User login

For MD-IQ use only

Linear Vulvar Lesions

The Diagnosis: Vestibular Papillomatosis

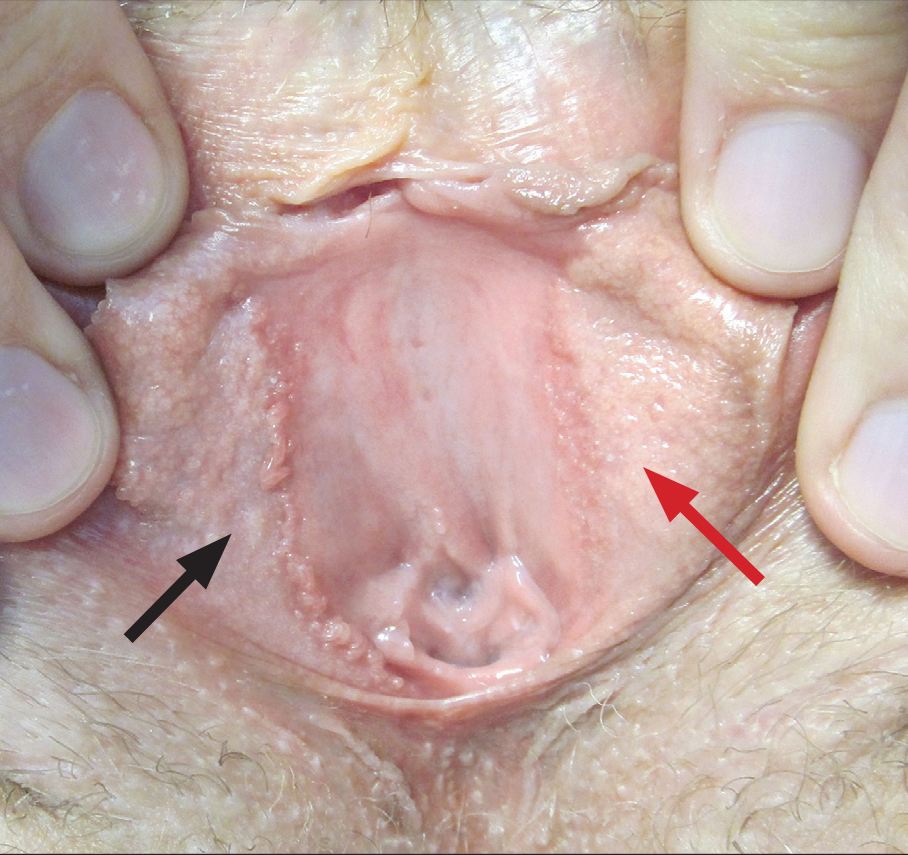

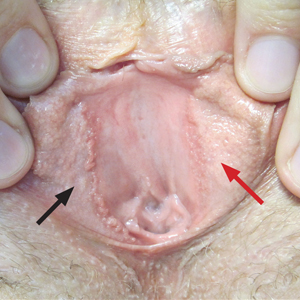

Vestibular papillomatosis (VP), the female equivalent of pearly penile papules, is characterized by multiple papules in a linear array on the labia minora and is considered a normal anatomic variant. It typically presents as monomorphous, soft, flesh-colored, filiform papules that are distributed in a symmetric fashion. In women, the papules present as linear arrays on the inner aspects of the labia minora, whereas in men, they present in a circumferential array along the sulcus of the glans penis.1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may cause itching, burning, and dyspareunia.2 Previously believed to be associated with human papillomavirus infection,3 VP is now considered a noninfectious condition. Biopsy reveals parakeratosis and perinuclear vacuolization in the absence of true koilocytes.4,5 Dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy have been used to differentiate VP from clinically similar lesions (eg, condyloma acuminatum).6,7 The prevalence of this condition is not well established; however, one study found VP in 1% of women attending genitourinary medicine clinics.3

Condyloma acuminatum, known colloquially as genital warts, is a human papillomavirus infection. Lesions tend to be painless and firm and are distributed asymmetrically with a cauliflowerlike appearance.1 Condyloma latum, found in secondary syphilis, is characterized by papules that are pale, smooth, flat topped, and moist.8 Molluscum contagiosum is an infection caused by a poxvirus presenting with flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules with central umbilication.9 The lesions of papulosquamous lichen planus are violaceous polygonal papules that affect the clitoral hood and labia minora and may cause pruritus. The cause of lichen planus is unknown; however, clinically similar lesions may occur in a lichenoid drug eruption due to certain medications.

Vestibular papillomatosis typically does not require treatment, except in symptomatic cases. To date, limited studies have reported variable treatment success utilizing destructive techniques such as CO2 laser or topical application of 5-fluorouracil or trichloroacetic acid.10

The lesions on our patient's left medial labia minora were successfully treated with low-voltage (3.0 V) electrodesiccation. Following local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine, each papule was gently electrodesiccated utilizing a standard hyfrecation electrode tip to a light gray discoloration. Postprocedural care involved only twice-daily cleansing with a gentle soap and application of petrolatum. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was satisfied with the cosmetic and functional results. She subsequently underwent treatment of the lesions on the right labia minora with equivalent treatment success.

- Moyal-Barracco M, Leibowitch M, Orth G. Vestibular papillae of the vulva. lack of evidence for human papillomavirus etiology. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1594-1598.

- Strand A, Wilander E, Zehbe I, et al. Vulvar papillomatosis, aceto-white lesions, and normal-looking vulvar mucosa evaluated by microscopy and human papillomavirus analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995;40:265-270.

- Welch JM, Nayagam M, Parry G, et al. What is vestibular papillomatosis? a study of its prevalence, aetiology and natural history. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:939-942.

- Wilkinson EJ, Guerrero E, Daniel R, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis is rarely associated with human papillomavirus infection types 6, 11, 16, or 18. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:344-349.

- Beznos G, Coates V, Focchi J, et al. Biomolecular study of the correlation between papillomatosis of the vulvar vestibule in adolescents and human papillomavirus. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:628-636.

- Kim SH, Seo SH, Ko HC, et al. The use of dermatoscopy to differentiate vestibular papillae, a normal variant of the female external genitalia, from condyloma acuminata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:353-355.

- Ozkur E, Falay T, Turgut Erdemir AV, et al. Vestibular papillomatosis: an important differential diagnosis of vulvar papillomas. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii:13030/qt7933q377

- Chang GJ, Welton ML. Human papillomavirus, condylomata acuminata, and anal neoplasia. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:221-230.

- Lynch PJ, Moyal-Barracco M, Bogliatto F, et al. 2006 ISSVD classification of vulvar dermatoses: pathologic subsets and their clinical correlates. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:3-9.

- Bergeron C, Ferenczy A, Richart RM, et al. Micropapillomatosis labialis appears unrelated to human papillomavirus. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:281-286.

