User login

Suicide increased 35% during 1999-2018 in the U.S.

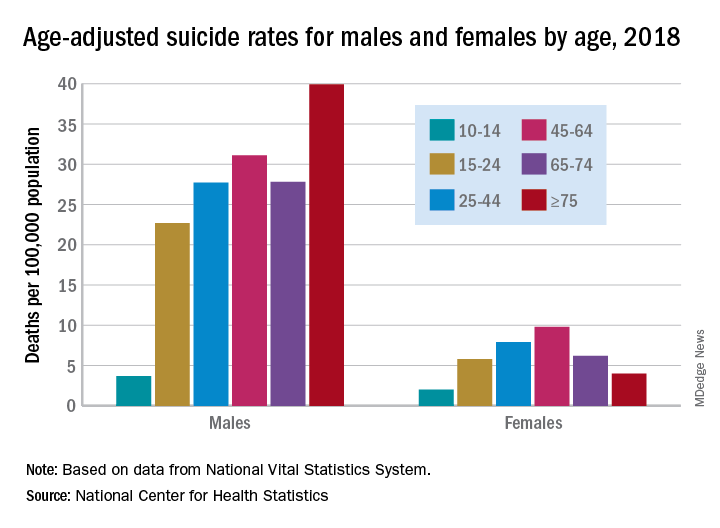

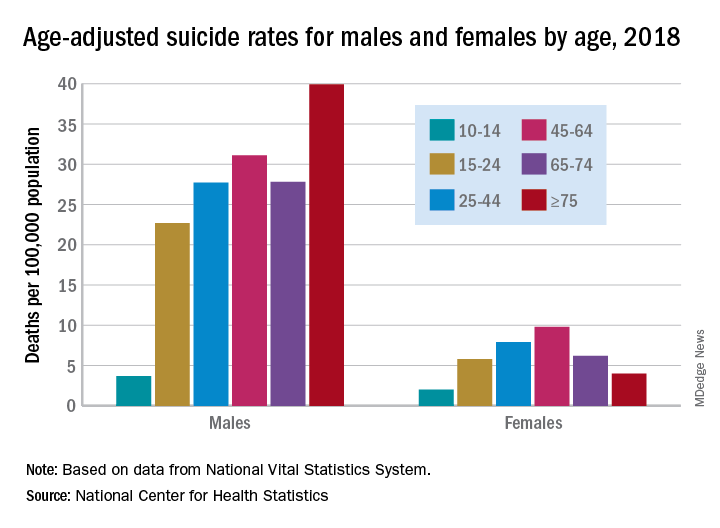

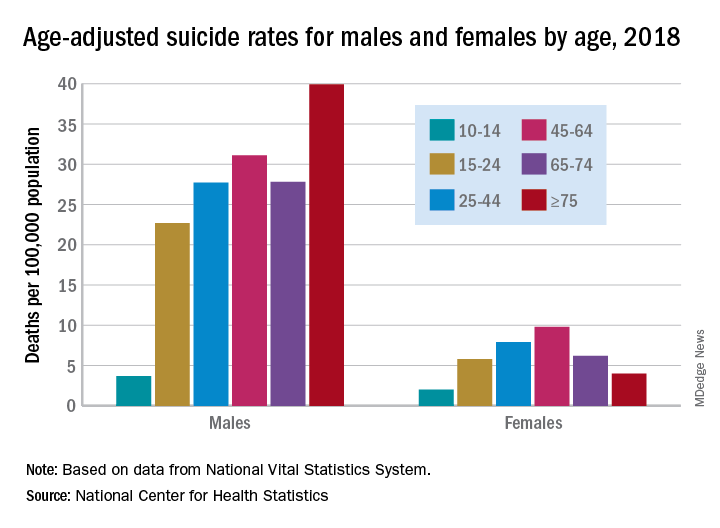

Age-adjusted suicide rate rose from 10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 from 1999 to 2018, according to trends reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a data brief.

Holly Hedegaard, MD, and colleagues from the National Center for Health Statistics within the CDC analyzed final mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. As the second most common cause of death among Americans aged 10-34 years and the fourth most common among those aged 35-54 years, suicide is a major contributer to premature mortality.

at 22.8 and 6.2 per 100,000, respectively. Young people aged 10-14 years among both genders had the lowest rates of completing suicide, but it was men aged 75 years and older and women aged 45-64 years who had the highest rates. All of these trends were consistent throughout the study period.

Drawing from the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, the researchers found that rural counties had significantly higher rates of suicide than did urban counties in 2018, and this was true for men and women. That said, suicide rates were still 3.5-3.9 times higher among men than among women regardless of urbanicity or rurality that year.

The full data brief can be found on the CDC website.

Age-adjusted suicide rate rose from 10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 from 1999 to 2018, according to trends reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a data brief.

Holly Hedegaard, MD, and colleagues from the National Center for Health Statistics within the CDC analyzed final mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. As the second most common cause of death among Americans aged 10-34 years and the fourth most common among those aged 35-54 years, suicide is a major contributer to premature mortality.

at 22.8 and 6.2 per 100,000, respectively. Young people aged 10-14 years among both genders had the lowest rates of completing suicide, but it was men aged 75 years and older and women aged 45-64 years who had the highest rates. All of these trends were consistent throughout the study period.

Drawing from the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, the researchers found that rural counties had significantly higher rates of suicide than did urban counties in 2018, and this was true for men and women. That said, suicide rates were still 3.5-3.9 times higher among men than among women regardless of urbanicity or rurality that year.

The full data brief can be found on the CDC website.

Age-adjusted suicide rate rose from 10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 from 1999 to 2018, according to trends reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a data brief.

Holly Hedegaard, MD, and colleagues from the National Center for Health Statistics within the CDC analyzed final mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. As the second most common cause of death among Americans aged 10-34 years and the fourth most common among those aged 35-54 years, suicide is a major contributer to premature mortality.

at 22.8 and 6.2 per 100,000, respectively. Young people aged 10-14 years among both genders had the lowest rates of completing suicide, but it was men aged 75 years and older and women aged 45-64 years who had the highest rates. All of these trends were consistent throughout the study period.

Drawing from the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, the researchers found that rural counties had significantly higher rates of suicide than did urban counties in 2018, and this was true for men and women. That said, suicide rates were still 3.5-3.9 times higher among men than among women regardless of urbanicity or rurality that year.

The full data brief can be found on the CDC website.

Survey: COVID-19 is getting in our heads

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps across the United States, it is increasingly affecting those who are not infected. Social bonds are being broken, businesses are closing, jobs are being lost, and the stress is mounting.

In a poll conducted March 25-30, 45% of Americans said that stress resulting from the pandemic is having a negative impact on their mental health, compared with 32% expressing that view just 2 weeks earlier, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported April 2.

In the later survey, the effect looked like this: 19% of all respondents said that the pandemic has had a major negative impact and 26% said it has been minor so far. Women were more likely than men (24% vs. 15%) to report a major impact, as were blacks and Hispanic adults (both at 24%) compared with whites (17%), the KFF investigators said.

More Hispanic (44%) and black (42%) respondents also said that they had already lost their job, lost income, or had their hours reduced without pay as a result of the pandemic, compared with whites (36%). Among all respondents, 26% had lost income from a job or business and 28% had lost their job, been laid off, or had their hours reduced without pay, according to KFF.

A majority of respondents (57%) reported “being worried they will put themselves at risk of exposure to coronavirus because they can’t afford to stay home and miss work,” the researchers said. That figure is up from 35% in the earlier survey.

