User login

Tinea capitis

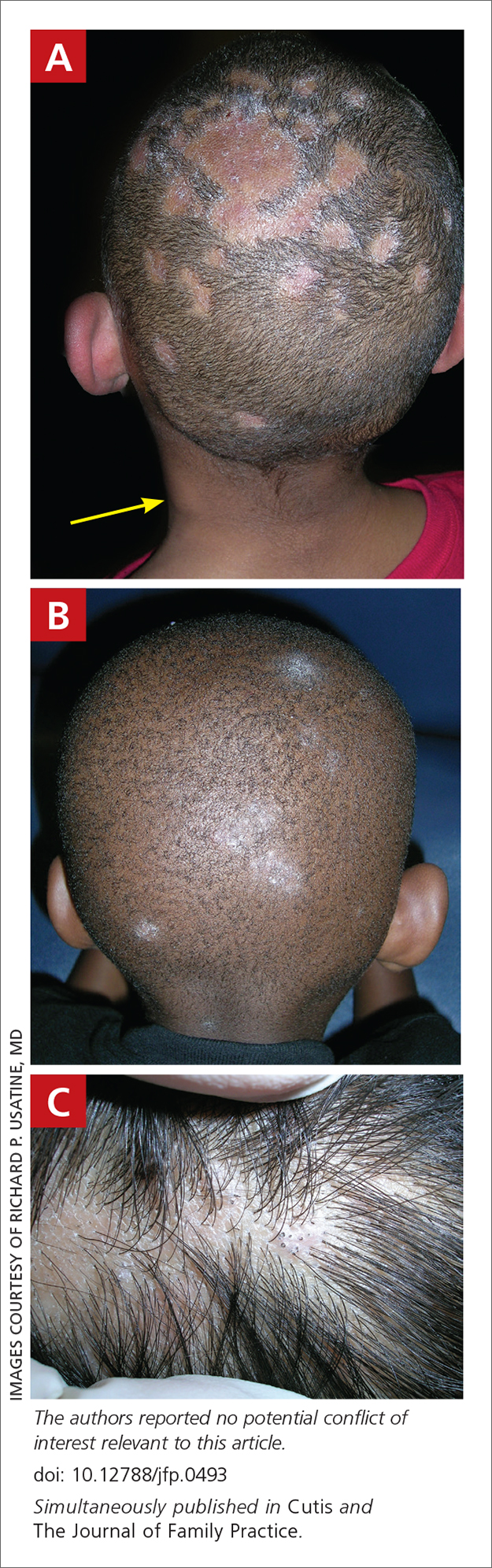

THE COMPARISON

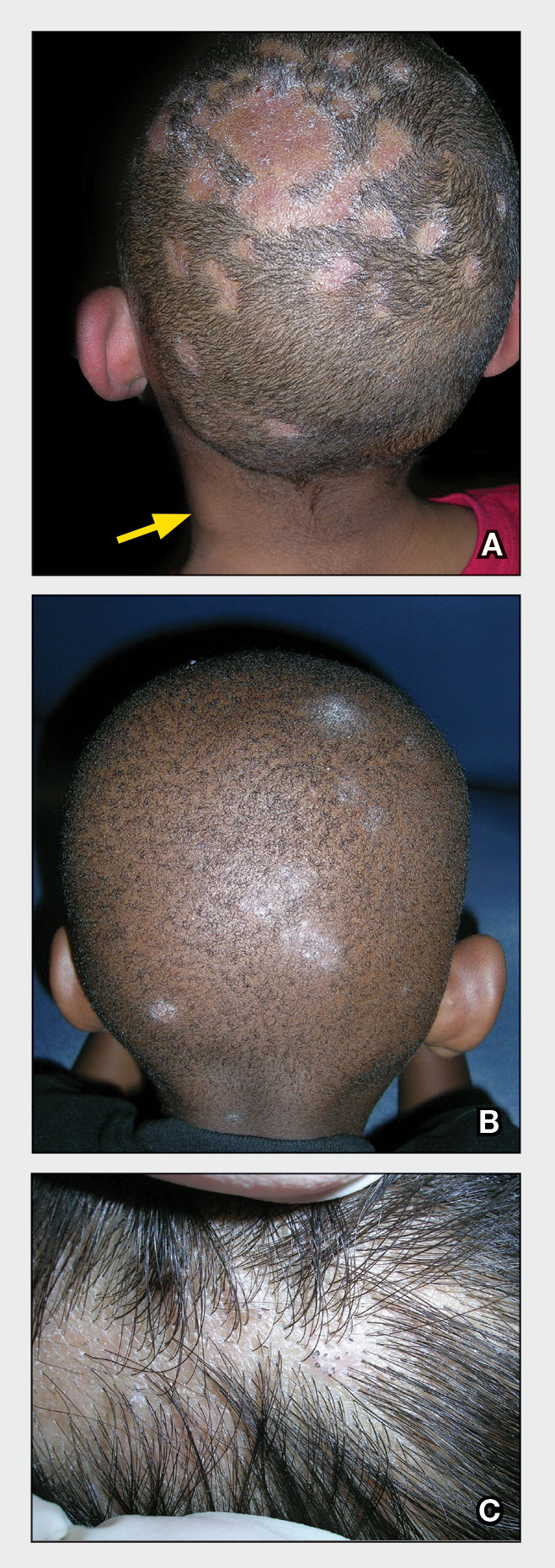

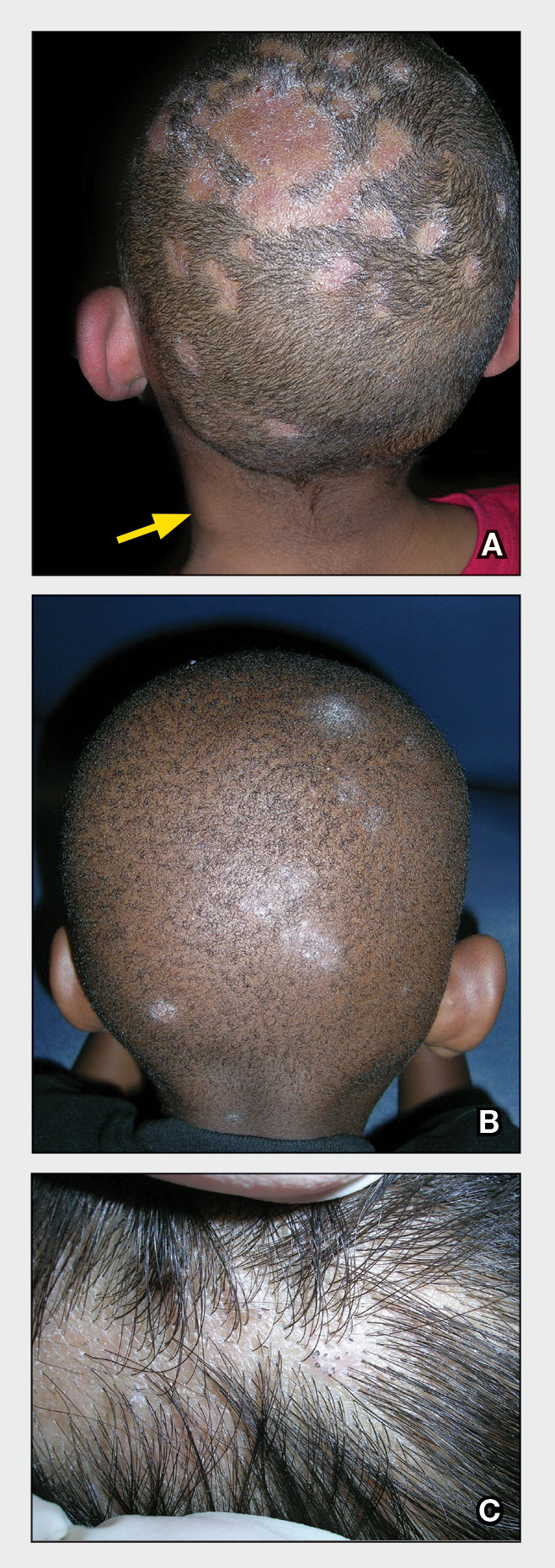

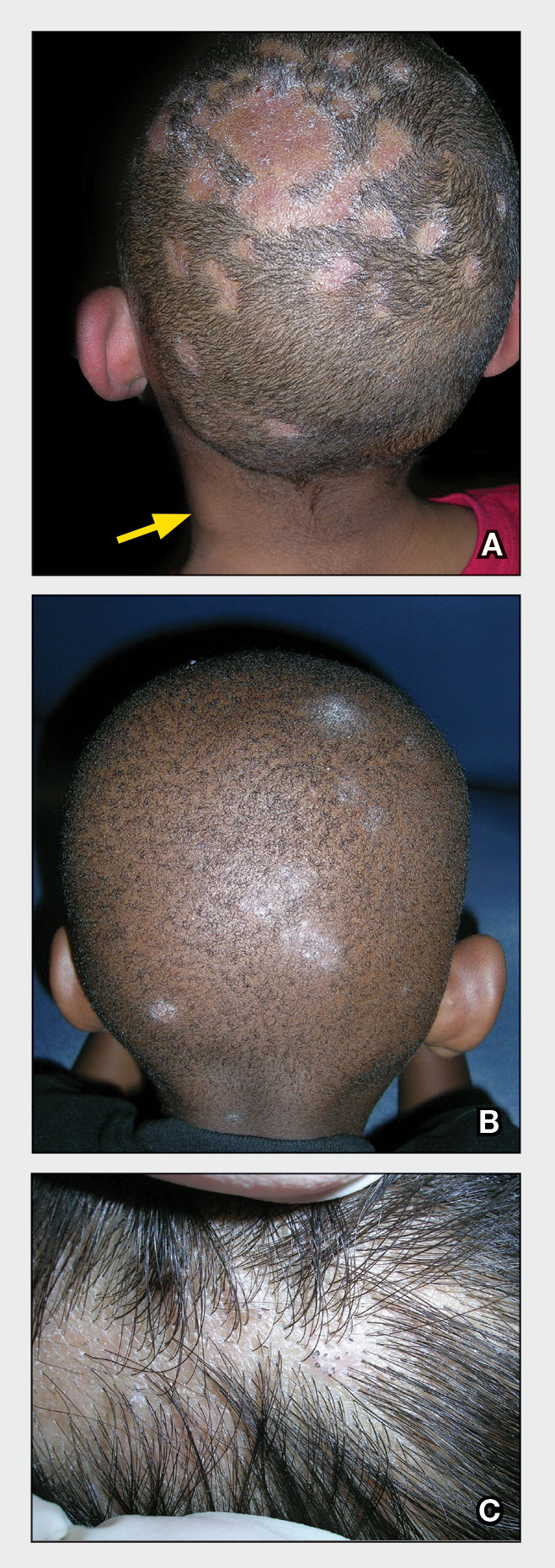

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

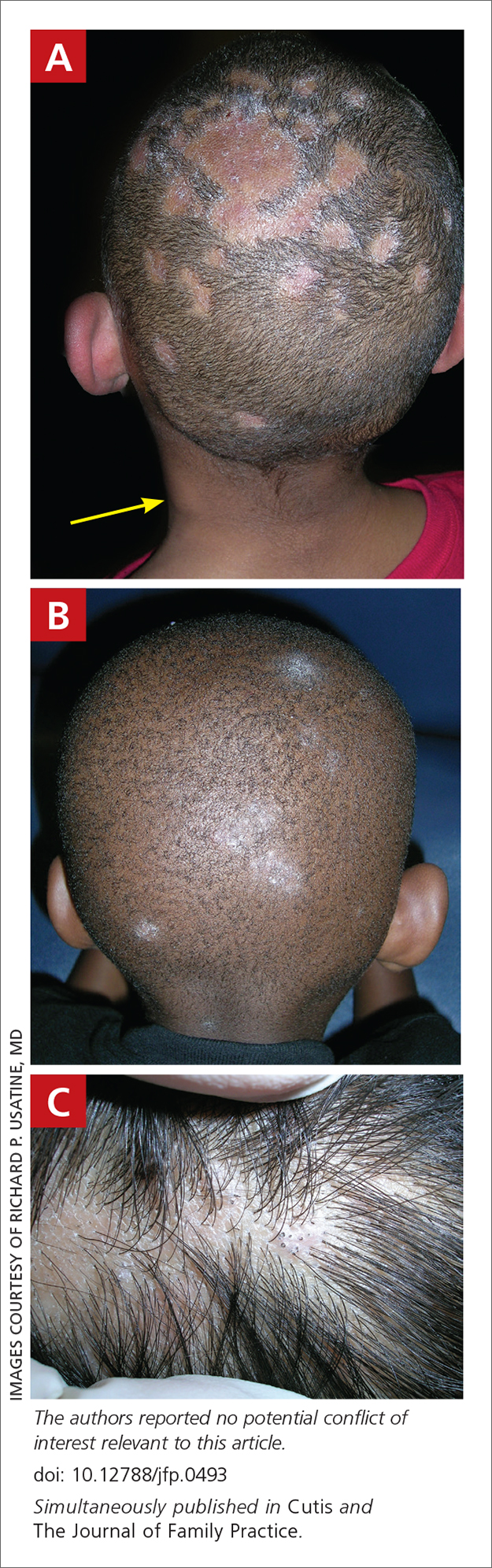

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

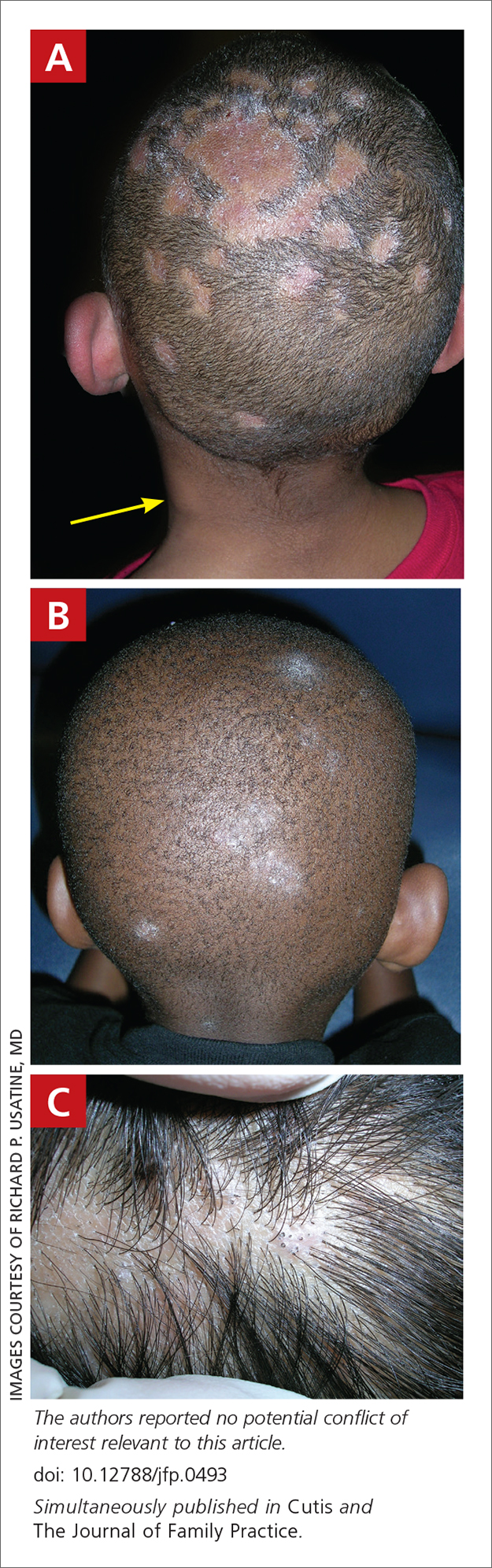

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) caused by M canis. M canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations:

- broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp

- diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis

- well-demarcated annular plaques

- exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation

- scalp pruritus

- occipital scalp lymphadenopathy.

