User login

Abatacept appears safe for RA patients with COPD

Concerns about abatacept (Orencia)-related lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis appear to be unfounded, a large U.S. database review has determined.

Safety signals seen in a small subset of patients in the 2006 ASSURE study likely arose from chance, Samy Suissa, PhD, and his colleagues wrote in Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. Patients in that study with preexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were 84% more likely to develop an exacerbation or other lung disorder than were those taking a placebo comparator.

The new database study contradicted that finding.

“Our study suggests that these numerical differences in ASSURE are expected results of random variation and thus compatible with chance,” Dr. Suissa of Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, both in Montreal, and his coauthors wrote. “Moreover, our findings are consistent with two studies of the safety of abatacept in the context of interstitial lung disease, albeit a different respiratory disease than COPD.”

The year-long ASSURE trial reported on the safety of abatacept in 959 patients versus 482 assigned to placebo. The safety signal arose in a subgroup of 54 patients with COPD, 37 of whom were assigned to abatacept and 17 to placebo. Among these were four serious respiratory adverse events (COPD exacerbation, worsening of COPD, bronchitis, and pneumonia) in four patients taking abatacept and none in the placebo arm.

“It is useful to note that this difference of 11% versus 0% rate is compatible with chance [exact P = .31], while the exact 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio is wide and includes unity ... The trial also reported more mild-moderate respiratory events with abatacept than with placebo [43.2% vs. 23.5%], including cough, rhonchi, COPD exacerbation, COPD, dyspnea, and nasal congestion. This difference resulted in an odds ration of 1.84,” with a wide confidence interval that included unity (0.48-8.63).

Nevertheless, these findings led to the addition of a warning in the prescribing insert: “Adult COPD patients treated with Orencia developed adverse events more frequently than those treated with placebo, including COPD exacerbations, cough, rhonchi, and dyspnea. Use of Orencia in patients with RA and COPD should be undertaken with caution and such patients should be monitored for worsening of their respiratory status.”

Dr. Suissa’s team used the U.S. MarketScan prescribing database to asses the risk of respiratory adverse events associated with abatacept, compared with other biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in a real-world setting.

The cohort comprised 1,807 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and COPD who started a new prescription for abatacept, matched in time to 3,547 who initiated another biologic DMARD. The primary endpoint was the combined risk of hospitalization for COPD exacerbation, bronchitis, and hospitalized pneumonia or influenza.

The most common comparator biologic DMARDs were etanercept, adalimumab, rituximab, and infliximab.

For patients with COPD and comparator patients, the incidence rates for COPD exacerbation were 1.2 per 100 person-years with abatacept and 2.1 per 100 person-years with a different biologic DMARD; for bronchitis, the respective rates were 4.2 and 5.3; for hospitalized pneumonia or influenza, 3.6 and 2.6; and for outpatient pneumonia or flu, 14.7 and 14.4. For the combined endpoint, the incidence rate was 8.7 per 100 person-years with abatacept and 9.9 per 100 person-years with other biologic DMARDs.

The adjusted hazard ratio of the combined endpoint with abatacept versus that with other biologic DMARDs was a nonsignificant risk of 0.87. The hazard ratio with abatacept was 0.60 for hospitalized COPD; 0.80 for bronchitis; 1.39 for hospitalized pneumonia and flu; and 1.05 for outpatient pneumonia and flu. None of these associations was statistically significant.

“One exception was the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia or influenza, which was higher with abatacept among patients with more severe COPD,” at 6.99, than it was with other biologic DMARDs, the authors noted.

Dr. Suissa disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Suissa S et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Mar 16. doi: 10.1016j.semarthrit.2019.03.007.

Concerns about abatacept (Orencia)-related lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis appear to be unfounded, a large U.S. database review has determined.

Safety signals seen in a small subset of patients in the 2006 ASSURE study likely arose from chance, Samy Suissa, PhD, and his colleagues wrote in Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. Patients in that study with preexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were 84% more likely to develop an exacerbation or other lung disorder than were those taking a placebo comparator.

The new database study contradicted that finding.

“Our study suggests that these numerical differences in ASSURE are expected results of random variation and thus compatible with chance,” Dr. Suissa of Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, both in Montreal, and his coauthors wrote. “Moreover, our findings are consistent with two studies of the safety of abatacept in the context of interstitial lung disease, albeit a different respiratory disease than COPD.”

The year-long ASSURE trial reported on the safety of abatacept in 959 patients versus 482 assigned to placebo. The safety signal arose in a subgroup of 54 patients with COPD, 37 of whom were assigned to abatacept and 17 to placebo. Among these were four serious respiratory adverse events (COPD exacerbation, worsening of COPD, bronchitis, and pneumonia) in four patients taking abatacept and none in the placebo arm.

“It is useful to note that this difference of 11% versus 0% rate is compatible with chance [exact P = .31], while the exact 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio is wide and includes unity ... The trial also reported more mild-moderate respiratory events with abatacept than with placebo [43.2% vs. 23.5%], including cough, rhonchi, COPD exacerbation, COPD, dyspnea, and nasal congestion. This difference resulted in an odds ration of 1.84,” with a wide confidence interval that included unity (0.48-8.63).

Nevertheless, these findings led to the addition of a warning in the prescribing insert: “Adult COPD patients treated with Orencia developed adverse events more frequently than those treated with placebo, including COPD exacerbations, cough, rhonchi, and dyspnea. Use of Orencia in patients with RA and COPD should be undertaken with caution and such patients should be monitored for worsening of their respiratory status.”

Dr. Suissa’s team used the U.S. MarketScan prescribing database to asses the risk of respiratory adverse events associated with abatacept, compared with other biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in a real-world setting.

The cohort comprised 1,807 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and COPD who started a new prescription for abatacept, matched in time to 3,547 who initiated another biologic DMARD. The primary endpoint was the combined risk of hospitalization for COPD exacerbation, bronchitis, and hospitalized pneumonia or influenza.

The most common comparator biologic DMARDs were etanercept, adalimumab, rituximab, and infliximab.

For patients with COPD and comparator patients, the incidence rates for COPD exacerbation were 1.2 per 100 person-years with abatacept and 2.1 per 100 person-years with a different biologic DMARD; for bronchitis, the respective rates were 4.2 and 5.3; for hospitalized pneumonia or influenza, 3.6 and 2.6; and for outpatient pneumonia or flu, 14.7 and 14.4. For the combined endpoint, the incidence rate was 8.7 per 100 person-years with abatacept and 9.9 per 100 person-years with other biologic DMARDs.

The adjusted hazard ratio of the combined endpoint with abatacept versus that with other biologic DMARDs was a nonsignificant risk of 0.87. The hazard ratio with abatacept was 0.60 for hospitalized COPD; 0.80 for bronchitis; 1.39 for hospitalized pneumonia and flu; and 1.05 for outpatient pneumonia and flu. None of these associations was statistically significant.

“One exception was the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia or influenza, which was higher with abatacept among patients with more severe COPD,” at 6.99, than it was with other biologic DMARDs, the authors noted.

Dr. Suissa disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Suissa S et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Mar 16. doi: 10.1016j.semarthrit.2019.03.007.

Concerns about abatacept (Orencia)-related lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis appear to be unfounded, a large U.S. database review has determined.

Safety signals seen in a small subset of patients in the 2006 ASSURE study likely arose from chance, Samy Suissa, PhD, and his colleagues wrote in Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. Patients in that study with preexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were 84% more likely to develop an exacerbation or other lung disorder than were those taking a placebo comparator.

The new database study contradicted that finding.

“Our study suggests that these numerical differences in ASSURE are expected results of random variation and thus compatible with chance,” Dr. Suissa of Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, both in Montreal, and his coauthors wrote. “Moreover, our findings are consistent with two studies of the safety of abatacept in the context of interstitial lung disease, albeit a different respiratory disease than COPD.”

The year-long ASSURE trial reported on the safety of abatacept in 959 patients versus 482 assigned to placebo. The safety signal arose in a subgroup of 54 patients with COPD, 37 of whom were assigned to abatacept and 17 to placebo. Among these were four serious respiratory adverse events (COPD exacerbation, worsening of COPD, bronchitis, and pneumonia) in four patients taking abatacept and none in the placebo arm.

