User login

Infant bronchiolitis subtype may predict asthma risk

Bronchiolitis is the leading cause of infant hospitalizations in the United States and Europe, and almost one-third of these patients go on to develop asthma later in childhood.

But a multinational team of researchers has presented evidence that could avoid that outcome. They identified four different subtypes of bronchiolitis along with a decision tree that can determine which infants are most likely to develop asthma as they get older.

Reporting in the journal eClinical Medicine, Michimasa Fujiogi, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, and colleagues analyzed three multicenter prospective cohort studies that included a combined 3,081 infants hospitalized with severe bronchiolitis.

“This study added a base for the early identification of high-risk patients during early infancy,” Dr. Fujiogi said in an interview. “Using the prediction rule of this study, it is possible to identify groups at high risk of asthma during a critical period of airway development – early infancy.”

The researchers identified four clinically distinct and reproducible profiles of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis:

- A: characterized by a history of breathing problems and eczema, rhinovirus infection, and low prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.

- B: characterized by the classic symptoms of wheezing and cough at presentation, a low prevalence of previous breathing problems and rhinovirus infection, and a high likelihood of RSV infection.

- C: the most severe group, characterized by inadequate oral intake, severe retraction at presentation, and longer hospital stays.

- D: the least ill group, with little history of breathing problems but inadequate oral intake with no or mild retraction.

Infants with profile A had the highest risk for developing asthma – more than 250% greater than with typical bronchiolitis. They were also older and were more likely to have parents who had asthma – and none had solo-RSV infection. In the overall analysis, the risk for developing asthma by age 6 or 7 was 23%.

The researchers stated that the decision tree accurately predicts the high-risk profile with high degrees of sensitivity and specificity. The decision tree used four predictors that together defined infants with profile A: RSV infection status, previous breathing problems, eczema, and parental asthma.

“Our data would facilitate the development of profile-specific prevention strategies for asthma – for example, modification of host response, prophylaxis for severe viral infection – by identifying asthma risk groups early in infancy,” Dr. Fujiogi said.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Fujiogi and coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bronchiolitis is the leading cause of infant hospitalizations in the United States and Europe, and almost one-third of these patients go on to develop asthma later in childhood.

But a multinational team of researchers has presented evidence that could avoid that outcome. They identified four different subtypes of bronchiolitis along with a decision tree that can determine which infants are most likely to develop asthma as they get older.

Reporting in the journal eClinical Medicine, Michimasa Fujiogi, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, and colleagues analyzed three multicenter prospective cohort studies that included a combined 3,081 infants hospitalized with severe bronchiolitis.

“This study added a base for the early identification of high-risk patients during early infancy,” Dr. Fujiogi said in an interview. “Using the prediction rule of this study, it is possible to identify groups at high risk of asthma during a critical period of airway development – early infancy.”

The researchers identified four clinically distinct and reproducible profiles of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis:

- A: characterized by a history of breathing problems and eczema, rhinovirus infection, and low prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.

- B: characterized by the classic symptoms of wheezing and cough at presentation, a low prevalence of previous breathing problems and rhinovirus infection, and a high likelihood of RSV infection.

- C: the most severe group, characterized by inadequate oral intake, severe retraction at presentation, and longer hospital stays.

- D: the least ill group, with little history of breathing problems but inadequate oral intake with no or mild retraction.

Infants with profile A had the highest risk for developing asthma – more than 250% greater than with typical bronchiolitis. They were also older and were more likely to have parents who had asthma – and none had solo-RSV infection. In the overall analysis, the risk for developing asthma by age 6 or 7 was 23%.

The researchers stated that the decision tree accurately predicts the high-risk profile with high degrees of sensitivity and specificity. The decision tree used four predictors that together defined infants with profile A: RSV infection status, previous breathing problems, eczema, and parental asthma.

“Our data would facilitate the development of profile-specific prevention strategies for asthma – for example, modification of host response, prophylaxis for severe viral infection – by identifying asthma risk groups early in infancy,” Dr. Fujiogi said.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Fujiogi and coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bronchiolitis is the leading cause of infant hospitalizations in the United States and Europe, and almost one-third of these patients go on to develop asthma later in childhood.

But a multinational team of researchers has presented evidence that could avoid that outcome. They identified four different subtypes of bronchiolitis along with a decision tree that can determine which infants are most likely to develop asthma as they get older.

Reporting in the journal eClinical Medicine, Michimasa Fujiogi, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, and colleagues analyzed three multicenter prospective cohort studies that included a combined 3,081 infants hospitalized with severe bronchiolitis.

“This study added a base for the early identification of high-risk patients during early infancy,” Dr. Fujiogi said in an interview. “Using the prediction rule of this study, it is possible to identify groups at high risk of asthma during a critical period of airway development – early infancy.”

The researchers identified four clinically distinct and reproducible profiles of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis:

- A: characterized by a history of breathing problems and eczema, rhinovirus infection, and low prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.

- B: characterized by the classic symptoms of wheezing and cough at presentation, a low prevalence of previous breathing problems and rhinovirus infection, and a high likelihood of RSV infection.

- C: the most severe group, characterized by inadequate oral intake, severe retraction at presentation, and longer hospital stays.

- D: the least ill group, with little history of breathing problems but inadequate oral intake with no or mild retraction.

Infants with profile A had the highest risk for developing asthma – more than 250% greater than with typical bronchiolitis. They were also older and were more likely to have parents who had asthma – and none had solo-RSV infection. In the overall analysis, the risk for developing asthma by age 6 or 7 was 23%.

The researchers stated that the decision tree accurately predicts the high-risk profile with high degrees of sensitivity and specificity. The decision tree used four predictors that together defined infants with profile A: RSV infection status, previous breathing problems, eczema, and parental asthma.

“Our data would facilitate the development of profile-specific prevention strategies for asthma – for example, modification of host response, prophylaxis for severe viral infection – by identifying asthma risk groups early in infancy,” Dr. Fujiogi said.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Fujiogi and coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Routine vaginal cleansing seen ineffective for unscheduled cesareans

Vaginal cleansing showed no reduction in morbidity when performed before unscheduled cesarean deliveries, researchers reported at the 2022 Pregnancy Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Several studies have evaluated vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery, with mixed results. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends clinicians consider cleansing prior to unscheduled cesareans, but that advice appears not to be widely heeded.

The new findings, from what the researchers called the single largest study of vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery in the United States, showed no difference in post-cesarean infections when the vagina was cleansed with povidone-iodine prior to unscheduled cesarean delivery.

“These findings do not support routine vaginal cleansing prior to unscheduled cesarean deliveries,” lead author Lorene Atkins Temming, MD, medical director of labor and delivery at Atrium Health Wake Forest School of Medicine, Charlotte, North Carolina, told this news organization. The research was conducted at and sponsored by Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, where Dr. Temming did her fellowship.

Dr. Temming’s group compared vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine in addition to routine abdominal cleansing to abdominal cleansing alone. Among the primary outcomes of the study was the effect of cleansing on post-cesarean infectious morbidity.

