiovascular disorders. We know this from multiple studies. This, however, was a large study and strengthens the association between improving apnea and reduced serious cardiovascular events.”

Funding for the study was provided by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation and the American Heart Association. Dr. Mazzotti and Dr. Verma disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

particularly for patients with moderate to severe OSA and those who are more adherent to CPAP therapy, a new study suggests.

“Most clinical trials on the effect of CPAP on CV diseases to date have focused on secondary CV prevention. This study contributes another piece of evidence about the role of CPAP therapy to prevent CV diseases,” said Diego R. Mazzotti, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

“Our study, while observational, suggests that clinical trials focused on understanding how to sustain long-term CPAP adherence in obstructive sleep apnea patients are necessary and could be critical for optimizing comorbidity risk reduction,” Dr. Mazzotti said.

The study was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Good adherence important

The researchers analyzed the electronic health records of adults referred for a sleep study through the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health system. The sample included 11,145 adults without OSA, 13,898 with OSA who used CPAP, and 20,884 adults with OSA who did not use CPAP. None of them had CV disease at baseline. Median follow-up was 262 days.

The primary outcome was first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina, heart failure, or death caused by CV disease.

In adjusted models, adults with moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index ≥15) who did not use CPAP were 71% more likely than those without OSA to have a first CV event (hazard ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.11-2.64). However, the risk for a CV event during follow-up was 32% lower among OSA patients with any CPAP use (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50-0.93; P = .016).

The effect was mostly driven by those who used CPAP for at least 4 hours per night (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.95). This association was stronger for those with moderate to severe OSA (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.81).

“This study highlights the importance of long-term management of CPAP therapy in patients with moderate-severe OSA,” Dr. Mazzotti said in an interview.

“It suggests that maintaining good CPAP adherence might be beneficial for cardiovascular health, besides the already established benefits on quality of life, sleepiness, and other cardiometabolic functions,” he said.

Dr. Mazzotti said several mechanisms might explain the association between CPAP use and lower risk for CV events. “CPAP treats OSA by preventing respiratory pauses that occur during sleep, therefore preventing arousals, sleep fragmentation, and decreases in blood oxygen. These improved cardiorespiratory functions can be beneficial to avoid certain molecular changes that are known to contribute to cardiovascular risk, such as oxidative stress and inflammation,” he explained.

“However, specific studies fully understanding these mechanisms are necessary,” Dr. Mazzotti added.

In a comment, Nitun Verma, MD, a spokesperson for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, said that “the frequent decreases in oxygen levels and fragmented sleep from apnea are associated with cardiovascular disorders. We know this from multiple studies. This, however, was a large study and strengthens the association between improving apnea and reduced serious cardiovascular events.”

Funding for the study was provided by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation and the American Heart Association. Dr. Mazzotti and Dr. Verma disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SLEEP 2021

