User login

Study highlights impact of acne in adult women on quality of life, mental health

results from a qualitative study demonstrated.

“Nearly 50% of women experience acne in their 20s, and 35% experience acne in their 30s,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, formerly of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization. “While several qualitative studies have examined acne in adolescence, the lived experience of adult female acne has not been explored in detail and prior studies have included relatively few patients. As a result, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews among adult women with acne to examine the lived experience of adult acne and its treatment.”

For the study, published online July 28, 2021, in JAMA Dermatology, Dr. Barbieri and colleagues conducted voluntary, confidential phone interviews with 50 women aged between 18 and 40 years with moderate to severe acne who were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania Health System and from a private dermatology clinic in Cincinnati. They used free listing and open-ended, semistructured interviews to elicit opinions from the women on how acne affected their lives; their experience with acne treatments, dermatologists, and health care systems; as well as their views on treatment success.

The mean age of the participants was 28 years and 48% were white (10% were Black, 8% were Asian, 4% were more than one race, and the rest abstained from answering this question; 10% said they were Hispanic).

More than three-quarters (78%) reported prior treatment with topical retinoids, followed by spironolactone (70%), topical antibiotics (43%), combined oral contraceptives (43%), and isotretinoin (41%). During the free-listing part of interviews, where the women reported the first words that came to their mind when asked about success of treatment and adverse effects, the most important terms expressed related to treatment success were clear skin, no scarring, and no acne. The most important terms related to treatment adverse effects were dryness, redness, and burning.

In the semistructured interview portion of the study, the main themes expressed were acne-related concerns about appearance, including feeling less confident at work; mental and emotional health, including feelings of depression, anxiety, depression, and low self-worth during acne breakouts; and everyday life impact, including the notion that acne affected how other people perceived them. The other main themes included successful treatment, with clear skin and having a manageable number of lesions being desirable outcomes; and interactions with health care, including varied experiences with dermatologists. The researchers observed that most participants did not think oral antibiotics were appropriate treatments for their acne, specifically because of limited long-term effectiveness.

“Many patients described frustration with finding a dermatologist with whom they were comfortable and with identifying effective treatments for their acne,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, those who thought their dermatologist listened to their concerns and individualized their treatment plan reported higher levels of satisfaction.”

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri, who is now with the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he was surprised by how many patients expressed interest in nonantibiotic treatments for acne, “given that oral antibiotics are by far the most commonly prescribed systemic treatment for acne.”

Moreover, he added, “although I have experienced many patients being hesitant about isotretinoin, I was surprised by how strong patients’ concerns were about isotretinoin side effects. Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions about isotretinoin that limit use of this treatment that can be highly effective and safe for the appropriate patient.”

In an accompanying editorial, dermatologists Diane M. Thiboutot, MD and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, with Penn State University, Hershey, and Alison M. Layton, MB, ChB, with the Harrogate Foundation Trust, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, wrote that the findings from the study “resonate with those recently reported in several international studies that examine the impacts of acne, how patients assess treatment success, and what is important to measure from a patient and health care professional perspective in a clinical trial for acne.”

A large systematic review on the impact of acne on patients, conducted by the Acne Core Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), found that “appearance-related concerns and negative psychosocial effects were found to be a major impact of acne,” they noted. “Surprisingly, only 22 of the 473 studies identified in this review included qualitative data gathered from patient interviews. It is encouraging to see the concordance between the concerns voiced by the participants in the current study and those identified from the literature review, wherein a variety of methods were used to assess acne impacts.”

For his part, Dr. Barbieri said that the study findings “justify the importance of having a discussion with patients about their unique lived experience of acne and individualizing treatment to their specific needs. Patient reported outcome measures could be a useful adjunctive tool to capture these impacts on quality of life.”

This study was funded by grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he received partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Thiboutot reported receiving consultant fees from Galderma and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Layton reported receiving unrestricted educational presentation, advisory board, and consultancy fees from Galderma Honoraria; unrestricted educational presentation and advisory board honoraria from Leo; advisory board honoraria from Novartis and Mylan; consultancy honoraria from Procter and Gamble and Meda; grants from Galderma; and consultancy and advisory board honoraria from Origimm outside the submitted work.

results from a qualitative study demonstrated.

“Nearly 50% of women experience acne in their 20s, and 35% experience acne in their 30s,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, formerly of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization. “While several qualitative studies have examined acne in adolescence, the lived experience of adult female acne has not been explored in detail and prior studies have included relatively few patients. As a result, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews among adult women with acne to examine the lived experience of adult acne and its treatment.”

For the study, published online July 28, 2021, in JAMA Dermatology, Dr. Barbieri and colleagues conducted voluntary, confidential phone interviews with 50 women aged between 18 and 40 years with moderate to severe acne who were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania Health System and from a private dermatology clinic in Cincinnati. They used free listing and open-ended, semistructured interviews to elicit opinions from the women on how acne affected their lives; their experience with acne treatments, dermatologists, and health care systems; as well as their views on treatment success.

The mean age of the participants was 28 years and 48% were white (10% were Black, 8% were Asian, 4% were more than one race, and the rest abstained from answering this question; 10% said they were Hispanic).

More than three-quarters (78%) reported prior treatment with topical retinoids, followed by spironolactone (70%), topical antibiotics (43%), combined oral contraceptives (43%), and isotretinoin (41%). During the free-listing part of interviews, where the women reported the first words that came to their mind when asked about success of treatment and adverse effects, the most important terms expressed related to treatment success were clear skin, no scarring, and no acne. The most important terms related to treatment adverse effects were dryness, redness, and burning.

In the semistructured interview portion of the study, the main themes expressed were acne-related concerns about appearance, including feeling less confident at work; mental and emotional health, including feelings of depression, anxiety, depression, and low self-worth during acne breakouts; and everyday life impact, including the notion that acne affected how other people perceived them. The other main themes included successful treatment, with clear skin and having a manageable number of lesions being desirable outcomes; and interactions with health care, including varied experiences with dermatologists. The researchers observed that most participants did not think oral antibiotics were appropriate treatments for their acne, specifically because of limited long-term effectiveness.

“Many patients described frustration with finding a dermatologist with whom they were comfortable and with identifying effective treatments for their acne,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, those who thought their dermatologist listened to their concerns and individualized their treatment plan reported higher levels of satisfaction.”

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri, who is now with the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he was surprised by how many patients expressed interest in nonantibiotic treatments for acne, “given that oral antibiotics are by far the most commonly prescribed systemic treatment for acne.”

Moreover, he added, “although I have experienced many patients being hesitant about isotretinoin, I was surprised by how strong patients’ concerns were about isotretinoin side effects. Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions about isotretinoin that limit use of this treatment that can be highly effective and safe for the appropriate patient.”

