User login

Successful COVID-19 Surge Management With Monoclonal Antibody Infusion in Emergency Department Patients

From the Center for Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA (Drs. Chow and Chang, Mazaya Soundara), University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, CA (Ruchi Desai), Division of Infectious Diseases, University of California, Irvine, CA (Dr. Gohil), and the Department of Medicine and Hospital Medicine Program, University of California, Irvine, CA (Dr. Amin).

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has placed substantial strain on hospital resources and has been responsible for more than 733 000 deaths in the United States. The US Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy in the US for patients with early-stage high-risk COVID-19.

Methods: In this retrospective cohort study, we studied the emergency department (ED) during a massive COVID-19 surge in Orange County, California, from December 4, 2020, to January 29, 2021, as a potential setting for efficient mAb delivery by evaluating the impact of bamlanivimab use in high-risk COVID-19 patients. All patients included in this study had positive results on nucleic acid amplification detection from nasopharyngeal or throat swabs, presented with 1 or more mild or moderate symptom, and met EUA criteria for mAb treatment. The primary outcome analyzed among this cohort of ED patients was overall improvement, which included subsequent ED/hospital visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death related to COVID-19.

Results: We identified 1278 ED patients with COVID-19 not treated with bamlanivimab and 73 patients with COVID-19 treated with bamlanivimab during the treatment period. Of these patients, 239 control patients and 63 treatment patients met EUA criteria. Overall, 7.9% (5/63) of patients receiving bamlanivimab had a subsequent ED/hospital visit, hospitalization, or death compared with 19.2% (46/239) in the control group (P = .03).

Conclusion: Targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 illness and substantially reduce the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially for individuals of underserved populations who may not have access to ambulatory care.

Keywords: COVID-19; mAb; bamlanivimab; surge management.

Since December 2019, the novel pathogen SARS-CoV-2 has spread rapidly, culminating in a pandemic that has caused more than 4.9 million deaths worldwide and claimed more than 733 000 lives in the United States.1 The scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has placed an immense strain on hospital resources, including personal protective equipment (PPE), beds, ventilators and personnel.2,3 A previous analysis demonstrated that hospital capacity strain is associated with increased mortality and worsened health outcomes.4 A more recent analysis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic found that strains on critical care capacity were associated with increased COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) mortality.5 While more studies are needed to understand the association between hospital resources and COVID-19 mortality, efforts to decrease COVID-19 hospitalizations by early targeted treatment of patients in outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings may help to relieve the burden on hospital personnel and resources and decrease subsequent mortality.

Current therapeutic options focus on inpatient management of patients who progress to acute respiratory illness while patients with mild presentations are managed with outpatient monitoring, even those at high risk for progression. At the moment, only remdesivir, a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.6 However, in November 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), monotherapy, and combination therapy in a broad range of early-stage, high-risk patients.7-9 Neutralizing mAbs include bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555), etesevimab (LY-CoV016), sotrovimab (VIR-7831), and casirivimab/imdevimab (REGN-COV2). These anti–spike protein antibodies prevent viral attachment to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (hACE2) and subsequently prevent viral entry.10 mAb therapy has been shown to be effective in substantially reducing viral load, hospitalizations, and ED visits.11

Despite these promising results, uptake of mAb therapy has been slow, with more than 600 000 available doses remaining unused as of mid-January 2021, despite very high infection rates across the United States.12 In addition to the logistical challenges associated with intravenous (IV) therapy in the ambulatory setting, identifying, notifying, and scheduling appointments for ambulatory patients hamper efficient delivery to high-risk patients and limit access to underserved patients without primary care providers. For patients not treated in the ambulatory setting, the ED may serve as an ideal location for early implementation of mAb treatment in high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

The University of California, Irvine (UCI) Medical Center is not only the major premium academic medical center in Orange County, California, but also the primary safety net hospital for vulnerable populations in Orange County. During the surge period from December 2020 through January 2021, we were over 100% capacity and had built an onsite mobile hospital to expand the number of beds available. Given the severity of the impact of COVID-19 on our resources, implementing a strategy to reduce hospital admissions, patient death, and subsequent ED visits was imperative. Our goal was to implement a strategy on the front end through the ED to optimize care for patients and reduce the strain on hospital resources.

We sought to study the ED during this massive surge as a potential setting for efficient mAb delivery by evaluating the impact of bamlanivimab use in high risk COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study (approved by UCI institutional review board) of sequential COVID-19 adult patients who were evaluated and discharged from the ED between December 4, 2020, and January 29, 2021, and received bamlanivimab treatment (cases) compared with a nontreatment group (control) of ED patients.

Using the UCI electronic medical record (EMR) system, we identified 1278 ED patients with COVID-19 not treated with bamlanivimab and 73 patients with COVID-19 treated with bamlanivimab during the months of December 2020 and January 2021. All patients included in this study met the EUA criteria for mAb therapy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), during the period of this study, patients met EUA criteria if they had mild to moderate COVID-19, a positive direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and a high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 or hospitalization.13 High risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 and/or hospitalization is defined as meeting at least 1 of the following criteria: a body mass index of 35 or higher, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes, immunosuppressive disease, currently receiving immunosuppressive treatment, aged 65 years or older, aged 55 years or older and have cardiovascular disease or hypertension, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/other chronic respiratory diseases.13 All patients in the ED who met EUA criteria were offered mAb treatment; those who accepted the treatment were included in the treatment group, and those who refused were included in the control group.

All patients included in this study had positive results on nucleic acid amplification detection from nasopharyngeal or throat swabs and presented with 1 or more mild or moderate symptom, defined as: fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, or shortness of breath. We excluded patients admitted to the hospital on that ED visit and those discharged to hospice. In addition, we excluded patients who presented 2 weeks after symptom onset and those who did not meet EUA criteria. Demographic data (age and gender) and comorbid conditions were obtained by EMR review. Comorbid conditions obtained included diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease, CKD/end-stage renal disease (ESRD), COPD, obesity, and immunocompromised status.

Bamlanivimab infusion therapy in the ED followed CDC guidelines. Each patient received 700 mg of bamlanivimab diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride and administered as a single IV infusion. We established protocols to give patients IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions directly in the ED.

The primary outcome analyzed among this cohort of ED patients was overall improvement, which included subsequent ED/hospital visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death related to COVID-19 within 90 days of initial ED visit. Each patient was only counted once. Data analysis and statistical tests were conducted using SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc). Treatment effects were compared using χ2 test with an α level of 0.05. A t test was used for continuous variables, including age. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

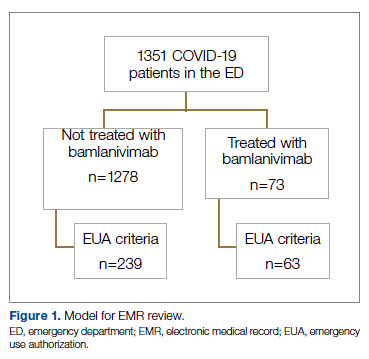

We screened a total of 1351 patients with COVID-19. Of these, 1278 patients did not receive treatment with bamlanivimab. Two hundred thirty-nine patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the control group. Seventy-three patients were treated with bamlanivimab in the ED; 63 of these patients met EUA criteria and comprised the treatment group (Figure 1).

