User login

For MD-IQ use only

A First Look at the VA MISSION Act Veteran Health Administration Medical School Scholarship and Loan Repayment Programs

As one of 4 statutory missions, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) educates and trains health professionals to enhance the quality of and timely access to care provided to veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). To achieve its mission to

Despite its long-term success affiliating with medical schools, VA has continued to be challenged by physician staff shortages with wide variability in the number and specialty of available health care professionals across facilities.3,4 A 2020 VA Office of Inspector General report on VHA occupational staffing shortages concluded that numerous physician specialties were difficult to recruit due to a lack of qualified applicants, noncompetitive salary, and less desirable geographic locations.3

Federal health professions scholarship programs and loan repayment programs have long been used to address physician shortages.4 Focusing on physician shortages in underserved areas in the US, the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970 and its subsequent amendments paved the way for various federal medical school scholarship and loan repayment programs.5 Similarly, physician shortages in the armed forces were mitigated through the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972 (USHPRA).6,7

In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION (Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks) Act, which included sections designed to alleviate physician shortages in the VHA.8 These sections authorized scholarships similar to those offered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and loan repayment programs. Section 301 created the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), which offers scholarships for physicians and dentists. Section 302 increased the maximum debt reduction through the Education Debt Reduction Program (EDRP). Section 303 authorizes the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program (SELRP), which provides for repayment of educational loans for physicians in specialties deemed necessary for VA. Finally, Section 304 created the Veterans Healing Veterans (VHV), a pilot scholarship specifically for veteran medical students.

Program Characteristics

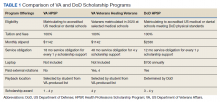

Health Professions Scholarship

The VA HPSP is a program for physicians and dentists that extends from 2020 to 2033. The HPSP funds the costs of tuition, fees, and provides a stipend with a service obligation of 18 months for each year of support. The program is authorized for 10 years and must provide a minimum of 50 scholarships annually for physicians or dentists based on VHA needs. Applications are screened based on criteria that include a commitment to rural or underserved populations, veteran status, grade point average, essays, and letters of recommendation. Although the minimum required number of scholarships annually is 50, VA anticipates providing 1000 scholarships over 10 years with an aim to significantly increase the number physicians at VHA facilities (Table 1).

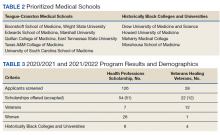

Implemented in 2020, the VHV was a 1-year pilot program. It offered scholarships to 2 veterans attending medical school at each of the 5 Teague-Cranston and the 4 Historically Black College and University (HBCU) medical schools (Table 2). The intent of the program was to determine the feasibility of increasing the pool of veteran physicians at VHA. Eligible applicants were notified of the scholarship opportunity through the American Medical College Application Service or through the medical school. Applicants must have separated from military service within the preceding 10 years of being admitted to medical school. In exchange for full tuition, fees, a monthly stipend, and rotation travel costs, the recipients accepted a 4-year clinical service obligation at VA facilities after completing their residency training.

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

The SELRP is a loan repayment program available to recently graduated physicians. Applicants must have graduated from an accredited medical or osteopathic school, matched to an accredited residency program and be ≥ 2 years from completion of residency. The specialties qualifying for SELRP are determined through an analysis of succession planning by the VA Office of Workforce Management and Consulting and change based on VA physician workforce needs. The SELRP provides loan repayment in the amount of $40,000 per year for up to 4 years, with a service obligation of 1 year for each $40,000 of support. In April 2021, VA began accepting applications from the eligible specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and geriatrics.

Education Debt Reduction

The EDRP offers debt relief to clinicians in the most difficult to recruit professions, including physicians (generalists and specialists), registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The list of difficult to recruit positions is developed annually by VA facilities. Annual reimbursements through the program may be used for tuition and expenses, such as fees, books, supplies, equipment, and other materials. In 2018, through the MISSION Act Section 302, the annual loan repayment was increased from $24,000 to $40,000, and the maximum level of support was increased from $120,000 to $200,000 over 5 years. Recipients receive reimbursement for loan repayment at the end of each year or service period and recipients are not required to remain in VA for 5 years.