Anxiety about work-related exposure was even higher among hourly workers or those who get paid by the job (61%) and among employed adults who earn less than $40,000 annually (72%), they reported.

Overall, 72% of respondents said that their lives have been disrupted “a lot” or “some” by the coronavirus outbreak, and that is a jump of 32 percentage points over the previous poll, the investigators noted.

The disruption is expected to continue, it seems, as 74% believe that the worst is yet to come “in spite of the health, social and economic upheaval that Americans are already experiencing,” they wrote.

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps across the United States, it is increasingly affecting those who are not infected. Social bonds are being broken, businesses are closing, jobs are being lost, and the stress is mounting.

In a poll conducted March 25-30, 45% of Americans said that stress resulting from the pandemic is having a negative impact on their mental health, compared with 32% expressing that view just 2 weeks earlier, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported April 2.

In the later survey, the effect looked like this: 19% of all respondents said that the pandemic has had a major negative impact and 26% said it has been minor so far. Women were more likely than men (24% vs. 15%) to report a major impact, as were blacks and Hispanic adults (both at 24%) compared with whites (17%), the KFF investigators said.

More Hispanic (44%) and black (42%) respondents also said that they had already lost their job, lost income, or had their hours reduced without pay as a result of the pandemic, compared with whites (36%). Among all respondents, 26% had lost income from a job or business and 28% had lost their job, been laid off, or had their hours reduced without pay, according to KFF.

A majority of respondents (57%) reported “being worried they will put themselves at risk of exposure to coronavirus because they can’t afford to stay home and miss work,” the researchers said. That figure is up from 35% in the earlier survey.

Anxiety about work-related exposure was even higher among hourly workers or those who get paid by the job (61%) and among employed adults who earn less than $40,000 annually (72%), they reported.

Overall, 72% of respondents said that their lives have been disrupted “a lot” or “some” by the coronavirus outbreak, and that is a jump of 32 percentage points over the previous poll, the investigators noted.

The disruption is expected to continue, it seems, as 74% believe that the worst is yet to come “in spite of the health, social and economic upheaval that Americans are already experiencing,” they wrote.

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps across the United States, it is increasingly affecting those who are not infected. Social bonds are being broken, businesses are closing, jobs are being lost, and the stress is mounting.

In a poll conducted March 25-30, 45% of Americans said that stress resulting from the pandemic is having a negative impact on their mental health, compared with 32% expressing that view just 2 weeks earlier, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported April 2.

In the later survey, the effect looked like this: 19% of all respondents said that the pandemic has had a major negative impact and 26% said it has been minor so far. Women were more likely than men (24% vs. 15%) to report a major impact, as were blacks and Hispanic adults (both at 24%) compared with whites (17%), the KFF investigators said.

More Hispanic (44%) and black (42%) respondents also said that they had already lost their job, lost income, or had their hours reduced without pay as a result of the pandemic, compared with whites (36%). Among all respondents, 26% had lost income from a job or business and 28% had lost their job, been laid off, or had their hours reduced without pay, according to KFF.

A majority of respondents (57%) reported “being worried they will put themselves at risk of exposure to coronavirus because they can’t afford to stay home and miss work,” the researchers said. That figure is up from 35% in the earlier survey.

Anxiety about work-related exposure was even higher among hourly workers or those who get paid by the job (61%) and among employed adults who earn less than $40,000 annually (72%), they reported.

Overall, 72% of respondents said that their lives have been disrupted “a lot” or “some” by the coronavirus outbreak, and that is a jump of 32 percentage points over the previous poll, the investigators noted.

The disruption is expected to continue, it seems, as 74% believe that the worst is yet to come “in spite of the health, social and economic upheaval that Americans are already experiencing,” they wrote.

CBT by phone reduces depression in Parkinson’s disease

, according to trial results published in Neurology. The treatment’s effect on depression is “moderated by the reduction of negative thoughts,” the target of the intervention, the researchers said.

Telephone-based CBT may be a convenient option for patients, said lead study author Roseanne D. Dobkin, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, N.J., and the VA New Jersey Health Care System in Lyons. “A notable proportion of people with Parkinson’s [disease] do not receive the much needed mental health treatment to facilitate proactive coping with the daily challenges superimposed by their medical condition,” Dr. Dobkin said in a news release. “This study suggests that the effects of the [CBT] last long beyond when the treatment stopped and can be used alongside standard neurological care.”

An undertreated problem

Although depression affects about half of patients with Parkinson’s disease and is associated with physical and cognitive decline, it often goes overlooked and undertreated, the study authors said. Data about the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants are mixed. CBT holds promise for reducing depression in Parkinson’s disease, prior research suggests, but patients may have limited access to in-person sessions because of physical and geographic barriers.

To assess the efficacy of telephone-based CBT for depression in Parkinson’s disease, compared with community-based treatment as usual, Dr. Dobkin and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial. Their study included 72 patients with Parkinson’s disease at an academic medical center. Participants had a depressive disorder, were between aged 35 and 85 years, had stable Parkinson’s disease and mental health treatment for at least 6 weeks, and had a family member or friend willing to participate in the study. The investigators excluded patients with possible dementia or marked cognitive impairment and active suicidal plans or intent.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive usual care plus telephone-based CBT or usual care only. Patients taking antidepressants were evenly divided between the groups.

Telephone-based CBT consisted of weekly 1-hour sessions for 10 weeks. During 6 months of follow-up, patients could receive one session per month if desired. The CBT “targeted negative thoughts (e.g., ‘I have no control’; ‘I am helpless’) and behaviors (e.g., avoidance, excessive worry, lack of exercise),” the investigators said. In addition, therapists trained patients’ care partners by telephone to help patients between sessions. Treatment as usual was defined by patients’ health care teams. For most participants in both groups, treatment as usual included taking antidepressant medication or receiving psychotherapy in the community.

Change in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included whether patients considered their depression much improved and improvements in depression severity (as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]), anxiety (as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale [HAM-A]), and quality of life. The researchers also assessed negative thinking using the Inference Questionnaire. Blinded raters assessed outcomes.

Sustained improvements

Thirty-seven patients were randomized to receive telephone-based CBT, and 35 were randomized to treatment as usual. Overall, 70% were taking antidepressants, and 14% continued receiving psychotherapy from community providers of their choice during the trial. Participants’ average age was 65 years, and 51% were female.

Post treatment, mean improvement in HAM-D score from baseline was 6.53 points in the telephone-based CBT group, compared with −0.27 points in the control group. “Effects at the end of treatment were maintained at 6-month follow-up,” the researchers reported.

About 40% of patients in the CBT group reported that their depression was much improved or very much improved, compared with none of the patients in the control group. Responders had mild to minimal symptomatology on the HAM-D, which indicates that the changes were clinically significant, the authors said.

Secondary outcomes also favored telephone-based CBT. “The intervention was feasible and highly acceptable, yielding an 88% retention rate over the 9-month trial,” Dr. Dobkin and colleagues said.

Compared with other control conditions, treatment-as-usual controls may enhance the effect size of an intervention, the authors noted. In addition, factors such as therapeutic relationship, time, and attention likely contribute to psychotherapy outcomes.

