User login

IQ and concussion recovery

Pediatric concussion is one of those rare phenomena in which we may be witnessing its emergence and clarification in a generation. When I was serving as the game doctor for our local high school football team in the 1970s, I and many other physicians had a very simplistic view of concussion. If the patient never lost conscious and had a reasonably intact short-term memory, we didn’t seriously entertain concussion as a diagnosis. “What’s the score and who is the president?” Were my favorite screening questions.

Obviously, we were underdiagnosing and mismanaging concussion. In part thanks to some high-profile athletes who suffered multiple concussions and eventually chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) physicians began to realize that they should be looking more closely at children who sustained a head injury. The diagnostic criteria were expanded to include any injury that even temporarily effected brain function.

With the new appreciation for the risk of multiple concussions, the focus broadened to include the question of when is it safe for the athlete to return to competition. What signs or symptoms can the patient offer us so we can be sure his or her brain is sufficiently recovered? Here we stepped off into a deep abyss of ignorance. Fortunately, it became obvious fairly quickly that imaging studies weren’t going to help us, as they were invariably normal or at least didn’t tell us anything that wasn’t obvious on a physical exam.

If the patient had a headache, complained of dizziness, or manifested amnesia, monitoring the patient was fairly straightforward. But, in the absence of symptoms and no obvious way to determine the pace of recovery of an organ we couldn’t visualize, clinicians were pulling criteria and time tables out of thin air. Guessing that the concussed brain was in some ways like a torn muscle or overstretched tendon, “brain rest” was often suggested. So no TV, no reading, and certainly none of the cerebral challenging activity of school. Fortunately, we don’t hear much about the notion of brain rest anymore and there is at least one study that suggests that patients kept home from school recover more slowly.

But . Sometimes they describe headache or dizziness but often they complain of a vague mental unwellness. “Brain fog,” a term that has emerged in the wake of the COVID pandemic, might be an apt descriptor. Management of these slow recoverers has been a challenge.

However, two recent articles in the journal Pediatrics may provide some clarity and offer guidance in their management. In a study coming from the psychology department at Georgia State University, researchers reported that they have been able to find “no evidence of clinical meaningful differences in IQ after pediatric concussion.” In their words there is “strong evidence against reduced intelligence in the first few weeks to month after pediatric concussion.”

While their findings may simply toss the IQ onto the pile of worthless measures of healing, a companion commentary by Talin Babikian, PhD, a psychologist at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA, provides a more nuanced interpretation. He writes that if we are looking for an explanation when a patient’s recovery is taking longer than we might expect we need to look beyond some structural damage. Maybe the patient has a previously undiagnosed premorbid condition effecting his or her intellectual, cognitive, or learning abilities. Could the stall in improvement be the result of other symptoms? Here fatigue and sleep deprivation may be the culprits. Could some underlying emotional factor such as anxiety or depression be the problem? For example, I have seen patients whose fear of re-injury has prevented their return to full function. And, finally, the patient may be avoiding a “nonpreferred or challenging situation” unrelated to the injury.

In other words, the concussion may simply be the most obvious rip in a fabric that was already frayed and under stress. This kind of broad holistic (a word I usually like to avoid) thinking may be what is lacking as we struggle to understand other mysterious and chronic conditions such as Lyme disease and chronic fatigue syndrome.

While these two papers help provide some clarity in the management of pediatric concussion, what they fail to address is the bigger question of the relationship between head injury and CTE. The answers to that conundrum are enshrouded in a mix of politics and publicity that I doubt will clear in the near future.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Pediatric concussion is one of those rare phenomena in which we may be witnessing its emergence and clarification in a generation. When I was serving as the game doctor for our local high school football team in the 1970s, I and many other physicians had a very simplistic view of concussion. If the patient never lost conscious and had a reasonably intact short-term memory, we didn’t seriously entertain concussion as a diagnosis. “What’s the score and who is the president?” Were my favorite screening questions.

Obviously, we were underdiagnosing and mismanaging concussion. In part thanks to some high-profile athletes who suffered multiple concussions and eventually chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) physicians began to realize that they should be looking more closely at children who sustained a head injury. The diagnostic criteria were expanded to include any injury that even temporarily effected brain function.