Program Results

Health Professions Scholarship

For academic years 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, 126 HPSP applications from both allopathic and osteopathic schools were submitted and 51 scholarships were awarded (Table 3). Assuming an average residency length of 4 years, VHA estimates that these awards will yield 204 service-year equivalents by 2029.

Veterans Healing Veterans

In the VHV program, scholarship recipients came from 5 Teague-Cranston schools; 2 at University of South Carolina, 2 at East Tennessee State University, 2 at Wright State University, 1 at Texas A&M College of Medicine, 1 at Marshall University; and 3 HBCUs; 2 at Howard University, 1 at Morehouse School of Medicine and 1 at Meharry Medical College. The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science did not nominate any students for the scholarship. Assuming all recipients complete postgraduate training, the VHV scholarship program will provide an additional 12 veteran physicians to serve at VA for at least 4 years each (48 service years).

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

Fourteen applicants have been approved, including 5 in psychiatry, 4 in family medicine, 3 in internal medicine, 1 in emergency medicine, and 1 in geriatrics. The mean loan repayment is anticipated to be $110,000 and equating to 38.5 VA service years or a mean of 2.3 years of service obligation per individual for the first cohort. The program has no termination date, and with continued funding, VA anticipates granting 100 loan repayments annually.

Education Debt Reduction

Since 2018, 1,546 VA physicians have received EDRP awards. Due to the increased reimbursement provided through the MISSION Act, average physician award amounts have increased from $96,090 in 2018 to $142,557 in 2019 and $148,302 in 2020.

Conclusions

The VA physician scholarship and loan repayment programs outlined in the MISSION Act build on the success of existing federal scholarship programs by providing opportunities for physician trainees to alleviate educational debt and explore a VA health professions career.

Looking ahead, VA must focus on measuring the success of the MISSION scholarship and loan repayment programs by tracking rates of acceptance and student graduation, residency and fellowship completion, and placement in VA medical facilities—both for the service obligation and future employment. Ultimately, the total impact on VA staffing, especially at rural and underresourced sites, will determine the success of the MISSION programs.

1. VA Policy Memorandum #2. Policy in Association of Veterans’ Hospitals with Medical Schools. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 20, 1946. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf 2. Gilman SC, Chang BK, Zeiss RA, Dougherty MB, Marks WJ, Ludke DA, Cox M. “The academic mission of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” In: Praeger Handbook of Veterans’ Health: History, Challenges, Issues, and Developments. Praeger; 2012:53-82.

3. Office of Inspector General, Veterans Health Administration OIG Determination of VHA Occupational Staffing Shortages FY2020. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published September 23, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-20-01249-259.pdf

4. Hussey PS, Ringel J, et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(4). Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1165z2/RAND_RR1165z2.pdf

5. Lynch A, Best T, Gutierrez SC, Daily JA. What Should I Do With My Student Loans? A Proposed Strategy for Educational Debt Management. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):11-15. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00279.1

6. The Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972, PL 92-426. US Government Publishing Office. Published 1972. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg713.pdf

7. Armed Forces Health Professions Financial Assistance Programs, 10 USC § 105 (2006).

8. ‘‘VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018’’. H.R. 5674. 115th Congress; Report No. 115-671, Part 1. May 3, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr5674/BILLS-115hr5674rh.pdf

As one of 4 statutory missions, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) educates and trains health professionals to enhance the quality of and timely access to care provided to veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). To achieve its mission to

Despite its long-term success affiliating with medical schools, VA has continued to be challenged by physician staff shortages with wide variability in the number and specialty of available health care professionals across facilities.3,4 A 2020 VA Office of Inspector General report on VHA occupational staffing shortages concluded that numerous physician specialties were difficult to recruit due to a lack of qualified applicants, noncompetitive salary, and less desirable geographic locations.3

