User login

Integrating mental health and primary care: From dipping a toe to taking a plunge

In case anybody hasn’t noticed, the good ole days are long gone in which pediatric patients with mental health challenges could be simply referred out to be promptly assessed and treated by specialists. Due to a shortage of psychiatrists coupled with large increases in the number of youth presenting with emotional-behavioral difficulties, primary care clinicians are now called upon to fill in much of this gap, with professional organizations like the AAP articulating that .1

To meet this need, new models of integrated or collaborative care between primary care and mental health clinicians have been attempted and tested. While these initiatives have certainly been a welcome advance to many pediatricians, the large numbers of different models and initiatives out there have made for a rather confusing landscape that many busy primary care clinicians have found difficult to navigate.

In an attempt to offer some guidance on the subject, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently published a clinical update on pediatric collaborative care.2 The report is rich with resources and ideas. One of the main points of the document is that there are different levels of integration that exist. Kind of like the situation with recycling and household waste reduction, it is possible to make valuable improvements at any level of participation, although evidence suggests that more extensive efforts offer the most benefits. At one end of the spectrum, psychiatrists and primary care clinicians maintain separate practices and medical records and occasionally discuss mutual patients. Middle levels may include “colocation” with mental health and primary care professionals sharing a building and/or being part of the same overall system but continuing to work mainly independently. At the highest levels of integration, there is a coordinated and collaborative team that supports an intentional system of care with consistent communication about individual patients and general workflows. These approaches vary in the amount that the following four core areas of integrated care are incorporated.

- Direct service. Many integrated care initiatives heavily rely on the services of an on-site mental health care manager or behavioral health consultant who can provide a number of important functions such as overseeing of the integrated care program, conducting brief therapy with youth and parents, overseeing mental health screenings at the clinic, and providing general mental health promotion guidance.

- Care coordination. Helping patients and families find needed mental health, social services, and educational resources is a key component of integrated care. This task can fall to the practice’s behavioral health consultant, if there is one, but more general care coordinators can also be trained for this important role. The University of Washington’s Center for Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions has some published guidelines in this area.3

- Consultation. More advanced integrated care models often have established relationships to specific child psychiatric clinicians who are able to meet with the primary care team to discuss cases and general approaches to various problems. Alternatively, a number of states have implemented what are called Child Psychiatry Access Programs that give primary care clinicians a phone number to an organization (often affiliated with an academic medical center) that can provide quick and even immediate access to a child psychiatry provider for specific questions. Recent federal grants have led to many if not most states now having one of these programs in place, and a website listing these programs and their contact information is available.4

- Education. As mental health training was traditionally not part of a typical pediatrics residency, there have been a number of strategies introduced to help primary care clinicians increase their proficiency and comfort level when it comes to assessing and treating emotional-behavioral problems. These include specific conferences, online programs, and case-based training through mechanisms like the ECHO program.5,6 The AAP itself has released a number of toolkits and training materials related to mental health care that are available.7

The report also outlines some obstacles that continue to get in the way of more extensive integrative care efforts. Chief among them are financial concerns, including how to pay for what often are traditionally nonbillable efforts, particularly those that involve the communication of two expensive health care professionals. Some improvements have been made, however, such as the creation of some relatively new codes (such as 99451 and 99452) that can be submitted by both a primary care and mental health professional when there is a consultation that occurs that does not involve an actual face-to-face encounter.

One area that, in my view, has not received the level of attention it deserves when it comes to integrated care is the degree to which these programs have the potential not only to improve the care of children and adolescents already struggling with mental health challenges but also to serve as a powerful prevention tool to lower the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in the future and generally to improve levels of well-being. Thus far, however, research on various integrated programs has shown promising results that indicate that overall care for patients with mental health challenges improves.8 Further, when it comes to costs, there is some evidence to suggest that some of the biggest financial gains associated with integrated care has to do with reduced nonpsychiatric medical expenses of patients.9 This, then, suggests that practices that participate in capitated or accountable care organization structures could particularly benefit both clinically and financially from these collaborations.