“It is useful to note that this difference of 11% versus 0% rate is compatible with chance [exact P = .31], while the exact 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio is wide and includes unity ... The trial also reported more mild-moderate respiratory events with abatacept than with placebo [43.2% vs. 23.5%], including cough, rhonchi, COPD exacerbation, COPD, dyspnea, and nasal congestion. This difference resulted in an odds ration of 1.84,” with a wide confidence interval that included unity (0.48-8.63).

Nevertheless, these findings led to the addition of a warning in the prescribing insert: “Adult COPD patients treated with Orencia developed adverse events more frequently than those treated with placebo, including COPD exacerbations, cough, rhonchi, and dyspnea. Use of Orencia in patients with RA and COPD should be undertaken with caution and such patients should be monitored for worsening of their respiratory status.”

Dr. Suissa’s team used the U.S. MarketScan prescribing database to asses the risk of respiratory adverse events associated with abatacept, compared with other biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in a real-world setting.

The cohort comprised 1,807 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and COPD who started a new prescription for abatacept, matched in time to 3,547 who initiated another biologic DMARD. The primary endpoint was the combined risk of hospitalization for COPD exacerbation, bronchitis, and hospitalized pneumonia or influenza.

The most common comparator biologic DMARDs were etanercept, adalimumab, rituximab, and infliximab.

For patients with COPD and comparator patients, the incidence rates for COPD exacerbation were 1.2 per 100 person-years with abatacept and 2.1 per 100 person-years with a different biologic DMARD; for bronchitis, the respective rates were 4.2 and 5.3; for hospitalized pneumonia or influenza, 3.6 and 2.6; and for outpatient pneumonia or flu, 14.7 and 14.4. For the combined endpoint, the incidence rate was 8.7 per 100 person-years with abatacept and 9.9 per 100 person-years with other biologic DMARDs.

The adjusted hazard ratio of the combined endpoint with abatacept versus that with other biologic DMARDs was a nonsignificant risk of 0.87. The hazard ratio with abatacept was 0.60 for hospitalized COPD; 0.80 for bronchitis; 1.39 for hospitalized pneumonia and flu; and 1.05 for outpatient pneumonia and flu. None of these associations was statistically significant.

“One exception was the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia or influenza, which was higher with abatacept among patients with more severe COPD,” at 6.99, than it was with other biologic DMARDs, the authors noted.

Dr. Suissa disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Suissa S et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Mar 16. doi: 10.1016j.semarthrit.2019.03.007.

FROM SEMINARS IN ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Powerful breast-implant testimony constrained by limited evidence

What’s the role of anecdotal medical histories in the era of evidence-based medicine?

But the anecdotal histories fell short of producing a clear committee consensus on dramatic, immediate changes in FDA policy, such as joining a renewed ban on certain types of breast implants linked with a rare lymphoma, a step recently taken by 38 other countries, including 33 European countries acting in concert through the European Union.

The disconnect between gripping testimony and limited panel recommendations was most stark for a complication that’s been named Breast Implant Illness (BII) by patients on the Internet. Many breast implant recipients have reported life-changing symptoms that appeared after implant placement, most often fatigue, joint and muscle pain, brain fog, neurologic symptoms, immune dysfunction, skin manifestations, and autoimmune disease or symptoms. By my count, 22 people spoke about their harrowing experiences with BII symptoms out of the 77 who stepped to the panel’s public-comment mic during 4 hours of public testimony over 2-days of hearings, often saying that they had experienced dramatic improvements after their implants came out. The meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee also heard presentations from two experts who ran some of the first reported studies on BII, or a BII-like syndrome called Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) described by Jan W.C. Tervaert, MD, professor of medicine and director of rheumatology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Tervaert and his associates published their findings about ASIA in the rheumatology literature last year (Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Feb;37[2]:483-93), and during his talk before the FDA panel, he said that silicone breast implants and the surgical mesh often used with them could be ASIA triggers.

Panel members seemed to mostly believe that the evidence they heard about BII did no more than hint at a possible association between breast implants and BII symptoms that required additional study. Many agreed on the need to include mention of the most common BII-linked patient complaints in informed consent material, but some were reluctant about even taking that step.

“I do not mention BII to patients. It’s not a disease; it’s a constellation of symptoms,” said panel member and plastic surgeon Pierre M. Chevray, MD, from Houston Methodist Hospital. The evidence for BII “is extremely anecdotal,” he said in an interview at the end of the 2-day session. Descriptions of BII “have been mainly published on social media. One reason why I don’t tell patients [about BII as part of informed consent] is because right now the evidence of a link is weak. We don’t yet even have a definition of this as an illness. A first step is to define it,” said Dr. Chevray, who has a very active implant practice. Other plastic surgeons were more accepting of BII as a real complication, although they agreed it needs much more study. During the testimony period, St. Louis plastic surgeon Patricia A. McGuire, MD, highlighted the challenge of teasing apart whether real symptoms are truly related to implants or are simply common ailments that accumulate during middle-age in many women. Dr. McGuire and some of her associates published an assessment of the challenges and possible solutions to studying BII that appeared shortly before the hearing (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:74S-81S),

Consensus recommendations from the panel to the FDA to address BII included having a single registry that would include all U.S. patients who receive breast implants (recently launched as the National Breast Implant Registry), inclusion of a control group, and collection of data at baseline and after regular follow-up intervals that includes a variety of measures relevant to autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders. Several panel members cited inadequate postmarketing safety surveillance by manufacturers in the years since breast implants returned to the U.S. market, and earlier in March, the FDA issued warning letters to two of the four companies that market U.S. breast implants over their inadequate long-term safety follow-up.

The panel’s decisions about the other major implant-associated health risk it considered, breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), faced a different sort of challenge. First described as linked to breast implants in 2011, today there is little doubt that BIA-ALCL is a consequence of breast implants, what several patients derisively called a “man-made cancer.” The key issue the committee grappled with was whether the calculated incidence of BIA-ALCL was at a frequency that warranted a ban on at least selected breast implant types. Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, told the panel that he calculated the Allergan Biocell group of implants, which have textured surfaces that allows for easier and more stable placement in patients, linked with an incidence of BIA-ALCL that was sevenfold to eightfold higher than that with smooth implants. That’s against a background of an overall incidence of about one case for every 20,000 U.S. implant recipients, Dr. Clemens said.

Many testifying patients, including several of the eight who described a personal history of BIA-ALCL, called for a ban on the sale of at least some breast implants because of their role in causing lymphoma. That sentiment was shared by Dr. Chevray, who endorsed a ban on “salt-loss” implants (the method that makes Biocell implants) during his closing comments to his fellow panel members. But earlier during panel discussions, others on the committee pushed back against implant bans, leaving the FDA’s eventual decision on this issue unclear. Evidence presented during the hearings suggests that implants cause ALCL by triggering a local “inflammatory milieu” and that different types of implants can have varying levels of potency for producing this milieu.

Perhaps the closest congruence between what patients called for and what the committee recommended was on informed consent. “No doubt, patients feel that informed consent failed them,” concluded panel member Karen E. Burke, MD, a New York dermatologist who was one of two panel discussants for the topic.

In addition to many suggestions on how to improve informed consent and public awareness lobbed at FDA staffers during the session by panel members, the final public comment of the 2 days came from Laurie A. Casas, MD, a Chicago plastic surgeon affiliated with the University of Chicago and a member of the board of directors of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (also know as the Aesthetic Society). During her testimony, Dr. Casas said “Over the past 2 days, we heard that patients need a structured educational checklist for informed consent. The Aesthetic Society hears you,” and promised that the website of the Society’s publication, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, will soon feature a safety checklist for people receiving breast implants that will get updated as new information becomes available. She also highlighted the need for a comprehensive registry and long-term follow-up of implant recipients by the plastic surgeons who treated them.

In addition to better informed consent, patients who came to the hearing clearly also hoped to raise awareness in the general American public about the potential dangers from breast implants and the need to follow patients who receive implants. The 2 days of hearing accomplished that in part just by taking place. The New York Times and The Washington Post ran at least a couple of articles apiece on implant safety just before or during the hearings, while a more regional paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ran one article, as presumably did many other newspapers, broadcast outlets, and websites across America. Much of the coverage focused on compelling and moving personal stories from patients.