In an accompanying editorial, dermatologists Diane M. Thiboutot, MD and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, with Penn State University, Hershey, and Alison M. Layton, MB, ChB, with the Harrogate Foundation Trust, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, wrote that the findings from the study “resonate with those recently reported in several international studies that examine the impacts of acne, how patients assess treatment success, and what is important to measure from a patient and health care professional perspective in a clinical trial for acne.”

A large systematic review on the impact of acne on patients, conducted by the Acne Core Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), found that “appearance-related concerns and negative psychosocial effects were found to be a major impact of acne,” they noted. “Surprisingly, only 22 of the 473 studies identified in this review included qualitative data gathered from patient interviews. It is encouraging to see the concordance between the concerns voiced by the participants in the current study and those identified from the literature review, wherein a variety of methods were used to assess acne impacts.”

For his part, Dr. Barbieri said that the study findings “justify the importance of having a discussion with patients about their unique lived experience of acne and individualizing treatment to their specific needs. Patient reported outcome measures could be a useful adjunctive tool to capture these impacts on quality of life.”

This study was funded by grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he received partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Thiboutot reported receiving consultant fees from Galderma and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Layton reported receiving unrestricted educational presentation, advisory board, and consultancy fees from Galderma Honoraria; unrestricted educational presentation and advisory board honoraria from Leo; advisory board honoraria from Novartis and Mylan; consultancy honoraria from Procter and Gamble and Meda; grants from Galderma; and consultancy and advisory board honoraria from Origimm outside the submitted work.

results from a qualitative study demonstrated.

“Nearly 50% of women experience acne in their 20s, and 35% experience acne in their 30s,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, formerly of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization. “While several qualitative studies have examined acne in adolescence, the lived experience of adult female acne has not been explored in detail and prior studies have included relatively few patients. As a result, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews among adult women with acne to examine the lived experience of adult acne and its treatment.”

For the study, published online July 28, 2021, in JAMA Dermatology, Dr. Barbieri and colleagues conducted voluntary, confidential phone interviews with 50 women aged between 18 and 40 years with moderate to severe acne who were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania Health System and from a private dermatology clinic in Cincinnati. They used free listing and open-ended, semistructured interviews to elicit opinions from the women on how acne affected their lives; their experience with acne treatments, dermatologists, and health care systems; as well as their views on treatment success.

The mean age of the participants was 28 years and 48% were white (10% were Black, 8% were Asian, 4% were more than one race, and the rest abstained from answering this question; 10% said they were Hispanic).

More than three-quarters (78%) reported prior treatment with topical retinoids, followed by spironolactone (70%), topical antibiotics (43%), combined oral contraceptives (43%), and isotretinoin (41%). During the free-listing part of interviews, where the women reported the first words that came to their mind when asked about success of treatment and adverse effects, the most important terms expressed related to treatment success were clear skin, no scarring, and no acne. The most important terms related to treatment adverse effects were dryness, redness, and burning.

In the semistructured interview portion of the study, the main themes expressed were acne-related concerns about appearance, including feeling less confident at work; mental and emotional health, including feelings of depression, anxiety, depression, and low self-worth during acne breakouts; and everyday life impact, including the notion that acne affected how other people perceived them. The other main themes included successful treatment, with clear skin and having a manageable number of lesions being desirable outcomes; and interactions with health care, including varied experiences with dermatologists. The researchers observed that most participants did not think oral antibiotics were appropriate treatments for their acne, specifically because of limited long-term effectiveness.

“Many patients described frustration with finding a dermatologist with whom they were comfortable and with identifying effective treatments for their acne,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, those who thought their dermatologist listened to their concerns and individualized their treatment plan reported higher levels of satisfaction.”

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri, who is now with the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he was surprised by how many patients expressed interest in nonantibiotic treatments for acne, “given that oral antibiotics are by far the most commonly prescribed systemic treatment for acne.”

Moreover, he added, “although I have experienced many patients being hesitant about isotretinoin, I was surprised by how strong patients’ concerns were about isotretinoin side effects. Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions about isotretinoin that limit use of this treatment that can be highly effective and safe for the appropriate patient.”

In an accompanying editorial, dermatologists Diane M. Thiboutot, MD and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, with Penn State University, Hershey, and Alison M. Layton, MB, ChB, with the Harrogate Foundation Trust, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, wrote that the findings from the study “resonate with those recently reported in several international studies that examine the impacts of acne, how patients assess treatment success, and what is important to measure from a patient and health care professional perspective in a clinical trial for acne.”

A large systematic review on the impact of acne on patients, conducted by the Acne Core Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), found that “appearance-related concerns and negative psychosocial effects were found to be a major impact of acne,” they noted. “Surprisingly, only 22 of the 473 studies identified in this review included qualitative data gathered from patient interviews. It is encouraging to see the concordance between the concerns voiced by the participants in the current study and those identified from the literature review, wherein a variety of methods were used to assess acne impacts.”

For his part, Dr. Barbieri said that the study findings “justify the importance of having a discussion with patients about their unique lived experience of acne and individualizing treatment to their specific needs. Patient reported outcome measures could be a useful adjunctive tool to capture these impacts on quality of life.”

This study was funded by grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he received partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Thiboutot reported receiving consultant fees from Galderma and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Layton reported receiving unrestricted educational presentation, advisory board, and consultancy fees from Galderma Honoraria; unrestricted educational presentation and advisory board honoraria from Leo; advisory board honoraria from Novartis and Mylan; consultancy honoraria from Procter and Gamble and Meda; grants from Galderma; and consultancy and advisory board honoraria from Origimm outside the submitted work.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

