User login

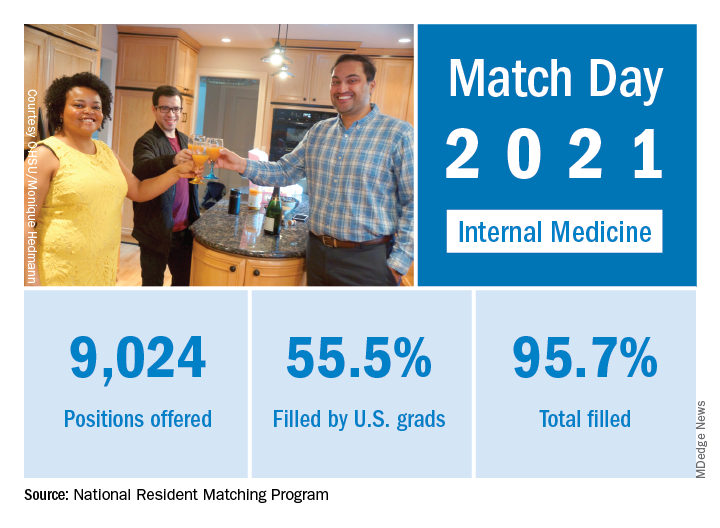

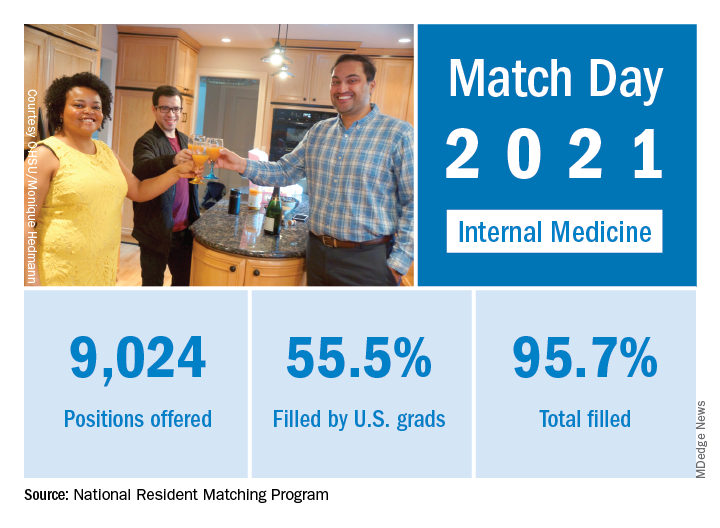

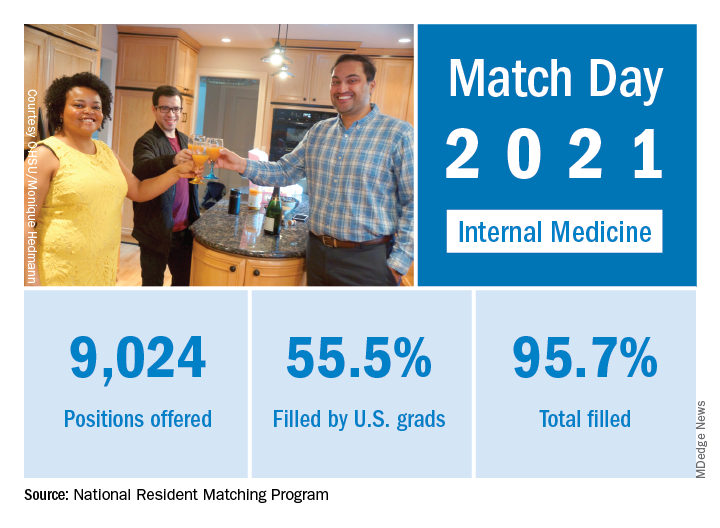

Match Day 2021: Internal medicine keeps growing

according to the National Resident Matching Program.

“Rather than faltering in these uncertain times, program fill rates increased across the board,” the NRMP said in a written statement. Overall, the 2021 Main Residency Match offered (35,194) and filled (33,353) record numbers of first-year (PGY-1) slots. That fill rate of 94.8% was up from 94.6% the year before.

“The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” said Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, president and CEO of the NRMP.

Internal medicine offered 9,024 positions in this year’s Match, up by 3.8% over 2020, and filled 8,632, for a 1-year increase of 3.7% and a fill rate of 95.7%. Over 55% (5,005) of the available slots were given to U.S. seniors (MDs and DOs), while 37.9% went to international medical graduates. The corresponding PGY-1 numbers for the Match as a whole were 70.4% U.S. and 21.1% international medical graduates, based on NRMP data.

The number of positions offered in internal medicine residencies has increased by 1,791 (24.8%) since 2017, and such growth over time may “be a predictor of future physician workforce supply,” the NRMP suggested. Internal medicine also increased its share of all available residency positions from 24.9% in 2018 to 25.6% in 2021.

“Concerns about the impact of virtual recruitment on applicants’ matching into PGY-1 positions were not realized,” the NRMP noted, as “growth in registration was seen in every applicant group.” Compared with 2020, submissions of rank-order lists of programs were up by 2.8% for U.S. MD seniors, 7.9% for U.S. DO seniors, 2.5% among U.S.-citizen IMGs, and 15.0% for non–U.S.-citizen IMGs.

“The internal medicine workforce remains the backbone of our health care system, and expansion of this workforce is imperative to provide access to specialty and subspecialty medical care for future patients,” Philip A. Masters, MD, vice president of membership and global engagement at the American College of Physicians, said in a separate statement.

according to the National Resident Matching Program.

“Rather than faltering in these uncertain times, program fill rates increased across the board,” the NRMP said in a written statement. Overall, the 2021 Main Residency Match offered (35,194) and filled (33,353) record numbers of first-year (PGY-1) slots. That fill rate of 94.8% was up from 94.6% the year before.

“The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” said Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, president and CEO of the NRMP.

Internal medicine offered 9,024 positions in this year’s Match, up by 3.8% over 2020, and filled 8,632, for a 1-year increase of 3.7% and a fill rate of 95.7%. Over 55% (5,005) of the available slots were given to U.S. seniors (MDs and DOs), while 37.9% went to international medical graduates. The corresponding PGY-1 numbers for the Match as a whole were 70.4% U.S. and 21.1% international medical graduates, based on NRMP data.

The number of positions offered in internal medicine residencies has increased by 1,791 (24.8%) since 2017, and such growth over time may “be a predictor of future physician workforce supply,” the NRMP suggested. Internal medicine also increased its share of all available residency positions from 24.9% in 2018 to 25.6% in 2021.

“Concerns about the impact of virtual recruitment on applicants’ matching into PGY-1 positions were not realized,” the NRMP noted, as “growth in registration was seen in every applicant group.” Compared with 2020, submissions of rank-order lists of programs were up by 2.8% for U.S. MD seniors, 7.9% for U.S. DO seniors, 2.5% among U.S.-citizen IMGs, and 15.0% for non–U.S.-citizen IMGs.

“The internal medicine workforce remains the backbone of our health care system, and expansion of this workforce is imperative to provide access to specialty and subspecialty medical care for future patients,” Philip A. Masters, MD, vice president of membership and global engagement at the American College of Physicians, said in a separate statement.

according to the National Resident Matching Program.

“Rather than faltering in these uncertain times, program fill rates increased across the board,” the NRMP said in a written statement. Overall, the 2021 Main Residency Match offered (35,194) and filled (33,353) record numbers of first-year (PGY-1) slots. That fill rate of 94.8% was up from 94.6% the year before.

“The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” said Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, president and CEO of the NRMP.

Internal medicine offered 9,024 positions in this year’s Match, up by 3.8% over 2020, and filled 8,632, for a 1-year increase of 3.7% and a fill rate of 95.7%. Over 55% (5,005) of the available slots were given to U.S. seniors (MDs and DOs), while 37.9% went to international medical graduates. The corresponding PGY-1 numbers for the Match as a whole were 70.4% U.S. and 21.1% international medical graduates, based on NRMP data.