With the new appreciation for the risk of multiple concussions, the focus broadened to include the question of when is it safe for the athlete to return to competition. What signs or symptoms can the patient offer us so we can be sure his or her brain is sufficiently recovered? Here we stepped off into a deep abyss of ignorance. Fortunately, it became obvious fairly quickly that imaging studies weren’t going to help us, as they were invariably normal or at least didn’t tell us anything that wasn’t obvious on a physical exam.

If the patient had a headache, complained of dizziness, or manifested amnesia, monitoring the patient was fairly straightforward. But, in the absence of symptoms and no obvious way to determine the pace of recovery of an organ we couldn’t visualize, clinicians were pulling criteria and time tables out of thin air. Guessing that the concussed brain was in some ways like a torn muscle or overstretched tendon, “brain rest” was often suggested. So no TV, no reading, and certainly none of the cerebral challenging activity of school. Fortunately, we don’t hear much about the notion of brain rest anymore and there is at least one study that suggests that patients kept home from school recover more slowly.

But . Sometimes they describe headache or dizziness but often they complain of a vague mental unwellness. “Brain fog,” a term that has emerged in the wake of the COVID pandemic, might be an apt descriptor. Management of these slow recoverers has been a challenge.

However, two recent articles in the journal Pediatrics may provide some clarity and offer guidance in their management. In a study coming from the psychology department at Georgia State University, researchers reported that they have been able to find “no evidence of clinical meaningful differences in IQ after pediatric concussion.” In their words there is “strong evidence against reduced intelligence in the first few weeks to month after pediatric concussion.”

While their findings may simply toss the IQ onto the pile of worthless measures of healing, a companion commentary by Talin Babikian, PhD, a psychologist at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA, provides a more nuanced interpretation. He writes that if we are looking for an explanation when a patient’s recovery is taking longer than we might expect we need to look beyond some structural damage. Maybe the patient has a previously undiagnosed premorbid condition effecting his or her intellectual, cognitive, or learning abilities. Could the stall in improvement be the result of other symptoms? Here fatigue and sleep deprivation may be the culprits. Could some underlying emotional factor such as anxiety or depression be the problem? For example, I have seen patients whose fear of re-injury has prevented their return to full function. And, finally, the patient may be avoiding a “nonpreferred or challenging situation” unrelated to the injury.

In other words, the concussion may simply be the most obvious rip in a fabric that was already frayed and under stress. This kind of broad holistic (a word I usually like to avoid) thinking may be what is lacking as we struggle to understand other mysterious and chronic conditions such as Lyme disease and chronic fatigue syndrome.

While these two papers help provide some clarity in the management of pediatric concussion, what they fail to address is the bigger question of the relationship between head injury and CTE. The answers to that conundrum are enshrouded in a mix of politics and publicity that I doubt will clear in the near future.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Pediatric concussion is one of those rare phenomena in which we may be witnessing its emergence and clarification in a generation. When I was serving as the game doctor for our local high school football team in the 1970s, I and many other physicians had a very simplistic view of concussion. If the patient never lost conscious and had a reasonably intact short-term memory, we didn’t seriously entertain concussion as a diagnosis. “What’s the score and who is the president?” Were my favorite screening questions.

Obviously, we were underdiagnosing and mismanaging concussion. In part thanks to some high-profile athletes who suffered multiple concussions and eventually chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) physicians began to realize that they should be looking more closely at children who sustained a head injury. The diagnostic criteria were expanded to include any injury that even temporarily effected brain function.

With the new appreciation for the risk of multiple concussions, the focus broadened to include the question of when is it safe for the athlete to return to competition. What signs or symptoms can the patient offer us so we can be sure his or her brain is sufficiently recovered? Here we stepped off into a deep abyss of ignorance. Fortunately, it became obvious fairly quickly that imaging studies weren’t going to help us, as they were invariably normal or at least didn’t tell us anything that wasn’t obvious on a physical exam.

If the patient had a headache, complained of dizziness, or manifested amnesia, monitoring the patient was fairly straightforward. But, in the absence of symptoms and no obvious way to determine the pace of recovery of an organ we couldn’t visualize, clinicians were pulling criteria and time tables out of thin air. Guessing that the concussed brain was in some ways like a torn muscle or overstretched tendon, “brain rest” was often suggested. So no TV, no reading, and certainly none of the cerebral challenging activity of school. Fortunately, we don’t hear much about the notion of brain rest anymore and there is at least one study that suggests that patients kept home from school recover more slowly.

