User login

Why do young men target schools for violent attacks? And what can we do about it?

Schools are intended to be a safe place to acquire knowledge, try out ideas, practice socializing, and build a foundation for adulthood. Many schools fulfill this mission for most children, but for children at both extremes of ability their school experience does not suffice.

When asked, “If you had the choice, would you rather stay home or go to school?” my patients almost universally prefer school. They all know that school is where they should be; they want to be normal, accepted by peers, getting ready for the world’s coming demands, and validation that they will make it as adults. Endorsement otherwise is a warning sign.

When such important tasks of childhood are thwarted children may despair, withdraw, give up, or a small number become furious. These may profoundly resent the children who are experiencing success when they could not. They may hate the teachers and the place where they experienced failure and humiliation. Lack of a positive connection to school characterizes children who are violent toward schools as well as those who drop out.

Schools may fail to support the basic needs of children for many reasons. Schools may avoid physical violence but fail to protect the children’s self-esteem. I have heard stories of teachers calling on children to perform who are clearly struggling or shy, insulting incorrect answers, calling names, putting names on the board, reading out failed grades, posting grades publicly, even allowing peers to mock students. Teachers may deny or disregard parent complaints, or even worsen treatment of the child. Although children may at times falsify complaints, children’s and parents’ reports must be taken seriously and remain anonymous. When we hear of such toxic situations for our patients, we can get details and contact school administrators without naming the child, as often the family feels they can’t. Repeated humiliation may require not only remediation, but consequences. We can advocate for a change in classroom or request a 504 Plan if emotional health is affected.

All children learn best and experience success and even joy when the tasks they face are at or slightly beyond their skill level. But with the wide range of abilities, especially for boys, education may need to be individualized. This is very difficult in larger classrooms with fewer resources, too few adult helpers, inexperienced teachers, or high levels of student misbehavior. Basing teacher promotion mainly on standardized test results makes individualizing instruction even less likely. Smaller class size is better; even the recommended (less than 20) or regulated (less than 30) class sizes are associated with suboptimal achievement, compared with smaller ones. Some ways to attain smaller class size include split days or alternate-day sessions, although these also have disadvantages.

While we can advocate for these changes, we can also encourage parents to promote academic skills by talking to and reading to their children of all ages, trying Reach Out and Read for young children, providing counting games, board games, and math songs! Besides screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, we can use standard paragraphs and math problems (for example, WRAT, Einstein) to check skills when performance is low or behavior is a problem the school denies. When concerned, we can write letters for parents to sign requesting testing and an individualized education plan to determine need for tutoring or special education.

While Federal legislation requiring the “least restrictive environment” for education was intended to avoid sidelining differently able children, some can’t learn in a regular class. Conversely, if instruction in a special class is adjusted to the child with the lowest skills, minimal learning may occur for others. Although we can speak with the teacher about “this child’s abilities among those in his class” we can first suggest that the parent visit class to observe. Outside tutoring or home schooling may help a child move up to a regular class.

Sometimes a child’s learning is hampered by classrooms with numerous children misbehaving; this is also a reason for resentment. We can inform school administrators about methods such as The Good Behavior Game (paxis.org) that can improve behavior and connection for the whole class.

While a social “pecking order” is universal, it is unacceptable for children to be allowed to humiliate or hurt a peer, or damage their reputation. While this moral teaching should occur at home, it needs to continue at school where peers are forced into groups they did not choose. Screening for bullying at pediatric visits is now a universal recommendation as 30% report being bullied. We need to ask all children about “mean kids in school” or gang involvement for older children.

Parents can support their children experiencing cyberbullying and switch them to a “dumb phone” with no texting option, limited phone time, or no phone at all. Policies against bullying coming from school administrators are most effective but we can inform schools about the STOPit app for children to report bullying anonymously as well as education for students to stand together against a bully (stopbullying.gov). A Lunch Bunch for younger children or a buddy system for older ones can be requested to help them make friends.

With diverse child aptitudes, schools need to offer students alternative opportunities for self-expression and contribution. We can ask about a child’s strengths and suggest related extracurriculars activities in school or outside, including volunteering. Participation on teams or in clubs must not be blocked for those with poor grades. Perhaps tying participation to tutoring would satisfy the school’s desire to motivate instead. Parents can be encouraged to advocate for music, art, and drama classes – programs that are often victims of budget cuts – that can create the essential school connection.

Students in many areas lack access to classes in trades early enough in their education. The requirements for English or math may be out of reach and result in students dropping out before trade classes are an option. We may identify our patients who may do better with a trade education and advise families to request transfer to a high school offering this.

