User login

2019 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

Keeping current with causes of and treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is important. AUB can have a major impact on women’s lives in terms of health care expenses, productivity, and quality of life. The focus of this Update is on information that has been published over the past year that is helpful for clinicians who counsel and treat women with AUB. First, we focus on new data on endometrial polyps, which are a common cause of AUB. For the first time, a meta-analysis has examined polyp-associated cancer risk. In addition, does a causal relationship exist between endometrial polyps and chronic endometritis? We also address the first published report of successful treatment of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN, formerly complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia) using the etonogestrel subdermal implant. Last, we discuss efficacy data for a new device for endometrial ablation, which has new features to consider.

What is the risk of malignancy with endometrial polyps?

Sasaki LM, Andrade KR, Figeuiredo AC, et al. Factors associated with malignancy in hysteroscopically resected endometrial polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:777-785.

In the past year, 2 studies have contributed to our understanding of endometrial polyps, with one published as the first ever meta-analysis on polyp risk of malignancy.

What can information from more than 21,000 patients with polyps teach us about the risk factors associated with endometrial malignancy? For instance, with concern over balancing health care costs with potential surgical risks, should all patients with endometrial polyps undergo routine surgical removal, or should we stratify risks and offer surgery to only selected patients? This is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the risk factors for endometrial cancer (such as obesity, parity, tamoxifen use, and hormonal therapy use) in patients with endometrial polyps.

Risk factors for and prevalence of malignancy

Sasaki and colleagues found that about 3 of every 100 patients with recognized polyps will harbor a premalignant or malignant lesion (3.4%; 716 of 21,057 patients). The identified risk factors for a cancerous polyp included: menopausal status, age greater than 60 years, presence of AUB, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and tamoxifen use. The risk for cancer was 2-fold greater in women older than 60 years compared with those younger than age 60 (prevalence ratio, 2.41). The authors found no risk association with use of combination hormone therapy, parity, breast cancer, or polyp size.

The investigators advised caution with using their conclusions, as there was high heterogeneity for some of the factors studied (including age, AUB, parity, and hypertension).

The study takeaways regarding clinical and demographic risk factors suggest that menopausal status, age greater than 60 years, the presence of AUB, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and tamoxifen use have an increased risk for premalignant and malignant lesions.

This study is important because its findings will better enable physicians to inform and counsel patients about the risks for malignancy associated with endometrial polyps, which will better foster discussion and joint decision-making about whether or not surgery should be performed.

New evidence associates endometrial polyps with chronic endometritis

The second important study published this year on polyps was conducted by Cicinelli and colleagues and suggests that inflammation may be part of the pathophysiology behind the common problem of polyps. The authors cite a recent study that showed that abnormal expression of "local" paracrine inflammatory mediators, such as interferon-gamma, may enhance the proliferation of endometrial mucosa.1 Building on this possibility further, they hypothesized that chronic endometrial inflammation may affect the pathogenesis of endometrial polyps.

Details of the study

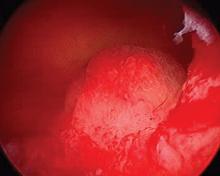

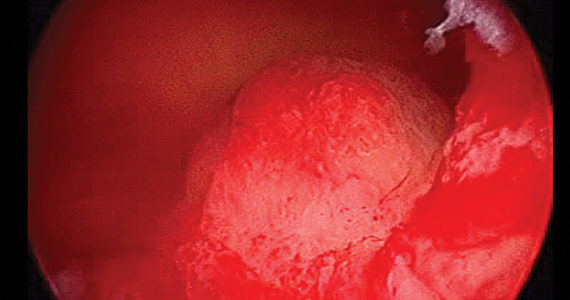

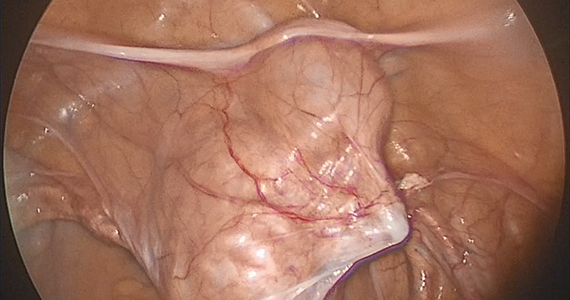

To investigate the possible correlation between polyps and chronic endometritis, Cicinelli and colleagues compared the endometrial biopsies of 240 women with AUB and hysteroscopically and histologically diagnosed endometrial polyps with 240 women with AUB and no polyp seen on hysteroscopy. The tissue samples were evaluated with immunohistochemistry for CD-138 for plasma cell identification.

The study authors found a significantly higher prevalence of chronic endometritis in the group with endometrial polyps than in the group without polyps (61.7% vs 24.2%, respectively; P <.0001). They suggest that this evidence supports the hypothesis that endometrial polyps may be a result of endometrial proliferation and vasculopathy triggered by chronic endometritis.

The significance of this study is that there is a possible causal relationship between endometrial polyps and chronic endometritis, which may expand the options for endometrial polyp therapy beyond surgical management in the future.

Continue to: Can endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia be treated with the etonogestrel subdermal implant?

Can endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia be treated with the etonogestrel subdermal implant?

Wong S, Naresh A. Etonogestrel subdermal implant-associated regression of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:780-782.

Recently, Wong and Naresh gave us the first case report of successful treatment of EIN using the etonogestrel subdermal implant. With so many other options available to treat EIN, some of which have been studied extensively, why should we take note of this study? First, the authors point out the risk of endometrial cancer development among patients with EIN, and they acknowledge the standard recommendation of hysterectomy in women with EIN who have finished childbearing and are appropriate candidates for a surgical approach. There is also concern about lower serum etonogestrel levels in obese patients. In this case, the patient (aged 36 with obesity) had been nonadherent with oral progestin therapy and stated that she would not adhere to daily oral therapy. She also declined hysterectomy, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device therapy, and injectable progestin therapy after being counseled about the risk of malignancy development. She consented to subdermal etonogestrel as an alternative to no therapy.

EIN regressed. Endometrial biopsies at 4 and 8 months showed regression of EIN, and at 16 months after implantation (as well as a dilation and curettage at 9 months) demonstrated an inactive endometrium with no sign of hyperplasia.

The authors remain cautious about recommending the etonogestrel subdermal implant as a first-line therapy for EIN, but the implant was reported to be effective in this case that involved a patient with obesity. In cases in which surgery or other medical options for EIN are not feasible, the etonogestrel subdermal implant is reasonable to consider. Its routine use for EIN management warrants future study.

New endometrial ablation technology shows promising benefits

Do we need another endometrial ablation device? Are there improvements that can be made to our existing technology? There already are several endometrial ablation devices, using varying technology, that currently are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of AUB. The devices use bipolar radiofrequency, cryotherapy, circulating hot fluid, and combined thermal and radiofrequency modalities. Additional devices, employing heated balloon and microwaves, are no longer used. Data on a new device, approved by the FDA in 2017 (the AEGEA Vapor System, called Mara), were recently published.

Details of the study

Levie and colleagues conducted a prospective pivotal trial on Mara's safety and effectiveness. The benefits presented by the authors include that the device 1) does not require that an intrauterine array be deployed up to and abutting the fundus and cornu, 2) does not necessitate cervical dilatation, 3) is a free-flowing vapor system that can navigate differences in uterine contour and sizes (up to 12 cm in length), and 4) accomplishes ablation in 2 minutes. So there are indeed some novel features of this device.

This pivotal study was a multicenter trial using objective performance criterion (OPC), which is based on using the average success rates across the 5 FDA-approved ablation devices as historic controls. In the study an OPC of 66% correlated to the lower bound of the 95% confidence intervals. The primary outcome of the study was effectiveness in the reduction of blood loss using a pictorial blood loss assessment score (PBLAS) of less than 75. Of note, a PBLAS of 150 was a study entry criterion. FIGO types 2 through 6 fibroids were included in the trial. Secondary endpoints were quality of life and patient satisfaction as assessed by the Menorrhagia Impact Questionnaire and the Aberdeen Menorrhagia Severity Score, as well as the need to intervene medically or surgically to treat AUB in the first 12 months after ablation.

Efficacy, satisfaction, and quality of life results

At 12 months, the primary effectiveness end point was achieved in 78.7% of study participants. The satisfaction rate was 90.8% (satisfied or very satisfied), and 99% of participants showed improvement in quality of life scores. There were no reported serious adverse events.

The takeaway is that the AEGEA device appears to be effective for endometrial ablation and offers the novel features of not relying on an intrauterine array to be deployed up to and abutting the fundus and cornu, not necessitating cervical dilatation in all cases, and offering a free-flowing vapor system that can navigate differences in uterine contour and sizes quickly (approximately 2 minutes).

The fact that new devices for endometrial ablation are still being developed is encouraging, and it suggests that endometrial ablation technology can be improved. Although AEGEA's Mara system is not yet commercially available, it is anticipated that it will be available at the start of 2020. The ability to treat large uteri (up to 12-cm cavities) with FIGO type 2 to 6 fibroids with less cervical dilatation makes the device attractive and perhaps well suited for office use.

