User login

Helping teens make the switch from pediatrics to gynecology

For many adolescents, the first visit to a gynecologist can be intimidating. The prospect of meeting a new doctor who will ask prying, deeply personal questions about sex and menstruation is scary. And, in all likelihood, a parent, older sibling, or friend has warned them about the notorious pelvic exam.

The exact timing of when adolescent patients should start seeing a gynecologist varies based on when a patient starts puberty. Primary care physicians and pediatricians can help teens transition by referring patients to an adolescent-friendly practice and clearing up some of the misconceptions that surround the first gynecology visit. Gynecologists, on the other side of the referral, can help patients transition by guaranteeing confidentiality and creating a safe space for young patients.

This news organization interviewed three experts in adolescent health about when teens should start having their gynecological needs addressed and how their physicians can help them undergo that transition.

Age-appropriate care

“Most people get very limited information about their reproductive health,” said Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Seattle Children’s, Seattle, and a member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical consensus committee on gynecology.

Official guidelines from ACOG call for the initial reproductive health visit to take place between the ages of 13 and 15 years. The exact age may vary, however, depending on the specific needs of the patient.

For example, some patients begin menstruating early, at age 9 or 10, said Mary Romano, MD, MPH, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, Nashville, Tenn. Pediatricians who are uncomfortable educating young patients about menstruation should refer the patient to a gynecologist or a pediatric gynecologist for whom such discussions are routine.

If a patient does not have a menstrual cycle by age 14 or 15, that also should be addressed by a family physician or gynecologist, Dr. Romano added.

“The importance here is addressing the reproductive health of the teen starting really at the age of 10 or 12, or once puberty starts,” said Patricia S. Huguelet, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. In those early visits, the physician can provide “anticipatory guidance,” counseling the teen on what is normal in terms of menstruation, sex, and relationships, and addressing what is not, she said.

Ideally, patients who were designated female at birth but now identify as male or nonbinary will meet with a gynecologist early on in the gender affirmation process and a gynecologist will continue to consult as part of the patient’s interdisciplinary care team, added Dr. Romano, who counsels LGBTQ+ youth as part of her practice. A gynecologist may support these patients in myriad ways, including helping those who are considering or using puberty blockers and providing reproductive and health education to patients in a way that is sensitive to the patient’s gender identity.

Patient referrals

Some pediatricians and family practice physicians may be talking with their patients about topics such as menstrual cycles and contraception. But those who are uncomfortable asking adolescent patients about their reproductive and sexual health should refer them to a gynecologist or specialist in adolescent medicine, Dr. Romano advised.

“The biggest benefit I’ve noticed is often [patients] come from a pediatrician or family medicine provider and they often appreciate the opportunity to talk to a doctor they haven’t met before about the more personal questions they may have,” Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Referring adolescents to a specialist who has either trained in adolescent medicine or has experience treating that age group has benefits, Dr. Romano said. Clinicians with that experience understand adolescents are not “mini-adults” but have unique developmental and medical issues. How to counsel and educate them carries unique challenges, she said.

For example, heavy menstrual bleeding is a leading reason a patient – either an adult or an adolescent – presents to a gynecologist, Dr. Huguelet said. But the pathology differs vastly for those two age groups. For patients in their 30s and 40s, polyps and fibroids are common problems associated with heavy bleeding. Those conditions are rare in adolescents, whereas bleeding disorders are common, she said.

Most patients will continue to see their pediatricians and primary care providers for other issues. And in some areas, gynecologists can reinforce advice from pediatricians, such as encouraging patients to get the HPV vaccine, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Common misconceptions

Primary care physicians can also dispel common misconceptions teens – and their parents – have about gynecology. Some parents may believe that certain methods of birth control cause cancer or infertility, have concerns about the HPV vaccine, or think hormonal therapies are harmful, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said. But the biggest misconception involves the infamous pelvic exam.

“Lots of patients assume that every time they go to the gynecologist they are going to have a pelvic exam,” she said. “When I say, ‘We don’t have to do that,’ they are so relieved.”

Guidelines have changed since the parents of today’s teens were going to the gynecologist for the first time. Many patients now do not need an initial Pap smear until age 25, following a recent guideline change by the American Cancer Society. (ACOG is considering adopting the same stance but still recommends screening start at 21.) “Most patients do not need an exam, even when it comes to sexual health and screening [for sexually transmitted infections], that can be done without an exam,” Dr. Huguelet said.

Confidentiality and comfort

On the other side of the referral, gynecologists should follow several best practices to treat adolescent patients. Arguably the most important part of the initial gynecologic visit is to give patients the option of one-on-one time with the physician with no parent in the room. During that time, the physician should make it clear that what they discuss is confidential and will not be shared with their parent or guardian, Dr. Huguelet said. Patients should also have the option of having a friend or another nonparent individual in the room with them during this one-on-one time with the physician, particularly if the patient does not feel comfortable discussing sensitive subjects completely on her own.

Adolescents receive better care, disclose more, and perceive they are getting better care when the process is confidential, Dr. Romano said. Confidentiality does have limits, however, which physicians should also make sure their patients understand, according to the ACOG guidelines for the initial reproductive visit. These limitations can vary by state depending on issues related to mandatory reporting, insurance billing, and legal requirements of patient notifications of specific services such as abortion.