The Diagnosis: Vestibular Papillomatosis

Vestibular papillomatosis (VP), the female equivalent of pearly penile papules, is characterized by multiple papules in a linear array on the labia minora and is considered a normal anatomic variant. It typically presents as monomorphous, soft, flesh-colored, filiform papules that are distributed in a symmetric fashion. In women, the papules present as linear arrays on the inner aspects of the labia minora, whereas in men, they present in a circumferential array along the sulcus of the glans penis.1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may cause itching, burning, and dyspareunia.2 Previously believed to be associated with human papillomavirus infection,3 VP is now considered a noninfectious condition. Biopsy reveals parakeratosis and perinuclear vacuolization in the absence of true koilocytes.4,5 Dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy have been used to differentiate VP from clinically similar lesions (eg, condyloma acuminatum).6,7 The prevalence of this condition is not well established; however, one study found VP in 1% of women attending genitourinary medicine clinics.3

Condyloma acuminatum, known colloquially as genital warts, is a human papillomavirus infection. Lesions tend to be painless and firm and are distributed asymmetrically with a cauliflowerlike appearance.1 Condyloma latum, found in secondary syphilis, is characterized by papules that are pale, smooth, flat topped, and moist.8 Molluscum contagiosum is an infection caused by a poxvirus presenting with flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules with central umbilication.9 The lesions of papulosquamous lichen planus are violaceous polygonal papules that affect the clitoral hood and labia minora and may cause pruritus. The cause of lichen planus is unknown; however, clinically similar lesions may occur in a lichenoid drug eruption due to certain medications.

Vestibular papillomatosis typically does not require treatment, except in symptomatic cases. To date, limited studies have reported variable treatment success utilizing destructive techniques such as CO2 laser or topical application of 5-fluorouracil or trichloroacetic acid.10

The lesions on our patient's left medial labia minora were successfully treated with low-voltage (3.0 V) electrodesiccation. Following local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine, each papule was gently electrodesiccated utilizing a standard hyfrecation electrode tip to a light gray discoloration. Postprocedural care involved only twice-daily cleansing with a gentle soap and application of petrolatum. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was satisfied with the cosmetic and functional results. She subsequently underwent treatment of the lesions on the right labia minora with equivalent treatment success.

The Diagnosis: Vestibular Papillomatosis

Vestibular papillomatosis (VP), the female equivalent of pearly penile papules, is characterized by multiple papules in a linear array on the labia minora and is considered a normal anatomic variant. It typically presents as monomorphous, soft, flesh-colored, filiform papules that are distributed in a symmetric fashion. In women, the papules present as linear arrays on the inner aspects of the labia minora, whereas in men, they present in a circumferential array along the sulcus of the glans penis.1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may cause itching, burning, and dyspareunia.2 Previously believed to be associated with human papillomavirus infection,3 VP is now considered a noninfectious condition. Biopsy reveals parakeratosis and perinuclear vacuolization in the absence of true koilocytes.4,5 Dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy have been used to differentiate VP from clinically similar lesions (eg, condyloma acuminatum).6,7 The prevalence of this condition is not well established; however, one study found VP in 1% of women attending genitourinary medicine clinics.3

Condyloma acuminatum, known colloquially as genital warts, is a human papillomavirus infection. Lesions tend to be painless and firm and are distributed asymmetrically with a cauliflowerlike appearance.1 Condyloma latum, found in secondary syphilis, is characterized by papules that are pale, smooth, flat topped, and moist.8 Molluscum contagiosum is an infection caused by a poxvirus presenting with flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules with central umbilication.9 The lesions of papulosquamous lichen planus are violaceous polygonal papules that affect the clitoral hood and labia minora and may cause pruritus. The cause of lichen planus is unknown; however, clinically similar lesions may occur in a lichenoid drug eruption due to certain medications.

Vestibular papillomatosis typically does not require treatment, except in symptomatic cases. To date, limited studies have reported variable treatment success utilizing destructive techniques such as CO2 laser or topical application of 5-fluorouracil or trichloroacetic acid.10

The lesions on our patient's left medial labia minora were successfully treated with low-voltage (3.0 V) electrodesiccation. Following local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine, each papule was gently electrodesiccated utilizing a standard hyfrecation electrode tip to a light gray discoloration. Postprocedural care involved only twice-daily cleansing with a gentle soap and application of petrolatum. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was satisfied with the cosmetic and functional results. She subsequently underwent treatment of the lesions on the right labia minora with equivalent treatment success.

- Moyal-Barracco M, Leibowitch M, Orth G. Vestibular papillae of the vulva. lack of evidence for human papillomavirus etiology. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1594-1598.

- Strand A, Wilander E, Zehbe I, et al. Vulvar papillomatosis, aceto-white lesions, and normal-looking vulvar mucosa evaluated by microscopy and human papillomavirus analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995;40:265-270.

- Welch JM, Nayagam M, Parry G, et al. What is vestibular papillomatosis? a study of its prevalence, aetiology and natural history. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:939-942.

- Wilkinson EJ, Guerrero E, Daniel R, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis is rarely associated with human papillomavirus infection types 6, 11, 16, or 18. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:344-349.

- Beznos G, Coates V, Focchi J, et al. Biomolecular study of the correlation between papillomatosis of the vulvar vestibule in adolescents and human papillomavirus. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:628-636.

- Kim SH, Seo SH, Ko HC, et al. The use of dermatoscopy to differentiate vestibular papillae, a normal variant of the female external genitalia, from condyloma acuminata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:353-355.

- Ozkur E, Falay T, Turgut Erdemir AV, et al. Vestibular papillomatosis: an important differential diagnosis of vulvar papillomas. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii:13030/qt7933q377

- Chang GJ, Welton ML. Human papillomavirus, condylomata acuminata, and anal neoplasia. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:221-230.

- Lynch PJ, Moyal-Barracco M, Bogliatto F, et al. 2006 ISSVD classification of vulvar dermatoses: pathologic subsets and their clinical correlates. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:3-9.

- Bergeron C, Ferenczy A, Richart RM, et al. Micropapillomatosis labialis appears unrelated to human papillomavirus. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:281-286.

- Moyal-Barracco M, Leibowitch M, Orth G. Vestibular papillae of the vulva. lack of evidence for human papillomavirus etiology. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1594-1598.

- Strand A, Wilander E, Zehbe I, et al. Vulvar papillomatosis, aceto-white lesions, and normal-looking vulvar mucosa evaluated by microscopy and human papillomavirus analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995;40:265-270.

- Welch JM, Nayagam M, Parry G, et al. What is vestibular papillomatosis? a study of its prevalence, aetiology and natural history. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:939-942.

- Wilkinson EJ, Guerrero E, Daniel R, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis is rarely associated with human papillomavirus infection types 6, 11, 16, or 18. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:344-349.