Federal health professions scholarship programs and loan repayment programs have long been used to address physician shortages.4 Focusing on physician shortages in underserved areas in the US, the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970 and its subsequent amendments paved the way for various federal medical school scholarship and loan repayment programs.5 Similarly, physician shortages in the armed forces were mitigated through the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972 (USHPRA).6,7

In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION (Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks) Act, which included sections designed to alleviate physician shortages in the VHA.8 These sections authorized scholarships similar to those offered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and loan repayment programs. Section 301 created the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), which offers scholarships for physicians and dentists. Section 302 increased the maximum debt reduction through the Education Debt Reduction Program (EDRP). Section 303 authorizes the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program (SELRP), which provides for repayment of educational loans for physicians in specialties deemed necessary for VA. Finally, Section 304 created the Veterans Healing Veterans (VHV), a pilot scholarship specifically for veteran medical students.

Program Characteristics

Health Professions Scholarship

The VA HPSP is a program for physicians and dentists that extends from 2020 to 2033. The HPSP funds the costs of tuition, fees, and provides a stipend with a service obligation of 18 months for each year of support. The program is authorized for 10 years and must provide a minimum of 50 scholarships annually for physicians or dentists based on VHA needs. Applications are screened based on criteria that include a commitment to rural or underserved populations, veteran status, grade point average, essays, and letters of recommendation. Although the minimum required number of scholarships annually is 50, VA anticipates providing 1000 scholarships over 10 years with an aim to significantly increase the number physicians at VHA facilities (Table 1).

Implemented in 2020, the VHV was a 1-year pilot program. It offered scholarships to 2 veterans attending medical school at each of the 5 Teague-Cranston and the 4 Historically Black College and University (HBCU) medical schools (Table 2). The intent of the program was to determine the feasibility of increasing the pool of veteran physicians at VHA. Eligible applicants were notified of the scholarship opportunity through the American Medical College Application Service or through the medical school. Applicants must have separated from military service within the preceding 10 years of being admitted to medical school. In exchange for full tuition, fees, a monthly stipend, and rotation travel costs, the recipients accepted a 4-year clinical service obligation at VA facilities after completing their residency training.

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

The SELRP is a loan repayment program available to recently graduated physicians. Applicants must have graduated from an accredited medical or osteopathic school, matched to an accredited residency program and be ≥ 2 years from completion of residency. The specialties qualifying for SELRP are determined through an analysis of succession planning by the VA Office of Workforce Management and Consulting and change based on VA physician workforce needs. The SELRP provides loan repayment in the amount of $40,000 per year for up to 4 years, with a service obligation of 1 year for each $40,000 of support. In April 2021, VA began accepting applications from the eligible specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and geriatrics.

Education Debt Reduction

The EDRP offers debt relief to clinicians in the most difficult to recruit professions, including physicians (generalists and specialists), registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The list of difficult to recruit positions is developed annually by VA facilities. Annual reimbursements through the program may be used for tuition and expenses, such as fees, books, supplies, equipment, and other materials. In 2018, through the MISSION Act Section 302, the annual loan repayment was increased from $24,000 to $40,000, and the maximum level of support was increased from $120,000 to $200,000 over 5 years. Recipients receive reimbursement for loan repayment at the end of each year or service period and recipients are not required to remain in VA for 5 years.

Program Results

Health Professions Scholarship

For academic years 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, 126 HPSP applications from both allopathic and osteopathic schools were submitted and 51 scholarships were awarded (Table 3). Assuming an average residency length of 4 years, VHA estimates that these awards will yield 204 service-year equivalents by 2029.

