User login

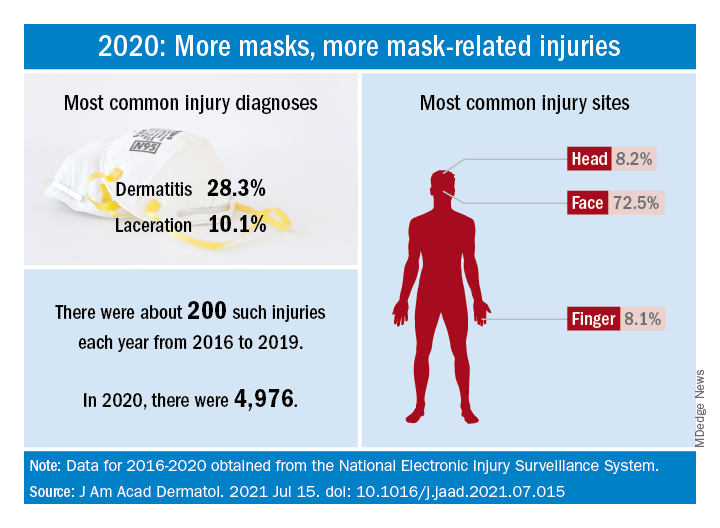

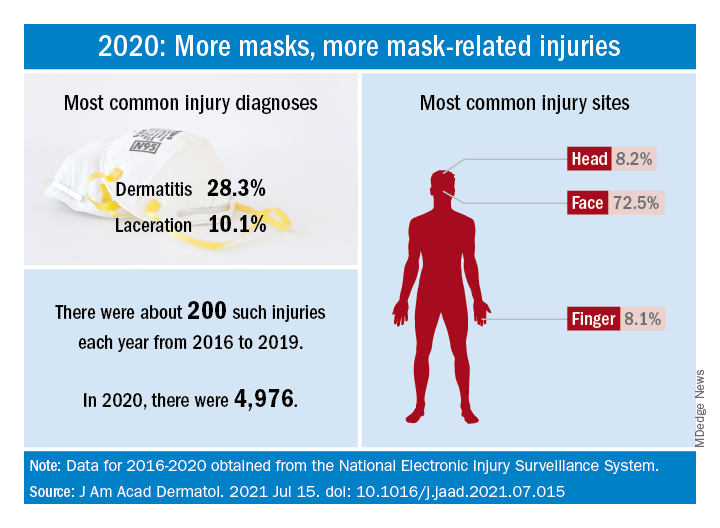

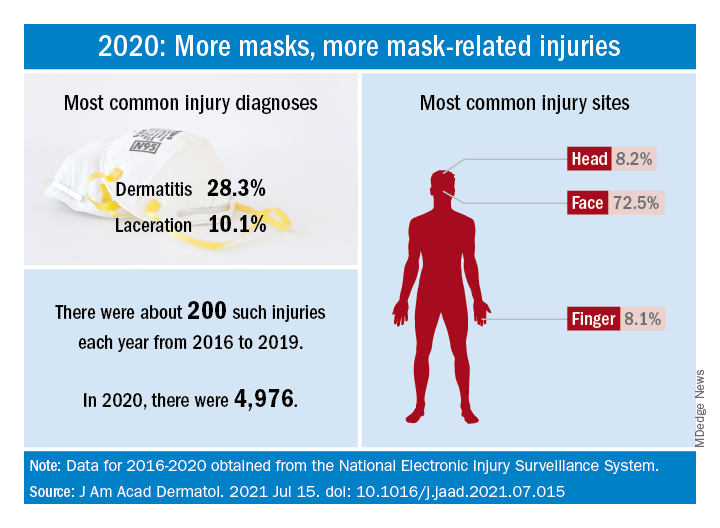

Face mask–related injuries rose dramatically in 2020

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Dyspigmentation common in SOC patients with bullous pemphigoid

Patients of skin of color (SOC) with bullous pemphigoid presented significantly more often with dyspigmentation than did White patients in a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with BP at New York University Langone Health and Bellevue Hospital, also in New York.

“Dyspigmentation in the skin-of-color patient population is important to recognize not only for an objective evaluation of the disease process, but also from a quality of life perspective ... to ensure there is timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the skin-of-color population,” said medical student Payal Shah, BS, of New York University, in presenting the findings at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium.

Ms. Shah and coresearchers identified 94 cases of BP through retrospective view of electronic health records – 59 in White patients and 35 in SOC patients. The physical examination features most commonly found at initial presentation were bullae or vesicles in both White patients (64.4% ) and SOC patients (80%). Erosions or ulcers were also commonly found in both groups (42.4% of White patients and 60% of SOC patients).

Erythema was more commonly found in White patients at initial presentation: 35.6% vs. 14.3% of SOC patients (P = .032). Dyspigmentation, defined as areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, was more commonly found in SOC patients: 54.3% versus 10.2% in White patients (P < .001). The difference in erythema of inflammatory bullae in BP may stem from the fact that erythema is more difficult to discern in patients with darker skin types, Ms. Shah said.

SOC patients also were significantly younger at the time of initial presentation; their mean age was 63 years, compared with 77 years in the White population (P < .001).

The time to diagnosis, defined as the time from initial symptoms to dermatologic diagnosis, was greater for the SOC population –7.6 months vs. 6.2 months for white patients –though the difference was not statistically significant, they said in the abstract .

Dyspigmentation has been shown to be among the top dermatologic concerns of Black patients and has important quality of life implications. “Early diagnosis to prevent difficult-to-treat dyspigmentation is therefore of utmost importance,” they said in the abstract.

Prior research has demonstrated that non-White populations are at greater risk for hospitalization secondary to BP and have a greater risk of disease mortality, Ms. Shah noted in her presentation.

Patients of skin of color (SOC) with bullous pemphigoid presented significantly more often with dyspigmentation than did White patients in a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with BP at New York University Langone Health and Bellevue Hospital, also in New York.

“Dyspigmentation in the skin-of-color patient population is important to recognize not only for an objective evaluation of the disease process, but also from a quality of life perspective ... to ensure there is timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the skin-of-color population,” said medical student Payal Shah, BS, of New York University, in presenting the findings at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium.

Ms. Shah and coresearchers identified 94 cases of BP through retrospective view of electronic health records – 59 in White patients and 35 in SOC patients. The physical examination features most commonly found at initial presentation were bullae or vesicles in both White patients (64.4% ) and SOC patients (80%). Erosions or ulcers were also commonly found in both groups (42.4% of White patients and 60% of SOC patients).

Erythema was more commonly found in White patients at initial presentation: 35.6% vs. 14.3% of SOC patients (P = .032). Dyspigmentation, defined as areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, was more commonly found in SOC patients: 54.3% versus 10.2% in White patients (P < .001). The difference in erythema of inflammatory bullae in BP may stem from the fact that erythema is more difficult to discern in patients with darker skin types, Ms. Shah said.

SOC patients also were significantly younger at the time of initial presentation; their mean age was 63 years, compared with 77 years in the White population (P < .001).

The time to diagnosis, defined as the time from initial symptoms to dermatologic diagnosis, was greater for the SOC population –7.6 months vs. 6.2 months for white patients –though the difference was not statistically significant, they said in the abstract .

Dyspigmentation has been shown to be among the top dermatologic concerns of Black patients and has important quality of life implications. “Early diagnosis to prevent difficult-to-treat dyspigmentation is therefore of utmost importance,” they said in the abstract.

Prior research has demonstrated that non-White populations are at greater risk for hospitalization secondary to BP and have a greater risk of disease mortality, Ms. Shah noted in her presentation.