- Beznos G, Coates V, Focchi J, et al. Biomolecular study of the correlation between papillomatosis of the vulvar vestibule in adolescents and human papillomavirus. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:628-636.

- Kim SH, Seo SH, Ko HC, et al. The use of dermatoscopy to differentiate vestibular papillae, a normal variant of the female external genitalia, from condyloma acuminata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:353-355.

- Ozkur E, Falay T, Turgut Erdemir AV, et al. Vestibular papillomatosis: an important differential diagnosis of vulvar papillomas. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii:13030/qt7933q377

- Chang GJ, Welton ML. Human papillomavirus, condylomata acuminata, and anal neoplasia. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:221-230.

- Lynch PJ, Moyal-Barracco M, Bogliatto F, et al. 2006 ISSVD classification of vulvar dermatoses: pathologic subsets and their clinical correlates. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:3-9.

- Bergeron C, Ferenczy A, Richart RM, et al. Micropapillomatosis labialis appears unrelated to human papillomavirus. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:281-286.

A 30-year-old woman with congenital absence of the uterus presented to dermatology for a second opinion of vulvar lesions that were first noted during adolescence. The patient reported that the lesions had not changed and were painful during sexual intercourse. The lesions were otherwise asymptomatic, and she had no additional relevant medical history or family history of similar lesions. She denied any history of sexually transmitted infections. Physical examination revealed multiple, soft, flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm, discrete and coalescing, filiform papules distributed symmetrically in a linear array on the inner aspect of the bilateral medial labia minora. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination was normal.

The lesions on the left medial labia minora were treated with low-voltage (3.0 V) electrodesiccation following local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine (red arrow), while the lesions on the right medial labia minora were left untreated (black arrow). The clinical image shows the left labia minora approximately 1 month after treatment; the papules on the right labia minora were unchanged from the prior examination.

Gone But Not Forgotten: How VA Remembers

Caring for veterans at the end of their lives is a great honor. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care professionals (HCPs) find meaning and take pride in providing this care. We are there to support the patient and their family and loved ones around the time of death. When our patients die, we feel the loss and grieve as well. VA health care providers look to our teams to set up rituals that pay tribute to the veteran and to show respect and gratitude for our role in these moments. It is important to recognize the bonds we share and the grief we feel when a veteran dies. The relationships we form, the recognition of loss, and the honoring of the veterans help nourish and maintain us.

Although the number of VA inpatient deaths nationwide has been declining steadily for years, internal reporting by the Palliative and Hospice Care Program Office has shown that the percentage of VA inpatient deaths that occur in hospice settings has steadily grown. Since 2013, more veterans die in VA inpatient hospice beds than in any other hospital setting. Therefore, it is useful to take stock of the way hospice and palliative care providers and staff process and provide support so that they can continue to provide service to veterans.

In the same way that all loss and grief are unique, there are many diverse rituals across VA facilities. This article highlights some of the unique traditions that hospice and palliative care teams have adopted to embrace this remembrance. We hope that by sharing these practices others will be inspired to find ways to reflect on their work and honor the lives of veterans.

The authors reached out to VA palliative care colleagues across the country via the Veterans Health Administration National Hospice and Palliative Care listserve to ask: How does your team practice remembrance? Palliative care providers responded and shared the unique ways they and their teams reflect on these losses.

There are many moments for reflection from the time of death to the weeks and months after, to the entire year of cumulative loss. Some observances start around the time of death. Susan MacDonald, RN, GEC, from Erie VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Pennsylvania reported that following the death of a veteran in the hospice unit, there is a bedside remembrance that includes the chaplain, care team, family, and other loved ones. At the John D. Dingell VAMC in Detroit, Michigan, the clinical chaplain leads a memorial service after a community living center (CLC) resident dies.

Several VAMCs, such as Detroit and Erie, have an Honors Escort or Final Salute. In these ceremonies, family, employees, residents, and other veterans line the hallways to honor the veteran on their departure from the building.1 At the VA Maine Healthcare System, Kate MacFawn, nurse manager, Inpatient Hospice Unit, explained, “We debrief every death the day after it occurs. The doc[tor]s check in with the nursing staff on each shift, and the rest of the multidisciplinary team discusses [it] in our morning report.”

Palliative care providers consider the physical spaces where the veteran has spent those last moments and the void that is left. Karen Pickler, staff chaplain at Northport VAMC Hospice Unit recounts:

At the time of death, we decorate the tray table with the veteran’s picture, a flag, and an angel. In the CLC they will have a memorial service on Friday if a resident has died that week. This is for the unit and staff. In the past, other residents were not informed of the death. This way, the relationships between residents are honored as well as their natural families.

At VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts in the Inpatient Hospice Unit-CLC, after a veteran dies, a flag, a strand of lights, and a rose in a vase are placed outside the veteran’s room to mark the absence. The VABHS remembrance practice has evolved over time based on input from the team. According to Noah Whiddon, LICSW, CLC complex case coordinator, at a weekly interdisciplinary team (IDT) meeting, the names of veterans who have died in the past week are read, and there is a commemorative ribbon cutting. “Any team member may write the last name of the deceased veteran on the ribbon and place it into a vase,” he said. “One of the nurse team members felt that a moment of silence would be appropriate, and we have added that.”

Every 6 months, VABHS holds a flag burning ceremony to appropriately dispose of worn out flags. Veterans and families are invited. The commemorative ribbons are packaged and burned at this ceremony with the following explanation of the ritual:

We’d like to take a moment to reflect on the lives of veterans we’ve lost in the last 6 months. Each week we remember the veterans for whom we have cared who have passed away. As part of this, we cut a ribbon and inscribe their name on it to commemorate their memory. We might have known these veterans for a few days or for a few years, but each of their lives had meaning for us. The courage that our veterans demonstrate at the end of their lives is an extension of the bravery they displayed in their service to our country. Today we will burn their commemorative ribbons with our country’s flag in tribute to and respect for their selflessness to our country. Please join us in a few moments of silence as their ribbons burn together with our flag.

In the VABHS acute care hospital, the palliative care IDT reserves 30 minutes, twice monthly for a chaplain-led remembrance. A large bowl-shaped shell is placed in the center of the table with smaller shells around it. Any team member can read the names of veterans who have died in prior weeks and share a memory of the patient or family, and then place a smaller shell into the larger bowl. This represents the transition from the smallest part of the universe back into the larger part. At the end, a moment of silence is observed or a poem is read. This tradition was brought to the team by the palliative care chaplain, Douglas Falls, MDiv.

Bimonthly bereavement meetings are held at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital-Pasco County branch, and each veteran who has died is remembered. Whoever wants to share is welcome. “We conclude with a poem, usually shared by the physician, but it can be any team member,” explained Linda Falzetta-Gross, ARNP-BC. “This process is led by the team social worker. In the past, we used to ring a bell prior to each name.”

