User login

Virtual visits may cut no-show rate for follow-up HF appointment

PHILADELPHIA – For patients transitioning to home after a heart failure hospitalization, substituting in-person visits with virtual, video-based visits is feasible, safe, and may reduce appointment no-show rates, results of a randomized study suggest.

Connecting patients with clinicians over secure video cut no-show rates at 7 days post-discharge by about one-third, with no difference in risk of readmission, emergency department visits, or death, compared with the traditional in-person follow-up visit, investigator Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH, reported here at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

While the video meet-up doesn’t allow for a physical exam, it’s still possible to collect history of what happened since hospital discharge, assess breathing, and complete other aspects of the follow-up visit, according to Dr. Gorodeski, director of advanced heart failure section at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

“The way we view use of virtual visits 7 days post-discharge is, in many ways, as a screening platform,” he said in a panel discussion. “If someone seems to be doing poorly, you can always invite them to come in, but most patients post discharge are not congested, and they’re doing quite well. Probably the more relevant issues are things like: Do they have their medications? Do they understand what their follow-up appointments are?”

During the virtual visit, patients are asked to hold their medication bottles up to the camera so the clinician can see what they are taking.

“Frequently, we are able to catch mistakes,” Dr. Gorodeski said. “Of note, most patients don’t bring their pill bottles to the clinic, so in some ways doing the virtual visit for that aspect was more valuable.”

Patients who opt for a virtual visit can do so from any smart phone, laptop, or desktop computer. Once logged in, they enter a virtual waiting room as the clinician receives a text notification to log in and begin the visit.

“It’s very efficient with time, and my questions were answered quickly,” said a patient in a short video Dr. Gorodeski played to illustrate the technology.

“I still feel the same connectivity with the patient,” a clinician in the video said.

There is currently no way to bill insurance companies for this type of visit, Dr. Gorodeski said when asked what initial barriers other institutions might have implementing a similar approach.

In the randomized, single-center clinical trial Dr. Gorodeski presented here at the HFSA meeting, called VIV-HF (Virtual Visits in Heart Failure Care Transitions), a total of 108 patients were randomized to the virtual visit (52 patients) or an in-person visit (56 patients).

The majority of patients (over 60%) had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, according to the reported study results.

No-show rates were 50% for the in-person visit, and 34.6% for the virtual visit, for a relative risk reduction of 31%. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance, likely because the study was underpowered, according to Dr. Gorodeski.

“This strategy may reduce postdischarge appointment no-show rates, and this needs to be studied further in larger and appropriately powered clinical trials,” he said in presenting the results.

The 7-day postdischarge outpatient clinic visit is recommended in guidelines and viewed as a way to increase care engagement while reducing risk of poor outcomes, according to VIV-HF investigators.

Support for the study came from the Hunnell Fund. Dr. Gorodeski reported being a consultant and advisor to Abbott.

cardnews@mdedge

SOURCE: Gorodeski EZ, et al. HFSA 2019. Late-Breaking Clinical Trials session.

PHILADELPHIA – For patients transitioning to home after a heart failure hospitalization, substituting in-person visits with virtual, video-based visits is feasible, safe, and may reduce appointment no-show rates, results of a randomized study suggest.

Connecting patients with clinicians over secure video cut no-show rates at 7 days post-discharge by about one-third, with no difference in risk of readmission, emergency department visits, or death, compared with the traditional in-person follow-up visit, investigator Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH, reported here at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

While the video meet-up doesn’t allow for a physical exam, it’s still possible to collect history of what happened since hospital discharge, assess breathing, and complete other aspects of the follow-up visit, according to Dr. Gorodeski, director of advanced heart failure section at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

“The way we view use of virtual visits 7 days post-discharge is, in many ways, as a screening platform,” he said in a panel discussion. “If someone seems to be doing poorly, you can always invite them to come in, but most patients post discharge are not congested, and they’re doing quite well. Probably the more relevant issues are things like: Do they have their medications? Do they understand what their follow-up appointments are?”

During the virtual visit, patients are asked to hold their medication bottles up to the camera so the clinician can see what they are taking.

“Frequently, we are able to catch mistakes,” Dr. Gorodeski said. “Of note, most patients don’t bring their pill bottles to the clinic, so in some ways doing the virtual visit for that aspect was more valuable.”

Patients who opt for a virtual visit can do so from any smart phone, laptop, or desktop computer. Once logged in, they enter a virtual waiting room as the clinician receives a text notification to log in and begin the visit.

“It’s very efficient with time, and my questions were answered quickly,” said a patient in a short video Dr. Gorodeski played to illustrate the technology.

“I still feel the same connectivity with the patient,” a clinician in the video said.

There is currently no way to bill insurance companies for this type of visit, Dr. Gorodeski said when asked what initial barriers other institutions might have implementing a similar approach.

In the randomized, single-center clinical trial Dr. Gorodeski presented here at the HFSA meeting, called VIV-HF (Virtual Visits in Heart Failure Care Transitions), a total of 108 patients were randomized to the virtual visit (52 patients) or an in-person visit (56 patients).

The majority of patients (over 60%) had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, according to the reported study results.

No-show rates were 50% for the in-person visit, and 34.6% for the virtual visit, for a relative risk reduction of 31%. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance, likely because the study was underpowered, according to Dr. Gorodeski.

“This strategy may reduce postdischarge appointment no-show rates, and this needs to be studied further in larger and appropriately powered clinical trials,” he said in presenting the results.

The 7-day postdischarge outpatient clinic visit is recommended in guidelines and viewed as a way to increase care engagement while reducing risk of poor outcomes, according to VIV-HF investigators.

Support for the study came from the Hunnell Fund. Dr. Gorodeski reported being a consultant and advisor to Abbott.

cardnews@mdedge

SOURCE: Gorodeski EZ, et al. HFSA 2019. Late-Breaking Clinical Trials session.

PHILADELPHIA – For patients transitioning to home after a heart failure hospitalization, substituting in-person visits with virtual, video-based visits is feasible, safe, and may reduce appointment no-show rates, results of a randomized study suggest.

Connecting patients with clinicians over secure video cut no-show rates at 7 days post-discharge by about one-third, with no difference in risk of readmission, emergency department visits, or death, compared with the traditional in-person follow-up visit, investigator Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH, reported here at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

While the video meet-up doesn’t allow for a physical exam, it’s still possible to collect history of what happened since hospital discharge, assess breathing, and complete other aspects of the follow-up visit, according to Dr. Gorodeski, director of advanced heart failure section at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

“The way we view use of virtual visits 7 days post-discharge is, in many ways, as a screening platform,” he said in a panel discussion. “If someone seems to be doing poorly, you can always invite them to come in, but most patients post discharge are not congested, and they’re doing quite well. Probably the more relevant issues are things like: Do they have their medications? Do they understand what their follow-up appointments are?”

During the virtual visit, patients are asked to hold their medication bottles up to the camera so the clinician can see what they are taking.

“Frequently, we are able to catch mistakes,” Dr. Gorodeski said. “Of note, most patients don’t bring their pill bottles to the clinic, so in some ways doing the virtual visit for that aspect was more valuable.”

Patients who opt for a virtual visit can do so from any smart phone, laptop, or desktop computer. Once logged in, they enter a virtual waiting room as the clinician receives a text notification to log in and begin the visit.

“It’s very efficient with time, and my questions were answered quickly,” said a patient in a short video Dr. Gorodeski played to illustrate the technology.

“I still feel the same connectivity with the patient,” a clinician in the video said.

There is currently no way to bill insurance companies for this type of visit, Dr. Gorodeski said when asked what initial barriers other institutions might have implementing a similar approach.

In the randomized, single-center clinical trial Dr. Gorodeski presented here at the HFSA meeting, called VIV-HF (Virtual Visits in Heart Failure Care Transitions), a total of 108 patients were randomized to the virtual visit (52 patients) or an in-person visit (56 patients).