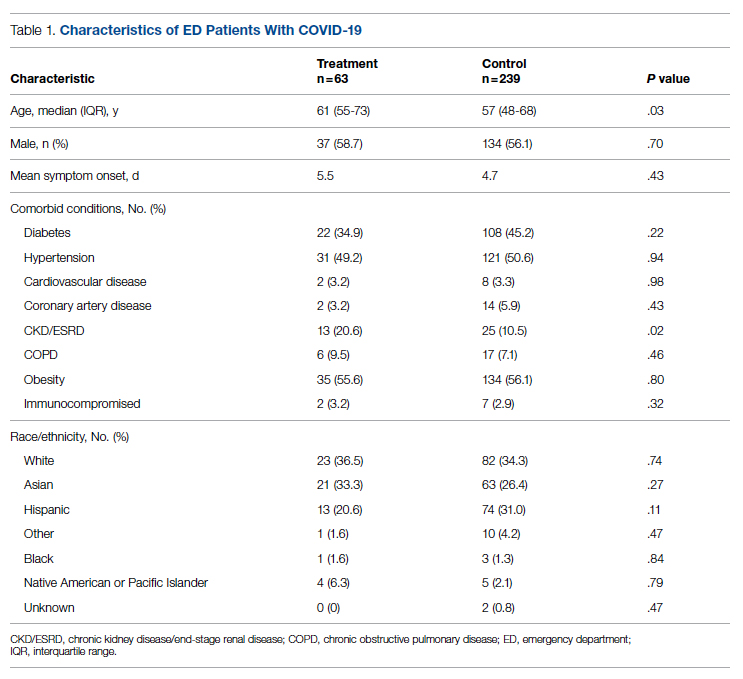

Demographic details of the trial groups are provided in Table 1. The median age of the treatment group was 61 years (interquartile range [IQR], 55-73), while the median age of the control group was 57 years (IQR, 48-68). The difference in median age between the treatment and control individuals was significantly different (P = .03). There was no significant difference found in terms of gender between the control and treatment groups (P = .07). In addition, no significant difference was seen among racial and ethnic groups in the control and treatment groups. Comorbidities and demographics of all patients in the treatment and control groups are provided in Table 1. The only comorbidity that was found to be significantly different between the treatment and control groups was CKD/ESRD. Among those treated with bamlanivimab, 20.6% (13/63) had CKD/ESRD compared with 10.5% (25/239) in the control group (P = .02).

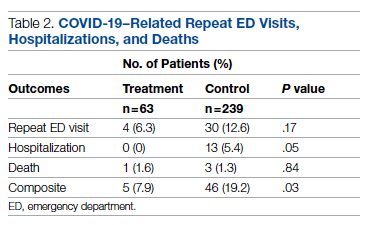

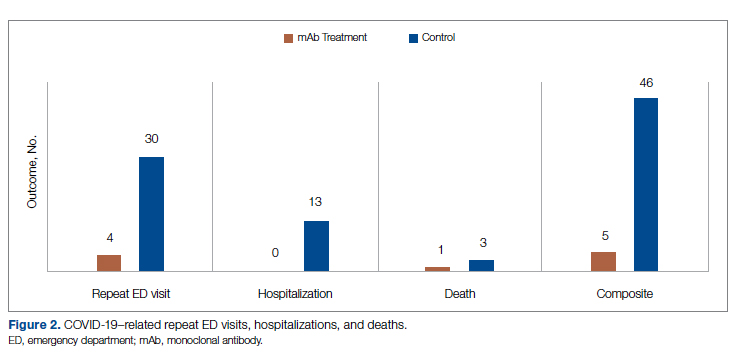

Overall, 7.9% (5/63) of patients receiving bamlanivimab had a subsequent ED/hospital visit, hospitalization, or death compared with 19.2% (46/239) in the control group (P = .03) (Table 2).

While the primary outcome of overall improvement was significantly different between the 2 groups, comparison of the individual components, including subsequent ED visits, hospitalizations, or death, were not significant. No treatment patients were hospitalized, compared with 5.4% (13/239) in the control group (P = .05). In the treatment group, 6.3% (4/63) returned to the ED compared with 12.6% (30/239) of the control group (P = .17). Finally, 1.6% (1/63) of the treatment group had a subsequent death that was due to COVID-19 compared with 1.3% (3/239) in the control group (P = .84) (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, we observed a significant difference in rates of COVID-19 patients requiring repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths among those who received bamlanivimab compared with those who did not. Our study focused on high-risk patients with mild or moderate COVID-19, a unique subset of individuals who would normally be followed and treated via outpatient monitoring. We propose that treating high-risk patients earlier in their disease process with mAb therapy can have a major impact on overall outcomes, as defined by decreased subsequent hospitalizations, ED visits, and death.

Compared to clinical trials such as BLAZE-1 or REGN-COV2, every patient in this trial had at least 1 high-risk characteristic.9,11 This may explain why a greater proportion of our patients in both the control and treatment groups had subsequent hospitalization, ED visits, and deaths. COVID-19 patients seen in the ED may be a uniquely self-selected population of individuals likely to benefit from mAb therapy since they may be more likely to be sicker, have more comorbidities, or have less readily available primary care access for testing and treatment.14

Despite conducting a thorough literature review, we were unable to find any similar studies describing the ED as an appropriate setting for mAb treatment in patients with COVID-19. Multiple studies have used outpatient clinics as a setting for mAb treatment, and 1 retrospective analysis found that neutralizing mAb treatment in COVID-19 patients in an outpatient setting reduced hospital utilization.15 However, many Americans do not have access to primary care, with 1 study finding that only 75% of Americans had an identified source of primary care in 2015.16 Obstacles to primary care access include disabilities, lack of health insurance, language-related barriers, race/ethnicity, and homelessness.17 Barriers to access for primary care services and timely care make these populations more likely to frequent the ED.17 This makes the ED a unique location for early and targeted treatment of COVID-19 patients with a high risk for progression to severe COVID-19.

During surge periods in the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals met capacity or superseded their capacity for patients, with 4423 hospitals reporting more than 90% of hospital beds occupied and 2591 reporting more than 90% of ICU beds occupied during the peak surge week of January 1, 2021, to January 7, 2021.18 The main goals of lockdowns and masking have been to decrease the transmission of COVID-19 and hopefully flatten the curve to alleviate the burden on hospitals and decrease patient mortality. However, in surge situations when hospitals have already been pushed to their limits, we need to find ways to circumvent these shortages. This was particularly true at our academic medical center during the surge period of December 2020 through January 2021, necessitating the need for an innovative approach to improve patient outcomes and reduce the strain on resources. Utilizing the ED and implementing early treatment strategies with mAbs, especially during a surge crisis, can decrease severity of illness, hospitalizations, and deaths, as demonstrated in our article.