Patients of skin of color (SOC) with bullous pemphigoid presented significantly more often with dyspigmentation than did White patients in a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with BP at New York University Langone Health and Bellevue Hospital, also in New York.

“Dyspigmentation in the skin-of-color patient population is important to recognize not only for an objective evaluation of the disease process, but also from a quality of life perspective ... to ensure there is timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the skin-of-color population,” said medical student Payal Shah, BS, of New York University, in presenting the findings at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium.

Ms. Shah and coresearchers identified 94 cases of BP through retrospective view of electronic health records – 59 in White patients and 35 in SOC patients. The physical examination features most commonly found at initial presentation were bullae or vesicles in both White patients (64.4% ) and SOC patients (80%). Erosions or ulcers were also commonly found in both groups (42.4% of White patients and 60% of SOC patients).

Erythema was more commonly found in White patients at initial presentation: 35.6% vs. 14.3% of SOC patients (P = .032). Dyspigmentation, defined as areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, was more commonly found in SOC patients: 54.3% versus 10.2% in White patients (P < .001). The difference in erythema of inflammatory bullae in BP may stem from the fact that erythema is more difficult to discern in patients with darker skin types, Ms. Shah said.

SOC patients also were significantly younger at the time of initial presentation; their mean age was 63 years, compared with 77 years in the White population (P < .001).

The time to diagnosis, defined as the time from initial symptoms to dermatologic diagnosis, was greater for the SOC population –7.6 months vs. 6.2 months for white patients –though the difference was not statistically significant, they said in the abstract .

Dyspigmentation has been shown to be among the top dermatologic concerns of Black patients and has important quality of life implications. “Early diagnosis to prevent difficult-to-treat dyspigmentation is therefore of utmost importance,” they said in the abstract.

Prior research has demonstrated that non-White populations are at greater risk for hospitalization secondary to BP and have a greater risk of disease mortality, Ms. Shah noted in her presentation.

FROM SOC 2021

Autoinflammatory diseases ‘not so rare after all,’ expert says

Not long ago, after all.

“Patients with autoinflammatory diseases are all around us, but many go several years without a diagnosis,” Dr. Dissanayake, a rheumatologist at the Autoinflammatory Disease Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The median time to diagnosis has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 5 years. You can imagine that this type of delay can lead to significant issues, not only with quality of life but also morbidity due to unchecked inflammation that can cause organ damage, and in the most severe cases, can result in an early death.”

Effective treatment options such as biologic medications, however, can prevent these negative sequelae if the disease is recognized early. “Dermatologists are in a unique position because they will often be the first specialist to see these patients and therefore make the diagnosis early on and really alter the lives of these patients,” he said.

While it’s common to classify autoinflammatory diseases by presenting features, such as age of onset, associated symptoms, family history/ethnicity, and triggers/alleviating factors for episodes, Dr. Dissanayake prefers to classify them into one of three groups based on pathophysiology, the first being inflammasomopathies. “When activated, an inflammasome is responsible for processing cytokines from the [interleukin]-1 family from the pro form to the active form,” he explained. As a result, if there is dysregulation and overactivity of the inflammasome, there is excessive production of cytokines like IL-1 beta and IL-18 driving the disease.

Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably abdominal pain, nonvasculitic rashes, uveitis, arthritis, elevated white blood cell count/neutrophils, and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Potential treatments include IL-1 blockers.

The second category of autoinflammatory diseases are the interferonopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the antiviral side of the innate immune system. “For example, if you have overactivity of a sensor for a nucleic acid in your cytosol, the cell misinterprets this as a viral infection and will turn on type 1 interferon production,” said Dr. Dissanayake, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “As a result, if you have dysregulation of these pathways, you will get excessive type 1 interferon that contributes to your disease manifestations.” Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably vasculitic rashes, interstitial lung disease, and intracranial calcifications. Inflammatory markers may not be as elevated, and autoantibodies may be present. Janus kinase inhibitors are a potential treatment, he said.

The third category of autoinflammatory diseases are the NF-kappaBopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Clinical characteristics can include fevers with organ involvement that can be highly variable but may include mucocutaneous lesions or granulomatous disease as potential clues. Treatment options depend on the pathway that is involved but tumor necrosis factor blockers often play a role because of the importance of NF-KB in this signaling pathway.

From a skin perspective, most of the rashes Dr. Dissanayake and colleagues see in the rheumatology clinic consist of nonspecific dermohypodermatitis: macules, papules, patches, or plaques. The most common monogenic autoinflammatory disease is Familial Mediterranean Fever syndrome, which “commonly presents as an erysipelas-like rash of the lower extremities, typically below the knee, often over the malleolus,” he said.

Other monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with similar rashes include TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome, Hyper-IgD syndrome, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Other patients present with urticarial rashes, most commonly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). “This is a neutrophilic urticaria, so it tends not to be pruritic and can actually sometimes be tender,” he said. “It also tends not to be as transient as your typical urticaria.” Urticarial rashes can also appear with NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome–2), PLCgamma2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, and Schnitzler syndrome (monoclonal IgM gammopathy).

Patients can also present with pyogenic or pustular lesions, which can appear with pyoderma gangrenosum–related diseases, such as pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis (PAPA) syndrome; pyrin-associated inflammation with neutrophilic dermatosis; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist; deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist; and Majeed syndrome, a mutation in the LPIN2 gene.

The mucocutaneous system can also be affected in autoinflammatory diseases, often presenting with symptoms such as periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, and pharyngitis. Cervical adenitis syndrome is the most common autoinflammatory disease in childhood and can present with aphthous stomatitis, he said, while Behcet’s disease typically presents with oral and genital ulcers. “More recently, monogenic forms of Behcet’s disease have been described, with haploinsufficiency of A20 and RelA, which are both part of the NF-KB pathway,” he said.

Finally, the presence of vasculitic lesions often suggest interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy in infancy, proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2.

Dr. Dissanayake noted that dermatologists should suspect an autoimmune disease if a patient has recurrent fevers, evidence of systemic inflammation on blood work, and if multiple organ systems are involved, especially the lungs, gut, joints, CNS system, and eyes. “Many of these patients have episodic and stereotypical attacks,” he said.

“One of the tools we use in the autoinflammatory clinic is to have patients and families keep a symptom diary where they track the dates of the various symptoms. We can review this during their appointment and try to come up with a diagnosis based on the pattern,” he said.

Since many of these diseases are due to a single gene defect, if there’s any evidence to suggest a monogenic cause, consider an autoinflammatory disease, he added. “If there’s a family history, if there’s consanguinity, or if there’s early age of onset – these may all lead you to think about monogenic autoinflammatory disease.”

During a question-and-answer session, a meeting attendee asked what type of workup he recommends when an autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected. “It partially depends on what organ systems you suspect to be involved,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “As a routine baseline, typically what we would check is CBC and differential, [erythrocyte sedimentation rate] and [C-reactive protein], and we screen for liver transaminases and creatinine to check for liver and kidney issues. A serum albumin will also tell you if the patient is hypoalbuminemic, that there’s been some chronic inflammation and they’re starting to leak the protein out. It’s good to check blood work during the flare and off the flare, to get a sense of the persistence of that inflammation.”

Dr. Dissanayake disclosed that he has received research finding from Gilead Sciences and speaker fees from Novartis.

*This story was updated on 9/20/2021.

Not long ago, after all.

“Patients with autoinflammatory diseases are all around us, but many go several years without a diagnosis,” Dr. Dissanayake, a rheumatologist at the Autoinflammatory Disease Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The median time to diagnosis has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 5 years. You can imagine that this type of delay can lead to significant issues, not only with quality of life but also morbidity due to unchecked inflammation that can cause organ damage, and in the most severe cases, can result in an early death.”