Worth noting

Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp. However, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to false-negative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5

Health disparity highlight

A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

1. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088

2. Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522

3. Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

4. Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

5. Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi: 10.1111/pde.14092

6. Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

Tinea Capitis

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) such as M canis. Microsporum canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations: • broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp • diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis • well-demarcated annular plaques • exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation • scalp pruritus • occipital scalp lymphadenopathy. Worth noting Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp; however, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to falsenegative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5 Health disparity highlight A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management [published online July 12, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi:10.1111/jdv.15088

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study [published online April 19, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2522

- Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

- Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

- Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015 [published online January 20, 2020]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi:10.1111 /pde.14092

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria [published online April 16, 2008]. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) such as M canis. Microsporum canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations: • broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp • diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis • well-demarcated annular plaques • exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation • scalp pruritus • occipital scalp lymphadenopathy. Worth noting Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp; however, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to falsenegative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5 Health disparity highlight A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

THE COMPARISON

A Areas of alopecia with erythema and scale in a young Black boy with tinea capitis. He also had an enlarged posterior cervical lymph node (arrow) from this fungal infection.

B White patches of scale from tinea capitis in a young Black boy with no obvious hair loss; however, a potassium hydroxide preparation from the scale was positive for fungus.

C A subtle area of tinea capitis on the scalp of a Latina girl showed comma hairs.

Tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp in school-aged children. The infection is spread by close contact with infected people or with their personal items, including combs, brushes, pillowcases, and hats, as well as animals. It is uncommon in adults.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection among school-aged children worldwide.1 In a US-based study of more than 10,000 school-aged children, the prevalence of tinea capitis ranged from 0% to 19.4%, with Black children having the highest rates of infection at 12.9%.2 However, people of all races and ages may develop tinea capitis.3

Tinea capitis most commonly is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. Dermatophyte scalp infections caused by T tonsurans produce fungal spores that may occur within the hair shaft (endothrix) or with fungal elements external to the hair shaft (exothrix) such as M canis. Microsporum canis usually fluoresces an apple green color on Wood lamp examination because of the location of the spores.

Key clinical features

Tinea capitis has a variety of clinical presentations: • broken hairs that appear as black dots on the scalp • diffuse scale mimicking seborrheic dermatitis • well-demarcated annular plaques • exudate and tenderness caused by inflammation • scalp pruritus • occipital scalp lymphadenopathy. Worth noting Tinea capitis impacts all patient groups, not just Black patients. In the United States, Black and Hispanic children are most commonly affected.4 Due to a tendency to have dry hair and hair breakage, those with more tightly coiled, textured hair may routinely apply oil and/or grease to the scalp; however, the application of heavy emollients, oils, and grease to camouflage scale contributes to falsenegative fungal cultures of the scalp if applied within 1 week of the fungal culture, which may delay diagnosis. If tinea capitis is suspected, occipital lymphadenopathy on physical examination should prompt treatment for tinea capitis, even without a fungal culture.5 Health disparity highlight A risk factor for tinea capitis is crowded living environments. Some families may live in crowded environments due to economic and housing disparities. This close contact increases the risk for conditions such as tinea capitis.6 Treatment delays may occur due to some cultural practices of applying oils and grease to the hair and scalp, camouflaging the clinical signs of tinea capitis.

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management [published online July 12, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi:10.1111/jdv.15088

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study [published online April 19, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2522

- Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

- Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

- Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015 [published online January 20, 2020]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi:10.1111 /pde.14092

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria [published online April 16, 2008]. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management [published online July 12, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2264-2274. doi:10.1111/jdv.15088

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study [published online April 19, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966-973. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2522

- Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Tinea capitis: focus on African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S120-S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120793

- Alvarez MS, Silverberg NB. Tinea capitis. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:246-255.

- Nguyen CV, Collier S, Merten AH, et al. Tinea capitis: a singleinstitution retrospective review from 2010 to 2015 [published online January 20, 2020]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:305-310. doi:10.1111 /pde.14092

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA. Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria [published online April 16, 2008]. Mycoses. 2008;51:536-541. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01507.x

