User login

Hidden CABG costs will disrupt bundled payment systems

COLORADO SPRINGS – With bundled payment models for coronary artery bypass graft surgery looming ahead, it’s vital that cardiac surgeons take a hard look at the procedure’s hidden costs – namely, the steep price tag for postoperative complications, James H. Mehaffey, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

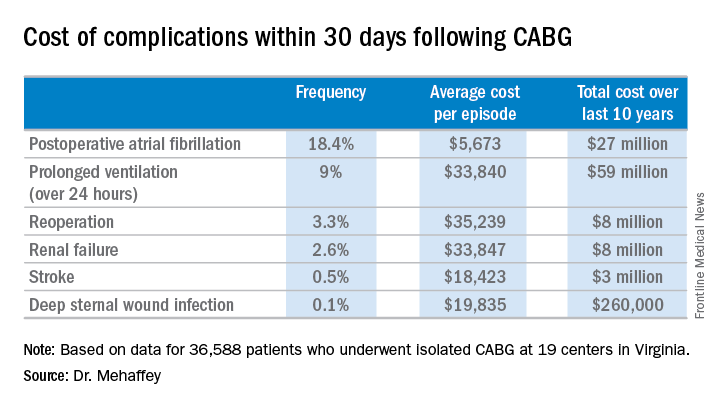

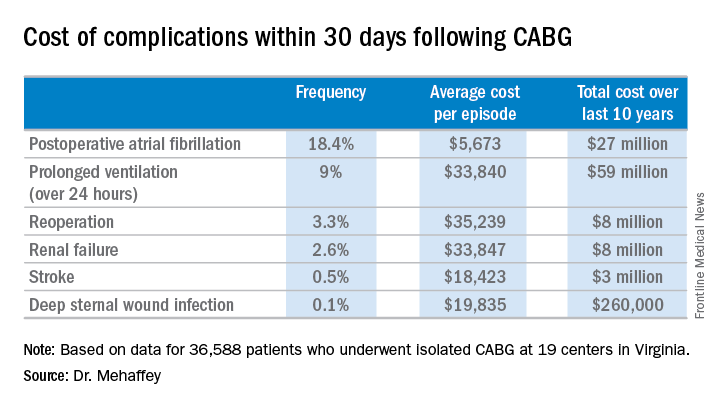

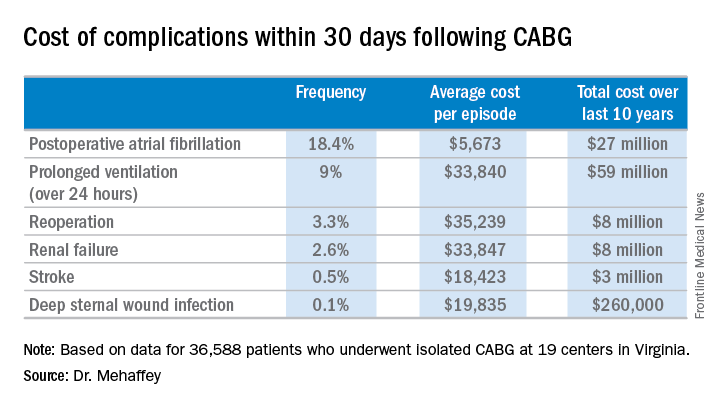

He presented a retrospective study of the 30-day hospital costs for all 36,588 patients who underwent isolated CABG during 2006-2015 at the 19 Virginia centers where the surgery is performed. This was a typical CABG population, with an average predicted risk of mortality of 1.9%. The actual 30-day mortality was 0.6%, so the surgical performance was better than expected.

“The population of patients experiencing one or more major comorbidities demonstrated a significant and dramatic increase in total hospital costs. It was an exponential increase with each additional major morbidity,” reported Dr. Mehaffey of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Indeed, the average cost jumped from $36,580 for uncomplicated surgery to $64,542 with one major complication, $111,239 with two, and $194,043 with three.

The two most frequent major complications were postoperative atrial fibrillation, which occurred in 18.4% of patients, and prolonged ventilation for longer than 24 hours, which occurred in 9%. Over the course of the decade-long study period, the 19 medical centers in the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative collectively spent roughly $59 million on prolonged ventilation and $27 million for postoperative atrial fibrillation.

The cost of CABG during the study years outpaced the CMS health care–specific inflation rate, and this escalating cost was driven primarily by postoperative complications.

For the Virginia cardiac surgery collaborative, these data on the cost of postoperative complications will be utilized to prioritize quality improvement projects.

For example, during the past decade, the Virginia collaborative made reduction in the rate of postoperative atrial fibrillation a priority. Toward that end, the collaborative developed a protocol for routine perioperative prophylactic amiodarone therapy.

“At the beginning of the study decade we had postoperative atrial fibrillation rates above 25%. The average for the entire decade was just over 18%, and in the last couple years we’ve been in the 15%-16% range. So I think we are moving the needle on this. We are making a meaningful impact,” Dr. Mehaffey said.

“We’ve already used the complication cost data to do a cost-effectiveness analysis of our prophylactic amiodarone innovation. We showed we saved an average of $250 per patient, even though we’re treating a bunch of patients who’d never get that complication,” he continued.

This sort of data on the cost of adverse events is also critical to accurately risk-adjust bundled payment models.

Discussant Richard J. Shemin, MD, asked if there was much variability in postoperative complication costs between the CABG centers in the Virginia collaborative.

The variability is enormous, Dr. Mehaffey replied. Investigators recently plugged the last 5 years worth of hospital cost and complication rate data into a proposed CABG bundled payment model and extrapolated what that would mean over the next 5 years.

“There were some institutions that would be positive by a couple million dollars from this payment system and some that were losing more than $20 million, just because of the cost variability,” said Dr. Mehaffey.

Dr. Shemin also noted that the Virginia collaborative was able to collect 30-day outcome data only through the STS database, yet the bundled payment programs are based on the 90-day postoperative experience.

“How do we capture the costs in that full 90 days that we’ll be responsible for?” asked Dr. Shemin, professor of surgery and codirector of the UCLA Cardiovascular Center.