Bells also are used at the Greater West Los Angeles VAMC in California. At the weekly clinic, veterans who have died are remembered, and each team member has an opportunity to share memories. “We ring a Tibetan bell for a moment without words,” explains Geoffrey Tyrell, palliative care chaplain. “It is introduced with a few words to allow new staff members in our clinic to participate, as a moment of mindfulness to let go of our words and to go inside, to see what we might need for our own wellness.” Afterward the chaplain says a few words and wishes for peace for the veterans and their families. The team also has responded well to more participatory group activities, such as placing rocks in a bowl of water, to symbolize letting go of something that has been difficult.

Additionally, there are practices of a larger scope. Many VAMCs have established facility-wide memorial services annually, biannually, or quarterly. At this time, families and staff come together to remember and honor veterans who have died within the VAMC. These memorials might involve a variety of service lines, such as chaplaincy, voluntary services, nursing, and social work and may consist of an honor guard, music, and readings. In accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and privacy regulations, only family members of deceased veterans may speak the names at the ceremony unless written consent is given. At the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, family members may stand and give the name of the person they are honoring. Balloons are released, stories are told, and a poem or appropriate passage is read. Families are given a book pinned with a flag, according to Jennifer C. Crenshaw, clinical staff chaplain. Family members are moved knowing that the VA remembers their loved ones even months after they are gone.

Due to the overwhelming positive feedback from veterans’ families who participated in these ceremonies, on January 24, 2018, Carolyn Clancy, MD, VHA Executive-in-Charge, Office of the Under Secretary for Health issued a memorandum requesting that all VAMCs immediately adopt this best practice: to host periodic ceremonies to publicly recognize and honor deceased veterans in the presence of their families, VA care providers, veterans service organizations and community members. Clancy recommended calling the ceremonies “The Last Roll Call Ceremony of Remembrance.”2

These rituals are a small sample of the rich diversity of practice in VAs across the country. What unifies VA palliative care providers is our mission to serve the veterans, honor their deaths, show respect and gratitude, and recognize that we, too, feel the pain of loss. We mark these moments with solemnity and beauty—a bell, a poem, a prayer—to honor our shared experience caring for veterans.

1. Saint S. A VA hospital you may not know: The Final Salute, and how much we doctors care. https://theconversation.com/a-va-hospital-you-may-not-know-the-final-salute-and-how-much-we-doctors-care-94217. Published March 30, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2019.

2. Clancy CM. VAIQ Memorandum 7866347: Implementation of the last roll call ceremony of remembrance at all Veterans Affairs medical centers. Published 2018.

Caring for veterans at the end of their lives is a great honor. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care professionals (HCPs) find meaning and take pride in providing this care. We are there to support the patient and their family and loved ones around the time of death. When our patients die, we feel the loss and grieve as well. VA health care providers look to our teams to set up rituals that pay tribute to the veteran and to show respect and gratitude for our role in these moments. It is important to recognize the bonds we share and the grief we feel when a veteran dies. The relationships we form, the recognition of loss, and the honoring of the veterans help nourish and maintain us.

Although the number of VA inpatient deaths nationwide has been declining steadily for years, internal reporting by the Palliative and Hospice Care Program Office has shown that the percentage of VA inpatient deaths that occur in hospice settings has steadily grown. Since 2013, more veterans die in VA inpatient hospice beds than in any other hospital setting. Therefore, it is useful to take stock of the way hospice and palliative care providers and staff process and provide support so that they can continue to provide service to veterans.

In the same way that all loss and grief are unique, there are many diverse rituals across VA facilities. This article highlights some of the unique traditions that hospice and palliative care teams have adopted to embrace this remembrance. We hope that by sharing these practices others will be inspired to find ways to reflect on their work and honor the lives of veterans.

The authors reached out to VA palliative care colleagues across the country via the Veterans Health Administration National Hospice and Palliative Care listserve to ask: How does your team practice remembrance? Palliative care providers responded and shared the unique ways they and their teams reflect on these losses.

There are many moments for reflection from the time of death to the weeks and months after, to the entire year of cumulative loss. Some observances start around the time of death. Susan MacDonald, RN, GEC, from Erie VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Pennsylvania reported that following the death of a veteran in the hospice unit, there is a bedside remembrance that includes the chaplain, care team, family, and other loved ones. At the John D. Dingell VAMC in Detroit, Michigan, the clinical chaplain leads a memorial service after a community living center (CLC) resident dies.

Several VAMCs, such as Detroit and Erie, have an Honors Escort or Final Salute. In these ceremonies, family, employees, residents, and other veterans line the hallways to honor the veteran on their departure from the building.1 At the VA Maine Healthcare System, Kate MacFawn, nurse manager, Inpatient Hospice Unit, explained, “We debrief every death the day after it occurs. The doc[tor]s check in with the nursing staff on each shift, and the rest of the multidisciplinary team discusses [it] in our morning report.”

Palliative care providers consider the physical spaces where the veteran has spent those last moments and the void that is left. Karen Pickler, staff chaplain at Northport VAMC Hospice Unit recounts:

At the time of death, we decorate the tray table with the veteran’s picture, a flag, and an angel. In the CLC they will have a memorial service on Friday if a resident has died that week. This is for the unit and staff. In the past, other residents were not informed of the death. This way, the relationships between residents are honored as well as their natural families.

At VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts in the Inpatient Hospice Unit-CLC, after a veteran dies, a flag, a strand of lights, and a rose in a vase are placed outside the veteran’s room to mark the absence. The VABHS remembrance practice has evolved over time based on input from the team. According to Noah Whiddon, LICSW, CLC complex case coordinator, at a weekly interdisciplinary team (IDT) meeting, the names of veterans who have died in the past week are read, and there is a commemorative ribbon cutting. “Any team member may write the last name of the deceased veteran on the ribbon and place it into a vase,” he said. “One of the nurse team members felt that a moment of silence would be appropriate, and we have added that.”

Every 6 months, VABHS holds a flag burning ceremony to appropriately dispose of worn out flags. Veterans and families are invited. The commemorative ribbons are packaged and burned at this ceremony with the following explanation of the ritual:

We’d like to take a moment to reflect on the lives of veterans we’ve lost in the last 6 months. Each week we remember the veterans for whom we have cared who have passed away. As part of this, we cut a ribbon and inscribe their name on it to commemorate their memory. We might have known these veterans for a few days or for a few years, but each of their lives had meaning for us. The courage that our veterans demonstrate at the end of their lives is an extension of the bravery they displayed in their service to our country. Today we will burn their commemorative ribbons with our country’s flag in tribute to and respect for their selflessness to our country. Please join us in a few moments of silence as their ribbons burn together with our flag.