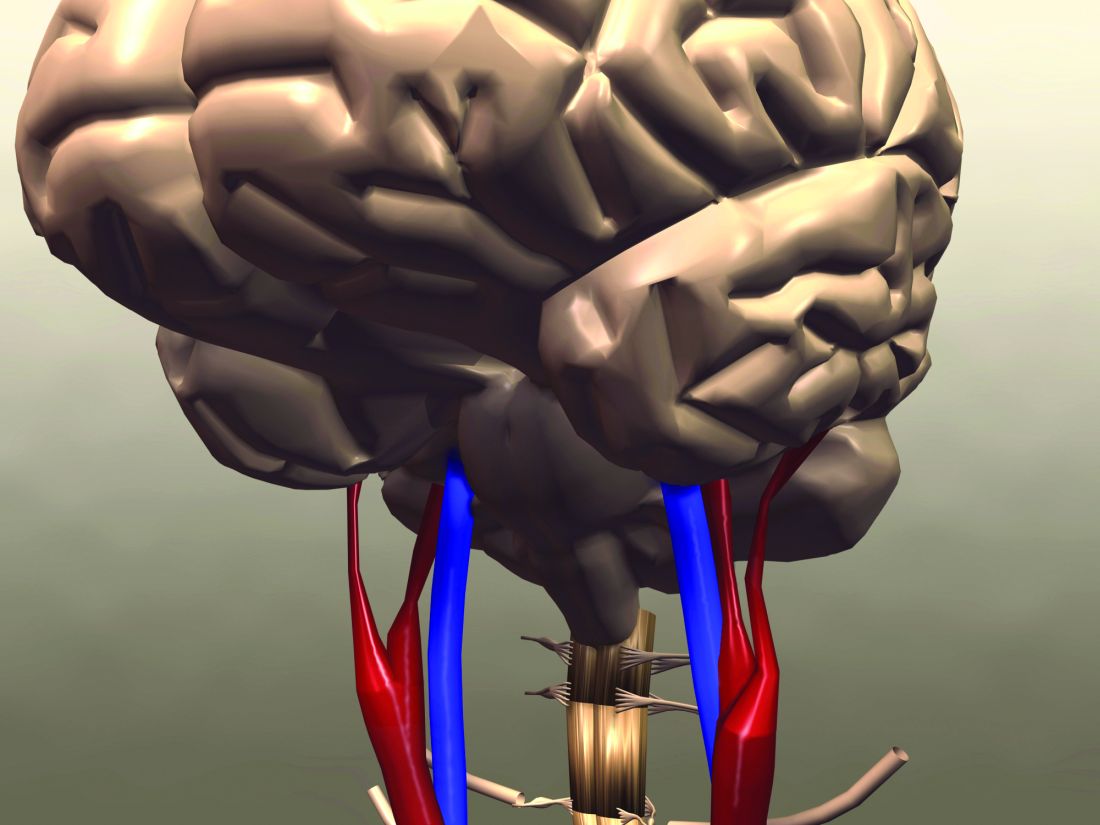

Memory benefit seen with antihypertensives crossing blood-brain barrier

Over a 3-year period, cognitively normal older adults taking BBB-crossing antihypertensives demonstrated superior verbal memory, compared with similar individuals receiving non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, reported lead author Jean K. Ho, PhD, of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

According to the investigators, the findings add color to a known link between hypertension and neurologic degeneration, and may aid the search for new therapeutic targets.

“Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, possibly through its effects on both cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Ho and colleagues wrote in Hypertension. “Studies of antihypertensive treatments have reported possible salutary effects on cognition and cerebrovascular disease, as well as Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology.”

In a previous study, individuals younger than 75 years exposed to antihypertensives had an 8% decreased risk of dementia per year of use, while another trial showed that intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%.

“Despite these encouraging findings ... larger meta-analytic studies have been hampered by the fact that pharmacokinetic properties are typically not considered in existing studies or routine clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Ho and colleagues. “The present study sought to fill this gap [in that it was] a large and longitudinal meta-analytic study of existing data recoded to assess the effects of BBB-crossing potential in renin-angiotensin system [RAS] treatments among hypertensive adults.”

Methods and results

The meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective observational studies. The researchers assessed data on 12,849 individuals from 14 cohorts that received either BBB-crossing or non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives.

The BBB-crossing properties of RAS treatments were identified by a literature review. Of ACE inhibitors, captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, and trandolapril were classified as BBB crossing, and benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, and quinapril were classified as non–BBB-crossing. Of ARBs, telmisartan and candesartan were considered BBB-crossing, and olmesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, and losartan were tagged as non–BBB-crossing.

Cognition was assessed via the following seven domains: executive function, attention, verbal memory learning, language, mental status, recall, and processing speed.

Compared with individuals taking non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, those taking BBB-crossing agents had significantly superior verbal memory (recall), with a maximum effect size of 0.07 (P = .03).

According to the investigators, this finding was particularly noteworthy, as the BBB-crossing group had relatively higher vascular risk burden and lower mean education level.

“These differences make it all the more remarkable that the BBB-crossing group displayed better memory ability over time despite these cognitive disadvantages,” the investigators wrote.

Still, not all the findings favored BBB-crossing agents. Individuals in the BBB-crossing group had relatively inferior attention ability, with a minimum effect size of –0.17 (P = .02).

The other cognitive measures were not significantly different between groups.

Clinicians may consider findings after accounting for other factors

Principal investigator Daniel A. Nation, PhD, associate professor of psychological science and a faculty member of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, suggested that the small difference in verbal memory between groups could be clinically significant over a longer period of time.

