User login

A patient with severe adenomyosis requests uterine-sparing surgery

CASE

A 28-year-old patient presents for evaluation and management of her chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia. She previously tried ibuprofen with no pain relief. She also tried oral and long-acting reversible contraceptives but continued to be symptomatic. She underwent pelvic sonography, which demonstrated a large globular uterus with myometrial thickening and myometrial cysts with increased hypervascularity. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging indicated a thickened junctional zone. Feeling she had exhausted medical manegement options with no significant improvement, she desired surgical treatment, but wanted to retain her future fertility. As a newlywed, she and her husband were planning on building a family so she desired to retain her uterus for potential future pregnancy.

How would you address this patient’s disruptive symptoms, while affirming her long-term plans by choosing the proper intervention?

Adenomyosis is characterized by endometrial-like glands and stroma deep within the myometrium of the uterus and generally is classified as diffuse or focal. This common, benign gynecologic condition is known to cause enlargement of the uterus secondary to stimulation of ectopic endometrial-like cells.1-3 Although the true incidence of adenomyosis is unknown because of the difficulty of making the diagnosis, prevalence has been variously reported at 6% to 70% among reproductive-aged women.4,5

In this review, we first examine the clinical presentation and diagnosis of adenomyosis. We then discuss clinical indications for, and surgical techniques of, adenomyomectomy, including our preferred uterine-sparing approach for focal disease or when the patient wants to preserve fertility: video laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when indicated.

Treatment evolved in a century and a half

Adenomyosis was first described more than 150 years ago; historically, hysterectomy was the mainstay of treatment.2,6 Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis has been reported since the early 1950s.6-8 Surgical treatment initially became more widespread following the introduction of wedge resection, which allowed for partial excision of adenomyotic nodules.9

More recent developments in diagnostic technologies and capabilities have allowed for the emergence of additional uterine-sparing and minimally invasive surgical treatment options for adenomyosis.3,10 Although the use of laparoscopic approaches is limited because a high level of technical skill is required to undertake these procedures, such approaches are becoming increasingly important as more and more patients seek fertility conservation.11-13

How does adenomyosis present?

Adenomyosis symptoms commonly consist of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea, affecting approximately 40% to 60% and 15% to 30% of patients with the condition, respectively.14 These symptoms are considered nonspecific because they are also associated with other uterine abnormalities.15 Although menorrhagia is not associated with extent of disease, dysmenorrhea is associated with both the number and depth of adenomyotic foci.14

Other symptoms reported with adenomyosis include chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, as well as infertility. Note, however, that a large percentage of patients are asymptomatic.16,17

On physical examination, patients commonly exhibit a diffusely enlarged, globular uterus. This finding is secondary to uniform hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the myometrium, caused by stimulation of ectopic endometrial cells.2 A subset of patients experience significant uterine tenderness.18 Other common findings associated with adenomyosis include uterine abnormalities, such as leiomyomata, endometriosis, and endometrial polyps.

Continue to: Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential...

Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential

Histology

Adenomyosis is definitively diagnosed based on histologic findings of endometrial-like tissue within the myometrium. Historically, histologic analysis was performed on specimens following hysterectomy but, more recently, has utilized specimens obtained from hysteroscopic and laparoscopic myometrial biopsies.19 Importantly, although hysteroscopic and laparoscopic biopsies are taken under direct visualization, there are no pathognomonic signs for adenomyosis; a diagnosis can therefore be missed if adenomyosis is not present at biopsied sites.1 The sensitivity of random biopsy at laparoscopy has been found to be as low as 2% to as high as 56%.20

Imaging

Imaging can be helpful in clinical decision making and to guide the differential diagnosis. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is often the first mode of imaging used for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding or pelvic pain. Diagnosis by TVUS is difficult because the modality is operator dependent and standard diagnostic criteria are lacking.5

The most commonly reported ultrasonographic features of adenomyosis are21,22:

- a globally enlarged uterus

- asymmetry

- myometrial thickening with heterogeneity

- poorly defined foci of hyperechoic regions, surrounded by hypoechoic areas that correspond to smooth-muscle hyperplasia

- myometrial cysts.

Doppler ultrasound examination in patients with adenomyosis reveals increased flow to the myometrium without evidence of large blood vessels.

3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasonography. Integration of 3-D ultrasonography has allowed for identification of the thicker junctional zone that suggests adenomyosis. In a systematic review of the accuracy of TVUS, investigators reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 2-dimensional ultrasonography of 83.8% and 63.9%, respectively, and a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 3-dimensional ultrasonography of 88.9% and 56.0%, respectively.22

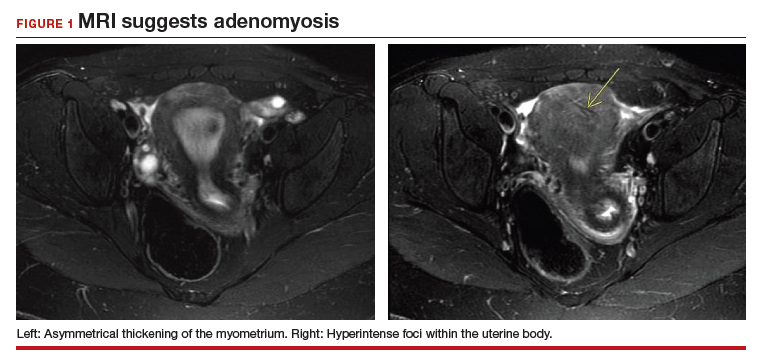

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used in the evaluation of adenomyosis. Although MRI is considered a more accurate diagnostic modality because it is not operator dependent, expense often prohibits its use in the work-up of abnormal uterine bleeding and chronic pelvic pain.2,23

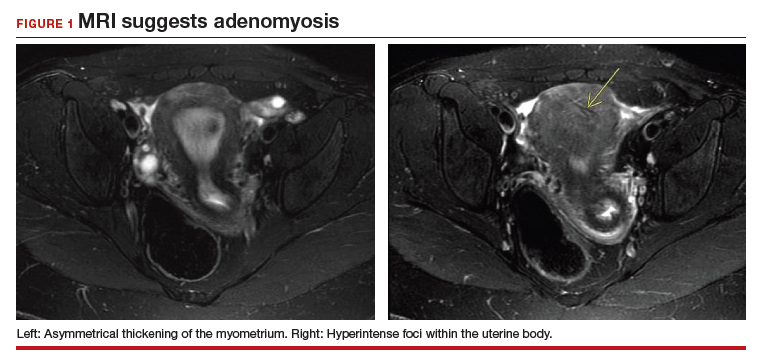

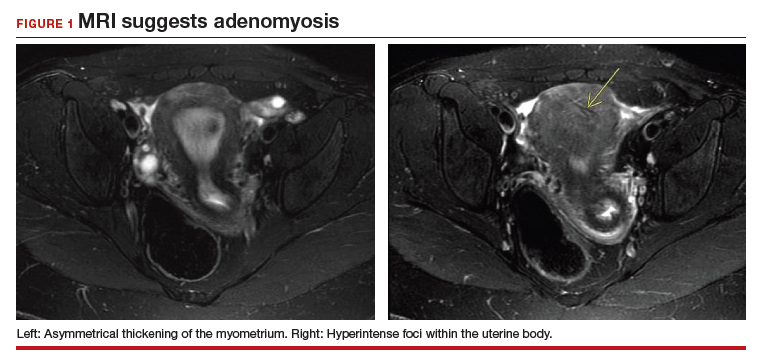

The most commonly reported MRI findings in adenomyosis include a globular or asymmetric uterus, heterogeneity of myometrial signal intensity, and thickening of the junctional zone24 (FIGURE 1). In a systematic review, researchers reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 89%, respectively, for the diagnosis of adenomyosis using MRI.25

Approaches to treatment

Medical management

No medical therapies or guidelines specific to the treatment of adenomyosis exist.9 Often, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are employed to combat cramping and pain associated with increased prostaglandin levels.26 A systematic review found that NSAIDs are significantly better at treating dysmenorrhea than placebo alone.26

Moreover, adenomyosis is an estrogen-dependent disease; consequently, many medical treatments are targeted at suppressing the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly used (off-label) for this effect include combined or progestin-only oral contraceptive pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors.