Women who have been having adverse effects from breast implants “have felt dismissed,” noted panel member Natalie C. Portis, PhD, a clinical psychologist from Oakland, Calif., and the patient representative on the advisory committee. “We need to listen to women that something real is happening.”

Dr. Tervaert, Dr. Chevray, Dr. McGuire, Dr. Clemens, Dr. Burke, Dr. Casas, and Dr. Portis had no relevant commercial disclosures.

What’s the role of anecdotal medical histories in the era of evidence-based medicine?

But the anecdotal histories fell short of producing a clear committee consensus on dramatic, immediate changes in FDA policy, such as joining a renewed ban on certain types of breast implants linked with a rare lymphoma, a step recently taken by 38 other countries, including 33 European countries acting in concert through the European Union.

The disconnect between gripping testimony and limited panel recommendations was most stark for a complication that’s been named Breast Implant Illness (BII) by patients on the Internet. Many breast implant recipients have reported life-changing symptoms that appeared after implant placement, most often fatigue, joint and muscle pain, brain fog, neurologic symptoms, immune dysfunction, skin manifestations, and autoimmune disease or symptoms. By my count, 22 people spoke about their harrowing experiences with BII symptoms out of the 77 who stepped to the panel’s public-comment mic during 4 hours of public testimony over 2-days of hearings, often saying that they had experienced dramatic improvements after their implants came out. The meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee also heard presentations from two experts who ran some of the first reported studies on BII, or a BII-like syndrome called Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) described by Jan W.C. Tervaert, MD, professor of medicine and director of rheumatology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Tervaert and his associates published their findings about ASIA in the rheumatology literature last year (Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Feb;37[2]:483-93), and during his talk before the FDA panel, he said that silicone breast implants and the surgical mesh often used with them could be ASIA triggers.

Panel members seemed to mostly believe that the evidence they heard about BII did no more than hint at a possible association between breast implants and BII symptoms that required additional study. Many agreed on the need to include mention of the most common BII-linked patient complaints in informed consent material, but some were reluctant about even taking that step.

“I do not mention BII to patients. It’s not a disease; it’s a constellation of symptoms,” said panel member and plastic surgeon Pierre M. Chevray, MD, from Houston Methodist Hospital. The evidence for BII “is extremely anecdotal,” he said in an interview at the end of the 2-day session. Descriptions of BII “have been mainly published on social media. One reason why I don’t tell patients [about BII as part of informed consent] is because right now the evidence of a link is weak. We don’t yet even have a definition of this as an illness. A first step is to define it,” said Dr. Chevray, who has a very active implant practice. Other plastic surgeons were more accepting of BII as a real complication, although they agreed it needs much more study. During the testimony period, St. Louis plastic surgeon Patricia A. McGuire, MD, highlighted the challenge of teasing apart whether real symptoms are truly related to implants or are simply common ailments that accumulate during middle-age in many women. Dr. McGuire and some of her associates published an assessment of the challenges and possible solutions to studying BII that appeared shortly before the hearing (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:74S-81S),

Consensus recommendations from the panel to the FDA to address BII included having a single registry that would include all U.S. patients who receive breast implants (recently launched as the National Breast Implant Registry), inclusion of a control group, and collection of data at baseline and after regular follow-up intervals that includes a variety of measures relevant to autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders. Several panel members cited inadequate postmarketing safety surveillance by manufacturers in the years since breast implants returned to the U.S. market, and earlier in March, the FDA issued warning letters to two of the four companies that market U.S. breast implants over their inadequate long-term safety follow-up.

The panel’s decisions about the other major implant-associated health risk it considered, breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), faced a different sort of challenge. First described as linked to breast implants in 2011, today there is little doubt that BIA-ALCL is a consequence of breast implants, what several patients derisively called a “man-made cancer.” The key issue the committee grappled with was whether the calculated incidence of BIA-ALCL was at a frequency that warranted a ban on at least selected breast implant types. Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, told the panel that he calculated the Allergan Biocell group of implants, which have textured surfaces that allows for easier and more stable placement in patients, linked with an incidence of BIA-ALCL that was sevenfold to eightfold higher than that with smooth implants. That’s against a background of an overall incidence of about one case for every 20,000 U.S. implant recipients, Dr. Clemens said.

Many testifying patients, including several of the eight who described a personal history of BIA-ALCL, called for a ban on the sale of at least some breast implants because of their role in causing lymphoma. That sentiment was shared by Dr. Chevray, who endorsed a ban on “salt-loss” implants (the method that makes Biocell implants) during his closing comments to his fellow panel members. But earlier during panel discussions, others on the committee pushed back against implant bans, leaving the FDA’s eventual decision on this issue unclear. Evidence presented during the hearings suggests that implants cause ALCL by triggering a local “inflammatory milieu” and that different types of implants can have varying levels of potency for producing this milieu.

Perhaps the closest congruence between what patients called for and what the committee recommended was on informed consent. “No doubt, patients feel that informed consent failed them,” concluded panel member Karen E. Burke, MD, a New York dermatologist who was one of two panel discussants for the topic.

In addition to many suggestions on how to improve informed consent and public awareness lobbed at FDA staffers during the session by panel members, the final public comment of the 2 days came from Laurie A. Casas, MD, a Chicago plastic surgeon affiliated with the University of Chicago and a member of the board of directors of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (also know as the Aesthetic Society). During her testimony, Dr. Casas said “Over the past 2 days, we heard that patients need a structured educational checklist for informed consent. The Aesthetic Society hears you,” and promised that the website of the Society’s publication, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, will soon feature a safety checklist for people receiving breast implants that will get updated as new information becomes available. She also highlighted the need for a comprehensive registry and long-term follow-up of implant recipients by the plastic surgeons who treated them.

In addition to better informed consent, patients who came to the hearing clearly also hoped to raise awareness in the general American public about the potential dangers from breast implants and the need to follow patients who receive implants. The 2 days of hearing accomplished that in part just by taking place. The New York Times and The Washington Post ran at least a couple of articles apiece on implant safety just before or during the hearings, while a more regional paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ran one article, as presumably did many other newspapers, broadcast outlets, and websites across America. Much of the coverage focused on compelling and moving personal stories from patients.

Women who have been having adverse effects from breast implants “have felt dismissed,” noted panel member Natalie C. Portis, PhD, a clinical psychologist from Oakland, Calif., and the patient representative on the advisory committee. “We need to listen to women that something real is happening.”

Dr. Tervaert, Dr. Chevray, Dr. McGuire, Dr. Clemens, Dr. Burke, Dr. Casas, and Dr. Portis had no relevant commercial disclosures.

What’s the role of anecdotal medical histories in the era of evidence-based medicine?

But the anecdotal histories fell short of producing a clear committee consensus on dramatic, immediate changes in FDA policy, such as joining a renewed ban on certain types of breast implants linked with a rare lymphoma, a step recently taken by 38 other countries, including 33 European countries acting in concert through the European Union.

The disconnect between gripping testimony and limited panel recommendations was most stark for a complication that’s been named Breast Implant Illness (BII) by patients on the Internet. Many breast implant recipients have reported life-changing symptoms that appeared after implant placement, most often fatigue, joint and muscle pain, brain fog, neurologic symptoms, immune dysfunction, skin manifestations, and autoimmune disease or symptoms. By my count, 22 people spoke about their harrowing experiences with BII symptoms out of the 77 who stepped to the panel’s public-comment mic during 4 hours of public testimony over 2-days of hearings, often saying that they had experienced dramatic improvements after their implants came out. The meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee also heard presentations from two experts who ran some of the first reported studies on BII, or a BII-like syndrome called Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) described by Jan W.C. Tervaert, MD, professor of medicine and director of rheumatology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Tervaert and his associates published their findings about ASIA in the rheumatology literature last year (Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Feb;37[2]:483-93), and during his talk before the FDA panel, he said that silicone breast implants and the surgical mesh often used with them could be ASIA triggers.

Panel members seemed to mostly believe that the evidence they heard about BII did no more than hint at a possible association between breast implants and BII symptoms that required additional study. Many agreed on the need to include mention of the most common BII-linked patient complaints in informed consent material, but some were reluctant about even taking that step.

