User login

Enhanced Care for Pediatric Patients With Generalized Lichen Planus: Diagnosis and Treatment Tips

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory cutaneous disorder. Although it often is characterized by the 6 Ps—pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, and plaques with a predilection for the wrists and ankles—the presentation can vary in morphology and distribution.1-5 With an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population, LP is undoubtedly uncommon.1 Its prevalence in the pediatric population is especially low, with only 2% to 3% of cases manifesting in individuals younger than 20 years.2

Generalized LP (also referred to as eruptive or exanthematous LP) is a rarely reported clinical subtype in which lesions are disseminated or spread rapidly.5 The rarity of generalized LP in children often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, impacting the patient’s quality of life. Thus, there is a need for heightened awareness among clinicians on the variable presentation of LP in the pediatric population. Incorporating a punch biopsy for the diagnosis of LP when lesions manifest as widespread, erythematous to violaceous, flat-topped papules or plaques, along with the addition of an intramuscular (IM) injection in the treatment plan, improves overall patient outcomes.

Tools and Techniques

A detailed physical examination followed by a punch biopsy was critical for the diagnosis of generalized LP in a 7-year-old Black girl. The examination revealed a widespread distribution of dark, violaceous, polygonal, shiny, flat-topped, firm papules coalescing into plaques across the entire body, with a greater predilection for the legs and overlying joints (Figure, A). Some lesions exhibited fine, silver-white, reticular patterns consistent with Wickham striae. Notably, there was no involvement of the scalp, nails, or mucosal surfaces.

The patient had no relevant medical or family history of skin disease and no recent history of illness. She previously was treated by a pediatrician with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, a course of oral cephalexin, and oral cetirizine 10 mg once daily without relief of symptoms.

Although the clinical presentation was consistent with LP, the differential diagnosis included lichen simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and generalized granuloma annulare. To address the need for early recognition of LP in pediatric patients, a punch biopsy of a lesion on the left anterior thigh was performed and showed lichenoid interface dermatitis—a pivotal finding in distinguishing LP from other conditions in the differential.

Given the patient’s age and severity of the LP, a combination of topical and systemic therapies was prescribed—clobetasol cream 0.025% twice daily and 1 injection of 0.5 cc of IM triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL. This regimen was guided by the efficacy of IM injections in providing prompt symptomatic relief, particularly for patients with extensive disease or for those whose condition is refractory to topical treatments.6 Our patient achieved remarkable improvement at 2-week follow-up (Figure, B), without any observed adverse effects. At that time, the patient’s mother refused further systemic treatment and opted for only the topical therapy as well as natural light therapy.

Practice Implications

Timely and accurate diagnosis of LP in pediatric patients, especially those with skin of color, is crucial. Early intervention is especially important in mitigating the risk for chronic symptoms and preventing potential scarring, which tends to be more pronounced and challenging to treat in individuals with darker skin tones.7 Although not present in our patient, it is important to note that LP can affect the face (including the eyelids) as well as the palms and soles in pediatric patients with skin of color.

The most common approach to management of pediatric LP involves the use of a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine, but the recalcitrant and generalized distribution of lesions warrants the administration of a systemic corticosteroid regardless of the patient’s age.6 In our patient, prompt administration of low-dose IM triamcinolone was both crucial and beneficial. Although an underutilized approach, IM triamcinolone helps to prevent the progression of lesions to the scalp, nails, and mucosa while also reducing inflammation and pruritus in glabrous skin.8

Triamcinolone acetonide injections—administered at concentrations of 5 to 40 mg/mL—directly into the lesion (0.5–1 cc per 2 cm2) are highly effective in managing recalcitrant thickened lesions such as those seen in hypertrophic LP and palmoplantar LP.6 This treatment is particularly beneficial when lesions are unresponsive to topical therapies. Administered every 3 to 6 weeks, these injections provide rapid symptom relief, typically within 72 hours,6 while also contributing to the reduction of lesion size and thickness over time. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide should be selected based on the lesion’s severity, with higher concentrations reserved for thicker, more resistant lesions. More frequent injections may be warranted in cases in which rapid lesion reduction is necessary, while less frequent sessions may suffice for maintenance therapy. It is important to follow patients closely for adverse effects, such as signs of local skin atrophy or hypopigmentation, and to adjust the dose or frequency accordingly. To mitigate these risks, consider using the lowest effective concentration and rotating injection sites if treating multiple lesions. Additionally, combining intralesional corticosteroids with topical therapies can enhance outcomes, particularly in cases in which monotherapy is insufficient.

Patients should be monitored vigilantly for complications of LP. The risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a particular concern for patients with skin of color. Other complications of untreated LP include nail deformities and scarring alopecia.9 Regular and thorough follow-ups every few months to monitor scalp, mucosal, and genital involvement are essential to manage this risk effectively.

Furthermore, patient education is key. Informing patients and their caregivers about the nature of LP, the available treatment options, and the importance of ongoing follow-up can help to enhance treatment adherence and improve overall outcomes.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641

- Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423-427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x

- George J, Murray T, Bain M. Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient. Contemp Pediatr. 2022;39:32-34.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 1, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- Mutalik SD, Belgaumkar VA, Rasal YD. Current perspectives in the treatment of childhood lichen planus. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2021;22:316-325. doi:10.4103/ijpd.ijpd_165_20

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi:10.1155/2014/742826

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory cutaneous disorder. Although it often is characterized by the 6 Ps—pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, and plaques with a predilection for the wrists and ankles—the presentation can vary in morphology and distribution.1-5 With an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population, LP is undoubtedly uncommon.1 Its prevalence in the pediatric population is especially low, with only 2% to 3% of cases manifesting in individuals younger than 20 years.2

Generalized LP (also referred to as eruptive or exanthematous LP) is a rarely reported clinical subtype in which lesions are disseminated or spread rapidly.5 The rarity of generalized LP in children often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, impacting the patient’s quality of life. Thus, there is a need for heightened awareness among clinicians on the variable presentation of LP in the pediatric population. Incorporating a punch biopsy for the diagnosis of LP when lesions manifest as widespread, erythematous to violaceous, flat-topped papules or plaques, along with the addition of an intramuscular (IM) injection in the treatment plan, improves overall patient outcomes.