Use of a GnRH agonist, such as leuprolide, is limited to a short course (<6 months) because menopausal-like symptoms, such as hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and loss of bone-mineral density, can develop.16 Symptoms of adenomyosis often return upon cessation of hormonal treatment.1

Novel therapies are under investigation, including GnRH antagonists, selective progesterone-receptor modulators, and antiplatelet therapy.27

Although there are few data showing the effectiveness of medical therapy on adenomyosis-specific outcomes, medications are particularly useful in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who may prefer not to undergo surgery. Furthermore, medical therapy has considerable use in conjunction with surgical intervention; a prospective observational study showed that women who underwent GnRH agonist treatment following surgery had significantly greater improvement of their dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia, compared with those who underwent surgery only.28 In addition, preoperative administration of a GnRH agonist or danazol several months prior to surgery has been shown to reduce uterine vascularity and, thus, blood loss at surgery.29,30

- Adenomyosis is common and benign, but remains underdiagnosed because of a nonspecific clinical presentation and lack of standardized diagnostic criteria.

- Adenomyosis can cause significant associated morbidity: dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.

- High clinical suspicion warrants evaluation by imaging.

- Medical management is largely aimed at ameliorating symptoms.

- A patient who does not respond to medical treatment or does not desire pregnancy has a variety of surgical options; the extent of disease and the patient’s wish for uterine preservation guide the selection of surgical technique.

- Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment but, in patients who want to avoid radical resection, techniques developed for laparotomy are available, to allow conservative resection using laparoscopy.

- Ideally, surgery is performed using a combined laparoscopy and minilaparotomy approach, after appropriate imaging.

Continue to: Surgery

Surgery

The objective of surgical management is to ameliorate symptoms in a conservative manner, by excision or cytoreduction of adenomyotic lesions, while preserving, even improving, fertility.3,11,31 The choice of procedure depends, ultimately, on the location and extent of disease, the patient’s desire for uterine preservation and fertility, and surgical skill.3

Historically, hysterectomy was used to treat adenomyosis; for patients declining fertility preservation, hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment. Since the early 1950s, several techniques for laparotomic reduction have been developed. Surgeries that achieve partial reduction include:

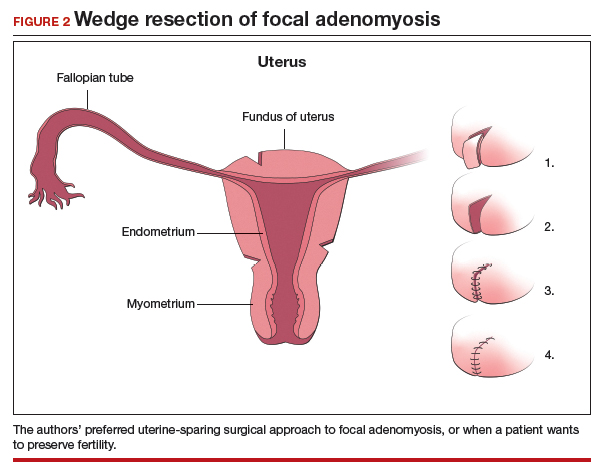

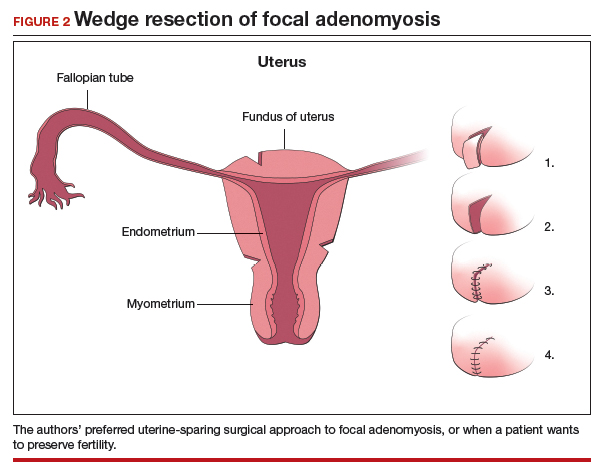

Wedge resection of the uterine wall entails removal of the seromuscular layer at the identified location of adenomyotic tissue, with subsequent repair of the remaining muscular and serosal layers surrounding the wound.3,32 Because adenomyotic tissue can remain on either side of the incision in wedge resection, clinical improvement in symptoms of dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia are modest, and recurrence is possible.7

Modified reduction surgery. Modifications of reduction surgery include slicing adenomyotic tissue using microsurgery and partial excision.33

Transverse-H incision of the uterine wall involves a transverse incision on the uterine fundus, separating serosa and myometrium, followed by removal of diseased tissue using an electrosurgical scalpel or scissors. Tensionless suturing is used to close the myometrial layers in 1 or 2 layers to establish hemostasis and close the defect; serosal flaps are closed with subserosal interrupted sutures.34 Data show that, following surgery with this technique, 21.4% to 38.7% of patients who attempt conception achieve clinical pregnancy.7

Complete, conservative resection in cases of diffuse and focal adenomyosis is possible using the triple-flap method, in which total resection is achieved by removing diseased myometrium until healthy, soft tissue—with normal texture, color, and vascularity—is reached.2 Repair with this technique reduces the risk of uterine rupture by reconstructing the uterine wall using a muscle flap prepared by metroplasty.7 In a study of 64 women who underwent triple-flap resection, a clinical pregnancy rate of 74% and a live birth rate of 52% were reported.7

Minimally invasive approaches. Although several techniques have been developed for focal excision of adenomyosis by laparotomy,7 the trend has been toward minimally invasive surgery, which reduces estimated blood loss, decreases length of stay, and reduces adhesion formation—all without a statistically significant difference in long-term clinical outcomes, compared to other techniques.35-39 Furthermore, enhanced visualization of pelvic organs provided by laparoscopy is vital in the case of adenomyosis.3,31

How our group approaches surgical management. A challenge in laparoscopic surgery of adenomyosis is extraction of an extensive amount of diseased tissue. In 1994, our group described the use of simultaneous operative laparoscopy and minilaparotomy technique as an effective and safe alternative to laparotomy in the treatment of myomectomy6; the surgical principles of that approach are applied to adenomyomectomy. The technique involves treatment of pelvic pathology with laparoscopy, removal of tissue through the minilaparotomy incision, and repair of the uterine wall defect in layers.

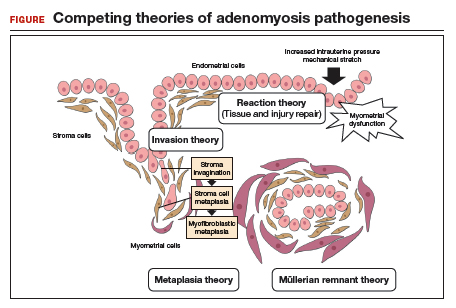

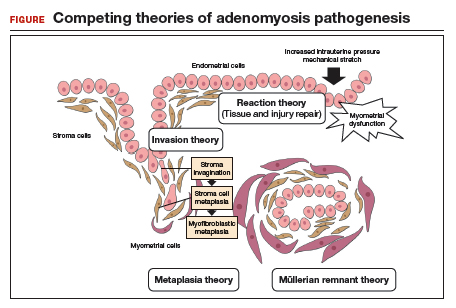

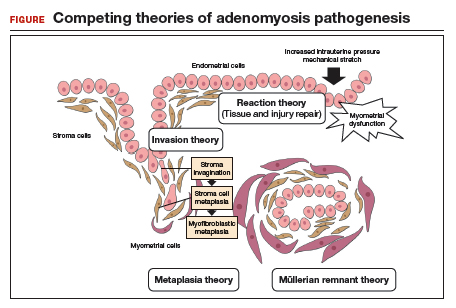

How adenomyosis originates is not fully understood. Several theories have been proposed, however (including, more prominently, the first 2 below):

Invasion theory. The endometrial basalis layer invaginates and invades the myometrium1,2 (FIGURE); the etiology of invagination remains unknown.

Reaction theory. Myometrial weakness or dysfunction, brought on by trauma from previous uterine surgery or pregnancy, could predispose uterine musculature to deep invasion.3

Metaplasia theory. Adenomyosis is a result of metaplasia of pluripotent Müllerian rests.

