User login

Study questions canagliflozin amputation risk, but concerns remain

ORLANDO – but clinicians should still favor other options in patients at risk for amputations, according to investigator John Buse, MD, PhD, chief of the division of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Canagliflozin is the only sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor that carries a black box warning of “lower limb amputations, most frequently of the toe and midfoot” but also the leg. The drug doubled the risk versus placebo in its approval trials, particularly in patients with baseline histories of prior amputations, peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, or diabetic foot ulcers.

One trial, for instance, reported 7.5 amputations per 1,000 patient years versus 4.2 with placebo, according to labeling.

The new, observational study, which was funded by canagliflozin’s maker Johnson & Johnson and, with the exception of Dr. Buse, conducted by its employees, found no such connection. Investigators reviewed claims data from 142,800 new users of canagliflozin, 110,897 new users of the competing SGLT2 inhibitors empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and 460,885 new users of other diabetes drugs except for metformin, Dr. Buse said when he presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The hazard ratio for below-knee amputations with canagliflozin versus non-SGLT2 inhibitors was 0.75 (95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.41; P = 0.30). The ratio versus other SGLT2 inhibitors was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.67-1.93; P = 0.53). Overall, there were 1-5 amputations per 1,000 patient years with the drug.

However, the median follow-up was a few months, far shorter than the median follow-up of over 2 years in the randomized trials. “Therefore, the current study had limited statistical power to detect differences in the 6-12 month time period, the time at which amputation risk began to emerge” in the trials, the study report noted. Also, the investigators didn’t parse out results according to baseline amputation risk. Overall, “none of the analyses were sufficiently powered to rule out the possibility of a modest effect” on amputation rates (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/dom.13424).

When moderator Robert H. Eckel, MD, a professor in the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, asked the 150 or so people who heard the presentation if they use SGLT2 inhibitors in their practices, only a small number raised their hands. Few, if any, raised their hands when he asked if the new results would make them more comfortable prescribing canagliflozin.

“I find [the study] somewhat informative,” Dr. Eckel said in an interview afterwards, “but I think the issue is that the prescribing label still demands that patients be informed of the black box warning. I think we are going to have to wait for the longer term outcomes to determine if [amputation] is a molecule effect or a class effect.”

Dr. Buse later said that “I think for the general population of patients with diabetes, they are at low risk for an amputation,” but “if you are at high risk for having an amputation, we really have to take this risk very seriously. [Canagliflozin] may increase your risk for amputation.

“If I have a patient who has had an amputation and I want to use an SGLT2 inhibitor, I wouldn’t use canagliflozin because of the label. I would use empagliflozin because [amputation] is not in the label, and there was no evidence” of it in trials, he added.

The new study, meanwhile, confirmed the cardiac benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 patients. Canagliflozin, for instance, reduced the risk of hospitalization for heart failure by about 60%, compared with non-SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with cardiovascular disease, but it offered no statistically significant heart benefit over other members of its class.

Dr. Buse is an investigator for Johnson and Johnson.

ORLANDO – but clinicians should still favor other options in patients at risk for amputations, according to investigator John Buse, MD, PhD, chief of the division of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Canagliflozin is the only sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor that carries a black box warning of “lower limb amputations, most frequently of the toe and midfoot” but also the leg. The drug doubled the risk versus placebo in its approval trials, particularly in patients with baseline histories of prior amputations, peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, or diabetic foot ulcers.

One trial, for instance, reported 7.5 amputations per 1,000 patient years versus 4.2 with placebo, according to labeling.

The new, observational study, which was funded by canagliflozin’s maker Johnson & Johnson and, with the exception of Dr. Buse, conducted by its employees, found no such connection. Investigators reviewed claims data from 142,800 new users of canagliflozin, 110,897 new users of the competing SGLT2 inhibitors empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and 460,885 new users of other diabetes drugs except for metformin, Dr. Buse said when he presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The hazard ratio for below-knee amputations with canagliflozin versus non-SGLT2 inhibitors was 0.75 (95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.41; P = 0.30). The ratio versus other SGLT2 inhibitors was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.67-1.93; P = 0.53). Overall, there were 1-5 amputations per 1,000 patient years with the drug.

However, the median follow-up was a few months, far shorter than the median follow-up of over 2 years in the randomized trials. “Therefore, the current study had limited statistical power to detect differences in the 6-12 month time period, the time at which amputation risk began to emerge” in the trials, the study report noted. Also, the investigators didn’t parse out results according to baseline amputation risk. Overall, “none of the analyses were sufficiently powered to rule out the possibility of a modest effect” on amputation rates (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/dom.13424).

When moderator Robert H. Eckel, MD, a professor in the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, asked the 150 or so people who heard the presentation if they use SGLT2 inhibitors in their practices, only a small number raised their hands. Few, if any, raised their hands when he asked if the new results would make them more comfortable prescribing canagliflozin.

“I find [the study] somewhat informative,” Dr. Eckel said in an interview afterwards, “but I think the issue is that the prescribing label still demands that patients be informed of the black box warning. I think we are going to have to wait for the longer term outcomes to determine if [amputation] is a molecule effect or a class effect.”

Dr. Buse later said that “I think for the general population of patients with diabetes, they are at low risk for an amputation,” but “if you are at high risk for having an amputation, we really have to take this risk very seriously. [Canagliflozin] may increase your risk for amputation.

“If I have a patient who has had an amputation and I want to use an SGLT2 inhibitor, I wouldn’t use canagliflozin because of the label. I would use empagliflozin because [amputation] is not in the label, and there was no evidence” of it in trials, he added.

The new study, meanwhile, confirmed the cardiac benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 patients. Canagliflozin, for instance, reduced the risk of hospitalization for heart failure by about 60%, compared with non-SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with cardiovascular disease, but it offered no statistically significant heart benefit over other members of its class.

Dr. Buse is an investigator for Johnson and Johnson.

ORLANDO – but clinicians should still favor other options in patients at risk for amputations, according to investigator John Buse, MD, PhD, chief of the division of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Canagliflozin is the only sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor that carries a black box warning of “lower limb amputations, most frequently of the toe and midfoot” but also the leg. The drug doubled the risk versus placebo in its approval trials, particularly in patients with baseline histories of prior amputations, peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, or diabetic foot ulcers.

One trial, for instance, reported 7.5 amputations per 1,000 patient years versus 4.2 with placebo, according to labeling.

The new, observational study, which was funded by canagliflozin’s maker Johnson & Johnson and, with the exception of Dr. Buse, conducted by its employees, found no such connection. Investigators reviewed claims data from 142,800 new users of canagliflozin, 110,897 new users of the competing SGLT2 inhibitors empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and 460,885 new users of other diabetes drugs except for metformin, Dr. Buse said when he presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The hazard ratio for below-knee amputations with canagliflozin versus non-SGLT2 inhibitors was 0.75 (95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.41; P = 0.30). The ratio versus other SGLT2 inhibitors was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.67-1.93; P = 0.53). Overall, there were 1-5 amputations per 1,000 patient years with the drug.

However, the median follow-up was a few months, far shorter than the median follow-up of over 2 years in the randomized trials. “Therefore, the current study had limited statistical power to detect differences in the 6-12 month time period, the time at which amputation risk began to emerge” in the trials, the study report noted. Also, the investigators didn’t parse out results according to baseline amputation risk. Overall, “none of the analyses were sufficiently powered to rule out the possibility of a modest effect” on amputation rates (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/dom.13424).