Tools and Techniques

A detailed physical examination followed by a punch biopsy was critical for the diagnosis of generalized LP in a 7-year-old Black girl. The examination revealed a widespread distribution of dark, violaceous, polygonal, shiny, flat-topped, firm papules coalescing into plaques across the entire body, with a greater predilection for the legs and overlying joints (Figure, A). Some lesions exhibited fine, silver-white, reticular patterns consistent with Wickham striae. Notably, there was no involvement of the scalp, nails, or mucosal surfaces.

The patient had no relevant medical or family history of skin disease and no recent history of illness. She previously was treated by a pediatrician with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, a course of oral cephalexin, and oral cetirizine 10 mg once daily without relief of symptoms.

Although the clinical presentation was consistent with LP, the differential diagnosis included lichen simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and generalized granuloma annulare. To address the need for early recognition of LP in pediatric patients, a punch biopsy of a lesion on the left anterior thigh was performed and showed lichenoid interface dermatitis—a pivotal finding in distinguishing LP from other conditions in the differential.

Given the patient’s age and severity of the LP, a combination of topical and systemic therapies was prescribed—clobetasol cream 0.025% twice daily and 1 injection of 0.5 cc of IM triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL. This regimen was guided by the efficacy of IM injections in providing prompt symptomatic relief, particularly for patients with extensive disease or for those whose condition is refractory to topical treatments.6 Our patient achieved remarkable improvement at 2-week follow-up (Figure, B), without any observed adverse effects. At that time, the patient’s mother refused further systemic treatment and opted for only the topical therapy as well as natural light therapy.

Practice Implications

Timely and accurate diagnosis of LP in pediatric patients, especially those with skin of color, is crucial. Early intervention is especially important in mitigating the risk for chronic symptoms and preventing potential scarring, which tends to be more pronounced and challenging to treat in individuals with darker skin tones.7 Although not present in our patient, it is important to note that LP can affect the face (including the eyelids) as well as the palms and soles in pediatric patients with skin of color.

The most common approach to management of pediatric LP involves the use of a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine, but the recalcitrant and generalized distribution of lesions warrants the administration of a systemic corticosteroid regardless of the patient’s age.6 In our patient, prompt administration of low-dose IM triamcinolone was both crucial and beneficial. Although an underutilized approach, IM triamcinolone helps to prevent the progression of lesions to the scalp, nails, and mucosa while also reducing inflammation and pruritus in glabrous skin.8

Triamcinolone acetonide injections—administered at concentrations of 5 to 40 mg/mL—directly into the lesion (0.5–1 cc per 2 cm2) are highly effective in managing recalcitrant thickened lesions such as those seen in hypertrophic LP and palmoplantar LP.6 This treatment is particularly beneficial when lesions are unresponsive to topical therapies. Administered every 3 to 6 weeks, these injections provide rapid symptom relief, typically within 72 hours,6 while also contributing to the reduction of lesion size and thickness over time. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide should be selected based on the lesion’s severity, with higher concentrations reserved for thicker, more resistant lesions. More frequent injections may be warranted in cases in which rapid lesion reduction is necessary, while less frequent sessions may suffice for maintenance therapy. It is important to follow patients closely for adverse effects, such as signs of local skin atrophy or hypopigmentation, and to adjust the dose or frequency accordingly. To mitigate these risks, consider using the lowest effective concentration and rotating injection sites if treating multiple lesions. Additionally, combining intralesional corticosteroids with topical therapies can enhance outcomes, particularly in cases in which monotherapy is insufficient.

Patients should be monitored vigilantly for complications of LP. The risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a particular concern for patients with skin of color. Other complications of untreated LP include nail deformities and scarring alopecia.9 Regular and thorough follow-ups every few months to monitor scalp, mucosal, and genital involvement are essential to manage this risk effectively.

Furthermore, patient education is key. Informing patients and their caregivers about the nature of LP, the available treatment options, and the importance of ongoing follow-up can help to enhance treatment adherence and improve overall outcomes.

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory cutaneous disorder. Although it often is characterized by the 6 Ps—pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, and plaques with a predilection for the wrists and ankles—the presentation can vary in morphology and distribution.1-5 With an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population, LP is undoubtedly uncommon.1 Its prevalence in the pediatric population is especially low, with only 2% to 3% of cases manifesting in individuals younger than 20 years.2

Generalized LP (also referred to as eruptive or exanthematous LP) is a rarely reported clinical subtype in which lesions are disseminated or spread rapidly.5 The rarity of generalized LP in children often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, impacting the patient’s quality of life. Thus, there is a need for heightened awareness among clinicians on the variable presentation of LP in the pediatric population. Incorporating a punch biopsy for the diagnosis of LP when lesions manifest as widespread, erythematous to violaceous, flat-topped papules or plaques, along with the addition of an intramuscular (IM) injection in the treatment plan, improves overall patient outcomes.

Tools and Techniques

A detailed physical examination followed by a punch biopsy was critical for the diagnosis of generalized LP in a 7-year-old Black girl. The examination revealed a widespread distribution of dark, violaceous, polygonal, shiny, flat-topped, firm papules coalescing into plaques across the entire body, with a greater predilection for the legs and overlying joints (Figure, A). Some lesions exhibited fine, silver-white, reticular patterns consistent with Wickham striae. Notably, there was no involvement of the scalp, nails, or mucosal surfaces.

The patient had no relevant medical or family history of skin disease and no recent history of illness. She previously was treated by a pediatrician with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, a course of oral cephalexin, and oral cetirizine 10 mg once daily without relief of symptoms.

Although the clinical presentation was consistent with LP, the differential diagnosis included lichen simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and generalized granuloma annulare. To address the need for early recognition of LP in pediatric patients, a punch biopsy of a lesion on the left anterior thigh was performed and showed lichenoid interface dermatitis—a pivotal finding in distinguishing LP from other conditions in the differential.