The best connection a child can have to a school is an adult who values them. The child may identify a preferred teacher to us so that we, or the parent, can call to ask them to provide special attention. Facilitating times for students to get to know teachers may require alteration in bus schedules, lunch times, study halls, or breaks, or keeping the school open longer outside class hours. While more mental health providers are clearly needed, sometimes it is the groundskeeper, the secretary, or the lunch helper who can make the best connection with a child.

As pediatricians, we must listen to struggling youth, acknowledge their pain, and model this empathy for their parents who may be obsessing over grades. Problem-solving about how to get accommodations, informal or formal, can inspire hope. We can coach parents and youth to meet respectfully with the school about issues to avoid labeling the child as a problem.

As pediatricians, our recommendations for school funding and policies may carry extra weight. We may share ideas through talks at PTA meetings, serve on school boards, or endorse leaders planning greater resources for schools to optimize each child’s experience and connection to school.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Schools are intended to be a safe place to acquire knowledge, try out ideas, practice socializing, and build a foundation for adulthood. Many schools fulfill this mission for most children, but for children at both extremes of ability their school experience does not suffice.

When asked, “If you had the choice, would you rather stay home or go to school?” my patients almost universally prefer school. They all know that school is where they should be; they want to be normal, accepted by peers, getting ready for the world’s coming demands, and validation that they will make it as adults. Endorsement otherwise is a warning sign.

When such important tasks of childhood are thwarted children may despair, withdraw, give up, or a small number become furious. These may profoundly resent the children who are experiencing success when they could not. They may hate the teachers and the place where they experienced failure and humiliation. Lack of a positive connection to school characterizes children who are violent toward schools as well as those who drop out.

Schools may fail to support the basic needs of children for many reasons. Schools may avoid physical violence but fail to protect the children’s self-esteem. I have heard stories of teachers calling on children to perform who are clearly struggling or shy, insulting incorrect answers, calling names, putting names on the board, reading out failed grades, posting grades publicly, even allowing peers to mock students. Teachers may deny or disregard parent complaints, or even worsen treatment of the child. Although children may at times falsify complaints, children’s and parents’ reports must be taken seriously and remain anonymous. When we hear of such toxic situations for our patients, we can get details and contact school administrators without naming the child, as often the family feels they can’t. Repeated humiliation may require not only remediation, but consequences. We can advocate for a change in classroom or request a 504 Plan if emotional health is affected.

All children learn best and experience success and even joy when the tasks they face are at or slightly beyond their skill level. But with the wide range of abilities, especially for boys, education may need to be individualized. This is very difficult in larger classrooms with fewer resources, too few adult helpers, inexperienced teachers, or high levels of student misbehavior. Basing teacher promotion mainly on standardized test results makes individualizing instruction even less likely. Smaller class size is better; even the recommended (less than 20) or regulated (less than 30) class sizes are associated with suboptimal achievement, compared with smaller ones. Some ways to attain smaller class size include split days or alternate-day sessions, although these also have disadvantages.

While we can advocate for these changes, we can also encourage parents to promote academic skills by talking to and reading to their children of all ages, trying Reach Out and Read for young children, providing counting games, board games, and math songs! Besides screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, we can use standard paragraphs and math problems (for example, WRAT, Einstein) to check skills when performance is low or behavior is a problem the school denies. When concerned, we can write letters for parents to sign requesting testing and an individualized education plan to determine need for tutoring or special education.

While Federal legislation requiring the “least restrictive environment” for education was intended to avoid sidelining differently able children, some can’t learn in a regular class. Conversely, if instruction in a special class is adjusted to the child with the lowest skills, minimal learning may occur for others. Although we can speak with the teacher about “this child’s abilities among those in his class” we can first suggest that the parent visit class to observe. Outside tutoring or home schooling may help a child move up to a regular class.

Sometimes a child’s learning is hampered by classrooms with numerous children misbehaving; this is also a reason for resentment. We can inform school administrators about methods such as The Good Behavior Game (paxis.org) that can improve behavior and connection for the whole class.

While a social “pecking order” is universal, it is unacceptable for children to be allowed to humiliate or hurt a peer, or damage their reputation. While this moral teaching should occur at home, it needs to continue at school where peers are forced into groups they did not choose. Screening for bullying at pediatric visits is now a universal recommendation as 30% report being bullied. We need to ask all children about “mean kids in school” or gang involvement for older children.

Parents can support their children experiencing cyberbullying and switch them to a “dumb phone” with no texting option, limited phone time, or no phone at all. Policies against bullying coming from school administrators are most effective but we can inform schools about the STOPit app for children to report bullying anonymously as well as education for students to stand together against a bully (stopbullying.gov). A Lunch Bunch for younger children or a buddy system for older ones can be requested to help them make friends.