Dr. Mehaffey said that’s indeed an important question, since a major complication such as stroke or deep sternal wound infection typically entails considerable long-term costs and repeated hospital admissions beyond the 30-day window. In Virginia, the cardiac surgery collaborative is working with payers to gain access to the 90 days worth of patient data.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

COLORADO SPRINGS – With bundled payment models for coronary artery bypass graft surgery looming ahead, it’s vital that cardiac surgeons take a hard look at the procedure’s hidden costs – namely, the steep price tag for postoperative complications, James H. Mehaffey, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

He presented a retrospective study of the 30-day hospital costs for all 36,588 patients who underwent isolated CABG during 2006-2015 at the 19 Virginia centers where the surgery is performed. This was a typical CABG population, with an average predicted risk of mortality of 1.9%. The actual 30-day mortality was 0.6%, so the surgical performance was better than expected.

“The population of patients experiencing one or more major comorbidities demonstrated a significant and dramatic increase in total hospital costs. It was an exponential increase with each additional major morbidity,” reported Dr. Mehaffey of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Indeed, the average cost jumped from $36,580 for uncomplicated surgery to $64,542 with one major complication, $111,239 with two, and $194,043 with three.

The two most frequent major complications were postoperative atrial fibrillation, which occurred in 18.4% of patients, and prolonged ventilation for longer than 24 hours, which occurred in 9%. Over the course of the decade-long study period, the 19 medical centers in the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative collectively spent roughly $59 million on prolonged ventilation and $27 million for postoperative atrial fibrillation.

The cost of CABG during the study years outpaced the CMS health care–specific inflation rate, and this escalating cost was driven primarily by postoperative complications.

For the Virginia cardiac surgery collaborative, these data on the cost of postoperative complications will be utilized to prioritize quality improvement projects.

For example, during the past decade, the Virginia collaborative made reduction in the rate of postoperative atrial fibrillation a priority. Toward that end, the collaborative developed a protocol for routine perioperative prophylactic amiodarone therapy.

“At the beginning of the study decade we had postoperative atrial fibrillation rates above 25%. The average for the entire decade was just over 18%, and in the last couple years we’ve been in the 15%-16% range. So I think we are moving the needle on this. We are making a meaningful impact,” Dr. Mehaffey said.

“We’ve already used the complication cost data to do a cost-effectiveness analysis of our prophylactic amiodarone innovation. We showed we saved an average of $250 per patient, even though we’re treating a bunch of patients who’d never get that complication,” he continued.

This sort of data on the cost of adverse events is also critical to accurately risk-adjust bundled payment models.

Discussant Richard J. Shemin, MD, asked if there was much variability in postoperative complication costs between the CABG centers in the Virginia collaborative.

The variability is enormous, Dr. Mehaffey replied. Investigators recently plugged the last 5 years worth of hospital cost and complication rate data into a proposed CABG bundled payment model and extrapolated what that would mean over the next 5 years.

“There were some institutions that would be positive by a couple million dollars from this payment system and some that were losing more than $20 million, just because of the cost variability,” said Dr. Mehaffey.

Dr. Shemin also noted that the Virginia collaborative was able to collect 30-day outcome data only through the STS database, yet the bundled payment programs are based on the 90-day postoperative experience.

“How do we capture the costs in that full 90 days that we’ll be responsible for?” asked Dr. Shemin, professor of surgery and codirector of the UCLA Cardiovascular Center.

Dr. Mehaffey said that’s indeed an important question, since a major complication such as stroke or deep sternal wound infection typically entails considerable long-term costs and repeated hospital admissions beyond the 30-day window. In Virginia, the cardiac surgery collaborative is working with payers to gain access to the 90 days worth of patient data.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

COLORADO SPRINGS – With bundled payment models for coronary artery bypass graft surgery looming ahead, it’s vital that cardiac surgeons take a hard look at the procedure’s hidden costs – namely, the steep price tag for postoperative complications, James H. Mehaffey, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

He presented a retrospective study of the 30-day hospital costs for all 36,588 patients who underwent isolated CABG during 2006-2015 at the 19 Virginia centers where the surgery is performed. This was a typical CABG population, with an average predicted risk of mortality of 1.9%. The actual 30-day mortality was 0.6%, so the surgical performance was better than expected.

“The population of patients experiencing one or more major comorbidities demonstrated a significant and dramatic increase in total hospital costs. It was an exponential increase with each additional major morbidity,” reported Dr. Mehaffey of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Indeed, the average cost jumped from $36,580 for uncomplicated surgery to $64,542 with one major complication, $111,239 with two, and $194,043 with three.

The two most frequent major complications were postoperative atrial fibrillation, which occurred in 18.4% of patients, and prolonged ventilation for longer than 24 hours, which occurred in 9%. Over the course of the decade-long study period, the 19 medical centers in the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative collectively spent roughly $59 million on prolonged ventilation and $27 million for postoperative atrial fibrillation.

The cost of CABG during the study years outpaced the CMS health care–specific inflation rate, and this escalating cost was driven primarily by postoperative complications.

For the Virginia cardiac surgery collaborative, these data on the cost of postoperative complications will be utilized to prioritize quality improvement projects.

For example, during the past decade, the Virginia collaborative made reduction in the rate of postoperative atrial fibrillation a priority. Toward that end, the collaborative developed a protocol for routine perioperative prophylactic amiodarone therapy.

“At the beginning of the study decade we had postoperative atrial fibrillation rates above 25%. The average for the entire decade was just over 18%, and in the last couple years we’ve been in the 15%-16% range. So I think we are moving the needle on this. We are making a meaningful impact,” Dr. Mehaffey said.

“We’ve already used the complication cost data to do a cost-effectiveness analysis of our prophylactic amiodarone innovation. We showed we saved an average of $250 per patient, even though we’re treating a bunch of patients who’d never get that complication,” he continued.

This sort of data on the cost of adverse events is also critical to accurately risk-adjust bundled payment models.

Discussant Richard J. Shemin, MD, asked if there was much variability in postoperative complication costs between the CABG centers in the Virginia collaborative.