The majority of patients (over 60%) had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, according to the reported study results.

No-show rates were 50% for the in-person visit, and 34.6% for the virtual visit, for a relative risk reduction of 31%. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance, likely because the study was underpowered, according to Dr. Gorodeski.

“This strategy may reduce postdischarge appointment no-show rates, and this needs to be studied further in larger and appropriately powered clinical trials,” he said in presenting the results.

The 7-day postdischarge outpatient clinic visit is recommended in guidelines and viewed as a way to increase care engagement while reducing risk of poor outcomes, according to VIV-HF investigators.

Support for the study came from the Hunnell Fund. Dr. Gorodeski reported being a consultant and advisor to Abbott.

cardnews@mdedge

SOURCE: Gorodeski EZ, et al. HFSA 2019. Late-Breaking Clinical Trials session.

REPORTING FROM HFSA 2019

Patients frequently drive too soon after ICD implantation

PARIS – Fewer than half of commercial drivers who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) recalled being told they should never drive professionally again, according to a recent Danish survey. Further, about a third of patients overall reported that they began driving soon after they received an ICD, during the period when guidelines recommend refraining from driving.

“These devices, they save lives – so what’s not to like?” lead investigator Jenny Bjerre, MD, asked at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Well, if you are a patient qualifying for an ICD, you also automatically qualify for some driving restrictions.” These are put in place because of the concern for an arrhythmia causing a loss of consciousness behind the wheel, she said.

A European consensus statement calls for a 3-month driving moratorium when an ICD is implanted for secondary prevention or after an appropriate ICD shock, and a 4-week restriction when an ICD is placed for primary prevention. All these restrictions apply to personal driver’s licenses; anyone with an ICD is permanently restricted from commercial driving according to the consensus statement, said Dr. Bjerre, of the University Hospital, Copenhagen.

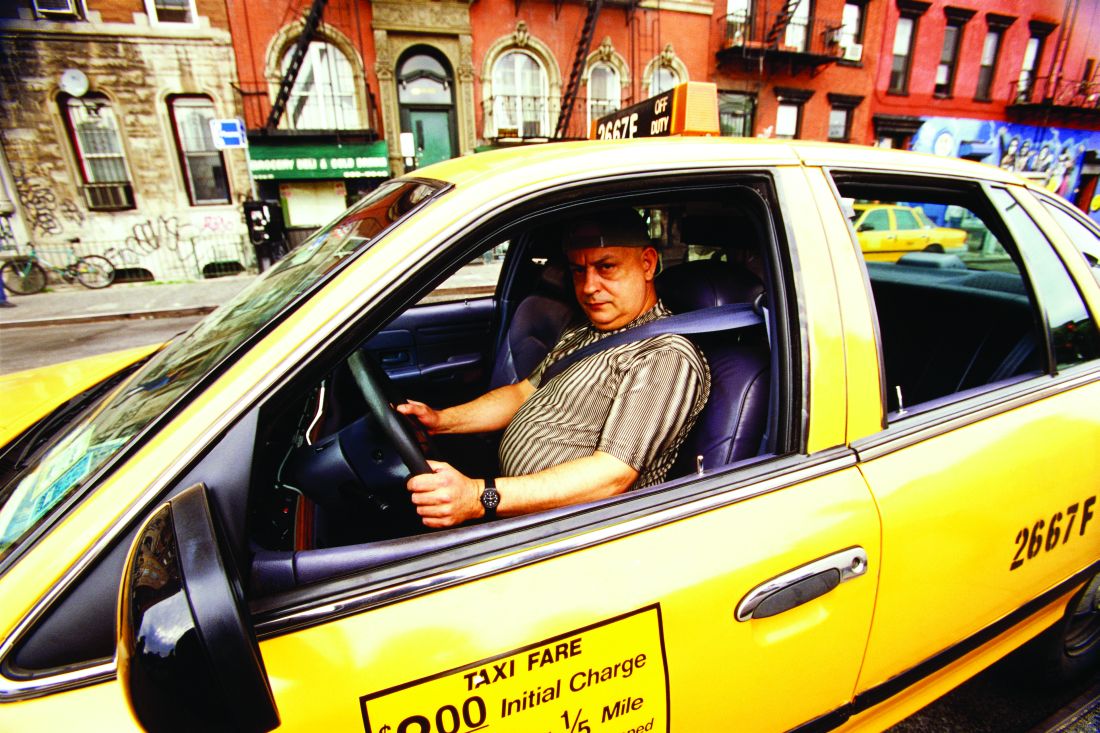

“As you can imagine, these restrictions are not that popular with the patients,” she said. She related the story of a patient, a taxi driver who had returned to a full range of physically taxing activities after his ICD implantation, but whose livelihood had been taken away from him.

Dr. Bjerre said she sought to understand the perspective of this patient, who said, “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been resuscitated!” She saw that the loss of freedom and a meaningful occupation had profoundly affected the daily life of this patient, and she became curious about adherence to driving restrictions in patients with ICDs.

Using the nationwide Danish medical record database, Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues looked at a nationwide cohort of ICD patients to see they remembered hearing about restrictions on personal and commercial driving activities after ICD implantation. They also investigated adherence to restrictions, and sought to identify what factors were associated with nonadherence.

The questionnaire developed by Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues was made available to the ICD cohort both electronically and in a paper version. Questionnaires received were linked with a variety of nationwide registries through each participant’s unique national identification number, she explained. They obtained information about comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, and socioeconomic status. Not only did this linkage give more precise and complete data than would a questionnaire alone, but it also allowed the investigators to see how responders differed from nonresponders – important in questionnaire research, said Dr. Bjerre.

The investigators were able to locate and distribute questionnaires to a total of 3,913 living adults who had received first-time ICDs during the 3-year study period. In the end, even after excluding 31 responses for missing data, 2,741 responses were used for analysis – a response rate of over 70%.

The median age of respondents was 67, and 83% were male. About half – 46% – of respondents had an ICD implanted for primary prevention. Compared with those who did respond, said Dr. Bjerre, the nonresponders “were younger, sicker, more likely to be female, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to be on guideline-directed therapy.”

Over 90% of respondents held a private driver’s license at the time of their ICD implantation, and just 7% were actively using a commercial license prior to implantation. Participants had a variety of commercial driving occupations, including driving trucks, buses, and taxis.

“Only 43% of primary prevention patients and 64% of secondary prevention patients stated that they had been informed about any driving restrictions,” said Dr. Bjerre. The figure was slightly better for patients after an ICD shock was delivered – 72% of these patients recalled hearing about driving restrictions.

“Among professional drivers – who are never supposed to drive again – only 45% said they had been informed about any professional driving restrictions,” she added.

What did patients report about their actual driving behaviors? Of patients receiving an ICD for primary prevention, 34% resumed driving within one week of ICD implantation. For those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention and those who had received an appropriate ICD shock, 43% and 30%, respectively, began driving before the recommended 3 months had elapsed.

The driving behavior of those with commercial licenses didn’t differ from the cohort as a whole: 35% of this group had resumed commercial driving.

In all the study’s subgroups, nonadherence to driving restrictions was more likely if the participant didn’t recall having been informed of the restrictions, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.34 for nonadherence. However, noted Dr. Bjerre, at least 20% of patients in all subgroups who said they’d been told not to drive still resumed driving in contravention of restrictions. “So it seems that information can’t explain everything,” she said.

Additional predictors of nonadherence included male sex, with an OR of 1.53, being the only driver in the household (OR 1.29), and being at least 60 years old (OR, 1.20). Those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention had an OR of 2.20 for nonadherence, as well.