Müllerian remnant theory. Related to the Müllerian metaplasia theory, adenomyosis is formed de novo from 1) adult stem cells located in the endometrial basalis that is involved in the cyclic regeneration of the endometrium4-6 or 2) adult stem cells displaced from bone marrow.7,8

Once adenomyosis is established, it is thought to progress by epithelial–mesenchymal transition,2 a process by which epithelial cells become highly motile mesenchymal cells that are capable of migration and invasion, due to loss of cell–cell adhesion properties.9

References

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.2016; 23:164-185.

- García-Solares J, Donnez J, Donnez O, et al. Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: invagination or metaplasia? Fertil Steril.2018;109:371-379.

- Ferenczy A. Pathophysiology of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:312-322.

- Gargett CE. Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:87-101.

- Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1738-1750.

- Schwab KE, Chan RWS, Gargett CE. Putative stem cell activity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(Suppl 2):1124-1130.

- Sasson IE, Taylor HS. Stem cells and the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:106-115.

- Du H, Taylor HS. Stem cells and female reproduction. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:126-139.

- Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1438-1449.

Continue to: In 57 women who underwent…

In 57 women who underwent this procedure, the mean operative time was 127 minutes; average estimated blood loss was 267 mL.40 Overall, laparoscopy with minilaparotomy was found to be a less technically difficult technique for laparoscopic myomectomy; allowed better closure of the uterine defect; and might have required less time to perform.3

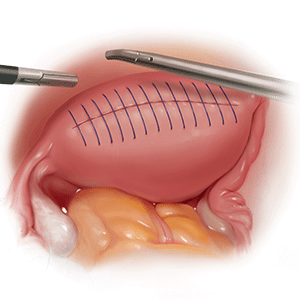

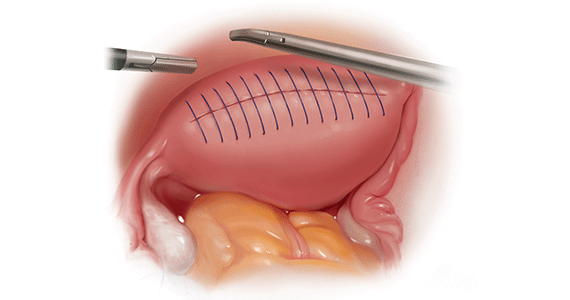

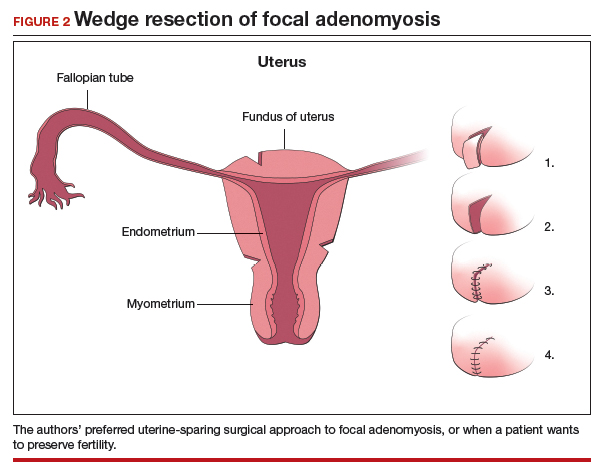

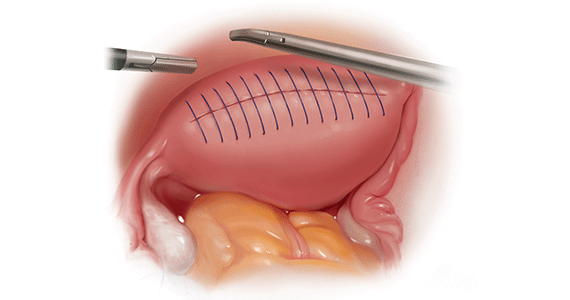

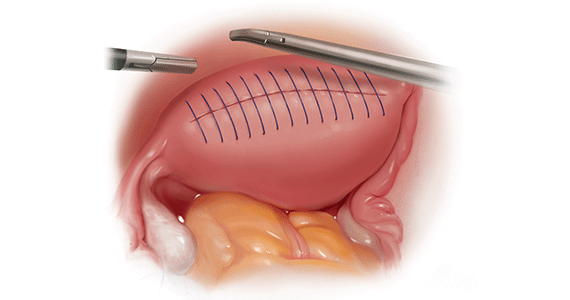

We therefore advocate video laparoscopic wedge resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when necessary for safe removal of larger adenomyomas, as the preferred uterine-sparing surgical approach for focal adenomyosis or when the patient wants to preserve fertility (FIGURE 2). We think that this technique allows focal adenomyosis to be treated by wedge resection of the diseased myometrium, with subsequent closure of the remaining myometrial defect using a barbed V-Loc (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) delayed absorbable suture in layers (FIGURE 3). Minilaparotomy can be utilized when indicated to aid removal of the resected myometrial specimen.

In our extensive experience, we have found that this technique provides significant relief of symptoms and improvements in fertility outcomes while minimizing surgical morbidity.

CASE Resolved

The patient underwent successful wedge resection of her adenomyosis by laparoscopy. She experienced nearly complete resolution of her symptoms of dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and pelvic pain. She retained good uterine integrity. Three years later, she and her husband became parents when she delivered their first child by cesarean delivery at full term. After she completed childbearing, she ultimately opted for minimally invasive hysterectomy.

The authors would like to acknowledge Mailinh Vu, MD, Fellow at Camran Nezhat Institute, for reviewing and editing this article.

- Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:428-437.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Azziz R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

- Rokitansky C. Ueber Uterusdrsen-Neubildung in Uterus- und Ovarial-Sarcomen. Gesellschaft der Ärzte in Wien. 1860;16:1-4.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Van Praagh I. Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis uteri in young women: local excision and metroplasty. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;93:1174-1175.

- Donnez J, Donnez O, Dolmans MM. Introduction: Uterine adenomyosis, another enigmatic disease of our time. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:369-370.

- Nishida M, Takano K, Arai Y, et al. Conservative surgical management for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:715-719.

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-A)--Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:68-81.

- Matalliotakis IM, Katsikis IK, Panidis DK. Adenomyosis: what is the impact on fertility? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:261-264.

- Devlieger R, D'Hooghe T, Timmerman D. Uterine adenomyosis in the infertility clinic. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:139-147.

- Levgur M, Abadi MA, Tucker A. Adenomyosis: symptoms, histology, and pregnancy terminations. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:688-691.

- Weiss G, Maseelall P, Schott LL, et al. Adenomyosis a variant, not a disease? Evidence from hysterectomized menopausal women in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Fertil Steril. 2009;91:201-206.

- Huang F, Kung FT, Chang SY, et al. Effects of short-course buserelin therapy on adenomyosis. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:741-744.

- Benson RC, Sneeden VD. Adenomyosis: a reappraisal of symptomatology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;76:1044-1061.

- Shrestha A, Sedai LB. Understanding clinical features of adenomyosis: a case control study. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14:176-179.

- Fernández C, Ricci P, Fernández E. Adenomyosis visualized during hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:555-556.

- Brosens JJ, Barker FG. The role of myometrial needle biopsies in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1347-1349.

- Van den Bosch T, Van Schoubroeck D. Ultrasound diagnosis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:16-24.

- Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Ribeiro J, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:257-264.

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433.

- Bragheto AM, Caserta N, Bahamondes L, et al. Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis diagnosed and monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. Contraception. 2007;76:195-199.

- Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89:1374-1384.

- Marjoribanks J, Proctor M, Farquhar C, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001751.

- Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, et al. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:398-405.

- Wang PH, Liu WM, Fuh JL, et al. Comparison of surgery alone and combined surgical-medical treatment in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:876-885.

- Wood C, Maher P, Woods R. Laparoscopic surgical techniques for endometriosis and adenomyosis. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2000;6:153-168.

- Wang CJ, Yuen LT, Chang SD, et al. Use of laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery to treat infertile women with localized adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:462.e5-e8.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Sun A, Luo M, Wang W, et al. Characteristics and efficacy of modified adenomyomectomy in the treatment of uterine adenomyoma. Chin Med J. 2011;124:1322-1326.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanotti F, et al. Surgery: Fertility after conservative surgery for adenomyomas. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1708-1710.