The variability is enormous, Dr. Mehaffey replied. Investigators recently plugged the last 5 years worth of hospital cost and complication rate data into a proposed CABG bundled payment model and extrapolated what that would mean over the next 5 years.

“There were some institutions that would be positive by a couple million dollars from this payment system and some that were losing more than $20 million, just because of the cost variability,” said Dr. Mehaffey.

Dr. Shemin also noted that the Virginia collaborative was able to collect 30-day outcome data only through the STS database, yet the bundled payment programs are based on the 90-day postoperative experience.

“How do we capture the costs in that full 90 days that we’ll be responsible for?” asked Dr. Shemin, professor of surgery and codirector of the UCLA Cardiovascular Center.

Dr. Mehaffey said that’s indeed an important question, since a major complication such as stroke or deep sternal wound infection typically entails considerable long-term costs and repeated hospital admissions beyond the 30-day window. In Virginia, the cardiac surgery collaborative is working with payers to gain access to the 90 days worth of patient data.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

AT THE WTSA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The average 30-day total hospital cost of an isolated CABG procedure during 2006-2015 in Virginia was $36,580 if there were no postoperative complications, jumping to $64,542 with one major complication and $111,239 with two.

Data source: A retrospective study of the 30-day total hospital costs for all isolated CABG procedures performed in Virginia during 2006-2015.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Malperfusion key in aortic dissection repair outcomes

Early repair is the standard of care for patients with type A aortic dissection, but the presence of malperfusion rather than the timing of surgery may be a major determinant in patient survival both in the hospital and in the long term, according to an analysis of patients with acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period at the University of Bristol (England).

“Malperfusion at presentation rather than the timing of intervention is the major risk factor for death in both the short term and long term in patients undergoing surgical repair of type A aortic dissection,” Pradeep Narayan, FRCS, and his colleagues said in reporting their findings in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (154:81-6). Nonetheless, Dr. Narayan and his colleagues acknowledged that early operation prevents the development of malperfusion and is the best option for restoring normal perfusion for patients who already have malperfusion.

Their study analyzed results from two different groups of patients who had surgery for repair of acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period: 72 in the early surgery group that had operative repair within 12 hours of symptom onset; and 80 in the late-surgery group that had the operation 12 hours or more after symptoms first appeared. A total of 205 patients underwent surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in that period, but only 152 cases had recorded the timing of surgery from onset of symptoms. The median time between arrival at the center and surgery was 3 hours.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that 39% (60) of the 152 patients had malperfusion. Organ malperfusion was actually more common in the early surgery group, although the difference was not significant: 48.6% vs. 31.3% in the late-surgery group (P = .29). Early mortality was also similar between the two groups: 19.4% in the early surgery group and 13.8% in the late surgery group (P = .8). In terms of late survival, the study found no difference between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that malperfusion and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting were independent predictors of survival, with hazard ratios of 2.65 (P = .01) and 3.03 (P = .03), respectively. As a nonlinear variable, time to surgery showed an inverse relationship with late mortality (HR, 0.51; P = .26), but as a linear variable when adjusted for other covariates, including malperfusion, it did not affect survival (HR, 1.01; P = .09).

“The main finding of the present study is that almost 40% of patients undergoing repair of type A aortic dissection had evidence of malperfusion,” Dr. Narayan and his coauthors said. “The second important finding is that the presence of malperfusion was associated with significantly increased risk of death in both the short-term and long-term follow-up.” While a delayed operation was associated with a reduced risk of death, it was not significant when accounting for malperfusion.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors acknowledged limitations of their study, the most important of which was the including of different types of malperfusion as a single variable. Also, the small sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Malperfusion has the potential to serve as a marker for the need for surgery in type A aortic dissection, but the inability to identify the true risk of developing malperfusion in the first 12-24 hours after acute type A dissection means that the indication for early surgery will remain unchanged, James I. Fann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University says in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:87-8).

“The findings of Narayan and colleagues impel us to review the history of the development of the classification and treatment (or in fact vice versa) of acute type A dissection and to acknowledge that early timing of surgery in these high-risk patients was originally proposed to prevent malperfusion and to respond to the most catastrophic complications,” Dr. Fann said.

But Dr. Fann cautioned against “being dismissive” of their findings, because such questioning and re-evaluation are essential in developing appropriate treatments. “Now, the question is whether we can identify the cohort of patients who are at lower risk for the development of malperfusion and tailor their treatment,” he said.

Dr. Fann had no financial relationships to disclose.

Malperfusion has the potential to serve as a marker for the need for surgery in type A aortic dissection, but the inability to identify the true risk of developing malperfusion in the first 12-24 hours after acute type A dissection means that the indication for early surgery will remain unchanged, James I. Fann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University says in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:87-8).

“The findings of Narayan and colleagues impel us to review the history of the development of the classification and treatment (or in fact vice versa) of acute type A dissection and to acknowledge that early timing of surgery in these high-risk patients was originally proposed to prevent malperfusion and to respond to the most catastrophic complications,” Dr. Fann said.

But Dr. Fann cautioned against “being dismissive” of their findings, because such questioning and re-evaluation are essential in developing appropriate treatments. “Now, the question is whether we can identify the cohort of patients who are at lower risk for the development of malperfusion and tailor their treatment,” he said.

Dr. Fann had no financial relationships to disclose.

Malperfusion has the potential to serve as a marker for the need for surgery in type A aortic dissection, but the inability to identify the true risk of developing malperfusion in the first 12-24 hours after acute type A dissection means that the indication for early surgery will remain unchanged, James I. Fann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University says in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:87-8).

“The findings of Narayan and colleagues impel us to review the history of the development of the classification and treatment (or in fact vice versa) of acute type A dissection and to acknowledge that early timing of surgery in these high-risk patients was originally proposed to prevent malperfusion and to respond to the most catastrophic complications,” Dr. Fann said.

But Dr. Fann cautioned against “being dismissive” of their findings, because such questioning and re-evaluation are essential in developing appropriate treatments. “Now, the question is whether we can identify the cohort of patients who are at lower risk for the development of malperfusion and tailor their treatment,” he said.

Dr. Fann had no financial relationships to disclose.