The use of electronic medical records has raised additional challenges when it comes to communicating privately with adolescent patients, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said. In her practice, she tries to ensure the adolescent is the one with the login information for their records. If not, her office will have the patient’s cell number to text or call securely.

“We feel strongly adolescents should be able to access reproductive health care, mental health care, and care for substance abuse disorders without parental notification,” Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Telehealth visits can also be helpful for adolescents coming to gynecology for the first time. And taking the time to establish a rapport with patients at the start of the visit is key, Dr. Huguelet said. By directing questions to the adolescent patient rather than the parent, Dr. Huguelet said, the physician demonstrates that the teen’s treatment needs come first.

ACOG has guidelines on other steps gynecology practices, including those that see both adults and teens, can take to make their offices and visits adolescent-friendly. These steps include asking patients about their preferred names and pronouns at the start of the visit or as part of the initial intake form, training office staff to be comfortable with issues related to adolescent sexuality and gender and sexual diversity among patients, providing a place for teens to wait separately from obstetrics patients, and having age-appropriate literature on hand for adolescents to learn about reproductive health.

After that first reproductive health visit, gynecologists and primary care providers should partner to ensure the whole health of their patients is being addressed, Dr. Huguelet said.

“Collaboration is always going to better serve patients in any area,” said Dr. Romano, “and certainly this area is no different.”

Dr. Amies Oelschlager, Dr. Romano, and Dr. Huguelet have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For many adolescents, the first visit to a gynecologist can be intimidating. The prospect of meeting a new doctor who will ask prying, deeply personal questions about sex and menstruation is scary. And, in all likelihood, a parent, older sibling, or friend has warned them about the notorious pelvic exam.

The exact timing of when adolescent patients should start seeing a gynecologist varies based on when a patient starts puberty. Primary care physicians and pediatricians can help teens transition by referring patients to an adolescent-friendly practice and clearing up some of the misconceptions that surround the first gynecology visit. Gynecologists, on the other side of the referral, can help patients transition by guaranteeing confidentiality and creating a safe space for young patients.

This news organization interviewed three experts in adolescent health about when teens should start having their gynecological needs addressed and how their physicians can help them undergo that transition.

Age-appropriate care

“Most people get very limited information about their reproductive health,” said Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Seattle Children’s, Seattle, and a member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical consensus committee on gynecology.

Official guidelines from ACOG call for the initial reproductive health visit to take place between the ages of 13 and 15 years. The exact age may vary, however, depending on the specific needs of the patient.

For example, some patients begin menstruating early, at age 9 or 10, said Mary Romano, MD, MPH, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, Nashville, Tenn. Pediatricians who are uncomfortable educating young patients about menstruation should refer the patient to a gynecologist or a pediatric gynecologist for whom such discussions are routine.

If a patient does not have a menstrual cycle by age 14 or 15, that also should be addressed by a family physician or gynecologist, Dr. Romano added.

“The importance here is addressing the reproductive health of the teen starting really at the age of 10 or 12, or once puberty starts,” said Patricia S. Huguelet, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. In those early visits, the physician can provide “anticipatory guidance,” counseling the teen on what is normal in terms of menstruation, sex, and relationships, and addressing what is not, she said.

Ideally, patients who were designated female at birth but now identify as male or nonbinary will meet with a gynecologist early on in the gender affirmation process and a gynecologist will continue to consult as part of the patient’s interdisciplinary care team, added Dr. Romano, who counsels LGBTQ+ youth as part of her practice. A gynecologist may support these patients in myriad ways, including helping those who are considering or using puberty blockers and providing reproductive and health education to patients in a way that is sensitive to the patient’s gender identity.

Patient referrals

Some pediatricians and family practice physicians may be talking with their patients about topics such as menstrual cycles and contraception. But those who are uncomfortable asking adolescent patients about their reproductive and sexual health should refer them to a gynecologist or specialist in adolescent medicine, Dr. Romano advised.

“The biggest benefit I’ve noticed is often [patients] come from a pediatrician or family medicine provider and they often appreciate the opportunity to talk to a doctor they haven’t met before about the more personal questions they may have,” Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Referring adolescents to a specialist who has either trained in adolescent medicine or has experience treating that age group has benefits, Dr. Romano said. Clinicians with that experience understand adolescents are not “mini-adults” but have unique developmental and medical issues. How to counsel and educate them carries unique challenges, she said.

For example, heavy menstrual bleeding is a leading reason a patient – either an adult or an adolescent – presents to a gynecologist, Dr. Huguelet said. But the pathology differs vastly for those two age groups. For patients in their 30s and 40s, polyps and fibroids are common problems associated with heavy bleeding. Those conditions are rare in adolescents, whereas bleeding disorders are common, she said.

Most patients will continue to see their pediatricians and primary care providers for other issues. And in some areas, gynecologists can reinforce advice from pediatricians, such as encouraging patients to get the HPV vaccine, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Common misconceptions

Primary care physicians can also dispel common misconceptions teens – and their parents – have about gynecology. Some parents may believe that certain methods of birth control cause cancer or infertility, have concerns about the HPV vaccine, or think hormonal therapies are harmful, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said. But the biggest misconception involves the infamous pelvic exam.

“Lots of patients assume that every time they go to the gynecologist they are going to have a pelvic exam,” she said. “When I say, ‘We don’t have to do that,’ they are so relieved.”

