User login

High mortality rates trail tracheostomy patients

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

FROM CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Daily polypill lowers BP, cholesterol in underserved population

A daily polypill regimen improved cardiovascular risk factors in a socioeconomically vulnerable minority population, in a randomized controlled trial.

Patients at a federally qualified community health center in Alabama who received treatment with a combination pill for 1 year had greater reductions in systolic blood pressure and LDL cholesterol than did patients who received usual care, according to results published online on Sept. 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The simplicity and low cost of the polypill regimen make this approach attractive” when barriers such as lack of income, underinsurance, and difficulty attending clinic visits are common, said first author Daniel Muñoz, MD, of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and coinvestigators. The investigators obtained the pills at a cost of $26 per month per participant.

People with low socioeconomic status and those who are nonwhite have high cardiovascular mortality, and the southeastern United States and rural areas have disproportionately high levels of cardiovascular disease burden, according to the investigators. The rates at which people with low socioeconomic status receive treatment for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia – leading cardiovascular disease risk factors – “are strikingly low,” Dr. Muñoz and colleagues said.

To assess the effectiveness of a polypill-based strategy in an underserved population with low socioeconomic status, the researchers conducted the randomized trial.

They enrolled 303 adults without cardiovascular disease, and 148 of the patients were randomized to receive the polypill, which contained generic versions of atorvastatin (10 mg), amlodipine (2.5 mg), losartan (25 mg), and hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg). The remaining 155 patients received usual care. All participants scheduled 2-month and 12-month follow-up visits.

The participants had an average age of 56 years, 60% were women, and more than 95% were black. More than 70% had an annual household income of less than $15,000. Baseline characteristics of the treatment groups did not significantly differ.

At baseline, the average BP was 140/83 mm Hg, and the average LDL cholesterol level was 113 mg/dL.

In all, 91% of the participants completed the 12-month trial visit. Average systolic BP decreased by 9 mm Hg in the group that received the polypill, compared with 2 mm Hg in the group that received usual care. Average LDL cholesterol level decreased by 15 mg/dL in the polypill group, versus 4 mg/dL in the usual-care group.

Changes in other medications

Clinicians discontinued or reduced doses of other antihypertensive or lipid-lowering medications in 44% of the patients in the polypill group and none in the usual-care group. Clinicians escalated therapy in 2% of the participants in the polypill group and in 10% of the usual-care group.

Side effects in participants who received the polypill included a 1% incidence of myalgias and a 1% incidence of hypotension or light-headedness. Liver function test results were normal.

Five serious adverse events that occurred during the trial – two in the polypill group and three in the usual-care group – were judged to be unrelated to the trial by a data and safety monitoring board.

The authors noted that limitations of the trial include its open-label design and that it was conducted at a single center.

“It is important to emphasize that use of the polypill does not preclude individualized, add-on therapies for residual elevations in blood-pressure or cholesterol levels, as judged by a patient’s physician,” said Dr. Muñoz and colleagues. “We recognize that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to cardiovascular disease prevention runs counter to current trends in precision medicine, in which clinical, genomic, and lifestyle factors are used for the development of individualized treatment strategies. Although the precision approach has clear virtues, a broader approach may benefit patients who face barriers to accessing the full advantages of precision medicine.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Prevention Research Network and the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed personal fees from Novartis outside the study.

SOURCE: Muñoz D et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18;381(12):1114-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815359.

A daily polypill regimen improved cardiovascular risk factors in a socioeconomically vulnerable minority population, in a randomized controlled trial.

Patients at a federally qualified community health center in Alabama who received treatment with a combination pill for 1 year had greater reductions in systolic blood pressure and LDL cholesterol than did patients who received usual care, according to results published online on Sept. 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The simplicity and low cost of the polypill regimen make this approach attractive” when barriers such as lack of income, underinsurance, and difficulty attending clinic visits are common, said first author Daniel Muñoz, MD, of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and coinvestigators. The investigators obtained the pills at a cost of $26 per month per participant.

People with low socioeconomic status and those who are nonwhite have high cardiovascular mortality, and the southeastern United States and rural areas have disproportionately high levels of cardiovascular disease burden, according to the investigators. The rates at which people with low socioeconomic status receive treatment for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia – leading cardiovascular disease risk factors – “are strikingly low,” Dr. Muñoz and colleagues said.

To assess the effectiveness of a polypill-based strategy in an underserved population with low socioeconomic status, the researchers conducted the randomized trial.

They enrolled 303 adults without cardiovascular disease, and 148 of the patients were randomized to receive the polypill, which contained generic versions of atorvastatin (10 mg), amlodipine (2.5 mg), losartan (25 mg), and hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg). The remaining 155 patients received usual care. All participants scheduled 2-month and 12-month follow-up visits.

The participants had an average age of 56 years, 60% were women, and more than 95% were black. More than 70% had an annual household income of less than $15,000. Baseline characteristics of the treatment groups did not significantly differ.

At baseline, the average BP was 140/83 mm Hg, and the average LDL cholesterol level was 113 mg/dL.

In all, 91% of the participants completed the 12-month trial visit. Average systolic BP decreased by 9 mm Hg in the group that received the polypill, compared with 2 mm Hg in the group that received usual care. Average LDL cholesterol level decreased by 15 mg/dL in the polypill group, versus 4 mg/dL in the usual-care group.

Changes in other medications

Clinicians discontinued or reduced doses of other antihypertensive or lipid-lowering medications in 44% of the patients in the polypill group and none in the usual-care group. Clinicians escalated therapy in 2% of the participants in the polypill group and in 10% of the usual-care group.