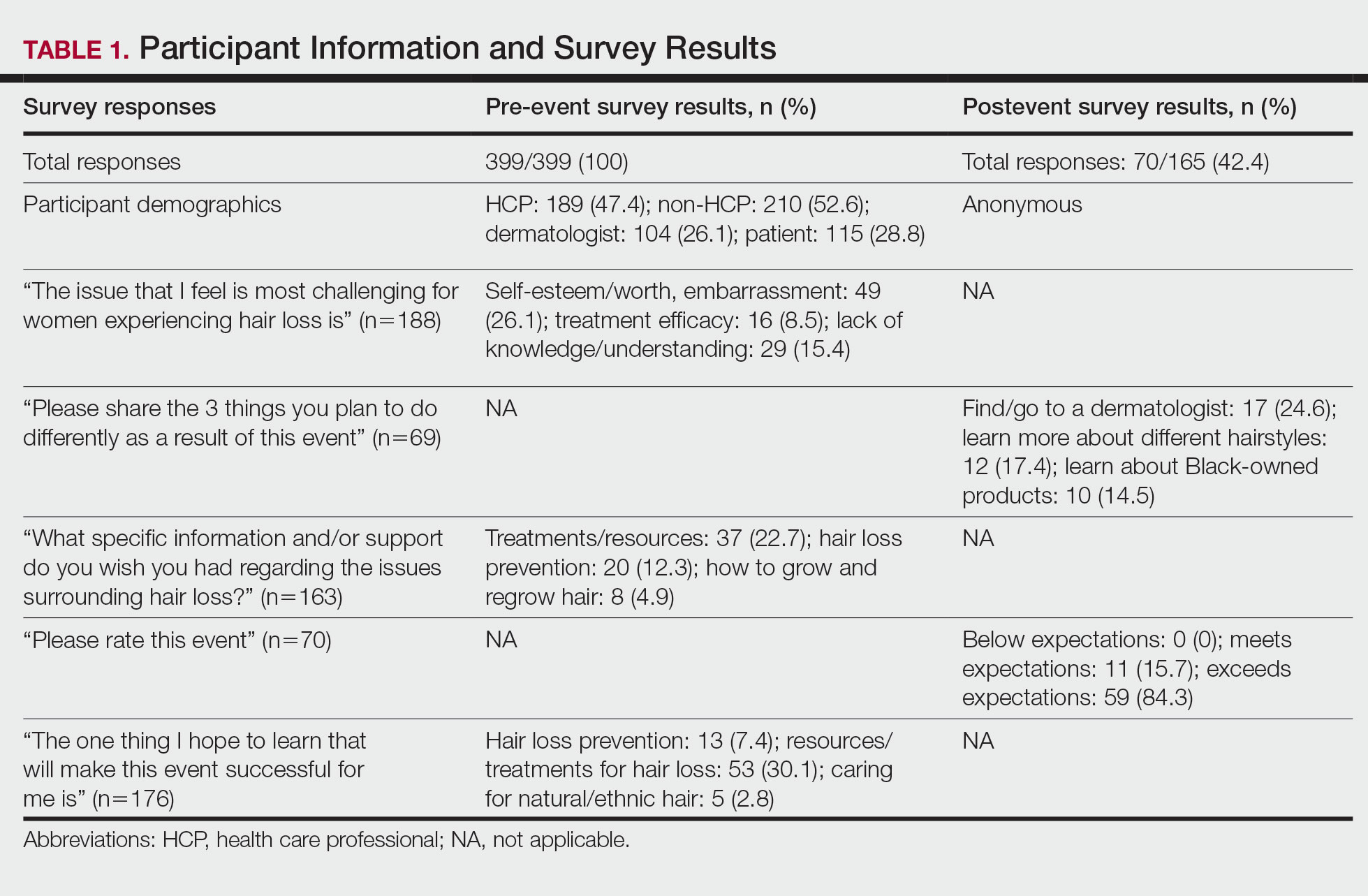

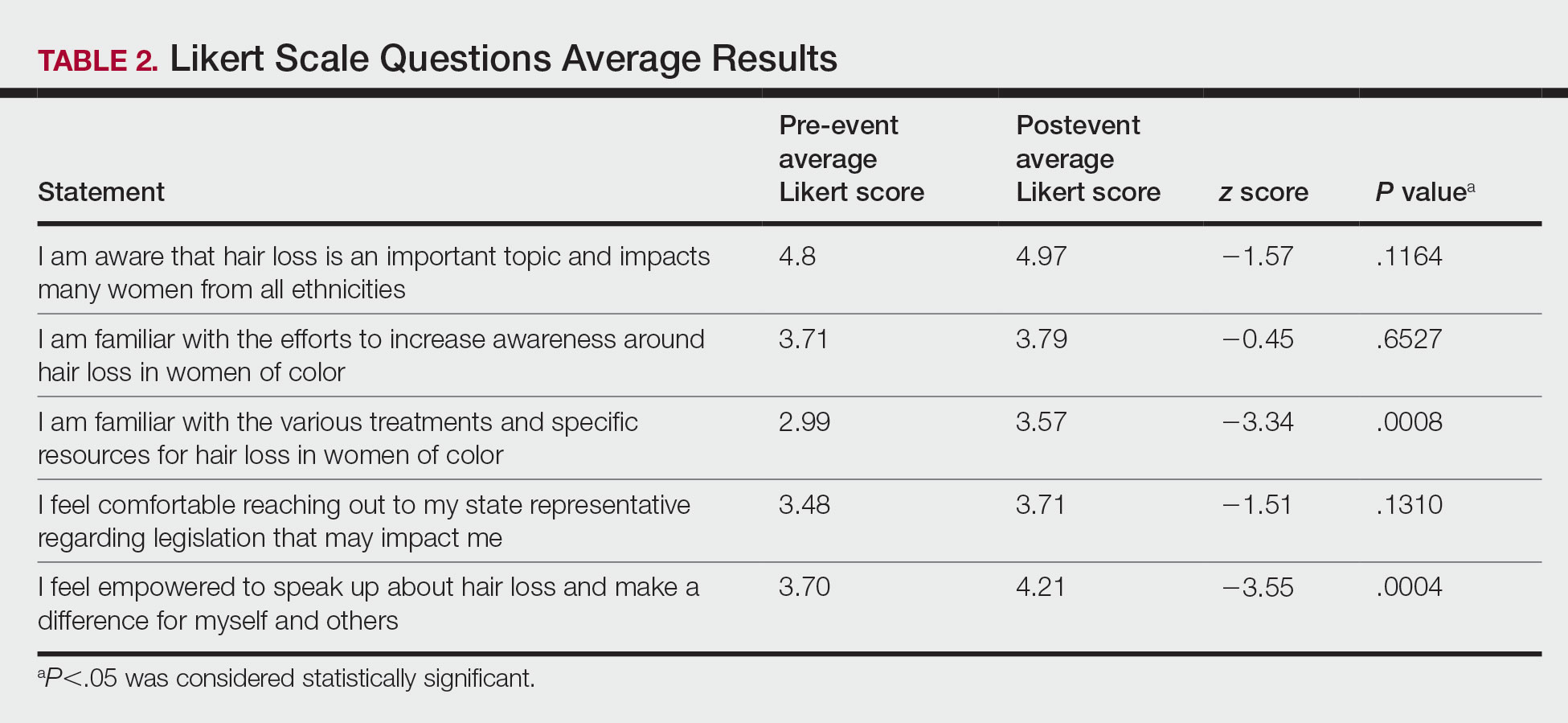

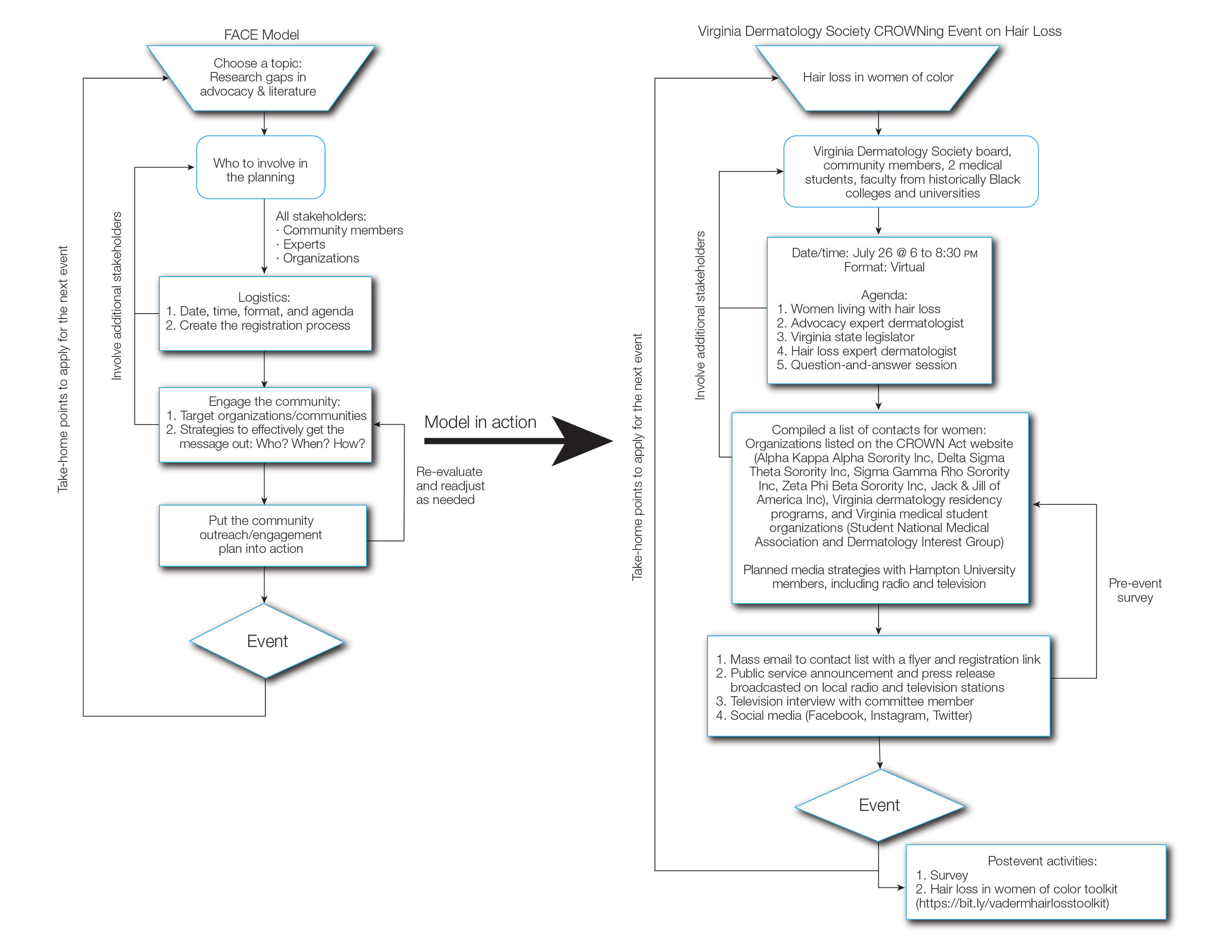

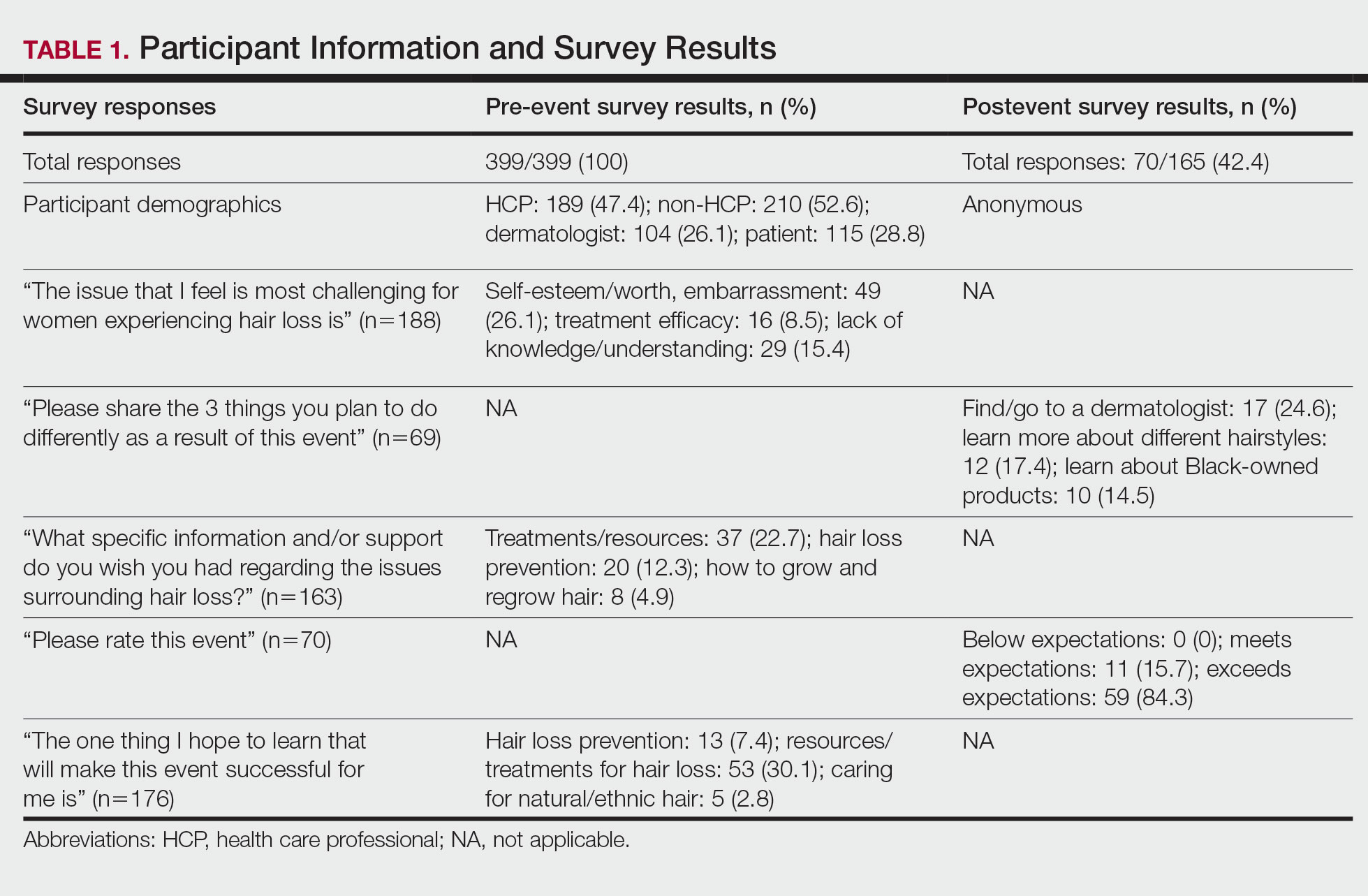

The CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color: A Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) Survey Analysis

Hair loss is a primary reason why women with skin of color seek dermatologic care.1-3 In addition to physical disfigurement, patients with hair loss are more likely to report feelings of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem compared to the general population.4 There is a critical gap in advocacy efforts and educational information intended for women with skin of color. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has 6 main public health programs (https://www.aad.org/public/public-health) and 8 stated advocacy priorities (https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities) but none of them focus on outreach to minority communities.

Historically, hair in patients with skin of color also has been a systemic tangible target for race-based discrimination. The Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act was passed to protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles in schools and workplaces.5 Health care providers play an important role in advocating for their patients, but studies have shown that barriers to effective advocacy include a lack of knowledge, resources, or time.6-8 Virtual advocacy events improve participants’ understanding and interest in community engagement and advocacy.6,7 With the mission to engage, educate, and empower women with skin of color and the dermatologists who treat them, the Virginia Dermatology Society hosted the virtual CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color in July 2021. We believe that this event, as well as this column, can serve as a template to improve advocacy and educational efforts for additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations. Survey data were collected and analyzed to establish a baseline of awareness and understanding of hair loss in women with skin of color and to evaluate the impact of a virtual event on participants’ empowerment and familiarity with resources for this population.

Methods

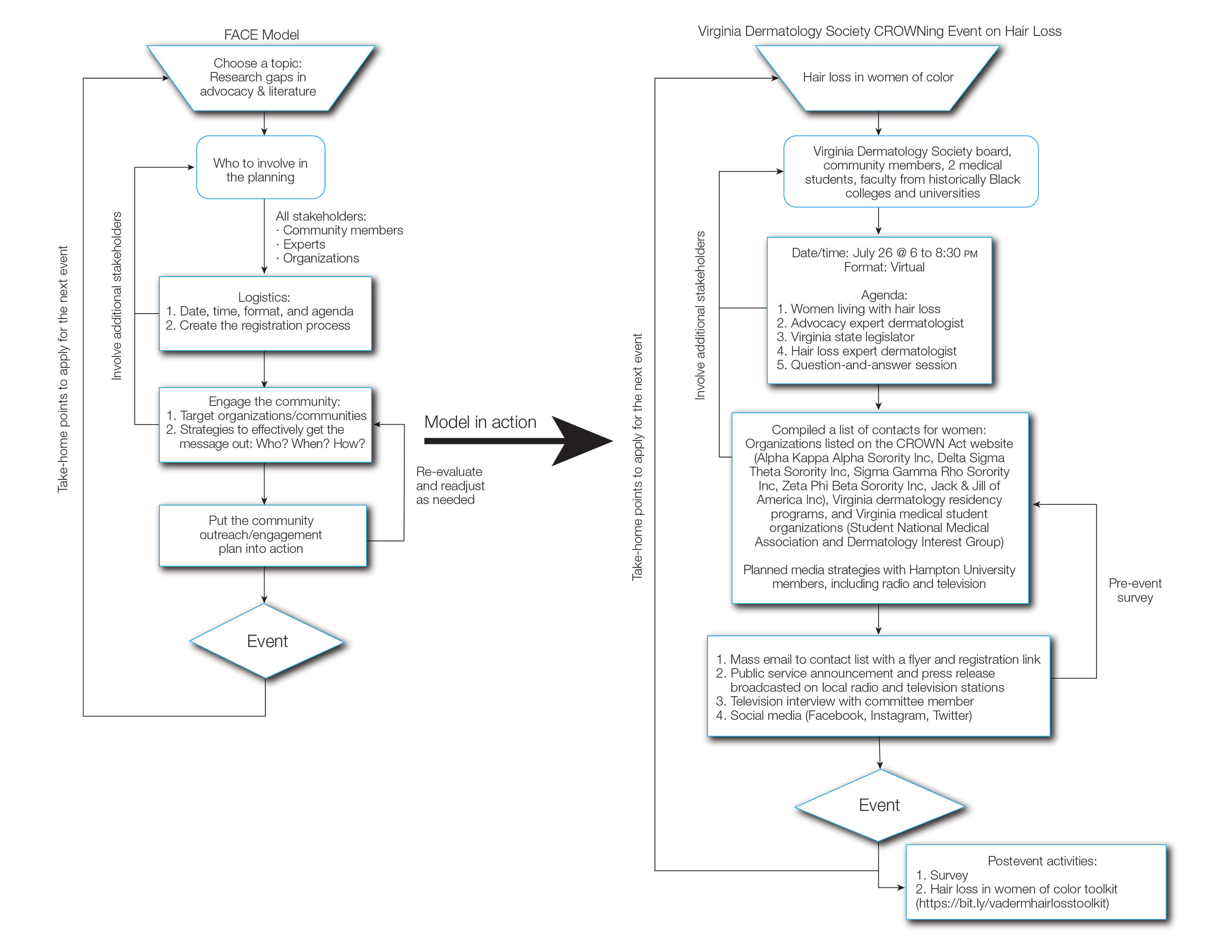

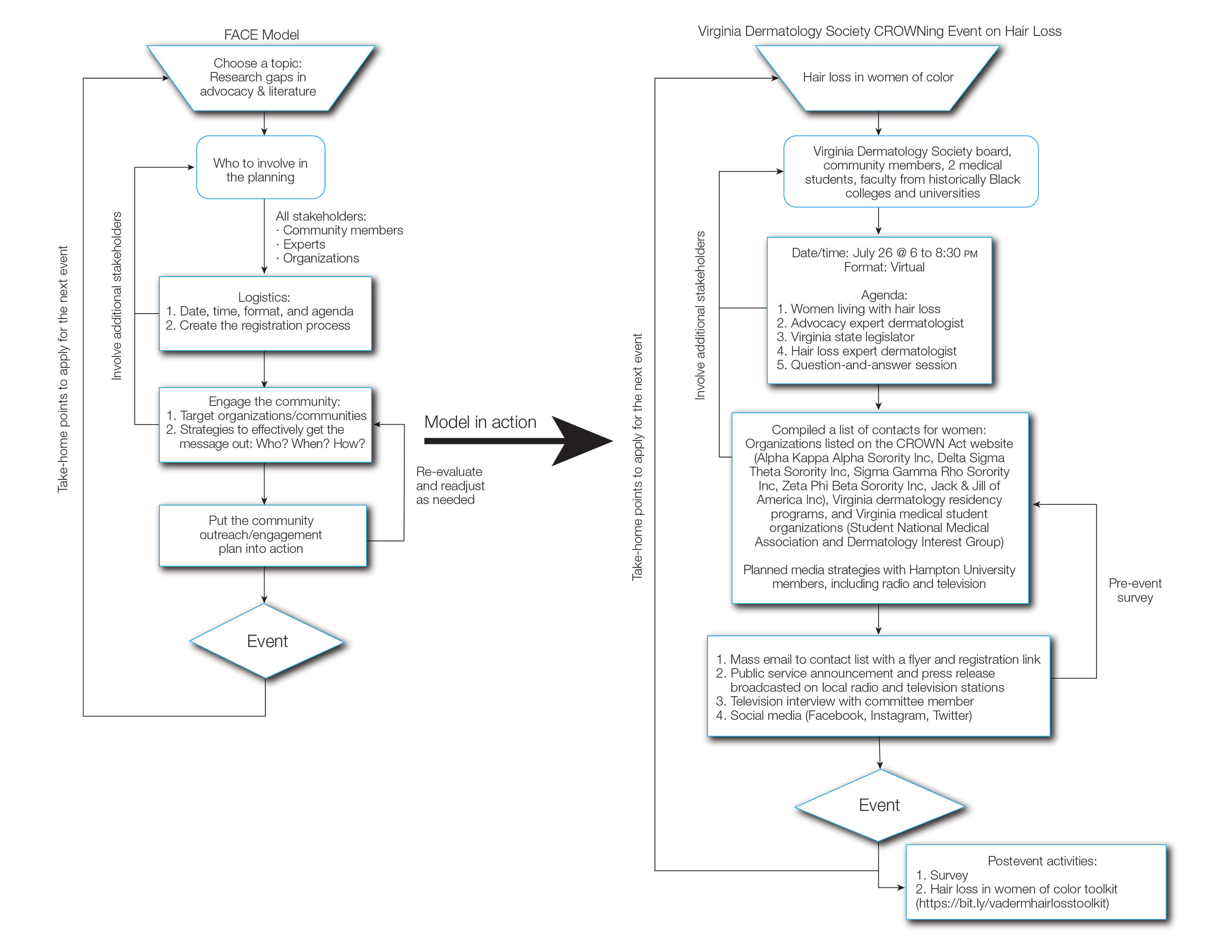

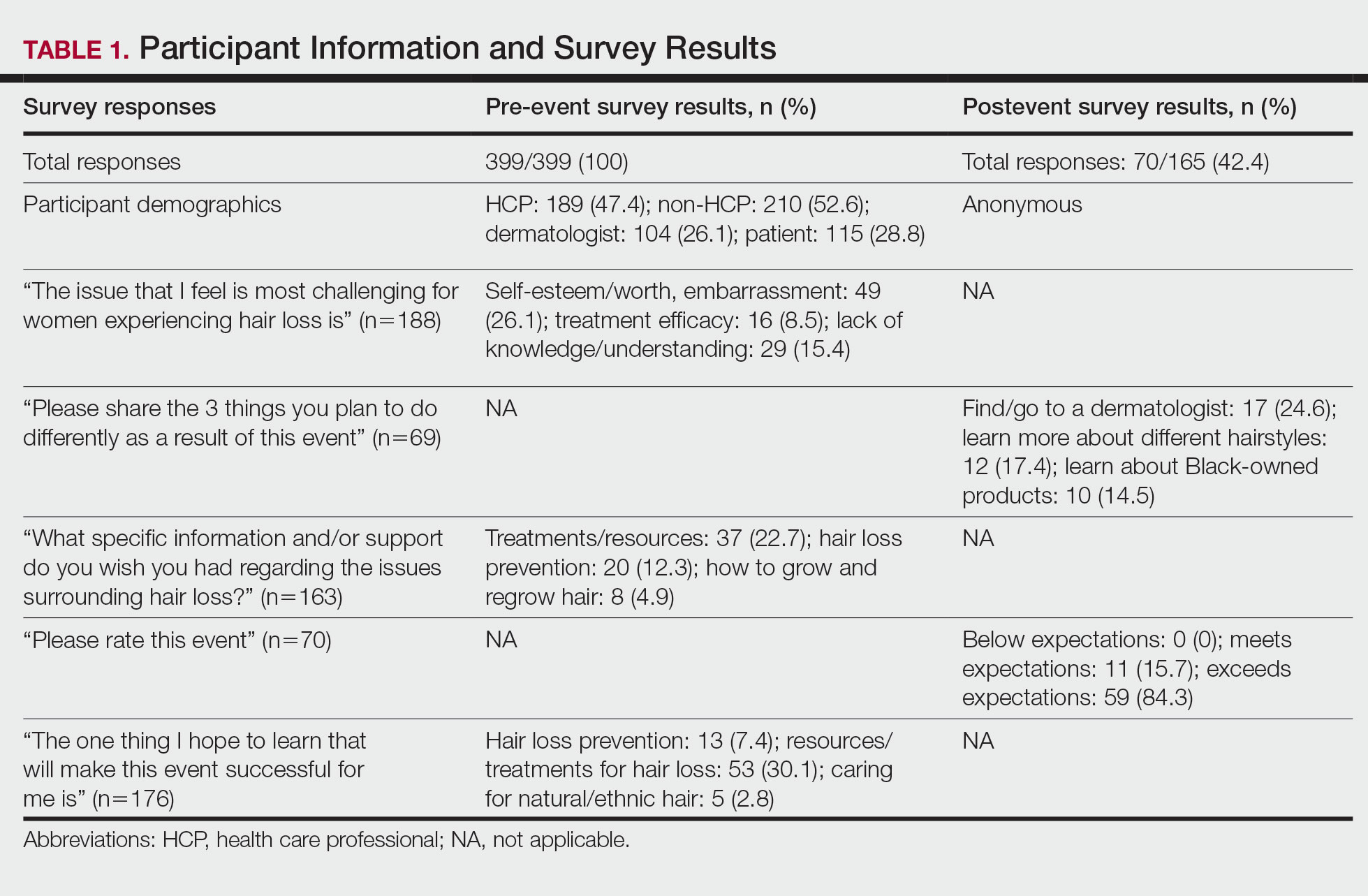

The Virginia Dermatology Society organized a virtual event focused on hair loss and practical political advocacy for women with skin of color. As members of the Virginia Dermatology Society and as part of the planning and execution of this event, the authors engaged relevant stakeholder organizations and collaborated with faculty at a local historically Black university to create a targeted, culturally sensitive communication strategy known as the Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) model (Figure). The agenda included presentations by 2 patients of color living with a hair loss disorder, a dermatologist with experience in advocacy, a Virginia state legislator, and a dermatologic hair loss expert, followed by a final question-and-answer session.