Effective treatment options such as biologic medications, however, can prevent these negative sequelae if the disease is recognized early. “Dermatologists are in a unique position because they will often be the first specialist to see these patients and therefore make the diagnosis early on and really alter the lives of these patients,” he said.

While it’s common to classify autoinflammatory diseases by presenting features, such as age of onset, associated symptoms, family history/ethnicity, and triggers/alleviating factors for episodes, Dr. Dissanayake prefers to classify them into one of three groups based on pathophysiology, the first being inflammasomopathies. “When activated, an inflammasome is responsible for processing cytokines from the [interleukin]-1 family from the pro form to the active form,” he explained. As a result, if there is dysregulation and overactivity of the inflammasome, there is excessive production of cytokines like IL-1 beta and IL-18 driving the disease.

Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably abdominal pain, nonvasculitic rashes, uveitis, arthritis, elevated white blood cell count/neutrophils, and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Potential treatments include IL-1 blockers.

The second category of autoinflammatory diseases are the interferonopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the antiviral side of the innate immune system. “For example, if you have overactivity of a sensor for a nucleic acid in your cytosol, the cell misinterprets this as a viral infection and will turn on type 1 interferon production,” said Dr. Dissanayake, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “As a result, if you have dysregulation of these pathways, you will get excessive type 1 interferon that contributes to your disease manifestations.” Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably vasculitic rashes, interstitial lung disease, and intracranial calcifications. Inflammatory markers may not be as elevated, and autoantibodies may be present. Janus kinase inhibitors are a potential treatment, he said.

The third category of autoinflammatory diseases are the NF-kappaBopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Clinical characteristics can include fevers with organ involvement that can be highly variable but may include mucocutaneous lesions or granulomatous disease as potential clues. Treatment options depend on the pathway that is involved but tumor necrosis factor blockers often play a role because of the importance of NF-KB in this signaling pathway.

From a skin perspective, most of the rashes Dr. Dissanayake and colleagues see in the rheumatology clinic consist of nonspecific dermohypodermatitis: macules, papules, patches, or plaques. The most common monogenic autoinflammatory disease is Familial Mediterranean Fever syndrome, which “commonly presents as an erysipelas-like rash of the lower extremities, typically below the knee, often over the malleolus,” he said.

Other monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with similar rashes include TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome, Hyper-IgD syndrome, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Other patients present with urticarial rashes, most commonly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). “This is a neutrophilic urticaria, so it tends not to be pruritic and can actually sometimes be tender,” he said. “It also tends not to be as transient as your typical urticaria.” Urticarial rashes can also appear with NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome–2), PLCgamma2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, and Schnitzler syndrome (monoclonal IgM gammopathy).

Patients can also present with pyogenic or pustular lesions, which can appear with pyoderma gangrenosum–related diseases, such as pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis (PAPA) syndrome; pyrin-associated inflammation with neutrophilic dermatosis; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist; deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist; and Majeed syndrome, a mutation in the LPIN2 gene.

The mucocutaneous system can also be affected in autoinflammatory diseases, often presenting with symptoms such as periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, and pharyngitis. Cervical adenitis syndrome is the most common autoinflammatory disease in childhood and can present with aphthous stomatitis, he said, while Behcet’s disease typically presents with oral and genital ulcers. “More recently, monogenic forms of Behcet’s disease have been described, with haploinsufficiency of A20 and RelA, which are both part of the NF-KB pathway,” he said.

Finally, the presence of vasculitic lesions often suggest interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy in infancy, proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2.

Dr. Dissanayake noted that dermatologists should suspect an autoimmune disease if a patient has recurrent fevers, evidence of systemic inflammation on blood work, and if multiple organ systems are involved, especially the lungs, gut, joints, CNS system, and eyes. “Many of these patients have episodic and stereotypical attacks,” he said.

“One of the tools we use in the autoinflammatory clinic is to have patients and families keep a symptom diary where they track the dates of the various symptoms. We can review this during their appointment and try to come up with a diagnosis based on the pattern,” he said.

Since many of these diseases are due to a single gene defect, if there’s any evidence to suggest a monogenic cause, consider an autoinflammatory disease, he added. “If there’s a family history, if there’s consanguinity, or if there’s early age of onset – these may all lead you to think about monogenic autoinflammatory disease.”

During a question-and-answer session, a meeting attendee asked what type of workup he recommends when an autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected. “It partially depends on what organ systems you suspect to be involved,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “As a routine baseline, typically what we would check is CBC and differential, [erythrocyte sedimentation rate] and [C-reactive protein], and we screen for liver transaminases and creatinine to check for liver and kidney issues. A serum albumin will also tell you if the patient is hypoalbuminemic, that there’s been some chronic inflammation and they’re starting to leak the protein out. It’s good to check blood work during the flare and off the flare, to get a sense of the persistence of that inflammation.”

Dr. Dissanayake disclosed that he has received research finding from Gilead Sciences and speaker fees from Novartis.

*This story was updated on 9/20/2021.

Not long ago, after all.

“Patients with autoinflammatory diseases are all around us, but many go several years without a diagnosis,” Dr. Dissanayake, a rheumatologist at the Autoinflammatory Disease Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The median time to diagnosis has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 5 years. You can imagine that this type of delay can lead to significant issues, not only with quality of life but also morbidity due to unchecked inflammation that can cause organ damage, and in the most severe cases, can result in an early death.”

Effective treatment options such as biologic medications, however, can prevent these negative sequelae if the disease is recognized early. “Dermatologists are in a unique position because they will often be the first specialist to see these patients and therefore make the diagnosis early on and really alter the lives of these patients,” he said.

While it’s common to classify autoinflammatory diseases by presenting features, such as age of onset, associated symptoms, family history/ethnicity, and triggers/alleviating factors for episodes, Dr. Dissanayake prefers to classify them into one of three groups based on pathophysiology, the first being inflammasomopathies. “When activated, an inflammasome is responsible for processing cytokines from the [interleukin]-1 family from the pro form to the active form,” he explained. As a result, if there is dysregulation and overactivity of the inflammasome, there is excessive production of cytokines like IL-1 beta and IL-18 driving the disease.

Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably abdominal pain, nonvasculitic rashes, uveitis, arthritis, elevated white blood cell count/neutrophils, and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Potential treatments include IL-1 blockers.

The second category of autoinflammatory diseases are the interferonopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the antiviral side of the innate immune system. “For example, if you have overactivity of a sensor for a nucleic acid in your cytosol, the cell misinterprets this as a viral infection and will turn on type 1 interferon production,” said Dr. Dissanayake, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “As a result, if you have dysregulation of these pathways, you will get excessive type 1 interferon that contributes to your disease manifestations.” Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably vasculitic rashes, interstitial lung disease, and intracranial calcifications. Inflammatory markers may not be as elevated, and autoantibodies may be present. Janus kinase inhibitors are a potential treatment, he said.

The third category of autoinflammatory diseases are the NF-kappaBopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Clinical characteristics can include fevers with organ involvement that can be highly variable but may include mucocutaneous lesions or granulomatous disease as potential clues. Treatment options depend on the pathway that is involved but tumor necrosis factor blockers often play a role because of the importance of NF-KB in this signaling pathway.

From a skin perspective, most of the rashes Dr. Dissanayake and colleagues see in the rheumatology clinic consist of nonspecific dermohypodermatitis: macules, papules, patches, or plaques. The most common monogenic autoinflammatory disease is Familial Mediterranean Fever syndrome, which “commonly presents as an erysipelas-like rash of the lower extremities, typically below the knee, often over the malleolus,” he said.

