User login

Small-fiber polyneuropathy may underlie dysautonomia in ME/CFS

A significant proportion of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and dysautonomia may have potentially treatable underlying autoimmune-associated small-fiber polyneuropathy (aaSFPN), pilot data suggest.

The findings, from a single-site study of 61 patients with ME/CFS, were presented August 21 at the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis by Ryan Whelan, BS, a research assistant at Simmaron Research Institute, Incline Village, Nevada.

Recent evidence suggests an autoimmune etiology for some patients with ME/CFS, which is defined as experiencing for a period of at least 6 months profound, unexplained fatigue, postexertional malaise, and unrefreshing sleep, as well as cognitive dysfunction and/or orthostatic intolerance (OI).

OI is part of a spectrum of autonomic dysfunction commonly seen in ME/CFS patients, which may also include postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS), peripheral temperature dysregulation and light sensitivity, neuropathic pain, and gastrointestinal complaints. Many of these symptoms overlap those reported by patients with aaSFPN, a common but underdiagnosed neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of peripheral autonomic nerve fibers, Whelan explained.

Findings from the current study show that in more than half of ME/CFS patients, levels of at least one autoantibody were elevated. A majority had comorbid POTS or OI, and over a third had biopsy-confirmed aaSFPN.

“Given the overlap of symptoms and common etiological basis, it may be important to identify ME/CFS patients who present with comorbid aaSFPN, as it has been shown that immune modulatory agents, including intravenous gamma globulin [IVIG], reduce the autonomic symptom burden in aaSFPN patients,” Whelan said.

He noted that Anne Louise Oaklander, MD, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues previously linked aaSFPN with fibromyalgia. In addition, they’ve found a connection between small-fiber dysfunction and postexertional malaise, which is a hallmark ME/CFS symptom.

Asked to comment on Whelan’s presentation, IACFSME co-president Lily Chu, MD, told Medscape Medical News that the new findings are “valuable, because ME/CFS has always been looked upon as just subjective symptoms. When people have laboratory abnormalities, it can be due to a bunch of other causes, but...here’s pathology, here’s a biopsy of actual damage. It’s not just a transient finding. You can actually see it. ... It’s a solid concrete piece of evidence vs something that can fluctuate.”

Autoantibodies, Autonomic Dysfunction, and Small-Fiber Polyneuropathy

Whelan and colleagues conducted an extensive analysis of medical records of 364 patients with ME/CFS (72% female) to identify potential aaSFPN comorbidity. Such identifications were made on the basis of progress notes documenting autonomic dysfunction, laboratory results for serum autoantibodies, and questionnaire symptom self-reports.

They identified 61 patients as possibly having comorbid aaSFPN. Of those, 52% tested positive for at least 1 of 4 autoantibodies, including antimuscarinic cholinergic receptor 4 (47%), anti-beta-2 adrenergic (27%), antimuscarinic cholinergic 3 (25%), and anti-beta-1 adrenergic (13%). These autoantibodies were linked to ME/CFS in a recent Swedish cohort study.

“Evidence supports that these autoantibodies may bind to receptor sites, blocking ligands from reaching these receptors. Disturbances of adrenergic and cholinergic receptors by these autoantibodies may contribute to symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in ME/CFS,” Whelan said.

Although 22% of patients in the study group had POTS and 59% had OI, the authors found no correlation between autoantibody levels and either OI or POTS. However, 38% were confirmed to have small-fiber polyneuropathy on skin biopsy, and the vast majority of those patients (93%) had either POTS or OI.

IVIG May Be a Potential Treatment

Whelan notes that some data suggest that IVIG might help patients with small-fiber neuropathy, including those with autoimmunity.

In addition, he described anecdotal data from a single patient with ME/CFS who had neuropathic symptoms. The patient was treated at Simmaron. The 56-year-old received two IVIG infusions given 6 months apart. The patient experienced a dramatic reduction in levels of all four of the relevant autoantibodies and favorable symptom reduction, as shown in clinician follow-up records. “With the success of this case study, we intend to further evaluate IVIG as a potential treatment in ME/CFS patients. With this research, we hope to identify a subset of ME/CFS patients who will respond favorably to IVIG,” Whelan concluded.

Regarding use of IVIG, Chu commented, “We don’t know exactly how it works, but it seems to help certain conditions.” She pointed to another recent small study that reported clinical improvement in patients with ME/CFS through a different approach, immunoadsorption, for reducing the autoantibody levels.

Overall, Chu said, this line of research “is important because it shows there’s some type of abnormal biomarker for ME/CFS. And, it may lay a path toward understanding the pathophysiology of the disease and why people have certain symptoms, and could be used to target therapies. ... It’s intriguing.”

Whelan and Chu have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A significant proportion of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and dysautonomia may have potentially treatable underlying autoimmune-associated small-fiber polyneuropathy (aaSFPN), pilot data suggest.

The findings, from a single-site study of 61 patients with ME/CFS, were presented August 21 at the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis by Ryan Whelan, BS, a research assistant at Simmaron Research Institute, Incline Village, Nevada.

Recent evidence suggests an autoimmune etiology for some patients with ME/CFS, which is defined as experiencing for a period of at least 6 months profound, unexplained fatigue, postexertional malaise, and unrefreshing sleep, as well as cognitive dysfunction and/or orthostatic intolerance (OI).

OI is part of a spectrum of autonomic dysfunction commonly seen in ME/CFS patients, which may also include postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS), peripheral temperature dysregulation and light sensitivity, neuropathic pain, and gastrointestinal complaints. Many of these symptoms overlap those reported by patients with aaSFPN, a common but underdiagnosed neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of peripheral autonomic nerve fibers, Whelan explained.