If your practice has been challenged with the level of mental health care you are now expected to provide and has been contemplating even some small moves toward integrated care, now may the time to put those thoughts into action.

References

1. Foy JM et al. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement. Mental health competencies for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192757.

2. AACAP Committee on Collaborative and Integrated Care and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Collaborative mental health care for children and adolescents in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119.

3. Behavioral health care managers. AIMS Center, University of Washington. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://aims.uw.edu/online-bhcm-modules.

4. National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://www.nncpap.org/.

5. Project Echo Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo.

6. Project TEACH. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://projectteachny.org.

7. Earls MF et al. Addressing mental health concerns in pediatrics: A practical resource toolkit for clinicians, 2nd edition. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021.

8. Asarnow JR et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929-37.

9. Unutzer J et al. Long-term costs effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008.14(2):95-100.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

In case anybody hasn’t noticed, the good ole days are long gone in which pediatric patients with mental health challenges could be simply referred out to be promptly assessed and treated by specialists. Due to a shortage of psychiatrists coupled with large increases in the number of youth presenting with emotional-behavioral difficulties, primary care clinicians are now called upon to fill in much of this gap, with professional organizations like the AAP articulating that .1

To meet this need, new models of integrated or collaborative care between primary care and mental health clinicians have been attempted and tested. While these initiatives have certainly been a welcome advance to many pediatricians, the large numbers of different models and initiatives out there have made for a rather confusing landscape that many busy primary care clinicians have found difficult to navigate.

In an attempt to offer some guidance on the subject, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently published a clinical update on pediatric collaborative care.2 The report is rich with resources and ideas. One of the main points of the document is that there are different levels of integration that exist. Kind of like the situation with recycling and household waste reduction, it is possible to make valuable improvements at any level of participation, although evidence suggests that more extensive efforts offer the most benefits. At one end of the spectrum, psychiatrists and primary care clinicians maintain separate practices and medical records and occasionally discuss mutual patients. Middle levels may include “colocation” with mental health and primary care professionals sharing a building and/or being part of the same overall system but continuing to work mainly independently. At the highest levels of integration, there is a coordinated and collaborative team that supports an intentional system of care with consistent communication about individual patients and general workflows. These approaches vary in the amount that the following four core areas of integrated care are incorporated.

- Direct service. Many integrated care initiatives heavily rely on the services of an on-site mental health care manager or behavioral health consultant who can provide a number of important functions such as overseeing of the integrated care program, conducting brief therapy with youth and parents, overseeing mental health screenings at the clinic, and providing general mental health promotion guidance.

- Care coordination. Helping patients and families find needed mental health, social services, and educational resources is a key component of integrated care. This task can fall to the practice’s behavioral health consultant, if there is one, but more general care coordinators can also be trained for this important role. The University of Washington’s Center for Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions has some published guidelines in this area.3

- Consultation. More advanced integrated care models often have established relationships to specific child psychiatric clinicians who are able to meet with the primary care team to discuss cases and general approaches to various problems. Alternatively, a number of states have implemented what are called Child Psychiatry Access Programs that give primary care clinicians a phone number to an organization (often affiliated with an academic medical center) that can provide quick and even immediate access to a child psychiatry provider for specific questions. Recent federal grants have led to many if not most states now having one of these programs in place, and a website listing these programs and their contact information is available.4

- Education. As mental health training was traditionally not part of a typical pediatrics residency, there have been a number of strategies introduced to help primary care clinicians increase their proficiency and comfort level when it comes to assessing and treating emotional-behavioral problems. These include specific conferences, online programs, and case-based training through mechanisms like the ECHO program.5,6 The AAP itself has released a number of toolkits and training materials related to mental health care that are available.7

The report also outlines some obstacles that continue to get in the way of more extensive integrative care efforts. Chief among them are financial concerns, including how to pay for what often are traditionally nonbillable efforts, particularly those that involve the communication of two expensive health care professionals. Some improvements have been made, however, such as the creation of some relatively new codes (such as 99451 and 99452) that can be submitted by both a primary care and mental health professional when there is a consultation that occurs that does not involve an actual face-to-face encounter.