“There is a higher risk of infectious complications after cesarean delivery than other gynecologic surgeries,” Dr. Temming told this news organization. “While the reason for this isn’t entirely clear, it is thought to be because cesareans are often performed after a patient’s cervix is dilated. This dilation can allow normal bacteria that live in the vagina to ascend into the uterus and can increase the risk of infections.”

Patients undergoing cesarean delivery after labor were randomly assigned to undergo preoperative abdominal cleansing only (n = 304) or preoperative abdominal cleansing plus vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine (n = 304). Women were included in the analysis if they underwent cesareans after regular contractions and any cervical dilation, if their membranes ruptured, or if they had the procedure performed when they were more than 4 cm dilated.

The primary outcome was composite infectious morbidity, a catchall that included surgical-site infection, maternal fever, endometritis, and wound complications within 30 days after cesarean delivery. The secondary outcomes were hospital readmission, visits to the emergency department, and treatment for neonatal sepsis.

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary composite outcome between the two groups (11.7% vs. 11.7%, P = .98; 95% confidence interval, 0.6-1.5). “Vaginal cleansing appears to be unnecessary when preoperative antibiotics and skin antisepsis are performed,” Dr. Temming said.

Jennifer L. Lew, MD, an ob/gyn at Northwestern Medicine Kishwaukee Hospital in Dekalb, Illinois, said current practice regarding preparation for unscheduled cesarean surgery includes chlorhexidine on the abdomen and povidone-iodine for introducing a Foley catheter into the urethra.

“Many patients may already have a catheter in place due to labor and epidural, so they would not need” vaginal prep, Dr. Lew said. “Currently, the standard does not require doing a vaginal prep for any cesarean sections, those in labor or not.”

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaginal cleansing showed no reduction in morbidity when performed before unscheduled cesarean deliveries, researchers reported at the 2022 Pregnancy Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Several studies have evaluated vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery, with mixed results. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends clinicians consider cleansing prior to unscheduled cesareans, but that advice appears not to be widely heeded.

The new findings, from what the researchers called the single largest study of vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery in the United States, showed no difference in post-cesarean infections when the vagina was cleansed with povidone-iodine prior to unscheduled cesarean delivery.

“These findings do not support routine vaginal cleansing prior to unscheduled cesarean deliveries,” lead author Lorene Atkins Temming, MD, medical director of labor and delivery at Atrium Health Wake Forest School of Medicine, Charlotte, North Carolina, told this news organization. The research was conducted at and sponsored by Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, where Dr. Temming did her fellowship.

Dr. Temming’s group compared vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine in addition to routine abdominal cleansing to abdominal cleansing alone. Among the primary outcomes of the study was the effect of cleansing on post-cesarean infectious morbidity.

“There is a higher risk of infectious complications after cesarean delivery than other gynecologic surgeries,” Dr. Temming told this news organization. “While the reason for this isn’t entirely clear, it is thought to be because cesareans are often performed after a patient’s cervix is dilated. This dilation can allow normal bacteria that live in the vagina to ascend into the uterus and can increase the risk of infections.”

Patients undergoing cesarean delivery after labor were randomly assigned to undergo preoperative abdominal cleansing only (n = 304) or preoperative abdominal cleansing plus vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine (n = 304). Women were included in the analysis if they underwent cesareans after regular contractions and any cervical dilation, if their membranes ruptured, or if they had the procedure performed when they were more than 4 cm dilated.

The primary outcome was composite infectious morbidity, a catchall that included surgical-site infection, maternal fever, endometritis, and wound complications within 30 days after cesarean delivery. The secondary outcomes were hospital readmission, visits to the emergency department, and treatment for neonatal sepsis.

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary composite outcome between the two groups (11.7% vs. 11.7%, P = .98; 95% confidence interval, 0.6-1.5). “Vaginal cleansing appears to be unnecessary when preoperative antibiotics and skin antisepsis are performed,” Dr. Temming said.

Jennifer L. Lew, MD, an ob/gyn at Northwestern Medicine Kishwaukee Hospital in Dekalb, Illinois, said current practice regarding preparation for unscheduled cesarean surgery includes chlorhexidine on the abdomen and povidone-iodine for introducing a Foley catheter into the urethra.

“Many patients may already have a catheter in place due to labor and epidural, so they would not need” vaginal prep, Dr. Lew said. “Currently, the standard does not require doing a vaginal prep for any cesarean sections, those in labor or not.”

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaginal cleansing showed no reduction in morbidity when performed before unscheduled cesarean deliveries, researchers reported at the 2022 Pregnancy Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Several studies have evaluated vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery, with mixed results. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends clinicians consider cleansing prior to unscheduled cesareans, but that advice appears not to be widely heeded.

The new findings, from what the researchers called the single largest study of vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery in the United States, showed no difference in post-cesarean infections when the vagina was cleansed with povidone-iodine prior to unscheduled cesarean delivery.

“These findings do not support routine vaginal cleansing prior to unscheduled cesarean deliveries,” lead author Lorene Atkins Temming, MD, medical director of labor and delivery at Atrium Health Wake Forest School of Medicine, Charlotte, North Carolina, told this news organization. The research was conducted at and sponsored by Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, where Dr. Temming did her fellowship.

Dr. Temming’s group compared vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine in addition to routine abdominal cleansing to abdominal cleansing alone. Among the primary outcomes of the study was the effect of cleansing on post-cesarean infectious morbidity.

“There is a higher risk of infectious complications after cesarean delivery than other gynecologic surgeries,” Dr. Temming told this news organization. “While the reason for this isn’t entirely clear, it is thought to be because cesareans are often performed after a patient’s cervix is dilated. This dilation can allow normal bacteria that live in the vagina to ascend into the uterus and can increase the risk of infections.”

Patients undergoing cesarean delivery after labor were randomly assigned to undergo preoperative abdominal cleansing only (n = 304) or preoperative abdominal cleansing plus vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine (n = 304). Women were included in the analysis if they underwent cesareans after regular contractions and any cervical dilation, if their membranes ruptured, or if they had the procedure performed when they were more than 4 cm dilated.

The primary outcome was composite infectious morbidity, a catchall that included surgical-site infection, maternal fever, endometritis, and wound complications within 30 days after cesarean delivery. The secondary outcomes were hospital readmission, visits to the emergency department, and treatment for neonatal sepsis.

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary composite outcome between the two groups (11.7% vs. 11.7%, P = .98; 95% confidence interval, 0.6-1.5). “Vaginal cleansing appears to be unnecessary when preoperative antibiotics and skin antisepsis are performed,” Dr. Temming said.

Jennifer L. Lew, MD, an ob/gyn at Northwestern Medicine Kishwaukee Hospital in Dekalb, Illinois, said current practice regarding preparation for unscheduled cesarean surgery includes chlorhexidine on the abdomen and povidone-iodine for introducing a Foley catheter into the urethra.

“Many patients may already have a catheter in place due to labor and epidural, so they would not need” vaginal prep, Dr. Lew said. “Currently, the standard does not require doing a vaginal prep for any cesarean sections, those in labor or not.”