- Mollo A, Stile A, Alviggi C, et al. Endometrial polyps in infertile patients: do high concentrations of interferon-gamma play a role? Fertil Steril. 2011:96:1209-1212.

Keeping current with causes of and treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is important. AUB can have a major impact on women’s lives in terms of health care expenses, productivity, and quality of life. The focus of this Update is on information that has been published over the past year that is helpful for clinicians who counsel and treat women with AUB. First, we focus on new data on endometrial polyps, which are a common cause of AUB. For the first time, a meta-analysis has examined polyp-associated cancer risk. In addition, does a causal relationship exist between endometrial polyps and chronic endometritis? We also address the first published report of successful treatment of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN, formerly complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia) using the etonogestrel subdermal implant. Last, we discuss efficacy data for a new device for endometrial ablation, which has new features to consider.

What is the risk of malignancy with endometrial polyps?

Sasaki LM, Andrade KR, Figeuiredo AC, et al. Factors associated with malignancy in hysteroscopically resected endometrial polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:777-785.

In the past year, 2 studies have contributed to our understanding of endometrial polyps, with one published as the first ever meta-analysis on polyp risk of malignancy.

What can information from more than 21,000 patients with polyps teach us about the risk factors associated with endometrial malignancy? For instance, with concern over balancing health care costs with potential surgical risks, should all patients with endometrial polyps undergo routine surgical removal, or should we stratify risks and offer surgery to only selected patients? This is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the risk factors for endometrial cancer (such as obesity, parity, tamoxifen use, and hormonal therapy use) in patients with endometrial polyps.

Risk factors for and prevalence of malignancy

Sasaki and colleagues found that about 3 of every 100 patients with recognized polyps will harbor a premalignant or malignant lesion (3.4%; 716 of 21,057 patients). The identified risk factors for a cancerous polyp included: menopausal status, age greater than 60 years, presence of AUB, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and tamoxifen use. The risk for cancer was 2-fold greater in women older than 60 years compared with those younger than age 60 (prevalence ratio, 2.41). The authors found no risk association with use of combination hormone therapy, parity, breast cancer, or polyp size.

The investigators advised caution with using their conclusions, as there was high heterogeneity for some of the factors studied (including age, AUB, parity, and hypertension).

The study takeaways regarding clinical and demographic risk factors suggest that menopausal status, age greater than 60 years, the presence of AUB, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and tamoxifen use have an increased risk for premalignant and malignant lesions.

This study is important because its findings will better enable physicians to inform and counsel patients about the risks for malignancy associated with endometrial polyps, which will better foster discussion and joint decision-making about whether or not surgery should be performed.

New evidence associates endometrial polyps with chronic endometritis

The second important study published this year on polyps was conducted by Cicinelli and colleagues and suggests that inflammation may be part of the pathophysiology behind the common problem of polyps. The authors cite a recent study that showed that abnormal expression of "local" paracrine inflammatory mediators, such as interferon-gamma, may enhance the proliferation of endometrial mucosa.1 Building on this possibility further, they hypothesized that chronic endometrial inflammation may affect the pathogenesis of endometrial polyps.

Details of the study

To investigate the possible correlation between polyps and chronic endometritis, Cicinelli and colleagues compared the endometrial biopsies of 240 women with AUB and hysteroscopically and histologically diagnosed endometrial polyps with 240 women with AUB and no polyp seen on hysteroscopy. The tissue samples were evaluated with immunohistochemistry for CD-138 for plasma cell identification.

The study authors found a significantly higher prevalence of chronic endometritis in the group with endometrial polyps than in the group without polyps (61.7% vs 24.2%, respectively; P <.0001). They suggest that this evidence supports the hypothesis that endometrial polyps may be a result of endometrial proliferation and vasculopathy triggered by chronic endometritis.

The significance of this study is that there is a possible causal relationship between endometrial polyps and chronic endometritis, which may expand the options for endometrial polyp therapy beyond surgical management in the future.

Continue to: Can endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia be treated with the etonogestrel subdermal implant?

Can endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia be treated with the etonogestrel subdermal implant?

Wong S, Naresh A. Etonogestrel subdermal implant-associated regression of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:780-782.

Recently, Wong and Naresh gave us the first case report of successful treatment of EIN using the etonogestrel subdermal implant. With so many other options available to treat EIN, some of which have been studied extensively, why should we take note of this study? First, the authors point out the risk of endometrial cancer development among patients with EIN, and they acknowledge the standard recommendation of hysterectomy in women with EIN who have finished childbearing and are appropriate candidates for a surgical approach. There is also concern about lower serum etonogestrel levels in obese patients. In this case, the patient (aged 36 with obesity) had been nonadherent with oral progestin therapy and stated that she would not adhere to daily oral therapy. She also declined hysterectomy, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device therapy, and injectable progestin therapy after being counseled about the risk of malignancy development. She consented to subdermal etonogestrel as an alternative to no therapy.

EIN regressed. Endometrial biopsies at 4 and 8 months showed regression of EIN, and at 16 months after implantation (as well as a dilation and curettage at 9 months) demonstrated an inactive endometrium with no sign of hyperplasia.

The authors remain cautious about recommending the etonogestrel subdermal implant as a first-line therapy for EIN, but the implant was reported to be effective in this case that involved a patient with obesity. In cases in which surgery or other medical options for EIN are not feasible, the etonogestrel subdermal implant is reasonable to consider. Its routine use for EIN management warrants future study.

New endometrial ablation technology shows promising benefits

Do we need another endometrial ablation device? Are there improvements that can be made to our existing technology? There already are several endometrial ablation devices, using varying technology, that currently are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of AUB. The devices use bipolar radiofrequency, cryotherapy, circulating hot fluid, and combined thermal and radiofrequency modalities. Additional devices, employing heated balloon and microwaves, are no longer used. Data on a new device, approved by the FDA in 2017 (the AEGEA Vapor System, called Mara), were recently published.

Details of the study

Levie and colleagues conducted a prospective pivotal trial on Mara's safety and effectiveness. The benefits presented by the authors include that the device 1) does not require that an intrauterine array be deployed up to and abutting the fundus and cornu, 2) does not necessitate cervical dilatation, 3) is a free-flowing vapor system that can navigate differences in uterine contour and sizes (up to 12 cm in length), and 4) accomplishes ablation in 2 minutes. So there are indeed some novel features of this device.

This pivotal study was a multicenter trial using objective performance criterion (OPC), which is based on using the average success rates across the 5 FDA-approved ablation devices as historic controls. In the study an OPC of 66% correlated to the lower bound of the 95% confidence intervals. The primary outcome of the study was effectiveness in the reduction of blood loss using a pictorial blood loss assessment score (PBLAS) of less than 75. Of note, a PBLAS of 150 was a study entry criterion. FIGO types 2 through 6 fibroids were included in the trial. Secondary endpoints were quality of life and patient satisfaction as assessed by the Menorrhagia Impact Questionnaire and the Aberdeen Menorrhagia Severity Score, as well as the need to intervene medically or surgically to treat AUB in the first 12 months after ablation.

Efficacy, satisfaction, and quality of life results

At 12 months, the primary effectiveness end point was achieved in 78.7% of study participants. The satisfaction rate was 90.8% (satisfied or very satisfied), and 99% of participants showed improvement in quality of life scores. There were no reported serious adverse events.

The takeaway is that the AEGEA device appears to be effective for endometrial ablation and offers the novel features of not relying on an intrauterine array to be deployed up to and abutting the fundus and cornu, not necessitating cervical dilatation in all cases, and offering a free-flowing vapor system that can navigate differences in uterine contour and sizes quickly (approximately 2 minutes).

The fact that new devices for endometrial ablation are still being developed is encouraging, and it suggests that endometrial ablation technology can be improved. Although AEGEA's Mara system is not yet commercially available, it is anticipated that it will be available at the start of 2020. The ability to treat large uteri (up to 12-cm cavities) with FIGO type 2 to 6 fibroids with less cervical dilatation makes the device attractive and perhaps well suited for office use.

Keeping current with causes of and treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is important. AUB can have a major impact on women’s lives in terms of health care expenses, productivity, and quality of life. The focus of this Update is on information that has been published over the past year that is helpful for clinicians who counsel and treat women with AUB. First, we focus on new data on endometrial polyps, which are a common cause of AUB. For the first time, a meta-analysis has examined polyp-associated cancer risk. In addition, does a causal relationship exist between endometrial polyps and chronic endometritis? We also address the first published report of successful treatment of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN, formerly complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia) using the etonogestrel subdermal implant. Last, we discuss efficacy data for a new device for endometrial ablation, which has new features to consider.

What is the risk of malignancy with endometrial polyps?

Sasaki LM, Andrade KR, Figeuiredo AC, et al. Factors associated with malignancy in hysteroscopically resected endometrial polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:777-785.