We created pre- and postevent Likert scale surveys assessing participant attitudes, knowledge, and awareness surrounding hair loss that were distributed electronically to all 399 registrants before and after the event, respectively. The responses were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Based on preliminary pre-event survey data, we created a resource toolkit (https://bit.ly/vadermhairlosstoolkit) for distribution to both patients and physicians. The toolkit included articles about evaluating, diagnosing, and treating different types of hair loss that would be beneficial for dermatologists, as well as informational articles, online resources, and videos that would be helpful to patients.

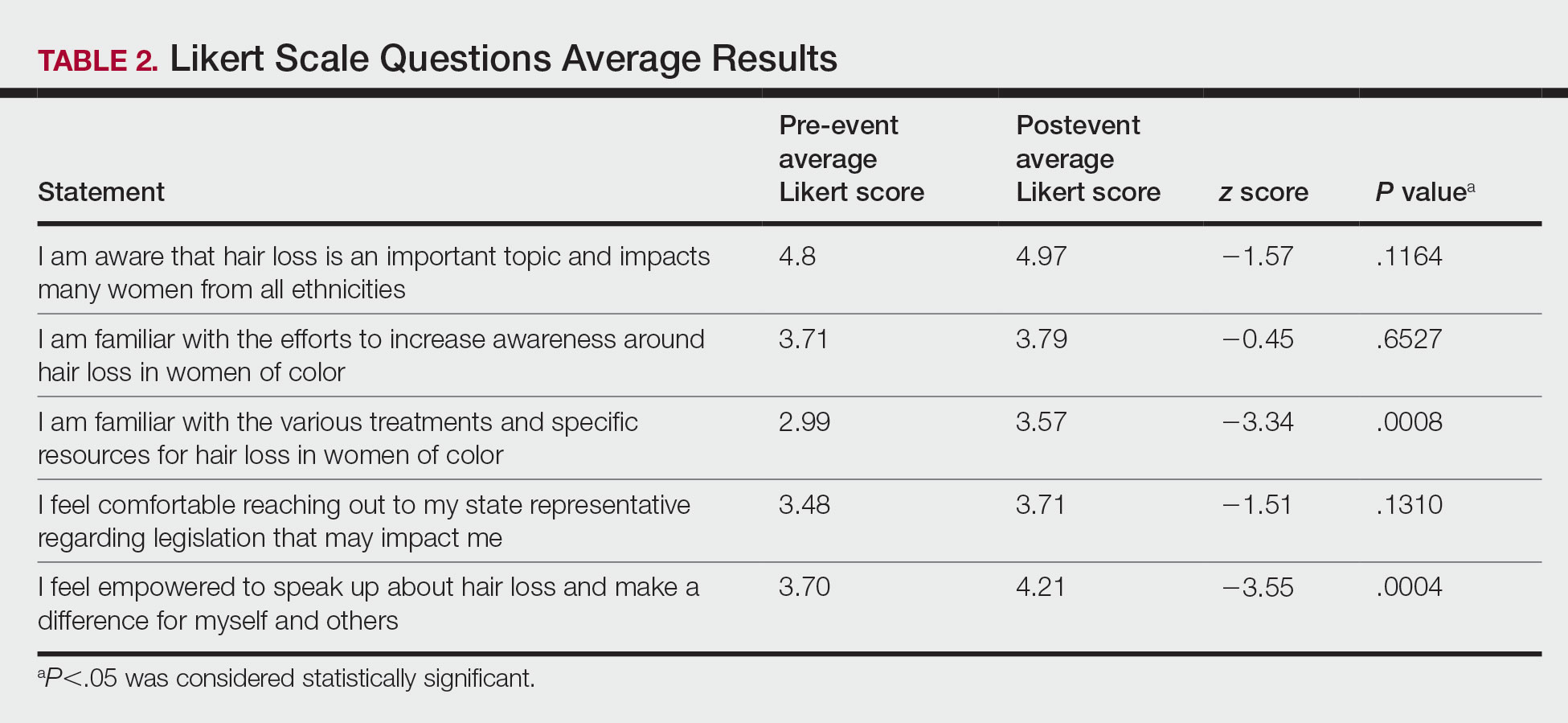

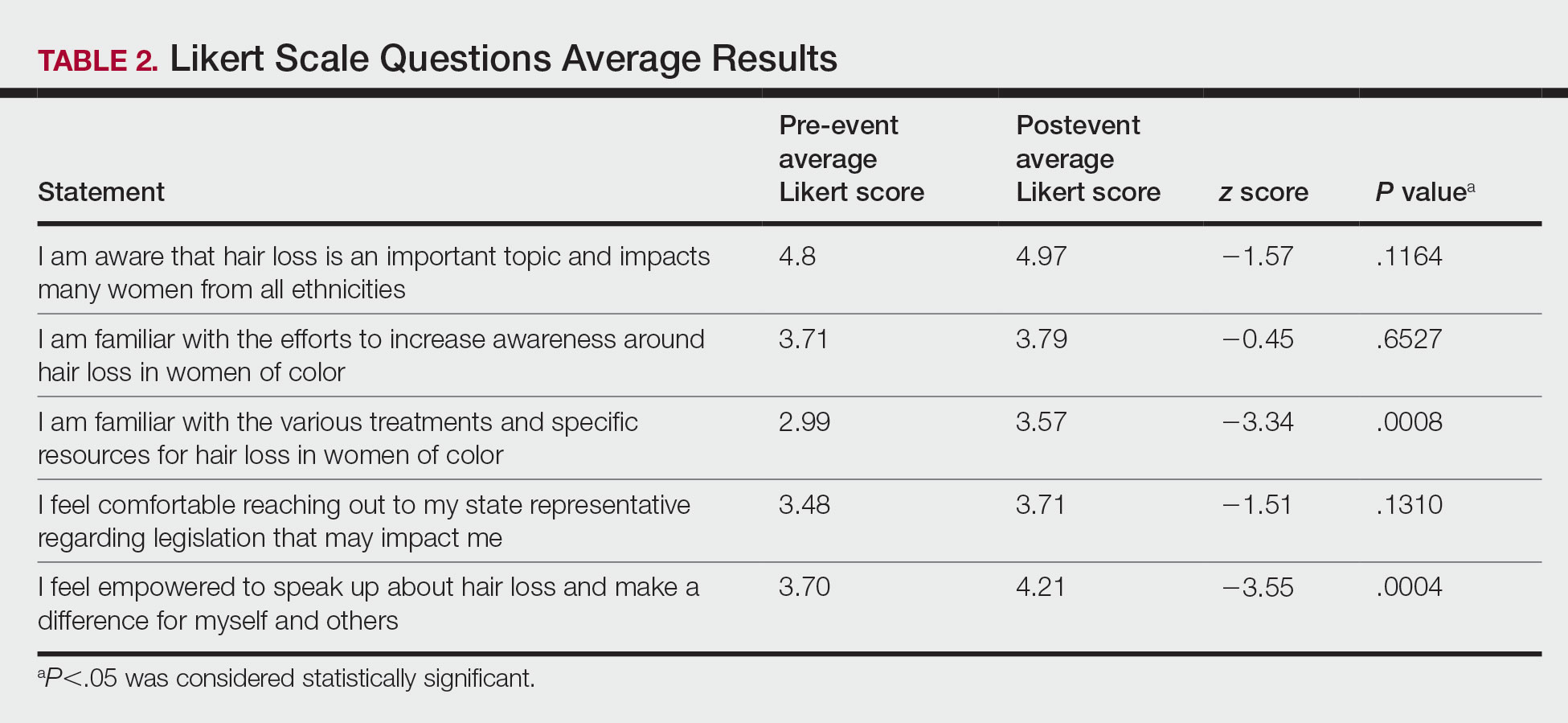

Of the 399 registrants, 165 (41.4%) attended the live virtual event. The postevent survey was completed by 70 (42.4%) participants and showed that familiarity with resources and treatments (z=−3.34, P=.0008) and feelings of empowerment (z=−3.55, P=.0004) significantly increased from before the event (Table 2). Participants indicated that the event exceeded (84.3%) or met (15.7%) their expectations.

Comment

Hair Loss Is Prevalent in Skin of Color Patients—Alopecia is the fourth most common reason women with skin of color seek care from a dermatologist, accounting for 8.3% of all visits in a study of 1412 patient visits; however, it was not among the leading 10 diagnoses made during visits for White patients.3 Traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia occur more commonly in Black women,9 many of whom do not feel their dermatologists understand hair in this population.10,11 Lack of skin of color education in medical school and dermatology residency programs has been reported and must be improved to eliminate the knowledge gaps, acquire cultural competence, and improve all aspects of care for patients with skin of color.11-14 Our survey results similarly demonstrated that only 66% of board-certified dermatologists reported being familiar with the various and specific resources and treatments for hair loss in women of color. Improved understanding of hair in patients of color is a first step in diagnosing and treating hair loss.15 Expertise of dermatologists in skin of color improves the dermatology experience of patients of color.11

Hair loss is more than a cosmetic issue, and it is essential that it is regarded as such. Patients with hair loss have an increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to the general population and report lower self-esteem, heightened self-consciousness, and loss of confidence.4,9 Historically, the lives of patients of color have been drastically affected by society’s perceptions of their skin color and hairstyle.16

Hair-Based Discrimination in the Workplace—To compound the problem, hair also is a common target of race-based discrimination behind the illusion of “professionalism.” Hair-based discrimination keeps people of color out of professional workplaces; for instance, women of color are more likely to be sent home due to hair appearance than White women.5 The CROWN Act, created in 2019, extends statutory protection to hair texture and protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools to protect against discrimination due to race-based hairstyles. The CROWN Act provides an opportunity for dermatologists to support legislation that protects patients of color and the fundamental human right to nondiscrimination. As societal pressure for damaging hair practices such as hot combing or chemical relaxants decreases, patient outcomes will improve.5

How to Support the CROWN Act—There are various meaningful ways for dermatologists to support the CROWN act, including but not limited to signing petitions, sending letters of support to elected representatives, joining the CROWN Coalition, raising awareness and educating the public through social media, vocalizing against hair discrimination in our own workplaces and communities, and asking patients about their experiences with hair discrimination.5 In addition to advocacy, other antiracist actions suggested to improve health equity include creating curricula on racial inequity and increasing diversity in dermatology.16

There are many advocacy and public health campaigns promoted on the AAD website; however, despite the AAD’s formation of the Access to Dermatologic Care Task Force (ATDCTF) with the goal to raise awareness among dermatologists of health disparities affecting marginalized and underserved populations and to develop policies that increase access to care for these groups, there are still critical gaps in advocacy and information.13 This gap in both advocacy and understanding of hair loss conditions in women of color is one reason the CROWNing Event in July 2021 was held, and we believe this event along with this column can serve as a template for addressing additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations.

Dermatologists can play a vital role in advocating for skin and hair needs in all patient populations from the personal or clinical encounter level to population-level policy legislation.5,8 As experts in skin and hair, dermatologists are best prepared to assume leadership in addressing racial health inequities, educating the public, and improving awareness.5,16 Dermatologists must be able to diagnose and manage skin conditions in people of color.12 However, health advocacy should extend beyond changes to health behavior or health interventions and instead address the root causes of systemic issues that drive disparate health outcomes.6 Every dermatologist has a contribution to make; it is time for us to acknowledge that patients’ ailments neither begin nor end at the clinic door.8,16 As dermatologists, we must speak out against the racial inequities and discriminatory policies affecting the lives of patients of color.16

Although the CROWNing event should be considered successful, reflection in hindsight has allowed us to find ways to improve the impact of future events, including incorporating more lay members of the respective community in the planning process, allocating more time during the event programming for questions, and streamlining the distribution of pre-event and postevent surveys to better gauge knowledge retention among participants and gain crucial feedback for future event planning.

How to Use the FACE Model—We believe that the FACE model (Figure) can help providers engage lay members of the community with additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized and underserved populations. We recommend that future organizers engage stakeholders early during the design, planning, and implementation phases to ensure that the community’s most pressing needs are addressed. Dermatologists possess the knowledge and influence to serve as powerful advocates and champions for health equity. As physicians on the front lines of dermatologic health, we are uniquely positioned to engage and partner with patients through educational and advocacy events such as ours. Similarly, informed and empowered patients can advocate for policies and be proponents for greater research funding.5 We call on the AAD and other dermatologic organizations to expand community outreach and advocacy efforts to include underserved and underrepresented populations.