This study had several limitations. First, it is plausible that some ED patients may have gone to a different hospital after discharge from the UCI ED rather than returning to our institution. Given the constraints of using the EMR, we were only able to assess hospitalizations and subsequent ED visits at UCI. Second, there were 2 confounding variables identified when analyzing the demographic differences between the control and treatment group among those who met EUA criteria. The median age among those in the treatment group was greater than those in the control group (P = .03), and the proportion of individuals with CKD/ESRD was also greater in those in the treatment group (P = .02). It is well known that older patients and those with renal disease have higher incidences of morbidity and mortality. Achieving statistically significant differences overall between control and treatment groups despite greater numbers of older individuals and patients with renal disease in the treatment group supports our strategy and the usage of mAb.19,20

Finally, as of April 16, 2021, the FDA revoked EUA for bamlanivimab when administered alone. However, alternative mAb therapies remain available under the EUA, including REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab), sotrovimab, and the combination therapy of bamlanivimab and etesevimab.21 This decision was made in light of the increased frequency of resistant variants of SARS-CoV-2 with bamlanivimab treatment alone.21 Our study was conducted prior to this announcement. However, as treatment with other mAbs is still permissible, we believe our findings can translate to treatment with mAbs in general. In fact, combination therapy with bamlanivimab and etesevimab has been found to be more effective than monotherapy alone, suggesting that our results may be even more robust with combination mAb therapy.11 Overall, while additional studies are needed with larger sample sizes and combination mAb treatment to fully elucidate the impact of administering mAb treatment in the ED, our results suggest that targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, or deaths.

Conclusion

Targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 illness and substantially reduce the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially for individuals of underserved populations who may not have access to ambulatory care.

Corresponding author: Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, Department of Medicine and Hospital Medicine Program, University of California, Irvine, 333 City Tower West, Ste 500, Orange, CA 92868; anamin@uci.edu.

Financial disclosures: This manuscript was generously supported by multiple donors, including the Mehra Family, the Yang Family, and the Chao Family. Dr. Amin reported serving as Principal Investigator or Co-Investigator of clinical trials sponsored by NIH/NIAID, NeuroRX Pharma, Pulmotect, Blade Therapeutics, Novartis, Takeda, Humanigen, Eli Lilly, PTC Therapeutics, OctaPharma, Fulcrum Therapeutics, and Alexion, unrelated to the present study. He has served as speaker and/or consultant for BMS, Pfizer, BI, Portola, Sunovion, Mylan, Salix, Alexion, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Nabriva, Paratek, Bayer, Tetraphase, Achaogen La Jolla, Ferring, Seres, Millennium, PeraHealth, HeartRite, Aseptiscope, and Sprightly, unrelated to the present study.

1. Global map. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. Updated November 9, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

2. Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage — allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1973-1975. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2005689

3. Cavallo JJ, Donoho DA, Forman HP. Hospital capacity and operations in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic—planning for the Nth patient. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(3):e200345. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0345

4. Eriksson CO, Stoner RC, Eden KB, et al. The association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):686-696. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3

5. Bravata DM, Perkins AJ, Myers LJ, et al. Association of intensive care unit patient load and demand with mortality rates in US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034266. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34266

6. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19);1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

7. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. US Food & Drug Administration. November 9, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19

8. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):229-237. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029849

9. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):238-251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035002

10. Chen X, Li R, Pan Z, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(6):647-649. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7

11. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(7):632-644. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.0202

12. Toy S, Walker J, Evans M. Highly touted monoclonal antibody therapies sit unused in hospitals The Wall Street Journal. December 27, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/highly-touted-monoclonal-antibody-therapies-sit-unused-in-hospitals-11609087364

13. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/anti-sars-cov-2-antibody-products/anti-sars-cov-2-monoclonal-antibodies/

14. Langellier BA. Policy recommendations to address high risk of COVID-19 among immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(8):1137-1139. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305792

15. Verderese J P, Stepanova M, Lam B, et al. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody treatment reduces hospitalization for mild and moderate COVID-19: a real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab579. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab579

16. Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans with primary care and changes over time, 2002-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):463-466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6282

17. Rust G, Ye J, Daniels E, et al. Practical barriers to timely primary care access: impact on adult use of emergency department services. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1705-1710. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.15.1705

18. COVID-19 Hospitalization Tracking Project: analysis of HHS data. University of Minnesota. Carlson School of Management. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/mili-misrc-covid19-tracking-project

19. Zare˛bska-Michaluk D, Jaroszewicz J, Rogalska M, et al. Impact of kidney failure on the severity of COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):2042. doi:10.3390/jcm10092042

20. Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID‐19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926-929. doi:10.1111/jgs.16472

21. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA revokes emergency use authorization for monoclonal antibody bamlanivimab. US Food & Drug Administration. April 16, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-monoclonal-antibody-bamlanivimab

From the Center for Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA (Drs. Chow and Chang, Mazaya Soundara), University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, CA (Ruchi Desai), Division of Infectious Diseases, University of California, Irvine, CA (Dr. Gohil), and the Department of Medicine and Hospital Medicine Program, University of California, Irvine, CA (Dr. Amin).

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has placed substantial strain on hospital resources and has been responsible for more than 733 000 deaths in the United States. The US Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy in the US for patients with early-stage high-risk COVID-19.

Methods: In this retrospective cohort study, we studied the emergency department (ED) during a massive COVID-19 surge in Orange County, California, from December 4, 2020, to January 29, 2021, as a potential setting for efficient mAb delivery by evaluating the impact of bamlanivimab use in high-risk COVID-19 patients. All patients included in this study had positive results on nucleic acid amplification detection from nasopharyngeal or throat swabs, presented with 1 or more mild or moderate symptom, and met EUA criteria for mAb treatment. The primary outcome analyzed among this cohort of ED patients was overall improvement, which included subsequent ED/hospital visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death related to COVID-19.

Results: We identified 1278 ED patients with COVID-19 not treated with bamlanivimab and 73 patients with COVID-19 treated with bamlanivimab during the treatment period. Of these patients, 239 control patients and 63 treatment patients met EUA criteria. Overall, 7.9% (5/63) of patients receiving bamlanivimab had a subsequent ED/hospital visit, hospitalization, or death compared with 19.2% (46/239) in the control group (P = .03).

Conclusion: Targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 illness and substantially reduce the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially for individuals of underserved populations who may not have access to ambulatory care.

Keywords: COVID-19; mAb; bamlanivimab; surge management.

Since December 2019, the novel pathogen SARS-CoV-2 has spread rapidly, culminating in a pandemic that has caused more than 4.9 million deaths worldwide and claimed more than 733 000 lives in the United States.1 The scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has placed an immense strain on hospital resources, including personal protective equipment (PPE), beds, ventilators and personnel.2,3 A previous analysis demonstrated that hospital capacity strain is associated with increased mortality and worsened health outcomes.4 A more recent analysis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic found that strains on critical care capacity were associated with increased COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) mortality.5 While more studies are needed to understand the association between hospital resources and COVID-19 mortality, efforts to decrease COVID-19 hospitalizations by early targeted treatment of patients in outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings may help to relieve the burden on hospital personnel and resources and decrease subsequent mortality.