In the past year, 2 studies have contributed to our understanding of endometrial polyps, with one published as the first ever meta-analysis on polyp risk of malignancy.

What can information from more than 21,000 patients with polyps teach us about the risk factors associated with endometrial malignancy? For instance, with concern over balancing health care costs with potential surgical risks, should all patients with endometrial polyps undergo routine surgical removal, or should we stratify risks and offer surgery to only selected patients? This is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the risk factors for endometrial cancer (such as obesity, parity, tamoxifen use, and hormonal therapy use) in patients with endometrial polyps.

Risk factors for and prevalence of malignancy

Sasaki and colleagues found that about 3 of every 100 patients with recognized polyps will harbor a premalignant or malignant lesion (3.4%; 716 of 21,057 patients). The identified risk factors for a cancerous polyp included: menopausal status, age greater than 60 years, presence of AUB, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and tamoxifen use. The risk for cancer was 2-fold greater in women older than 60 years compared with those younger than age 60 (prevalence ratio, 2.41). The authors found no risk association with use of combination hormone therapy, parity, breast cancer, or polyp size.

The investigators advised caution with using their conclusions, as there was high heterogeneity for some of the factors studied (including age, AUB, parity, and hypertension).

The study takeaways regarding clinical and demographic risk factors suggest that menopausal status, age greater than 60 years, the presence of AUB, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and tamoxifen use have an increased risk for premalignant and malignant lesions.

This study is important because its findings will better enable physicians to inform and counsel patients about the risks for malignancy associated with endometrial polyps, which will better foster discussion and joint decision-making about whether or not surgery should be performed.

New evidence associates endometrial polyps with chronic endometritis

The second important study published this year on polyps was conducted by Cicinelli and colleagues and suggests that inflammation may be part of the pathophysiology behind the common problem of polyps. The authors cite a recent study that showed that abnormal expression of "local" paracrine inflammatory mediators, such as interferon-gamma, may enhance the proliferation of endometrial mucosa.1 Building on this possibility further, they hypothesized that chronic endometrial inflammation may affect the pathogenesis of endometrial polyps.

Details of the study

To investigate the possible correlation between polyps and chronic endometritis, Cicinelli and colleagues compared the endometrial biopsies of 240 women with AUB and hysteroscopically and histologically diagnosed endometrial polyps with 240 women with AUB and no polyp seen on hysteroscopy. The tissue samples were evaluated with immunohistochemistry for CD-138 for plasma cell identification.

The study authors found a significantly higher prevalence of chronic endometritis in the group with endometrial polyps than in the group without polyps (61.7% vs 24.2%, respectively; P <.0001). They suggest that this evidence supports the hypothesis that endometrial polyps may be a result of endometrial proliferation and vasculopathy triggered by chronic endometritis.

The significance of this study is that there is a possible causal relationship between endometrial polyps and chronic endometritis, which may expand the options for endometrial polyp therapy beyond surgical management in the future.

Continue to: Can endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia be treated with the etonogestrel subdermal implant?

Can endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia be treated with the etonogestrel subdermal implant?

Wong S, Naresh A. Etonogestrel subdermal implant-associated regression of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:780-782.

Recently, Wong and Naresh gave us the first case report of successful treatment of EIN using the etonogestrel subdermal implant. With so many other options available to treat EIN, some of which have been studied extensively, why should we take note of this study? First, the authors point out the risk of endometrial cancer development among patients with EIN, and they acknowledge the standard recommendation of hysterectomy in women with EIN who have finished childbearing and are appropriate candidates for a surgical approach. There is also concern about lower serum etonogestrel levels in obese patients. In this case, the patient (aged 36 with obesity) had been nonadherent with oral progestin therapy and stated that she would not adhere to daily oral therapy. She also declined hysterectomy, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device therapy, and injectable progestin therapy after being counseled about the risk of malignancy development. She consented to subdermal etonogestrel as an alternative to no therapy.

EIN regressed. Endometrial biopsies at 4 and 8 months showed regression of EIN, and at 16 months after implantation (as well as a dilation and curettage at 9 months) demonstrated an inactive endometrium with no sign of hyperplasia.

The authors remain cautious about recommending the etonogestrel subdermal implant as a first-line therapy for EIN, but the implant was reported to be effective in this case that involved a patient with obesity. In cases in which surgery or other medical options for EIN are not feasible, the etonogestrel subdermal implant is reasonable to consider. Its routine use for EIN management warrants future study.

New endometrial ablation technology shows promising benefits

Do we need another endometrial ablation device? Are there improvements that can be made to our existing technology? There already are several endometrial ablation devices, using varying technology, that currently are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of AUB. The devices use bipolar radiofrequency, cryotherapy, circulating hot fluid, and combined thermal and radiofrequency modalities. Additional devices, employing heated balloon and microwaves, are no longer used. Data on a new device, approved by the FDA in 2017 (the AEGEA Vapor System, called Mara), were recently published.

Details of the study

Levie and colleagues conducted a prospective pivotal trial on Mara's safety and effectiveness. The benefits presented by the authors include that the device 1) does not require that an intrauterine array be deployed up to and abutting the fundus and cornu, 2) does not necessitate cervical dilatation, 3) is a free-flowing vapor system that can navigate differences in uterine contour and sizes (up to 12 cm in length), and 4) accomplishes ablation in 2 minutes. So there are indeed some novel features of this device.

This pivotal study was a multicenter trial using objective performance criterion (OPC), which is based on using the average success rates across the 5 FDA-approved ablation devices as historic controls. In the study an OPC of 66% correlated to the lower bound of the 95% confidence intervals. The primary outcome of the study was effectiveness in the reduction of blood loss using a pictorial blood loss assessment score (PBLAS) of less than 75. Of note, a PBLAS of 150 was a study entry criterion. FIGO types 2 through 6 fibroids were included in the trial. Secondary endpoints were quality of life and patient satisfaction as assessed by the Menorrhagia Impact Questionnaire and the Aberdeen Menorrhagia Severity Score, as well as the need to intervene medically or surgically to treat AUB in the first 12 months after ablation.

Efficacy, satisfaction, and quality of life results

At 12 months, the primary effectiveness end point was achieved in 78.7% of study participants. The satisfaction rate was 90.8% (satisfied or very satisfied), and 99% of participants showed improvement in quality of life scores. There were no reported serious adverse events.

The takeaway is that the AEGEA device appears to be effective for endometrial ablation and offers the novel features of not relying on an intrauterine array to be deployed up to and abutting the fundus and cornu, not necessitating cervical dilatation in all cases, and offering a free-flowing vapor system that can navigate differences in uterine contour and sizes quickly (approximately 2 minutes).

The fact that new devices for endometrial ablation are still being developed is encouraging, and it suggests that endometrial ablation technology can be improved. Although AEGEA's Mara system is not yet commercially available, it is anticipated that it will be available at the start of 2020. The ability to treat large uteri (up to 12-cm cavities) with FIGO type 2 to 6 fibroids with less cervical dilatation makes the device attractive and perhaps well suited for office use.

- Mollo A, Stile A, Alviggi C, et al. Endometrial polyps in infertile patients: do high concentrations of interferon-gamma play a role? Fertil Steril. 2011:96:1209-1212.

- Mollo A, Stile A, Alviggi C, et al. Endometrial polyps in infertile patients: do high concentrations of interferon-gamma play a role? Fertil Steril. 2011:96:1209-1212.

Treatment for pediatric low-grade glioma is associated with poor cognitive and socioeconomic outcomes

Children who underwent surgery alone had better neuropsychologic and socioeconomic outcomes than those who also underwent radiotherapy, but their outcomes were worse than those of unaffected siblings. These findings were published online June 24 in Cancer.

“Late effects in adulthood are evident even for children with the least malignant types of brain tumors who were treated with the least toxic therapies available at the time,” said M. Douglas Ris, PhD, professor of pediatrics and psychology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, in a press release. “As pediatric brain tumors become more survivable with continued advances in treatments, we need to improve surveillance of these populations so that survivors continue to receive the best interventions during their transition to adulthood and well beyond.”

Clinicians generally have assumed that children with low-grade CNS tumors who receive less toxic treatment will have fewer long-term effects than survivors of more malignant tumors who undergo neurotoxic therapies. Yet research has indicated that the former patients can have lasting neurobehavioral or functional morbidity.

Dr. Ris and colleagues invited survivors of pediatric low-grade gliomas participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and a sibling comparison group to undergo a direct, comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. Of 495 eligible survivors, 257 participated. Seventy-six patients did not travel to a study site, but completed a questionnaire, and the researchers did not include data for this group in their analysis. Dr. Ris and colleagues obtained information about surgery and radiotherapy from participants’ medical records. Patients underwent standardized, age-normed neuropsychologic tests. The primary neuropsychologic outcomes were the Composite Neuropsychological Index (CNI) and estimated IQ. To evaluate socioeconomic outcomes, Dr. Ris and colleagues measured participants’ educational attainment, income, and occupational prestige.