Other monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with similar rashes include TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome, Hyper-IgD syndrome, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Other patients present with urticarial rashes, most commonly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). “This is a neutrophilic urticaria, so it tends not to be pruritic and can actually sometimes be tender,” he said. “It also tends not to be as transient as your typical urticaria.” Urticarial rashes can also appear with NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome–2), PLCgamma2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, and Schnitzler syndrome (monoclonal IgM gammopathy).

Patients can also present with pyogenic or pustular lesions, which can appear with pyoderma gangrenosum–related diseases, such as pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis (PAPA) syndrome; pyrin-associated inflammation with neutrophilic dermatosis; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist; deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist; and Majeed syndrome, a mutation in the LPIN2 gene.

The mucocutaneous system can also be affected in autoinflammatory diseases, often presenting with symptoms such as periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, and pharyngitis. Cervical adenitis syndrome is the most common autoinflammatory disease in childhood and can present with aphthous stomatitis, he said, while Behcet’s disease typically presents with oral and genital ulcers. “More recently, monogenic forms of Behcet’s disease have been described, with haploinsufficiency of A20 and RelA, which are both part of the NF-KB pathway,” he said.

Finally, the presence of vasculitic lesions often suggest interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy in infancy, proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2.

Dr. Dissanayake noted that dermatologists should suspect an autoimmune disease if a patient has recurrent fevers, evidence of systemic inflammation on blood work, and if multiple organ systems are involved, especially the lungs, gut, joints, CNS system, and eyes. “Many of these patients have episodic and stereotypical attacks,” he said.

“One of the tools we use in the autoinflammatory clinic is to have patients and families keep a symptom diary where they track the dates of the various symptoms. We can review this during their appointment and try to come up with a diagnosis based on the pattern,” he said.

Since many of these diseases are due to a single gene defect, if there’s any evidence to suggest a monogenic cause, consider an autoinflammatory disease, he added. “If there’s a family history, if there’s consanguinity, or if there’s early age of onset – these may all lead you to think about monogenic autoinflammatory disease.”

During a question-and-answer session, a meeting attendee asked what type of workup he recommends when an autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected. “It partially depends on what organ systems you suspect to be involved,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “As a routine baseline, typically what we would check is CBC and differential, [erythrocyte sedimentation rate] and [C-reactive protein], and we screen for liver transaminases and creatinine to check for liver and kidney issues. A serum albumin will also tell you if the patient is hypoalbuminemic, that there’s been some chronic inflammation and they’re starting to leak the protein out. It’s good to check blood work during the flare and off the flare, to get a sense of the persistence of that inflammation.”

Dr. Dissanayake disclosed that he has received research finding from Gilead Sciences and speaker fees from Novartis.

*This story was updated on 9/20/2021.

FROM SPD 2021

Expert proposes rethinking the classification of SJS/TEN

In the opinion of Neil H. Shear, MD, a stepwise approach is the best way to diagnose possible drug-induced skin disease and determine the root cause.

“Often, we need to think of more than one cause,” he said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It could be drug X. It could be drug Y. It could be contrast media. We must think broadly and pay special attention to skin of color, overlapping syndromes, and the changing diagnostic assessment over time.”

His suggested diagnostic triangle includes appearance of the rash or lesion(s), systemic impact, and histology. “The first is the appearance,” said Dr. Shear, professor emeritus of dermatology, clinical pharmacology and toxicology, and medicine at the University of Toronto. “Is it exanthem? Is it blistering? Don’t just say drug ‘rash.’ That doesn’t work. You need to know if there are systemic features, and sometimes histologic information can change your approach or diagnosis, but not as often as one might think,” he said, noting that, in his view, the two main factors are appearance and systemic impact.

The presence of fever is a hallmark of systemic problems, he continued, “so if you see fever, you know you’re probably going to be dealing with a complex reaction, so we need to know the morphology.” Consider whether it is simple exanthem (a mild, uncomplicated rash) or complex exanthem (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or fever, malaise, and adenopathy).

As for other morphologies, urticarial lesions could be urticaria or a serum sickness-like reaction, pustular lesions could be acneiform or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, while

Dr. Shear considers SJS/TEN as a spectrum of blistering disease, “because there’s not a single diagnosis,” he said. “There’s a spectrum, if you will, depending on how advanced people are in their disease.” He coauthored a 1991 report describing eight cases of mycoplasma and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “I was surprised at how long that stood up as about the only paper in that area,” he said. “But there’s much more happening now with a proliferation of terms,” he added, referring to MIRM (Mycoplasma pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis), RIME (reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption); and Fuchs syndrome, or SJS without skin lesions.

What was not appreciated in the early classification of SJS, he continued, was a “side basket” of bullous erythema multiforme. “We didn’t know what to call it,” he said. “At one point we called it bullous erythema multiforme. At another point we called it erythema multiforme major. We just didn’t know what it was.”

The appearance and systemic effects of SJS comprise what he termed SJS type 2 – or the early stages of TEN. Taken together, he refers to these two conditions as TEN Spectrum, or TENS. “One of the traps is that TENS can look like varicella, and vice versa, especially in very dark brown or black skin,” Dr. Shear said. “You have to be careful. A biopsy might be worthwhile. Acute lupus has the pathology of TENS but the patients are not as systemically ill as true TENS.”

In 2011, Japanese researchers reported on 38 cases of SJS associated with M. pneumoniae, and 78 cases of drug-induced SJS. They found that 66% of adult patients with M. pneumoniae–associated SJS developed mucocutaneous lesions and fever/respiratory symptoms on the same day, mostly shortness of breath and cough. In contrast, most of the patients aged under 20 years developed fever/respiratory symptoms before mucocutaneous involvement.

“The big clinical differentiator between drug-induced SJS and mycoplasma-induced SJS was respiratory disorder,” said Dr. Shear, who was not affiliated with the study. “That means you’re probably looking at something that’s mycoplasma related [when respiratory problems are present]. Even if you can’t prove it’s mycoplasma related, that probably needs to be the target of your therapy. The idea ... is to make sure it’s clear at the end. One, so they get better, and two, so that we’re not giving drugs needlessly when it was really mycoplasma.”

Noting that HLA-B*15:02 is a marker for carbamazepine-induced SJS and TEN, he said, “a positive HLA test can support the diagnosis, confirm the suspected offending drug, and is valuable for familial genetic counseling.”

As for treatment of SJS, TEN, and other cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions, a randomized Japanese clinical trial evaluating prednisolone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day IV versus etanercept 25-50 mg subcutaneously twice per week in 96 patients with SJS-TEN found that etanercept decreased the mortality rate by 8.3%. In addition, etanercept reduced skin healing time, when compared with prednisolone (a median of 14 vs. 19 days, respectively; P = .010), and was associated with a lower incidence of GI hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 18.2%, respectively; P = .03).

Dr. Shear said that he would like to see better therapeutics for severe, complex patients. “After leaving the hospital, people with SJS or people with TEN need to have ongoing care, consultation, and explanation so they and their families know what drugs are safe in the future.”

Dr. Shear disclosed that he has been a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Medicine, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, LEO Pharma, Otsuka, Janssen, Alpha Laboratories, Lilly, ChemoCentryx, Vivoryon, Galderma, Innovaderm, Chromocell, and Kyowa Kirin.

In the opinion of Neil H. Shear, MD, a stepwise approach is the best way to diagnose possible drug-induced skin disease and determine the root cause.