With diverse child aptitudes, schools need to offer students alternative opportunities for self-expression and contribution. We can ask about a child’s strengths and suggest related extracurriculars activities in school or outside, including volunteering. Participation on teams or in clubs must not be blocked for those with poor grades. Perhaps tying participation to tutoring would satisfy the school’s desire to motivate instead. Parents can be encouraged to advocate for music, art, and drama classes – programs that are often victims of budget cuts – that can create the essential school connection.

Students in many areas lack access to classes in trades early enough in their education. The requirements for English or math may be out of reach and result in students dropping out before trade classes are an option. We may identify our patients who may do better with a trade education and advise families to request transfer to a high school offering this.

The best connection a child can have to a school is an adult who values them. The child may identify a preferred teacher to us so that we, or the parent, can call to ask them to provide special attention. Facilitating times for students to get to know teachers may require alteration in bus schedules, lunch times, study halls, or breaks, or keeping the school open longer outside class hours. While more mental health providers are clearly needed, sometimes it is the groundskeeper, the secretary, or the lunch helper who can make the best connection with a child.

As pediatricians, we must listen to struggling youth, acknowledge their pain, and model this empathy for their parents who may be obsessing over grades. Problem-solving about how to get accommodations, informal or formal, can inspire hope. We can coach parents and youth to meet respectfully with the school about issues to avoid labeling the child as a problem.

As pediatricians, our recommendations for school funding and policies may carry extra weight. We may share ideas through talks at PTA meetings, serve on school boards, or endorse leaders planning greater resources for schools to optimize each child’s experience and connection to school.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Schools are intended to be a safe place to acquire knowledge, try out ideas, practice socializing, and build a foundation for adulthood. Many schools fulfill this mission for most children, but for children at both extremes of ability their school experience does not suffice.

When asked, “If you had the choice, would you rather stay home or go to school?” my patients almost universally prefer school. They all know that school is where they should be; they want to be normal, accepted by peers, getting ready for the world’s coming demands, and validation that they will make it as adults. Endorsement otherwise is a warning sign.

When such important tasks of childhood are thwarted children may despair, withdraw, give up, or a small number become furious. These may profoundly resent the children who are experiencing success when they could not. They may hate the teachers and the place where they experienced failure and humiliation. Lack of a positive connection to school characterizes children who are violent toward schools as well as those who drop out.

Schools may fail to support the basic needs of children for many reasons. Schools may avoid physical violence but fail to protect the children’s self-esteem. I have heard stories of teachers calling on children to perform who are clearly struggling or shy, insulting incorrect answers, calling names, putting names on the board, reading out failed grades, posting grades publicly, even allowing peers to mock students. Teachers may deny or disregard parent complaints, or even worsen treatment of the child. Although children may at times falsify complaints, children’s and parents’ reports must be taken seriously and remain anonymous. When we hear of such toxic situations for our patients, we can get details and contact school administrators without naming the child, as often the family feels they can’t. Repeated humiliation may require not only remediation, but consequences. We can advocate for a change in classroom or request a 504 Plan if emotional health is affected.

All children learn best and experience success and even joy when the tasks they face are at or slightly beyond their skill level. But with the wide range of abilities, especially for boys, education may need to be individualized. This is very difficult in larger classrooms with fewer resources, too few adult helpers, inexperienced teachers, or high levels of student misbehavior. Basing teacher promotion mainly on standardized test results makes individualizing instruction even less likely. Smaller class size is better; even the recommended (less than 20) or regulated (less than 30) class sizes are associated with suboptimal achievement, compared with smaller ones. Some ways to attain smaller class size include split days or alternate-day sessions, although these also have disadvantages.

While we can advocate for these changes, we can also encourage parents to promote academic skills by talking to and reading to their children of all ages, trying Reach Out and Read for young children, providing counting games, board games, and math songs! Besides screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, we can use standard paragraphs and math problems (for example, WRAT, Einstein) to check skills when performance is low or behavior is a problem the school denies. When concerned, we can write letters for parents to sign requesting testing and an individualized education plan to determine need for tutoring or special education.

While Federal legislation requiring the “least restrictive environment” for education was intended to avoid sidelining differently able children, some can’t learn in a regular class. Conversely, if instruction in a special class is adjusted to the child with the lowest skills, minimal learning may occur for others. Although we can speak with the teacher about “this child’s abilities among those in his class” we can first suggest that the parent visit class to observe. Outside tutoring or home schooling may help a child move up to a regular class.

Sometimes a child’s learning is hampered by classrooms with numerous children misbehaving; this is also a reason for resentment. We can inform school administrators about methods such as The Good Behavior Game (paxis.org) that can improve behavior and connection for the whole class.