After the researchers adjusted the data for age and sex, they found that siblings had higher mean scores than survivors treated with surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone on all neuropsychologic outcomes, including the CNI (siblings, 106.8; surgery only, 95.6; surgery plus radiotherapy, 88.3) and estimated IQ. Survivors who had been diagnosed at younger ages had low scores for all outcomes except for attention/processing speed.

Furthermore, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 7.7-fold higher risk of having an occupation in the lowest sibling quartile, compared with siblings. Survivors who underwent surgery alone had a 2.8-fold higher risk than siblings of having an occupation in the lowest quartile. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of a low occupation score, compared with survivors who underwent surgery alone.

Compared with siblings, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 4.5-fold risk of an annual income of less than $20,000, while the risk for survivors who underwent surgery alone did not differ significantly from that for siblings. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold higher risk than surgery alone. Surgery plus radiotherapy was also associated with a significantly increased risk for an education level lower than a bachelor’s degree, compared with siblings, but surgery alone was not.

The National Cancer Institute supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ris MD et al. Cancer. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32186.

Children who underwent surgery alone had better neuropsychologic and socioeconomic outcomes than those who also underwent radiotherapy, but their outcomes were worse than those of unaffected siblings. These findings were published online June 24 in Cancer.

“Late effects in adulthood are evident even for children with the least malignant types of brain tumors who were treated with the least toxic therapies available at the time,” said M. Douglas Ris, PhD, professor of pediatrics and psychology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, in a press release. “As pediatric brain tumors become more survivable with continued advances in treatments, we need to improve surveillance of these populations so that survivors continue to receive the best interventions during their transition to adulthood and well beyond.”

Clinicians generally have assumed that children with low-grade CNS tumors who receive less toxic treatment will have fewer long-term effects than survivors of more malignant tumors who undergo neurotoxic therapies. Yet research has indicated that the former patients can have lasting neurobehavioral or functional morbidity.

Dr. Ris and colleagues invited survivors of pediatric low-grade gliomas participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and a sibling comparison group to undergo a direct, comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. Of 495 eligible survivors, 257 participated. Seventy-six patients did not travel to a study site, but completed a questionnaire, and the researchers did not include data for this group in their analysis. Dr. Ris and colleagues obtained information about surgery and radiotherapy from participants’ medical records. Patients underwent standardized, age-normed neuropsychologic tests. The primary neuropsychologic outcomes were the Composite Neuropsychological Index (CNI) and estimated IQ. To evaluate socioeconomic outcomes, Dr. Ris and colleagues measured participants’ educational attainment, income, and occupational prestige.

After the researchers adjusted the data for age and sex, they found that siblings had higher mean scores than survivors treated with surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone on all neuropsychologic outcomes, including the CNI (siblings, 106.8; surgery only, 95.6; surgery plus radiotherapy, 88.3) and estimated IQ. Survivors who had been diagnosed at younger ages had low scores for all outcomes except for attention/processing speed.

Furthermore, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 7.7-fold higher risk of having an occupation in the lowest sibling quartile, compared with siblings. Survivors who underwent surgery alone had a 2.8-fold higher risk than siblings of having an occupation in the lowest quartile. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of a low occupation score, compared with survivors who underwent surgery alone.

Compared with siblings, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 4.5-fold risk of an annual income of less than $20,000, while the risk for survivors who underwent surgery alone did not differ significantly from that for siblings. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold higher risk than surgery alone. Surgery plus radiotherapy was also associated with a significantly increased risk for an education level lower than a bachelor’s degree, compared with siblings, but surgery alone was not.

The National Cancer Institute supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ris MD et al. Cancer. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32186.

Children who underwent surgery alone had better neuropsychologic and socioeconomic outcomes than those who also underwent radiotherapy, but their outcomes were worse than those of unaffected siblings. These findings were published online June 24 in Cancer.

“Late effects in adulthood are evident even for children with the least malignant types of brain tumors who were treated with the least toxic therapies available at the time,” said M. Douglas Ris, PhD, professor of pediatrics and psychology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, in a press release. “As pediatric brain tumors become more survivable with continued advances in treatments, we need to improve surveillance of these populations so that survivors continue to receive the best interventions during their transition to adulthood and well beyond.”

Clinicians generally have assumed that children with low-grade CNS tumors who receive less toxic treatment will have fewer long-term effects than survivors of more malignant tumors who undergo neurotoxic therapies. Yet research has indicated that the former patients can have lasting neurobehavioral or functional morbidity.

Dr. Ris and colleagues invited survivors of pediatric low-grade gliomas participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and a sibling comparison group to undergo a direct, comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. Of 495 eligible survivors, 257 participated. Seventy-six patients did not travel to a study site, but completed a questionnaire, and the researchers did not include data for this group in their analysis. Dr. Ris and colleagues obtained information about surgery and radiotherapy from participants’ medical records. Patients underwent standardized, age-normed neuropsychologic tests. The primary neuropsychologic outcomes were the Composite Neuropsychological Index (CNI) and estimated IQ. To evaluate socioeconomic outcomes, Dr. Ris and colleagues measured participants’ educational attainment, income, and occupational prestige.

After the researchers adjusted the data for age and sex, they found that siblings had higher mean scores than survivors treated with surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone on all neuropsychologic outcomes, including the CNI (siblings, 106.8; surgery only, 95.6; surgery plus radiotherapy, 88.3) and estimated IQ. Survivors who had been diagnosed at younger ages had low scores for all outcomes except for attention/processing speed.

Furthermore, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 7.7-fold higher risk of having an occupation in the lowest sibling quartile, compared with siblings. Survivors who underwent surgery alone had a 2.8-fold higher risk than siblings of having an occupation in the lowest quartile. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of a low occupation score, compared with survivors who underwent surgery alone.

Compared with siblings, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 4.5-fold risk of an annual income of less than $20,000, while the risk for survivors who underwent surgery alone did not differ significantly from that for siblings. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold higher risk than surgery alone. Surgery plus radiotherapy was also associated with a significantly increased risk for an education level lower than a bachelor’s degree, compared with siblings, but surgery alone was not.

The National Cancer Institute supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ris MD et al. Cancer. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32186.

FROM CANCER

Revised CMS TAVR rules expected to widen access

The new National Coverage Determination by Medicare for transcatheter aortic valve replacement should produce a bump in the number of U.S. programs offering the procedure, especially with the Food and Drug Administration on the cusp of approving the procedure for low-risk patients.

In the revised National Coverage Determination (NCD) by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that went into effect on June 21, 2019, the agency allowed for Medicare coverage of transcatheter aortic valve (TAVR) procedures at hospitals that perform at least 20 of these procedures annually or at least 40 every 2 years, the same volume minimums that CMS first applied to TAVR in its prior 2012 NCD. Retention of this minimum ran against the 2018 proposal of the American College of Cardiology, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and two other collaborating societies that called for an annual TAVR volume minimum at a hospital program of 50 procedures annually or 100 every 2 years (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jan 29;73[3]:340-74).

That change, coupled with a cut in the minimum number of annual percutaneous coronary interventions a TAVR program needs to perform – newly revised to a minimum of 300 cases/year – will likely mean more U.S. sites performing TAVR, predicted James Vavricek, director of regulatory affairs for the ACC in Washington. TAVR volume is seen as a reasonable, approximate surrogate for a more rigorous, statistically adjusted assessment of program quality. The ACC and representatives from the other societies that collaborated on the 2018 statement used a 50 case/year minimum for a TAVR program because volume at that level generates enough outcomes data to allow for a meaningful, risk-adjusted measure of performance.

The ACC does not consider the minimum of 20 TAVR cases/year the “right decision,” Mr. Vavricek said in an interview, but the ACC sees it as a compromise that accommodated the interests of multiple TAVR stakeholders. “It will be interesting to see where new TAVR programs locate,” whether they will expand access in underserved regions or mostly cluster in regions already fairly replete with TAVR access, he added. Currently, over 600 U.S. TAVR programs are in operation.

In April 2019, the president of the ACC along with the presidents of three other U.S. societies with an interest in TAVR told the CMS in a comment letter that “we are extremely concerned that the proposed volume requirements will translate into a proliferation of low-volume TAVR programs at increased risk for having suboptimal outcomes.”

Another change to procedure volume requirements in the new NCD was setting a minimum of 100 total TAVR plus surgical aortic valve replacements in a 2-year period or 50 total procedures/year for each TAVR program. Setting a minimum that bundles TAVR plus surgical valve replacements is a “forward-looking” approach as wider application of TAVR gradually erodes the volume of surgical procedures, Mr. Vavricek said.

An additional notable change in the revised NCD was elimination of the “two-surgeon” rule, which the CMS had made mandatory for TAVR decisions until now, stipulating that a patient considered for TAVR needed independent assessment by two cardiac surgeons. The final 2019 NCD calls for the TAVR decision to come from one cardiac surgeon and one interventional cardiologist working together on a care team.