Early repair is the standard of care for patients with type A aortic dissection, but the presence of malperfusion rather than the timing of surgery may be a major determinant in patient survival both in the hospital and in the long term, according to an analysis of patients with acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period at the University of Bristol (England).

“Malperfusion at presentation rather than the timing of intervention is the major risk factor for death in both the short term and long term in patients undergoing surgical repair of type A aortic dissection,” Pradeep Narayan, FRCS, and his colleagues said in reporting their findings in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (154:81-6). Nonetheless, Dr. Narayan and his colleagues acknowledged that early operation prevents the development of malperfusion and is the best option for restoring normal perfusion for patients who already have malperfusion.

Their study analyzed results from two different groups of patients who had surgery for repair of acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period: 72 in the early surgery group that had operative repair within 12 hours of symptom onset; and 80 in the late-surgery group that had the operation 12 hours or more after symptoms first appeared. A total of 205 patients underwent surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in that period, but only 152 cases had recorded the timing of surgery from onset of symptoms. The median time between arrival at the center and surgery was 3 hours.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that 39% (60) of the 152 patients had malperfusion. Organ malperfusion was actually more common in the early surgery group, although the difference was not significant: 48.6% vs. 31.3% in the late-surgery group (P = .29). Early mortality was also similar between the two groups: 19.4% in the early surgery group and 13.8% in the late surgery group (P = .8). In terms of late survival, the study found no difference between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that malperfusion and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting were independent predictors of survival, with hazard ratios of 2.65 (P = .01) and 3.03 (P = .03), respectively. As a nonlinear variable, time to surgery showed an inverse relationship with late mortality (HR, 0.51; P = .26), but as a linear variable when adjusted for other covariates, including malperfusion, it did not affect survival (HR, 1.01; P = .09).

“The main finding of the present study is that almost 40% of patients undergoing repair of type A aortic dissection had evidence of malperfusion,” Dr. Narayan and his coauthors said. “The second important finding is that the presence of malperfusion was associated with significantly increased risk of death in both the short-term and long-term follow-up.” While a delayed operation was associated with a reduced risk of death, it was not significant when accounting for malperfusion.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors acknowledged limitations of their study, the most important of which was the including of different types of malperfusion as a single variable. Also, the small sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Early repair is the standard of care for patients with type A aortic dissection, but the presence of malperfusion rather than the timing of surgery may be a major determinant in patient survival both in the hospital and in the long term, according to an analysis of patients with acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period at the University of Bristol (England).

“Malperfusion at presentation rather than the timing of intervention is the major risk factor for death in both the short term and long term in patients undergoing surgical repair of type A aortic dissection,” Pradeep Narayan, FRCS, and his colleagues said in reporting their findings in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (154:81-6). Nonetheless, Dr. Narayan and his colleagues acknowledged that early operation prevents the development of malperfusion and is the best option for restoring normal perfusion for patients who already have malperfusion.

Their study analyzed results from two different groups of patients who had surgery for repair of acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period: 72 in the early surgery group that had operative repair within 12 hours of symptom onset; and 80 in the late-surgery group that had the operation 12 hours or more after symptoms first appeared. A total of 205 patients underwent surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in that period, but only 152 cases had recorded the timing of surgery from onset of symptoms. The median time between arrival at the center and surgery was 3 hours.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that 39% (60) of the 152 patients had malperfusion. Organ malperfusion was actually more common in the early surgery group, although the difference was not significant: 48.6% vs. 31.3% in the late-surgery group (P = .29). Early mortality was also similar between the two groups: 19.4% in the early surgery group and 13.8% in the late surgery group (P = .8). In terms of late survival, the study found no difference between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that malperfusion and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting were independent predictors of survival, with hazard ratios of 2.65 (P = .01) and 3.03 (P = .03), respectively. As a nonlinear variable, time to surgery showed an inverse relationship with late mortality (HR, 0.51; P = .26), but as a linear variable when adjusted for other covariates, including malperfusion, it did not affect survival (HR, 1.01; P = .09).

“The main finding of the present study is that almost 40% of patients undergoing repair of type A aortic dissection had evidence of malperfusion,” Dr. Narayan and his coauthors said. “The second important finding is that the presence of malperfusion was associated with significantly increased risk of death in both the short-term and long-term follow-up.” While a delayed operation was associated with a reduced risk of death, it was not significant when accounting for malperfusion.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors acknowledged limitations of their study, the most important of which was the including of different types of malperfusion as a single variable. Also, the small sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Malperfusion is a main determinant of outcomes for patients having surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection.

Major finding: Patients in the early surgery group (surgery within 12 hours of onset) were more likely to have malperfusion than those who had surgery later, 47% vs. 31%.

Data source: Single-center analysis of 152 operations for repair of acute type A aortic dissections over a 17-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

VA cohort study: Individualize SSI prophylaxis based on patient factors

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The SSI incidence was 0.95% vs. 1.48% with combination vs. single agent–therapy in cardiac surgery patients. Acute kidney injuries occurred in 23.75% of all surgery patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% with vancomycin or a beta-lactam, respectively.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of more than 70,000 surgical procedures.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

Ventricular assist devices linked to sepsis

NEW ORLEANS – Back in 2008, there was only one case.

Since then, however, the number of patients with ventricular assist devices who developed sepsis while being treated in the cardiac unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, appeared to be noticeably growing. So, investigators launched a study to confirm their suspicions and to learn more about the underlying causes.

“Bloodstream infection is a serious infection, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what’s happening,’ ” explained Ira Das, MD, a consultant microbiologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common cause, present in 32% of the 25 cases. Sepsis was caused by Enterococcus faecium in 12%, Candida parapsilosis in 8%, and Staphylococcus aureus in 2%. Another 4% were either Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, C. guilliermondii, or C. orthopsilosis. The remaining 16% of bloodstream infections were polymicrobial.

Less certain was the source of these infections.

“In the majority of cases, we didn’t know where it was coming from,” Dr. Das said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. In 6 of the 25 cases, VAD was confirmed to be the focus of infection, either through imaging or because a failing component of the explanted device was examined later. An intravascular catheter was the source in another 5 patients, and in 14 cases, the source remained a mystery.