Guidelines have changed since the parents of today’s teens were going to the gynecologist for the first time. Many patients now do not need an initial Pap smear until age 25, following a recent guideline change by the American Cancer Society. (ACOG is considering adopting the same stance but still recommends screening start at 21.) “Most patients do not need an exam, even when it comes to sexual health and screening [for sexually transmitted infections], that can be done without an exam,” Dr. Huguelet said.

Confidentiality and comfort

On the other side of the referral, gynecologists should follow several best practices to treat adolescent patients. Arguably the most important part of the initial gynecologic visit is to give patients the option of one-on-one time with the physician with no parent in the room. During that time, the physician should make it clear that what they discuss is confidential and will not be shared with their parent or guardian, Dr. Huguelet said. Patients should also have the option of having a friend or another nonparent individual in the room with them during this one-on-one time with the physician, particularly if the patient does not feel comfortable discussing sensitive subjects completely on her own.

Adolescents receive better care, disclose more, and perceive they are getting better care when the process is confidential, Dr. Romano said. Confidentiality does have limits, however, which physicians should also make sure their patients understand, according to the ACOG guidelines for the initial reproductive visit. These limitations can vary by state depending on issues related to mandatory reporting, insurance billing, and legal requirements of patient notifications of specific services such as abortion.

The use of electronic medical records has raised additional challenges when it comes to communicating privately with adolescent patients, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said. In her practice, she tries to ensure the adolescent is the one with the login information for their records. If not, her office will have the patient’s cell number to text or call securely.

“We feel strongly adolescents should be able to access reproductive health care, mental health care, and care for substance abuse disorders without parental notification,” Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Telehealth visits can also be helpful for adolescents coming to gynecology for the first time. And taking the time to establish a rapport with patients at the start of the visit is key, Dr. Huguelet said. By directing questions to the adolescent patient rather than the parent, Dr. Huguelet said, the physician demonstrates that the teen’s treatment needs come first.

ACOG has guidelines on other steps gynecology practices, including those that see both adults and teens, can take to make their offices and visits adolescent-friendly. These steps include asking patients about their preferred names and pronouns at the start of the visit or as part of the initial intake form, training office staff to be comfortable with issues related to adolescent sexuality and gender and sexual diversity among patients, providing a place for teens to wait separately from obstetrics patients, and having age-appropriate literature on hand for adolescents to learn about reproductive health.

After that first reproductive health visit, gynecologists and primary care providers should partner to ensure the whole health of their patients is being addressed, Dr. Huguelet said.

“Collaboration is always going to better serve patients in any area,” said Dr. Romano, “and certainly this area is no different.”

Dr. Amies Oelschlager, Dr. Romano, and Dr. Huguelet have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For many adolescents, the first visit to a gynecologist can be intimidating. The prospect of meeting a new doctor who will ask prying, deeply personal questions about sex and menstruation is scary. And, in all likelihood, a parent, older sibling, or friend has warned them about the notorious pelvic exam.

The exact timing of when adolescent patients should start seeing a gynecologist varies based on when a patient starts puberty. Primary care physicians and pediatricians can help teens transition by referring patients to an adolescent-friendly practice and clearing up some of the misconceptions that surround the first gynecology visit. Gynecologists, on the other side of the referral, can help patients transition by guaranteeing confidentiality and creating a safe space for young patients.

This news organization interviewed three experts in adolescent health about when teens should start having their gynecological needs addressed and how their physicians can help them undergo that transition.

Age-appropriate care

“Most people get very limited information about their reproductive health,” said Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Seattle Children’s, Seattle, and a member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical consensus committee on gynecology.

Official guidelines from ACOG call for the initial reproductive health visit to take place between the ages of 13 and 15 years. The exact age may vary, however, depending on the specific needs of the patient.

For example, some patients begin menstruating early, at age 9 or 10, said Mary Romano, MD, MPH, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, Nashville, Tenn. Pediatricians who are uncomfortable educating young patients about menstruation should refer the patient to a gynecologist or a pediatric gynecologist for whom such discussions are routine.

If a patient does not have a menstrual cycle by age 14 or 15, that also should be addressed by a family physician or gynecologist, Dr. Romano added.

“The importance here is addressing the reproductive health of the teen starting really at the age of 10 or 12, or once puberty starts,” said Patricia S. Huguelet, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. In those early visits, the physician can provide “anticipatory guidance,” counseling the teen on what is normal in terms of menstruation, sex, and relationships, and addressing what is not, she said.

Ideally, patients who were designated female at birth but now identify as male or nonbinary will meet with a gynecologist early on in the gender affirmation process and a gynecologist will continue to consult as part of the patient’s interdisciplinary care team, added Dr. Romano, who counsels LGBTQ+ youth as part of her practice. A gynecologist may support these patients in myriad ways, including helping those who are considering or using puberty blockers and providing reproductive and health education to patients in a way that is sensitive to the patient’s gender identity.

Patient referrals

Some pediatricians and family practice physicians may be talking with their patients about topics such as menstrual cycles and contraception. But those who are uncomfortable asking adolescent patients about their reproductive and sexual health should refer them to a gynecologist or specialist in adolescent medicine, Dr. Romano advised.