“Often, we need to think of more than one cause,” he said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It could be drug X. It could be drug Y. It could be contrast media. We must think broadly and pay special attention to skin of color, overlapping syndromes, and the changing diagnostic assessment over time.”

His suggested diagnostic triangle includes appearance of the rash or lesion(s), systemic impact, and histology. “The first is the appearance,” said Dr. Shear, professor emeritus of dermatology, clinical pharmacology and toxicology, and medicine at the University of Toronto. “Is it exanthem? Is it blistering? Don’t just say drug ‘rash.’ That doesn’t work. You need to know if there are systemic features, and sometimes histologic information can change your approach or diagnosis, but not as often as one might think,” he said, noting that, in his view, the two main factors are appearance and systemic impact.

The presence of fever is a hallmark of systemic problems, he continued, “so if you see fever, you know you’re probably going to be dealing with a complex reaction, so we need to know the morphology.” Consider whether it is simple exanthem (a mild, uncomplicated rash) or complex exanthem (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or fever, malaise, and adenopathy).

As for other morphologies, urticarial lesions could be urticaria or a serum sickness-like reaction, pustular lesions could be acneiform or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, while

Dr. Shear considers SJS/TEN as a spectrum of blistering disease, “because there’s not a single diagnosis,” he said. “There’s a spectrum, if you will, depending on how advanced people are in their disease.” He coauthored a 1991 report describing eight cases of mycoplasma and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “I was surprised at how long that stood up as about the only paper in that area,” he said. “But there’s much more happening now with a proliferation of terms,” he added, referring to MIRM (Mycoplasma pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis), RIME (reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption); and Fuchs syndrome, or SJS without skin lesions.

What was not appreciated in the early classification of SJS, he continued, was a “side basket” of bullous erythema multiforme. “We didn’t know what to call it,” he said. “At one point we called it bullous erythema multiforme. At another point we called it erythema multiforme major. We just didn’t know what it was.”

The appearance and systemic effects of SJS comprise what he termed SJS type 2 – or the early stages of TEN. Taken together, he refers to these two conditions as TEN Spectrum, or TENS. “One of the traps is that TENS can look like varicella, and vice versa, especially in very dark brown or black skin,” Dr. Shear said. “You have to be careful. A biopsy might be worthwhile. Acute lupus has the pathology of TENS but the patients are not as systemically ill as true TENS.”

In 2011, Japanese researchers reported on 38 cases of SJS associated with M. pneumoniae, and 78 cases of drug-induced SJS. They found that 66% of adult patients with M. pneumoniae–associated SJS developed mucocutaneous lesions and fever/respiratory symptoms on the same day, mostly shortness of breath and cough. In contrast, most of the patients aged under 20 years developed fever/respiratory symptoms before mucocutaneous involvement.

“The big clinical differentiator between drug-induced SJS and mycoplasma-induced SJS was respiratory disorder,” said Dr. Shear, who was not affiliated with the study. “That means you’re probably looking at something that’s mycoplasma related [when respiratory problems are present]. Even if you can’t prove it’s mycoplasma related, that probably needs to be the target of your therapy. The idea ... is to make sure it’s clear at the end. One, so they get better, and two, so that we’re not giving drugs needlessly when it was really mycoplasma.”

Noting that HLA-B*15:02 is a marker for carbamazepine-induced SJS and TEN, he said, “a positive HLA test can support the diagnosis, confirm the suspected offending drug, and is valuable for familial genetic counseling.”

As for treatment of SJS, TEN, and other cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions, a randomized Japanese clinical trial evaluating prednisolone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day IV versus etanercept 25-50 mg subcutaneously twice per week in 96 patients with SJS-TEN found that etanercept decreased the mortality rate by 8.3%. In addition, etanercept reduced skin healing time, when compared with prednisolone (a median of 14 vs. 19 days, respectively; P = .010), and was associated with a lower incidence of GI hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 18.2%, respectively; P = .03).

Dr. Shear said that he would like to see better therapeutics for severe, complex patients. “After leaving the hospital, people with SJS or people with TEN need to have ongoing care, consultation, and explanation so they and their families know what drugs are safe in the future.”

Dr. Shear disclosed that he has been a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Medicine, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, LEO Pharma, Otsuka, Janssen, Alpha Laboratories, Lilly, ChemoCentryx, Vivoryon, Galderma, Innovaderm, Chromocell, and Kyowa Kirin.

In the opinion of Neil H. Shear, MD, a stepwise approach is the best way to diagnose possible drug-induced skin disease and determine the root cause.

“Often, we need to think of more than one cause,” he said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It could be drug X. It could be drug Y. It could be contrast media. We must think broadly and pay special attention to skin of color, overlapping syndromes, and the changing diagnostic assessment over time.”

His suggested diagnostic triangle includes appearance of the rash or lesion(s), systemic impact, and histology. “The first is the appearance,” said Dr. Shear, professor emeritus of dermatology, clinical pharmacology and toxicology, and medicine at the University of Toronto. “Is it exanthem? Is it blistering? Don’t just say drug ‘rash.’ That doesn’t work. You need to know if there are systemic features, and sometimes histologic information can change your approach or diagnosis, but not as often as one might think,” he said, noting that, in his view, the two main factors are appearance and systemic impact.

The presence of fever is a hallmark of systemic problems, he continued, “so if you see fever, you know you’re probably going to be dealing with a complex reaction, so we need to know the morphology.” Consider whether it is simple exanthem (a mild, uncomplicated rash) or complex exanthem (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or fever, malaise, and adenopathy).

As for other morphologies, urticarial lesions could be urticaria or a serum sickness-like reaction, pustular lesions could be acneiform or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, while

Dr. Shear considers SJS/TEN as a spectrum of blistering disease, “because there’s not a single diagnosis,” he said. “There’s a spectrum, if you will, depending on how advanced people are in their disease.” He coauthored a 1991 report describing eight cases of mycoplasma and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “I was surprised at how long that stood up as about the only paper in that area,” he said. “But there’s much more happening now with a proliferation of terms,” he added, referring to MIRM (Mycoplasma pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis), RIME (reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption); and Fuchs syndrome, or SJS without skin lesions.

What was not appreciated in the early classification of SJS, he continued, was a “side basket” of bullous erythema multiforme. “We didn’t know what to call it,” he said. “At one point we called it bullous erythema multiforme. At another point we called it erythema multiforme major. We just didn’t know what it was.”

The appearance and systemic effects of SJS comprise what he termed SJS type 2 – or the early stages of TEN. Taken together, he refers to these two conditions as TEN Spectrum, or TENS. “One of the traps is that TENS can look like varicella, and vice versa, especially in very dark brown or black skin,” Dr. Shear said. “You have to be careful. A biopsy might be worthwhile. Acute lupus has the pathology of TENS but the patients are not as systemically ill as true TENS.”

In 2011, Japanese researchers reported on 38 cases of SJS associated with M. pneumoniae, and 78 cases of drug-induced SJS. They found that 66% of adult patients with M. pneumoniae–associated SJS developed mucocutaneous lesions and fever/respiratory symptoms on the same day, mostly shortness of breath and cough. In contrast, most of the patients aged under 20 years developed fever/respiratory symptoms before mucocutaneous involvement.

“The big clinical differentiator between drug-induced SJS and mycoplasma-induced SJS was respiratory disorder,” said Dr. Shear, who was not affiliated with the study. “That means you’re probably looking at something that’s mycoplasma related [when respiratory problems are present]. Even if you can’t prove it’s mycoplasma related, that probably needs to be the target of your therapy. The idea ... is to make sure it’s clear at the end. One, so they get better, and two, so that we’re not giving drugs needlessly when it was really mycoplasma.”