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Indurated Violaceous Lesions on the Face, Trunk, and Legs

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

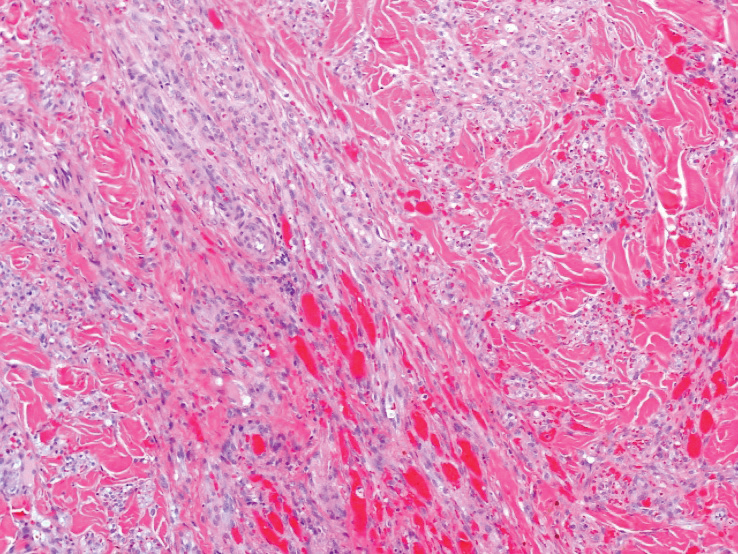

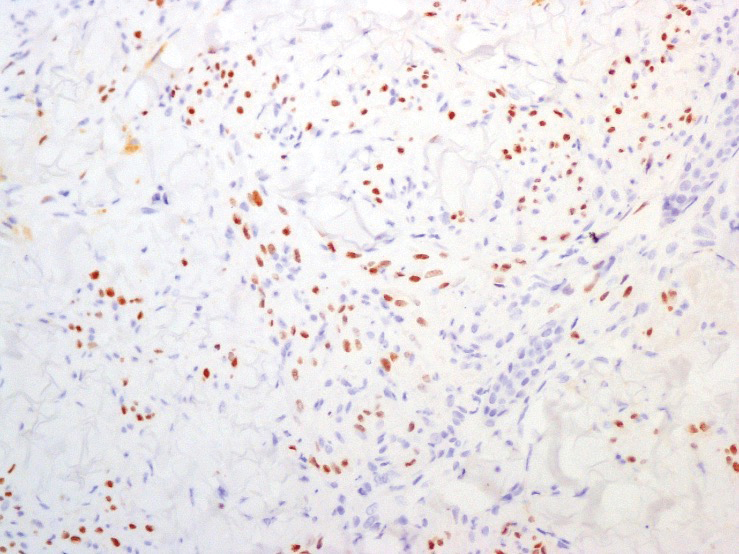

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

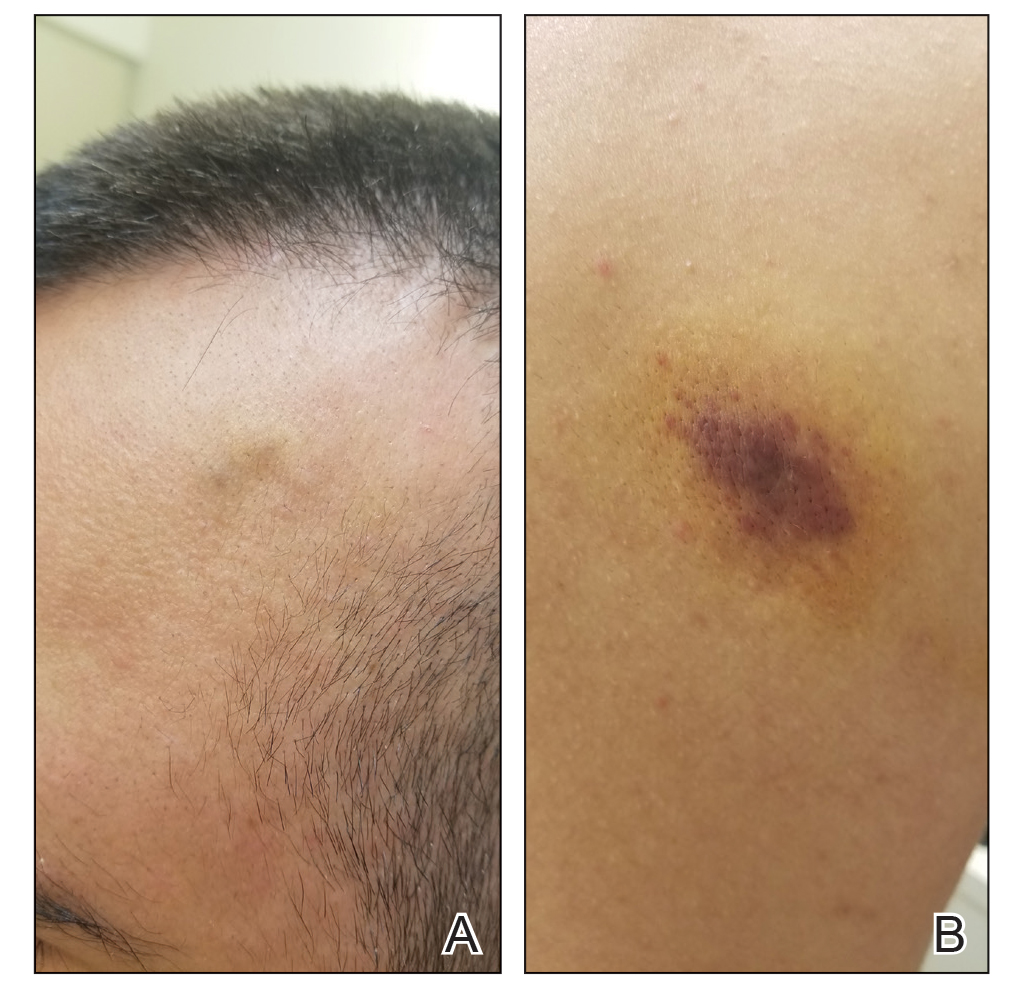

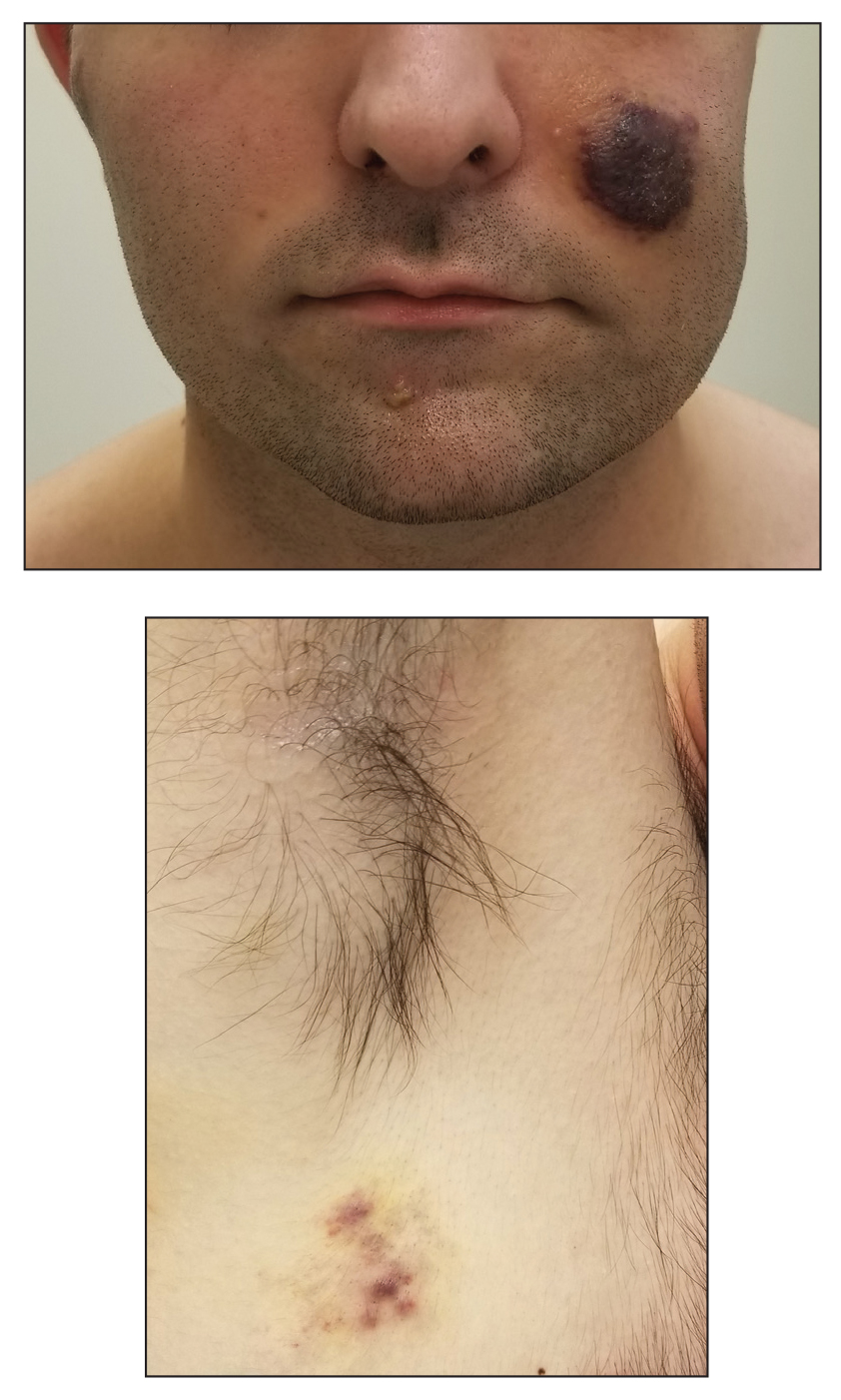

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

A 25-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with growing selfdescribed cysts on the face, trunk, and legs of 6 months’ duration. The lesions started as bruiselike discolorations and progressed to become firm nodules and inflamed masses. Some were minimally itchy and sensitive to touch, but there was no history of bleeding or drainage. The patient denied any new or recent environmental or animal exposures, use of illicit drugs, or travel correlating with the rash onset. He denied any prior treatments. He reported being in his normal state of health and was not taking any medications. Physical examination revealed indurated, violaceous, purpuric subcutaneous nodules, plaques, and masses on the forehead, cheek (top), jaw, flank, axillae (bottom), and back.

Mosquito nets do prevent malaria, longitudinal study confirms

It seems obvious that increased use of mosquito bed nets in sub-Saharan Africa would decrease the incidence of malaria, but a lingering question remained:

Malaria from Plasmodium falciparum infection exacts a significant toll in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were about 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 alone. About 80% of those deaths were in children less than 5 years old. In some areas, as many as 5% of children die from malaria by age 5.

Efforts to reduce the burden of malaria have been ongoing for decades. In the 1990s, insecticide-treated nets were shown to reduce illness and deaths from malaria in children.

As a result, the use of bed nets has grown significantly. In 2000, only 5% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had a net in the house. By 2020, that number had risen to 65%. From 2004 to 2019 about 1.9 billion nets were distributed in this region. The nets are estimated to have prevented more than 663 million malaria cases between 2000 and 2015.

As described in the NEJM report, public health researchers conducted a 22-year prospective longitudinal cohort study in rural southern Tanzania following 6,706 children born between 1998 and 2000. Initially, home visits were made every 4 months from May 1998 to April 2003. Remarkably, in 2019, they were able to verify the status of fully 89% of those people by reaching out to families and community/village leaders.