“Although the overall effect size was pretty small, if you look at how long it would take for someone [with dementia] to progress over many years of decline, it would actually end up being a pretty big effect,” Dr. Nation said in an interview. “Small effect sizes could actually end up preventing a lot of cases of dementia,” he added.

The conflicting results in the BBB-crossing group – better verbal memory but worse attention ability – were “surprising,” he noted.

“I sort of didn’t believe it at first,” Dr. Nation said, “because the memory finding is sort of replication – we’d observed the same exact effect on memory in a smaller sample in another study. ... The attention [finding], going another way, was a new thing.”

Dr. Nation suggested that the intergroup differences in attention ability may stem from idiosyncrasies of the tests used to measure that domain, which can be impacted by cardiovascular or brain vascular disease. Or it could be caused by something else entirely, he said, noting that further investigation is needed.

He added that the improvements in verbal memory within the BBB-crossing group could be caused by direct effects on the brain. He pointed out that certain ACE polymorphisms have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and those same polymorphisms, in animal models, lead to neurodegeneration, with reversal possible through administration of ACE inhibitors.

“It could be that what we’re observing has nothing really to do with blood pressure,” Dr. Nation explained. “This could be a neuronal effect on learning memory systems.”

He went on to suggest that clinicians may consider these findings when selecting antihypertensive agents for their patients, with the caveat that all other prescribing factors have already been taking to account.

“In the event that you’re going to give an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker anyway, and it ends up being a somewhat arbitrary decision in terms of which specific drug you’re going to give, then perhaps this is a piece of information you would take into account – that one gets in the brain and one doesn’t – in somebody at risk for cognitive decline,” Dr. Nation said.

Exact mechanisms of action unknown

Hélène Girouard, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and physiology at the University of Montreal, said in an interview that the findings are “of considerable importance, knowing that brain alterations could begin as much as 30 years before manifestation of dementia.”

Since 2003, Dr. Girouard has been studying the cognitive effects of antihypertensive medications. She noted that previous studies involving rodents “have shown beneficial effects [of BBB-crossing antihypertensive drugs] on cognition independent of their effects on blood pressure.”

The drugs’ exact mechanisms of action, however, remain elusive, according to Dr. Girouard, who offered several possible explanations, including amelioration of BBB disruption, brain inflammation, cerebral blood flow dysregulation, cholinergic dysfunction, and neurologic deficits. “Whether these mechanisms may explain Ho and colleagues’ observations remains to be established,” she added.

Andrea L. Schneider, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, applauded the study, but ultimately suggested that more research is needed to impact clinical decision-making.

“The results of this important and well-done study suggest that further investigation into targeted mechanism-based approaches to selecting hypertension treatment agents, with a specific focus on cognitive outcomes, is warranted,” Dr. Schneider said in an interview. “Before changing clinical practice, further work is necessary to disentangle contributions of medication mechanism, comorbid vascular risk factors, and achieved blood pressure reduction, among others.”

The investigators disclosed support from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Waksman Foundation of Japan, and others. The interviewees reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Over a 3-year period, cognitively normal older adults taking BBB-crossing antihypertensives demonstrated superior verbal memory, compared with similar individuals receiving non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, reported lead author Jean K. Ho, PhD, of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

According to the investigators, the findings add color to a known link between hypertension and neurologic degeneration, and may aid the search for new therapeutic targets.

“Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, possibly through its effects on both cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Ho and colleagues wrote in Hypertension. “Studies of antihypertensive treatments have reported possible salutary effects on cognition and cerebrovascular disease, as well as Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology.”

In a previous study, individuals younger than 75 years exposed to antihypertensives had an 8% decreased risk of dementia per year of use, while another trial showed that intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%.

“Despite these encouraging findings ... larger meta-analytic studies have been hampered by the fact that pharmacokinetic properties are typically not considered in existing studies or routine clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Ho and colleagues. “The present study sought to fill this gap [in that it was] a large and longitudinal meta-analytic study of existing data recoded to assess the effects of BBB-crossing potential in renin-angiotensin system [RAS] treatments among hypertensive adults.”

Methods and results

The meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective observational studies. The researchers assessed data on 12,849 individuals from 14 cohorts that received either BBB-crossing or non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives.