“The biggest benefit I’ve noticed is often [patients] come from a pediatrician or family medicine provider and they often appreciate the opportunity to talk to a doctor they haven’t met before about the more personal questions they may have,” Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Referring adolescents to a specialist who has either trained in adolescent medicine or has experience treating that age group has benefits, Dr. Romano said. Clinicians with that experience understand adolescents are not “mini-adults” but have unique developmental and medical issues. How to counsel and educate them carries unique challenges, she said.

For example, heavy menstrual bleeding is a leading reason a patient – either an adult or an adolescent – presents to a gynecologist, Dr. Huguelet said. But the pathology differs vastly for those two age groups. For patients in their 30s and 40s, polyps and fibroids are common problems associated with heavy bleeding. Those conditions are rare in adolescents, whereas bleeding disorders are common, she said.

Most patients will continue to see their pediatricians and primary care providers for other issues. And in some areas, gynecologists can reinforce advice from pediatricians, such as encouraging patients to get the HPV vaccine, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Common misconceptions

Primary care physicians can also dispel common misconceptions teens – and their parents – have about gynecology. Some parents may believe that certain methods of birth control cause cancer or infertility, have concerns about the HPV vaccine, or think hormonal therapies are harmful, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said. But the biggest misconception involves the infamous pelvic exam.

“Lots of patients assume that every time they go to the gynecologist they are going to have a pelvic exam,” she said. “When I say, ‘We don’t have to do that,’ they are so relieved.”

Guidelines have changed since the parents of today’s teens were going to the gynecologist for the first time. Many patients now do not need an initial Pap smear until age 25, following a recent guideline change by the American Cancer Society. (ACOG is considering adopting the same stance but still recommends screening start at 21.) “Most patients do not need an exam, even when it comes to sexual health and screening [for sexually transmitted infections], that can be done without an exam,” Dr. Huguelet said.

Confidentiality and comfort

On the other side of the referral, gynecologists should follow several best practices to treat adolescent patients. Arguably the most important part of the initial gynecologic visit is to give patients the option of one-on-one time with the physician with no parent in the room. During that time, the physician should make it clear that what they discuss is confidential and will not be shared with their parent or guardian, Dr. Huguelet said. Patients should also have the option of having a friend or another nonparent individual in the room with them during this one-on-one time with the physician, particularly if the patient does not feel comfortable discussing sensitive subjects completely on her own.

Adolescents receive better care, disclose more, and perceive they are getting better care when the process is confidential, Dr. Romano said. Confidentiality does have limits, however, which physicians should also make sure their patients understand, according to the ACOG guidelines for the initial reproductive visit. These limitations can vary by state depending on issues related to mandatory reporting, insurance billing, and legal requirements of patient notifications of specific services such as abortion.

The use of electronic medical records has raised additional challenges when it comes to communicating privately with adolescent patients, Dr. Amies Oelschlager said. In her practice, she tries to ensure the adolescent is the one with the login information for their records. If not, her office will have the patient’s cell number to text or call securely.

“We feel strongly adolescents should be able to access reproductive health care, mental health care, and care for substance abuse disorders without parental notification,” Dr. Amies Oelschlager said.

Telehealth visits can also be helpful for adolescents coming to gynecology for the first time. And taking the time to establish a rapport with patients at the start of the visit is key, Dr. Huguelet said. By directing questions to the adolescent patient rather than the parent, Dr. Huguelet said, the physician demonstrates that the teen’s treatment needs come first.

ACOG has guidelines on other steps gynecology practices, including those that see both adults and teens, can take to make their offices and visits adolescent-friendly. These steps include asking patients about their preferred names and pronouns at the start of the visit or as part of the initial intake form, training office staff to be comfortable with issues related to adolescent sexuality and gender and sexual diversity among patients, providing a place for teens to wait separately from obstetrics patients, and having age-appropriate literature on hand for adolescents to learn about reproductive health.

After that first reproductive health visit, gynecologists and primary care providers should partner to ensure the whole health of their patients is being addressed, Dr. Huguelet said.

“Collaboration is always going to better serve patients in any area,” said Dr. Romano, “and certainly this area is no different.”

Dr. Amies Oelschlager, Dr. Romano, and Dr. Huguelet have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tech can help teens connect with docs about sexual health

Maria Trent, MD, MPH, was studying ways clinicians can leverage technology to care for adolescents years before COVID-19 exposed the challenges and advantages of telehealth.

Dr. Trent, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist and professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, has long believed that the phones in her patients’ pockets have the potential to improve the sexual health of youth. The pandemic has only made that view stronger.

“They’re a generation that’s really wired and online,” Dr. Trent told this news organization. “I think that we can meet them in that space.”

Her research has incorporated texting, apps, and videos. Out of necessity, technology increasingly became part of patient care during the pandemic. “We had to stretch our ability to do some basic triage and assessments of patients online,” Dr. Trent said.

Even when clinics are closed, doctors might be able to provide initial care remotely, such as writing prescriptions to manage symptoms or directing patients to a lab for testing.

Telemedicine could allow a clinician to guide a teenager who thinks they might be pregnant to take a store-bought test and avoid possible exposure to COVID-19 in the ED, for instance.

But doctors have concerns about the legal and practical limits of privacy and confidentiality. Who else is at home listening to a phone conversation? Are parents accessing the patient’s online portal? Will parents receive an explanation of benefits that lists testing for a sexually transmitted infection, or see a testing kit that is delivered to their home?

When a young patient needs in-person care, transportation can be a barrier. And then there’s the matter of clinicians being able to bill for telehealth services.