The study had a large cohort of real-life ICD patients and the response rate was high, said Dr. Bjerre. However, there was a risk of recall bias; additionally, nonresponders differed from responders, limiting full generalizability of the data. Finally, she observed that participants may have given the answers they thought were socially desirable.

“I want to get back to our friend the taxi driver,” who was adherent to restrictions, but who kept wanting to know what the actual chances were that he’d harm someone if he resumed driving. Realizing she couldn’t give him a very precise answer, Dr. Bjerre concluded, “I do think we owe it to our patients to provide more evidence on the absolute risk of traffic accidents in these patients.”

Dr. Bjerre reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

PARIS – Fewer than half of commercial drivers who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) recalled being told they should never drive professionally again, according to a recent Danish survey. Further, about a third of patients overall reported that they began driving soon after they received an ICD, during the period when guidelines recommend refraining from driving.

“These devices, they save lives – so what’s not to like?” lead investigator Jenny Bjerre, MD, asked at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Well, if you are a patient qualifying for an ICD, you also automatically qualify for some driving restrictions.” These are put in place because of the concern for an arrhythmia causing a loss of consciousness behind the wheel, she said.

A European consensus statement calls for a 3-month driving moratorium when an ICD is implanted for secondary prevention or after an appropriate ICD shock, and a 4-week restriction when an ICD is placed for primary prevention. All these restrictions apply to personal driver’s licenses; anyone with an ICD is permanently restricted from commercial driving according to the consensus statement, said Dr. Bjerre, of the University Hospital, Copenhagen.

“As you can imagine, these restrictions are not that popular with the patients,” she said. She related the story of a patient, a taxi driver who had returned to a full range of physically taxing activities after his ICD implantation, but whose livelihood had been taken away from him.

Dr. Bjerre said she sought to understand the perspective of this patient, who said, “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been resuscitated!” She saw that the loss of freedom and a meaningful occupation had profoundly affected the daily life of this patient, and she became curious about adherence to driving restrictions in patients with ICDs.

Using the nationwide Danish medical record database, Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues looked at a nationwide cohort of ICD patients to see they remembered hearing about restrictions on personal and commercial driving activities after ICD implantation. They also investigated adherence to restrictions, and sought to identify what factors were associated with nonadherence.

The questionnaire developed by Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues was made available to the ICD cohort both electronically and in a paper version. Questionnaires received were linked with a variety of nationwide registries through each participant’s unique national identification number, she explained. They obtained information about comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, and socioeconomic status. Not only did this linkage give more precise and complete data than would a questionnaire alone, but it also allowed the investigators to see how responders differed from nonresponders – important in questionnaire research, said Dr. Bjerre.

The investigators were able to locate and distribute questionnaires to a total of 3,913 living adults who had received first-time ICDs during the 3-year study period. In the end, even after excluding 31 responses for missing data, 2,741 responses were used for analysis – a response rate of over 70%.

The median age of respondents was 67, and 83% were male. About half – 46% – of respondents had an ICD implanted for primary prevention. Compared with those who did respond, said Dr. Bjerre, the nonresponders “were younger, sicker, more likely to be female, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to be on guideline-directed therapy.”

Over 90% of respondents held a private driver’s license at the time of their ICD implantation, and just 7% were actively using a commercial license prior to implantation. Participants had a variety of commercial driving occupations, including driving trucks, buses, and taxis.

“Only 43% of primary prevention patients and 64% of secondary prevention patients stated that they had been informed about any driving restrictions,” said Dr. Bjerre. The figure was slightly better for patients after an ICD shock was delivered – 72% of these patients recalled hearing about driving restrictions.

“Among professional drivers – who are never supposed to drive again – only 45% said they had been informed about any professional driving restrictions,” she added.

What did patients report about their actual driving behaviors? Of patients receiving an ICD for primary prevention, 34% resumed driving within one week of ICD implantation. For those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention and those who had received an appropriate ICD shock, 43% and 30%, respectively, began driving before the recommended 3 months had elapsed.

The driving behavior of those with commercial licenses didn’t differ from the cohort as a whole: 35% of this group had resumed commercial driving.

In all the study’s subgroups, nonadherence to driving restrictions was more likely if the participant didn’t recall having been informed of the restrictions, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.34 for nonadherence. However, noted Dr. Bjerre, at least 20% of patients in all subgroups who said they’d been told not to drive still resumed driving in contravention of restrictions. “So it seems that information can’t explain everything,” she said.

Additional predictors of nonadherence included male sex, with an OR of 1.53, being the only driver in the household (OR 1.29), and being at least 60 years old (OR, 1.20). Those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention had an OR of 2.20 for nonadherence, as well.

The study had a large cohort of real-life ICD patients and the response rate was high, said Dr. Bjerre. However, there was a risk of recall bias; additionally, nonresponders differed from responders, limiting full generalizability of the data. Finally, she observed that participants may have given the answers they thought were socially desirable.

“I want to get back to our friend the taxi driver,” who was adherent to restrictions, but who kept wanting to know what the actual chances were that he’d harm someone if he resumed driving. Realizing she couldn’t give him a very precise answer, Dr. Bjerre concluded, “I do think we owe it to our patients to provide more evidence on the absolute risk of traffic accidents in these patients.”

Dr. Bjerre reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

PARIS – Fewer than half of commercial drivers who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) recalled being told they should never drive professionally again, according to a recent Danish survey. Further, about a third of patients overall reported that they began driving soon after they received an ICD, during the period when guidelines recommend refraining from driving.

“These devices, they save lives – so what’s not to like?” lead investigator Jenny Bjerre, MD, asked at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Well, if you are a patient qualifying for an ICD, you also automatically qualify for some driving restrictions.” These are put in place because of the concern for an arrhythmia causing a loss of consciousness behind the wheel, she said.

A European consensus statement calls for a 3-month driving moratorium when an ICD is implanted for secondary prevention or after an appropriate ICD shock, and a 4-week restriction when an ICD is placed for primary prevention. All these restrictions apply to personal driver’s licenses; anyone with an ICD is permanently restricted from commercial driving according to the consensus statement, said Dr. Bjerre, of the University Hospital, Copenhagen.

“As you can imagine, these restrictions are not that popular with the patients,” she said. She related the story of a patient, a taxi driver who had returned to a full range of physically taxing activities after his ICD implantation, but whose livelihood had been taken away from him.

Dr. Bjerre said she sought to understand the perspective of this patient, who said, “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been resuscitated!” She saw that the loss of freedom and a meaningful occupation had profoundly affected the daily life of this patient, and she became curious about adherence to driving restrictions in patients with ICDs.

Using the nationwide Danish medical record database, Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues looked at a nationwide cohort of ICD patients to see they remembered hearing about restrictions on personal and commercial driving activities after ICD implantation. They also investigated adherence to restrictions, and sought to identify what factors were associated with nonadherence.

The questionnaire developed by Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues was made available to the ICD cohort both electronically and in a paper version. Questionnaires received were linked with a variety of nationwide registries through each participant’s unique national identification number, she explained. They obtained information about comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, and socioeconomic status. Not only did this linkage give more precise and complete data than would a questionnaire alone, but it also allowed the investigators to see how responders differed from nonresponders – important in questionnaire research, said Dr. Bjerre.

The investigators were able to locate and distribute questionnaires to a total of 3,913 living adults who had received first-time ICDs during the 3-year study period. In the end, even after excluding 31 responses for missing data, 2,741 responses were used for analysis – a response rate of over 70%.

The median age of respondents was 67, and 83% were male. About half – 46% – of respondents had an ICD implanted for primary prevention. Compared with those who did respond, said Dr. Bjerre, the nonresponders “were younger, sicker, more likely to be female, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to be on guideline-directed therapy.”

Over 90% of respondents held a private driver’s license at the time of their ICD implantation, and just 7% were actively using a commercial license prior to implantation. Participants had a variety of commercial driving occupations, including driving trucks, buses, and taxis.