Noting that HLA-B*15:02 is a marker for carbamazepine-induced SJS and TEN, he said, “a positive HLA test can support the diagnosis, confirm the suspected offending drug, and is valuable for familial genetic counseling.”

As for treatment of SJS, TEN, and other cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions, a randomized Japanese clinical trial evaluating prednisolone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day IV versus etanercept 25-50 mg subcutaneously twice per week in 96 patients with SJS-TEN found that etanercept decreased the mortality rate by 8.3%. In addition, etanercept reduced skin healing time, when compared with prednisolone (a median of 14 vs. 19 days, respectively; P = .010), and was associated with a lower incidence of GI hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 18.2%, respectively; P = .03).

Dr. Shear said that he would like to see better therapeutics for severe, complex patients. “After leaving the hospital, people with SJS or people with TEN need to have ongoing care, consultation, and explanation so they and their families know what drugs are safe in the future.”

Dr. Shear disclosed that he has been a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Medicine, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, LEO Pharma, Otsuka, Janssen, Alpha Laboratories, Lilly, ChemoCentryx, Vivoryon, Galderma, Innovaderm, Chromocell, and Kyowa Kirin.

FROM SPD 2021

Several uncommon skin disorders related to internal diseases reviewed

and may spawn misdiagnoses, a dermatologist told colleagues.

“Proper diagnosis can lead to an effective management in our patients,” said Jeffrey Callen, MD, professor of medicine and chief of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.), who spoke at the Inaugural Symposium for Inflammatory Skin Disease.

Sarcoidosis

The cause of sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that tends to affect the lungs, “is unknown, but it’s probably an immunologic disorder,” Dr. Callen said, “and there probably is a genetic predisposition.” About 20%-25% of patients with sarcoidosis have skin lesions that are either “specific” (a biopsy that reveals a noncaseating – “naked” – granuloma) or “nonspecific” (most commonly, erythema nodosum, or EN).

The specific lesions in sarcoidosis may occur in parts of the body, such as the knees, which were injured earlier in life and may have taken in foreign bodies, Dr. Callen said. As for nonspecific lesions, about 20% of patients with EN have an acute, self-limiting form of sarcoidosis. “These patients will have bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, anterior uveitis, and polyarthritis. It’s generally treated symptomatically because it goes away on its own.”

He cautioned colleagues to beware of indurated, infiltrative facial lesions known as lupus pernio that are commonly found on the nose. They’re more prevalent in Black patients and possibly women, who are at higher risk of manifestations outside the skin, he said. “If you have it along the nasal rim, you should look into the upper respiratory tract for involvement.”

Dr. Callen recommends an extensive workup in patients with suspected sarcoidosis, including biopsy (with the exception of EN lesions), cultures and special stains, and screening when appropriate, for disease in organs such as the eyes, lungs, heart, and kidneys.

As for treatment, “the disease is in the dermis, and some topical therapies are not highly effective,” he said. There are injections that can be given, including corticosteroids, and there are a variety of oral treatments that are all off label.” These include corticosteroids, antimalarials, allopurinol, and tetracyclines, among several others. Subcutaneous and intravenous treatments are also options, along with surgery and laser therapy to treat specific lesions.

Rosai-Dorfman disease

This rare disorder is caused by overproduction of certain white blood cells in the lymph nodes, which can cause nodular lesions. The disease most often appears in children and young adults, often Black individuals and males. It is fatal in as many as 11% of patients, justifying aggressive treatment in patients with aggressive disease, Dr. Callen said. When it’s limited to the skin, however, “nothing may need to be done.”

Dr. Callen highlighted consensus recommendations about diagnosis and treatment of Rosai-Dorfman disease published in 2018.

He also noted the existence of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, a “solitary process” that appears more commonly in females, and in people of Asian heritage, compared with White individuals. It is characterized by single, clustered or widespread lesions: They can be xanthomatous, erythematous, or red-brown papules, nodules, and plaques. They’re acneiform, pustular, giant granuloma annulare–like, subcutaneous, and vasculitis-like, he said.

While Rosai-Dorfman disease can be linked to lymphoma, hypothyroidism, and lupus erythematosus, “nothing necessarily needs to be done when it’s skin-limited since it can be self-resolving,” he noted. Other treatments include radiotherapy, cryotherapy, excision, topical and oral corticosteroids, thalidomide, and methotrexate.

The disease can be serious, and is fatal in 5% of cases. When a vital organ is threatened, Dr. Callen suggested surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation.

Erdheim-Chester disease

This disease – which is extremely rare, with just 500 cases noted before 2014 – occurs when the body overproduces macrophages. It’s most common in middle-aged people and in men, who make up 75% of cases. About a quarter of patients develop skin lesions: Red-brown to yellow nodules and xanthelasma-like indurated plaques on the eyelids, scalp, neck, trunk, and axillae, and “other cutaneous manifestations have been reported in patients,” Dr. Callen said.

The disease also frequently affects the bones, large vessels, heart, lungs, and central nervous system. Interferon-alpha is the first-line treatment, and there are several other alternative therapies, although 5-year survival (68%) is poor, and it is especially likely to be fatal in those with central nervous system involvement.

Eosinophilic fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) “is a disorder of unknown etiology that causes sclerosis of the skin” without Raynaud’s phenomenon, Dr. Callen said. Look for erythema, swelling, and induration of the extremities that is accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia, and if necessary, confirm the diagnosis with full skin-to-muscle biopsy or MRI.

There are many possible triggers, including strenuous exercise, initiation with hemodialysis, radiation therapy and burns, and graft-versus-host disease. Other potential causes include exposure to medications such as statins, phenytoin, ramipril, subcutaneous heparin, and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The disorder is also linked to autoimmune and hematologic disorders.

Dr. Callen, who highlighted EF guidelines published in 2018, said treatments include physical therapy, prednisone, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and hydroxychloroquine.

Metastatic Crohn’s disease

This is a rare granulomatous inflammation of skin that often affects the genitals, especially in children. It is noncontiguous with the GI tract, and severity of skin involvement does not always parallel the severity of the disease in the GI tract, Dr. Callen said. However, the condition can occur before or simultaneously with the development of GI disease, or after GI surgery.

He highlighted a review of metastatic Crohn’s disease, published in 2014, and noted that there are multiple treatments, including systemic corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and topical therapies.

Dr. Callen reported no relevant disclosures.

and may spawn misdiagnoses, a dermatologist told colleagues.

“Proper diagnosis can lead to an effective management in our patients,” said Jeffrey Callen, MD, professor of medicine and chief of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.), who spoke at the Inaugural Symposium for Inflammatory Skin Disease.

Sarcoidosis

The cause of sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that tends to affect the lungs, “is unknown, but it’s probably an immunologic disorder,” Dr. Callen said, “and there probably is a genetic predisposition.” About 20%-25% of patients with sarcoidosis have skin lesions that are either “specific” (a biopsy that reveals a noncaseating – “naked” – granuloma) or “nonspecific” (most commonly, erythema nodosum, or EN).

The specific lesions in sarcoidosis may occur in parts of the body, such as the knees, which were injured earlier in life and may have taken in foreign bodies, Dr. Callen said. As for nonspecific lesions, about 20% of patients with EN have an acute, self-limiting form of sarcoidosis. “These patients will have bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, anterior uveitis, and polyarthritis. It’s generally treated symptomatically because it goes away on its own.”

He cautioned colleagues to beware of indurated, infiltrative facial lesions known as lupus pernio that are commonly found on the nose. They’re more prevalent in Black patients and possibly women, who are at higher risk of manifestations outside the skin, he said. “If you have it along the nasal rim, you should look into the upper respiratory tract for involvement.”