But . Sometimes they describe headache or dizziness but often they complain of a vague mental unwellness. “Brain fog,” a term that has emerged in the wake of the COVID pandemic, might be an apt descriptor. Management of these slow recoverers has been a challenge.

However, two recent articles in the journal Pediatrics may provide some clarity and offer guidance in their management. In a study coming from the psychology department at Georgia State University, researchers reported that they have been able to find “no evidence of clinical meaningful differences in IQ after pediatric concussion.” In their words there is “strong evidence against reduced intelligence in the first few weeks to month after pediatric concussion.”

While their findings may simply toss the IQ onto the pile of worthless measures of healing, a companion commentary by Talin Babikian, PhD, a psychologist at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA, provides a more nuanced interpretation. He writes that if we are looking for an explanation when a patient’s recovery is taking longer than we might expect we need to look beyond some structural damage. Maybe the patient has a previously undiagnosed premorbid condition effecting his or her intellectual, cognitive, or learning abilities. Could the stall in improvement be the result of other symptoms? Here fatigue and sleep deprivation may be the culprits. Could some underlying emotional factor such as anxiety or depression be the problem? For example, I have seen patients whose fear of re-injury has prevented their return to full function. And, finally, the patient may be avoiding a “nonpreferred or challenging situation” unrelated to the injury.

In other words, the concussion may simply be the most obvious rip in a fabric that was already frayed and under stress. This kind of broad holistic (a word I usually like to avoid) thinking may be what is lacking as we struggle to understand other mysterious and chronic conditions such as Lyme disease and chronic fatigue syndrome.

While these two papers help provide some clarity in the management of pediatric concussion, what they fail to address is the bigger question of the relationship between head injury and CTE. The answers to that conundrum are enshrouded in a mix of politics and publicity that I doubt will clear in the near future.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