The number of positions offered in internal medicine residencies has increased by 1,791 (24.8%) since 2017, and such growth over time may “be a predictor of future physician workforce supply,” the NRMP suggested. Internal medicine also increased its share of all available residency positions from 24.9% in 2018 to 25.6% in 2021.

“Concerns about the impact of virtual recruitment on applicants’ matching into PGY-1 positions were not realized,” the NRMP noted, as “growth in registration was seen in every applicant group.” Compared with 2020, submissions of rank-order lists of programs were up by 2.8% for U.S. MD seniors, 7.9% for U.S. DO seniors, 2.5% among U.S.-citizen IMGs, and 15.0% for non–U.S.-citizen IMGs.

“The internal medicine workforce remains the backbone of our health care system, and expansion of this workforce is imperative to provide access to specialty and subspecialty medical care for future patients,” Philip A. Masters, MD, vice president of membership and global engagement at the American College of Physicians, said in a separate statement.

How to predict successful colonoscopy malpractice lawsuits

Malpractice lawsuits related to colonoscopy continue to pose challenges for practitioners, and a new analysis reveals that errors related to sedation are more likely to be awarded to plaintiffs. Primary care physicians and surgeons are often codefendants, which emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary care in colonoscopy.

Cases involving informed consent were more likely to be ruled for the defendant, while those tied to medication error favored the plaintiff, according to an analysis of cases from the Westlaw legal database. The study, led by Krishan S. Patel and Sushil Ahlawat of Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

According to the authors, 55% of physicians face a malpractice suit at some point in their careers, and gastroenterology ranks as the sixth most common specialty named in malpractice suits. Every year, about 13% of gastroenterologists confront malpractice allegations, and colonoscopy is the most common reason.

The researchers searched the Westlaw legal database for malpractice cases involving colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, identifying 305 cases between 1980 and 2017. The average patient age was 54.9 years, and 52.8% of cases were brought by female patients. The most cases were from New York (21.0%), followed by California (13.4%), Pennsylvania (13.1%), Massachusetts (12.5%), and New Jersey (7.9%). Gastroenterologists were named in 71.1% of cases, internists in 25.6%, and surgeons in 14.8%.

A little more than half (51.8%) of cases were ruled in favor of the defendant, and 25% for the plaintiff; 17% were settled, and 6% had a mixed outcome. Payouts ranged from $30,000 to $500,000,000, with a median of $995,000.

There were multiple causes of litigation listed in 83.6% of cases. The most frequent causes were delayed treatment (65.9%), delayed diagnosis (65.6%), procedural error/negligence (44.3%), and failure to refer/reorder tests (25.6%).

Of 135 cases alleging procedural negligence, 90 (67%) named perforation. Among 79 cases that cited a failure to refer and order appropriate tests, 97% claimed the defendant missed a cancerous lesion. In cases alleging missed cancers, 31% were in the cecum, and 23% in the anus.

A logistic regression analysis of factors associated with a verdict for the defendant found “lack of informed consent” to be an independent predictor of defendant verdict (odds ratio, 4.05; P = .004). “Medication error” was associated with reduced defendant success (OR, 0.17; P=.023). There were nonsignificant trends between reduced odds of a verdict for the defendant and lawsuits that named “delay in diagnosis” (OR, 0.35; P = .060) and “failure to refer” (OR, 0.51; P = .074).

The authors sound a dire note about the number of malpractice suits brought against gastroenterologists, but Lawrence Kosinski, MD, is more sanguine. He notes that gastroenterologists have low insurance premiums, compared with other specialties, but recognizes that colonoscopies are a significant source of risk.

Dr. Kosinski, who is chief medical officer at SonarMD and formerly a managing partner at the Illinois Gastroenterology Group, said in an interview that the study is revealing. “It comes out in the article: Acts of omission are more dangerous to the physician than acts of commission. Not finding that cancer, not acting on that malignant polyp, not pursuing it, is much more likely to get you in trouble than taking it off and perforating a colon,” said Dr. Kosinski, who was not involved in the study.

To gastroenterologists seeking to reduce their risks, he offered advice: You shouldn’t assume that the patient has read the information provided. Risks of anesthesia and the procedure should be directly communicated. It’s also important to document the procedure, including pictures of the cecum and rectal retroflexion. Finally, don’t rush. “This isn’t a race. Clean the colon, make sure you don’t miss something. If that person pops up in 3 years with a cancer, someone may go after you,” said Dr. Kosinski.

No source of funding was disclosed. Dr. Kosinski has no relevant financial disclosures.

Malpractice lawsuits related to colonoscopy continue to pose challenges for practitioners, and a new analysis reveals that errors related to sedation are more likely to be awarded to plaintiffs. Primary care physicians and surgeons are often codefendants, which emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary care in colonoscopy.

Cases involving informed consent were more likely to be ruled for the defendant, while those tied to medication error favored the plaintiff, according to an analysis of cases from the Westlaw legal database. The study, led by Krishan S. Patel and Sushil Ahlawat of Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

According to the authors, 55% of physicians face a malpractice suit at some point in their careers, and gastroenterology ranks as the sixth most common specialty named in malpractice suits. Every year, about 13% of gastroenterologists confront malpractice allegations, and colonoscopy is the most common reason.

The researchers searched the Westlaw legal database for malpractice cases involving colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, identifying 305 cases between 1980 and 2017. The average patient age was 54.9 years, and 52.8% of cases were brought by female patients. The most cases were from New York (21.0%), followed by California (13.4%), Pennsylvania (13.1%), Massachusetts (12.5%), and New Jersey (7.9%). Gastroenterologists were named in 71.1% of cases, internists in 25.6%, and surgeons in 14.8%.

A little more than half (51.8%) of cases were ruled in favor of the defendant, and 25% for the plaintiff; 17% were settled, and 6% had a mixed outcome. Payouts ranged from $30,000 to $500,000,000, with a median of $995,000.

There were multiple causes of litigation listed in 83.6% of cases. The most frequent causes were delayed treatment (65.9%), delayed diagnosis (65.6%), procedural error/negligence (44.3%), and failure to refer/reorder tests (25.6%).

Of 135 cases alleging procedural negligence, 90 (67%) named perforation. Among 79 cases that cited a failure to refer and order appropriate tests, 97% claimed the defendant missed a cancerous lesion. In cases alleging missed cancers, 31% were in the cecum, and 23% in the anus.

A logistic regression analysis of factors associated with a verdict for the defendant found “lack of informed consent” to be an independent predictor of defendant verdict (odds ratio, 4.05; P = .004). “Medication error” was associated with reduced defendant success (OR, 0.17; P=.023). There were nonsignificant trends between reduced odds of a verdict for the defendant and lawsuits that named “delay in diagnosis” (OR, 0.35; P = .060) and “failure to refer” (OR, 0.51; P = .074).

The authors sound a dire note about the number of malpractice suits brought against gastroenterologists, but Lawrence Kosinski, MD, is more sanguine. He notes that gastroenterologists have low insurance premiums, compared with other specialties, but recognizes that colonoscopies are a significant source of risk.

Dr. Kosinski, who is chief medical officer at SonarMD and formerly a managing partner at the Illinois Gastroenterology Group, said in an interview that the study is revealing. “It comes out in the article: Acts of omission are more dangerous to the physician than acts of commission. Not finding that cancer, not acting on that malignant polyp, not pursuing it, is much more likely to get you in trouble than taking it off and perforating a colon,” said Dr. Kosinski, who was not involved in the study.

To gastroenterologists seeking to reduce their risks, he offered advice: You shouldn’t assume that the patient has read the information provided. Risks of anesthesia and the procedure should be directly communicated. It’s also important to document the procedure, including pictures of the cecum and rectal retroflexion. Finally, don’t rush. “This isn’t a race. Clean the colon, make sure you don’t miss something. If that person pops up in 3 years with a cancer, someone may go after you,” said Dr. Kosinski.