Findings from the current study show that in more than half of ME/CFS patients, levels of at least one autoantibody were elevated. A majority had comorbid POTS or OI, and over a third had biopsy-confirmed aaSFPN.

“Given the overlap of symptoms and common etiological basis, it may be important to identify ME/CFS patients who present with comorbid aaSFPN, as it has been shown that immune modulatory agents, including intravenous gamma globulin [IVIG], reduce the autonomic symptom burden in aaSFPN patients,” Whelan said.

He noted that Anne Louise Oaklander, MD, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues previously linked aaSFPN with fibromyalgia. In addition, they’ve found a connection between small-fiber dysfunction and postexertional malaise, which is a hallmark ME/CFS symptom.

Asked to comment on Whelan’s presentation, IACFSME co-president Lily Chu, MD, told Medscape Medical News that the new findings are “valuable, because ME/CFS has always been looked upon as just subjective symptoms. When people have laboratory abnormalities, it can be due to a bunch of other causes, but...here’s pathology, here’s a biopsy of actual damage. It’s not just a transient finding. You can actually see it. ... It’s a solid concrete piece of evidence vs something that can fluctuate.”

Autoantibodies, Autonomic Dysfunction, and Small-Fiber Polyneuropathy

Whelan and colleagues conducted an extensive analysis of medical records of 364 patients with ME/CFS (72% female) to identify potential aaSFPN comorbidity. Such identifications were made on the basis of progress notes documenting autonomic dysfunction, laboratory results for serum autoantibodies, and questionnaire symptom self-reports.

They identified 61 patients as possibly having comorbid aaSFPN. Of those, 52% tested positive for at least 1 of 4 autoantibodies, including antimuscarinic cholinergic receptor 4 (47%), anti-beta-2 adrenergic (27%), antimuscarinic cholinergic 3 (25%), and anti-beta-1 adrenergic (13%). These autoantibodies were linked to ME/CFS in a recent Swedish cohort study.

“Evidence supports that these autoantibodies may bind to receptor sites, blocking ligands from reaching these receptors. Disturbances of adrenergic and cholinergic receptors by these autoantibodies may contribute to symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in ME/CFS,” Whelan said.

Although 22% of patients in the study group had POTS and 59% had OI, the authors found no correlation between autoantibody levels and either OI or POTS. However, 38% were confirmed to have small-fiber polyneuropathy on skin biopsy, and the vast majority of those patients (93%) had either POTS or OI.

IVIG May Be a Potential Treatment

Whelan notes that some data suggest that IVIG might help patients with small-fiber neuropathy, including those with autoimmunity.

In addition, he described anecdotal data from a single patient with ME/CFS who had neuropathic symptoms. The patient was treated at Simmaron. The 56-year-old received two IVIG infusions given 6 months apart. The patient experienced a dramatic reduction in levels of all four of the relevant autoantibodies and favorable symptom reduction, as shown in clinician follow-up records. “With the success of this case study, we intend to further evaluate IVIG as a potential treatment in ME/CFS patients. With this research, we hope to identify a subset of ME/CFS patients who will respond favorably to IVIG,” Whelan concluded.

Regarding use of IVIG, Chu commented, “We don’t know exactly how it works, but it seems to help certain conditions.” She pointed to another recent small study that reported clinical improvement in patients with ME/CFS through a different approach, immunoadsorption, for reducing the autoantibody levels.

Overall, Chu said, this line of research “is important because it shows there’s some type of abnormal biomarker for ME/CFS. And, it may lay a path toward understanding the pathophysiology of the disease and why people have certain symptoms, and could be used to target therapies. ... It’s intriguing.”

Whelan and Chu have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A significant proportion of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and dysautonomia may have potentially treatable underlying autoimmune-associated small-fiber polyneuropathy (aaSFPN), pilot data suggest.

The findings, from a single-site study of 61 patients with ME/CFS, were presented August 21 at the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis by Ryan Whelan, BS, a research assistant at Simmaron Research Institute, Incline Village, Nevada.

Recent evidence suggests an autoimmune etiology for some patients with ME/CFS, which is defined as experiencing for a period of at least 6 months profound, unexplained fatigue, postexertional malaise, and unrefreshing sleep, as well as cognitive dysfunction and/or orthostatic intolerance (OI).

OI is part of a spectrum of autonomic dysfunction commonly seen in ME/CFS patients, which may also include postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS), peripheral temperature dysregulation and light sensitivity, neuropathic pain, and gastrointestinal complaints. Many of these symptoms overlap those reported by patients with aaSFPN, a common but underdiagnosed neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of peripheral autonomic nerve fibers, Whelan explained.

Findings from the current study show that in more than half of ME/CFS patients, levels of at least one autoantibody were elevated. A majority had comorbid POTS or OI, and over a third had biopsy-confirmed aaSFPN.

“Given the overlap of symptoms and common etiological basis, it may be important to identify ME/CFS patients who present with comorbid aaSFPN, as it has been shown that immune modulatory agents, including intravenous gamma globulin [IVIG], reduce the autonomic symptom burden in aaSFPN patients,” Whelan said.

He noted that Anne Louise Oaklander, MD, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues previously linked aaSFPN with fibromyalgia. In addition, they’ve found a connection between small-fiber dysfunction and postexertional malaise, which is a hallmark ME/CFS symptom.