‘Decapitated’ boy saved by surgery team

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

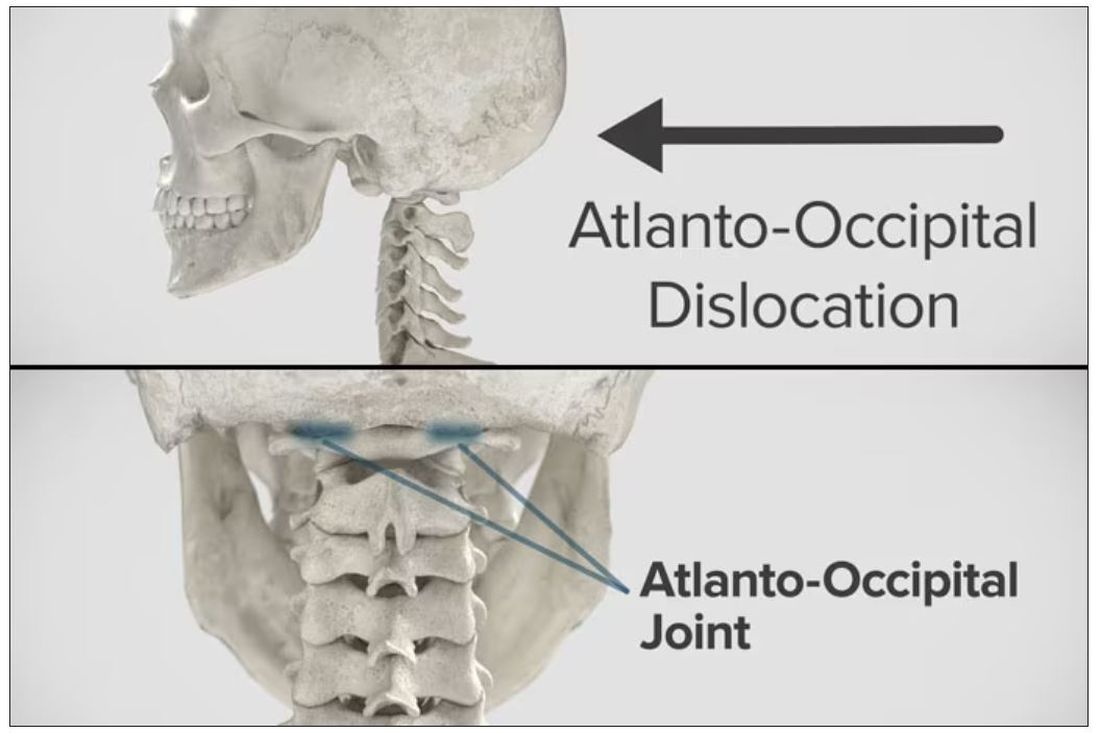

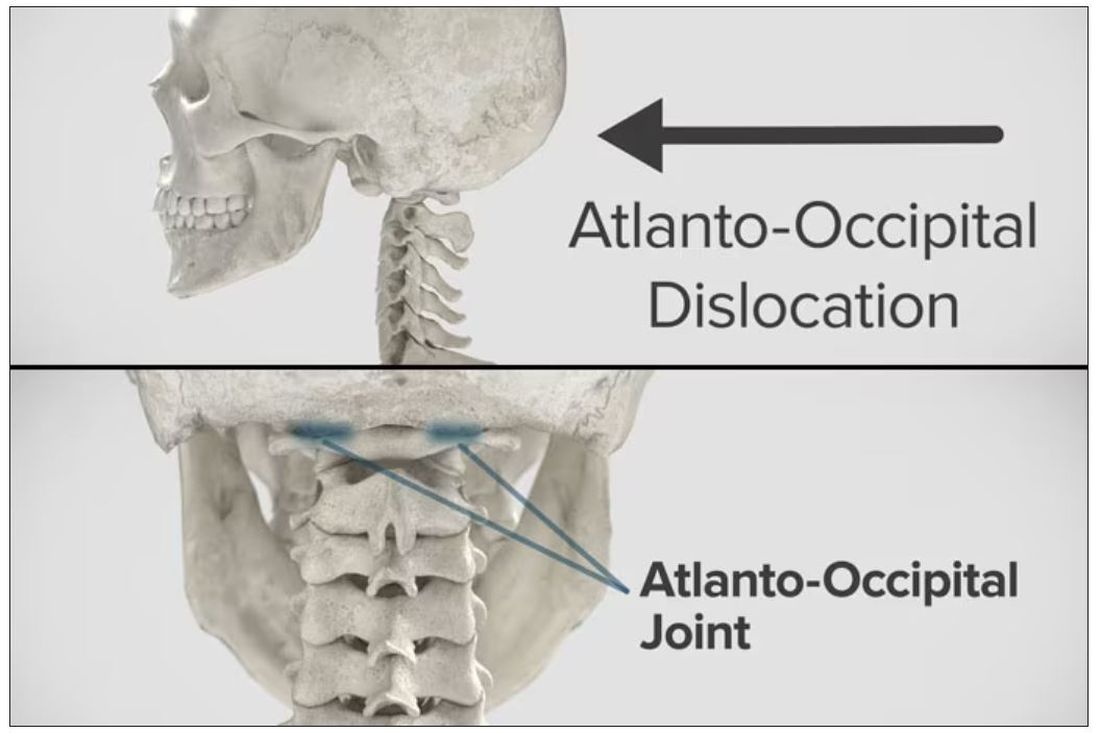

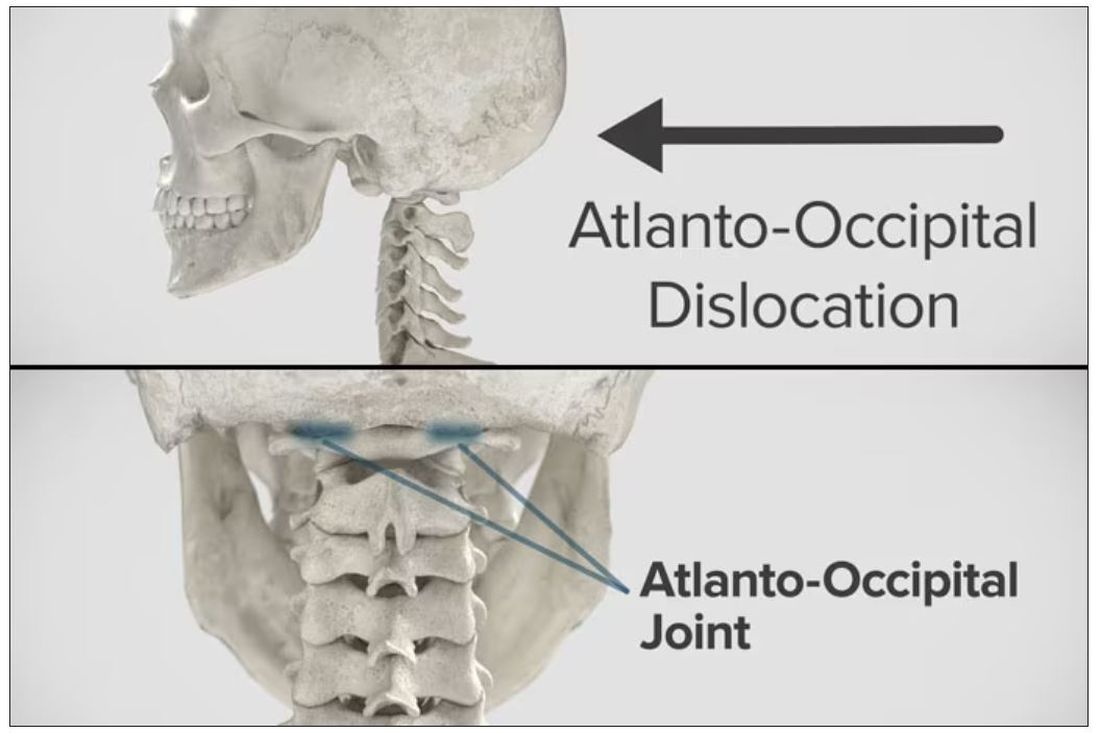

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New guideline for managing toothache in children

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, or both medications together can effectively manage a child’s toothache as a stopgap until definitive treatment is available, according to a new guideline.

The guideline, published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Dental Association, does not recommend opioids for a toothache or after tooth extraction in this population.

Opioid prescriptions for children entail risk for hospitalization and death. Yet, some dentists continued to prescribe contraindicated opioids to young children after a Food and Drug Administration warning in 2017 about the use of tramadol and codeine in this population, the guideline notes.

Opioid prescribing to children also continued after the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry in 2018 recommended acetaminophen and NSAIDs as first-line medications for pain management and said that the use of opioids should be “rare.”

Although the new guidance, which also covers pain management after tooth extraction, is geared toward general dentists, it could help emergency clinicians and primary care providers manage children’s pain when definitive treatment is not immediately available, the authors noted.

Definitive treatment could include pulpectomy, nonsurgical root canal, incision for drainage of an abscess, or tooth extraction.

If definitive care in 2-3 days is not possible, parents should let the health care team know, the guideline says.