“Some of these infections just might have been hard to see,” Dr. Das said. “If the infection is inside the device, it’s not always easy to visualize.”

The study supports earlier findings from a review article that points to a significant infection risk associated with the implantation of VADs (Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 Sep;8[5]:627-34). That article’s authors noted, “Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of LVAD [left ventricular assist device] therapy.”

In a previous study of people with end-stage heart failure, other investigators noted that, “despite the substantial survival benefit, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of the left ventricular assist device were considerable. In particular, infection and mechanical failure of the device were major factors in the 2-year survival rate of only 23%” (N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345[20]:1435-43).

Similarly, in the current study, mortality was higher among those with sepsis and a VAD. Mortality was 39% – including eight patients who died with a VAD in situ and one following cardiac transplantation. However, Dr. Das cautioned, “It’s a small number, and there are other factors that could have contributed. They all go on anticoagulants so they have bleeding tendencies, and many of the patients are in the ICU with multiorgan failure.”

Infection prevention remains paramount to minimize mortality and other adverse events associated with a patient’s having a VAD. “We have to make sure that infection control procedures and our treatments are up to the optimal standard,” Dr. Das said. “It’s not easy to remove the device.”

Of the 129 VADs implanted, 68 were long-term LVADs, 11 were short-term LVADs, 15 were right ventricular devices, and 35 were biventricular devices.

The study is ongoing. The data presented at the meeting were collected up until December 2016.

“Since then, I’ve seen two more cases, and – very interestingly – one was Haemophilus influenzae,” Dr. Das said. “The patient was on the device, he was at home, and he came in with bacteremia.” Again, the source of infection proved elusive. “With H. influenzae, you would think it was coming from his chest, but the chest x-ray was normal.”

The second case, a patient with a coagulase-negative staphylococci bloodstream infection, was scheduled for a PET scan at the time of Dr. Das’ presentation to try to identify the source of infection.

Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

Modern technology saves our patients' lives, but there is always another side to the coin. Reports that LVAD devices are associated with a high incidence of bloodstream infections is important for future clinical practice. The fact that the causes and risk factors for these infections are unknown make this phenomena one of high interest.

Modern technology saves our patients' lives, but there is always another side to the coin. Reports that LVAD devices are associated with a high incidence of bloodstream infections is important for future clinical practice. The fact that the causes and risk factors for these infections are unknown make this phenomena one of high interest.

Modern technology saves our patients' lives, but there is always another side to the coin. Reports that LVAD devices are associated with a high incidence of bloodstream infections is important for future clinical practice. The fact that the causes and risk factors for these infections are unknown make this phenomena one of high interest.

NEW ORLEANS – Back in 2008, there was only one case.

Since then, however, the number of patients with ventricular assist devices who developed sepsis while being treated in the cardiac unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, appeared to be noticeably growing. So, investigators launched a study to confirm their suspicions and to learn more about the underlying causes.

“Bloodstream infection is a serious infection, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what’s happening,’ ” explained Ira Das, MD, a consultant microbiologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common cause, present in 32% of the 25 cases. Sepsis was caused by Enterococcus faecium in 12%, Candida parapsilosis in 8%, and Staphylococcus aureus in 2%. Another 4% were either Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, C. guilliermondii, or C. orthopsilosis. The remaining 16% of bloodstream infections were polymicrobial.

Less certain was the source of these infections.

“In the majority of cases, we didn’t know where it was coming from,” Dr. Das said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. In 6 of the 25 cases, VAD was confirmed to be the focus of infection, either through imaging or because a failing component of the explanted device was examined later. An intravascular catheter was the source in another 5 patients, and in 14 cases, the source remained a mystery.

“Some of these infections just might have been hard to see,” Dr. Das said. “If the infection is inside the device, it’s not always easy to visualize.”

The study supports earlier findings from a review article that points to a significant infection risk associated with the implantation of VADs (Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 Sep;8[5]:627-34). That article’s authors noted, “Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of LVAD [left ventricular assist device] therapy.”

In a previous study of people with end-stage heart failure, other investigators noted that, “despite the substantial survival benefit, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of the left ventricular assist device were considerable. In particular, infection and mechanical failure of the device were major factors in the 2-year survival rate of only 23%” (N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345[20]:1435-43).

Similarly, in the current study, mortality was higher among those with sepsis and a VAD. Mortality was 39% – including eight patients who died with a VAD in situ and one following cardiac transplantation. However, Dr. Das cautioned, “It’s a small number, and there are other factors that could have contributed. They all go on anticoagulants so they have bleeding tendencies, and many of the patients are in the ICU with multiorgan failure.”

Infection prevention remains paramount to minimize mortality and other adverse events associated with a patient’s having a VAD. “We have to make sure that infection control procedures and our treatments are up to the optimal standard,” Dr. Das said. “It’s not easy to remove the device.”

Of the 129 VADs implanted, 68 were long-term LVADs, 11 were short-term LVADs, 15 were right ventricular devices, and 35 were biventricular devices.

The study is ongoing. The data presented at the meeting were collected up until December 2016.

“Since then, I’ve seen two more cases, and – very interestingly – one was Haemophilus influenzae,” Dr. Das said. “The patient was on the device, he was at home, and he came in with bacteremia.” Again, the source of infection proved elusive. “With H. influenzae, you would think it was coming from his chest, but the chest x-ray was normal.”

The second case, a patient with a coagulase-negative staphylococci bloodstream infection, was scheduled for a PET scan at the time of Dr. Das’ presentation to try to identify the source of infection.

Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Back in 2008, there was only one case.

Since then, however, the number of patients with ventricular assist devices who developed sepsis while being treated in the cardiac unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, appeared to be noticeably growing. So, investigators launched a study to confirm their suspicions and to learn more about the underlying causes.

“Bloodstream infection is a serious infection, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what’s happening,’ ” explained Ira Das, MD, a consultant microbiologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common cause, present in 32% of the 25 cases. Sepsis was caused by Enterococcus faecium in 12%, Candida parapsilosis in 8%, and Staphylococcus aureus in 2%. Another 4% were either Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, C. guilliermondii, or C. orthopsilosis. The remaining 16% of bloodstream infections were polymicrobial.