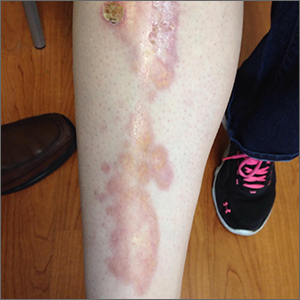

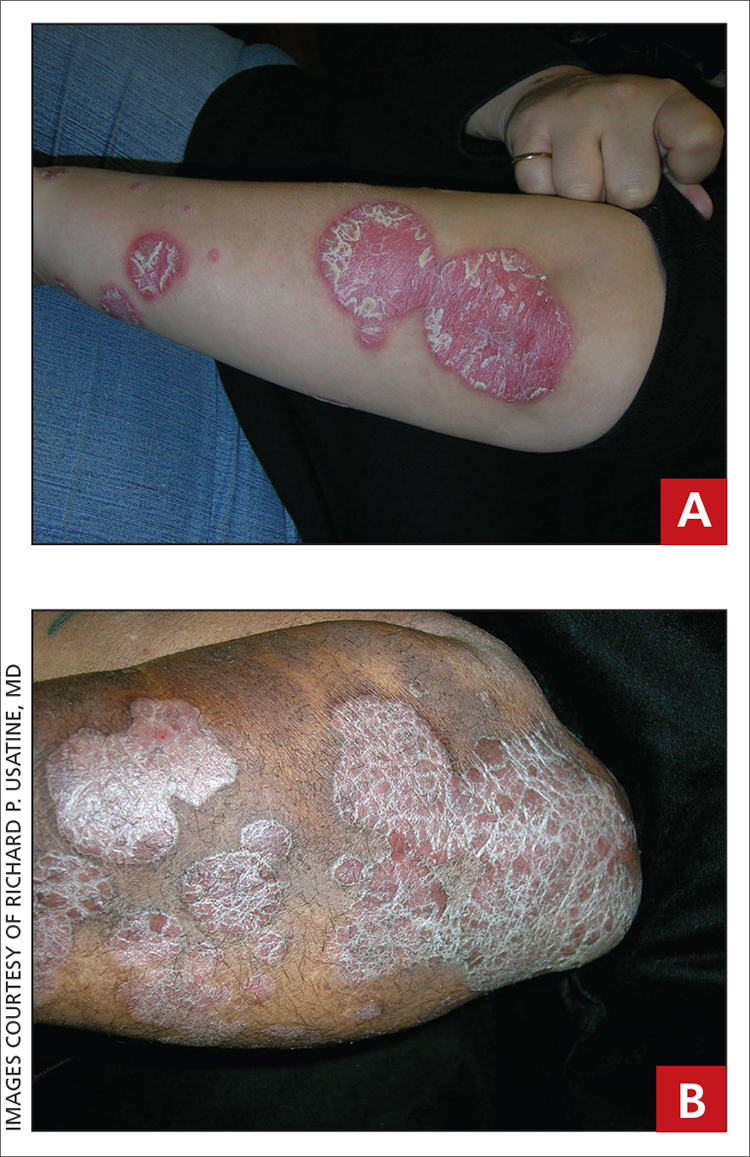

Leg rash

The appearance and location of this rash are classic signs for necrobiosis lipoidica, a chronic granulomatous skin disease commonly associated with diabetes. The patient’s initial hemoglobin A1c was 12.4%, confirming a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, and a punch biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a broad zone of necrobiosis in the mid to lower dermis and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate, including plasma cells.

Necrobiosis lipoidica is rare, typically affects middle-aged adults, and is more common in women than in men.1 Although commonly associated with diabetes (hence the historical name necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum), a significant number of cases occur in patients without diabetes.2 The pathogenesis is not fully understood. The condition first appears as asymptomatic yellow to red-brown papules and plaques, most commonly on the anterior legs. The lesions then flatten over time, forming broad, yellow-pink patches and plaques.1,2

Generally, the diagnosis can be made clinically but, if uncertain, a punch biopsy is the preferred technique for confirmation. The differential diagnosis includes chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE), sarcoidosis, and dermatophytosis. Although the appearance of lesions associated with LE or sarcoidosis can vary, neither one manifests with the yellow coloring seen here. Dermatophytosis typically demonstrates scale and pruritus with an active border; viewing a potassium hydroxide preparation of a skin scraping is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis.

Treatment for necrobiosis lipoidica includes counseling patients to avoid trauma to the affected areas, high-potency topical corticosteroids, and photodynamic therapy.3 Often, lesions are permanent.

For this patient’s diabetes treatment, she was prescribed metformin and insulin glargine and counseled extensively on weight loss, regular exercise, and appropriate diet adjustments. The rash was treated topically with triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. At her 4-month follow-up, the patient’s hemoglobin A1c value had dropped to 5.4%, and the rash had become less prominent and widespread. The patient was pleased with the cosmetic outcome and declined referral to a dermatologist for further treatment.

Photo and text courtesy of Samuel Dickmann, MD, and James Medley, MD, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville.

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. O’Toole EA, Kennedy U, Nolan JJ, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica: only a minority of patients have diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:283-286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02663.x

3. Heidenheim M, Jemec GBE. Successful treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1548-1550. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.12.1548

The appearance and location of this rash are classic signs for necrobiosis lipoidica, a chronic granulomatous skin disease commonly associated with diabetes. The patient’s initial hemoglobin A1c was 12.4%, confirming a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, and a punch biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a broad zone of necrobiosis in the mid to lower dermis and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate, including plasma cells.

Necrobiosis lipoidica is rare, typically affects middle-aged adults, and is more common in women than in men.1 Although commonly associated with diabetes (hence the historical name necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum), a significant number of cases occur in patients without diabetes.2 The pathogenesis is not fully understood. The condition first appears as asymptomatic yellow to red-brown papules and plaques, most commonly on the anterior legs. The lesions then flatten over time, forming broad, yellow-pink patches and plaques.1,2

Generally, the diagnosis can be made clinically but, if uncertain, a punch biopsy is the preferred technique for confirmation. The differential diagnosis includes chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE), sarcoidosis, and dermatophytosis. Although the appearance of lesions associated with LE or sarcoidosis can vary, neither one manifests with the yellow coloring seen here. Dermatophytosis typically demonstrates scale and pruritus with an active border; viewing a potassium hydroxide preparation of a skin scraping is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis.

Treatment for necrobiosis lipoidica includes counseling patients to avoid trauma to the affected areas, high-potency topical corticosteroids, and photodynamic therapy.3 Often, lesions are permanent.

For this patient’s diabetes treatment, she was prescribed metformin and insulin glargine and counseled extensively on weight loss, regular exercise, and appropriate diet adjustments. The rash was treated topically with triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. At her 4-month follow-up, the patient’s hemoglobin A1c value had dropped to 5.4%, and the rash had become less prominent and widespread. The patient was pleased with the cosmetic outcome and declined referral to a dermatologist for further treatment.

Photo and text courtesy of Samuel Dickmann, MD, and James Medley, MD, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville.

The appearance and location of this rash are classic signs for necrobiosis lipoidica, a chronic granulomatous skin disease commonly associated with diabetes. The patient’s initial hemoglobin A1c was 12.4%, confirming a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, and a punch biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a broad zone of necrobiosis in the mid to lower dermis and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate, including plasma cells.

Necrobiosis lipoidica is rare, typically affects middle-aged adults, and is more common in women than in men.1 Although commonly associated with diabetes (hence the historical name necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum), a significant number of cases occur in patients without diabetes.2 The pathogenesis is not fully understood. The condition first appears as asymptomatic yellow to red-brown papules and plaques, most commonly on the anterior legs. The lesions then flatten over time, forming broad, yellow-pink patches and plaques.1,2

Generally, the diagnosis can be made clinically but, if uncertain, a punch biopsy is the preferred technique for confirmation. The differential diagnosis includes chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE), sarcoidosis, and dermatophytosis. Although the appearance of lesions associated with LE or sarcoidosis can vary, neither one manifests with the yellow coloring seen here. Dermatophytosis typically demonstrates scale and pruritus with an active border; viewing a potassium hydroxide preparation of a skin scraping is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis.

Treatment for necrobiosis lipoidica includes counseling patients to avoid trauma to the affected areas, high-potency topical corticosteroids, and photodynamic therapy.3 Often, lesions are permanent.