- Fujishita A, Masuzaki H, Khan KN, et al. Modified reduction surgery for adenomyosis. A preliminary report of the transverse H incision technique. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;57:132-138.

- Operative Laparoscopy Study Group. Postoperative adhesion development after operative laparoscopy: evaluation at early second-look procedures. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:700-704.

- Luciano AA, Maier DB, Koch EI, et al. A comparative study of postoperative adhesions following laser surgery by laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the rabbit model. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:220-224.

- Lundorff P, Hahlin M, Källfelt B, et al. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in tubal pregnancy: a randomized trial versus laparotomy. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:911-915.

- Kwack JY, Kwon YS. Laparoscopic surgery for focal adenomyosis. JSLS. 2017;21. pii:e2017.00014.

- Podratz K. Degrees of Freedom: Advances in Gynecological and Obstetrical Surgery. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years 1913-2012. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O, et al. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1994;39:39-44.

CASE

A 28-year-old patient presents for evaluation and management of her chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia. She previously tried ibuprofen with no pain relief. She also tried oral and long-acting reversible contraceptives but continued to be symptomatic. She underwent pelvic sonography, which demonstrated a large globular uterus with myometrial thickening and myometrial cysts with increased hypervascularity. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging indicated a thickened junctional zone. Feeling she had exhausted medical manegement options with no significant improvement, she desired surgical treatment, but wanted to retain her future fertility. As a newlywed, she and her husband were planning on building a family so she desired to retain her uterus for potential future pregnancy.

How would you address this patient’s disruptive symptoms, while affirming her long-term plans by choosing the proper intervention?

Adenomyosis is characterized by endometrial-like glands and stroma deep within the myometrium of the uterus and generally is classified as diffuse or focal. This common, benign gynecologic condition is known to cause enlargement of the uterus secondary to stimulation of ectopic endometrial-like cells.1-3 Although the true incidence of adenomyosis is unknown because of the difficulty of making the diagnosis, prevalence has been variously reported at 6% to 70% among reproductive-aged women.4,5

In this review, we first examine the clinical presentation and diagnosis of adenomyosis. We then discuss clinical indications for, and surgical techniques of, adenomyomectomy, including our preferred uterine-sparing approach for focal disease or when the patient wants to preserve fertility: video laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when indicated.

Treatment evolved in a century and a half

Adenomyosis was first described more than 150 years ago; historically, hysterectomy was the mainstay of treatment.2,6 Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis has been reported since the early 1950s.6-8 Surgical treatment initially became more widespread following the introduction of wedge resection, which allowed for partial excision of adenomyotic nodules.9

More recent developments in diagnostic technologies and capabilities have allowed for the emergence of additional uterine-sparing and minimally invasive surgical treatment options for adenomyosis.3,10 Although the use of laparoscopic approaches is limited because a high level of technical skill is required to undertake these procedures, such approaches are becoming increasingly important as more and more patients seek fertility conservation.11-13

How does adenomyosis present?

Adenomyosis symptoms commonly consist of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea, affecting approximately 40% to 60% and 15% to 30% of patients with the condition, respectively.14 These symptoms are considered nonspecific because they are also associated with other uterine abnormalities.15 Although menorrhagia is not associated with extent of disease, dysmenorrhea is associated with both the number and depth of adenomyotic foci.14

Other symptoms reported with adenomyosis include chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, as well as infertility. Note, however, that a large percentage of patients are asymptomatic.16,17

On physical examination, patients commonly exhibit a diffusely enlarged, globular uterus. This finding is secondary to uniform hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the myometrium, caused by stimulation of ectopic endometrial cells.2 A subset of patients experience significant uterine tenderness.18 Other common findings associated with adenomyosis include uterine abnormalities, such as leiomyomata, endometriosis, and endometrial polyps.

Continue to: Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential...

Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential

Histology

Adenomyosis is definitively diagnosed based on histologic findings of endometrial-like tissue within the myometrium. Historically, histologic analysis was performed on specimens following hysterectomy but, more recently, has utilized specimens obtained from hysteroscopic and laparoscopic myometrial biopsies.19 Importantly, although hysteroscopic and laparoscopic biopsies are taken under direct visualization, there are no pathognomonic signs for adenomyosis; a diagnosis can therefore be missed if adenomyosis is not present at biopsied sites.1 The sensitivity of random biopsy at laparoscopy has been found to be as low as 2% to as high as 56%.20

Imaging

Imaging can be helpful in clinical decision making and to guide the differential diagnosis. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is often the first mode of imaging used for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding or pelvic pain. Diagnosis by TVUS is difficult because the modality is operator dependent and standard diagnostic criteria are lacking.5

The most commonly reported ultrasonographic features of adenomyosis are21,22:

- a globally enlarged uterus

- asymmetry

- myometrial thickening with heterogeneity

- poorly defined foci of hyperechoic regions, surrounded by hypoechoic areas that correspond to smooth-muscle hyperplasia

- myometrial cysts.

Doppler ultrasound examination in patients with adenomyosis reveals increased flow to the myometrium without evidence of large blood vessels.

3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasonography. Integration of 3-D ultrasonography has allowed for identification of the thicker junctional zone that suggests adenomyosis. In a systematic review of the accuracy of TVUS, investigators reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 2-dimensional ultrasonography of 83.8% and 63.9%, respectively, and a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 3-dimensional ultrasonography of 88.9% and 56.0%, respectively.22

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used in the evaluation of adenomyosis. Although MRI is considered a more accurate diagnostic modality because it is not operator dependent, expense often prohibits its use in the work-up of abnormal uterine bleeding and chronic pelvic pain.2,23

The most commonly reported MRI findings in adenomyosis include a globular or asymmetric uterus, heterogeneity of myometrial signal intensity, and thickening of the junctional zone24 (FIGURE 1). In a systematic review, researchers reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 89%, respectively, for the diagnosis of adenomyosis using MRI.25

Approaches to treatment

Medical management

No medical therapies or guidelines specific to the treatment of adenomyosis exist.9 Often, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are employed to combat cramping and pain associated with increased prostaglandin levels.26 A systematic review found that NSAIDs are significantly better at treating dysmenorrhea than placebo alone.26

Moreover, adenomyosis is an estrogen-dependent disease; consequently, many medical treatments are targeted at suppressing the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly used (off-label) for this effect include combined or progestin-only oral contraceptive pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors.

Use of a GnRH agonist, such as leuprolide, is limited to a short course (<6 months) because menopausal-like symptoms, such as hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and loss of bone-mineral density, can develop.16 Symptoms of adenomyosis often return upon cessation of hormonal treatment.1

Novel therapies are under investigation, including GnRH antagonists, selective progesterone-receptor modulators, and antiplatelet therapy.27

Although there are few data showing the effectiveness of medical therapy on adenomyosis-specific outcomes, medications are particularly useful in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who may prefer not to undergo surgery. Furthermore, medical therapy has considerable use in conjunction with surgical intervention; a prospective observational study showed that women who underwent GnRH agonist treatment following surgery had significantly greater improvement of their dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia, compared with those who underwent surgery only.28 In addition, preoperative administration of a GnRH agonist or danazol several months prior to surgery has been shown to reduce uterine vascularity and, thus, blood loss at surgery.29,30

- Adenomyosis is common and benign, but remains underdiagnosed because of a nonspecific clinical presentation and lack of standardized diagnostic criteria.

- Adenomyosis can cause significant associated morbidity: dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.

- High clinical suspicion warrants evaluation by imaging.

- Medical management is largely aimed at ameliorating symptoms.

- A patient who does not respond to medical treatment or does not desire pregnancy has a variety of surgical options; the extent of disease and the patient’s wish for uterine preservation guide the selection of surgical technique.

- Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment but, in patients who want to avoid radical resection, techniques developed for laparotomy are available, to allow conservative resection using laparoscopy.

- Ideally, surgery is performed using a combined laparoscopy and minilaparotomy approach, after appropriate imaging.