“The ACC is pleased to see CMS issue updated TAVR coverage criteria that emphasizes care by an interdisciplinary heart team for these complex patients, as well as continues to mandate the collection of TAVR patient data. With the new lowered minimum yearly volume criteria set by CMS in their efforts to improve patient access, the value of the STS/ACC TVT Registry, along with ACC’s Transcatheter Valve Certification, will be critical in assuring quality of care for our patients particularly in low-volume centers,” commented Richard J. Kovacs, MD, ACC’s president.

The new National Coverage Determination by Medicare for transcatheter aortic valve replacement should produce a bump in the number of U.S. programs offering the procedure, especially with the Food and Drug Administration on the cusp of approving the procedure for low-risk patients.

In the revised National Coverage Determination (NCD) by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that went into effect on June 21, 2019, the agency allowed for Medicare coverage of transcatheter aortic valve (TAVR) procedures at hospitals that perform at least 20 of these procedures annually or at least 40 every 2 years, the same volume minimums that CMS first applied to TAVR in its prior 2012 NCD. Retention of this minimum ran against the 2018 proposal of the American College of Cardiology, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and two other collaborating societies that called for an annual TAVR volume minimum at a hospital program of 50 procedures annually or 100 every 2 years (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jan 29;73[3]:340-74).

That change, coupled with a cut in the minimum number of annual percutaneous coronary interventions a TAVR program needs to perform – newly revised to a minimum of 300 cases/year – will likely mean more U.S. sites performing TAVR, predicted James Vavricek, director of regulatory affairs for the ACC in Washington. TAVR volume is seen as a reasonable, approximate surrogate for a more rigorous, statistically adjusted assessment of program quality. The ACC and representatives from the other societies that collaborated on the 2018 statement used a 50 case/year minimum for a TAVR program because volume at that level generates enough outcomes data to allow for a meaningful, risk-adjusted measure of performance.

The ACC does not consider the minimum of 20 TAVR cases/year the “right decision,” Mr. Vavricek said in an interview, but the ACC sees it as a compromise that accommodated the interests of multiple TAVR stakeholders. “It will be interesting to see where new TAVR programs locate,” whether they will expand access in underserved regions or mostly cluster in regions already fairly replete with TAVR access, he added. Currently, over 600 U.S. TAVR programs are in operation.

In April 2019, the president of the ACC along with the presidents of three other U.S. societies with an interest in TAVR told the CMS in a comment letter that “we are extremely concerned that the proposed volume requirements will translate into a proliferation of low-volume TAVR programs at increased risk for having suboptimal outcomes.”

Another change to procedure volume requirements in the new NCD was setting a minimum of 100 total TAVR plus surgical aortic valve replacements in a 2-year period or 50 total procedures/year for each TAVR program. Setting a minimum that bundles TAVR plus surgical valve replacements is a “forward-looking” approach as wider application of TAVR gradually erodes the volume of surgical procedures, Mr. Vavricek said.

An additional notable change in the revised NCD was elimination of the “two-surgeon” rule, which the CMS had made mandatory for TAVR decisions until now, stipulating that a patient considered for TAVR needed independent assessment by two cardiac surgeons. The final 2019 NCD calls for the TAVR decision to come from one cardiac surgeon and one interventional cardiologist working together on a care team.

“The ACC is pleased to see CMS issue updated TAVR coverage criteria that emphasizes care by an interdisciplinary heart team for these complex patients, as well as continues to mandate the collection of TAVR patient data. With the new lowered minimum yearly volume criteria set by CMS in their efforts to improve patient access, the value of the STS/ACC TVT Registry, along with ACC’s Transcatheter Valve Certification, will be critical in assuring quality of care for our patients particularly in low-volume centers,” commented Richard J. Kovacs, MD, ACC’s president.

The new National Coverage Determination by Medicare for transcatheter aortic valve replacement should produce a bump in the number of U.S. programs offering the procedure, especially with the Food and Drug Administration on the cusp of approving the procedure for low-risk patients.

In the revised National Coverage Determination (NCD) by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that went into effect on June 21, 2019, the agency allowed for Medicare coverage of transcatheter aortic valve (TAVR) procedures at hospitals that perform at least 20 of these procedures annually or at least 40 every 2 years, the same volume minimums that CMS first applied to TAVR in its prior 2012 NCD. Retention of this minimum ran against the 2018 proposal of the American College of Cardiology, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and two other collaborating societies that called for an annual TAVR volume minimum at a hospital program of 50 procedures annually or 100 every 2 years (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jan 29;73[3]:340-74).

That change, coupled with a cut in the minimum number of annual percutaneous coronary interventions a TAVR program needs to perform – newly revised to a minimum of 300 cases/year – will likely mean more U.S. sites performing TAVR, predicted James Vavricek, director of regulatory affairs for the ACC in Washington. TAVR volume is seen as a reasonable, approximate surrogate for a more rigorous, statistically adjusted assessment of program quality. The ACC and representatives from the other societies that collaborated on the 2018 statement used a 50 case/year minimum for a TAVR program because volume at that level generates enough outcomes data to allow for a meaningful, risk-adjusted measure of performance.

The ACC does not consider the minimum of 20 TAVR cases/year the “right decision,” Mr. Vavricek said in an interview, but the ACC sees it as a compromise that accommodated the interests of multiple TAVR stakeholders. “It will be interesting to see where new TAVR programs locate,” whether they will expand access in underserved regions or mostly cluster in regions already fairly replete with TAVR access, he added. Currently, over 600 U.S. TAVR programs are in operation.

In April 2019, the president of the ACC along with the presidents of three other U.S. societies with an interest in TAVR told the CMS in a comment letter that “we are extremely concerned that the proposed volume requirements will translate into a proliferation of low-volume TAVR programs at increased risk for having suboptimal outcomes.”

Another change to procedure volume requirements in the new NCD was setting a minimum of 100 total TAVR plus surgical aortic valve replacements in a 2-year period or 50 total procedures/year for each TAVR program. Setting a minimum that bundles TAVR plus surgical valve replacements is a “forward-looking” approach as wider application of TAVR gradually erodes the volume of surgical procedures, Mr. Vavricek said.

An additional notable change in the revised NCD was elimination of the “two-surgeon” rule, which the CMS had made mandatory for TAVR decisions until now, stipulating that a patient considered for TAVR needed independent assessment by two cardiac surgeons. The final 2019 NCD calls for the TAVR decision to come from one cardiac surgeon and one interventional cardiologist working together on a care team.

“The ACC is pleased to see CMS issue updated TAVR coverage criteria that emphasizes care by an interdisciplinary heart team for these complex patients, as well as continues to mandate the collection of TAVR patient data. With the new lowered minimum yearly volume criteria set by CMS in their efforts to improve patient access, the value of the STS/ACC TVT Registry, along with ACC’s Transcatheter Valve Certification, will be critical in assuring quality of care for our patients particularly in low-volume centers,” commented Richard J. Kovacs, MD, ACC’s president.