No source of funding was disclosed. Dr. Kosinski has no relevant financial disclosures.

Malpractice lawsuits related to colonoscopy continue to pose challenges for practitioners, and a new analysis reveals that errors related to sedation are more likely to be awarded to plaintiffs. Primary care physicians and surgeons are often codefendants, which emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary care in colonoscopy.

Cases involving informed consent were more likely to be ruled for the defendant, while those tied to medication error favored the plaintiff, according to an analysis of cases from the Westlaw legal database. The study, led by Krishan S. Patel and Sushil Ahlawat of Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

According to the authors, 55% of physicians face a malpractice suit at some point in their careers, and gastroenterology ranks as the sixth most common specialty named in malpractice suits. Every year, about 13% of gastroenterologists confront malpractice allegations, and colonoscopy is the most common reason.

The researchers searched the Westlaw legal database for malpractice cases involving colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, identifying 305 cases between 1980 and 2017. The average patient age was 54.9 years, and 52.8% of cases were brought by female patients. The most cases were from New York (21.0%), followed by California (13.4%), Pennsylvania (13.1%), Massachusetts (12.5%), and New Jersey (7.9%). Gastroenterologists were named in 71.1% of cases, internists in 25.6%, and surgeons in 14.8%.

A little more than half (51.8%) of cases were ruled in favor of the defendant, and 25% for the plaintiff; 17% were settled, and 6% had a mixed outcome. Payouts ranged from $30,000 to $500,000,000, with a median of $995,000.

There were multiple causes of litigation listed in 83.6% of cases. The most frequent causes were delayed treatment (65.9%), delayed diagnosis (65.6%), procedural error/negligence (44.3%), and failure to refer/reorder tests (25.6%).

Of 135 cases alleging procedural negligence, 90 (67%) named perforation. Among 79 cases that cited a failure to refer and order appropriate tests, 97% claimed the defendant missed a cancerous lesion. In cases alleging missed cancers, 31% were in the cecum, and 23% in the anus.

A logistic regression analysis of factors associated with a verdict for the defendant found “lack of informed consent” to be an independent predictor of defendant verdict (odds ratio, 4.05; P = .004). “Medication error” was associated with reduced defendant success (OR, 0.17; P=.023). There were nonsignificant trends between reduced odds of a verdict for the defendant and lawsuits that named “delay in diagnosis” (OR, 0.35; P = .060) and “failure to refer” (OR, 0.51; P = .074).

The authors sound a dire note about the number of malpractice suits brought against gastroenterologists, but Lawrence Kosinski, MD, is more sanguine. He notes that gastroenterologists have low insurance premiums, compared with other specialties, but recognizes that colonoscopies are a significant source of risk.

Dr. Kosinski, who is chief medical officer at SonarMD and formerly a managing partner at the Illinois Gastroenterology Group, said in an interview that the study is revealing. “It comes out in the article: Acts of omission are more dangerous to the physician than acts of commission. Not finding that cancer, not acting on that malignant polyp, not pursuing it, is much more likely to get you in trouble than taking it off and perforating a colon,” said Dr. Kosinski, who was not involved in the study.

To gastroenterologists seeking to reduce their risks, he offered advice: You shouldn’t assume that the patient has read the information provided. Risks of anesthesia and the procedure should be directly communicated. It’s also important to document the procedure, including pictures of the cecum and rectal retroflexion. Finally, don’t rush. “This isn’t a race. Clean the colon, make sure you don’t miss something. If that person pops up in 3 years with a cancer, someone may go after you,” said Dr. Kosinski.

No source of funding was disclosed. Dr. Kosinski has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Internists least likely to choose their specialty again, survey shows

Internists spent an average of 18.5 hours per week on paperwork, according to the Medscape Internist Compensation Report 2020. That number was surpassed only by intensivists, who spent 19.1 hours on such tasks.

Although that number was up $8,000 from last year, it was still less than half that of the top-earning specialists.

The top four specialties in terms of pay were the same this year as they were last year and ranked in the same order: orthopedists made the most, at $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000).

However, internists ranked in the middle of all physicians as to feeling fairly compensated. Just more than half (52%) reported they were fairly compensated, compared with 67% of oncologists, emergency medicine physicians, and radiologists, who were at the top of the ranking, and 44% of nephrologists, who were on the low end.

Also, just as last year, male internists earned 23% more than their female colleagues, which is a slightly smaller pay gap than the 31% gap seen overall.

COVID-19 reversing income gains

However, the compensation picture is changing for all physicians. This report reflects data gathered between Oct. 4, 2019, and Feb. 10, 2020. Since that time, the COVID-19 crisis has reversed income gains for physicians overall. A study from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) indicates that more than half of medical practices reported a drop in revenue by early April of 55% and a drop in patient volume of 60%.

The MGMA noted, “Practices are struggling to stay afloat – and many fear that this is only the beginning.”

Specialty choice may vary

In the Medscape survey, internists were the physicians least likely to say they would choose their specialty again. Only 66% said they would choose it again, compared with the most enthusiastic specialists: orthopedists (97%), oncologists (96%), and ophthalmologists and dermatologists (both at 95%).

However, three-fourths of internists (75%) said they would choose medicine again, which was a larger proportion than that reported by family physicians (74%), neurologists (73%), and plastic surgeons (72%).

This year’s Medscape survey is the first to ask about incentive bonuses. More than half of all physicians (56%) reported receiving one. Bonuses for internists ranked near the bottom, at an average of $27,000. Orthopedists averaged $96,000 bonuses, and family physicians received the least, at an average of $24,000.

Most internists (63%) said their bonus had no effect on the number of hours worked, which was similar to physicians in other specialties.

In good news, internists lost less money on claims that were denied or that required resubmission than most of their colleagues in other specialties. By comparison, internists reported losing 15% on such claims, and plastic surgeons lost almost twice that percentage (28%).

The survey authors noted, “One study found that, on average, 63% of denied claims are recoverable, but healthcare professionals spend about $118 per claim on appeals.”

Relationships with patients most rewarding

When asked about the most rewarding part of their job, internists ranked “gratitude/relationships with patients” at the top. In this survey, internists spent about the same amount of time with patients that all physicians spent with patients on average, 37.9 hours per week.

“Making good money at a job I like” was the fourth-biggest driver of satisfaction (only 11% said that was the most rewarding part), behind “being very good at what I do/finding answers, diagnoses” and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”

Some questions on the survey pertained to the use of advanced practice providers. More than half of internists (54%) reported their practice included nurse practitioners (NPs), and 36% included physician assistants (PAs); 37% employed neither.

Half of the internists who employed NPs and PAs said they had no effect on profitability, 44% said they increased it, and 6% said they decreased it. Physicians overall were split (47% each) on whether NPs and PAs increased profitability or had no effect on it.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Internists spent an average of 18.5 hours per week on paperwork, according to the Medscape Internist Compensation Report 2020. That number was surpassed only by intensivists, who spent 19.1 hours on such tasks.

Although that number was up $8,000 from last year, it was still less than half that of the top-earning specialists.

The top four specialties in terms of pay were the same this year as they were last year and ranked in the same order: orthopedists made the most, at $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000).

However, internists ranked in the middle of all physicians as to feeling fairly compensated. Just more than half (52%) reported they were fairly compensated, compared with 67% of oncologists, emergency medicine physicians, and radiologists, who were at the top of the ranking, and 44% of nephrologists, who were on the low end.

Also, just as last year, male internists earned 23% more than their female colleagues, which is a slightly smaller pay gap than the 31% gap seen overall.

COVID-19 reversing income gains

However, the compensation picture is changing for all physicians. This report reflects data gathered between Oct. 4, 2019, and Feb. 10, 2020. Since that time, the COVID-19 crisis has reversed income gains for physicians overall. A study from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) indicates that more than half of medical practices reported a drop in revenue by early April of 55% and a drop in patient volume of 60%.