One area that, in my view, has not received the level of attention it deserves when it comes to integrated care is the degree to which these programs have the potential not only to improve the care of children and adolescents already struggling with mental health challenges but also to serve as a powerful prevention tool to lower the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in the future and generally to improve levels of well-being. Thus far, however, research on various integrated programs has shown promising results that indicate that overall care for patients with mental health challenges improves.8 Further, when it comes to costs, there is some evidence to suggest that some of the biggest financial gains associated with integrated care has to do with reduced nonpsychiatric medical expenses of patients.9 This, then, suggests that practices that participate in capitated or accountable care organization structures could particularly benefit both clinically and financially from these collaborations.

If your practice has been challenged with the level of mental health care you are now expected to provide and has been contemplating even some small moves toward integrated care, now may the time to put those thoughts into action.

References

1. Foy JM et al. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement. Mental health competencies for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192757.

2. AACAP Committee on Collaborative and Integrated Care and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Collaborative mental health care for children and adolescents in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119.

3. Behavioral health care managers. AIMS Center, University of Washington. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://aims.uw.edu/online-bhcm-modules.

4. National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://www.nncpap.org/.

5. Project Echo Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo.

6. Project TEACH. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://projectteachny.org.

7. Earls MF et al. Addressing mental health concerns in pediatrics: A practical resource toolkit for clinicians, 2nd edition. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021.

8. Asarnow JR et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929-37.

9. Unutzer J et al. Long-term costs effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008.14(2):95-100.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

In case anybody hasn’t noticed, the good ole days are long gone in which pediatric patients with mental health challenges could be simply referred out to be promptly assessed and treated by specialists. Due to a shortage of psychiatrists coupled with large increases in the number of youth presenting with emotional-behavioral difficulties, primary care clinicians are now called upon to fill in much of this gap, with professional organizations like the AAP articulating that .1

To meet this need, new models of integrated or collaborative care between primary care and mental health clinicians have been attempted and tested. While these initiatives have certainly been a welcome advance to many pediatricians, the large numbers of different models and initiatives out there have made for a rather confusing landscape that many busy primary care clinicians have found difficult to navigate.

In an attempt to offer some guidance on the subject, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently published a clinical update on pediatric collaborative care.2 The report is rich with resources and ideas. One of the main points of the document is that there are different levels of integration that exist. Kind of like the situation with recycling and household waste reduction, it is possible to make valuable improvements at any level of participation, although evidence suggests that more extensive efforts offer the most benefits. At one end of the spectrum, psychiatrists and primary care clinicians maintain separate practices and medical records and occasionally discuss mutual patients. Middle levels may include “colocation” with mental health and primary care professionals sharing a building and/or being part of the same overall system but continuing to work mainly independently. At the highest levels of integration, there is a coordinated and collaborative team that supports an intentional system of care with consistent communication about individual patients and general workflows. These approaches vary in the amount that the following four core areas of integrated care are incorporated.

- Direct service. Many integrated care initiatives heavily rely on the services of an on-site mental health care manager or behavioral health consultant who can provide a number of important functions such as overseeing of the integrated care program, conducting brief therapy with youth and parents, overseeing mental health screenings at the clinic, and providing general mental health promotion guidance.

- Care coordination. Helping patients and families find needed mental health, social services, and educational resources is a key component of integrated care. This task can fall to the practice’s behavioral health consultant, if there is one, but more general care coordinators can also be trained for this important role. The University of Washington’s Center for Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions has some published guidelines in this area.3

- Consultation. More advanced integrated care models often have established relationships to specific child psychiatric clinicians who are able to meet with the primary care team to discuss cases and general approaches to various problems. Alternatively, a number of states have implemented what are called Child Psychiatry Access Programs that give primary care clinicians a phone number to an organization (often affiliated with an academic medical center) that can provide quick and even immediate access to a child psychiatry provider for specific questions. Recent federal grants have led to many if not most states now having one of these programs in place, and a website listing these programs and their contact information is available.4