Success may hinge on cognitive ability

“The success of this trial highlights the need for further efficacy studies targeting neuropsychiatric manifestations of [Parkinson’s disease] and adds urgency to the discussion over policies regarding access to tele–mental health, especially for vulnerable populations with limited access to in-person mental health services,” Gregory M. Pontone, MD, and Kelly A. Mills, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Pontone and Dr. Mills are affiliated with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“Only rudimentary evidence” exists to guide the treatment of depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease, the editorialists said. “Patient preference and tolerability suggest that nonpharmacologic therapies, such as CBT, are preferred as first-line treatment. Yet access to qualified CBT practitioners, especially those with a clinical knowledge of [Parkinson’s disease], is limited.”

Despite its advantages and the encouraging results, CBT may have important limitations as well, they said. Patients require a certain degree of cognitive ability to benefit from CBT, and the prevalence of dementia among patients with Parkinson’s disease is about 30%.

Nevertheless, the trial provided evidence of target engagement. “Though caveats include the single-blind design and potential confounding by time spent with patient and caregiver, the authors demonstrated that improvement was mediated by the mechanism of CBT – a reduction in negative thinking.”

The trial was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Parkinson’s Alliance (Parkinson’s Unity Walk). Dr. Mills disclosed a patent pending for a system for phase-dependent cortical brain stimulation, National Institutes of Health funding, pending funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and commercial research support from Global Kinetics Corporation. Dr. Pontone is a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Dobkin RD et al. Neurology. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009292.

, according to trial results published in Neurology. The treatment’s effect on depression is “moderated by the reduction of negative thoughts,” the target of the intervention, the researchers said.

Telephone-based CBT may be a convenient option for patients, said lead study author Roseanne D. Dobkin, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, N.J., and the VA New Jersey Health Care System in Lyons. “A notable proportion of people with Parkinson’s [disease] do not receive the much needed mental health treatment to facilitate proactive coping with the daily challenges superimposed by their medical condition,” Dr. Dobkin said in a news release. “This study suggests that the effects of the [CBT] last long beyond when the treatment stopped and can be used alongside standard neurological care.”

An undertreated problem

Although depression affects about half of patients with Parkinson’s disease and is associated with physical and cognitive decline, it often goes overlooked and undertreated, the study authors said. Data about the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants are mixed. CBT holds promise for reducing depression in Parkinson’s disease, prior research suggests, but patients may have limited access to in-person sessions because of physical and geographic barriers.

To assess the efficacy of telephone-based CBT for depression in Parkinson’s disease, compared with community-based treatment as usual, Dr. Dobkin and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial. Their study included 72 patients with Parkinson’s disease at an academic medical center. Participants had a depressive disorder, were between aged 35 and 85 years, had stable Parkinson’s disease and mental health treatment for at least 6 weeks, and had a family member or friend willing to participate in the study. The investigators excluded patients with possible dementia or marked cognitive impairment and active suicidal plans or intent.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive usual care plus telephone-based CBT or usual care only. Patients taking antidepressants were evenly divided between the groups.

Telephone-based CBT consisted of weekly 1-hour sessions for 10 weeks. During 6 months of follow-up, patients could receive one session per month if desired. The CBT “targeted negative thoughts (e.g., ‘I have no control’; ‘I am helpless’) and behaviors (e.g., avoidance, excessive worry, lack of exercise),” the investigators said. In addition, therapists trained patients’ care partners by telephone to help patients between sessions. Treatment as usual was defined by patients’ health care teams. For most participants in both groups, treatment as usual included taking antidepressant medication or receiving psychotherapy in the community.

Change in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included whether patients considered their depression much improved and improvements in depression severity (as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]), anxiety (as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale [HAM-A]), and quality of life. The researchers also assessed negative thinking using the Inference Questionnaire. Blinded raters assessed outcomes.

Sustained improvements

Thirty-seven patients were randomized to receive telephone-based CBT, and 35 were randomized to treatment as usual. Overall, 70% were taking antidepressants, and 14% continued receiving psychotherapy from community providers of their choice during the trial. Participants’ average age was 65 years, and 51% were female.

Post treatment, mean improvement in HAM-D score from baseline was 6.53 points in the telephone-based CBT group, compared with −0.27 points in the control group. “Effects at the end of treatment were maintained at 6-month follow-up,” the researchers reported.

About 40% of patients in the CBT group reported that their depression was much improved or very much improved, compared with none of the patients in the control group. Responders had mild to minimal symptomatology on the HAM-D, which indicates that the changes were clinically significant, the authors said.

Secondary outcomes also favored telephone-based CBT. “The intervention was feasible and highly acceptable, yielding an 88% retention rate over the 9-month trial,” Dr. Dobkin and colleagues said.

Compared with other control conditions, treatment-as-usual controls may enhance the effect size of an intervention, the authors noted. In addition, factors such as therapeutic relationship, time, and attention likely contribute to psychotherapy outcomes.

Success may hinge on cognitive ability

“The success of this trial highlights the need for further efficacy studies targeting neuropsychiatric manifestations of [Parkinson’s disease] and adds urgency to the discussion over policies regarding access to tele–mental health, especially for vulnerable populations with limited access to in-person mental health services,” Gregory M. Pontone, MD, and Kelly A. Mills, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Pontone and Dr. Mills are affiliated with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“Only rudimentary evidence” exists to guide the treatment of depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease, the editorialists said. “Patient preference and tolerability suggest that nonpharmacologic therapies, such as CBT, are preferred as first-line treatment. Yet access to qualified CBT practitioners, especially those with a clinical knowledge of [Parkinson’s disease], is limited.”

Despite its advantages and the encouraging results, CBT may have important limitations as well, they said. Patients require a certain degree of cognitive ability to benefit from CBT, and the prevalence of dementia among patients with Parkinson’s disease is about 30%.

Nevertheless, the trial provided evidence of target engagement. “Though caveats include the single-blind design and potential confounding by time spent with patient and caregiver, the authors demonstrated that improvement was mediated by the mechanism of CBT – a reduction in negative thinking.”

The trial was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Parkinson’s Alliance (Parkinson’s Unity Walk). Dr. Mills disclosed a patent pending for a system for phase-dependent cortical brain stimulation, National Institutes of Health funding, pending funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and commercial research support from Global Kinetics Corporation. Dr. Pontone is a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Dobkin RD et al. Neurology. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009292.

, according to trial results published in Neurology. The treatment’s effect on depression is “moderated by the reduction of negative thoughts,” the target of the intervention, the researchers said.

Telephone-based CBT may be a convenient option for patients, said lead study author Roseanne D. Dobkin, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, N.J., and the VA New Jersey Health Care System in Lyons. “A notable proportion of people with Parkinson’s [disease] do not receive the much needed mental health treatment to facilitate proactive coping with the daily challenges superimposed by their medical condition,” Dr. Dobkin said in a news release. “This study suggests that the effects of the [CBT] last long beyond when the treatment stopped and can be used alongside standard neurological care.”

An undertreated problem

Although depression affects about half of patients with Parkinson’s disease and is associated with physical and cognitive decline, it often goes overlooked and undertreated, the study authors said. Data about the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants are mixed. CBT holds promise for reducing depression in Parkinson’s disease, prior research suggests, but patients may have limited access to in-person sessions because of physical and geographic barriers.

To assess the efficacy of telephone-based CBT for depression in Parkinson’s disease, compared with community-based treatment as usual, Dr. Dobkin and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial. Their study included 72 patients with Parkinson’s disease at an academic medical center. Participants had a depressive disorder, were between aged 35 and 85 years, had stable Parkinson’s disease and mental health treatment for at least 6 weeks, and had a family member or friend willing to participate in the study. The investigators excluded patients with possible dementia or marked cognitive impairment and active suicidal plans or intent.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive usual care plus telephone-based CBT or usual care only. Patients taking antidepressants were evenly divided between the groups.