Continue to: Surgery

Surgery

The objective of surgical management is to ameliorate symptoms in a conservative manner, by excision or cytoreduction of adenomyotic lesions, while preserving, even improving, fertility.3,11,31 The choice of procedure depends, ultimately, on the location and extent of disease, the patient’s desire for uterine preservation and fertility, and surgical skill.3

Historically, hysterectomy was used to treat adenomyosis; for patients declining fertility preservation, hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment. Since the early 1950s, several techniques for laparotomic reduction have been developed. Surgeries that achieve partial reduction include:

Wedge resection of the uterine wall entails removal of the seromuscular layer at the identified location of adenomyotic tissue, with subsequent repair of the remaining muscular and serosal layers surrounding the wound.3,32 Because adenomyotic tissue can remain on either side of the incision in wedge resection, clinical improvement in symptoms of dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia are modest, and recurrence is possible.7

Modified reduction surgery. Modifications of reduction surgery include slicing adenomyotic tissue using microsurgery and partial excision.33

Transverse-H incision of the uterine wall involves a transverse incision on the uterine fundus, separating serosa and myometrium, followed by removal of diseased tissue using an electrosurgical scalpel or scissors. Tensionless suturing is used to close the myometrial layers in 1 or 2 layers to establish hemostasis and close the defect; serosal flaps are closed with subserosal interrupted sutures.34 Data show that, following surgery with this technique, 21.4% to 38.7% of patients who attempt conception achieve clinical pregnancy.7

Complete, conservative resection in cases of diffuse and focal adenomyosis is possible using the triple-flap method, in which total resection is achieved by removing diseased myometrium until healthy, soft tissue—with normal texture, color, and vascularity—is reached.2 Repair with this technique reduces the risk of uterine rupture by reconstructing the uterine wall using a muscle flap prepared by metroplasty.7 In a study of 64 women who underwent triple-flap resection, a clinical pregnancy rate of 74% and a live birth rate of 52% were reported.7

Minimally invasive approaches. Although several techniques have been developed for focal excision of adenomyosis by laparotomy,7 the trend has been toward minimally invasive surgery, which reduces estimated blood loss, decreases length of stay, and reduces adhesion formation—all without a statistically significant difference in long-term clinical outcomes, compared to other techniques.35-39 Furthermore, enhanced visualization of pelvic organs provided by laparoscopy is vital in the case of adenomyosis.3,31

How our group approaches surgical management. A challenge in laparoscopic surgery of adenomyosis is extraction of an extensive amount of diseased tissue. In 1994, our group described the use of simultaneous operative laparoscopy and minilaparotomy technique as an effective and safe alternative to laparotomy in the treatment of myomectomy6; the surgical principles of that approach are applied to adenomyomectomy. The technique involves treatment of pelvic pathology with laparoscopy, removal of tissue through the minilaparotomy incision, and repair of the uterine wall defect in layers.

How adenomyosis originates is not fully understood. Several theories have been proposed, however (including, more prominently, the first 2 below):

Invasion theory. The endometrial basalis layer invaginates and invades the myometrium1,2 (FIGURE); the etiology of invagination remains unknown.

Reaction theory. Myometrial weakness or dysfunction, brought on by trauma from previous uterine surgery or pregnancy, could predispose uterine musculature to deep invasion.3

Metaplasia theory. Adenomyosis is a result of metaplasia of pluripotent Müllerian rests.

Müllerian remnant theory. Related to the Müllerian metaplasia theory, adenomyosis is formed de novo from 1) adult stem cells located in the endometrial basalis that is involved in the cyclic regeneration of the endometrium4-6 or 2) adult stem cells displaced from bone marrow.7,8

Once adenomyosis is established, it is thought to progress by epithelial–mesenchymal transition,2 a process by which epithelial cells become highly motile mesenchymal cells that are capable of migration and invasion, due to loss of cell–cell adhesion properties.9

References

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.2016; 23:164-185.

- García-Solares J, Donnez J, Donnez O, et al. Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: invagination or metaplasia? Fertil Steril.2018;109:371-379.

- Ferenczy A. Pathophysiology of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:312-322.

- Gargett CE. Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:87-101.

- Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1738-1750.

- Schwab KE, Chan RWS, Gargett CE. Putative stem cell activity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(Suppl 2):1124-1130.

- Sasson IE, Taylor HS. Stem cells and the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:106-115.

- Du H, Taylor HS. Stem cells and female reproduction. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:126-139.

- Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1438-1449.

Continue to: In 57 women who underwent…

In 57 women who underwent this procedure, the mean operative time was 127 minutes; average estimated blood loss was 267 mL.40 Overall, laparoscopy with minilaparotomy was found to be a less technically difficult technique for laparoscopic myomectomy; allowed better closure of the uterine defect; and might have required less time to perform.3

We therefore advocate video laparoscopic wedge resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when necessary for safe removal of larger adenomyomas, as the preferred uterine-sparing surgical approach for focal adenomyosis or when the patient wants to preserve fertility (FIGURE 2). We think that this technique allows focal adenomyosis to be treated by wedge resection of the diseased myometrium, with subsequent closure of the remaining myometrial defect using a barbed V-Loc (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) delayed absorbable suture in layers (FIGURE 3). Minilaparotomy can be utilized when indicated to aid removal of the resected myometrial specimen.

In our extensive experience, we have found that this technique provides significant relief of symptoms and improvements in fertility outcomes while minimizing surgical morbidity.

CASE Resolved

The patient underwent successful wedge resection of her adenomyosis by laparoscopy. She experienced nearly complete resolution of her symptoms of dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and pelvic pain. She retained good uterine integrity. Three years later, she and her husband became parents when she delivered their first child by cesarean delivery at full term. After she completed childbearing, she ultimately opted for minimally invasive hysterectomy.

The authors would like to acknowledge Mailinh Vu, MD, Fellow at Camran Nezhat Institute, for reviewing and editing this article.

CASE

A 28-year-old patient presents for evaluation and management of her chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia. She previously tried ibuprofen with no pain relief. She also tried oral and long-acting reversible contraceptives but continued to be symptomatic. She underwent pelvic sonography, which demonstrated a large globular uterus with myometrial thickening and myometrial cysts with increased hypervascularity. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging indicated a thickened junctional zone. Feeling she had exhausted medical manegement options with no significant improvement, she desired surgical treatment, but wanted to retain her future fertility. As a newlywed, she and her husband were planning on building a family so she desired to retain her uterus for potential future pregnancy.

How would you address this patient’s disruptive symptoms, while affirming her long-term plans by choosing the proper intervention?

Adenomyosis is characterized by endometrial-like glands and stroma deep within the myometrium of the uterus and generally is classified as diffuse or focal. This common, benign gynecologic condition is known to cause enlargement of the uterus secondary to stimulation of ectopic endometrial-like cells.1-3 Although the true incidence of adenomyosis is unknown because of the difficulty of making the diagnosis, prevalence has been variously reported at 6% to 70% among reproductive-aged women.4,5

In this review, we first examine the clinical presentation and diagnosis of adenomyosis. We then discuss clinical indications for, and surgical techniques of, adenomyomectomy, including our preferred uterine-sparing approach for focal disease or when the patient wants to preserve fertility: video laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when indicated.

Treatment evolved in a century and a half

Adenomyosis was first described more than 150 years ago; historically, hysterectomy was the mainstay of treatment.2,6 Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis has been reported since the early 1950s.6-8 Surgical treatment initially became more widespread following the introduction of wedge resection, which allowed for partial excision of adenomyotic nodules.9

More recent developments in diagnostic technologies and capabilities have allowed for the emergence of additional uterine-sparing and minimally invasive surgical treatment options for adenomyosis.3,10 Although the use of laparoscopic approaches is limited because a high level of technical skill is required to undertake these procedures, such approaches are becoming increasingly important as more and more patients seek fertility conservation.11-13

How does adenomyosis present?

Adenomyosis symptoms commonly consist of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea, affecting approximately 40% to 60% and 15% to 30% of patients with the condition, respectively.14 These symptoms are considered nonspecific because they are also associated with other uterine abnormalities.15 Although menorrhagia is not associated with extent of disease, dysmenorrhea is associated with both the number and depth of adenomyotic foci.14

Other symptoms reported with adenomyosis include chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, as well as infertility. Note, however, that a large percentage of patients are asymptomatic.16,17

On physical examination, patients commonly exhibit a diffusely enlarged, globular uterus. This finding is secondary to uniform hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the myometrium, caused by stimulation of ectopic endometrial cells.2 A subset of patients experience significant uterine tenderness.18 Other common findings associated with adenomyosis include uterine abnormalities, such as leiomyomata, endometriosis, and endometrial polyps.