In the VABHS acute care hospital, the palliative care IDT reserves 30 minutes, twice monthly for a chaplain-led remembrance. A large bowl-shaped shell is placed in the center of the table with smaller shells around it. Any team member can read the names of veterans who have died in prior weeks and share a memory of the patient or family, and then place a smaller shell into the larger bowl. This represents the transition from the smallest part of the universe back into the larger part. At the end, a moment of silence is observed or a poem is read. This tradition was brought to the team by the palliative care chaplain, Douglas Falls, MDiv.

Bimonthly bereavement meetings are held at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital-Pasco County branch, and each veteran who has died is remembered. Whoever wants to share is welcome. “We conclude with a poem, usually shared by the physician, but it can be any team member,” explained Linda Falzetta-Gross, ARNP-BC. “This process is led by the team social worker. In the past, we used to ring a bell prior to each name.”

Bells also are used at the Greater West Los Angeles VAMC in California. At the weekly clinic, veterans who have died are remembered, and each team member has an opportunity to share memories. “We ring a Tibetan bell for a moment without words,” explains Geoffrey Tyrell, palliative care chaplain. “It is introduced with a few words to allow new staff members in our clinic to participate, as a moment of mindfulness to let go of our words and to go inside, to see what we might need for our own wellness.” Afterward the chaplain says a few words and wishes for peace for the veterans and their families. The team also has responded well to more participatory group activities, such as placing rocks in a bowl of water, to symbolize letting go of something that has been difficult.

Additionally, there are practices of a larger scope. Many VAMCs have established facility-wide memorial services annually, biannually, or quarterly. At this time, families and staff come together to remember and honor veterans who have died within the VAMC. These memorials might involve a variety of service lines, such as chaplaincy, voluntary services, nursing, and social work and may consist of an honor guard, music, and readings. In accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and privacy regulations, only family members of deceased veterans may speak the names at the ceremony unless written consent is given. At the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, family members may stand and give the name of the person they are honoring. Balloons are released, stories are told, and a poem or appropriate passage is read. Families are given a book pinned with a flag, according to Jennifer C. Crenshaw, clinical staff chaplain. Family members are moved knowing that the VA remembers their loved ones even months after they are gone.

Due to the overwhelming positive feedback from veterans’ families who participated in these ceremonies, on January 24, 2018, Carolyn Clancy, MD, VHA Executive-in-Charge, Office of the Under Secretary for Health issued a memorandum requesting that all VAMCs immediately adopt this best practice: to host periodic ceremonies to publicly recognize and honor deceased veterans in the presence of their families, VA care providers, veterans service organizations and community members. Clancy recommended calling the ceremonies “The Last Roll Call Ceremony of Remembrance.”2

These rituals are a small sample of the rich diversity of practice in VAs across the country. What unifies VA palliative care providers is our mission to serve the veterans, honor their deaths, show respect and gratitude, and recognize that we, too, feel the pain of loss. We mark these moments with solemnity and beauty—a bell, a poem, a prayer—to honor our shared experience caring for veterans.

Caring for veterans at the end of their lives is a great honor. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care professionals (HCPs) find meaning and take pride in providing this care. We are there to support the patient and their family and loved ones around the time of death. When our patients die, we feel the loss and grieve as well. VA health care providers look to our teams to set up rituals that pay tribute to the veteran and to show respect and gratitude for our role in these moments. It is important to recognize the bonds we share and the grief we feel when a veteran dies. The relationships we form, the recognition of loss, and the honoring of the veterans help nourish and maintain us.

Although the number of VA inpatient deaths nationwide has been declining steadily for years, internal reporting by the Palliative and Hospice Care Program Office has shown that the percentage of VA inpatient deaths that occur in hospice settings has steadily grown. Since 2013, more veterans die in VA inpatient hospice beds than in any other hospital setting. Therefore, it is useful to take stock of the way hospice and palliative care providers and staff process and provide support so that they can continue to provide service to veterans.

In the same way that all loss and grief are unique, there are many diverse rituals across VA facilities. This article highlights some of the unique traditions that hospice and palliative care teams have adopted to embrace this remembrance. We hope that by sharing these practices others will be inspired to find ways to reflect on their work and honor the lives of veterans.

The authors reached out to VA palliative care colleagues across the country via the Veterans Health Administration National Hospice and Palliative Care listserve to ask: How does your team practice remembrance? Palliative care providers responded and shared the unique ways they and their teams reflect on these losses.

There are many moments for reflection from the time of death to the weeks and months after, to the entire year of cumulative loss. Some observances start around the time of death. Susan MacDonald, RN, GEC, from Erie VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Pennsylvania reported that following the death of a veteran in the hospice unit, there is a bedside remembrance that includes the chaplain, care team, family, and other loved ones. At the John D. Dingell VAMC in Detroit, Michigan, the clinical chaplain leads a memorial service after a community living center (CLC) resident dies.

Several VAMCs, such as Detroit and Erie, have an Honors Escort or Final Salute. In these ceremonies, family, employees, residents, and other veterans line the hallways to honor the veteran on their departure from the building.1 At the VA Maine Healthcare System, Kate MacFawn, nurse manager, Inpatient Hospice Unit, explained, “We debrief every death the day after it occurs. The doc[tor]s check in with the nursing staff on each shift, and the rest of the multidisciplinary team discusses [it] in our morning report.”

Palliative care providers consider the physical spaces where the veteran has spent those last moments and the void that is left. Karen Pickler, staff chaplain at Northport VAMC Hospice Unit recounts:

At the time of death, we decorate the tray table with the veteran’s picture, a flag, and an angel. In the CLC they will have a memorial service on Friday if a resident has died that week. This is for the unit and staff. In the past, other residents were not informed of the death. This way, the relationships between residents are honored as well as their natural families.

At VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts in the Inpatient Hospice Unit-CLC, after a veteran dies, a flag, a strand of lights, and a rose in a vase are placed outside the veteran’s room to mark the absence. The VABHS remembrance practice has evolved over time based on input from the team. According to Noah Whiddon, LICSW, CLC complex case coordinator, at a weekly interdisciplinary team (IDT) meeting, the names of veterans who have died in the past week are read, and there is a commemorative ribbon cutting. “Any team member may write the last name of the deceased veteran on the ribbon and place it into a vase,” he said. “One of the nurse team members felt that a moment of silence would be appropriate, and we have added that.”

Every 6 months, VABHS holds a flag burning ceremony to appropriately dispose of worn out flags. Veterans and families are invited. The commemorative ribbons are packaged and burned at this ceremony with the following explanation of the ritual:

We’d like to take a moment to reflect on the lives of veterans we’ve lost in the last 6 months. Each week we remember the veterans for whom we have cared who have passed away. As part of this, we cut a ribbon and inscribe their name on it to commemorate their memory. We might have known these veterans for a few days or for a few years, but each of their lives had meaning for us. The courage that our veterans demonstrate at the end of their lives is an extension of the bravery they displayed in their service to our country. Today we will burn their commemorative ribbons with our country’s flag in tribute to and respect for their selflessness to our country. Please join us in a few moments of silence as their ribbons burn together with our flag.