Asked to comment on Whelan’s presentation, IACFSME co-president Lily Chu, MD, told Medscape Medical News that the new findings are “valuable, because ME/CFS has always been looked upon as just subjective symptoms. When people have laboratory abnormalities, it can be due to a bunch of other causes, but...here’s pathology, here’s a biopsy of actual damage. It’s not just a transient finding. You can actually see it. ... It’s a solid concrete piece of evidence vs something that can fluctuate.”

Autoantibodies, Autonomic Dysfunction, and Small-Fiber Polyneuropathy

Whelan and colleagues conducted an extensive analysis of medical records of 364 patients with ME/CFS (72% female) to identify potential aaSFPN comorbidity. Such identifications were made on the basis of progress notes documenting autonomic dysfunction, laboratory results for serum autoantibodies, and questionnaire symptom self-reports.

They identified 61 patients as possibly having comorbid aaSFPN. Of those, 52% tested positive for at least 1 of 4 autoantibodies, including antimuscarinic cholinergic receptor 4 (47%), anti-beta-2 adrenergic (27%), antimuscarinic cholinergic 3 (25%), and anti-beta-1 adrenergic (13%). These autoantibodies were linked to ME/CFS in a recent Swedish cohort study.

“Evidence supports that these autoantibodies may bind to receptor sites, blocking ligands from reaching these receptors. Disturbances of adrenergic and cholinergic receptors by these autoantibodies may contribute to symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in ME/CFS,” Whelan said.

Although 22% of patients in the study group had POTS and 59% had OI, the authors found no correlation between autoantibody levels and either OI or POTS. However, 38% were confirmed to have small-fiber polyneuropathy on skin biopsy, and the vast majority of those patients (93%) had either POTS or OI.

IVIG May Be a Potential Treatment

Whelan notes that some data suggest that IVIG might help patients with small-fiber neuropathy, including those with autoimmunity.

In addition, he described anecdotal data from a single patient with ME/CFS who had neuropathic symptoms. The patient was treated at Simmaron. The 56-year-old received two IVIG infusions given 6 months apart. The patient experienced a dramatic reduction in levels of all four of the relevant autoantibodies and favorable symptom reduction, as shown in clinician follow-up records. “With the success of this case study, we intend to further evaluate IVIG as a potential treatment in ME/CFS patients. With this research, we hope to identify a subset of ME/CFS patients who will respond favorably to IVIG,” Whelan concluded.

Regarding use of IVIG, Chu commented, “We don’t know exactly how it works, but it seems to help certain conditions.” She pointed to another recent small study that reported clinical improvement in patients with ME/CFS through a different approach, immunoadsorption, for reducing the autoantibody levels.

Overall, Chu said, this line of research “is important because it shows there’s some type of abnormal biomarker for ME/CFS. And, it may lay a path toward understanding the pathophysiology of the disease and why people have certain symptoms, and could be used to target therapies. ... It’s intriguing.”

Whelan and Chu have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Appendix may be common site of endometriosis

Among women who have a coincidental appendectomy during surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis, about 15% have appendiceal endometriosis confirmed by pathological examination, according to a study.

“In the women with appendiceal endometriosis, only 26% had an appendix that looked abnormal,” said Whitney T. Ross, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Penn State Health, Hershey.

The results, presented at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, indicate that “appendiceal endometriosis is common in women receiving surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis,” she said. “This study and multiple other studies have also demonstrated that coincidental appendectomy is safe.”

The long-term impact of coincidental appendectomy and its effect on quality of life are not known, however, which may make it difficult to weigh the costs and benefits of the procedure, Dr. Ross said. “It is important to talk to patients about this procedure and determine which approach is the right approach for your institution.”

The study of 609 coincidental appendectomies did not include patients with retrocecal appendices, which may confound the true rate of appendiceal endometriosis, commented Saifuddin T. Mama, MD, MPH, of Rowan University, Camden, N.J.

When the investigators started the study, they were not sure of the risks and benefits of the procedure in patients with retrocecal appendices. An anecdotal report from another research group suggests that outcomes with retrocecal appendices may not be significantly different. “But that is certainly an important question and one that we would like to address in a future prospective study,” Dr. Ross said.

Surgeons have debated the role of coincidental appendectomy during gynecologic surgery. Concerns about safety and questions about the prevalence of appendiceal pathology are reasons that coincidental appendectomy has not been more widely adopted. On the other hand, the procedure may benefit patients and aid diagnosis.

To evaluate the role of coincidental appendectomy in the surgical excision of endometriosis, Dr. Ross and colleagues analyzed data from consecutive coincidental appendectomies performed at one institution between 2013 and 2019. They identified cases in a prospectively maintained surgical database to assess safety and the prevalence of appendiceal pathology.

The indication for surgery was chronic pelvic pain but no visualized endometriosis for 42 patients, stage I-II endometriosis for 388 patients, and stage III-IV endometriosis for 179 patients.

Surgeries included laparoscopic hysterectomy (77.5%), operative laparoscopy (19.9%), and laparoscopic trachelectomy (2.6%). Pathological analysis of the appendices identified endometriosis in 14.9%, malignancy in 0.7%, polyps in 0.5%, and appendicitis in 0.3%.

Among women with chronic pelvic pain but no visualized endometriosis, 2.4% had appendiceal endometriosis. Among those with stage I-II endometriosis, 7% had appendiceal endometriosis, and in patients with stage III-IV endometriosis, the rate of appendiceal endometriosis was 35.2%.

In about 6% of patients with appendiceal endometriosis, the appendix was the only site of pathologically confirmed endometriosis.