When moderator Robert H. Eckel, MD, a professor in the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, asked the 150 or so people who heard the presentation if they use SGLT2 inhibitors in their practices, only a small number raised their hands. Few, if any, raised their hands when he asked if the new results would make them more comfortable prescribing canagliflozin.

“I find [the study] somewhat informative,” Dr. Eckel said in an interview afterwards, “but I think the issue is that the prescribing label still demands that patients be informed of the black box warning. I think we are going to have to wait for the longer term outcomes to determine if [amputation] is a molecule effect or a class effect.”

Dr. Buse later said that “I think for the general population of patients with diabetes, they are at low risk for an amputation,” but “if you are at high risk for having an amputation, we really have to take this risk very seriously. [Canagliflozin] may increase your risk for amputation.

“If I have a patient who has had an amputation and I want to use an SGLT2 inhibitor, I wouldn’t use canagliflozin because of the label. I would use empagliflozin because [amputation] is not in the label, and there was no evidence” of it in trials, he added.

The new study, meanwhile, confirmed the cardiac benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 patients. Canagliflozin, for instance, reduced the risk of hospitalization for heart failure by about 60%, compared with non-SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with cardiovascular disease, but it offered no statistically significant heart benefit over other members of its class.

Dr. Buse is an investigator for Johnson and Johnson.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: A large, observational study found no increased risk of below-the-knee amputations with canagliflozin for type 2 diabetes, but clinicians should still favor other options in patients at risk for amputations.

Major finding: The hazard ratio for below-knee amputations with canagliflozin versus non-SGLT2 inhibitors was 0.75 (95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.41; P = 0.30).

Study details: An observational study of over 700,000 patients with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The work was funded by canagliflozin’s maker Johnson & Johnson and, with the exception of the presenter, conducted by its employees.