Practices are learning how to navigate these issues, and relevant laws vary by state.

“I think this is going to become part of standard practice,” Dr. Trent said. “I think we have to do the hard work to make sure that it’s safe, that it’s accessible, and that it is actually improving care.”

Texts, apps, videos

In one early study, Dr. Trent and colleagues found that showing adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease a 6-minute video may improve treatment rates for their sexual partners.

Another study provided preliminary evidence that text messaging support might improve clinic attendance for moderately long-acting reversible contraception.

A third trial showed that adolescents and young adults with pelvic inflammatory disease who were randomly assigned to receive text-message prompts to take their medications and provide information about the doses they consumed had greater decreases in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections, compared with patients who received standard care.

Dr. Trent and coinvestigators are assessing a technology-based intervention for youth with HIV, in which patients can use an app to submit videos of themselves taking antiretroviral therapy and report any side effects. The technology provides a way to monitor patients remotely and support them between visits, she said.

Will pandemic-driven options remain?

In 2020, Laura D. Lindberg, PhD, principal research scientist at the Guttmacher Institute in New York, and coauthors discussed the possible ramifications of the pandemic on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults.

If telemedicine options driven by COVID-19 are here to stay, adolescents and young adults could be “the age group most likely to continue that approach rather than returning to traditional in-person visits,” the researchers wrote. “Innovations in health care service provision, such as use of telemedicine and obtaining contraceptives and STI testing by mail, will help expand access to [sexual and reproductive health] care for young people.”

At the 2021 annual conference of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Trent described telehealth as a viable way to provide sexual and reproductive health care to adolescents and young adults, including anticipatory guidance, contraception counseling, coordination of follow-up care and testing, and connecting patients to resources.

Her presentation cited several websites that can help patients receive testing for STIs, including Yes Means Test, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s GetTested page, and I Want the Kit. Planned Parenthood has telehealth options, and the Kaiser Family Foundation compiled information about 26 online platforms that were providing contraception or STI services.

Who else is in the room?

“There’s only so much time in the day and so many patients you can see, regardless of whether you have telehealth or not,” said David L. Bell, MD, MPH, president of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine and a coauthor of the Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health paper. In addition, “you never know who else is in the room” with the patient on the other end, added Dr. Bell, a professor of population and family health and pediatrics at the Columbia University Medical Center and medical director of the Young Men’s Clinic, both in New York.

In some respects, young patients may not be able to participate in telehealth visits the same way they would in a medical office, Dr. Trent acknowledged. Encouraging the use of headphones is one way to help protect confidentiality when talking with patients who are at home and might not be alone.

But if patients are able to find a private space for remote visits, they might be more open than usual. In that way, telemedicine could provide additional opportunities to address issues like substance use disorders and mental health, as well, she said.

“Then, if they need something, we have to problem solve,” Dr. Trent said. Next steps may involve engaging a parent or getting the patient to a lab or the clinic.

Sex ed may be lacking

The Perspectives article also raised concerns that the pandemic might exacerbate shortcomings in sex education, which already may have been lacking.

“Before the pandemic, schools were a key source of formal sex education for young people,” the authors wrote. “Sex education, which was already limited in many areas of the country, has likely not been included in the national shift to online learning. Even when in-person schooling resumes, missed sex education instruction is unlikely to be made up, given the modest attention it received prior to the pandemic.”

A recently published study in the Journal of Adolescent Health indicates that American teenagers currently receive less formal sex education than they did 25 years ago, with “troubling” inequities by race.

Researchers surveyed adolescents about what they had learned about topics such as how to say no to sex, methods of birth control and where to get them, and STIs.

Dr. Lindberg and Leslie M. Kantor, PhD, MPH, professor and chair of the department of urban-global public health at Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., conducted the analysis.

“Pediatricians and other health care providers that work with children and adolescents have a critical role to play in providing information about sexuality to both the patients and to the parents,” said Dr. Kantor, who also coauthored the Perspectives article with Dr. Lindberg and Dr. Bell. The new research “shows that doctors play an even more critical role, because they can’t assume that their patients are going to get the information that they need in a timely way from schools.”

By age 15, 21% of girls and 20% of boys have had sexual intercourse at least once, according to data from the 2015-2017 National Survey of Family Growth. By age 17, the percentages were 53% of girls and 48% of boys. By age 20, the percentages were 79% of women and 77% of men. The CDC’s 2021 guidelines on treatment and screening for STIs note that prevalence rates of certain infections – such as chlamydia and gonorrhea in females – are highest among adolescents and young adults.

Those trends underscore the importance of counseling on sexual health that clinicians can provide, but time constraints may limit how much they can discuss in a single session with a patient. To cover all topics that are important to parents and patients, doctors may need to discuss sexual and reproductive health sooner and more frequently.

Young people are getting more and more explicit information from their phones and media, yet educators are giving them less information to navigate these topics and learn what’s real, Dr. Kantor said. That mismatch can be toxic. In a December 2021 interview with Howard Stern, the pop star Billie Eilish said she started watching pornography at about age 11 and frequently watched videos that were violent. “I think it really destroyed my brain and I feel incredibly devastated that I was exposed to so much porn,” Ms. Eilish told Mr. Stern.