While a social “pecking order” is universal, it is unacceptable for children to be allowed to humiliate or hurt a peer, or damage their reputation. While this moral teaching should occur at home, it needs to continue at school where peers are forced into groups they did not choose. Screening for bullying at pediatric visits is now a universal recommendation as 30% report being bullied. We need to ask all children about “mean kids in school” or gang involvement for older children.

Parents can support their children experiencing cyberbullying and switch them to a “dumb phone” with no texting option, limited phone time, or no phone at all. Policies against bullying coming from school administrators are most effective but we can inform schools about the STOPit app for children to report bullying anonymously as well as education for students to stand together against a bully (stopbullying.gov). A Lunch Bunch for younger children or a buddy system for older ones can be requested to help them make friends.

With diverse child aptitudes, schools need to offer students alternative opportunities for self-expression and contribution. We can ask about a child’s strengths and suggest related extracurriculars activities in school or outside, including volunteering. Participation on teams or in clubs must not be blocked for those with poor grades. Perhaps tying participation to tutoring would satisfy the school’s desire to motivate instead. Parents can be encouraged to advocate for music, art, and drama classes – programs that are often victims of budget cuts – that can create the essential school connection.

Students in many areas lack access to classes in trades early enough in their education. The requirements for English or math may be out of reach and result in students dropping out before trade classes are an option. We may identify our patients who may do better with a trade education and advise families to request transfer to a high school offering this.

The best connection a child can have to a school is an adult who values them. The child may identify a preferred teacher to us so that we, or the parent, can call to ask them to provide special attention. Facilitating times for students to get to know teachers may require alteration in bus schedules, lunch times, study halls, or breaks, or keeping the school open longer outside class hours. While more mental health providers are clearly needed, sometimes it is the groundskeeper, the secretary, or the lunch helper who can make the best connection with a child.

As pediatricians, we must listen to struggling youth, acknowledge their pain, and model this empathy for their parents who may be obsessing over grades. Problem-solving about how to get accommodations, informal or formal, can inspire hope. We can coach parents and youth to meet respectfully with the school about issues to avoid labeling the child as a problem.

As pediatricians, our recommendations for school funding and policies may carry extra weight. We may share ideas through talks at PTA meetings, serve on school boards, or endorse leaders planning greater resources for schools to optimize each child’s experience and connection to school.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Children and COVID: New cases hold steady in nonholiday week

The new-case count for the most recent reporting week – 87,644 for June 3-9 – did go up from the previous week, but by only 270 cases, the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID report. That’s just 0.31% higher than a week ago and probably is affected by reduced testing and reporting because of Memorial Day, as the AAP and CHA noted earlier.

That hint of a continued decline accompanies the latest trend for new cases for all age groups: They have leveled out over the last month, with the moving 7-day daily average hovering around 100,000-110,000 since mid-May, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The Food and Drug Administration, meanwhile, is in the news this week as two of its advisory panels take the next steps toward pediatric approvals of vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTtech and Moderna. The panels could advance the approvals of the Pfizer vaccine for children under the age of 5 years and the Moderna vaccine for children aged 6 months to 17 years.

Matthew Harris, MD, medical director of the COVID-19 vaccination program for Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., emphasized the importance of vaccinations, as well as the continued challenge of convincing parents to get the shots for eligible children. “We still have a long way to go for primary vaccines and boosters for children 5 years and above,” he said in an interview.

The vaccination effort against COVID-19 has stalled somewhat as interest has waned since the Omicron surge. Weekly initial vaccinations for children aged 5-11 years, which topped 100,000 as recently as mid-March, have been about 43,000 a week for the last 3 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds had around 27,000 or 28,000 initial vaccinations per week over that span, the AAP said in a separate report.

The latest data available from the CDC show that overall vaccine coverage levels for the younger group are only about half those of the 12- to 17-year-olds, both in terms of initial doses and completions. The 5- to 11-year-olds are not eligible for boosters yet, but 26.5% of the older children had received one as of June 13, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The new-case count for the most recent reporting week – 87,644 for June 3-9 – did go up from the previous week, but by only 270 cases, the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID report. That’s just 0.31% higher than a week ago and probably is affected by reduced testing and reporting because of Memorial Day, as the AAP and CHA noted earlier.

That hint of a continued decline accompanies the latest trend for new cases for all age groups: They have leveled out over the last month, with the moving 7-day daily average hovering around 100,000-110,000 since mid-May, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The Food and Drug Administration, meanwhile, is in the news this week as two of its advisory panels take the next steps toward pediatric approvals of vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTtech and Moderna. The panels could advance the approvals of the Pfizer vaccine for children under the age of 5 years and the Moderna vaccine for children aged 6 months to 17 years.