Telephone-based CBT consisted of weekly 1-hour sessions for 10 weeks. During 6 months of follow-up, patients could receive one session per month if desired. The CBT “targeted negative thoughts (e.g., ‘I have no control’; ‘I am helpless’) and behaviors (e.g., avoidance, excessive worry, lack of exercise),” the investigators said. In addition, therapists trained patients’ care partners by telephone to help patients between sessions. Treatment as usual was defined by patients’ health care teams. For most participants in both groups, treatment as usual included taking antidepressant medication or receiving psychotherapy in the community.

Change in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included whether patients considered their depression much improved and improvements in depression severity (as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]), anxiety (as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale [HAM-A]), and quality of life. The researchers also assessed negative thinking using the Inference Questionnaire. Blinded raters assessed outcomes.

Sustained improvements

Thirty-seven patients were randomized to receive telephone-based CBT, and 35 were randomized to treatment as usual. Overall, 70% were taking antidepressants, and 14% continued receiving psychotherapy from community providers of their choice during the trial. Participants’ average age was 65 years, and 51% were female.

Post treatment, mean improvement in HAM-D score from baseline was 6.53 points in the telephone-based CBT group, compared with −0.27 points in the control group. “Effects at the end of treatment were maintained at 6-month follow-up,” the researchers reported.

About 40% of patients in the CBT group reported that their depression was much improved or very much improved, compared with none of the patients in the control group. Responders had mild to minimal symptomatology on the HAM-D, which indicates that the changes were clinically significant, the authors said.

Secondary outcomes also favored telephone-based CBT. “The intervention was feasible and highly acceptable, yielding an 88% retention rate over the 9-month trial,” Dr. Dobkin and colleagues said.

Compared with other control conditions, treatment-as-usual controls may enhance the effect size of an intervention, the authors noted. In addition, factors such as therapeutic relationship, time, and attention likely contribute to psychotherapy outcomes.

Success may hinge on cognitive ability

“The success of this trial highlights the need for further efficacy studies targeting neuropsychiatric manifestations of [Parkinson’s disease] and adds urgency to the discussion over policies regarding access to tele–mental health, especially for vulnerable populations with limited access to in-person mental health services,” Gregory M. Pontone, MD, and Kelly A. Mills, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Pontone and Dr. Mills are affiliated with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“Only rudimentary evidence” exists to guide the treatment of depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease, the editorialists said. “Patient preference and tolerability suggest that nonpharmacologic therapies, such as CBT, are preferred as first-line treatment. Yet access to qualified CBT practitioners, especially those with a clinical knowledge of [Parkinson’s disease], is limited.”

Despite its advantages and the encouraging results, CBT may have important limitations as well, they said. Patients require a certain degree of cognitive ability to benefit from CBT, and the prevalence of dementia among patients with Parkinson’s disease is about 30%.

Nevertheless, the trial provided evidence of target engagement. “Though caveats include the single-blind design and potential confounding by time spent with patient and caregiver, the authors demonstrated that improvement was mediated by the mechanism of CBT – a reduction in negative thinking.”

The trial was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Parkinson’s Alliance (Parkinson’s Unity Walk). Dr. Mills disclosed a patent pending for a system for phase-dependent cortical brain stimulation, National Institutes of Health funding, pending funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and commercial research support from Global Kinetics Corporation. Dr. Pontone is a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Dobkin RD et al. Neurology. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009292.

FROM NEUROLOGY

IV esketamine, ketamine equally effective for resistant depression

Intravenous (IV) esketamine is as safe and effective as IV ketamine for patients with treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

“Our study was the first randomized clinical trial directly comparing ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression,” senior investigator Lucas C. Quarantini, MD, PhD, division of psychiatry, Professor Edgard Santos University Hospital, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil, said in an interview.

The findings showed that esketamine was not inferior to ketamine in remission of depressive symptoms 24 hours after a single IV dose, and the two treatments had similar side effect profiles, Dr. Quarantini said.

Furthermore, “our results showed that only the number of treatment failures was an important factor for the remission of symptoms,” he added.

The findings were scheduled to be presented at the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) Conference 2020, along with publication in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2020 Mar 1;264:527-34). However, the ADAA conference was canceled in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

More treatment options

The randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared IV racemic ketamine and esketamine, two formulations of the glutamate NMDA receptor modulator drug. It included 63 participants (61.9% women; mean age, 47 years) with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, as determined by DSM-5 criteria.

Participants were enrolled between March 2017 and June 2018 and randomized to receive a single subanesthetic dose of racemic ketamine (0.5 mg/kg; n = 29) or esketamine (0.25 mg/kg; n = 34) for 40 minutes.

Results showed esketamine to be noninferior to ketamine as determined by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

The difference of just 5.3% confirmed noninferiority.

Although ketamine showed a tendency to have a longer-lasting antidepressant effect compared with esketamine, the difference did not reach statistical significance and should be evaluated in future studies, the investigators noted.

Both treatments were safe and well tolerated. Consistent with previous studies, the most frequent side effects were dissociative symptoms, including derealization, depersonalization, and cardiovascular changes, and increased blood pressure and heart rate, which occurred equally in both groups. There were no serious adverse events in either study group.

The investigators noted that most of the previous research examining antidepressant effects of ketamine has used the IV racemic type. The current findings are particularly important for situations in which ketamine or intranasal esketamine, which was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, are unavailable, Dr. Quarantini said.

“What our study adds to what has been previously published is that the only way to really analyze if two drugs are equivalent is to compare them in a head-to-head trial; and that was what we did,” he said.

“Our findings bring a greater basis for practitioners from locations where intravenous esketamine is more easily obtainable than ketamine to use it as an affordable option for treating depressive patients,” Dr. Quarantini added.

“Since this [lack of availability] is the scenario here in Brazil, and probably in many other countries, all patients from these locations will benefit from this finding,” he said.

While further evaluating the study results to determine which clinical characteristics were predictive of remission of depressive symptoms, the researchers assessed several key factors. The median duration of disease progression was 12 months, median number of depressive episodes was five, and median number of therapeutic treatment failures was three.

The investigators also looked at the number of suicide attempts and degree of dissociative behavior.

Of these factors, the number of therapeutic failures was the only significant predictor of symptom remission, with an odds ratio of 1.46 for each prior therapeutic failure (95% CI, 1.08-1.99).

“To date, we have not found [other] studies with similar data,” Dr. Quarantini noted.

“Identifying remission predictors may contribute to selecting more suitable candidates for the intervention and result in more individualized and effective patient management,” the investigators wrote.

Consistent findings

Commenting on the findings, Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that key study limitations include the small sample size and lack of a placebo group.

Nevertheless, “I think it is fair to say that it is unlikely that the treatments are markedly different in their effects on depression over 24 hours,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Sanacora, director of the Yale Depression Research Program, was not involved with the current research.

The findings are “consistent with what we can extrapolate from other clinical trials examining racemic ketamine and esketamine separately,” he said.

Dr. Sanacora noted that because esketamine has been previously shown to be a more potent anesthetic than arketamine, the other component of racemic ketamine, it is “the primary form of ketamine used as an anesthetic agent in several regions of the world with the idea that it may be more selective for the desired anesthetic effect.”