Continue to: Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential...

Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential

Histology

Adenomyosis is definitively diagnosed based on histologic findings of endometrial-like tissue within the myometrium. Historically, histologic analysis was performed on specimens following hysterectomy but, more recently, has utilized specimens obtained from hysteroscopic and laparoscopic myometrial biopsies.19 Importantly, although hysteroscopic and laparoscopic biopsies are taken under direct visualization, there are no pathognomonic signs for adenomyosis; a diagnosis can therefore be missed if adenomyosis is not present at biopsied sites.1 The sensitivity of random biopsy at laparoscopy has been found to be as low as 2% to as high as 56%.20

Imaging

Imaging can be helpful in clinical decision making and to guide the differential diagnosis. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is often the first mode of imaging used for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding or pelvic pain. Diagnosis by TVUS is difficult because the modality is operator dependent and standard diagnostic criteria are lacking.5

The most commonly reported ultrasonographic features of adenomyosis are21,22:

- a globally enlarged uterus

- asymmetry

- myometrial thickening with heterogeneity

- poorly defined foci of hyperechoic regions, surrounded by hypoechoic areas that correspond to smooth-muscle hyperplasia

- myometrial cysts.

Doppler ultrasound examination in patients with adenomyosis reveals increased flow to the myometrium without evidence of large blood vessels.

3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasonography. Integration of 3-D ultrasonography has allowed for identification of the thicker junctional zone that suggests adenomyosis. In a systematic review of the accuracy of TVUS, investigators reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 2-dimensional ultrasonography of 83.8% and 63.9%, respectively, and a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 3-dimensional ultrasonography of 88.9% and 56.0%, respectively.22

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used in the evaluation of adenomyosis. Although MRI is considered a more accurate diagnostic modality because it is not operator dependent, expense often prohibits its use in the work-up of abnormal uterine bleeding and chronic pelvic pain.2,23

The most commonly reported MRI findings in adenomyosis include a globular or asymmetric uterus, heterogeneity of myometrial signal intensity, and thickening of the junctional zone24 (FIGURE 1). In a systematic review, researchers reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 89%, respectively, for the diagnosis of adenomyosis using MRI.25

Approaches to treatment

Medical management

No medical therapies or guidelines specific to the treatment of adenomyosis exist.9 Often, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are employed to combat cramping and pain associated with increased prostaglandin levels.26 A systematic review found that NSAIDs are significantly better at treating dysmenorrhea than placebo alone.26

Moreover, adenomyosis is an estrogen-dependent disease; consequently, many medical treatments are targeted at suppressing the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly used (off-label) for this effect include combined or progestin-only oral contraceptive pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors.

Use of a GnRH agonist, such as leuprolide, is limited to a short course (<6 months) because menopausal-like symptoms, such as hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and loss of bone-mineral density, can develop.16 Symptoms of adenomyosis often return upon cessation of hormonal treatment.1

Novel therapies are under investigation, including GnRH antagonists, selective progesterone-receptor modulators, and antiplatelet therapy.27

Although there are few data showing the effectiveness of medical therapy on adenomyosis-specific outcomes, medications are particularly useful in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who may prefer not to undergo surgery. Furthermore, medical therapy has considerable use in conjunction with surgical intervention; a prospective observational study showed that women who underwent GnRH agonist treatment following surgery had significantly greater improvement of their dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia, compared with those who underwent surgery only.28 In addition, preoperative administration of a GnRH agonist or danazol several months prior to surgery has been shown to reduce uterine vascularity and, thus, blood loss at surgery.29,30

- Adenomyosis is common and benign, but remains underdiagnosed because of a nonspecific clinical presentation and lack of standardized diagnostic criteria.

- Adenomyosis can cause significant associated morbidity: dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.

- High clinical suspicion warrants evaluation by imaging.

- Medical management is largely aimed at ameliorating symptoms.

- A patient who does not respond to medical treatment or does not desire pregnancy has a variety of surgical options; the extent of disease and the patient’s wish for uterine preservation guide the selection of surgical technique.

- Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment but, in patients who want to avoid radical resection, techniques developed for laparotomy are available, to allow conservative resection using laparoscopy.

- Ideally, surgery is performed using a combined laparoscopy and minilaparotomy approach, after appropriate imaging.

Continue to: Surgery

Surgery

The objective of surgical management is to ameliorate symptoms in a conservative manner, by excision or cytoreduction of adenomyotic lesions, while preserving, even improving, fertility.3,11,31 The choice of procedure depends, ultimately, on the location and extent of disease, the patient’s desire for uterine preservation and fertility, and surgical skill.3

Historically, hysterectomy was used to treat adenomyosis; for patients declining fertility preservation, hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment. Since the early 1950s, several techniques for laparotomic reduction have been developed. Surgeries that achieve partial reduction include:

Wedge resection of the uterine wall entails removal of the seromuscular layer at the identified location of adenomyotic tissue, with subsequent repair of the remaining muscular and serosal layers surrounding the wound.3,32 Because adenomyotic tissue can remain on either side of the incision in wedge resection, clinical improvement in symptoms of dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia are modest, and recurrence is possible.7

Modified reduction surgery. Modifications of reduction surgery include slicing adenomyotic tissue using microsurgery and partial excision.33

Transverse-H incision of the uterine wall involves a transverse incision on the uterine fundus, separating serosa and myometrium, followed by removal of diseased tissue using an electrosurgical scalpel or scissors. Tensionless suturing is used to close the myometrial layers in 1 or 2 layers to establish hemostasis and close the defect; serosal flaps are closed with subserosal interrupted sutures.34 Data show that, following surgery with this technique, 21.4% to 38.7% of patients who attempt conception achieve clinical pregnancy.7

Complete, conservative resection in cases of diffuse and focal adenomyosis is possible using the triple-flap method, in which total resection is achieved by removing diseased myometrium until healthy, soft tissue—with normal texture, color, and vascularity—is reached.2 Repair with this technique reduces the risk of uterine rupture by reconstructing the uterine wall using a muscle flap prepared by metroplasty.7 In a study of 64 women who underwent triple-flap resection, a clinical pregnancy rate of 74% and a live birth rate of 52% were reported.7

Minimally invasive approaches. Although several techniques have been developed for focal excision of adenomyosis by laparotomy,7 the trend has been toward minimally invasive surgery, which reduces estimated blood loss, decreases length of stay, and reduces adhesion formation—all without a statistically significant difference in long-term clinical outcomes, compared to other techniques.35-39 Furthermore, enhanced visualization of pelvic organs provided by laparoscopy is vital in the case of adenomyosis.3,31

How our group approaches surgical management. A challenge in laparoscopic surgery of adenomyosis is extraction of an extensive amount of diseased tissue. In 1994, our group described the use of simultaneous operative laparoscopy and minilaparotomy technique as an effective and safe alternative to laparotomy in the treatment of myomectomy6; the surgical principles of that approach are applied to adenomyomectomy. The technique involves treatment of pelvic pathology with laparoscopy, removal of tissue through the minilaparotomy incision, and repair of the uterine wall defect in layers.

How adenomyosis originates is not fully understood. Several theories have been proposed, however (including, more prominently, the first 2 below):

Invasion theory. The endometrial basalis layer invaginates and invades the myometrium1,2 (FIGURE); the etiology of invagination remains unknown.

Reaction theory. Myometrial weakness or dysfunction, brought on by trauma from previous uterine surgery or pregnancy, could predispose uterine musculature to deep invasion.3

Metaplasia theory. Adenomyosis is a result of metaplasia of pluripotent Müllerian rests.

Müllerian remnant theory. Related to the Müllerian metaplasia theory, adenomyosis is formed de novo from 1) adult stem cells located in the endometrial basalis that is involved in the cyclic regeneration of the endometrium4-6 or 2) adult stem cells displaced from bone marrow.7,8

Once adenomyosis is established, it is thought to progress by epithelial–mesenchymal transition,2 a process by which epithelial cells become highly motile mesenchymal cells that are capable of migration and invasion, due to loss of cell–cell adhesion properties.9

References

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.2016; 23:164-185.

- García-Solares J, Donnez J, Donnez O, et al. Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: invagination or metaplasia? Fertil Steril.2018;109:371-379.