Given the patient’s age and severity of the LP, a combination of topical and systemic therapies was prescribed—clobetasol cream 0.025% twice daily and 1 injection of 0.5 cc of IM triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL. This regimen was guided by the efficacy of IM injections in providing prompt symptomatic relief, particularly for patients with extensive disease or for those whose condition is refractory to topical treatments.6 Our patient achieved remarkable improvement at 2-week follow-up (Figure, B), without any observed adverse effects. At that time, the patient’s mother refused further systemic treatment and opted for only the topical therapy as well as natural light therapy.

Practice Implications

Timely and accurate diagnosis of LP in pediatric patients, especially those with skin of color, is crucial. Early intervention is especially important in mitigating the risk for chronic symptoms and preventing potential scarring, which tends to be more pronounced and challenging to treat in individuals with darker skin tones.7 Although not present in our patient, it is important to note that LP can affect the face (including the eyelids) as well as the palms and soles in pediatric patients with skin of color.

The most common approach to management of pediatric LP involves the use of a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine, but the recalcitrant and generalized distribution of lesions warrants the administration of a systemic corticosteroid regardless of the patient’s age.6 In our patient, prompt administration of low-dose IM triamcinolone was both crucial and beneficial. Although an underutilized approach, IM triamcinolone helps to prevent the progression of lesions to the scalp, nails, and mucosa while also reducing inflammation and pruritus in glabrous skin.8

Triamcinolone acetonide injections—administered at concentrations of 5 to 40 mg/mL—directly into the lesion (0.5–1 cc per 2 cm2) are highly effective in managing recalcitrant thickened lesions such as those seen in hypertrophic LP and palmoplantar LP.6 This treatment is particularly beneficial when lesions are unresponsive to topical therapies. Administered every 3 to 6 weeks, these injections provide rapid symptom relief, typically within 72 hours,6 while also contributing to the reduction of lesion size and thickness over time. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide should be selected based on the lesion’s severity, with higher concentrations reserved for thicker, more resistant lesions. More frequent injections may be warranted in cases in which rapid lesion reduction is necessary, while less frequent sessions may suffice for maintenance therapy. It is important to follow patients closely for adverse effects, such as signs of local skin atrophy or hypopigmentation, and to adjust the dose or frequency accordingly. To mitigate these risks, consider using the lowest effective concentration and rotating injection sites if treating multiple lesions. Additionally, combining intralesional corticosteroids with topical therapies can enhance outcomes, particularly in cases in which monotherapy is insufficient.

Patients should be monitored vigilantly for complications of LP. The risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a particular concern for patients with skin of color. Other complications of untreated LP include nail deformities and scarring alopecia.9 Regular and thorough follow-ups every few months to monitor scalp, mucosal, and genital involvement are essential to manage this risk effectively.

Furthermore, patient education is key. Informing patients and their caregivers about the nature of LP, the available treatment options, and the importance of ongoing follow-up can help to enhance treatment adherence and improve overall outcomes.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641

- Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423-427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x

- George J, Murray T, Bain M. Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient. Contemp Pediatr. 2022;39:32-34.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 1, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- Mutalik SD, Belgaumkar VA, Rasal YD. Current perspectives in the treatment of childhood lichen planus. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2021;22:316-325. doi:10.4103/ijpd.ijpd_165_20

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi:10.1155/2014/742826

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641

- Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423-427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x

- George J, Murray T, Bain M. Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient. Contemp Pediatr. 2022;39:32-34.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 1, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- Mutalik SD, Belgaumkar VA, Rasal YD. Current perspectives in the treatment of childhood lichen planus. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2021;22:316-325. doi:10.4103/ijpd.ijpd_165_20

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi:10.1155/2014/742826

Top DEI Topics to Incorporate Into Dermatology Residency Training: An Electronic Delphi Consensus Study