In the VABHS acute care hospital, the palliative care IDT reserves 30 minutes, twice monthly for a chaplain-led remembrance. A large bowl-shaped shell is placed in the center of the table with smaller shells around it. Any team member can read the names of veterans who have died in prior weeks and share a memory of the patient or family, and then place a smaller shell into the larger bowl. This represents the transition from the smallest part of the universe back into the larger part. At the end, a moment of silence is observed or a poem is read. This tradition was brought to the team by the palliative care chaplain, Douglas Falls, MDiv.

Bimonthly bereavement meetings are held at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital-Pasco County branch, and each veteran who has died is remembered. Whoever wants to share is welcome. “We conclude with a poem, usually shared by the physician, but it can be any team member,” explained Linda Falzetta-Gross, ARNP-BC. “This process is led by the team social worker. In the past, we used to ring a bell prior to each name.”

Bells also are used at the Greater West Los Angeles VAMC in California. At the weekly clinic, veterans who have died are remembered, and each team member has an opportunity to share memories. “We ring a Tibetan bell for a moment without words,” explains Geoffrey Tyrell, palliative care chaplain. “It is introduced with a few words to allow new staff members in our clinic to participate, as a moment of mindfulness to let go of our words and to go inside, to see what we might need for our own wellness.” Afterward the chaplain says a few words and wishes for peace for the veterans and their families. The team also has responded well to more participatory group activities, such as placing rocks in a bowl of water, to symbolize letting go of something that has been difficult.

Additionally, there are practices of a larger scope. Many VAMCs have established facility-wide memorial services annually, biannually, or quarterly. At this time, families and staff come together to remember and honor veterans who have died within the VAMC. These memorials might involve a variety of service lines, such as chaplaincy, voluntary services, nursing, and social work and may consist of an honor guard, music, and readings. In accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and privacy regulations, only family members of deceased veterans may speak the names at the ceremony unless written consent is given. At the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, family members may stand and give the name of the person they are honoring. Balloons are released, stories are told, and a poem or appropriate passage is read. Families are given a book pinned with a flag, according to Jennifer C. Crenshaw, clinical staff chaplain. Family members are moved knowing that the VA remembers their loved ones even months after they are gone.

Due to the overwhelming positive feedback from veterans’ families who participated in these ceremonies, on January 24, 2018, Carolyn Clancy, MD, VHA Executive-in-Charge, Office of the Under Secretary for Health issued a memorandum requesting that all VAMCs immediately adopt this best practice: to host periodic ceremonies to publicly recognize and honor deceased veterans in the presence of their families, VA care providers, veterans service organizations and community members. Clancy recommended calling the ceremonies “The Last Roll Call Ceremony of Remembrance.”2

These rituals are a small sample of the rich diversity of practice in VAs across the country. What unifies VA palliative care providers is our mission to serve the veterans, honor their deaths, show respect and gratitude, and recognize that we, too, feel the pain of loss. We mark these moments with solemnity and beauty—a bell, a poem, a prayer—to honor our shared experience caring for veterans.

1. Saint S. A VA hospital you may not know: The Final Salute, and how much we doctors care. https://theconversation.com/a-va-hospital-you-may-not-know-the-final-salute-and-how-much-we-doctors-care-94217. Published March 30, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2019.

2. Clancy CM. VAIQ Memorandum 7866347: Implementation of the last roll call ceremony of remembrance at all Veterans Affairs medical centers. Published 2018.

1. Saint S. A VA hospital you may not know: The Final Salute, and how much we doctors care. https://theconversation.com/a-va-hospital-you-may-not-know-the-final-salute-and-how-much-we-doctors-care-94217. Published March 30, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2019.

2. Clancy CM. VAIQ Memorandum 7866347: Implementation of the last roll call ceremony of remembrance at all Veterans Affairs medical centers. Published 2018.

GI practice consolidation continues

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2019 is now history. This was the 50th anniversary of DDW and again, it lived up to its reputation as the world’s foremost meeting dedicated to digestive diseases. GI & Hepatology News will publish multiple articles highlighting the best of DDW in the coming months.

The AGA Presidential Plenary session is an annual DDW highlight. This year’s session did not disappoint and was attended by a large crowd. David Lieberman, MD, AGAF (outgoing AGA president) and Hashem B. El-Serag MD, MPH, AGAF (incoming AGA president) moderated the session. Outstanding presentations about management of obesity, new findings in IBD, the use of virtual reality in the treatment of functional abdominal pain, and findings from a long-term colorectal cancer screening trial were some of the key presentations.

Recent behind-the-scenes work by the AGA is paying off for its members and the larger GI community. The AGA was again awarded an NIH-funded grant to advance its education and training of under-represented minorities. This is the second NIH grant given to the AGA, who now has become a leader in diversity and inclusive education. The AGA has strengthened its close bond with the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation, adding to its portfolio of scientific and clinical offerings focused on IBD. The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education has emerged as one of the best sources of education and research about the microbiome’s impact on digestive health.

On the business front, there are tectonic changes occurring. In 2018, three large GI practices were sold to private equity companies and each has completed multiple arbitrage plays (acquisition of smaller practices), growing to over 200 physicians. This year we will see 6-10 additional private equity acquisitions and will likely see one or more GI practices of 500-1000 providers. This consolidation will have profound implications for the practice of gastroenterology and will provide some interesting opportunities to conduct population-based research for physicians who can capture that potential through academic-community partnerships.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2019 is now history. This was the 50th anniversary of DDW and again, it lived up to its reputation as the world’s foremost meeting dedicated to digestive diseases. GI & Hepatology News will publish multiple articles highlighting the best of DDW in the coming months.

The AGA Presidential Plenary session is an annual DDW highlight. This year’s session did not disappoint and was attended by a large crowd. David Lieberman, MD, AGAF (outgoing AGA president) and Hashem B. El-Serag MD, MPH, AGAF (incoming AGA president) moderated the session. Outstanding presentations about management of obesity, new findings in IBD, the use of virtual reality in the treatment of functional abdominal pain, and findings from a long-term colorectal cancer screening trial were some of the key presentations.

Recent behind-the-scenes work by the AGA is paying off for its members and the larger GI community. The AGA was again awarded an NIH-funded grant to advance its education and training of under-represented minorities. This is the second NIH grant given to the AGA, who now has become a leader in diversity and inclusive education. The AGA has strengthened its close bond with the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation, adding to its portfolio of scientific and clinical offerings focused on IBD. The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education has emerged as one of the best sources of education and research about the microbiome’s impact on digestive health.