- Ferenczy A. Pathophysiology of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:312-322.

- Gargett CE. Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:87-101.

- Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1738-1750.

- Schwab KE, Chan RWS, Gargett CE. Putative stem cell activity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(Suppl 2):1124-1130.

- Sasson IE, Taylor HS. Stem cells and the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:106-115.

- Du H, Taylor HS. Stem cells and female reproduction. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:126-139.

- Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1438-1449.

Continue to: In 57 women who underwent…

In 57 women who underwent this procedure, the mean operative time was 127 minutes; average estimated blood loss was 267 mL.40 Overall, laparoscopy with minilaparotomy was found to be a less technically difficult technique for laparoscopic myomectomy; allowed better closure of the uterine defect; and might have required less time to perform.3

We therefore advocate video laparoscopic wedge resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when necessary for safe removal of larger adenomyomas, as the preferred uterine-sparing surgical approach for focal adenomyosis or when the patient wants to preserve fertility (FIGURE 2). We think that this technique allows focal adenomyosis to be treated by wedge resection of the diseased myometrium, with subsequent closure of the remaining myometrial defect using a barbed V-Loc (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) delayed absorbable suture in layers (FIGURE 3). Minilaparotomy can be utilized when indicated to aid removal of the resected myometrial specimen.

In our extensive experience, we have found that this technique provides significant relief of symptoms and improvements in fertility outcomes while minimizing surgical morbidity.

CASE Resolved

The patient underwent successful wedge resection of her adenomyosis by laparoscopy. She experienced nearly complete resolution of her symptoms of dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and pelvic pain. She retained good uterine integrity. Three years later, she and her husband became parents when she delivered their first child by cesarean delivery at full term. After she completed childbearing, she ultimately opted for minimally invasive hysterectomy.

The authors would like to acknowledge Mailinh Vu, MD, Fellow at Camran Nezhat Institute, for reviewing and editing this article.

- Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:428-437.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Azziz R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

- Rokitansky C. Ueber Uterusdrsen-Neubildung in Uterus- und Ovarial-Sarcomen. Gesellschaft der Ärzte in Wien. 1860;16:1-4.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Van Praagh I. Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis uteri in young women: local excision and metroplasty. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;93:1174-1175.

- Donnez J, Donnez O, Dolmans MM. Introduction: Uterine adenomyosis, another enigmatic disease of our time. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:369-370.

- Nishida M, Takano K, Arai Y, et al. Conservative surgical management for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:715-719.

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-A)--Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:68-81.

- Matalliotakis IM, Katsikis IK, Panidis DK. Adenomyosis: what is the impact on fertility? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:261-264.

- Devlieger R, D'Hooghe T, Timmerman D. Uterine adenomyosis in the infertility clinic. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:139-147.

- Levgur M, Abadi MA, Tucker A. Adenomyosis: symptoms, histology, and pregnancy terminations. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:688-691.

- Weiss G, Maseelall P, Schott LL, et al. Adenomyosis a variant, not a disease? Evidence from hysterectomized menopausal women in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Fertil Steril. 2009;91:201-206.

- Huang F, Kung FT, Chang SY, et al. Effects of short-course buserelin therapy on adenomyosis. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:741-744.

- Benson RC, Sneeden VD. Adenomyosis: a reappraisal of symptomatology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;76:1044-1061.

- Shrestha A, Sedai LB. Understanding clinical features of adenomyosis: a case control study. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14:176-179.

- Fernández C, Ricci P, Fernández E. Adenomyosis visualized during hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:555-556.

- Brosens JJ, Barker FG. The role of myometrial needle biopsies in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1347-1349.

- Van den Bosch T, Van Schoubroeck D. Ultrasound diagnosis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:16-24.

- Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Ribeiro J, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:257-264.

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433.

- Bragheto AM, Caserta N, Bahamondes L, et al. Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis diagnosed and monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. Contraception. 2007;76:195-199.

- Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89:1374-1384.

- Marjoribanks J, Proctor M, Farquhar C, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001751.

- Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, et al. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:398-405.

- Wang PH, Liu WM, Fuh JL, et al. Comparison of surgery alone and combined surgical-medical treatment in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:876-885.

- Wood C, Maher P, Woods R. Laparoscopic surgical techniques for endometriosis and adenomyosis. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2000;6:153-168.

- Wang CJ, Yuen LT, Chang SD, et al. Use of laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery to treat infertile women with localized adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:462.e5-e8.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Sun A, Luo M, Wang W, et al. Characteristics and efficacy of modified adenomyomectomy in the treatment of uterine adenomyoma. Chin Med J. 2011;124:1322-1326.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanotti F, et al. Surgery: Fertility after conservative surgery for adenomyomas. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1708-1710.

- Fujishita A, Masuzaki H, Khan KN, et al. Modified reduction surgery for adenomyosis. A preliminary report of the transverse H incision technique. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;57:132-138.

- Operative Laparoscopy Study Group. Postoperative adhesion development after operative laparoscopy: evaluation at early second-look procedures. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:700-704.

- Luciano AA, Maier DB, Koch EI, et al. A comparative study of postoperative adhesions following laser surgery by laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the rabbit model. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:220-224.

- Lundorff P, Hahlin M, Källfelt B, et al. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in tubal pregnancy: a randomized trial versus laparotomy. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:911-915.

- Kwack JY, Kwon YS. Laparoscopic surgery for focal adenomyosis. JSLS. 2017;21. pii:e2017.00014.

- Podratz K. Degrees of Freedom: Advances in Gynecological and Obstetrical Surgery. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years 1913-2012. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O, et al. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1994;39:39-44.

- Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:428-437.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Azziz R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

- Rokitansky C. Ueber Uterusdrsen-Neubildung in Uterus- und Ovarial-Sarcomen. Gesellschaft der Ärzte in Wien. 1860;16:1-4.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Van Praagh I. Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis uteri in young women: local excision and metroplasty. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;93:1174-1175.

- Donnez J, Donnez O, Dolmans MM. Introduction: Uterine adenomyosis, another enigmatic disease of our time. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:369-370.

- Nishida M, Takano K, Arai Y, et al. Conservative surgical management for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:715-719.

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-A)--Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:68-81.

- Matalliotakis IM, Katsikis IK, Panidis DK. Adenomyosis: what is the impact on fertility? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:261-264.

- Devlieger R, D'Hooghe T, Timmerman D. Uterine adenomyosis in the infertility clinic. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:139-147.

- Levgur M, Abadi MA, Tucker A. Adenomyosis: symptoms, histology, and pregnancy terminations. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:688-691.

- Weiss G, Maseelall P, Schott LL, et al. Adenomyosis a variant, not a disease? Evidence from hysterectomized menopausal women in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Fertil Steril. 2009;91:201-206.

- Huang F, Kung FT, Chang SY, et al. Effects of short-course buserelin therapy on adenomyosis. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:741-744.

- Benson RC, Sneeden VD. Adenomyosis: a reappraisal of symptomatology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;76:1044-1061.

- Shrestha A, Sedai LB. Understanding clinical features of adenomyosis: a case control study. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14:176-179.

- Fernández C, Ricci P, Fernández E. Adenomyosis visualized during hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:555-556.

- Brosens JJ, Barker FG. The role of myometrial needle biopsies in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1347-1349.

- Van den Bosch T, Van Schoubroeck D. Ultrasound diagnosis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:16-24.

- Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Ribeiro J, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:257-264.

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433.

- Bragheto AM, Caserta N, Bahamondes L, et al. Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis diagnosed and monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. Contraception. 2007;76:195-199.

- Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89:1374-1384.

- Marjoribanks J, Proctor M, Farquhar C, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001751.

- Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, et al. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:398-405.

- Wang PH, Liu WM, Fuh JL, et al. Comparison of surgery alone and combined surgical-medical treatment in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:876-885.

- Wood C, Maher P, Woods R. Laparoscopic surgical techniques for endometriosis and adenomyosis. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2000;6:153-168.

- Wang CJ, Yuen LT, Chang SD, et al. Use of laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery to treat infertile women with localized adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:462.e5-e8.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Sun A, Luo M, Wang W, et al. Characteristics and efficacy of modified adenomyomectomy in the treatment of uterine adenomyoma. Chin Med J. 2011;124:1322-1326.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanotti F, et al. Surgery: Fertility after conservative surgery for adenomyomas. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1708-1710.