Compared with chronic pelvic pain, stage III-IV endometriosis was associated with a significantly increased risk of appendiceal endometriosis (odds ratio, 22.2). The likelihood of appendiceal endometriosis also increased when the appendix looked abnormal (odds ratio, 6.5).

The probability of diagnosing appendiceal endometriosis also increases with the number of other locations of confirmed endometriosis.

“Our surgical decision making is based off of intraoperative findings. However, the final gold-standard diagnosis can’t take place until the pathologic specimen is analyzed,” she said. “We also know that there is a significant discordance, as high as 50%, in early-stage endometriosis between visual inspection and pathology findings.”

There were no complications related to the performance of a coincidental appendectomy during surgery or in the 12 weeks after.

Dr. Ross outlined surgeons’ three main options for performing coincidental appendectomy in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis: universal coincidental appendectomy, targeted appendectomy based on operative findings, and performing the procedure based on the appearance of the appendix.

Basing the decision on appearance “is going to miss a lot of appendiceal endometriosis,” Dr. Ross said. In the present study, 67 of the 91 cases, about 74%, would have been missed.

Dr. Ross and Dr. Mama had no relevant financial disclosures. The study coauthors disclosed ties to Titan Medical, Merck, and AbbVie.

SOURCE: Ross WT et al. SGS 2020, Abstract 14.

Among women who have a coincidental appendectomy during surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis, about 15% have appendiceal endometriosis confirmed by pathological examination, according to a study.

“In the women with appendiceal endometriosis, only 26% had an appendix that looked abnormal,” said Whitney T. Ross, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Penn State Health, Hershey.

The results, presented at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, indicate that “appendiceal endometriosis is common in women receiving surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis,” she said. “This study and multiple other studies have also demonstrated that coincidental appendectomy is safe.”

The long-term impact of coincidental appendectomy and its effect on quality of life are not known, however, which may make it difficult to weigh the costs and benefits of the procedure, Dr. Ross said. “It is important to talk to patients about this procedure and determine which approach is the right approach for your institution.”

The study of 609 coincidental appendectomies did not include patients with retrocecal appendices, which may confound the true rate of appendiceal endometriosis, commented Saifuddin T. Mama, MD, MPH, of Rowan University, Camden, N.J.

When the investigators started the study, they were not sure of the risks and benefits of the procedure in patients with retrocecal appendices. An anecdotal report from another research group suggests that outcomes with retrocecal appendices may not be significantly different. “But that is certainly an important question and one that we would like to address in a future prospective study,” Dr. Ross said.

Surgeons have debated the role of coincidental appendectomy during gynecologic surgery. Concerns about safety and questions about the prevalence of appendiceal pathology are reasons that coincidental appendectomy has not been more widely adopted. On the other hand, the procedure may benefit patients and aid diagnosis.

To evaluate the role of coincidental appendectomy in the surgical excision of endometriosis, Dr. Ross and colleagues analyzed data from consecutive coincidental appendectomies performed at one institution between 2013 and 2019. They identified cases in a prospectively maintained surgical database to assess safety and the prevalence of appendiceal pathology.

The indication for surgery was chronic pelvic pain but no visualized endometriosis for 42 patients, stage I-II endometriosis for 388 patients, and stage III-IV endometriosis for 179 patients.

Surgeries included laparoscopic hysterectomy (77.5%), operative laparoscopy (19.9%), and laparoscopic trachelectomy (2.6%). Pathological analysis of the appendices identified endometriosis in 14.9%, malignancy in 0.7%, polyps in 0.5%, and appendicitis in 0.3%.

Among women with chronic pelvic pain but no visualized endometriosis, 2.4% had appendiceal endometriosis. Among those with stage I-II endometriosis, 7% had appendiceal endometriosis, and in patients with stage III-IV endometriosis, the rate of appendiceal endometriosis was 35.2%.

In about 6% of patients with appendiceal endometriosis, the appendix was the only site of pathologically confirmed endometriosis.

Compared with chronic pelvic pain, stage III-IV endometriosis was associated with a significantly increased risk of appendiceal endometriosis (odds ratio, 22.2). The likelihood of appendiceal endometriosis also increased when the appendix looked abnormal (odds ratio, 6.5).

The probability of diagnosing appendiceal endometriosis also increases with the number of other locations of confirmed endometriosis.

“Our surgical decision making is based off of intraoperative findings. However, the final gold-standard diagnosis can’t take place until the pathologic specimen is analyzed,” she said. “We also know that there is a significant discordance, as high as 50%, in early-stage endometriosis between visual inspection and pathology findings.”

There were no complications related to the performance of a coincidental appendectomy during surgery or in the 12 weeks after.

Dr. Ross outlined surgeons’ three main options for performing coincidental appendectomy in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis: universal coincidental appendectomy, targeted appendectomy based on operative findings, and performing the procedure based on the appearance of the appendix.

Basing the decision on appearance “is going to miss a lot of appendiceal endometriosis,” Dr. Ross said. In the present study, 67 of the 91 cases, about 74%, would have been missed.

Dr. Ross and Dr. Mama had no relevant financial disclosures. The study coauthors disclosed ties to Titan Medical, Merck, and AbbVie.

SOURCE: Ross WT et al. SGS 2020, Abstract 14.

Among women who have a coincidental appendectomy during surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis, about 15% have appendiceal endometriosis confirmed by pathological examination, according to a study.

“In the women with appendiceal endometriosis, only 26% had an appendix that looked abnormal,” said Whitney T. Ross, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Penn State Health, Hershey.

The results, presented at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, indicate that “appendiceal endometriosis is common in women receiving surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis,” she said. “This study and multiple other studies have also demonstrated that coincidental appendectomy is safe.”