Current therapeutic options focus on inpatient management of patients who progress to acute respiratory illness while patients with mild presentations are managed with outpatient monitoring, even those at high risk for progression. At the moment, only remdesivir, a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.6 However, in November 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), monotherapy, and combination therapy in a broad range of early-stage, high-risk patients.7-9 Neutralizing mAbs include bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555), etesevimab (LY-CoV016), sotrovimab (VIR-7831), and casirivimab/imdevimab (REGN-COV2). These anti–spike protein antibodies prevent viral attachment to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (hACE2) and subsequently prevent viral entry.10 mAb therapy has been shown to be effective in substantially reducing viral load, hospitalizations, and ED visits.11

Despite these promising results, uptake of mAb therapy has been slow, with more than 600 000 available doses remaining unused as of mid-January 2021, despite very high infection rates across the United States.12 In addition to the logistical challenges associated with intravenous (IV) therapy in the ambulatory setting, identifying, notifying, and scheduling appointments for ambulatory patients hamper efficient delivery to high-risk patients and limit access to underserved patients without primary care providers. For patients not treated in the ambulatory setting, the ED may serve as an ideal location for early implementation of mAb treatment in high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

The University of California, Irvine (UCI) Medical Center is not only the major premium academic medical center in Orange County, California, but also the primary safety net hospital for vulnerable populations in Orange County. During the surge period from December 2020 through January 2021, we were over 100% capacity and had built an onsite mobile hospital to expand the number of beds available. Given the severity of the impact of COVID-19 on our resources, implementing a strategy to reduce hospital admissions, patient death, and subsequent ED visits was imperative. Our goal was to implement a strategy on the front end through the ED to optimize care for patients and reduce the strain on hospital resources.

We sought to study the ED during this massive surge as a potential setting for efficient mAb delivery by evaluating the impact of bamlanivimab use in high risk COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study (approved by UCI institutional review board) of sequential COVID-19 adult patients who were evaluated and discharged from the ED between December 4, 2020, and January 29, 2021, and received bamlanivimab treatment (cases) compared with a nontreatment group (control) of ED patients.

Using the UCI electronic medical record (EMR) system, we identified 1278 ED patients with COVID-19 not treated with bamlanivimab and 73 patients with COVID-19 treated with bamlanivimab during the months of December 2020 and January 2021. All patients included in this study met the EUA criteria for mAb therapy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), during the period of this study, patients met EUA criteria if they had mild to moderate COVID-19, a positive direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and a high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 or hospitalization.13 High risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 and/or hospitalization is defined as meeting at least 1 of the following criteria: a body mass index of 35 or higher, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes, immunosuppressive disease, currently receiving immunosuppressive treatment, aged 65 years or older, aged 55 years or older and have cardiovascular disease or hypertension, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/other chronic respiratory diseases.13 All patients in the ED who met EUA criteria were offered mAb treatment; those who accepted the treatment were included in the treatment group, and those who refused were included in the control group.

All patients included in this study had positive results on nucleic acid amplification detection from nasopharyngeal or throat swabs and presented with 1 or more mild or moderate symptom, defined as: fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, or shortness of breath. We excluded patients admitted to the hospital on that ED visit and those discharged to hospice. In addition, we excluded patients who presented 2 weeks after symptom onset and those who did not meet EUA criteria. Demographic data (age and gender) and comorbid conditions were obtained by EMR review. Comorbid conditions obtained included diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease, CKD/end-stage renal disease (ESRD), COPD, obesity, and immunocompromised status.

Bamlanivimab infusion therapy in the ED followed CDC guidelines. Each patient received 700 mg of bamlanivimab diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride and administered as a single IV infusion. We established protocols to give patients IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions directly in the ED.

The primary outcome analyzed among this cohort of ED patients was overall improvement, which included subsequent ED/hospital visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death related to COVID-19 within 90 days of initial ED visit. Each patient was only counted once. Data analysis and statistical tests were conducted using SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc). Treatment effects were compared using χ2 test with an α level of 0.05. A t test was used for continuous variables, including age. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

We screened a total of 1351 patients with COVID-19. Of these, 1278 patients did not receive treatment with bamlanivimab. Two hundred thirty-nine patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the control group. Seventy-three patients were treated with bamlanivimab in the ED; 63 of these patients met EUA criteria and comprised the treatment group (Figure 1).

Demographic details of the trial groups are provided in Table 1. The median age of the treatment group was 61 years (interquartile range [IQR], 55-73), while the median age of the control group was 57 years (IQR, 48-68). The difference in median age between the treatment and control individuals was significantly different (P = .03). There was no significant difference found in terms of gender between the control and treatment groups (P = .07). In addition, no significant difference was seen among racial and ethnic groups in the control and treatment groups. Comorbidities and demographics of all patients in the treatment and control groups are provided in Table 1. The only comorbidity that was found to be significantly different between the treatment and control groups was CKD/ESRD. Among those treated with bamlanivimab, 20.6% (13/63) had CKD/ESRD compared with 10.5% (25/239) in the control group (P = .02).

Overall, 7.9% (5/63) of patients receiving bamlanivimab had a subsequent ED/hospital visit, hospitalization, or death compared with 19.2% (46/239) in the control group (P = .03) (Table 2).

While the primary outcome of overall improvement was significantly different between the 2 groups, comparison of the individual components, including subsequent ED visits, hospitalizations, or death, were not significant. No treatment patients were hospitalized, compared with 5.4% (13/239) in the control group (P = .05). In the treatment group, 6.3% (4/63) returned to the ED compared with 12.6% (30/239) of the control group (P = .17). Finally, 1.6% (1/63) of the treatment group had a subsequent death that was due to COVID-19 compared with 1.3% (3/239) in the control group (P = .84) (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, we observed a significant difference in rates of COVID-19 patients requiring repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths among those who received bamlanivimab compared with those who did not. Our study focused on high-risk patients with mild or moderate COVID-19, a unique subset of individuals who would normally be followed and treated via outpatient monitoring. We propose that treating high-risk patients earlier in their disease process with mAb therapy can have a major impact on overall outcomes, as defined by decreased subsequent hospitalizations, ED visits, and death.

Compared to clinical trials such as BLAZE-1 or REGN-COV2, every patient in this trial had at least 1 high-risk characteristic.9,11 This may explain why a greater proportion of our patients in both the control and treatment groups had subsequent hospitalization, ED visits, and deaths. COVID-19 patients seen in the ED may be a uniquely self-selected population of individuals likely to benefit from mAb therapy since they may be more likely to be sicker, have more comorbidities, or have less readily available primary care access for testing and treatment.14

Despite conducting a thorough literature review, we were unable to find any similar studies describing the ED as an appropriate setting for mAb treatment in patients with COVID-19. Multiple studies have used outpatient clinics as a setting for mAb treatment, and 1 retrospective analysis found that neutralizing mAb treatment in COVID-19 patients in an outpatient setting reduced hospital utilization.15 However, many Americans do not have access to primary care, with 1 study finding that only 75% of Americans had an identified source of primary care in 2015.16 Obstacles to primary care access include disabilities, lack of health insurance, language-related barriers, race/ethnicity, and homelessness.17 Barriers to access for primary care services and timely care make these populations more likely to frequent the ED.17 This makes the ED a unique location for early and targeted treatment of COVID-19 patients with a high risk for progression to severe COVID-19.