The MGMA noted, “Practices are struggling to stay afloat – and many fear that this is only the beginning.”

Specialty choice may vary

In the Medscape survey, internists were the physicians least likely to say they would choose their specialty again. Only 66% said they would choose it again, compared with the most enthusiastic specialists: orthopedists (97%), oncologists (96%), and ophthalmologists and dermatologists (both at 95%).

However, three-fourths of internists (75%) said they would choose medicine again, which was a larger proportion than that reported by family physicians (74%), neurologists (73%), and plastic surgeons (72%).

This year’s Medscape survey is the first to ask about incentive bonuses. More than half of all physicians (56%) reported receiving one. Bonuses for internists ranked near the bottom, at an average of $27,000. Orthopedists averaged $96,000 bonuses, and family physicians received the least, at an average of $24,000.

Most internists (63%) said their bonus had no effect on the number of hours worked, which was similar to physicians in other specialties.

In good news, internists lost less money on claims that were denied or that required resubmission than most of their colleagues in other specialties. By comparison, internists reported losing 15% on such claims, and plastic surgeons lost almost twice that percentage (28%).

The survey authors noted, “One study found that, on average, 63% of denied claims are recoverable, but healthcare professionals spend about $118 per claim on appeals.”

Relationships with patients most rewarding

When asked about the most rewarding part of their job, internists ranked “gratitude/relationships with patients” at the top. In this survey, internists spent about the same amount of time with patients that all physicians spent with patients on average, 37.9 hours per week.

“Making good money at a job I like” was the fourth-biggest driver of satisfaction (only 11% said that was the most rewarding part), behind “being very good at what I do/finding answers, diagnoses” and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”

Some questions on the survey pertained to the use of advanced practice providers. More than half of internists (54%) reported their practice included nurse practitioners (NPs), and 36% included physician assistants (PAs); 37% employed neither.

Half of the internists who employed NPs and PAs said they had no effect on profitability, 44% said they increased it, and 6% said they decreased it. Physicians overall were split (47% each) on whether NPs and PAs increased profitability or had no effect on it.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Internists spent an average of 18.5 hours per week on paperwork, according to the Medscape Internist Compensation Report 2020. That number was surpassed only by intensivists, who spent 19.1 hours on such tasks.

Although that number was up $8,000 from last year, it was still less than half that of the top-earning specialists.

The top four specialties in terms of pay were the same this year as they were last year and ranked in the same order: orthopedists made the most, at $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000).

However, internists ranked in the middle of all physicians as to feeling fairly compensated. Just more than half (52%) reported they were fairly compensated, compared with 67% of oncologists, emergency medicine physicians, and radiologists, who were at the top of the ranking, and 44% of nephrologists, who were on the low end.

Also, just as last year, male internists earned 23% more than their female colleagues, which is a slightly smaller pay gap than the 31% gap seen overall.

COVID-19 reversing income gains

However, the compensation picture is changing for all physicians. This report reflects data gathered between Oct. 4, 2019, and Feb. 10, 2020. Since that time, the COVID-19 crisis has reversed income gains for physicians overall. A study from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) indicates that more than half of medical practices reported a drop in revenue by early April of 55% and a drop in patient volume of 60%.

The MGMA noted, “Practices are struggling to stay afloat – and many fear that this is only the beginning.”

Specialty choice may vary

In the Medscape survey, internists were the physicians least likely to say they would choose their specialty again. Only 66% said they would choose it again, compared with the most enthusiastic specialists: orthopedists (97%), oncologists (96%), and ophthalmologists and dermatologists (both at 95%).

However, three-fourths of internists (75%) said they would choose medicine again, which was a larger proportion than that reported by family physicians (74%), neurologists (73%), and plastic surgeons (72%).

This year’s Medscape survey is the first to ask about incentive bonuses. More than half of all physicians (56%) reported receiving one. Bonuses for internists ranked near the bottom, at an average of $27,000. Orthopedists averaged $96,000 bonuses, and family physicians received the least, at an average of $24,000.

Most internists (63%) said their bonus had no effect on the number of hours worked, which was similar to physicians in other specialties.

In good news, internists lost less money on claims that were denied or that required resubmission than most of their colleagues in other specialties. By comparison, internists reported losing 15% on such claims, and plastic surgeons lost almost twice that percentage (28%).

The survey authors noted, “One study found that, on average, 63% of denied claims are recoverable, but healthcare professionals spend about $118 per claim on appeals.”

Relationships with patients most rewarding

When asked about the most rewarding part of their job, internists ranked “gratitude/relationships with patients” at the top. In this survey, internists spent about the same amount of time with patients that all physicians spent with patients on average, 37.9 hours per week.

“Making good money at a job I like” was the fourth-biggest driver of satisfaction (only 11% said that was the most rewarding part), behind “being very good at what I do/finding answers, diagnoses” and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”

Some questions on the survey pertained to the use of advanced practice providers. More than half of internists (54%) reported their practice included nurse practitioners (NPs), and 36% included physician assistants (PAs); 37% employed neither.

Half of the internists who employed NPs and PAs said they had no effect on profitability, 44% said they increased it, and 6% said they decreased it. Physicians overall were split (47% each) on whether NPs and PAs increased profitability or had no effect on it.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Volunteering during the pandemic: What doctors need to know

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a silly picture of myself with one N95 mask and asked the folks on Twitter what else I might need. In a matter of a few days, I had filled out a form online for volunteering through the Society of Critical Care Medicine, been assigned to work at a hospital in New York City, and booked a hotel and flight.

I was going to volunteer, although I wasn’t sure of exactly what I would be doing. I’m trained as a bariatric surgeon – not obviously suited for critical care, but arguably even less suited for medicine wards.

I undoubtedly would have been less prepared if I hadn’t sought guidance on what to bring with me and generally what to expect. Less than a day after seeking advice, two local women physicians donated N95s, face shields, gowns, bouffants, and coveralls to me. I also received a laminated photo of myself to attach to my gown in the mail from a stranger I met online.

Others suggested I bring goggles, chocolate, protein bars, hand sanitizer, powdered laundry detergent, and alcohol wipes. After running around all over town, I was able find everything but the wipes.

Just as others helped me achieve my goal of volunteering, I hope I can guide those who would like to do similar work by sharing details about my experience and other information I have collected about volunteering.

Below I answer some questions that those considering volunteering might have, including why I went, who I contacted to set this up, who paid for my flight, and what I observed in the hospital.

Motivation and logistics

I am currently serving in a nonclinical role at my institution. So when the pandemic hit the United States, I felt an immense amount of guilt for not being on the front lines caring for patients. I offered my services to local hospitals and registered for the California Health Corps. I live in northern California, which was the first part of the country to shelter in place. Since my home was actually relatively spared, my services weren’t needed.

As the weeks passed, I was slowly getting more and more fit, exercising in my house since there was little else I could do, and the guilt became a cloud gathering over my head.

I decided to volunteer in a place where demands for help were higher – New York. I tried very hard to sign up to volunteer through the state’s registry for health care volunteers, but was unable to do so. Coincidentally, around that same time, I saw on Twitter that Josh Mugele, MD, emergency medicine physician and program director of the emergency medicine residency at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville, was on his way to New York. He shared the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s form for volunteering with me, and in less than 48 hours, I was assigned to a hospital in New York City. Five days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to my destination on the opposite side of the country. The airline paid for my flight.

This is not the only path to volunteering. Another volunteer, Sara Pauk, MD, ob.gyn. at the University of Washington, Seattle, found her volunteer role through contacting the New York City Health and Hospitals system directly. Other who have volunteered told me they had contacted specific hospitals or worked with agencies that were placing physicians.

PPE

The Brooklyn hospital where I volunteered provided me with two sets of scrubs and two N95s. Gowns were variably available on our unit, and there was no eye protection. As a colleague of mine, Ben Daxon, MD, anesthesia and critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., had suggested, anyone volunteering in this context should bring personal protective equipment (PPE) – That includes gowns, bouffants/scrub caps, eye protection, masks, and scrubs.