The long-term impact of coincidental appendectomy and its effect on quality of life are not known, however, which may make it difficult to weigh the costs and benefits of the procedure, Dr. Ross said. “It is important to talk to patients about this procedure and determine which approach is the right approach for your institution.”

The study of 609 coincidental appendectomies did not include patients with retrocecal appendices, which may confound the true rate of appendiceal endometriosis, commented Saifuddin T. Mama, MD, MPH, of Rowan University, Camden, N.J.

When the investigators started the study, they were not sure of the risks and benefits of the procedure in patients with retrocecal appendices. An anecdotal report from another research group suggests that outcomes with retrocecal appendices may not be significantly different. “But that is certainly an important question and one that we would like to address in a future prospective study,” Dr. Ross said.

Surgeons have debated the role of coincidental appendectomy during gynecologic surgery. Concerns about safety and questions about the prevalence of appendiceal pathology are reasons that coincidental appendectomy has not been more widely adopted. On the other hand, the procedure may benefit patients and aid diagnosis.

To evaluate the role of coincidental appendectomy in the surgical excision of endometriosis, Dr. Ross and colleagues analyzed data from consecutive coincidental appendectomies performed at one institution between 2013 and 2019. They identified cases in a prospectively maintained surgical database to assess safety and the prevalence of appendiceal pathology.

The indication for surgery was chronic pelvic pain but no visualized endometriosis for 42 patients, stage I-II endometriosis for 388 patients, and stage III-IV endometriosis for 179 patients.

Surgeries included laparoscopic hysterectomy (77.5%), operative laparoscopy (19.9%), and laparoscopic trachelectomy (2.6%). Pathological analysis of the appendices identified endometriosis in 14.9%, malignancy in 0.7%, polyps in 0.5%, and appendicitis in 0.3%.

Among women with chronic pelvic pain but no visualized endometriosis, 2.4% had appendiceal endometriosis. Among those with stage I-II endometriosis, 7% had appendiceal endometriosis, and in patients with stage III-IV endometriosis, the rate of appendiceal endometriosis was 35.2%.

In about 6% of patients with appendiceal endometriosis, the appendix was the only site of pathologically confirmed endometriosis.

Compared with chronic pelvic pain, stage III-IV endometriosis was associated with a significantly increased risk of appendiceal endometriosis (odds ratio, 22.2). The likelihood of appendiceal endometriosis also increased when the appendix looked abnormal (odds ratio, 6.5).

The probability of diagnosing appendiceal endometriosis also increases with the number of other locations of confirmed endometriosis.

“Our surgical decision making is based off of intraoperative findings. However, the final gold-standard diagnosis can’t take place until the pathologic specimen is analyzed,” she said. “We also know that there is a significant discordance, as high as 50%, in early-stage endometriosis between visual inspection and pathology findings.”

There were no complications related to the performance of a coincidental appendectomy during surgery or in the 12 weeks after.

Dr. Ross outlined surgeons’ three main options for performing coincidental appendectomy in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis: universal coincidental appendectomy, targeted appendectomy based on operative findings, and performing the procedure based on the appearance of the appendix.

Basing the decision on appearance “is going to miss a lot of appendiceal endometriosis,” Dr. Ross said. In the present study, 67 of the 91 cases, about 74%, would have been missed.

Dr. Ross and Dr. Mama had no relevant financial disclosures. The study coauthors disclosed ties to Titan Medical, Merck, and AbbVie.

SOURCE: Ross WT et al. SGS 2020, Abstract 14.

FROM SGS 2020

AHA on cannabis: No evidence of heart benefits, but potential harms

Evidence for a link between cannabis use and cardiovascular health remains unsupported, and the potential risks outweigh any potential benefits, according to a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The increased legalization of cannabis and cannabis products in the United States has driven medical professionals to evaluate the safety and efficacy of cannabis in relation to health conditions, wrote Robert L. Page II, PharmD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and colleagues.

In a statement published in Circulation, the researchers noted that although cannabis has been shown to relieve pain and other symptoms in certain conditions, clinicians in the United States have been limited from studying its health effects because of federal law restrictions. “Cannabis remains a schedule I controlled substance, deeming no accepted medical use, a high potential for abuse, and an unacceptable safety profile,” the researchers wrote.

The statement addresses issues with the use of cannabis by individuals with cardiovascular disease or those at increased risk. Observational studies have shown no cardiovascular benefits associated with cannabis, the writers noted. The most common chemicals in cannabis include THC (tetrahydrocannabinolic acid) and CBD (cannabidiol).

Some research has shown associations between CBD cardiovascular features including lower blood pressure and reduced inflammation, the writers noted. However, THC, the component of cannabis associated with a “high” or intoxication, has been associated with heart rhythm abnormalities. The writers cited data suggesting an increased risk of heart attacks, atrial fibrillation and heart failure, although more research is needed.

The statement outlines common cannabis formulations including plant-based, extracts, crystalline forms, edible products, and tinctures. In addition, the statement notes that synthetic cannabis products are marketed and used in the United States without subject to regulation.

“Over the past 5 years, we have seen a surge in cannabis use, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic here in Colorado, especially among adolescents and young adults,” Dr. Page said in an interview. Because of the surge, health care practitioners need to familiarize themselves with not only the benefits, but risks associated with cannabis use regardless of the formulation,” he said. As heart disease remains a leading cause of death in the United States, understanding the cardiovascular risks associated with cannabis is crucial at this time.