- Education. As mental health training was traditionally not part of a typical pediatrics residency, there have been a number of strategies introduced to help primary care clinicians increase their proficiency and comfort level when it comes to assessing and treating emotional-behavioral problems. These include specific conferences, online programs, and case-based training through mechanisms like the ECHO program.5,6 The AAP itself has released a number of toolkits and training materials related to mental health care that are available.7

The report also outlines some obstacles that continue to get in the way of more extensive integrative care efforts. Chief among them are financial concerns, including how to pay for what often are traditionally nonbillable efforts, particularly those that involve the communication of two expensive health care professionals. Some improvements have been made, however, such as the creation of some relatively new codes (such as 99451 and 99452) that can be submitted by both a primary care and mental health professional when there is a consultation that occurs that does not involve an actual face-to-face encounter.

One area that, in my view, has not received the level of attention it deserves when it comes to integrated care is the degree to which these programs have the potential not only to improve the care of children and adolescents already struggling with mental health challenges but also to serve as a powerful prevention tool to lower the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in the future and generally to improve levels of well-being. Thus far, however, research on various integrated programs has shown promising results that indicate that overall care for patients with mental health challenges improves.8 Further, when it comes to costs, there is some evidence to suggest that some of the biggest financial gains associated with integrated care has to do with reduced nonpsychiatric medical expenses of patients.9 This, then, suggests that practices that participate in capitated or accountable care organization structures could particularly benefit both clinically and financially from these collaborations.

If your practice has been challenged with the level of mental health care you are now expected to provide and has been contemplating even some small moves toward integrated care, now may the time to put those thoughts into action.

References

1. Foy JM et al. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement. Mental health competencies for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192757.

2. AACAP Committee on Collaborative and Integrated Care and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Collaborative mental health care for children and adolescents in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119.

3. Behavioral health care managers. AIMS Center, University of Washington. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://aims.uw.edu/online-bhcm-modules.

4. National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://www.nncpap.org/.

5. Project Echo Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo.

6. Project TEACH. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://projectteachny.org.

7. Earls MF et al. Addressing mental health concerns in pediatrics: A practical resource toolkit for clinicians, 2nd edition. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021.

8. Asarnow JR et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929-37.

9. Unutzer J et al. Long-term costs effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008.14(2):95-100.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

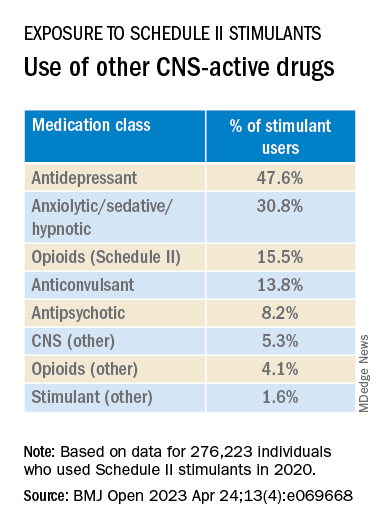

Widespread prescribing of stimulants with other CNS-active meds

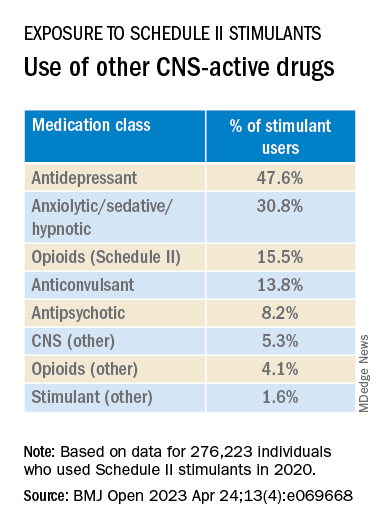

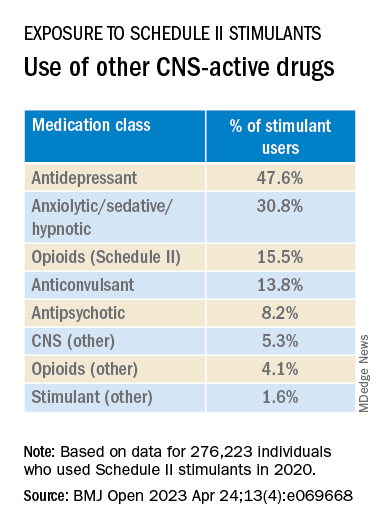

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Most children with ADHD are not receiving treatment

Just more than one-third (34.8%) had received either treatment.