The BBB-crossing properties of RAS treatments were identified by a literature review. Of ACE inhibitors, captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, and trandolapril were classified as BBB crossing, and benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, and quinapril were classified as non–BBB-crossing. Of ARBs, telmisartan and candesartan were considered BBB-crossing, and olmesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, and losartan were tagged as non–BBB-crossing.

Cognition was assessed via the following seven domains: executive function, attention, verbal memory learning, language, mental status, recall, and processing speed.

Compared with individuals taking non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, those taking BBB-crossing agents had significantly superior verbal memory (recall), with a maximum effect size of 0.07 (P = .03).

According to the investigators, this finding was particularly noteworthy, as the BBB-crossing group had relatively higher vascular risk burden and lower mean education level.

“These differences make it all the more remarkable that the BBB-crossing group displayed better memory ability over time despite these cognitive disadvantages,” the investigators wrote.

Still, not all the findings favored BBB-crossing agents. Individuals in the BBB-crossing group had relatively inferior attention ability, with a minimum effect size of –0.17 (P = .02).

The other cognitive measures were not significantly different between groups.

Clinicians may consider findings after accounting for other factors

Principal investigator Daniel A. Nation, PhD, associate professor of psychological science and a faculty member of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, suggested that the small difference in verbal memory between groups could be clinically significant over a longer period of time.

“Although the overall effect size was pretty small, if you look at how long it would take for someone [with dementia] to progress over many years of decline, it would actually end up being a pretty big effect,” Dr. Nation said in an interview. “Small effect sizes could actually end up preventing a lot of cases of dementia,” he added.

The conflicting results in the BBB-crossing group – better verbal memory but worse attention ability – were “surprising,” he noted.

“I sort of didn’t believe it at first,” Dr. Nation said, “because the memory finding is sort of replication – we’d observed the same exact effect on memory in a smaller sample in another study. ... The attention [finding], going another way, was a new thing.”

Dr. Nation suggested that the intergroup differences in attention ability may stem from idiosyncrasies of the tests used to measure that domain, which can be impacted by cardiovascular or brain vascular disease. Or it could be caused by something else entirely, he said, noting that further investigation is needed.

He added that the improvements in verbal memory within the BBB-crossing group could be caused by direct effects on the brain. He pointed out that certain ACE polymorphisms have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and those same polymorphisms, in animal models, lead to neurodegeneration, with reversal possible through administration of ACE inhibitors.

“It could be that what we’re observing has nothing really to do with blood pressure,” Dr. Nation explained. “This could be a neuronal effect on learning memory systems.”

He went on to suggest that clinicians may consider these findings when selecting antihypertensive agents for their patients, with the caveat that all other prescribing factors have already been taking to account.

“In the event that you’re going to give an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker anyway, and it ends up being a somewhat arbitrary decision in terms of which specific drug you’re going to give, then perhaps this is a piece of information you would take into account – that one gets in the brain and one doesn’t – in somebody at risk for cognitive decline,” Dr. Nation said.

Exact mechanisms of action unknown

Hélène Girouard, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and physiology at the University of Montreal, said in an interview that the findings are “of considerable importance, knowing that brain alterations could begin as much as 30 years before manifestation of dementia.”

Since 2003, Dr. Girouard has been studying the cognitive effects of antihypertensive medications. She noted that previous studies involving rodents “have shown beneficial effects [of BBB-crossing antihypertensive drugs] on cognition independent of their effects on blood pressure.”

The drugs’ exact mechanisms of action, however, remain elusive, according to Dr. Girouard, who offered several possible explanations, including amelioration of BBB disruption, brain inflammation, cerebral blood flow dysregulation, cholinergic dysfunction, and neurologic deficits. “Whether these mechanisms may explain Ho and colleagues’ observations remains to be established,” she added.

Andrea L. Schneider, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, applauded the study, but ultimately suggested that more research is needed to impact clinical decision-making.

“The results of this important and well-done study suggest that further investigation into targeted mechanism-based approaches to selecting hypertension treatment agents, with a specific focus on cognitive outcomes, is warranted,” Dr. Schneider said in an interview. “Before changing clinical practice, further work is necessary to disentangle contributions of medication mechanism, comorbid vascular risk factors, and achieved blood pressure reduction, among others.”