On the business front, there are tectonic changes occurring. In 2018, three large GI practices were sold to private equity companies and each has completed multiple arbitrage plays (acquisition of smaller practices), growing to over 200 physicians. This year we will see 6-10 additional private equity acquisitions and will likely see one or more GI practices of 500-1000 providers. This consolidation will have profound implications for the practice of gastroenterology and will provide some interesting opportunities to conduct population-based research for physicians who can capture that potential through academic-community partnerships.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2019 is now history. This was the 50th anniversary of DDW and again, it lived up to its reputation as the world’s foremost meeting dedicated to digestive diseases. GI & Hepatology News will publish multiple articles highlighting the best of DDW in the coming months.

The AGA Presidential Plenary session is an annual DDW highlight. This year’s session did not disappoint and was attended by a large crowd. David Lieberman, MD, AGAF (outgoing AGA president) and Hashem B. El-Serag MD, MPH, AGAF (incoming AGA president) moderated the session. Outstanding presentations about management of obesity, new findings in IBD, the use of virtual reality in the treatment of functional abdominal pain, and findings from a long-term colorectal cancer screening trial were some of the key presentations.

Recent behind-the-scenes work by the AGA is paying off for its members and the larger GI community. The AGA was again awarded an NIH-funded grant to advance its education and training of under-represented minorities. This is the second NIH grant given to the AGA, who now has become a leader in diversity and inclusive education. The AGA has strengthened its close bond with the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation, adding to its portfolio of scientific and clinical offerings focused on IBD. The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education has emerged as one of the best sources of education and research about the microbiome’s impact on digestive health.

On the business front, there are tectonic changes occurring. In 2018, three large GI practices were sold to private equity companies and each has completed multiple arbitrage plays (acquisition of smaller practices), growing to over 200 physicians. This year we will see 6-10 additional private equity acquisitions and will likely see one or more GI practices of 500-1000 providers. This consolidation will have profound implications for the practice of gastroenterology and will provide some interesting opportunities to conduct population-based research for physicians who can capture that potential through academic-community partnerships.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Steroids May Not Benefit Patients With Mild Asthma

The gold-standard treatment is no more effective than placebo for patients with mild persistent asthma, say researchers from the Steroids in Eosinophil Negative Asthma (SIENA) study, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The researchers divided 295 participants into groups based on low- or high-sputum eosinophil levels and assigned them randomly to each of 3 treatment groups for 12-week periods: inhaled steroids (mometasone), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (tiotropium), or placebo.

Surprisingly, 221 participants—nearly 73%—were classified as having low-sputum eosinophils (< 2%), a much higher frequency than the researchers expected. And of those, the number who responded better to steroids was no different from the number responding to placebo. Of the Eos-low group, 60% had better symptom control with LAMA; 40% had better symptom control with placebo.

By contrast, patients classified as “Eos-high” were nearly 3 times as likely to respond to inhaled steroids compared with placebo.

Other research has indicated that about half the population with mild persistent asthma have < 2% sputum eosinophils and are not likely to respond well to steroids. But laboratory tests to measure sputum eosinophils are not routinely used in most clinics, the researchers say.

The difference between the groups is not large enough to conclude that patients are more likely to do better on LAMA drugs, the researchers say, but their study highlights the need to look for alternatives to inhaled steroids for patients with mild asthma.

The research underscores the value of customizing treatments to help people with asthma, said James Kiley, PhD, director of the Division of Lung Diseases at NHLBI. “This study adds to a growing body of evidence that different patients with mild asthma should be treated differently, perhaps using biomarkers like sputum eosinophils to select which drugs should be used—a precision medicine approach.”

The gold-standard treatment is no more effective than placebo for patients with mild persistent asthma, say researchers from the Steroids in Eosinophil Negative Asthma (SIENA) study, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The researchers divided 295 participants into groups based on low- or high-sputum eosinophil levels and assigned them randomly to each of 3 treatment groups for 12-week periods: inhaled steroids (mometasone), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (tiotropium), or placebo.

Surprisingly, 221 participants—nearly 73%—were classified as having low-sputum eosinophils (< 2%), a much higher frequency than the researchers expected. And of those, the number who responded better to steroids was no different from the number responding to placebo. Of the Eos-low group, 60% had better symptom control with LAMA; 40% had better symptom control with placebo.

By contrast, patients classified as “Eos-high” were nearly 3 times as likely to respond to inhaled steroids compared with placebo.

Other research has indicated that about half the population with mild persistent asthma have < 2% sputum eosinophils and are not likely to respond well to steroids. But laboratory tests to measure sputum eosinophils are not routinely used in most clinics, the researchers say.

The difference between the groups is not large enough to conclude that patients are more likely to do better on LAMA drugs, the researchers say, but their study highlights the need to look for alternatives to inhaled steroids for patients with mild asthma.

The research underscores the value of customizing treatments to help people with asthma, said James Kiley, PhD, director of the Division of Lung Diseases at NHLBI. “This study adds to a growing body of evidence that different patients with mild asthma should be treated differently, perhaps using biomarkers like sputum eosinophils to select which drugs should be used—a precision medicine approach.”

The gold-standard treatment is no more effective than placebo for patients with mild persistent asthma, say researchers from the Steroids in Eosinophil Negative Asthma (SIENA) study, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The researchers divided 295 participants into groups based on low- or high-sputum eosinophil levels and assigned them randomly to each of 3 treatment groups for 12-week periods: inhaled steroids (mometasone), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (tiotropium), or placebo.

Surprisingly, 221 participants—nearly 73%—were classified as having low-sputum eosinophils (< 2%), a much higher frequency than the researchers expected. And of those, the number who responded better to steroids was no different from the number responding to placebo. Of the Eos-low group, 60% had better symptom control with LAMA; 40% had better symptom control with placebo.

By contrast, patients classified as “Eos-high” were nearly 3 times as likely to respond to inhaled steroids compared with placebo.

Other research has indicated that about half the population with mild persistent asthma have < 2% sputum eosinophils and are not likely to respond well to steroids. But laboratory tests to measure sputum eosinophils are not routinely used in most clinics, the researchers say.

The difference between the groups is not large enough to conclude that patients are more likely to do better on LAMA drugs, the researchers say, but their study highlights the need to look for alternatives to inhaled steroids for patients with mild asthma.

The research underscores the value of customizing treatments to help people with asthma, said James Kiley, PhD, director of the Division of Lung Diseases at NHLBI. “This study adds to a growing body of evidence that different patients with mild asthma should be treated differently, perhaps using biomarkers like sputum eosinophils to select which drugs should be used—a precision medicine approach.”

SPIRITT: What does ‘spirituality’ mean?

Both patients and clinicians alike have shown increasing interest in spirituality as a component of physical and mental well-being.1 However, there’s no clear consensus on what spirituality actually means. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it “affecting the spirit, relating to sacred matters, concerned with religious issues.”2 Spirituality is sometimes defined in broadly secular terms, such as the feeling of “being part of something greater than ourselves,” or in connection to ideas rooted in a specific belief system, such as “aligning oneself with the Will of God.”