Matthew Harris, MD, medical director of the COVID-19 vaccination program for Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., emphasized the importance of vaccinations, as well as the continued challenge of convincing parents to get the shots for eligible children. “We still have a long way to go for primary vaccines and boosters for children 5 years and above,” he said in an interview.

The vaccination effort against COVID-19 has stalled somewhat as interest has waned since the Omicron surge. Weekly initial vaccinations for children aged 5-11 years, which topped 100,000 as recently as mid-March, have been about 43,000 a week for the last 3 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds had around 27,000 or 28,000 initial vaccinations per week over that span, the AAP said in a separate report.

The latest data available from the CDC show that overall vaccine coverage levels for the younger group are only about half those of the 12- to 17-year-olds, both in terms of initial doses and completions. The 5- to 11-year-olds are not eligible for boosters yet, but 26.5% of the older children had received one as of June 13, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The new-case count for the most recent reporting week – 87,644 for June 3-9 – did go up from the previous week, but by only 270 cases, the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID report. That’s just 0.31% higher than a week ago and probably is affected by reduced testing and reporting because of Memorial Day, as the AAP and CHA noted earlier.

That hint of a continued decline accompanies the latest trend for new cases for all age groups: They have leveled out over the last month, with the moving 7-day daily average hovering around 100,000-110,000 since mid-May, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The Food and Drug Administration, meanwhile, is in the news this week as two of its advisory panels take the next steps toward pediatric approvals of vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTtech and Moderna. The panels could advance the approvals of the Pfizer vaccine for children under the age of 5 years and the Moderna vaccine for children aged 6 months to 17 years.

Matthew Harris, MD, medical director of the COVID-19 vaccination program for Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., emphasized the importance of vaccinations, as well as the continued challenge of convincing parents to get the shots for eligible children. “We still have a long way to go for primary vaccines and boosters for children 5 years and above,” he said in an interview.

The vaccination effort against COVID-19 has stalled somewhat as interest has waned since the Omicron surge. Weekly initial vaccinations for children aged 5-11 years, which topped 100,000 as recently as mid-March, have been about 43,000 a week for the last 3 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds had around 27,000 or 28,000 initial vaccinations per week over that span, the AAP said in a separate report.

The latest data available from the CDC show that overall vaccine coverage levels for the younger group are only about half those of the 12- to 17-year-olds, both in terms of initial doses and completions. The 5- to 11-year-olds are not eligible for boosters yet, but 26.5% of the older children had received one as of June 13, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

A ‘crisis’ of suicidal thoughts, attempts in transgender youth

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

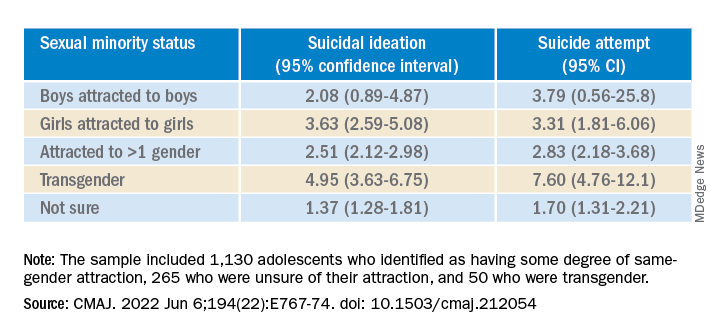

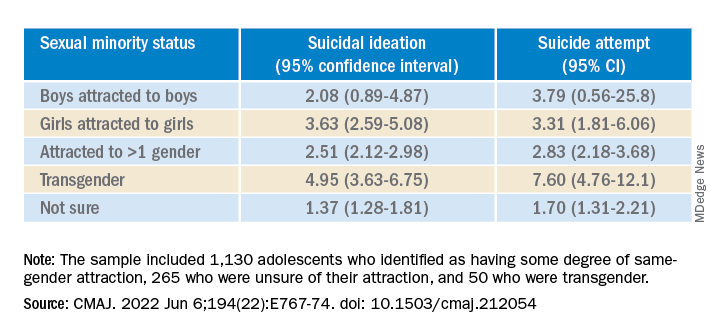

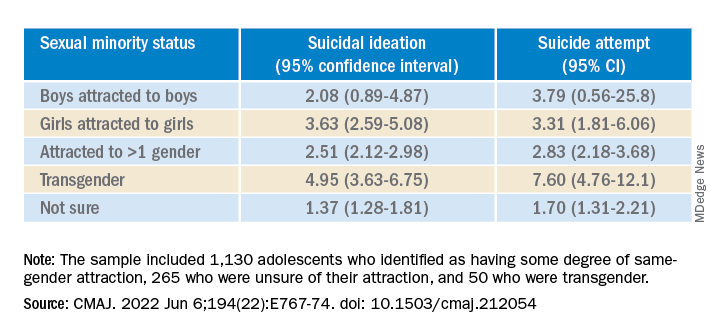

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

New studies show growing number of trans, nonbinary youth in U.S.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In utero COVID exposure tied to neurodevelopmental disorders at 1 year

Infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in utero are at increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in the first year of life, new research suggests.