During surge periods in the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals met capacity or superseded their capacity for patients, with 4423 hospitals reporting more than 90% of hospital beds occupied and 2591 reporting more than 90% of ICU beds occupied during the peak surge week of January 1, 2021, to January 7, 2021.18 The main goals of lockdowns and masking have been to decrease the transmission of COVID-19 and hopefully flatten the curve to alleviate the burden on hospitals and decrease patient mortality. However, in surge situations when hospitals have already been pushed to their limits, we need to find ways to circumvent these shortages. This was particularly true at our academic medical center during the surge period of December 2020 through January 2021, necessitating the need for an innovative approach to improve patient outcomes and reduce the strain on resources. Utilizing the ED and implementing early treatment strategies with mAbs, especially during a surge crisis, can decrease severity of illness, hospitalizations, and deaths, as demonstrated in our article.

This study had several limitations. First, it is plausible that some ED patients may have gone to a different hospital after discharge from the UCI ED rather than returning to our institution. Given the constraints of using the EMR, we were only able to assess hospitalizations and subsequent ED visits at UCI. Second, there were 2 confounding variables identified when analyzing the demographic differences between the control and treatment group among those who met EUA criteria. The median age among those in the treatment group was greater than those in the control group (P = .03), and the proportion of individuals with CKD/ESRD was also greater in those in the treatment group (P = .02). It is well known that older patients and those with renal disease have higher incidences of morbidity and mortality. Achieving statistically significant differences overall between control and treatment groups despite greater numbers of older individuals and patients with renal disease in the treatment group supports our strategy and the usage of mAb.19,20

Finally, as of April 16, 2021, the FDA revoked EUA for bamlanivimab when administered alone. However, alternative mAb therapies remain available under the EUA, including REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab), sotrovimab, and the combination therapy of bamlanivimab and etesevimab.21 This decision was made in light of the increased frequency of resistant variants of SARS-CoV-2 with bamlanivimab treatment alone.21 Our study was conducted prior to this announcement. However, as treatment with other mAbs is still permissible, we believe our findings can translate to treatment with mAbs in general. In fact, combination therapy with bamlanivimab and etesevimab has been found to be more effective than monotherapy alone, suggesting that our results may be even more robust with combination mAb therapy.11 Overall, while additional studies are needed with larger sample sizes and combination mAb treatment to fully elucidate the impact of administering mAb treatment in the ED, our results suggest that targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, or deaths.

Conclusion

Targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 illness and substantially reduce the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially for individuals of underserved populations who may not have access to ambulatory care.

Corresponding author: Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, Department of Medicine and Hospital Medicine Program, University of California, Irvine, 333 City Tower West, Ste 500, Orange, CA 92868; anamin@uci.edu.

Financial disclosures: This manuscript was generously supported by multiple donors, including the Mehra Family, the Yang Family, and the Chao Family. Dr. Amin reported serving as Principal Investigator or Co-Investigator of clinical trials sponsored by NIH/NIAID, NeuroRX Pharma, Pulmotect, Blade Therapeutics, Novartis, Takeda, Humanigen, Eli Lilly, PTC Therapeutics, OctaPharma, Fulcrum Therapeutics, and Alexion, unrelated to the present study. He has served as speaker and/or consultant for BMS, Pfizer, BI, Portola, Sunovion, Mylan, Salix, Alexion, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Nabriva, Paratek, Bayer, Tetraphase, Achaogen La Jolla, Ferring, Seres, Millennium, PeraHealth, HeartRite, Aseptiscope, and Sprightly, unrelated to the present study.

From the Center for Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA (Drs. Chow and Chang, Mazaya Soundara), University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, CA (Ruchi Desai), Division of Infectious Diseases, University of California, Irvine, CA (Dr. Gohil), and the Department of Medicine and Hospital Medicine Program, University of California, Irvine, CA (Dr. Amin).

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has placed substantial strain on hospital resources and has been responsible for more than 733 000 deaths in the United States. The US Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy in the US for patients with early-stage high-risk COVID-19.

Methods: In this retrospective cohort study, we studied the emergency department (ED) during a massive COVID-19 surge in Orange County, California, from December 4, 2020, to January 29, 2021, as a potential setting for efficient mAb delivery by evaluating the impact of bamlanivimab use in high-risk COVID-19 patients. All patients included in this study had positive results on nucleic acid amplification detection from nasopharyngeal or throat swabs, presented with 1 or more mild or moderate symptom, and met EUA criteria for mAb treatment. The primary outcome analyzed among this cohort of ED patients was overall improvement, which included subsequent ED/hospital visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death related to COVID-19.

Results: We identified 1278 ED patients with COVID-19 not treated with bamlanivimab and 73 patients with COVID-19 treated with bamlanivimab during the treatment period. Of these patients, 239 control patients and 63 treatment patients met EUA criteria. Overall, 7.9% (5/63) of patients receiving bamlanivimab had a subsequent ED/hospital visit, hospitalization, or death compared with 19.2% (46/239) in the control group (P = .03).

Conclusion: Targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 illness and substantially reduce the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially for individuals of underserved populations who may not have access to ambulatory care.

Keywords: COVID-19; mAb; bamlanivimab; surge management.

Since December 2019, the novel pathogen SARS-CoV-2 has spread rapidly, culminating in a pandemic that has caused more than 4.9 million deaths worldwide and claimed more than 733 000 lives in the United States.1 The scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has placed an immense strain on hospital resources, including personal protective equipment (PPE), beds, ventilators and personnel.2,3 A previous analysis demonstrated that hospital capacity strain is associated with increased mortality and worsened health outcomes.4 A more recent analysis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic found that strains on critical care capacity were associated with increased COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) mortality.5 While more studies are needed to understand the association between hospital resources and COVID-19 mortality, efforts to decrease COVID-19 hospitalizations by early targeted treatment of patients in outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings may help to relieve the burden on hospital personnel and resources and decrease subsequent mortality.

Current therapeutic options focus on inpatient management of patients who progress to acute respiratory illness while patients with mild presentations are managed with outpatient monitoring, even those at high risk for progression. At the moment, only remdesivir, a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.6 However, in November 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), monotherapy, and combination therapy in a broad range of early-stage, high-risk patients.7-9 Neutralizing mAbs include bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555), etesevimab (LY-CoV016), sotrovimab (VIR-7831), and casirivimab/imdevimab (REGN-COV2). These anti–spike protein antibodies prevent viral attachment to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (hACE2) and subsequently prevent viral entry.10 mAb therapy has been shown to be effective in substantially reducing viral load, hospitalizations, and ED visits.11

Despite these promising results, uptake of mAb therapy has been slow, with more than 600 000 available doses remaining unused as of mid-January 2021, despite very high infection rates across the United States.12 In addition to the logistical challenges associated with intravenous (IV) therapy in the ambulatory setting, identifying, notifying, and scheduling appointments for ambulatory patients hamper efficient delivery to high-risk patients and limit access to underserved patients without primary care providers. For patients not treated in the ambulatory setting, the ED may serve as an ideal location for early implementation of mAb treatment in high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

The University of California, Irvine (UCI) Medical Center is not only the major premium academic medical center in Orange County, California, but also the primary safety net hospital for vulnerable populations in Orange County. During the surge period from December 2020 through January 2021, we were over 100% capacity and had built an onsite mobile hospital to expand the number of beds available. Given the severity of the impact of COVID-19 on our resources, implementing a strategy to reduce hospital admissions, patient death, and subsequent ED visits was imperative. Our goal was to implement a strategy on the front end through the ED to optimize care for patients and reduce the strain on hospital resources.