I prefer to think of the word “spiritual” as encompassing multiple practices and beliefs that have the common goal of helping us deepen our capacity for self-awareness, joy, compassion, love, freedom, justice, and mutual cooperation, not only for our own benefit, but also to create a better world. To help clinicians better understand what the term spirituality implies, whether for themselves or for their patients, I offer the acronym SPIRITT to describe core components of varied spiritual perspectives, beliefs, and practices.

Sacred. Considering certain aspects of life, time, or place as non-ordinary and worthy of reverence and awe.

Presence. Cultivating an inner presence that is open, accepting, compassionate, and loving toward others. During a spiritual experience, some may feel embraced in this way by a presence outside of themselves, such as an encounter with a spiritual teacher or an experience of feeling held lovingly by a transcendent power.

Interconnection. Understanding that we are not separate entities but are interconnected beings existing in interdependent unity, starting with our families and extending out universally. According to this perspective, harming anything or anyone is doing harm to ourself.

Rest. Taking a Sabbath or unplugging. Dedicating time each week for resting your mind and body. Spending quality time with family. Decreasing excessive stimulation and loosening the grip of consumerism.

Introspection. Looking inwardly. Eastern traditions emphasize deepening self-awareness through mindful meditation practices, while Western traditions include taking a personal inventory through self-examination or confessional practices.

Continue to: Traditions

Traditions. Studying sacred texts, participating in communal prayer, meditating, or engaging in rituals. This requires sorting through outmoded beliefs and ways of thinking while updating beliefs that are compatible with our lived experiences.

Transcendence. Experiencing moments, whether through nature, music, dance, ritual, prayer, art, etc., in which the narrow sense of being a separate self fades away and there is a deeper sense of a larger connection and belonging that is transpersonal, timeless, and expansive.

The components of SPIRITT have helped me to think about and pursue the physical, emotional, and social benefits of adopting a spiritual practice for my well-being as well as for the benefit of my patients.

1. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26.

2. Spiritual. Miriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spiritual. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Both patients and clinicians alike have shown increasing interest in spirituality as a component of physical and mental well-being.1 However, there’s no clear consensus on what spirituality actually means. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it “affecting the spirit, relating to sacred matters, concerned with religious issues.”2 Spirituality is sometimes defined in broadly secular terms, such as the feeling of “being part of something greater than ourselves,” or in connection to ideas rooted in a specific belief system, such as “aligning oneself with the Will of God.”

I prefer to think of the word “spiritual” as encompassing multiple practices and beliefs that have the common goal of helping us deepen our capacity for self-awareness, joy, compassion, love, freedom, justice, and mutual cooperation, not only for our own benefit, but also to create a better world. To help clinicians better understand what the term spirituality implies, whether for themselves or for their patients, I offer the acronym SPIRITT to describe core components of varied spiritual perspectives, beliefs, and practices.

Sacred. Considering certain aspects of life, time, or place as non-ordinary and worthy of reverence and awe.

Presence. Cultivating an inner presence that is open, accepting, compassionate, and loving toward others. During a spiritual experience, some may feel embraced in this way by a presence outside of themselves, such as an encounter with a spiritual teacher or an experience of feeling held lovingly by a transcendent power.

Interconnection. Understanding that we are not separate entities but are interconnected beings existing in interdependent unity, starting with our families and extending out universally. According to this perspective, harming anything or anyone is doing harm to ourself.

Rest. Taking a Sabbath or unplugging. Dedicating time each week for resting your mind and body. Spending quality time with family. Decreasing excessive stimulation and loosening the grip of consumerism.

Introspection. Looking inwardly. Eastern traditions emphasize deepening self-awareness through mindful meditation practices, while Western traditions include taking a personal inventory through self-examination or confessional practices.

Continue to: Traditions

Traditions. Studying sacred texts, participating in communal prayer, meditating, or engaging in rituals. This requires sorting through outmoded beliefs and ways of thinking while updating beliefs that are compatible with our lived experiences.

Transcendence. Experiencing moments, whether through nature, music, dance, ritual, prayer, art, etc., in which the narrow sense of being a separate self fades away and there is a deeper sense of a larger connection and belonging that is transpersonal, timeless, and expansive.

The components of SPIRITT have helped me to think about and pursue the physical, emotional, and social benefits of adopting a spiritual practice for my well-being as well as for the benefit of my patients.

Both patients and clinicians alike have shown increasing interest in spirituality as a component of physical and mental well-being.1 However, there’s no clear consensus on what spirituality actually means. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it “affecting the spirit, relating to sacred matters, concerned with religious issues.”2 Spirituality is sometimes defined in broadly secular terms, such as the feeling of “being part of something greater than ourselves,” or in connection to ideas rooted in a specific belief system, such as “aligning oneself with the Will of God.”

I prefer to think of the word “spiritual” as encompassing multiple practices and beliefs that have the common goal of helping us deepen our capacity for self-awareness, joy, compassion, love, freedom, justice, and mutual cooperation, not only for our own benefit, but also to create a better world. To help clinicians better understand what the term spirituality implies, whether for themselves or for their patients, I offer the acronym SPIRITT to describe core components of varied spiritual perspectives, beliefs, and practices.

Sacred. Considering certain aspects of life, time, or place as non-ordinary and worthy of reverence and awe.

Presence. Cultivating an inner presence that is open, accepting, compassionate, and loving toward others. During a spiritual experience, some may feel embraced in this way by a presence outside of themselves, such as an encounter with a spiritual teacher or an experience of feeling held lovingly by a transcendent power.

Interconnection. Understanding that we are not separate entities but are interconnected beings existing in interdependent unity, starting with our families and extending out universally. According to this perspective, harming anything or anyone is doing harm to ourself.

Rest. Taking a Sabbath or unplugging. Dedicating time each week for resting your mind and body. Spending quality time with family. Decreasing excessive stimulation and loosening the grip of consumerism.

Introspection. Looking inwardly. Eastern traditions emphasize deepening self-awareness through mindful meditation practices, while Western traditions include taking a personal inventory through self-examination or confessional practices.

Continue to: Traditions

Traditions. Studying sacred texts, participating in communal prayer, meditating, or engaging in rituals. This requires sorting through outmoded beliefs and ways of thinking while updating beliefs that are compatible with our lived experiences.

Transcendence. Experiencing moments, whether through nature, music, dance, ritual, prayer, art, etc., in which the narrow sense of being a separate self fades away and there is a deeper sense of a larger connection and belonging that is transpersonal, timeless, and expansive.

The components of SPIRITT have helped me to think about and pursue the physical, emotional, and social benefits of adopting a spiritual practice for my well-being as well as for the benefit of my patients.

1. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26.

2. Spiritual. Miriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spiritual. Accessed May 9, 2019.

1. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26.

2. Spiritual. Miriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spiritual. Accessed May 9, 2019.

When your patient is a physician: Overcoming the challenges

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Mobile apps and mental health: Using technology to quantify real-time clinical risk