Navigating travel with diabetes

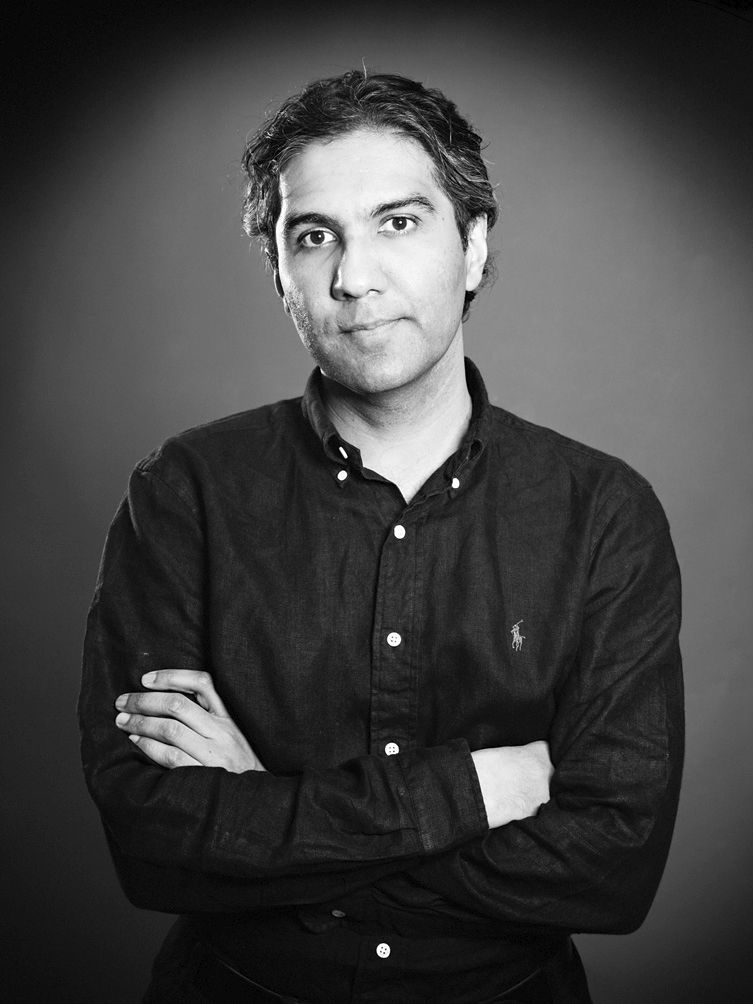

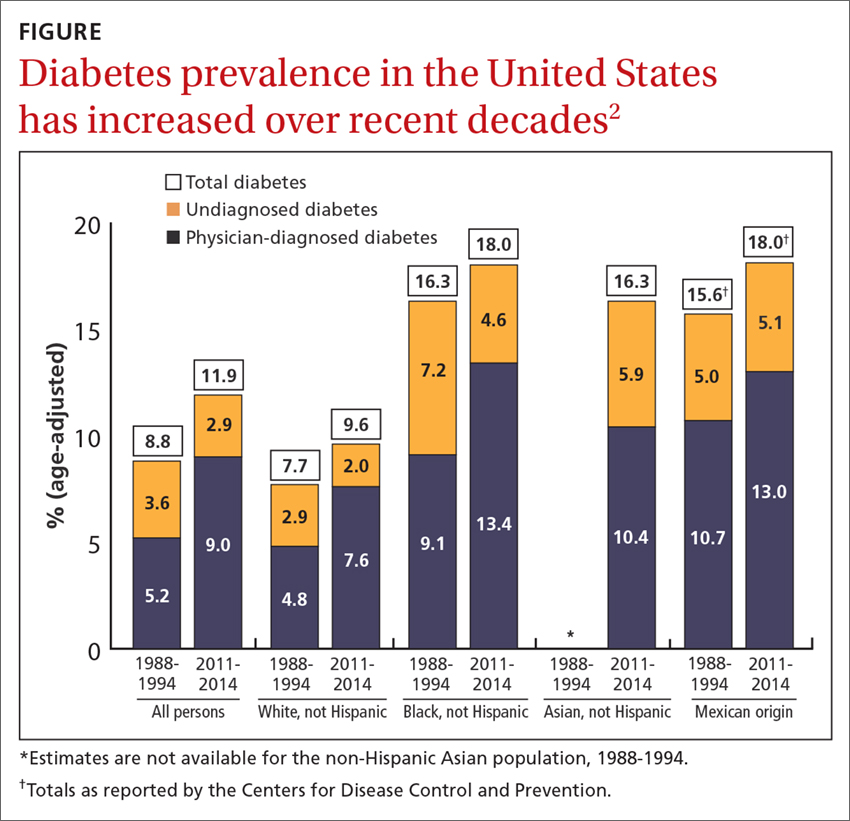

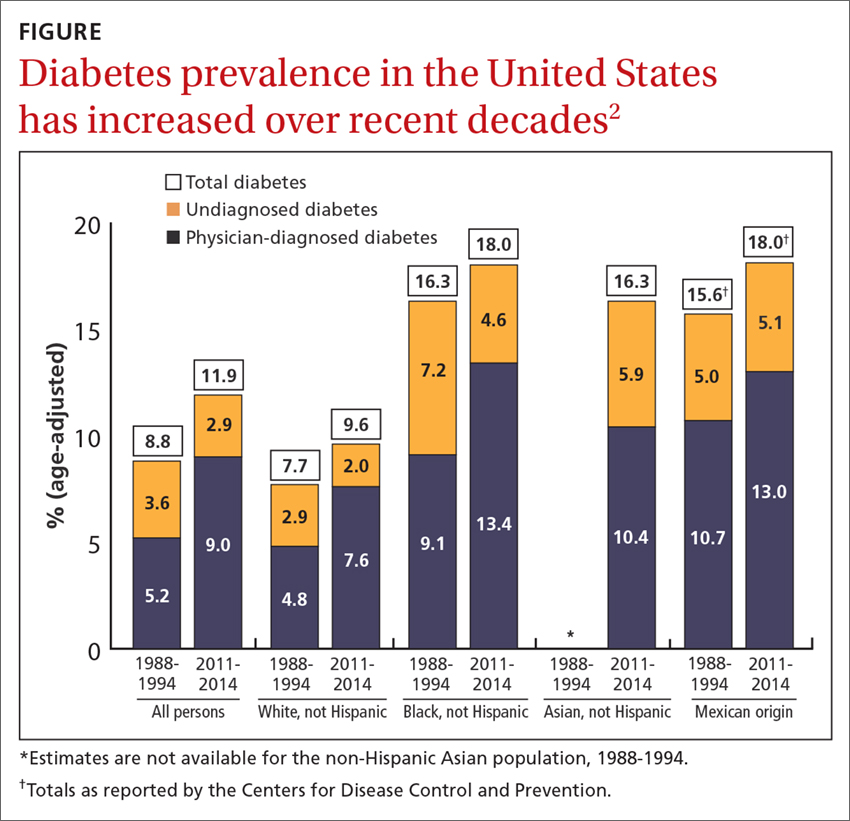

Travel, once reserved for wealthy vacationers and high-level executives, has become a regular experience for many people. The US Travel and Tourism Overview reported that US domestic travel climbed to more than 2.25 billion person-trips in 2017.1 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Travel Association suggest that, based on this frequency and the known rate of diabetes, 17 million people with diabetes travel annually for leisure and 5.6 million for business, and these numbers are expected to increase.2

It stands to reason that as the number of people who travel continues to increase, so too will the number of patients with diabetes seeking medical travel advice. Despite resources available to travelers with diabetes, researchers at the 2016 meeting of the American Diabetes Association noted that only 30% of patients with diabetes who responded to a survey reported being satisfied with the resources available to help them manage their diabetes while traveling.2 This article discusses how clinicians can help patients manage their diabetes while traveling, address common travel questions, and prepare patients for emergencies that may arise while traveling.

PRE-TRIP PREPARATION

Provider visit before travel: Checking the bases

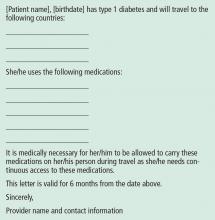

Advise patients to schedule an appointment 4 to 6 weeks before their trip.3 At this appointment, give the patient a healthcare provider travel letter (Figure 1) and prescriptions that the patient can hand-carry en route.3 The provider letter should state that the patient has diabetes and should list all supplies the patient needs. The letter should also include specific medications used by the patient and the devices that deliver these medications, eg, Humalog insulin and U-100 syringes4 to administer insulin, as well as any food and medication allergies.

Prescriptions should be written for patients to use in the event of an emergency during travel. Prescriptions for diabetes medications should be written with generic names to minimize confusion for those traveling internationally. Additionally, all prescriptions should provide enough medication to last throughout the trip.4

Advise patients that rules for filling prescriptions may vary between states and countries.3 Also, the strength of insulin may vary between the United States and other countries. Patients should understand that if they fill their insulin prescription in a foreign country, they may need to purchase new syringes to match the insulin dose. For example, if patients use U-100 syringes and purchase U-40 insulin, they will need to buy U-40 syringes or risk taking too little of a dose.

Remind patients that prescriptions are not necessary for all diabetes supplies but are essential for coverage by insurance companies. Blood glucose testing supplies, ketone strips, and glucose tablets may be purchased in a pharmacy without a prescription. Human insulin may also be purchased over the counter. However, oral medications, glucagon, and analog insulins require a prescription. We suggest that patients who travel have their prescriptions on file at a chain pharmacy rather than an independent one. If they are in the United States, they can go to any branch of the chain pharmacy and easily fill a prescription.

Work with the patient to compile a separate document that details the medication dosing, correction-scale instructions, carbohydrate-to-insulin ratios, and pump settings (basal rates, insulin sensitivity, active insulin time).4 Patients who use an insulin pump should record all pump settings in the event that they need to convert to insulin injections during travel.4 We suggest that all patients with an insulin pump have an alternate insulin method (eg, pens, vials) and that they carry this with them along with basal insulin in case the pump fails. This level of preparation empowers the patient to assume responsibility for his or her own care if a healthcare provider is not available during travel.

Like all travelers, patients with diabetes should confirm that their immunizations are up to date. Encourage patients to the CDC’s page (wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel) to check the list of vaccines necessary for their region of travel.4,5 Many special immunizations can be acquired only from a public health department and not from a clinician’s office.

Additionally, depending on the region of travel, prescribing antibiotics or antidiarrheal medications may be necessary to ensure patient safety and comfort. We also recommend that patients with type 1 diabetes obtain a supply of antibiotics and antidiarrheals because they can become sick quickly.

Packing with diabetes: Double is better

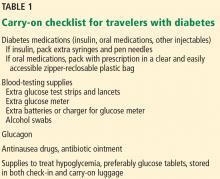

The American Diabetes Association recommends that patients pack at least twice the medication and blood-testing supplies they anticipate needing.3 Reinforce to patients the need to pack all medications and supplies in their carry-on bag and to keep this bag in their possession at all times to avoid damage, loss, and extreme changes in temperature and air pressure, which can adversely affect the activity and stability of insulin.

Ask patients about the activities they plan to participate in and how many days they will be traveling, and then recommend shoes that will encourage appropriate foot care.4 Patients with diabetes should choose comfort over style when selecting footwear. All new shoes should be purchased and “broken in” 2 to 3 weeks before the trip. Alternating shoes decreases the risk of blisters and calluses.4

Emergency abroad: Planning to be prepared

It is crucial to counsel patients on how to respond in an emergency.

Encourage patients with diabetes, especially those who use insulin, to obtain a medical identification bracelet, necklace, or in some cases, a tattoo, that states they use insulin and discloses any allergies.3 This ensures that emergency medical personnel will be aware of the patient’s condition when providing care. Also suggest that your patients have emergency contact information available on their person and their cell phone to expedite assistance in an emergency (Table 2).

Urge patients to determine prior to their departure if their health coverage will change once they leave the state or the country. Some insurance companies require patients to go to a specific healthcare system while others regulate the amount of time a patient can be in the hospital before being transferred home. It is important for patients to be aware of these terms in the event of hospitalization.4 Travel insurance should be considered for international travel.