We sought to study the ED during this massive surge as a potential setting for efficient mAb delivery by evaluating the impact of bamlanivimab use in high risk COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study (approved by UCI institutional review board) of sequential COVID-19 adult patients who were evaluated and discharged from the ED between December 4, 2020, and January 29, 2021, and received bamlanivimab treatment (cases) compared with a nontreatment group (control) of ED patients.

Using the UCI electronic medical record (EMR) system, we identified 1278 ED patients with COVID-19 not treated with bamlanivimab and 73 patients with COVID-19 treated with bamlanivimab during the months of December 2020 and January 2021. All patients included in this study met the EUA criteria for mAb therapy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), during the period of this study, patients met EUA criteria if they had mild to moderate COVID-19, a positive direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and a high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 or hospitalization.13 High risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 and/or hospitalization is defined as meeting at least 1 of the following criteria: a body mass index of 35 or higher, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes, immunosuppressive disease, currently receiving immunosuppressive treatment, aged 65 years or older, aged 55 years or older and have cardiovascular disease or hypertension, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/other chronic respiratory diseases.13 All patients in the ED who met EUA criteria were offered mAb treatment; those who accepted the treatment were included in the treatment group, and those who refused were included in the control group.

All patients included in this study had positive results on nucleic acid amplification detection from nasopharyngeal or throat swabs and presented with 1 or more mild or moderate symptom, defined as: fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, or shortness of breath. We excluded patients admitted to the hospital on that ED visit and those discharged to hospice. In addition, we excluded patients who presented 2 weeks after symptom onset and those who did not meet EUA criteria. Demographic data (age and gender) and comorbid conditions were obtained by EMR review. Comorbid conditions obtained included diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease, CKD/end-stage renal disease (ESRD), COPD, obesity, and immunocompromised status.

Bamlanivimab infusion therapy in the ED followed CDC guidelines. Each patient received 700 mg of bamlanivimab diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride and administered as a single IV infusion. We established protocols to give patients IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions directly in the ED.

The primary outcome analyzed among this cohort of ED patients was overall improvement, which included subsequent ED/hospital visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death related to COVID-19 within 90 days of initial ED visit. Each patient was only counted once. Data analysis and statistical tests were conducted using SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc). Treatment effects were compared using χ2 test with an α level of 0.05. A t test was used for continuous variables, including age. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

We screened a total of 1351 patients with COVID-19. Of these, 1278 patients did not receive treatment with bamlanivimab. Two hundred thirty-nine patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the control group. Seventy-three patients were treated with bamlanivimab in the ED; 63 of these patients met EUA criteria and comprised the treatment group (Figure 1).

Demographic details of the trial groups are provided in Table 1. The median age of the treatment group was 61 years (interquartile range [IQR], 55-73), while the median age of the control group was 57 years (IQR, 48-68). The difference in median age between the treatment and control individuals was significantly different (P = .03). There was no significant difference found in terms of gender between the control and treatment groups (P = .07). In addition, no significant difference was seen among racial and ethnic groups in the control and treatment groups. Comorbidities and demographics of all patients in the treatment and control groups are provided in Table 1. The only comorbidity that was found to be significantly different between the treatment and control groups was CKD/ESRD. Among those treated with bamlanivimab, 20.6% (13/63) had CKD/ESRD compared with 10.5% (25/239) in the control group (P = .02).

Overall, 7.9% (5/63) of patients receiving bamlanivimab had a subsequent ED/hospital visit, hospitalization, or death compared with 19.2% (46/239) in the control group (P = .03) (Table 2).

While the primary outcome of overall improvement was significantly different between the 2 groups, comparison of the individual components, including subsequent ED visits, hospitalizations, or death, were not significant. No treatment patients were hospitalized, compared with 5.4% (13/239) in the control group (P = .05). In the treatment group, 6.3% (4/63) returned to the ED compared with 12.6% (30/239) of the control group (P = .17). Finally, 1.6% (1/63) of the treatment group had a subsequent death that was due to COVID-19 compared with 1.3% (3/239) in the control group (P = .84) (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, we observed a significant difference in rates of COVID-19 patients requiring repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths among those who received bamlanivimab compared with those who did not. Our study focused on high-risk patients with mild or moderate COVID-19, a unique subset of individuals who would normally be followed and treated via outpatient monitoring. We propose that treating high-risk patients earlier in their disease process with mAb therapy can have a major impact on overall outcomes, as defined by decreased subsequent hospitalizations, ED visits, and death.

Compared to clinical trials such as BLAZE-1 or REGN-COV2, every patient in this trial had at least 1 high-risk characteristic.9,11 This may explain why a greater proportion of our patients in both the control and treatment groups had subsequent hospitalization, ED visits, and deaths. COVID-19 patients seen in the ED may be a uniquely self-selected population of individuals likely to benefit from mAb therapy since they may be more likely to be sicker, have more comorbidities, or have less readily available primary care access for testing and treatment.14

Despite conducting a thorough literature review, we were unable to find any similar studies describing the ED as an appropriate setting for mAb treatment in patients with COVID-19. Multiple studies have used outpatient clinics as a setting for mAb treatment, and 1 retrospective analysis found that neutralizing mAb treatment in COVID-19 patients in an outpatient setting reduced hospital utilization.15 However, many Americans do not have access to primary care, with 1 study finding that only 75% of Americans had an identified source of primary care in 2015.16 Obstacles to primary care access include disabilities, lack of health insurance, language-related barriers, race/ethnicity, and homelessness.17 Barriers to access for primary care services and timely care make these populations more likely to frequent the ED.17 This makes the ED a unique location for early and targeted treatment of COVID-19 patients with a high risk for progression to severe COVID-19.

During surge periods in the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals met capacity or superseded their capacity for patients, with 4423 hospitals reporting more than 90% of hospital beds occupied and 2591 reporting more than 90% of ICU beds occupied during the peak surge week of January 1, 2021, to January 7, 2021.18 The main goals of lockdowns and masking have been to decrease the transmission of COVID-19 and hopefully flatten the curve to alleviate the burden on hospitals and decrease patient mortality. However, in surge situations when hospitals have already been pushed to their limits, we need to find ways to circumvent these shortages. This was particularly true at our academic medical center during the surge period of December 2020 through January 2021, necessitating the need for an innovative approach to improve patient outcomes and reduce the strain on resources. Utilizing the ED and implementing early treatment strategies with mAbs, especially during a surge crisis, can decrease severity of illness, hospitalizations, and deaths, as demonstrated in our article.