The investigators disclosed support from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Waksman Foundation of Japan, and others. The interviewees reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Over a 3-year period, cognitively normal older adults taking BBB-crossing antihypertensives demonstrated superior verbal memory, compared with similar individuals receiving non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, reported lead author Jean K. Ho, PhD, of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

According to the investigators, the findings add color to a known link between hypertension and neurologic degeneration, and may aid the search for new therapeutic targets.

“Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, possibly through its effects on both cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Ho and colleagues wrote in Hypertension. “Studies of antihypertensive treatments have reported possible salutary effects on cognition and cerebrovascular disease, as well as Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology.”

In a previous study, individuals younger than 75 years exposed to antihypertensives had an 8% decreased risk of dementia per year of use, while another trial showed that intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%.

“Despite these encouraging findings ... larger meta-analytic studies have been hampered by the fact that pharmacokinetic properties are typically not considered in existing studies or routine clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Ho and colleagues. “The present study sought to fill this gap [in that it was] a large and longitudinal meta-analytic study of existing data recoded to assess the effects of BBB-crossing potential in renin-angiotensin system [RAS] treatments among hypertensive adults.”

Methods and results

The meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective observational studies. The researchers assessed data on 12,849 individuals from 14 cohorts that received either BBB-crossing or non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives.

The BBB-crossing properties of RAS treatments were identified by a literature review. Of ACE inhibitors, captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, and trandolapril were classified as BBB crossing, and benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, and quinapril were classified as non–BBB-crossing. Of ARBs, telmisartan and candesartan were considered BBB-crossing, and olmesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, and losartan were tagged as non–BBB-crossing.

Cognition was assessed via the following seven domains: executive function, attention, verbal memory learning, language, mental status, recall, and processing speed.

Compared with individuals taking non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, those taking BBB-crossing agents had significantly superior verbal memory (recall), with a maximum effect size of 0.07 (P = .03).

According to the investigators, this finding was particularly noteworthy, as the BBB-crossing group had relatively higher vascular risk burden and lower mean education level.

“These differences make it all the more remarkable that the BBB-crossing group displayed better memory ability over time despite these cognitive disadvantages,” the investigators wrote.

Still, not all the findings favored BBB-crossing agents. Individuals in the BBB-crossing group had relatively inferior attention ability, with a minimum effect size of –0.17 (P = .02).

The other cognitive measures were not significantly different between groups.

Clinicians may consider findings after accounting for other factors

Principal investigator Daniel A. Nation, PhD, associate professor of psychological science and a faculty member of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, suggested that the small difference in verbal memory between groups could be clinically significant over a longer period of time.

“Although the overall effect size was pretty small, if you look at how long it would take for someone [with dementia] to progress over many years of decline, it would actually end up being a pretty big effect,” Dr. Nation said in an interview. “Small effect sizes could actually end up preventing a lot of cases of dementia,” he added.

The conflicting results in the BBB-crossing group – better verbal memory but worse attention ability – were “surprising,” he noted.

“I sort of didn’t believe it at first,” Dr. Nation said, “because the memory finding is sort of replication – we’d observed the same exact effect on memory in a smaller sample in another study. ... The attention [finding], going another way, was a new thing.”

Dr. Nation suggested that the intergroup differences in attention ability may stem from idiosyncrasies of the tests used to measure that domain, which can be impacted by cardiovascular or brain vascular disease. Or it could be caused by something else entirely, he said, noting that further investigation is needed.

He added that the improvements in verbal memory within the BBB-crossing group could be caused by direct effects on the brain. He pointed out that certain ACE polymorphisms have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and those same polymorphisms, in animal models, lead to neurodegeneration, with reversal possible through administration of ACE inhibitors.

“It could be that what we’re observing has nothing really to do with blood pressure,” Dr. Nation explained. “This could be a neuronal effect on learning memory systems.”

He went on to suggest that clinicians may consider these findings when selecting antihypertensive agents for their patients, with the caveat that all other prescribing factors have already been taking to account.

“In the event that you’re going to give an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker anyway, and it ends up being a somewhat arbitrary decision in terms of which specific drug you’re going to give, then perhaps this is a piece of information you would take into account – that one gets in the brain and one doesn’t – in somebody at risk for cognitive decline,” Dr. Nation said.