Dr. Page noted that popular attitudes about cannabis could pose risks to users’ cardiovascular health. “One leading misconception about cannabis is because it is ‘natural’ it must be safe,” Dr. Page said. “As with all medications, cannabis has side effects, some of which can be cardiovascular in nature,” he said. “Significant drug-drug interactions can occur as CBD and THC, both found in cannabis, inhibit CYP3A4, which metabolizes a large number of medications used to treat many cardiovascular conditions,” he noted.

“Unfortunately, much of the published data is observational in nature due to the federal restrictions on cannabis as a schedule I drug,” said Dr. Page. “Nonetheless, safety signals have emerged regarding cannabis use and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. Carefully designed prospective short- and long-term studies regarding cannabis use and cardiovascular safety are needed,” he emphasized.

Areas in particular need of additional research include the cardiovascular effects of cannabis in several vulnerable populations such as adolescents, older adults, pregnant women, transplant recipients, and those with underlying cardiovascular disease, said Dr. Page.

“Nonetheless, based on the safety signals described within this Clinical Science Statement, an open discussion regarding the risks of using cannabis needs to occur between patient and health care providers,” he said. “Furthermore, patients must be transparent regarding their cannabis use with their cardiologist and primary care provider. The cannabis story will continue to evolve and is a rapidly moving/changing target,” he said.

“Whether cannabis use is a definitive risk factor for cardiovascular disease as with tobacco use is still unknown, and both acute and long-term studies are desperately needed to address this issue,” he said.

Dr. Page had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Page et al. Circulation. 2020 Aug 5. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000883.

Evidence for a link between cannabis use and cardiovascular health remains unsupported, and the potential risks outweigh any potential benefits, according to a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The increased legalization of cannabis and cannabis products in the United States has driven medical professionals to evaluate the safety and efficacy of cannabis in relation to health conditions, wrote Robert L. Page II, PharmD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and colleagues.

In a statement published in Circulation, the researchers noted that although cannabis has been shown to relieve pain and other symptoms in certain conditions, clinicians in the United States have been limited from studying its health effects because of federal law restrictions. “Cannabis remains a schedule I controlled substance, deeming no accepted medical use, a high potential for abuse, and an unacceptable safety profile,” the researchers wrote.

The statement addresses issues with the use of cannabis by individuals with cardiovascular disease or those at increased risk. Observational studies have shown no cardiovascular benefits associated with cannabis, the writers noted. The most common chemicals in cannabis include THC (tetrahydrocannabinolic acid) and CBD (cannabidiol).

Some research has shown associations between CBD cardiovascular features including lower blood pressure and reduced inflammation, the writers noted. However, THC, the component of cannabis associated with a “high” or intoxication, has been associated with heart rhythm abnormalities. The writers cited data suggesting an increased risk of heart attacks, atrial fibrillation and heart failure, although more research is needed.

The statement outlines common cannabis formulations including plant-based, extracts, crystalline forms, edible products, and tinctures. In addition, the statement notes that synthetic cannabis products are marketed and used in the United States without subject to regulation.

“Over the past 5 years, we have seen a surge in cannabis use, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic here in Colorado, especially among adolescents and young adults,” Dr. Page said in an interview. Because of the surge, health care practitioners need to familiarize themselves with not only the benefits, but risks associated with cannabis use regardless of the formulation,” he said. As heart disease remains a leading cause of death in the United States, understanding the cardiovascular risks associated with cannabis is crucial at this time.

Dr. Page noted that popular attitudes about cannabis could pose risks to users’ cardiovascular health. “One leading misconception about cannabis is because it is ‘natural’ it must be safe,” Dr. Page said. “As with all medications, cannabis has side effects, some of which can be cardiovascular in nature,” he said. “Significant drug-drug interactions can occur as CBD and THC, both found in cannabis, inhibit CYP3A4, which metabolizes a large number of medications used to treat many cardiovascular conditions,” he noted.

“Unfortunately, much of the published data is observational in nature due to the federal restrictions on cannabis as a schedule I drug,” said Dr. Page. “Nonetheless, safety signals have emerged regarding cannabis use and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. Carefully designed prospective short- and long-term studies regarding cannabis use and cardiovascular safety are needed,” he emphasized.

Areas in particular need of additional research include the cardiovascular effects of cannabis in several vulnerable populations such as adolescents, older adults, pregnant women, transplant recipients, and those with underlying cardiovascular disease, said Dr. Page.

“Nonetheless, based on the safety signals described within this Clinical Science Statement, an open discussion regarding the risks of using cannabis needs to occur between patient and health care providers,” he said. “Furthermore, patients must be transparent regarding their cannabis use with their cardiologist and primary care provider. The cannabis story will continue to evolve and is a rapidly moving/changing target,” he said.

“Whether cannabis use is a definitive risk factor for cardiovascular disease as with tobacco use is still unknown, and both acute and long-term studies are desperately needed to address this issue,” he said.

Dr. Page had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Page et al. Circulation. 2020 Aug 5. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000883.

Evidence for a link between cannabis use and cardiovascular health remains unsupported, and the potential risks outweigh any potential benefits, according to a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The increased legalization of cannabis and cannabis products in the United States has driven medical professionals to evaluate the safety and efficacy of cannabis in relation to health conditions, wrote Robert L. Page II, PharmD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and colleagues.

In a statement published in Circulation, the researchers noted that although cannabis has been shown to relieve pain and other symptoms in certain conditions, clinicians in the United States have been limited from studying its health effects because of federal law restrictions. “Cannabis remains a schedule I controlled substance, deeming no accepted medical use, a high potential for abuse, and an unacceptable safety profile,” the researchers wrote.