AIRPORT SECURITY: WHAT TO EXPECT WITH DIABETES

The American Diabetes Association works with the US Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to ensure that passengers with diabetes have access to supplies. Travelers with diabetes are allowed to apply for an optional disability notification card, which discreetly informs officers that the passenger has a condition or device that may affect screening procedures.6

The TSA suggests that, before going through airport screening, patients with diabetes separate their diabetes supplies from their luggage and declare all items.6 Including prescription labels for medications and medical devices helps speed up the security process. Advise patients to carry glucose tablets and other solid foods for treating hypoglycemia when passing through airport security checkpoints.7

Since 2016, the TSA has allowed all diabetes-related supplies, medications, and equipment, including liquids and devices, through security after they have been screened by the x-ray scanner or by hand.7 People with diabetes are allowed to carry insulin and other liquid medications in amounts greater than 3.4 ounces (100 mLs) through airport security checkpoints.

Insulin can pass safely through x-ray scanners, but if patients are concerned, they may request that their insulin be inspected by hand.7 Patients must inform airport security of this decision before the screening process begins. A hand inspection may include swabbing for explosives.

Patients with an insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitoring device may feel uncomfortable during x-ray screening and special security screenings. Remind patients that it is TSA policy that patients do not need to disconnect their devices and can request screening by pat-down rather than x-ray scanner.6 It is the responsibility of the patient to research whether the pump can pass through x-ray scanners.

All patients have the right to request a pat-down and can opt out of passing through the x-ray scanner.6 However, patients need to inform officers about a pump before screening and must understand that the pump may be subject to further inspection. Usually, this additional inspection includes swabbing the patient’s hands to check for explosive material and a simple pat-down of the insulin pump.7

IN-FLIGHT TIPS

Time zones and insulin dosing

Diabetes management is often based on a 24-hour medication schedule. Travel can disrupt this schedule, making it challenging for patients to determine the appropriate medication adjustments. With some assistance, the patient can determine the best course of action based on the direction of travel and the number of time zones crossed.

According to Chandran and Edelman,7 medication adjustments are needed only when the patient is traveling east or west, not north or south. As time zones change, day length changes and, consequently, so does the 24-hour regimen many patients follow. As a general rule, traveling east results in a shortened day, requiring a potential reduction in insulin, while traveling west results in a longer day, possibly requiring an increase in insulin dose.7 However, this is a guideline and may not be applicable to all patients.7

Advise patients to follow local time to administer medications beginning the morning after arrival.7 It is not uncommon, due to changes in meal schedules and dosing, for patients to experience hyperglycemia during travel. They should be prepared to correct this if necessary.

Patients using insulin injections should plan to adjust to the new time zone as soon as possible. If the time change is only 1 or 2 hours, they should take their medications before departure according to their normal home time.7 Upon arrival, they should resume their insulin regimen based on the local time.

Westward travel. If the patient is traveling west with a time change of 3 or more hours, additional changes may be necessary. Advise patients to take their insulin according to their normal home time before departure. The change in dosing and schedule will depend largely on current glucose control, time of travel, and availability of food and glucose during travel. Encourage patients to discuss these matters with you in advance of any long travel.

Eastward travel. When the patient is traveling east with a time change greater than 3 hours, the day will be consequently shortened. On the day of travel, patients should take their morning dose according to home time. If they are concerned about hypoglycemia, suggest that they decrease the dose by 10%.6 On arrival, they should adhere to the new time zone and base insulin dosing on local time.

Advice for insulin pump users. Patients with an insulin pump need make only minimal changes to their dosing schedule. They should continue their routine of basal and bolus doses and change the time on their insulin pump to local time when they arrive. Insulin pump users should bring insulin and syringes as backup; in the event of pump malfunction, the patient should continue to use the same amount of bolus insulin to correct glucose readings and to cover meals.7 As for the basal dose, patients can administer a once-daily injection of long-acting insulin, which can be calculated from their pump or accessed from the list they created as part of their pre-travel preparation.7

Advice for patients on oral diabetes medications

If a patient is taking an oral medication, it is less crucial to adhere to a time schedule. In fact, in some cases it may be preferable to skip a dose and risk slight hyperglycemia for a few hours rather than take medication too close in time and risk hypoglycemia.7

Remind patients to anticipate a change in their oral medication regimen if they travel farther than 5 time zones.7 Encourage patients to research time changes and discuss the necessary changes in medication dosage on the day of travel as well as the specific aspects of their trip. A time-zone converter can be found at www.timeanddate.com.8

WHAT TO EXPECT WHILE ON LAND

Insulin 101

Storing insulin at the appropriate temperature may be a concern. Insulin should be kept between 40°F and 86°F (4°C–30°C).4 Remind patients to carry their insulin with them at all times and to not store it in a car glove compartment or backpack where it can be exposed to excessive sun. The Frio cold pack (ReadyCare, Walnut Creek, CA) is a helpful alternative to refrigeration and can be used to cool insulin when hiking or participating in activities where insulin can overheat. These cooling gel packs are activated when exposed to cold water for 5 to 7 minutes5 and are reusable.

Alert patients that insulin names and concentrations may vary among countries. Most insulins are U-100 concentration, which means that for every 1 mL of liquid there are 100 units of insulin. This is the standard insulin concentration used in the United States. There are U-200, U-300, and U-500 insulins as well. In Europe, the standard concentration is U-40 insulin. Syringe sizes are designed to accommodate either U-100 or U-40 insulin. Review these differences with patients and explain the consequences of mixing insulin concentration with syringes of different sizes. Figure 2 shows how to calculate equivalent doses.

Resort tips: Food, drinks, and excursions

A large component of travel is indulging in local cuisine. Patients with diabetes need to be aware of how different foods can affect their diabetes control. Encourage them to research the foods common to the local cuisine. Websites such as Calorie King, MyFitnessPal, Lose it!, and Nutrition Data can help identify the caloric and nutritional makeup of foods.9

Advise patients to actively monitor how their blood glucose is affected by new foods by checking blood glucose levels before and after each meal.9 Opting for vegetables and protein sources minimizes glucose fluctuations. Remind patients that drinks at resorts may contain more sugar than advertised. Patients should continue to manage their blood glucose by checking levels and by making appropriate insulin adjustments based on the readings. We often advise patients to pack a jar of peanut butter when traveling to ensure a ready source of protein.

Patients who plan to participate in physically challenging activities while travelling should inform all relevant members of the activity staff of their condition. In case of an emergency, hotel staff and guides will be better equipped to help with situations such as hypoglycemia. As noted above, patients should always carry snacks and supplies to treat hypoglycemia in case no alternative food options are available during an excursion. Also, warn patients to avoid walking barefoot. Water shoes are a good alternative to protect feet from cuts and sores.

Patients should inquire about the safety of high-elevation activities. With many glucose meters, every 1,000 feet of elevation results in a 1% to 2% underestimation of blood glucose,10 which could result in an inaccurate reading. If high-altitude activities are planned, advise patients to bring multiple meters to cross-check glucose readings in cases where inaccuracies (due to elevation) are possible.