Veterans Healing Veterans

In the VHV program, scholarship recipients came from 5 Teague-Cranston schools; 2 at University of South Carolina, 2 at East Tennessee State University, 2 at Wright State University, 1 at Texas A&M College of Medicine, 1 at Marshall University; and 3 HBCUs; 2 at Howard University, 1 at Morehouse School of Medicine and 1 at Meharry Medical College. The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science did not nominate any students for the scholarship. Assuming all recipients complete postgraduate training, the VHV scholarship program will provide an additional 12 veteran physicians to serve at VA for at least 4 years each (48 service years).

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

Fourteen applicants have been approved, including 5 in psychiatry, 4 in family medicine, 3 in internal medicine, 1 in emergency medicine, and 1 in geriatrics. The mean loan repayment is anticipated to be $110,000 and equating to 38.5 VA service years or a mean of 2.3 years of service obligation per individual for the first cohort. The program has no termination date, and with continued funding, VA anticipates granting 100 loan repayments annually.

Education Debt Reduction

Since 2018, 1,546 VA physicians have received EDRP awards. Due to the increased reimbursement provided through the MISSION Act, average physician award amounts have increased from $96,090 in 2018 to $142,557 in 2019 and $148,302 in 2020.

Conclusions

The VA physician scholarship and loan repayment programs outlined in the MISSION Act build on the success of existing federal scholarship programs by providing opportunities for physician trainees to alleviate educational debt and explore a VA health professions career.

Looking ahead, VA must focus on measuring the success of the MISSION scholarship and loan repayment programs by tracking rates of acceptance and student graduation, residency and fellowship completion, and placement in VA medical facilities—both for the service obligation and future employment. Ultimately, the total impact on VA staffing, especially at rural and underresourced sites, will determine the success of the MISSION programs.

As one of 4 statutory missions, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) educates and trains health professionals to enhance the quality of and timely access to care provided to veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). To achieve its mission to

Despite its long-term success affiliating with medical schools, VA has continued to be challenged by physician staff shortages with wide variability in the number and specialty of available health care professionals across facilities.3,4 A 2020 VA Office of Inspector General report on VHA occupational staffing shortages concluded that numerous physician specialties were difficult to recruit due to a lack of qualified applicants, noncompetitive salary, and less desirable geographic locations.3

Federal health professions scholarship programs and loan repayment programs have long been used to address physician shortages.4 Focusing on physician shortages in underserved areas in the US, the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970 and its subsequent amendments paved the way for various federal medical school scholarship and loan repayment programs.5 Similarly, physician shortages in the armed forces were mitigated through the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972 (USHPRA).6,7

In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION (Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks) Act, which included sections designed to alleviate physician shortages in the VHA.8 These sections authorized scholarships similar to those offered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and loan repayment programs. Section 301 created the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), which offers scholarships for physicians and dentists. Section 302 increased the maximum debt reduction through the Education Debt Reduction Program (EDRP). Section 303 authorizes the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program (SELRP), which provides for repayment of educational loans for physicians in specialties deemed necessary for VA. Finally, Section 304 created the Veterans Healing Veterans (VHV), a pilot scholarship specifically for veteran medical students.

Program Characteristics

Health Professions Scholarship

The VA HPSP is a program for physicians and dentists that extends from 2020 to 2033. The HPSP funds the costs of tuition, fees, and provides a stipend with a service obligation of 18 months for each year of support. The program is authorized for 10 years and must provide a minimum of 50 scholarships annually for physicians or dentists based on VHA needs. Applications are screened based on criteria that include a commitment to rural or underserved populations, veteran status, grade point average, essays, and letters of recommendation. Although the minimum required number of scholarships annually is 50, VA anticipates providing 1000 scholarships over 10 years with an aim to significantly increase the number physicians at VHA facilities (Table 1).

Implemented in 2020, the VHV was a 1-year pilot program. It offered scholarships to 2 veterans attending medical school at each of the 5 Teague-Cranston and the 4 Historically Black College and University (HBCU) medical schools (Table 2). The intent of the program was to determine the feasibility of increasing the pool of veteran physicians at VHA. Eligible applicants were notified of the scholarship opportunity through the American Medical College Application Service or through the medical school. Applicants must have separated from military service within the preceding 10 years of being admitted to medical school. In exchange for full tuition, fees, a monthly stipend, and rotation travel costs, the recipients accepted a 4-year clinical service obligation at VA facilities after completing their residency training.