The statement addresses issues with the use of cannabis by individuals with cardiovascular disease or those at increased risk. Observational studies have shown no cardiovascular benefits associated with cannabis, the writers noted. The most common chemicals in cannabis include THC (tetrahydrocannabinolic acid) and CBD (cannabidiol).

Some research has shown associations between CBD cardiovascular features including lower blood pressure and reduced inflammation, the writers noted. However, THC, the component of cannabis associated with a “high” or intoxication, has been associated with heart rhythm abnormalities. The writers cited data suggesting an increased risk of heart attacks, atrial fibrillation and heart failure, although more research is needed.

The statement outlines common cannabis formulations including plant-based, extracts, crystalline forms, edible products, and tinctures. In addition, the statement notes that synthetic cannabis products are marketed and used in the United States without subject to regulation.

“Over the past 5 years, we have seen a surge in cannabis use, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic here in Colorado, especially among adolescents and young adults,” Dr. Page said in an interview. Because of the surge, health care practitioners need to familiarize themselves with not only the benefits, but risks associated with cannabis use regardless of the formulation,” he said. As heart disease remains a leading cause of death in the United States, understanding the cardiovascular risks associated with cannabis is crucial at this time.

Dr. Page noted that popular attitudes about cannabis could pose risks to users’ cardiovascular health. “One leading misconception about cannabis is because it is ‘natural’ it must be safe,” Dr. Page said. “As with all medications, cannabis has side effects, some of which can be cardiovascular in nature,” he said. “Significant drug-drug interactions can occur as CBD and THC, both found in cannabis, inhibit CYP3A4, which metabolizes a large number of medications used to treat many cardiovascular conditions,” he noted.

“Unfortunately, much of the published data is observational in nature due to the federal restrictions on cannabis as a schedule I drug,” said Dr. Page. “Nonetheless, safety signals have emerged regarding cannabis use and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. Carefully designed prospective short- and long-term studies regarding cannabis use and cardiovascular safety are needed,” he emphasized.

Areas in particular need of additional research include the cardiovascular effects of cannabis in several vulnerable populations such as adolescents, older adults, pregnant women, transplant recipients, and those with underlying cardiovascular disease, said Dr. Page.

“Nonetheless, based on the safety signals described within this Clinical Science Statement, an open discussion regarding the risks of using cannabis needs to occur between patient and health care providers,” he said. “Furthermore, patients must be transparent regarding their cannabis use with their cardiologist and primary care provider. The cannabis story will continue to evolve and is a rapidly moving/changing target,” he said.

“Whether cannabis use is a definitive risk factor for cardiovascular disease as with tobacco use is still unknown, and both acute and long-term studies are desperately needed to address this issue,” he said.

Dr. Page had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Page et al. Circulation. 2020 Aug 5. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000883.