Researchers, led by Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law and professor of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, also found that girls were much less likely to get medications.

In this cross-sectional sample taken from 11, 723 children in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, 1,206 children aged 9 and 10 years had parent-reported ADHD, and of those children, 15.7% of boys and 7% of girls were currently receiving ADHD medications. The parents reported the children met ADHD criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Diagnoses have doubled but treatment numbers lag

Report authors noted that the percentage of U.S. children whose parents report their child has been diagnosed with ADHD has nearly doubled over 2 decades from 5.5% in 1999 to 9.8% in 2018. That has led to misperceptions among professionals and the public that the disorder is overdiagnosed and overtreated, the authors wrote.

However, they wrote, “a focus on the increasing numbers of children treated for ADHD does not give a sense of what fraction of children in the population with ADHD receive treatment.”

Higher uptake at lower income and education levels

Researchers also found that, contrary to popular belief, children with ADHD from families with lower educational levels and lower income were more likely than those with higher educational levels and higher incomes to have received outpatient mental health care.

Among children with ADHD whose parents did not have a high school education, 32.2% of children were receiving medications while among children of parents with a bachelor’s degree 11.5% received medications.

Among children from families with incomes of less than $25 000, 36.5% were receiving outpatient mental health care, compared with 20.1% of those from families with incomes of $75,000 or more.

“These patterns suggest that attitudinal rather than socioeconomic factors often impede the flow of children with ADHD into treatment,” they wrote.

Black children less likely to receive medications

The researchers found that substantially more White children (14.8% [104 of 759]) than Black children (9.4% [22 of 206]), received medication, a finding consistent with previous research.

“Population-based racial and ethnic gradients exist in prescriptions for stimulants and other controlled substances, with the highest rates in majority-White areas,” the authors wrote. “As a result of structural racism, Black parents’ perspectives might further influence ADHD management decisions through mistrust in clinicians and concerns over safety and efficacy of stimulants.”

“Physician efforts to recognize and manage their own implicit biases, together with patient-centered clinical approaches that promote shared decision-making,” might help narrow the treatment gap, the authors wrote. That includes talking with Black parents about their knowledge and beliefs concerning managing ADHD, they added.

Confirming diagnosis critical

The authors noted that not all children with parent-reported ADHD need treatment or would benefit from it.

Lenard Adler, MD, director of the adult ADHD program and professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone Health, who was not part of the current study, said this research emphasizes the urgency of clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Adler was part of a team of researchers that found similar low numbers for treatment among adults with ADHD.

The current results highlight that “we want to get the diagnosis correct so that people who receive a diagnosis actually have it and, if they do, that they have access to care. Because the consequences for not having treatment for ADHD are significant,” Dr. Adler said.

He urged physicians who diagnose ADHD to make follow-up part of the care plan or these treatment gaps will persist.

The authors wrote that the results suggest a need to increase availability for mental health services and better communicate symptoms among parents, teachers, and primary care providers.

The authors declare no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adler has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, has done research with Takeda, and has received royalty payments from NYU for licensing of ADHD training materials.

Just more than one-third (34.8%) had received either treatment.

Researchers, led by Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law and professor of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, also found that girls were much less likely to get medications.

In this cross-sectional sample taken from 11, 723 children in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, 1,206 children aged 9 and 10 years had parent-reported ADHD, and of those children, 15.7% of boys and 7% of girls were currently receiving ADHD medications. The parents reported the children met ADHD criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Diagnoses have doubled but treatment numbers lag

Report authors noted that the percentage of U.S. children whose parents report their child has been diagnosed with ADHD has nearly doubled over 2 decades from 5.5% in 1999 to 9.8% in 2018. That has led to misperceptions among professionals and the public that the disorder is overdiagnosed and overtreated, the authors wrote.