“Only 43% of primary prevention patients and 64% of secondary prevention patients stated that they had been informed about any driving restrictions,” said Dr. Bjerre. The figure was slightly better for patients after an ICD shock was delivered – 72% of these patients recalled hearing about driving restrictions.

“Among professional drivers – who are never supposed to drive again – only 45% said they had been informed about any professional driving restrictions,” she added.

What did patients report about their actual driving behaviors? Of patients receiving an ICD for primary prevention, 34% resumed driving within one week of ICD implantation. For those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention and those who had received an appropriate ICD shock, 43% and 30%, respectively, began driving before the recommended 3 months had elapsed.

The driving behavior of those with commercial licenses didn’t differ from the cohort as a whole: 35% of this group had resumed commercial driving.

In all the study’s subgroups, nonadherence to driving restrictions was more likely if the participant didn’t recall having been informed of the restrictions, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.34 for nonadherence. However, noted Dr. Bjerre, at least 20% of patients in all subgroups who said they’d been told not to drive still resumed driving in contravention of restrictions. “So it seems that information can’t explain everything,” she said.

Additional predictors of nonadherence included male sex, with an OR of 1.53, being the only driver in the household (OR 1.29), and being at least 60 years old (OR, 1.20). Those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention had an OR of 2.20 for nonadherence, as well.

The study had a large cohort of real-life ICD patients and the response rate was high, said Dr. Bjerre. However, there was a risk of recall bias; additionally, nonresponders differed from responders, limiting full generalizability of the data. Finally, she observed that participants may have given the answers they thought were socially desirable.

“I want to get back to our friend the taxi driver,” who was adherent to restrictions, but who kept wanting to know what the actual chances were that he’d harm someone if he resumed driving. Realizing she couldn’t give him a very precise answer, Dr. Bjerre concluded, “I do think we owe it to our patients to provide more evidence on the absolute risk of traffic accidents in these patients.”

Dr. Bjerre reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

REPORTING FROM ESC CONGRESS 2019

Cancer overtakes CVD as cause of death in high-income countries

PARIS – Though cardiovascular disease still accounts for 40% of deaths around the world, , according to new data from a global prospective study.

“Cancer deaths are becoming more frequent not because the rates of death from cancer are going up, but because we have decreased the deaths from cardiovascular disease,” said the study’s senior author, Salim Yusuf, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

A striking pattern emerged when cause of death was stratified by country income level, said fellow investigator Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, in presenting data regarding shifting global mortality patterns. Fully 55% of deaths in high-income nations were caused by cancer, compared with 30% in middle-income countries and 15% in low-income countries. In high-income countries, by contrast, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the cause of death 23% of the time, while that figure was 42% and 43% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

Looking at the data slightly differently, the ratio of cardiovascular deaths to cancer deaths for high-income countries is 0.4; for middle-income countries, the ratio is 1.3, and “One is threefold more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from cancer” in low-income countries, said Dr. Leong. Although the United States is not included in the PURE study, “recent data shows that some states in the U.S. also have higher cancer mortality than cardiovascular disease. This is a success story,” said Dr. Yusuf, since the shift is largely attributable to decreased mortality from CVD.

Dr. Leong and Dr. Yusuf each presented results from the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study, which has enrolled a total of 202,000 individuals from 27 countries on every inhabited continent but Australia. Follow-up data are available for 167,000 individuals in 21 countries. Canada, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Chile are among the most populous national that are included. Their findings were published simultaneously in the Lancet with the congress presentations (2019 Sep 3; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 and doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0).

The INTERHEART risk score, an integrated cardiovascular risk score that uses non-laboratory values such as age, smoking status, family history, and comorbidities, was calculated for all participants. “We observed that the highest predicted cardiovascular risk is in high-income countries, and the lowest, in low-income countries,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Over the study period, 11,307 deaths occurred. Over 9,000 incident cardiovascular events were observed, as were over 5,000 new cancers.

“We have some interesting observations from these data,” said Dr. Leong. “Firstly, there is a gradient in the cardiovascular disease rates, moving from lowest in high-income countries – despite the fact that their INTERHEART risk score was highest – through to highest incident cardiovascular disease in low-income countries, despite their INTERHEART risk score being lowest.” This difference, said Dr. Leong, was driven by higher myocardial infarction rates in low-income countries and higher stroke rates in middle-income countries, when compared to high-income countries.

Once a participant was subject to one of the incident diseases, though, the patterns shifted. For CVD, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and injury, the likelihood of death within 1 year was highest in low-income countries – markedly higher, in the case of CVD. For all conditions, the one-year case-fatality rate after the occurrence of an incident disease was lowest in high-income countries.

“So we are seeing a new transition,” said Dr. Yusuf, the executive director of the Population Health Research Institute and Distinguished University Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont. “The old transition was infectious diseases giving way to noncommunicable diseases. Now we are seeing a transition within noncommunicable diseases: In rich countries, cardiovascular disease is going down, perhaps due to better prevention, but I think even more importantly, due to better treatments.

“I want to hasten to add that the difference in risk between high-, middle-, and low-income countries in cardiovascular disease is not due to risk factors,” he went on. “Risk factors, if anything, are lower in the poor countries, compared to the higher-income countries.”

The shift away from cardiovascular disease mortality toward cancer mortality is also occurring in some countries that are in the upper tier of middle-income nations, including Chile, Argentina, Turkey, and Poland, said Dr. Yusuf, who presented data regarding the relative contributions of risk factors to cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the PURE study were expressed by a measure called the population attributable fraction (PAF) that captures both the hazard ratio for a particular risk factor and the prevalence of the risk factor, explained Dr. Yusuf. “Hypertension, by far, was the biggest risk factor of cardiovascular disease globally,” he added, noting that the PAF for hypertension was over 20%. Hypertension far outstripped the next most significant risk factor, high non-HDL cholesterol, which had a PAF of less than 10%.

“This was a big surprise to us: Household pollution was a big factor,” said Dr. Yusuf, who later added that particulate matter from cooking, particularly with solid fuels such as wood or charcoal, was likely the source of much household air pollution, “a big problem in middle- and low-income countries.”

Tobacco usage is decreasing, as is its contribution to cardiovascular deaths, but other commonly cited culprits for cardiovascular disease were not significant contributors to cardiovascular disease in the PURE population.

“Abdominal obesity, and not BMI” contributes to cardiovascular risk. “BMI is not a good indicator of risk,” said Dr. Yusuf in a video interview. These results were presented separately at the congress.

“Grip strength is important; in fact, it is more important than low physical activity. People have focused on physical activity – how much you do. But strength seems to be more important…We haven’t focused on the importance of strength in the past.”

“Salt doesn’t figure in at all; salt has been exaggerated as a risk factor,” said Dr. Yusuf. “Diet needs to be rethought,” and conventional thinking challenged, he added, noting that consumption of full-fat dairy, nuts, and a moderate amount of meat all were protective among the PURE cohort.

Looking next at factors contributing to mortality in the global PURE population, low educational level had the highest attributable fraction of mortality of any single risk factor, at about 12%. “This has been ignored,” said Dr. Yusuf. “In most epidemiological studies, it’s been used as a covariate, or a stratifier,” rather than addressing low education itself as a risk factor, he said.

Tobacco use, low grip strength, and poor diet all had attributable fractions of just over 10%, said Dr. Yusuf, again noting that it wasn’t fat or meat consumption that made for the riskiest diet.

Overall, metabolic risk factors accounted for the largest fraction of risk of cardiovascular disease in the PURE population, with behavioral risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use coming next. This held true across all income categories. However, in higher income nations where environmental factors and household air pollution are lower contributors to cardiovascular disease, metabolic and behavioral risk factors contributed more to cardiovascular disease risk.