“I do not mention BII to patients. It’s not a disease; it’s a constellation of symptoms,” said panel member and plastic surgeon Pierre M. Chevray, MD, from Houston Methodist Hospital. The evidence for BII “is extremely anecdotal,” he said in an interview at the end of the 2-day session. Descriptions of BII “have been mainly published on social media. One reason why I don’t tell patients [about BII as part of informed consent] is because right now the evidence of a link is weak. We don’t yet even have a definition of this as an illness. A first step is to define it,” said Dr. Chevray, who has a very active implant practice. Other plastic surgeons were more accepting of BII as a real complication, although they agreed it needs much more study. During the testimony period, St. Louis plastic surgeon Patricia A. McGuire, MD, highlighted the challenge of teasing apart whether real symptoms are truly related to implants or are simply common ailments that accumulate during middle-age in many women. Dr. McGuire and some of her associates published an assessment of the challenges and possible solutions to studying BII that appeared shortly before the hearing (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:74S-81S),

Consensus recommendations from the panel to the FDA to address BII included having a single registry that would include all U.S. patients who receive breast implants (recently launched as the National Breast Implant Registry), inclusion of a control group, and collection of data at baseline and after regular follow-up intervals that includes a variety of measures relevant to autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders. Several panel members cited inadequate postmarketing safety surveillance by manufacturers in the years since breast implants returned to the U.S. market, and earlier in March, the FDA issued warning letters to two of the four companies that market U.S. breast implants over their inadequate long-term safety follow-up.

The panel’s decisions about the other major implant-associated health risk it considered, breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), faced a different sort of challenge. First described as linked to breast implants in 2011, today there is little doubt that BIA-ALCL is a consequence of breast implants, what several patients derisively called a “man-made cancer.” The key issue the committee grappled with was whether the calculated incidence of BIA-ALCL was at a frequency that warranted a ban on at least selected breast implant types. Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, told the panel that he calculated the Allergan Biocell group of implants, which have textured surfaces that allows for easier and more stable placement in patients, linked with an incidence of BIA-ALCL that was sevenfold to eightfold higher than that with smooth implants. That’s against a background of an overall incidence of about one case for every 20,000 U.S. implant recipients, Dr. Clemens said.

Many testifying patients, including several of the eight who described a personal history of BIA-ALCL, called for a ban on the sale of at least some breast implants because of their role in causing lymphoma. That sentiment was shared by Dr. Chevray, who endorsed a ban on “salt-loss” implants (the method that makes Biocell implants) during his closing comments to his fellow panel members. But earlier during panel discussions, others on the committee pushed back against implant bans, leaving the FDA’s eventual decision on this issue unclear. Evidence presented during the hearings suggests that implants cause ALCL by triggering a local “inflammatory milieu” and that different types of implants can have varying levels of potency for producing this milieu.

Perhaps the closest congruence between what patients called for and what the committee recommended was on informed consent. “No doubt, patients feel that informed consent failed them,” concluded panel member Karen E. Burke, MD, a New York dermatologist who was one of two panel discussants for the topic.

In addition to many suggestions on how to improve informed consent and public awareness lobbed at FDA staffers during the session by panel members, the final public comment of the 2 days came from Laurie A. Casas, MD, a Chicago plastic surgeon affiliated with the University of Chicago and a member of the board of directors of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (also know as the Aesthetic Society). During her testimony, Dr. Casas said “Over the past 2 days, we heard that patients need a structured educational checklist for informed consent. The Aesthetic Society hears you,” and promised that the website of the Society’s publication, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, will soon feature a safety checklist for people receiving breast implants that will get updated as new information becomes available. She also highlighted the need for a comprehensive registry and long-term follow-up of implant recipients by the plastic surgeons who treated them.

In addition to better informed consent, patients who came to the hearing clearly also hoped to raise awareness in the general American public about the potential dangers from breast implants and the need to follow patients who receive implants. The 2 days of hearing accomplished that in part just by taking place. The New York Times and The Washington Post ran at least a couple of articles apiece on implant safety just before or during the hearings, while a more regional paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ran one article, as presumably did many other newspapers, broadcast outlets, and websites across America. Much of the coverage focused on compelling and moving personal stories from patients.

Women who have been having adverse effects from breast implants “have felt dismissed,” noted panel member Natalie C. Portis, PhD, a clinical psychologist from Oakland, Calif., and the patient representative on the advisory committee. “We need to listen to women that something real is happening.”

Dr. Tervaert, Dr. Chevray, Dr. McGuire, Dr. Clemens, Dr. Burke, Dr. Casas, and Dr. Portis had no relevant commercial disclosures.

Rituximab does not improve fatigue symptoms of ME/CFS

according to results from the phase 3 RituxME trial.

“The lack of clinical effect of B-cell depletion in this trial weakens the case for an important role of B lymphocytes in ME/CFS but does not exclude an immunologic basis,” Øystein Fluge, MD, PhD, of the department of oncology and medical physics at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, and his colleagues wrote April 1 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The investigators noted that the basis for testing the effects of a B-cell–depleting intervention on clinical symptoms in patients with ME/CFS came from observations of its potential benefit in a subgroup of patients in previous studies. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues performed a three-patient case series in their own group that found benefit for patients who received rituximab for treatment of CFS (BMC Neurol. 2009 May 8;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-28). A phase 2 trial of 30 patients with CFS also performed by his own group found improved fatigue scores in 66.7% of patients in the rituximab group, compared with placebo (PLOS One. 2011 Oct 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026358).

In the double-blinded RituxME trial, 151 patients with ME/CFS from four university hospitals and one general hospital in Norway were recruited and randomized to receive infusions of rituximab (n = 77) or placebo (n = 74). The patients were aged 18-65 years old and had the disease ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Patients reported and rated their ME/CFS symptoms at baseline as well as completed forms for the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, and modified DePaul Symptom Questionnaire out to 24 months. The rituximab group received two infusions at 500 mg/m2 across body surface area at 2 weeks apart. They then received 500-mg maintenance infusions at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months where they also self-reported changes in ME/CFS symptoms.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fatigue score at any follow-up period, with an average between-group difference of 0.02 at 24 months (95% confidence interval, –0.27 to 0.31). The overall response rate was 26% with rituximab and 35% with placebo. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues also noted no significant differences regarding SF-36 scores, function level, and fatigue severity between groups.

Adverse event rates were higher in the rituximab group (63 patients; 82%) than in the placebo group (48 patients; 65%), and these were more often attributed to treatment for those taking rituximab (26 patients [34%]) than for placebo (12 patients [16%]). Adverse events requiring hospitalization also occurred more often among those taking rituximab (31 events in 20 patients [26%]) than for those who took placebo (16 events in 14 patients [19%]).

Some of the weaknesses of the trial included its use of self-referral and self-reported symptom scores, which might have been subject to recall bias. In commenting on the difference in outcome between the phase 3 trial and others, Dr. Fluge and his associates said the discrepancy could potentially be high expectations in the placebo group, unknown factors surrounding symptom variation in ME/CFS patients, and unknown patient selection effects.

“[T]he negative outcome of RituxME should spur research to assess patient subgroups and further elucidate disease mechanisms, of which recently disclosed impairment of energy metabolism may be important,” Dr. Fluge and his coauthors wrote.

The trial was funded by grants to the researchers from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Regional Health Trusts, the MEandYou Foundation, the Norwegian ME Association, and the legacy of Torstein Hereid.

SOURCE: Fluge Ø et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M18-1451

The RituxME trial’s results weaken the case for the use of rituximab to treat myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but there are opportunities to test other treatments targeting immunologic abnormalities in ME/CFS, Peter C. Rowe, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a related editorial.

“Persons with ME/CFS often meet criteria for several comorbid conditions, each of which could flare during a trial, possibly obscuring a true beneficial effect of an intervention,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Trials with open treatment periods, in which ME/CFS patients all receive rituximab and then are grouped based on nontargeted conditions, could be warranted to “allow better control” of these conditions. Other trial designs could include randomizing patients to continue or discontinue therapy for responders, he added.