Even with its limitations, the study does offer some notable yet preliminary insights, he added.

“It is interesting to see varying degrees of numerical differences between the two treatments at different time points,” Dr. Sanacora said. In addition, “there may be some differing effects between the two treatments over time, but we really do not have enough data to say much of anything [about that] with confidence at this point.”

The study was supported by the Programa de Pesquisa para o SUS through Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia. Dr. Quarantini has reported receiving consulting fees from Allergan, Abbott, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Lundbeck, and research fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The other study authors’ disclosures are listed in the published article. Dr. Sanacora has reported consulting and/or conducting research from several pharmaceutical companies. He also holds shares in BioHaven Pharmaceuticals and is coinventor on a patent called “Glutamate Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intravenous (IV) esketamine is as safe and effective as IV ketamine for patients with treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

“Our study was the first randomized clinical trial directly comparing ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression,” senior investigator Lucas C. Quarantini, MD, PhD, division of psychiatry, Professor Edgard Santos University Hospital, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil, said in an interview.

The findings showed that esketamine was not inferior to ketamine in remission of depressive symptoms 24 hours after a single IV dose, and the two treatments had similar side effect profiles, Dr. Quarantini said.

Furthermore, “our results showed that only the number of treatment failures was an important factor for the remission of symptoms,” he added.

The findings were scheduled to be presented at the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) Conference 2020, along with publication in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2020 Mar 1;264:527-34). However, the ADAA conference was canceled in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

More treatment options

The randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared IV racemic ketamine and esketamine, two formulations of the glutamate NMDA receptor modulator drug. It included 63 participants (61.9% women; mean age, 47 years) with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, as determined by DSM-5 criteria.

Participants were enrolled between March 2017 and June 2018 and randomized to receive a single subanesthetic dose of racemic ketamine (0.5 mg/kg; n = 29) or esketamine (0.25 mg/kg; n = 34) for 40 minutes.

Results showed esketamine to be noninferior to ketamine as determined by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

The difference of just 5.3% confirmed noninferiority.

Although ketamine showed a tendency to have a longer-lasting antidepressant effect compared with esketamine, the difference did not reach statistical significance and should be evaluated in future studies, the investigators noted.

Both treatments were safe and well tolerated. Consistent with previous studies, the most frequent side effects were dissociative symptoms, including derealization, depersonalization, and cardiovascular changes, and increased blood pressure and heart rate, which occurred equally in both groups. There were no serious adverse events in either study group.

The investigators noted that most of the previous research examining antidepressant effects of ketamine has used the IV racemic type. The current findings are particularly important for situations in which ketamine or intranasal esketamine, which was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, are unavailable, Dr. Quarantini said.

“What our study adds to what has been previously published is that the only way to really analyze if two drugs are equivalent is to compare them in a head-to-head trial; and that was what we did,” he said.

“Our findings bring a greater basis for practitioners from locations where intravenous esketamine is more easily obtainable than ketamine to use it as an affordable option for treating depressive patients,” Dr. Quarantini added.

“Since this [lack of availability] is the scenario here in Brazil, and probably in many other countries, all patients from these locations will benefit from this finding,” he said.

While further evaluating the study results to determine which clinical characteristics were predictive of remission of depressive symptoms, the researchers assessed several key factors. The median duration of disease progression was 12 months, median number of depressive episodes was five, and median number of therapeutic treatment failures was three.

The investigators also looked at the number of suicide attempts and degree of dissociative behavior.

Of these factors, the number of therapeutic failures was the only significant predictor of symptom remission, with an odds ratio of 1.46 for each prior therapeutic failure (95% CI, 1.08-1.99).

“To date, we have not found [other] studies with similar data,” Dr. Quarantini noted.

“Identifying remission predictors may contribute to selecting more suitable candidates for the intervention and result in more individualized and effective patient management,” the investigators wrote.

Consistent findings

Commenting on the findings, Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that key study limitations include the small sample size and lack of a placebo group.

Nevertheless, “I think it is fair to say that it is unlikely that the treatments are markedly different in their effects on depression over 24 hours,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Sanacora, director of the Yale Depression Research Program, was not involved with the current research.

The findings are “consistent with what we can extrapolate from other clinical trials examining racemic ketamine and esketamine separately,” he said.

Dr. Sanacora noted that because esketamine has been previously shown to be a more potent anesthetic than arketamine, the other component of racemic ketamine, it is “the primary form of ketamine used as an anesthetic agent in several regions of the world with the idea that it may be more selective for the desired anesthetic effect.”

Even with its limitations, the study does offer some notable yet preliminary insights, he added.

“It is interesting to see varying degrees of numerical differences between the two treatments at different time points,” Dr. Sanacora said. In addition, “there may be some differing effects between the two treatments over time, but we really do not have enough data to say much of anything [about that] with confidence at this point.”

The study was supported by the Programa de Pesquisa para o SUS through Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia. Dr. Quarantini has reported receiving consulting fees from Allergan, Abbott, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Lundbeck, and research fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The other study authors’ disclosures are listed in the published article. Dr. Sanacora has reported consulting and/or conducting research from several pharmaceutical companies. He also holds shares in BioHaven Pharmaceuticals and is coinventor on a patent called “Glutamate Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intravenous (IV) esketamine is as safe and effective as IV ketamine for patients with treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

“Our study was the first randomized clinical trial directly comparing ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression,” senior investigator Lucas C. Quarantini, MD, PhD, division of psychiatry, Professor Edgard Santos University Hospital, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil, said in an interview.

The findings showed that esketamine was not inferior to ketamine in remission of depressive symptoms 24 hours after a single IV dose, and the two treatments had similar side effect profiles, Dr. Quarantini said.

Furthermore, “our results showed that only the number of treatment failures was an important factor for the remission of symptoms,” he added.

The findings were scheduled to be presented at the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) Conference 2020, along with publication in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2020 Mar 1;264:527-34). However, the ADAA conference was canceled in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

More treatment options

The randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared IV racemic ketamine and esketamine, two formulations of the glutamate NMDA receptor modulator drug. It included 63 participants (61.9% women; mean age, 47 years) with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, as determined by DSM-5 criteria.

Participants were enrolled between March 2017 and June 2018 and randomized to receive a single subanesthetic dose of racemic ketamine (0.5 mg/kg; n = 29) or esketamine (0.25 mg/kg; n = 34) for 40 minutes.

Results showed esketamine to be noninferior to ketamine as determined by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

The difference of just 5.3% confirmed noninferiority.

Although ketamine showed a tendency to have a longer-lasting antidepressant effect compared with esketamine, the difference did not reach statistical significance and should be evaluated in future studies, the investigators noted.

Both treatments were safe and well tolerated. Consistent with previous studies, the most frequent side effects were dissociative symptoms, including derealization, depersonalization, and cardiovascular changes, and increased blood pressure and heart rate, which occurred equally in both groups. There were no serious adverse events in either study group.

The investigators noted that most of the previous research examining antidepressant effects of ketamine has used the IV racemic type. The current findings are particularly important for situations in which ketamine or intranasal esketamine, which was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, are unavailable, Dr. Quarantini said.

“What our study adds to what has been previously published is that the only way to really analyze if two drugs are equivalent is to compare them in a head-to-head trial; and that was what we did,” he said.

“Our findings bring a greater basis for practitioners from locations where intravenous esketamine is more easily obtainable than ketamine to use it as an affordable option for treating depressive patients,” Dr. Quarantini added.