For this patient’s diabetes treatment, she was prescribed metformin and insulin glargine and counseled extensively on weight loss, regular exercise, and appropriate diet adjustments. The rash was treated topically with triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. At her 4-month follow-up, the patient’s hemoglobin A1c value had dropped to 5.4%, and the rash had become less prominent and widespread. The patient was pleased with the cosmetic outcome and declined referral to a dermatologist for further treatment.

Photo and text courtesy of Samuel Dickmann, MD, and James Medley, MD, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville.

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. O’Toole EA, Kennedy U, Nolan JJ, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica: only a minority of patients have diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:283-286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02663.x

3. Heidenheim M, Jemec GBE. Successful treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1548-1550. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.12.1548

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. O’Toole EA, Kennedy U, Nolan JJ, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica: only a minority of patients have diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:283-286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02663.x

3. Heidenheim M, Jemec GBE. Successful treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1548-1550. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.12.1548

When is MRI useful in the management of congenital melanocytic nevi?

When used for appropriate patients, results from a small multi-institutional study showed.

“The majority of congenital nevi are considered low risk for cutaneous and/or systemic complications,” Holly Neale said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “However, a subset of children born with higher-risk congenital nevi require close monitoring, as some features of congenital nevi have been associated with cutaneous melanoma, central nervous system melanoma, melanin in the brain or spine, and structural irregularities in the brain or spine. It’s important to understand which congenital nevi are considered higher risk in order to guide management and counseling decisions.”

One major management decision is to do a screening magnetic resonance image of the CNS to evaluate for neurologic involvement, said Ms. Neale, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Prior studies have shown that congenital nevi that are bigger than 20 cm, posterior axial location, and having more than one congenital nevus may predict CNS abnormalities, while recent guidelines from experts in the field suggest that any child with more than one congenital nevus at birth undergo screening MRI.

“However, guidelines are evolving, and more data is required to better understand the CNS abnormalities and patient outcomes for children with congenital nevi,” said Ms. Neale, who spent the past year as a pediatric dermatology research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

To address this knowledge gap, she and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Boston Children’s Hospital performed a retrospective chart review between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2019, of individuals ages 18 and younger who had an MRI of the brain or spine with at least one dermatologist-diagnosed nevus as identified via key words in the medical record. Of the 909 patients screened, 46 met inclusion criteria, evenly split between males and females.

The most common location of the largest nevus was the trunk (in 41% of patients), followed by lesions that spanned multiple regions. More than one-third of patients had giant nevi (greater than 40 cm).

“The majority of images were considered nonconcerning, which includes normal, benign, or other findings such as trauma related, infectious, or orthopedic, which we did not classify as abnormal as it did not guide our study question,” Ms. Neale said. Specifically, 8% of spine images and 27% of brain images were considered “concerning,” defined as any finding that prompted further workup or monitoring, which includes findings concerning for melanin.

The most common brain finding was melanin (in eight children), and one child with brain melanin also had findings suggestive of melanin in the thoracic spine. The most common finding in spine MRIs was fatty filum (in four children), requiring intervention for tethering in only one individual. No cases of cutaneous melanoma developed during the study period, and only one patient with abnormal imaging had CNS melanoma, which was fatal.

All patients with findings suggestive of CNS melanin had more than four nevi present at birth, which is in line with current imaging screening guidelines. In addition, children with concerning imaging had higher rates of death, neurodevelopmental problems, seizures, and neurosurgery, compared with their counterparts with unremarkable imaging findings. Describing preliminary analyses, Ms. Neale said that a chi square analysis was performed to test statistical significance of these differences, “and neurosurgery was the only variable that children with concerning imaging were significantly more likely to experience, although sample size limits detection for the other variables.”

The authors concluded that MRI is a helpful tool when used in the appropriate clinical context for the management of congenital nevi. “As more children undergo imaging, we may discover more nonmelanin abnormalities,” she said.

Joseph M. Lam, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the increased risk of CNS melanin in patients with larger lesions and in those with multiple lesions confirms previous reports.

“It is interesting to note that some patients with nonconcerning imaging results still had neurodevelopmental problems and seizures, albeit at a lower rate than those with concerning imaging results,” said Dr. Lam, a pediatric dermatologist at British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver. “The lack of a control group for comparison of rates of neurological sequelae, such as NDP, seizures and nonmelanin structural anomalies, limits the generalizability of the findings. However, this is a nice study that helps us understand better the CNS anomalies in CMN.”

Ms. Neale acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the lack of a control group without CMN, the small number of patients, the potential for referral bias, and its retrospective design. Also, the proximity of the study period does not allow for chronic follow-up and detection of the development of melanoma or other problems in the future.

Ms. Neale and associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lam disclosed that he has received speaker fees from Pierre Fabre.

When used for appropriate patients, results from a small multi-institutional study showed.

“The majority of congenital nevi are considered low risk for cutaneous and/or systemic complications,” Holly Neale said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “However, a subset of children born with higher-risk congenital nevi require close monitoring, as some features of congenital nevi have been associated with cutaneous melanoma, central nervous system melanoma, melanin in the brain or spine, and structural irregularities in the brain or spine. It’s important to understand which congenital nevi are considered higher risk in order to guide management and counseling decisions.”

One major management decision is to do a screening magnetic resonance image of the CNS to evaluate for neurologic involvement, said Ms. Neale, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Prior studies have shown that congenital nevi that are bigger than 20 cm, posterior axial location, and having more than one congenital nevus may predict CNS abnormalities, while recent guidelines from experts in the field suggest that any child with more than one congenital nevus at birth undergo screening MRI.

“However, guidelines are evolving, and more data is required to better understand the CNS abnormalities and patient outcomes for children with congenital nevi,” said Ms. Neale, who spent the past year as a pediatric dermatology research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

To address this knowledge gap, she and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Boston Children’s Hospital performed a retrospective chart review between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2019, of individuals ages 18 and younger who had an MRI of the brain or spine with at least one dermatologist-diagnosed nevus as identified via key words in the medical record. Of the 909 patients screened, 46 met inclusion criteria, evenly split between males and females.

The most common location of the largest nevus was the trunk (in 41% of patients), followed by lesions that spanned multiple regions. More than one-third of patients had giant nevi (greater than 40 cm).

“The majority of images were considered nonconcerning, which includes normal, benign, or other findings such as trauma related, infectious, or orthopedic, which we did not classify as abnormal as it did not guide our study question,” Ms. Neale said. Specifically, 8% of spine images and 27% of brain images were considered “concerning,” defined as any finding that prompted further workup or monitoring, which includes findings concerning for melanin.

The most common brain finding was melanin (in eight children), and one child with brain melanin also had findings suggestive of melanin in the thoracic spine. The most common finding in spine MRIs was fatty filum (in four children), requiring intervention for tethering in only one individual. No cases of cutaneous melanoma developed during the study period, and only one patient with abnormal imaging had CNS melanoma, which was fatal.