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

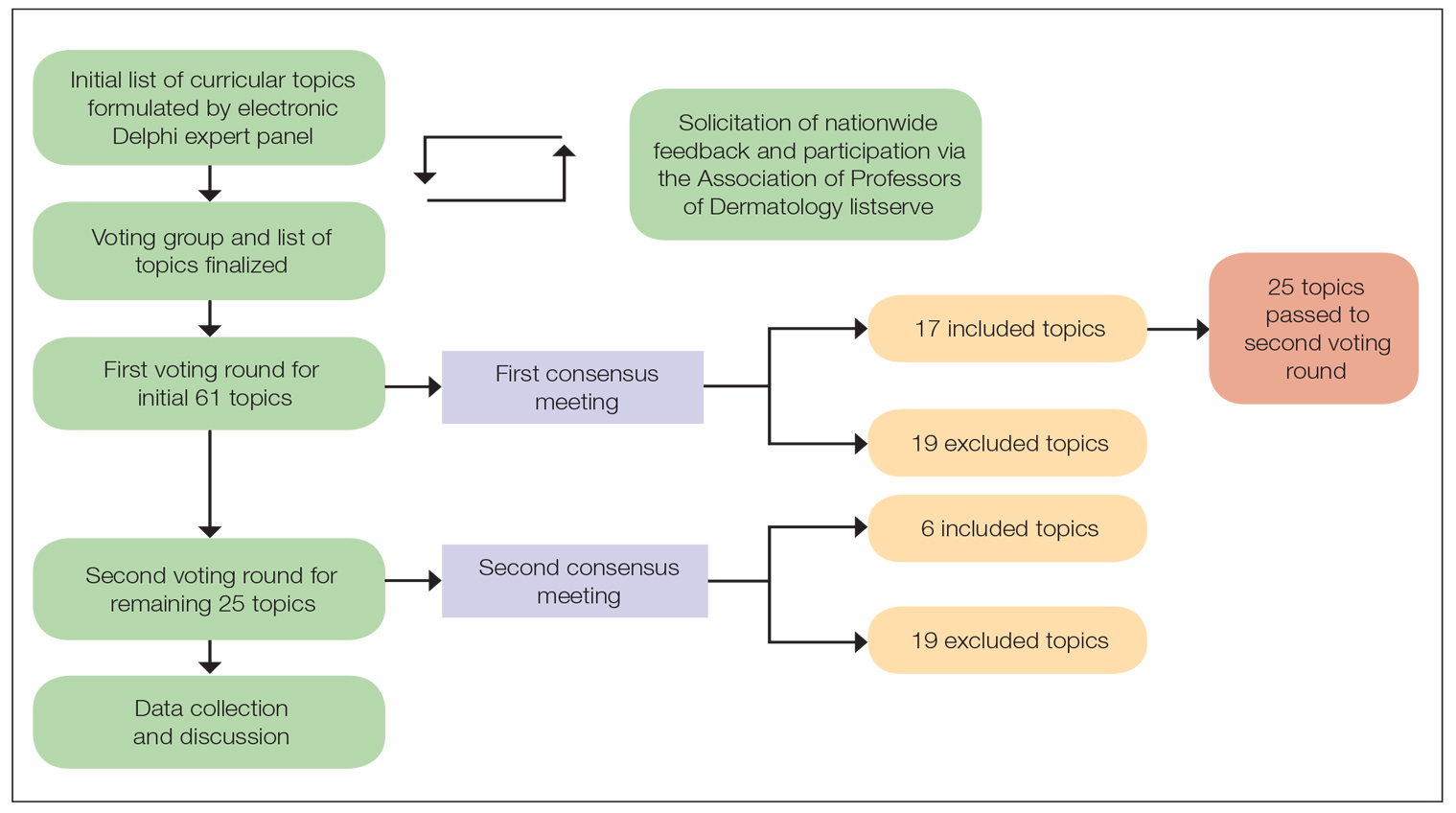

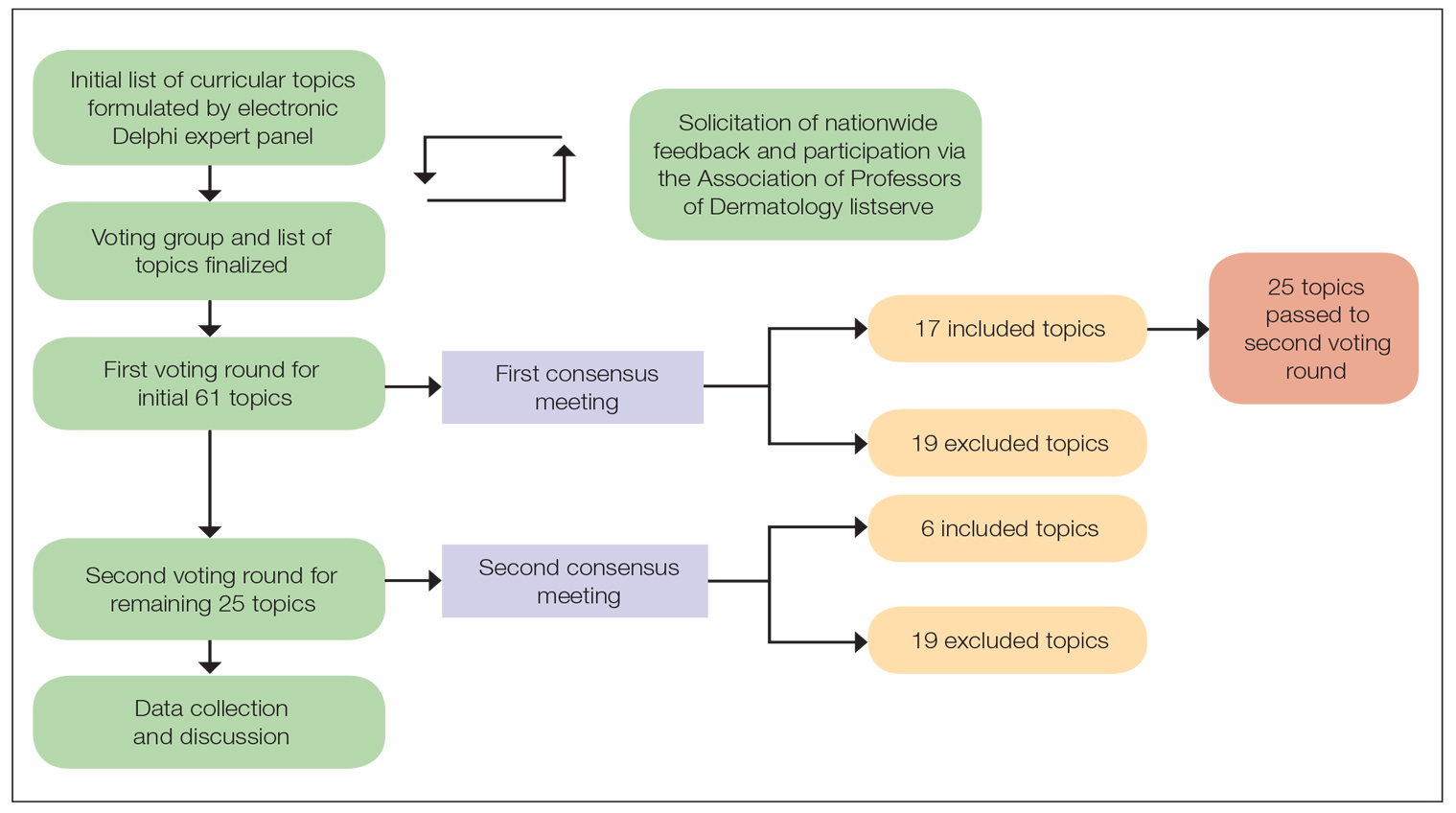

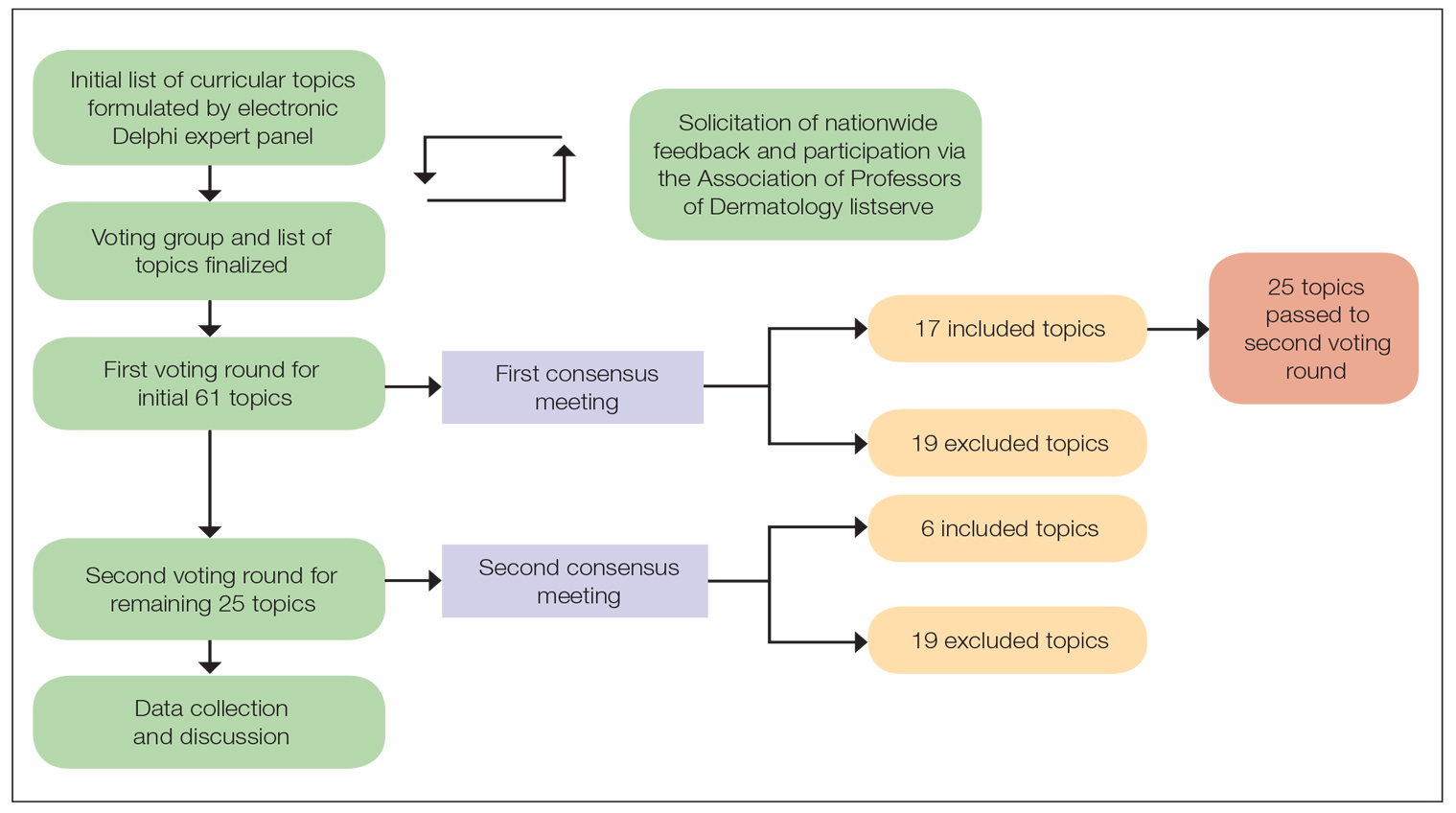

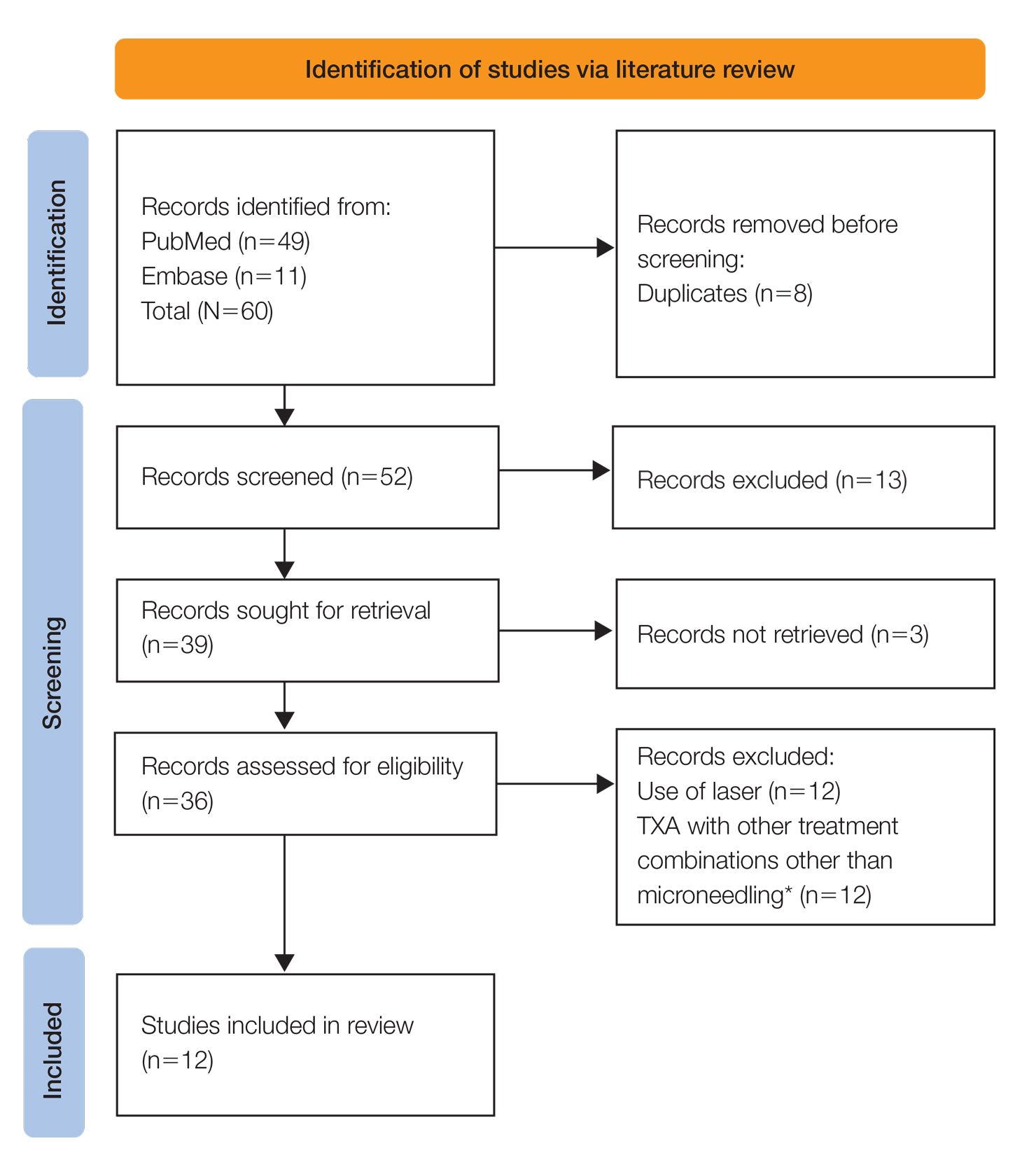

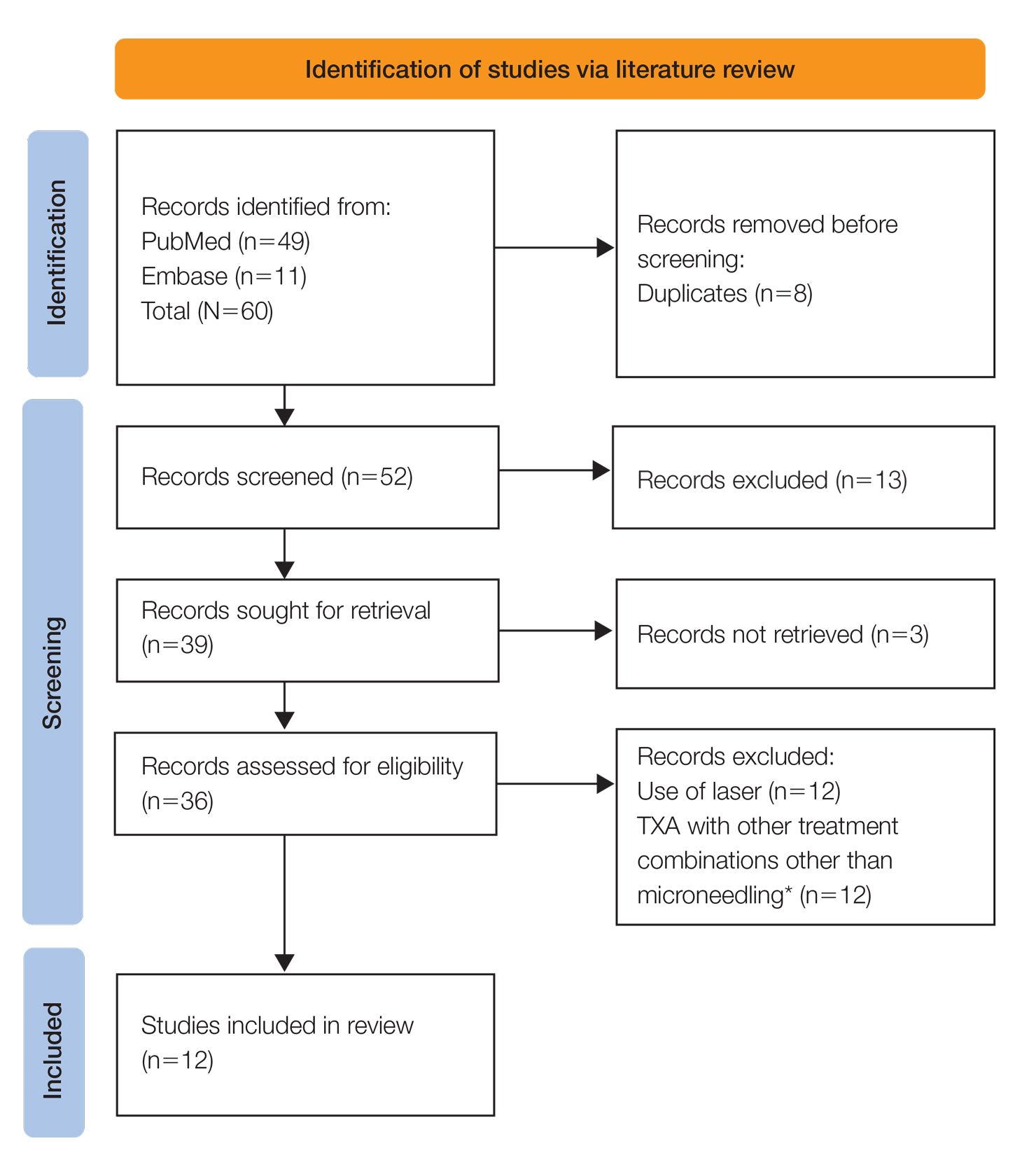

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

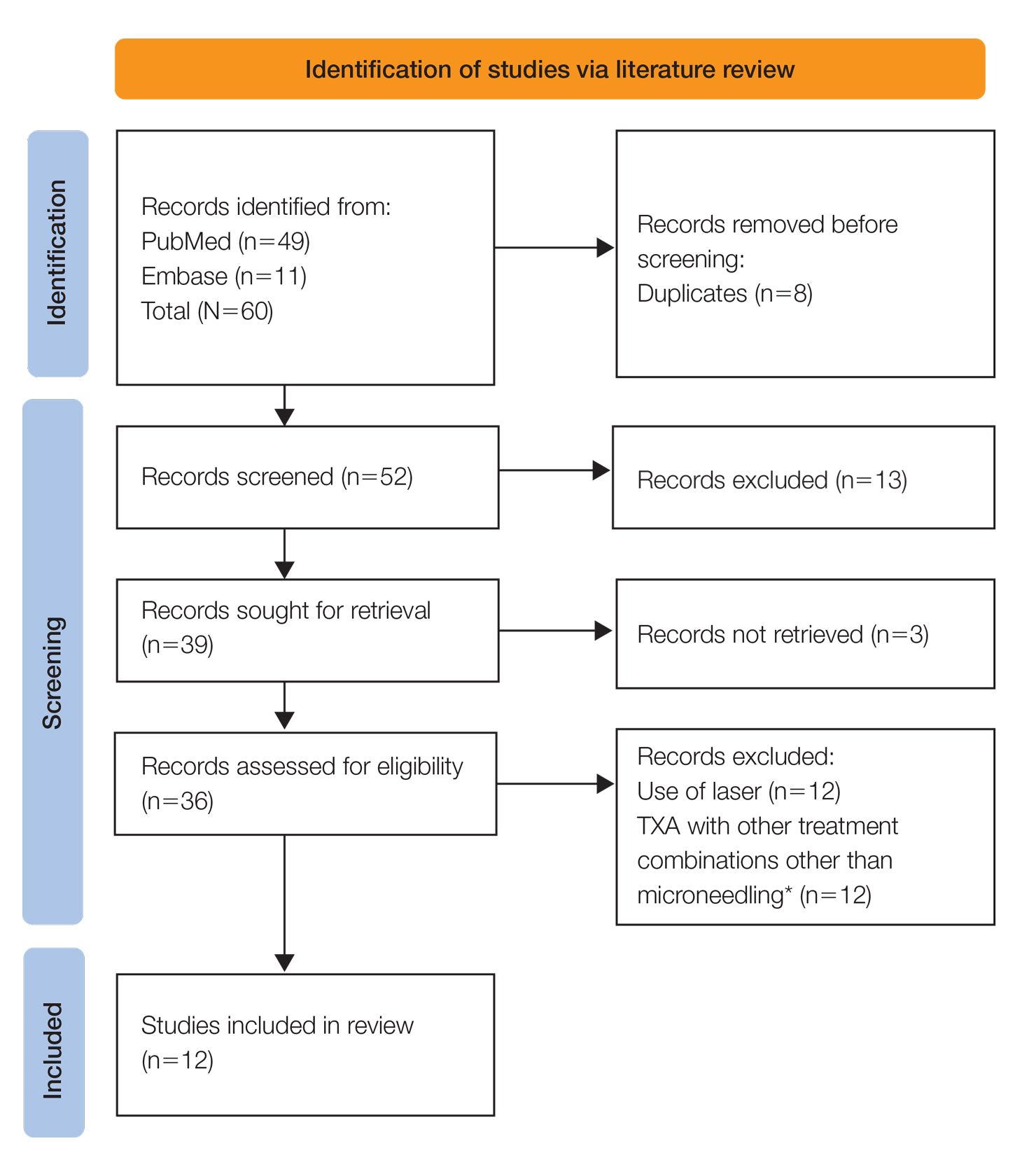

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

PRACTICE POINTS

- Advancing curricula related to diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology training can improve health outcomes, address health care workforce disparities, and enhance clinical care for diverse patient populations.

- Education on patient-centered communication, cultural humility, and the impact of social determinants of health results in dermatology residents who are better equipped with the necessary tools to effectively care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Metformin Led to Improvements in Women with Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia

TOPLINE:

, in a retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case series involving 12 Black women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, with biopsy-confirmed, treatment-refractory CCCA, a chronic inflammatory hair disorder characterized by permanent hair loss, from the Johns Hopkins University alopecia clinic.