Less certain was the source of these infections.

“In the majority of cases, we didn’t know where it was coming from,” Dr. Das said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. In 6 of the 25 cases, VAD was confirmed to be the focus of infection, either through imaging or because a failing component of the explanted device was examined later. An intravascular catheter was the source in another 5 patients, and in 14 cases, the source remained a mystery.

“Some of these infections just might have been hard to see,” Dr. Das said. “If the infection is inside the device, it’s not always easy to visualize.”

The study supports earlier findings from a review article that points to a significant infection risk associated with the implantation of VADs (Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 Sep;8[5]:627-34). That article’s authors noted, “Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of LVAD [left ventricular assist device] therapy.”

In a previous study of people with end-stage heart failure, other investigators noted that, “despite the substantial survival benefit, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of the left ventricular assist device were considerable. In particular, infection and mechanical failure of the device were major factors in the 2-year survival rate of only 23%” (N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345[20]:1435-43).

Similarly, in the current study, mortality was higher among those with sepsis and a VAD. Mortality was 39% – including eight patients who died with a VAD in situ and one following cardiac transplantation. However, Dr. Das cautioned, “It’s a small number, and there are other factors that could have contributed. They all go on anticoagulants so they have bleeding tendencies, and many of the patients are in the ICU with multiorgan failure.”

Infection prevention remains paramount to minimize mortality and other adverse events associated with a patient’s having a VAD. “We have to make sure that infection control procedures and our treatments are up to the optimal standard,” Dr. Das said. “It’s not easy to remove the device.”

Of the 129 VADs implanted, 68 were long-term LVADs, 11 were short-term LVADs, 15 were right ventricular devices, and 35 were biventricular devices.

The study is ongoing. The data presented at the meeting were collected up until December 2016.

“Since then, I’ve seen two more cases, and – very interestingly – one was Haemophilus influenzae,” Dr. Das said. “The patient was on the device, he was at home, and he came in with bacteremia.” Again, the source of infection proved elusive. “With H. influenzae, you would think it was coming from his chest, but the chest x-ray was normal.”

The second case, a patient with a coagulase-negative staphylococci bloodstream infection, was scheduled for a PET scan at the time of Dr. Das’ presentation to try to identify the source of infection.

Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point: There may be a significant rate of bloodstream infections among people with a ventricular assist device.

Major finding: A total of 20% of the 118 people with a VAD had a bloodstream infection.

Data source: A retrospective study of 129 ventricular assist devices placed in 118 people between 2008 and 2016.

Disclosures: Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

Factory contamination seen as likely source of postop endocarditis outbreak

Since 2013, over 100 cases of Mycobacterium chimaera prosthetic valve endocarditis and disseminated disease were detected in Europe and the United States, and these were presumptively linked to contaminated heater-cooler units (HCUs) used during cardiac surgery. A molecular epidemiological analysis of microbial isolate genomes detected a “remarkable clonality of isolates” in almost all of the assessed patients with M. chimaera disease, which “strongly points to a common source of infection,” as reported online in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The analysis comprised 250 whole-genome sequencing datasets: 24 isolates from 21 cardiac surgery–related patients in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; 36 from 35 unrelated patients; 126 from LivaNova HCUs in use (85 water cultures, 41 air cultures); 13 from LivaNova HCUs returned to the production site in Germany for disinfection; 4 from the LivaNova production site (3 from newly produced HCUs, 1 from a water source); 2 from Maquet extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) devices in use; 14 from Maquet HCUs in use; 15 from new Maquet HCUs sampled at the production site; and 7 from hospital water supplies in Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands, plus one M. chimaera DSM 44623–type strain, and eight M. intracellulare strains (from four unrelated patients from Germany and four published genomes).

Isolates were analyzed by next-generation whole-genome sequencing and compared with published M. chimaera genomes, according to Jakko van Ingen, PhD, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. Phylogenetic analysis of these 250 isolates revealed two major M. chimaera groups. They found that all cardiac surgery–related patient isolates could be classified into group 1. They then did a subgroup analysis.

“Three distinct strains of M. chimaera appear to have contaminated the water systems of LivaNova HCUs at the production site, belonging to subgroups 1.1, 1.8, and 2.1,” the authors stated. However, most M. chimaera isolates from air samples taken near operating LivaNova HCUs and those of 23 of the 24 related patients belonged to subgroup 1.1.

“This finding further supports the presumed airborne transmission pathway leading to endocarditis, aortic graft infection, disseminated disease, and surgical site infections in the affected patients,” according to the authors (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[17]30324-9).

The results suggest “the possibility that the vast majority of cases of cardiothoracic surgery–related severe M. chimaera infections diagnosed in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia resulted from a single common source of infection: LivaNova HCUs that were most likely contaminated during production in Germany,” the researchers concluded.

The study was partly funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program, its FP7 program, the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, and National Institute of Health Research Oxford Health Protection Research Units on Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts.

Since 2013, over 100 cases of Mycobacterium chimaera prosthetic valve endocarditis and disseminated disease were detected in Europe and the United States, and these were presumptively linked to contaminated heater-cooler units (HCUs) used during cardiac surgery. A molecular epidemiological analysis of microbial isolate genomes detected a “remarkable clonality of isolates” in almost all of the assessed patients with M. chimaera disease, which “strongly points to a common source of infection,” as reported online in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The analysis comprised 250 whole-genome sequencing datasets: 24 isolates from 21 cardiac surgery–related patients in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; 36 from 35 unrelated patients; 126 from LivaNova HCUs in use (85 water cultures, 41 air cultures); 13 from LivaNova HCUs returned to the production site in Germany for disinfection; 4 from the LivaNova production site (3 from newly produced HCUs, 1 from a water source); 2 from Maquet extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) devices in use; 14 from Maquet HCUs in use; 15 from new Maquet HCUs sampled at the production site; and 7 from hospital water supplies in Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands, plus one M. chimaera DSM 44623–type strain, and eight M. intracellulare strains (from four unrelated patients from Germany and four published genomes).