All patients with findings suggestive of CNS melanin had more than four nevi present at birth, which is in line with current imaging screening guidelines. In addition, children with concerning imaging had higher rates of death, neurodevelopmental problems, seizures, and neurosurgery, compared with their counterparts with unremarkable imaging findings. Describing preliminary analyses, Ms. Neale said that a chi square analysis was performed to test statistical significance of these differences, “and neurosurgery was the only variable that children with concerning imaging were significantly more likely to experience, although sample size limits detection for the other variables.”

The authors concluded that MRI is a helpful tool when used in the appropriate clinical context for the management of congenital nevi. “As more children undergo imaging, we may discover more nonmelanin abnormalities,” she said.

Joseph M. Lam, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the increased risk of CNS melanin in patients with larger lesions and in those with multiple lesions confirms previous reports.

“It is interesting to note that some patients with nonconcerning imaging results still had neurodevelopmental problems and seizures, albeit at a lower rate than those with concerning imaging results,” said Dr. Lam, a pediatric dermatologist at British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver. “The lack of a control group for comparison of rates of neurological sequelae, such as NDP, seizures and nonmelanin structural anomalies, limits the generalizability of the findings. However, this is a nice study that helps us understand better the CNS anomalies in CMN.”

Ms. Neale acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the lack of a control group without CMN, the small number of patients, the potential for referral bias, and its retrospective design. Also, the proximity of the study period does not allow for chronic follow-up and detection of the development of melanoma or other problems in the future.

Ms. Neale and associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lam disclosed that he has received speaker fees from Pierre Fabre.

When used for appropriate patients, results from a small multi-institutional study showed.

“The majority of congenital nevi are considered low risk for cutaneous and/or systemic complications,” Holly Neale said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “However, a subset of children born with higher-risk congenital nevi require close monitoring, as some features of congenital nevi have been associated with cutaneous melanoma, central nervous system melanoma, melanin in the brain or spine, and structural irregularities in the brain or spine. It’s important to understand which congenital nevi are considered higher risk in order to guide management and counseling decisions.”

One major management decision is to do a screening magnetic resonance image of the CNS to evaluate for neurologic involvement, said Ms. Neale, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Prior studies have shown that congenital nevi that are bigger than 20 cm, posterior axial location, and having more than one congenital nevus may predict CNS abnormalities, while recent guidelines from experts in the field suggest that any child with more than one congenital nevus at birth undergo screening MRI.

“However, guidelines are evolving, and more data is required to better understand the CNS abnormalities and patient outcomes for children with congenital nevi,” said Ms. Neale, who spent the past year as a pediatric dermatology research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

To address this knowledge gap, she and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Boston Children’s Hospital performed a retrospective chart review between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2019, of individuals ages 18 and younger who had an MRI of the brain or spine with at least one dermatologist-diagnosed nevus as identified via key words in the medical record. Of the 909 patients screened, 46 met inclusion criteria, evenly split between males and females.

The most common location of the largest nevus was the trunk (in 41% of patients), followed by lesions that spanned multiple regions. More than one-third of patients had giant nevi (greater than 40 cm).

“The majority of images were considered nonconcerning, which includes normal, benign, or other findings such as trauma related, infectious, or orthopedic, which we did not classify as abnormal as it did not guide our study question,” Ms. Neale said. Specifically, 8% of spine images and 27% of brain images were considered “concerning,” defined as any finding that prompted further workup or monitoring, which includes findings concerning for melanin.

The most common brain finding was melanin (in eight children), and one child with brain melanin also had findings suggestive of melanin in the thoracic spine. The most common finding in spine MRIs was fatty filum (in four children), requiring intervention for tethering in only one individual. No cases of cutaneous melanoma developed during the study period, and only one patient with abnormal imaging had CNS melanoma, which was fatal.

All patients with findings suggestive of CNS melanin had more than four nevi present at birth, which is in line with current imaging screening guidelines. In addition, children with concerning imaging had higher rates of death, neurodevelopmental problems, seizures, and neurosurgery, compared with their counterparts with unremarkable imaging findings. Describing preliminary analyses, Ms. Neale said that a chi square analysis was performed to test statistical significance of these differences, “and neurosurgery was the only variable that children with concerning imaging were significantly more likely to experience, although sample size limits detection for the other variables.”

The authors concluded that MRI is a helpful tool when used in the appropriate clinical context for the management of congenital nevi. “As more children undergo imaging, we may discover more nonmelanin abnormalities,” she said.

Joseph M. Lam, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the increased risk of CNS melanin in patients with larger lesions and in those with multiple lesions confirms previous reports.

“It is interesting to note that some patients with nonconcerning imaging results still had neurodevelopmental problems and seizures, albeit at a lower rate than those with concerning imaging results,” said Dr. Lam, a pediatric dermatologist at British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver. “The lack of a control group for comparison of rates of neurological sequelae, such as NDP, seizures and nonmelanin structural anomalies, limits the generalizability of the findings. However, this is a nice study that helps us understand better the CNS anomalies in CMN.”

Ms. Neale acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the lack of a control group without CMN, the small number of patients, the potential for referral bias, and its retrospective design. Also, the proximity of the study period does not allow for chronic follow-up and detection of the development of melanoma or other problems in the future.

Ms. Neale and associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lam disclosed that he has received speaker fees from Pierre Fabre.

FROM SPD 2021

Study estimates carbon footprint reduction of virtual isotretinoin visits

: A reduction of 5,137 kg of greenhouse gas emissions in carbon dioxide equivalents.

In what they say is “one of the first studies to evaluate the environmental impact of any aspect of dermatology,” the authors of the retrospective cross-sectional study identified patients who had virtual visits for isotretinoin management between March 25 and May 29, 2020, – the period during which all such visits were conducted virtually in keeping with hospital recommendations to minimize the spread of COVID-19.

The investigators, from the department of dermatology and the department of civil and environmental engineering at West Virginia University, Morgantown, then counted the number of virtual visits that occurred during this period and through Dec. 1, 2020, (175 virtual visits), calculated the distance patients would have traveled round-trip had these visits been in-person, and converted miles saved into the environmental impact using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Federal Highway Administration data and relevant EPA standards.

Most patients had elected to continue virtual visits after May 29, the point at which patients were given the option to return to the WVUH clinic. (Patients who initiated treatment during the 2-month identification period were not included.)

The investigators determined that virtual management of isotretinoin saved a median of 37.8 miles per visit during the study period of March 25 to Dec. 1, and estimated that the virtual visits reduced total travel by 14,450 miles. For the analysis, patients were assumed to use light-duty vehicles.

In addition to calculating the reduction in emissions during the study period (5,137 kg of CO2equivalents) they used patient census data from 2019 to 2020 and data from the study period to project the mileage – and the associated emissions – that would be saved annually if all in-person visits for isotretinoin management occurred virtually.