- US Travel Association. US travel and tourism overview. www.ustravel.org/system/files/media_root/document/Research_Fact-Sheet_US-Travel-and-Tourism-Overview.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Brunk D. Long haul travel turbulent for many with type 1 diabetes. Clinical Endocrinology News 2016. www.mdedge.com/clinicalendocrinologynews/article/109866/diabetes/long-haul-travel-turbulent-many-type-1-diabetes. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. When you travel. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/when-you-travel.html?utm_source=DSH_BLOG&utm_medium=BlogPost&utm_content=051514-travel&utm_campaign=CON. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Kruger DF. The Diabetes Travel Guide. How to travel with diabetes-anywhere in the world. Arlington, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2000.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ health. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. What special concerns may arise? www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/know-your-rights/discrimination/public-accommodations/air-travel-and-diabetes/what-special-concerns-may.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Chandran M, Edelman SV. Have insulin, will fly: diabetes management during air travel and time zone adjustment strategies. Clinical Diabetes 2003; 21(2):82–85. doi:10.2337/diaclin.21.2.82

- Time and Date AS. Time zone converter. timeanddate.com. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Joslin Diabetes Center. Diabetes and travel—10 tips for a safe trip. www.joslin.org/info/diabetes_and_travel_10_tips_for_a_safe_trip.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Jendle J, Adolfsson P. Impact of high altitudes on glucose control. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5(6):1621–1622. doi:10.1177/193229681100500642

Travel, once reserved for wealthy vacationers and high-level executives, has become a regular experience for many people. The US Travel and Tourism Overview reported that US domestic travel climbed to more than 2.25 billion person-trips in 2017.1 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Travel Association suggest that, based on this frequency and the known rate of diabetes, 17 million people with diabetes travel annually for leisure and 5.6 million for business, and these numbers are expected to increase.2

It stands to reason that as the number of people who travel continues to increase, so too will the number of patients with diabetes seeking medical travel advice. Despite resources available to travelers with diabetes, researchers at the 2016 meeting of the American Diabetes Association noted that only 30% of patients with diabetes who responded to a survey reported being satisfied with the resources available to help them manage their diabetes while traveling.2 This article discusses how clinicians can help patients manage their diabetes while traveling, address common travel questions, and prepare patients for emergencies that may arise while traveling.

PRE-TRIP PREPARATION

Provider visit before travel: Checking the bases

Advise patients to schedule an appointment 4 to 6 weeks before their trip.3 At this appointment, give the patient a healthcare provider travel letter (Figure 1) and prescriptions that the patient can hand-carry en route.3 The provider letter should state that the patient has diabetes and should list all supplies the patient needs. The letter should also include specific medications used by the patient and the devices that deliver these medications, eg, Humalog insulin and U-100 syringes4 to administer insulin, as well as any food and medication allergies.

Prescriptions should be written for patients to use in the event of an emergency during travel. Prescriptions for diabetes medications should be written with generic names to minimize confusion for those traveling internationally. Additionally, all prescriptions should provide enough medication to last throughout the trip.4

Advise patients that rules for filling prescriptions may vary between states and countries.3 Also, the strength of insulin may vary between the United States and other countries. Patients should understand that if they fill their insulin prescription in a foreign country, they may need to purchase new syringes to match the insulin dose. For example, if patients use U-100 syringes and purchase U-40 insulin, they will need to buy U-40 syringes or risk taking too little of a dose.

Remind patients that prescriptions are not necessary for all diabetes supplies but are essential for coverage by insurance companies. Blood glucose testing supplies, ketone strips, and glucose tablets may be purchased in a pharmacy without a prescription. Human insulin may also be purchased over the counter. However, oral medications, glucagon, and analog insulins require a prescription. We suggest that patients who travel have their prescriptions on file at a chain pharmacy rather than an independent one. If they are in the United States, they can go to any branch of the chain pharmacy and easily fill a prescription.

Work with the patient to compile a separate document that details the medication dosing, correction-scale instructions, carbohydrate-to-insulin ratios, and pump settings (basal rates, insulin sensitivity, active insulin time).4 Patients who use an insulin pump should record all pump settings in the event that they need to convert to insulin injections during travel.4 We suggest that all patients with an insulin pump have an alternate insulin method (eg, pens, vials) and that they carry this with them along with basal insulin in case the pump fails. This level of preparation empowers the patient to assume responsibility for his or her own care if a healthcare provider is not available during travel.

Like all travelers, patients with diabetes should confirm that their immunizations are up to date. Encourage patients to the CDC’s page (wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel) to check the list of vaccines necessary for their region of travel.4,5 Many special immunizations can be acquired only from a public health department and not from a clinician’s office.

Additionally, depending on the region of travel, prescribing antibiotics or antidiarrheal medications may be necessary to ensure patient safety and comfort. We also recommend that patients with type 1 diabetes obtain a supply of antibiotics and antidiarrheals because they can become sick quickly.

Packing with diabetes: Double is better

The American Diabetes Association recommends that patients pack at least twice the medication and blood-testing supplies they anticipate needing.3 Reinforce to patients the need to pack all medications and supplies in their carry-on bag and to keep this bag in their possession at all times to avoid damage, loss, and extreme changes in temperature and air pressure, which can adversely affect the activity and stability of insulin.

Ask patients about the activities they plan to participate in and how many days they will be traveling, and then recommend shoes that will encourage appropriate foot care.4 Patients with diabetes should choose comfort over style when selecting footwear. All new shoes should be purchased and “broken in” 2 to 3 weeks before the trip. Alternating shoes decreases the risk of blisters and calluses.4

Emergency abroad: Planning to be prepared

It is crucial to counsel patients on how to respond in an emergency.

Encourage patients with diabetes, especially those who use insulin, to obtain a medical identification bracelet, necklace, or in some cases, a tattoo, that states they use insulin and discloses any allergies.3 This ensures that emergency medical personnel will be aware of the patient’s condition when providing care. Also suggest that your patients have emergency contact information available on their person and their cell phone to expedite assistance in an emergency (Table 2).

Urge patients to determine prior to their departure if their health coverage will change once they leave the state or the country. Some insurance companies require patients to go to a specific healthcare system while others regulate the amount of time a patient can be in the hospital before being transferred home. It is important for patients to be aware of these terms in the event of hospitalization.4 Travel insurance should be considered for international travel.

AIRPORT SECURITY: WHAT TO EXPECT WITH DIABETES

The American Diabetes Association works with the US Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to ensure that passengers with diabetes have access to supplies. Travelers with diabetes are allowed to apply for an optional disability notification card, which discreetly informs officers that the passenger has a condition or device that may affect screening procedures.6

The TSA suggests that, before going through airport screening, patients with diabetes separate their diabetes supplies from their luggage and declare all items.6 Including prescription labels for medications and medical devices helps speed up the security process. Advise patients to carry glucose tablets and other solid foods for treating hypoglycemia when passing through airport security checkpoints.7

Since 2016, the TSA has allowed all diabetes-related supplies, medications, and equipment, including liquids and devices, through security after they have been screened by the x-ray scanner or by hand.7 People with diabetes are allowed to carry insulin and other liquid medications in amounts greater than 3.4 ounces (100 mLs) through airport security checkpoints.

Insulin can pass safely through x-ray scanners, but if patients are concerned, they may request that their insulin be inspected by hand.7 Patients must inform airport security of this decision before the screening process begins. A hand inspection may include swabbing for explosives.

Patients with an insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitoring device may feel uncomfortable during x-ray screening and special security screenings. Remind patients that it is TSA policy that patients do not need to disconnect their devices and can request screening by pat-down rather than x-ray scanner.6 It is the responsibility of the patient to research whether the pump can pass through x-ray scanners.