The “COVID corner”

Once I arrived in New York, I did not feel particularly safe in my hotel, so I moved to another the next day. Then I had to sort out how to keep the whole room from being contaminated. I created a “COVID corner” right by the door where I kept almost everything that had been outside the door.

Every time I walked in the door, I immediately took off my shoes and left them in that corner. I could not find alcohol wipes, even after looking around in the city, so I relied on time to kill the virus, which I presumed was on everything that came from outside.

Groceries stayed by the door for 48-72 hours if possible. After that, I would move them to the “clean” parts of the room. I wore the same outfit to and from the hospital everyday, putting it on right before I left and taking it off immediately after walking into the room (and then proceeding directly to the shower). Those clothes – “my COVID outfit” – lived in the COVID corner. Anything else I wore, including exercise clothes and underwear, got washed right after I wore it.

At the hospital, I would change into scrubs and leave my COVID outfit in a plastic bag inside my handbag. Note: I fully accepted that my handbag was now a COVID handbag. I kept a pair of clogs in the hospital for daily wear. Without alcohol wipes, my room did not feel clean. But I did start to become at peace with my system, even though it was inferior to the system I use in my own home.

Meal time

In addition to bringing snacks from home, I gathered some meal items at a grocery store during my first day in New York. These included water, yogurt, a few protein drinks, fruit, and some mini chocolate croissants. It’s a pandemic – chocolate is encouraged, right?

Neither any of the volunteers I knew nor I had access to a kitchen, so this was about the best I could do.

My first week I worked nights and ate sporadically. A couple of days I bought bagel sandwiches on the way back to the hotel in the morning. Other times, I would eat yogurt or a protein bar.

I had trouble sleeping, so I would wake up early and either do yoga in my room or go for a run in a nearby park. Usually I didn’t plan well enough to eat before I went into the hospital, so I would take yogurt, some fruit, and a croissant with me as I headed out. It was hard eating on the run with a mask on my face.

When I switched to working days, I actually ordered proper dinners from local Thai, Mexican, and Indian restaurants. I paid around $20 a meal.

One night I even had dinner with a coworker who was staying at a hotel close to mine – what a luxury! Prior to all this I had been sheltering in place alone for weeks, so in that sense, this experience was a delight. I interacted with other people, in person, every day!

My commute

My hotel was about 20 minutes from the hospital. Well-meaning folks informed me that Hertz had free car rentals and Uber had discounts for health care workers. When I investigated these options, I found that only employees of certain hospitals were eligible. As a volunteer, I was not eligible.

I ultimately took Uber back and forth, and I was lucky that a few friends had sent me Uber gift cards to defray the costs. Most days, I paid about $20 each way, although 1 day there actually was “surge pricing.” The grand total for the trip was close to $800.

Many of the Uber drivers had put up plastic partitions – reminiscent of the plastic Dexter would use to contain his crime scenes – to increase their separation from their passengers. It was a bit eerie, but also somewhat welcome.

New normal

The actual work at the hospital in Brooklyn where I volunteered was different from usual practice in numerous ways. One of the things I immediately noticed was how difficult it was to get chest x-rays. After placing an emergent chest tube for a tension pneumothorax, it took about 6 hours to get a chest x-ray to assess placement.

Because code medications were needed much more frequently than normal times, these medications were kept in an open supply closet for ease of access. Many of the ventilators looked like they were from the 1970s. (They had been borrowed from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.)

What was most distinct about this work was the sheer volume of deaths and dying patients -- at least one death on our unit occurred every day I was there -- and the way families communicated with their loved ones. Countless times I held my phone over the faces of my unconscious patients to let their family profess their love and beg them to fight. While I have had to deliver bad news over the phone many times in my career, I have never had to intrude on families’ last conversations with their dying loved ones or witness that conversation occurring via a tiny screen.

Reentry

In many ways, I am lucky that I do not do clinical work in my hometown. So while other volunteers were figuring out how many more vacation days they would have to use, or whether they would have to take unpaid leave, and when and how they would get tested, all I had to do was prepare to go back home and quarantine myself for a couple of weeks.

I used up 2 weeks of vacation to volunteer in New York, but luckily, I could resume my normal work the day after I returned home.

Obviously, living in the pandemic is unique to anything we have ever experienced. Recognizing that, I recorded video diaries the whole time I was in New York. I laughed (like when I tried to fit all of my PPE on my tiny head), and I cried – several times. I suppose 1 day I may actually watch them and be reminded of what it was like to have been able to serve in this historic moment. Until then, they will remain locked up on the same phone that served as the only communication vehicle between my patients and their loved ones.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University.

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a silly picture of myself with one N95 mask and asked the folks on Twitter what else I might need. In a matter of a few days, I had filled out a form online for volunteering through the Society of Critical Care Medicine, been assigned to work at a hospital in New York City, and booked a hotel and flight.

I was going to volunteer, although I wasn’t sure of exactly what I would be doing. I’m trained as a bariatric surgeon – not obviously suited for critical care, but arguably even less suited for medicine wards.

I undoubtedly would have been less prepared if I hadn’t sought guidance on what to bring with me and generally what to expect. Less than a day after seeking advice, two local women physicians donated N95s, face shields, gowns, bouffants, and coveralls to me. I also received a laminated photo of myself to attach to my gown in the mail from a stranger I met online.

Others suggested I bring goggles, chocolate, protein bars, hand sanitizer, powdered laundry detergent, and alcohol wipes. After running around all over town, I was able find everything but the wipes.

Just as others helped me achieve my goal of volunteering, I hope I can guide those who would like to do similar work by sharing details about my experience and other information I have collected about volunteering.

Below I answer some questions that those considering volunteering might have, including why I went, who I contacted to set this up, who paid for my flight, and what I observed in the hospital.

Motivation and logistics

I am currently serving in a nonclinical role at my institution. So when the pandemic hit the United States, I felt an immense amount of guilt for not being on the front lines caring for patients. I offered my services to local hospitals and registered for the California Health Corps. I live in northern California, which was the first part of the country to shelter in place. Since my home was actually relatively spared, my services weren’t needed.

As the weeks passed, I was slowly getting more and more fit, exercising in my house since there was little else I could do, and the guilt became a cloud gathering over my head.

I decided to volunteer in a place where demands for help were higher – New York. I tried very hard to sign up to volunteer through the state’s registry for health care volunteers, but was unable to do so. Coincidentally, around that same time, I saw on Twitter that Josh Mugele, MD, emergency medicine physician and program director of the emergency medicine residency at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville, was on his way to New York. He shared the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s form for volunteering with me, and in less than 48 hours, I was assigned to a hospital in New York City. Five days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to my destination on the opposite side of the country. The airline paid for my flight.

This is not the only path to volunteering. Another volunteer, Sara Pauk, MD, ob.gyn. at the University of Washington, Seattle, found her volunteer role through contacting the New York City Health and Hospitals system directly. Other who have volunteered told me they had contacted specific hospitals or worked with agencies that were placing physicians.

PPE

The Brooklyn hospital where I volunteered provided me with two sets of scrubs and two N95s. Gowns were variably available on our unit, and there was no eye protection. As a colleague of mine, Ben Daxon, MD, anesthesia and critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., had suggested, anyone volunteering in this context should bring personal protective equipment (PPE) – That includes gowns, bouffants/scrub caps, eye protection, masks, and scrubs.

The “COVID corner”

Once I arrived in New York, I did not feel particularly safe in my hotel, so I moved to another the next day. Then I had to sort out how to keep the whole room from being contaminated. I created a “COVID corner” right by the door where I kept almost everything that had been outside the door.

Every time I walked in the door, I immediately took off my shoes and left them in that corner. I could not find alcohol wipes, even after looking around in the city, so I relied on time to kill the virus, which I presumed was on everything that came from outside.