Exact mechanisms of action unknown

Hélène Girouard, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and physiology at the University of Montreal, said in an interview that the findings are “of considerable importance, knowing that brain alterations could begin as much as 30 years before manifestation of dementia.”

Since 2003, Dr. Girouard has been studying the cognitive effects of antihypertensive medications. She noted that previous studies involving rodents “have shown beneficial effects [of BBB-crossing antihypertensive drugs] on cognition independent of their effects on blood pressure.”

The drugs’ exact mechanisms of action, however, remain elusive, according to Dr. Girouard, who offered several possible explanations, including amelioration of BBB disruption, brain inflammation, cerebral blood flow dysregulation, cholinergic dysfunction, and neurologic deficits. “Whether these mechanisms may explain Ho and colleagues’ observations remains to be established,” she added.

Andrea L. Schneider, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, applauded the study, but ultimately suggested that more research is needed to impact clinical decision-making.

“The results of this important and well-done study suggest that further investigation into targeted mechanism-based approaches to selecting hypertension treatment agents, with a specific focus on cognitive outcomes, is warranted,” Dr. Schneider said in an interview. “Before changing clinical practice, further work is necessary to disentangle contributions of medication mechanism, comorbid vascular risk factors, and achieved blood pressure reduction, among others.”

The investigators disclosed support from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Waksman Foundation of Japan, and others. The interviewees reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM HYPERTENSION

Stopping Empagliflozin Unmasks Heart Failure

SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to have a role in the management of heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, but there is a risk of exacerbation when discontinued.

About 40% of patients with heart failure (HF) also have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 Certain sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have benefited patients with HF.2 We report a case of a patient with T2DM who had signs and symptoms of hypervolemia after discontinuing the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin. The patient was found to have previously undiagnosed HF.

Case Presentation

A 58-year-old male presented for care at Malcolm Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainseville, Florida, diabetes clinic. The patient was diagnosed with T2DM at age 32 years. At 36 years, he was started on subcutaneous insulin injections, and was switched to insulin pump therapy in his early 40s. At the time of evaluation, the T2DM was managed using an insulin pump, metformin, and acarbose. He had been prescribed empagliflozin 10 mg several months before presentation, but the medication ran out about 1 month prior to evaluation, and additional refills were unavailable.

The patient reported a 1-month history of worsening exertional shortness of breath, decreased exercise tolerance, and lower extremity swelling. Vitals signs, including respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were within normal limits. Bibasilar crackles and bilateral 2+ pitting pedal edema were noted. The remaining examination was unrevealing. His most recent glycated hemoglobin A1c level from 1 month prior to the presentation was 6.4%.

Given the patient’s shortness of breath and evidence of fluid overload on examination, brain natriuretic peptide was obtained and was significantly elevated at 5,895 pg/mL. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed left ventricular ejection fraction < 20%. The patient was started on furosemide 40 mg, pending receipt of empagliflozin. A cardiology evaluation also was recommended.

Cardiac catheterization identified significant obstructions to the left anterior descending and left circumflex arteries. The patient underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention to these areas. Following initiation of medications and coronary revascularization, the patient reported significant symptom improvement. At the follow-up evaluation 8 weeks later, he was symptom free, and his physical examination was consistent with euvolemia.

Discussion

T2DM has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including atherosclerotic heart disease and HF. There are several theories about the relationship between T2DM and HF, though the exact pathophysiology of this relationship is unknown.3,4 One theory suggests diabetic cardiomyopathy as the cause. In patients with diabetic cardiomyopathy, there is early development of diastolic dysfunction, which eventually progresses to ventricular dysfunction. There is continued stimulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system that leads to death of cardiomyocytes, fibrosis, and remodeling, which worsens pump failure.5

SGLT2 inhibitors decrease hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, potentially reducing HF risk. SGLT2 inhibitors decrease blood glucose levels by inhibiting SGLT2 in the proximal tubule, leading to a decrease of glucose reabsorption and an increase in excretion.6,7 The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial looked at cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2DM at high risk for adverse cardiac events. There was a significant risk reduction in deaths and hospitalizations for HF in patients treated with empagliflozin.8

The EMPRISE study specifically examined empagliflozin and its effects on hospitalization for HF.2 When compared with patients treated with sitagliptin, there was a statistically significant decrease in hospitalization for HF in patients with T2DM, both with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease.