Isolates were analyzed by next-generation whole-genome sequencing and compared with published M. chimaera genomes, according to Jakko van Ingen, PhD, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. Phylogenetic analysis of these 250 isolates revealed two major M. chimaera groups. They found that all cardiac surgery–related patient isolates could be classified into group 1. They then did a subgroup analysis.

“Three distinct strains of M. chimaera appear to have contaminated the water systems of LivaNova HCUs at the production site, belonging to subgroups 1.1, 1.8, and 2.1,” the authors stated. However, most M. chimaera isolates from air samples taken near operating LivaNova HCUs and those of 23 of the 24 related patients belonged to subgroup 1.1.

“This finding further supports the presumed airborne transmission pathway leading to endocarditis, aortic graft infection, disseminated disease, and surgical site infections in the affected patients,” according to the authors (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[17]30324-9).

The results suggest “the possibility that the vast majority of cases of cardiothoracic surgery–related severe M. chimaera infections diagnosed in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia resulted from a single common source of infection: LivaNova HCUs that were most likely contaminated during production in Germany,” the researchers concluded.

The study was partly funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program, its FP7 program, the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, and National Institute of Health Research Oxford Health Protection Research Units on Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts.

Since 2013, over 100 cases of Mycobacterium chimaera prosthetic valve endocarditis and disseminated disease were detected in Europe and the United States, and these were presumptively linked to contaminated heater-cooler units (HCUs) used during cardiac surgery. A molecular epidemiological analysis of microbial isolate genomes detected a “remarkable clonality of isolates” in almost all of the assessed patients with M. chimaera disease, which “strongly points to a common source of infection,” as reported online in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The analysis comprised 250 whole-genome sequencing datasets: 24 isolates from 21 cardiac surgery–related patients in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; 36 from 35 unrelated patients; 126 from LivaNova HCUs in use (85 water cultures, 41 air cultures); 13 from LivaNova HCUs returned to the production site in Germany for disinfection; 4 from the LivaNova production site (3 from newly produced HCUs, 1 from a water source); 2 from Maquet extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) devices in use; 14 from Maquet HCUs in use; 15 from new Maquet HCUs sampled at the production site; and 7 from hospital water supplies in Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands, plus one M. chimaera DSM 44623–type strain, and eight M. intracellulare strains (from four unrelated patients from Germany and four published genomes).

Isolates were analyzed by next-generation whole-genome sequencing and compared with published M. chimaera genomes, according to Jakko van Ingen, PhD, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. Phylogenetic analysis of these 250 isolates revealed two major M. chimaera groups. They found that all cardiac surgery–related patient isolates could be classified into group 1. They then did a subgroup analysis.

“Three distinct strains of M. chimaera appear to have contaminated the water systems of LivaNova HCUs at the production site, belonging to subgroups 1.1, 1.8, and 2.1,” the authors stated. However, most M. chimaera isolates from air samples taken near operating LivaNova HCUs and those of 23 of the 24 related patients belonged to subgroup 1.1.

“This finding further supports the presumed airborne transmission pathway leading to endocarditis, aortic graft infection, disseminated disease, and surgical site infections in the affected patients,” according to the authors (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[17]30324-9).

The results suggest “the possibility that the vast majority of cases of cardiothoracic surgery–related severe M. chimaera infections diagnosed in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia resulted from a single common source of infection: LivaNova HCUs that were most likely contaminated during production in Germany,” the researchers concluded.

The study was partly funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program, its FP7 program, the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, and National Institute of Health Research Oxford Health Protection Research Units on Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Cardiac surgery–related patient isolates were all classified into the same group, in which all, except one, formed a distinct subgroup of Mycobacterium chimaera, which also comprised most isolates from LivaNova HCUs, and one from the equipment production site.

Data source: Phylogenetic analysis based on whole-genome sequencing of 250 M. chimaera isolates obtained from cardiac surgery patients, hospitals, and other sources.

Disclosures: Partly funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program and several German, Swiss, and U.K. infectious disease–related NGOs. The authors reported having no disclosures.

Recovery: Where TAVR gains advantage over SAVR

A post hoc analysis of the first randomized clinical to show the superiority of an interventional technique for aortic valve repair over surgery in terms of postoperative death has found the period of 30 days to 4 months after the procedure to be the most perilous for surgery patients, when their risk of death was almost twice that of interventional patients, likely because surgery patients were more vulnerable to complications and were less likely to go home after the procedure.

“This mortality difference was largely driven by higher rates of technical failure, surgical complications, and lack of recovery following surgery,” said Vincent A. Gaudiani, MD, of El Camino Hospital, Mountain View, Calif., and his coauthors (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1293-99). The analysis investigated causes and timing of death in the CoreValve US Pivotal High-Risk Trial, a randomized, high-risk trial of the CoreValve self-expanding bioprosthesis (Medtronic). The trial favored transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) over surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

The post hoc analysis evaluated all-cause mortality through the first year based on three time periods: early, up to 30 days; recovery, 31-120 days; and late, 121-365 days. Death rates for the two procedures were similar in the early and late postoperative periods, but deviated significantly in the recovery period: 4% for TAVR vs. 7.9% for SAVR (P = .25). SAVR patients were more likely affected by the overall influence of physical stress associated with surgery, the study found, whereas rates of technical failure and complications were similar between the two groups. “This suggests that early TAVR results can improve with technical refinements and that high-risk surgical patients will benefit from reducing complications,” wrote Dr. Gaudiani and his coauthors.

They noted the CoreValve trial findings, in terms of the survival differences between TAVR and SAVR, are significant because previous trials that compared TAVR and SAVR, including the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves A trial (Lancet. 2015;385:2477-84), showed equivalent survival between the two procedures at up to 5 years. “This unique finding is provocative and the reason for this survival difference is important to understanding TAVR and SAVR and improving both therapies,” said Dr. Gaudiani and his coauthors.

While SAVR patients had a higher overall death rate in the recovery period, TAVR patients had a larger proportion of cardiovascular deaths – 12 of 15 (80%) vs. 16 of 27 (59.3%) for SAVR. The leading noncardiovascular cause of death in the SAVR group was sepsis (six), followed by malignancy (one), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (one) and other (three). “Although these deaths were adjudicated as noncardiovascular by the CEC [clinical events committee], our review showed that some of these patients had never really recovered from the initial procedure,” the researchers wrote.