“Since this [lack of availability] is the scenario here in Brazil, and probably in many other countries, all patients from these locations will benefit from this finding,” he said.

While further evaluating the study results to determine which clinical characteristics were predictive of remission of depressive symptoms, the researchers assessed several key factors. The median duration of disease progression was 12 months, median number of depressive episodes was five, and median number of therapeutic treatment failures was three.

The investigators also looked at the number of suicide attempts and degree of dissociative behavior.

Of these factors, the number of therapeutic failures was the only significant predictor of symptom remission, with an odds ratio of 1.46 for each prior therapeutic failure (95% CI, 1.08-1.99).

“To date, we have not found [other] studies with similar data,” Dr. Quarantini noted.

“Identifying remission predictors may contribute to selecting more suitable candidates for the intervention and result in more individualized and effective patient management,” the investigators wrote.

Consistent findings

Commenting on the findings, Gerard Sanacora, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that key study limitations include the small sample size and lack of a placebo group.

Nevertheless, “I think it is fair to say that it is unlikely that the treatments are markedly different in their effects on depression over 24 hours,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Sanacora, director of the Yale Depression Research Program, was not involved with the current research.

The findings are “consistent with what we can extrapolate from other clinical trials examining racemic ketamine and esketamine separately,” he said.

Dr. Sanacora noted that because esketamine has been previously shown to be a more potent anesthetic than arketamine, the other component of racemic ketamine, it is “the primary form of ketamine used as an anesthetic agent in several regions of the world with the idea that it may be more selective for the desired anesthetic effect.”

Even with its limitations, the study does offer some notable yet preliminary insights, he added.

“It is interesting to see varying degrees of numerical differences between the two treatments at different time points,” Dr. Sanacora said. In addition, “there may be some differing effects between the two treatments over time, but we really do not have enough data to say much of anything [about that] with confidence at this point.”

The study was supported by the Programa de Pesquisa para o SUS through Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia. Dr. Quarantini has reported receiving consulting fees from Allergan, Abbott, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Lundbeck, and research fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The other study authors’ disclosures are listed in the published article. Dr. Sanacora has reported consulting and/or conducting research from several pharmaceutical companies. He also holds shares in BioHaven Pharmaceuticals and is coinventor on a patent called “Glutamate Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19: Mental health pros come to the aid of frontline comrades

Frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers across North America are dealing with unprecedented stress, but mental health therapists in both Canada and the US are doing their part to ensure the psychological well-being of their colleagues on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of licensed psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers have signed up to offer free therapy sessions to healthcare professionals who find themselves psychologically overwhelmed by the pandemic’s economic, social, and financial fallout.

In Canada, the movement was started by Toronto psychotherapist Karen Dougherty, MA, who saw a social media post from someone in New York asking mental health workers to volunteer their time.

Inspired by this, Dougherty reached out to some of her close colleagues with a social media post of her own. A few days later, 450 people had signed up to volunteer and Ontario COVID-19 Therapists was born.

The sessions are provided by licensed Canadian psychotherapists and are free of charge to healthcare workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. After signing up online, users can choose from one of three therapists who will provide up to five free phone sessions.

In New York state, a similar initiative — which is not limited to healthcare workers — has gained incredible momentum. On March 21, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the creation of a statewide hotline [844-863-9314] to provide free mental health services to individuals sheltering at home who may be experiencing stress and anxiety as a result of COVID-19.

The governor called on mental-health professionals to volunteer their time and provide telephone and/or telehealth counseling. The New York State Psychiatric Association quickly got on board and encouraged its members to participate.

Just four days later, more than 6,000 mental health workers had volunteered their services, making New York the first state to address the mental health consequences of the pandemic in this way.

Self-care is vital for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as stress mounts and workdays become longer and grimmer. Dougherty recommended that frontline workers manage overwhelming thoughts by limiting their intake of information about the virus.

Self-Care a “Selfless Act”

Clinicians need to balance the need to stay informed with the potential for information overload, which can contribute to anxiety, she said.

She also recommended that individuals continue to connect with loved ones while practicing social distancing. Equally important is talking to someone about the struggles people may be facing at work.

For Amin Azzam MD, MA, the benefits of these initiatives are obvious.

“There is always value in providing additional mental health services and tending to psychological well-being,” Azzam, adjunct professor of psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and UC Berkeley, told Medscape Medical News.

“If there ever were a time when we can use all the emotional support possible, then it would be during a global pandemic,” added Azzam, who is also director of Open Learning Initiatives at Osmosis, a nonprofit health education company.

Azzam urged healthcare professionals to avail themselves of such resources as often as necessary.

“Taking care of ourselves is not a selfish act. When the oxygen masks come down on airplanes we are always instructed to put our own masks on first before helping those in need. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness, to seek emotional support,” he said.

However, it isn’t always easy. The longstanding stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues has not stopped for COVID-19. Even workers who are in close daily contact with people infected with the virus are finding they’re not immune to the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment, Azzam added.

“Nevertheless, the burden these frontline workers are facing is real…and often crushing. Some Ontario doctors have reported pretraumatic stress disorder, which they attribute to having watched the virus wreak havoc in other countries, and knowing that similar difficulties are headed their way,” he said.

A Growing Movement

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, the CEO of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), said the province’s nurses are under intense pressure at work, then fear infecting family members once they come home. Some are even staying at hotels to ensure they don’t infect others, as reported by CBC News.

However, she added, most recognize the important role that psychotherapy can play, especially since many frontline healthcare workers find it difficult to speak with their families about the issues they face at work, for fear of adding stress to their family life as well.

“None of us are superhuman and immune to stress. When healthcare workers are facing workplace challenges never before seen in their lifetimes, they need opportunities to decompress to maintain their own health and well-being. This will help them pace themselves for the marathon — not sprint — to continue doing the important work of helping others,” said Azzam.

Given the attention it has garnered in such a short time, Azzam is hopeful that the free therapy movement will spread.

In Canada, mental health professionals in other provinces have already reached out to Dougherty, lending credence to the notion of a pan-Canadian network of therapists offering free services to healthcare workers during the outbreak.

In the US, other local initiatives are already underway.

“The one that I’m personally aware of is at my home institution at the University of California, San Francisco,” Azzam said. “We have a Care for the Caregiver program that is being greatly expanded at this time. As part of that initiative, the institution’s psychiatry department has solicited licensed mental health care providers to volunteer their time to provide those additional services.”

Azzam has also worked with colleagues developing a series of mental health tools that Osmosis has made available free of charge.

These include a central site with educational material about COVID-19, a video about supporting educators’ mental health during high-stress periods; a video about managing students’ mental health during public health emergencies; a summary of recommended resources for psychological health in distressing times; and a YouTube Live event he held regarding tips for maximizing psychological health during stressful times.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers across North America are dealing with unprecedented stress, but mental health therapists in both Canada and the US are doing their part to ensure the psychological well-being of their colleagues on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of licensed psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers have signed up to offer free therapy sessions to healthcare professionals who find themselves psychologically overwhelmed by the pandemic’s economic, social, and financial fallout.

In Canada, the movement was started by Toronto psychotherapist Karen Dougherty, MA, who saw a social media post from someone in New York asking mental health workers to volunteer their time.

Inspired by this, Dougherty reached out to some of her close colleagues with a social media post of her own. A few days later, 450 people had signed up to volunteer and Ontario COVID-19 Therapists was born.