Global differences in cardiovascular disease rates, stressed Dr. Yusuf, are not primarily attributable to metabolic risk factors. “The [World Health Organization] has focused on risk factors and has not focused on improved health care. Health care matters, and it matters in a big way.”

Adults aged 35-70 were recruited from 4 high-, 12 middle- and 5 low-income countries for PURE, and followed for a median 9.5 years. Cardiovascular disease and other health events salient to the study were documented both through direct contact and administrative record review, said Dr. Leong, and data about cardiovascular events and vital status were known for well over 90% of study participants.

Slightly less than half of participants were male, and over 108,000 participants were from middle income countries.

The PURE study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Ontaario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aentis, Servier Laboratories, and Glaxo Smith Kline. The study also received additional support in individual participating countries. Dr. Yusuf and Dr. Leon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

PARIS – Though cardiovascular disease still accounts for 40% of deaths around the world, , according to new data from a global prospective study.

“Cancer deaths are becoming more frequent not because the rates of death from cancer are going up, but because we have decreased the deaths from cardiovascular disease,” said the study’s senior author, Salim Yusuf, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

A striking pattern emerged when cause of death was stratified by country income level, said fellow investigator Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, in presenting data regarding shifting global mortality patterns. Fully 55% of deaths in high-income nations were caused by cancer, compared with 30% in middle-income countries and 15% in low-income countries. In high-income countries, by contrast, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the cause of death 23% of the time, while that figure was 42% and 43% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

Looking at the data slightly differently, the ratio of cardiovascular deaths to cancer deaths for high-income countries is 0.4; for middle-income countries, the ratio is 1.3, and “One is threefold more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from cancer” in low-income countries, said Dr. Leong. Although the United States is not included in the PURE study, “recent data shows that some states in the U.S. also have higher cancer mortality than cardiovascular disease. This is a success story,” said Dr. Yusuf, since the shift is largely attributable to decreased mortality from CVD.

Dr. Leong and Dr. Yusuf each presented results from the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study, which has enrolled a total of 202,000 individuals from 27 countries on every inhabited continent but Australia. Follow-up data are available for 167,000 individuals in 21 countries. Canada, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Chile are among the most populous national that are included. Their findings were published simultaneously in the Lancet with the congress presentations (2019 Sep 3; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 and doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0).

The INTERHEART risk score, an integrated cardiovascular risk score that uses non-laboratory values such as age, smoking status, family history, and comorbidities, was calculated for all participants. “We observed that the highest predicted cardiovascular risk is in high-income countries, and the lowest, in low-income countries,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Over the study period, 11,307 deaths occurred. Over 9,000 incident cardiovascular events were observed, as were over 5,000 new cancers.

“We have some interesting observations from these data,” said Dr. Leong. “Firstly, there is a gradient in the cardiovascular disease rates, moving from lowest in high-income countries – despite the fact that their INTERHEART risk score was highest – through to highest incident cardiovascular disease in low-income countries, despite their INTERHEART risk score being lowest.” This difference, said Dr. Leong, was driven by higher myocardial infarction rates in low-income countries and higher stroke rates in middle-income countries, when compared to high-income countries.

Once a participant was subject to one of the incident diseases, though, the patterns shifted. For CVD, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and injury, the likelihood of death within 1 year was highest in low-income countries – markedly higher, in the case of CVD. For all conditions, the one-year case-fatality rate after the occurrence of an incident disease was lowest in high-income countries.

“So we are seeing a new transition,” said Dr. Yusuf, the executive director of the Population Health Research Institute and Distinguished University Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont. “The old transition was infectious diseases giving way to noncommunicable diseases. Now we are seeing a transition within noncommunicable diseases: In rich countries, cardiovascular disease is going down, perhaps due to better prevention, but I think even more importantly, due to better treatments.

“I want to hasten to add that the difference in risk between high-, middle-, and low-income countries in cardiovascular disease is not due to risk factors,” he went on. “Risk factors, if anything, are lower in the poor countries, compared to the higher-income countries.”

The shift away from cardiovascular disease mortality toward cancer mortality is also occurring in some countries that are in the upper tier of middle-income nations, including Chile, Argentina, Turkey, and Poland, said Dr. Yusuf, who presented data regarding the relative contributions of risk factors to cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the PURE study were expressed by a measure called the population attributable fraction (PAF) that captures both the hazard ratio for a particular risk factor and the prevalence of the risk factor, explained Dr. Yusuf. “Hypertension, by far, was the biggest risk factor of cardiovascular disease globally,” he added, noting that the PAF for hypertension was over 20%. Hypertension far outstripped the next most significant risk factor, high non-HDL cholesterol, which had a PAF of less than 10%.

“This was a big surprise to us: Household pollution was a big factor,” said Dr. Yusuf, who later added that particulate matter from cooking, particularly with solid fuels such as wood or charcoal, was likely the source of much household air pollution, “a big problem in middle- and low-income countries.”

Tobacco usage is decreasing, as is its contribution to cardiovascular deaths, but other commonly cited culprits for cardiovascular disease were not significant contributors to cardiovascular disease in the PURE population.

“Abdominal obesity, and not BMI” contributes to cardiovascular risk. “BMI is not a good indicator of risk,” said Dr. Yusuf in a video interview. These results were presented separately at the congress.

“Grip strength is important; in fact, it is more important than low physical activity. People have focused on physical activity – how much you do. But strength seems to be more important…We haven’t focused on the importance of strength in the past.”

“Salt doesn’t figure in at all; salt has been exaggerated as a risk factor,” said Dr. Yusuf. “Diet needs to be rethought,” and conventional thinking challenged, he added, noting that consumption of full-fat dairy, nuts, and a moderate amount of meat all were protective among the PURE cohort.

Looking next at factors contributing to mortality in the global PURE population, low educational level had the highest attributable fraction of mortality of any single risk factor, at about 12%. “This has been ignored,” said Dr. Yusuf. “In most epidemiological studies, it’s been used as a covariate, or a stratifier,” rather than addressing low education itself as a risk factor, he said.

Tobacco use, low grip strength, and poor diet all had attributable fractions of just over 10%, said Dr. Yusuf, again noting that it wasn’t fat or meat consumption that made for the riskiest diet.

Overall, metabolic risk factors accounted for the largest fraction of risk of cardiovascular disease in the PURE population, with behavioral risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use coming next. This held true across all income categories. However, in higher income nations where environmental factors and household air pollution are lower contributors to cardiovascular disease, metabolic and behavioral risk factors contributed more to cardiovascular disease risk.

Global differences in cardiovascular disease rates, stressed Dr. Yusuf, are not primarily attributable to metabolic risk factors. “The [World Health Organization] has focused on risk factors and has not focused on improved health care. Health care matters, and it matters in a big way.”

Adults aged 35-70 were recruited from 4 high-, 12 middle- and 5 low-income countries for PURE, and followed for a median 9.5 years. Cardiovascular disease and other health events salient to the study were documented both through direct contact and administrative record review, said Dr. Leong, and data about cardiovascular events and vital status were known for well over 90% of study participants.

Slightly less than half of participants were male, and over 108,000 participants were from middle income countries.

The PURE study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Ontaario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aentis, Servier Laboratories, and Glaxo Smith Kline. The study also received additional support in individual participating countries. Dr. Yusuf and Dr. Leon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

PARIS – Though cardiovascular disease still accounts for 40% of deaths around the world, , according to new data from a global prospective study.