Their calculation for a projected emissions reduction with 1 year of all-virtual isotretinoin management was 49,400 kg of greenhouse gas emissions in CO2equivalents. This is the emission load released when 24,690 kg of coal are burned or 6.3 million smartphones are charged, the researchers wrote.

“Considering that more than 1,000,000 prescriptions of isotretinoin are authorized annually in the United States, the environmental impact could be magnified if virtual delivery of isotretinoin care is adopted on a national scale,” they commented.“Given the serious consequences of global climate change, analysis of the environmental impact of all fields of medicine, including dermatology, is warranted,” they added.

The reduced greenhouse gas emissions are “definitely [being taken] into consideration for future decisions about virtual visits” in the department of dermatology, said Zachary Zinn, MD, residency director and associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, who is the senior author of the study. “The main benefit of virtual care in my opinion,” he said in an interview, “is the potential to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Justin Lee, MD, an intern at WVU and the study’s first author, said that the research team was motivated to think about how they “could reduce the negative environmental impact of practicing dermatology” after they read a paper about the environmental impact of endoscopy, written by a gastroenterologist.

In the study, no pregnancies occurred and monthly tests were performed, but “formal assessment of pregnancy risk with virtual isotretinoin management would be warranted,” Dr. Lee and coauthors wrote, noting too that, while no differences were seen with respect to isotretinoin side effects, these were not formally analyzed.

Dr. Zinn said that he and colleagues at WVUH are currently conducting clinical trials to assess the quality and efficacy of virtual care for patients with acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. Delivering care virtually “will be easier to do if there are data supporting [its] quality and efficacy,” he said. Rosacea is another condition that may be amendable to virtual care, he noted.

Meanwhile, he said, isotretinoin management is “well suited” for virtual visits. When initiating isotretinoin treatment, Dr. Zinn now “proactively inquires” if patients would like to pursue their follow-up visits virtually. “I’ll note that it will save the time and decrease the burden of travel, including the financial cost as well as the environmental cost of travel,” he said, estimating that about half of their management visits are currently virtual.

Asked about the study, Misha Rosenbach, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the reduced carbon footprint calculated by the researchers and its downstream health benefits “should be taken into consideration by [dermatology] departments, insurers and policymakers” when making decisions about teledermatology.

While environmental impact is “not something I think most institutions are considering for virtual versus in-person care, they should be. And some are,” said Dr. Rosenbach, a founder and cochair of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues.

Limitations of the study include the generalizability of the results. The impact of virtual isotretinoin management “may be less in predominantly urban areas” than it is in predominately rural West Virginia, the study authors note. And in the case of West Virginia, travel to a local laboratory and pharmacy offsets some of the environmental benefits for the virtual care, they noted. Such travel wasn’t accounted for in the study, but it was found to be a fraction of travel to the WVU hospital clinic. (Patients traveled a median of 5.8 miles to a lab 2.4 times from March 25 to Dec. 1, 2020.)

Dr. Lee will start his dermatology residency at WVU next year. The study was funded by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest, according to Dr. Lee.

: A reduction of 5,137 kg of greenhouse gas emissions in carbon dioxide equivalents.

In what they say is “one of the first studies to evaluate the environmental impact of any aspect of dermatology,” the authors of the retrospective cross-sectional study identified patients who had virtual visits for isotretinoin management between March 25 and May 29, 2020, – the period during which all such visits were conducted virtually in keeping with hospital recommendations to minimize the spread of COVID-19.

The investigators, from the department of dermatology and the department of civil and environmental engineering at West Virginia University, Morgantown, then counted the number of virtual visits that occurred during this period and through Dec. 1, 2020, (175 virtual visits), calculated the distance patients would have traveled round-trip had these visits been in-person, and converted miles saved into the environmental impact using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Federal Highway Administration data and relevant EPA standards.

Most patients had elected to continue virtual visits after May 29, the point at which patients were given the option to return to the WVUH clinic. (Patients who initiated treatment during the 2-month identification period were not included.)

The investigators determined that virtual management of isotretinoin saved a median of 37.8 miles per visit during the study period of March 25 to Dec. 1, and estimated that the virtual visits reduced total travel by 14,450 miles. For the analysis, patients were assumed to use light-duty vehicles.

In addition to calculating the reduction in emissions during the study period (5,137 kg of CO2equivalents) they used patient census data from 2019 to 2020 and data from the study period to project the mileage – and the associated emissions – that would be saved annually if all in-person visits for isotretinoin management occurred virtually.

Their calculation for a projected emissions reduction with 1 year of all-virtual isotretinoin management was 49,400 kg of greenhouse gas emissions in CO2equivalents. This is the emission load released when 24,690 kg of coal are burned or 6.3 million smartphones are charged, the researchers wrote.

“Considering that more than 1,000,000 prescriptions of isotretinoin are authorized annually in the United States, the environmental impact could be magnified if virtual delivery of isotretinoin care is adopted on a national scale,” they commented.“Given the serious consequences of global climate change, analysis of the environmental impact of all fields of medicine, including dermatology, is warranted,” they added.

The reduced greenhouse gas emissions are “definitely [being taken] into consideration for future decisions about virtual visits” in the department of dermatology, said Zachary Zinn, MD, residency director and associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, who is the senior author of the study. “The main benefit of virtual care in my opinion,” he said in an interview, “is the potential to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Justin Lee, MD, an intern at WVU and the study’s first author, said that the research team was motivated to think about how they “could reduce the negative environmental impact of practicing dermatology” after they read a paper about the environmental impact of endoscopy, written by a gastroenterologist.

In the study, no pregnancies occurred and monthly tests were performed, but “formal assessment of pregnancy risk with virtual isotretinoin management would be warranted,” Dr. Lee and coauthors wrote, noting too that, while no differences were seen with respect to isotretinoin side effects, these were not formally analyzed.

Dr. Zinn said that he and colleagues at WVUH are currently conducting clinical trials to assess the quality and efficacy of virtual care for patients with acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. Delivering care virtually “will be easier to do if there are data supporting [its] quality and efficacy,” he said. Rosacea is another condition that may be amendable to virtual care, he noted.

Meanwhile, he said, isotretinoin management is “well suited” for virtual visits. When initiating isotretinoin treatment, Dr. Zinn now “proactively inquires” if patients would like to pursue their follow-up visits virtually. “I’ll note that it will save the time and decrease the burden of travel, including the financial cost as well as the environmental cost of travel,” he said, estimating that about half of their management visits are currently virtual.

Asked about the study, Misha Rosenbach, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the reduced carbon footprint calculated by the researchers and its downstream health benefits “should be taken into consideration by [dermatology] departments, insurers and policymakers” when making decisions about teledermatology.

While environmental impact is “not something I think most institutions are considering for virtual versus in-person care, they should be. And some are,” said Dr. Rosenbach, a founder and cochair of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues.