“The profound level of impaired function of affected individuals warrants a new commitment to hypothesis-driven clinical trials that incorporate and expand on the methodological sophistication of the rituximab trial,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Dr. Rowe is with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments summarize his editorial in response to Fluge et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0643). Dr. Rowe reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and is a scientific advisory board member for Solve ME/CFS, all outside the submitted work.

The RituxME trial’s results weaken the case for the use of rituximab to treat myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but there are opportunities to test other treatments targeting immunologic abnormalities in ME/CFS, Peter C. Rowe, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a related editorial.

“Persons with ME/CFS often meet criteria for several comorbid conditions, each of which could flare during a trial, possibly obscuring a true beneficial effect of an intervention,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Trials with open treatment periods, in which ME/CFS patients all receive rituximab and then are grouped based on nontargeted conditions, could be warranted to “allow better control” of these conditions. Other trial designs could include randomizing patients to continue or discontinue therapy for responders, he added.

“The profound level of impaired function of affected individuals warrants a new commitment to hypothesis-driven clinical trials that incorporate and expand on the methodological sophistication of the rituximab trial,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Dr. Rowe is with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments summarize his editorial in response to Fluge et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0643). Dr. Rowe reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and is a scientific advisory board member for Solve ME/CFS, all outside the submitted work.

The RituxME trial’s results weaken the case for the use of rituximab to treat myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but there are opportunities to test other treatments targeting immunologic abnormalities in ME/CFS, Peter C. Rowe, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a related editorial.

“Persons with ME/CFS often meet criteria for several comorbid conditions, each of which could flare during a trial, possibly obscuring a true beneficial effect of an intervention,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Trials with open treatment periods, in which ME/CFS patients all receive rituximab and then are grouped based on nontargeted conditions, could be warranted to “allow better control” of these conditions. Other trial designs could include randomizing patients to continue or discontinue therapy for responders, he added.

“The profound level of impaired function of affected individuals warrants a new commitment to hypothesis-driven clinical trials that incorporate and expand on the methodological sophistication of the rituximab trial,” Dr. Rowe wrote.

Dr. Rowe is with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments summarize his editorial in response to Fluge et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0643). Dr. Rowe reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and is a scientific advisory board member for Solve ME/CFS, all outside the submitted work.

according to results from the phase 3 RituxME trial.

“The lack of clinical effect of B-cell depletion in this trial weakens the case for an important role of B lymphocytes in ME/CFS but does not exclude an immunologic basis,” Øystein Fluge, MD, PhD, of the department of oncology and medical physics at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, and his colleagues wrote April 1 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The investigators noted that the basis for testing the effects of a B-cell–depleting intervention on clinical symptoms in patients with ME/CFS came from observations of its potential benefit in a subgroup of patients in previous studies. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues performed a three-patient case series in their own group that found benefit for patients who received rituximab for treatment of CFS (BMC Neurol. 2009 May 8;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-28). A phase 2 trial of 30 patients with CFS also performed by his own group found improved fatigue scores in 66.7% of patients in the rituximab group, compared with placebo (PLOS One. 2011 Oct 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026358).

In the double-blinded RituxME trial, 151 patients with ME/CFS from four university hospitals and one general hospital in Norway were recruited and randomized to receive infusions of rituximab (n = 77) or placebo (n = 74). The patients were aged 18-65 years old and had the disease ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Patients reported and rated their ME/CFS symptoms at baseline as well as completed forms for the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, and modified DePaul Symptom Questionnaire out to 24 months. The rituximab group received two infusions at 500 mg/m2 across body surface area at 2 weeks apart. They then received 500-mg maintenance infusions at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months where they also self-reported changes in ME/CFS symptoms.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fatigue score at any follow-up period, with an average between-group difference of 0.02 at 24 months (95% confidence interval, –0.27 to 0.31). The overall response rate was 26% with rituximab and 35% with placebo. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues also noted no significant differences regarding SF-36 scores, function level, and fatigue severity between groups.

Adverse event rates were higher in the rituximab group (63 patients; 82%) than in the placebo group (48 patients; 65%), and these were more often attributed to treatment for those taking rituximab (26 patients [34%]) than for placebo (12 patients [16%]). Adverse events requiring hospitalization also occurred more often among those taking rituximab (31 events in 20 patients [26%]) than for those who took placebo (16 events in 14 patients [19%]).

Some of the weaknesses of the trial included its use of self-referral and self-reported symptom scores, which might have been subject to recall bias. In commenting on the difference in outcome between the phase 3 trial and others, Dr. Fluge and his associates said the discrepancy could potentially be high expectations in the placebo group, unknown factors surrounding symptom variation in ME/CFS patients, and unknown patient selection effects.

“[T]he negative outcome of RituxME should spur research to assess patient subgroups and further elucidate disease mechanisms, of which recently disclosed impairment of energy metabolism may be important,” Dr. Fluge and his coauthors wrote.

The trial was funded by grants to the researchers from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Regional Health Trusts, the MEandYou Foundation, the Norwegian ME Association, and the legacy of Torstein Hereid.

SOURCE: Fluge Ø et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M18-1451

according to results from the phase 3 RituxME trial.

“The lack of clinical effect of B-cell depletion in this trial weakens the case for an important role of B lymphocytes in ME/CFS but does not exclude an immunologic basis,” Øystein Fluge, MD, PhD, of the department of oncology and medical physics at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, and his colleagues wrote April 1 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The investigators noted that the basis for testing the effects of a B-cell–depleting intervention on clinical symptoms in patients with ME/CFS came from observations of its potential benefit in a subgroup of patients in previous studies. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues performed a three-patient case series in their own group that found benefit for patients who received rituximab for treatment of CFS (BMC Neurol. 2009 May 8;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-28). A phase 2 trial of 30 patients with CFS also performed by his own group found improved fatigue scores in 66.7% of patients in the rituximab group, compared with placebo (PLOS One. 2011 Oct 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026358).

In the double-blinded RituxME trial, 151 patients with ME/CFS from four university hospitals and one general hospital in Norway were recruited and randomized to receive infusions of rituximab (n = 77) or placebo (n = 74). The patients were aged 18-65 years old and had the disease ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Patients reported and rated their ME/CFS symptoms at baseline as well as completed forms for the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, and modified DePaul Symptom Questionnaire out to 24 months. The rituximab group received two infusions at 500 mg/m2 across body surface area at 2 weeks apart. They then received 500-mg maintenance infusions at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months where they also self-reported changes in ME/CFS symptoms.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fatigue score at any follow-up period, with an average between-group difference of 0.02 at 24 months (95% confidence interval, –0.27 to 0.31). The overall response rate was 26% with rituximab and 35% with placebo. Dr. Fluge and his colleagues also noted no significant differences regarding SF-36 scores, function level, and fatigue severity between groups.

Adverse event rates were higher in the rituximab group (63 patients; 82%) than in the placebo group (48 patients; 65%), and these were more often attributed to treatment for those taking rituximab (26 patients [34%]) than for placebo (12 patients [16%]). Adverse events requiring hospitalization also occurred more often among those taking rituximab (31 events in 20 patients [26%]) than for those who took placebo (16 events in 14 patients [19%]).

Some of the weaknesses of the trial included its use of self-referral and self-reported symptom scores, which might have been subject to recall bias. In commenting on the difference in outcome between the phase 3 trial and others, Dr. Fluge and his associates said the discrepancy could potentially be high expectations in the placebo group, unknown factors surrounding symptom variation in ME/CFS patients, and unknown patient selection effects.

“[T]he negative outcome of RituxME should spur research to assess patient subgroups and further elucidate disease mechanisms, of which recently disclosed impairment of energy metabolism may be important,” Dr. Fluge and his coauthors wrote.

The trial was funded by grants to the researchers from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Regional Health Trusts, the MEandYou Foundation, the Norwegian ME Association, and the legacy of Torstein Hereid.