- Participants received CCCA treatment for at least 6 months and had stagnant or worsening symptoms before oral extended-release metformin (500 mg daily) was added to treatment. (Treatments included topical clobetasol, compounded minoxidil, and platelet-rich plasma injections.)

- Scalp biopsies were collected from four patients before and after metformin treatment to evaluate gene expression changes.

- Changes in clinical symptoms were assessed, including pruritus, inflammation, pain, scalp resistance, and hair regrowth, following initiation of metformin treatment.

TAKEAWAY:

- Metformin led to significant clinical improvement in eight patients, which included reductions in scalp pain, scalp resistance, pruritus, and inflammation. However, two patients experienced worsening symptoms.

- Six patients showed clinical evidence of hair regrowth after at least 6 months of metformin treatment with one experiencing hair loss again 3 months after discontinuing treatment.

- Transcriptomic analysis revealed 34 upregulated genes, which included upregulated of 23 hair keratin-associated proteins, and pathways related to keratinization, epidermis development, and the hair cycle. In addition, eight genes were downregulated, with pathways that included those associated with extracellular matrix organization, collagen fibril organization, and collagen metabolism.

- Gene set variation analysis showed reduced expression of T helper 17 cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathways and elevated adenosine monophosphate kinase signaling and keratin-associated proteins after treatment with metformin.

IN PRACTICE:

“Metformin’s ability to concomitantly target fibrosis and inflammation provides a plausible mechanism for its therapeutic effects in CCCA and other fibrosing alopecia disorders,” the authors concluded. But, they added, “larger prospective, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials are needed to rigorously evaluate metformin’s efficacy and optimal dosing for treatment of cicatricial alopecias.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Aaron Bao, Department of Dermatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and was published online on September 4 in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

A small sample size, retrospective design, lack of a placebo control group, and the single-center setting limited the generalizability of the study findings. In addition, the absence of a validated activity or severity scale for CCCA and the single posttreatment sampling limit the assessment and comparison of clinical symptoms and transcriptomic changes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the American Academy of Dermatology. One author reported several ties with pharmaceutical companies, a pending patent, and authorship for the UpToDate section on CCCA.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, in a retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case series involving 12 Black women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, with biopsy-confirmed, treatment-refractory CCCA, a chronic inflammatory hair disorder characterized by permanent hair loss, from the Johns Hopkins University alopecia clinic.

- Participants received CCCA treatment for at least 6 months and had stagnant or worsening symptoms before oral extended-release metformin (500 mg daily) was added to treatment. (Treatments included topical clobetasol, compounded minoxidil, and platelet-rich plasma injections.)

- Scalp biopsies were collected from four patients before and after metformin treatment to evaluate gene expression changes.

- Changes in clinical symptoms were assessed, including pruritus, inflammation, pain, scalp resistance, and hair regrowth, following initiation of metformin treatment.

TAKEAWAY:

- Metformin led to significant clinical improvement in eight patients, which included reductions in scalp pain, scalp resistance, pruritus, and inflammation. However, two patients experienced worsening symptoms.