Acknowledgments—The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the faculty at Hampton University (Hampton, Virginia)—specifically Ms. B. DáVida Plummer, MA—for assistance with communication strategies, including organizing the radio and television announcements and proofreading the public service announcements. We also would like to thank other CROWNing Event Planning Committee members, including Natalia Mendoza, MD (Newport News, Virginia); Farhaad Riyaz, MD (Gainesville, Virginia); Deborah Elder, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia); and David Rowe, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia), as well as Sandra Ring, MS, CCLS, CNP (Chicago, Illinois), from the AAD and the various speakers at the event, including the 2 patients; Victoria Barbosa, MD, MPH, MBA (Chicago, Illinois); Avery LaChance, MD, MPH (Boston, Massachusetts); and Senator Lionell Spruill Sr (Chesapeake, Virginia). We acknowledge Marieke K. Jones, PhD, at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), for her statistical expertise.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(suppl 1):S21-S37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.006

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Jamerson TA, Aguh C. An approach to patients with alopecia. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:599-610. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.002

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Tran A, Gohara M. Community engagement matters: a call for greater advocacy in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:189-190. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.008

- Yu Z, Moustafa D, Kwak R, et al. Engaging in advocacy during medical training: assessing the impact of a virtual COVID-19-focused state advocacy day [published online January 13, 2021]. Postgrad Med J. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139362

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:63-67. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, et al. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1129-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2063

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963

- Dlova NC, Salkey KS, Callender VD, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: new insights and a call for action. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S54-S56. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2017.01.004

- Smith RJ, Oliver BU. Advocating for Black lives—a call to dermatologists to dismantle institutionalized racism and address racial health inequities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:155-156. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4392

Hair loss is a primary reason why women with skin of color seek dermatologic care.1-3 In addition to physical disfigurement, patients with hair loss are more likely to report feelings of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem compared to the general population.4 There is a critical gap in advocacy efforts and educational information intended for women with skin of color. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has 6 main public health programs (https://www.aad.org/public/public-health) and 8 stated advocacy priorities (https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities) but none of them focus on outreach to minority communities.

Historically, hair in patients with skin of color also has been a systemic tangible target for race-based discrimination. The Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act was passed to protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles in schools and workplaces.5 Health care providers play an important role in advocating for their patients, but studies have shown that barriers to effective advocacy include a lack of knowledge, resources, or time.6-8 Virtual advocacy events improve participants’ understanding and interest in community engagement and advocacy.6,7 With the mission to engage, educate, and empower women with skin of color and the dermatologists who treat them, the Virginia Dermatology Society hosted the virtual CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color in July 2021. We believe that this event, as well as this column, can serve as a template to improve advocacy and educational efforts for additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations. Survey data were collected and analyzed to establish a baseline of awareness and understanding of hair loss in women with skin of color and to evaluate the impact of a virtual event on participants’ empowerment and familiarity with resources for this population.

Methods

The Virginia Dermatology Society organized a virtual event focused on hair loss and practical political advocacy for women with skin of color. As members of the Virginia Dermatology Society and as part of the planning and execution of this event, the authors engaged relevant stakeholder organizations and collaborated with faculty at a local historically Black university to create a targeted, culturally sensitive communication strategy known as the Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) model (Figure). The agenda included presentations by 2 patients of color living with a hair loss disorder, a dermatologist with experience in advocacy, a Virginia state legislator, and a dermatologic hair loss expert, followed by a final question-and-answer session.

We created pre- and postevent Likert scale surveys assessing participant attitudes, knowledge, and awareness surrounding hair loss that were distributed electronically to all 399 registrants before and after the event, respectively. The responses were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Based on preliminary pre-event survey data, we created a resource toolkit (https://bit.ly/vadermhairlosstoolkit) for distribution to both patients and physicians. The toolkit included articles about evaluating, diagnosing, and treating different types of hair loss that would be beneficial for dermatologists, as well as informational articles, online resources, and videos that would be helpful to patients.

Of the 399 registrants, 165 (41.4%) attended the live virtual event. The postevent survey was completed by 70 (42.4%) participants and showed that familiarity with resources and treatments (z=−3.34, P=.0008) and feelings of empowerment (z=−3.55, P=.0004) significantly increased from before the event (Table 2). Participants indicated that the event exceeded (84.3%) or met (15.7%) their expectations.

Comment

Hair Loss Is Prevalent in Skin of Color Patients—Alopecia is the fourth most common reason women with skin of color seek care from a dermatologist, accounting for 8.3% of all visits in a study of 1412 patient visits; however, it was not among the leading 10 diagnoses made during visits for White patients.3 Traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia occur more commonly in Black women,9 many of whom do not feel their dermatologists understand hair in this population.10,11 Lack of skin of color education in medical school and dermatology residency programs has been reported and must be improved to eliminate the knowledge gaps, acquire cultural competence, and improve all aspects of care for patients with skin of color.11-14 Our survey results similarly demonstrated that only 66% of board-certified dermatologists reported being familiar with the various and specific resources and treatments for hair loss in women of color. Improved understanding of hair in patients of color is a first step in diagnosing and treating hair loss.15 Expertise of dermatologists in skin of color improves the dermatology experience of patients of color.11

Hair loss is more than a cosmetic issue, and it is essential that it is regarded as such. Patients with hair loss have an increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to the general population and report lower self-esteem, heightened self-consciousness, and loss of confidence.4,9 Historically, the lives of patients of color have been drastically affected by society’s perceptions of their skin color and hairstyle.16

Hair-Based Discrimination in the Workplace—To compound the problem, hair also is a common target of race-based discrimination behind the illusion of “professionalism.” Hair-based discrimination keeps people of color out of professional workplaces; for instance, women of color are more likely to be sent home due to hair appearance than White women.5 The CROWN Act, created in 2019, extends statutory protection to hair texture and protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools to protect against discrimination due to race-based hairstyles. The CROWN Act provides an opportunity for dermatologists to support legislation that protects patients of color and the fundamental human right to nondiscrimination. As societal pressure for damaging hair practices such as hot combing or chemical relaxants decreases, patient outcomes will improve.5

How to Support the CROWN Act—There are various meaningful ways for dermatologists to support the CROWN act, including but not limited to signing petitions, sending letters of support to elected representatives, joining the CROWN Coalition, raising awareness and educating the public through social media, vocalizing against hair discrimination in our own workplaces and communities, and asking patients about their experiences with hair discrimination.5 In addition to advocacy, other antiracist actions suggested to improve health equity include creating curricula on racial inequity and increasing diversity in dermatology.16

There are many advocacy and public health campaigns promoted on the AAD website; however, despite the AAD’s formation of the Access to Dermatologic Care Task Force (ATDCTF) with the goal to raise awareness among dermatologists of health disparities affecting marginalized and underserved populations and to develop policies that increase access to care for these groups, there are still critical gaps in advocacy and information.13 This gap in both advocacy and understanding of hair loss conditions in women of color is one reason the CROWNing Event in July 2021 was held, and we believe this event along with this column can serve as a template for addressing additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations.

Dermatologists can play a vital role in advocating for skin and hair needs in all patient populations from the personal or clinical encounter level to population-level policy legislation.5,8 As experts in skin and hair, dermatologists are best prepared to assume leadership in addressing racial health inequities, educating the public, and improving awareness.5,16 Dermatologists must be able to diagnose and manage skin conditions in people of color.12 However, health advocacy should extend beyond changes to health behavior or health interventions and instead address the root causes of systemic issues that drive disparate health outcomes.6 Every dermatologist has a contribution to make; it is time for us to acknowledge that patients’ ailments neither begin nor end at the clinic door.8,16 As dermatologists, we must speak out against the racial inequities and discriminatory policies affecting the lives of patients of color.16

Although the CROWNing event should be considered successful, reflection in hindsight has allowed us to find ways to improve the impact of future events, including incorporating more lay members of the respective community in the planning process, allocating more time during the event programming for questions, and streamlining the distribution of pre-event and postevent surveys to better gauge knowledge retention among participants and gain crucial feedback for future event planning.

How to Use the FACE Model—We believe that the FACE model (Figure) can help providers engage lay members of the community with additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized and underserved populations. We recommend that future organizers engage stakeholders early during the design, planning, and implementation phases to ensure that the community’s most pressing needs are addressed. Dermatologists possess the knowledge and influence to serve as powerful advocates and champions for health equity. As physicians on the front lines of dermatologic health, we are uniquely positioned to engage and partner with patients through educational and advocacy events such as ours. Similarly, informed and empowered patients can advocate for policies and be proponents for greater research funding.5 We call on the AAD and other dermatologic organizations to expand community outreach and advocacy efforts to include underserved and underrepresented populations.

Acknowledgments—The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the faculty at Hampton University (Hampton, Virginia)—specifically Ms. B. DáVida Plummer, MA—for assistance with communication strategies, including organizing the radio and television announcements and proofreading the public service announcements. We also would like to thank other CROWNing Event Planning Committee members, including Natalia Mendoza, MD (Newport News, Virginia); Farhaad Riyaz, MD (Gainesville, Virginia); Deborah Elder, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia); and David Rowe, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia), as well as Sandra Ring, MS, CCLS, CNP (Chicago, Illinois), from the AAD and the various speakers at the event, including the 2 patients; Victoria Barbosa, MD, MPH, MBA (Chicago, Illinois); Avery LaChance, MD, MPH (Boston, Massachusetts); and Senator Lionell Spruill Sr (Chesapeake, Virginia). We acknowledge Marieke K. Jones, PhD, at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), for her statistical expertise.

Hair loss is a primary reason why women with skin of color seek dermatologic care.1-3 In addition to physical disfigurement, patients with hair loss are more likely to report feelings of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem compared to the general population.4 There is a critical gap in advocacy efforts and educational information intended for women with skin of color. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has 6 main public health programs (https://www.aad.org/public/public-health) and 8 stated advocacy priorities (https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities) but none of them focus on outreach to minority communities.

Historically, hair in patients with skin of color also has been a systemic tangible target for race-based discrimination. The Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act was passed to protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles in schools and workplaces.5 Health care providers play an important role in advocating for their patients, but studies have shown that barriers to effective advocacy include a lack of knowledge, resources, or time.6-8 Virtual advocacy events improve participants’ understanding and interest in community engagement and advocacy.6,7 With the mission to engage, educate, and empower women with skin of color and the dermatologists who treat them, the Virginia Dermatology Society hosted the virtual CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color in July 2021. We believe that this event, as well as this column, can serve as a template to improve advocacy and educational efforts for additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations. Survey data were collected and analyzed to establish a baseline of awareness and understanding of hair loss in women with skin of color and to evaluate the impact of a virtual event on participants’ empowerment and familiarity with resources for this population.

Methods

The Virginia Dermatology Society organized a virtual event focused on hair loss and practical political advocacy for women with skin of color. As members of the Virginia Dermatology Society and as part of the planning and execution of this event, the authors engaged relevant stakeholder organizations and collaborated with faculty at a local historically Black university to create a targeted, culturally sensitive communication strategy known as the Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) model (Figure). The agenda included presentations by 2 patients of color living with a hair loss disorder, a dermatologist with experience in advocacy, a Virginia state legislator, and a dermatologic hair loss expert, followed by a final question-and-answer session.

We created pre- and postevent Likert scale surveys assessing participant attitudes, knowledge, and awareness surrounding hair loss that were distributed electronically to all 399 registrants before and after the event, respectively. The responses were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Based on preliminary pre-event survey data, we created a resource toolkit (https://bit.ly/vadermhairlosstoolkit) for distribution to both patients and physicians. The toolkit included articles about evaluating, diagnosing, and treating different types of hair loss that would be beneficial for dermatologists, as well as informational articles, online resources, and videos that would be helpful to patients.

Of the 399 registrants, 165 (41.4%) attended the live virtual event. The postevent survey was completed by 70 (42.4%) participants and showed that familiarity with resources and treatments (z=−3.34, P=.0008) and feelings of empowerment (z=−3.55, P=.0004) significantly increased from before the event (Table 2). Participants indicated that the event exceeded (84.3%) or met (15.7%) their expectations.

Comment

Hair Loss Is Prevalent in Skin of Color Patients—Alopecia is the fourth most common reason women with skin of color seek care from a dermatologist, accounting for 8.3% of all visits in a study of 1412 patient visits; however, it was not among the leading 10 diagnoses made during visits for White patients.3 Traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia occur more commonly in Black women,9 many of whom do not feel their dermatologists understand hair in this population.10,11 Lack of skin of color education in medical school and dermatology residency programs has been reported and must be improved to eliminate the knowledge gaps, acquire cultural competence, and improve all aspects of care for patients with skin of color.11-14 Our survey results similarly demonstrated that only 66% of board-certified dermatologists reported being familiar with the various and specific resources and treatments for hair loss in women of color. Improved understanding of hair in patients of color is a first step in diagnosing and treating hair loss.15 Expertise of dermatologists in skin of color improves the dermatology experience of patients of color.11

Hair loss is more than a cosmetic issue, and it is essential that it is regarded as such. Patients with hair loss have an increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to the general population and report lower self-esteem, heightened self-consciousness, and loss of confidence.4,9 Historically, the lives of patients of color have been drastically affected by society’s perceptions of their skin color and hairstyle.16

Hair-Based Discrimination in the Workplace—To compound the problem, hair also is a common target of race-based discrimination behind the illusion of “professionalism.” Hair-based discrimination keeps people of color out of professional workplaces; for instance, women of color are more likely to be sent home due to hair appearance than White women.5 The CROWN Act, created in 2019, extends statutory protection to hair texture and protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools to protect against discrimination due to race-based hairstyles. The CROWN Act provides an opportunity for dermatologists to support legislation that protects patients of color and the fundamental human right to nondiscrimination. As societal pressure for damaging hair practices such as hot combing or chemical relaxants decreases, patient outcomes will improve.5

How to Support the CROWN Act—There are various meaningful ways for dermatologists to support the CROWN act, including but not limited to signing petitions, sending letters of support to elected representatives, joining the CROWN Coalition, raising awareness and educating the public through social media, vocalizing against hair discrimination in our own workplaces and communities, and asking patients about their experiences with hair discrimination.5 In addition to advocacy, other antiracist actions suggested to improve health equity include creating curricula on racial inequity and increasing diversity in dermatology.16

There are many advocacy and public health campaigns promoted on the AAD website; however, despite the AAD’s formation of the Access to Dermatologic Care Task Force (ATDCTF) with the goal to raise awareness among dermatologists of health disparities affecting marginalized and underserved populations and to develop policies that increase access to care for these groups, there are still critical gaps in advocacy and information.13 This gap in both advocacy and understanding of hair loss conditions in women of color is one reason the CROWNing Event in July 2021 was held, and we believe this event along with this column can serve as a template for addressing additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations.

Dermatologists can play a vital role in advocating for skin and hair needs in all patient populations from the personal or clinical encounter level to population-level policy legislation.5,8 As experts in skin and hair, dermatologists are best prepared to assume leadership in addressing racial health inequities, educating the public, and improving awareness.5,16 Dermatologists must be able to diagnose and manage skin conditions in people of color.12 However, health advocacy should extend beyond changes to health behavior or health interventions and instead address the root causes of systemic issues that drive disparate health outcomes.6 Every dermatologist has a contribution to make; it is time for us to acknowledge that patients’ ailments neither begin nor end at the clinic door.8,16 As dermatologists, we must speak out against the racial inequities and discriminatory policies affecting the lives of patients of color.16

Although the CROWNing event should be considered successful, reflection in hindsight has allowed us to find ways to improve the impact of future events, including incorporating more lay members of the respective community in the planning process, allocating more time during the event programming for questions, and streamlining the distribution of pre-event and postevent surveys to better gauge knowledge retention among participants and gain crucial feedback for future event planning.

How to Use the FACE Model—We believe that the FACE model (Figure) can help providers engage lay members of the community with additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized and underserved populations. We recommend that future organizers engage stakeholders early during the design, planning, and implementation phases to ensure that the community’s most pressing needs are addressed. Dermatologists possess the knowledge and influence to serve as powerful advocates and champions for health equity. As physicians on the front lines of dermatologic health, we are uniquely positioned to engage and partner with patients through educational and advocacy events such as ours. Similarly, informed and empowered patients can advocate for policies and be proponents for greater research funding.5 We call on the AAD and other dermatologic organizations to expand community outreach and advocacy efforts to include underserved and underrepresented populations.