Groceries stayed by the door for 48-72 hours if possible. After that, I would move them to the “clean” parts of the room. I wore the same outfit to and from the hospital everyday, putting it on right before I left and taking it off immediately after walking into the room (and then proceeding directly to the shower). Those clothes – “my COVID outfit” – lived in the COVID corner. Anything else I wore, including exercise clothes and underwear, got washed right after I wore it.

At the hospital, I would change into scrubs and leave my COVID outfit in a plastic bag inside my handbag. Note: I fully accepted that my handbag was now a COVID handbag. I kept a pair of clogs in the hospital for daily wear. Without alcohol wipes, my room did not feel clean. But I did start to become at peace with my system, even though it was inferior to the system I use in my own home.

Meal time

In addition to bringing snacks from home, I gathered some meal items at a grocery store during my first day in New York. These included water, yogurt, a few protein drinks, fruit, and some mini chocolate croissants. It’s a pandemic – chocolate is encouraged, right?

Neither any of the volunteers I knew nor I had access to a kitchen, so this was about the best I could do.

My first week I worked nights and ate sporadically. A couple of days I bought bagel sandwiches on the way back to the hotel in the morning. Other times, I would eat yogurt or a protein bar.

I had trouble sleeping, so I would wake up early and either do yoga in my room or go for a run in a nearby park. Usually I didn’t plan well enough to eat before I went into the hospital, so I would take yogurt, some fruit, and a croissant with me as I headed out. It was hard eating on the run with a mask on my face.

When I switched to working days, I actually ordered proper dinners from local Thai, Mexican, and Indian restaurants. I paid around $20 a meal.

One night I even had dinner with a coworker who was staying at a hotel close to mine – what a luxury! Prior to all this I had been sheltering in place alone for weeks, so in that sense, this experience was a delight. I interacted with other people, in person, every day!

My commute

My hotel was about 20 minutes from the hospital. Well-meaning folks informed me that Hertz had free car rentals and Uber had discounts for health care workers. When I investigated these options, I found that only employees of certain hospitals were eligible. As a volunteer, I was not eligible.

I ultimately took Uber back and forth, and I was lucky that a few friends had sent me Uber gift cards to defray the costs. Most days, I paid about $20 each way, although 1 day there actually was “surge pricing.” The grand total for the trip was close to $800.

Many of the Uber drivers had put up plastic partitions – reminiscent of the plastic Dexter would use to contain his crime scenes – to increase their separation from their passengers. It was a bit eerie, but also somewhat welcome.

New normal

The actual work at the hospital in Brooklyn where I volunteered was different from usual practice in numerous ways. One of the things I immediately noticed was how difficult it was to get chest x-rays. After placing an emergent chest tube for a tension pneumothorax, it took about 6 hours to get a chest x-ray to assess placement.

Because code medications were needed much more frequently than normal times, these medications were kept in an open supply closet for ease of access. Many of the ventilators looked like they were from the 1970s. (They had been borrowed from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.)

What was most distinct about this work was the sheer volume of deaths and dying patients -- at least one death on our unit occurred every day I was there -- and the way families communicated with their loved ones. Countless times I held my phone over the faces of my unconscious patients to let their family profess their love and beg them to fight. While I have had to deliver bad news over the phone many times in my career, I have never had to intrude on families’ last conversations with their dying loved ones or witness that conversation occurring via a tiny screen.

Reentry

In many ways, I am lucky that I do not do clinical work in my hometown. So while other volunteers were figuring out how many more vacation days they would have to use, or whether they would have to take unpaid leave, and when and how they would get tested, all I had to do was prepare to go back home and quarantine myself for a couple of weeks.

I used up 2 weeks of vacation to volunteer in New York, but luckily, I could resume my normal work the day after I returned home.

Obviously, living in the pandemic is unique to anything we have ever experienced. Recognizing that, I recorded video diaries the whole time I was in New York. I laughed (like when I tried to fit all of my PPE on my tiny head), and I cried – several times. I suppose 1 day I may actually watch them and be reminded of what it was like to have been able to serve in this historic moment. Until then, they will remain locked up on the same phone that served as the only communication vehicle between my patients and their loved ones.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University.

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a silly picture of myself with one N95 mask and asked the folks on Twitter what else I might need. In a matter of a few days, I had filled out a form online for volunteering through the Society of Critical Care Medicine, been assigned to work at a hospital in New York City, and booked a hotel and flight.

I was going to volunteer, although I wasn’t sure of exactly what I would be doing. I’m trained as a bariatric surgeon – not obviously suited for critical care, but arguably even less suited for medicine wards.

I undoubtedly would have been less prepared if I hadn’t sought guidance on what to bring with me and generally what to expect. Less than a day after seeking advice, two local women physicians donated N95s, face shields, gowns, bouffants, and coveralls to me. I also received a laminated photo of myself to attach to my gown in the mail from a stranger I met online.

Others suggested I bring goggles, chocolate, protein bars, hand sanitizer, powdered laundry detergent, and alcohol wipes. After running around all over town, I was able find everything but the wipes.

Just as others helped me achieve my goal of volunteering, I hope I can guide those who would like to do similar work by sharing details about my experience and other information I have collected about volunteering.

Below I answer some questions that those considering volunteering might have, including why I went, who I contacted to set this up, who paid for my flight, and what I observed in the hospital.

Motivation and logistics

I am currently serving in a nonclinical role at my institution. So when the pandemic hit the United States, I felt an immense amount of guilt for not being on the front lines caring for patients. I offered my services to local hospitals and registered for the California Health Corps. I live in northern California, which was the first part of the country to shelter in place. Since my home was actually relatively spared, my services weren’t needed.

As the weeks passed, I was slowly getting more and more fit, exercising in my house since there was little else I could do, and the guilt became a cloud gathering over my head.

I decided to volunteer in a place where demands for help were higher – New York. I tried very hard to sign up to volunteer through the state’s registry for health care volunteers, but was unable to do so. Coincidentally, around that same time, I saw on Twitter that Josh Mugele, MD, emergency medicine physician and program director of the emergency medicine residency at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville, was on his way to New York. He shared the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s form for volunteering with me, and in less than 48 hours, I was assigned to a hospital in New York City. Five days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to my destination on the opposite side of the country. The airline paid for my flight.

This is not the only path to volunteering. Another volunteer, Sara Pauk, MD, ob.gyn. at the University of Washington, Seattle, found her volunteer role through contacting the New York City Health and Hospitals system directly. Other who have volunteered told me they had contacted specific hospitals or worked with agencies that were placing physicians.

PPE

The Brooklyn hospital where I volunteered provided me with two sets of scrubs and two N95s. Gowns were variably available on our unit, and there was no eye protection. As a colleague of mine, Ben Daxon, MD, anesthesia and critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., had suggested, anyone volunteering in this context should bring personal protective equipment (PPE) – That includes gowns, bouffants/scrub caps, eye protection, masks, and scrubs.

The “COVID corner”

Once I arrived in New York, I did not feel particularly safe in my hotel, so I moved to another the next day. Then I had to sort out how to keep the whole room from being contaminated. I created a “COVID corner” right by the door where I kept almost everything that had been outside the door.

Every time I walked in the door, I immediately took off my shoes and left them in that corner. I could not find alcohol wipes, even after looking around in the city, so I relied on time to kill the virus, which I presumed was on everything that came from outside.

Groceries stayed by the door for 48-72 hours if possible. After that, I would move them to the “clean” parts of the room. I wore the same outfit to and from the hospital everyday, putting it on right before I left and taking it off immediately after walking into the room (and then proceeding directly to the shower). Those clothes – “my COVID outfit” – lived in the COVID corner. Anything else I wore, including exercise clothes and underwear, got washed right after I wore it.

At the hospital, I would change into scrubs and leave my COVID outfit in a plastic bag inside my handbag. Note: I fully accepted that my handbag was now a COVID handbag. I kept a pair of clogs in the hospital for daily wear. Without alcohol wipes, my room did not feel clean. But I did start to become at peace with my system, even though it was inferior to the system I use in my own home.