Dr. Callen recommends an extensive workup in patients with suspected sarcoidosis, including biopsy (with the exception of EN lesions), cultures and special stains, and screening when appropriate, for disease in organs such as the eyes, lungs, heart, and kidneys.

As for treatment, “the disease is in the dermis, and some topical therapies are not highly effective,” he said. There are injections that can be given, including corticosteroids, and there are a variety of oral treatments that are all off label.” These include corticosteroids, antimalarials, allopurinol, and tetracyclines, among several others. Subcutaneous and intravenous treatments are also options, along with surgery and laser therapy to treat specific lesions.

Rosai-Dorfman disease

This rare disorder is caused by overproduction of certain white blood cells in the lymph nodes, which can cause nodular lesions. The disease most often appears in children and young adults, often Black individuals and males. It is fatal in as many as 11% of patients, justifying aggressive treatment in patients with aggressive disease, Dr. Callen said. When it’s limited to the skin, however, “nothing may need to be done.”

Dr. Callen highlighted consensus recommendations about diagnosis and treatment of Rosai-Dorfman disease published in 2018.

He also noted the existence of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, a “solitary process” that appears more commonly in females, and in people of Asian heritage, compared with White individuals. It is characterized by single, clustered or widespread lesions: They can be xanthomatous, erythematous, or red-brown papules, nodules, and plaques. They’re acneiform, pustular, giant granuloma annulare–like, subcutaneous, and vasculitis-like, he said.

While Rosai-Dorfman disease can be linked to lymphoma, hypothyroidism, and lupus erythematosus, “nothing necessarily needs to be done when it’s skin-limited since it can be self-resolving,” he noted. Other treatments include radiotherapy, cryotherapy, excision, topical and oral corticosteroids, thalidomide, and methotrexate.

The disease can be serious, and is fatal in 5% of cases. When a vital organ is threatened, Dr. Callen suggested surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation.

Erdheim-Chester disease

This disease – which is extremely rare, with just 500 cases noted before 2014 – occurs when the body overproduces macrophages. It’s most common in middle-aged people and in men, who make up 75% of cases. About a quarter of patients develop skin lesions: Red-brown to yellow nodules and xanthelasma-like indurated plaques on the eyelids, scalp, neck, trunk, and axillae, and “other cutaneous manifestations have been reported in patients,” Dr. Callen said.

The disease also frequently affects the bones, large vessels, heart, lungs, and central nervous system. Interferon-alpha is the first-line treatment, and there are several other alternative therapies, although 5-year survival (68%) is poor, and it is especially likely to be fatal in those with central nervous system involvement.

Eosinophilic fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) “is a disorder of unknown etiology that causes sclerosis of the skin” without Raynaud’s phenomenon, Dr. Callen said. Look for erythema, swelling, and induration of the extremities that is accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia, and if necessary, confirm the diagnosis with full skin-to-muscle biopsy or MRI.

There are many possible triggers, including strenuous exercise, initiation with hemodialysis, radiation therapy and burns, and graft-versus-host disease. Other potential causes include exposure to medications such as statins, phenytoin, ramipril, subcutaneous heparin, and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The disorder is also linked to autoimmune and hematologic disorders.

Dr. Callen, who highlighted EF guidelines published in 2018, said treatments include physical therapy, prednisone, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and hydroxychloroquine.

Metastatic Crohn’s disease

This is a rare granulomatous inflammation of skin that often affects the genitals, especially in children. It is noncontiguous with the GI tract, and severity of skin involvement does not always parallel the severity of the disease in the GI tract, Dr. Callen said. However, the condition can occur before or simultaneously with the development of GI disease, or after GI surgery.

He highlighted a review of metastatic Crohn’s disease, published in 2014, and noted that there are multiple treatments, including systemic corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and topical therapies.

Dr. Callen reported no relevant disclosures.

and may spawn misdiagnoses, a dermatologist told colleagues.

“Proper diagnosis can lead to an effective management in our patients,” said Jeffrey Callen, MD, professor of medicine and chief of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.), who spoke at the Inaugural Symposium for Inflammatory Skin Disease.

Sarcoidosis

The cause of sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that tends to affect the lungs, “is unknown, but it’s probably an immunologic disorder,” Dr. Callen said, “and there probably is a genetic predisposition.” About 20%-25% of patients with sarcoidosis have skin lesions that are either “specific” (a biopsy that reveals a noncaseating – “naked” – granuloma) or “nonspecific” (most commonly, erythema nodosum, or EN).

The specific lesions in sarcoidosis may occur in parts of the body, such as the knees, which were injured earlier in life and may have taken in foreign bodies, Dr. Callen said. As for nonspecific lesions, about 20% of patients with EN have an acute, self-limiting form of sarcoidosis. “These patients will have bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, anterior uveitis, and polyarthritis. It’s generally treated symptomatically because it goes away on its own.”

He cautioned colleagues to beware of indurated, infiltrative facial lesions known as lupus pernio that are commonly found on the nose. They’re more prevalent in Black patients and possibly women, who are at higher risk of manifestations outside the skin, he said. “If you have it along the nasal rim, you should look into the upper respiratory tract for involvement.”

Dr. Callen recommends an extensive workup in patients with suspected sarcoidosis, including biopsy (with the exception of EN lesions), cultures and special stains, and screening when appropriate, for disease in organs such as the eyes, lungs, heart, and kidneys.

As for treatment, “the disease is in the dermis, and some topical therapies are not highly effective,” he said. There are injections that can be given, including corticosteroids, and there are a variety of oral treatments that are all off label.” These include corticosteroids, antimalarials, allopurinol, and tetracyclines, among several others. Subcutaneous and intravenous treatments are also options, along with surgery and laser therapy to treat specific lesions.

Rosai-Dorfman disease

This rare disorder is caused by overproduction of certain white blood cells in the lymph nodes, which can cause nodular lesions. The disease most often appears in children and young adults, often Black individuals and males. It is fatal in as many as 11% of patients, justifying aggressive treatment in patients with aggressive disease, Dr. Callen said. When it’s limited to the skin, however, “nothing may need to be done.”

Dr. Callen highlighted consensus recommendations about diagnosis and treatment of Rosai-Dorfman disease published in 2018.

He also noted the existence of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, a “solitary process” that appears more commonly in females, and in people of Asian heritage, compared with White individuals. It is characterized by single, clustered or widespread lesions: They can be xanthomatous, erythematous, or red-brown papules, nodules, and plaques. They’re acneiform, pustular, giant granuloma annulare–like, subcutaneous, and vasculitis-like, he said.

While Rosai-Dorfman disease can be linked to lymphoma, hypothyroidism, and lupus erythematosus, “nothing necessarily needs to be done when it’s skin-limited since it can be self-resolving,” he noted. Other treatments include radiotherapy, cryotherapy, excision, topical and oral corticosteroids, thalidomide, and methotrexate.

The disease can be serious, and is fatal in 5% of cases. When a vital organ is threatened, Dr. Callen suggested surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation.

Erdheim-Chester disease

This disease – which is extremely rare, with just 500 cases noted before 2014 – occurs when the body overproduces macrophages. It’s most common in middle-aged people and in men, who make up 75% of cases. About a quarter of patients develop skin lesions: Red-brown to yellow nodules and xanthelasma-like indurated plaques on the eyelids, scalp, neck, trunk, and axillae, and “other cutaneous manifestations have been reported in patients,” Dr. Callen said.

The disease also frequently affects the bones, large vessels, heart, lungs, and central nervous system. Interferon-alpha is the first-line treatment, and there are several other alternative therapies, although 5-year survival (68%) is poor, and it is especially likely to be fatal in those with central nervous system involvement.