Researchers and a psychologist told CNN that the singer’s story may be typical. It also highlights a need to be aware of kids’ online activities and to have conversations about how pornography may not depict healthy interactions, they said.

Beyond discussing a plan for preventing pregnancy and STIs, Dr. Kantor encouraged discussions about what constitutes healthy relationships, as well as check-ins about intimate partner violence and how romantic relationships are going.

“I think for pediatricians and for parents, it’s a muscle,” she said. “As you bring up these topics more, listen, and respond, you get more comfortable with it.”

Dr. Trent has served as an advisory board member on a sexual health council for Trojan (Church & Dwight Company) and has received research funding from Hologic and research supplies from SpeeDx. Dr. Bell has received funds from the Merck Foundation, Merck, and Gilead. Dr. Kantor had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maria Trent, MD, MPH, was studying ways clinicians can leverage technology to care for adolescents years before COVID-19 exposed the challenges and advantages of telehealth.

Dr. Trent, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist and professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, has long believed that the phones in her patients’ pockets have the potential to improve the sexual health of youth. The pandemic has only made that view stronger.

“They’re a generation that’s really wired and online,” Dr. Trent told this news organization. “I think that we can meet them in that space.”

Her research has incorporated texting, apps, and videos. Out of necessity, technology increasingly became part of patient care during the pandemic. “We had to stretch our ability to do some basic triage and assessments of patients online,” Dr. Trent said.

Even when clinics are closed, doctors might be able to provide initial care remotely, such as writing prescriptions to manage symptoms or directing patients to a lab for testing.

Telemedicine could allow a clinician to guide a teenager who thinks they might be pregnant to take a store-bought test and avoid possible exposure to COVID-19 in the ED, for instance.

But doctors have concerns about the legal and practical limits of privacy and confidentiality. Who else is at home listening to a phone conversation? Are parents accessing the patient’s online portal? Will parents receive an explanation of benefits that lists testing for a sexually transmitted infection, or see a testing kit that is delivered to their home?

When a young patient needs in-person care, transportation can be a barrier. And then there’s the matter of clinicians being able to bill for telehealth services.

Practices are learning how to navigate these issues, and relevant laws vary by state.

“I think this is going to become part of standard practice,” Dr. Trent said. “I think we have to do the hard work to make sure that it’s safe, that it’s accessible, and that it is actually improving care.”

Texts, apps, videos

In one early study, Dr. Trent and colleagues found that showing adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease a 6-minute video may improve treatment rates for their sexual partners.

Another study provided preliminary evidence that text messaging support might improve clinic attendance for moderately long-acting reversible contraception.

A third trial showed that adolescents and young adults with pelvic inflammatory disease who were randomly assigned to receive text-message prompts to take their medications and provide information about the doses they consumed had greater decreases in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections, compared with patients who received standard care.

Dr. Trent and coinvestigators are assessing a technology-based intervention for youth with HIV, in which patients can use an app to submit videos of themselves taking antiretroviral therapy and report any side effects. The technology provides a way to monitor patients remotely and support them between visits, she said.

Will pandemic-driven options remain?

In 2020, Laura D. Lindberg, PhD, principal research scientist at the Guttmacher Institute in New York, and coauthors discussed the possible ramifications of the pandemic on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults.

If telemedicine options driven by COVID-19 are here to stay, adolescents and young adults could be “the age group most likely to continue that approach rather than returning to traditional in-person visits,” the researchers wrote. “Innovations in health care service provision, such as use of telemedicine and obtaining contraceptives and STI testing by mail, will help expand access to [sexual and reproductive health] care for young people.”

At the 2021 annual conference of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Trent described telehealth as a viable way to provide sexual and reproductive health care to adolescents and young adults, including anticipatory guidance, contraception counseling, coordination of follow-up care and testing, and connecting patients to resources.

Her presentation cited several websites that can help patients receive testing for STIs, including Yes Means Test, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s GetTested page, and I Want the Kit. Planned Parenthood has telehealth options, and the Kaiser Family Foundation compiled information about 26 online platforms that were providing contraception or STI services.

Who else is in the room?

“There’s only so much time in the day and so many patients you can see, regardless of whether you have telehealth or not,” said David L. Bell, MD, MPH, president of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine and a coauthor of the Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health paper. In addition, “you never know who else is in the room” with the patient on the other end, added Dr. Bell, a professor of population and family health and pediatrics at the Columbia University Medical Center and medical director of the Young Men’s Clinic, both in New York.

In some respects, young patients may not be able to participate in telehealth visits the same way they would in a medical office, Dr. Trent acknowledged. Encouraging the use of headphones is one way to help protect confidentiality when talking with patients who are at home and might not be alone.

But if patients are able to find a private space for remote visits, they might be more open than usual. In that way, telemedicine could provide additional opportunities to address issues like substance use disorders and mental health, as well, she said.

“Then, if they need something, we have to problem solve,” Dr. Trent said. Next steps may involve engaging a parent or getting the patient to a lab or the clinic.

Sex ed may be lacking

The Perspectives article also raised concerns that the pandemic might exacerbate shortcomings in sex education, which already may have been lacking.

“Before the pandemic, schools were a key source of formal sex education for young people,” the authors wrote. “Sex education, which was already limited in many areas of the country, has likely not been included in the national shift to online learning. Even when in-person schooling resumes, missed sex education instruction is unlikely to be made up, given the modest attention it received prior to the pandemic.”