Günther Fink, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and household economics, University of Basel (Switzerland), explained the approach and primary findings to this news organization. The analysis looked at three main groups – children whose parents said they always slept under treated nets, those who slept protected most of the time, and those who spent less than half the time under bed nets. The hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.72) for the first two groups, compared with the least protected. The corresponding hazard ratio between age 5 and adulthood was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.58-1.49).

The findings confirmed what they had suspected. Dr. Fink summarized simply, “If you always slept under a net, you did much better than if you never slept under the net. If you slept [under a net] more than half of the time, it was much better than if you slept [under a net] less than half the time.” So the more time children slept under bed nets, the less likely they were to acquire malaria. Dr. Fink stressed that the findings showing protective efficacy persisted into adulthood. “It seems just having a healthier early life actually makes you more resilient against other future infections.”

One of the theoretical concerns was that using nets would delay developing functional immunity and that there might be an increase in mortality seen later. This study showed that did not happen.

An accompanying commentary noted that there was some potential that families receiving nets were better off than those that didn’t but concluded that such confounding had been accounted for in other analyses.

Mark Wilson, ScD, professor emeritus of epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, concurred. He told this news organization that the study was “very well designed,” and the researchers “did a fantastic job” in tracking patients 20 years later.

“This is astounding!” he added. “It’s very rare to find this amount of follow-up.”

Dr. Fink’s conclusion? “Bed nets protect you in the short run, and being protected in the short run is also beneficial in the long run. There is no evidence that protecting kids in early childhood is weakening them in any way. So we should keep doing this.”

Dr. Fink and Dr. Wilson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It seems obvious that increased use of mosquito bed nets in sub-Saharan Africa would decrease the incidence of malaria, but a lingering question remained:

Malaria from Plasmodium falciparum infection exacts a significant toll in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were about 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 alone. About 80% of those deaths were in children less than 5 years old. In some areas, as many as 5% of children die from malaria by age 5.

Efforts to reduce the burden of malaria have been ongoing for decades. In the 1990s, insecticide-treated nets were shown to reduce illness and deaths from malaria in children.

As a result, the use of bed nets has grown significantly. In 2000, only 5% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had a net in the house. By 2020, that number had risen to 65%. From 2004 to 2019 about 1.9 billion nets were distributed in this region. The nets are estimated to have prevented more than 663 million malaria cases between 2000 and 2015.