However, they wrote, “a focus on the increasing numbers of children treated for ADHD does not give a sense of what fraction of children in the population with ADHD receive treatment.”

Higher uptake at lower income and education levels

Researchers also found that, contrary to popular belief, children with ADHD from families with lower educational levels and lower income were more likely than those with higher educational levels and higher incomes to have received outpatient mental health care.

Among children with ADHD whose parents did not have a high school education, 32.2% of children were receiving medications while among children of parents with a bachelor’s degree 11.5% received medications.

Among children from families with incomes of less than $25 000, 36.5% were receiving outpatient mental health care, compared with 20.1% of those from families with incomes of $75,000 or more.

“These patterns suggest that attitudinal rather than socioeconomic factors often impede the flow of children with ADHD into treatment,” they wrote.

Black children less likely to receive medications

The researchers found that substantially more White children (14.8% [104 of 759]) than Black children (9.4% [22 of 206]), received medication, a finding consistent with previous research.

“Population-based racial and ethnic gradients exist in prescriptions for stimulants and other controlled substances, with the highest rates in majority-White areas,” the authors wrote. “As a result of structural racism, Black parents’ perspectives might further influence ADHD management decisions through mistrust in clinicians and concerns over safety and efficacy of stimulants.”

“Physician efforts to recognize and manage their own implicit biases, together with patient-centered clinical approaches that promote shared decision-making,” might help narrow the treatment gap, the authors wrote. That includes talking with Black parents about their knowledge and beliefs concerning managing ADHD, they added.

Confirming diagnosis critical

The authors noted that not all children with parent-reported ADHD need treatment or would benefit from it.

Lenard Adler, MD, director of the adult ADHD program and professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone Health, who was not part of the current study, said this research emphasizes the urgency of clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Adler was part of a team of researchers that found similar low numbers for treatment among adults with ADHD.

The current results highlight that “we want to get the diagnosis correct so that people who receive a diagnosis actually have it and, if they do, that they have access to care. Because the consequences for not having treatment for ADHD are significant,” Dr. Adler said.

He urged physicians who diagnose ADHD to make follow-up part of the care plan or these treatment gaps will persist.

The authors wrote that the results suggest a need to increase availability for mental health services and better communicate symptoms among parents, teachers, and primary care providers.

The authors declare no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adler has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, has done research with Takeda, and has received royalty payments from NYU for licensing of ADHD training materials.

Just more than one-third (34.8%) had received either treatment.

Researchers, led by Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law and professor of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, also found that girls were much less likely to get medications.

In this cross-sectional sample taken from 11, 723 children in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, 1,206 children aged 9 and 10 years had parent-reported ADHD, and of those children, 15.7% of boys and 7% of girls were currently receiving ADHD medications. The parents reported the children met ADHD criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Diagnoses have doubled but treatment numbers lag

Report authors noted that the percentage of U.S. children whose parents report their child has been diagnosed with ADHD has nearly doubled over 2 decades from 5.5% in 1999 to 9.8% in 2018. That has led to misperceptions among professionals and the public that the disorder is overdiagnosed and overtreated, the authors wrote.

However, they wrote, “a focus on the increasing numbers of children treated for ADHD does not give a sense of what fraction of children in the population with ADHD receive treatment.”

Higher uptake at lower income and education levels

Researchers also found that, contrary to popular belief, children with ADHD from families with lower educational levels and lower income were more likely than those with higher educational levels and higher incomes to have received outpatient mental health care.

Among children with ADHD whose parents did not have a high school education, 32.2% of children were receiving medications while among children of parents with a bachelor’s degree 11.5% received medications.

Among children from families with incomes of less than $25 000, 36.5% were receiving outpatient mental health care, compared with 20.1% of those from families with incomes of $75,000 or more.

“These patterns suggest that attitudinal rather than socioeconomic factors often impede the flow of children with ADHD into treatment,” they wrote.