This study had several limitations. First, it is plausible that some ED patients may have gone to a different hospital after discharge from the UCI ED rather than returning to our institution. Given the constraints of using the EMR, we were only able to assess hospitalizations and subsequent ED visits at UCI. Second, there were 2 confounding variables identified when analyzing the demographic differences between the control and treatment group among those who met EUA criteria. The median age among those in the treatment group was greater than those in the control group (P = .03), and the proportion of individuals with CKD/ESRD was also greater in those in the treatment group (P = .02). It is well known that older patients and those with renal disease have higher incidences of morbidity and mortality. Achieving statistically significant differences overall between control and treatment groups despite greater numbers of older individuals and patients with renal disease in the treatment group supports our strategy and the usage of mAb.19,20

Finally, as of April 16, 2021, the FDA revoked EUA for bamlanivimab when administered alone. However, alternative mAb therapies remain available under the EUA, including REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab), sotrovimab, and the combination therapy of bamlanivimab and etesevimab.21 This decision was made in light of the increased frequency of resistant variants of SARS-CoV-2 with bamlanivimab treatment alone.21 Our study was conducted prior to this announcement. However, as treatment with other mAbs is still permissible, we believe our findings can translate to treatment with mAbs in general. In fact, combination therapy with bamlanivimab and etesevimab has been found to be more effective than monotherapy alone, suggesting that our results may be even more robust with combination mAb therapy.11 Overall, while additional studies are needed with larger sample sizes and combination mAb treatment to fully elucidate the impact of administering mAb treatment in the ED, our results suggest that targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, or deaths.

Conclusion

Targeting ED patients for mAb treatment may be an effective strategy to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 illness and substantially reduce the composite end point of repeat ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially for individuals of underserved populations who may not have access to ambulatory care.

Corresponding author: Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, Department of Medicine and Hospital Medicine Program, University of California, Irvine, 333 City Tower West, Ste 500, Orange, CA 92868; anamin@uci.edu.

Financial disclosures: This manuscript was generously supported by multiple donors, including the Mehra Family, the Yang Family, and the Chao Family. Dr. Amin reported serving as Principal Investigator or Co-Investigator of clinical trials sponsored by NIH/NIAID, NeuroRX Pharma, Pulmotect, Blade Therapeutics, Novartis, Takeda, Humanigen, Eli Lilly, PTC Therapeutics, OctaPharma, Fulcrum Therapeutics, and Alexion, unrelated to the present study. He has served as speaker and/or consultant for BMS, Pfizer, BI, Portola, Sunovion, Mylan, Salix, Alexion, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Nabriva, Paratek, Bayer, Tetraphase, Achaogen La Jolla, Ferring, Seres, Millennium, PeraHealth, HeartRite, Aseptiscope, and Sprightly, unrelated to the present study.

1. Global map. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. Updated November 9, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

2. Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage — allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1973-1975. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2005689

3. Cavallo JJ, Donoho DA, Forman HP. Hospital capacity and operations in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic—planning for the Nth patient. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(3):e200345. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0345

4. Eriksson CO, Stoner RC, Eden KB, et al. The association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):686-696. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3

5. Bravata DM, Perkins AJ, Myers LJ, et al. Association of intensive care unit patient load and demand with mortality rates in US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034266. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34266

6. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19);1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

7. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. US Food & Drug Administration. November 9, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19

8. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):229-237. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029849

9. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):238-251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035002

10. Chen X, Li R, Pan Z, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(6):647-649. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7

11. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(7):632-644. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.0202

12. Toy S, Walker J, Evans M. Highly touted monoclonal antibody therapies sit unused in hospitals The Wall Street Journal. December 27, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/highly-touted-monoclonal-antibody-therapies-sit-unused-in-hospitals-11609087364

13. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/anti-sars-cov-2-antibody-products/anti-sars-cov-2-monoclonal-antibodies/

14. Langellier BA. Policy recommendations to address high risk of COVID-19 among immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(8):1137-1139. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305792

15. Verderese J P, Stepanova M, Lam B, et al. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody treatment reduces hospitalization for mild and moderate COVID-19: a real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab579. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab579

16. Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans with primary care and changes over time, 2002-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):463-466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6282

17. Rust G, Ye J, Daniels E, et al. Practical barriers to timely primary care access: impact on adult use of emergency department services. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1705-1710. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.15.1705

18. COVID-19 Hospitalization Tracking Project: analysis of HHS data. University of Minnesota. Carlson School of Management. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/mili-misrc-covid19-tracking-project

19. Zare˛bska-Michaluk D, Jaroszewicz J, Rogalska M, et al. Impact of kidney failure on the severity of COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):2042. doi:10.3390/jcm10092042

20. Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID‐19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926-929. doi:10.1111/jgs.16472

21. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA revokes emergency use authorization for monoclonal antibody bamlanivimab. US Food & Drug Administration. April 16, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-monoclonal-antibody-bamlanivimab

1. Global map. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. Updated November 9, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

2. Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage — allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1973-1975. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2005689

3. Cavallo JJ, Donoho DA, Forman HP. Hospital capacity and operations in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic—planning for the Nth patient. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(3):e200345. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0345

4. Eriksson CO, Stoner RC, Eden KB, et al. The association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):686-696. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3

5. Bravata DM, Perkins AJ, Myers LJ, et al. Association of intensive care unit patient load and demand with mortality rates in US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034266. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34266

6. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19);1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

7. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. US Food & Drug Administration. November 9, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19

8. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):229-237. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029849

9. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):238-251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035002

10. Chen X, Li R, Pan Z, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(6):647-649. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7

11. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(7):632-644. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.0202

12. Toy S, Walker J, Evans M. Highly touted monoclonal antibody therapies sit unused in hospitals The Wall Street Journal. December 27, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/highly-touted-monoclonal-antibody-therapies-sit-unused-in-hospitals-11609087364

13. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/anti-sars-cov-2-antibody-products/anti-sars-cov-2-monoclonal-antibodies/

14. Langellier BA. Policy recommendations to address high risk of COVID-19 among immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(8):1137-1139. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305792

15. Verderese J P, Stepanova M, Lam B, et al. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody treatment reduces hospitalization for mild and moderate COVID-19: a real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab579. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab579

16. Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans with primary care and changes over time, 2002-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):463-466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6282

17. Rust G, Ye J, Daniels E, et al. Practical barriers to timely primary care access: impact on adult use of emergency department services. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1705-1710. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.15.1705

18. COVID-19 Hospitalization Tracking Project: analysis of HHS data. University of Minnesota. Carlson School of Management. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/mili-misrc-covid19-tracking-project

19. Zare˛bska-Michaluk D, Jaroszewicz J, Rogalska M, et al. Impact of kidney failure on the severity of COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):2042. doi:10.3390/jcm10092042

20. Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID‐19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926-929. doi:10.1111/jgs.16472

21. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA revokes emergency use authorization for monoclonal antibody bamlanivimab. US Food & Drug Administration. April 16, 2021. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-monoclonal-antibody-bamlanivimab

Antibiotics vs. placebo in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis

Background: Antibiotic therapy is considered the standard of care for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Over the past decade, randomized clinical trials have suggested that treatment with antibiotics may be noninferior to observation with supportive care; however, there have not been any blinded, placebo-controlled trials to provide high-quality evidence.

Study design: Placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Four centers in New Zealand and Australia.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 180 patients hospitalized for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis with Hinchey 1a CT findings (i.e., phlegmon without abscess) into two groups treated with either antibiotics (intravenous cefuroxime and oral metronidazole followed by oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) or placebo for 7 days. Median lengths of stay between the antibiotic (40.0 hours) and placebo (45.8 hours) groups were not significantly different (5.9 hours difference between groups; 95% CI, –3.7 to 15.5; P = .2). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the secondary outcomes of readmission at 7 days and 30 days or in need for procedural intervention, mortality, pain scores at 24 hours, or change in white blood cell count.