As described in the NEJM report, public health researchers conducted a 22-year prospective longitudinal cohort study in rural southern Tanzania following 6,706 children born between 1998 and 2000. Initially, home visits were made every 4 months from May 1998 to April 2003. Remarkably, in 2019, they were able to verify the status of fully 89% of those people by reaching out to families and community/village leaders.

Günther Fink, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and household economics, University of Basel (Switzerland), explained the approach and primary findings to this news organization. The analysis looked at three main groups – children whose parents said they always slept under treated nets, those who slept protected most of the time, and those who spent less than half the time under bed nets. The hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.72) for the first two groups, compared with the least protected. The corresponding hazard ratio between age 5 and adulthood was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.58-1.49).

The findings confirmed what they had suspected. Dr. Fink summarized simply, “If you always slept under a net, you did much better than if you never slept under the net. If you slept [under a net] more than half of the time, it was much better than if you slept [under a net] less than half the time.” So the more time children slept under bed nets, the less likely they were to acquire malaria. Dr. Fink stressed that the findings showing protective efficacy persisted into adulthood. “It seems just having a healthier early life actually makes you more resilient against other future infections.”

One of the theoretical concerns was that using nets would delay developing functional immunity and that there might be an increase in mortality seen later. This study showed that did not happen.

An accompanying commentary noted that there was some potential that families receiving nets were better off than those that didn’t but concluded that such confounding had been accounted for in other analyses.

Mark Wilson, ScD, professor emeritus of epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, concurred. He told this news organization that the study was “very well designed,” and the researchers “did a fantastic job” in tracking patients 20 years later.

“This is astounding!” he added. “It’s very rare to find this amount of follow-up.”

Dr. Fink’s conclusion? “Bed nets protect you in the short run, and being protected in the short run is also beneficial in the long run. There is no evidence that protecting kids in early childhood is weakening them in any way. So we should keep doing this.”

Dr. Fink and Dr. Wilson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It seems obvious that increased use of mosquito bed nets in sub-Saharan Africa would decrease the incidence of malaria, but a lingering question remained:

Malaria from Plasmodium falciparum infection exacts a significant toll in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were about 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 alone. About 80% of those deaths were in children less than 5 years old. In some areas, as many as 5% of children die from malaria by age 5.

Efforts to reduce the burden of malaria have been ongoing for decades. In the 1990s, insecticide-treated nets were shown to reduce illness and deaths from malaria in children.

As a result, the use of bed nets has grown significantly. In 2000, only 5% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had a net in the house. By 2020, that number had risen to 65%. From 2004 to 2019 about 1.9 billion nets were distributed in this region. The nets are estimated to have prevented more than 663 million malaria cases between 2000 and 2015.

As described in the NEJM report, public health researchers conducted a 22-year prospective longitudinal cohort study in rural southern Tanzania following 6,706 children born between 1998 and 2000. Initially, home visits were made every 4 months from May 1998 to April 2003. Remarkably, in 2019, they were able to verify the status of fully 89% of those people by reaching out to families and community/village leaders.

Günther Fink, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and household economics, University of Basel (Switzerland), explained the approach and primary findings to this news organization. The analysis looked at three main groups – children whose parents said they always slept under treated nets, those who slept protected most of the time, and those who spent less than half the time under bed nets. The hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.72) for the first two groups, compared with the least protected. The corresponding hazard ratio between age 5 and adulthood was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.58-1.49).

The findings confirmed what they had suspected. Dr. Fink summarized simply, “If you always slept under a net, you did much better than if you never slept under the net. If you slept [under a net] more than half of the time, it was much better than if you slept [under a net] less than half the time.” So the more time children slept under bed nets, the less likely they were to acquire malaria. Dr. Fink stressed that the findings showing protective efficacy persisted into adulthood. “It seems just having a healthier early life actually makes you more resilient against other future infections.”

One of the theoretical concerns was that using nets would delay developing functional immunity and that there might be an increase in mortality seen later. This study showed that did not happen.

An accompanying commentary noted that there was some potential that families receiving nets were better off than those that didn’t but concluded that such confounding had been accounted for in other analyses.

Mark Wilson, ScD, professor emeritus of epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, concurred. He told this news organization that the study was “very well designed,” and the researchers “did a fantastic job” in tracking patients 20 years later.

“This is astounding!” he added. “It’s very rare to find this amount of follow-up.”

Dr. Fink’s conclusion? “Bed nets protect you in the short run, and being protected in the short run is also beneficial in the long run. There is no evidence that protecting kids in early childhood is weakening them in any way. So we should keep doing this.”

Dr. Fink and Dr. Wilson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

FDA approves 2-month dosing of injectable HIV drug Cabenuva

Cabenuva was first approved by the FDA in January 2021 to be administered once monthly to treat HIV-1 infection in virologically suppressed adults. The medication was the first injectable complete antiretroviral regimen approved by the FDA.

Cabenuva can replace a current treatment in virologically suppressed adults on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and no known or suspected resistance to rilpivirine and cabotegravir, the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson said in a press release. Janssen and ViiV Healthcare codeveloped the injectable antiretroviral medication Cabenuva.

The expanded label approval “marks an important step forward in advancing the treatment landscape for people living with HIV,” said Candice Long, the president of infectious diseases and vaccines at Janssen Therapeutics, in a Feb. 1 press release. “With this milestone, adults living with HIV have a treatment option that further reduces the frequency of medication.”

This expanded approval was based on global clinical trial of 1,045 adults with HIV-1, which found Cabenuva administered every 8 weeks (3 mL dose of both cabotegravir and rilpivirine) to be noninferior to the 4-week regimen (2 mL dose of both medicines). At week 48 of the trial, the proportion of participants with viral loads above 50 copies per milliliter was 1.7% in the 2-month arm and 1.0% in the 1-month arm. The study found that rates of virological suppression were similar for both the 1-month and 2-month regimens (93.5% and 94.3%, respectively).

The most common side effects were injection site reactions, pyrexia, fatigue, headache, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, sleep disorders, dizziness, and rash. Adverse reactions reported in individuals receiving the regimen every 2 months or once monthly were similar. Cabenuva is contraindicated for patients with a hypersensitivity reaction to cabotegravir or rilpivirine or for those receiving carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, rifabutin, rifampin, rifapentine, St. John’s wort, and more than one dose of systemic dexamethasone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cabenuva was first approved by the FDA in January 2021 to be administered once monthly to treat HIV-1 infection in virologically suppressed adults. The medication was the first injectable complete antiretroviral regimen approved by the FDA.

Cabenuva can replace a current treatment in virologically suppressed adults on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and no known or suspected resistance to rilpivirine and cabotegravir, the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson said in a press release. Janssen and ViiV Healthcare codeveloped the injectable antiretroviral medication Cabenuva.

The expanded label approval “marks an important step forward in advancing the treatment landscape for people living with HIV,” said Candice Long, the president of infectious diseases and vaccines at Janssen Therapeutics, in a Feb. 1 press release. “With this milestone, adults living with HIV have a treatment option that further reduces the frequency of medication.”