Limitations of the study include the generalizability of the results. The impact of virtual isotretinoin management “may be less in predominantly urban areas” than it is in predominately rural West Virginia, the study authors note. And in the case of West Virginia, travel to a local laboratory and pharmacy offsets some of the environmental benefits for the virtual care, they noted. Such travel wasn’t accounted for in the study, but it was found to be a fraction of travel to the WVU hospital clinic. (Patients traveled a median of 5.8 miles to a lab 2.4 times from March 25 to Dec. 1, 2020.)

Dr. Lee will start his dermatology residency at WVU next year. The study was funded by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest, according to Dr. Lee.

: A reduction of 5,137 kg of greenhouse gas emissions in carbon dioxide equivalents.

In what they say is “one of the first studies to evaluate the environmental impact of any aspect of dermatology,” the authors of the retrospective cross-sectional study identified patients who had virtual visits for isotretinoin management between March 25 and May 29, 2020, – the period during which all such visits were conducted virtually in keeping with hospital recommendations to minimize the spread of COVID-19.

The investigators, from the department of dermatology and the department of civil and environmental engineering at West Virginia University, Morgantown, then counted the number of virtual visits that occurred during this period and through Dec. 1, 2020, (175 virtual visits), calculated the distance patients would have traveled round-trip had these visits been in-person, and converted miles saved into the environmental impact using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Federal Highway Administration data and relevant EPA standards.

Most patients had elected to continue virtual visits after May 29, the point at which patients were given the option to return to the WVUH clinic. (Patients who initiated treatment during the 2-month identification period were not included.)

The investigators determined that virtual management of isotretinoin saved a median of 37.8 miles per visit during the study period of March 25 to Dec. 1, and estimated that the virtual visits reduced total travel by 14,450 miles. For the analysis, patients were assumed to use light-duty vehicles.

In addition to calculating the reduction in emissions during the study period (5,137 kg of CO2equivalents) they used patient census data from 2019 to 2020 and data from the study period to project the mileage – and the associated emissions – that would be saved annually if all in-person visits for isotretinoin management occurred virtually.

Their calculation for a projected emissions reduction with 1 year of all-virtual isotretinoin management was 49,400 kg of greenhouse gas emissions in CO2equivalents. This is the emission load released when 24,690 kg of coal are burned or 6.3 million smartphones are charged, the researchers wrote.

“Considering that more than 1,000,000 prescriptions of isotretinoin are authorized annually in the United States, the environmental impact could be magnified if virtual delivery of isotretinoin care is adopted on a national scale,” they commented.“Given the serious consequences of global climate change, analysis of the environmental impact of all fields of medicine, including dermatology, is warranted,” they added.

The reduced greenhouse gas emissions are “definitely [being taken] into consideration for future decisions about virtual visits” in the department of dermatology, said Zachary Zinn, MD, residency director and associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, who is the senior author of the study. “The main benefit of virtual care in my opinion,” he said in an interview, “is the potential to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Justin Lee, MD, an intern at WVU and the study’s first author, said that the research team was motivated to think about how they “could reduce the negative environmental impact of practicing dermatology” after they read a paper about the environmental impact of endoscopy, written by a gastroenterologist.

In the study, no pregnancies occurred and monthly tests were performed, but “formal assessment of pregnancy risk with virtual isotretinoin management would be warranted,” Dr. Lee and coauthors wrote, noting too that, while no differences were seen with respect to isotretinoin side effects, these were not formally analyzed.

Dr. Zinn said that he and colleagues at WVUH are currently conducting clinical trials to assess the quality and efficacy of virtual care for patients with acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. Delivering care virtually “will be easier to do if there are data supporting [its] quality and efficacy,” he said. Rosacea is another condition that may be amendable to virtual care, he noted.

Meanwhile, he said, isotretinoin management is “well suited” for virtual visits. When initiating isotretinoin treatment, Dr. Zinn now “proactively inquires” if patients would like to pursue their follow-up visits virtually. “I’ll note that it will save the time and decrease the burden of travel, including the financial cost as well as the environmental cost of travel,” he said, estimating that about half of their management visits are currently virtual.

Asked about the study, Misha Rosenbach, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the reduced carbon footprint calculated by the researchers and its downstream health benefits “should be taken into consideration by [dermatology] departments, insurers and policymakers” when making decisions about teledermatology.

While environmental impact is “not something I think most institutions are considering for virtual versus in-person care, they should be. And some are,” said Dr. Rosenbach, a founder and cochair of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues.

Limitations of the study include the generalizability of the results. The impact of virtual isotretinoin management “may be less in predominantly urban areas” than it is in predominately rural West Virginia, the study authors note. And in the case of West Virginia, travel to a local laboratory and pharmacy offsets some of the environmental benefits for the virtual care, they noted. Such travel wasn’t accounted for in the study, but it was found to be a fraction of travel to the WVU hospital clinic. (Patients traveled a median of 5.8 miles to a lab 2.4 times from March 25 to Dec. 1, 2020.)

Dr. Lee will start his dermatology residency at WVU next year. The study was funded by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest, according to Dr. Lee.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Common outcome measures for AD lack adequate reporting of race, skin tone

, according to results from a systematic review.

“AD is associated with considerable heterogeneity across different races and skin tones,” presenting study author Trisha Kaundinya said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “Compared with lighter skin tones, darker skin tones more commonly have diffuse xerosis, Dennis-Morgan lines, hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis. This heterogeneity can be challenging to assess in clinical trials and in practice.”

The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) group has selected several scales by international consensus. For clinical trials, the group recommends the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). In clinical practice, the HOME group recommends the POEM, Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-itch measures. “The psychometric validity and reliability of these outcome measures have undergone robust investigation before, but the validity and reliability of these outcome measures remains uncertain across different races, ethnicities, and skin tones,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, in collaboration with Andrew F. Alexis, MD, MPH, vice-chair for diversity and inclusion for the department of dermatology at Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York, and Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sought to examine reporting of race, ethnicity, and skin tone, and to compare results across these groups from studies of psychometric properties for outcome measures in AD. Under the mentorship of Dr. Silverberg, Ms. Kaundinya, a medical student at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her research associates conducted a systematic review that searched PubMed and Embase and identified 165 relevant published studies of 41,146 individuals.

Of the individuals participating in these 165 studies, 73% had an unspecified racial background, 18% were White, 4% were Asian, 2% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 1% were multiracial/other, and the remainder were American Indian/Alaskan Native. Only 55 of the studies (33%) reported the distribution of race or ethnicity, 5 (3%) reported the distribution of skin tone, and 16 (10%) reported psychometric differences in patients with different races, ethnicities, or skin tones. In addition, only 5 of 113 (4%) studies that did not report race, ethnicity, or skin tone–based differences acknowledged absence of stratification as a limitation.