Acute Graft-vs-host Disease Following Liver Transplantation

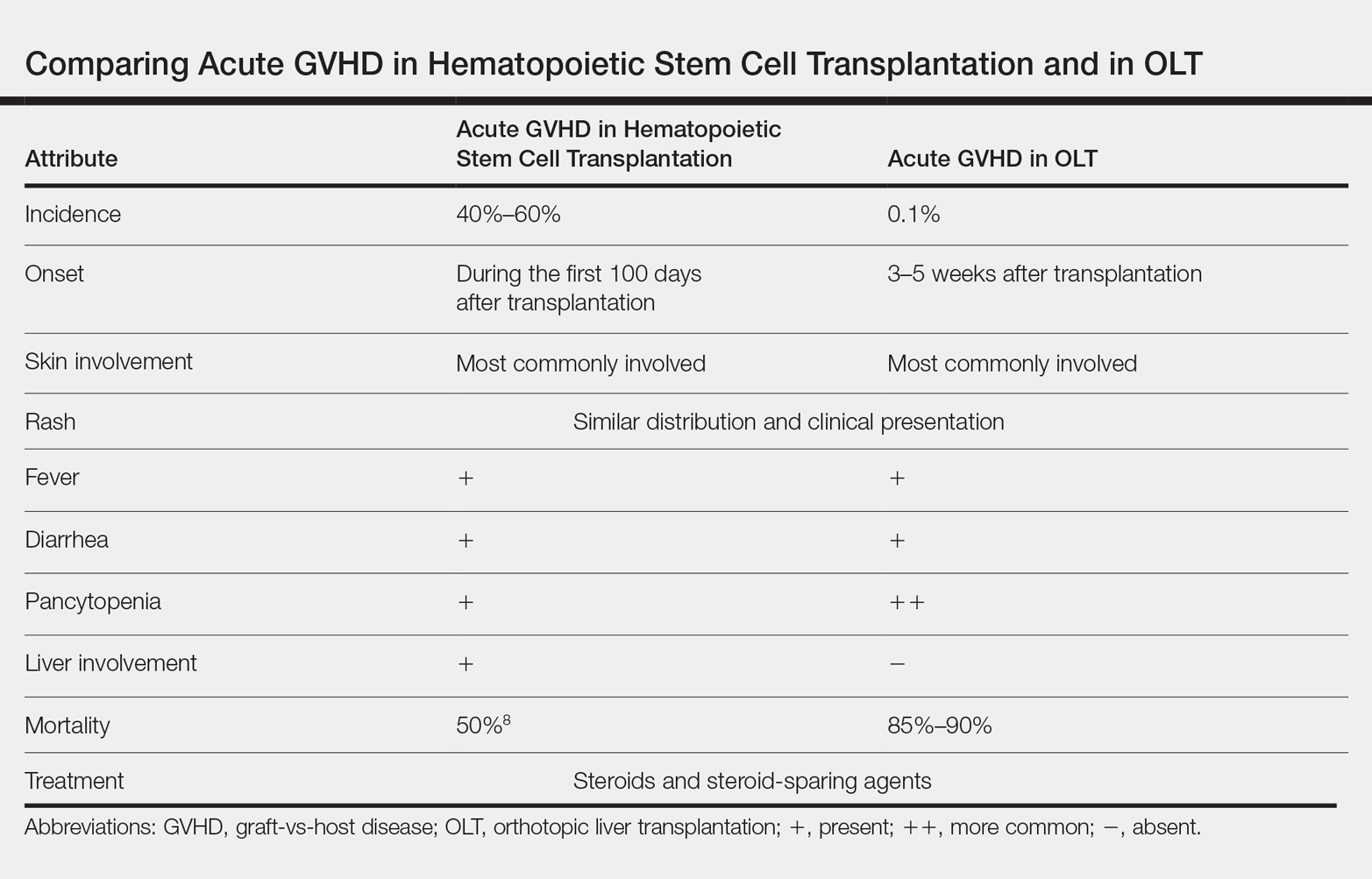

Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) is a T-cell mediated immunogenic response in which T lymphocytes from a donor regard host tissue as foreign and attack it in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common cause of acute GVHD is allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with solid-organ transplantation being a much less common cause.2 The incidence of acute GVHD following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is 0.1%, as reported by the United Network for Organ Sharing, compared to an incidence of 40% to 60% in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.3,4

Early recognition and treatment of acute GVHD following liver transplantation is imperative, as the mortality rate is 85% to 90%.2 We present a case of acute GVHD in a liver transplantation patient, with a focus on diagnostic criteria and comparison to acute GVHD following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and OLT 1 month prior presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal cellulitis in close proximity to the surgical site of 1 week’s duration. The patient was started on vancomycin and cefepime; pan cultures were performed.

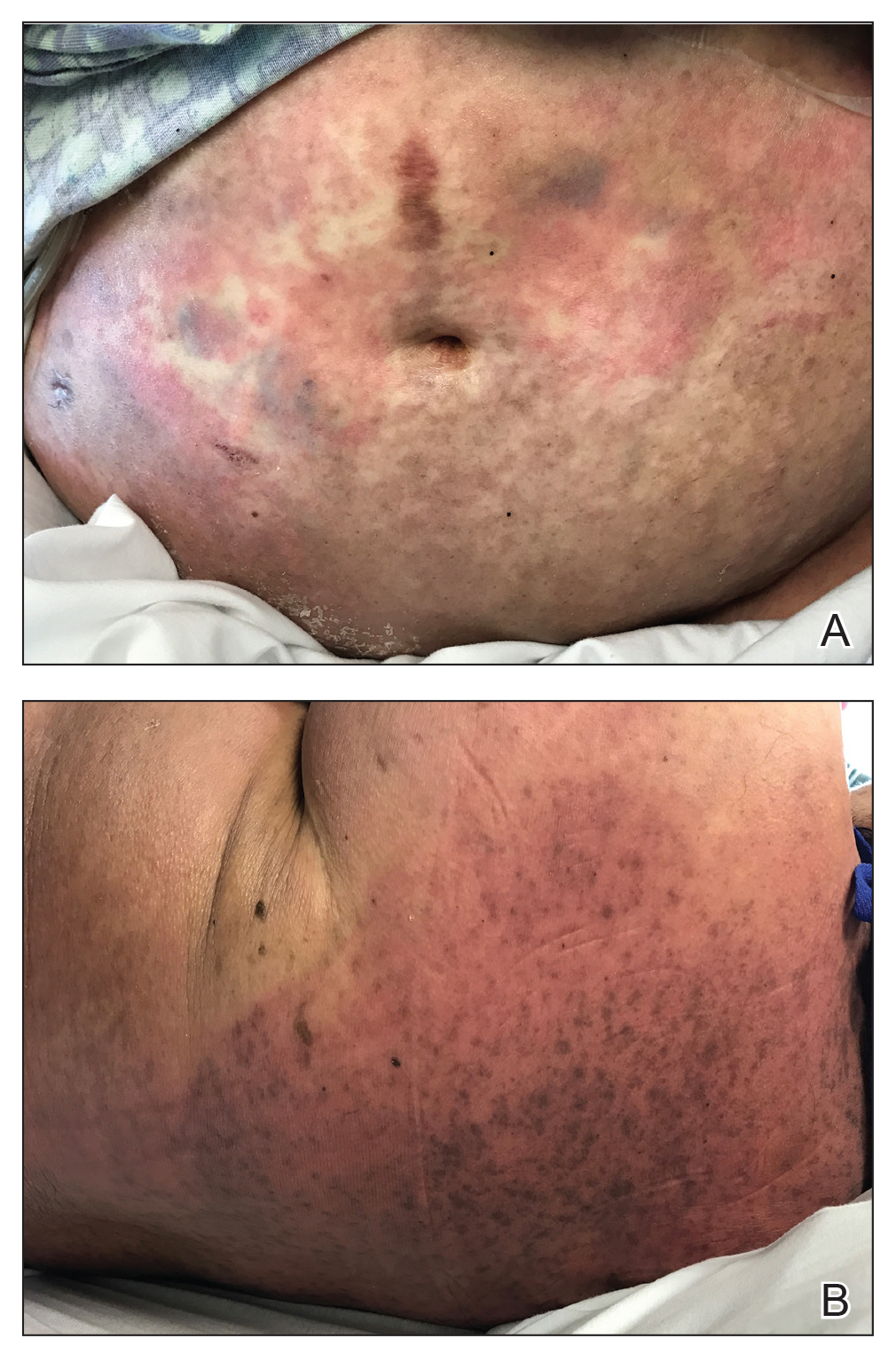

At 10 days of hospitalization, the patient developed a pruritic, nontender, erythematous rash on the abdomen, with extension onto the chest and legs. The rash was associated with low-grade fever but not with diarrhea. Physical examination was notable for a few erythematous macules and scattered papules over the neck and chest and a large erythematous plaque with multiple ecchymoses over the lower abdomen (Figure 1A). Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into plaques were present on the lower back (Figure 1B) and proximal thighs. Oral, ocular, and genital lesions were absent.

The differential diagnosis included drug reaction, viral infection, and acute GVHD. A skin biopsy was performed from the left side of the chest. Cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and antihistamines as needed for itching were started.

Over a 2-day period, the rash progressed to diffuse erythematous papules over the chest (Figure 2A) and bilateral arms (Figure 2B) including the palms. The patient also developed erythematous papules over the jawline and forehead as well as confluent erythematous plaques over the back with extension of the rash to involve the legs. She also had erythema and swelling bilaterally over the ears. She reported diarrhea. The low-grade fever resolved.

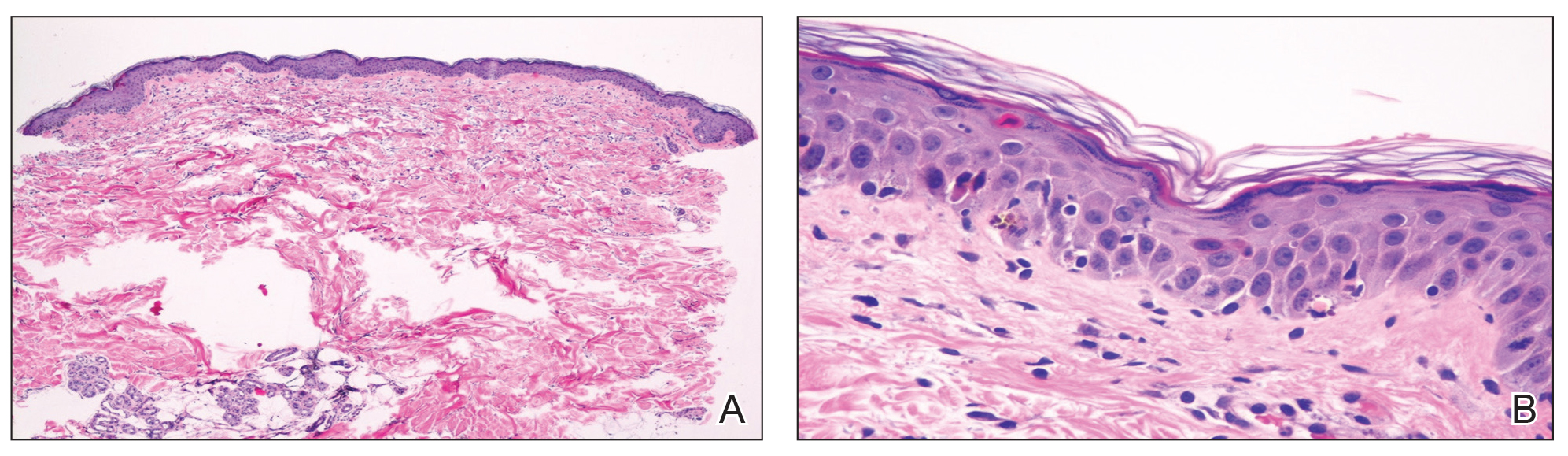

Laboratory review showed new-onset pancytopenia, normal liver function, and an elevated creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL), consistent with the patient’s baseline of stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for cytomegalovirus was negative. Histology revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic keratinocytes, consistent with grade I GVHD (Figure 3). Duodenal biopsy revealed rare patchy glands with increased apoptosis, compatible with grade I GVHD.