This expanded approval was based on global clinical trial of 1,045 adults with HIV-1, which found Cabenuva administered every 8 weeks (3 mL dose of both cabotegravir and rilpivirine) to be noninferior to the 4-week regimen (2 mL dose of both medicines). At week 48 of the trial, the proportion of participants with viral loads above 50 copies per milliliter was 1.7% in the 2-month arm and 1.0% in the 1-month arm. The study found that rates of virological suppression were similar for both the 1-month and 2-month regimens (93.5% and 94.3%, respectively).

The most common side effects were injection site reactions, pyrexia, fatigue, headache, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, sleep disorders, dizziness, and rash. Adverse reactions reported in individuals receiving the regimen every 2 months or once monthly were similar. Cabenuva is contraindicated for patients with a hypersensitivity reaction to cabotegravir or rilpivirine or for those receiving carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, rifabutin, rifampin, rifapentine, St. John’s wort, and more than one dose of systemic dexamethasone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cabenuva was first approved by the FDA in January 2021 to be administered once monthly to treat HIV-1 infection in virologically suppressed adults. The medication was the first injectable complete antiretroviral regimen approved by the FDA.

Cabenuva can replace a current treatment in virologically suppressed adults on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and no known or suspected resistance to rilpivirine and cabotegravir, the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson said in a press release. Janssen and ViiV Healthcare codeveloped the injectable antiretroviral medication Cabenuva.

The expanded label approval “marks an important step forward in advancing the treatment landscape for people living with HIV,” said Candice Long, the president of infectious diseases and vaccines at Janssen Therapeutics, in a Feb. 1 press release. “With this milestone, adults living with HIV have a treatment option that further reduces the frequency of medication.”

This expanded approval was based on global clinical trial of 1,045 adults with HIV-1, which found Cabenuva administered every 8 weeks (3 mL dose of both cabotegravir and rilpivirine) to be noninferior to the 4-week regimen (2 mL dose of both medicines). At week 48 of the trial, the proportion of participants with viral loads above 50 copies per milliliter was 1.7% in the 2-month arm and 1.0% in the 1-month arm. The study found that rates of virological suppression were similar for both the 1-month and 2-month regimens (93.5% and 94.3%, respectively).

The most common side effects were injection site reactions, pyrexia, fatigue, headache, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, sleep disorders, dizziness, and rash. Adverse reactions reported in individuals receiving the regimen every 2 months or once monthly were similar. Cabenuva is contraindicated for patients with a hypersensitivity reaction to cabotegravir or rilpivirine or for those receiving carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, rifabutin, rifampin, rifapentine, St. John’s wort, and more than one dose of systemic dexamethasone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why do some people escape infection that sickens others?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve seen this play out time and time again when whole families get sick except for one or two fortunate family members. And at so-called superspreader events that infect many, a lucky few typically walk away with their health intact. Did the virus never enter their bodies? Or do some people have natural resistance to pathogens they’ve never been exposed to before encoded in their genes?

Resistance to infectious disease is much more than a scientific curiosity and studying how it works can be a path to curb future outbreaks.

“In the event that we could identify what makes some people resistant, that immediately opens avenues for therapeutics that we could apply in all those other people who do suffer from the disease,” says András Spaan, MD, a microbiologist at Rockefeller University in New York.

Dr. Spaan is part of an international effort to identify genetic variations that spare people from becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

There’s far more research on what drives the tendency to get infectious diseases than on resistance to them. But a few researchers are investigating resistance to some of the world’s most common and deadly infectious diseases, and in a few cases, they’ve already translated these insights into treatments.

Perhaps the strongest example of how odd genes of just a few people can inspire treatments to help many comes from research on the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

A genetic quirk

In the mid-1990s, several groups of researchers independently identified a mutation in a gene called CCR5 linked to resistance to HIV infection.

The gene encodes a protein on the surface of some white blood cells that helps set up the movement of other immune cells to fight infections. HIV, meanwhile, uses the CCR5 protein to help it enter the white blood cells that it infects.

The mutation, known as delta 32, results in a shorter than usual protein that doesn’t reach the surface of the cell. People who carry two copies of the delta 32 form of CCR5 do not have any CCR5 protein on the outside of their white blood cells.

Researchers, led by molecular immunologist Philip Murphy, MD, at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md, showed in 1997 that people with two copies of the mutation were unusually common among a group of men who were at especially high risk of HIV exposure, but had never contracted the virus. And out of more than 700 HIV-positive people, none carried two copies of CCR5 delta 32.

Pharmaceutical companies used these insights to develop drugs to block CCR5 and delay the development of AIDS. For instance, the drug maraviroc, marketed by Pfizer, was approved for use in HIV-positive people in 2007.

Only a few examples of this kind of inborn, genetically determined complete resistance to infection have ever been heard of. All of them involve cell-surface molecules that are believed to help a virus or other pathogen gain entry to the cell.

Locking out illness

“The first step for any intracellular pathogen is getting inside the cell. And if you’re missing the doorway, then the virus can’t accomplish the first step in its life cycle,” Dr. Murphy says. “Getting inside is fundamental.”

Changes in cell-surface molecules can also make someone more likely to have an infection or severe disease. One such group of cell-surface molecules that have been linked to both increasing and decreasing the risk of various infections are histo-blood group antigens. The most familiar members of this group are the molecules that define blood types A, B, and O.

Scientists have also identified one example of total resistance to infection involving these molecules. In 2003, researchers showed that people who lack a functional copy of a gene known as FUT2 cannot be infected with Norwalk virus, one of more than 30 viruses in the norovirus family that cause illness in the digestive tract.

The gene FUT2 encodes an enzyme that determines whether or not blood group antigens are found in a person’s saliva and other body fluids as well as on their red blood cells.

“It didn’t matter how many virus particles we challenged an individual with, if they did not have that first enzyme, they did not get infected,” says researcher Lisa Lindesmith, a virologist at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

No norovirus

Norwalk is a relatively rare type of norovirus. But FUT2 deficiency also provides some protection against the most common strains of norovirus, known as GII.4, which have periodically swept across the world over the past quarter-century. These illnesses take an especially heavy toll on children in the developing world, causing malnutrition and contributing to infant and child deaths.

But progress in translating these insights about genetic resistance into drugs or other things that could reduce the burden of noroviruses has been slow.

“The biggest barrier here is lack of ability to study the virus outside of humans,” Lindesmith says.

Noroviruses are very difficult to grow in the lab, “and there’s no small animal model of gastrointestinal illness caused by the viruses.”

We are clearly making giant strides in improving those skills,” says Lindesmith. “But we are just not quite there yet.”

In the years before COVID-19 emerged, tuberculosis was responsible for the largest number of annual worldwide deaths from an infectious disease. It’s a lung disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and it has been a pandemic for thousands of years.

Some 85%-95% of people with intact immune systems who are infected with TB control the infection and never get active lung disease. And some people who have intense, continuing exposure to the bacterium, which is spread through droplets and aerosols from people with active lung disease, apparently never become infected at all.