- Six patients showed clinical evidence of hair regrowth after at least 6 months of metformin treatment with one experiencing hair loss again 3 months after discontinuing treatment.

- Transcriptomic analysis revealed 34 upregulated genes, which included upregulated of 23 hair keratin-associated proteins, and pathways related to keratinization, epidermis development, and the hair cycle. In addition, eight genes were downregulated, with pathways that included those associated with extracellular matrix organization, collagen fibril organization, and collagen metabolism.

- Gene set variation analysis showed reduced expression of T helper 17 cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathways and elevated adenosine monophosphate kinase signaling and keratin-associated proteins after treatment with metformin.

IN PRACTICE:

“Metformin’s ability to concomitantly target fibrosis and inflammation provides a plausible mechanism for its therapeutic effects in CCCA and other fibrosing alopecia disorders,” the authors concluded. But, they added, “larger prospective, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials are needed to rigorously evaluate metformin’s efficacy and optimal dosing for treatment of cicatricial alopecias.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Aaron Bao, Department of Dermatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and was published online on September 4 in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

A small sample size, retrospective design, lack of a placebo control group, and the single-center setting limited the generalizability of the study findings. In addition, the absence of a validated activity or severity scale for CCCA and the single posttreatment sampling limit the assessment and comparison of clinical symptoms and transcriptomic changes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the American Academy of Dermatology. One author reported several ties with pharmaceutical companies, a pending patent, and authorship for the UpToDate section on CCCA.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, in a retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case series involving 12 Black women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, with biopsy-confirmed, treatment-refractory CCCA, a chronic inflammatory hair disorder characterized by permanent hair loss, from the Johns Hopkins University alopecia clinic.

- Participants received CCCA treatment for at least 6 months and had stagnant or worsening symptoms before oral extended-release metformin (500 mg daily) was added to treatment. (Treatments included topical clobetasol, compounded minoxidil, and platelet-rich plasma injections.)

- Scalp biopsies were collected from four patients before and after metformin treatment to evaluate gene expression changes.

- Changes in clinical symptoms were assessed, including pruritus, inflammation, pain, scalp resistance, and hair regrowth, following initiation of metformin treatment.

TAKEAWAY:

- Metformin led to significant clinical improvement in eight patients, which included reductions in scalp pain, scalp resistance, pruritus, and inflammation. However, two patients experienced worsening symptoms.

- Six patients showed clinical evidence of hair regrowth after at least 6 months of metformin treatment with one experiencing hair loss again 3 months after discontinuing treatment.

- Transcriptomic analysis revealed 34 upregulated genes, which included upregulated of 23 hair keratin-associated proteins, and pathways related to keratinization, epidermis development, and the hair cycle. In addition, eight genes were downregulated, with pathways that included those associated with extracellular matrix organization, collagen fibril organization, and collagen metabolism.

- Gene set variation analysis showed reduced expression of T helper 17 cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathways and elevated adenosine monophosphate kinase signaling and keratin-associated proteins after treatment with metformin.

IN PRACTICE:

“Metformin’s ability to concomitantly target fibrosis and inflammation provides a plausible mechanism for its therapeutic effects in CCCA and other fibrosing alopecia disorders,” the authors concluded. But, they added, “larger prospective, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials are needed to rigorously evaluate metformin’s efficacy and optimal dosing for treatment of cicatricial alopecias.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Aaron Bao, Department of Dermatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and was published online on September 4 in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

A small sample size, retrospective design, lack of a placebo control group, and the single-center setting limited the generalizability of the study findings. In addition, the absence of a validated activity or severity scale for CCCA and the single posttreatment sampling limit the assessment and comparison of clinical symptoms and transcriptomic changes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the American Academy of Dermatology. One author reported several ties with pharmaceutical companies, a pending patent, and authorship for the UpToDate section on CCCA.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Breast Cancer Hormone Therapy May Protect Against Dementia

TOPLINE:

with the greatest benefit seen in younger Black women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hormone-modulating therapy is widely used to treat hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, but the cognitive effects of the treatment, including a potential link to dementia, remain unclear.

- To investigate, researchers used the SEER-Medicare linked database to identify women aged 65 years or older with breast cancer who did and did not receive hormone-modulating therapy within 3 years following their diagnosis.

- The researchers excluded women with preexisting Alzheimer’s disease/dementia diagnoses or those who had received hormone-modulating therapy before their breast cancer diagnosis.

- Analyses were adjusted for demographic, sociocultural, and clinical variables, and subgroup analyses evaluated the impact of age, race, and type of hormone-modulating therapy on Alzheimer’s disease/dementia risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among the 18,808 women included in the analysis, 66% received hormone-modulating therapy and 34% did not. During the mean follow-up of 12 years, 24% of hormone-modulating therapy users and 28% of nonusers developed Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

- Overall, hormone-modulating therapy use (vs nonuse) was associated with a significant 7% lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease/dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.93; P = .005), with notable age and racial differences.

- Hormone-modulating therapy use was associated with a 24% lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease/dementia in Black women aged 65-74 years (HR, 0.76), but that protective effect decreased to 19% in Black women aged 75 years or older (HR, 0.81). White women aged 65-74 years who received hormone-modulating therapy (vs those who did not) had an 11% lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease/dementia (HR, 0.89), but the association disappeared among those aged 75 years or older (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.02). Other races demonstrated no significant association between hormone-modulating therapy use and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

- Overall, the use of an aromatase inhibitor or a selective estrogen receptor modulator was associated with a significantly lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease/dementia (HR, 0.93 and HR, 0.89, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

Overall, the retrospective study found that “hormone therapy was associated with protection against [Alzheimer’s/dementia] in women aged 65 years or older with newly diagnosed breast cancer,” with the decrease in risk relatively greater for Black women and women younger than 75 years, the authors concluded.

“The results highlight the critical need for personalized breast cancer treatment plans that are tailored to the individual characteristics of each patient, particularly given the significantly higher likelihood (two to three times more) of Black women developing [Alzheimer’s/dementia], compared with their White counterparts,” the researchers added.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Chao Cai, PhD, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Outcomes Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, was published online on July 16 in JAMA Network Open.