Side effects in participants who received the polypill included a 1% incidence of myalgias and a 1% incidence of hypotension or light-headedness. Liver function test results were normal.

Five serious adverse events that occurred during the trial – two in the polypill group and three in the usual-care group – were judged to be unrelated to the trial by a data and safety monitoring board.

The authors noted that limitations of the trial include its open-label design and that it was conducted at a single center.

“It is important to emphasize that use of the polypill does not preclude individualized, add-on therapies for residual elevations in blood-pressure or cholesterol levels, as judged by a patient’s physician,” said Dr. Muñoz and colleagues. “We recognize that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to cardiovascular disease prevention runs counter to current trends in precision medicine, in which clinical, genomic, and lifestyle factors are used for the development of individualized treatment strategies. Although the precision approach has clear virtues, a broader approach may benefit patients who face barriers to accessing the full advantages of precision medicine.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Prevention Research Network and the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed personal fees from Novartis outside the study.

SOURCE: Muñoz D et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18;381(12):1114-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815359.

A daily polypill regimen improved cardiovascular risk factors in a socioeconomically vulnerable minority population, in a randomized controlled trial.

Patients at a federally qualified community health center in Alabama who received treatment with a combination pill for 1 year had greater reductions in systolic blood pressure and LDL cholesterol than did patients who received usual care, according to results published online on Sept. 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The simplicity and low cost of the polypill regimen make this approach attractive” when barriers such as lack of income, underinsurance, and difficulty attending clinic visits are common, said first author Daniel Muñoz, MD, of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and coinvestigators. The investigators obtained the pills at a cost of $26 per month per participant.

People with low socioeconomic status and those who are nonwhite have high cardiovascular mortality, and the southeastern United States and rural areas have disproportionately high levels of cardiovascular disease burden, according to the investigators. The rates at which people with low socioeconomic status receive treatment for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia – leading cardiovascular disease risk factors – “are strikingly low,” Dr. Muñoz and colleagues said.

To assess the effectiveness of a polypill-based strategy in an underserved population with low socioeconomic status, the researchers conducted the randomized trial.

They enrolled 303 adults without cardiovascular disease, and 148 of the patients were randomized to receive the polypill, which contained generic versions of atorvastatin (10 mg), amlodipine (2.5 mg), losartan (25 mg), and hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg). The remaining 155 patients received usual care. All participants scheduled 2-month and 12-month follow-up visits.

The participants had an average age of 56 years, 60% were women, and more than 95% were black. More than 70% had an annual household income of less than $15,000. Baseline characteristics of the treatment groups did not significantly differ.

At baseline, the average BP was 140/83 mm Hg, and the average LDL cholesterol level was 113 mg/dL.

In all, 91% of the participants completed the 12-month trial visit. Average systolic BP decreased by 9 mm Hg in the group that received the polypill, compared with 2 mm Hg in the group that received usual care. Average LDL cholesterol level decreased by 15 mg/dL in the polypill group, versus 4 mg/dL in the usual-care group.

Changes in other medications

Clinicians discontinued or reduced doses of other antihypertensive or lipid-lowering medications in 44% of the patients in the polypill group and none in the usual-care group. Clinicians escalated therapy in 2% of the participants in the polypill group and in 10% of the usual-care group.

Side effects in participants who received the polypill included a 1% incidence of myalgias and a 1% incidence of hypotension or light-headedness. Liver function test results were normal.

Five serious adverse events that occurred during the trial – two in the polypill group and three in the usual-care group – were judged to be unrelated to the trial by a data and safety monitoring board.

The authors noted that limitations of the trial include its open-label design and that it was conducted at a single center.

“It is important to emphasize that use of the polypill does not preclude individualized, add-on therapies for residual elevations in blood-pressure or cholesterol levels, as judged by a patient’s physician,” said Dr. Muñoz and colleagues. “We recognize that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to cardiovascular disease prevention runs counter to current trends in precision medicine, in which clinical, genomic, and lifestyle factors are used for the development of individualized treatment strategies. Although the precision approach has clear virtues, a broader approach may benefit patients who face barriers to accessing the full advantages of precision medicine.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Prevention Research Network and the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed personal fees from Novartis outside the study.

SOURCE: Muñoz D et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18;381(12):1114-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815359.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A daily polypill regimen may improve cardiovascular disease prevention in underserved populations.

Major finding: Mean LDL cholesterol levels decreased by 15 mg/dL in the polypill group, vs. 4 mg/dL in the usual-care group.

Study details: An open-label, randomized trial that enrolled 303 adults without cardiovascular disease at a federally qualified community health center in Alabama.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Prevention Research Network and the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed personal fees from Novartis outside the study.

Source: Muñoz D et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1114-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815359.