FROM CIRCULATION

All NSAIDs raise post-MI risk but some are safer than others: Next chapter

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

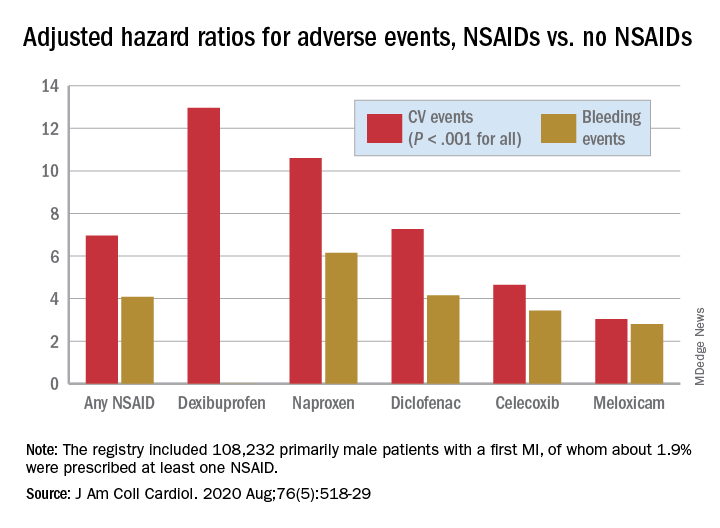

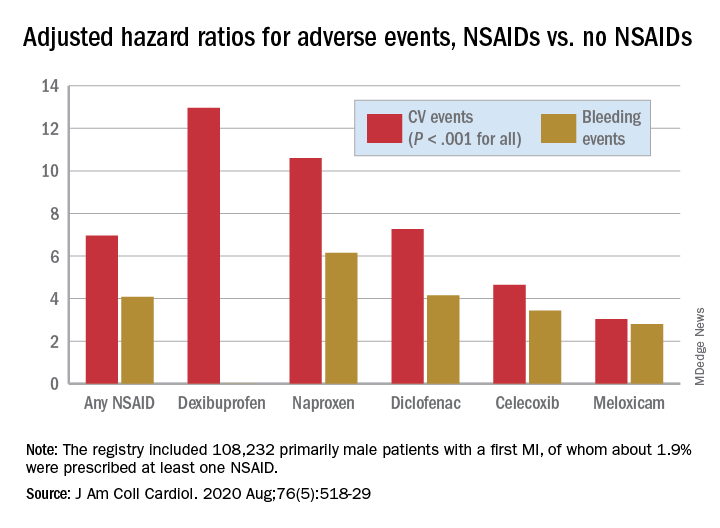

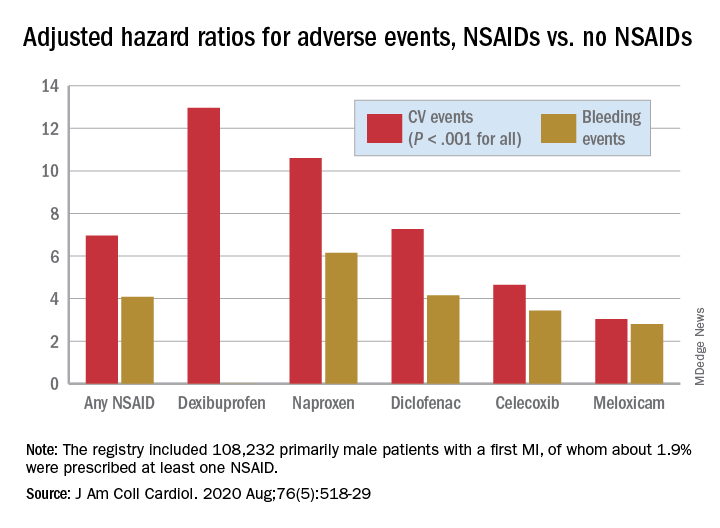

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Exploring cannabis use by older adults

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4

Past-year cannabis use in the groups of those aged 50-64 and those aged 65 and older appears to be higher in individuals with mental health problems, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.5,6 Being male and being unmarried appear to be correlated with past-year cannabis use. Multimorbidity does not appear to be associated with past-year cannabis use. Those using cannabis tend to be long-term users and have first use at a much younger age, typically before age 21.

Older adults use cannabis for both recreational and perceived medical benefits. Arthritis, chronic back pain, anxiety, depression, relaxation, stress reduction, and enhancement in terms of creativity are all purported reasons for use. However, there is limited to no evidence for the efficacy of cannabis in helping with those conditions and purposes. Clinical trials have shown that cannabis can be beneficial in managing pain and nausea, but those trials have not been conducted in older adults.7,8

There is a real risk of cannabis use having a negative impact on the health of older adults. To begin with, the cannabis consumed today is significantly higher in potency than the cannabis that baby boomers were introduced to in their youth. The higher potency, combined with an age-related decline in function experienced by some older adults, makes them vulnerable to its known side effects, such as anxiety, dry mouth, tachycardia, high blood pressure, palpitations, wheezing, confusion, and dizziness.

Cannabis use is reported to bring a fourfold increase in cardiac events within the first hour of ingestion.9 Cognitive decline and memory impairment are well known adverse effects of cannabis use. Research has shown significant self-reported cognitive decline in older adults in relation to cannabis use.Cannabis metabolites are known to have an effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes, affecting the metabolism of medication, and increasing the susceptibility of older adults who use cannabis to adverse effects of polypharmacy. Finally, as research on emergency department visits by older adults shows, cannabis use can increase the risk of injury among this cohort.

As in the United States, cannabis use among older adults in Canada has increased significantly. The percentage of older adults who use cannabis in the Canadian province of Ontario, for example, reportedly doubled from 2005 to 2015. In response to this increase, and in anticipation of a rise in problematic use of cannabis and cannabis use disorder in older adults, the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (through financial support from Substance Use and Addictions Program of Health Canada) has created guidelines on the prevention, assessment, and management of cannabis use disorder in older adults.

In the absence of a set of guidelines specific to the United States, the recommendations made by the coalition should be helpful in the care of older Americans. Among other recommendations, the guidelines highlight the needs for primary care physicians to build a better knowledge base around the use of cannabis in older adults, to screen older adults for cannabis use, and to educate older adults and their families about the risk of cannabis use.9

Cannabis use is increasingly popular among older adults10 for both medicinal and recreational purposes. Research and data supporting its medical benefits are limited, and the potential of harm from its use among older adults is present and significant. Importantly, many older adults who use marijuana have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use disorder(s).

Often, our older patients learn about benefits and harms of cannabis from friends and the Internet rather than from physicians and other clinicians.9 We must do our part to make sure that older patients understand the potential negative health impact that cannabis can have on their health. Physicians should screen older adults for marijuana use. Building a better knowledge base around changing trends and views in/on the use and accessibility of cannabis will help physicians better address cannabis use in older adults.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in vulnerable populations.

References

1. Vespa J et al. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Feb.

2. Han BH et al. Addiction. 2016 Oct 21. doi: 10.1111/add.13670.

3. Han BH and Palamar JJ. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Oct;191:374-81.

4. Han BH and Palamar JJ. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 4;180(4):609-11.

5. Choi NG et al. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215-23.

6. Reynolds IR et al. J Am Griatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2167-71.

7. Ahmed AIA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Feb;62(2):410-1.

8. Lum HD et al. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019 Jan-Dec;5:2333721419843707.

9. Bertram JR et al. Can Geriatr J. 2020 Mar;23(1):135-42.

10. Baumbusch J and Yip IS. Clin Gerontol. 2020 Mar 29;1-7.

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4

Past-year cannabis use in the groups of those aged 50-64 and those aged 65 and older appears to be higher in individuals with mental health problems, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.5,6 Being male and being unmarried appear to be correlated with past-year cannabis use. Multimorbidity does not appear to be associated with past-year cannabis use. Those using cannabis tend to be long-term users and have first use at a much younger age, typically before age 21.

Older adults use cannabis for both recreational and perceived medical benefits. Arthritis, chronic back pain, anxiety, depression, relaxation, stress reduction, and enhancement in terms of creativity are all purported reasons for use. However, there is limited to no evidence for the efficacy of cannabis in helping with those conditions and purposes. Clinical trials have shown that cannabis can be beneficial in managing pain and nausea, but those trials have not been conducted in older adults.7,8