Black children less likely to receive medications

The researchers found that substantially more White children (14.8% [104 of 759]) than Black children (9.4% [22 of 206]), received medication, a finding consistent with previous research.

“Population-based racial and ethnic gradients exist in prescriptions for stimulants and other controlled substances, with the highest rates in majority-White areas,” the authors wrote. “As a result of structural racism, Black parents’ perspectives might further influence ADHD management decisions through mistrust in clinicians and concerns over safety and efficacy of stimulants.”

“Physician efforts to recognize and manage their own implicit biases, together with patient-centered clinical approaches that promote shared decision-making,” might help narrow the treatment gap, the authors wrote. That includes talking with Black parents about their knowledge and beliefs concerning managing ADHD, they added.

Confirming diagnosis critical

The authors noted that not all children with parent-reported ADHD need treatment or would benefit from it.

Lenard Adler, MD, director of the adult ADHD program and professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone Health, who was not part of the current study, said this research emphasizes the urgency of clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Adler was part of a team of researchers that found similar low numbers for treatment among adults with ADHD.

The current results highlight that “we want to get the diagnosis correct so that people who receive a diagnosis actually have it and, if they do, that they have access to care. Because the consequences for not having treatment for ADHD are significant,” Dr. Adler said.

He urged physicians who diagnose ADHD to make follow-up part of the care plan or these treatment gaps will persist.

The authors wrote that the results suggest a need to increase availability for mental health services and better communicate symptoms among parents, teachers, and primary care providers.

The authors declare no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adler has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, has done research with Takeda, and has received royalty payments from NYU for licensing of ADHD training materials.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Long-term impact of childhood trauma explained

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ADAA 2023

ASCO updates treatment guidelines for anxiety and depression

Since the last guidelines, published in 2014, screening and assessment for depression and anxiety have improved, and a large new evidence base has emerged. To ensure the most up-to-date recommendations, a group of experts spanning psychology, psychiatry, medical and surgical oncology, internal medicine, and nursing convened to review the current literature on managing depression and anxiety. The review included 61 studies – 16 meta-analyses, 44 randomized controlled trials, and one systematic review – published between 2013 and 2021.

“The purpose of this guideline update is to gather and examine the evidence published since the 2014 guideline ... [with a] focus on management and treatment only.” The overall goal is to provide “the most effective and least resource-intensive intervention based on symptom severity” for patients with cancer, the experts write.

The new clinical practice guideline addresses the following question: What are the recommended treatment approaches in the management of anxiety and/or depression in survivors of adult cancer?

After an extensive literature search and analysis, the study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The expert panel’s recommendations fell into three broad categories – general management principles, treatment and care options for depressive symptoms, and treatment and care options for anxiety symptoms – with the guidelines for managing depression and anxiety largely mirroring each other.

The authors caution, however, that the guidelines “were developed in the context of mental health care being available and may not be applicable within other resource settings.”

General management principals

All patients with cancer, along with their caregivers, family members, or trusted confidants, should be offered information and resources on depression and anxiety. The panel gave this a “strong” recommendation but provided the caveat that the “information should be culturally informed and linguistically appropriate and can include a conversation between clinician and patient.”

Clinicians should select the most effective and least intensive intervention based on symptom severity when selecting treatment – what the panelists referred to as a stepped-care model. History of psychiatric diagnoses or substance use as well as prior responses to mental health treatment are some of the factors that may inform treatment choice.

For patients experiencing both depression and anxiety symptoms, treatment of depressive symptoms should be prioritized.

When referring a patient for further evaluation or care, clinicians “should make every effort to reduce barriers and facilitate patient follow-through,” the authors write. And health care professionals should regularly assess the treatment responses for patients receiving psychological or pharmacological interventions.

Overall, the treatments should be “supervised by a psychiatrist, and primary care or oncology providers work collaboratively with a nurse care manager to provide psychological interventions and monitor treatment compliance and outcomes,” the panelists write. “This type of collaborative care is found to be superior to usual care and is more cost-effective than face-to-face and pharmacologic treatment for depression.”

Treatment and care options for depressive and anxiety symptoms