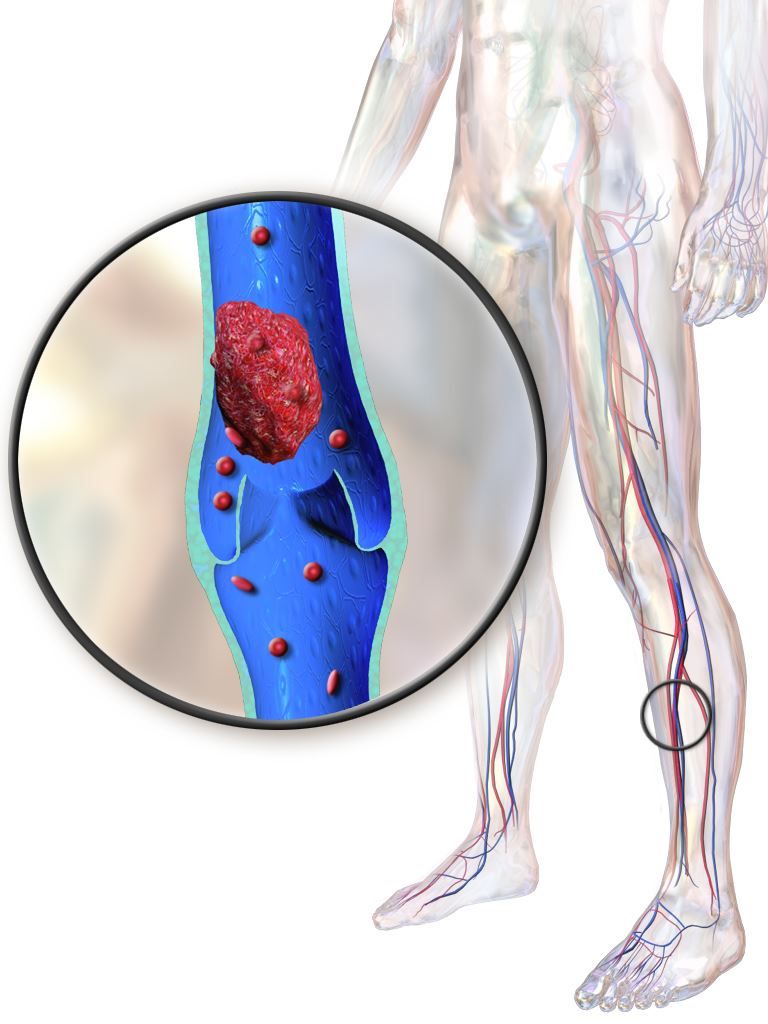

Older IBD patients are most at risk of postdischarge VTE

Hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are most likely to be readmitted for venous thromboembolism (VTE) within 60 days of discharge, according to a new study that analyzed 5 years of U.S. readmissions data.

“Given increased thrombotic risk postdischarge, as well as overall safety of VTE prophylaxis, extending prophylaxis for those at highest risk may have significant benefits,” wrote Adam S. Faye, MD, of Columbia University, and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine which IBD patients would be most in need of postdischarge VTE prophylaxis, as well as when to administer it, the researchers analyzed 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). They found a total of 872,122 index admissions for IBD patients; 4% of those patients had a prior VTE. Of the index admissions, 1,160 led to a VTE readmission within 90 days. Readmitted patients had a relatively equal proportion of ulcerative colitis (n = 522) and Crohn’s disease (n = 638).

More than 90% of VTE readmissions occurred within 60 days of discharge; the risk was highest over the first 10 days and then decreased in each ensuing 10-day period until a slight increase at the 81- to 90-day period. All patients over age 30 had higher rates of readmission than those of patients under age 18, with the highest risk in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 years (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01). Women were at lower risk (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.92, P less than .01). Higher risks of readmission were also associated with being on Medicare (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58, P less than .01) compared with being on private insurance and being cared for at a large hospital (RR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52, P = .02) compared with a small hospital.

The highest risk of VTE readmission was associated with a prior history of VTE (RR 2.89; 95% CI, 2.40-3.48, P less than .01), having two or more comorbidities (RR 2.57; 95% CI, 2.11-3.12, P less than .01) and having a Clostridioides difficile infection as of index admission (RR 1.90; 95% CI, 1.51-2.38, P less than .01). In addition, increased risk was associated with being discharged to a nursing or care facility (RR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.20, P less than .01) or home with health services (RR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.38, P less than .01) compared with a routine discharge.

In their multivariable analysis, similar factors such as a history of VTE (adjusted RR 2.41; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90, P less than .01), two or more comorbidities (aRR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.20, P less than .01) and C. difficile infection (aRR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.17-1.85, P less than.01) continued to be associated with higher risk of VTE readmission.

Though they emphasized that the use of NRD data offered the impressive ability to “review over 15 million discharges across the U.S. annually,” Dr. Faye and coauthors acknowledged that their study did have limitations. These included the inability to verify via chart review the study’s outcomes and covariates. In addition, they were unable to assess potential contributing risk factors such as medication use, use of VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization, disease severity, and family history. Finally, though unlikely, they admitted the possibility that patients could be counted more than once if they were readmitted with a VTE each year of the study.

The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

SOURCE: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

Hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are most likely to be readmitted for venous thromboembolism (VTE) within 60 days of discharge, according to a new study that analyzed 5 years of U.S. readmissions data.

“Given increased thrombotic risk postdischarge, as well as overall safety of VTE prophylaxis, extending prophylaxis for those at highest risk may have significant benefits,” wrote Adam S. Faye, MD, of Columbia University, and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine which IBD patients would be most in need of postdischarge VTE prophylaxis, as well as when to administer it, the researchers analyzed 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). They found a total of 872,122 index admissions for IBD patients; 4% of those patients had a prior VTE. Of the index admissions, 1,160 led to a VTE readmission within 90 days. Readmitted patients had a relatively equal proportion of ulcerative colitis (n = 522) and Crohn’s disease (n = 638).

More than 90% of VTE readmissions occurred within 60 days of discharge; the risk was highest over the first 10 days and then decreased in each ensuing 10-day period until a slight increase at the 81- to 90-day period. All patients over age 30 had higher rates of readmission than those of patients under age 18, with the highest risk in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 years (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01). Women were at lower risk (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.92, P less than .01). Higher risks of readmission were also associated with being on Medicare (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58, P less than .01) compared with being on private insurance and being cared for at a large hospital (RR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52, P = .02) compared with a small hospital.