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

The SELRP is a loan repayment program available to recently graduated physicians. Applicants must have graduated from an accredited medical or osteopathic school, matched to an accredited residency program and be ≥ 2 years from completion of residency. The specialties qualifying for SELRP are determined through an analysis of succession planning by the VA Office of Workforce Management and Consulting and change based on VA physician workforce needs. The SELRP provides loan repayment in the amount of $40,000 per year for up to 4 years, with a service obligation of 1 year for each $40,000 of support. In April 2021, VA began accepting applications from the eligible specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and geriatrics.

Education Debt Reduction

The EDRP offers debt relief to clinicians in the most difficult to recruit professions, including physicians (generalists and specialists), registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The list of difficult to recruit positions is developed annually by VA facilities. Annual reimbursements through the program may be used for tuition and expenses, such as fees, books, supplies, equipment, and other materials. In 2018, through the MISSION Act Section 302, the annual loan repayment was increased from $24,000 to $40,000, and the maximum level of support was increased from $120,000 to $200,000 over 5 years. Recipients receive reimbursement for loan repayment at the end of each year or service period and recipients are not required to remain in VA for 5 years.

Program Results

Health Professions Scholarship

For academic years 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, 126 HPSP applications from both allopathic and osteopathic schools were submitted and 51 scholarships were awarded (Table 3). Assuming an average residency length of 4 years, VHA estimates that these awards will yield 204 service-year equivalents by 2029.

Veterans Healing Veterans

In the VHV program, scholarship recipients came from 5 Teague-Cranston schools; 2 at University of South Carolina, 2 at East Tennessee State University, 2 at Wright State University, 1 at Texas A&M College of Medicine, 1 at Marshall University; and 3 HBCUs; 2 at Howard University, 1 at Morehouse School of Medicine and 1 at Meharry Medical College. The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science did not nominate any students for the scholarship. Assuming all recipients complete postgraduate training, the VHV scholarship program will provide an additional 12 veteran physicians to serve at VA for at least 4 years each (48 service years).

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

Fourteen applicants have been approved, including 5 in psychiatry, 4 in family medicine, 3 in internal medicine, 1 in emergency medicine, and 1 in geriatrics. The mean loan repayment is anticipated to be $110,000 and equating to 38.5 VA service years or a mean of 2.3 years of service obligation per individual for the first cohort. The program has no termination date, and with continued funding, VA anticipates granting 100 loan repayments annually.

Education Debt Reduction

Since 2018, 1,546 VA physicians have received EDRP awards. Due to the increased reimbursement provided through the MISSION Act, average physician award amounts have increased from $96,090 in 2018 to $142,557 in 2019 and $148,302 in 2020.

Conclusions

The VA physician scholarship and loan repayment programs outlined in the MISSION Act build on the success of existing federal scholarship programs by providing opportunities for physician trainees to alleviate educational debt and explore a VA health professions career.

Looking ahead, VA must focus on measuring the success of the MISSION scholarship and loan repayment programs by tracking rates of acceptance and student graduation, residency and fellowship completion, and placement in VA medical facilities—both for the service obligation and future employment. Ultimately, the total impact on VA staffing, especially at rural and underresourced sites, will determine the success of the MISSION programs.

1. VA Policy Memorandum #2. Policy in Association of Veterans’ Hospitals with Medical Schools. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 20, 1946. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf 2. Gilman SC, Chang BK, Zeiss RA, Dougherty MB, Marks WJ, Ludke DA, Cox M. “The academic mission of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” In: Praeger Handbook of Veterans’ Health: History, Challenges, Issues, and Developments. Praeger; 2012:53-82.