Thwarting uberculosis

Understanding the ways of these different forms of resistance could help in the search for vaccines, treatments, and other ways to fight tuberculosis, says Elouise Kroon, MD, a graduate student at Stellenbosch University in Cape Town, South Africa.

“What makes it particularly hard to study is the fact that there is no gold standard to measure infection,” she says. “So, what we do is infer infection from two different types of tests” -- a skin test and a blood test that measure different kinds of immune response to molecules from the bacterium.

Dr. Kroon and other researchers have studied resistance to infection by following people living in the same household as those with active lung disease or people who live and work in crowded conditions in high-risk communities. But not all such studies have used the same definition of so-called resisters, documented exposure in the same way, or followed up to ensure that people continue to test negative over the long term.

The best clue that has emerged from studies so far links resistance to infection to certain variations in immune molecules known as HLA class II antigens, says Marlo Möller, PhD, a professor in the TB Host Genetics Research Group at Stellenbosch University.

“That always seems to pop up everywhere. But the rest is not so obvious,” she says. “A lot of the studies don’t find the same thing. It’s different in different populations,” which may be a result of the long evolutionary history between tuberculosis and humans, as well as the fact that different strains of the bacterium are prevalent in different parts of the world.

COVID-19 is a much newer infectious disease, but teasing out how it contributes to both severe illness and resistance to infection is still a major task.

Overcoming COVID

Early in the pandemic, research by the COVID Human Genetic Effort, the international consortium that Dr. Spaan is part of, linked severe COVID-19 pneumonia to the lack of immune molecules known as type I interferons and to antibodies produced by the body that destroy these molecules. Together, these mechanisms explain about one-fifth of severe COVID-19 cases, the researchers reported in 2021.

A few studies by other groups have explored resistance to COVID-19 infection, suggesting that reduced risk of contracting the virus is tied to certain blood group factors. People with Type O blood appear to be at slightly reduced risk of infection, for example.

But the studies done so far are designed to find common genetic variations, which generally have a small effect on resistance. Now, genetic researchers are launching an effort to identify genetic resistance factors with a big effect, even if they are vanishingly rare.

The group is recruiting people who did not become infected with COVID-19 despite heavy exposure, such as those living in households where all the other members got sick or people who were exposed to a superspreader event but did not become ill. As with tuberculosis, being certain that someone has not been infected with the virus can be tricky, but the team is using several blood tests to home in on the people most likely to have escaped infection.

They plan to sequence the genomes of these people to identify things that strongly affect infection risk, then do more laboratory studies to try to tease out the means of resistance.

Their work is inspired by earlier efforts to uncover inborn resistance to infections, Dr. Spaan says. Despite the lack of known examples of such resistance, he is optimistic about the possibilities. Those earlier efforts took place in “a different epoch,” before there were rapid sequencing technologies, Dr. Spaan says.

“Now we have modern technologies to do this more systematically.”

The emergence of viral variants such as the Delta and Omicron COVID strains raises the stakes of the work, he continues.

“The need to unravel these inborn mechanisms of resistance to COVID has become even more important because of these new variants and the anticipation that we will have COVID with us for years.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve seen this play out time and time again when whole families get sick except for one or two fortunate family members. And at so-called superspreader events that infect many, a lucky few typically walk away with their health intact. Did the virus never enter their bodies? Or do some people have natural resistance to pathogens they’ve never been exposed to before encoded in their genes?

Resistance to infectious disease is much more than a scientific curiosity and studying how it works can be a path to curb future outbreaks.

“In the event that we could identify what makes some people resistant, that immediately opens avenues for therapeutics that we could apply in all those other people who do suffer from the disease,” says András Spaan, MD, a microbiologist at Rockefeller University in New York.

Dr. Spaan is part of an international effort to identify genetic variations that spare people from becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

There’s far more research on what drives the tendency to get infectious diseases than on resistance to them. But a few researchers are investigating resistance to some of the world’s most common and deadly infectious diseases, and in a few cases, they’ve already translated these insights into treatments.

Perhaps the strongest example of how odd genes of just a few people can inspire treatments to help many comes from research on the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

A genetic quirk

In the mid-1990s, several groups of researchers independently identified a mutation in a gene called CCR5 linked to resistance to HIV infection.

The gene encodes a protein on the surface of some white blood cells that helps set up the movement of other immune cells to fight infections. HIV, meanwhile, uses the CCR5 protein to help it enter the white blood cells that it infects.

The mutation, known as delta 32, results in a shorter than usual protein that doesn’t reach the surface of the cell. People who carry two copies of the delta 32 form of CCR5 do not have any CCR5 protein on the outside of their white blood cells.

Researchers, led by molecular immunologist Philip Murphy, MD, at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md, showed in 1997 that people with two copies of the mutation were unusually common among a group of men who were at especially high risk of HIV exposure, but had never contracted the virus. And out of more than 700 HIV-positive people, none carried two copies of CCR5 delta 32.

Pharmaceutical companies used these insights to develop drugs to block CCR5 and delay the development of AIDS. For instance, the drug maraviroc, marketed by Pfizer, was approved for use in HIV-positive people in 2007.

Only a few examples of this kind of inborn, genetically determined complete resistance to infection have ever been heard of. All of them involve cell-surface molecules that are believed to help a virus or other pathogen gain entry to the cell.

Locking out illness

“The first step for any intracellular pathogen is getting inside the cell. And if you’re missing the doorway, then the virus can’t accomplish the first step in its life cycle,” Dr. Murphy says. “Getting inside is fundamental.”

Changes in cell-surface molecules can also make someone more likely to have an infection or severe disease. One such group of cell-surface molecules that have been linked to both increasing and decreasing the risk of various infections are histo-blood group antigens. The most familiar members of this group are the molecules that define blood types A, B, and O.

Scientists have also identified one example of total resistance to infection involving these molecules. In 2003, researchers showed that people who lack a functional copy of a gene known as FUT2 cannot be infected with Norwalk virus, one of more than 30 viruses in the norovirus family that cause illness in the digestive tract.

The gene FUT2 encodes an enzyme that determines whether or not blood group antigens are found in a person’s saliva and other body fluids as well as on their red blood cells.

“It didn’t matter how many virus particles we challenged an individual with, if they did not have that first enzyme, they did not get infected,” says researcher Lisa Lindesmith, a virologist at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

No norovirus

Norwalk is a relatively rare type of norovirus. But FUT2 deficiency also provides some protection against the most common strains of norovirus, known as GII.4, which have periodically swept across the world over the past quarter-century. These illnesses take an especially heavy toll on children in the developing world, causing malnutrition and contributing to infant and child deaths.

But progress in translating these insights about genetic resistance into drugs or other things that could reduce the burden of noroviruses has been slow.

“The biggest barrier here is lack of ability to study the virus outside of humans,” Lindesmith says.

Noroviruses are very difficult to grow in the lab, “and there’s no small animal model of gastrointestinal illness caused by the viruses.”

We are clearly making giant strides in improving those skills,” says Lindesmith. “But we are just not quite there yet.”