SOURCE: Fluge Ø et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.7326/M18-1451

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Click for Credit: Suicide in Medicaid youth; persistent back pain; more

Here are 5 articles from the April issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Back pain persists in one in five patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Uiod8N

Expires January 14, 2019

2. COPD linked to higher in-hospital death rates in patients with PAD

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TFCeJC

Expires January 22, 2019

3. Medicaid youth suicides include more females, younger kids, hanging deaths

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Uleyyp

Expires January 17, 2019

4. Potential antidepressant overprescribing found in 24% of elderly cohort

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HWwcSq

Expires January 24, 2019

5. Perceptions of liver transplantation for ALD are evolving

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCANuA

Expires January 22, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the April issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Back pain persists in one in five patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Uiod8N

Expires January 14, 2019

2. COPD linked to higher in-hospital death rates in patients with PAD

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TFCeJC

Expires January 22, 2019

3. Medicaid youth suicides include more females, younger kids, hanging deaths

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Uleyyp

Expires January 17, 2019

4. Potential antidepressant overprescribing found in 24% of elderly cohort

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HWwcSq

Expires January 24, 2019

5. Perceptions of liver transplantation for ALD are evolving

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCANuA

Expires January 22, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the April issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Back pain persists in one in five patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Uiod8N

Expires January 14, 2019

2. COPD linked to higher in-hospital death rates in patients with PAD

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TFCeJC

Expires January 22, 2019

3. Medicaid youth suicides include more females, younger kids, hanging deaths

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Uleyyp

Expires January 17, 2019

4. Potential antidepressant overprescribing found in 24% of elderly cohort

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HWwcSq

Expires January 24, 2019

5. Perceptions of liver transplantation for ALD are evolving

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCANuA

Expires January 22, 2019

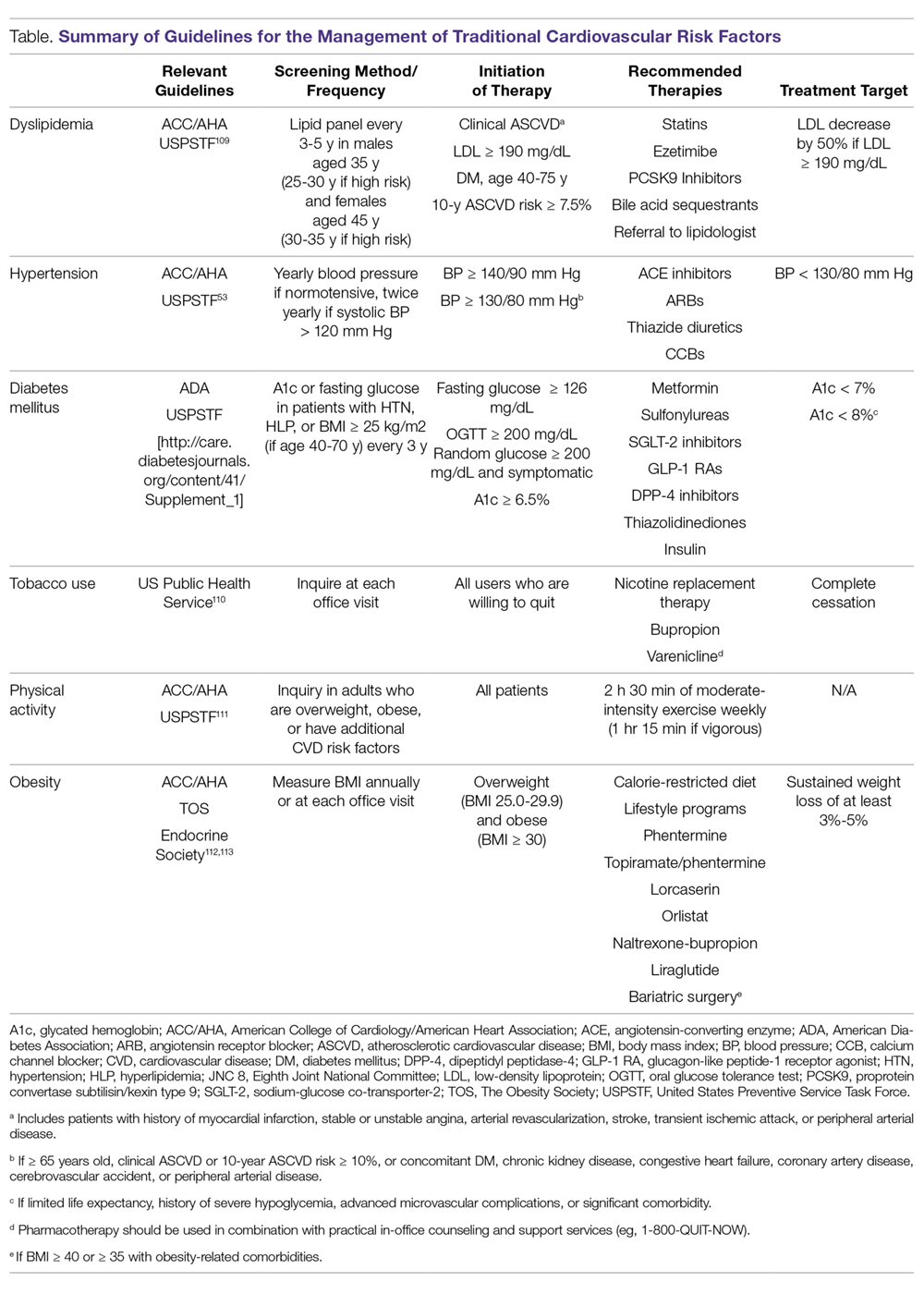

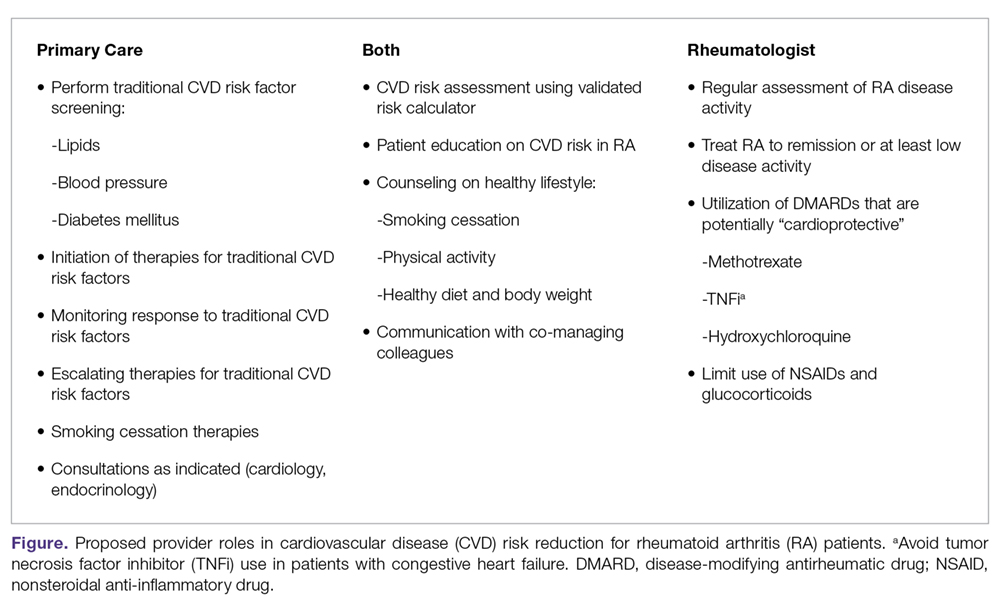

Management of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis

From the Division of Rh

Abstract

- Objective: To review the management of traditional and nontraditional CVD cardiovascular disease risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

- Methods: Literature review of the management of CVD risk in RA.

- Results: Because of the increased risk of CVD events and CVD mortality among RA patients, aggressive management of CVD risk is essential. Providers should follow national guidelines for the management of traditional CVD risk factors, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Similar efforts are needed in counseling on lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation, regular exercise, and maintaining a healthy body weight. Because higher RA disease activity is also linked with CVD risk, aggressive treatment of RA to a target of low disease activity or remission is critical. Furthermore, the selection of potentially “cardioprotective” agents such as methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, while limiting use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and glucocorticoids, are strategies that could be employed by rheumatologists to help mitigate CVD risk in their patients with RA.