3. Office of Inspector General, Veterans Health Administration OIG Determination of VHA Occupational Staffing Shortages FY2020. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published September 23, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-20-01249-259.pdf

4. Hussey PS, Ringel J, et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(4). Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1165z2/RAND_RR1165z2.pdf

5. Lynch A, Best T, Gutierrez SC, Daily JA. What Should I Do With My Student Loans? A Proposed Strategy for Educational Debt Management. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):11-15. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00279.1

6. The Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972, PL 92-426. US Government Publishing Office. Published 1972. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg713.pdf

7. Armed Forces Health Professions Financial Assistance Programs, 10 USC § 105 (2006).

8. ‘‘VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018’’. H.R. 5674. 115th Congress; Report No. 115-671, Part 1. May 3, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr5674/BILLS-115hr5674rh.pdf

1. VA Policy Memorandum #2. Policy in Association of Veterans’ Hospitals with Medical Schools. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 20, 1946. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf 2. Gilman SC, Chang BK, Zeiss RA, Dougherty MB, Marks WJ, Ludke DA, Cox M. “The academic mission of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” In: Praeger Handbook of Veterans’ Health: History, Challenges, Issues, and Developments. Praeger; 2012:53-82.

3. Office of Inspector General, Veterans Health Administration OIG Determination of VHA Occupational Staffing Shortages FY2020. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published September 23, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-20-01249-259.pdf

4. Hussey PS, Ringel J, et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(4). Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1165z2/RAND_RR1165z2.pdf

5. Lynch A, Best T, Gutierrez SC, Daily JA. What Should I Do With My Student Loans? A Proposed Strategy for Educational Debt Management. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):11-15. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00279.1

6. The Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972, PL 92-426. US Government Publishing Office. Published 1972. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg713.pdf

7. Armed Forces Health Professions Financial Assistance Programs, 10 USC § 105 (2006).

8. ‘‘VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018’’. H.R. 5674. 115th Congress; Report No. 115-671, Part 1. May 3, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr5674/BILLS-115hr5674rh.pdf

Telescoping Stents to Maintain a 3-Way Patency of the Airway

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

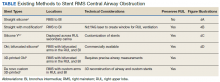

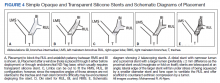

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

A Pioneer in Women’s Federal Practice

March is Women’s History Month. Many women have served in all branches of government health care over centuries and are worthy of celebrating. These nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and other allied health professionals devoted their time and talents, compassion, and competence to deliver and improve the care of wounded service members, disabled veterans, and the underresourced in our communities. To honor the collective contribution of women to federal practice in the Indian Health Service, Public Health Service Core, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the US Department of Defense, this column examines one pioneer in women’s federal practice—Margaret D. Craighill, MD—who epitomizes the spirit of the selfless dedication that generations of women have given to public service. Craighill is an ideal choice to represent this noble cadre of women as her career spanned active military duty, public health, and the Veterans Health Administration.

Craighill was a graduate of several of the finest institutions of medical training in the United States. Born in Southport, North Carolina, in 1898, she earned her undergraduate degree Phi Beta Kappa and master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin.2 She set her sights on becoming a physician at a period in American history when many prominent medical schools accepted few women. A marked exception—due to the fund raising and lobbying of influential women—was the prestigious Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.3 She graduated in 1924 and held a postgraduate position at Yale Medical School. She then worked as a physiologist at a military arsenal, a pathologist, a general surgeon, and completed a residency in obstetrics and gynecology. This broad training gave her the diverse expertise she would need for her future work.4

Craighill came from a military family: Her father was a colonel in the engineering corps, and her grandfather rose to become chief engineer of the Army.5 Along with many of America’s best and brightest, Craighill left her successful medical career as dean of the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania to join the war effort. Author Alan G. Knight points out, more than in civilian medicine, gender stereotypes kept women from entering the military: Women were expected and accepted as nurses, not doctors.5 But in 1943 Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed the Sparkman-Johnson Bill, enabling women to enter the then all-male Army and Navy Medical Corps. Craighill took advantage of this opportunity and accepted an appointment to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) as a major in 1943 at age 45 years, becoming the first woman physician to be commissioned an officer in the Army.