- Fujishita A, Masuzaki H, Khan KN, et al. Modified reduction surgery for adenomyosis. A preliminary report of the transverse H incision technique. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;57:132-138.

- Operative Laparoscopy Study Group. Postoperative adhesion development after operative laparoscopy: evaluation at early second-look procedures. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:700-704.

- Luciano AA, Maier DB, Koch EI, et al. A comparative study of postoperative adhesions following laser surgery by laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the rabbit model. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:220-224.

- Lundorff P, Hahlin M, Källfelt B, et al. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in tubal pregnancy: a randomized trial versus laparotomy. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:911-915.

- Kwack JY, Kwon YS. Laparoscopic surgery for focal adenomyosis. JSLS. 2017;21. pii:e2017.00014.

- Podratz K. Degrees of Freedom: Advances in Gynecological and Obstetrical Surgery. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years 1913-2012. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O, et al. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1994;39:39-44.

Product Update: Bijuva; Liletta; Aegea Vapor System; Natural Cycles

TREATMENT FOR VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS

BIJUVA™ has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved as the first oral treatment for moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms due to menopause in women with a uterus. BIJUVA offers a combination of bioidentical estradiol to reduce moderate-to-severe hot flashes and bioidentical progesterone to reduce the risk for endometrial hyperplasia.

TherapeuticsMD says that BIJUVA will be available Spring 2019 and is a proven treatment option for women who are experiencing bothersome symptoms of menopause, with clinical trial data demonstrating a statistically significant reduction in both the frequency and severity of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. The manufacturer also says that BIJUVA is developed to be identical in molecular structure to the hormones already produced by the body and is designed to help women restore what is lost during menopause.

BIJUVA estradiol and progesterone combination (1 mg/100 mg) will be available in capsule form.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT:https://bijuva.com/discover/

LILETTA USE EXTENDED

The FDA has approved LILETTA® (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) 52 mg for 5-year use. This approval is based on efficacy and safety data from ACCESS IUS, the largest ongoing intrauterine device (IUD) Phase 3 clinical trial in the United States. Previously, LILETTA was indicated for use up to 4 years.

LILETTA continues to be greater than 99% effective in preventing pregnancy in a broad range of women, regardless of age, race, body mass index, or parity, according to Allergan and Medicines360. The extended duration and proven efficacy across a diverse population enables more women in the United States to obtain effective birth control, as the IUD is now available for a low cost at public health clinics.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.liletta.com

Continue to: ENDOMETRIAL ABLATION TECHNOLOGY

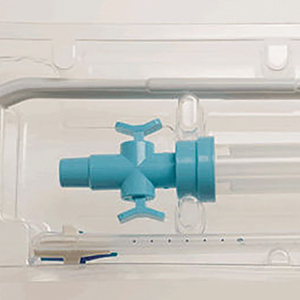

ENDOMETRIAL ABLATION TECHNOLOGY

AEGEA Medical introduces the AEGEA Vapor SystemTM, an innovative solution for endometrial ablation to treat menorrhagia.

The system uses Adaptive Vapor Ablation and is the first endometrial ablation system specifically designed for use in the doctor’s office, allowing minimal anesthesia/analgesia and rapid recovery, says AEGEA Medical.

AEGEA Medical describes the AEGEA Vapor System as a fully automated safety monitoring and vapor delivery system that uses a slender, flexible Vapor Probe with SmartSealTM technology and the Integrity ProTM safety feature, for an added level of confidence. The 4-minute procedure time includes 2 minutes of vapor treatment and can be performed in patients with a wider range of uterine anatomies than indicated for use with currently available treatments, says AEGEA Medical.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://aegeamedical.com/

NATURAL CYCLES

The FDA has cleared Natural Cycles as the first digital method of birth control in the United States. Delivered in the form of an app, Natural Cycles is a fertility awareness–based contraceptive that uses a sophisticated algorithm to accurately and conveniently determine a woman’s daily fertility based on basal body temperature.

That data builds into a personalized fertility indicator that informs her when she needs to use protection to minimize the chance of conception. The app also can be used to help plan a pregnancy when the time is right, according to Natural Cycles.

A clinical study showed that the efficacy of a contraceptive mobile application is higher than usually reported for traditional fertility awareness–based methods. The application may contribute to reducing the unmet need for contraception, says Natural Cycles.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.naturalcycles.com/en/hcp

TREATMENT FOR VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS

BIJUVA™ has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved as the first oral treatment for moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms due to menopause in women with a uterus. BIJUVA offers a combination of bioidentical estradiol to reduce moderate-to-severe hot flashes and bioidentical progesterone to reduce the risk for endometrial hyperplasia.

TherapeuticsMD says that BIJUVA will be available Spring 2019 and is a proven treatment option for women who are experiencing bothersome symptoms of menopause, with clinical trial data demonstrating a statistically significant reduction in both the frequency and severity of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. The manufacturer also says that BIJUVA is developed to be identical in molecular structure to the hormones already produced by the body and is designed to help women restore what is lost during menopause.

BIJUVA estradiol and progesterone combination (1 mg/100 mg) will be available in capsule form.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT:https://bijuva.com/discover/

LILETTA USE EXTENDED

The FDA has approved LILETTA® (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) 52 mg for 5-year use. This approval is based on efficacy and safety data from ACCESS IUS, the largest ongoing intrauterine device (IUD) Phase 3 clinical trial in the United States. Previously, LILETTA was indicated for use up to 4 years.

LILETTA continues to be greater than 99% effective in preventing pregnancy in a broad range of women, regardless of age, race, body mass index, or parity, according to Allergan and Medicines360. The extended duration and proven efficacy across a diverse population enables more women in the United States to obtain effective birth control, as the IUD is now available for a low cost at public health clinics.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.liletta.com

Continue to: ENDOMETRIAL ABLATION TECHNOLOGY

ENDOMETRIAL ABLATION TECHNOLOGY

AEGEA Medical introduces the AEGEA Vapor SystemTM, an innovative solution for endometrial ablation to treat menorrhagia.

The system uses Adaptive Vapor Ablation and is the first endometrial ablation system specifically designed for use in the doctor’s office, allowing minimal anesthesia/analgesia and rapid recovery, says AEGEA Medical.

AEGEA Medical describes the AEGEA Vapor System as a fully automated safety monitoring and vapor delivery system that uses a slender, flexible Vapor Probe with SmartSealTM technology and the Integrity ProTM safety feature, for an added level of confidence. The 4-minute procedure time includes 2 minutes of vapor treatment and can be performed in patients with a wider range of uterine anatomies than indicated for use with currently available treatments, says AEGEA Medical.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://aegeamedical.com/

NATURAL CYCLES

The FDA has cleared Natural Cycles as the first digital method of birth control in the United States. Delivered in the form of an app, Natural Cycles is a fertility awareness–based contraceptive that uses a sophisticated algorithm to accurately and conveniently determine a woman’s daily fertility based on basal body temperature.

That data builds into a personalized fertility indicator that informs her when she needs to use protection to minimize the chance of conception. The app also can be used to help plan a pregnancy when the time is right, according to Natural Cycles.

A clinical study showed that the efficacy of a contraceptive mobile application is higher than usually reported for traditional fertility awareness–based methods. The application may contribute to reducing the unmet need for contraception, says Natural Cycles.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.naturalcycles.com/en/hcp

TREATMENT FOR VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS

BIJUVA™ has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved as the first oral treatment for moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms due to menopause in women with a uterus. BIJUVA offers a combination of bioidentical estradiol to reduce moderate-to-severe hot flashes and bioidentical progesterone to reduce the risk for endometrial hyperplasia.

TherapeuticsMD says that BIJUVA will be available Spring 2019 and is a proven treatment option for women who are experiencing bothersome symptoms of menopause, with clinical trial data demonstrating a statistically significant reduction in both the frequency and severity of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. The manufacturer also says that BIJUVA is developed to be identical in molecular structure to the hormones already produced by the body and is designed to help women restore what is lost during menopause.

BIJUVA estradiol and progesterone combination (1 mg/100 mg) will be available in capsule form.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT:https://bijuva.com/discover/

LILETTA USE EXTENDED