- Conclusion: Routine assessment of CVD risk, management of traditional CVD risk factors, counseling on healthy lifestyle habits, and aggressive treatment of RA are essential to minimize CVD risk in this population.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis; cardiovascular disease; cardiovascular risk assessment; cardiovascular risk management.

Editor’s note: This article is part 2 of a 2-part article. “Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis” was published in the January/February 2019 issue.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune condition that contributes to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) among affected patients. In persons with RA, the risk of incident CVD and CVD mortality are increased by approximately 50% compared with the general population.1,2 To minimize CVD risk in this population, providers must routinely assess for CVD risk factors3 and aggressively manage both traditional and nontraditional CVD risk factors.

Managing Traditional Risk Factors

As in the general population, identification and management of traditional CVD risk factors are crucial to minimize CVD risk in the RA population. A prospective study of 201 RA patients demonstrated that traditional CVD risk factors were in fact more predictive of endothelial dysfunction and carotid atherosclerosis than were disease-related inflammatory markers in RA.4 Management of traditional risk factors is detailed in the following sections, and recommendations for managing all traditional CVD risk factors are summarized in the Table.

Dyslipidemia

The role of dyslipidemia in atherogenesis is well established, and as a result, lipid levels are nearly universally included in CVD risk stratification tools. However, the interpretation of lipid levels in the context of RA is challenging because of the effects of systemic inflammation on their absolute values. Compared to the general population, patients with RA have lower total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels independent of lipid-lowering therapy.5,6 Despite this, RA patients are at increased risk for CVD. There is even some evidence to suggest a “lipid paradox” in RA, whereby lower TC (< 4 mmol/L) and LDL levels suggest an increased risk of CVD.7,8 In contrast to LDL, higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) are typically associated with reduced CVD risk, as in the general population.8,9 Interestingly, in a cohort of 16,085 RA patients and 48,499 age- and sex-matched controls, there was no significant difference in the relationship between LDL and CVD risk, suggesting that quantitative lipid levels alone may not entirely explain the CVD mortality gap in RA.9 As such, there is substantial interest in lipoprotein function within the context of CVD risk in RA. Recent investigations have identified impaired HDL function, with reduced cholesterol efflux capacity and antioxidant properties, as well as increased scavenger receptor expression and foam cell formation, in patients with RA.10,11 More research is needed to elucidate how these alterations affect CVD morbidity and mortality and how their measurement could be integrated into improved CVD risk assessment.

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have estimated that lipid-lowering therapy with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) reduces the risk of CVD by 25% to 30%; as such, statin therapy has become the standard of care for reduction of CVD risk in the general population.12 Benefits for primary prevention of CVD in RA have also been observed; statin therapy was associated with a reduced risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.20-0.98) and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.20-0.92) in a population-based cohort study.13 Statins appear to have similar lipid-lowering effects and result in similar CVD risk reduction when used for primary or secondary prevention in RA patients compared to non-RA controls.14-16 Additionally, anti-inflammatory properties of statins may act in synergy with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) to improve RA disease activity. In a small study of RA patients, statin therapy improved subjective and objective markers of RA disease activity in conjunction with methotrexate.17

While statins provide robust reduction in CVD risk, some individuals cannot tolerate statin therapy or do not achieve goal LDL levels with statin therapy. Select non-statin LDL-cholesterol-lowering agents have shown promise for reducing CVD events in the general population.18 Ezetimibe, which inhibits cholesterol absorption in the small intestine, very modestly reduced CVD events when added to atorvastatin (relative risk [RR], 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99) in a double-blind randomized controlled trial.19 Novel monoclonal antibodies to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK-9) inhibit the internalization of surface LDL receptors, promoting LDL clearance. Two PCSK-9 inhibitors, alirocumab and evolocumab, were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after randomized controlled trials demonstrated their efficacy in lowering LDL by approximately 60% and reducing CVD events by approximately 15% in patients on maximum-tolerated statin therapy.20-22 To date, non-statin LDL-cholesterol-lowering agents have been subject to limited study in RA.23

Identification and management of dyslipidemia offers an opportunity for substantial CVD risk reduction at the RA population level. Unfortunately, current rates of lipid screening are inadequate in this high-risk group. In a study of 3298 Medicare patients with RA, less than half of RA patients with an indication underwent appropriate lipid screening.24 Additionally, statins are often underutilized for both primary and secondary prevention in RA patients. Only 27% of RA patients meeting National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria were initiated on statin therapy in a population-based cohort study.25 Among patients discharged after a first myocardial infarction (MI), the odds of receiving lipid-lowering therapy were 31% lower for RA patients (odds ratio [OR], 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.82).26 Similar to the general population, adherence to statins in RA patients appears to be poor.27-30 This raises particular concern considering that a population-based cohort study of RA patients demonstrated a 67% increased risk of MI associated with statin discontinuation, regardless of prior MI status.27 Providers—rheumatologists, primary care providers, and cardiologists alike—need to remain vigilant in efforts to assess CVD risk to identify patients who will benefit from lipid-lowering therapy and to emphasize the importance to patients of statin adherence. Novel models of health-care delivery, health technologies, and patient engagement in care may prove useful for improving lipid screening and management in RA.

Tobacco Use

Cigarette smoking is a shared risk factor for both CVD and RA. Large cohort studies have identified a dose-dependent increased risk of incident RA, particularly seropositive RA, among smokers.31-34 Tobacco smoking has also been associated with increased levels of inflammation and RA disease activity.35 The consequences of tobacco use in the general population are staggering. Among individuals over the age of 30 years, tobacco use is responsible for 12% of all deaths and 10% of all CVD deaths.36 Similar findings are observed in RA; a recent meta-analysis estimated there is a 50% increased risk of CVD events in RA related to smoking tobacco.37 In the general population, smoking cessation markedly lowers CVD risk, and over time CVD risk may approach that of nonsmokers.38,39 Thus, regular counseling and interventions to facilitate smoking cessation are critical to reducing CVD risk in RA patients. RA-specific smoking cessation programs have been proposed, but have yet to outperform standard smoking cessation programs.40

Diabetes Mellitus

It is estimated that almost 10% of the US population has diabetes mellitus (DM), which in isolation portends substantial CVD risk.41 There is an increased prevalence of DM in RA, perhaps owing to factors such as physical inactivity and chronic glucocorticoid use, though a higher level of RA disease activity itself has been associated with increased insulin resistance.42-45 In a cohort of 100 RA patients who were neither obese nor diabetic, RA patients had significantly higher fasting blood glucose and insulin levels than age- and sex-matched controls. These findings were even more pronounced in RA patients with higher levels of disease activity.44 Similar to the general population, DM is associated with poor CVD outcomes in RA.37 Therefore, both appropriate management of diabetes and control of RA disease activity are vitally important to minimize CVD risk related to DM.

Hypertension

Though not a universal finding, there may be an increased prevalence of hypertension in RA patients.31,46 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and glucocorticoid use may play a role in the development of hypertension, while DMARDs appear to exert a less substantial effect on blood pressure.47,48 At least one study found that DMARD initiation (particularly for methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine) was associated with significant, albeit small, declines in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure over the first 6 months of treatment.49

Despite its potentially higher prevalence in this population, hypertension is both underdiagnosed and undertreated in RA patients.24,50-52 This is an important deficiency to target because, as in the general population, hypertension is associated with an increased risk of MI (RR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.38-2.46) and composite CVD outcomes (RR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.42-3.06) in RA.37 Thresholds for initiation and escalation of antihypertensive therapy are not specific to the RA population; thus, diagnosis and management of hypertension should be informed by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, treating those with in-office blood pressures exceeding 140/90 mm Hg (> 130/80 mm Hg if aged > 65 years or with concomitant CVD, DM, chronic kidney disease, or 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk > 10%), typically with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, or thiazide diuretics as comorbidities may dictate or allow.53 Also, the use of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids should be minimized, particularly in those with concomitant hypertension.