Major Craighill’s initial assignment was to the Office of the Surgeon General in the Preventive Medicine Division as the consultant for health and welfare of women. Here, she served as liaison to another innovation in women’s history in military medicine—the WAC. Journeying 56,000 miles to war zones in multiple countries, she assessed the health of 160,000 Army nurses and other staff whose focus was public health and infectious disease and hygiene. The history of women in medicine in and out of federal service is marked by overcoming innumerable biases and barriers. Craighill faced the prevailing presumption that women were unfit for military duty. In an early example of evidence-based medicine, she disproved this theory, showing that women were faring well doing hard jobs in tough environments.4

Their fortitude is more remarkable considering induction examinations for women during World War II were cursory and not tailored to address women’s health care needs. Based on her visits to WACs in theater and at home, Craighill observed recruits suffering from previously undiagnosed gynecologic and psychiatric conditions that adversely affected their health and function. She advocated for comprehensive standardized examinations that would detect many of these disorders.5

Craighill promoted other prejudices of her era. WAC command wanted to win public approval of women in the service and was concerned that lesbian relationships and “heterosexual promiscuity” would damage their public relations aims. They pressured Craighill to develop induction examinations that would screen lesbians and women with behavioral problems. She urged tolerance of homosexual behavior until it was proven.

Though clearly discriminatory and personally offensive to gay persons in federal service, we must recognize that only last year did the Pentagon move to overturn the prior administration’s prohibition against transgender persons serving in uniform.6 In this light Craighill, as the first female physician-leader in a 1940s military, adopted a relatively progressive stance.

Craighill rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and received the Legion of Merit award for her exemplary wartime service. In 1945, she earned another first when she was appointed to be a consultant on the medical care of women veterans. For women veterans, gaining access to newly earned benefits and receiving appropriate care were serious problems that Craighill worked to solve. For many women veterans, those challenges remain, and Craighill’s legacy summons us to take up the charge to empower women in federal health professions to enhance the quality of care women veterans receive in all sectors of US medicine.

Critics and advocates agree that the VA still has a long way to go to achieve equity and excellence in our care for women veterans.7,8 Craighill’s position stands as a landmark in this effort. During her VA tenure, Craighill entered a residency in the first class of the Menninger School of Psychiatry in Topeka, Kansas, and completed psychoanalytic training. Her wartime experiences had convinced her of the need to provide high-quality mental health care to women veterans. She put her new psychosomatic knowledge and skills to use, serving as the chief of a women’s health clinic at the VA Hospital in Topeka and published several important scholarly papers.5,9Craighill went on to have a distinguished career in academic medicine, underscoring the long and valuable relationship of US medicine and the scholarly medical community. Once her psychiatric training was finished, she returned to private practice, ending her career as chief psychiatrist at Connecticut College for Women.

Craighill made a significant contribution to the role of women in federal practice. She was a visionary in her conviction that women, whether physicians, nurses, or other health care professionals, had the gifts and the grit to serve with distinction and valor and that their military service entitled them in war and peace to gender-sensitive health care. As the epigraph for this editorial shows, Craighill knew the path for women in federal practice or service while not easy is well worth treading. Her pioneering career can inspire all those women who today and in the future choose to follow in her footsteps.

1. Bellafaire J, Graf MH. Women Doctors in War. Texas A&M University Press; 2009:61.

2. Nuland SB. Doctors: The Biography of Medicine. Alfred A. Knopf; 1988:399-405.

3. Dr. Margaret D. Craighill, at 78, former dean of medical college. Obituary. New York Times, July 26, 1977. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/1977/07/26/archives/dr-margaret-d-craighill-at-78-former-dean-of-medical-college.html