“These pharmacologic strategies will alleviate dental pain temporarily until a referral for definitive dental treatment is in place,” the authors wrote.

The American Dental Association (ADA) endorsed the new guideline, which was developed by researchers with the ADA Science & Research Institute, the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, and the Center for Integrative Global Oral Health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in Philadelphia.

The guideline recommends ibuprofen and, for children older than 2 years, naproxen as NSAID options. The use of naproxen in children younger than 12 years for this purpose is off label, they noted.

The guideline suggests doses of acetaminophen and NSAIDs on the basis of age and weight that may differ from those on medication packaging.

“When acetaminophen or NSAIDs are administered as directed, the risk of harm to children from either medication is low,” the guideline states.

“While prescribing opioids to children has become less frequent overall, this guideline ensures that both dentists and parents have evidence-based recommendations to determine the most appropriate treatment for dental pain,” senior guideline author Paul Moore, DMD, PhD, MPH, professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Dental Medicine, said in a news release from the ADA. “Parents and caregivers can take comfort that widely available medications that have no abuse potential, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, are safe and effective for helping their children find relief from short-term dental pain.”

A 2018 review by Dr. Moore and coauthors found that NSAIDs, with or without acetaminophen, were effective and minimized adverse events, relative to opioids, for acute dental pain across ages.