The sessions are provided by licensed Canadian psychotherapists and are free of charge to healthcare workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. After signing up online, users can choose from one of three therapists who will provide up to five free phone sessions.

In New York state, a similar initiative — which is not limited to healthcare workers — has gained incredible momentum. On March 21, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the creation of a statewide hotline [844-863-9314] to provide free mental health services to individuals sheltering at home who may be experiencing stress and anxiety as a result of COVID-19.

The governor called on mental-health professionals to volunteer their time and provide telephone and/or telehealth counseling. The New York State Psychiatric Association quickly got on board and encouraged its members to participate.

Just four days later, more than 6,000 mental health workers had volunteered their services, making New York the first state to address the mental health consequences of the pandemic in this way.

Self-care is vital for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as stress mounts and workdays become longer and grimmer. Dougherty recommended that frontline workers manage overwhelming thoughts by limiting their intake of information about the virus.

Self-Care a “Selfless Act”

Clinicians need to balance the need to stay informed with the potential for information overload, which can contribute to anxiety, she said.

She also recommended that individuals continue to connect with loved ones while practicing social distancing. Equally important is talking to someone about the struggles people may be facing at work.

For Amin Azzam MD, MA, the benefits of these initiatives are obvious.

“There is always value in providing additional mental health services and tending to psychological well-being,” Azzam, adjunct professor of psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and UC Berkeley, told Medscape Medical News.

“If there ever were a time when we can use all the emotional support possible, then it would be during a global pandemic,” added Azzam, who is also director of Open Learning Initiatives at Osmosis, a nonprofit health education company.

Azzam urged healthcare professionals to avail themselves of such resources as often as necessary.

“Taking care of ourselves is not a selfish act. When the oxygen masks come down on airplanes we are always instructed to put our own masks on first before helping those in need. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness, to seek emotional support,” he said.

However, it isn’t always easy. The longstanding stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues has not stopped for COVID-19. Even workers who are in close daily contact with people infected with the virus are finding they’re not immune to the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment, Azzam added.

“Nevertheless, the burden these frontline workers are facing is real…and often crushing. Some Ontario doctors have reported pretraumatic stress disorder, which they attribute to having watched the virus wreak havoc in other countries, and knowing that similar difficulties are headed their way,” he said.

A Growing Movement

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, the CEO of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), said the province’s nurses are under intense pressure at work, then fear infecting family members once they come home. Some are even staying at hotels to ensure they don’t infect others, as reported by CBC News.

However, she added, most recognize the important role that psychotherapy can play, especially since many frontline healthcare workers find it difficult to speak with their families about the issues they face at work, for fear of adding stress to their family life as well.

“None of us are superhuman and immune to stress. When healthcare workers are facing workplace challenges never before seen in their lifetimes, they need opportunities to decompress to maintain their own health and well-being. This will help them pace themselves for the marathon — not sprint — to continue doing the important work of helping others,” said Azzam.

Given the attention it has garnered in such a short time, Azzam is hopeful that the free therapy movement will spread.

In Canada, mental health professionals in other provinces have already reached out to Dougherty, lending credence to the notion of a pan-Canadian network of therapists offering free services to healthcare workers during the outbreak.

In the US, other local initiatives are already underway.

“The one that I’m personally aware of is at my home institution at the University of California, San Francisco,” Azzam said. “We have a Care for the Caregiver program that is being greatly expanded at this time. As part of that initiative, the institution’s psychiatry department has solicited licensed mental health care providers to volunteer their time to provide those additional services.”

Azzam has also worked with colleagues developing a series of mental health tools that Osmosis has made available free of charge.

These include a central site with educational material about COVID-19, a video about supporting educators’ mental health during high-stress periods; a video about managing students’ mental health during public health emergencies; a summary of recommended resources for psychological health in distressing times; and a YouTube Live event he held regarding tips for maximizing psychological health during stressful times.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers across North America are dealing with unprecedented stress, but mental health therapists in both Canada and the US are doing their part to ensure the psychological well-being of their colleagues on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of licensed psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers have signed up to offer free therapy sessions to healthcare professionals who find themselves psychologically overwhelmed by the pandemic’s economic, social, and financial fallout.

In Canada, the movement was started by Toronto psychotherapist Karen Dougherty, MA, who saw a social media post from someone in New York asking mental health workers to volunteer their time.

Inspired by this, Dougherty reached out to some of her close colleagues with a social media post of her own. A few days later, 450 people had signed up to volunteer and Ontario COVID-19 Therapists was born.

The sessions are provided by licensed Canadian psychotherapists and are free of charge to healthcare workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. After signing up online, users can choose from one of three therapists who will provide up to five free phone sessions.

In New York state, a similar initiative — which is not limited to healthcare workers — has gained incredible momentum. On March 21, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the creation of a statewide hotline [844-863-9314] to provide free mental health services to individuals sheltering at home who may be experiencing stress and anxiety as a result of COVID-19.

The governor called on mental-health professionals to volunteer their time and provide telephone and/or telehealth counseling. The New York State Psychiatric Association quickly got on board and encouraged its members to participate.

Just four days later, more than 6,000 mental health workers had volunteered their services, making New York the first state to address the mental health consequences of the pandemic in this way.

Self-care is vital for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as stress mounts and workdays become longer and grimmer. Dougherty recommended that frontline workers manage overwhelming thoughts by limiting their intake of information about the virus.

Self-Care a “Selfless Act”

Clinicians need to balance the need to stay informed with the potential for information overload, which can contribute to anxiety, she said.

She also recommended that individuals continue to connect with loved ones while practicing social distancing. Equally important is talking to someone about the struggles people may be facing at work.

For Amin Azzam MD, MA, the benefits of these initiatives are obvious.

“There is always value in providing additional mental health services and tending to psychological well-being,” Azzam, adjunct professor of psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and UC Berkeley, told Medscape Medical News.

“If there ever were a time when we can use all the emotional support possible, then it would be during a global pandemic,” added Azzam, who is also director of Open Learning Initiatives at Osmosis, a nonprofit health education company.

Azzam urged healthcare professionals to avail themselves of such resources as often as necessary.

“Taking care of ourselves is not a selfish act. When the oxygen masks come down on airplanes we are always instructed to put our own masks on first before helping those in need. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness, to seek emotional support,” he said.

However, it isn’t always easy. The longstanding stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues has not stopped for COVID-19. Even workers who are in close daily contact with people infected with the virus are finding they’re not immune to the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment, Azzam added.

“Nevertheless, the burden these frontline workers are facing is real…and often crushing. Some Ontario doctors have reported pretraumatic stress disorder, which they attribute to having watched the virus wreak havoc in other countries, and knowing that similar difficulties are headed their way,” he said.

A Growing Movement

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, the CEO of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), said the province’s nurses are under intense pressure at work, then fear infecting family members once they come home. Some are even staying at hotels to ensure they don’t infect others, as reported by CBC News.

However, she added, most recognize the important role that psychotherapy can play, especially since many frontline healthcare workers find it difficult to speak with their families about the issues they face at work, for fear of adding stress to their family life as well.

“None of us are superhuman and immune to stress. When healthcare workers are facing workplace challenges never before seen in their lifetimes, they need opportunities to decompress to maintain their own health and well-being. This will help them pace themselves for the marathon — not sprint — to continue doing the important work of helping others,” said Azzam.

Given the attention it has garnered in such a short time, Azzam is hopeful that the free therapy movement will spread.