The highest risk of VTE readmission was associated with a prior history of VTE (RR 2.89; 95% CI, 2.40-3.48, P less than .01), having two or more comorbidities (RR 2.57; 95% CI, 2.11-3.12, P less than .01) and having a Clostridioides difficile infection as of index admission (RR 1.90; 95% CI, 1.51-2.38, P less than .01). In addition, increased risk was associated with being discharged to a nursing or care facility (RR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.20, P less than .01) or home with health services (RR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.38, P less than .01) compared with a routine discharge.

In their multivariable analysis, similar factors such as a history of VTE (adjusted RR 2.41; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90, P less than .01), two or more comorbidities (aRR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.20, P less than .01) and C. difficile infection (aRR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.17-1.85, P less than.01) continued to be associated with higher risk of VTE readmission.

Though they emphasized that the use of NRD data offered the impressive ability to “review over 15 million discharges across the U.S. annually,” Dr. Faye and coauthors acknowledged that their study did have limitations. These included the inability to verify via chart review the study’s outcomes and covariates. In addition, they were unable to assess potential contributing risk factors such as medication use, use of VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization, disease severity, and family history. Finally, though unlikely, they admitted the possibility that patients could be counted more than once if they were readmitted with a VTE each year of the study.

The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

SOURCE: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

Hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are most likely to be readmitted for venous thromboembolism (VTE) within 60 days of discharge, according to a new study that analyzed 5 years of U.S. readmissions data.

“Given increased thrombotic risk postdischarge, as well as overall safety of VTE prophylaxis, extending prophylaxis for those at highest risk may have significant benefits,” wrote Adam S. Faye, MD, of Columbia University, and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine which IBD patients would be most in need of postdischarge VTE prophylaxis, as well as when to administer it, the researchers analyzed 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). They found a total of 872,122 index admissions for IBD patients; 4% of those patients had a prior VTE. Of the index admissions, 1,160 led to a VTE readmission within 90 days. Readmitted patients had a relatively equal proportion of ulcerative colitis (n = 522) and Crohn’s disease (n = 638).

More than 90% of VTE readmissions occurred within 60 days of discharge; the risk was highest over the first 10 days and then decreased in each ensuing 10-day period until a slight increase at the 81- to 90-day period. All patients over age 30 had higher rates of readmission than those of patients under age 18, with the highest risk in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 years (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01). Women were at lower risk (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.92, P less than .01). Higher risks of readmission were also associated with being on Medicare (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58, P less than .01) compared with being on private insurance and being cared for at a large hospital (RR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52, P = .02) compared with a small hospital.

The highest risk of VTE readmission was associated with a prior history of VTE (RR 2.89; 95% CI, 2.40-3.48, P less than .01), having two or more comorbidities (RR 2.57; 95% CI, 2.11-3.12, P less than .01) and having a Clostridioides difficile infection as of index admission (RR 1.90; 95% CI, 1.51-2.38, P less than .01). In addition, increased risk was associated with being discharged to a nursing or care facility (RR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.20, P less than .01) or home with health services (RR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.38, P less than .01) compared with a routine discharge.

In their multivariable analysis, similar factors such as a history of VTE (adjusted RR 2.41; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90, P less than .01), two or more comorbidities (aRR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.20, P less than .01) and C. difficile infection (aRR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.17-1.85, P less than.01) continued to be associated with higher risk of VTE readmission.

Though they emphasized that the use of NRD data offered the impressive ability to “review over 15 million discharges across the U.S. annually,” Dr. Faye and coauthors acknowledged that their study did have limitations. These included the inability to verify via chart review the study’s outcomes and covariates. In addition, they were unable to assess potential contributing risk factors such as medication use, use of VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization, disease severity, and family history. Finally, though unlikely, they admitted the possibility that patients could be counted more than once if they were readmitted with a VTE each year of the study.

The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

SOURCE: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Readmission for VTE in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases most often occurs within 60 days of discharge.

Major finding: The highest readmission risk was in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01).

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 1,160 IBD patients who had VTE readmissions via 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database.

Disclosures: The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

Source: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

Poll: How much has the price of insulin risen in the past 15 years?

Choose your answer in the poll below. To check the accuracy of your answer, see Endocrine Consult: 10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs.

[polldaddy:10400221]

Click on page 2 below to find out what the correct answer is...

The correct answer is d.) 500%

To learn more, see this month's Endocrine Consult: 10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs.

Choose your answer in the poll below. To check the accuracy of your answer, see Endocrine Consult: 10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs.

[polldaddy:10400221]

Click on page 2 below to find out what the correct answer is...

The correct answer is d.) 500%

To learn more, see this month's Endocrine Consult: 10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs.

Choose your answer in the poll below. To check the accuracy of your answer, see Endocrine Consult: 10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs.

[polldaddy:10400221]

Click on page 2 below to find out what the correct answer is...

The correct answer is d.) 500%

To learn more, see this month's Endocrine Consult: 10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs.

10 (Safe) Ways to Reduce Patients’ Insulin Costs

Almost a century after its discovery, insulin remains a life-saving yet costly medication: In the past 15 years, prices have risen more than 500%.1 Patients may ask you why the insulin you prescribe is so expensive, and the complex process for determining drug costs makes it difficult to answer. But the bottom line is, patients need their insulin—and they want it without breaking the bank.

Thankfully, there are several strategies for reducing the cost of insulin. First and foremost, patients must be advised that not taking their prescribed insulin, or taking less insulin than prescribed, is not a safe alternative. An individualized cost-benefit analysis between patient and provider can help to determine the best option for each patient. After working in endocrinology for 5 years, I have learned the following 10 ways to help patients whose financial situations limit their access to insulin.