The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 3 days, then transitioned to an oral steroid taper, with improvement of the rash and other systemic symptoms.

Comment

GVHD Subtypes

The 2 types of GVHD are humoral and cellular.5 The humoral type results from ABO blood type incompatibility between donor and recipient and causes mild hemolytic anemia and fever. The cellular type is directed against major histocompatibility complexes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Presentation of GVHD

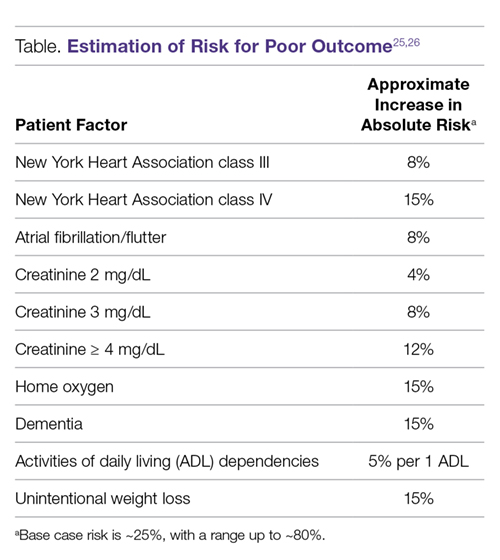

Acute GVHD following OLT usually occurs 3 to 5 weeks after transplantation,6 as in our patient. Symptoms include rash, fever, pancytopenia, and diarrhea.2 Skin is the most commonly involved organ in acute GVHD; rash is the earliest manifestation.1 The rash can be asymptomatic or associated with pain and pruritus. Initial cutaneous manifestations include palmar erythema and erythematous to violaceous discoloration of the face and ears. A diffuse maculopapular rash can develop, involving the face, abdomen, and trunk. The rash may progress to formation of bullae or skin sloughing, resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 The skin manifestation of acute GVHD following OLT is similar to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table).7,8

Pancytopenia is a common manifestation of GVHD following liver transplantation and is rarely seen following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.7 Donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the bone marrow, attacking recipient hematopoietic stem cells. It is important to note that more common causes of cytopenia following liver transplantation, including infection and drug-induced bone marrow suppression, should be ruled out before diagnosing acute GVHD.6

Acute GVHD can affect the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea; however, other infectious and medication-induced causes of diarrhea also should be considered.6 In contrast to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in which the liver is usually involved,1 the liver is spared in acute GVHD following liver transplantation.5

Diagnosis of GVHD

The diagnosis of acute GVHD following liver transplantation can be challenging because the clinical manifestations can be caused by a drug reaction or viral infection, such as cytomegalovirus infection.2 Patients who are older than 50 years and glucose intolerant are at a higher risk of acute GVHD following OLT. The combination of younger donor age and the presence of an HLA class I match also increases the risk of acute GVHD.6 The diagnosis of acute GVHD is confirmed with biopsy of the skin or gastrointestinal tract.

Morbidity and Mortality of GVHD

Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with acute GVHD following liver transplantation, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial.5 Death in patients with acute GVHD following OLT is mainly attributable to sepsis, multiorgan failure, and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.6 It remains unclear whether this high mortality is associated with delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific signs of acute GVHD following OLT or to the lack of appropriate treatment guidelines.6

Treatment Options

Because of the low incidence of acute GVHD following OLT, most treatment modalities are extrapolated from the literature on acute GVHD following stem cell transplantation.5 The most commonly used therapies include high-dose systemic steroids and anti–thymocyte globulin that attacks activated donor T cells.6 Other treatment modalities, including anti–tumor necrosis factor agents and antibodies to CD20, have been reported to be effective in steroid-refractory GVHD.2 The major drawback of systemic steroids is an increase in the risk for sepsis and infection; therefore, these patients should be diligently screened for infection and covered with antibiotics and antifungals. Extracorporeal photopheresis is another treatment modality that does not cause generalized immunosuppression but is not well studied in the setting of acute GVHD following OLT.6

Prevention

Acute GVHD following OLT can be prevented by eliminating donor T lymphocytes from the liver before transplantation. However, because the incidence of acute GVHD following OLT is very low, this approach is not routinely taken.2

Conclusion

Acute GVHD following liver transplantation is a rare complication; however, it has high mortality, necessitating further research regarding treatment and prevention. Early recognition and treatment of this condition can improve outcomes. Dermatologists should be familiar with the skin manifestations of acute GVHD following liver transplantation due to the rising number of cases of solid-organ transplantation.

- Hu SW, Cotliar J. Acute graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:411-423.

- Akbulut S, Yilmaz M, Yilmaz S. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: a comprehensive literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5240-5248.

- Taylor AL, Gibbs P, Bradley JA. Acute graft versus host disease following liver transplantation: the enemy within. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:466-474.

- Jagasia M, Arora M, Flowers ME, et al. Risk factor for acute GVHD and survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:296-307.

- Kang WH, Hwang S, Song GW, et al. Acute graft-vs-host disease after liver transplantation: experience at a high-volume liver transplantation center in Korea. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:3368-3372.

- Murali AR, Chandra S, Stewart Z, et al. Graft versus host disease after liver transplantation in adults: a case series, review of literature, and an approach to management. Transplantation. 2016;100:2661-2670.

- Chaib E, Silva FD, Figueira ER, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1115-1118.

- Barton-Burke M, Dwinell DM, Kafkas L, et al. Graft-versus-host disease: a complex long-term side effect of hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Oncology (Williston Park). 2008;22(11 Suppl Nurse Ed):31-45.

Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) is a T-cell mediated immunogenic response in which T lymphocytes from a donor regard host tissue as foreign and attack it in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common cause of acute GVHD is allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with solid-organ transplantation being a much less common cause.2 The incidence of acute GVHD following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is 0.1%, as reported by the United Network for Organ Sharing, compared to an incidence of 40% to 60% in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.3,4

Early recognition and treatment of acute GVHD following liver transplantation is imperative, as the mortality rate is 85% to 90%.2 We present a case of acute GVHD in a liver transplantation patient, with a focus on diagnostic criteria and comparison to acute GVHD following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and OLT 1 month prior presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal cellulitis in close proximity to the surgical site of 1 week’s duration. The patient was started on vancomycin and cefepime; pan cultures were performed.

At 10 days of hospitalization, the patient developed a pruritic, nontender, erythematous rash on the abdomen, with extension onto the chest and legs. The rash was associated with low-grade fever but not with diarrhea. Physical examination was notable for a few erythematous macules and scattered papules over the neck and chest and a large erythematous plaque with multiple ecchymoses over the lower abdomen (Figure 1A). Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into plaques were present on the lower back (Figure 1B) and proximal thighs. Oral, ocular, and genital lesions were absent.

The differential diagnosis included drug reaction, viral infection, and acute GVHD. A skin biopsy was performed from the left side of the chest. Cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and antihistamines as needed for itching were started.

Over a 2-day period, the rash progressed to diffuse erythematous papules over the chest (Figure 2A) and bilateral arms (Figure 2B) including the palms. The patient also developed erythematous papules over the jawline and forehead as well as confluent erythematous plaques over the back with extension of the rash to involve the legs. She also had erythema and swelling bilaterally over the ears. She reported diarrhea. The low-grade fever resolved.

Laboratory review showed new-onset pancytopenia, normal liver function, and an elevated creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL), consistent with the patient’s baseline of stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for cytomegalovirus was negative. Histology revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic keratinocytes, consistent with grade I GVHD (Figure 3). Duodenal biopsy revealed rare patchy glands with increased apoptosis, compatible with grade I GVHD.

The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 3 days, then transitioned to an oral steroid taper, with improvement of the rash and other systemic symptoms.