The new recommendations for children will “allow for better treatment of this kind of pain” and “will help prevent unnecessary prescribing of medications with abuse potential, including opioids,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the news release.

The report stems from a 3-year, $1.5 million grant awarded by the FDA in 2020 to the University of Pittsburgh and the ADA Science & Research Institute to develop a clinical practice guideline for the management of acute pain in dentistry in children, adolescents, and adults. The recommendations for adolescents and adults are still in development.

The report was supported by an FDA grant, and the guideline authors received technical and methodologic support from the agency. Some authors disclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, or both medications together can effectively manage a child’s toothache as a stopgap until definitive treatment is available, according to a new guideline.

The guideline, published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Dental Association, does not recommend opioids for a toothache or after tooth extraction in this population.

Opioid prescriptions for children entail risk for hospitalization and death. Yet, some dentists continued to prescribe contraindicated opioids to young children after a Food and Drug Administration warning in 2017 about the use of tramadol and codeine in this population, the guideline notes.

Opioid prescribing to children also continued after the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry in 2018 recommended acetaminophen and NSAIDs as first-line medications for pain management and said that the use of opioids should be “rare.”

Although the new guidance, which also covers pain management after tooth extraction, is geared toward general dentists, it could help emergency clinicians and primary care providers manage children’s pain when definitive treatment is not immediately available, the authors noted.

Definitive treatment could include pulpectomy, nonsurgical root canal, incision for drainage of an abscess, or tooth extraction.

If definitive care in 2-3 days is not possible, parents should let the health care team know, the guideline says.

“These pharmacologic strategies will alleviate dental pain temporarily until a referral for definitive dental treatment is in place,” the authors wrote.

The American Dental Association (ADA) endorsed the new guideline, which was developed by researchers with the ADA Science & Research Institute, the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, and the Center for Integrative Global Oral Health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in Philadelphia.

The guideline recommends ibuprofen and, for children older than 2 years, naproxen as NSAID options. The use of naproxen in children younger than 12 years for this purpose is off label, they noted.

The guideline suggests doses of acetaminophen and NSAIDs on the basis of age and weight that may differ from those on medication packaging.

“When acetaminophen or NSAIDs are administered as directed, the risk of harm to children from either medication is low,” the guideline states.

“While prescribing opioids to children has become less frequent overall, this guideline ensures that both dentists and parents have evidence-based recommendations to determine the most appropriate treatment for dental pain,” senior guideline author Paul Moore, DMD, PhD, MPH, professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Dental Medicine, said in a news release from the ADA. “Parents and caregivers can take comfort that widely available medications that have no abuse potential, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, are safe and effective for helping their children find relief from short-term dental pain.”

A 2018 review by Dr. Moore and coauthors found that NSAIDs, with or without acetaminophen, were effective and minimized adverse events, relative to opioids, for acute dental pain across ages.

The new recommendations for children will “allow for better treatment of this kind of pain” and “will help prevent unnecessary prescribing of medications with abuse potential, including opioids,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the news release.

The report stems from a 3-year, $1.5 million grant awarded by the FDA in 2020 to the University of Pittsburgh and the ADA Science & Research Institute to develop a clinical practice guideline for the management of acute pain in dentistry in children, adolescents, and adults. The recommendations for adolescents and adults are still in development.

The report was supported by an FDA grant, and the guideline authors received technical and methodologic support from the agency. Some authors disclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, or both medications together can effectively manage a child’s toothache as a stopgap until definitive treatment is available, according to a new guideline.

The guideline, published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Dental Association, does not recommend opioids for a toothache or after tooth extraction in this population.

Opioid prescriptions for children entail risk for hospitalization and death. Yet, some dentists continued to prescribe contraindicated opioids to young children after a Food and Drug Administration warning in 2017 about the use of tramadol and codeine in this population, the guideline notes.

Opioid prescribing to children also continued after the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry in 2018 recommended acetaminophen and NSAIDs as first-line medications for pain management and said that the use of opioids should be “rare.”

Although the new guidance, which also covers pain management after tooth extraction, is geared toward general dentists, it could help emergency clinicians and primary care providers manage children’s pain when definitive treatment is not immediately available, the authors noted.