A recently published study in the Journal of Adolescent Health indicates that American teenagers currently receive less formal sex education than they did 25 years ago, with “troubling” inequities by race.

Researchers surveyed adolescents about what they had learned about topics such as how to say no to sex, methods of birth control and where to get them, and STIs.

Dr. Lindberg and Leslie M. Kantor, PhD, MPH, professor and chair of the department of urban-global public health at Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., conducted the analysis.

“Pediatricians and other health care providers that work with children and adolescents have a critical role to play in providing information about sexuality to both the patients and to the parents,” said Dr. Kantor, who also coauthored the Perspectives article with Dr. Lindberg and Dr. Bell. The new research “shows that doctors play an even more critical role, because they can’t assume that their patients are going to get the information that they need in a timely way from schools.”

By age 15, 21% of girls and 20% of boys have had sexual intercourse at least once, according to data from the 2015-2017 National Survey of Family Growth. By age 17, the percentages were 53% of girls and 48% of boys. By age 20, the percentages were 79% of women and 77% of men. The CDC’s 2021 guidelines on treatment and screening for STIs note that prevalence rates of certain infections – such as chlamydia and gonorrhea in females – are highest among adolescents and young adults.

Those trends underscore the importance of counseling on sexual health that clinicians can provide, but time constraints may limit how much they can discuss in a single session with a patient. To cover all topics that are important to parents and patients, doctors may need to discuss sexual and reproductive health sooner and more frequently.

Young people are getting more and more explicit information from their phones and media, yet educators are giving them less information to navigate these topics and learn what’s real, Dr. Kantor said. That mismatch can be toxic. In a December 2021 interview with Howard Stern, the pop star Billie Eilish said she started watching pornography at about age 11 and frequently watched videos that were violent. “I think it really destroyed my brain and I feel incredibly devastated that I was exposed to so much porn,” Ms. Eilish told Mr. Stern.

Researchers and a psychologist told CNN that the singer’s story may be typical. It also highlights a need to be aware of kids’ online activities and to have conversations about how pornography may not depict healthy interactions, they said.

Beyond discussing a plan for preventing pregnancy and STIs, Dr. Kantor encouraged discussions about what constitutes healthy relationships, as well as check-ins about intimate partner violence and how romantic relationships are going.

“I think for pediatricians and for parents, it’s a muscle,” she said. “As you bring up these topics more, listen, and respond, you get more comfortable with it.”

Dr. Trent has served as an advisory board member on a sexual health council for Trojan (Church & Dwight Company) and has received research funding from Hologic and research supplies from SpeeDx. Dr. Bell has received funds from the Merck Foundation, Merck, and Gilead. Dr. Kantor had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maria Trent, MD, MPH, was studying ways clinicians can leverage technology to care for adolescents years before COVID-19 exposed the challenges and advantages of telehealth.

Dr. Trent, a pediatrician and adolescent medicine specialist and professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, has long believed that the phones in her patients’ pockets have the potential to improve the sexual health of youth. The pandemic has only made that view stronger.

“They’re a generation that’s really wired and online,” Dr. Trent told this news organization. “I think that we can meet them in that space.”

Her research has incorporated texting, apps, and videos. Out of necessity, technology increasingly became part of patient care during the pandemic. “We had to stretch our ability to do some basic triage and assessments of patients online,” Dr. Trent said.

Even when clinics are closed, doctors might be able to provide initial care remotely, such as writing prescriptions to manage symptoms or directing patients to a lab for testing.

Telemedicine could allow a clinician to guide a teenager who thinks they might be pregnant to take a store-bought test and avoid possible exposure to COVID-19 in the ED, for instance.

But doctors have concerns about the legal and practical limits of privacy and confidentiality. Who else is at home listening to a phone conversation? Are parents accessing the patient’s online portal? Will parents receive an explanation of benefits that lists testing for a sexually transmitted infection, or see a testing kit that is delivered to their home?

When a young patient needs in-person care, transportation can be a barrier. And then there’s the matter of clinicians being able to bill for telehealth services.

Practices are learning how to navigate these issues, and relevant laws vary by state.

“I think this is going to become part of standard practice,” Dr. Trent said. “I think we have to do the hard work to make sure that it’s safe, that it’s accessible, and that it is actually improving care.”

Texts, apps, videos

In one early study, Dr. Trent and colleagues found that showing adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease a 6-minute video may improve treatment rates for their sexual partners.

Another study provided preliminary evidence that text messaging support might improve clinic attendance for moderately long-acting reversible contraception.

A third trial showed that adolescents and young adults with pelvic inflammatory disease who were randomly assigned to receive text-message prompts to take their medications and provide information about the doses they consumed had greater decreases in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections, compared with patients who received standard care.

Dr. Trent and coinvestigators are assessing a technology-based intervention for youth with HIV, in which patients can use an app to submit videos of themselves taking antiretroviral therapy and report any side effects. The technology provides a way to monitor patients remotely and support them between visits, she said.

Will pandemic-driven options remain?

In 2020, Laura D. Lindberg, PhD, principal research scientist at the Guttmacher Institute in New York, and coauthors discussed the possible ramifications of the pandemic on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults.