But whether it is exposure to the pandemic or maternal exposure to the virus itself that may harm early childhood neurodevelopment is unclear, caution investigators, led by Roy Perlis, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“In this analysis of 222 offspring of mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2, compared with the offspring of 7,550 mothers in the control group (not infected) delivered during the same period, we observed neurodevelopmental diagnoses to be significantly more common among exposed offspring, particularly those exposed to third-trimester maternal infection,” they write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Speech and language disorders

The study included 7,772 mostly singleton live births across six hospitals in Massachusetts between March and September 2020, including 222 (2.9%) births to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction testing during pregnancy.

In all, 14 of 222 children born to SARS-CoV-2–infected mothers (6.3%) were diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder in the first year of life versus 227 of 7,550 unexposed offspring (3%) (unadjusted odds ratio, 2.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.24-3.79; P = .006).

In models adjusted for preterm delivery, as well as race, ethnicity, insurance status, child sex, and maternal age, COVID-exposed offspring were significantly more likely to receive a neurodevelopmental diagnosis in the first year of life (adjusted OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.03-3.36; P = .04).

The magnitude of the association with neurodevelopmental disorders was greater with third-trimester SARS-CoV-2 infection (aOR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.23-4.44; P = .01).

The majority of these diagnoses reflected developmental disorders of motor function or speech and language.

The researchers noted that the finding of an association between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months is in line with a “large body of literature” linking maternal viral infection and maternal immune activation with offspring neurodevelopmental disorders later in life.

They cautioned, however, that whether a definitive connection exists between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and adverse neurodevelopment in offspring is not yet known, in part because children born to women infected in the first wave of the pandemic haven’t reached their second birthday – a time when neurodevelopment disorders such as autism are typically diagnosed.

There is also the risk for ascertainment bias arising from greater concern for offspring of infected mothers who were ill during pregnancy. These parents may be more inclined to seek evaluation, and clinicians may be more inclined to diagnose or refer for evaluation, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, as reported by this news organization, the study results support those of research released at the European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress; those results also showed an association between maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and impaired neurodevelopment in 6-week-old infants.

Hypothesis generating

In an accompanying commentary, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, with University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, said the preliminary findings of Dr. Perlis and colleagues are “critically important, yet many questions remain.”

“Essentially all of what we know now about the effects of in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection is from children who were exposed to the early and Alpha variants of SARS-CoV-2, as those are the only children now old enough to undergo rigorous neurodevelopmental assessments,” Dr. Metz pointed out.

Ultimately, Dr. Metz said it’s not surprising that the pandemic and in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection may adversely affect neurodevelopmental outcomes in young children.

Yet, as a retrospective cohort study, the study can only demonstrate associations, not causality.

“This type of work is intended to be hypothesis generating, and that goal has been accomplished as these preliminary findings generate numerous additional research questions to explore,” Dr. Metz wrote.

Among them: Are there genetic predispositions to adverse outcomes? Will we observe differential effects by SARS-CoV-2 variant, by severity of infection, and by trimester of infection? Is it the virus itself or all of the societal changes that occurred during this period, including differences in how those changes were experienced among those with and without SARS-CoV-2?

“Perhaps the most important question is how do we intervene to help mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic on young children,” Dr. Metz noted.

“Prospective studies to validate these findings, tease out some of the nuance, and identify those at highest risk will help health care practitioners appropriately dedicate resources to improve outcomes as we follow the life course of this generation of children born during the COVID-19 pandemic,” she added.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Perlis is an associate editor for JAMA Network Open but was not involved in the editorial review or decision for the study. Dr. Metz reported receiving personal fees and grants from Pfizer and grants from GestVision.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in utero are at increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in the first year of life, new research suggests.

But whether it is exposure to the pandemic or maternal exposure to the virus itself that may harm early childhood neurodevelopment is unclear, caution investigators, led by Roy Perlis, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“In this analysis of 222 offspring of mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2, compared with the offspring of 7,550 mothers in the control group (not infected) delivered during the same period, we observed neurodevelopmental diagnoses to be significantly more common among exposed offspring, particularly those exposed to third-trimester maternal infection,” they write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Speech and language disorders

The study included 7,772 mostly singleton live births across six hospitals in Massachusetts between March and September 2020, including 222 (2.9%) births to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction testing during pregnancy.