Notably, though this study was adequately powered to detect differences in length of stay, it was not powered to detect differences in clinical outcomes, including death or the need for surgery. The exclusion of patients with language barriers raises concerns regarding the generalizability of the results.

Bottom line: Antibiotic therapy does not decrease length of hospital stay when compared with placebo for patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis.

Citation: Jaung R et al. Antibiotics do not reduce length of hospital stay for uncomplicated diverticulitis in a pragmatic double-blind randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar;S1542-3565(20):30426-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.049.

Dr. Elyahu is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Background: Antibiotic therapy is considered the standard of care for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Over the past decade, randomized clinical trials have suggested that treatment with antibiotics may be noninferior to observation with supportive care; however, there have not been any blinded, placebo-controlled trials to provide high-quality evidence.

Study design: Placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Four centers in New Zealand and Australia.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 180 patients hospitalized for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis with Hinchey 1a CT findings (i.e., phlegmon without abscess) into two groups treated with either antibiotics (intravenous cefuroxime and oral metronidazole followed by oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) or placebo for 7 days. Median lengths of stay between the antibiotic (40.0 hours) and placebo (45.8 hours) groups were not significantly different (5.9 hours difference between groups; 95% CI, –3.7 to 15.5; P = .2). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the secondary outcomes of readmission at 7 days and 30 days or in need for procedural intervention, mortality, pain scores at 24 hours, or change in white blood cell count.

Notably, though this study was adequately powered to detect differences in length of stay, it was not powered to detect differences in clinical outcomes, including death or the need for surgery. The exclusion of patients with language barriers raises concerns regarding the generalizability of the results.

Bottom line: Antibiotic therapy does not decrease length of hospital stay when compared with placebo for patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis.

Citation: Jaung R et al. Antibiotics do not reduce length of hospital stay for uncomplicated diverticulitis in a pragmatic double-blind randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar;S1542-3565(20):30426-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.049.

Dr. Elyahu is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Background: Antibiotic therapy is considered the standard of care for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Over the past decade, randomized clinical trials have suggested that treatment with antibiotics may be noninferior to observation with supportive care; however, there have not been any blinded, placebo-controlled trials to provide high-quality evidence.

Study design: Placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Four centers in New Zealand and Australia.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 180 patients hospitalized for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis with Hinchey 1a CT findings (i.e., phlegmon without abscess) into two groups treated with either antibiotics (intravenous cefuroxime and oral metronidazole followed by oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) or placebo for 7 days. Median lengths of stay between the antibiotic (40.0 hours) and placebo (45.8 hours) groups were not significantly different (5.9 hours difference between groups; 95% CI, –3.7 to 15.5; P = .2). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the secondary outcomes of readmission at 7 days and 30 days or in need for procedural intervention, mortality, pain scores at 24 hours, or change in white blood cell count.

Notably, though this study was adequately powered to detect differences in length of stay, it was not powered to detect differences in clinical outcomes, including death or the need for surgery. The exclusion of patients with language barriers raises concerns regarding the generalizability of the results.

Bottom line: Antibiotic therapy does not decrease length of hospital stay when compared with placebo for patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis.

Citation: Jaung R et al. Antibiotics do not reduce length of hospital stay for uncomplicated diverticulitis in a pragmatic double-blind randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar;S1542-3565(20):30426-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.049.

Dr. Elyahu is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Study shows wider gaps, broader inequities in U.S. sex education than 25 years ago

American teenagers receive less formal sex education today than they did 25 years ago, with “troubling” racial inequities that leave youth of color and queer youth at greater risk than other teens for sexually transmitted diseases and unintended pregnancy, according to a new study.

“Many adolescents do not receive any instruction on essential topics or do not receive this instruction until after the first sex,” wrote Laura D. Lindberg, PhD, and Leslie M. Kantor, PhD, MPH, from the Guttmacher Institute, New York, and the department of urban-global public health at Rutgers University, Piscataway, N.J., respectively. “These gaps in sex education in the U.S. are uneven, and gender, racial, and other disparities are widespread,” they added, calling for “robust efforts ... to ensure equity and reduce health disparities.”

The study used cross-sectional data from the 2011-2015 and 2015-2019 National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG) to examine content, timing, and location of formal sex education among 15- to 19-year-olds in the United States. The data came from samples of 2,047 females and 2,087 males in 2011-2015, and 1,894 females and 1,918 males in 2015-2019. The majority of respondents were aged 15-17 years and non-Hispanic White, with another quarter being Hispanic, and 14% Black.

The survey asked respondents whether, before they turned 18, they had ever received formal instruction at school, church, a community center, “or some other place” about how to say no to sex, methods of birth control, STDs, how to prevent HIV/AIDS, abstaining until marriage to have sex, where to get birth control, and how to use a condom.

Follow-up questions asked about what grade instruction was first received and whether it had occurred before first penile-vaginal intercourse. The 2015-2019 survey also asked about the location of instruction, but only concerning methods of birth control and abstinence until marriage.

The results showed that HIV and STD prevention was the most commonly reported area of instruction, received by more than 90% of both males and females. However, beyond this there were imbalances, with only about half (49%-55%) of respondents receiving instruction meeting the Surgeon General’s Healthy People 2030 composite sex education goal. Lack of instruction on birth control drove this result for 80% of respondents. Specifically, there was a strong slant emphasizing abstinence over birth control instruction. Over both survey periods and both genders, more respondents reported instruction on how to say no to sex (79%-84%) and abstaining until marriage (58%-73%), compared with where to obtain birth control (40%-53%) or how to use a condom (54%-60%). “Overall, about 20% of adolescents received instruction from multiple sources about waiting until marriage, but only 5%-8% received birth control information from multiple settings,” they reported.

There were racial/ethnic and sexual orientation differences in the scope and balance of instruction reported by teens. Less than half of Black (45%) and Hispanic (47%) males received instruction on the combined Healthy People topics, compared with 57% of White males. Black females were less likely (30%) than White females (45%) to receive information on where to get birth control before the first sex. Nonstraight males were less likely than straight males to receive instruction about STIs or HIV/AIDS (83% vs. 93%).

In addition, religious attendance emerged as a key factor in the receipt of sex education, “with more frequent religious attendance associated with a greater likelihood of instruction about delaying sex and less likelihood of instruction about contraception,” the authors noted.

Comparing their findings to previous NSFG surveys, the researchers commented that “the share of adolescents receiving instruction about birth control was higher in 1995 than in 2015-2019 for both the genders; in 1995, 87% of females and 81% of males reported sex education about birth control methods, compared with 64% and 63% in 2015-2019, respectively.” The findings “should spur policy makers at the national, state, and local levels to ensure the broader provision of sex education and that school districts serving young people of color are the focus of additional efforts and funding.”

Asked for comment, John Santelli, MD, MPH, professor of population and family health and pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, who was not involved with the study, said the findings fit into a series of studies by Lindberg going back to 1988 showing that receipt of formal sex education before age 18 has declined over time.