This case highlights the relationship between T2DM and HF. We also show how the use of empagliflozin may have helped manage the patient’s undiagnosed HF and how its discontinuation luckily unmasked it. Routine evaluation for HF in patients with T2DM is not done, but likely there are patients who would benefit, especially given the strong, albeit less known, association between these 2 conditions.

Further studies are needed to determine the type of patients who would benefit most from HF screening. For now, the best practice is to obtain a complete medical history that includes current and recently discontinued medications as well a thorough physical examination for signs of fluid overload and cardiovascular compromise. Patients who may have signs concerning for HF can have appropriate testing and intervention.

Conclusions

SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to have a role in the management of HF in patients with T2DM. There is a risk of exacerbation or unmasking of HF when discontinuing SGLT2 inhibitors. To our knowledge, this is the first paper describing the discovery of HF following interruption of SGLT2 inhibitor treatment. The clinician and patient should monitor for signs and symptoms of fluid overload when stopping therapy. Further research into the benefits of a more comprehensive evaluation is needed.

1. Thomas MC. Type 2 diabetes and heart failure: challenges and solutions. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016;12(3):249-255. doi:10.2174/1573403X12666160606120254

2. Patorno E, Pawar A, Franklin J, et al. Empagliflozin and the risk of heart failure hospitalization in routine clinical care: a first analysis from the EMPRISE study. Circulation. 2019;139(25):2822-2830. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039177

3. Packer M. Heart failure: the most important, preventable, and treatable cardiovascular complication of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(1):11-13. doi:10.2337/dci17-0052

4. Thrainsdottir I, Aspelund T, Thorheirsson G, et al. The association between glucose abnormalities and heart failure in the population-based Reykjavík study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):612-616. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.3.612

5. Bell D, Goncalves E. Heart failure in the patient with diabetes: epidemiology, aetiology, prognosis, therapy and the effect of glucose-lowering medications. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(6):1277-1290. doi:10.1111/dom.13652

6. Nair S, Wilding JPH. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 Inhibitors as a new treatment for diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):34-42. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0473

7. Ali A, Bain S, Hicks D, et al; Improving Diabetes Steering Committee. SGLT2 inhibitors: cardiovascular benefits beyond HbA1c- translating evidence into practice. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(5):1595-1622. doi:10.1007/s13300-019-0657-8

8. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin J, et al; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504720

SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to have a role in the management of heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, but there is a risk of exacerbation when discontinued.

SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to have a role in the management of heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, but there is a risk of exacerbation when discontinued.

About 40% of patients with heart failure (HF) also have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 Certain sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have benefited patients with HF.2 We report a case of a patient with T2DM who had signs and symptoms of hypervolemia after discontinuing the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin. The patient was found to have previously undiagnosed HF.

Case Presentation

A 58-year-old male presented for care at Malcolm Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainseville, Florida, diabetes clinic. The patient was diagnosed with T2DM at age 32 years. At 36 years, he was started on subcutaneous insulin injections, and was switched to insulin pump therapy in his early 40s. At the time of evaluation, the T2DM was managed using an insulin pump, metformin, and acarbose. He had been prescribed empagliflozin 10 mg several months before presentation, but the medication ran out about 1 month prior to evaluation, and additional refills were unavailable.

The patient reported a 1-month history of worsening exertional shortness of breath, decreased exercise tolerance, and lower extremity swelling. Vitals signs, including respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were within normal limits. Bibasilar crackles and bilateral 2+ pitting pedal edema were noted. The remaining examination was unrevealing. His most recent glycated hemoglobin A1c level from 1 month prior to the presentation was 6.4%.

Given the patient’s shortness of breath and evidence of fluid overload on examination, brain natriuretic peptide was obtained and was significantly elevated at 5,895 pg/mL. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed left ventricular ejection fraction < 20%. The patient was started on furosemide 40 mg, pending receipt of empagliflozin. A cardiology evaluation also was recommended.

Cardiac catheterization identified significant obstructions to the left anterior descending and left circumflex arteries. The patient underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention to these areas. Following initiation of medications and coronary revascularization, the patient reported significant symptom improvement. At the follow-up evaluation 8 weeks later, he was symptom free, and his physical examination was consistent with euvolemia.

Discussion