In the years before COVID-19 emerged, tuberculosis was responsible for the largest number of annual worldwide deaths from an infectious disease. It’s a lung disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and it has been a pandemic for thousands of years.

Some 85%-95% of people with intact immune systems who are infected with TB control the infection and never get active lung disease. And some people who have intense, continuing exposure to the bacterium, which is spread through droplets and aerosols from people with active lung disease, apparently never become infected at all.

Thwarting uberculosis

Understanding the ways of these different forms of resistance could help in the search for vaccines, treatments, and other ways to fight tuberculosis, says Elouise Kroon, MD, a graduate student at Stellenbosch University in Cape Town, South Africa.

“What makes it particularly hard to study is the fact that there is no gold standard to measure infection,” she says. “So, what we do is infer infection from two different types of tests” -- a skin test and a blood test that measure different kinds of immune response to molecules from the bacterium.

Dr. Kroon and other researchers have studied resistance to infection by following people living in the same household as those with active lung disease or people who live and work in crowded conditions in high-risk communities. But not all such studies have used the same definition of so-called resisters, documented exposure in the same way, or followed up to ensure that people continue to test negative over the long term.

The best clue that has emerged from studies so far links resistance to infection to certain variations in immune molecules known as HLA class II antigens, says Marlo Möller, PhD, a professor in the TB Host Genetics Research Group at Stellenbosch University.

“That always seems to pop up everywhere. But the rest is not so obvious,” she says. “A lot of the studies don’t find the same thing. It’s different in different populations,” which may be a result of the long evolutionary history between tuberculosis and humans, as well as the fact that different strains of the bacterium are prevalent in different parts of the world.

COVID-19 is a much newer infectious disease, but teasing out how it contributes to both severe illness and resistance to infection is still a major task.

Overcoming COVID

Early in the pandemic, research by the COVID Human Genetic Effort, the international consortium that Dr. Spaan is part of, linked severe COVID-19 pneumonia to the lack of immune molecules known as type I interferons and to antibodies produced by the body that destroy these molecules. Together, these mechanisms explain about one-fifth of severe COVID-19 cases, the researchers reported in 2021.

A few studies by other groups have explored resistance to COVID-19 infection, suggesting that reduced risk of contracting the virus is tied to certain blood group factors. People with Type O blood appear to be at slightly reduced risk of infection, for example.

But the studies done so far are designed to find common genetic variations, which generally have a small effect on resistance. Now, genetic researchers are launching an effort to identify genetic resistance factors with a big effect, even if they are vanishingly rare.

The group is recruiting people who did not become infected with COVID-19 despite heavy exposure, such as those living in households where all the other members got sick or people who were exposed to a superspreader event but did not become ill. As with tuberculosis, being certain that someone has not been infected with the virus can be tricky, but the team is using several blood tests to home in on the people most likely to have escaped infection.

They plan to sequence the genomes of these people to identify things that strongly affect infection risk, then do more laboratory studies to try to tease out the means of resistance.

Their work is inspired by earlier efforts to uncover inborn resistance to infections, Dr. Spaan says. Despite the lack of known examples of such resistance, he is optimistic about the possibilities. Those earlier efforts took place in “a different epoch,” before there were rapid sequencing technologies, Dr. Spaan says.

“Now we have modern technologies to do this more systematically.”

The emergence of viral variants such as the Delta and Omicron COVID strains raises the stakes of the work, he continues.

“The need to unravel these inborn mechanisms of resistance to COVID has become even more important because of these new variants and the anticipation that we will have COVID with us for years.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve seen this play out time and time again when whole families get sick except for one or two fortunate family members. And at so-called superspreader events that infect many, a lucky few typically walk away with their health intact. Did the virus never enter their bodies? Or do some people have natural resistance to pathogens they’ve never been exposed to before encoded in their genes?

Resistance to infectious disease is much more than a scientific curiosity and studying how it works can be a path to curb future outbreaks.

“In the event that we could identify what makes some people resistant, that immediately opens avenues for therapeutics that we could apply in all those other people who do suffer from the disease,” says András Spaan, MD, a microbiologist at Rockefeller University in New York.

Dr. Spaan is part of an international effort to identify genetic variations that spare people from becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

There’s far more research on what drives the tendency to get infectious diseases than on resistance to them. But a few researchers are investigating resistance to some of the world’s most common and deadly infectious diseases, and in a few cases, they’ve already translated these insights into treatments.

Perhaps the strongest example of how odd genes of just a few people can inspire treatments to help many comes from research on the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

A genetic quirk

In the mid-1990s, several groups of researchers independently identified a mutation in a gene called CCR5 linked to resistance to HIV infection.

The gene encodes a protein on the surface of some white blood cells that helps set up the movement of other immune cells to fight infections. HIV, meanwhile, uses the CCR5 protein to help it enter the white blood cells that it infects.

The mutation, known as delta 32, results in a shorter than usual protein that doesn’t reach the surface of the cell. People who carry two copies of the delta 32 form of CCR5 do not have any CCR5 protein on the outside of their white blood cells.

Researchers, led by molecular immunologist Philip Murphy, MD, at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md, showed in 1997 that people with two copies of the mutation were unusually common among a group of men who were at especially high risk of HIV exposure, but had never contracted the virus. And out of more than 700 HIV-positive people, none carried two copies of CCR5 delta 32.

Pharmaceutical companies used these insights to develop drugs to block CCR5 and delay the development of AIDS. For instance, the drug maraviroc, marketed by Pfizer, was approved for use in HIV-positive people in 2007.

Only a few examples of this kind of inborn, genetically determined complete resistance to infection have ever been heard of. All of them involve cell-surface molecules that are believed to help a virus or other pathogen gain entry to the cell.

Locking out illness

“The first step for any intracellular pathogen is getting inside the cell. And if you’re missing the doorway, then the virus can’t accomplish the first step in its life cycle,” Dr. Murphy says. “Getting inside is fundamental.”

Changes in cell-surface molecules can also make someone more likely to have an infection or severe disease. One such group of cell-surface molecules that have been linked to both increasing and decreasing the risk of various infections are histo-blood group antigens. The most familiar members of this group are the molecules that define blood types A, B, and O.

Scientists have also identified one example of total resistance to infection involving these molecules. In 2003, researchers showed that people who lack a functional copy of a gene known as FUT2 cannot be infected with Norwalk virus, one of more than 30 viruses in the norovirus family that cause illness in the digestive tract.

The gene FUT2 encodes an enzyme that determines whether or not blood group antigens are found in a person’s saliva and other body fluids as well as on their red blood cells.

“It didn’t matter how many virus particles we challenged an individual with, if they did not have that first enzyme, they did not get infected,” says researcher Lisa Lindesmith, a virologist at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

No norovirus

Norwalk is a relatively rare type of norovirus. But FUT2 deficiency also provides some protection against the most common strains of norovirus, known as GII.4, which have periodically swept across the world over the past quarter-century. These illnesses take an especially heavy toll on children in the developing world, causing malnutrition and contributing to infant and child deaths.