1 Try older insulins, including mixed insulin 70/30 or 50/50, insulin NPH, or regular insulin. Because the beneficial effects may not be as long lasting with these as with newer insulins on the market, your patient may need to test glucose levels more frequently. Also, insulin NPH and any mixed insulins are suspensions, not solutions, so patients will need to gently roll older insulins prior to use. Those in pen form may also have a shorter shelf life.

2 Switch to a syringe and vial. Although dosing can be less precise, this could be a viable option for patients with good vision and dexterity. This method helps patients save in 3 ways: (1) the insulin is less expensive; (2) syringes generally cost less (about $30 for 100) than pen needle tips (about $50 for 100); and (3) vials of NPH are longer-lasting suspensions that are stable for about 28 days once opened, compared to 14 days for pens.2-4

3 Switch from a 30- to a 90-day supply of refills. This helps to lower copays. For example, a mail-order program (eg, Express Scripts) that ships from a warehouse typically offers lower pricing than a brick-and-mortar pharmacy with greater overhead. Many of these programs provide 2-pharmacist verification for accuracy and free home delivery of medications at a 10% discount, as well as 24-hour pharmacist access.5 The ease of obtaining prescriptions by this method also can help with medication adherence.

4 Patient assistance programs (PAPs) offered by insulin manufacturers can help lower costs for patients who find it difficult to afford their medication. Information on these programs is available on the respective company’s websites, usually in multiple languages (although some are limited to English and Spanish). Patients applying for a PAP must provide a proof of income and adhere to the program’s specific criteria. Renewal is typically required each year.6-8

5 Copay cards are available to many patients with private insurance and may help make insulin more affordable. Patients may be able to receive a $25 monthly supply of insulin for up to 1 year (specific terms vary). Maximum contributions and contributions toward deductibles also vary by program, so patients need to familiarize themselves with what their particular copay card allows. Generally, copay cards are not a sustainable long-term solution; for one thing, they expire, and for another, emphasis should be placed on affordable medications rather than affording expensive medications.

[polldaddy:10400221]

Continue to: 6 External PAPs for patients on Medicare...

6 External PAPs for patients on Medicare can help lower the costs of prescription medications.9 A database of pharmaceutical PAPs is available on the Medicare website.10 Some PAPs may help patients on Medicare pay through the $5,100 coverage gap or “donut hole”—a term referring to a gap in prescription drug coverage once patients have met their prescription limit (all Medicare part D plans have a donut hole).11,12 Patients and providers will need to read the fine print when applying for an external PAP, because some have a monthly or one-time start-up fee for processing the paperwork (and note, there is often paperwork for the relief program in addition to the PAP paperwork through the pharmaceutical company).

7 A Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is available in many states; check medicare.gov to see if your state is eligible. For patients 55 and older on Medicare or Medicaid who do not opt for care at a nursing home facility, PACE may be able to provide care and coverage in the patient’s home or at a PACE facility. Services include primary care, hospital care, laboratory and x-ray services, medical specialty services, and prescription drugs. To be eligible for PACE services, the patient must live in the service area of a PACE organization and have a requirement for a nursing home-level of care (as certified by your state).

8 Shop around for the best deal. Encourage your patients to comparison shop for the best prices rather than accepting the first or only option at their usual pharmacy. Different pharmacies offer drugs at lower prices than competitors. Also, continually compare prices at GoodRx or HealthWarehouse.com. The latter—a fully licensed Internet-based pharmacy—sells FDA-approved medications at affordable prices in all 50 states, without the requirement for insurance coverage.

9 Use of a patch pump may be less expensive for patients with type 2 diabetes who are taking basal-bolus regimens. Patches slowly deliver single short-acting insulin (usually insulin aspart or lispro) that acts as a basal insulin, with an additional reservoir for prandial insulin at mealtime and for snacks. As there is a catheter in the patch, patients would not require the use of needles.13

10 Try removing mealtime insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes who need minimal mealtime insulin. Clinicians can initiate a safe trial of this removal by encouraging the patient to consume a low-carbohydrate diet, increase exercise, and/or use other noninsulin medications that are more affordable.

Continue to: The affordability of insulins...

The affordability of insulins is a potentially uncomfortable but necessary conversation to have with your patient. Providers are one of the best resources for patients who seek relief from financial difficulties. The recommendations discussed here can help providers and patients design a cost-conscious plan for insulin treatment. Although each recommendation is viable, the pros and cons must be weighed on a case-by-case basis. Providers and patients should also pay attention to the Senate Finance Committee’s ongoing discussions and possible resolutions that could result in lower insulin costs. Until legislation that lowers the prices of insulin comes to fruition, however, providers should continue to plan with their patients on how to best get their insulin at the lowest cost.

Test yourself with the poll here.

1. Grassley, Wyden launch bipartisan investigation into insulin prices. United States Senate Committee on Finance website. www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/grassley-wyden-launch-bipartisan-investigation-into-insulin-prices. Published February 22, 2019. Accessed August 16, 2019.

2. BD Ultra-Fine. Syringe. GoodRx website. www.goodrx.com/bd-ultra-fine?dosage=31-gauge-5-16%22-of-1-cc&form=syringe&label_override=BD+Ultra-Fine&quantity=100. Accessed August 16, 2019.

3. BD Ultra-Fine. Pen needle. GoodRx website. www.goodrx.com/bd-ultra-fine?dosage=5-32%22-of-32-gauge&form=pen-needle&label_override=BD+Ultra-Fine&quantity=100. Accessed August 16, 2019.