Acknowledgments—The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the faculty at Hampton University (Hampton, Virginia)—specifically Ms. B. DáVida Plummer, MA—for assistance with communication strategies, including organizing the radio and television announcements and proofreading the public service announcements. We also would like to thank other CROWNing Event Planning Committee members, including Natalia Mendoza, MD (Newport News, Virginia); Farhaad Riyaz, MD (Gainesville, Virginia); Deborah Elder, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia); and David Rowe, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia), as well as Sandra Ring, MS, CCLS, CNP (Chicago, Illinois), from the AAD and the various speakers at the event, including the 2 patients; Victoria Barbosa, MD, MPH, MBA (Chicago, Illinois); Avery LaChance, MD, MPH (Boston, Massachusetts); and Senator Lionell Spruill Sr (Chesapeake, Virginia). We acknowledge Marieke K. Jones, PhD, at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), for her statistical expertise.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(suppl 1):S21-S37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.006

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Jamerson TA, Aguh C. An approach to patients with alopecia. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:599-610. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.002

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Tran A, Gohara M. Community engagement matters: a call for greater advocacy in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:189-190. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.008

- Yu Z, Moustafa D, Kwak R, et al. Engaging in advocacy during medical training: assessing the impact of a virtual COVID-19-focused state advocacy day [published online January 13, 2021]. Postgrad Med J. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139362

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:63-67. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, et al. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1129-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2063

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963

- Dlova NC, Salkey KS, Callender VD, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: new insights and a call for action. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S54-S56. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2017.01.004

- Smith RJ, Oliver BU. Advocating for Black lives—a call to dermatologists to dismantle institutionalized racism and address racial health inequities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:155-156. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4392

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(suppl 1):S21-S37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.006

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Jamerson TA, Aguh C. An approach to patients with alopecia. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:599-610. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.002

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Tran A, Gohara M. Community engagement matters: a call for greater advocacy in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:189-190. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.008

- Yu Z, Moustafa D, Kwak R, et al. Engaging in advocacy during medical training: assessing the impact of a virtual COVID-19-focused state advocacy day [published online January 13, 2021]. Postgrad Med J. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139362

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:63-67. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, et al. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1129-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2063

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963

- Dlova NC, Salkey KS, Callender VD, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: new insights and a call for action. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S54-S56. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2017.01.004

- Smith RJ, Oliver BU. Advocating for Black lives—a call to dermatologists to dismantle institutionalized racism and address racial health inequities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:155-156. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4392

Practice Points

- Hair loss is associated with low self-esteem in women with skin of color; therefore, it is important to both acknowledge the social and psychological impacts of hair loss in this population and provide educational resources and community events that address patient concerns.

- There is a deficit of dermatology advocacy efforts that address conditions affecting patients with skin of color. Highlighting this disparity is the first step to catalyzing change.

- Dermatologists are responsible for advocating for women with skin of color and for addressing the social issues that impact their quality of life.

- The Framework for Advocacy and Community Efforts (FACE) model is a template for others to use when planning community engagement and advocacy efforts.

Learning Experiences in LGBT Health During Dermatology Residency

Approximately 4.5% of adults within the United States identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community.1 This is an umbrella term inclusive of all individuals identifying as nonheterosexual or noncisgender. Although the LGBT community has increasingly become more recognized and accepted by society over time, health care disparities persist and have been well documented in the literature.2-4 Dermatologists have the potential to greatly impact LGBT health, as many health concerns in this population are cutaneous, such as sun-protection behaviors, side effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming procedures, and cutaneous manifestations of sexually transmitted infections.5-7

An education gap has been demonstrated in both medical students and resident physicians regarding LGBT health and cultural competency. In a large-scale, multi-institutional survey study published in 2015, approximately two-thirds of medical students rated their schools’ LGBT curriculum as fair, poor, or very poor.8 Additional studies have echoed these results and have demonstrated not only the need but the desire for additional training on LGBT issues in medical school.9-11 The Association of American Medical Colleges has begun implementing curricular and institutional changes to fulfill this need.12,13

The LGBT education gap has been shown to extend into residency training. Multiple studies performed within a variety of medical specialties have demonstrated that resident physicians receive insufficient training in LGBT health issues, lack comfort in caring for LGBT patients, and would benefit from dedicated curricula on these topics.14-18 Currently, the 2022 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines related to LGBT health are minimal and nonspecific.19

Ensuring that dermatology trainees are well equipped to manage these issues while providing culturally competent care to LGBT patients is paramount. However, research suggests that dedicated training on these topics likely is insufficient. A survey study of dermatology residency program directors (N=90) revealed that although 81% (72/89) viewed training in LGBT health as either very important or somewhat important, 46% (41/90) of programs did not dedicate any time to this content and 37% (33/90) only dedicated 1 to 2 hours per year.20

To further explore this potential education gap, we surveyed dermatology residents directly to better understand LGBT education within residency training, resident preparedness to care for LGBT patients, and outness/discrimination of LGBT-identifying residents. We believe this study should drive future research on the development and implementation of LGBT-specific curricula in dermatology training programs.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study of dermatology residents in the United States was conducted. The study was deemed exempt from review by The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) institutional review board. Survey responses were collected from October 7, 2020, to November 13, 2020. Qualtrics software was used to create the 20-question survey, which included a combination of categorical, dichotomous, and optional free-text questions related to patient demographics, LGBT training experiences, perceived areas of curriculum improvement, comfort level managing LGBT health issues, and personal experiences. Some questions were adapted from prior surveys.15,21 Validated survey tools used included the 2020 US Census to collect information regarding race and ethnicity, the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory to measure outness regarding sexual orientation, and select questions from the 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges Medical School Graduation Questionnaire regarding discrimination.22-24

The survey was distributed to current allopathic and osteopathic dermatology residents by a variety of methods, including emails to program director and program coordinator listserves. The survey also was posted in the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group on LGBTQ Health October 2020 newsletter, as well as dermatology social media groups, including a messaging forum limited to dermatology residents, a Facebook group open to dermatologists and dermatology residents, and the Facebook group of the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association. Current dermatology residents, including those in combined dermatology and internal medicine programs, were included. Individuals who had been accepted to dermatology training programs but had not yet started were excluded. A follow-up email was sent to the program director listserve approximately 3 weeks after the initial distribution.

Statistical Analysis—The data were analyzed in Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics. Stata software (Stata 15.1, StataCorp) was used to perform a Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test to compare the means of education level and feelings of preparedness.