All patients have the right to request a pat-down and can opt out of passing through the x-ray scanner.6 However, patients need to inform officers about a pump before screening and must understand that the pump may be subject to further inspection. Usually, this additional inspection includes swabbing the patient’s hands to check for explosive material and a simple pat-down of the insulin pump.7

IN-FLIGHT TIPS

Time zones and insulin dosing

Diabetes management is often based on a 24-hour medication schedule. Travel can disrupt this schedule, making it challenging for patients to determine the appropriate medication adjustments. With some assistance, the patient can determine the best course of action based on the direction of travel and the number of time zones crossed.

According to Chandran and Edelman,7 medication adjustments are needed only when the patient is traveling east or west, not north or south. As time zones change, day length changes and, consequently, so does the 24-hour regimen many patients follow. As a general rule, traveling east results in a shortened day, requiring a potential reduction in insulin, while traveling west results in a longer day, possibly requiring an increase in insulin dose.7 However, this is a guideline and may not be applicable to all patients.7

Advise patients to follow local time to administer medications beginning the morning after arrival.7 It is not uncommon, due to changes in meal schedules and dosing, for patients to experience hyperglycemia during travel. They should be prepared to correct this if necessary.

Patients using insulin injections should plan to adjust to the new time zone as soon as possible. If the time change is only 1 or 2 hours, they should take their medications before departure according to their normal home time.7 Upon arrival, they should resume their insulin regimen based on the local time.

Westward travel. If the patient is traveling west with a time change of 3 or more hours, additional changes may be necessary. Advise patients to take their insulin according to their normal home time before departure. The change in dosing and schedule will depend largely on current glucose control, time of travel, and availability of food and glucose during travel. Encourage patients to discuss these matters with you in advance of any long travel.

Eastward travel. When the patient is traveling east with a time change greater than 3 hours, the day will be consequently shortened. On the day of travel, patients should take their morning dose according to home time. If they are concerned about hypoglycemia, suggest that they decrease the dose by 10%.6 On arrival, they should adhere to the new time zone and base insulin dosing on local time.

Advice for insulin pump users. Patients with an insulin pump need make only minimal changes to their dosing schedule. They should continue their routine of basal and bolus doses and change the time on their insulin pump to local time when they arrive. Insulin pump users should bring insulin and syringes as backup; in the event of pump malfunction, the patient should continue to use the same amount of bolus insulin to correct glucose readings and to cover meals.7 As for the basal dose, patients can administer a once-daily injection of long-acting insulin, which can be calculated from their pump or accessed from the list they created as part of their pre-travel preparation.7

Advice for patients on oral diabetes medications

If a patient is taking an oral medication, it is less crucial to adhere to a time schedule. In fact, in some cases it may be preferable to skip a dose and risk slight hyperglycemia for a few hours rather than take medication too close in time and risk hypoglycemia.7

Remind patients to anticipate a change in their oral medication regimen if they travel farther than 5 time zones.7 Encourage patients to research time changes and discuss the necessary changes in medication dosage on the day of travel as well as the specific aspects of their trip. A time-zone converter can be found at www.timeanddate.com.8

WHAT TO EXPECT WHILE ON LAND

Insulin 101

Storing insulin at the appropriate temperature may be a concern. Insulin should be kept between 40°F and 86°F (4°C–30°C).4 Remind patients to carry their insulin with them at all times and to not store it in a car glove compartment or backpack where it can be exposed to excessive sun. The Frio cold pack (ReadyCare, Walnut Creek, CA) is a helpful alternative to refrigeration and can be used to cool insulin when hiking or participating in activities where insulin can overheat. These cooling gel packs are activated when exposed to cold water for 5 to 7 minutes5 and are reusable.

Alert patients that insulin names and concentrations may vary among countries. Most insulins are U-100 concentration, which means that for every 1 mL of liquid there are 100 units of insulin. This is the standard insulin concentration used in the United States. There are U-200, U-300, and U-500 insulins as well. In Europe, the standard concentration is U-40 insulin. Syringe sizes are designed to accommodate either U-100 or U-40 insulin. Review these differences with patients and explain the consequences of mixing insulin concentration with syringes of different sizes. Figure 2 shows how to calculate equivalent doses.

Resort tips: Food, drinks, and excursions

A large component of travel is indulging in local cuisine. Patients with diabetes need to be aware of how different foods can affect their diabetes control. Encourage them to research the foods common to the local cuisine. Websites such as Calorie King, MyFitnessPal, Lose it!, and Nutrition Data can help identify the caloric and nutritional makeup of foods.9

Advise patients to actively monitor how their blood glucose is affected by new foods by checking blood glucose levels before and after each meal.9 Opting for vegetables and protein sources minimizes glucose fluctuations. Remind patients that drinks at resorts may contain more sugar than advertised. Patients should continue to manage their blood glucose by checking levels and by making appropriate insulin adjustments based on the readings. We often advise patients to pack a jar of peanut butter when traveling to ensure a ready source of protein.

Patients who plan to participate in physically challenging activities while travelling should inform all relevant members of the activity staff of their condition. In case of an emergency, hotel staff and guides will be better equipped to help with situations such as hypoglycemia. As noted above, patients should always carry snacks and supplies to treat hypoglycemia in case no alternative food options are available during an excursion. Also, warn patients to avoid walking barefoot. Water shoes are a good alternative to protect feet from cuts and sores.

Patients should inquire about the safety of high-elevation activities. With many glucose meters, every 1,000 feet of elevation results in a 1% to 2% underestimation of blood glucose,10 which could result in an inaccurate reading. If high-altitude activities are planned, advise patients to bring multiple meters to cross-check glucose readings in cases where inaccuracies (due to elevation) are possible.

Travel, once reserved for wealthy vacationers and high-level executives, has become a regular experience for many people. The US Travel and Tourism Overview reported that US domestic travel climbed to more than 2.25 billion person-trips in 2017.1 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Travel Association suggest that, based on this frequency and the known rate of diabetes, 17 million people with diabetes travel annually for leisure and 5.6 million for business, and these numbers are expected to increase.2

It stands to reason that as the number of people who travel continues to increase, so too will the number of patients with diabetes seeking medical travel advice. Despite resources available to travelers with diabetes, researchers at the 2016 meeting of the American Diabetes Association noted that only 30% of patients with diabetes who responded to a survey reported being satisfied with the resources available to help them manage their diabetes while traveling.2 This article discusses how clinicians can help patients manage their diabetes while traveling, address common travel questions, and prepare patients for emergencies that may arise while traveling.

PRE-TRIP PREPARATION

Provider visit before travel: Checking the bases

Advise patients to schedule an appointment 4 to 6 weeks before their trip.3 At this appointment, give the patient a healthcare provider travel letter (Figure 1) and prescriptions that the patient can hand-carry en route.3 The provider letter should state that the patient has diabetes and should list all supplies the patient needs. The letter should also include specific medications used by the patient and the devices that deliver these medications, eg, Humalog insulin and U-100 syringes4 to administer insulin, as well as any food and medication allergies.

Prescriptions should be written for patients to use in the event of an emergency during travel. Prescriptions for diabetes medications should be written with generic names to minimize confusion for those traveling internationally. Additionally, all prescriptions should provide enough medication to last throughout the trip.4

Advise patients that rules for filling prescriptions may vary between states and countries.3 Also, the strength of insulin may vary between the United States and other countries. Patients should understand that if they fill their insulin prescription in a foreign country, they may need to purchase new syringes to match the insulin dose. For example, if patients use U-100 syringes and purchase U-40 insulin, they will need to buy U-40 syringes or risk taking too little of a dose.