4. Joffee D. Stability of common insulins in pens and vials. Diabetes in Control website. www.diabetesincontrol.com/wp-content/uploads/PDF/se_insulin_stability_chart.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed August 16, 2019.

5. Frequently asked questions. Preferred home delivery program for maintenance medications. Express Scripts website. www.express-scripts.com/art/pdf/SST-custom-preferred-faq.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

6. Patient Connection. Sanofi Patient Connection website. www.sanofipatientconnection.com/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

7. The Lilly Cares Foundation Patient Assistance Program. Lilly website. www.lillycares.com/assistanceprograms.aspx. Accessed August 16, 2019.

8. Novo Nordisk Patient Assistance Program. NovoCare website. www.novocare.com/psp/PAP.html. Accessed August 16, 2019.

9. 6 ways to get help with prescription costs. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap/6-ways-to-get-help-with-prescription-costs. Accessed August 16, 2019.

10. Pharmaceutical assistance program. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/pharmaceutical-assistance-program/Index.aspx. Accessed August 16, 2019.

11. Catastrophic coverage. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/catastrophic-coverage. Accessed August 16, 2019.

12. Costs in the coverage gap. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap. Accessed August 16, 2019.

13. V-Go Reimbursement Assistance Program. V-Go website. www.go-vgo.com/coverage-savings/overview/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

Almost a century after its discovery, insulin remains a life-saving yet costly medication: In the past 15 years, prices have risen more than 500%.1 Patients may ask you why the insulin you prescribe is so expensive, and the complex process for determining drug costs makes it difficult to answer. But the bottom line is, patients need their insulin—and they want it without breaking the bank.

Thankfully, there are several strategies for reducing the cost of insulin. First and foremost, patients must be advised that not taking their prescribed insulin, or taking less insulin than prescribed, is not a safe alternative. An individualized cost-benefit analysis between patient and provider can help to determine the best option for each patient. After working in endocrinology for 5 years, I have learned the following 10 ways to help patients whose financial situations limit their access to insulin.

1 Try older insulins, including mixed insulin 70/30 or 50/50, insulin NPH, or regular insulin. Because the beneficial effects may not be as long lasting with these as with newer insulins on the market, your patient may need to test glucose levels more frequently. Also, insulin NPH and any mixed insulins are suspensions, not solutions, so patients will need to gently roll older insulins prior to use. Those in pen form may also have a shorter shelf life.

2 Switch to a syringe and vial. Although dosing can be less precise, this could be a viable option for patients with good vision and dexterity. This method helps patients save in 3 ways: (1) the insulin is less expensive; (2) syringes generally cost less (about $30 for 100) than pen needle tips (about $50 for 100); and (3) vials of NPH are longer-lasting suspensions that are stable for about 28 days once opened, compared to 14 days for pens.2-4

3 Switch from a 30- to a 90-day supply of refills. This helps to lower copays. For example, a mail-order program (eg, Express Scripts) that ships from a warehouse typically offers lower pricing than a brick-and-mortar pharmacy with greater overhead. Many of these programs provide 2-pharmacist verification for accuracy and free home delivery of medications at a 10% discount, as well as 24-hour pharmacist access.5 The ease of obtaining prescriptions by this method also can help with medication adherence.

4 Patient assistance programs (PAPs) offered by insulin manufacturers can help lower costs for patients who find it difficult to afford their medication. Information on these programs is available on the respective company’s websites, usually in multiple languages (although some are limited to English and Spanish). Patients applying for a PAP must provide a proof of income and adhere to the program’s specific criteria. Renewal is typically required each year.6-8

5 Copay cards are available to many patients with private insurance and may help make insulin more affordable. Patients may be able to receive a $25 monthly supply of insulin for up to 1 year (specific terms vary). Maximum contributions and contributions toward deductibles also vary by program, so patients need to familiarize themselves with what their particular copay card allows. Generally, copay cards are not a sustainable long-term solution; for one thing, they expire, and for another, emphasis should be placed on affordable medications rather than affording expensive medications.

[polldaddy:10400221]

Continue to: 6 External PAPs for patients on Medicare...

6 External PAPs for patients on Medicare can help lower the costs of prescription medications.9 A database of pharmaceutical PAPs is available on the Medicare website.10 Some PAPs may help patients on Medicare pay through the $5,100 coverage gap or “donut hole”—a term referring to a gap in prescription drug coverage once patients have met their prescription limit (all Medicare part D plans have a donut hole).11,12 Patients and providers will need to read the fine print when applying for an external PAP, because some have a monthly or one-time start-up fee for processing the paperwork (and note, there is often paperwork for the relief program in addition to the PAP paperwork through the pharmaceutical company).

7 A Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is available in many states; check medicare.gov to see if your state is eligible. For patients 55 and older on Medicare or Medicaid who do not opt for care at a nursing home facility, PACE may be able to provide care and coverage in the patient’s home or at a PACE facility. Services include primary care, hospital care, laboratory and x-ray services, medical specialty services, and prescription drugs. To be eligible for PACE services, the patient must live in the service area of a PACE organization and have a requirement for a nursing home-level of care (as certified by your state).

8 Shop around for the best deal. Encourage your patients to comparison shop for the best prices rather than accepting the first or only option at their usual pharmacy. Different pharmacies offer drugs at lower prices than competitors. Also, continually compare prices at GoodRx or HealthWarehouse.com. The latter—a fully licensed Internet-based pharmacy—sells FDA-approved medications at affordable prices in all 50 states, without the requirement for insurance coverage.