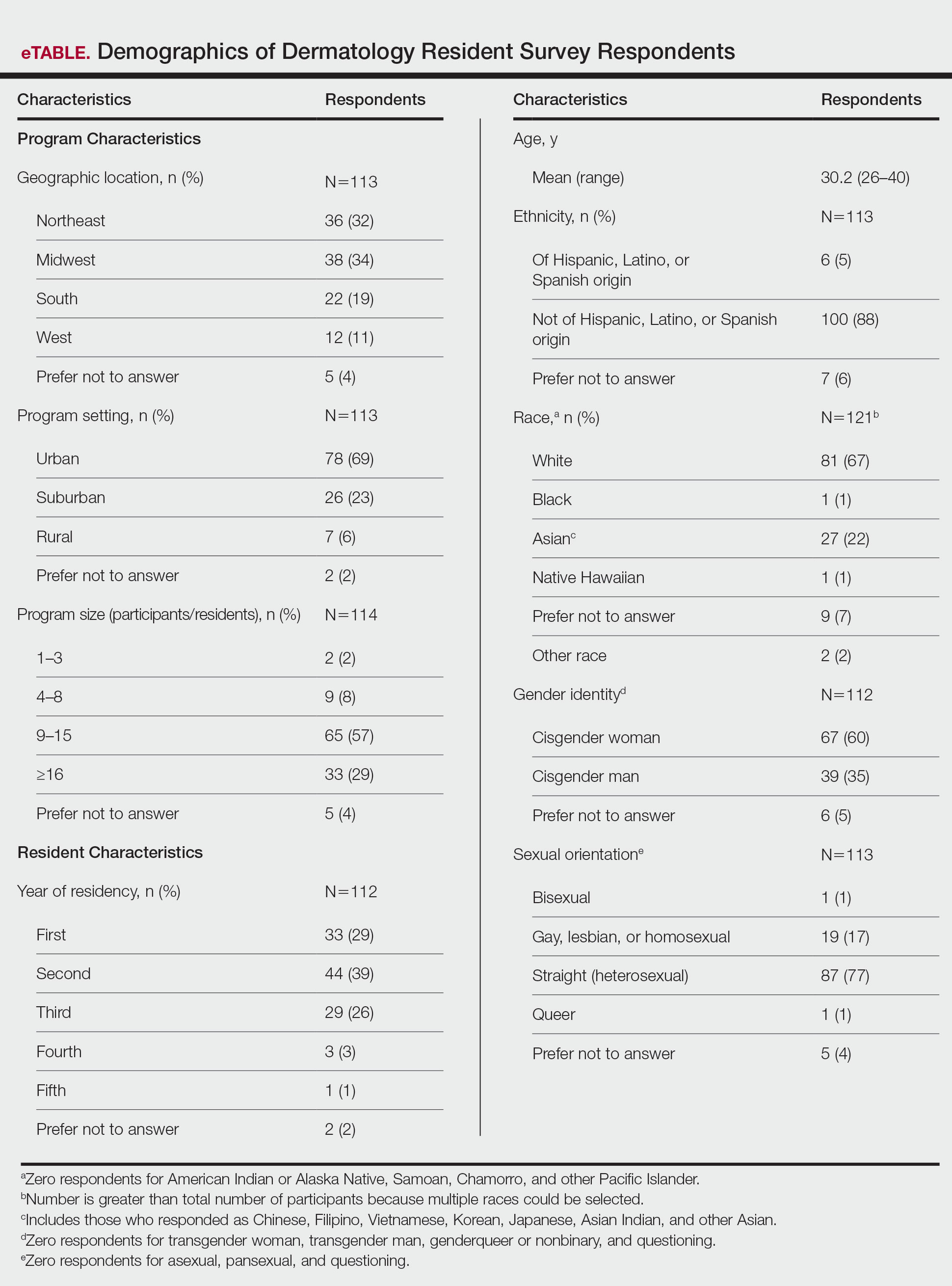

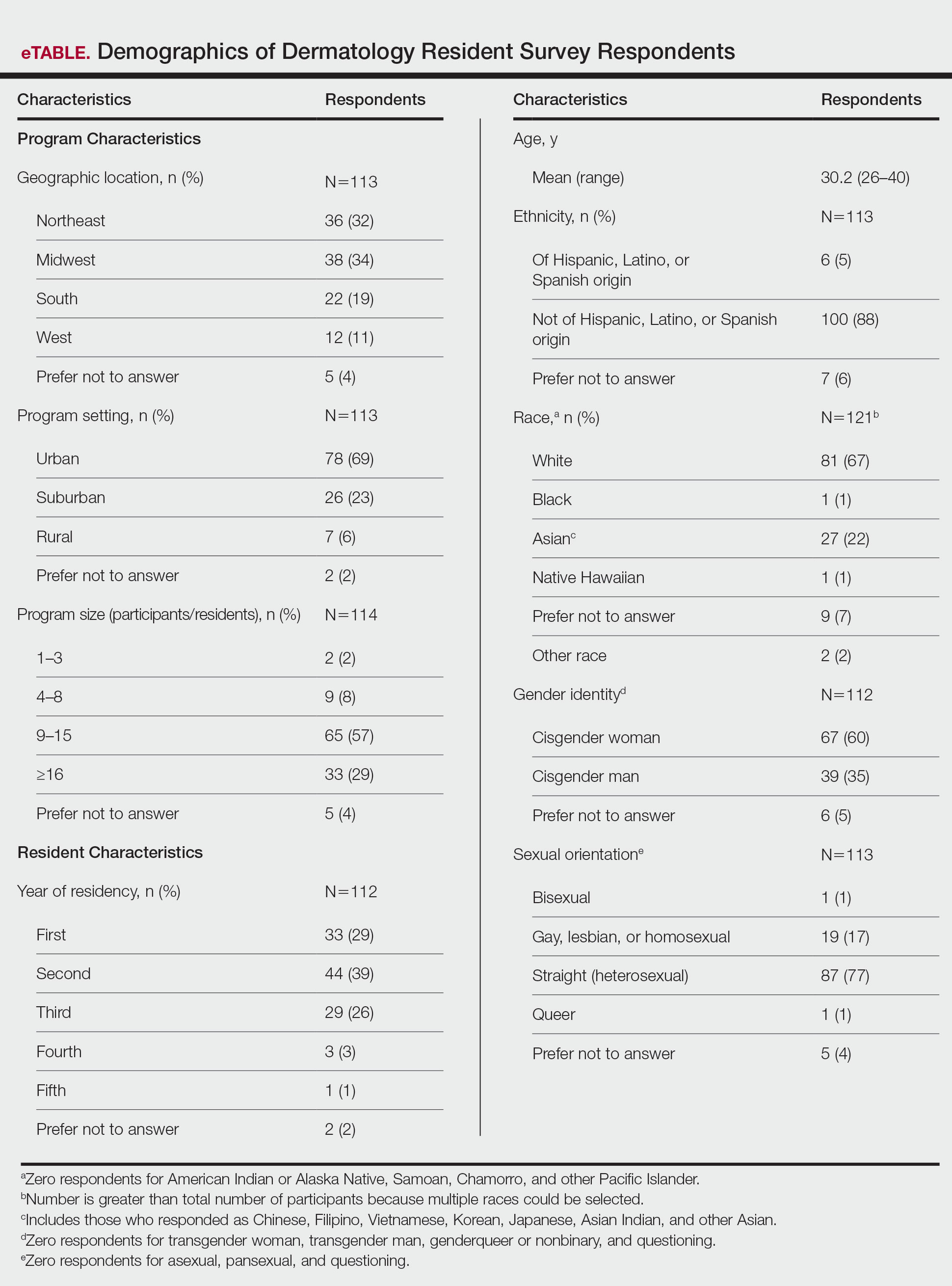

Results

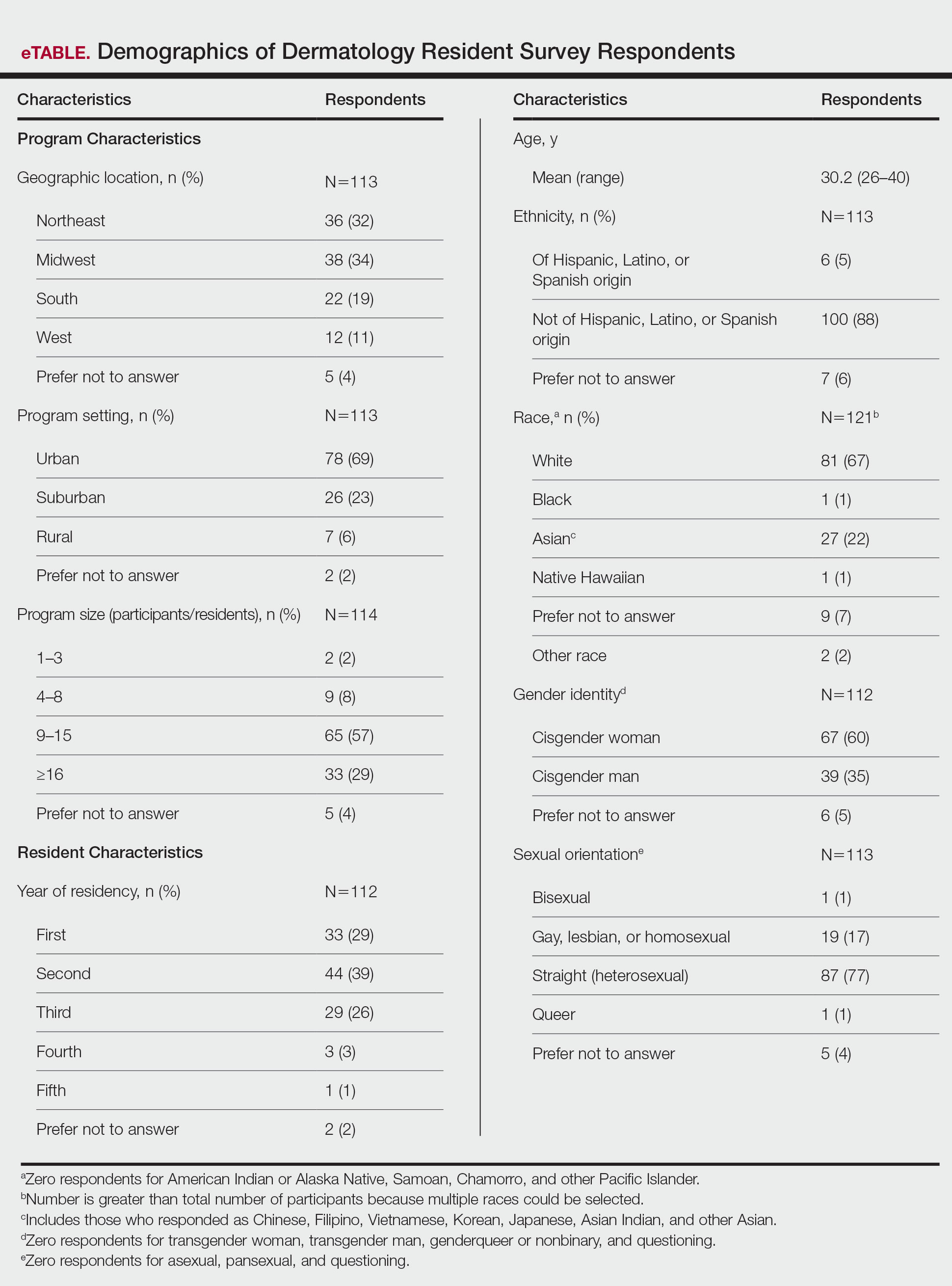

Demographics of Respondents—A total of 126 responses were recorded, 12 of which were blank and were removed from the database. A total of 114 dermatology residents’ responses were collected in Qualtrics and analyzed; 91 completed the entire survey (an 80% completion rate). Based on the 2020-2021 ACGME data listing, there were 1612 dermatology residents in the United States, which is an estimated response rate of 7% (114/1612).25 The eTable outlines the demographics of the survey respondents. Most were cisgender females (60%), followed by cisgender males (35%); the remainder preferred not to answer. Regarding sexual orientation, 77% identified as straight or heterosexual; 17% as gay, lesbian, or homosexual; 1% as queer; and 1% as bisexual. The training programs were in 26 states, the majority of which were in the Midwest (34%) and in urban settings (69%). A wide range of postgraduate levels and residency sizes were represented in the survey.