Definitive treatment could include pulpectomy, nonsurgical root canal, incision for drainage of an abscess, or tooth extraction.

If definitive care in 2-3 days is not possible, parents should let the health care team know, the guideline says.

“These pharmacologic strategies will alleviate dental pain temporarily until a referral for definitive dental treatment is in place,” the authors wrote.

The American Dental Association (ADA) endorsed the new guideline, which was developed by researchers with the ADA Science & Research Institute, the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, and the Center for Integrative Global Oral Health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in Philadelphia.

The guideline recommends ibuprofen and, for children older than 2 years, naproxen as NSAID options. The use of naproxen in children younger than 12 years for this purpose is off label, they noted.

The guideline suggests doses of acetaminophen and NSAIDs on the basis of age and weight that may differ from those on medication packaging.

“When acetaminophen or NSAIDs are administered as directed, the risk of harm to children from either medication is low,” the guideline states.

“While prescribing opioids to children has become less frequent overall, this guideline ensures that both dentists and parents have evidence-based recommendations to determine the most appropriate treatment for dental pain,” senior guideline author Paul Moore, DMD, PhD, MPH, professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Dental Medicine, said in a news release from the ADA. “Parents and caregivers can take comfort that widely available medications that have no abuse potential, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, are safe and effective for helping their children find relief from short-term dental pain.”

A 2018 review by Dr. Moore and coauthors found that NSAIDs, with or without acetaminophen, were effective and minimized adverse events, relative to opioids, for acute dental pain across ages.

The new recommendations for children will “allow for better treatment of this kind of pain” and “will help prevent unnecessary prescribing of medications with abuse potential, including opioids,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the news release.

The report stems from a 3-year, $1.5 million grant awarded by the FDA in 2020 to the University of Pittsburgh and the ADA Science & Research Institute to develop a clinical practice guideline for the management of acute pain in dentistry in children, adolescents, and adults. The recommendations for adolescents and adults are still in development.

The report was supported by an FDA grant, and the guideline authors received technical and methodologic support from the agency. Some authors disclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Innovations in pediatric chronic pain management

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

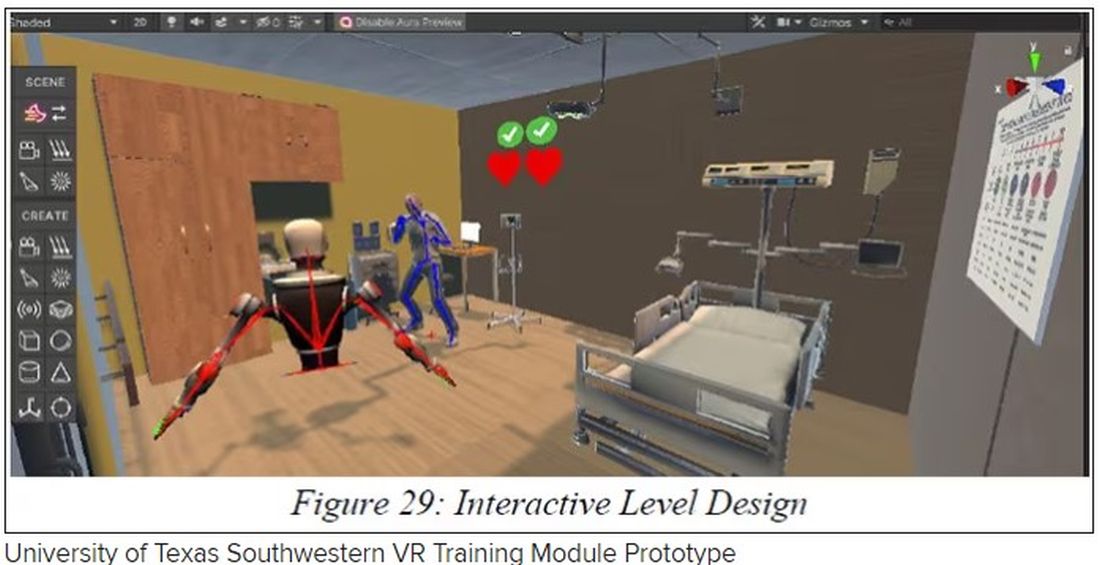

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.