Remind patients that prescriptions are not necessary for all diabetes supplies but are essential for coverage by insurance companies. Blood glucose testing supplies, ketone strips, and glucose tablets may be purchased in a pharmacy without a prescription. Human insulin may also be purchased over the counter. However, oral medications, glucagon, and analog insulins require a prescription. We suggest that patients who travel have their prescriptions on file at a chain pharmacy rather than an independent one. If they are in the United States, they can go to any branch of the chain pharmacy and easily fill a prescription.

Work with the patient to compile a separate document that details the medication dosing, correction-scale instructions, carbohydrate-to-insulin ratios, and pump settings (basal rates, insulin sensitivity, active insulin time).4 Patients who use an insulin pump should record all pump settings in the event that they need to convert to insulin injections during travel.4 We suggest that all patients with an insulin pump have an alternate insulin method (eg, pens, vials) and that they carry this with them along with basal insulin in case the pump fails. This level of preparation empowers the patient to assume responsibility for his or her own care if a healthcare provider is not available during travel.

Like all travelers, patients with diabetes should confirm that their immunizations are up to date. Encourage patients to the CDC’s page (wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel) to check the list of vaccines necessary for their region of travel.4,5 Many special immunizations can be acquired only from a public health department and not from a clinician’s office.

Additionally, depending on the region of travel, prescribing antibiotics or antidiarrheal medications may be necessary to ensure patient safety and comfort. We also recommend that patients with type 1 diabetes obtain a supply of antibiotics and antidiarrheals because they can become sick quickly.

Packing with diabetes: Double is better

The American Diabetes Association recommends that patients pack at least twice the medication and blood-testing supplies they anticipate needing.3 Reinforce to patients the need to pack all medications and supplies in their carry-on bag and to keep this bag in their possession at all times to avoid damage, loss, and extreme changes in temperature and air pressure, which can adversely affect the activity and stability of insulin.

Ask patients about the activities they plan to participate in and how many days they will be traveling, and then recommend shoes that will encourage appropriate foot care.4 Patients with diabetes should choose comfort over style when selecting footwear. All new shoes should be purchased and “broken in” 2 to 3 weeks before the trip. Alternating shoes decreases the risk of blisters and calluses.4

Emergency abroad: Planning to be prepared

It is crucial to counsel patients on how to respond in an emergency.

Encourage patients with diabetes, especially those who use insulin, to obtain a medical identification bracelet, necklace, or in some cases, a tattoo, that states they use insulin and discloses any allergies.3 This ensures that emergency medical personnel will be aware of the patient’s condition when providing care. Also suggest that your patients have emergency contact information available on their person and their cell phone to expedite assistance in an emergency (Table 2).

Urge patients to determine prior to their departure if their health coverage will change once they leave the state or the country. Some insurance companies require patients to go to a specific healthcare system while others regulate the amount of time a patient can be in the hospital before being transferred home. It is important for patients to be aware of these terms in the event of hospitalization.4 Travel insurance should be considered for international travel.

AIRPORT SECURITY: WHAT TO EXPECT WITH DIABETES

The American Diabetes Association works with the US Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to ensure that passengers with diabetes have access to supplies. Travelers with diabetes are allowed to apply for an optional disability notification card, which discreetly informs officers that the passenger has a condition or device that may affect screening procedures.6

The TSA suggests that, before going through airport screening, patients with diabetes separate their diabetes supplies from their luggage and declare all items.6 Including prescription labels for medications and medical devices helps speed up the security process. Advise patients to carry glucose tablets and other solid foods for treating hypoglycemia when passing through airport security checkpoints.7

Since 2016, the TSA has allowed all diabetes-related supplies, medications, and equipment, including liquids and devices, through security after they have been screened by the x-ray scanner or by hand.7 People with diabetes are allowed to carry insulin and other liquid medications in amounts greater than 3.4 ounces (100 mLs) through airport security checkpoints.

Insulin can pass safely through x-ray scanners, but if patients are concerned, they may request that their insulin be inspected by hand.7 Patients must inform airport security of this decision before the screening process begins. A hand inspection may include swabbing for explosives.

Patients with an insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitoring device may feel uncomfortable during x-ray screening and special security screenings. Remind patients that it is TSA policy that patients do not need to disconnect their devices and can request screening by pat-down rather than x-ray scanner.6 It is the responsibility of the patient to research whether the pump can pass through x-ray scanners.

All patients have the right to request a pat-down and can opt out of passing through the x-ray scanner.6 However, patients need to inform officers about a pump before screening and must understand that the pump may be subject to further inspection. Usually, this additional inspection includes swabbing the patient’s hands to check for explosive material and a simple pat-down of the insulin pump.7

IN-FLIGHT TIPS

Time zones and insulin dosing

Diabetes management is often based on a 24-hour medication schedule. Travel can disrupt this schedule, making it challenging for patients to determine the appropriate medication adjustments. With some assistance, the patient can determine the best course of action based on the direction of travel and the number of time zones crossed.

According to Chandran and Edelman,7 medication adjustments are needed only when the patient is traveling east or west, not north or south. As time zones change, day length changes and, consequently, so does the 24-hour regimen many patients follow. As a general rule, traveling east results in a shortened day, requiring a potential reduction in insulin, while traveling west results in a longer day, possibly requiring an increase in insulin dose.7 However, this is a guideline and may not be applicable to all patients.7

Advise patients to follow local time to administer medications beginning the morning after arrival.7 It is not uncommon, due to changes in meal schedules and dosing, for patients to experience hyperglycemia during travel. They should be prepared to correct this if necessary.

Patients using insulin injections should plan to adjust to the new time zone as soon as possible. If the time change is only 1 or 2 hours, they should take their medications before departure according to their normal home time.7 Upon arrival, they should resume their insulin regimen based on the local time.

Westward travel. If the patient is traveling west with a time change of 3 or more hours, additional changes may be necessary. Advise patients to take their insulin according to their normal home time before departure. The change in dosing and schedule will depend largely on current glucose control, time of travel, and availability of food and glucose during travel. Encourage patients to discuss these matters with you in advance of any long travel.

Eastward travel. When the patient is traveling east with a time change greater than 3 hours, the day will be consequently shortened. On the day of travel, patients should take their morning dose according to home time. If they are concerned about hypoglycemia, suggest that they decrease the dose by 10%.6 On arrival, they should adhere to the new time zone and base insulin dosing on local time.

Advice for insulin pump users. Patients with an insulin pump need make only minimal changes to their dosing schedule. They should continue their routine of basal and bolus doses and change the time on their insulin pump to local time when they arrive. Insulin pump users should bring insulin and syringes as backup; in the event of pump malfunction, the patient should continue to use the same amount of bolus insulin to correct glucose readings and to cover meals.7 As for the basal dose, patients can administer a once-daily injection of long-acting insulin, which can be calculated from their pump or accessed from the list they created as part of their pre-travel preparation.7

Advice for patients on oral diabetes medications

If a patient is taking an oral medication, it is less crucial to adhere to a time schedule. In fact, in some cases it may be preferable to skip a dose and risk slight hyperglycemia for a few hours rather than take medication too close in time and risk hypoglycemia.7

Remind patients to anticipate a change in their oral medication regimen if they travel farther than 5 time zones.7 Encourage patients to research time changes and discuss the necessary changes in medication dosage on the day of travel as well as the specific aspects of their trip. A time-zone converter can be found at www.timeanddate.com.8

WHAT TO EXPECT WHILE ON LAND

Insulin 101

Storing insulin at the appropriate temperature may be a concern. Insulin should be kept between 40°F and 86°F (4°C–30°C).4 Remind patients to carry their insulin with them at all times and to not store it in a car glove compartment or backpack where it can be exposed to excessive sun. The Frio cold pack (ReadyCare, Walnut Creek, CA) is a helpful alternative to refrigeration and can be used to cool insulin when hiking or participating in activities where insulin can overheat. These cooling gel packs are activated when exposed to cold water for 5 to 7 minutes5 and are reusable.