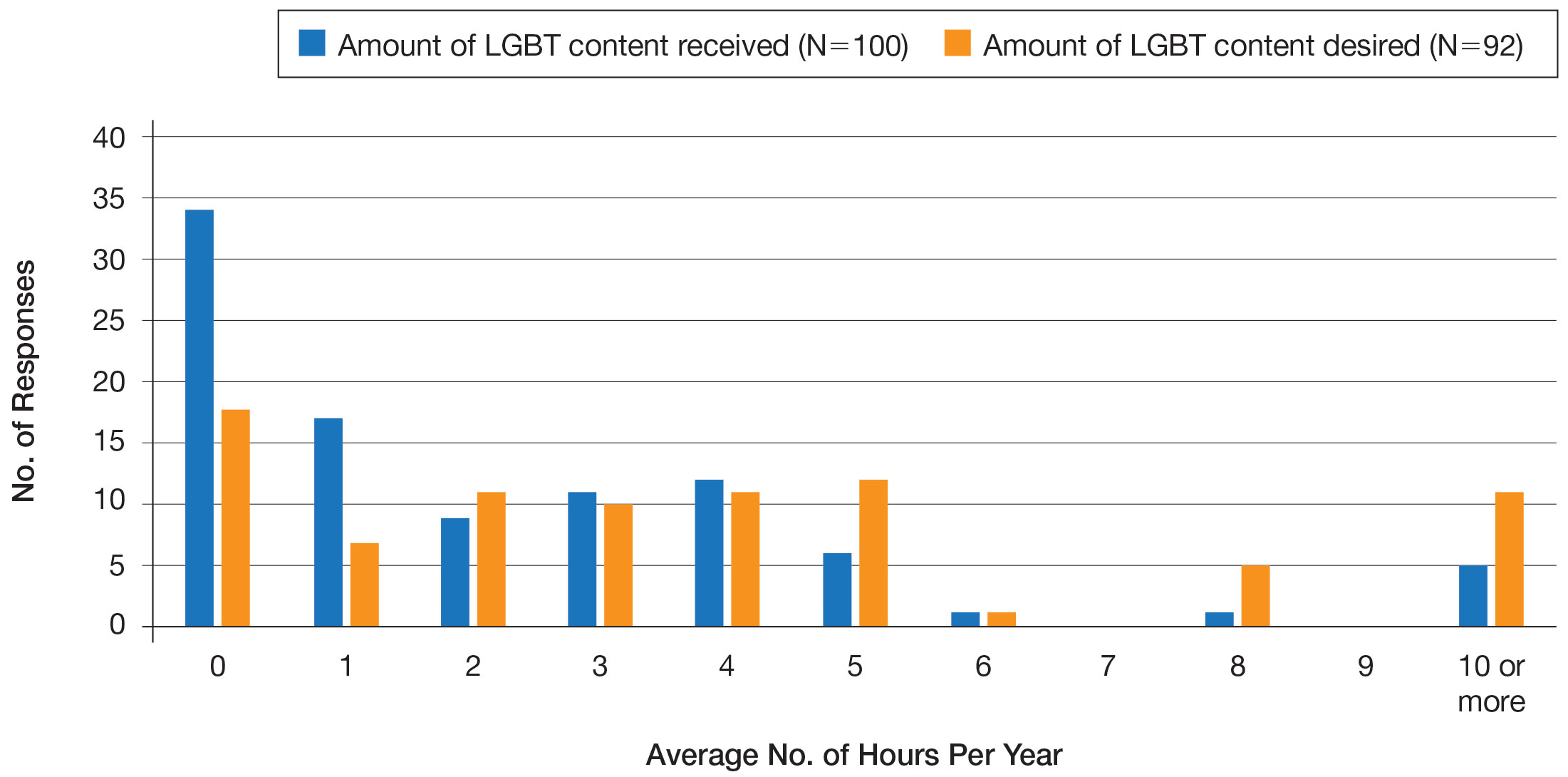

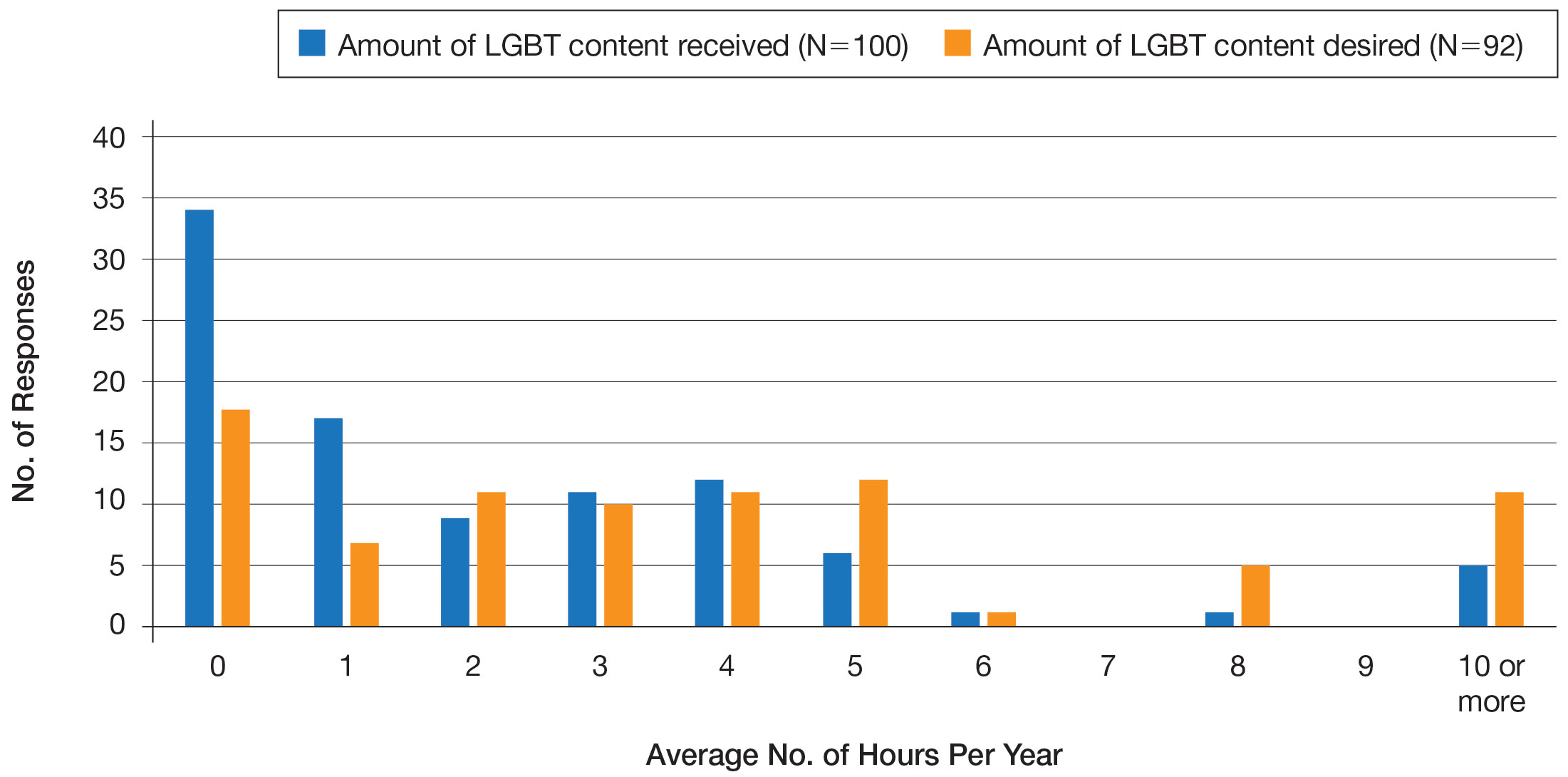

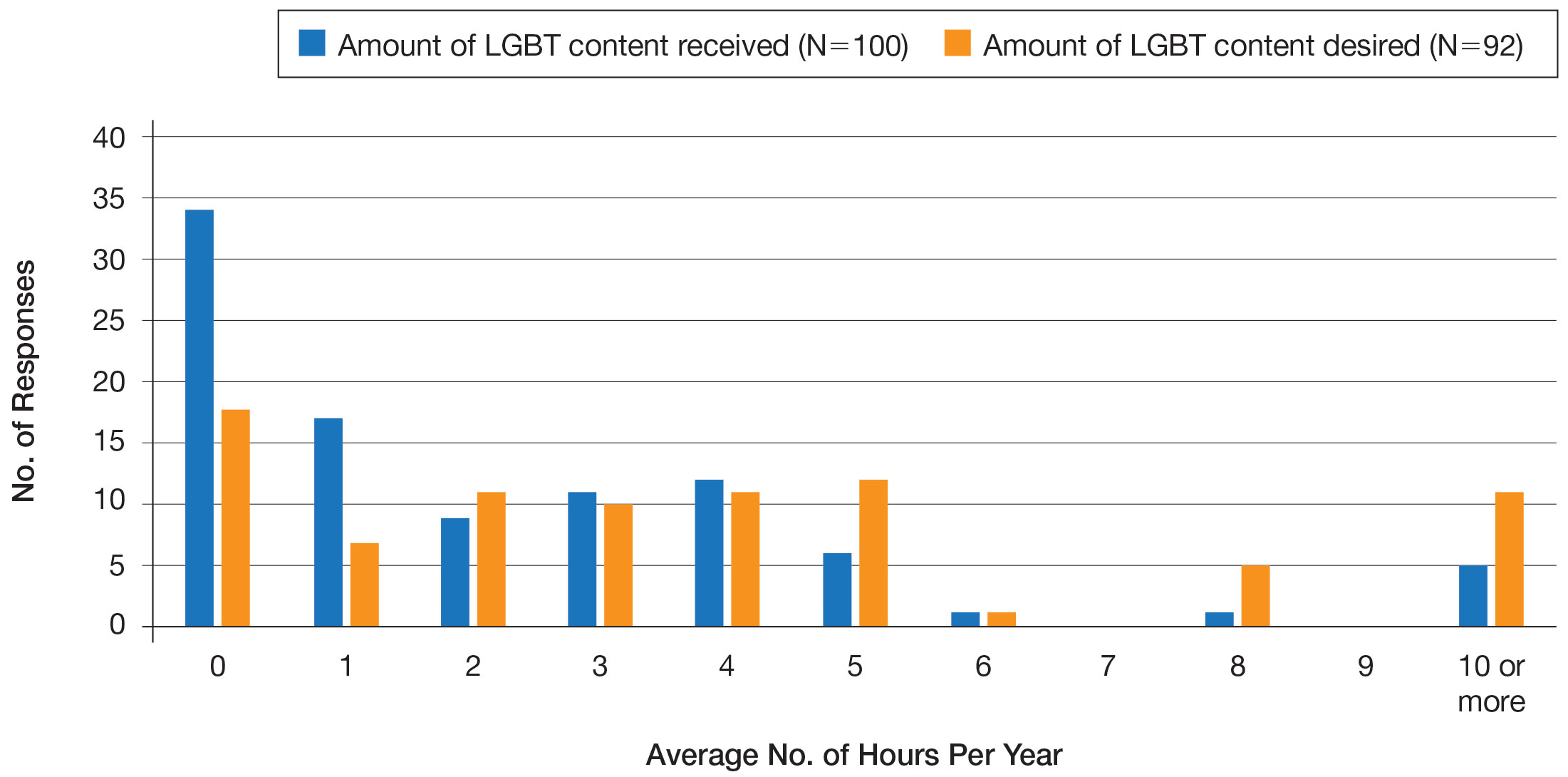

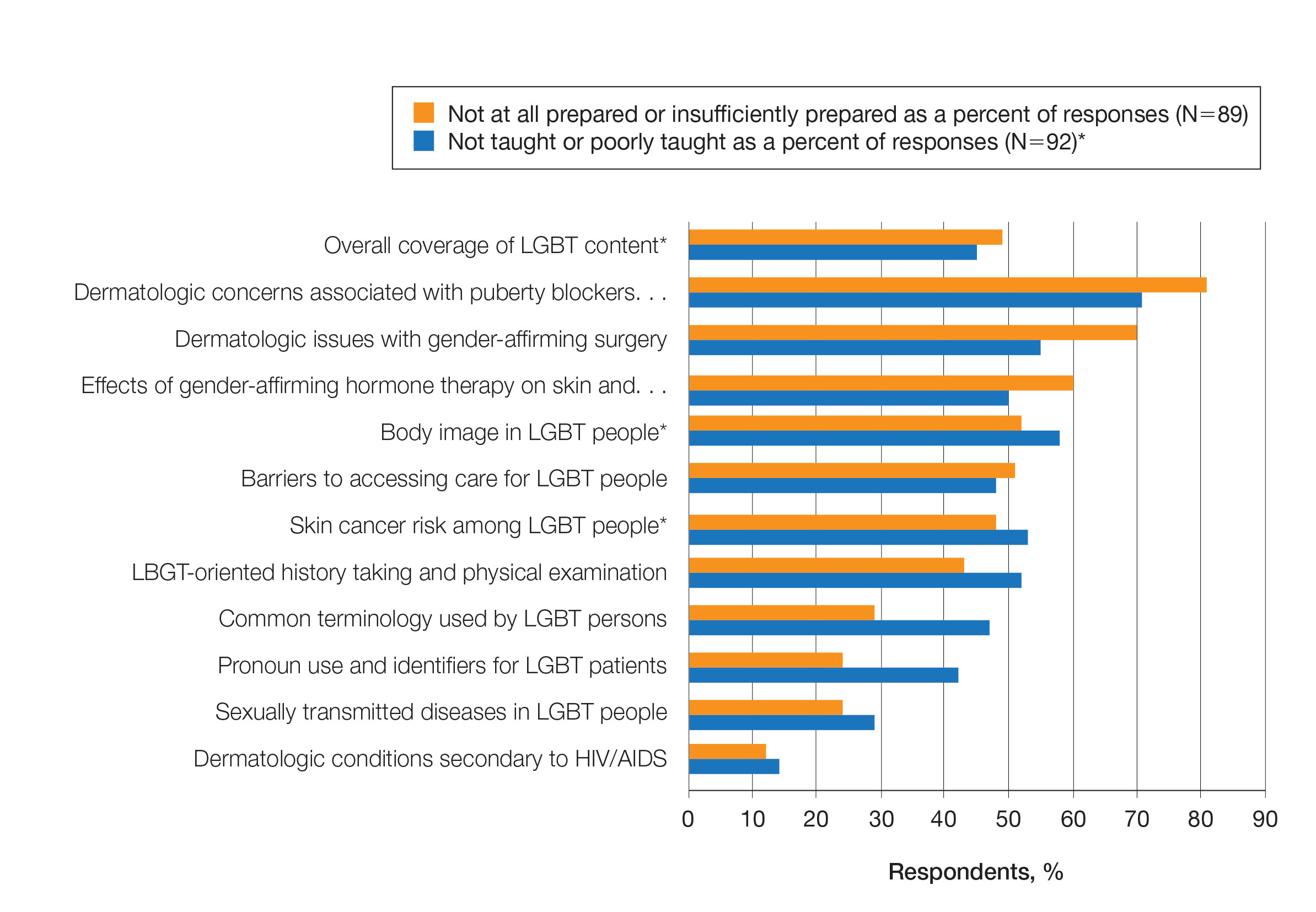

LGBT Education—Fifty-one percent of respondents reported that their programs offer 1 hour or less of LGBT-related curricula per year; 34% reported no time dedicated to this topic. A small portion of residents (5%) reported 10 or more hours of LGBT education per year. Residents also were asked the average number of hours of LGBT education they thought they should receive. The discrepancy between these measures can be visualized in Figure 1. The median hours of education received was 1 hour (IQR, 0–4 hours), whereas the median hours of education desired was 4 hours (IQR, 2–5 hours). The most common and most helpful methods of education reported were clinical experiences with faculty or patients and live lectures.

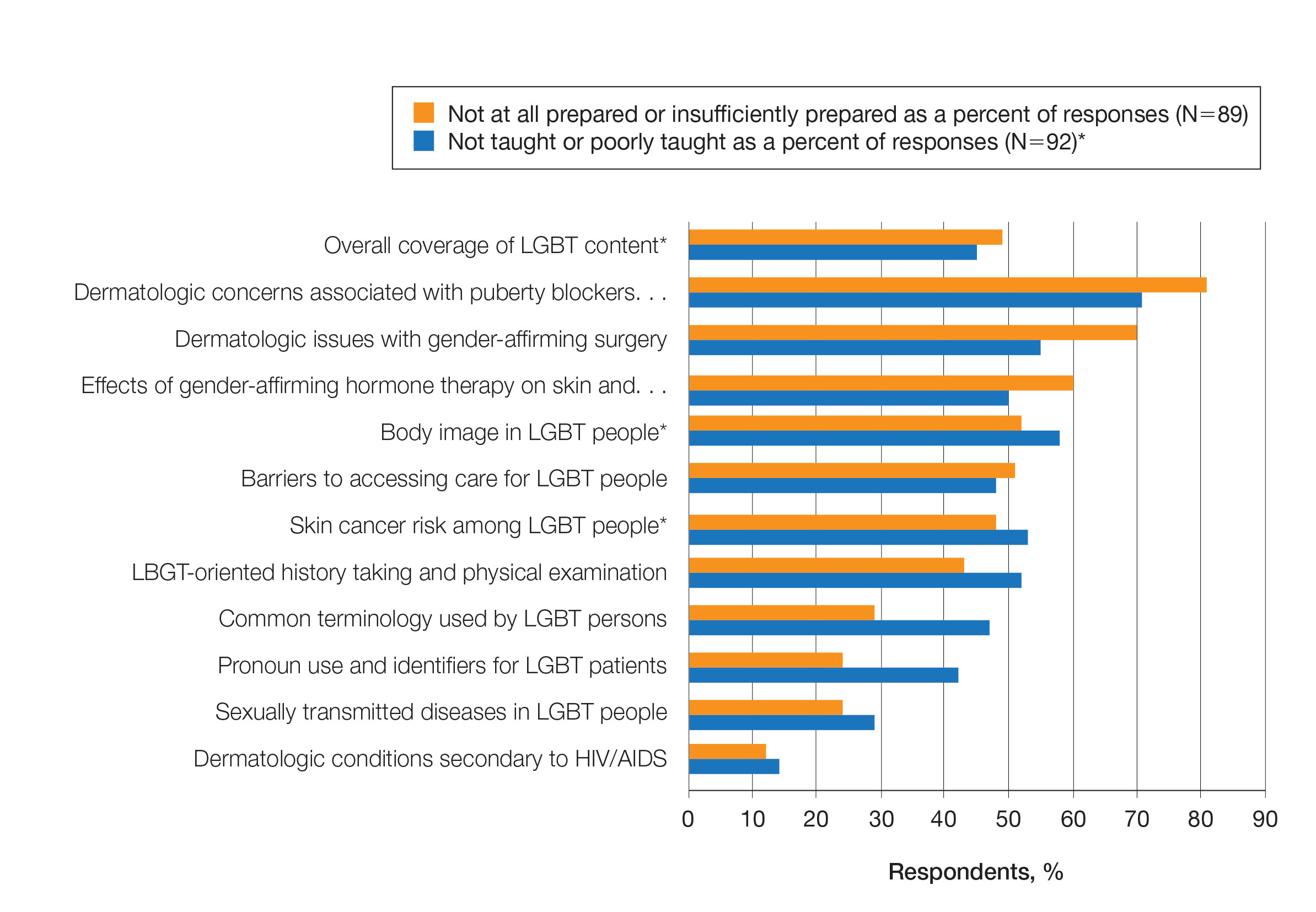

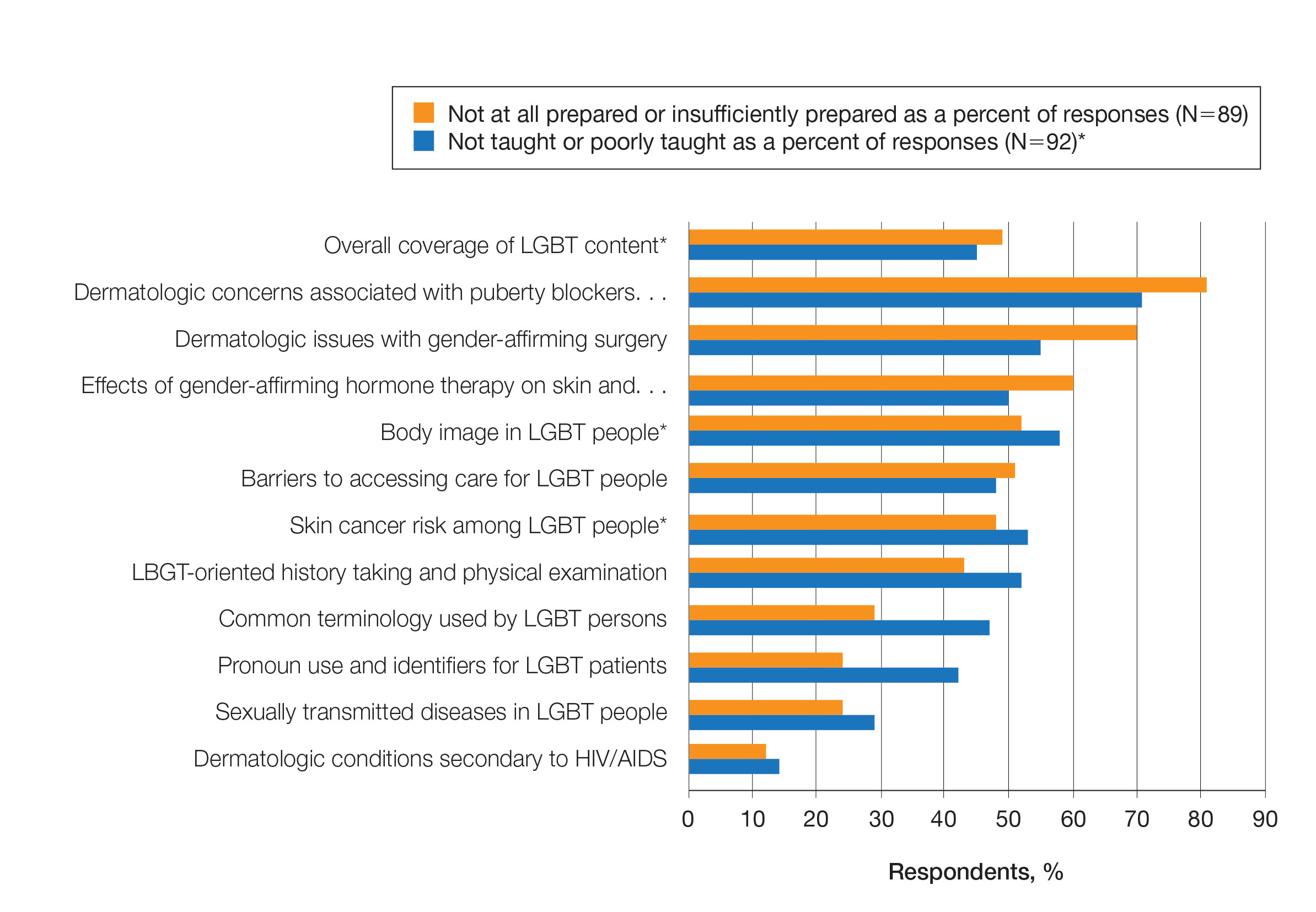

Overall, 45% of survey respondents felt that LGBT topics were covered poorly or not at all in dermatology residency, whereas 26% thought the coverage was good or excellent. The topics that residents were most likely to report receiving good or excellent coverage were dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS (70%) and sexually transmitted diseases in LGBT patients (48%). The topics that were most likely to be reported as not taught or poorly taught included dermatologic concerns associated with puberty blockers (71%), body image (58%), dermatologic concerns associated with gender-affirming surgery (55%), skin cancer risk (53%), taking an LGBT-oriented history and physical examination (52%), and effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the skin (50%). A detailed breakdown of coverage level by topic can be found in Figure 2.

Preparedness to Care for LGBT Patients—Only 68% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable treating LGBT patients. Furthermore, 49% of dermatology residents reported that they feel not at all prepared or insufficiently prepared to provide care to LGBT individuals (Figure 2), and 60% believed that LGBT training needed to be improved at their residency programs.

There was a significant association between reported level of education and feelings of preparedness. A high ranking of provided education was associated with higher levels of feeling prepared to care for LGBT patients (Kruskal-Wallis rank test, P<.001).

Discrimination/Outness—Approximately one-fourth (24%; 4/17) of nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported that they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation in the workplace. One respondent commented that they were less “out” at their residency program due to fear of discrimination. Nearly one-third of the overall group of dermatology residents surveyed (29%; 27/92) reported that they had witnessed inappropriate or discriminatory comments about LGBT persons made by employees or staff at their programs. Most residents surveyed (96%; 88/92) agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians.

There were 18 nonheterosexual dermatologyresidents who completed the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory.23 In general, respondents reported that they were more “out” with friends and family than work peers and were least “out” with work supervisors and strangers.

Comment

Dermatology Residents Desire More Time on LGBT Health—This cross-sectional survey study explored dermatology residents’ educational experiences with LGBT health during residency training. Similar studies have been performed in other specialties, including a study from 2019 surveying emergency medicine residents that demonstrated residents find caring for LGBT patients more challenging.15 Another 2019 study surveying psychiatry residents found that 42.4% (N=99) reported no coverage of LGBT topics.18 Our study is unique in that it surveyed dermatology residents directly regarding this topic. Although most dermatology program directors view LGBT dermatologic health as an important topic, a prior study revealed that many programs are lacking dedicated LGBT educational experiences. The most common barriers reported were insufficient time in the didactic schedule and lack of experienced faculty.20

Our study revealed that dermatology residents overall tend to agree with residents from other specialties and dermatology program directors. Most of the dermatology residents surveyed reported desiring more time per year spent on LGBT health education than they receive, and 60% expressed that LGBT educational experiences need to be improved at their residency programs. Education on and subsequent comfort level with LGBT health issues varied by subtopic, with most residents feeling comfortable dealing with dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and less comfortable with topics such as puberty blockers, gender-affirming surgery and hormone therapy, body image, and skin cancer risk.

Overall, LGBT health training is viewed as important and in need of improvement by both program directors and residents, yet implementation lags at many programs. A small proportion of the represented programs are excelling in this area—just over 5% of respondents reported receiving 10 or more hours of LGBT-relevant education per year, and approximately 26% of residents felt that LGBT coverage was good or excellent at their programs. Our study showed a clear relationship between feelings of preparedness and education level. The lack of LGBT education at some dermatology residency programs translated into a large portion of dermatology residents feeling ill equipped to care for LGBT patients after graduation—nearly 50% of those surveyed reported feeling insufficiently prepared to care for the LGBT community.