Meal time

In addition to bringing snacks from home, I gathered some meal items at a grocery store during my first day in New York. These included water, yogurt, a few protein drinks, fruit, and some mini chocolate croissants. It’s a pandemic – chocolate is encouraged, right?

Neither any of the volunteers I knew nor I had access to a kitchen, so this was about the best I could do.

My first week I worked nights and ate sporadically. A couple of days I bought bagel sandwiches on the way back to the hotel in the morning. Other times, I would eat yogurt or a protein bar.

I had trouble sleeping, so I would wake up early and either do yoga in my room or go for a run in a nearby park. Usually I didn’t plan well enough to eat before I went into the hospital, so I would take yogurt, some fruit, and a croissant with me as I headed out. It was hard eating on the run with a mask on my face.

When I switched to working days, I actually ordered proper dinners from local Thai, Mexican, and Indian restaurants. I paid around $20 a meal.

One night I even had dinner with a coworker who was staying at a hotel close to mine – what a luxury! Prior to all this I had been sheltering in place alone for weeks, so in that sense, this experience was a delight. I interacted with other people, in person, every day!

My commute

My hotel was about 20 minutes from the hospital. Well-meaning folks informed me that Hertz had free car rentals and Uber had discounts for health care workers. When I investigated these options, I found that only employees of certain hospitals were eligible. As a volunteer, I was not eligible.

I ultimately took Uber back and forth, and I was lucky that a few friends had sent me Uber gift cards to defray the costs. Most days, I paid about $20 each way, although 1 day there actually was “surge pricing.” The grand total for the trip was close to $800.

Many of the Uber drivers had put up plastic partitions – reminiscent of the plastic Dexter would use to contain his crime scenes – to increase their separation from their passengers. It was a bit eerie, but also somewhat welcome.

New normal

The actual work at the hospital in Brooklyn where I volunteered was different from usual practice in numerous ways. One of the things I immediately noticed was how difficult it was to get chest x-rays. After placing an emergent chest tube for a tension pneumothorax, it took about 6 hours to get a chest x-ray to assess placement.

Because code medications were needed much more frequently than normal times, these medications were kept in an open supply closet for ease of access. Many of the ventilators looked like they were from the 1970s. (They had been borrowed from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.)

What was most distinct about this work was the sheer volume of deaths and dying patients -- at least one death on our unit occurred every day I was there -- and the way families communicated with their loved ones. Countless times I held my phone over the faces of my unconscious patients to let their family profess their love and beg them to fight. While I have had to deliver bad news over the phone many times in my career, I have never had to intrude on families’ last conversations with their dying loved ones or witness that conversation occurring via a tiny screen.

Reentry

In many ways, I am lucky that I do not do clinical work in my hometown. So while other volunteers were figuring out how many more vacation days they would have to use, or whether they would have to take unpaid leave, and when and how they would get tested, all I had to do was prepare to go back home and quarantine myself for a couple of weeks.

I used up 2 weeks of vacation to volunteer in New York, but luckily, I could resume my normal work the day after I returned home.

Obviously, living in the pandemic is unique to anything we have ever experienced. Recognizing that, I recorded video diaries the whole time I was in New York. I laughed (like when I tried to fit all of my PPE on my tiny head), and I cried – several times. I suppose 1 day I may actually watch them and be reminded of what it was like to have been able to serve in this historic moment. Until then, they will remain locked up on the same phone that served as the only communication vehicle between my patients and their loved ones.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University.

COVID-19 crisis: We must care for ourselves as we care for others

“I do not shrink from this responsibility – I welcome it.” – John F. Kennedy, inaugural address

COVID-19 has changed our world. Social distancing is now the norm and flattening the curve is our motto.

In the Pennsylvania community in which we work, the first person to don protective gear and sample patients for viral testing in a rapidly organized COVID-19 testing site was John Russell, MD, a family physician. When I asked him about his experience, Dr. Russell said: “No one became a fireman to get cats out of trees ... it was to fight fires. As doctors, this is the same idea ... this is a chance to help fight the fires in our community.”

And, of course, it is primary care providers – family physicians, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses – who day in and day out are putting aside their own fears, while dealing with those of their family, to come to work with a sense of purpose and courage.

The military uses the term “operational tempo” to describe the speed and intensity of actions relative to the speed and intensity of unfolding events in the operational environment. Family physicians are being asked to work at an increased speed in unfamiliar terrain as our environments change by the hour. The challenge is to answer the call – and take care of ourselves – in unprecedented ways. We often use anticipatory guidance with our patients to help prepare them for the challenges they will face. So too must we anticipate the things we will need to be attentive to in the coming months in order to sustain the effort that will be required of us.

With this in mind, we would be wise to consider developing plans in three domains: physical, mental, and social.

With gyms closed and restaurants limiting their offerings to take-out, this is an opportune time to create an exercise regimen at home and experiment with healthy meal options. YouTube videos abound for workouts of every length. And of course, you can simply take a daily walk, go for a run, or take a bike ride. Similarly, good choices can be made with take-out and the foods we prepare at home.

To take care of our mental health, we need to have the discipline to take breaks, delegate when necessary, and use downtime to clear our minds. Need another option? Consider meditation. Google “best meditation apps” and take your pick.

From a social standpoint, we must be proactive about preventing emotional isolation. Technology allows us to connect with others through messaging and face-to-face video. We need to remember to regularly check in with those we care about; few things in life are as affirming as the connections with those who are close to us: family, coworkers, and patients.

Out of crisis comes opportunity. Should we be quarantined, we can remind ourselves that Sir Isaac Newton, while in quarantine during the bubonic plague, laid the foundation for classical physics, composed theories on light and optics, and penned his first draft of the law of gravity.1

Life carries on amidst the pandemic. Even though the current focus is on the COVID-19 crisis, our many needs, joys, and challenges as human beings remain. Today, someone will find out she is pregnant and someone else will be diagnosed with cancer, plan a wedding, or attend the funeral of a loved one. We, as family physicians, have the training to lead with courage and empathy. We have the expertise gained through years of helping patients though diverse physical and emotional challenges.

We will continue to listen to our patients’ stories, diagnose and treat their diseases, and take steps to bring a sense of calm to the chaos around us. We need to be mindful of our own mindset, because we have a choice. As the psychologist Victor Frankl said in 1946 after being liberated from the concentration camps, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”2

A version of this commentary originally appeared in the Journal of Family Practice (J Fam Pract. 2020 April;69[3]:119,153).

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Aaron Sutton is a behavioral health consultant and faculty member in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. Brockell G. “During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. He used the time wisely.” The Washington Post. 2020 Mar 12.

2. Frankl VE. “Man’s Search for Meaning.” Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

“I do not shrink from this responsibility – I welcome it.” – John F. Kennedy, inaugural address

COVID-19 has changed our world. Social distancing is now the norm and flattening the curve is our motto.

In the Pennsylvania community in which we work, the first person to don protective gear and sample patients for viral testing in a rapidly organized COVID-19 testing site was John Russell, MD, a family physician. When I asked him about his experience, Dr. Russell said: “No one became a fireman to get cats out of trees ... it was to fight fires. As doctors, this is the same idea ... this is a chance to help fight the fires in our community.”

And, of course, it is primary care providers – family physicians, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses – who day in and day out are putting aside their own fears, while dealing with those of their family, to come to work with a sense of purpose and courage.

The military uses the term “operational tempo” to describe the speed and intensity of actions relative to the speed and intensity of unfolding events in the operational environment. Family physicians are being asked to work at an increased speed in unfamiliar terrain as our environments change by the hour. The challenge is to answer the call – and take care of ourselves – in unprecedented ways. We often use anticipatory guidance with our patients to help prepare them for the challenges they will face. So too must we anticipate the things we will need to be attentive to in the coming months in order to sustain the effort that will be required of us.

With this in mind, we would be wise to consider developing plans in three domains: physical, mental, and social.