Of note, significant differential item functioning was found between race subgroups for one or more items of the PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Itch Questionnaire (PIQ) Short Forms, POEM, DLQI, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Itchy Quality of Life (ItchyQOL) scale, 5-dimensions (5D) itch scale, Short Form (SF)-12, and NRS-itch. “Correlations of the POEM with the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) differed the most between skin of color and lighter skin,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

“The POEM did seem to correlate similarly with the DLQI and the EASI in both white and nonwhite participants, which may indicate why this trifecta of instruments is recommended by the HOME group. One study found that substituting the erythema component of the EASI scale with greyness for darker skin, in which erythema is more challenging to assess, did not significantly improve the reliability of EASI. This indicates that further research is needed to investigate how EASI can be modified to perform better in darker skin tones.”

She pointed out that some studies of clinician-reported outcome measures were underpowered to detect meaningful differences between patient subgroups. “There were also insufficient data to perform meta-regression of differences between patient subgroups,” she said. “Overall, future studies are needed to determine whether outcome measures recommended by the HOME and other tools perform equally well across diverse patient populations. This systematic review indicates significant reporting and knowledge gaps for psychometric properties of outcome measures by race, ethnicity, or skin tone in AD.”

Ms. Kaundinya reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg, the study’s senior author, is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

, according to results from a systematic review.

“AD is associated with considerable heterogeneity across different races and skin tones,” presenting study author Trisha Kaundinya said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “Compared with lighter skin tones, darker skin tones more commonly have diffuse xerosis, Dennis-Morgan lines, hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis. This heterogeneity can be challenging to assess in clinical trials and in practice.”

The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) group has selected several scales by international consensus. For clinical trials, the group recommends the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). In clinical practice, the HOME group recommends the POEM, Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-itch measures. “The psychometric validity and reliability of these outcome measures have undergone robust investigation before, but the validity and reliability of these outcome measures remains uncertain across different races, ethnicities, and skin tones,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, in collaboration with Andrew F. Alexis, MD, MPH, vice-chair for diversity and inclusion for the department of dermatology at Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York, and Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sought to examine reporting of race, ethnicity, and skin tone, and to compare results across these groups from studies of psychometric properties for outcome measures in AD. Under the mentorship of Dr. Silverberg, Ms. Kaundinya, a medical student at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her research associates conducted a systematic review that searched PubMed and Embase and identified 165 relevant published studies of 41,146 individuals.

Of the individuals participating in these 165 studies, 73% had an unspecified racial background, 18% were White, 4% were Asian, 2% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 1% were multiracial/other, and the remainder were American Indian/Alaskan Native. Only 55 of the studies (33%) reported the distribution of race or ethnicity, 5 (3%) reported the distribution of skin tone, and 16 (10%) reported psychometric differences in patients with different races, ethnicities, or skin tones. In addition, only 5 of 113 (4%) studies that did not report race, ethnicity, or skin tone–based differences acknowledged absence of stratification as a limitation.

Of note, significant differential item functioning was found between race subgroups for one or more items of the PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Itch Questionnaire (PIQ) Short Forms, POEM, DLQI, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Itchy Quality of Life (ItchyQOL) scale, 5-dimensions (5D) itch scale, Short Form (SF)-12, and NRS-itch. “Correlations of the POEM with the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) differed the most between skin of color and lighter skin,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

“The POEM did seem to correlate similarly with the DLQI and the EASI in both white and nonwhite participants, which may indicate why this trifecta of instruments is recommended by the HOME group. One study found that substituting the erythema component of the EASI scale with greyness for darker skin, in which erythema is more challenging to assess, did not significantly improve the reliability of EASI. This indicates that further research is needed to investigate how EASI can be modified to perform better in darker skin tones.”

She pointed out that some studies of clinician-reported outcome measures were underpowered to detect meaningful differences between patient subgroups. “There were also insufficient data to perform meta-regression of differences between patient subgroups,” she said. “Overall, future studies are needed to determine whether outcome measures recommended by the HOME and other tools perform equally well across diverse patient populations. This systematic review indicates significant reporting and knowledge gaps for psychometric properties of outcome measures by race, ethnicity, or skin tone in AD.”

Ms. Kaundinya reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg, the study’s senior author, is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

, according to results from a systematic review.

“AD is associated with considerable heterogeneity across different races and skin tones,” presenting study author Trisha Kaundinya said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “Compared with lighter skin tones, darker skin tones more commonly have diffuse xerosis, Dennis-Morgan lines, hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis. This heterogeneity can be challenging to assess in clinical trials and in practice.”

The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) group has selected several scales by international consensus. For clinical trials, the group recommends the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). In clinical practice, the HOME group recommends the POEM, Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-itch measures. “The psychometric validity and reliability of these outcome measures have undergone robust investigation before, but the validity and reliability of these outcome measures remains uncertain across different races, ethnicities, and skin tones,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, in collaboration with Andrew F. Alexis, MD, MPH, vice-chair for diversity and inclusion for the department of dermatology at Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York, and Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sought to examine reporting of race, ethnicity, and skin tone, and to compare results across these groups from studies of psychometric properties for outcome measures in AD. Under the mentorship of Dr. Silverberg, Ms. Kaundinya, a medical student at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her research associates conducted a systematic review that searched PubMed and Embase and identified 165 relevant published studies of 41,146 individuals.

Of the individuals participating in these 165 studies, 73% had an unspecified racial background, 18% were White, 4% were Asian, 2% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 1% were multiracial/other, and the remainder were American Indian/Alaskan Native. Only 55 of the studies (33%) reported the distribution of race or ethnicity, 5 (3%) reported the distribution of skin tone, and 16 (10%) reported psychometric differences in patients with different races, ethnicities, or skin tones. In addition, only 5 of 113 (4%) studies that did not report race, ethnicity, or skin tone–based differences acknowledged absence of stratification as a limitation.

Of note, significant differential item functioning was found between race subgroups for one or more items of the PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Itch Questionnaire (PIQ) Short Forms, POEM, DLQI, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Itchy Quality of Life (ItchyQOL) scale, 5-dimensions (5D) itch scale, Short Form (SF)-12, and NRS-itch. “Correlations of the POEM with the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) differed the most between skin of color and lighter skin,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

“The POEM did seem to correlate similarly with the DLQI and the EASI in both white and nonwhite participants, which may indicate why this trifecta of instruments is recommended by the HOME group. One study found that substituting the erythema component of the EASI scale with greyness for darker skin, in which erythema is more challenging to assess, did not significantly improve the reliability of EASI. This indicates that further research is needed to investigate how EASI can be modified to perform better in darker skin tones.”

She pointed out that some studies of clinician-reported outcome measures were underpowered to detect meaningful differences between patient subgroups. “There were also insufficient data to perform meta-regression of differences between patient subgroups,” she said. “Overall, future studies are needed to determine whether outcome measures recommended by the HOME and other tools perform equally well across diverse patient populations. This systematic review indicates significant reporting and knowledge gaps for psychometric properties of outcome measures by race, ethnicity, or skin tone in AD.”

Ms. Kaundinya reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg, the study’s senior author, is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2021

Genetic testing for neurofibromatosis 1: An imperfect science

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.