In Canada, mental health professionals in other provinces have already reached out to Dougherty, lending credence to the notion of a pan-Canadian network of therapists offering free services to healthcare workers during the outbreak.

In the US, other local initiatives are already underway.

“The one that I’m personally aware of is at my home institution at the University of California, San Francisco,” Azzam said. “We have a Care for the Caregiver program that is being greatly expanded at this time. As part of that initiative, the institution’s psychiatry department has solicited licensed mental health care providers to volunteer their time to provide those additional services.”

Azzam has also worked with colleagues developing a series of mental health tools that Osmosis has made available free of charge.

These include a central site with educational material about COVID-19, a video about supporting educators’ mental health during high-stress periods; a video about managing students’ mental health during public health emergencies; a summary of recommended resources for psychological health in distressing times; and a YouTube Live event he held regarding tips for maximizing psychological health during stressful times.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Routinely screen for depression in atopic dermatitis

Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, declared in a video presentation during a virtual meeting held by the George Washington University department of dermatology.

The virtual meeting included presentations that had been slated for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Silverberg presented highlights of his recent study of depression screening rates in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, an annual population-based survey by the National Center for Health Statistics. He and his coinvestigator analyzed 9,345 office visits for atopic dermatitis (AD) and 2,085 for psoriasis (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Oct 24. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18629.). The picture that emerged showed that there is much room for improvement.

“We found that depression screening rates were abysmally low in atopic dermatitis patients, with less than 2% patients being screened. There was very little difference in screening rates between patients on an advanced therapy, like systemic phototherapy or a biologic, compared to those who were just on topical therapy alone, meaning even the more severe patients aren’t being asked these questions. And no difference between dermatologists and primary care physicians,” said Dr. Silverberg, director of clinical research and contact dermatitis in the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

For Dr. Silverberg, known for his pioneering work documenting the marked yet often-underappreciated negative impact of AD on quality of life and mental health, these rock-bottom screening rates were particularly galling.

“There are very high rates of anxiety and depression amongst our patients with atopic dermatitis,” the dermatologist emphasized. “Mental health symptoms are an incredibly important domain in atopic dermatitis that we need to ask our patients about. We don’t ask enough.

“This to me is actually a very important symptom to measure. It’s not just a theoretical construct involved in understanding the burden of the disease, it’s something that’s actionable because most of these cases of mental health symptoms are reversible or modifiable with improved control of the atopic dermatitis,” he continued. “I use this as an indication to step up therapy. If a patient is clinically depressed and we believe that’s secondary to their chronic atopic dermatitis, this is a reason to step up therapy to something stronger.”

If the depressive symptoms don’t improve after stepping up the intensity of the dermatologic therapy, it’s probably time for the patient to see a mental health professional, Dr. Silverberg advised, adding, “I’m not telling every dermatology resident out there to become a psychiatrist.”

Depression and anxiety in AD: How common?

In an analysis of multiyear data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys, an annual population-based project conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Dr. Silverberg and a coinvestigator found that adults with AD were an adjusted 186% more likely than those without AD to screen positive for depressive symptoms on the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), with rates of 44.3% and 21.9%, respectively. The AD patients were also 500% more likely to screen positive for severe psychological distress, with a 25.9% rate of having a Kessler-6 index score of 13 or more, compared with 5.5% in adults without AD.

The rate of severe psychological distress was higher in adults with AD than in those with asthma, diabetes, hypertension, urticaria, or psoriasis, and was comparable with the rate in individuals with autoimmune disease (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019 Aug;123[2]:179-85).

“It’s surprising when you think that the majority of the cases of atopic dermatitis in the population are mild and yet when you look at a population-based sample such as this you see a strong signal come up. It means that, with all the dilution of mild disease, the signal is still there. It emphasizes that even patients with mild disease get these depressive symptoms and psychosocial distress,” Dr. Silverberg observed.

In a separate analysis of the same national database, this time looking at Short Form-6D health utility scores – a measure of overall quality of life encompassing key domains including vitality, physical function, mental health, fatigue – adults with AD scored markedly worse than individuals with no chronic health disorders. Health utility scores were particularly low in adults with AD and comorbid symptoms of anxiety or depression, suggesting that those affective symptoms are major drivers of the demonstrably poor quality of life in adult AD (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020 Jan;124[1]:88-9).

In the Atopic Dermatitis in America Study, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators cross-sectionally surveyed 2,893 adults using the seven-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) assessment instruments. Individuals with AD as determined using the modified U.K. Diagnostic Criteria had dramatically higher rates of both depression and anxiety. For example, the prevalence of a HADS-A score of 11 or more, which is considered to be case finding for clinically important anxiety, was 28.6% in adults with AD, nearly twice the 15.5% prevalence in those without the dermatologic disease. A HADS-D score of 11 or greater was present in 13.5% of subjects with AD and 9% of those without.

HADS-A and -D scores were higher in adults with moderate AD, compared with mild disease, and higher still in those with severe AD. Indeed, virtually all individuals with moderate to severe AD had symptoms of anxiety and depression, which in a large proportion had gone undiagnosed. A multivariate analysis strongly suggested that AD severity was the major driver of anxiety and depression in adults with AD (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Sep;181[3]:554-65).

An important finding was that 100% of adults with AD who had scores in the severe range on three validated measures of itch, frequency of symptoms, and lesion severity had borderline or abnormal scores on the HADS-A and -D.

“Of course, if you don’t ask, you’re not going to know about it,” Dr. Silverberg noted.

Dr. Silverberg reported receiving research grants from Galderma and GlaxoSmithKline and serving as a consultant to those pharmaceutical companies and more than a dozen others.

Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, declared in a video presentation during a virtual meeting held by the George Washington University department of dermatology.

The virtual meeting included presentations that had been slated for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Silverberg presented highlights of his recent study of depression screening rates in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, an annual population-based survey by the National Center for Health Statistics. He and his coinvestigator analyzed 9,345 office visits for atopic dermatitis (AD) and 2,085 for psoriasis (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Oct 24. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18629.). The picture that emerged showed that there is much room for improvement.

“We found that depression screening rates were abysmally low in atopic dermatitis patients, with less than 2% patients being screened. There was very little difference in screening rates between patients on an advanced therapy, like systemic phototherapy or a biologic, compared to those who were just on topical therapy alone, meaning even the more severe patients aren’t being asked these questions. And no difference between dermatologists and primary care physicians,” said Dr. Silverberg, director of clinical research and contact dermatitis in the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

For Dr. Silverberg, known for his pioneering work documenting the marked yet often-underappreciated negative impact of AD on quality of life and mental health, these rock-bottom screening rates were particularly galling.

“There are very high rates of anxiety and depression amongst our patients with atopic dermatitis,” the dermatologist emphasized. “Mental health symptoms are an incredibly important domain in atopic dermatitis that we need to ask our patients about. We don’t ask enough.

“This to me is actually a very important symptom to measure. It’s not just a theoretical construct involved in understanding the burden of the disease, it’s something that’s actionable because most of these cases of mental health symptoms are reversible or modifiable with improved control of the atopic dermatitis,” he continued. “I use this as an indication to step up therapy. If a patient is clinically depressed and we believe that’s secondary to their chronic atopic dermatitis, this is a reason to step up therapy to something stronger.”

If the depressive symptoms don’t improve after stepping up the intensity of the dermatologic therapy, it’s probably time for the patient to see a mental health professional, Dr. Silverberg advised, adding, “I’m not telling every dermatology resident out there to become a psychiatrist.”

Depression and anxiety in AD: How common?