In the early period, death rates were 3.3% for TAVR and 4.5% for SAVR, a nonsignificant difference. TAVR patients who died had higher rates of peripheral vascular disease and recent falls; SAVR patients who died were more likely to have had a pacemaker. In the late period, the death rates were 7.5% for TAVR and 7.7% for SAVR, and the researchers also found no significant difference in the number of cardiovascular deaths (4.4% and 4.2%, respectively). “Hierarchical causes of death were primarily due to other reasons deemed unrelated to the initial aortic valve replacement,” noted Dr. Gaudiani and his coauthors.

However, the study also found that TAVR patients were significantly more likely to go home after hospital discharge rather than to a rehabilitation facility or another hospital – 66.9% vs. 39.7% (P less than .001).

In the SAVR group, five cardiovascular deaths in the recovery period occurred because the operation failed to correct aortic stenosis – all related to placement of a valve too small for the patient. “Placing a valve appropriately sized to the patient should be a priority for surgeons if we are to improve our outcomes,” the researchers noted. “Most other deaths were the result of patients’ inability to cope with the physical trauma of surgery.”

Dr. Gaudiani disclosed that he is a consultant and paid instructor for Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, and Edwards Lifesciences. Coauthors disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, Terumo, Gore Medical, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and other device companies.

In his invited discussion, Craig R. Smith, MD, of New York, noted that comparisons “are odious” and that comparing clinical trials requires caution. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1300-1) He also acknowledged that surgeons would hope for evidence that the findings of the CoreValve US Pivotal High-Risk Trial were somehow wrong.

Dr. Smith raised a question about the CoreValve trial, which was designed to enroll high-risk patients, “but actually enrolled at the upper end of the intermediate risk range with a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score of 7.4 versus 11.3 in the high-risk PARTNER 1.” However, he noted that it would not be fair to consider the self-expanding TAVR trial intermediate risk, because the intermediate risk PARTNER 2 trial had an STS score of 5.8. And while outcomes for SAVR in the CoreValve trial were within the expected variable of less than 1 using the STS Predicted Risk for Mortality, the “bulge” of deaths in the recovery phase raises “a whiff of concern.”

Dr. Smith said that the early technical mortalities with TAVR in the trial are already disappearing with experience. He also noted that Dr. Gaudiani and his coauthors pointed out the frequency of failure to repair and failure to recover. “Whether competing against TAVR in a randomized trial or operating on TAVR in eligible patients in the future, as the authors have emphasized, it behooves us to correct the problem as completely as possible and take the best possible care of our patients afterward,” Dr. Smith said. He also noted the difference in discharge rates home “illustrates a very significant advantage of TAVR.”

Dr. Smith disclosed he has received reimbursement for expenses in his leadership role in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trials.

In his invited discussion, Craig R. Smith, MD, of New York, noted that comparisons “are odious” and that comparing clinical trials requires caution. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1300-1) He also acknowledged that surgeons would hope for evidence that the findings of the CoreValve US Pivotal High-Risk Trial were somehow wrong.

Dr. Smith raised a question about the CoreValve trial, which was designed to enroll high-risk patients, “but actually enrolled at the upper end of the intermediate risk range with a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score of 7.4 versus 11.3 in the high-risk PARTNER 1.” However, he noted that it would not be fair to consider the self-expanding TAVR trial intermediate risk, because the intermediate risk PARTNER 2 trial had an STS score of 5.8. And while outcomes for SAVR in the CoreValve trial were within the expected variable of less than 1 using the STS Predicted Risk for Mortality, the “bulge” of deaths in the recovery phase raises “a whiff of concern.”

Dr. Smith said that the early technical mortalities with TAVR in the trial are already disappearing with experience. He also noted that Dr. Gaudiani and his coauthors pointed out the frequency of failure to repair and failure to recover. “Whether competing against TAVR in a randomized trial or operating on TAVR in eligible patients in the future, as the authors have emphasized, it behooves us to correct the problem as completely as possible and take the best possible care of our patients afterward,” Dr. Smith said. He also noted the difference in discharge rates home “illustrates a very significant advantage of TAVR.”

Dr. Smith disclosed he has received reimbursement for expenses in his leadership role in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trials.

In his invited discussion, Craig R. Smith, MD, of New York, noted that comparisons “are odious” and that comparing clinical trials requires caution. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1300-1) He also acknowledged that surgeons would hope for evidence that the findings of the CoreValve US Pivotal High-Risk Trial were somehow wrong.

Dr. Smith raised a question about the CoreValve trial, which was designed to enroll high-risk patients, “but actually enrolled at the upper end of the intermediate risk range with a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score of 7.4 versus 11.3 in the high-risk PARTNER 1.” However, he noted that it would not be fair to consider the self-expanding TAVR trial intermediate risk, because the intermediate risk PARTNER 2 trial had an STS score of 5.8. And while outcomes for SAVR in the CoreValve trial were within the expected variable of less than 1 using the STS Predicted Risk for Mortality, the “bulge” of deaths in the recovery phase raises “a whiff of concern.”

Dr. Smith said that the early technical mortalities with TAVR in the trial are already disappearing with experience. He also noted that Dr. Gaudiani and his coauthors pointed out the frequency of failure to repair and failure to recover. “Whether competing against TAVR in a randomized trial or operating on TAVR in eligible patients in the future, as the authors have emphasized, it behooves us to correct the problem as completely as possible and take the best possible care of our patients afterward,” Dr. Smith said. He also noted the difference in discharge rates home “illustrates a very significant advantage of TAVR.”

Dr. Smith disclosed he has received reimbursement for expenses in his leadership role in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trials.

A post hoc analysis of the first randomized clinical to show the superiority of an interventional technique for aortic valve repair over surgery in terms of postoperative death has found the period of 30 days to 4 months after the procedure to be the most perilous for surgery patients, when their risk of death was almost twice that of interventional patients, likely because surgery patients were more vulnerable to complications and were less likely to go home after the procedure.