With gyms closed and restaurants limiting their offerings to take-out, this is an opportune time to create an exercise regimen at home and experiment with healthy meal options. YouTube videos abound for workouts of every length. And of course, you can simply take a daily walk, go for a run, or take a bike ride. Similarly, good choices can be made with take-out and the foods we prepare at home.

To take care of our mental health, we need to have the discipline to take breaks, delegate when necessary, and use downtime to clear our minds. Need another option? Consider meditation. Google “best meditation apps” and take your pick.

From a social standpoint, we must be proactive about preventing emotional isolation. Technology allows us to connect with others through messaging and face-to-face video. We need to remember to regularly check in with those we care about; few things in life are as affirming as the connections with those who are close to us: family, coworkers, and patients.

Out of crisis comes opportunity. Should we be quarantined, we can remind ourselves that Sir Isaac Newton, while in quarantine during the bubonic plague, laid the foundation for classical physics, composed theories on light and optics, and penned his first draft of the law of gravity.1

Life carries on amidst the pandemic. Even though the current focus is on the COVID-19 crisis, our many needs, joys, and challenges as human beings remain. Today, someone will find out she is pregnant and someone else will be diagnosed with cancer, plan a wedding, or attend the funeral of a loved one. We, as family physicians, have the training to lead with courage and empathy. We have the expertise gained through years of helping patients though diverse physical and emotional challenges.

We will continue to listen to our patients’ stories, diagnose and treat their diseases, and take steps to bring a sense of calm to the chaos around us. We need to be mindful of our own mindset, because we have a choice. As the psychologist Victor Frankl said in 1946 after being liberated from the concentration camps, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”2

A version of this commentary originally appeared in the Journal of Family Practice (J Fam Pract. 2020 April;69[3]:119,153).

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Aaron Sutton is a behavioral health consultant and faculty member in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. Brockell G. “During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. He used the time wisely.” The Washington Post. 2020 Mar 12.

2. Frankl VE. “Man’s Search for Meaning.” Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

“I do not shrink from this responsibility – I welcome it.” – John F. Kennedy, inaugural address

COVID-19 has changed our world. Social distancing is now the norm and flattening the curve is our motto.

In the Pennsylvania community in which we work, the first person to don protective gear and sample patients for viral testing in a rapidly organized COVID-19 testing site was John Russell, MD, a family physician. When I asked him about his experience, Dr. Russell said: “No one became a fireman to get cats out of trees ... it was to fight fires. As doctors, this is the same idea ... this is a chance to help fight the fires in our community.”

And, of course, it is primary care providers – family physicians, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses – who day in and day out are putting aside their own fears, while dealing with those of their family, to come to work with a sense of purpose and courage.

The military uses the term “operational tempo” to describe the speed and intensity of actions relative to the speed and intensity of unfolding events in the operational environment. Family physicians are being asked to work at an increased speed in unfamiliar terrain as our environments change by the hour. The challenge is to answer the call – and take care of ourselves – in unprecedented ways. We often use anticipatory guidance with our patients to help prepare them for the challenges they will face. So too must we anticipate the things we will need to be attentive to in the coming months in order to sustain the effort that will be required of us.

With this in mind, we would be wise to consider developing plans in three domains: physical, mental, and social.

With gyms closed and restaurants limiting their offerings to take-out, this is an opportune time to create an exercise regimen at home and experiment with healthy meal options. YouTube videos abound for workouts of every length. And of course, you can simply take a daily walk, go for a run, or take a bike ride. Similarly, good choices can be made with take-out and the foods we prepare at home.

To take care of our mental health, we need to have the discipline to take breaks, delegate when necessary, and use downtime to clear our minds. Need another option? Consider meditation. Google “best meditation apps” and take your pick.

From a social standpoint, we must be proactive about preventing emotional isolation. Technology allows us to connect with others through messaging and face-to-face video. We need to remember to regularly check in with those we care about; few things in life are as affirming as the connections with those who are close to us: family, coworkers, and patients.

Out of crisis comes opportunity. Should we be quarantined, we can remind ourselves that Sir Isaac Newton, while in quarantine during the bubonic plague, laid the foundation for classical physics, composed theories on light and optics, and penned his first draft of the law of gravity.1

Life carries on amidst the pandemic. Even though the current focus is on the COVID-19 crisis, our many needs, joys, and challenges as human beings remain. Today, someone will find out she is pregnant and someone else will be diagnosed with cancer, plan a wedding, or attend the funeral of a loved one. We, as family physicians, have the training to lead with courage and empathy. We have the expertise gained through years of helping patients though diverse physical and emotional challenges.

We will continue to listen to our patients’ stories, diagnose and treat their diseases, and take steps to bring a sense of calm to the chaos around us. We need to be mindful of our own mindset, because we have a choice. As the psychologist Victor Frankl said in 1946 after being liberated from the concentration camps, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”2

A version of this commentary originally appeared in the Journal of Family Practice (J Fam Pract. 2020 April;69[3]:119,153).

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Aaron Sutton is a behavioral health consultant and faculty member in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. Brockell G. “During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. He used the time wisely.” The Washington Post. 2020 Mar 12.

2. Frankl VE. “Man’s Search for Meaning.” Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

NYU med student joins COVID fight: ‘Time to step up’

On the evening of March 24, I got the email. When the bolded letters “We ask for your help” flashed across my screen, I knew exactly what was being asked of me: to graduate early and join the fight against COVID-19.

For the 120 fourth-year medical students in my class at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the arrival of that email was always more a question of when than if. Similar moves had already been made in Italy as well as the United Kingdom, where the surge in patients with COVID-19 has devastated hospitals and left healthcare workers dead or drained. The New York hospitals where I’ve trained, places I have grown to love over the past 4 years, are now experiencing similar horrors. Residents and attending doctors – mentors and teachers – are burned out and exhausted. They need help.

Like most medical students, I chose to pursue medicine out of a desire to help. On both my medical school and residency applications, I spoke about my resolve to bear witness to and provide support to those suffering. Yet, being recruited to the front lines of a global pandemic felt deeply unsettling. Is this how I want to finally enter the world of medicine? The scope of what is actually being asked of me was immense.

Given the onslaught of bad news coming in on every device I had cozied up to during my social distancing, how could I want to do this? I’ve seen the death toll climb in Italy, with dozens of doctors dead. I’ve seen the photos of faces marred by masks worn for 12-16 hours at a time. I’ve been repeatedly reminded that we are just behind Italy. Things are certainly going to get worse.

It sounds selfish and petty, but I feel like COVID-19 has already robbed me of so much. Yet that was my first thought when I received the email. The end of fourth year in medical school is supposed to be a joyous, celebratory time. We have worked years for this moment. So many of us have fought burnout to reach this time, a brief moment of rest between being a medical student and becoming a full-fledged physician.

I matched into residency just 4 days before being asked to join the front lines of the pandemic. I found out my match results without the usual fanfare, sitting on a bench in Madison Square Park, FaceTiming my dad and safely social-distanced from my mom. They both cried tears of joy. Like so many people around the world right now, I couldn’t even embrace my parents. Would they want me to volunteer?

I reached out to my classmates. I thought that some of them would certainly share my worries. I thought they also had to be carrying this uncomfortable kind of grief, a heavy and acidic feeling of dreams collapsing into a moral duty. I received a unanimous reply: “We are needed. It’s our time to step up.” No matter how many “what ifs” I voiced, they wouldn’t crack or waver. Still, even if they never admitted it to me, I wondered whether they privately shared some of my concerns and fears.

Everyone knows information is shared instantly in our Twitter-centric world, but I was still shocked and unprepared for how quickly I was at the center of a major news story. Within an hour of that email, I was contacted by an old acquaintance from elementary school, now a journalist. He had found me through Facebook and asked, “Will you be one of the NYU students graduating early? Would love to get a comment.” Another friend texted me a photo of the leaked email, quipping, “Are you going to save us from the pandemic, Dr. Gabe?!” “It’s not a small decision!” I snapped back.