Eosinophilic fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) “is a disorder of unknown etiology that causes sclerosis of the skin” without Raynaud’s phenomenon, Dr. Callen said. Look for erythema, swelling, and induration of the extremities that is accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia, and if necessary, confirm the diagnosis with full skin-to-muscle biopsy or MRI.

There are many possible triggers, including strenuous exercise, initiation with hemodialysis, radiation therapy and burns, and graft-versus-host disease. Other potential causes include exposure to medications such as statins, phenytoin, ramipril, subcutaneous heparin, and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The disorder is also linked to autoimmune and hematologic disorders.

Dr. Callen, who highlighted EF guidelines published in 2018, said treatments include physical therapy, prednisone, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and hydroxychloroquine.

Metastatic Crohn’s disease

This is a rare granulomatous inflammation of skin that often affects the genitals, especially in children. It is noncontiguous with the GI tract, and severity of skin involvement does not always parallel the severity of the disease in the GI tract, Dr. Callen said. However, the condition can occur before or simultaneously with the development of GI disease, or after GI surgery.

He highlighted a review of metastatic Crohn’s disease, published in 2014, and noted that there are multiple treatments, including systemic corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and topical therapies.

Dr. Callen reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM SISD 2021

Separation and discoloration of thumb nail

The color change in this case is subtle, but consistent with green nail syndrome also termed chloronychia.

Green nail syndrome is a form of chronic paronychia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is associated with frequent water exposure. Pseudomonas expresses pyocyanin and pyoverdine, leading to the characteristic blue or green coloration. A Woods lamp may reveal neon green fluorescence.

Risk factors include frequent water exposure, use of an instrument to relieve symptoms of an ingrown nail, and chronic immunosuppression. In this case, frequent hand washing being performed by this patient during the COVID-19 pandemic was the likely culprit.

The differential diagnosis includes simple structural onycholysis, onychomycosis, and nail psoriasis. Polymicrobial infection can occur. When in doubt, culture or pathologic examination of nail clippings with Grocott methenamine silver and periodic acid–Schiff can identify coincident fungal infection.1 While systemic pseudomonas infection could also occur with green nail syndrome, the latter is usually only a mild nuisance and not associated with severe disease.

Treatment consists of avoidance of water and instrumentation. Topical sodium hypochlorite 2% solution applied to the nail or acetic acid soaks for 2 to 3 weeks is often curative. Antibiotic therapy may also be used. Topical tobramycin or gentamicin are available as otic or ophthalmic drops and can be applied just under the nail.

The patient was advised to meticulously dry her hands after washing them and to apply 1 drop of topical gentamicin solution 0.3% tid for 3 weeks. The green discoloration cleared in 3 weeks and the onycholysis resolved within 4 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Ohn J, Yu D-A, Park H, et al. Green nail syndrome: analysis of the association with onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:940-942. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.040

The color change in this case is subtle, but consistent with green nail syndrome also termed chloronychia.

Green nail syndrome is a form of chronic paronychia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is associated with frequent water exposure. Pseudomonas expresses pyocyanin and pyoverdine, leading to the characteristic blue or green coloration. A Woods lamp may reveal neon green fluorescence.

Risk factors include frequent water exposure, use of an instrument to relieve symptoms of an ingrown nail, and chronic immunosuppression. In this case, frequent hand washing being performed by this patient during the COVID-19 pandemic was the likely culprit.

The differential diagnosis includes simple structural onycholysis, onychomycosis, and nail psoriasis. Polymicrobial infection can occur. When in doubt, culture or pathologic examination of nail clippings with Grocott methenamine silver and periodic acid–Schiff can identify coincident fungal infection.1 While systemic pseudomonas infection could also occur with green nail syndrome, the latter is usually only a mild nuisance and not associated with severe disease.

Treatment consists of avoidance of water and instrumentation. Topical sodium hypochlorite 2% solution applied to the nail or acetic acid soaks for 2 to 3 weeks is often curative. Antibiotic therapy may also be used. Topical tobramycin or gentamicin are available as otic or ophthalmic drops and can be applied just under the nail.

The patient was advised to meticulously dry her hands after washing them and to apply 1 drop of topical gentamicin solution 0.3% tid for 3 weeks. The green discoloration cleared in 3 weeks and the onycholysis resolved within 4 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The color change in this case is subtle, but consistent with green nail syndrome also termed chloronychia.

Green nail syndrome is a form of chronic paronychia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is associated with frequent water exposure. Pseudomonas expresses pyocyanin and pyoverdine, leading to the characteristic blue or green coloration. A Woods lamp may reveal neon green fluorescence.

Risk factors include frequent water exposure, use of an instrument to relieve symptoms of an ingrown nail, and chronic immunosuppression. In this case, frequent hand washing being performed by this patient during the COVID-19 pandemic was the likely culprit.

The differential diagnosis includes simple structural onycholysis, onychomycosis, and nail psoriasis. Polymicrobial infection can occur. When in doubt, culture or pathologic examination of nail clippings with Grocott methenamine silver and periodic acid–Schiff can identify coincident fungal infection.1 While systemic pseudomonas infection could also occur with green nail syndrome, the latter is usually only a mild nuisance and not associated with severe disease.

Treatment consists of avoidance of water and instrumentation. Topical sodium hypochlorite 2% solution applied to the nail or acetic acid soaks for 2 to 3 weeks is often curative. Antibiotic therapy may also be used. Topical tobramycin or gentamicin are available as otic or ophthalmic drops and can be applied just under the nail.

The patient was advised to meticulously dry her hands after washing them and to apply 1 drop of topical gentamicin solution 0.3% tid for 3 weeks. The green discoloration cleared in 3 weeks and the onycholysis resolved within 4 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Ohn J, Yu D-A, Park H, et al. Green nail syndrome: analysis of the association with onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:940-942. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.040

1. Ohn J, Yu D-A, Park H, et al. Green nail syndrome: analysis of the association with onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:940-942. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.040

FDA approves intravenous immunoglobulin for dermatomyositis

, according to a statement from manufacturer Octapharma USA.

Dermatomyositis is a rare, idiopathic autoimmune disorder that affects approximately 10 out of every million people in the United States, mainly adults in their late 40s to early 60s, according to the company, but children aged 5-15 years can be affected. The disease is characterized by skin rashes, chronic muscle inflammation, progressive muscle weakness, and risk for mortality that is three times higher than for the general population.

There are no previously approved treatments for dermatomyositis prior to Octagam 10%, which also is indicated for chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura in adults.

The approval for dermatomyositis was based on the results of a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (the ProDERM trial) that included 95 adult patients at 36 sites worldwide, with 17 sites in the United States. In the trial, 78.7% of patients with dermatomyositis who were randomized to receive 2 g/kg of Octagam 10% every 4 weeks showed response at 16 weeks, compared with 43.8% of patients who received placebo. Response was based on the 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology myositis response criteria. Placebo patients who switched to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) during a trial extension had response rates at week 40 similar to the original patients at week 16.

“The study gives clinicians much more confidence in the efficacy and safety of intravenous immunoglobulin and provides valuable information about what type of patient is best suited for the treatment,” Rohit Aggarwal, MD, medical director of the Arthritis and Autoimmunity Center at the University of Pittsburgh and a member of the ProDERM study Steering Committee, said in the Octapharma statement.

Safety and tolerability were similar to profiles seen with other IVIG medications, according to the statement. The medication does carry a boxed warning from its chronic ITP approval, cautioning about the potential for thrombosis, renal dysfunction, and acute renal failure.