“Cancer deaths are becoming more frequent not because the rates of death from cancer are going up, but because we have decreased the deaths from cardiovascular disease,” said the study’s senior author, Salim Yusuf, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

A striking pattern emerged when cause of death was stratified by country income level, said fellow investigator Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, in presenting data regarding shifting global mortality patterns. Fully 55% of deaths in high-income nations were caused by cancer, compared with 30% in middle-income countries and 15% in low-income countries. In high-income countries, by contrast, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the cause of death 23% of the time, while that figure was 42% and 43% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

Looking at the data slightly differently, the ratio of cardiovascular deaths to cancer deaths for high-income countries is 0.4; for middle-income countries, the ratio is 1.3, and “One is threefold more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from cancer” in low-income countries, said Dr. Leong. Although the United States is not included in the PURE study, “recent data shows that some states in the U.S. also have higher cancer mortality than cardiovascular disease. This is a success story,” said Dr. Yusuf, since the shift is largely attributable to decreased mortality from CVD.

Dr. Leong and Dr. Yusuf each presented results from the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study, which has enrolled a total of 202,000 individuals from 27 countries on every inhabited continent but Australia. Follow-up data are available for 167,000 individuals in 21 countries. Canada, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Chile are among the most populous national that are included. Their findings were published simultaneously in the Lancet with the congress presentations (2019 Sep 3; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 and doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0).

The INTERHEART risk score, an integrated cardiovascular risk score that uses non-laboratory values such as age, smoking status, family history, and comorbidities, was calculated for all participants. “We observed that the highest predicted cardiovascular risk is in high-income countries, and the lowest, in low-income countries,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Over the study period, 11,307 deaths occurred. Over 9,000 incident cardiovascular events were observed, as were over 5,000 new cancers.

“We have some interesting observations from these data,” said Dr. Leong. “Firstly, there is a gradient in the cardiovascular disease rates, moving from lowest in high-income countries – despite the fact that their INTERHEART risk score was highest – through to highest incident cardiovascular disease in low-income countries, despite their INTERHEART risk score being lowest.” This difference, said Dr. Leong, was driven by higher myocardial infarction rates in low-income countries and higher stroke rates in middle-income countries, when compared to high-income countries.

Once a participant was subject to one of the incident diseases, though, the patterns shifted. For CVD, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and injury, the likelihood of death within 1 year was highest in low-income countries – markedly higher, in the case of CVD. For all conditions, the one-year case-fatality rate after the occurrence of an incident disease was lowest in high-income countries.

“So we are seeing a new transition,” said Dr. Yusuf, the executive director of the Population Health Research Institute and Distinguished University Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont. “The old transition was infectious diseases giving way to noncommunicable diseases. Now we are seeing a transition within noncommunicable diseases: In rich countries, cardiovascular disease is going down, perhaps due to better prevention, but I think even more importantly, due to better treatments.

“I want to hasten to add that the difference in risk between high-, middle-, and low-income countries in cardiovascular disease is not due to risk factors,” he went on. “Risk factors, if anything, are lower in the poor countries, compared to the higher-income countries.”

The shift away from cardiovascular disease mortality toward cancer mortality is also occurring in some countries that are in the upper tier of middle-income nations, including Chile, Argentina, Turkey, and Poland, said Dr. Yusuf, who presented data regarding the relative contributions of risk factors to cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the PURE study were expressed by a measure called the population attributable fraction (PAF) that captures both the hazard ratio for a particular risk factor and the prevalence of the risk factor, explained Dr. Yusuf. “Hypertension, by far, was the biggest risk factor of cardiovascular disease globally,” he added, noting that the PAF for hypertension was over 20%. Hypertension far outstripped the next most significant risk factor, high non-HDL cholesterol, which had a PAF of less than 10%.

“This was a big surprise to us: Household pollution was a big factor,” said Dr. Yusuf, who later added that particulate matter from cooking, particularly with solid fuels such as wood or charcoal, was likely the source of much household air pollution, “a big problem in middle- and low-income countries.”

Tobacco usage is decreasing, as is its contribution to cardiovascular deaths, but other commonly cited culprits for cardiovascular disease were not significant contributors to cardiovascular disease in the PURE population.

“Abdominal obesity, and not BMI” contributes to cardiovascular risk. “BMI is not a good indicator of risk,” said Dr. Yusuf in a video interview. These results were presented separately at the congress.

“Grip strength is important; in fact, it is more important than low physical activity. People have focused on physical activity – how much you do. But strength seems to be more important…We haven’t focused on the importance of strength in the past.”

“Salt doesn’t figure in at all; salt has been exaggerated as a risk factor,” said Dr. Yusuf. “Diet needs to be rethought,” and conventional thinking challenged, he added, noting that consumption of full-fat dairy, nuts, and a moderate amount of meat all were protective among the PURE cohort.

Looking next at factors contributing to mortality in the global PURE population, low educational level had the highest attributable fraction of mortality of any single risk factor, at about 12%. “This has been ignored,” said Dr. Yusuf. “In most epidemiological studies, it’s been used as a covariate, or a stratifier,” rather than addressing low education itself as a risk factor, he said.

Tobacco use, low grip strength, and poor diet all had attributable fractions of just over 10%, said Dr. Yusuf, again noting that it wasn’t fat or meat consumption that made for the riskiest diet.

Overall, metabolic risk factors accounted for the largest fraction of risk of cardiovascular disease in the PURE population, with behavioral risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use coming next. This held true across all income categories. However, in higher income nations where environmental factors and household air pollution are lower contributors to cardiovascular disease, metabolic and behavioral risk factors contributed more to cardiovascular disease risk.

Global differences in cardiovascular disease rates, stressed Dr. Yusuf, are not primarily attributable to metabolic risk factors. “The [World Health Organization] has focused on risk factors and has not focused on improved health care. Health care matters, and it matters in a big way.”

Adults aged 35-70 were recruited from 4 high-, 12 middle- and 5 low-income countries for PURE, and followed for a median 9.5 years. Cardiovascular disease and other health events salient to the study were documented both through direct contact and administrative record review, said Dr. Leong, and data about cardiovascular events and vital status were known for well over 90% of study participants.

Slightly less than half of participants were male, and over 108,000 participants were from middle income countries.

The PURE study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Ontaario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aentis, Servier Laboratories, and Glaxo Smith Kline. The study also received additional support in individual participating countries. Dr. Yusuf and Dr. Leon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

REPORTING FROM ESC CONGRESS 2019

Fibrinogen concentrate effective, safe for postop bleeding

SAN ANTONIO – Fibrinogen concentrate was noninferior to cryoprecipitate for controlling bleeding following cardiac surgery in the randomized FIBRES trial, Canadian investigators reported.

Among 827 patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass, there were no significant differences in the use of allogenenic transfusion products within 24 hours of surgery for patients assigned to receive fibrinogen concentrate for control of bleeding, compared with patients who received cryoprecipitate, reported Jeannie Callum, MD, from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, on behalf of coinvestigators in the FIBRES trial.

Fibrinogen concentrate, commonly used to control postoperative bleeding in Europe, was associated with numerically, but not statistically, lower incidence of both adverse events and serious adverse events than cryoprecipitate, the current standard of care in North America.

“Given its safety and logistical advantages, fibrinogen concentrate may be considered in bleeding patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia,” Dr. Callum said at the annual meeting of the AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Results of the FIBRES trial were published simultaneously in JAMA (2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17312).

Acquired hypofibrinogenemia, defined as a fibrinogen level below the range of 1.5-2.0 g/L, is a major cause of excess bleeding after cardiac surgery. European guidelines on the management of bleeding following trauma or cardiac surgery recommend the use of either cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate to control excessive bleeding in patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia, Dr. Callum noted.

Cryoprecipitate is a pooled plasma–derived product that contains fibrinogen, but also fibronectin, platelet microparticles, coagulation factors VIII and XIII, and von Willebrand factor.

Additionally, fibrinogen levels in cryoprecipitate can range from as low as 3 g/L to as high as 30 g/L, and the product is normally kept and shipped frozen, and is then thawed for use and pooled prior to administration, with a shelf life of just 4-6 hours.