Comment

GVHD Subtypes

The 2 types of GVHD are humoral and cellular.5 The humoral type results from ABO blood type incompatibility between donor and recipient and causes mild hemolytic anemia and fever. The cellular type is directed against major histocompatibility complexes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Presentation of GVHD

Acute GVHD following OLT usually occurs 3 to 5 weeks after transplantation,6 as in our patient. Symptoms include rash, fever, pancytopenia, and diarrhea.2 Skin is the most commonly involved organ in acute GVHD; rash is the earliest manifestation.1 The rash can be asymptomatic or associated with pain and pruritus. Initial cutaneous manifestations include palmar erythema and erythematous to violaceous discoloration of the face and ears. A diffuse maculopapular rash can develop, involving the face, abdomen, and trunk. The rash may progress to formation of bullae or skin sloughing, resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 The skin manifestation of acute GVHD following OLT is similar to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table).7,8

Pancytopenia is a common manifestation of GVHD following liver transplantation and is rarely seen following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.7 Donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the bone marrow, attacking recipient hematopoietic stem cells. It is important to note that more common causes of cytopenia following liver transplantation, including infection and drug-induced bone marrow suppression, should be ruled out before diagnosing acute GVHD.6

Acute GVHD can affect the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea; however, other infectious and medication-induced causes of diarrhea also should be considered.6 In contrast to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in which the liver is usually involved,1 the liver is spared in acute GVHD following liver transplantation.5

Diagnosis of GVHD

The diagnosis of acute GVHD following liver transplantation can be challenging because the clinical manifestations can be caused by a drug reaction or viral infection, such as cytomegalovirus infection.2 Patients who are older than 50 years and glucose intolerant are at a higher risk of acute GVHD following OLT. The combination of younger donor age and the presence of an HLA class I match also increases the risk of acute GVHD.6 The diagnosis of acute GVHD is confirmed with biopsy of the skin or gastrointestinal tract.

Morbidity and Mortality of GVHD

Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with acute GVHD following liver transplantation, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial.5 Death in patients with acute GVHD following OLT is mainly attributable to sepsis, multiorgan failure, and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.6 It remains unclear whether this high mortality is associated with delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific signs of acute GVHD following OLT or to the lack of appropriate treatment guidelines.6

Treatment Options

Because of the low incidence of acute GVHD following OLT, most treatment modalities are extrapolated from the literature on acute GVHD following stem cell transplantation.5 The most commonly used therapies include high-dose systemic steroids and anti–thymocyte globulin that attacks activated donor T cells.6 Other treatment modalities, including anti–tumor necrosis factor agents and antibodies to CD20, have been reported to be effective in steroid-refractory GVHD.2 The major drawback of systemic steroids is an increase in the risk for sepsis and infection; therefore, these patients should be diligently screened for infection and covered with antibiotics and antifungals. Extracorporeal photopheresis is another treatment modality that does not cause generalized immunosuppression but is not well studied in the setting of acute GVHD following OLT.6

Prevention

Acute GVHD following OLT can be prevented by eliminating donor T lymphocytes from the liver before transplantation. However, because the incidence of acute GVHD following OLT is very low, this approach is not routinely taken.2

Conclusion

Acute GVHD following liver transplantation is a rare complication; however, it has high mortality, necessitating further research regarding treatment and prevention. Early recognition and treatment of this condition can improve outcomes. Dermatologists should be familiar with the skin manifestations of acute GVHD following liver transplantation due to the rising number of cases of solid-organ transplantation.

Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) is a T-cell mediated immunogenic response in which T lymphocytes from a donor regard host tissue as foreign and attack it in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common cause of acute GVHD is allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with solid-organ transplantation being a much less common cause.2 The incidence of acute GVHD following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is 0.1%, as reported by the United Network for Organ Sharing, compared to an incidence of 40% to 60% in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.3,4

Early recognition and treatment of acute GVHD following liver transplantation is imperative, as the mortality rate is 85% to 90%.2 We present a case of acute GVHD in a liver transplantation patient, with a focus on diagnostic criteria and comparison to acute GVHD following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and OLT 1 month prior presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal cellulitis in close proximity to the surgical site of 1 week’s duration. The patient was started on vancomycin and cefepime; pan cultures were performed.

At 10 days of hospitalization, the patient developed a pruritic, nontender, erythematous rash on the abdomen, with extension onto the chest and legs. The rash was associated with low-grade fever but not with diarrhea. Physical examination was notable for a few erythematous macules and scattered papules over the neck and chest and a large erythematous plaque with multiple ecchymoses over the lower abdomen (Figure 1A). Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into plaques were present on the lower back (Figure 1B) and proximal thighs. Oral, ocular, and genital lesions were absent.

The differential diagnosis included drug reaction, viral infection, and acute GVHD. A skin biopsy was performed from the left side of the chest. Cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and antihistamines as needed for itching were started.

Over a 2-day period, the rash progressed to diffuse erythematous papules over the chest (Figure 2A) and bilateral arms (Figure 2B) including the palms. The patient also developed erythematous papules over the jawline and forehead as well as confluent erythematous plaques over the back with extension of the rash to involve the legs. She also had erythema and swelling bilaterally over the ears. She reported diarrhea. The low-grade fever resolved.

Laboratory review showed new-onset pancytopenia, normal liver function, and an elevated creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL), consistent with the patient’s baseline of stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for cytomegalovirus was negative. Histology revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic keratinocytes, consistent with grade I GVHD (Figure 3). Duodenal biopsy revealed rare patchy glands with increased apoptosis, compatible with grade I GVHD.

The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 3 days, then transitioned to an oral steroid taper, with improvement of the rash and other systemic symptoms.

Comment

GVHD Subtypes

The 2 types of GVHD are humoral and cellular.5 The humoral type results from ABO blood type incompatibility between donor and recipient and causes mild hemolytic anemia and fever. The cellular type is directed against major histocompatibility complexes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Presentation of GVHD

Acute GVHD following OLT usually occurs 3 to 5 weeks after transplantation,6 as in our patient. Symptoms include rash, fever, pancytopenia, and diarrhea.2 Skin is the most commonly involved organ in acute GVHD; rash is the earliest manifestation.1 The rash can be asymptomatic or associated with pain and pruritus. Initial cutaneous manifestations include palmar erythema and erythematous to violaceous discoloration of the face and ears. A diffuse maculopapular rash can develop, involving the face, abdomen, and trunk. The rash may progress to formation of bullae or skin sloughing, resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 The skin manifestation of acute GVHD following OLT is similar to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table).7,8

Pancytopenia is a common manifestation of GVHD following liver transplantation and is rarely seen following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.7 Donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the bone marrow, attacking recipient hematopoietic stem cells. It is important to note that more common causes of cytopenia following liver transplantation, including infection and drug-induced bone marrow suppression, should be ruled out before diagnosing acute GVHD.6

Acute GVHD can affect the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea; however, other infectious and medication-induced causes of diarrhea also should be considered.6 In contrast to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in which the liver is usually involved,1 the liver is spared in acute GVHD following liver transplantation.5

Diagnosis of GVHD

The diagnosis of acute GVHD following liver transplantation can be challenging because the clinical manifestations can be caused by a drug reaction or viral infection, such as cytomegalovirus infection.2 Patients who are older than 50 years and glucose intolerant are at a higher risk of acute GVHD following OLT. The combination of younger donor age and the presence of an HLA class I match also increases the risk of acute GVHD.6 The diagnosis of acute GVHD is confirmed with biopsy of the skin or gastrointestinal tract.

Morbidity and Mortality of GVHD

Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with acute GVHD following liver transplantation, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial.5 Death in patients with acute GVHD following OLT is mainly attributable to sepsis, multiorgan failure, and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.6 It remains unclear whether this high mortality is associated with delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific signs of acute GVHD following OLT or to the lack of appropriate treatment guidelines.6

Treatment Options

Because of the low incidence of acute GVHD following OLT, most treatment modalities are extrapolated from the literature on acute GVHD following stem cell transplantation.5 The most commonly used therapies include high-dose systemic steroids and anti–thymocyte globulin that attacks activated donor T cells.6 Other treatment modalities, including anti–tumor necrosis factor agents and antibodies to CD20, have been reported to be effective in steroid-refractory GVHD.2 The major drawback of systemic steroids is an increase in the risk for sepsis and infection; therefore, these patients should be diligently screened for infection and covered with antibiotics and antifungals. Extracorporeal photopheresis is another treatment modality that does not cause generalized immunosuppression but is not well studied in the setting of acute GVHD following OLT.6

Prevention

Acute GVHD following OLT can be prevented by eliminating donor T lymphocytes from the liver before transplantation. However, because the incidence of acute GVHD following OLT is very low, this approach is not routinely taken.2

Conclusion

Acute GVHD following liver transplantation is a rare complication; however, it has high mortality, necessitating further research regarding treatment and prevention. Early recognition and treatment of this condition can improve outcomes. Dermatologists should be familiar with the skin manifestations of acute GVHD following liver transplantation due to the rising number of cases of solid-organ transplantation.

- Hu SW, Cotliar J. Acute graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:411-423.