In all, 14 of 222 children born to SARS-CoV-2–infected mothers (6.3%) were diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder in the first year of life versus 227 of 7,550 unexposed offspring (3%) (unadjusted odds ratio, 2.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.24-3.79; P = .006).

In models adjusted for preterm delivery, as well as race, ethnicity, insurance status, child sex, and maternal age, COVID-exposed offspring were significantly more likely to receive a neurodevelopmental diagnosis in the first year of life (adjusted OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.03-3.36; P = .04).

The magnitude of the association with neurodevelopmental disorders was greater with third-trimester SARS-CoV-2 infection (aOR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.23-4.44; P = .01).

The majority of these diagnoses reflected developmental disorders of motor function or speech and language.

The researchers noted that the finding of an association between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months is in line with a “large body of literature” linking maternal viral infection and maternal immune activation with offspring neurodevelopmental disorders later in life.

They cautioned, however, that whether a definitive connection exists between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and adverse neurodevelopment in offspring is not yet known, in part because children born to women infected in the first wave of the pandemic haven’t reached their second birthday – a time when neurodevelopment disorders such as autism are typically diagnosed.

There is also the risk for ascertainment bias arising from greater concern for offspring of infected mothers who were ill during pregnancy. These parents may be more inclined to seek evaluation, and clinicians may be more inclined to diagnose or refer for evaluation, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, as reported by this news organization, the study results support those of research released at the European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress; those results also showed an association between maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and impaired neurodevelopment in 6-week-old infants.

Hypothesis generating

In an accompanying commentary, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, with University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, said the preliminary findings of Dr. Perlis and colleagues are “critically important, yet many questions remain.”

“Essentially all of what we know now about the effects of in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection is from children who were exposed to the early and Alpha variants of SARS-CoV-2, as those are the only children now old enough to undergo rigorous neurodevelopmental assessments,” Dr. Metz pointed out.

Ultimately, Dr. Metz said it’s not surprising that the pandemic and in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection may adversely affect neurodevelopmental outcomes in young children.

Yet, as a retrospective cohort study, the study can only demonstrate associations, not causality.

“This type of work is intended to be hypothesis generating, and that goal has been accomplished as these preliminary findings generate numerous additional research questions to explore,” Dr. Metz wrote.

Among them: Are there genetic predispositions to adverse outcomes? Will we observe differential effects by SARS-CoV-2 variant, by severity of infection, and by trimester of infection? Is it the virus itself or all of the societal changes that occurred during this period, including differences in how those changes were experienced among those with and without SARS-CoV-2?

“Perhaps the most important question is how do we intervene to help mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic on young children,” Dr. Metz noted.

“Prospective studies to validate these findings, tease out some of the nuance, and identify those at highest risk will help health care practitioners appropriately dedicate resources to improve outcomes as we follow the life course of this generation of children born during the COVID-19 pandemic,” she added.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Perlis is an associate editor for JAMA Network Open but was not involved in the editorial review or decision for the study. Dr. Metz reported receiving personal fees and grants from Pfizer and grants from GestVision.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in utero are at increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in the first year of life, new research suggests.

But whether it is exposure to the pandemic or maternal exposure to the virus itself that may harm early childhood neurodevelopment is unclear, caution investigators, led by Roy Perlis, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“In this analysis of 222 offspring of mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2, compared with the offspring of 7,550 mothers in the control group (not infected) delivered during the same period, we observed neurodevelopmental diagnoses to be significantly more common among exposed offspring, particularly those exposed to third-trimester maternal infection,” they write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Speech and language disorders

The study included 7,772 mostly singleton live births across six hospitals in Massachusetts between March and September 2020, including 222 (2.9%) births to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction testing during pregnancy.

In all, 14 of 222 children born to SARS-CoV-2–infected mothers (6.3%) were diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder in the first year of life versus 227 of 7,550 unexposed offspring (3%) (unadjusted odds ratio, 2.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.24-3.79; P = .006).

In models adjusted for preterm delivery, as well as race, ethnicity, insurance status, child sex, and maternal age, COVID-exposed offspring were significantly more likely to receive a neurodevelopmental diagnosis in the first year of life (adjusted OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.03-3.36; P = .04).

The magnitude of the association with neurodevelopmental disorders was greater with third-trimester SARS-CoV-2 infection (aOR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.23-4.44; P = .01).

The majority of these diagnoses reflected developmental disorders of motor function or speech and language.