In contrast, fibrinogen concentrates “are pathogen-reduced and purified; have standardized fibrinogen content (20 g/L); are lyophilized, allowing for easy storage, reconstitution, and administration; and have longer shelf life after reconstitution (up to 24 hours),” Dr. Callum and her colleagues reported.

Despite the North American preference for cryoprecipitate and the European preference for fibrinogen concentrate, there have been few studies directly comparing the two products, which prompted the FIBRES investigators to design a head-to-head trial.

The randomized trial was conducted in 11 Canadian hospitals with adults undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass for whom fibrinogen supplementation was ordered in accordance with accepted clinical standards.

Patients were randomly assigned to received either 4 g of fibrinogen concentrate or 10 units of cryoprecipitate for 24 hours, with all patients receiving additional cryoprecipitate as needed after the first day.

Of 15,412 cardiac patients treated at the participating sites, 827 patients met the trial criteria and were randomized. Because the trial met the prespecified stopping criterion for noninferiority of fibrinogen at the interim analysis, the trial was halted, leaving the 827 patients as the final analysis population.

The mean number of allogeneic blood component units administered – the primary outcome – was 16.3 units in the fibrinogen concentrate group and 17.0 units in the cryoprecipitate group (mean ratio, 0.96; P for noninferiority less than .001; P for superiority = .50).

Fibrinogen was also noninferior for the secondary outcomes of individual 24-hour and cumulative 7-day blood component transfusions, and in a post-hoc analysis of cumulative transfusions measured from product administration to 24 hours after termination of cardiopulmonary bypass. These endpoints should be interpreted with caution, however, because they were not corrected for type 1 error, the investigators noted.

Fibrinogen concentrate also appeared to be noninferior for all defined subgroups, except for patients who underwent nonelective procedures, which included all patients in critical state before surgery.

Adverse events (AEs) of any kind occurred in 66.7% of patients with fibrinogen concentrate vs. 72.7% of those on cryoprecipitate. Serious AEs occurred in 31.5% vs. 34.7%, respectively.

Thromboembolic events – stroke or transient ischemic attack, amaurosis fugax (temporary vision loss), myocardial infarction, deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, other-vessel thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or thrombophlebitis – occurred in 7% vs. 9.6%, respectively.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by the inability to blind the clinical team to the product used, by the adult-only population, and by the likelihood of variable dosing in the cryoprecipitate group.

Advantages of fibrinogen concentrate over cryoprecipitate are that the former is pathogen reduced and is easier to deliver, the investigators said.

“One important consideration is the cost differential that currently favors cryoprecipitate, but this varies across regions, and the most recent economic analysis failed to include the costs of future emerging pathogens and did not include comprehensive activity-based costing,” the investigators wrote in JAMA.

The trial was sponsored by Octapharma AG, which also provided fibrinogen concentrate. Cryoprecipitate was provided by the Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec. Dr. Callum reported receiving grants from Canadian Blood Services, Octapharma, and CSL Behring during the conduct of the study. Multiple coauthors had similar disclosures.

SOURCE: Callum J et al. JAMA. 2019 Oct 21. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.17312.

SAN ANTONIO – Fibrinogen concentrate was noninferior to cryoprecipitate for controlling bleeding following cardiac surgery in the randomized FIBRES trial, Canadian investigators reported.

Among 827 patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass, there were no significant differences in the use of allogenenic transfusion products within 24 hours of surgery for patients assigned to receive fibrinogen concentrate for control of bleeding, compared with patients who received cryoprecipitate, reported Jeannie Callum, MD, from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, on behalf of coinvestigators in the FIBRES trial.

Fibrinogen concentrate, commonly used to control postoperative bleeding in Europe, was associated with numerically, but not statistically, lower incidence of both adverse events and serious adverse events than cryoprecipitate, the current standard of care in North America.

“Given its safety and logistical advantages, fibrinogen concentrate may be considered in bleeding patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia,” Dr. Callum said at the annual meeting of the AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Results of the FIBRES trial were published simultaneously in JAMA (2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17312).

Acquired hypofibrinogenemia, defined as a fibrinogen level below the range of 1.5-2.0 g/L, is a major cause of excess bleeding after cardiac surgery. European guidelines on the management of bleeding following trauma or cardiac surgery recommend the use of either cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate to control excessive bleeding in patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia, Dr. Callum noted.

Cryoprecipitate is a pooled plasma–derived product that contains fibrinogen, but also fibronectin, platelet microparticles, coagulation factors VIII and XIII, and von Willebrand factor.

Additionally, fibrinogen levels in cryoprecipitate can range from as low as 3 g/L to as high as 30 g/L, and the product is normally kept and shipped frozen, and is then thawed for use and pooled prior to administration, with a shelf life of just 4-6 hours.

In contrast, fibrinogen concentrates “are pathogen-reduced and purified; have standardized fibrinogen content (20 g/L); are lyophilized, allowing for easy storage, reconstitution, and administration; and have longer shelf life after reconstitution (up to 24 hours),” Dr. Callum and her colleagues reported.

Despite the North American preference for cryoprecipitate and the European preference for fibrinogen concentrate, there have been few studies directly comparing the two products, which prompted the FIBRES investigators to design a head-to-head trial.

The randomized trial was conducted in 11 Canadian hospitals with adults undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass for whom fibrinogen supplementation was ordered in accordance with accepted clinical standards.

Patients were randomly assigned to received either 4 g of fibrinogen concentrate or 10 units of cryoprecipitate for 24 hours, with all patients receiving additional cryoprecipitate as needed after the first day.

Of 15,412 cardiac patients treated at the participating sites, 827 patients met the trial criteria and were randomized. Because the trial met the prespecified stopping criterion for noninferiority of fibrinogen at the interim analysis, the trial was halted, leaving the 827 patients as the final analysis population.

The mean number of allogeneic blood component units administered – the primary outcome – was 16.3 units in the fibrinogen concentrate group and 17.0 units in the cryoprecipitate group (mean ratio, 0.96; P for noninferiority less than .001; P for superiority = .50).

Fibrinogen was also noninferior for the secondary outcomes of individual 24-hour and cumulative 7-day blood component transfusions, and in a post-hoc analysis of cumulative transfusions measured from product administration to 24 hours after termination of cardiopulmonary bypass. These endpoints should be interpreted with caution, however, because they were not corrected for type 1 error, the investigators noted.

Fibrinogen concentrate also appeared to be noninferior for all defined subgroups, except for patients who underwent nonelective procedures, which included all patients in critical state before surgery.

Adverse events (AEs) of any kind occurred in 66.7% of patients with fibrinogen concentrate vs. 72.7% of those on cryoprecipitate. Serious AEs occurred in 31.5% vs. 34.7%, respectively.

Thromboembolic events – stroke or transient ischemic attack, amaurosis fugax (temporary vision loss), myocardial infarction, deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, other-vessel thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or thrombophlebitis – occurred in 7% vs. 9.6%, respectively.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by the inability to blind the clinical team to the product used, by the adult-only population, and by the likelihood of variable dosing in the cryoprecipitate group.

Advantages of fibrinogen concentrate over cryoprecipitate are that the former is pathogen reduced and is easier to deliver, the investigators said.

“One important consideration is the cost differential that currently favors cryoprecipitate, but this varies across regions, and the most recent economic analysis failed to include the costs of future emerging pathogens and did not include comprehensive activity-based costing,” the investigators wrote in JAMA.

The trial was sponsored by Octapharma AG, which also provided fibrinogen concentrate. Cryoprecipitate was provided by the Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec. Dr. Callum reported receiving grants from Canadian Blood Services, Octapharma, and CSL Behring during the conduct of the study. Multiple coauthors had similar disclosures.