If telemedicine options driven by COVID-19 are here to stay, adolescents and young adults could be “the age group most likely to continue that approach rather than returning to traditional in-person visits,” the researchers wrote. “Innovations in health care service provision, such as use of telemedicine and obtaining contraceptives and STI testing by mail, will help expand access to [sexual and reproductive health] care for young people.”

At the 2021 annual conference of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Trent described telehealth as a viable way to provide sexual and reproductive health care to adolescents and young adults, including anticipatory guidance, contraception counseling, coordination of follow-up care and testing, and connecting patients to resources.

Her presentation cited several websites that can help patients receive testing for STIs, including Yes Means Test, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s GetTested page, and I Want the Kit. Planned Parenthood has telehealth options, and the Kaiser Family Foundation compiled information about 26 online platforms that were providing contraception or STI services.

Who else is in the room?

“There’s only so much time in the day and so many patients you can see, regardless of whether you have telehealth or not,” said David L. Bell, MD, MPH, president of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine and a coauthor of the Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health paper. In addition, “you never know who else is in the room” with the patient on the other end, added Dr. Bell, a professor of population and family health and pediatrics at the Columbia University Medical Center and medical director of the Young Men’s Clinic, both in New York.

In some respects, young patients may not be able to participate in telehealth visits the same way they would in a medical office, Dr. Trent acknowledged. Encouraging the use of headphones is one way to help protect confidentiality when talking with patients who are at home and might not be alone.

But if patients are able to find a private space for remote visits, they might be more open than usual. In that way, telemedicine could provide additional opportunities to address issues like substance use disorders and mental health, as well, she said.

“Then, if they need something, we have to problem solve,” Dr. Trent said. Next steps may involve engaging a parent or getting the patient to a lab or the clinic.

Sex ed may be lacking

The Perspectives article also raised concerns that the pandemic might exacerbate shortcomings in sex education, which already may have been lacking.

“Before the pandemic, schools were a key source of formal sex education for young people,” the authors wrote. “Sex education, which was already limited in many areas of the country, has likely not been included in the national shift to online learning. Even when in-person schooling resumes, missed sex education instruction is unlikely to be made up, given the modest attention it received prior to the pandemic.”

A recently published study in the Journal of Adolescent Health indicates that American teenagers currently receive less formal sex education than they did 25 years ago, with “troubling” inequities by race.

Researchers surveyed adolescents about what they had learned about topics such as how to say no to sex, methods of birth control and where to get them, and STIs.

Dr. Lindberg and Leslie M. Kantor, PhD, MPH, professor and chair of the department of urban-global public health at Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., conducted the analysis.

“Pediatricians and other health care providers that work with children and adolescents have a critical role to play in providing information about sexuality to both the patients and to the parents,” said Dr. Kantor, who also coauthored the Perspectives article with Dr. Lindberg and Dr. Bell. The new research “shows that doctors play an even more critical role, because they can’t assume that their patients are going to get the information that they need in a timely way from schools.”

By age 15, 21% of girls and 20% of boys have had sexual intercourse at least once, according to data from the 2015-2017 National Survey of Family Growth. By age 17, the percentages were 53% of girls and 48% of boys. By age 20, the percentages were 79% of women and 77% of men. The CDC’s 2021 guidelines on treatment and screening for STIs note that prevalence rates of certain infections – such as chlamydia and gonorrhea in females – are highest among adolescents and young adults.

Those trends underscore the importance of counseling on sexual health that clinicians can provide, but time constraints may limit how much they can discuss in a single session with a patient. To cover all topics that are important to parents and patients, doctors may need to discuss sexual and reproductive health sooner and more frequently.

Young people are getting more and more explicit information from their phones and media, yet educators are giving them less information to navigate these topics and learn what’s real, Dr. Kantor said. That mismatch can be toxic. In a December 2021 interview with Howard Stern, the pop star Billie Eilish said she started watching pornography at about age 11 and frequently watched videos that were violent. “I think it really destroyed my brain and I feel incredibly devastated that I was exposed to so much porn,” Ms. Eilish told Mr. Stern.

Researchers and a psychologist told CNN that the singer’s story may be typical. It also highlights a need to be aware of kids’ online activities and to have conversations about how pornography may not depict healthy interactions, they said.

Beyond discussing a plan for preventing pregnancy and STIs, Dr. Kantor encouraged discussions about what constitutes healthy relationships, as well as check-ins about intimate partner violence and how romantic relationships are going.

“I think for pediatricians and for parents, it’s a muscle,” she said. “As you bring up these topics more, listen, and respond, you get more comfortable with it.”

Dr. Trent has served as an advisory board member on a sexual health council for Trojan (Church & Dwight Company) and has received research funding from Hologic and research supplies from SpeeDx. Dr. Bell has received funds from the Merck Foundation, Merck, and Gilead. Dr. Kantor had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Average-risk women with dense breasts—What breast screening is appropriate?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

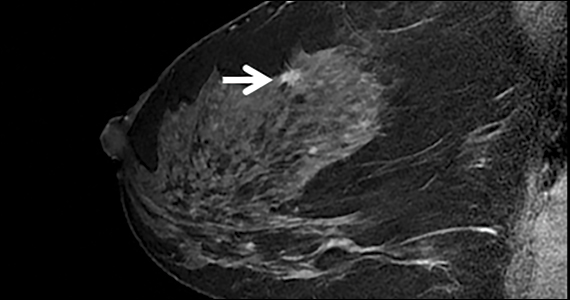

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.