The researchers noted that the finding of an association between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months is in line with a “large body of literature” linking maternal viral infection and maternal immune activation with offspring neurodevelopmental disorders later in life.

They cautioned, however, that whether a definitive connection exists between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and adverse neurodevelopment in offspring is not yet known, in part because children born to women infected in the first wave of the pandemic haven’t reached their second birthday – a time when neurodevelopment disorders such as autism are typically diagnosed.

There is also the risk for ascertainment bias arising from greater concern for offspring of infected mothers who were ill during pregnancy. These parents may be more inclined to seek evaluation, and clinicians may be more inclined to diagnose or refer for evaluation, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, as reported by this news organization, the study results support those of research released at the European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress; those results also showed an association between maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and impaired neurodevelopment in 6-week-old infants.

Hypothesis generating

In an accompanying commentary, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, with University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, said the preliminary findings of Dr. Perlis and colleagues are “critically important, yet many questions remain.”

“Essentially all of what we know now about the effects of in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection is from children who were exposed to the early and Alpha variants of SARS-CoV-2, as those are the only children now old enough to undergo rigorous neurodevelopmental assessments,” Dr. Metz pointed out.

Ultimately, Dr. Metz said it’s not surprising that the pandemic and in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection may adversely affect neurodevelopmental outcomes in young children.

Yet, as a retrospective cohort study, the study can only demonstrate associations, not causality.

“This type of work is intended to be hypothesis generating, and that goal has been accomplished as these preliminary findings generate numerous additional research questions to explore,” Dr. Metz wrote.

Among them: Are there genetic predispositions to adverse outcomes? Will we observe differential effects by SARS-CoV-2 variant, by severity of infection, and by trimester of infection? Is it the virus itself or all of the societal changes that occurred during this period, including differences in how those changes were experienced among those with and without SARS-CoV-2?

“Perhaps the most important question is how do we intervene to help mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic on young children,” Dr. Metz noted.

“Prospective studies to validate these findings, tease out some of the nuance, and identify those at highest risk will help health care practitioners appropriately dedicate resources to improve outcomes as we follow the life course of this generation of children born during the COVID-19 pandemic,” she added.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Perlis is an associate editor for JAMA Network Open but was not involved in the editorial review or decision for the study. Dr. Metz reported receiving personal fees and grants from Pfizer and grants from GestVision.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Stimulants may not improve academic learning in children with ADHD

Extended-release methylphenidate (Concerta) had no effect on learning academic material taught in a small group of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a controlled crossover study found.

As in previous studies, however, the stimulant did improve seat work productivity and classroom behavior, but these benefits did not translate into better learning of individual academic learning units, according to William E. Pelham Jr., PhD, of the department of psychology at Florida International University in Miami, and colleagues.

The results were published online in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

The authors said the finding raises questions about how stimulant medication leads to improved academic achievement over time. “This is important given that many parents and pediatricians believe that medication will improve academic achievement; parents are more likely to pursue medication (vs. other treatment options) when they identify academic achievement as a primary goal for treatment. The current findings suggest this emphasis may be misguided,” they wrote.

In their view, efforts to improve learning in children with ADHD should focus on delivering effective academic instruction and support such as individualized educational plans rather than stimulant therapy.

The study

The study cohort consisted of 173 children aged 7-12 (77% male, 86% Hispanic) who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, criteria for ADHD and were participating in a therapeutic summer camp classroom.

The experimental design was a triple-masked, within-subject, AB/BA crossover trial. Children completed two consecutive phases of daily, 25-minute instruction in both subject-area content (science and social studies) and vocabulary. Each phase was a standard instructional unit lasting for 3 weeks and lessons were given by credentialed teachers via small-group, evidence-based instruction.

Each child was randomized to receive daily osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate (OROS-MPH) during either the first or second instructional phase and to receive placebo during the other.

Seat work referred to the amount of work a pupil completed in a fixed duration of independent work time, and classroom behavior referred to the frequency of violating classroom rules. Learning was measured by tests, and multilevel models were fit separately to the subject and vocabulary test scores, with four observations per child: pretest and posttest in the two academic subject areas.

The results showed that medication had large, salutary, statistically significant effects on children’s academic seat work productivity and classroom behavior on every single day of the instructional period.

Pupils completed 37% more arithmetic problems per minute when taking OROS-MPH and committed 53% fewer rule violations per hour. In terms of learning the material taught during instruction, however, tests showed that children learned the same amount of subject-area and vocabulary content whether they were taking OROS-MPH or placebo during the instructional period.

Consistent with previous studies, medication slightly helped to improve test scores when taken on the day of a test, but not enough to boost most children’s grades. For example, medication helped children increase on average 1.7 percentage points out of 100 on science and social studies tests.