SOURCE: Callum J et al. JAMA. 2019 Oct 21. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.17312.

SAN ANTONIO – Fibrinogen concentrate was noninferior to cryoprecipitate for controlling bleeding following cardiac surgery in the randomized FIBRES trial, Canadian investigators reported.

Among 827 patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass, there were no significant differences in the use of allogenenic transfusion products within 24 hours of surgery for patients assigned to receive fibrinogen concentrate for control of bleeding, compared with patients who received cryoprecipitate, reported Jeannie Callum, MD, from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, on behalf of coinvestigators in the FIBRES trial.

Fibrinogen concentrate, commonly used to control postoperative bleeding in Europe, was associated with numerically, but not statistically, lower incidence of both adverse events and serious adverse events than cryoprecipitate, the current standard of care in North America.

“Given its safety and logistical advantages, fibrinogen concentrate may be considered in bleeding patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia,” Dr. Callum said at the annual meeting of the AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Results of the FIBRES trial were published simultaneously in JAMA (2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17312).

Acquired hypofibrinogenemia, defined as a fibrinogen level below the range of 1.5-2.0 g/L, is a major cause of excess bleeding after cardiac surgery. European guidelines on the management of bleeding following trauma or cardiac surgery recommend the use of either cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate to control excessive bleeding in patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia, Dr. Callum noted.

Cryoprecipitate is a pooled plasma–derived product that contains fibrinogen, but also fibronectin, platelet microparticles, coagulation factors VIII and XIII, and von Willebrand factor.

Additionally, fibrinogen levels in cryoprecipitate can range from as low as 3 g/L to as high as 30 g/L, and the product is normally kept and shipped frozen, and is then thawed for use and pooled prior to administration, with a shelf life of just 4-6 hours.

In contrast, fibrinogen concentrates “are pathogen-reduced and purified; have standardized fibrinogen content (20 g/L); are lyophilized, allowing for easy storage, reconstitution, and administration; and have longer shelf life after reconstitution (up to 24 hours),” Dr. Callum and her colleagues reported.

Despite the North American preference for cryoprecipitate and the European preference for fibrinogen concentrate, there have been few studies directly comparing the two products, which prompted the FIBRES investigators to design a head-to-head trial.

The randomized trial was conducted in 11 Canadian hospitals with adults undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass for whom fibrinogen supplementation was ordered in accordance with accepted clinical standards.

Patients were randomly assigned to received either 4 g of fibrinogen concentrate or 10 units of cryoprecipitate for 24 hours, with all patients receiving additional cryoprecipitate as needed after the first day.

Of 15,412 cardiac patients treated at the participating sites, 827 patients met the trial criteria and were randomized. Because the trial met the prespecified stopping criterion for noninferiority of fibrinogen at the interim analysis, the trial was halted, leaving the 827 patients as the final analysis population.

The mean number of allogeneic blood component units administered – the primary outcome – was 16.3 units in the fibrinogen concentrate group and 17.0 units in the cryoprecipitate group (mean ratio, 0.96; P for noninferiority less than .001; P for superiority = .50).

Fibrinogen was also noninferior for the secondary outcomes of individual 24-hour and cumulative 7-day blood component transfusions, and in a post-hoc analysis of cumulative transfusions measured from product administration to 24 hours after termination of cardiopulmonary bypass. These endpoints should be interpreted with caution, however, because they were not corrected for type 1 error, the investigators noted.

Fibrinogen concentrate also appeared to be noninferior for all defined subgroups, except for patients who underwent nonelective procedures, which included all patients in critical state before surgery.

Adverse events (AEs) of any kind occurred in 66.7% of patients with fibrinogen concentrate vs. 72.7% of those on cryoprecipitate. Serious AEs occurred in 31.5% vs. 34.7%, respectively.

Thromboembolic events – stroke or transient ischemic attack, amaurosis fugax (temporary vision loss), myocardial infarction, deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, other-vessel thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or thrombophlebitis – occurred in 7% vs. 9.6%, respectively.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by the inability to blind the clinical team to the product used, by the adult-only population, and by the likelihood of variable dosing in the cryoprecipitate group.

Advantages of fibrinogen concentrate over cryoprecipitate are that the former is pathogen reduced and is easier to deliver, the investigators said.

“One important consideration is the cost differential that currently favors cryoprecipitate, but this varies across regions, and the most recent economic analysis failed to include the costs of future emerging pathogens and did not include comprehensive activity-based costing,” the investigators wrote in JAMA.

The trial was sponsored by Octapharma AG, which also provided fibrinogen concentrate. Cryoprecipitate was provided by the Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec. Dr. Callum reported receiving grants from Canadian Blood Services, Octapharma, and CSL Behring during the conduct of the study. Multiple coauthors had similar disclosures.

SOURCE: Callum J et al. JAMA. 2019 Oct 21. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.17312.

REPORTING FROM AABB 2019

Starting PCSK9 inhibitor in acute-phase ACS under study

PARIS – The first-ever randomized trial of in-hospital initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor on top of guideline-recommended high-intensity statin therapy in the very-high-risk acute phase of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) safely resulted in dramatically lower LDL cholesterol levels than with early prescribing of a high-intensity statin alone, Konstantinos C. Koskinas, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

compared with 11% of patients randomized to high-intensity atorvastatin at 40 mg/day plus placebo injections. Moreover, 96% of patients on atorvastatin 40 mg/day plus evolocumab at 420 mg per subcutaneous injection were below the former target of an LDL cholesterol less than 70 mg/dL, as were 38% of those on the high-intensity statin alone, according to Dr. Koskinas, a cardiologist at the University of Bern (Switzerland).

The seven-center Swiss EVOPACS trial, featuring 308 ACS patients, could be considered a proof-of-concept study, as it lacked the size and duration to be powered to assess clinical outcomes.

“The clinical impact of very early LDL lowering with evolocumab initiated in the acute setting of ACS warrants further investigation in a dedicated cardiovascular outcomes trial,” Dr. Koskinas asserted. “We see this as the natural next step. Discussions are underway about a long-term trial with clinical endpoints, but no decisions have been made.”

The rationale for the EVOPACS trial is based upon current standard practice in ACS management, which includes initiation of a high-intensity statin during the acute phase of ACS, a particularly high-risk period for recurrent events. This practice has a Class IA recommendation in the guidelines based on published evidence that it results in a significantly reduced rate of the composite of death, MI, or rehospitalization for ACS within 30 days, compared with a less aggressive approach to LDL cholesterol lowering.

Yet even though the PCSK9 inhibitors are the 800-lb gorillas of LDL cholesterol lowering, they’ve never been tested in the setting of acute-phase ACS. For example, in the landmark ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial, alirocumab was initiated on average 2.6 months after ACS, while in FOURIER the lag time between ACS and the start of evolocumab was 3.4 years, the cardiologist noted.

In contrast, all of the 37% of EVOPACS participants with an ST-segment elevation MI were enrolled in the study and on treatment within 24 hours after symptom onset. So were more than one-third of those with non–ST-elevation ACS, with the remainder getting onboard 24-72 hours after symptom onset.

The safety and tolerability of dual LDL cholesterol–lowering therapy were excellent in the brief EVOPACS study. There were no significant between-group differences in adverse events or serious adverse events, nor in prespecified events of special interest, including muscle pain, neurocognitive changes, or elevated liver enzyme levels.

The LDL cholesterol lowering achieved with dual therapy in EVOPACS was jaw dropping: Over the course of 8 weeks, the mean LDL cholesterol went from 132 to 31 mg/dL. In patients on early high-intensity atorvastatin alone, LDL cholesterol went from 139 to 80 mg/dL.

The full details of the EVOPACS trial have been published (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.010.

The trial was funded by Amgen. Dr. Koskinas reported receiving honoraria from Amgen and Sanofi.