Physical Activity

Likely due to factors such as articular pain and stiffness, as well as physical limitations, RA patients are more sedentary than the general population.54,55 In a study of objectively assessed sedentary behavior in RA patients, greater average sedentary time per day and greater number of sedentary bouts (> 20 min) were associated with increased 10-year risk of CVD as assessed by the QRISK2.56 Conversely, the beneficial effects of exercise are well documented. Light to moderate physical activity has been associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes, greater physical function, higher levels of HDL, as well as reduced systemic inflammation and disease activity, and improved endothelial function in RA patients.57-61 While there has been concern that physical activity may result in accelerated joint damage, even high-intensity exercise was shown to be safe without causing significant progression of joint damage.58

Obesity, Weight Loss, and Diet

While obesity is clearly associated with CVD risk in the general population, this relationship is much more complex in RA, as underweight RA patients are also at higher risk for CVD and CVD-related mortality.62-64 One potential explanation for this finding is that pathological weight loss resulting in an underweight body mass index (BMI) is an independent predictor of CVD. In a study of US Veterans with RA, higher rates of weight loss (> 3 kg/m2/year) were associated with increased CVD mortality (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.61-3.19) independent of BMI.65 Systemic inflammation in RA can lead to “rheumatoid cachexia,” characterized by decreased muscle mass, increased adiposity, and increased CVD risk despite a normal or potentially decreased BMI.66 Practitioners should be mindful of not only current body weight, but also patients’ weight trajectories when counseling on lifestyle practices such as healthy diet and regular exercise in RA patients. For obese individuals with RA, healthy weight loss should be encouraged. Interestingly, bariatric surgery in RA patients may improve RA disease activity in addition to its known effects on body weight and DM.67

Counseling on healthy diet with a focus on limiting foods high in saturated- and trans-fatty acids and high glycemic index foods, and increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, and mono-unsaturated fatty acids is a well-accepted and common practice to help minimize CVD risk in the general population.68 No studies to date have investigated the effect of specific diets on CVD risk in RA patients, and thus we recommend adherence to general population recommendations.

Managing RA-related CVD Risk Factors

Disease Activity

In addition to traditional risk factors, several studies have identified associations between the level of RA disease activity and risk of CVD. In a cohort of US Veterans with RA, CVD-related mortality increased in a dose-dependent manner with higher disease activity categories. In stark contrast, the CVD mortality rates of those in remission paralleled the rates from the general population (standardized mortality ratio [SMR], 0.68; 95% CI, 0.37-1.27).69 In a separate cohort of 1157 RA patients without prior CVD, achieving low disease activity was associated with a lower risk of incident CVD events (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.43-0.99).70 Additionally, high disease activity has been associated with surrogate markers of CVD and other CVD risk factors including NT-proBNP and systolic blood pressure.71,72 While no randomized controlled trial data is available to inform this recommendation, observational data suggest RA should be aggressively treated (ideally to achieve and maintain remission or low disease activity) to minimize CVD risk. While keeping this treatment goal in mind, the differential effects of specific RA therapies on CVD must also be considered.

Glucocorticoids and NSAIDs

With the expanding repertoire of DMARDs available and more aggressive treatment approaches, the role of glucocorticoids and NSAIDs in RA treatment is decreasing over time. While their efficacy for improving pain and stiffness is well established, concern regarding their contribution to CVD risk in RA patients is warranted.

Glucocorticoids are known to have detrimental effects on traditional CVD risk factors such as hypertension, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia in the general population, as well as in RA patients.73,74 In a meta-analysis of predominantly observational studies of RA patients, glucocorticoid use was associated with an increased risk of CVD events (RR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.34-1.60), including MI, congestive heart failure (CHF), and cerebrovascular accident (CVA).75 Evidence is conflicting in regards to a clear dose threshold that leads to increased CVD risk with glucocorticoids, though higher doses are associated with greater risk.76-81 As RA patients requiring glucocorticoids typically have higher disease activity, confounding by indication remains a complicating factor in assessing the relative contributions of glucocorticoid use and RA disease activity to elevated CVD risk in many analyses.

The increased CVD risk with NSAID use is not specific to RA and has been well established in the general population.82-84 In the previously mentioned meta-analysis, an increased overall risk of CVD events was observed with NSAID use in RA (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01-1.38). It should be noted that cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors, in particular rofecoxib (now removed from the market), appeared to drive the majority of this risk (RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.10-1.67 in COX-2 inhibitors and RR 1.08, 95% CI, 0.94-1.24 in nonselective NSAIDs), suggesting a potential differential risk among NSAIDs.75 While naproxen has been thought to carry the lowest risk of CVD based on initial studies, this has not been universally observed, including in a recent randomized controlled trial of more than 24,000 RA and osteoarthritis patients.82,85,86

Providers should use the lowest possible dose and duration of glucocorticoids and NSAIDs to achieve symptom relief, with continual efforts to taper or discontinue. Candidates for glucocorticoid and NSAID therapy should be selected carefully, and use of these therapies should be avoided in those with prior CVD or at high risk for CVD based on traditional CVD risk factors. Most importantly, providers should focus on utilizing DMARDs for the management of RA, which more effectively treat RA as well as reduce CVD risk.

Methotrexate

Methotrexate (MTX), a mainstay in the treatment of RA, is a conventional DMARD observed to improve overall survival and mitigate CVD risk in multiple RA cohorts.75,87,88 In a recent meta-analysis comprised of 236,525 RA patients and 5410 CVD events, MTX use was associated with a 28% reduction in overall CVD events across 8 studies (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.91), substantiating similar findings in a prior meta-analysis.75,88 MTX use was specifically associated with a decreased risk of MI (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.96). Case-control and cohort studies have cited a 20% to 50% reduced risk of CHF with MTX use.89,90 The potential cardioprotective effect of MTX appears to be both multifactorial and complex, likely mediated through both direct and indirect mechanisms. MTX directly promotes anti-atherogenic lipoprotein function, improves endothelial function, and scavenges free radicals.91,92 Indirectly, MTX likely reduces CVD risk by effectively reducing RA disease activity. Based on these and other data, MTX remains the cornerstone of DMARD therapy in RA patients when targeting CVD risk reduction.

Hydroxychloroquine

Emerging evidence suggests that hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an antimalarial most often utilized in combination with alternative DMARDs in RA, prevents DM and has beneficial effects on lipid profiles. A recent meta-analysis compiled 3 homogenous observational studies that investigated the effect of HCQ on incident DM. RA patients ever exposed to HCQ had a 40% lower incidence of DM (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.49-0.70).93 Increased duration of HCQ use was shown to further reduce risk of incident DM.94 The aforementioned meta-analysis also pooled 5 studies investigating the effect of HCQ on lipid profiles, with favorable mean differences in TC (–9.82 mg/dL), LDL (–10.61 mg/dL), HDL (4.13 mg/dL), and triglycerides (–19.15 mg/dL) in HCQ users compared to non-users.93 Given these favorable changes to traditional CVD risk factors, it is not surprising that in a retrospective study of 1266 RA patients without prior CVD, HCQ was associated with significantly lower risk of incident CVD. While external validation of these findings is needed, HCQ is an attractive conventional DMARD to be used in RA for CVD risk reduction. Moreover, its combination with MTX and sulfasalazine also shows promise for CVD risk reduction.95,96

TNF Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are often the initial biologic DMARD therapy used in RA patients not responding to conventional DMARDs. In the previously described meta-analysis, TNF inhibitors were associated with similar reductions in CVD events as MTX (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54-0.90).75 Of note, there was a trend toward reduced risk of CHF (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.49-1.15) in this same meta-analysis, an area of concern with TNF inhibitor use due to a prior randomized controlled trial demonstrating worsening clinical status in patients with existing moderate-to-severe CHF treated with high-dose infliximab.97 Current RA treatment guidelines recommend avoiding TNF inhibitor use in individuals with CHF.98

Aside from the risk of CHF exacerbation, TNF inhibitors appear to be cardioprotective. Similar to MTX, the mechanism by which TNF inhibition reduces cardiovascular risk is complex and likely due to both direct and indirect mechanisms. Substantial research has been conducted on the effect of TNF inhibition on lipids, with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating increases in HDL and TC, with stable LDL and atherogenic index over treatment follow-up.99 A subsequent meta-analysis not limited to RA patients yielded similar results.100 In addition to quantitative lipid changes, alteration of lipoprotein function, improvement in myocardial function, reduced aortic stiffness, improved blood pressure, and reduced RA disease activity may also be responsible for cardioprotective benefits of these agents.101,102