9 Use of a patch pump may be less expensive for patients with type 2 diabetes who are taking basal-bolus regimens. Patches slowly deliver single short-acting insulin (usually insulin aspart or lispro) that acts as a basal insulin, with an additional reservoir for prandial insulin at mealtime and for snacks. As there is a catheter in the patch, patients would not require the use of needles.13

10 Try removing mealtime insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes who need minimal mealtime insulin. Clinicians can initiate a safe trial of this removal by encouraging the patient to consume a low-carbohydrate diet, increase exercise, and/or use other noninsulin medications that are more affordable.

Continue to: The affordability of insulins...

The affordability of insulins is a potentially uncomfortable but necessary conversation to have with your patient. Providers are one of the best resources for patients who seek relief from financial difficulties. The recommendations discussed here can help providers and patients design a cost-conscious plan for insulin treatment. Although each recommendation is viable, the pros and cons must be weighed on a case-by-case basis. Providers and patients should also pay attention to the Senate Finance Committee’s ongoing discussions and possible resolutions that could result in lower insulin costs. Until legislation that lowers the prices of insulin comes to fruition, however, providers should continue to plan with their patients on how to best get their insulin at the lowest cost.

Test yourself with the poll here.

Almost a century after its discovery, insulin remains a life-saving yet costly medication: In the past 15 years, prices have risen more than 500%.1 Patients may ask you why the insulin you prescribe is so expensive, and the complex process for determining drug costs makes it difficult to answer. But the bottom line is, patients need their insulin—and they want it without breaking the bank.

Thankfully, there are several strategies for reducing the cost of insulin. First and foremost, patients must be advised that not taking their prescribed insulin, or taking less insulin than prescribed, is not a safe alternative. An individualized cost-benefit analysis between patient and provider can help to determine the best option for each patient. After working in endocrinology for 5 years, I have learned the following 10 ways to help patients whose financial situations limit their access to insulin.

1 Try older insulins, including mixed insulin 70/30 or 50/50, insulin NPH, or regular insulin. Because the beneficial effects may not be as long lasting with these as with newer insulins on the market, your patient may need to test glucose levels more frequently. Also, insulin NPH and any mixed insulins are suspensions, not solutions, so patients will need to gently roll older insulins prior to use. Those in pen form may also have a shorter shelf life.

2 Switch to a syringe and vial. Although dosing can be less precise, this could be a viable option for patients with good vision and dexterity. This method helps patients save in 3 ways: (1) the insulin is less expensive; (2) syringes generally cost less (about $30 for 100) than pen needle tips (about $50 for 100); and (3) vials of NPH are longer-lasting suspensions that are stable for about 28 days once opened, compared to 14 days for pens.2-4

3 Switch from a 30- to a 90-day supply of refills. This helps to lower copays. For example, a mail-order program (eg, Express Scripts) that ships from a warehouse typically offers lower pricing than a brick-and-mortar pharmacy with greater overhead. Many of these programs provide 2-pharmacist verification for accuracy and free home delivery of medications at a 10% discount, as well as 24-hour pharmacist access.5 The ease of obtaining prescriptions by this method also can help with medication adherence.

4 Patient assistance programs (PAPs) offered by insulin manufacturers can help lower costs for patients who find it difficult to afford their medication. Information on these programs is available on the respective company’s websites, usually in multiple languages (although some are limited to English and Spanish). Patients applying for a PAP must provide a proof of income and adhere to the program’s specific criteria. Renewal is typically required each year.6-8

5 Copay cards are available to many patients with private insurance and may help make insulin more affordable. Patients may be able to receive a $25 monthly supply of insulin for up to 1 year (specific terms vary). Maximum contributions and contributions toward deductibles also vary by program, so patients need to familiarize themselves with what their particular copay card allows. Generally, copay cards are not a sustainable long-term solution; for one thing, they expire, and for another, emphasis should be placed on affordable medications rather than affording expensive medications.

[polldaddy:10400221]

Continue to: 6 External PAPs for patients on Medicare...

6 External PAPs for patients on Medicare can help lower the costs of prescription medications.9 A database of pharmaceutical PAPs is available on the Medicare website.10 Some PAPs may help patients on Medicare pay through the $5,100 coverage gap or “donut hole”—a term referring to a gap in prescription drug coverage once patients have met their prescription limit (all Medicare part D plans have a donut hole).11,12 Patients and providers will need to read the fine print when applying for an external PAP, because some have a monthly or one-time start-up fee for processing the paperwork (and note, there is often paperwork for the relief program in addition to the PAP paperwork through the pharmaceutical company).

7 A Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is available in many states; check medicare.gov to see if your state is eligible. For patients 55 and older on Medicare or Medicaid who do not opt for care at a nursing home facility, PACE may be able to provide care and coverage in the patient’s home or at a PACE facility. Services include primary care, hospital care, laboratory and x-ray services, medical specialty services, and prescription drugs. To be eligible for PACE services, the patient must live in the service area of a PACE organization and have a requirement for a nursing home-level of care (as certified by your state).

8 Shop around for the best deal. Encourage your patients to comparison shop for the best prices rather than accepting the first or only option at their usual pharmacy. Different pharmacies offer drugs at lower prices than competitors. Also, continually compare prices at GoodRx or HealthWarehouse.com. The latter—a fully licensed Internet-based pharmacy—sells FDA-approved medications at affordable prices in all 50 states, without the requirement for insurance coverage.

9 Use of a patch pump may be less expensive for patients with type 2 diabetes who are taking basal-bolus regimens. Patches slowly deliver single short-acting insulin (usually insulin aspart or lispro) that acts as a basal insulin, with an additional reservoir for prandial insulin at mealtime and for snacks. As there is a catheter in the patch, patients would not require the use of needles.13

10 Try removing mealtime insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes who need minimal mealtime insulin. Clinicians can initiate a safe trial of this removal by encouraging the patient to consume a low-carbohydrate diet, increase exercise, and/or use other noninsulin medications that are more affordable.