Alert patients that insulin names and concentrations may vary among countries. Most insulins are U-100 concentration, which means that for every 1 mL of liquid there are 100 units of insulin. This is the standard insulin concentration used in the United States. There are U-200, U-300, and U-500 insulins as well. In Europe, the standard concentration is U-40 insulin. Syringe sizes are designed to accommodate either U-100 or U-40 insulin. Review these differences with patients and explain the consequences of mixing insulin concentration with syringes of different sizes. Figure 2 shows how to calculate equivalent doses.

Resort tips: Food, drinks, and excursions

A large component of travel is indulging in local cuisine. Patients with diabetes need to be aware of how different foods can affect their diabetes control. Encourage them to research the foods common to the local cuisine. Websites such as Calorie King, MyFitnessPal, Lose it!, and Nutrition Data can help identify the caloric and nutritional makeup of foods.9

Advise patients to actively monitor how their blood glucose is affected by new foods by checking blood glucose levels before and after each meal.9 Opting for vegetables and protein sources minimizes glucose fluctuations. Remind patients that drinks at resorts may contain more sugar than advertised. Patients should continue to manage their blood glucose by checking levels and by making appropriate insulin adjustments based on the readings. We often advise patients to pack a jar of peanut butter when traveling to ensure a ready source of protein.

Patients who plan to participate in physically challenging activities while travelling should inform all relevant members of the activity staff of their condition. In case of an emergency, hotel staff and guides will be better equipped to help with situations such as hypoglycemia. As noted above, patients should always carry snacks and supplies to treat hypoglycemia in case no alternative food options are available during an excursion. Also, warn patients to avoid walking barefoot. Water shoes are a good alternative to protect feet from cuts and sores.

Patients should inquire about the safety of high-elevation activities. With many glucose meters, every 1,000 feet of elevation results in a 1% to 2% underestimation of blood glucose,10 which could result in an inaccurate reading. If high-altitude activities are planned, advise patients to bring multiple meters to cross-check glucose readings in cases where inaccuracies (due to elevation) are possible.

- US Travel Association. US travel and tourism overview. www.ustravel.org/system/files/media_root/document/Research_Fact-Sheet_US-Travel-and-Tourism-Overview.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Brunk D. Long haul travel turbulent for many with type 1 diabetes. Clinical Endocrinology News 2016. www.mdedge.com/clinicalendocrinologynews/article/109866/diabetes/long-haul-travel-turbulent-many-type-1-diabetes. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. When you travel. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/when-you-travel.html?utm_source=DSH_BLOG&utm_medium=BlogPost&utm_content=051514-travel&utm_campaign=CON. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Kruger DF. The Diabetes Travel Guide. How to travel with diabetes-anywhere in the world. Arlington, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2000.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ health. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. What special concerns may arise? www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/know-your-rights/discrimination/public-accommodations/air-travel-and-diabetes/what-special-concerns-may.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Chandran M, Edelman SV. Have insulin, will fly: diabetes management during air travel and time zone adjustment strategies. Clinical Diabetes 2003; 21(2):82–85. doi:10.2337/diaclin.21.2.82

- Time and Date AS. Time zone converter. timeanddate.com. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Joslin Diabetes Center. Diabetes and travel—10 tips for a safe trip. www.joslin.org/info/diabetes_and_travel_10_tips_for_a_safe_trip.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Jendle J, Adolfsson P. Impact of high altitudes on glucose control. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5(6):1621–1622. doi:10.1177/193229681100500642

- US Travel Association. US travel and tourism overview. www.ustravel.org/system/files/media_root/document/Research_Fact-Sheet_US-Travel-and-Tourism-Overview.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Brunk D. Long haul travel turbulent for many with type 1 diabetes. Clinical Endocrinology News 2016. www.mdedge.com/clinicalendocrinologynews/article/109866/diabetes/long-haul-travel-turbulent-many-type-1-diabetes. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. When you travel. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/when-you-travel.html?utm_source=DSH_BLOG&utm_medium=BlogPost&utm_content=051514-travel&utm_campaign=CON. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Kruger DF. The Diabetes Travel Guide. How to travel with diabetes-anywhere in the world. Arlington, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2000.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ health. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- American Diabetes Association. What special concerns may arise? www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/know-your-rights/discrimination/public-accommodations/air-travel-and-diabetes/what-special-concerns-may.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Chandran M, Edelman SV. Have insulin, will fly: diabetes management during air travel and time zone adjustment strategies. Clinical Diabetes 2003; 21(2):82–85. doi:10.2337/diaclin.21.2.82

- Time and Date AS. Time zone converter. timeanddate.com. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Joslin Diabetes Center. Diabetes and travel—10 tips for a safe trip. www.joslin.org/info/diabetes_and_travel_10_tips_for_a_safe_trip.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Jendle J, Adolfsson P. Impact of high altitudes on glucose control. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5(6):1621–1622. doi:10.1177/193229681100500642

KEY POINTS

- Patients should pack all diabetes medications and supplies in a carry-on bag and keep it in their possession at all times.

- A travel letter will facilitate easy transfer through security and customs.

- Patients should always take more supplies than needed to accommodate changes in travel plans.

- If patients will cross multiple time zones during their travel, they will likely need to adjust their medication and food schedules.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome due to hyperosmolar hyperglycemia

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

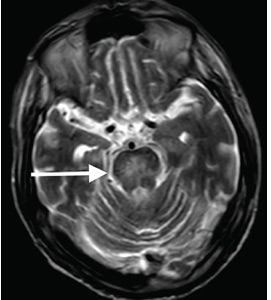

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

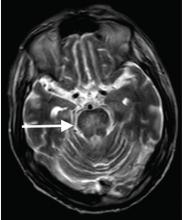

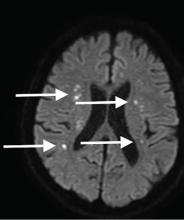

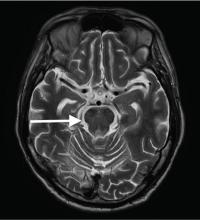

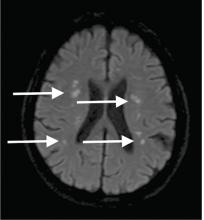

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045

- Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central pontine myelinolysis in the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. Med Princ Pract 2013; 22(1):96–99. doi:10.1159/000341718

- Rodríguez-Velver KV, Soto-Garcia AJ, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as the initial manifestation of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014; 2014:652523. doi:10.1155/2014/652523

- Chang YM. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with diabetic hyperglycemia. JSM Clin Case Rep 2014; 2(6):1059.

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.