Continue to: The affordability of insulins...

The affordability of insulins is a potentially uncomfortable but necessary conversation to have with your patient. Providers are one of the best resources for patients who seek relief from financial difficulties. The recommendations discussed here can help providers and patients design a cost-conscious plan for insulin treatment. Although each recommendation is viable, the pros and cons must be weighed on a case-by-case basis. Providers and patients should also pay attention to the Senate Finance Committee’s ongoing discussions and possible resolutions that could result in lower insulin costs. Until legislation that lowers the prices of insulin comes to fruition, however, providers should continue to plan with their patients on how to best get their insulin at the lowest cost.

Test yourself with the poll here.

1. Grassley, Wyden launch bipartisan investigation into insulin prices. United States Senate Committee on Finance website. www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/grassley-wyden-launch-bipartisan-investigation-into-insulin-prices. Published February 22, 2019. Accessed August 16, 2019.

2. BD Ultra-Fine. Syringe. GoodRx website. www.goodrx.com/bd-ultra-fine?dosage=31-gauge-5-16%22-of-1-cc&form=syringe&label_override=BD+Ultra-Fine&quantity=100. Accessed August 16, 2019.

3. BD Ultra-Fine. Pen needle. GoodRx website. www.goodrx.com/bd-ultra-fine?dosage=5-32%22-of-32-gauge&form=pen-needle&label_override=BD+Ultra-Fine&quantity=100. Accessed August 16, 2019.

4. Joffee D. Stability of common insulins in pens and vials. Diabetes in Control website. www.diabetesincontrol.com/wp-content/uploads/PDF/se_insulin_stability_chart.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed August 16, 2019.

5. Frequently asked questions. Preferred home delivery program for maintenance medications. Express Scripts website. www.express-scripts.com/art/pdf/SST-custom-preferred-faq.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

6. Patient Connection. Sanofi Patient Connection website. www.sanofipatientconnection.com/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

7. The Lilly Cares Foundation Patient Assistance Program. Lilly website. www.lillycares.com/assistanceprograms.aspx. Accessed August 16, 2019.

8. Novo Nordisk Patient Assistance Program. NovoCare website. www.novocare.com/psp/PAP.html. Accessed August 16, 2019.

9. 6 ways to get help with prescription costs. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap/6-ways-to-get-help-with-prescription-costs. Accessed August 16, 2019.

10. Pharmaceutical assistance program. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/pharmaceutical-assistance-program/Index.aspx. Accessed August 16, 2019.

11. Catastrophic coverage. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/catastrophic-coverage. Accessed August 16, 2019.

12. Costs in the coverage gap. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap. Accessed August 16, 2019.

13. V-Go Reimbursement Assistance Program. V-Go website. www.go-vgo.com/coverage-savings/overview/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

1. Grassley, Wyden launch bipartisan investigation into insulin prices. United States Senate Committee on Finance website. www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/grassley-wyden-launch-bipartisan-investigation-into-insulin-prices. Published February 22, 2019. Accessed August 16, 2019.

2. BD Ultra-Fine. Syringe. GoodRx website. www.goodrx.com/bd-ultra-fine?dosage=31-gauge-5-16%22-of-1-cc&form=syringe&label_override=BD+Ultra-Fine&quantity=100. Accessed August 16, 2019.

3. BD Ultra-Fine. Pen needle. GoodRx website. www.goodrx.com/bd-ultra-fine?dosage=5-32%22-of-32-gauge&form=pen-needle&label_override=BD+Ultra-Fine&quantity=100. Accessed August 16, 2019.

4. Joffee D. Stability of common insulins in pens and vials. Diabetes in Control website. www.diabetesincontrol.com/wp-content/uploads/PDF/se_insulin_stability_chart.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed August 16, 2019.

5. Frequently asked questions. Preferred home delivery program for maintenance medications. Express Scripts website. www.express-scripts.com/art/pdf/SST-custom-preferred-faq.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

6. Patient Connection. Sanofi Patient Connection website. www.sanofipatientconnection.com/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

7. The Lilly Cares Foundation Patient Assistance Program. Lilly website. www.lillycares.com/assistanceprograms.aspx. Accessed August 16, 2019.

8. Novo Nordisk Patient Assistance Program. NovoCare website. www.novocare.com/psp/PAP.html. Accessed August 16, 2019.

9. 6 ways to get help with prescription costs. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap/6-ways-to-get-help-with-prescription-costs. Accessed August 16, 2019.

10. Pharmaceutical assistance program. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/pharmaceutical-assistance-program/Index.aspx. Accessed August 16, 2019.

11. Catastrophic coverage. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/catastrophic-coverage. Accessed August 16, 2019.

12. Costs in the coverage gap. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap. Accessed August 16, 2019.

13. V-Go Reimbursement Assistance Program. V-Go website. www.go-vgo.com/coverage-savings/overview/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

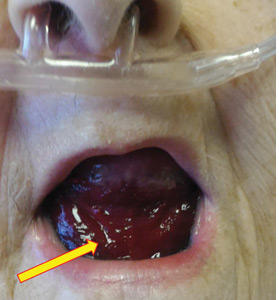

Pseudo-Ludwig angina

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

Click for Credit: Fasting rules for surgery; Biomarkers for PSA vs OA; more

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

High-dose vitamin D for bone health may do more harm than good

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.